Originally published in Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Arts, May 1, 1869

Only the other day, I confided to an old friend that I still possessed a sneaking regard for wheels, and though he rewarded my confidence with a pitiful sneer, I know that this wretched old hypocrite himself keeps a wonderful brass top that will spin for an hour, under a glass case on his study-table, and in secret delights to watch it in motion.

A clever marine engineer, who loves wheels too, once told me with great gravity that the human mind has never yet discovered anything so wonderful as the principle of the common wheelbarrow, ‘an invention,’ he said, ‘to which that of the steam-engine itself is nothing. The wheelbarrow,’ he went on, ‘is the only example I am acquainted with in which the very weight of a load is fairly utilised as a locomotive power.’ There was a copy of Punch on my table. Our conversation had turned to the subject of wheelbarrows from looking at Mr Keene’s vignette, in which, some three years ago, Mr Punch was depicted as Blondin, but performing the impossible feat of wheeling himself in a wheelbarrow along a tight-rope in the Crystal Palace transept.

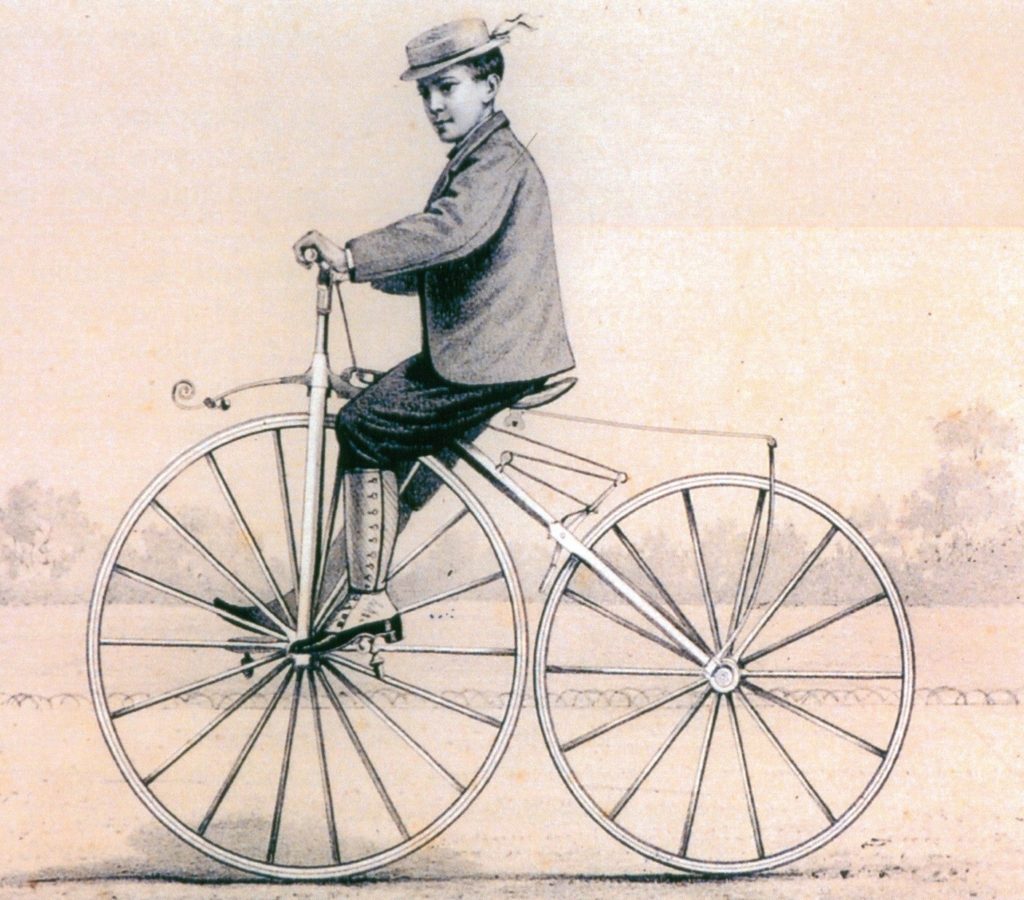

The two-wheeled velocipede or bicycle is in part a realisation of Mr Keene’s picture. It depends upon motion for its balance. The two wheels, one in front of the other, with a saddle between, whether mounted by a rider or not, will not stand upright for a single instant at rest; but, like the boy’s hoop, being kept trolling, they maintain a perfect equilibrium.

