The Infernals: Fournier and Metz

Henri Fournier, Charles Metz and the Dawn of the Motorcycle in America

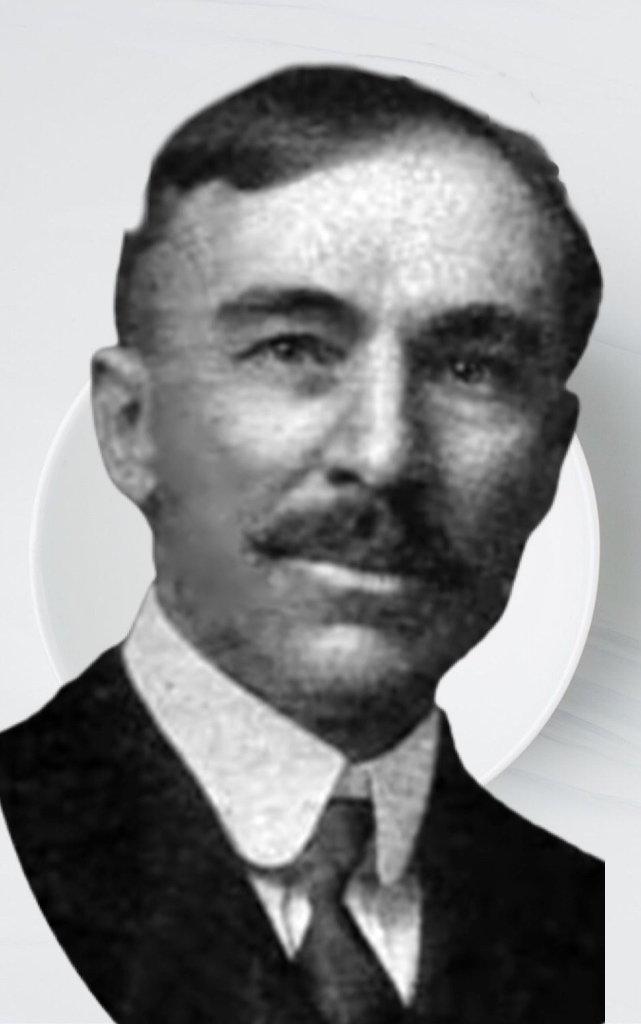

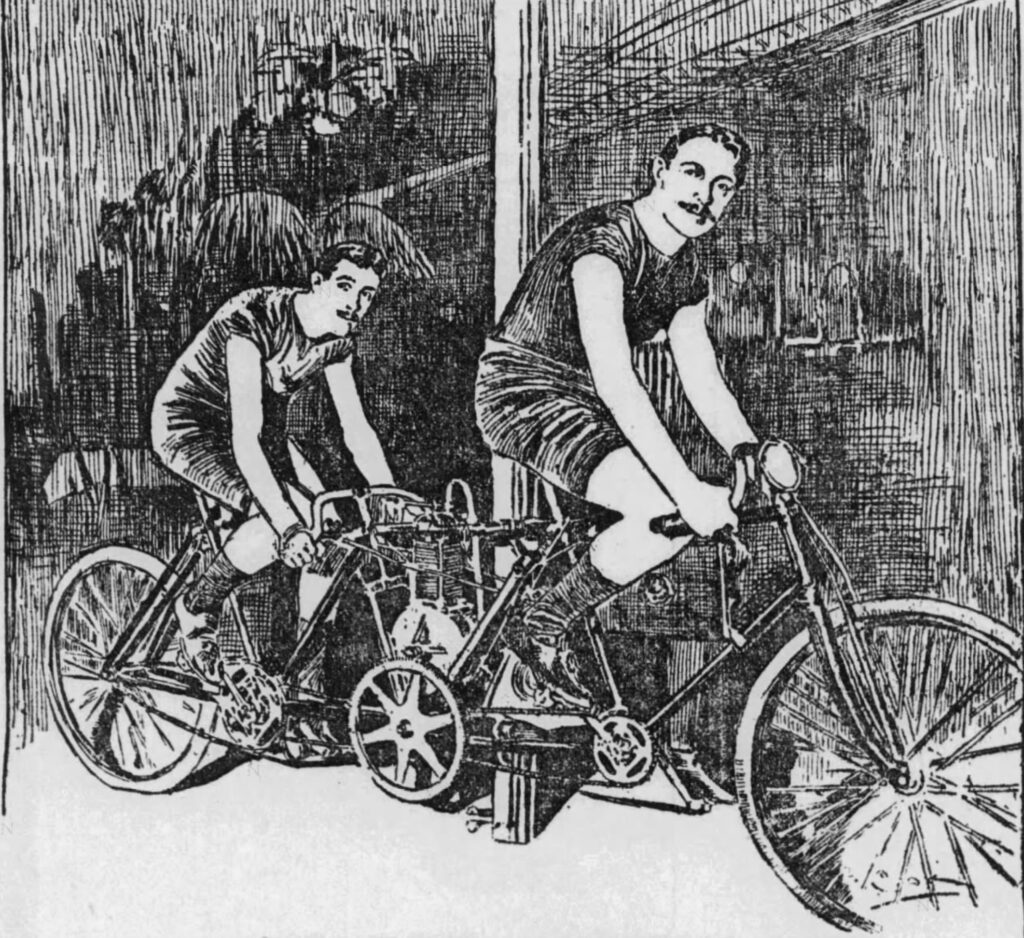

There are several historical events that mark the evolution of the motorcycle in America but one that is particularly noteworthy occurred on June 26, 1899. On that day Frenchman Henri Fournier, the most experienced motorman in America at the time, signed a two-year contract with Charles Herman Metz, president of the Waltham Manufacturing Company, manufacturers of the Orient bicycle, the fastest pedal-powered racing machines in America.[1] Under the terms of their agreement, Fournier would supervise the building of a new petroleum-fueled Orient line that would propel American motorcycle manufacturing into the next century. The Detroit Free Press reported that seven new Orient motor tandems would be built under Fournier’s direct supervision.

“Fournier especially designed these machines and has carte blanche to build them, with the entire working force of the factory at his elbow and with unparalleled facilities for turning out one of the best and fastest machines ever seen.”[2]

Before teaming up, the two men had already made important contributions to pedal and motor power in their own right, both in America and, in Fournier’s case, in Europe. Both men were intrigued with track speed, specifically overcoming the perceived limits in generating it. Their individual paths blazed hot before there was any contract between them

