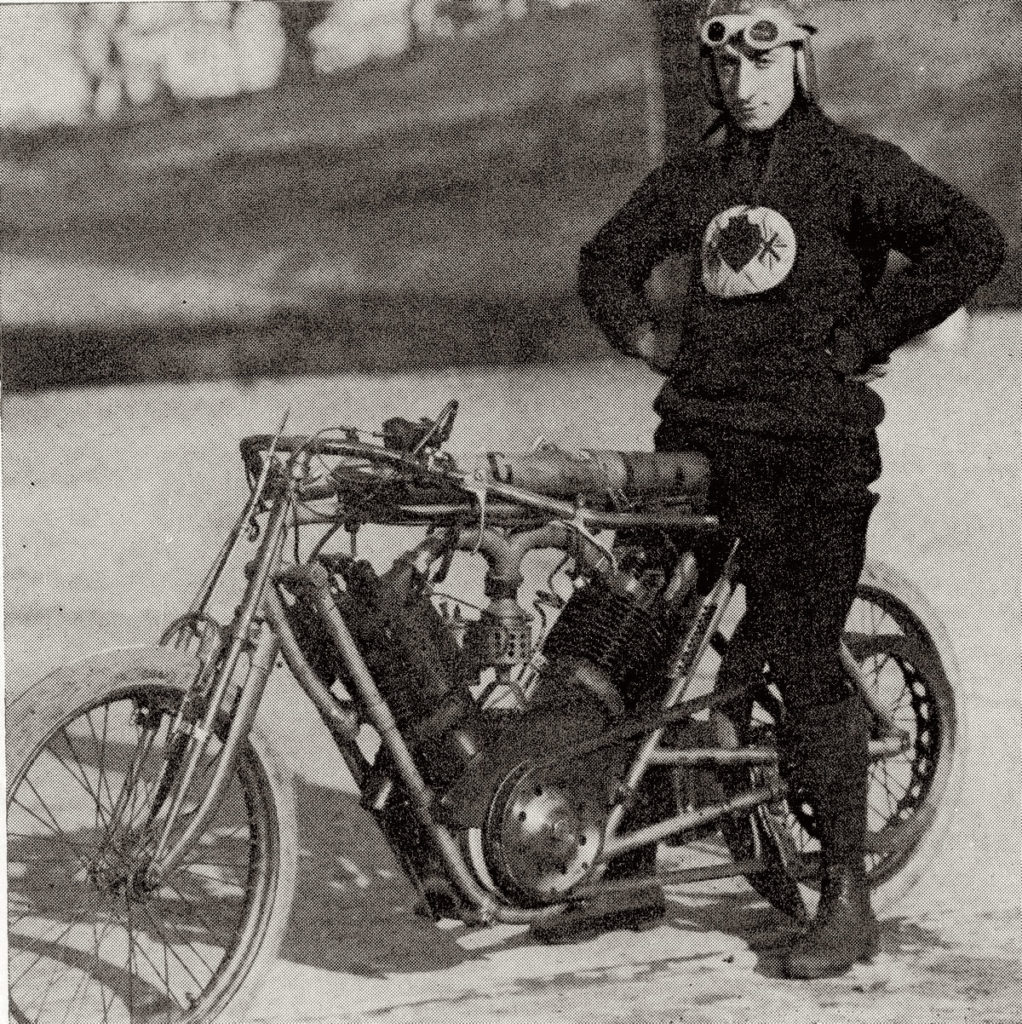

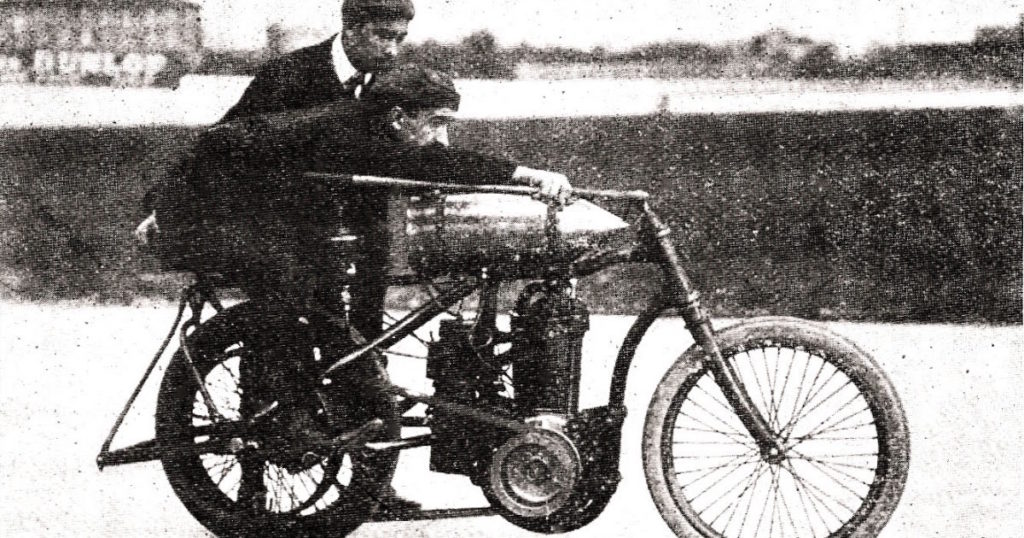

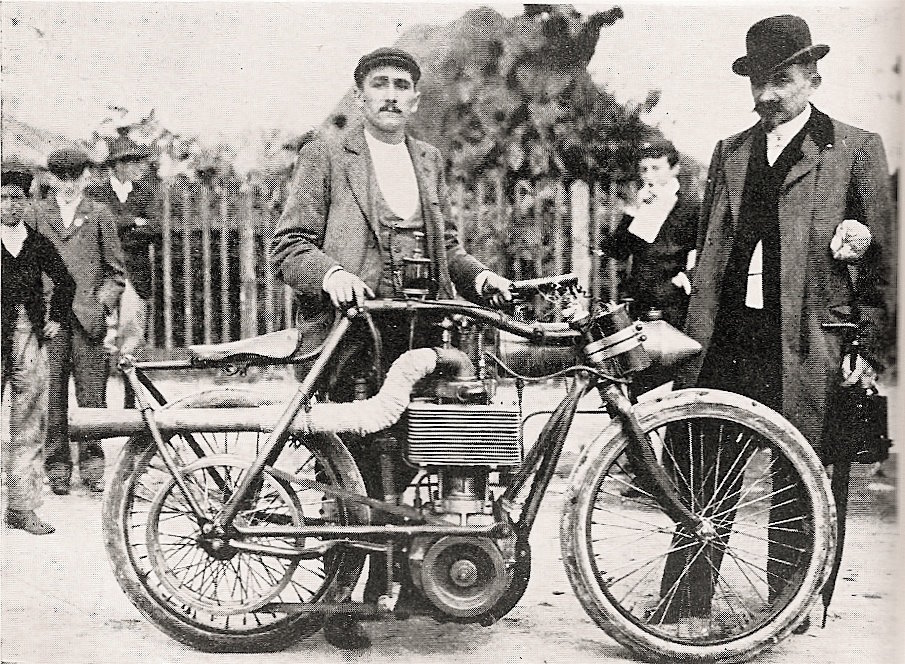

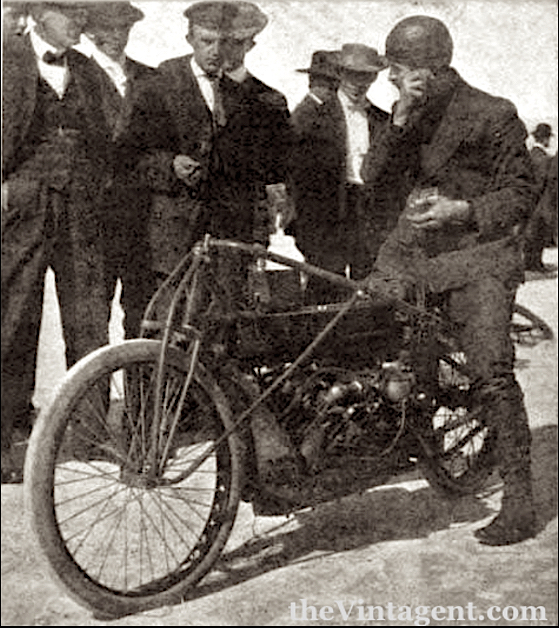

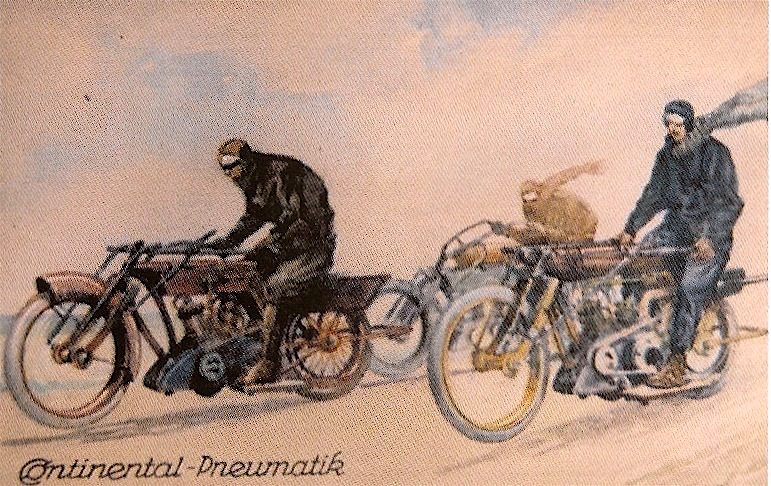

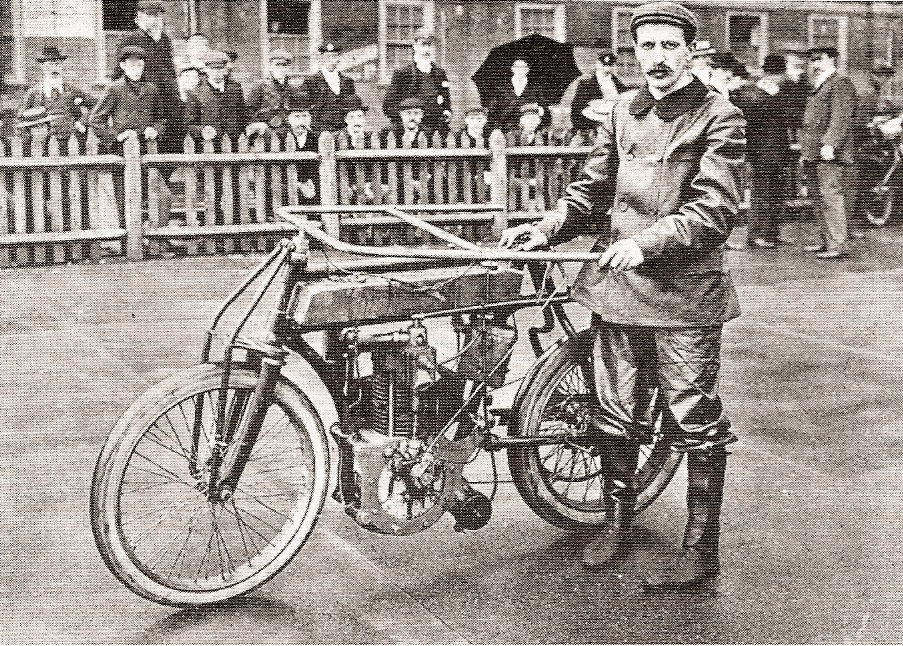

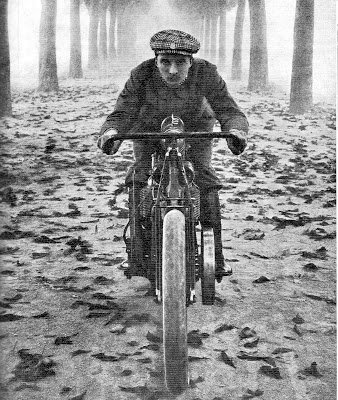

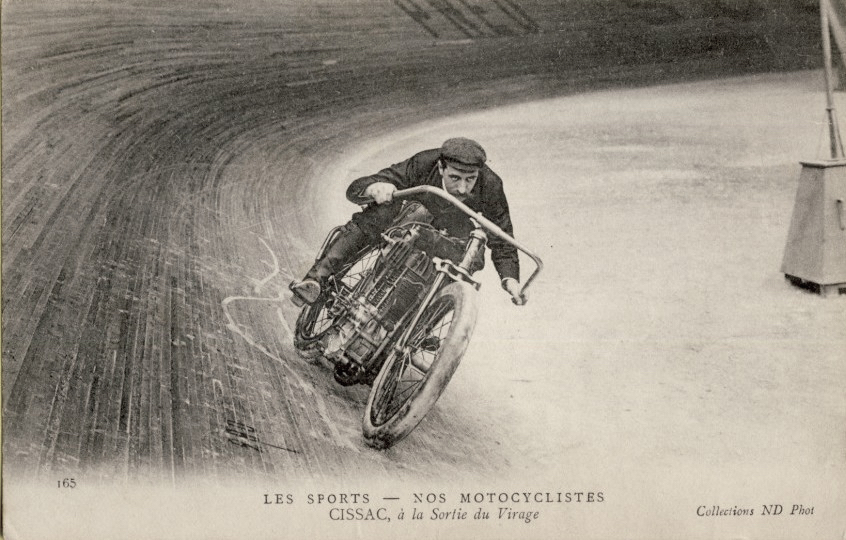

Racing rules in France and Austria (the only European countries which hosted races at that time) gave no restrictions on engine size; one cure for a weak little engine is to incorporate