A Wonder Which Drove All Paris Mad

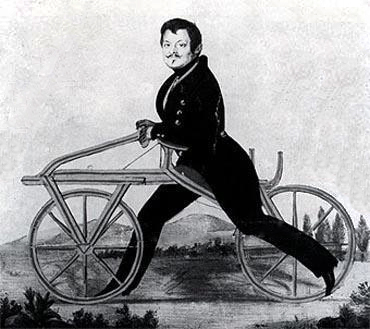

The bicycle can hardly be called a ‘new invention,’ being to a great extent a modification of that very old toy-vehicle of our fathers, the hobby-horse, whereon the rider used to sit and row himself along, so to speak, by paddling with his feet on the ground; at the same time, the entire reliance on the principle that motion would be, under any circumstances, sufficient to produce balance, is sufficiently novel almost to justify the use of such a term. The French appear to be entitled to whatever of credit attaches to the original invention of the hobby-horse (a miserable steed at best, which wore out the toes of a pair of boots at every journey. M. Blanchard, the celebrated aeronaut, and M. Masurier conjointly manufactured the first of these machines in 1779, which was then described as ‘a wonder which drove all Paris mad.’ The French are probably justified, moreover, in claiming as their own the development of this crude invention into the present velocipede, for, in 1862, a M. Riviere, a French subject, residing in England, deposited in the British Patent Office a minute specification of a machine identical with that now in use. His description was, however, unaccompanied by any drawing or sketch, and he seems to have taken no further steps in the matter than to register a theory which he never carried into practice. Subsequently, the bicycle was re-invented by the French and by the Americans almost simultaneously, and indeed, both nations claim priority in introducing it. It came into public notoriety at the last French International Exhibition, from which time the rage for them has gradually developed itself, until in this present 1869, it may be said, much as it was a century ago, that Paris has again been driven mad on velocipedes.

The two-wheeler, when on the turn, stands at an inclination like a skater’s body.

With regard to the speed which may be attained, fifteen miles an hour, under the most favourable circumstances, that is, good hard road, not level, but without very steep hills, and no wind blowing, is probably the limit of the velocipede’s powers; but a pace of nine or ten miles an hour may be maintained for five or six hours without distress. Long journeys on level road are perhaps the most fatiguing, on account of their monotony, because then the feet, as in walking, are nearly always at work. Still, even in this case, the driver can maintain his speed with one foot, resting the other on the leg-rest; or, if disposed, he may even place both feet on the rests, and run four or five hundred yards without working at all. The slightly increased labour of climbing a hill is nothing to the zest imparted by a knowledge that there is sure to be a hill the other side to go down, and that is the most luxurious travelling that can be imagined. Descending an incline at full speed, balanced on a beautifully tempered steel spring that takes every jolt from the road – wheels spinning over the ground so lightly they scarce seem to touch it – the driver’s legs rested comfortably on the cross-bar in front – shooting the hill at a speed of thirty or forty miles an hour – the sensation is only comparable to that of flying, and is worth all the pains it costs in learning to experience it.

The sensation is only comparable to that of flying.

The velocipedist feels but one pang when he reaches the bottom of a hill, and that is, that it is over; and but one exquisite wish, which is, that the entire country might somehow become metamorphosed into down-hill. But the hill is bountiful even after one has left it, for the impetus derived from a good incline will carry the rider at least the hill’s length on level ground before he need remove his feet from the rests and commence working again. The slightest incline on a good road is sufficient to obviate all necessity for working with the feet, so that what little labour there is (and it is of the easiest), is by no means incessant. In a journey of twenty miles on good road, a driver should not work more than twelve – the inclines do the rest. Of course, there are hills so steep that to ascend them is impossible: yet, for myself, living in a hilly county, which I have pretty well explored on my two-wheeled steed, I can reckon up their number on the fingers of one hand. There are also hills where the labour becomes as much as, or more than, walking, but these must be of a gradient something like one in twelve, and such hills are not frequent. When they do occur, the rider may, if he will, dismount.

