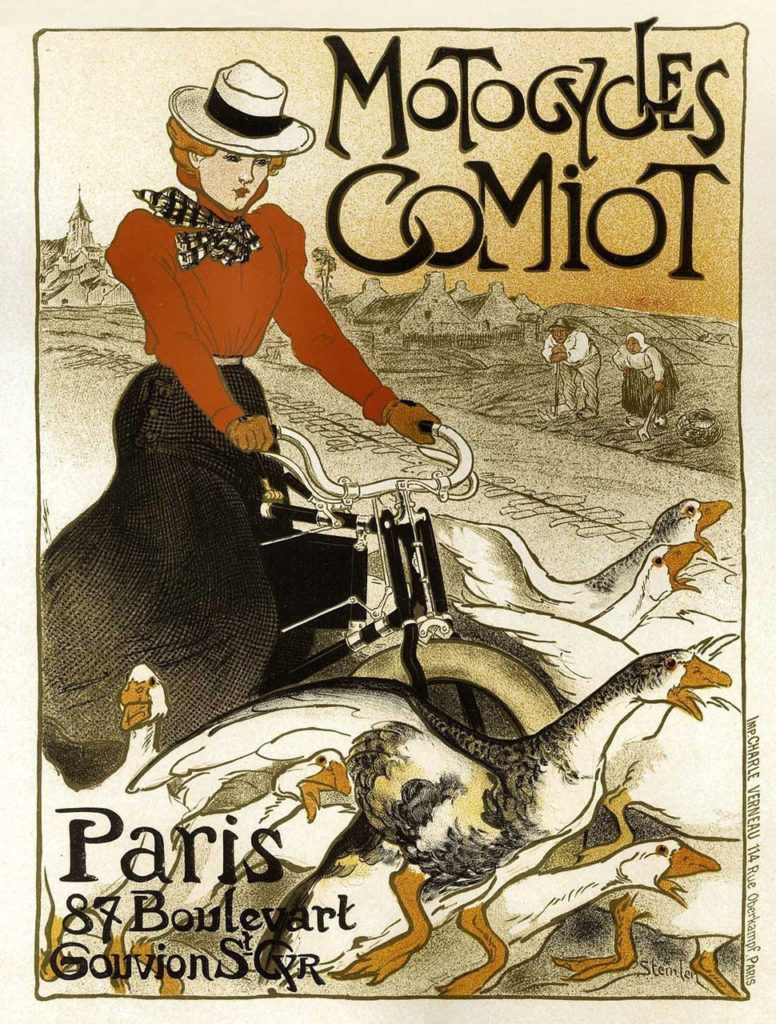

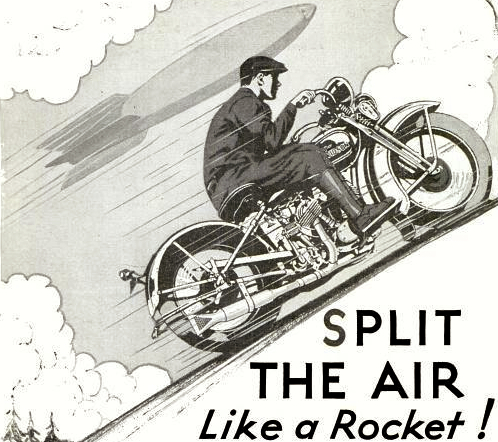

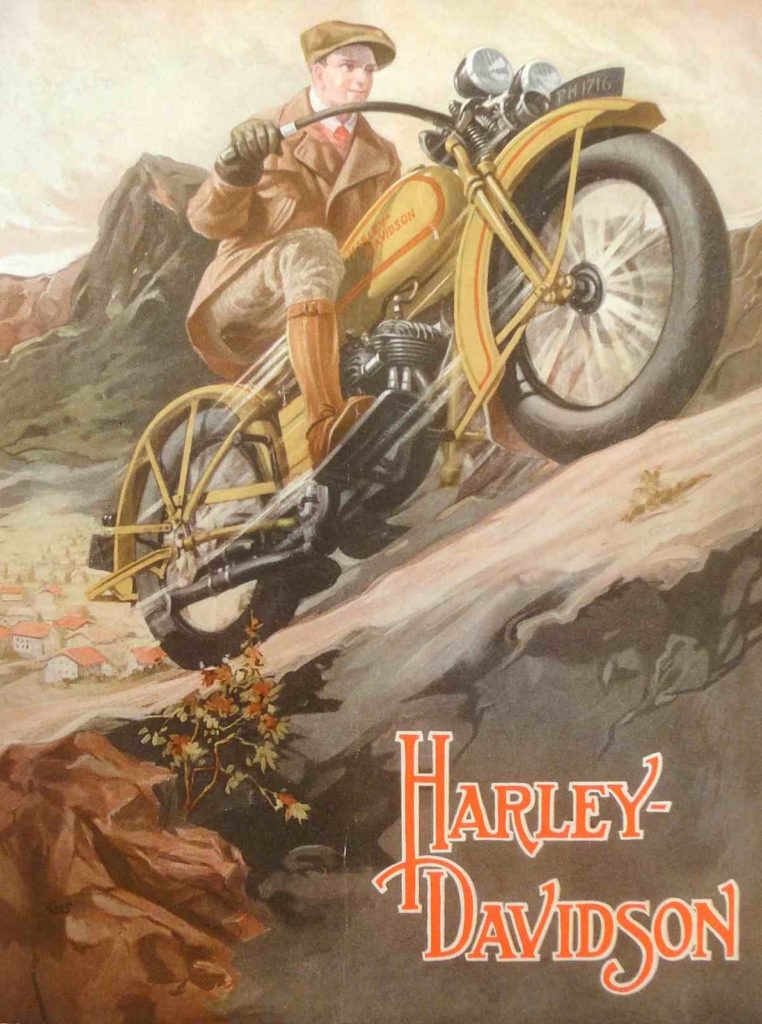

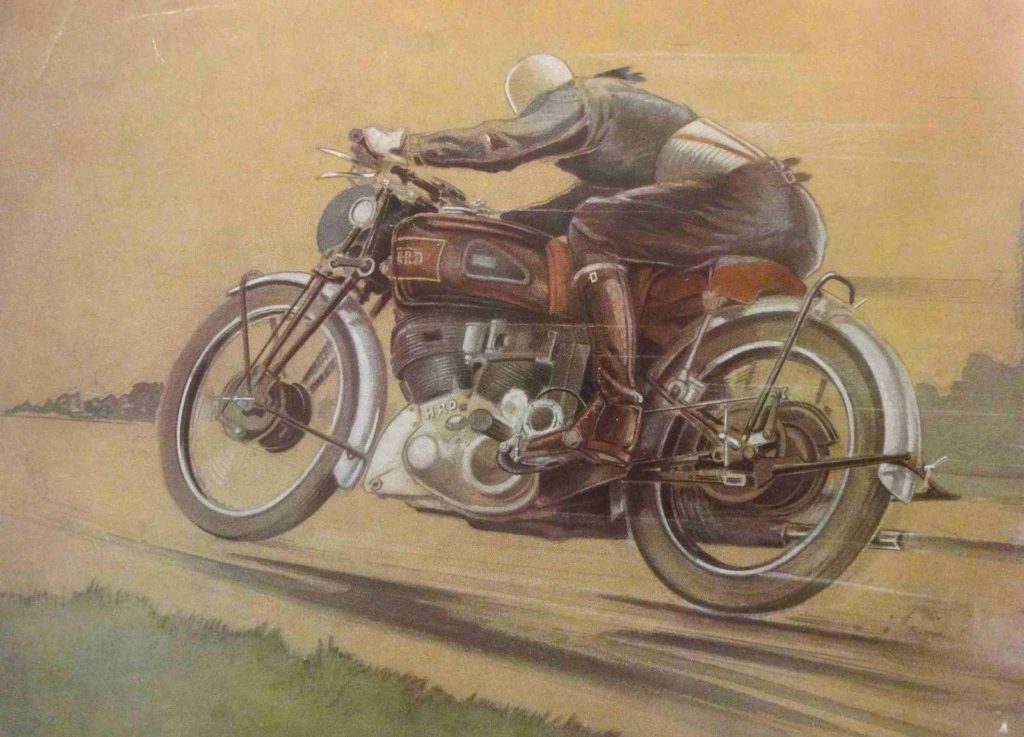

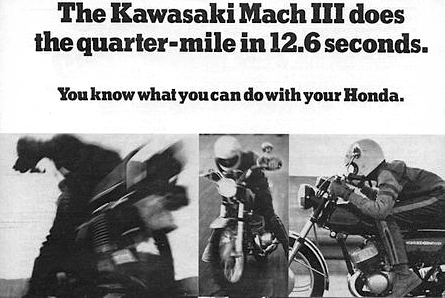

The first motorcycle race started when the second motorcycle was built. And the first motorcycle advertisement was placed immediately post-finish, crowing the winner’s superiority. Motorcycle ads have a natural ‘hook’ in the lure of Speed, although manufacturers have had mixed feelings about selling what riders really wanted, deep down in their speed-demon souls. From the first days of the 20th Century, builders and buyers of motorcycles have played a complex dance around the subject of Speed, with the Industry anxious to spread a message of respectability and docility for their noisy, horse-scaring moto-bicycles, keeping a low profile about the exhilaration of pulling the throttle lever all the way back. Customers were savvy to the game, navigating the great restrictive forces of Love and Law – parents, spouses, and the police – who could not abide an explicit celebration of the narcotic draw of Competition and its handmaiden, Danger. It took decades before the public acknowledged that a dangerous, speed-crazed hooligan lurks in the puritan hearts of all motorcyclists, hell-bent on going faster than anyone on the damn road.

Very well written Paul, and a great angle on capturing the history of motorcycles in pop culture. I studied art and design in college and was always fascinated by the reflection of society in advertising though out the various decades. I could comment on this further, but I think you pretty much summed it all up with this articulate piece. I’m going to share it with some of my more “thoughtful” design friends as I think this transcends the motorcycle crowd.