Metz started out building bicycles for recreational use with the incorporation of the Waltham Manufacturing Company on October 30, 1893. He quickly turned to racing as his target market and when the Orient triplet was released in the fall of 1894 it quickly dominated the pacemaking game in America, solidifying the Waltham Company as the top manufacturing concern in the country when it came to racing. By the end of 1897 Metz was all in on pacing machines of all sizes, building and marketing tandems, triplets, quads and quints for America’s most popular sport — bicycle racing.

“Although the Jallu brothers did not bring with them the electric tandem of which so much had been promised, it really appears as if they will ride such a machine on the American tracks this year, but it will be an American-built article, and will most likely be superior to the foreign article. The Waltham Manufacturing Company, of Waltham, Mass., is building such a machine.”[6]

On May 30 the Jallu-designed Orient electric prototype made its inaugural appearance at the Ambrose Park race track in Brooklyn, New York. It took two trips around the track and promptly died. The sporting press was unmerciful and the fabled machine was never seen or mentioned again. The Jallu brothers, soul-crushed and broke, sailed back to France on July 15 – in steerage. But a year later America would be introduced to the fastest petroleum motor tandems yet seen on velodromes anywhere, manufactured by the up-start Jallu Motor Company of France. The ’99 racing season would witness a Ford versus Ferrari extravaganza as the Waltham and Jallu companies battled for supremacy on American tracks. But that is another story.

