Guest post by David Lancaster.

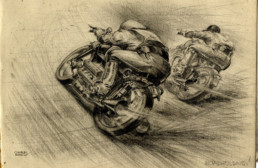

Paul Simonon’s first memory of motorcyclists is etched in his mind. “It was in Paddington, where I grew up,” he recalls. “Rockers would hang around the 59 Club there, tearing up and down on bikes. One time, a bunch of these characters started wolf-whistling my mum. I said: ‘Who are they?’ – like she knew them. We kept walking. But something lodged. These things are very vivid when you’re a kid – these people racing around, the leathers like a suit of armour.”

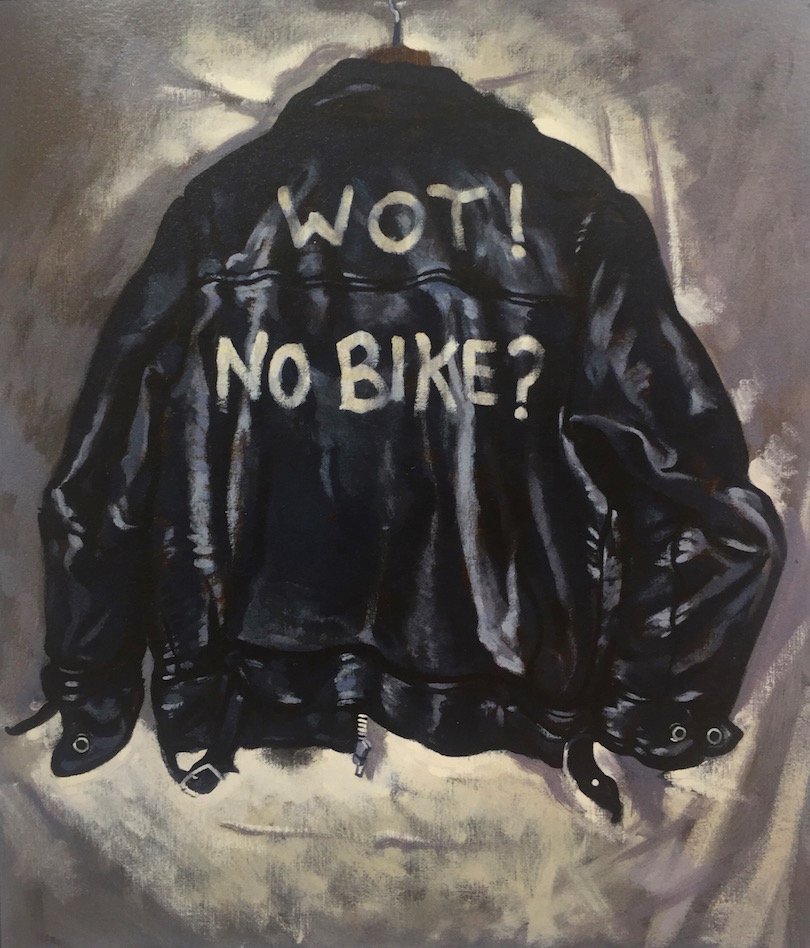

Fast forward some years, and the former Clash bassist’s new series of paintings and book Wot No Bike distil a lifetime of painting and riding motorcycles, and the enduring appeal of the classic biking and punk rock uniform: the black leather jacket.

The Clash were perhaps the coolest and most enduring of punk bands. In addition to his bass playing and occasional song writing, Simonon’s artistic sense and drive also led the band’s distinctive look and stagecraft. Since the band disbanded in 1986 and frontman Joe Strummer passed away in 2002, Simonon has played with Damon Albarn’s groups Gorillaz and The Good, the Bad and the Queen.

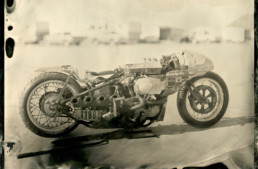

But painting came before bass playing. As did motorcycling – a later brush with two-wheeled culture came when when a scholarship took him to Byam Shaw School of Art in central London. “There was girl there called Dianne. She was a short little girl, but she had this great big British bike,” he recalls. His head was turned onto British bikes.

The Paddington of Paul Simonon’s childhood, his home just minutes from the 59 Club, still bore the scars of its semi-industrial past. A nexus of road, rail and canal trades meant the area’s streets were a potent brew of workshops and pubs servicing the rail and canal industries. In many ways it was still the Paddington captured by one of his favourite artists, Algernon Newton, dubbed the ‘Canaletto of the Canals’ after his 1930 view of The Regent’s Canal, Paddington. Newton’s work, according to critic Richard Dorment, captured “vast featureless brick blocks built during the industrial revolution that had by then fallen into a state of dereliction”. Even in the 1950s and 60s when Paul was growing up in west London this remained the case – splashes of colour, such as they were, were mainly the state-monopoly red of Routemaster buses and Giles Gilbert Scott’s robust telephone boxes.

