That tired orange Duster with its 318 cubic inch V8 engine was thirsty for both fuel and oil, but it traveled the 380 miles to Saskatoon. After meeting dad Ray, Dave immediately wanted to show me what was in the garage. A lifelong motorcyclist who commuted to his job as a press operator from the moment it was warm enough to ride in the spring until the frost would form on his beard in the fall, Ray’s two-car garage held a daily-ridden Harley-Davidson along with a couple of projects in pieces. Tucked into a corner, however, was a dusty Triumph Bonneville. I went straight for the Triumph, thinking it a rather attractive motorcycle.

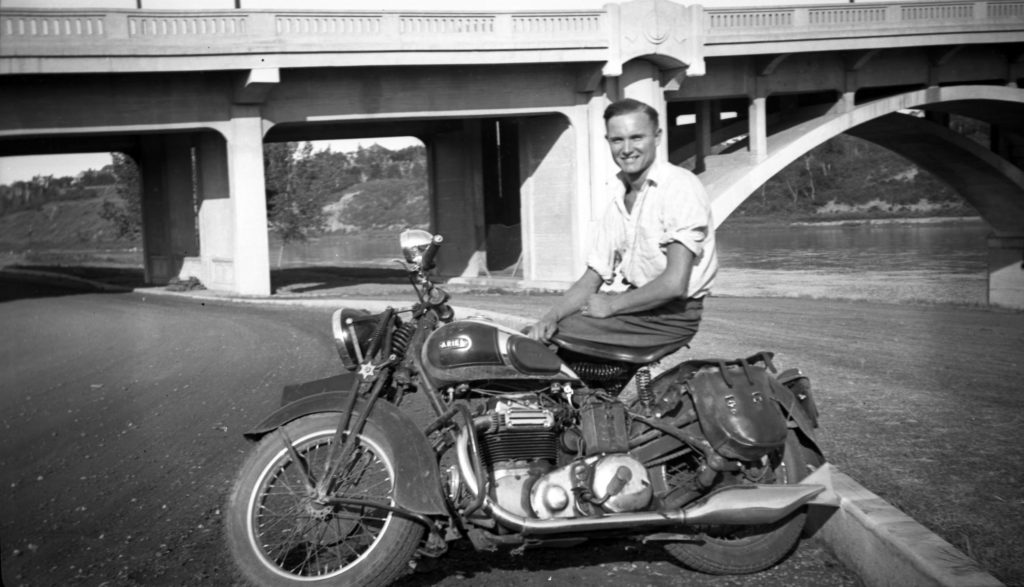

Until I saw the Triumph in Ray’s garage. Although it took me another three years, and with a substantial loan from a very sympathetic girlfriend who is still by my side, I finally managed to secure the purchase of a 1971 Triumph TR6R. When I bought the bike, the seller handed me a greasy, dog-eared catalog and said, “If you ever need any parts or advice, call up these guys.”

