Henri Fournier’s ‘Infernal Machines’

On a cold winter day, in November 1898, a man was riding a motor bicycle on Fifth Avenue, New York. This may seem like a bland statement today, but in the Big Apple of then, the fastest way to travel was by bicycle or horse and cart; motorized transport was never seen. On seeing this unusual contraption traveling at a fast pace, a policeman tried to stop the rider, but had to give chase. On seeing the policeman, the motor cyclist ‘supposed the policeman wanted a race, and putting on about 25 miles speed, left the policeman behind at once.’(1) Unable to keep up, the lawman tracked the felon to his hotel where he was arrested; the machine was confiscated though the suspect released. The ‘criminal’s’ name was Henri Fournier, a Frenchman who had recently arrived in New York with various petroleum-powered machines.

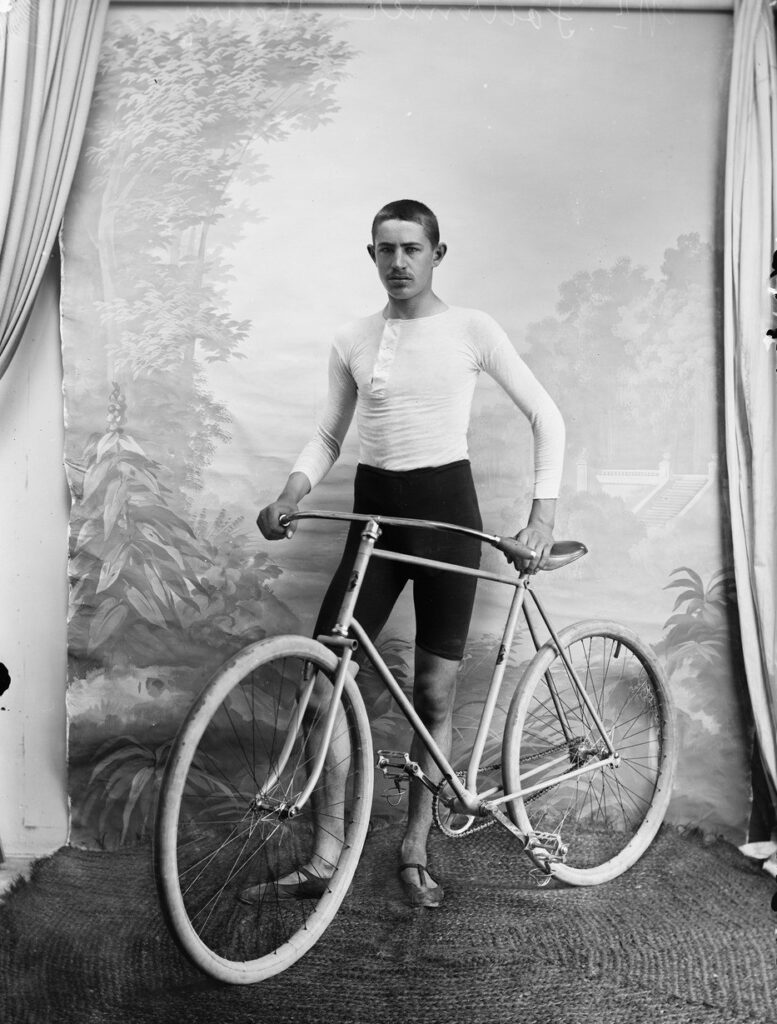

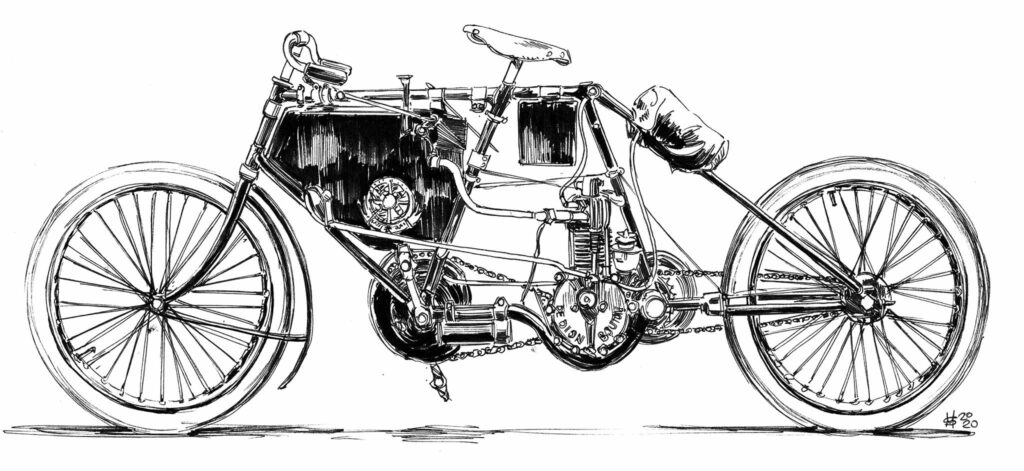

With this background in engineering and cycle sport, it’s no wonder Henri took to the invention of the motorcycle with vigour. One early account of Fournier on a motorcycle was made by Charles Jarrott (a British sporting gentleman deserving his own article), who in the spring of 1897 was walking through the Bois de Boulogne, a large public park on the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, and when he saw Henri flying along the road mounted on a motor bicycle. The machine was of an unusual length with the rear wheel extending ‘four or five feet behind the rider’. (2) Jarrott was so taken with the machine that he tracked Fournier down and bought the machine from him; he would later use this ‘sporty’ machine on the road, and on the cycle tracks of London.

A year after Fournier sold Jarrott the motor bicycle, he was in New York actively riding and promoting his machines in his flamboyant manner. Fournier’s antics on his motor tricycle were well-known due to an article published in American newspapers in September 1898. The article discussed how Fournier had reached 40 kilometers per hour on this new motorized machine. The writer’s tone emphasized the dangers of this emerging technology: ‘His performance suggests the grave danger that would accompany trips such as his on a road where similar machines are dashing along. Fournier alone on a level, smooth road, with no one to kill but himself, and no machine to smash but his own, is a sight sufficiently thrilling. Multiply the sight by 10 and imagine that number of Fourniers mounted on flying automobile tricycles, and the spectator cannot help thinking that this would make a novel and sure method of suicide.’(3)