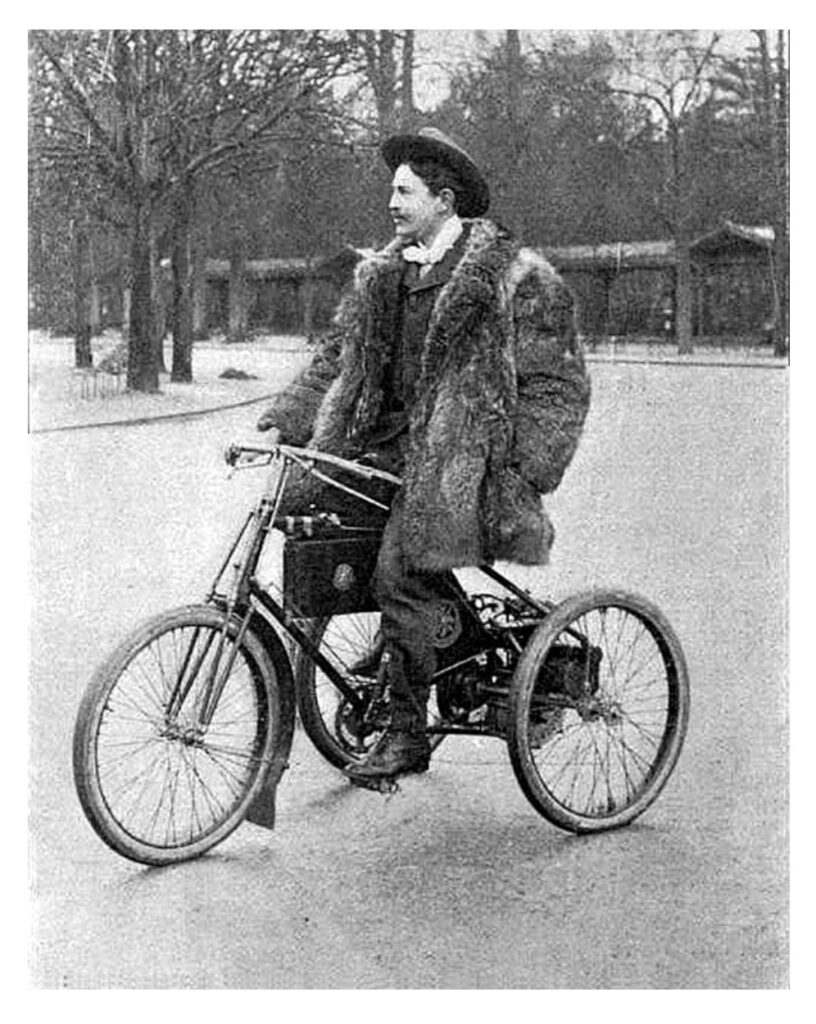

Metz continued toying with electric motor power but when it came to racing and pacing, he was willing to entertain other options. Fournier on the other hand was brimming with confidence in the future of petroleum power. Just three months after the dejected Jallu brothers returned to France, Fournier introduced De Dion-Bouton petroleum power to America. Accompanied by French compatriot Gaston Ricard, he arrived in New York on October 18, 1898 with a French-made motor power trifecta: a tricycle and single, both powered by De Dion-Bouton petroleum motors and a massive Bollee tandem tricycle. Wheel and Cycling Trade Review noted, “These machines are the first of their kind brought to America, and, according to Fournier, have many points of superiority over the electric tandems.”[7] Metz would come to the same conclusion.