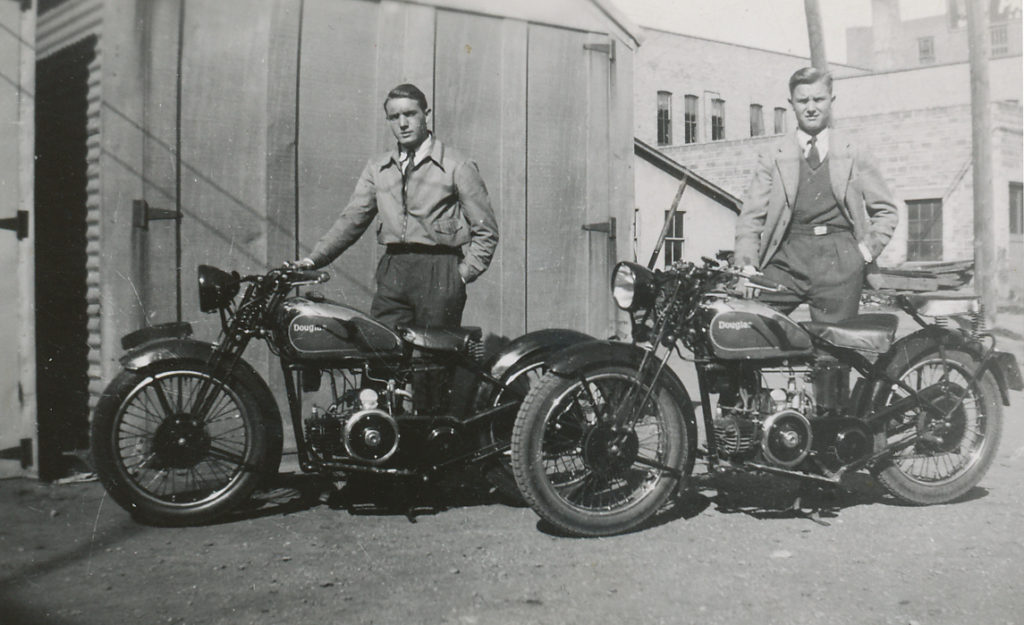

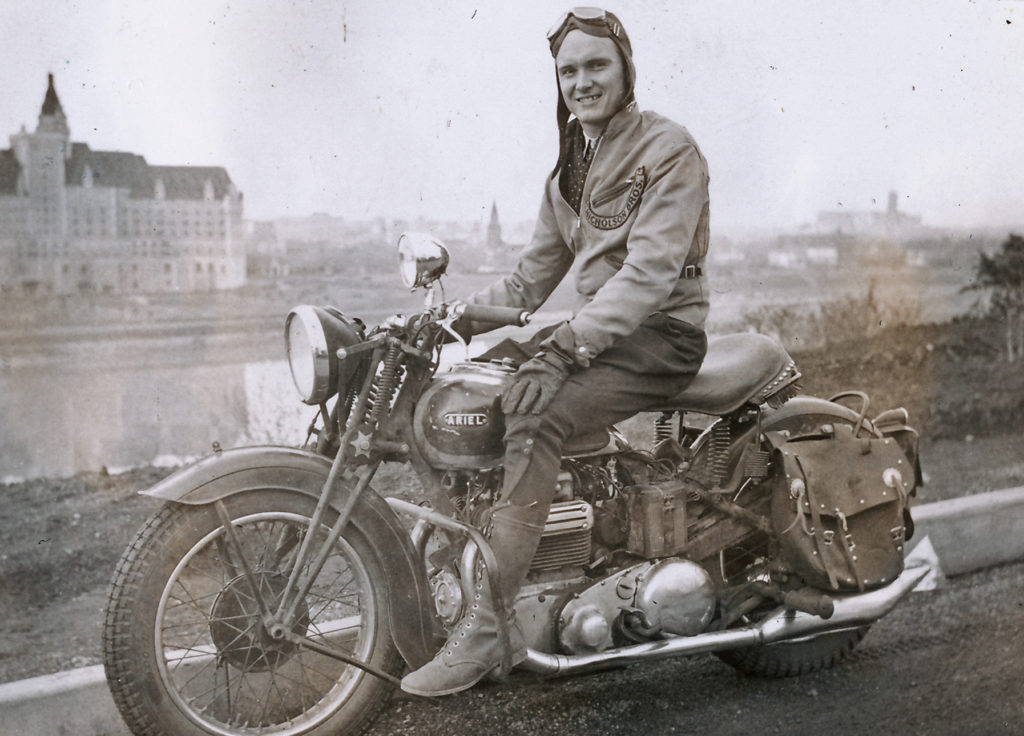

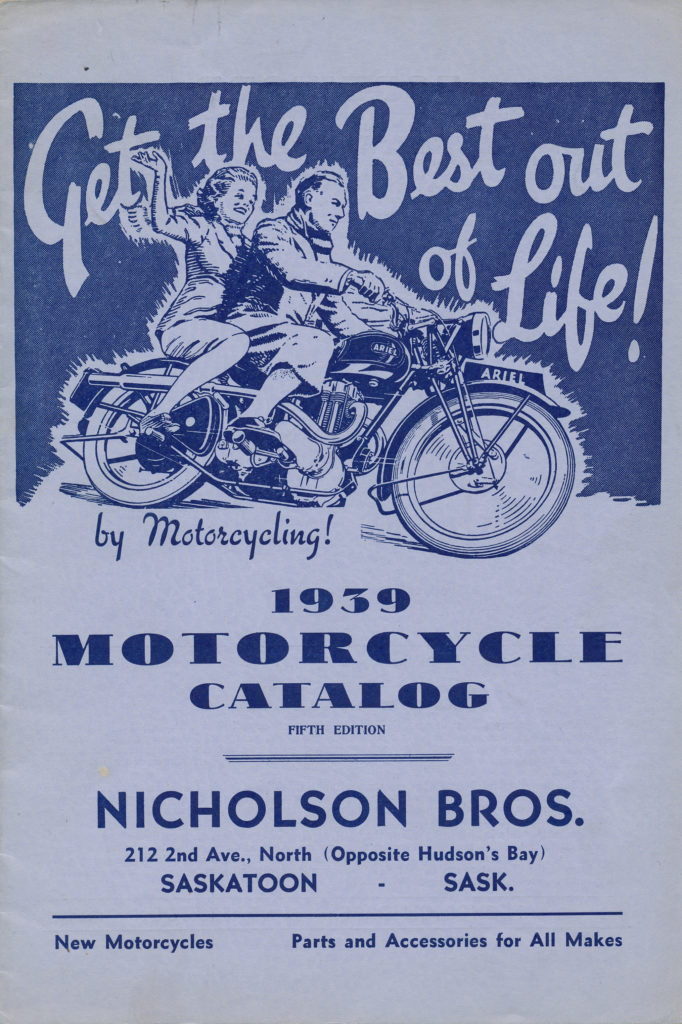

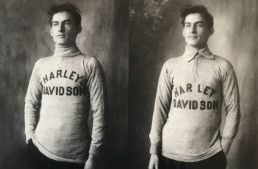

The Nicholson boys were eldest brother Lawrence and his sibling Bernie. Motorcycle-crazy from a young age in Saskatoon, in 1932 when they were 17 and 14 years old, they imported their first British machine, a 198cc DOT. By 1933, they’d put a few miles on the DOT, managed to sell it for a profit, and ordered more English motorcycles. Behind their parents’ apartment block, they used wood from the packing crates to knock together a shed, officially becoming Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles.

