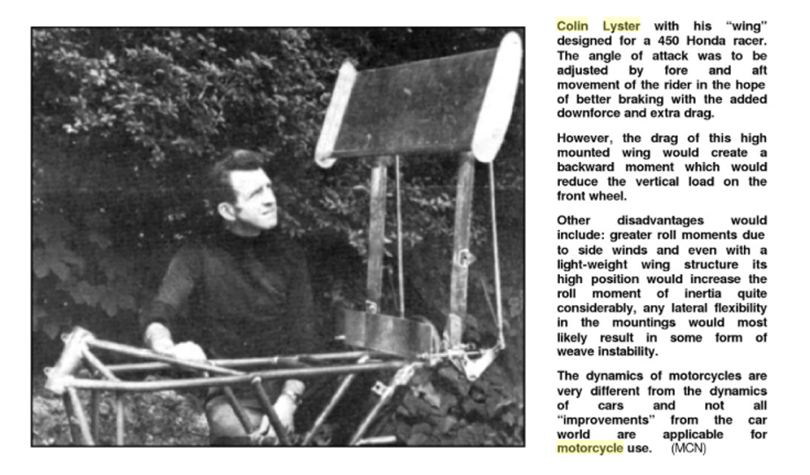

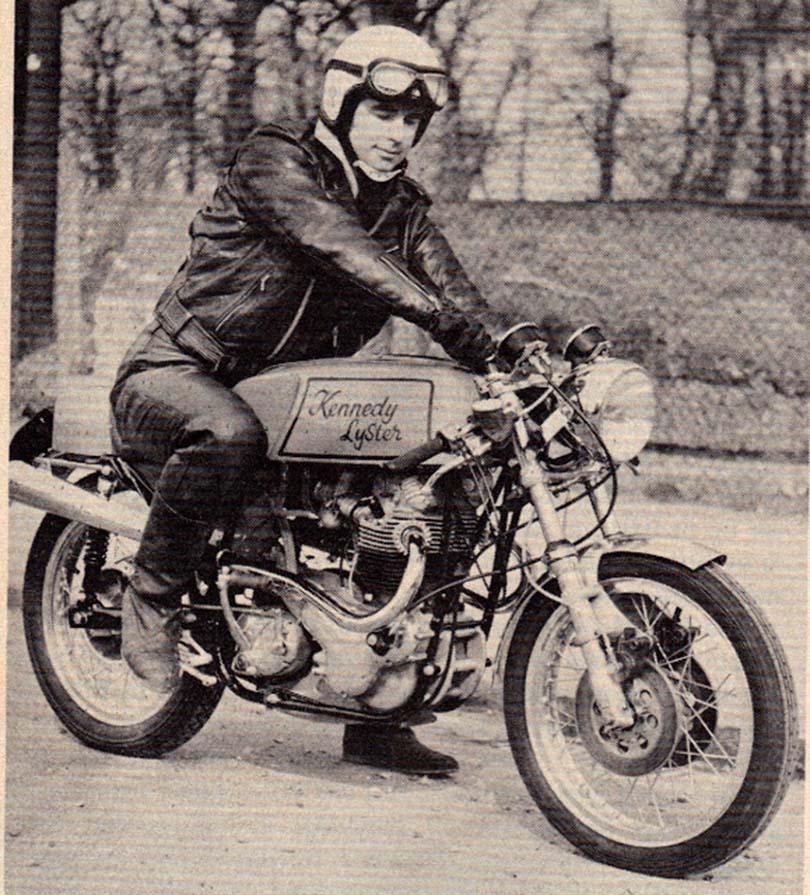

Colin Lyster isn’t a household name, unless you’re a hardcore café racer fan, in which case, he’s a demigod on par with Dave Degens and the Rickman brothers. A former Rhodesian road racer, Lyster moved to Britain in the early 1960s, and set about re-framing Triumphs and Hondas to reduce weight and improve chassis stiffness. His frames were ultra-rigid and half as heavy as comparable Norton item; he typically discarded the lower frame rails, using the engine as a stressed member, and thinwall tubing of smaller diameter than considered prudent for a street machine.

