While Burt Munro’s ‘world’s fastest Indian’ is the most famous record-breaker to use Springfield iron as its base, it certainly wasn’t the only Indian used in land speed record attempts. Let’s not forget that the first-ever certified absolute motorcycle world speed record was set by Gene Walker on his 994cc Indian, at Daytona Beach in 1920. While he ‘only’ recorded a 2-way average of 104.21mph (167.56kph), this was faster than anyone else had done under the watchful eyes of a neutral (ish) sanctioning body – the FIM – who still oversee international records. Glenn Curtiss was timed one-way back in 1906 at over 136mph on the same stretch of beach, but it was an unsanctioned record, and not repeated in a return run.

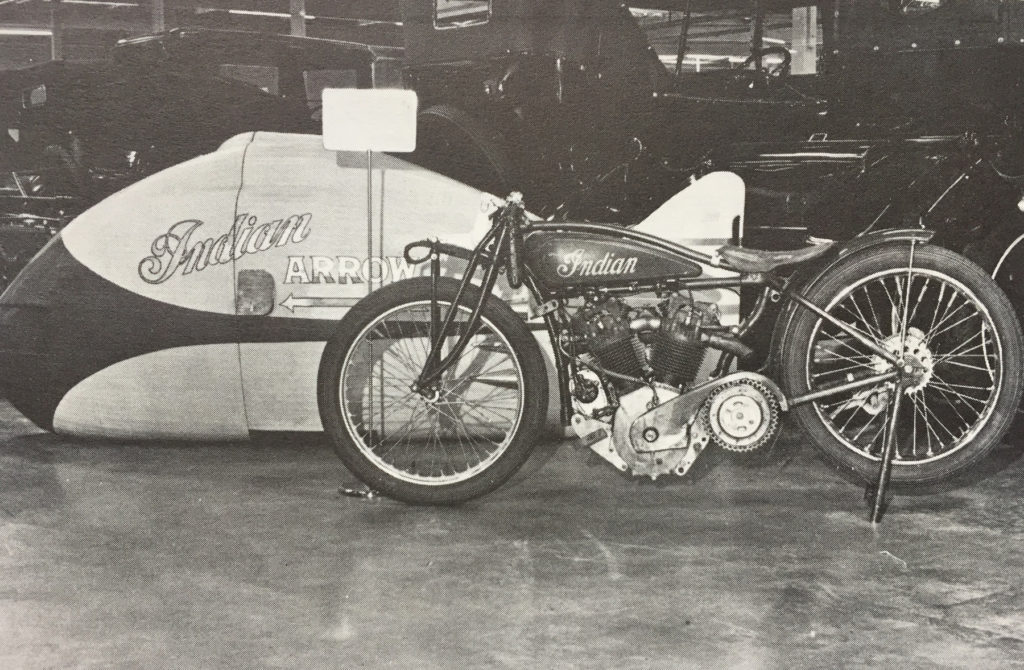

In 1936, Oakland Indian dealer Hap Alzina supervised the construction of a streamliner shell for another attempt to take the absolute honors for Indian. Alzina had secured a rare factory 8-valve 1000cc racing engine from 1924, one of a dozen built by Charles Franklin. These engines were capable of 120+mph speeds, running on alcohol, and it is supposed Alzina’s engine was used to set the American speed record in 1926, with Johnny Seymour blistering along at 132mph. It seemed to Alzina that a bit of streamlining, as clad other world record machines (BMW, DKW, and Brough Superior specifically by 1936), could send the Indian name ot the top, especially as Joe Petrali had recently taken the American record on his modified ‘Knucklehead’ at 136.183mph – on a streamlined machine which had its body removed after it was found to be unstable. The last-generation 8-Valve engine was at least as fast as any unsupercharged motor then in existence, so in theory they had a chance.