The area – “holding on to its soul today, just” according to Paul – housed the 59 Club in the hall by St Mary’s Church. It was run with a benign zeal by Father Graham Hullett, a committed motorcyclist and man of the cloth who, according to regulars, “wore his faith lightly”. For Lenny Paterson, 59 Club regular who was later to reignite so much with his Rocker Reunion Runs of the early 80s, “the 59 Club in its Paddington heyday was a magic time.” Not only did it offer a place for London’s young rockers to ride to, meet at, and fall in love in but in 1968 its private members’ status meant it was able to screen László Benedek’s The Wild One for the first time in the UK after the film was banned in the late 1950s.

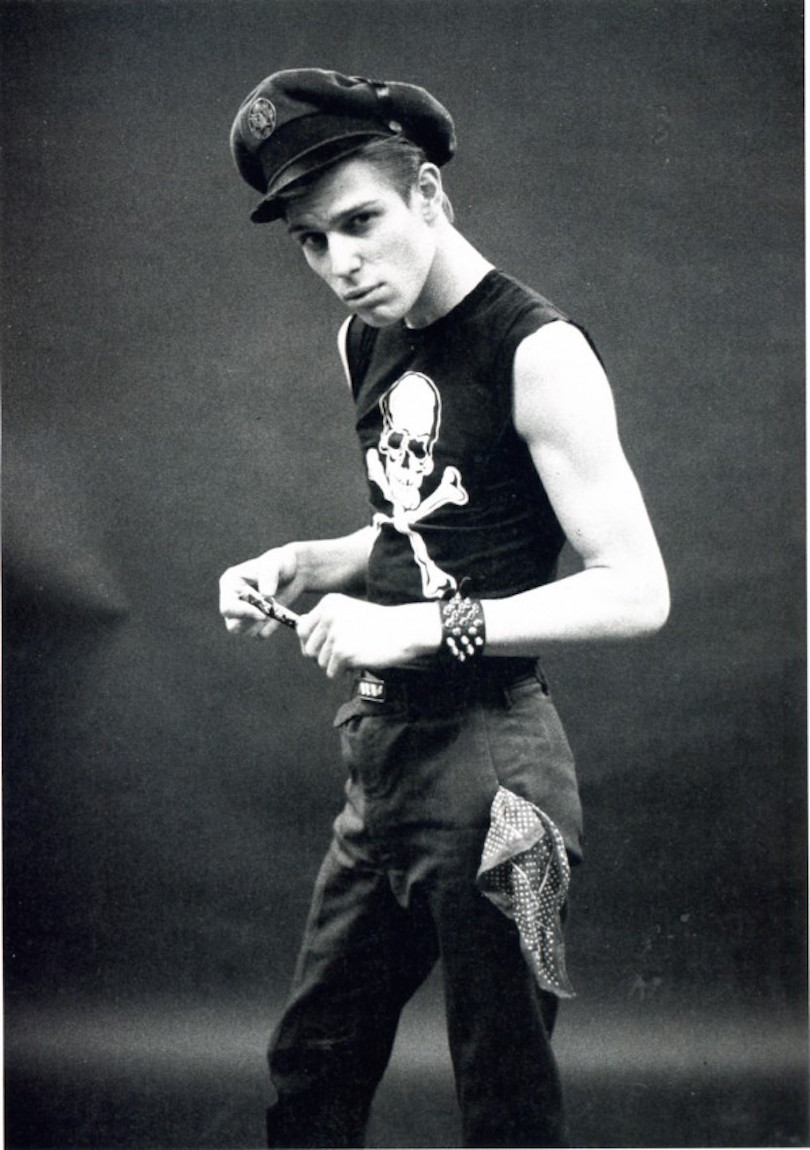

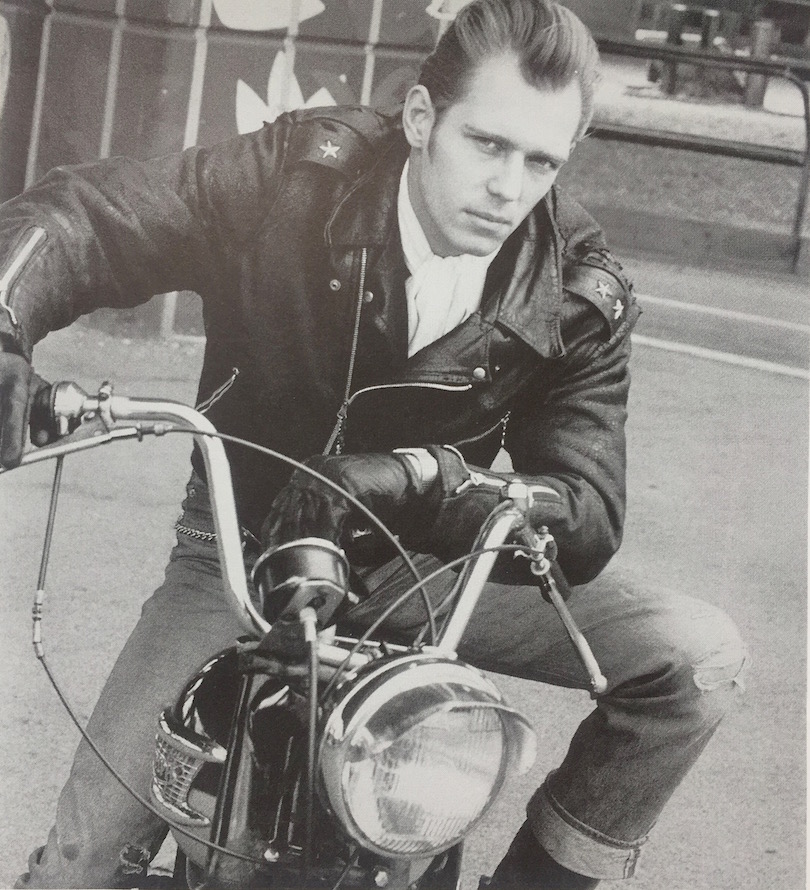

The classic 1950s and 1960s rocker look of black jacket, straight-legged denims or leathers which had struck Paul in the late 1960s would re-emerge in punk of the mid-1970s, but not without a struggle. The greasers and teds of the 70s would cross the street to start a fight with a punk. As Joe Strummer observed in a late interview, punks took their uniform and “tore it up… which they saw as disrespecting their kit.”

Yet, despite fights on the King’s Road between teds and punks, the links of style and personnel between music and motorcycling had never been so close since the 1950s. As fellow punk pioneer and classic motorcyclist David Vanian of The Damned says, “Rock and roll of the 50s came and went really quickly, and didn’t get a chance to mature. The look was clean, sharp.” The links between the two struck legendary DJ John Peel too, seeing the “raw energy of early rock and roll” re-emerge in punk’s guitar-led attack compared to the stoner-indulgence of much 1970s music.

