But that didn’t prevent a mechanically inclined Larry from taking apart and fixing all of his friends’ motorcycles, go-karts and minibikes. By the time he was 15 and bought the BSA, the family dynamics were different, and his parents thought him responsible enough for a bike. Plus, there was doubt he’d ever get the B25 functional. Larry promptly diagnosed the source of the lower end noise; the oil pump drive gear was chipped. Finding a replacement gear, he says, is what introduced him to the world of British motorcycles and the people who dealt with them. “English motorcycle businesses tended to be enthusiast operated,” Larry explains, and adds, “I dealt a lot with Jim Hunter – and he was a curmudgeon, he’d just give you shit, saying things like, ‘What the hell are you doing here? What are you looking for and what’s the part number? You wouldn’t be here if you knew what you were doing.’”

Keen Velocette owners in the U.S. and Canada formally organized the Velocette Owners Club of North America (or VOCNA for short) in the early 1970s. Quite simply, these Velo-fellows wanted to share their mutual interest in the English marque that got its start in 1905 when German-born Johannes Gutgemann (who became John Taylor before formally changing his name to John Goodman) and partner William Gue built their first motorcycle, the Veloce. By 1913, Velocette was simply the model name of a two-stroke, 206cc machine and Veloce was proud of early engineering features such as the ‘footstarter’. Later, Velocette developed the first positive-stop foot shift gear change.

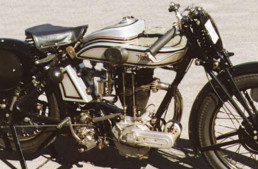

By now Larry was working as a civil engineer with the City of Los Angeles, and he had a small fleet of motorcycles. The KSS was taken apart and stashed into boxes, while Larry began looking for replacement parts. Long story short, though, “The KSS wasn’t my main focus, and it sat around in pieces for probably 20 years. The best part of the bike was — to the best of my knowledge — it’s the original frame, engine and transmission. But the worst part of it was, there wasn’t one part on it that wasn’t seriously worn out. For example, the crank was junk. The head was junk. “The gas and oil tank were good, but the fenders and stays were all bodged up and kind of a mess. I’d maybe work on something and make a little progress, until I decided that for the 2013 VOCNA rally in Volcano, California, I was going to get it together and use it there.”

Larry has attended most of these rallies. Not only does he complete the 1,000 miles of the event, he also has often ridden to remote rally locations. So, by his reckoning, he’s covered more than 100,000 miles aboard old Velocettes. For the Volcano rally in 2013, Larry had help from Mike and many other VOCNA members to finally get all the parts together for his KSS. Mike helped with the engine build, while Richard Denaple built and balanced the crankshaft. With zero miles on the odometer of the completed KSS, he trucked it to the start of the Volcano rally. “I’m not long on cosmetics,” Larry laughs. “I usually get a bike running and sorted, but don’t spend a lot of time fussing with the aesthetics. The KSS was in bare metal and some primer when it got to Volcano.”

Eventually, Larry ended up spraying the bare metal with a rattle can paint job, but there are no distinguishing Velocette decals or gold lines anywhere to be seen. This is the bike he’d ultimately ride on the Cross Country Chase, an event he knew nothing about until a chance encounter with Todd Cameron, son of legendary Velocette rider Dee Cameron and grandson of the legendary John Cameron, a founder member of the Boozefighters motorcycle club, one of the first SoCal 1%er clubs made famous by the 1953 film ‘The Wild One.’ “I didn’t really know Todd at all, but Mike (Jongblood) and I were at a vintage motorcycle gathering here in Huntington Beach when Todd showed up on a Velocette GTP (another of Velocette’s two-stroke models). We looked at it and asked him what he was going to do with it. That’s when he said he was going to ride it on the Cross Country Chase.”