a much bigger (albeit equally inefficient) motor into a motorcycle. During a beautiful period in those pre-1906 days, a free-for-all developed with designers throwing the most unlikely engines between two wheels. Cylinder capacities of over 1 liter EACH were not unheard of – these were steam engine dimensions, which of course, was the common currency of the day, as trains and boats were the first truly ‘motorized’ vehicles, using steam for motive power since the heady days of James Watt and Robert Fulton.

H.O. Duncan decried them as ‘Monstrosities’, setting a poor example for the public, and arguments such as this have altered the course of motorcycle evolution in the past 100 years in significant ways. When, in the course of racing development, designers have reached for extreme measures in the quest for advantage (ie, enhancements which bore no relationship with ‘utility’), the forces of Rationality and Production-Based competition have raised the alarm and banned them. Thus, initially, engine capacity was restricted in racing to standardized formulas. In some areas, ‘Works’ machines were restricted – racing had to be conducted with ‘same as you can buy’ motorcycles. Then, as supercharging came to the fore, it was banned as well. When the number of cylinders grew to six and more in GP racing, restrictions on engine complexity were enacted. When the number of gears on lightweight racers reached 12 or more, gearboxes were limited to 6 ratios. Most recently, when the world no longer drove two-strokes, GP racing moved to four-stroke engines.

