Dedicated Future-hunters in the motorcycle world smile ruefully at regular columns and drawings published in magazines from the 1920s through the 50s, in which visionary readers and schoolchildren sent sketches of their ‘ideal’ motorcycle (Four cylinders! Suspension!), while a few hardier and more determined souls actually set about building their dreams. It is to them we must truly tip our hat, and, without irony, give thanks, for they are the actual creators of the technologies we take for granted today. Yes, four cylinder, and yes, suspension, and disc brakes, and center-hub steering, and all-aluminum everything. Which brings us to the Mercury.

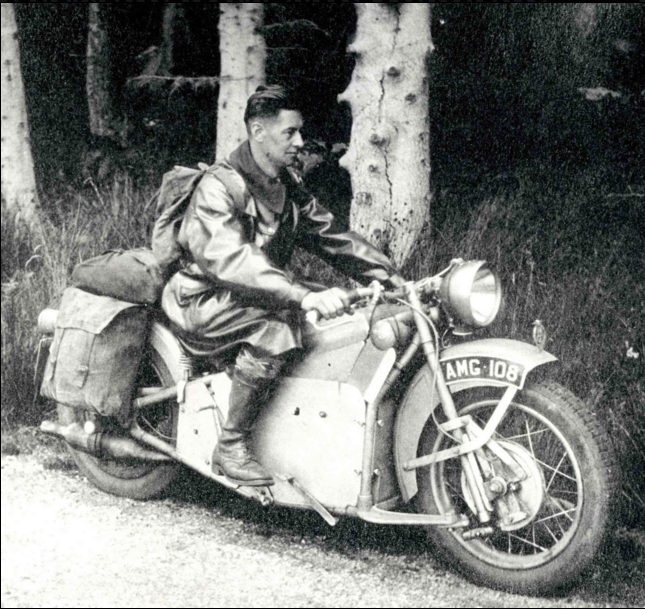

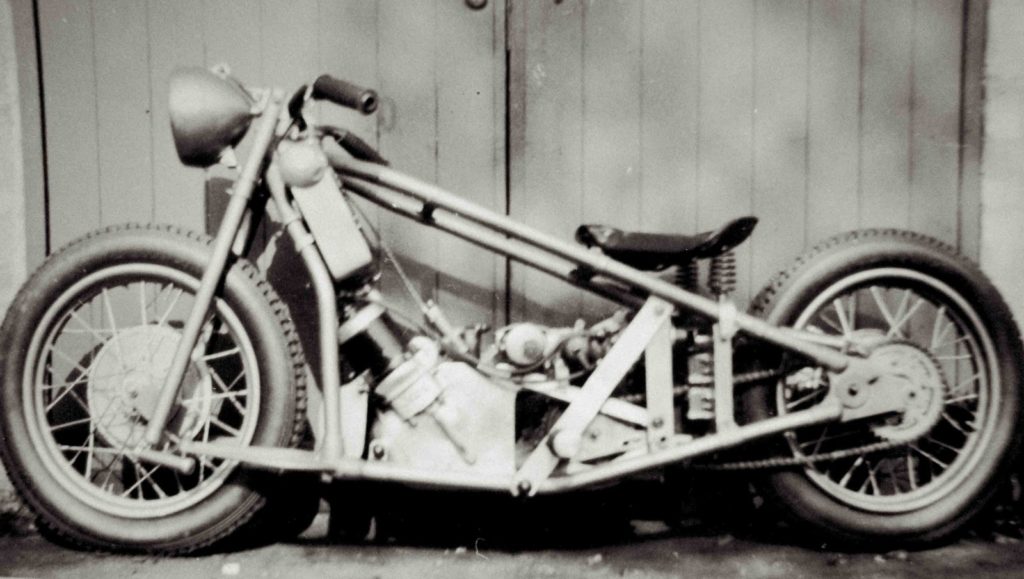

The product of four backyard visionaries, the Mercury project was especially the vision of one man, Laurie Jenks, who had toured extensively on the typical girder-forked, rigid-framed motorcycles of the late 1920s, and decided the time was ripe for a more sophisticated touring motorcycle. His first prototype, built in 1933, featured a tubular frame, with articulated rear suspension and a version of ‘duplex’ steering up front, similar to the OEC system, a cousin of hub-center steering, which we know had been around since the earliest days of motorcycling (Ner-A-Car of the 20s, and before that, the Zenith Bi-Car of the ‘Noughts), the principal advantages being lack of deflection under side loads, and greater stability over rough surfaces/hard use, and zero tendency for ‘speed wobbles’.