Good hard road is essential for velocipede-driving. In muddy or loose gravelly road, the work becomes proportionately laborious. But with good ‘going ground,’ it is difficult to convey how little labour is really required to maintain a high rate of speed – in fact, the great trouble with beginners is to get them to restrain the expenditure of muscular force. Velocipede-driving is, I believe from experience, most healthy and exhilarating, since it exercises all the muscles of the limbs in a manner much more uniform than would at first be credited, and certainly without undue strain on any part of the body. To the spectator, the velocipedist appears almost wholly to employ his legs, but in reality the muscles of the arms are in strong tension in the act of grasping the handles, so as to counteract the motion of the feet on the pedals, which motion would otherwise tend to sway the wheel from side to side. In fact, after a long journey, the driver will feel more fatigue in his arms than in his legs. Once mastered, the two-wheeled steed is a docile and tractable animal, equally sensitive to bit and bridle, and a sturdy friend to the traveller. For him the pike-men throw open their gates without asking for toll. He needs neither corn nor beans, nor hay nor straw, neither hostler nor stableman. His stable is a bit of the passage-wall, against which he reposes, without taking up any room, until his master needs him again – his only food, a pennyworth of neat’s-foot oil per month.

Now that the supposition about the new velocipedes frightening horses has been proved to be groundless, there seems little reason to doubt they will become equally popular in this country; and that after the first ‘rage’ for the novelty has died away, the two-wheeled steed may drop into its proper place as a serviceable nag, that can do a great deal of work in a very little time, and, after the first cost, at a very inconsiderable expense.”

Though there are a few pretending to be …. Somebody desperately needs to write a comprehensive history of the Bicycle including everything .. from Motorcycles to Airplanes to the Automobile that sprang from the ubiquitous ever present bicycle .

Suffice it to say the lowly bicycle has quite the family tree

That sounds more like a history of industrial design…which would be enormous. We’re slowly doing that on The Vintagent, though…and who knows, it might become a video project one day.

Paul – Mea culpa . I guess I wasn’t clear enough about what I was thinking .

A better explanation

A comprehensive history of the bicycle with a special focus on all the M/C manufactures that grew out of bicycle manufacture and design with sidebars on the likes of the Wright Bros etc who got their start in bicycle shops and manufacturing . I know Ferriss and Alford took a stab at it with their book ” An Alternative History of Bicycles and Motorcycles ” but lets face it … 200 pages barely scratches the surface

And yes … bit by bit you are covering some of what I’m suggesting but I maintain a substantial book is still in order

BTW if I may … as you continue unveiling the history of two wheels … might I suggest a few articles on the bicycles that were the foundation of several ( albeit most now defunct ) American M/C builder/manufactures

Rock On – Ride On – Remain Calm ( despite all the bs surrounding us ) and do Carry On

gtrslngr

Pierce! Reading-Standard! Indian! Rudge! Triumph! FN! Victoria! etc. A great idea, many thanks.

The Velocipede Museum recently relocated from Delaware to Newburgh NY. They are now affiliated with the nearby Motorcyclepedia Museum. “Two-Wheeled Steeds” abound in this Orange County city on the Hudson River. History preserved for two wheeled transportation. Website link below and Velocipede has a Facebook page with regular postings.

Thanks for your great work as The Vintagent!

Bonsoir,

Ce n’est pas possible que dans cet article il y est autant d’erreur et d’affabulations et cela dès le début. Vous affirmez d’emblée “Le prototype cycliste Dandy, vers 1869, avec un cycle à pédales Michaux du premier type. “.Ce vélocipède à pédales ou Véloce n’ets pas un Michaux, ni même un Compagnie Parisienne. Il n’est pas non plus du 1er type car le corps du 1er type est cintré comme dans le brevet de 1866 signé Pierre Lallemant et James Carroll. Il est à corps droit, c’est donc obligatoirment celui du second type dont le brevet déposé le 23 juin 868 fut attribué définitivement aux frères Marius, Aimé et Pierre Olivier les ex-associés de Pierre Michaux, par le ribunal de commerce de la Seine le 0 octobre 1869. Enfin ce Véloce est de type Grand Bi, pour grand bicycle, donc après 1869. Et ce n’est pas finit !