From publications of the time it is clear that Fournier was very active in not only promoting his machines but demonstrating their potential on the track. Often, events with paced matches would also include a solo run by Fournier as part of the program. This would not only thrill the audience but also demonstrate that his machines were not a joke. It was also a chance for Fournier to put the machine through its paces at top speed and possibly set records. All this helped with promotion and development with what became known as Fournier’s ‘infernal machine’ by the press. Initially, Fournier had his tricycle and possibly a motorcycle, as mentioned previously it was later reported that Fournier shipped in two motor-pacing tandems, which arrived on November 21 via the steamship Normandie, just in time to be prepared for their debut at Madison Square Garden on December 5th. The 10 lap to the mile track at Madison was host to a huge meeting on December 5th word had got round that Fournier was to demonstrate his machines both solo and in an hour paced match between Edouard Taylore and Harry Elkes.

When Fournier mounted his ‘cumbersome machine’ the crowd was quick to cry out ‘choo-choo’ and ‘ting-a-ling’ as they found the sight of this strange machine something akin to a toy train due to the noise of the engine. Once the machine was up to speed and Eddie McDufee was in tow, the team reeled off an exhibition mile in just over two minutes. With the thrill of this new spectacle, the audience let out cheers of excitement. Fournier had demonstrated that this new technology, both in speed and excitement, was a perfect combination for a spectator sport such as track racing.

Fournier’s machine was still met with condescending howls as he came out onto the track, though as the participants got up to speed and Eaton and Elkes rode up behind their respective pace machines, the contest was most certainly on. In these races, the different teams start at opposite sides of the track, to make for a safe start and encourage a chase on the banked track. The initial pace was fast, with Elkes taking the lead, the second mile ridden in 1 min 57 seconds. By the third mile, Fournier was finally gaining on Elkes when the drive belt slipped, putting Fournier’s pacer out of action. Tandem teams were sent out to bring Eaton and Goodman through the rest of the race, but with the upset it was impossible to catch Elkes, who won by one mile and completed 20 miles in 41 minutes 41 seconds.

This was a small win for the human pace teams but this event was extremely important historically as it may have been a disappointment for Fournier, but this spectacle was witnessed by Oscar Hedstrom, who was competing in the professional matches that evening. Hedstrom at the time was making bicycles and competing, and would go on to form a partnership with George Hendee to produce the first Indian motocycle only three years later. One imagines that on seeing Fournier at Madison Square Gardens, the mechanically-minded Hedstrom would have been very interested in the possibilities of this new technology. Some have said that on seeing this pacing machine he saw the potential and the opportunity to better the Frenchman by producing his own pace machine. However, as far as my research has gone, this is just an assumption due to them both being at ‘the Garden’ on that night.

