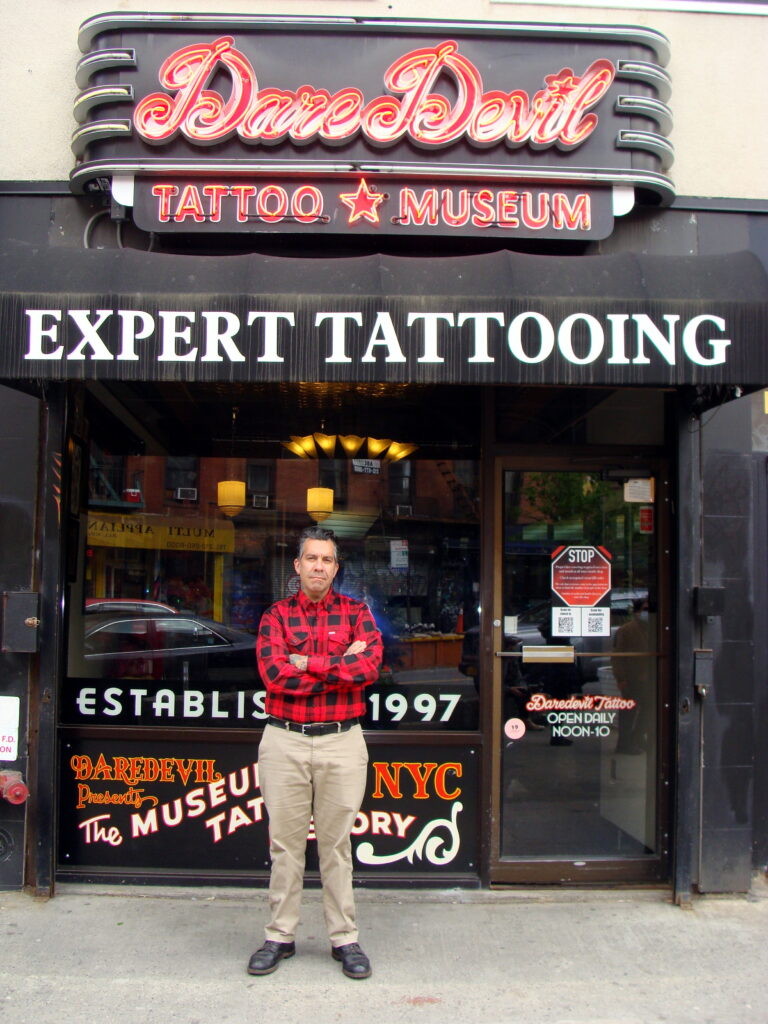

Diego Mannino is a tattoo artist and vintage motorcycle enthusiast, who explains both the LA scene he grew up in (and has returned to), versus a thriving NYC motorcycle scene he adopted in the 1990s. The following is his statement on those scenes: who inspired him, who he worked with, and how these wildly different cultures compare:

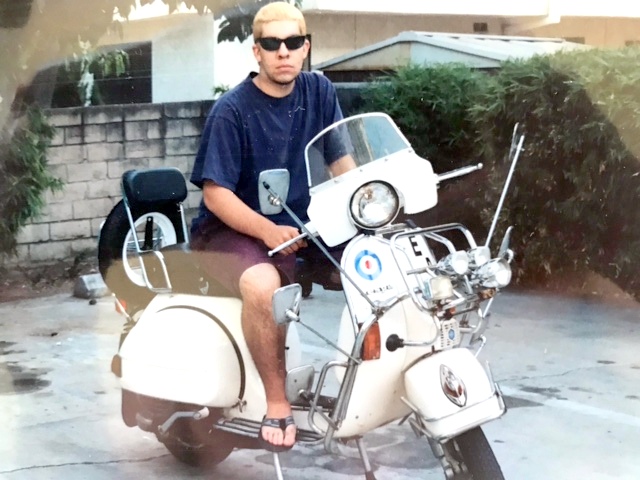

“I was raised in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles, Alhambra and Pasadena mostly. There were always lowriders and hotrods driving down Valley Blvd, and once in a while I’d see some local motorcycle clubs riding by in packs. I remember wanting to buy a leather motorcycle jacket in junior high school because of how tough those bikers looked. Ha ha! I was always into drawing comics and fantasy art. My father used to take me to the Los Angeles Science Fiction and Comic Book Convention. I would sit for hours watching the comic artists draw and chat with us kids. I went to the Pasadena Art Center College of Design for a few semesters before moving up to San Francisco in 1994. I finished up my degree in Illustration at California College of Arts and Crafts around 2003 and immediately started to learn to tattoo the following year.

Riding in San Francisco was challenging because of the hills and traffic. To this day it’s still the most fun I’ve had riding in a city. Once in a while I would take it over the Golden Gate Bridge to ride through Muir Woods. Some of my favorite memorable rides in the Bay Area was the Rockers vs the Mods ride that went in a big circle around San Francisco. Half way through the ride all the British bikes met up with the old Vespas and Lambrettas and we rode together and pretended to hate each other! It was an homage to the rock opera Quadrophenia performed by The Who. [The two groups would meet head-on in the Stockton St tunnel and halt all traffic while performing stunts. – Ed]

Said it before … and I’ll say it again .. with a vengeance !!!

With very few exceptions …

NYC ( and the last coast in general ) HAS style ..

Whereas LA ( and CA ) … copies and commodifies … calling it ‘ style … when in reality .. its just commerce