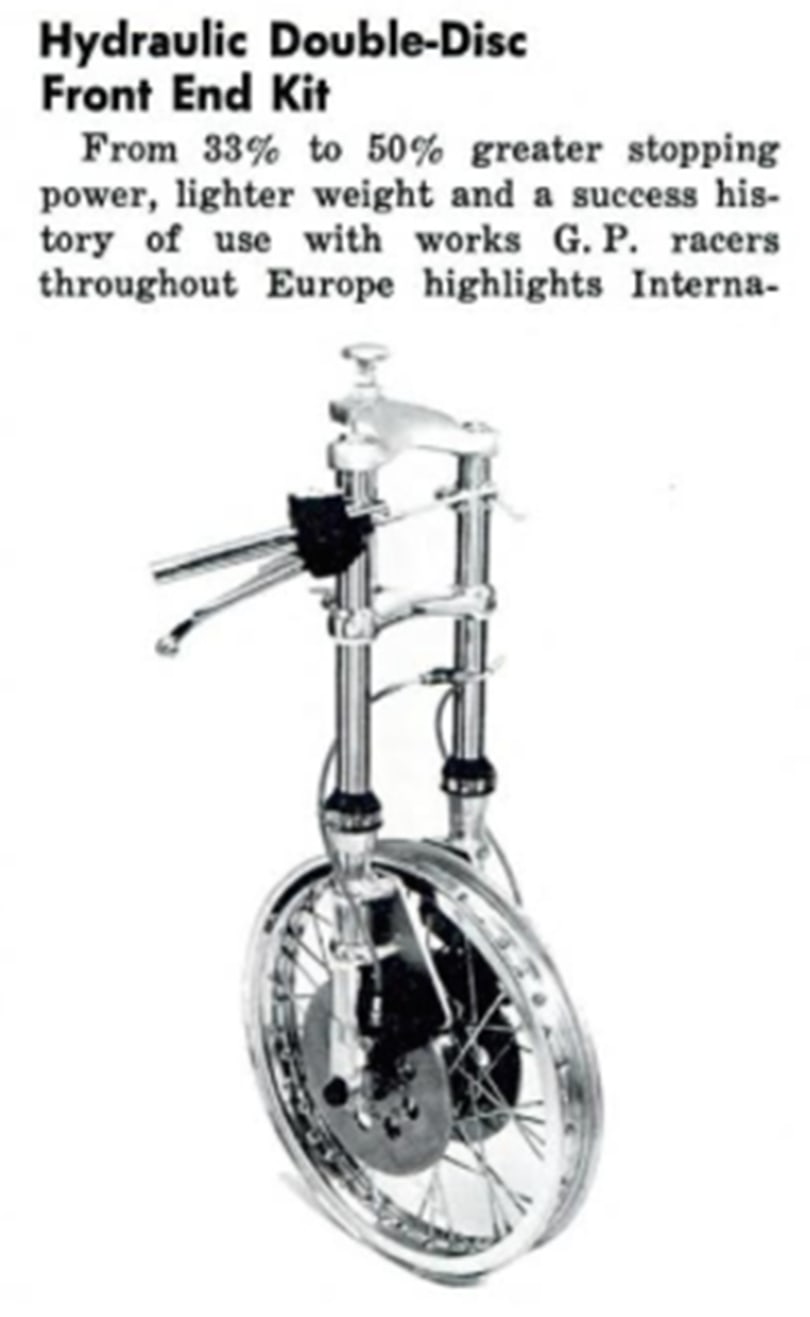

Still, hotshot riders can’t resist a road racer with lights, and a few Lyster-framed roadsters can be found in books on the café racer craze. Lyster’s frame output was low, but his impact on the industry was outsized. He developed the first triple-hydraulic disc braking systems for motorcycle racing teams in the mid-1960s, using specially adapted Ceriani road race forks and his own fabricated swingarms, with his own cast iron discs. Triple juice discs became a must-have item on winning road racers; Lyster began selling kits to the public in 1971. After failing to interest the British motorcycle industry in his product, he sold his patents to AP Lockheed. Ironically, it was Honda who first used hydraulic discs on production motorcycles, in 1968. Still, it was Lyster’s patent, and he changed motorcycling forever.