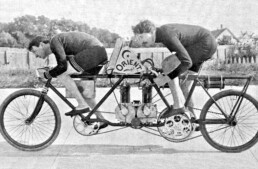

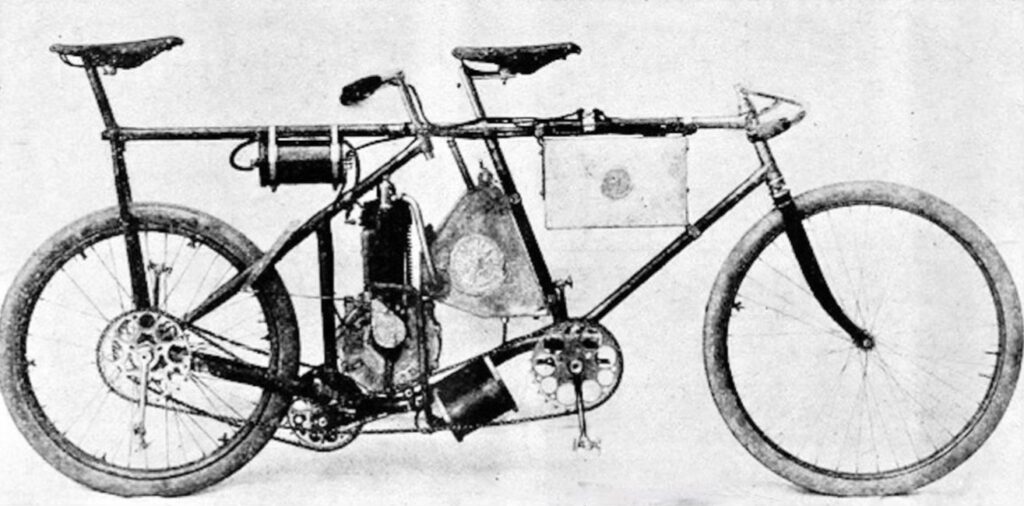

Showtime for Fournier and De Dion-Bouton motor power came on December 3 with the official opening of the U.S. winter indoor racing season, marked by a six-day “Bicycle Carnival” at Madison Square Garden. Fournier and Ricard were contracted for the entire week’s event, essentially as a side show; a novelty act to amuse racing fans during the downtimes between events. Instead, Fournier raised motor power to event-status. By the end of the month he and his “infernal machines” had become the star attractions at the Garden and motor pacing just as suddenly had become “the thing” in American cycle racing. Sensing opportunities, Fournier special ordered a De Dion-Bouton motor tandem for use during the upcoming West Coast cycling season starting in the new year. It was first used officially on February 22, 1899 in San Jose, CA. The De Dion-Bouton motor, supplemented by two men pedaling, marked an astonishingly new threshold for pacing. Fournier christened the fiery red machine the “Red Devil” and upon returning to the East Coast enlisted Charlie Henshaw as his motor tandem partner. The men took to the track clad head to toe in “Mephistophelean red” uniforms -- or as the press dubbed them, “devil costumes.”[8] Fans could not get enough.

Fournier’s sensational exploits over the past several months on the Red Devil was not lost on Metz. Jaded by his experience with the Jallu-designed electric pacer, he also became a disciple of petroleum power and the efficiency of the De Dion-Bouton motor in particular. So, while Fournier was spinning heads at the Garden, Metz was actively negotiating with the De Dion-Bouton Company. The Times reported as early as December 13, 1898 that “for some time past correspondence has been going on between American and French manufacturers, and by another month there will be a number of motor cycles on this side.”[10] Less than five months later Scientific American was able to announce that “the Waltham Manufacturing Co. of Waltham, Mass. will exclusively sell the product of the De Dion-Bouton Co. in the United States, and in addition to selling the regular machines now manufactured by De Dion-Bouton & Co. they will import the De Dion motors and make a complete line of Orient motor cycles and motor carriages.”[11] In a matter of weeks, when measured by size, weight and dependability, the best petroleum motor made in Europe would be bolted onto the best tandem bicycle frame made in America.

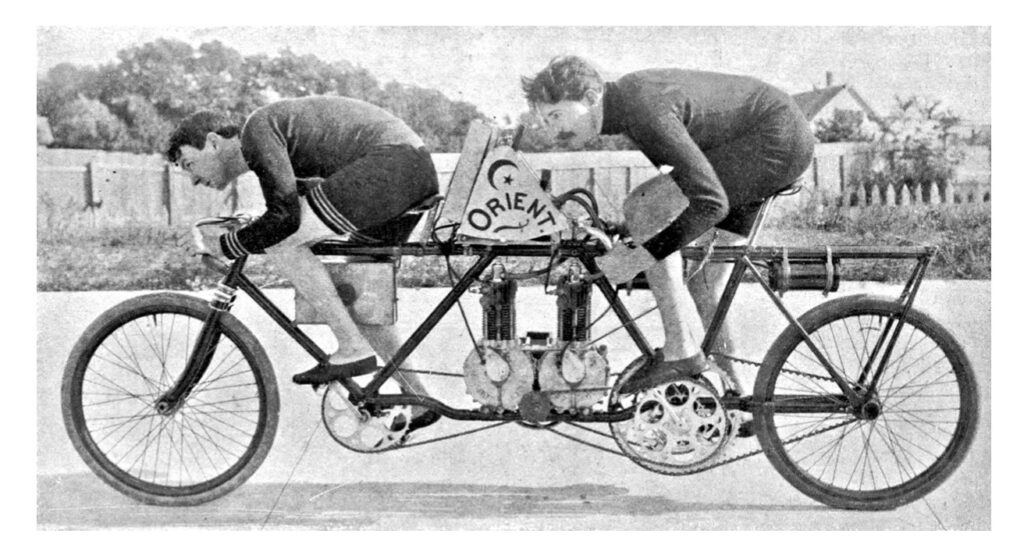

The historic Orient motor tandem made its debut on May 30, 1899 at the racetrack in Waltham, MA. Wheel and Cycling Trade Review published a story the next day with the caption, “The First and the Finest.”