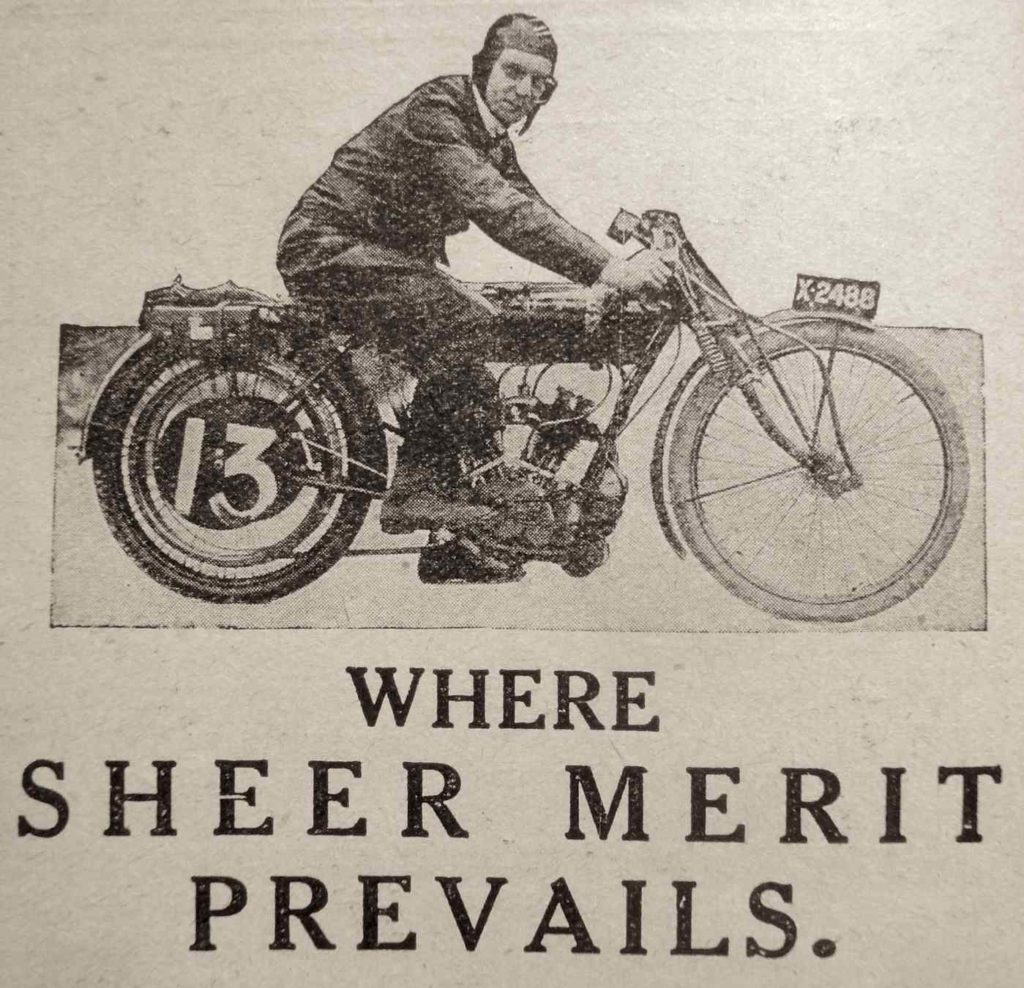

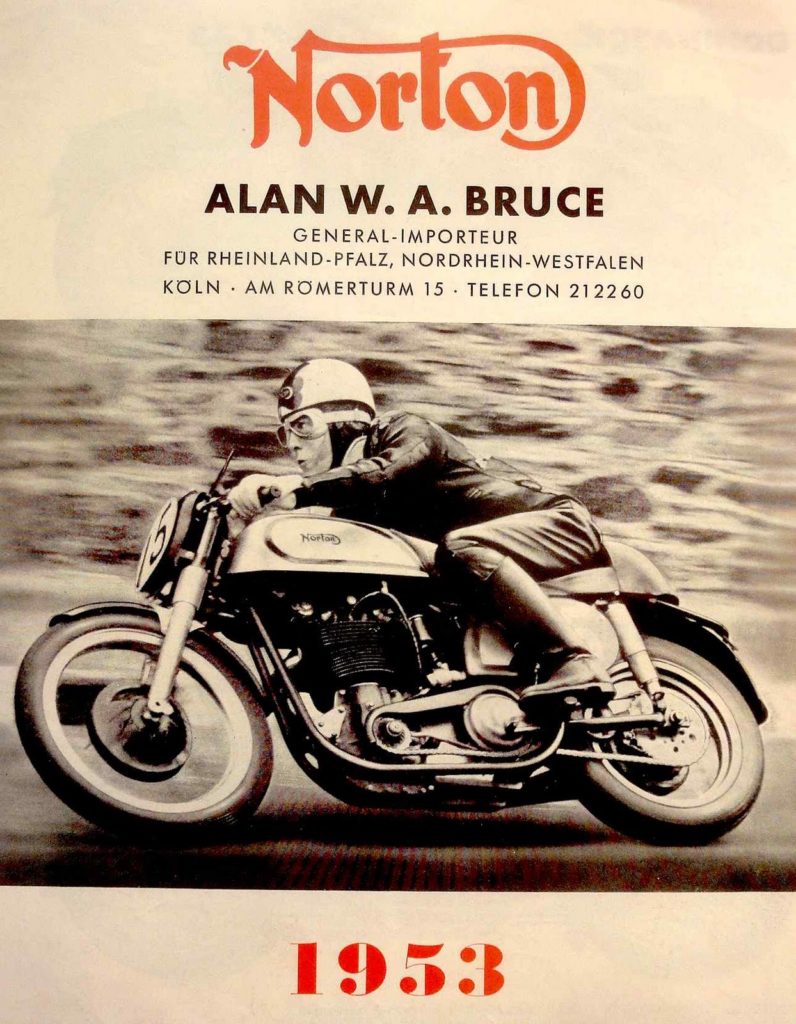

Nice pic of Reg Armstrong on the works Norton, the year they fitted the small rear wheel…

Very well written mega-post. The quality and presentation are excellent. You’re still the best blogger out there when it comes to vintage motorcycles and cycle culture.

I’ve not known the style of the french posters until now, thanks.

Dear Prfessor d’Orleans:

Will you please assist me with obtaining college credits for your course in “Motorcycling, it’s history and art 201”

So far the Veteran’s administration has denied my request for GI Bill benefits claiming that your curriculum is not accredited. But, as I’m sure I told you before “THEY”RE FULL OF SHIT”

Nowhere else on this planet is anyone doing as comprehensive and insightful coverage of motorcyclings vast history as U of V (that’s University of the Vintagent).

I’m sure a brief letter from you will unlock the doors to the Veterans Administration treasury so that I will be able to afford your tuition, even though it will probably go up.

Your’s failfully in srvice,

Jerome S. Kaplan

1st Lt. US Army Quartermaster Corps. Ret.

Excellent article. Thanks for a great morning coffee read.

Hats off again Sir.

Thanks for the class.

Like everyone else said, tremendous post and great images, thank you!

Great post Paul, really interesting stuff.

Your “SELLING SPEED” was a superb piece of work, and much enhanced with the period ads.