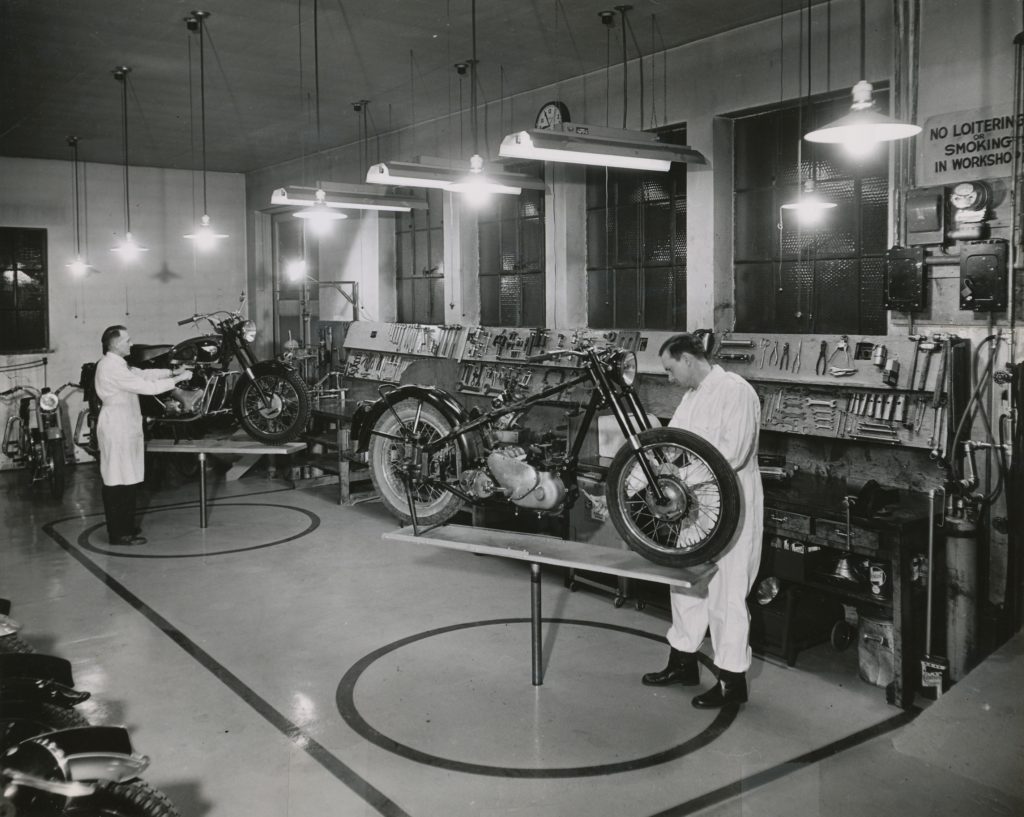

After high school, Lawrence and Bernie attended Saskatoon Technical Collegiate and graduated from the Motor Engineering and Machining program. While they’d already acquired much hands-on repair knowledge, at Tech they honed their skills and learned how to properly operate tooling such as a metal lathe, cylinder boring bar and valve grinding equipment.

Although young, both brothers were exceptionally bright and competent in handling business and wrenches. They were as inquisitive, genuine and honest as a Prairie summer day is long and that helped earn them much trust. Leaving behind the wooden shed, a brick and mortar location in downtown Saskatoon saw the brothers firmly established, where Lawrence looked after the business side of the operation while Bernie, who seemed to be somewhat more mechanically gifted, naturally gravitated towards service.

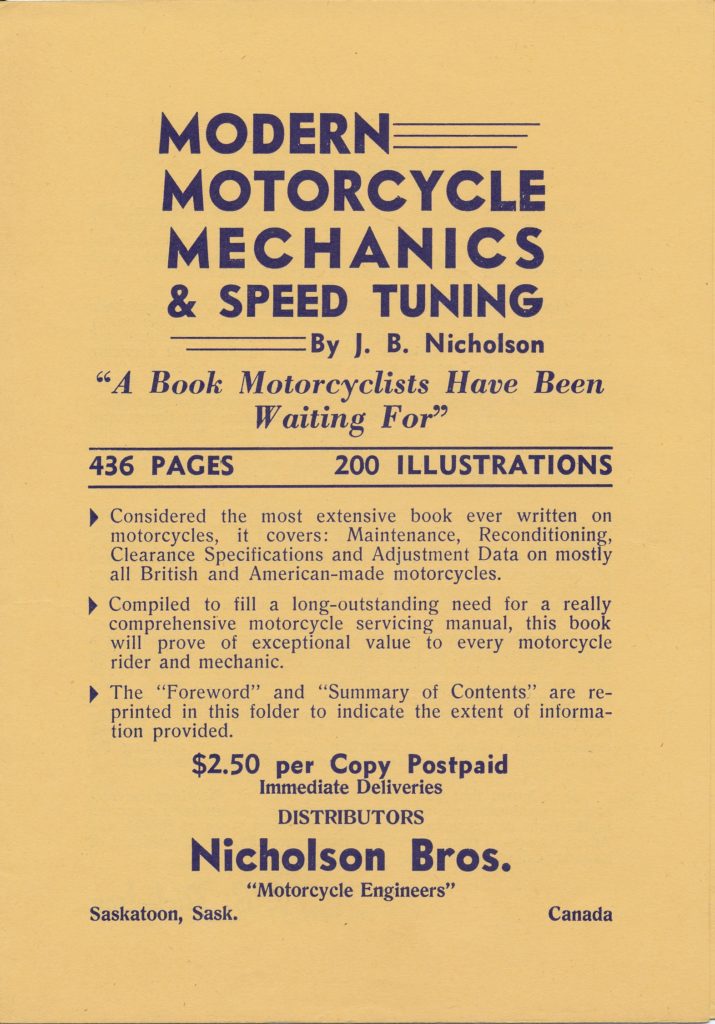

Now, with motorcycles being sold by Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles and shipped by rail to all corners of Canada and some locations in the U.S., consistent repair advice became a necessary commodity. Many of the British machines, however, simply were not supplied with anything that could be considered an essential owner’s manual. To remedy the drought of reliable information, it was J.B. Nicholson who sat down at a typewriter to begin work on a book he’d call Modern Motorcycle Mechanics and Speed Tuning.