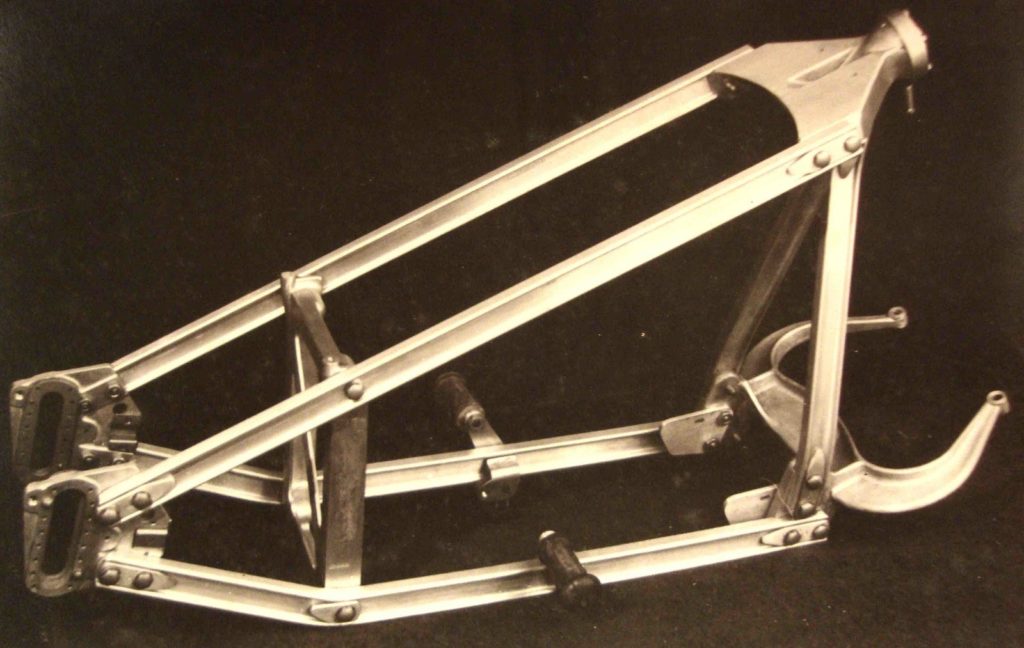

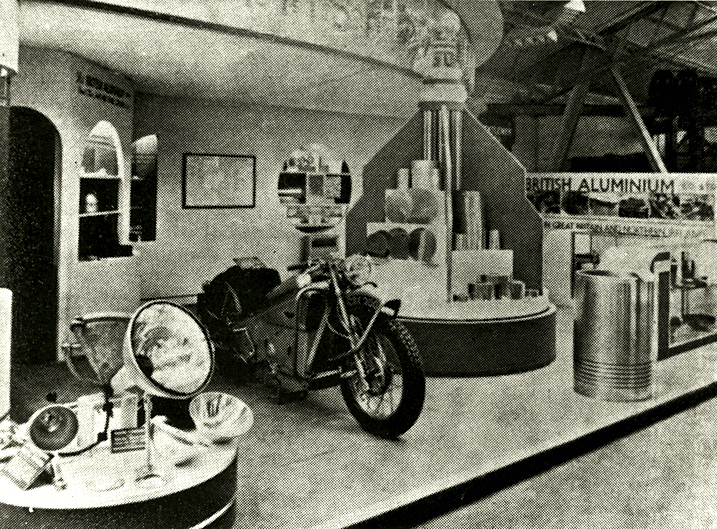

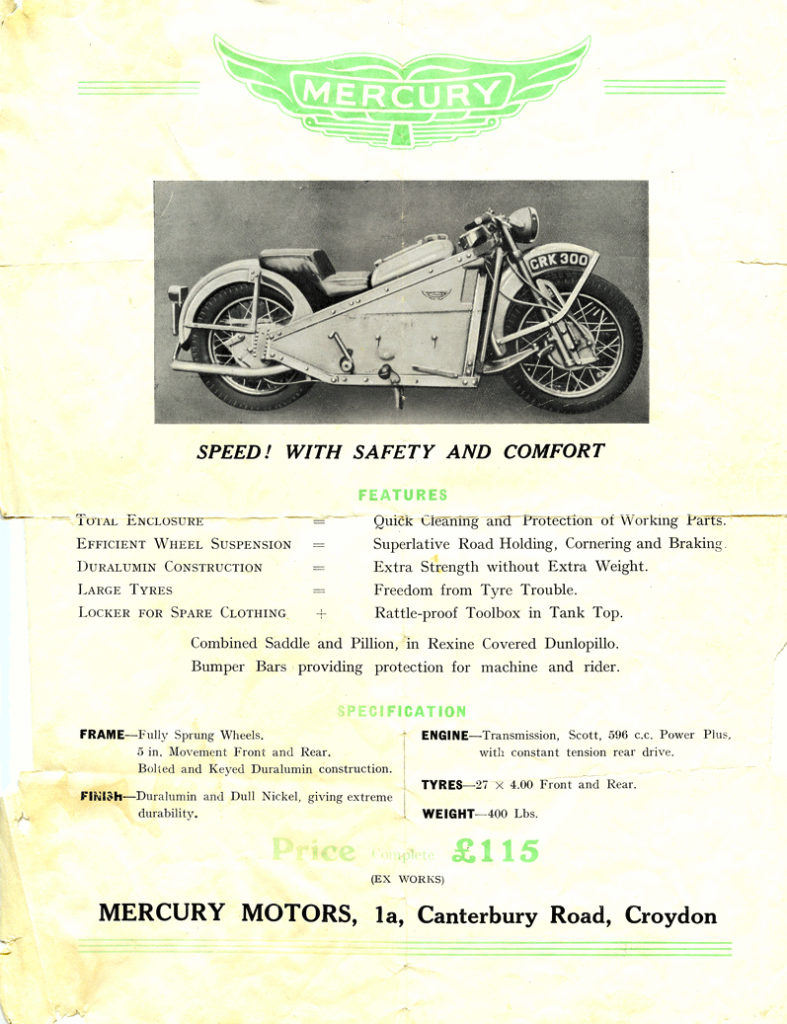

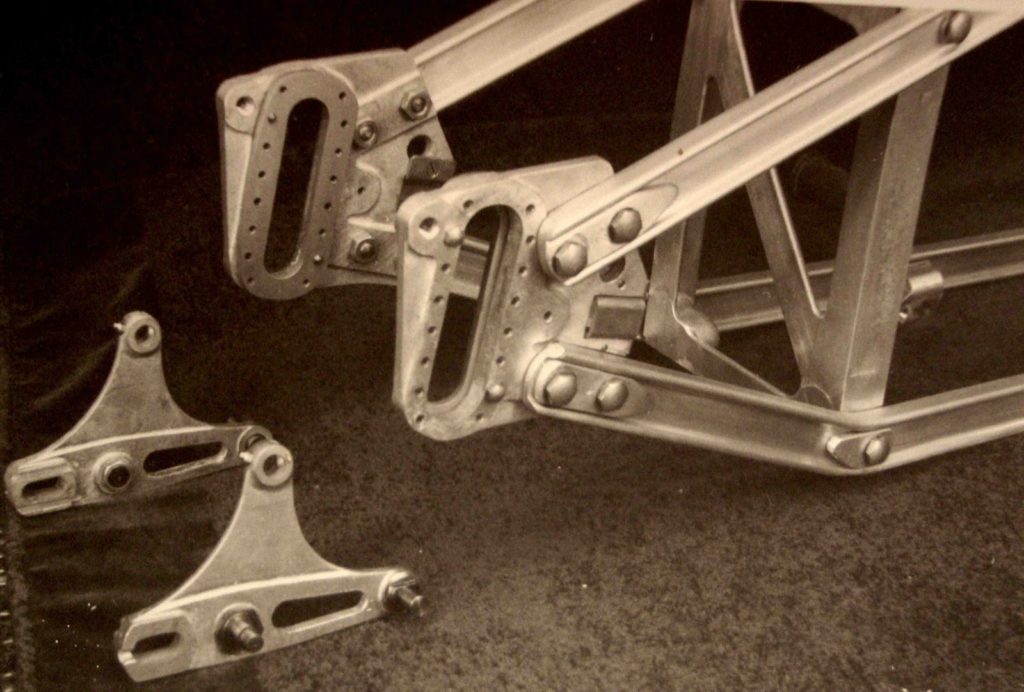

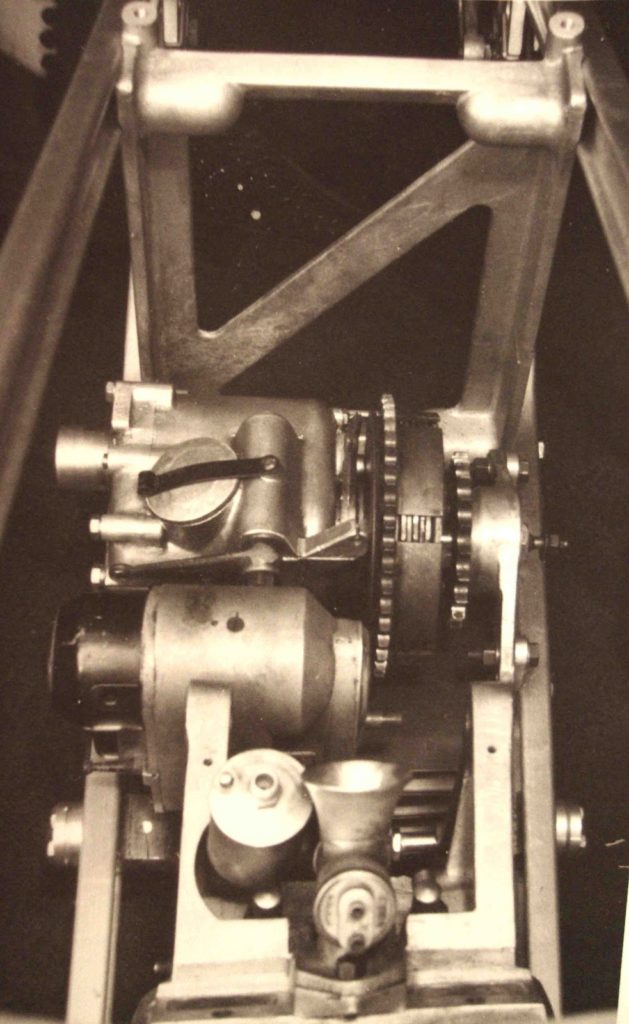

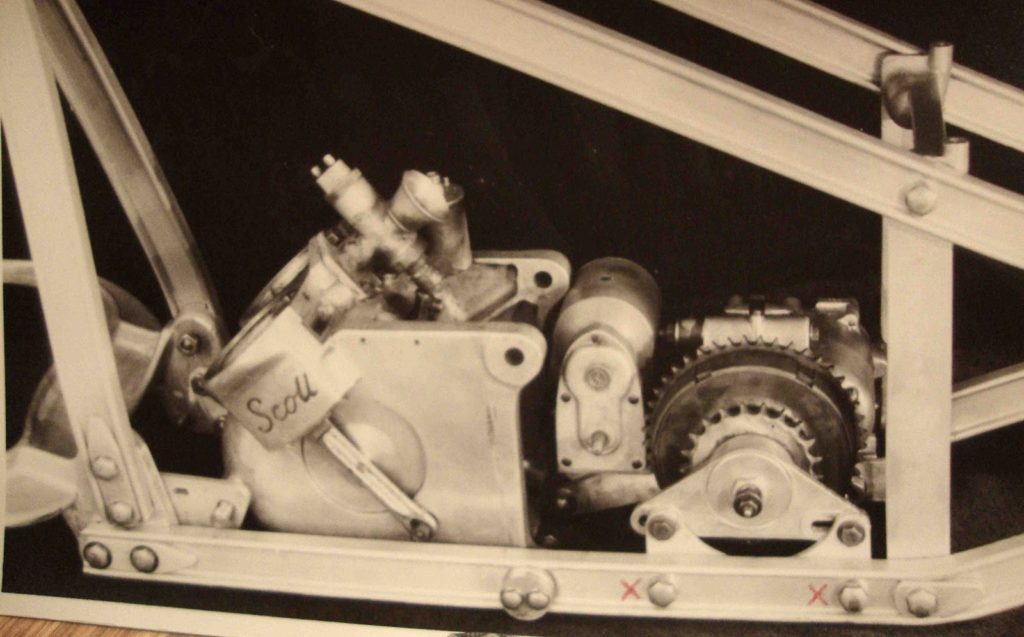

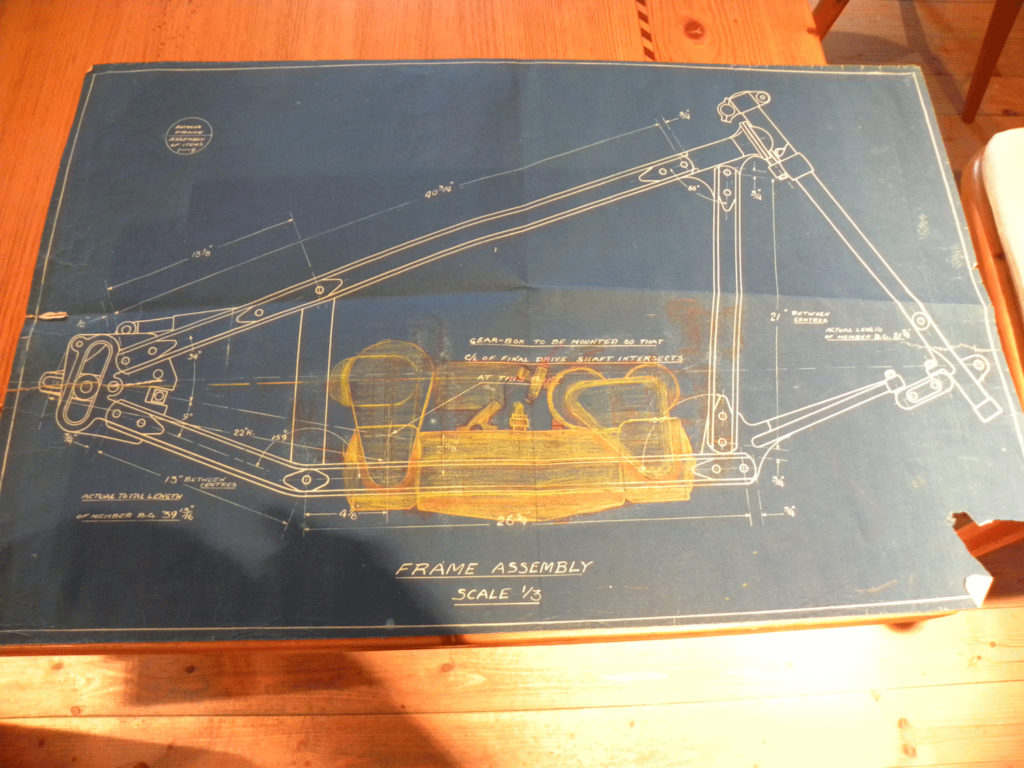

When the tube frame prototype of 1933 proved satisfactory, Jenks’ ‘Ideal’ motorcycle went a step further, with an all-riveted aluminum chassis and alloy bodywork covering his advanced steering and suspension ideas. It took another four years to begin ‘production’ of the Mercury, after ordering aluminum castings for the steering head and other lugs, plus extruded I-section aluminum for the main frame spars; enough frame parts were ordered for an initial batch of of 4 machines. The shape and material of the Mercury chassis is top-shelf 1930s practice, echoed by the most advanced GP machine of the era, with which it shares many features; the Gilera ‘Rondine’ also had an ultra-strong twin-spar chassis, and extensive use of aluminum, and water cooling…but the similarities end there, as the Rondine’s DOHC supercharged inline 4 was truly the Future, whereas the Mercury’s tuned Scott 600cc two-stroke twin-cylinder engine was merely the Present.