– Old MJ

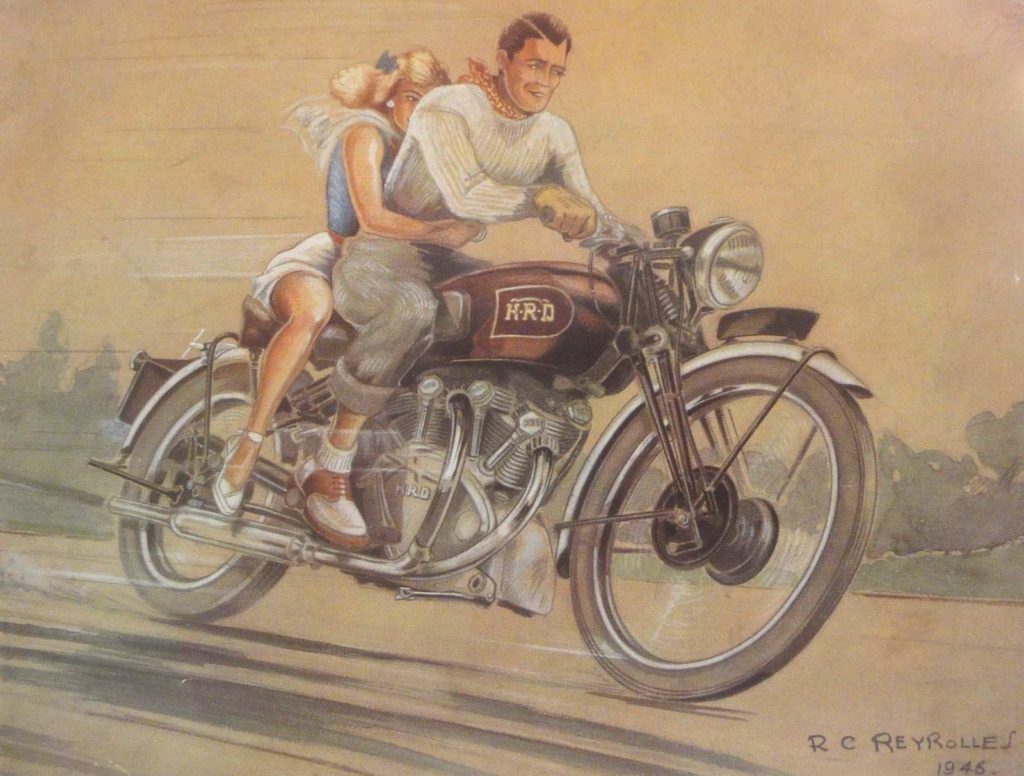

A great article with great illustrations. Thank you for including my personal favorite, the clinging girlfriend on the Vincent-HRD painting.

I would just like to mention, in connection with the influence of magazines, that the first requirement of a regular magazine is COPY. “Cooking” motorcycles that barely changed even in color from year to year could not provide the required fodder (although they were what most people bought). But competition could Feed The Monster, with page-after-page of racing reports. These had their effect on readers and advertisers, as you document.

But did those ads and articles actually sell motorcycles? You weren’t going to really ride that fast. So the answer, for most buyers, was the answer to the question “how much extra are you willing to pay for braggng rights?” More vanished motorcycle builders of old would still be in business today if they had made a better study of the motorcycles in the parking lot at the race track instead of those on the track.

Many great writers covered competition events, but my favorite was Rob Walker, of Road & Track, whose Grand Prix (auto) coverage was humorous and distinctly human. (You may recall that his every report included a mention of the adequacy of rest-room facilities at the track.) Otherwise, as a reader I had no interest in racing coverage.

Great points!

