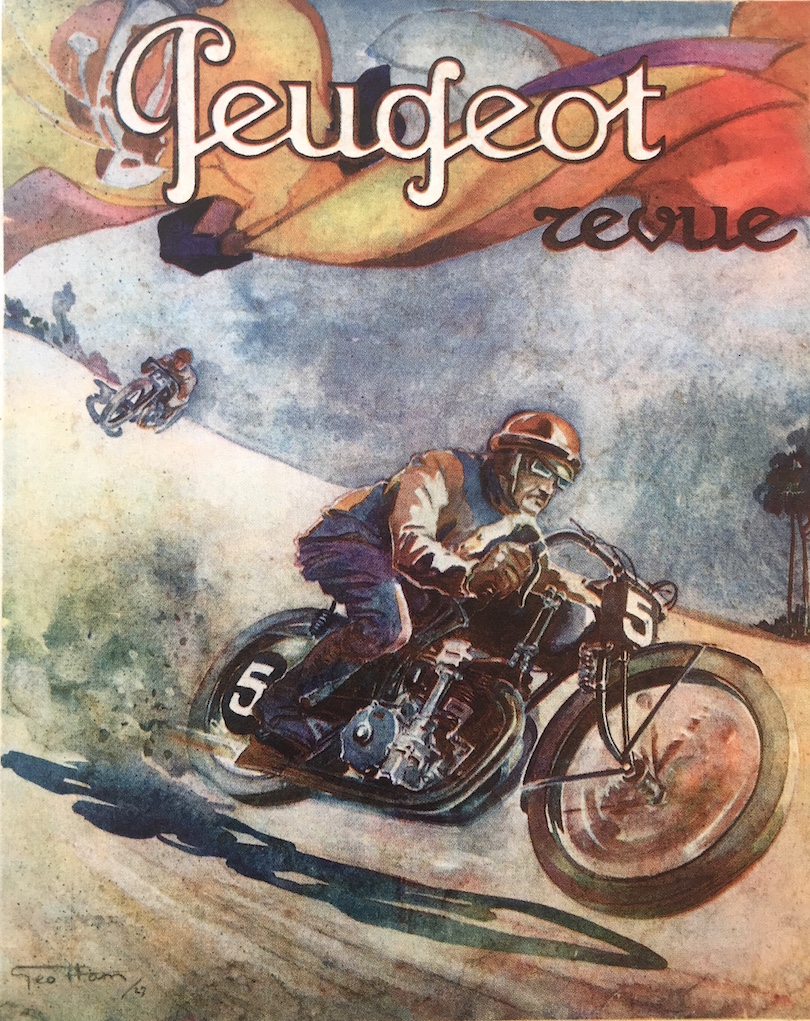

Here’s a fun fact: Peugeot is the oldest motorcycle manufacturer in the world, since 1898. Sorry Harley, sorry Indian, the French got there first…but you knew that, right? Most American factories based their early engines on a French design – the DeDion motor – whether copied or licensed (except for Pierce, who copied a Belgian design, the FN four!). But Peugeot’s heyday as the world’s preeminent force in two- and four-wheel racing was so long ago it’s nearly forgotten today.