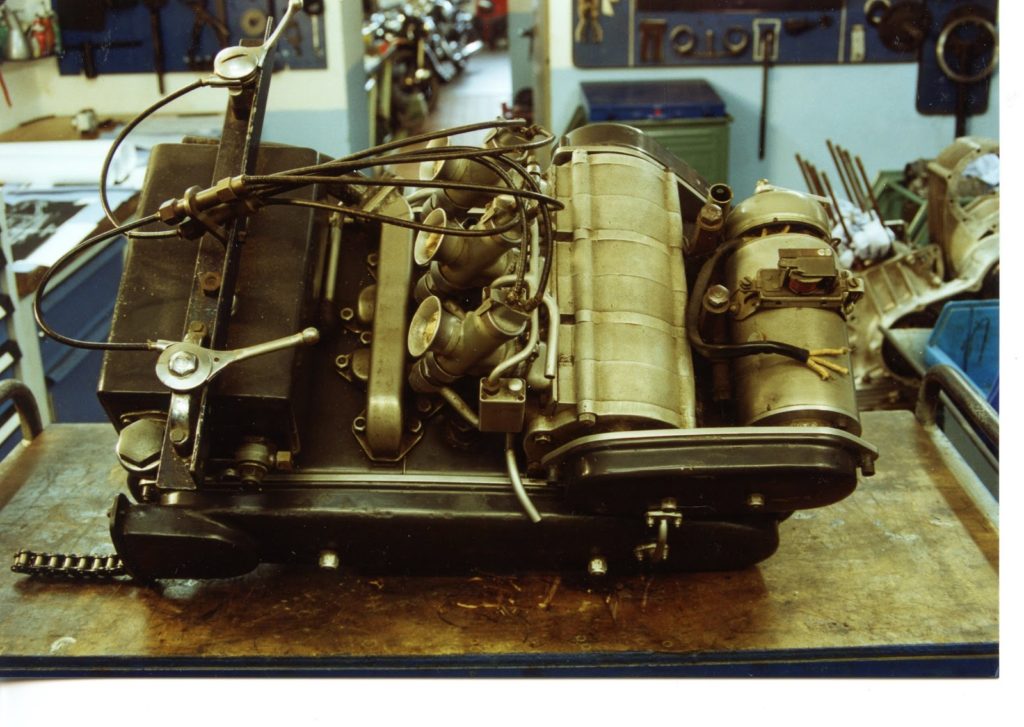

In truth, with limited funds available to buy a new engine (let alone develop a motor of their own), Jenks and his partner Mr. Swabey, who ran a garage tuning Scott engines, relied on the Past for their Mercury motors, and used reconditioned and tuned Scott engines from as far back as 1933 in their futuristic machine.

While Scott was the only ‘sporting’ and TT-winning motorcycle to never win a Brooklands ‘Gold Star’ (for a 100mph lap during a race), the Scott engine had its appeal, being very smooth, simple, reliable, and easy to maintain, while possessing devilishly quick acceleration, if not the 100mph top speed required of a truly Hot bike. When press-tested in 1937 for Motor Cycle, the completed Mercury was ridden hands-off around the incredibly bumpy Brooklands track at an average of 70mph, while 90mph was the estimated top whack. When introduced to the world in 1937 as the product of ‘Mercury Motors’, the price was listed at £115 – the same as a Brough Superior ’11-50′ model with 1100cc JAP engine (see the full Brough price list here, on the excellent B-S company archives). Those first four aluminum chassis were the only Mercuries built; we love the Future, until we must pay for it.

The Mercury was stable enough for Brooklands, and fast enough at 90mph, even if not a racer; what else was it? Meant for touring, clearly, with a lot of elegant details with the rider’s comfort in mind, like the large tool/glovebox in the tank top, which also housed an oil reservoir for a chain oiler. The instrument panel included a fuel gauge, and various pull-knobs for electrical controls. Both front and rear suspension consisted of undamped compression and rebound springs, which Jenks felt kept the wheels in more contact with tarmac over undulations. Large section tires (4″x19″ – huge for the day) gave comfortable if slow steering, and all that aluminum protected the rider from oil and mud. While the chassis and bodywork were aluminum, the deep mudguards were nickel-plated steel, giving an overall super-silver look, akin to the sleekest aircraft of the day, all rivets and shiny panels, the very picture of the Future, Buck Rogers on two wheels.

