any trip with an old motorcycle takes twice as long because of the conversation

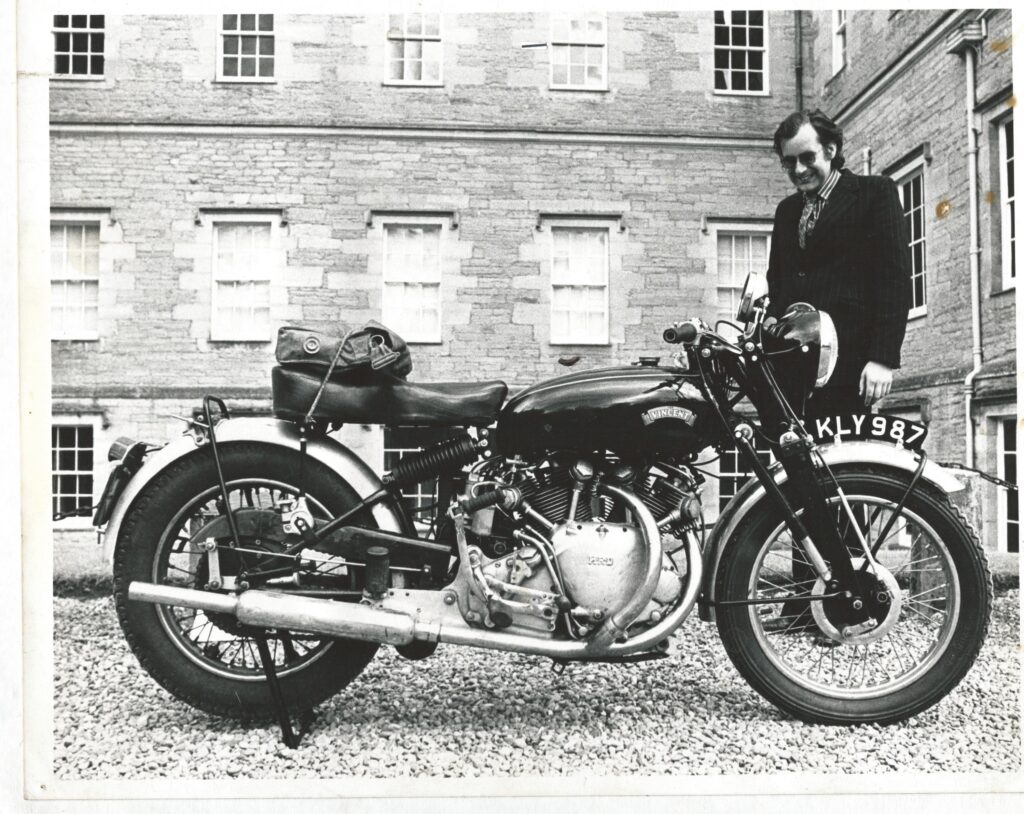

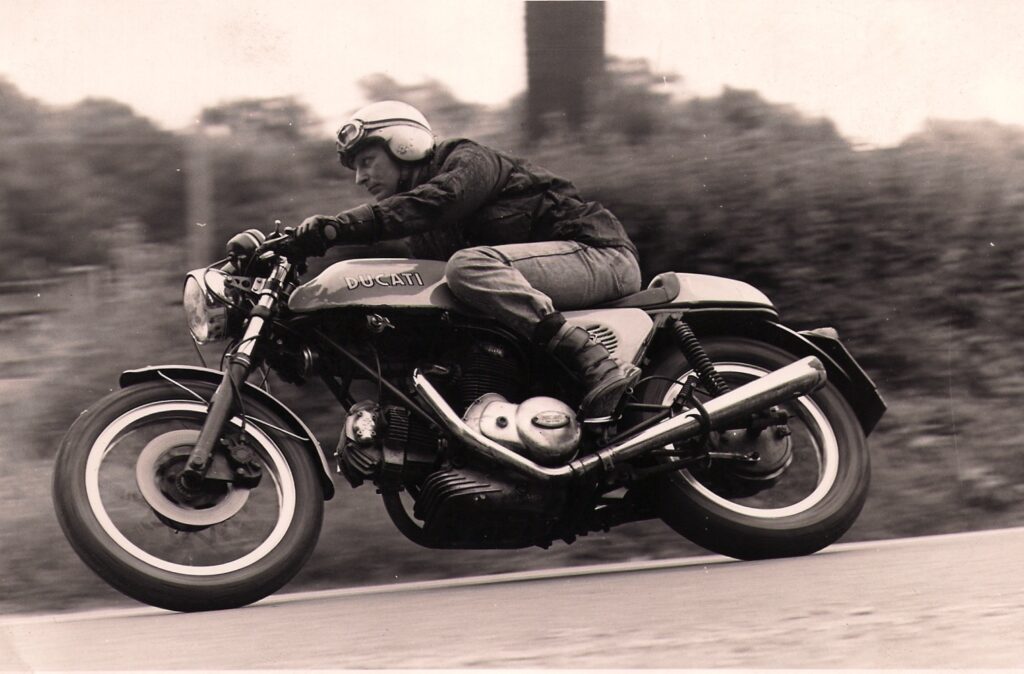

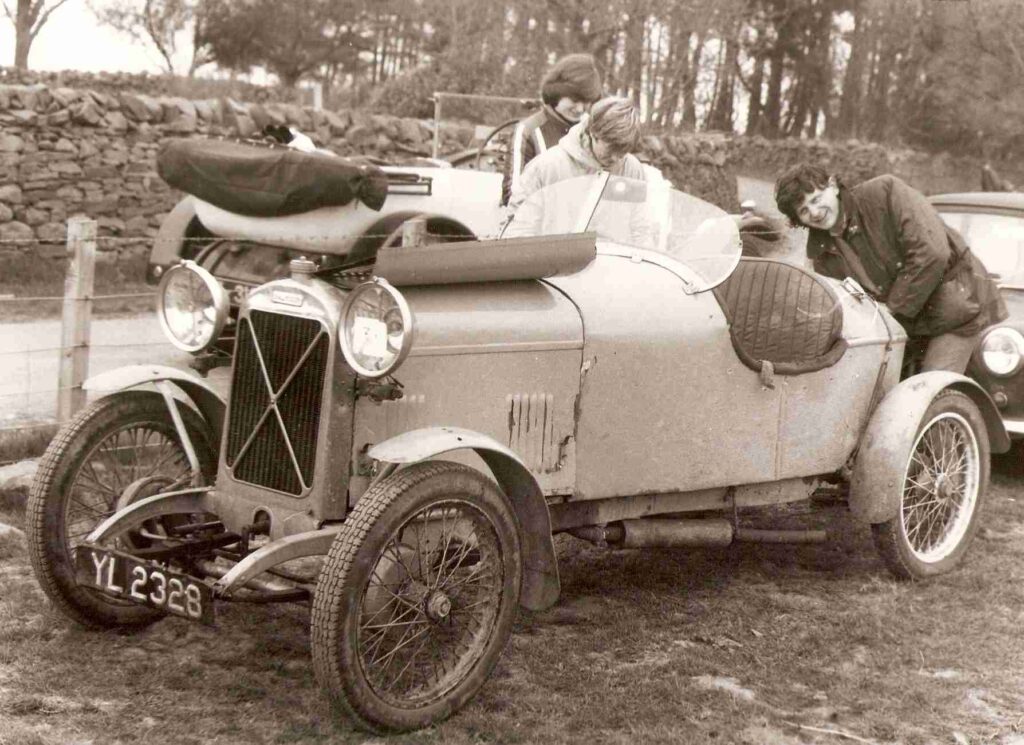

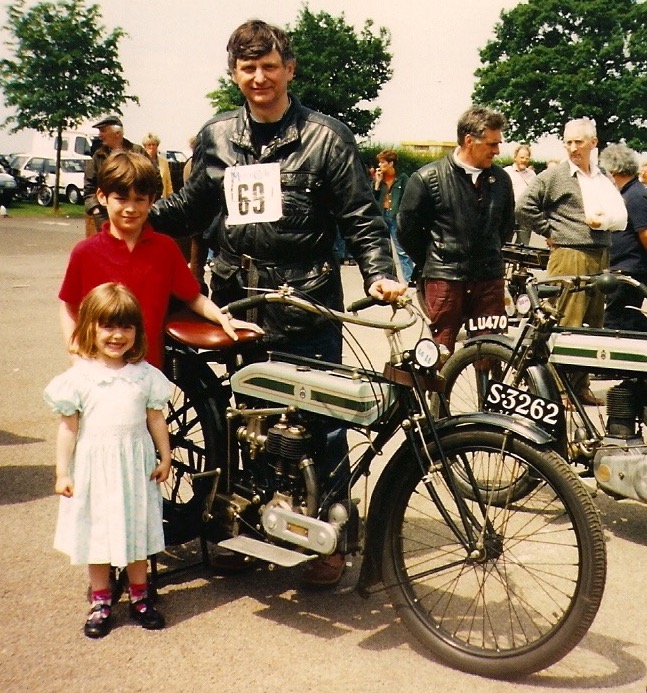

Does Andrew have a favourite motorcycle? He says, “When I was in my 20s, in Edinburgh, a dear friend, biker and engineer said, ‘if you’re going to ride a crazy thing like a Vincent that’s always going to go wrong, you need a sensible motorcycle too — so buy my 1960 BMW R60’. I did. It was lovely, but I didn’t realize, back then, just how good it was. Fiona and I rode out to dinner in the country for our first date, and it didn’t even give a tiny slip although the snow was starting to fall on the way back. It’s partly because the power is so smooth, and the controls are so progressive. Then, after owning or riding dozens of motorcycles, I found a 1956 BMW R50, so I’ve almost gone back to what I had in 1970. It’s an