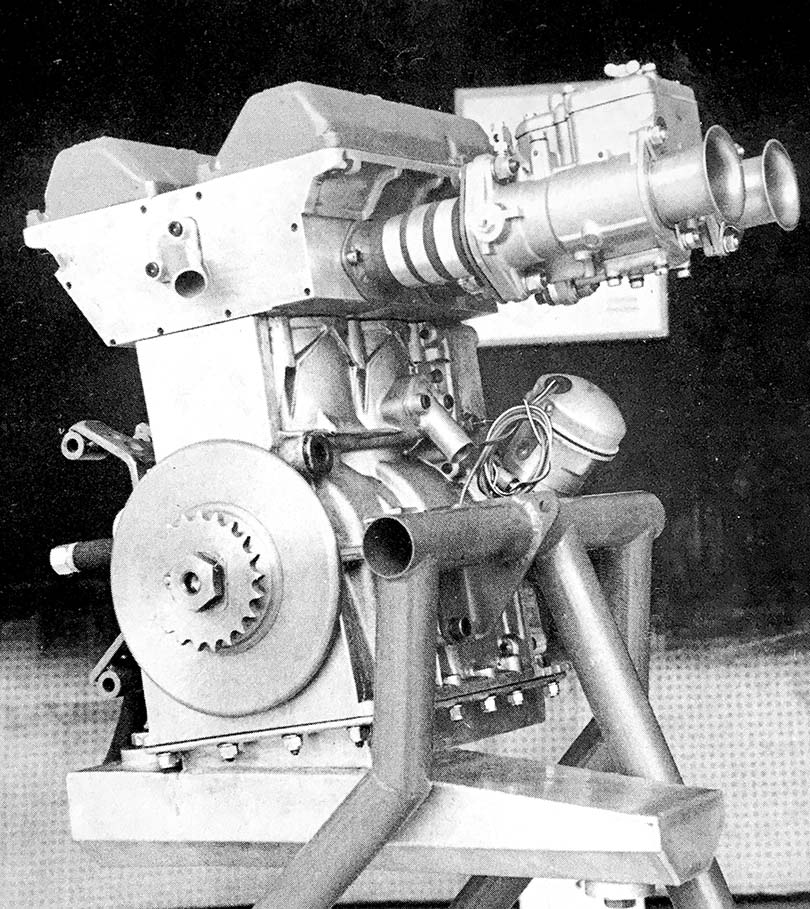

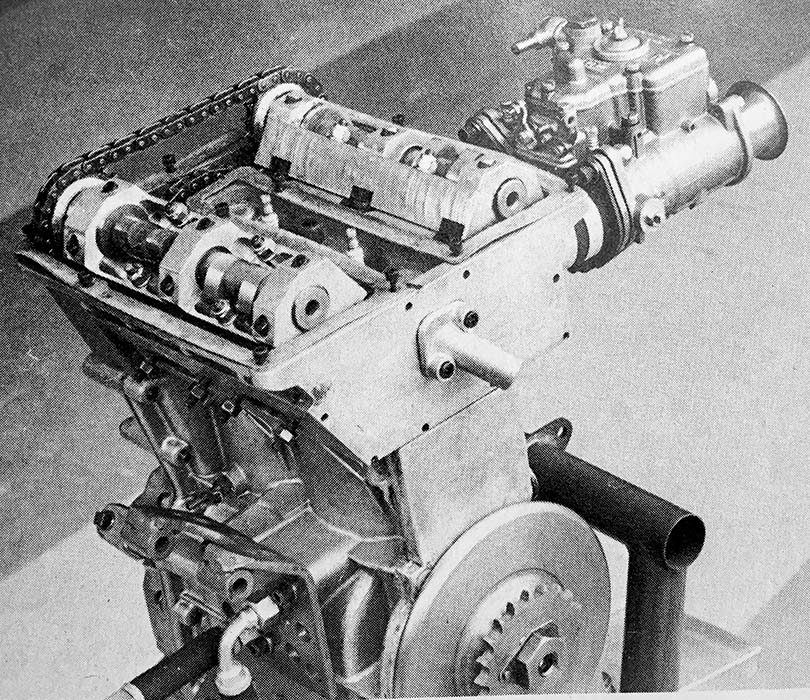

By the mid-1960s, the British motorcycle industry had given up on Grand Prix racing, but enterprising builders hadn’t. Colin Lyster thought a reasonably-priced, competitive engine could be built from automotive parts, and he cut a water-cooled 1000cc Hillman Imp 4-cylinder car motor in half, and built a DOHC, 8-valve cylinder head for it. Interestingly, the Imp motor was designed by Leo Kuzmicki, the Polish ‘janitor’ who was ‘discovered’ by Joe Craig, race chief of Norton, as having been a research scientist in combustion theory before becoming a WW2 refugee. It was Kuzmicki who kept the Norton Manx engine competitive a decade after its sell-by date, extracting ever more power from the aging single-cylinder design. After leaving Norton, he moved to the Rootes Group, and designed the extremely reliable and very fast Imp motor.