Laurie Jenks wasn’t the first, nor the last to build an ‘ideal’ motorcycle, and his Mercury was better than most in looks and real-world performance. While not to everyone’s taste, I find the Mercury visually exciting, and 1930s-futuristic like almost no other vehicle on two or four wheels – closer to advanced aircraft practice. Jenks’ fundamental ideas – a comfortable and civilized sporting motorcycle which protected the rider from the elements- were completely sound, and an accurate vision for the Future. A funny thing about the Future, though; when it actually arrives, it immediately becomes the Ordinary. Motorcycle manufacturers have been burned many times by introducing radical new ideas (full enclosure, Wankel engines, hub-center steering) to a non-buying public, but the idea of a sophisticated, smooth, fully enclosed sport-touring motorcycle finally came to fruition in the 1990s, embodied by machines like the Honda Pacific Coast, and later, the fully-enclosed Gold Wing and its cousins. All very efficient and rider-friendly, yet somehow, incorporating good ideas from design Futures seems to leave the ‘Wow’ factor in the Past…

Many thanks to Norman Gunderson of Canada for the beautiful b/w detail photos of the Mercury; Norman found reference to the Mercury in my coverage of the Concorso di Villa d’Este earlier this year, and was a personal friend of Laurie Jenks, from whom the photos originated. Also thanks to the Hockenheim Museum in Germany, for sending the rest of the photos; four Mercuries survive, plus the tube frame prototype (a chassis only at this point – 2012), and all are at Hockenheim; if you haven’t seen this collection, you owe it to yourself to make a trip.

Leslie said…

You’ve probably seen this, but if not: http://www.classicbikersclub.com/files/article_files/Mercury%20pdf.pdf

DECEMBER 17, 2012

Thanks Leslie, I didn’t know that page was online, and yes I relied on this and other articles (Classic Bike, etc) for my information.

DECEMBER 17, 2012

Whatever happened to all those drawings of slippery shaped cars with low drag coefficient that everybody draw in the 70s? How have we got to this point and ended up with oversized 4×4 and SUVs on our roads?

– Richard B.

DECEMBER 17, 2012

Mr. Jenks had wonderful engineering ideas, but the actual bike leaves a lot to be desired. Looking at those first two photographs, I can imagine what the 1930’s customers must have thought. This was the decade of the most beautiful motorbicycles of all time (arguably), full of Art Deco flourishes, chromed fishtails, two tone paints, swooping mudguards, etc. This bike looks like a lead balloon that has gone flat.

I appreciate that these were engineering prototypes, but Mr Jenks would have benefited greatly by hiring an artist to style the bike a bit.

DECEMBER 17, 2012

And 450 pounds? It needed a diet too. It was very over-engineered, or just maybe the existing tech of the day (tube steel frames, steel girder forks, air cooled single cylinder motors with iron barrels and heads) were just dialed in better. Somehow his design, even in aluminum, weighed more than a typical steel bike. For example, a iron-motor 500cc Velocette MSS of that era was 335 lbs, a full 115 lbs less than the aluminum Mercury. I’m sure that he would have revised the design if the bike had been successful at the market. But all we can review is the prototype now.

I noticed the dual seat. That is a nice touch. Did it pre-date the Loch Ness Monster, patented by Velo around 1935?

DECEMBER 17, 2012

Pete, the ‘steel frame’ specs of the Velo MSS is exactly what Jenks was hoping to improve upon; rigid at the rear, girder up front. Sprung frame bikes are always heavier than rigid; for example, the sprung-frame Velo MSS weighs 390lbs, 55lbs more than your rigid, so let’s compare apples to apples.

Also, it’s typical as you know that prototypes and new technologies initially weigh significantly more than mass-production models, because they become ‘dialed in’ when real-world feedback and technological refinements are incorporated. It seems the aluminum Jenks used was supplied by some Aluminum trade group, and was far too robust/heavy for the application. The Scott drivetrain certainly isn’t at fault, being much lighter than a 4-stroke setup. I’m curious how the tube frame compares, weight-wise…and know the man to ask!

As for looks; I like that the Mercury isn’t ‘styled’, it’s an honest machine, built by enthusiasts with a vision, without the hand of a professional stylist. It is inelegant, but really shows off the technology as perhaps a more ‘attractive’ design would not. By comparison, the BMW R7, the premier Art Deco moto-masterpiece, strays towards the world of the automobile, while the Mercury looks like no car at all, even with full cladding…more like a home-made rocket to the moon.

Excellent point about the dual seat; hadn’t considered that! It IS a pioneering example, contemporary with the ‘Loch Ness Monster’ used on the 1935 of Velocette Factory race machines.

DECEMBER 17, 2012

Good point regarding the weight. Jenks wasn’t too far off from a bike with rear springing. (I never pay attention to those later bikes and it had slipped my mind!). And of course he would have reduced weight with the future revisions of the bike. I get to do engineering design all day long, and it is loads of fun to lay out improvements, but I still can’t love the aesthetics of the bike. Maybe if he had found a more pleasing way to feature the bike’s tech… I like to see the novel engineering, but he seemed to want to keep everything behind the sheetmetal. The frame is fairly hidden, the front forks area a mess, and look at the front mudguard! But he was just a man. Still, the Neracar, the early BMW, OEC, Opel, and others were able to showcase their engineering oddities with visual aplomb that this bike lacks.

I think that you’ve already written on the covered bikes like the Vincent Prince, Velo LE, etc. Covering the mechanical stuff has been a frequent goal of bike designers, but wasn’t commercially successful until the plastic bikes of the 1980s I guess. It is a different look than the wide open bikes that were common in yesteryear.