Et je continu, vous pompez wikipédia, pour cela je serais plus clément : “Karl Von Drais a inventé la « Laufsmachine » (machine à courir), présentée pour la première fois au monde le 12 juin 1817 à Mannheim, en Allemagne (…) le ‘celerifere’ a été inventé en 1790 par le comte Mede de Sivrac en France”. Là c’est du délire, il n’y a pas eu de Karl von Drais mais bien un Carl baron de Drais avec un C et non un K et il signait Freiherr von Drais, j’ai les copie de ses archives. Carl de Drais – simplifions – n’était pas allemand mais Badois du Grand Duché de Bade (1806-1870). Il n’a pas inventé la “Laufamaschine” car ce n’est pas lui qui l’a nommé ainsi, il l’a nommé f”farhmashine” le 12 juin 1817, “machine à courir” le 8 novembre 1817 et enfin “Draisine” le 30 juin 1920. Celui qui la nomma “Laufmaschine” le 1er et le marchand S. Bauer le 3 décembre 1817. Quant au Célérifère, c’est une voiture hippomobile, inventée par le toulousin Jean Henri Sièvrac qui en déposa le brevet d’invention le 4 juin 1817……..Il n’y a vraiment rien de sérieux dans ce texte où se mélange réalité et légende…….Je poursuit !

“Le vélo peut difficilement être qualifié de « nouvelle invention », étant dans une large mesure une modification de ce très vieux véhicule-jouet de nos pères, le cheval de loisir”, C’est tout le contraire, la farhmaschine devenue en France le 19 janvier 1818 le vélocipède est bien une invention nouvelle. J’aurais aimé qu’il fut français mais il fut badois ainsi va l’histoire !

Le reste du paragraphe est donc faut, la machine de Blancherd et Masurier, son gendre, comme toutes les autres antérieur au 12 juin 1917 ont 4 roues et cerrtaines sont démunies de tout système de direction, si bien qu’à chaque déviation de trajectoire, on descend, on lève, on réaligne et on ne peut repartir qu’en ligne droite. Seule celle de Stephan Farffler d’Altdorf du 24 octobre 1689 pourrait être désigné comme ancêtre du vélocipède mais c’est un trois roues, il n’a lui non plus aucune direction et ne requiert aucun équilibre…Et là je peu fournir tous les documents d’époque, descriptifs et dessins…… Le reste de se paragraphe est une plaisanterie……..La suite

“Le vélo peut difficilement être qualifié de « nouvelle invention », étant dans une large mesure une modification de ce très vieux véhicule-jouet de nos pères, le cheval de loisir”, C’est tout le contraire, la farhmaschine devenue en France le 19 janvier 1818 le vélocipède est bien une invention nouvelle. J’aurais aimé qu’il fut français mais il fut badois ainsi va l’histoire !

Le reste du paragraphe est donc faut, la machine de Blancherd et Masurier, son gendre, comme toutes les autres antérieur au 12 juin 1917 ont 4 roues et cerrtaines sont démunies de tout système de direction, si bien qu’à chaque déviation de trajectoire, on descend, on lève, on réaligne et on ne peut repartir qu’en ligne droite. Seule celle de Stephan Farffler d’Altdorf du 24 octobre 1689 pourrait être désigné comme ancêtre du vélocipède mais c’est un trois roues, il n’a lui non plus aucune direction et ne requiert aucun équilibre…Et là je peu fournir tous les documents d’époque, descriptifs et dessins…… Le reste de se paragraphe est une plaisanterie……..

“La bicyclette a été réinventée par les Français et par les Américains presque simultanément, et en effet, les deux nations revendiquent la priorité dans son introduction”. … Je pense que mon traducteur introduit une erreure transformant le mot “bicycle” en “bicyclette” alors qu’il est question ici de vélocipède à pédales ou Véloce………Ici on confond “bicyclette” ou “the bicyclette” avec le vélocipède à pédales ou Véloce. En effet, c’est en France le 1er avril 1866 (Journal de l’Ain) que furent apperçus et détaillés 3 jeunes gens venant de Lyon et chevauchant chacun un vélocipède à pédales, c’est-à-dire un véhicule à deux roues alignées dont la roue avant est actionnée au moyen de pédales rotatives à 360°, le doute n’est pas permis. Puis c’est le 4 avril suivant qu’à New Haven qu’un journaliste du New Haven Dailly Palladium décrit sous le titre Tandem – pour deux roues l’une derrière l’autre au lieu de deux chevaux – un “two wheels following each other, and driven by foot-cranck..”, c’est aussi sans conteste un vélocipède à pédales.ou Véloce.