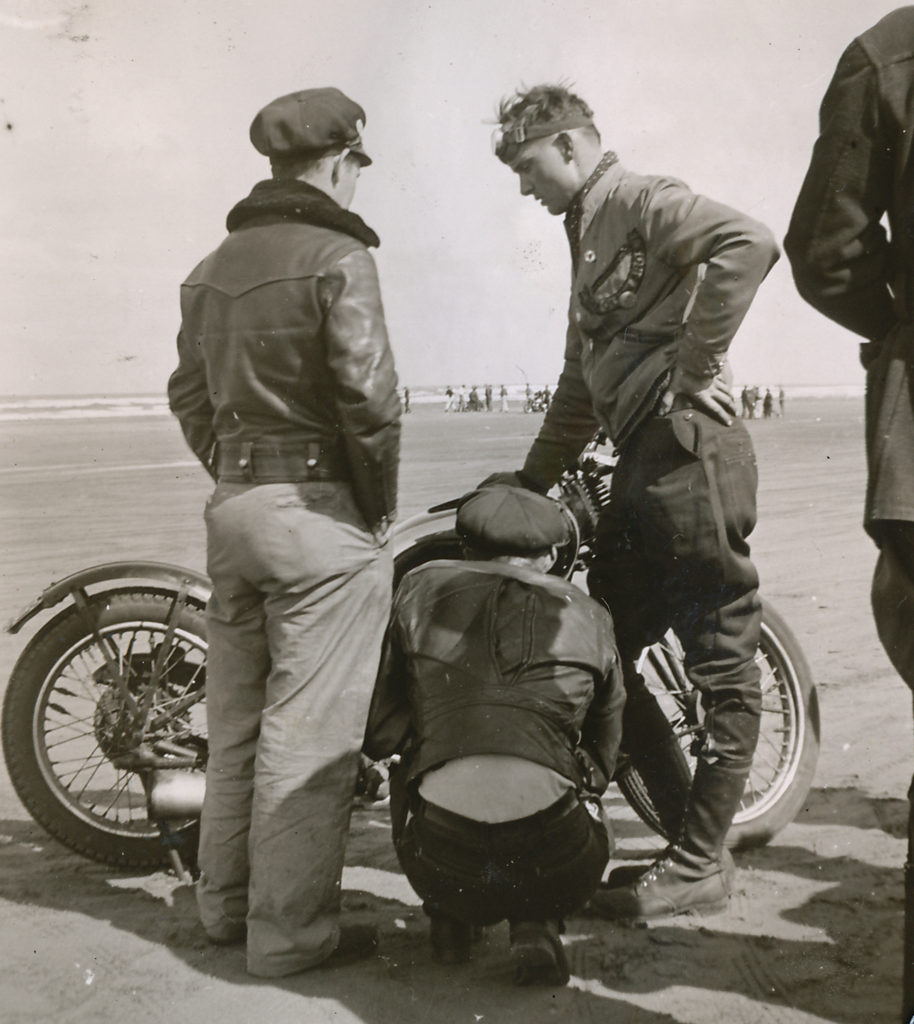

Many overseas servicemen maintaining Indian military motorcycles had been writing to Walker looking for assistance. Information they had at hand was nothing more than a parts list, and unfortunately for the English-speaking mechanics, the list was published in French. Walker asked Nicholson to write a technical series to help his Motor Cycling readers understand the internal intricacies of the Indian.

Nicholson’s first article, Servicing American-built Indian Machines Used in The British Army, was published Christmas Day, 1941. He followed that up in April 1942 with a two-part series with the rather ungainly title Servicing the 750cc Side-valve Model “45” Harley-Davidson: Details of a Complete Mileage Maintenance Schedule and Hints on Engine Overhauls Covering a Machine Used in Large Numbers by the American Forces.

Essentially self-published and printed by National Job Printers in Saskatoon, the First Edition was released in June 1942, with a run of 4,000 copies. Immediately successful, another 10,000 copies were printed in 1944. It cost $0.95 a copy to print, and the book retailed for $2.50. Circulars promoting the book were printed and sent out with every mail order, and ads ran in American motorcycle publications as well as Popular Mechanics. Cases of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics were sold wholesale and shipped to buyers including Clymer Motors in Los Angeles and Johnson Motors of Pasadena.

