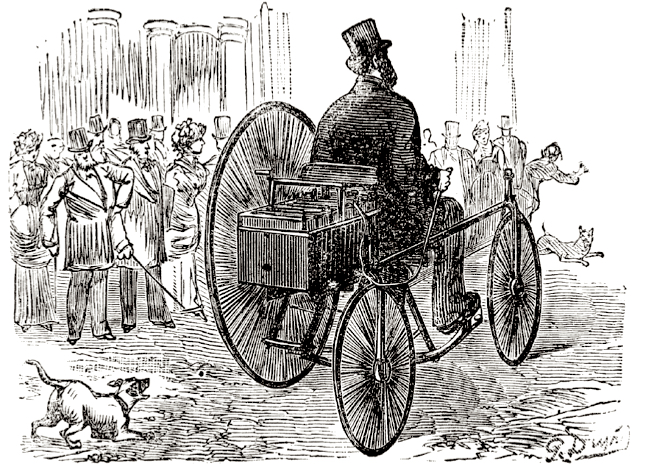

The concept of ‘personal electric mobility’ has been around for almost 150 years. In fact, the very first patent for a motorcycle (1871) specified an electric motor, from an era when both motors and the batteries to power them had to be built by hand, and were hardly reliable. Give a read to our History of Electric Motorcycles article for some background. While the legacy of electric vehicles in mass transport and industrial use is a century of success (think electric buses, trollies, trains, forklifts, etc), the mass-production of personal electric vehicles has a far spottier and more problematic story. Only in the past ten years has the electric vehicle become truly popular for personal use, but that doesn’t mean clever folks haven’t tried.

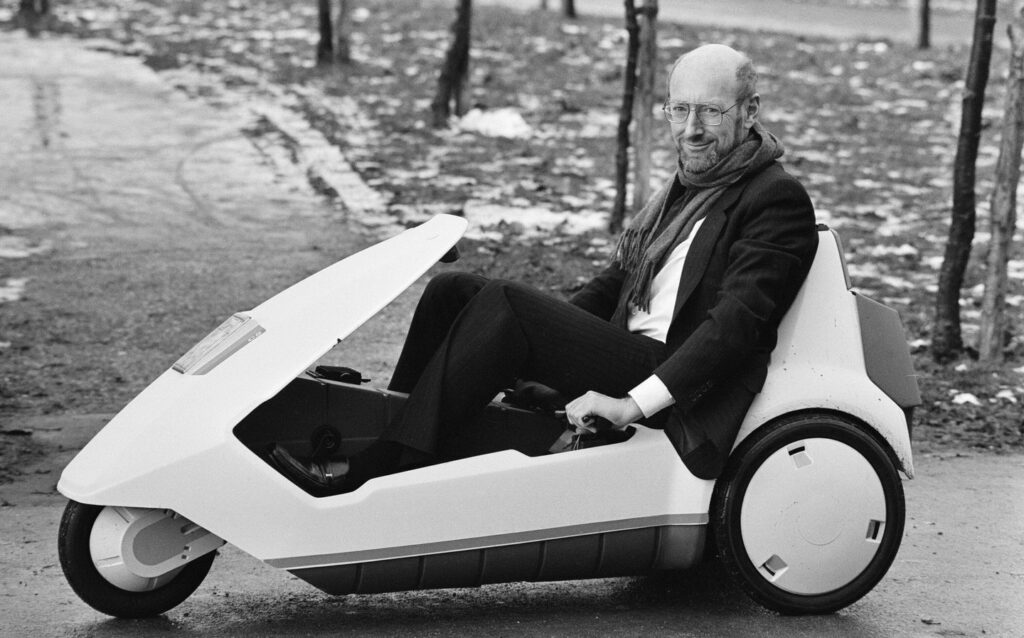

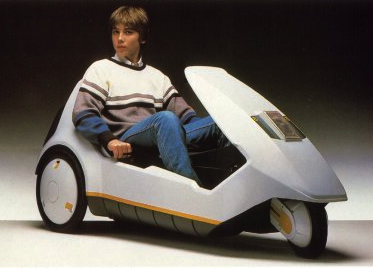

The Sinclair C5 was assembled from major components by different contractors: the plastic body by Linpac, the chassis and gearbox by Lotus, a Phillips motor, Oldham lead-acid battery, etc. A deal was negotiated with a Hoover washing machine facility in Wales to assemble and test the C5, with production slated for 200,000 units/year. Before the January 1985 launch of the C5, 2500 had already been built to deal with anticipated demand.

The Sinclair C5 was launched at a lavish press reception at Alexandra Palace, featuring Stirling Moss. As it was cold, most of the C5s refused to run properly, and ran out of battery very quickly. Press testers taking the C5 out on the road were terrified when they encountered trucks, which could not see them and belched exhaust directly in their faces. There was no weather protection, so testers froze and got wet. In short, the launch was a disaster. And the bad news kept coming, with magazines and newspapers expressing concern about the lack of any safety equipment, the invisibility of the C5 to many drivers, and the lack of training/licensing/helmet requirement for young riders. The 250W electric motor was insufficient for any hill, and the battery ran flat between 6-12 miles, far below the 30-mile claimed range.

About the nicest kindest thing one could say about this abomination of style and technology is …

.. its pathetic … beyond pathetic actually . . So … perhaps … drank way too much of the KoolAide ( or delved into Bear Owsley’s stash seeing as he was living there by then ) delusional .

Hmmmm…… pink elephants and polka dotted kangaroos every where you look …

” What a Long Strange Trip ” ….. it still is …. 😎