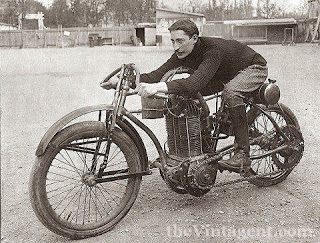

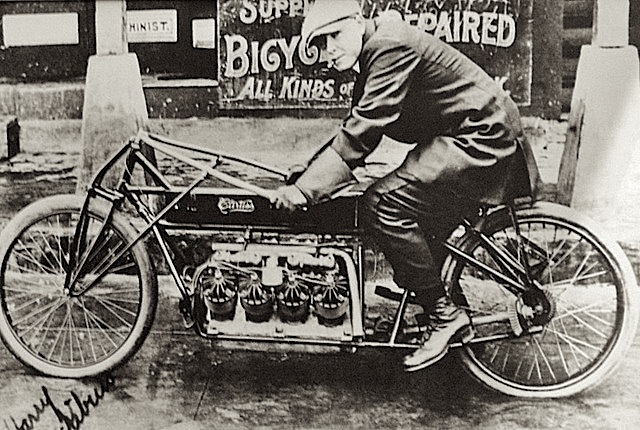

Of course, it wasn’t just the French who built Monsters; the American Glenn H. Curtiss installed an experimental 40hp (6,000cc) V-8 aircraft engine of his own make, into what may have been the earliest duplex-loop frame. In 1907, he took his shaft-drive machine to Ormond Beach in Florida, and clocked 136.8mph one-way, making him the fastest man in any vehicle at the time. The shaft broke on the return run, and Curtiss had a heck of a time wrestling the beast to a stop without crashing, but such was his luck (he never crashed his pioneer airplanes either!), he finished the course, and was satisfied. His record remained unbeaten for 23 years, and the machine now sits in the Smithsonian Institution.

Related Posts

June 13, 2017

Hi there, fellow motorcycle obsessive; while reading your blog mention of cycle pacers [in the Board Track Racing on Film post] I thought you might like the following, published in The Motor Cycle 105 years ago…I had the huge good fortune to write for The Motor Cycle in its final years, and developed a habit of photocopying articles that tickled my fancy. I’m now semi-retired and am collating them into what might become a book, or blog. I look forward to seeing the pics on your fine blog in due course, and would be happy to send you some more snippets. Like you, I was a regular visitor to Verralls many moons ago at the Tooting site. Happy days.

Hi Paul,

Speaking of monstrosities, one of my all time favorites is the Wolseley Gyro Car. How could it turn? At least you could take your mates along.

C-ya, Jer

Anonymous said…

I have absolutely adored browsing the Vintagent for a good while now …… and every now and then, I hope with your blessing, I pop a pic onto my hard drive.

The one I attached was on my screen-saver the other day when a firned noticed it and wanted to know more. Sadly, at the time I wasn’t in the habit of retaining the link to the originating blog.

If I were to let you have an insight into the wonderful esoteric world of the Hurley-Pugh, which may keep you amused for a few moments, would you please let me know if you recognise the photo as one of yours and remind me of the context?

http://www.hurley-pugh.co.uk/hpechome.html

Thanks awfully 🙂

John C Brown

Hull, UK.

In a recent conversation with a knowledgeable British friend, the subject of the Curtis 136mph Ormand Beach record came up. He thought it was pure fiction. He asked who measured the course and how, and how was it timed and by who. I had to admit that I always took the claim on face value. What proof exists as to the accuracy of the 136 mph?

Hi Dave,

a Scientific American article from Feb 1906 (Vol 96, #6) said, “In an unofficial mile test, timed by stop watches from the start by several persons who watched through field glasses a flag waved at the finish, Mr. Curtiss is said to have covered this distance in 26 2-5 seconds, which would be at the rate of 136.3 miles an hour – a faster speed than has ever been made before by a man on any type of vehicle. Unfortunately, before this new mile record could be corroborated by an official test, the universal joint broke while the machine was going 90 miles an hour…”

Plenty of folks say 2000rpm just isn’t possible with an automatic inlet valve motor, even a V-8. The gearing was 1:1, so the motor would have to spin ~2000rpm to reach 136mph. Curtiss built the best engines in the world at the time, with all ball bearings, which is why they were used in planes. I personally think the speed was possible. The engine clearly had far more power than the chassis could handle, as the final drive broke and the frame was twisted beyond easy repair by a single full-speed run.

But, as you note, this was not an ‘official’ speed record, and while dozens of observers were there for the speed trials, for whatever reason this was not considered ‘official’ at the event.

About Curtiss record:

in Europa, every body ask some simple questions as how beaded edges tires can support a speed like that…About French monstrosities fashion, scrutinizers complained that nobody could start the engines by themselves!

In those time the categories was made by weight and it’s why there were some very big engines..in reinforced bicycle frames.

At a period for the cars, the categories was made only by cylinder diameter…and some Peugeot engines had so much race than they was more high than the racers head! It’s a French national sport to try to turn around stupid laws.

Hey: could I purchase that Glen Curtiss picture, steve barnes ,,daytona. ,captneon1@att.com