“To set the pace, or to ‘Lead the Leaders,’ as the Orient people tersely put it, was again demonstrated when the Waltham Mfg. Co. turned out of its factory the first successful motor pacing machine made in America. It is not too much to say in praise of the new machine that it is the handsomest motor tandem yet produced in this country or any other.[12]

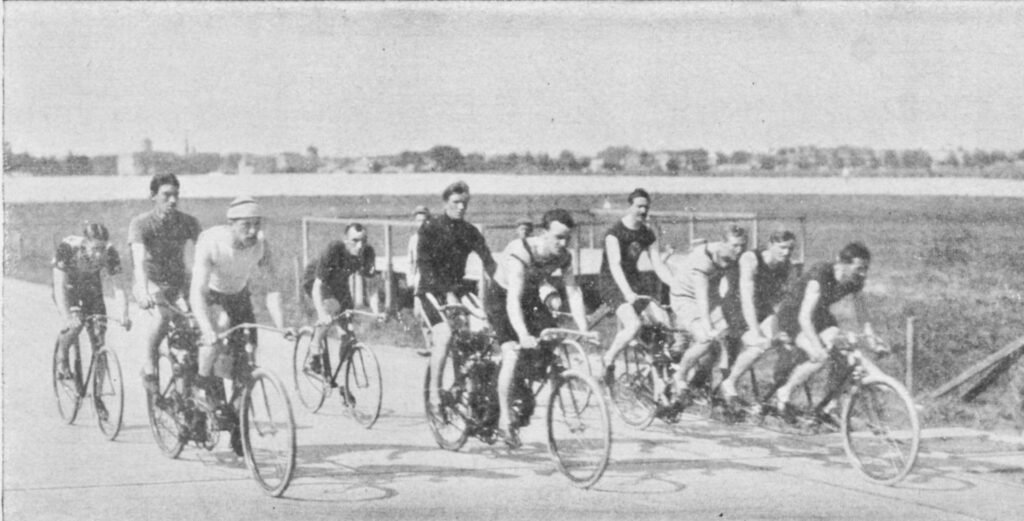

Then, on June 17 the stars aligned and pioneer motormen Charles Metz and Henri Fournier found themselves competing in each other’s shadow.

The Elkes versus Gardiner event was very good for the future of motor pacing in America and particularly good for the Orient motor pacer out of Waltham. Elkes and the Orient brand won the day, the Red Devil having slipped a chain and punctured a tire at various stages during the event (one of the Orients also broke down). However, to the surprise of many, including Metz, the Orient’s success did not defeat Fournier so much as convert him. The Boston Globe told the story on June 25.

“Fournier, who is not only an expert motor mechanic, but a racing man as well, was much taken with the design of the American motor tandem which paced Elkes in this race, and when Gardiner returned to Manhattan Beach to finish out his training, Fournier did not go with him, but stayed at Waltham and after some deliberation he made arrangements for two new motor tandems, which he will use exclusively this year in pacing and record work.”[13]

The Globe also made clear the advantages of the Orient motor tandem.

“American motor tandems which were used in the Elkes race were just as strong and much faster than the French machines, though only weighing one-quarter as much, and that is why he (Fournier) has decided to use American tandems this year.”[14]

Nine days later Fournier and Metz signed on the dotted line. The contract stipulated that Fournier would design and oversee the construction of state-of-the-art motor pacers using the Waltham factory’s significant resources, particularly its recent acquisition of exclusive U.S. agency status for all De Dion-Bouton products, including motors. Fournier would also do his marque racing and pacing exclusively for the Orient racing organization, bringing Charles Henshaw into the Waltham family by extension. For Metz the deal meant that the next generation of motor-power would appear in America under the Orient brand. For U.S. motorcycle history it was a new milestone – the successful commercialization of two-wheeled motor power.