Les Charlatans

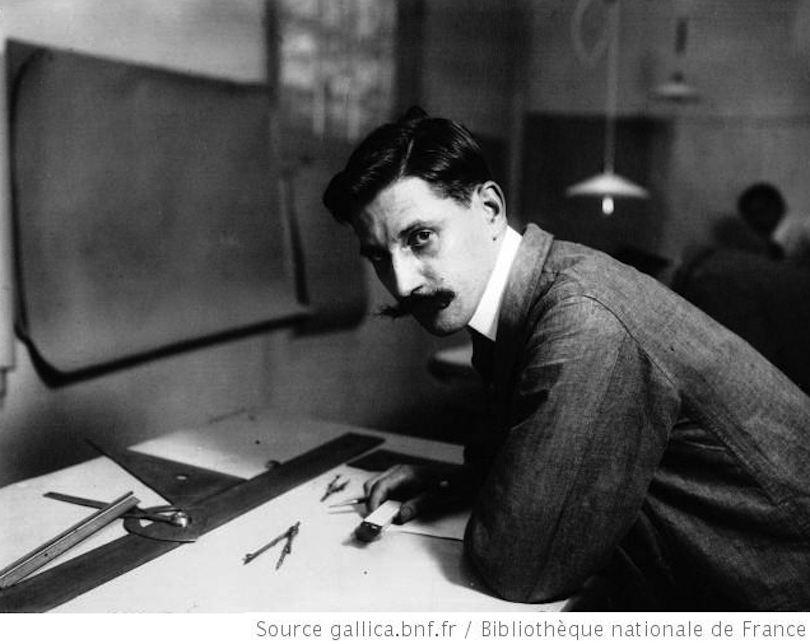

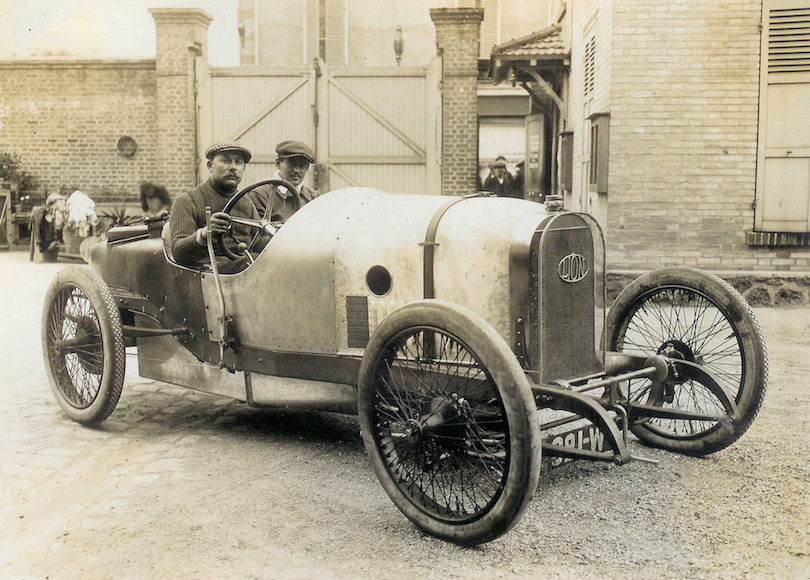

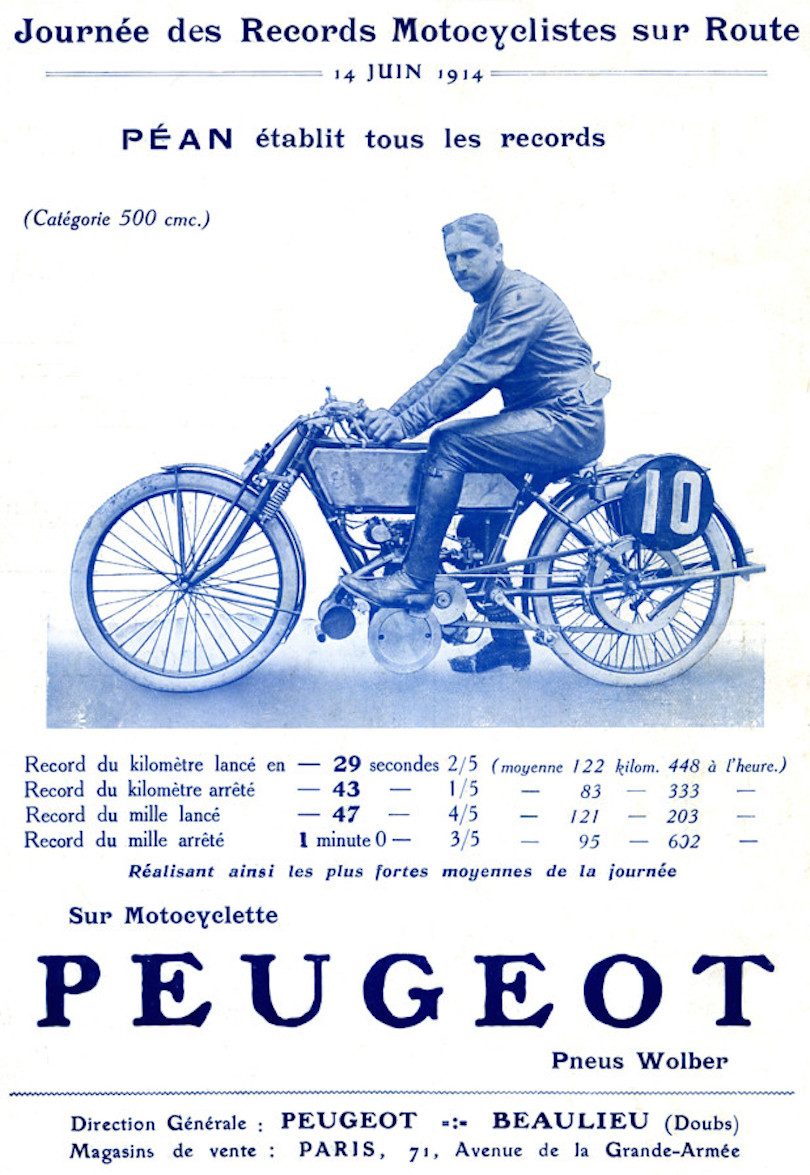

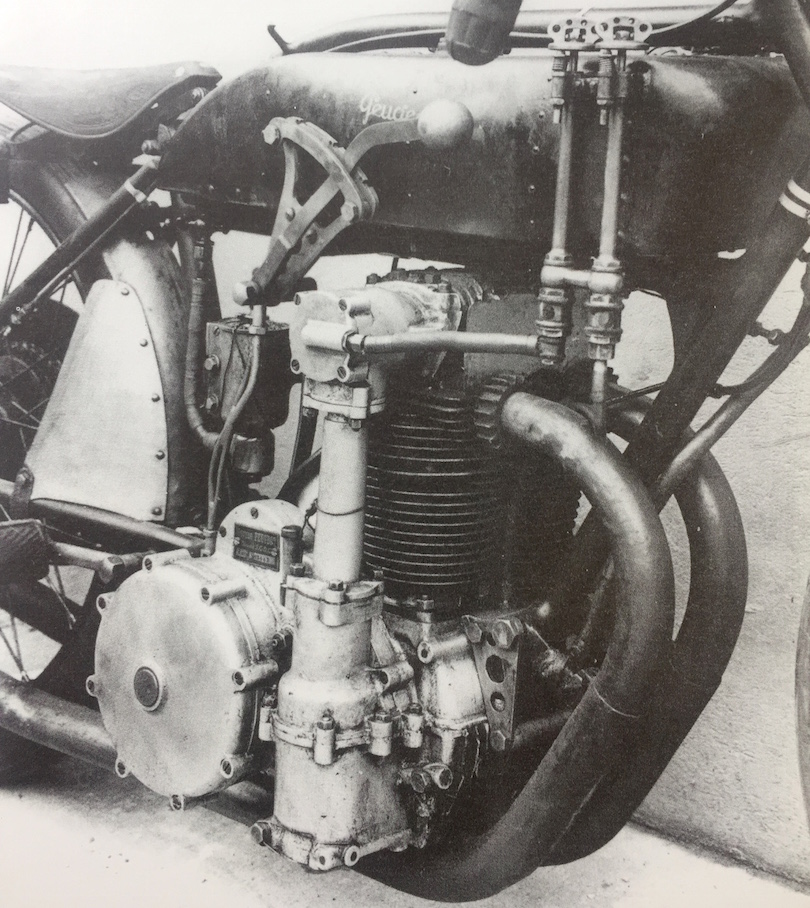

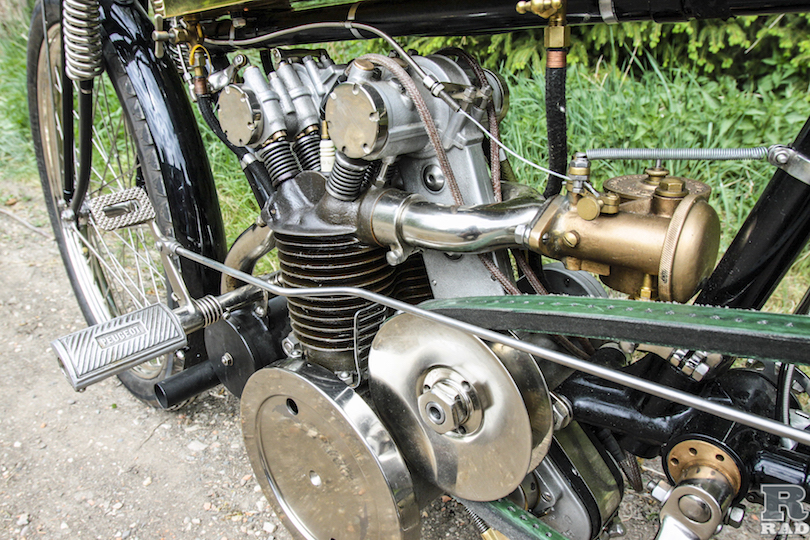

While Peugeot’s early v-twins (as used by Norton et al) were reliable and reasonably fast in the ‘Noughts, in the 1910s Peugeot débuted the most technically sophisticated engine designs in the world, first for automobile racing in the burgeoning Grand Prix series, then in a series of remarkable motorcycles. In 1911, Swiss engineer Ernst Henry was commissioned by ‘Les Charlatans’ (Peugeot racing team members Jules Goux, Georges Boillot, and Paul Zuccarelli to draw up a new four-cylinder racing engine from ideas they’d discussed. Henry wasn’t a ‘qualified engineer’ but a draughtsman, with enough experience in motor design already (for boats and cars) to have caught the attention of the Peugeot team drivers.