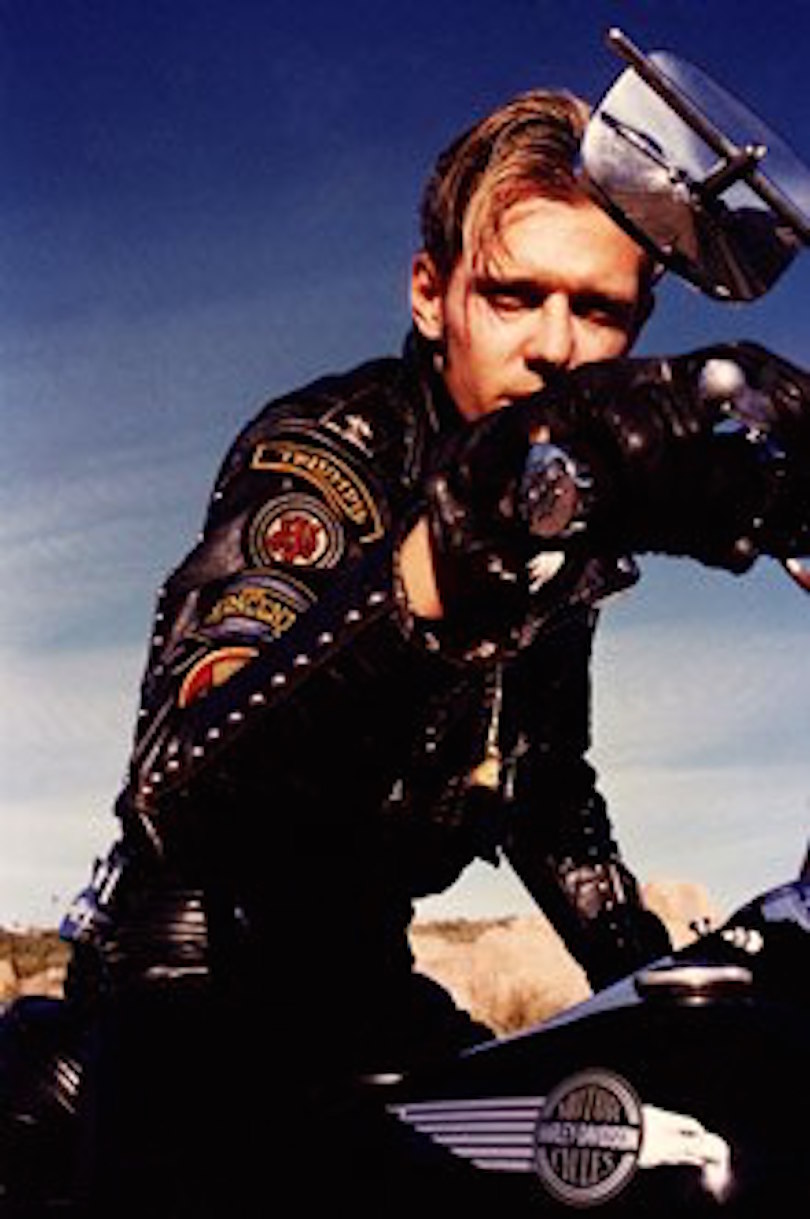

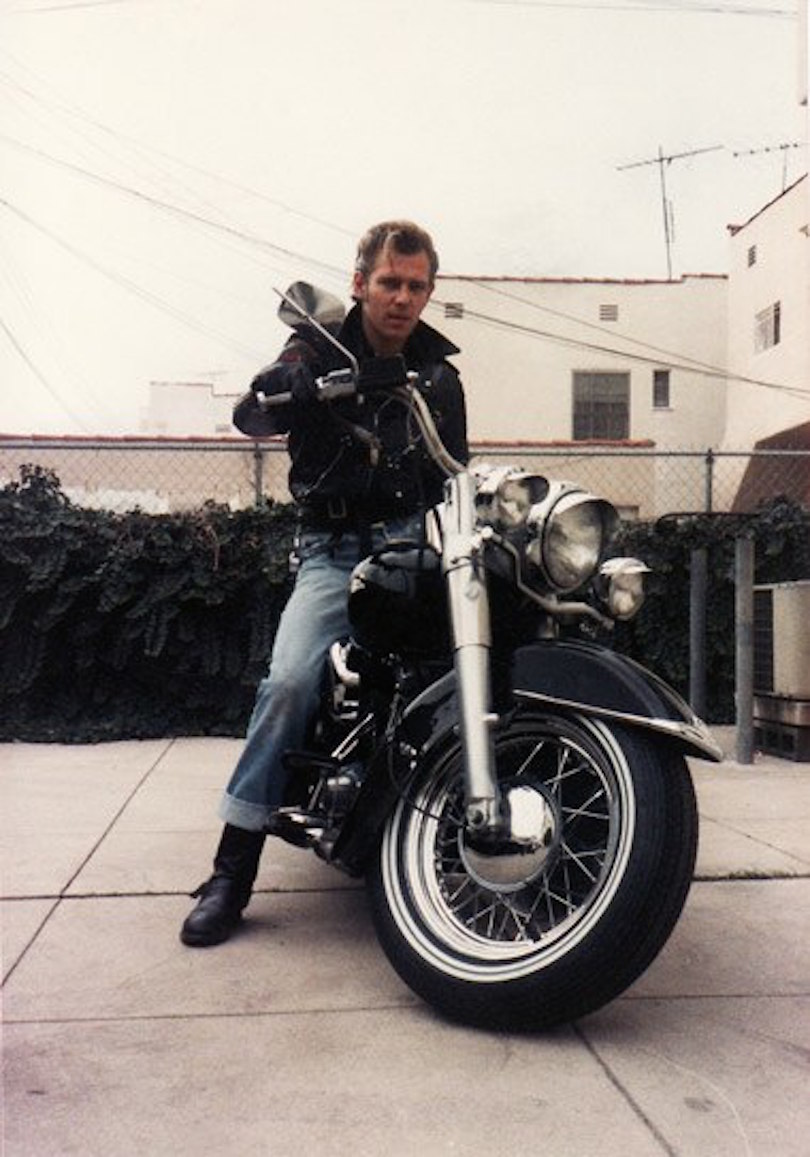

It was fellow musician, the late Nigel Dixon from rockabilly outfit Whirlwind, with whom a shared love of motorcycles – and chance – led the two to take up biking Stateside and a further chapter in Simonon’s two-wheeled and musical life. “After the break-up of The Clash, we spun a globe – to see it land on El Paso. So we sold our bikes in the UK, and went to live in El Paso, and bought these two old Harleys,” he recalls. After riding across from El Paso to LA, the two pitched up at a bar to be met by a girl Paul knew from London. “Paul, I can’t believe you’ve got a bike like Steve’s!” she said. And so ensued recording sessions with Bob Dylan and months riding around LA on old Harleys with Steve Jones from the Sex Pistols and others, “Like a long, leather motorcycle snake,” as Paul puts it.