As reported in Cycle World in July 1968, Lyster’s Imp-engined ‘Lynton’ racer was a collaboration with Paul Brothers, and used an ultralight Lyster full-cradle frame, with his own triple disc setup. The cylinder head is a chunk, and the side-draft Weber DCOE carb doesn’t inspire confidence that the watercooled engine is light. The builders claimed 60hp from the motor, which used a 180-degree crankshaft, a modified Hillman part, as were the rods. Slipper pistons from Mahle and cams by Tom Somerton painted a picture of speed, and the projected price of £300 undercut a Matchless G50 single-cylinder SOHC motor by £75. Orders were not forthcoming, though, as the project needed more development, and it remained yet another British ‘what if?’ It seems only the prototype motorcycle was built, although Lynton offered a full four-cylinder version of its special cylinder head to Imp rally drivers; a few of these are floating around, including rumors on one cut in half for a motorcycle!

Britain’s H&H Auctions turned up the sole Lynton racing motorcycle; it’s an uncompromised beast with a pur sang pedigree, and a lot of near-forgotten stories surrounding its build. Colin Lyster moved to the USA in the early ‘70s, and worked with Canadian national champion road racer Ed Labelle to build Lyster-Labelle racers, using Triumph Bonneville motors in lowboy frames with triple discs. Only a few were built before Lyster moved on to New Zealand, where he carried on with other projects until his death in 2003.

Related Posts

July 8, 2017

The Vintagent Trailers: Mancini, The Motorcycle Wizard

The mechanic that helped debut five of…

I had given up road racing in 1967 in order to get married (bad idea!). My good friend Nev Shaw was a mechanic working on the Lynton Racer. I used to go to Colin Lyster’s garage in Fortis Green Road in the evening to provide an extra pair of hands when running up the beast on rollers. The half Imp engine had no flywheel and would respond very quickly to the throttle but shut down equally fast on the overrun. As an electronic engineer, I had designed an electronic rev-counter to rival the very expensive German Krober units which were the only electronic version produced at the time. Colin agreed that I should produce the electronics and he would produce the cases, mountings and do the marketing. During that time Nev rang me up to ask if I was interested in being ‘auditioned’ to ride the Lynton Racer as their professional rider. I bit his arm off and agreed to be at Snetterton the following Monday. The Friday evening before I had another call to say that Lynton Racing had gone into liquidation as Colin owed several thousand pounds to the company producing the cylinder head castings.

The Lynton Racer was a big ‘what If’ but it was an equally big personal ‘what if’ for me. Oh well……

Jim, what an incredible story! The British industry in the ’60s and ’70s was one big ‘what if’, but we rarely hear the personal stories of obscure makes like the Linton!

all the best, Paul

Thank you Paul. It certainly was an interesting time to be around.

Best wishes

Jim

Paul, just an afterthought; I read some time ago that Colin Lyster had been involved tuning rallycar engines and then moved on to off-shore power boats when he moved to New Zealand. Not unsurprisingly, he did all sorts of clever things with inline fours and V8s which elevated him to legend status downunder. There is a website forum ‘NZ-hotrods’ which refers to some of his deeds. An incredible man!

Cheers

Jim

wow just come across this article, brought a tear to my eye, thank for the kind words about my dad colin lyster

Your dad did some amazing work!

Hi Michael. Way back in the fifties I was friendly with a guy by the name of Geoff Mason and through Geoff I met your father who owned two Norton racing bikes, one a 350cc and one a 500cc. Your Dad worked out in the sticks of Southern Rhodesia on a gold mine so couldn’t race on some weekends as he would be doing a shift underground. Geoff and I looked after his bikes in Salisbury and did all of the mechanical work to get them ready for the next race meeting. Your Dad would practice with each bike and then decide which one he would race and Geoff, who turned out to be the best rider of the three of us, would ride the other. I left Rhodesia in 1964 and lost touch with both Geoff and your Dad but I heard that he had a serious accident while competing in the I.O.M. TT and through this site I have managed to learn a lot more about him. One great engineering brain your Dad had. I hope you eventually get to read this comment and if you so wish please get in touch with me at tilly.ken01@gmail.com

Hi Michael, I live in Canada and have been involved in the classic racing for years. Living in Canada we don’t come across any Hillman imps but I have been looking for an engine for years so I can build a replica of your dad’s Lynton to parade and display here, well now i have just found an engine! would you have any info notes or pictures that I could use.

Regards, Ray Roberts.

Paul, this is a grand summary of Lyster’s Imp moto & innovative hydraulic disc brakes – I remember much of this story from contemporaneous “Cycle World” & “Cycle” coverage, so thanks for posting it

I also remember (accurately? dunno….) that Lyster took that same head & placed it atop a standard CB450 cylinder/cases, housed in the same (or a similar) racing frame, touting it as another potentially competitive 500GP mount – I was astride my cafe Black Bomber during this same time & thus was keen on any & all CB450 developments