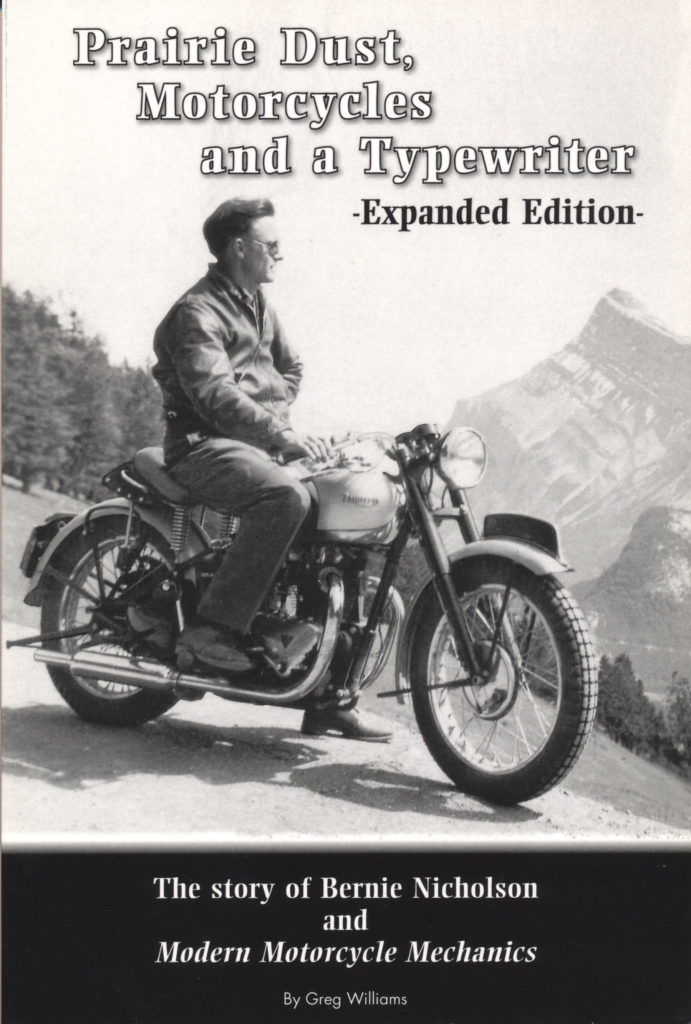

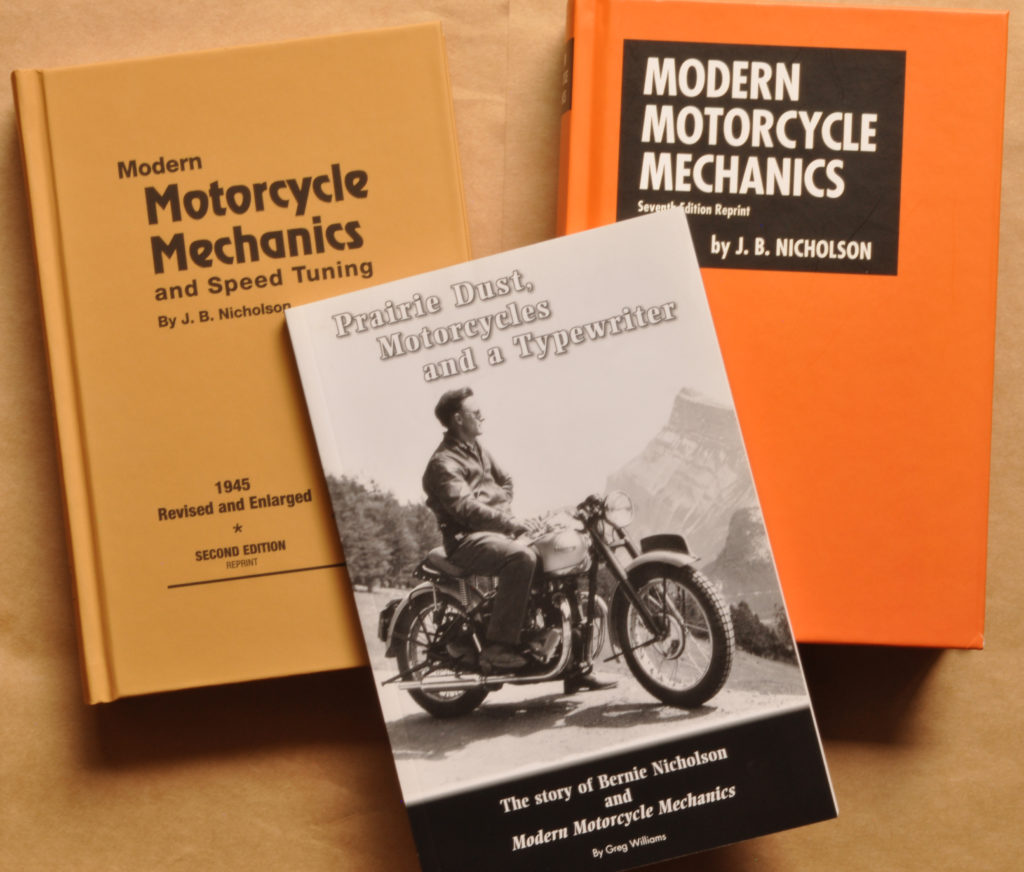

In the Foreword to the Second Edition, published in April 1945, Nicholson wrote: “The revised edition, as the original, has been prepared to render service to all associated with motorcycles, from the novice to the experienced rider and professional mechanic. Design, Operating, Maintenance Requirements and Servicing Procedure are amongst the items extensively covered. In scope and detail the new issue of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics surpasses any previous motorcycle publication.”

When I bought the ’71 Triumph Tiger it ran. Poorly. With the dog-eared Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles catalog in my hand and the words of both the seller and Dave’s dad, Ray, echoing in my mind, one of the first calls placed was to the shop. It was possible to make arrangements and meet Nicholson himself at the warehouse and purchase parts. On our first meeting, I chatted with Nicholson for several minutes and believe I purchased a set of Lucas points and other tune up parts. As the discussion wound down, Nicholson pulled out a copy of his 766-page Seventh Edition, handed it to me, and said I’d find it useful. If I had any questions, he added, I shouldn’t hesitate to call.

After I’d bought the Triumph, I discovered Billy’s News in downtown Calgary. On the stands were titles such as Walneck’s Classic Cycle Trader and British journals including The Classic MotorCycle and Classic Bike. Since 1992, I’d been purchasing and reading these magazines with interest, and thinking of Nicholson, pitched a story about the man and his book to The Classic Motor Cycle. They agreed to let me have a try.

And that brings this tale forward to 2009, when nine years after his death, I began working on a book about Nicholson – essentially a book about a man who wrote a book. In the process of publishing Prairie Dust, Motorcycles and a Typewriter, Nicholson’s son granted me the rights to reprint any of the seven editions