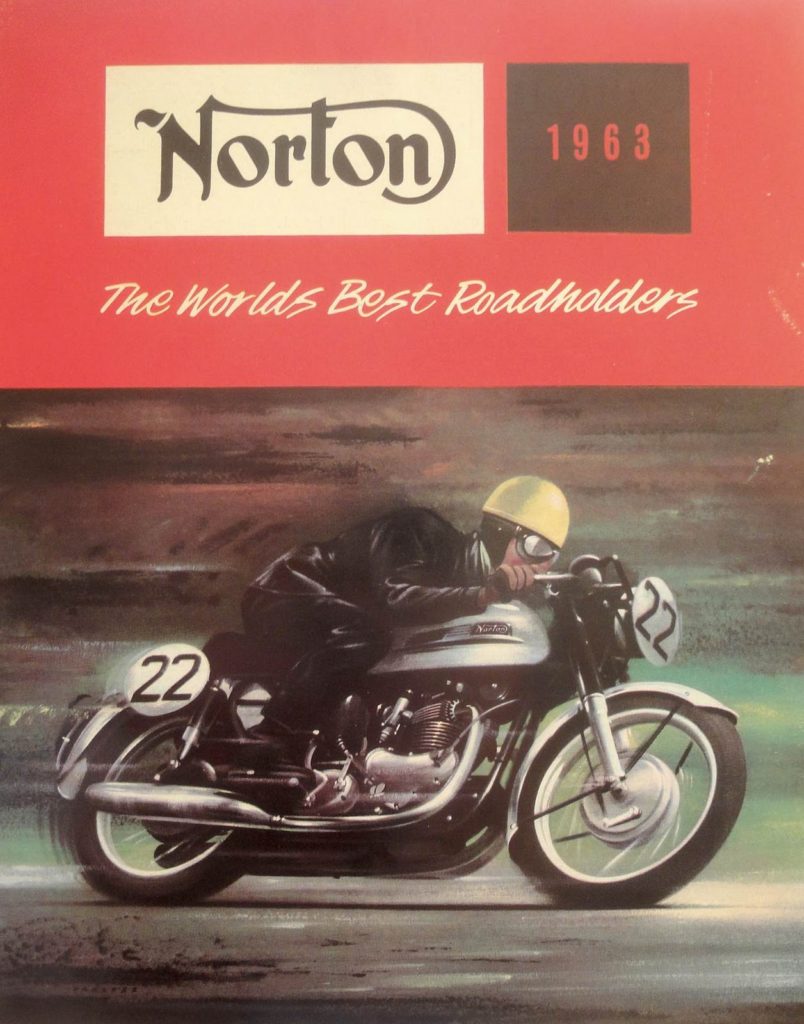

I’d say there have always been ‘influencers’, or cool kids, or role models, who had a lot to do with the desire for a fast motorcycle. Note I said ‘desire’, because very often what was actually purchased was a standard machine, not a race replica. So the race replica, or café racer, was the image factories often used to sell machines, knowing the bulk of sales was ordinary bikes. I’m currently writing a look about this very subject for Motorbooks, to be titled ‘Ton Up! Cafe Racer Speed, Style, and Culture,’ which explores the phenomenon going back into the 1900s.

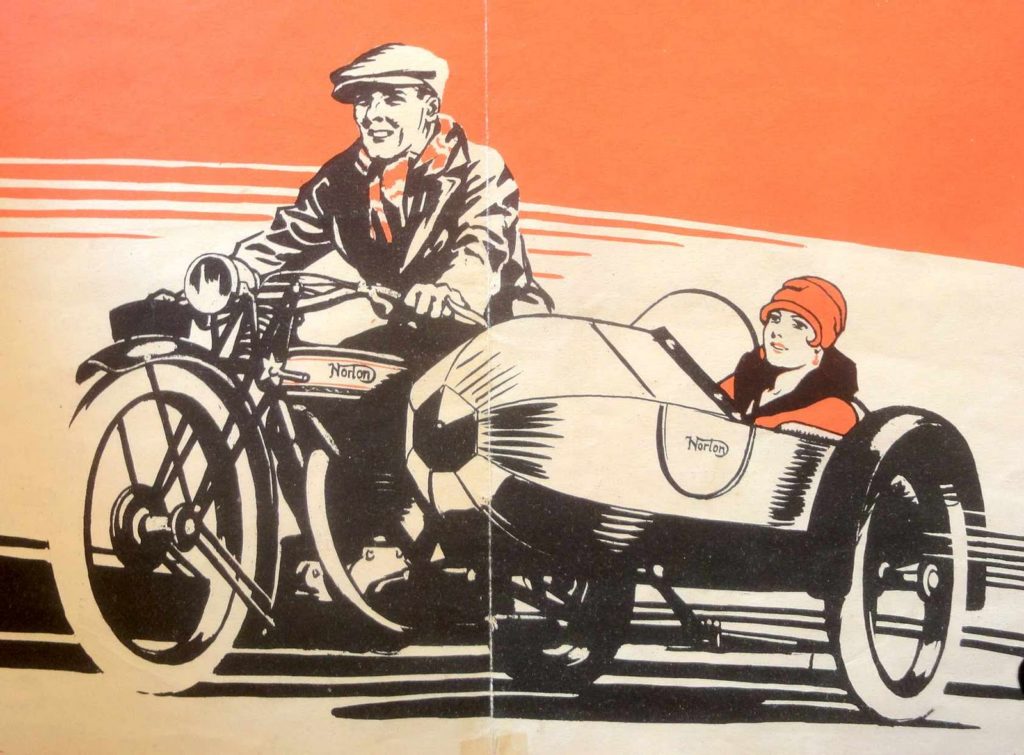

I think Norton sold the first race replica built for the street (or factory café racer) in 1914, with the Brooklands Road Special, a name that really says it all. What followed were generations of TT Replicas, Ulsters, Grand Prixs, Super Sports, Imolas, Gold Stars, Thruxtons, etc.