But the major influence on Paul Simonon’s motorcycling was the author, eccentric and Russian art expert, Johnny Stuart, introduced to him by Dixon. “The first Triumph I had was a white and gold 3TA”, Paul recalls. “And then a 5TA off a mate of Johnny Stuart’s. We’d all hang out, go for runs. I got to know him very well.”

Stuart was a key figure in late 70s and 80s London classic motorcycling, and Paul’s life at the time. Not only did he pen the seminal Rockers! in 1987 which collated and chronicled the rockers’ movement (Paul is photographed in it) but he built up an archive of original jackets and a network of friends and riding buddies who crossed boundaries of class, work and background. Paul remembers a “complete one-off – a scholar, rocker, great host.” Appointed Sotheby’s expert in Russian icons in the 1970s (his rival at Christie’s dubbed him the “greatest authority on Russian art outside of Russia”) he passed away at the age of just 63. A jacket of Johnny’s features in Wot No Bike.

“Johnny loved every aspect of 50s and 60s motorcycling,” says Paul. “The look, the bikes, the sound. Like everything he did, he became an expert.” His lodgers, Crispin Ellis and Trudi Gartland, would park their bikes next to their ground-floor double bed after a run, and Stuart’s Colville Mews house was, until the very end of the illness which took his life in 2003, a heady mix of Russian icons, dismantled Triumph engines, rockers and musicians such as Siouxsie Sioux, Brian Setzer from the Stray Cats and, of course, Paul. “You’d come home and there’d be a few bikes outside,” Trudi recalls. “But also a black limo, surrounded by bodyguards, as Johnny was valuing a piece of Russian art for some high roller.”

There is a quiet determination about Paul Simonon. He’d been playing bass for just six months before The Clash’s first recording. Yet, just a few years later, the band cut London Calling, dubbed by Rolling Stone magazine the best album of the 1980s. Simonon’s reggae-infused bass is a key part of such epitaphs: on the album’s title track it is as distinctive as Herbie Flowers’ playing on Lou Reed’s Walk On The Wild Side, adding a muscular energy and attitude to the limited canon of bass-lines you can you hum, but which also make the record. “The only punk band with groove,” according to Scott Rowley.

His painting displays the same application. For an earlier series of London landspaces, part of the process was “just getting out there, on a bridge, in the wind and rain, and painting,” he says. “I’d avoid eating or drinking – you didn’t want to leave the stuff unattended, or pack it up for a break. So I just carried on, with the odd smoke, for hours.” These days, his Paddington studio is warmer but the same work ethic is evident as the visitor takes in several canvasses on the go. He likes to “keep painting through”. Such commitment extends to being imprisoned for two weeks after working on a Greenpeace ship as a chef, his background unknown to his fellow activist-inmates.

Wot No Bike captures much about classic motorcycling, in elegant still-life. The artist himself is an off-screen presence to a jacket on a chair, or gloves, cigarettes and crash hat resting after a run. “A leather jacket never ages,” he says. A jacket swapped with Joe Strummer for one of Paul’s earlier works – “he couldn’t believe I would paint washing up, in a sink… so we swapped” – carries the title of the book and exhibition.

The paintings are refreshingly traditional, in the realist tradition Paul admires. And in the dark creases, distress and crumpled leather it speaks volumes of two-wheeled experience, both good and bad. “Johnny Stuart used to urge me to ride in the rain more,” remembers Paul. “I couldn’t see the appeal much then. But now he’s no longer with us to tell, I really get it: the balance of power and traction. The focus.”

Simonon’s daily ride is a lightly modified Hinckley Triumph. “The funny thing is when my mum first saw me with my bike, she said: ‘Oh, that brings back memories – your dad used to have a bike like that, a Triumph.’ Then I found out he was a dispatch rider for the army, in Kenya. These things come out. And now one of my sons has a bike. At a young age, he would say to me: ‘Dad, I want to make something that can propel me somewhere.’ And I’d say: yeah, it’s called a motorcycle.”

………………..

Based on his Introduction to Wot No Bike © David Lancaster

Pictures © Dave Norvinbike as marked, and others

The exhibition runs at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London SW1 from January 21 until February 6 (www.ica.org.uk).

Copies of the accompanying book available from Amazon and signed copies from www.paulsimonon.com.