Post WW1

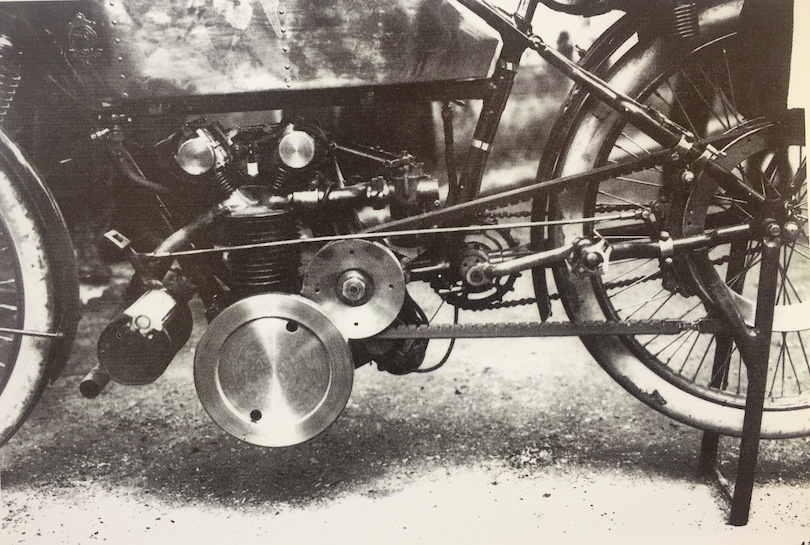

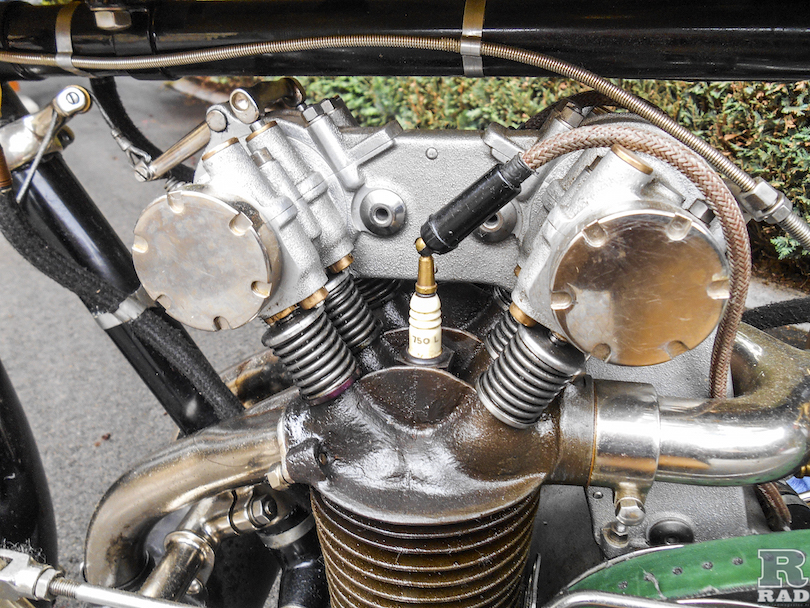

In 1919, the Peugeot OHC motorcycle project was revived by a new engineer, Marcel Gremillon, who added a clutch and 3-speed gearbox with all-chain drive. Henry’s original 500M was a nightmare for even simple maintenance, with its one-piece casting for both cylinders/heads and 8 valves, so even simple tasks like valve adjustment and decoke required a total engine strip.

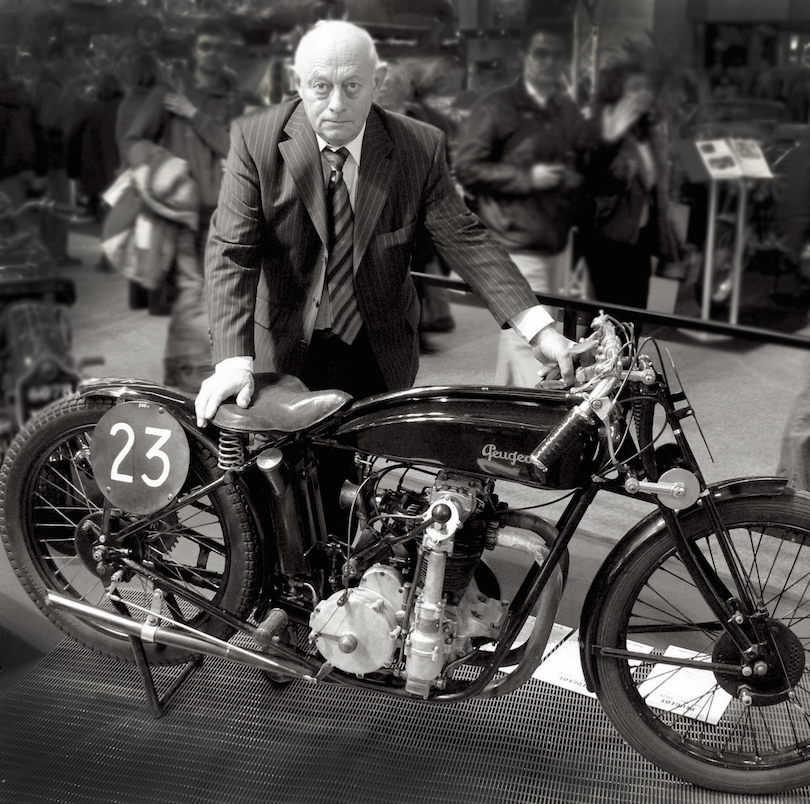

The Recreation of a 500M

– ‘Motos Peugeot, 1898-1998; 100 ans d’Histoire’, Bernard Salvat / Didier Ganneau, 1998, EBS

– The Automobile, ‘Peugeot Racing Engineers: Ernest Henry’, Sébastien Faurès Fustel de Coulanges, 2012

– RAD magazine, ‘Résurrection d’Une Peugeot 500 DOHC’, Alain Jardy / Fabrice Leschuitta (photos)

– ‘La Motocyclette En France; 1894 – 1914′, Jean Bourdache, 1989, Edifree

– Bibliothéque Nationale de France digital archives

– Yves J. Hayat/ NewYorkParis

I have a picture of my grabdfather standing next to a peugeot motorcycle and uts dated either 1911 or 1917. Would you like it?