The proving ground of Fournier’s pacers would be in the middle distance events. One such match was at San Jose, California, on March 6. Fournier paced Orlando Stevens in a 10-mile match against Harry Gibson, who was paced by two triplets and three tandems in succession. Stevens beat Gibson by one and three quarter laps on the third of a mile track. Fournier didn’t miss an opportunity to demonstrate the speed achievable by his pacing machine, so, with Tom Barnaby steering, they achieved a 1 minute 35 second mile at the same meeting. The machine was pedal-assisted and Fournier believed they could achieve a 1 minute 30 second mile. Fournier’s activity on the East and West Coasts of the USA, along with developments in France, stirred the cycling press to discuss the future potential of motors… ‘If his motor pacing proves enough of a success early in the season to establish it as a feature or the solution of the middle distance game here, either more machines will be imported or our American makers will turn them out a home without much delay.’(5)

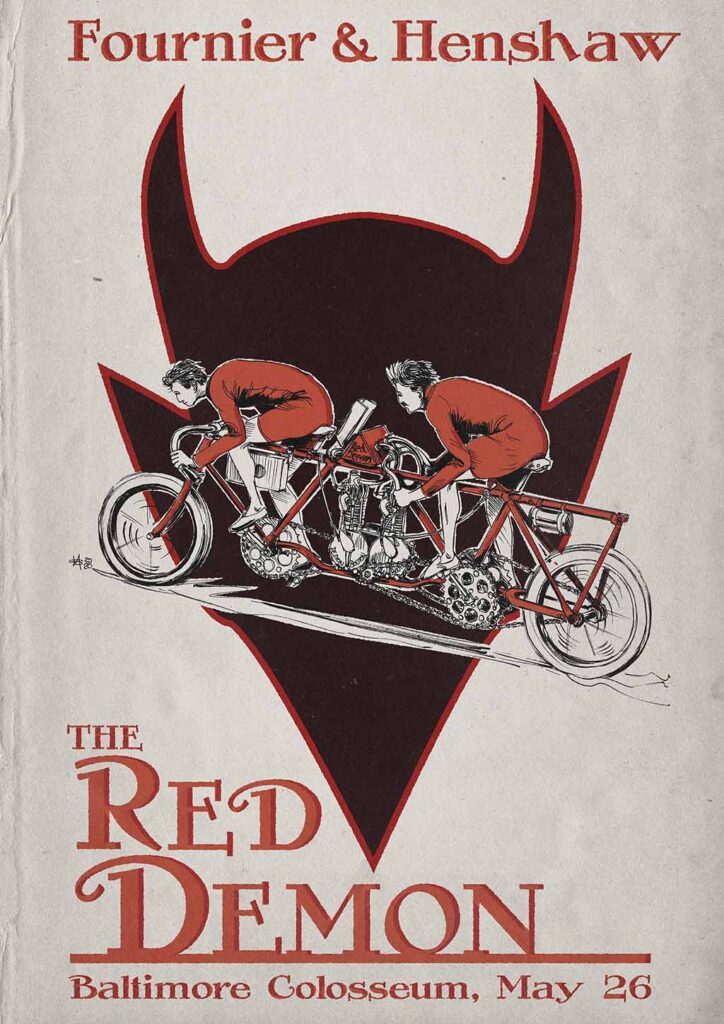

The tracks that were available at the time were designed to accommodate the speed of pedal power, not the increased potential of motor cycles. It wasn’t long before new tracks were being built in order to accommodate these higher speeds. One such track was the Baltimore Colosseum, which had its opening on May 26 1899. The event was very well attended, with 5000 people crowding the seating, possibly beyond its intended capacity. The colosseum had the steepest banking of any of the tracks built by Jack Prince, a racer promoter and track builder.

At this time, Fournier was the only person with a motorised pace machine for hire, though this was to about to change. American concern Waltham Manufacturing (builders of Orient bicycles) were now building their own pacing tandems and these machines used the De Dion Bouton engine with their own frames. Ten days after pacing with Fournier in New York, on May 30 Harry Elkes was riding an exhibition five miles in the slipstream of an Orient motor tandem at the Waltham track, Massachusetts. This was not a record attempt but a chance for the Orient pacer to be demonstrated with one of the best middle distance riders of the time. The ride was successful and proved to the press that Waltham could build a competent machine and, as a result, Fournier risked losing his monopoly.