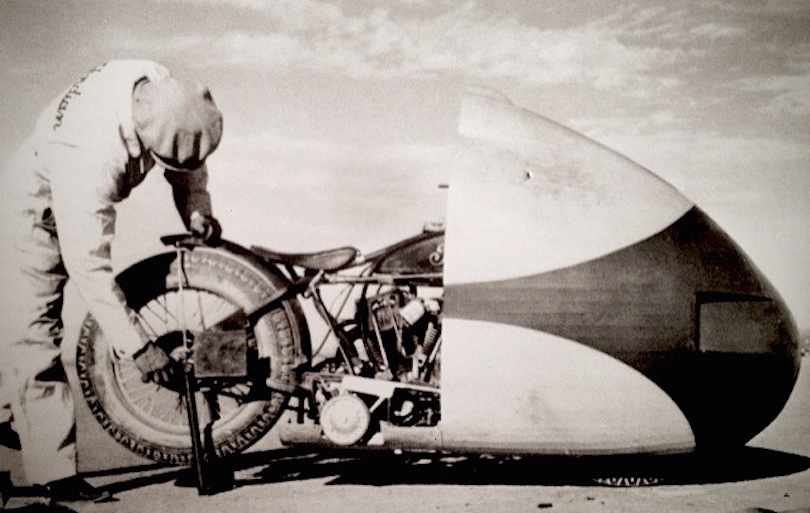

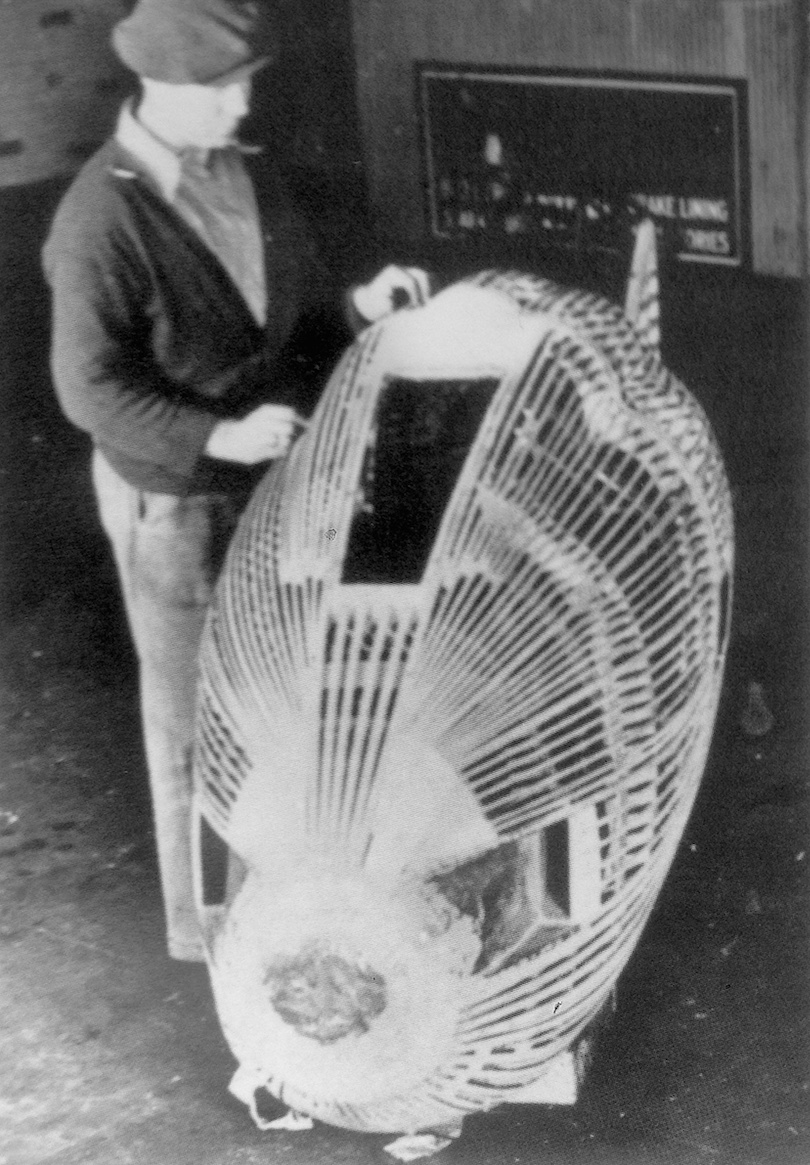

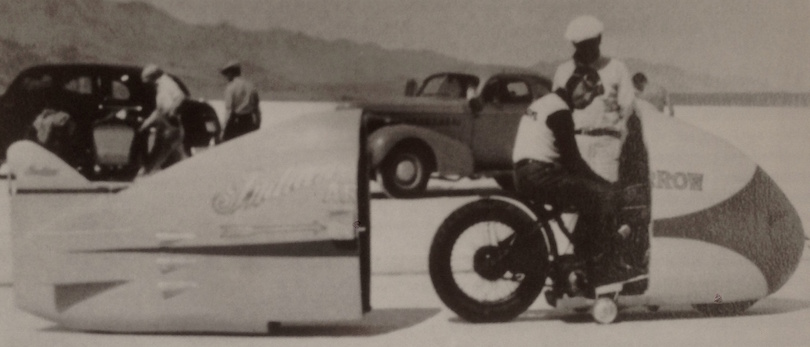

Knowing streamlining was tricky business, Alzina hired an aircraft engineer (William ‘Bill’ Myers) to draw up and construct the very plane-ish body, which was constructed of balsa wood strips over plywood bulkheads, covered in canvas, and sealed with ‘dope’, just like a biplane. A chassis was constructed around the engine from a variety of Indian racing parts, with 1920 forks, a recent frame, and an older rear section, all of which was very light, as per their usual racing practice. The tank was from a ‘101’ Scout, and the naked machine looked surprisingly coherent for a cobbled-up special. To economize on the timekeeping expenses, three machines were taken to the Bonneville Salt Flats for record-breaking: a Sport Scout, a Chief which had been stripped down to Class C rules, and Alzina’s ‘Arrow’. All 3 machines were in fact heavily ‘breathed on’ for the records, and the Scout became the fastest 750cc in the USA at 115.226mph, while the Chief managed an impressive 120.747mph, both Class C American records.

Fred Ludlow piloted the ‘Arrow’ in tests, and the ultra-light weight and racing chassis geometry of the bike did the attempt no favors. That the streamline shell was untested, and also very light, was also bad news, and while the bike was very fast indeed, it proved unstable above 145mph, weaving and tank-slapping until it was blown off course, and realizing the shell was unsuitable, the attempt was scrapped. It’s easy in hindsight to diagnose the flaws of their machine, but Alzina was a private dealer with a little factory help, and not a well-funded, factory-backed racing effort. It was clear the project needed a lot more work, but he’d spent a bundle on the machine already, and ultimately decided to shelve the project and concentrate on Class C racing, hillclimbs, and selling motorcycles. The ‘Arrow’ languished in Hap Alzina’s back room for decades, and it was eventually purchased by the Harrah’s collection in the 1970s. It certainly exists today, and photographs show a compelling motorcycle, almost a ‘resto-mod’ with those early loop-spring forks, and one which every Indian fan wishes they owned!

Related Posts

September 17, 2017

The Vintagent Selects: The American Wall Of Death

Director Roberto Serrini takes us…