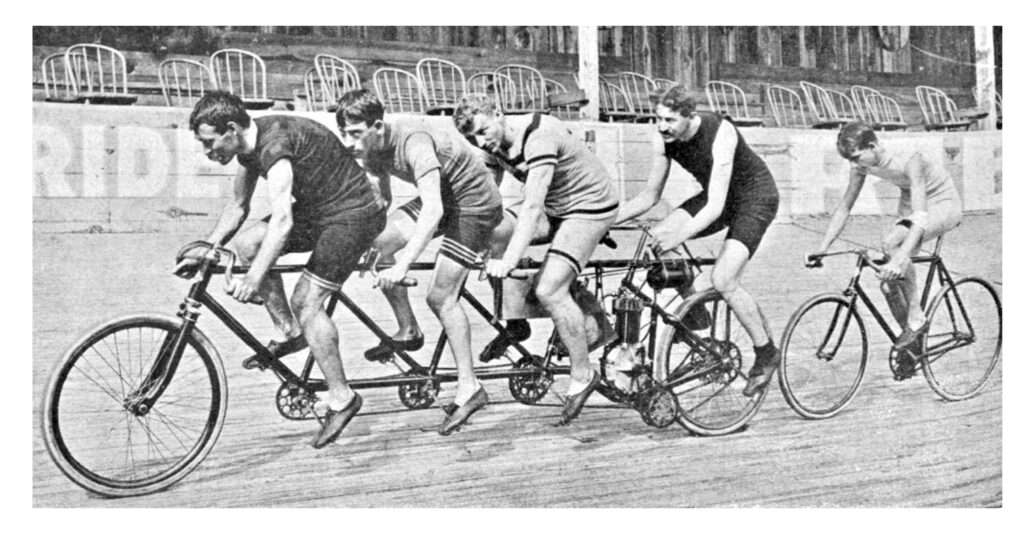

A half hour before the match was to begin, Elkes decided to take a couple of laps behind the Orient motor tandem as a warm up. By the second lap he was flying at a race-winning clip when the front fork of the Orient snapped just above the wheel hub and collapsed, the front wheel spinning off twenty feet down the track. The tandem pilots, Fred Kent and Walter Scherer, and Elkes, who plowed into the wreck, were all shaken up but not seriously injured. The Orient, however, was toast. (Witnessing the accident, Charlie Murphy told a reporter “he preferred railroad trains to infernal machines.”)[15] Elkes bravely decided to soldier on so as to not disappoint the six thousand racing fans and a substitute motor pacer was rolled out onto the track. It was a doozy.