Earles fork model R50, maybe a bit less power than my R60 but the 500s rev amazingly well for a pushrod motor, and if you have the right solo gearbox, and the solo rear bevel ratio, the gears are wonderfully long, and the bike just flows. I use it a lot and I think it is pretty perfect — probably the best motorcycle in the world when it was made.” He waxes philosophical: “I love to be in some little country village with a coffee shop or pub, with the bike outside, thinking that such a simple and slim, economical and refined piece of engineering has brought me there. I’m more of a rider and less of a tinkerer now. The important part of it is people. In the car, or boat, or motorcycle world I love talking to the enthusiasts and people who can do work that I can’t do. My family say that any trip to do with these things will take twice as long because of the conversation.”

For the curious, a list of Andrew Nahum’s published works:

James Watt and the Power of Steam. 1981 (for children)

The Rotary Aero Engine. Science Museum, 1987/1999

Flying Machine, 1990 (for children)

The Rolls-Royce Crecy. (co-author), Rolls Royce Heritage Trust, 1994

Alec Issigonis and the Mini, 2007

The Making of the Modern World, (executive editor and contributor), John Murray/Science Museum, 1997

Cold War and Hot Science; Applied research in Britain’s Defence Laboratories. (Contributor), Science Museum, 1997

Tackling Transportation. (Chapter on the British exploitation of German defence science following World War 2). Science Museum, 2003

Frank Whittle; Invention of the Jet. 2005, Totem Books

Fifty Cars that Changed the World. Design Museum / Conran Octopus, 2009

Ferrari: Under the Skin. (Editor and contributor), Phaidon / Design Museum, 2017

Moving to Mars: Design for the Red Planet. (Contributor) Phaidon / Design Museum, 2019

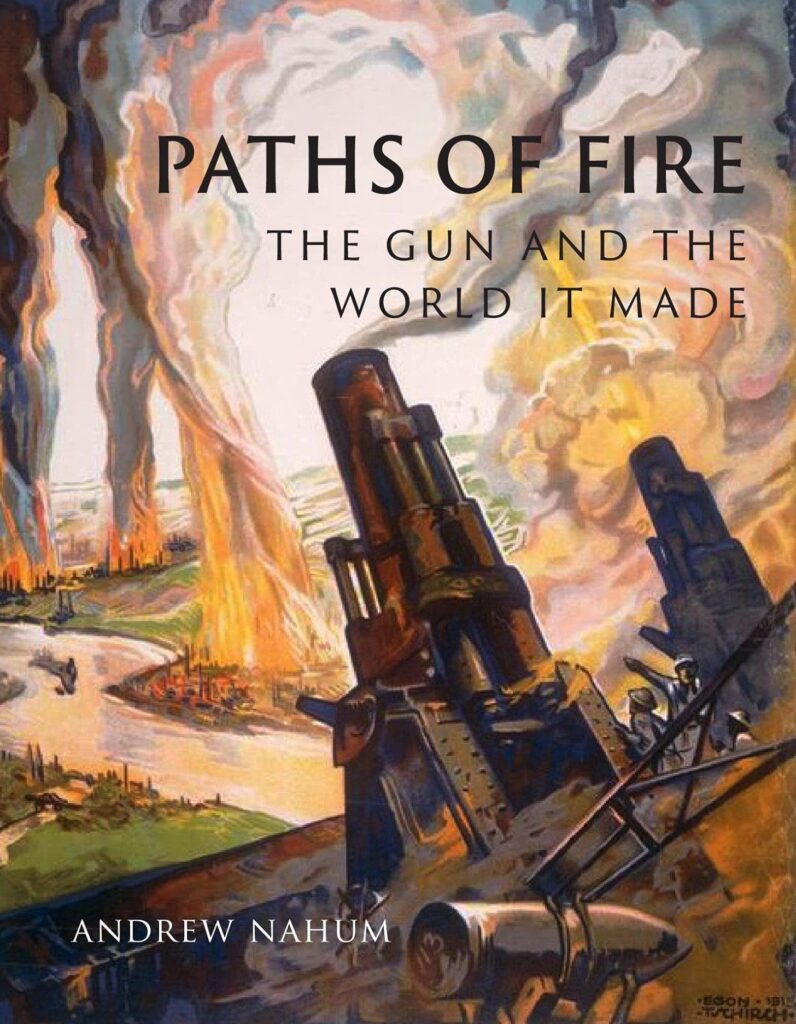

Paths of Fire: the Gun and the World it Made. Reaktion Books, 2021