On top of American petroleum tandems being built, there were also reports of racers such as Charles W. Miller, Edouard Taylore and Tom Linton importing machines for their own use and to rent. Within the same report it is stated that Fournier was now working with Tribune bicycles who were providing triplets made ‘to fit the French motors he intends to import to America.’

‘The Waltham machines that Elkes will ride behind will have the same motor as is fitted to Fournier’s machines, the De Dion, so that other things being equal, the victory will lie with the motor engineer, with him who is the better judge of pace and can regulate it more judiciously for his follower. But we Yankees are quick to learn a new game, and weeks of practice at Waltham will teach the pilots of Elkes a great deal.’7

After the Orient exhibition ride at the end of May, Fournier and Henshaw travelled to Waltham to pace Gardiner against Elkes in a 20 mile match. Elkes had two Orient Tandems and a human quad team as backup. The match was back and forth, with Gardnier showing great form behind Fournier. Elkes kept pace but the Orient machine tended to jump, causing Elkes to lose confidence. A series of punctures on both sides caused issues, but with Fournier only having one petroleum machine, Gardiner was forced to ride up behind Elkes, while Fournier found an alternative. He apprehended a triplet from the sidelines, with an amateur in the middle seat. It was not long before the amateur ‘objected to the kidnapping and dismounted on the fly.’ For the last mile a human quad came out to bring Gardiner home, but he was too far behind to catch Elkes, who finished the 20 miles in 37 minutes and 3 seconds.

‘Fournier says that although the French people undoubtedly build the best gasoline motors, we are many years ahead of them in the construction and design of our frames and running gear. He is of the opinion that the American motor tandems which were used in the Elkes race are just as strong and much faster than the French machines, though weighing only one-fourth as much.’8

We will finish this part of Fournier’s story with a high speed event at the Manhattan beach track on September 4, where pacing tandems were run in their own race. It was a 25 mile race with five teams competing for a prize of $500. Four teams were riding Orient tandems, with Caldwell and Judge riding a Jailu & Co. machine. Without the concerns of pacing a cyclist, the participants could run at a fast pace. Previous reports would have had the audience thinking that this was a pretty even match with most of the machines from the same manufacturer, but the twist was that it was the Jailu & Co. machine that led whole the race, while the others struggled amongst themselves. It was stated that the Jailu & Co. had its motor muffled and sped along silently with no ‘clickety-click’9. The superior speed attained was laid to a more perfect form of carburettor than those employed on the American machines.’ It is interesting to read that it was possibly the carburetion that was the deciding factor. There is a certain amount of irony that Fournier came to America with advanced knowledge and having been in America for nearly a year, he had possibly been isolated somewhat from French developments in tuning due to his immersion in the American industry.

Fournier would go on to continue his pacing activities until he moved on to racing automobiles in 1902, when he joined the Mors racing team in France. In his first year, he won both the Paris-Bordeuax and Paris to Berlin races, and he would also return to America to set a new mile record with his automobile. Fournier was a born racer competing from a young age all the way up to the age of 31 in 1902 when he set a new land speed record of 123km/h. All these are great achievements but his adventures in America between 1898 and 1899 must not be forgotten as they were hugely influential in kickstarting the world of motorcycle racing, especially on banked tracks.

1: The Cycle Age and Trade Review volume 22 p26 (Smithsonian Library)

2: Ten Years of Motors and Motoring, Charles Jarrott (1906, London, Grant Richards)

3: The San Fransisco Call September 4, 1898

4: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 22 p460 (Smithsonian Library)

5: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 22 p774 (Smithsonian Library)

6: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p120 (Smithsonian Library)

7: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p176 (Smithsonian Library)

8: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p220 (Smithsonian Library)

9: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p486 (Smithsonian Library)

10: Photos courtesy Bibliothéque Nationale de France

This is what I open this website for each and every morning . And when one like this shows up …. well .. suffice it to say one read is never quite enough … not to mention following up on some of the references .

Hmmm …. too bad Fournier’s name didn’t translate to a lasting M/C brand . It’d of been fascinating to see how he and his bikes would of evolved over the years especially with the added influences of flight and autos

Hmm … bikes .. M/C’s .. planes … cars … damn …. the only thing missing is steam trains

Two huge thumbs up and thanks for putting a smile on an otherwise crap week

😎