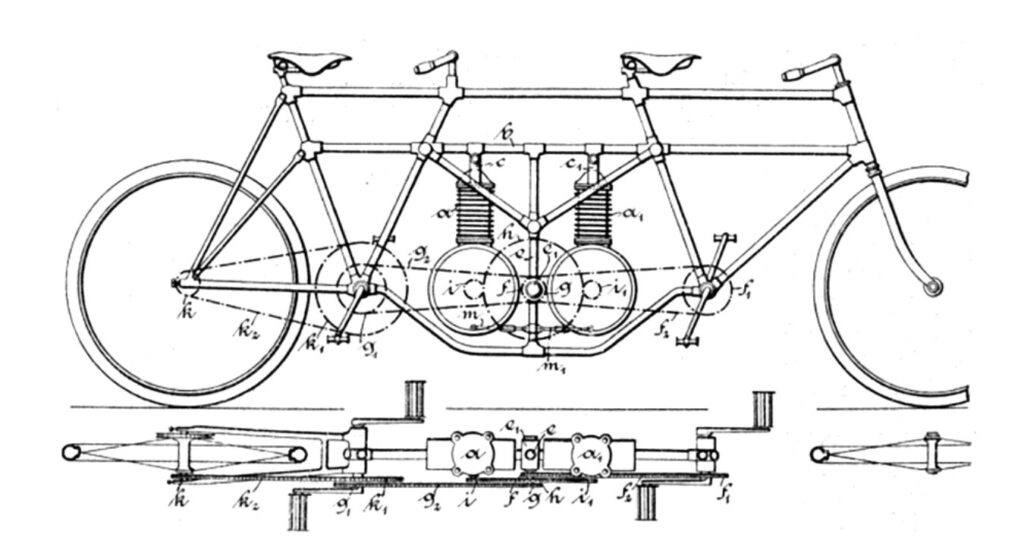

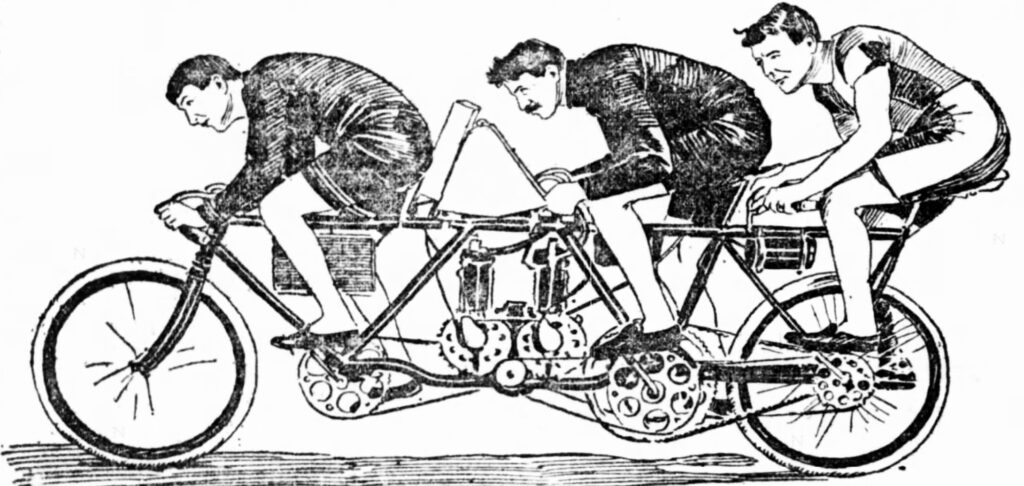

The incredulous Manhattan Beach fans watched Fournier roll out onto the track an extraordinary new addition to the Waltham family, the Orient motor quad. The New York Herald declared that it was “the first of its kind to be shown in this country, and (it) created a sensation.”[16] Fournier had taken the popular Orient quadruplet overhanging frame and installed a two-horsepower De Dion-Bouton motor just in front of the rear wheel. Suggesting that this introduction was not really a surprise (except for Gardiner) the motor quad came with its own special team of riders consisting of Louis Callahan on the rear seat as engineer, Austin Crooks up front as steersman and H.T. Allen and A. Ireland in the center seats. Beside the motor, the quad added four more powerful legs for pedaling when compared to the tandem; no small enhancement. One newspaper would later proclaim, “At the present time the infernal quad represents the height of achievement in the making of motor cycles.”[17] Elkes easily took the day, beating Gardiner (and Fournier and Henshaw on the Red Devil) by almost a full mile.

All past pacemaking commitments now met, on July 15 at Manhattan Beach it was Fournier on the rear seat of the motor quad with Austin Crooks steering and Arthur Porter and Hans Steenson taking the middle seats. The event was a 25-mile motor paced race between Harry Elkes, Burns Pierce and Earl Stevens. Notably, Stevens would be paced by Charlie Miller’s two-and-a-half horsepower Jallu motor pacer, one of the machine’s first appearances on an American track. Elkes, behind the quad, again won easily (the quad’s motor actually quit at the fifteenth mile, an Orient single having to pick up Elkes and the Jallu machine proved too fast for Stevens to follow).

“Motor cycles will work a revolution in the sport. The speed possible with them is incomparably faster than with human pace, and they are extremely dramatic to the spectators. Back of my quad I expect to negotiate a mile in 1:30, and I believe that a mile a minute can be made back of the big machines.”[18]

On August 3 Fournier and the Orient motor quad provided pace for Elkes at the Woodside track in Philadelphia, PA and took the two-mile world’s record away from Major Taylor. Fournier, however, thought he could do better and in August he went back to the drawing board and into the Waltham factory.

After a month of recovery, the tenacious Elkes was again behind the Orient double-motor triplet on November 26 at the International Athletic Park track in Baltimore, MD, for a series of record-breaking attempts. Frustrated by the previous failures, Metz sent his crack motor team to Baltimore -- Auston Crooks at the handlebars, Fournier at the motor-controls in the middle, and W.E. Mosher on the rear seat. But after the motor pacer suffered another series of breakdowns and near disasters, Elkes left the track in frustration. The powerful but unpredictable Orient machine was taken off the track and summarily disappeared from the American sports pages and the public eye.

Although frustrated and disappointed, the Metz-Fournier collaboration seemed to soldier on. Fournier stuck around Waltham, racing and pacing on Orient motor tandems and on his De Dion motor single, until the end of the year when it was suddenly reported that he was leaving America to compete in France “representing the Waltham Manufacturing Company.”[19] The picture got clearer when in February 1900 Metz announced that in addition to his fabled Orient bicycle racing team, he was forming America’s first motor racing team, challenging anyone anywhere to compete against his now dominant Orient motor tandems. On February 10, Fournier promptly boarded the steamship Luciana for Paris with a promise that “a complete all around outfit of motor cycles and vehicles—singles, tandems, quadricycles and automobiles,” would follow from Waltham. He said further that six special Orient motor tandems would be at his disposal to “tackle the foreigner at his own game.”[20]

It was the Metz strategy to have Fournier, the reigning “King of the Motor-Cyclists,” introduce America’s Orient brand to France and seed the Waltham Company’s advertising with victories on European velodromes. But while there were still motor tandems providing pace on the velodromes of Europe, real speed was now being provided by higher horse powered machines of three and four wheels. Fournier witnessed this firsthand just a month after his return to Paris when Henri Beconnais, piloting a tricycle powered by a huge five horsepower Soncin motor, established a new French speed record of fifty-seven miles per hour at the Parc de Princes Velodrome. The title of “King of the Motor-Cyclists” no longer belonged to Fournier.