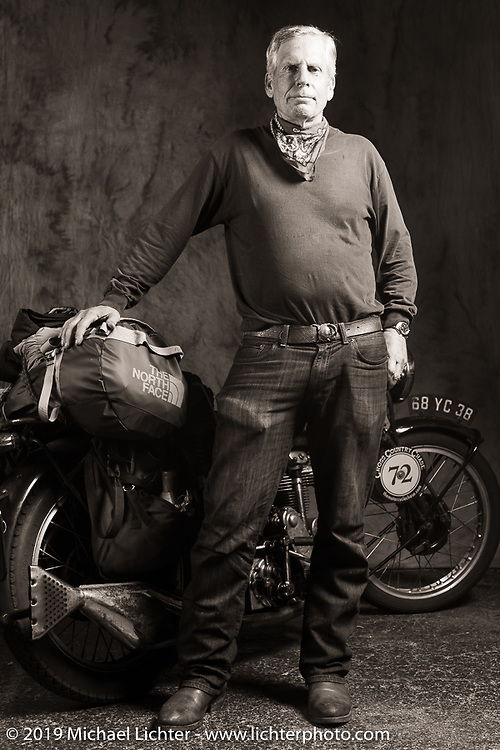

It was the first time Larry had heard of the Chase, but he quickly deduced the GTP was not in any shape to run a long distance. He and Mike talked to Todd for some time, humbly informing him of why they thought the 250cc GTP wouldn’t make the adventure. After that, Larry went home and looked up the Cross Country Chase. He learned the event, staged by the same people who host the Motorcycle Cannonball, was open to bikes built between 1930 and 1948. “I’d always been intrigued by the concept of the Cannonball but didn’t have any motorcycles that were built prior to 1929, one of that event’s criteria,” he says [actually, the rules vary on the Cannonball – from strictly 100+ year old bikes to as late at 1936, depending on the event – ed]. “On the Cannonball, you’re allowed a support team to follow you along, but on the Chase you are on your own. You need to carry everything you’ll need and keep up the maintenance and repairs – but you can ask a fellow competitor for help, or any casual volunteers.”

Larry put the freshened 348cc engine back in the KSS, adjusted chains and tightened all fasteners before adding 150 test miles to the bike. Deeming it ready to go, final modifications included the installation of a modern programmable speedometer and a route sheet holder. Canvas saddlebags bought for $26 from Amazon went over the rear fender, where he stashed oil, an assortment of fasteners, a good assembly of tools, and extra cables and a complete spare magneto. He didn’t need much of what he packed, but Todd utilized some of it.

Todd’s unrestored BSA arrived just nine days before the pair’s departure date. In that limited window of opportunity, Todd did his best to familiarize himself with a machine he knew nothing about. Together, they loaded the Velocette and the BSA on the trailer behind Todd’s Sprinter RV, drove to Sault Ste. Marie and started off on the Chase. Now, the Chase is a competitive event testing endurance (of both motorcycle and rider), speed (completing the 250 to 350-mile stages in a timely manner), navigation (following the prescribed route), and general knowledge. Yes, there was a test – and the results counted toward an entrant’s final score.

On the backroads of eight states covered in 10 days, Larry’s only breakdown was a flat rear tire; an easy fix he completed in the parking lot of the Harley-Davidson Museum in Milwaukee. Todd’s BSA consumed a quart of oil every 100 miles and could not be ridden faster than 55mph, normal travel speed was less than 45mph. Larry says they did not stop much during each day’s ride. Todd managed with dogged determination, some advice from others (for example, retarding the magneto timing so the 493cc Sloper engine would carry him up hills) and some parts and pieces from Larry to become the unlikely hero of the Chase. He won the Class I award, and earned himself a Legend award, a Jeff Decker custom bronze, special number plates if he decides to partake in another Chase, and $7,500.

Taking pleasure in his journey was certainly due in large part to the careful preparation of the KSS engine by Mike Jongblood, whom everyone whispers has some kind of voodoo magic with Velo motors. Success in the ride was also testament to Larry’s wrenching skills, learned decades ago and beginning with nothing more than patience and perseverance and four simple hand tools.

Larry adds, “There is something to be said for a level of technology which allows an enthusiastic kid with few tools and eve less knowledge to turn a pile of parts into a functioning motorcycle. A machine which, if it falters, there is a fair chance you can fix it with what’s in your toolbox and what you find on the side of the road,” and of his latest adventure, he concludes, “The Cross Country Chase is an event that allows vintage motorcycle enthusiasts to use their machines in the manner the makers intended. It also proves vintage vehicles can be viable long-distance transportation. In my opinion, there are few better ways to travel.”\[Many thanks to Michael Lichter for allowing use of his amazing Chase photos. Michael has photographed every Cannonball event since 2010: see all this photos here.]

Related Posts

November 18, 2018

The Vintagent Selects: 2018 Motorcycle Cannonball

The world's toughest vintage motorcycle…