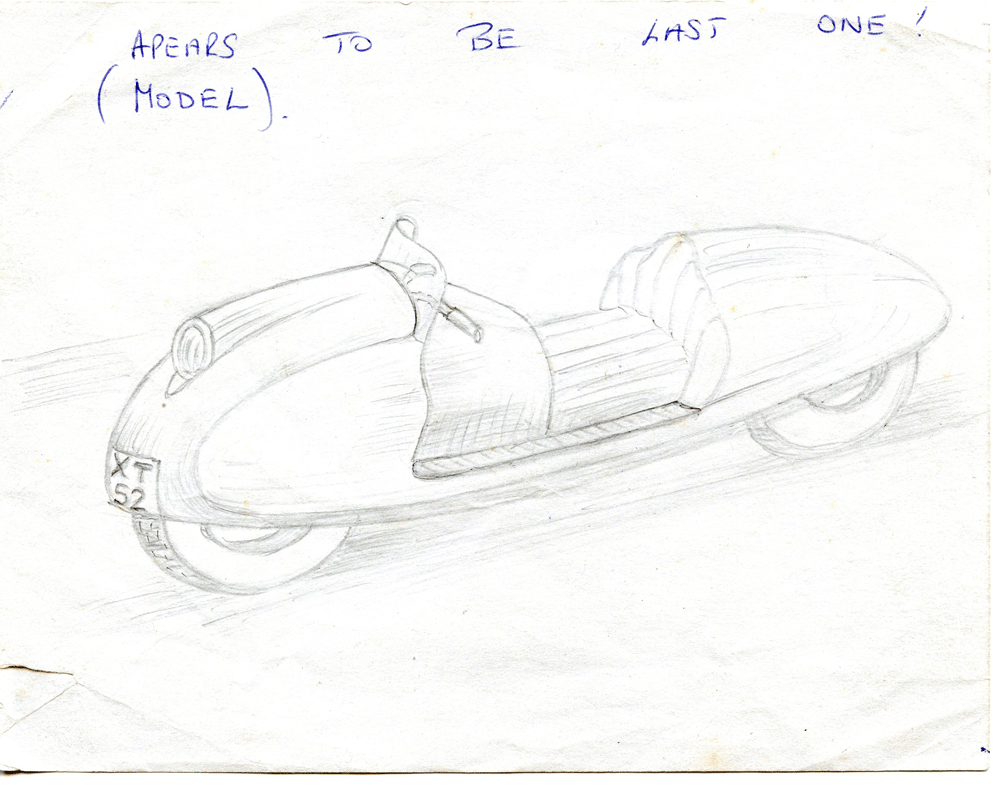

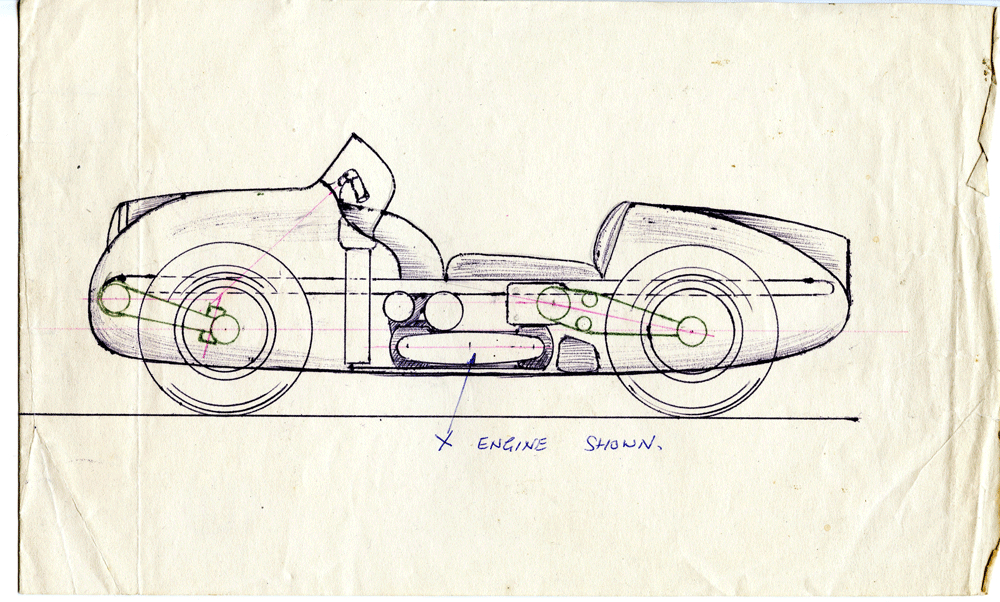

His sketches of the “two wheeled car” are completely different from the protos. Again, they do not draw attention to the expensive and innovative engineering, but the coverage seemed to be more of his goal. Did you notice how much the front end resembles Frank Westfall’s streamliner Henderson? That would have been an interesting bike.

You probably know that my attempt to do a job like Jenks did would look very much the same as his! We are both just mechanical engineers, and I don’t mean to slight the man for that. I don’t have a hand for artistic styling, but I appreciate it when I see it done well.