Making matters worse, the Orient motor tandems never arrived in Paris as promised. The financially strapped Fournier was forced to purchase a used motor tricycle, what he later described as a “somewhat antiquated machine.” [21] In need of income, he entered the first motor event on the calendar, the Paris to Roubaix race held on April 15, 1900. Fournier’s machine was at least two horsepower slower than the next slowest machine and his name did not appear among the finishers. Fournier recognized, however, that the real racing action in France was with the automobile. A racing friend from back in the day, Fernand Charron, was then making a name for himself driving a twenty horse-power Panhard et Levassor motor car and graciously took Fournier on as a mechanic. By the end of the year he would leave Charron and join the Mors motor team with an automobile of his own. Fournier became the most successful international motorman of 1901.

Metz’s original plan to have Fournier operate as Waltham’s sales agent in Paris was dashed when the promised Orient motor tandems failed to arrive. Moreover, once Fournier was introduced to automobile racing any relationship with Metz evaporated. But Fournier had not been the only French racing mechanic building motor machines at the Waltham factory during this period. By late fall 1899, Metz had successfully recruited Albert Champion, a young and talented French track star, to establish records on Orient machines in America. Accompanying him was his manager and accomplished motorman, Dudley Marks. The arrival of these men at Waltham, and what they brought with them, might explain why the business relationship between Metz and Fournier ended so abruptly.

Dudley Marks arrived in New York on November 12, 1899 in advance of Champion, bringing with him some heavy baggage; two powerful Jallu motor tandems, each propelled by two-and-a-half horsepower Sphinx motors (even more powerful than Miller’s Jallu machine), and a Gladiator motor tricycle powered by a three-and-one-quarter horsepower Aster motor, capable of traveling thirty-two miles an hour and the first of its kind seen in America.[22] When Champion arrived, he brought with him solid business connections with the Aster Company and, importantly, with Veuve Leon Longuemare, the inventor of a new and improved carburetor. Before long both components would become essential to the development of the groundbreaking Orient-Aster motor single, the machine that would prove that one seat was better than two when it came to speed on the racetrack. The post-Fournier era had arrived with Champion and Marks.

While the Fournier-Metz collaboration lasted less than a year, it had succeeded in pushing the envelope of mechanized speed while inspiring the imagination of the cycling community as to the full potential of motorized, two-wheel machines. They also opened the door in the U.S. to the miraculous De Dion-Bouton motor and made them available (for a price) to anyone who had the notion to build a motor machine of their own. On September 18, 1899, it was reported that two Middletown, CT residents, a semi-retired champion bicycle racer named Oscar Hedstrom [read our article on Hedstrom here] and a local sales agent for the Waltham Manufacturing Company named Russell Frisbee, were about to do just that.[23]

Adapted from the book VELODROME RACING AND THE RISE OF THE MOTORCYCLE

by R. K. Keating

[1] New York Herald, June 27, 1899; Morning News, June 28, 1899.

[2] Detroit Free Press, July 2, 1899.

[3] Wheel and Cycling Trade Review, September 7, 1898.

[4] Berkshire County Eagle, May 3, 1898.

[5] Daily Mail and Empire, April 14, 1898; DeKampioen, June 3, 1898.

[6] St. Paul Globe, May 15, 1898.

[7] Wheel and Cycling Trade Review, October 20, 1898.

[8] Wheel and Cycling Trade Review, May 25, 1899; Morning Times, May 21, 1899.

[9] Cycle Age, May 11, 1899.

[10] The Times, December 16, 1898.

[11] Scientific American, May 13, 1899.

[12] Wheel and Cycling Trade Review, June 1, 1899.

[13] Boston Globe, June 25, 1899.

[14] Ibid.

[15] New York Herald, July 5,1899.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Daily Inter Mountain, September 30, 1899.

[18] Baltimore Sun, July 18, 1899.

[19] Wheel and Cycling Trade Review, January 25, 1900.

[20] Courier Journal, February 19, 1900.

[21] American Register, September 3, 1903.

[22] Wheel and Cycling Trade Review, March 9, 1899.

[23] Penny Press, September 18, 1899.