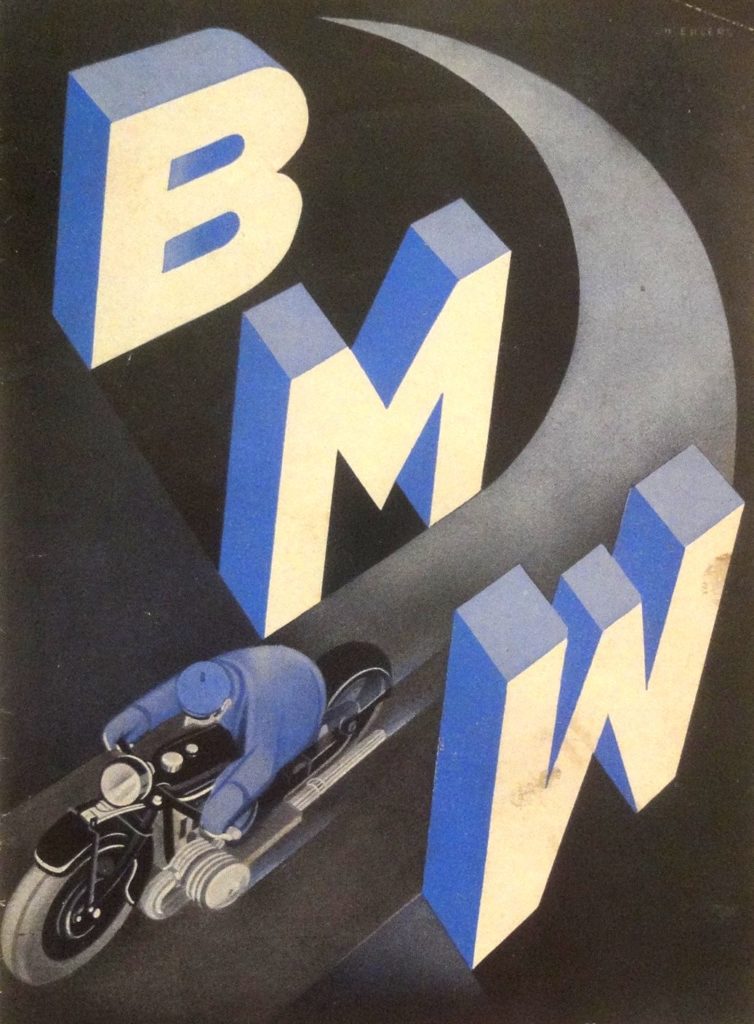

I’m not sure if manufacturers had paid better attention to what riders actually rode would have helped them survive: the USA had over 300 makes in the early years, and was down to 2 by 1930. The British industry never recovered from the devastation of WW2, and with no access to capital to totally renovate production methods (as the Japanese got from their gov’t in the early 1950s), there was no chance for survival by the 1960s – there was no money to modernize. The German industry was leveled in the late 1950s and early ’60s, as that country belatedly switched to cars for transport, and BMW was left as the basically last man standing.

The motorcycle industry is ever-changing, and very difficult to adapt to for manufacturers, who are just trying to make the best bikes they can for the price. The most successful factories today, by far, are selling commuter bikes – the Indian industry, and Japanese licensees in Asia, simply dwarf the rest of the world’s motorcycle production. For example, Royal Enfield is the SMALLEST manufacturer in India, selling about 800,000 motorcycles/year, but that’s the equivalent of H-D, Triumph, Ducati, Moto Guzzi, and KTM COMBINED. The biggest Indian companies like Mahindra and TVR sell millions of bikes every month. So, in a sense, you’re right about building what people actually ride – but no manufacturer in Europe or the USA has the stomach for it.

As a graphic artist and photographer with a passion for antique and vintage motorcycles I found this article to be an insightful, stimulating blend of art history and motorcycle culture. Bravo!

This may be the best article ever on the history of motorcycling. Full of serious insight and knowledge of the larger contexts design and social history.