All in all, it is so much more interesting to see this stuff and chat about it than the typical motorbikes on the common internet sites these days! It is certainly more fun than debating Firestones and pipewrap… 🙂

ciao,

Pete

DECEMBER 17, 2012

I very much liked and agreed with your comments but one fully enclosed British bike and which rarely gets mentioned and was a success was the Ariel Leader. I was so impressed I instantly decided to purchase one was when it was first announced in the press which I remember reading about in The Green Un ( Motor Cycling. ) I ordered one from a stand at the Motor Cycle Show at Earls Court that year. I had it for about two years and used it for commuting to London every day and it was a success in keeping me looking clean and smart. It had extremely good road holding and having built in panniers and a dummy petrol tank which was large enough to put my helmet in made it ideal not only for commuting but touring on the Continent as well. Two problems with it, one it could be difficult to start as you were unable to get to the carb tickler and the awful brakes. The slightest sign of dampness in the air and they could grab quite fiercely but in the rain they became absolutely useless and many times I would be riding with both brakes on in an attempt to dry them, great fun. I eventually sold it and bought a Norton model 50 with the wide line frame and immediately fitted to it an Avon Dolphin fairing and built aluminium panniers which were a copy of the popular Craven panniers of the day..A great machine with superb roadholding and brakes and with the Avon fairing I kept almost as dry and warm as on the Leader.

Exactly! The Internet is swamped with ‘stylists’. It’s so rare nowadays to see amateur engineers pushing technology, and exploring new ideas. I’ve quietly encouraged my talented Custom-builder buddies to challenge themselves; either build their own motors, or explore new engine technologies. Steam, electric, hybrid, Wankel, two-stroke, whatever. Who knows, they might just make History…

DECEMBER 17, 2012

A book recommendation if I may ;” At the End of an Age ” by John Lukacs

Philosophical and Historical rather than mechanical but it explains this ‘ transitional ‘ age we’re in to a tee . A bit heady .. but not too much . Any reasonably educated person can digest it .

DECEMBER 18, 2012

Am I mistaken, or is that the first “telelever” front suspension? Also, could the lack of styling be atributed to the probability of plans for a “scooter” like body coverage shown in the latter images. Looks like the scooter might be the bike of the future 😉

DECEMBER 19, 2012

There’s PLENTY of FUTURE work and interest today! Look at the Lit Motors C-1, the electric bikes at the TT, solar cells at only 1/4 the thickness about to go in poduction and lower costs, LED lighting, windmills popping up like flowers where appropriate, lots of great stuff coming so we can have our tech and environment, too! 🙂 I’m almost 60 years young, woprking in efficient future lighting and excited!

DECEMBER 19, 2012

I’m getting an impression of the OEC in the front end or Ascot pullman of the 1930s in the overall styling – I’ll have to look out some photos, but i has a familiar look about it!

DECEMBER 29, 2012

I am impressed by your excellent point about the dual seat, it had not crossed my mind.I love the way you tackle motorcycle issues in details.

JANUARY 04, 2013

My farther and I owned AMG108 in the late 70s . We inherited it with the special engine from Laurie . As a kid I used to know him as the nutty professor . Where he lived in Appin he was planning to turn the water fall in his garden in to a power plant to run his house .the house was only heated with one 50s electric fire with a big rheostat connected to it so it could be turned down do far that his cat could not even get warm , great memory’s 🙂 A . Pittam

JANUARY 16, 2013

A long time ago I was driving past your shop when I noticed a group of people and a photographer examining a very strange looking bike that I thought it looked a bit like modified Velocette LE and made no effort to stop. It was only later that something I read or heard made to realise that it was something very out of the ordinary and now wished I had stopped to see this machine, On another occasion I was in your shop and you showed me some wonderful drawings which were all of someones idea of a machine for the future. I wish now I had taken more interest in them. Looking at vintage motor cycle books one realises that in the thirties Britain produced some very advance machines but unfortunately production ceased with the outbreak of the war and when production commenced again is seems that our manufacturers concentrated on their most popular and best selling models, such a shame.

I believe at least one Mercury had rotary disc inlet valves, with a carburettor on each (modified) crankcase door. This info was in an article in 1960s Motorcycle Sport by the late Roger Maughfling (R.T.M.) who owned the bike for a while.

MARCH 06, 2014

Just seen a picture of the beautifully restored AMG 108 on your blog of a big auction, and it has prominent scoops level with the crankshaft, so it seems that’s the one! Many thanks for these entertaining and thought-provoking blogs. Tony

MARCH 07, 2014

Hi guys, is there any video about of the Mercury? Also, any ideas who owned the machine in the 1990s?

APRIL 11, 2016

Great job on the new website!

a very interesting subject I taught mechanics and it goes to show there is very little new in our “modern” inventions.

I enjoyed the article about the Mercury. I was struck by the full-bodied drawing of Mercury and how closely it appeared to resemble a one-off, full bodied, Deco-inspired motorcycle designed and built by O. Ray Courtney in the mid-30’s. Courtney used a Model KJ Henderson for the basis of the motorcycle. You may know of the bike, but if not, there’s a good article about it on the Coachbuilt.com site. http://www.coachbuilt.com/des/c/courtney/courtney.htm should get you there. The bike is owned by collector Frank Westfall of Syracuse, NY, who acquired two of Courtney’s creations. The Art Deco Henderson-based bike is currently on loan to and on display at the Northeast Classic Car Museum in Norwich, NY. The museum has the second Courtney bike, the “Enterprise,” but it is currently in storage.