What a fantastic machine! Labour of Love! And truly impressive!

In common with air cooled aeroengines of the same era, I rather imagine that over heating (or rather under cooling) would have limited the (long term ) output of this engine. Note lack of cooling fins on the top of the combustion chamber n around the exhaust porting. But still, best one on the block in it’s day.

But I guess if another replica were to be built with adequate cooling fins, it would be another, different bike, not a true replica.

Its easy to see this engine growing n morphing into the Miller/Offenhauser race engines.

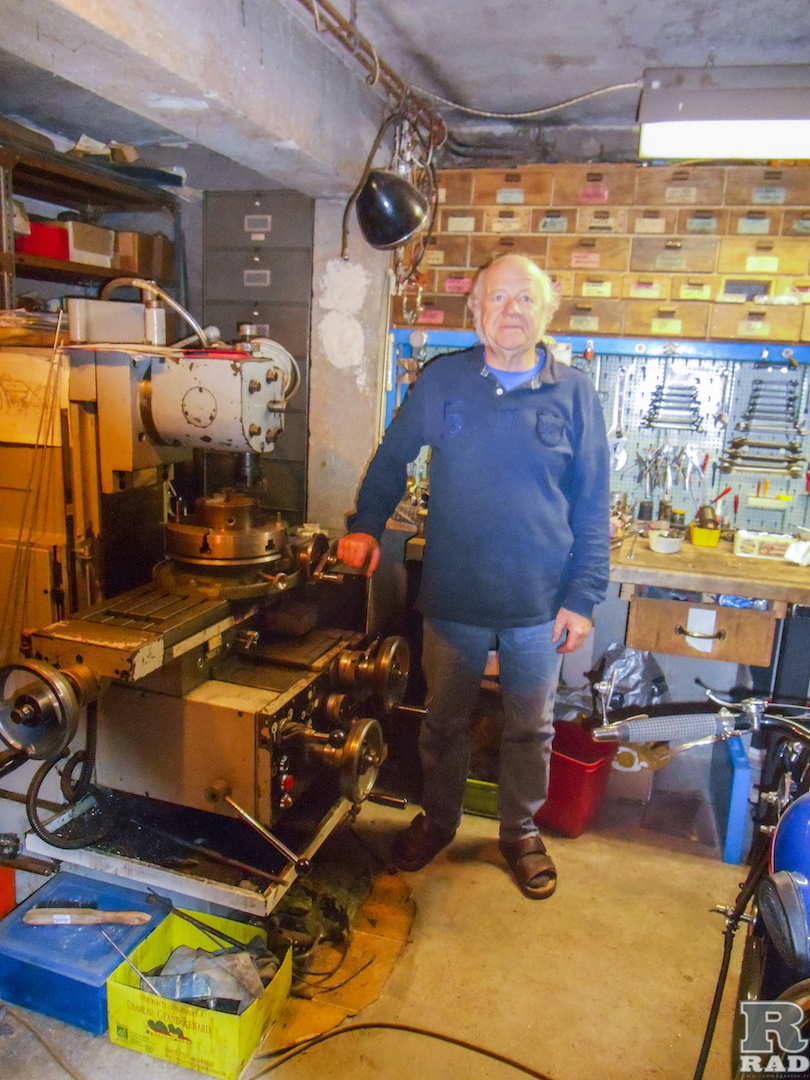

I think that the top level of the craftsmanship, the vast number of build hours (over 6 years of 8 hr days!), n the authentic source drawings make it a sure qualifier into the vintage motorcycle field.

Congratulations to Jean Boulicot n Dominique Lafay n the others, for filling in the missing link in motorcycle racing history!

Very Thank You!

Irn Ed

so you’re telling me that this man just built a whole motorcycle from scratch with plans from a hundred years ago

As one does… 😉