Dans cette avanture vers la Bicyclette, véhicule écologique entièrement recyclable et le plus fabriqué dans le monde aujourd’hui, le plus important est l’inventeur de la pédale rotative à 360° et du pédalier. Cette invention on la doit au pharmacien Jules Sourrisseau qui l’inventa le 14 octobre 1853 qui l’a dénomma Manivelle Pédiforce. Sans cette pédale, le vélo serait resté le véhicule primitif qu’il était. Hélas, on ne connait pas les 3 jeunes gens venant de Lyon et on peut supposer que le cycliste vu à New Haven pourrait être Pierre Lallement ou James Carroll. Ce qui est certain aujourd’hui, depuis notre ouvrage, que la pédale n’a pas été adaptée à un vélocipède (celui de Drais) par Pierre ou Ernest Michaux, aucun document ne l’atteste….. à suivre

La “bicyclette”‘, le véhicule a bien été inventé par un français. On la doit à l’ingénieur Charles Desnos-Gardissal ui en a déposé le brevet (addition) le 23 octobre 1868 mais il ne l’a pas dénommé. le mot “The Bicyclette” est lié sans conteste à l’anglais Henry John Lawson qui dénomme son “Bicycle or Velocipède” en 1880 dans le catalogue de chez Ariel Works, page 7 et 14, dont il est le directeur. Bicyclette serait composé du latin Bi = 2, Cycle = roue et ette = diminutif, que l’on peut traduire par le “petit bicycle ou le petit deux roues”.

Je suis d’accord avec vous, 1869 est l’année du vélocipède à pédales en France car il fut déposé 187 brevets d’invention mais aux Etatus Unis, c’est 1868 avec 137 brevets !

Enfin je susi aussi d’accord avec vous concernant le vélocipède à pédales de la maison Michaux et Cie qui fut adopté par tous à travers le monde. Toutefois j’y mets un bémole car la maison Michaux et Cie était une association entre PierreMichaux et la fraterie Marius , Aimé et Pierre Olivier. Le Véloce adoptait par tous avait un cadre droit brevet, Marius, Aimé et René Olivier et se fut à eux que Pierre Michaux vendit, non seulement les actions qu’il détenait mais aussi sa marque Michaux le 6 avril 1869. Michaux et Cie fut intégré à la société Olivier frères diteb Compagnie Parisienne, Pierre Michaux étant partie. Et on doit à Olivier frères de fabriquait industriellement le vélocipède pédales.

Ernest Michaux, fils de Pierre, qui a probablement inventé le cycle à pédales avec Pierre Lallemont, et a construit les premiers exemplaires au début des années 1860 dans l’atelier de son père [Wikipedia]…………Ca c’est faux, avez vous un document antérieur au 1er avril 1866 avec un vélocipède à pédales tel que vous le présentez ? Ce n’est pas Pierre LallemOnt mais Pierre LallemAnt, avec un A.

“La « sensation de voler » a inspiré le concept d’ajouter un moteur au vélo, pour prolonger la sensation indéfiniment. Comme ils avaient raison! Les joies de la moto ont été imaginées dans les années 1860″…..Inventer c’est trouver quelque chose de nouveau (définition de l’accadémie française de 1815), or dès 1818 et plus précisemment dès le 5 avril parraissait une chromolitographie carricaturale et imaginaire représentant dans les allées du jardin du Luxembourg à Paris, un vélocipède mu par la vapeur. C’est là quelques chose s de nouveau même si cela était de la fiction, l’idée allé germer puisqu’en 1820 Carl baron de Drais, lui même, dit dans une interview du 22 juin “‘je pense améliorer Draisine par la vapeur..En conclusion dès 1820 on est certain que le vélocipède allait se muer en “motocyclette”, le véhicule et pas le mot…..Donc pas dans les années 1860 mais autours de 1820, CQFD !