of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics. I’ve done that, having enlisted Prairie-based institution Friesens in Manitoba to print and bind both the Second Edition and the Seventh Edition of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics. With a steady demand, another run of the Seventh Edition was reprinted late last year, in 2019.

Nicholson replied, “There was little done by others in the way of compiling a motorcycle manual, and I considered a manual a necessity. The manuals that may have come from a manufacturer were good, so far as they went. But we had machines going to remote corners of this country, with no repair facilities at hand. The manufacturer’s manuals missed a lot of things that could only be gained by personal experience.”

And that’s still the case, although now almost 50 years out of date and certainly no longer Modern, the information contained in Nicholson’s tome remains applicable to any disciple of the Internal Combustion Engine and the motorcycle.

I bought a 1973 Triumph Trident used in 1976 in Saskatoon. I had heard of Nicholson Brothers and called their business to see what they could offer for parts. At that time they had closed the showroom and were concentrating on parts sales. But you could make an appointment and go downtown to their building where Lawrence would let you in. Bernie was there also but he was not as approachable as Lawrence and stayed in the background. Fascinating people from another era. Gentlemen, to be sure, and they kind of looked at me a little strange as I was just a wild teenager with a big Triumph. But we talked a bit, I bought some items for the Triumph and I marveled at the inside of this building which was a time warp from the fifties and sixties. I know many people who bought brand new BSA’s from their showroom. Sad to see them leave Saskatoon. I talked with Lawrence occasionally, buying parts and just chatting. Very nice people. I don’t think most people in Saskatoon ever knew about the magic that was Nicholson Brothers on Second avenue.