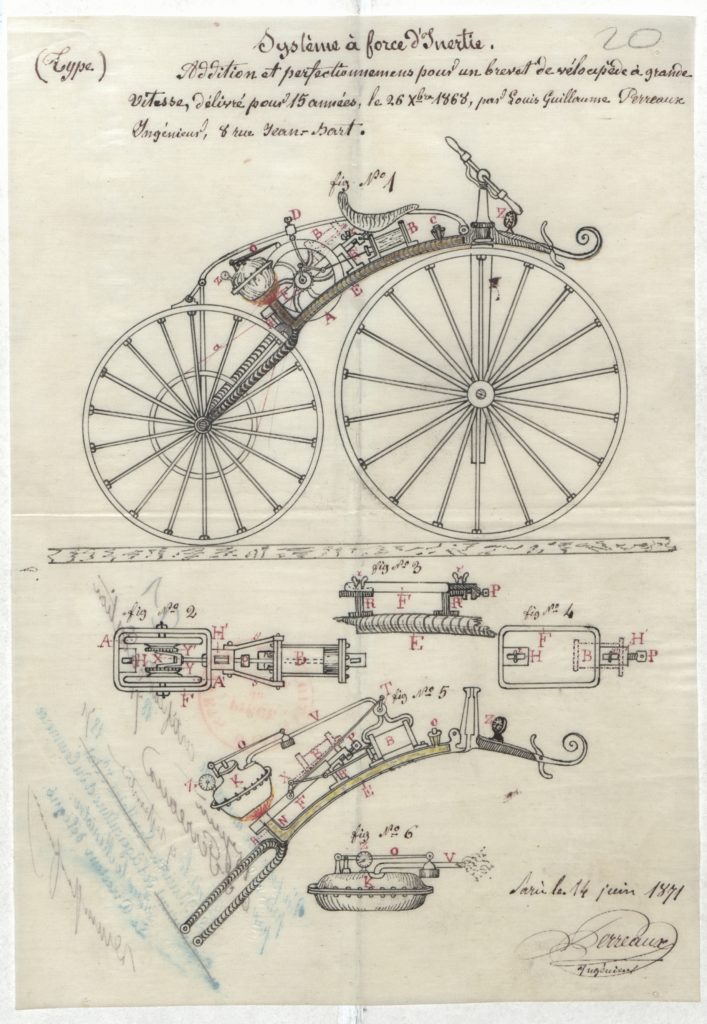

” Louis-Guillame Perraux a breveté son vélocipède à vapeur en 1871, en utilisant un vélo Michaux avec une petite machine à vapeur modifiée à cet effet”. C’est encore faux, le vélocipiède à pédales utilisait est bien à corps droit, brevet Olivier frères, mais en aucun cas ce n’est un Michaux, c’est une pure création de Louis-Guillaume Perreau.

Encore une contre vérité, le Vélocipède à rande vitesse de L-G Perreaux, conservé au musée de Sceaux, ne peut pas être de 1871. En effet, lors des 1er essais véritable de ce vélocipède à grande vitesse à vapeur, le jornal La Presse du 19 juillet 1874 rapporte que la chaudière de celui-ci a explosé rue de la Barre sous son inventeur qui ne fut que très légérement blessé…………La conclusion s’impose, le vélocipède survivant n’est pas de 1871 ni même de 1874 mais après !

Pierre Lallemont en 1866, démontrant son cycle à pédales, qu’il a breveté aux États-Unis, mais développé dans l’atelier de Pierre Michaux [Wikipedia]….Pour finir, la gravure de Pierre LallemAnt et non LallemOnt sur un vélocipède soit disant de 1866 ne peut l’être de cette année-là. Son brevet américain le trahit puisque le 30 avril 1866, avec James Carroll, il a breveté un”improvement in vélocipdes” avec une machine à corps cintré alors que le corps droit fut breveté abusivement le 23 juin 1868 par Pierre Michaux et que le tribinal de commerce de la Seine restitua aux Olivier frères le 11 octobre 1869 par décision de justice…………En conséquence, en 1866, Pierre Lallemant ignoré tout du corps droit, ce n’est qu’en revenant en France en 1869 qu’il découvrit le corps droit. D’ailleurs installé comme constructeur de vélocipède en 1869, Pierre Lallemant fut client de la Compagnie parisienne (Olivier fères), amusant n’estil pas ?….En conclusion Pierre Lallemant est bien sur un vélocipède à pédales assemblés par lui avec des pièces provenant de la Compagnie Parisienne,il n’est donc plus en 1869 qu’un simple assembleur parisien comme tant d’autres.

Pour Sylvester H. Roper et 1860, je me garderais bien de tout commentaire car aucun journaux américain avant 1870 ne font état d’une machine à vapeur signé Ropper et ayant circuler.

Jolie texte mais hélàs entaché d’erreure, bien à vous, je suis à votre disposition pour de plus amples informations et vous transmettre les documents authentiques et sources si besoi,n qui vbous manques. Vous noterez que je donnes le jour, le mois et l’année de toute mes remarques ici……….: mahistre@aol.com