1924 Model 5 vs. 1925 Model 6 Longstroke Sports

[Mar 24, 2008]

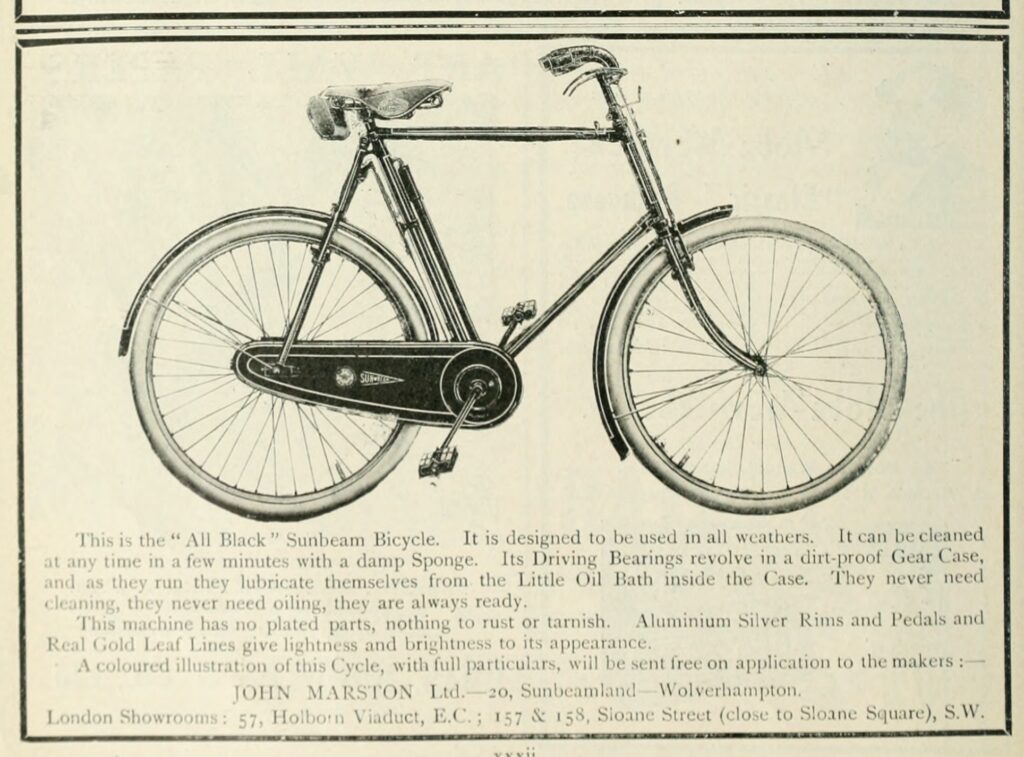

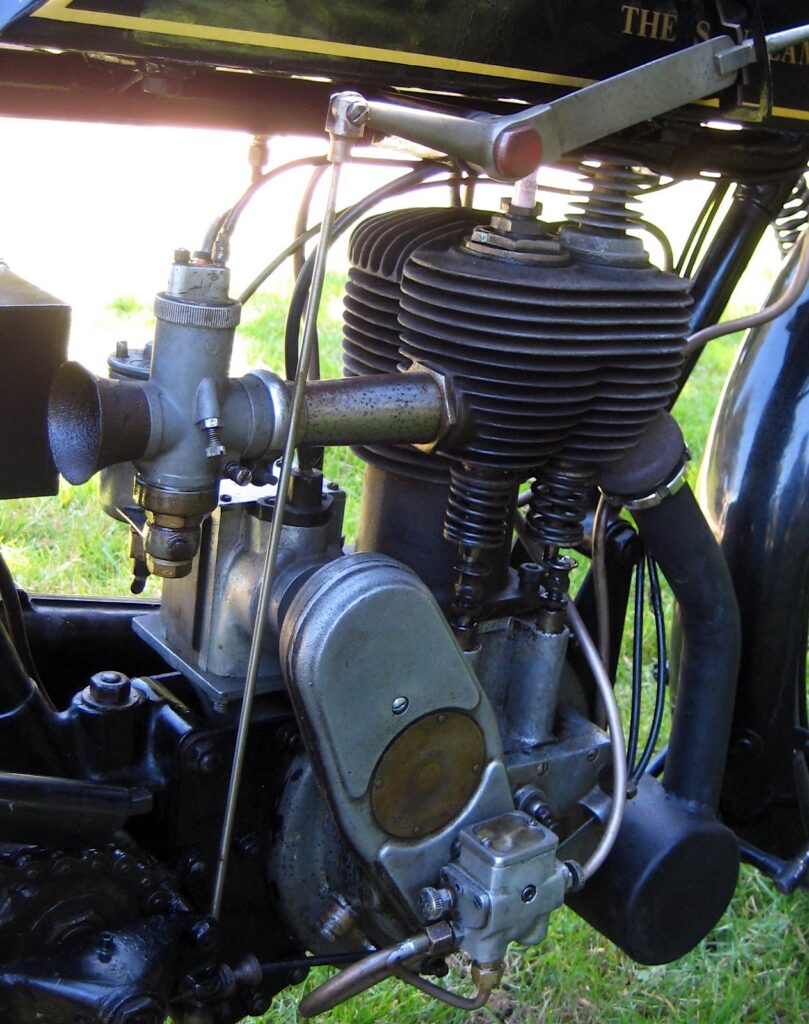

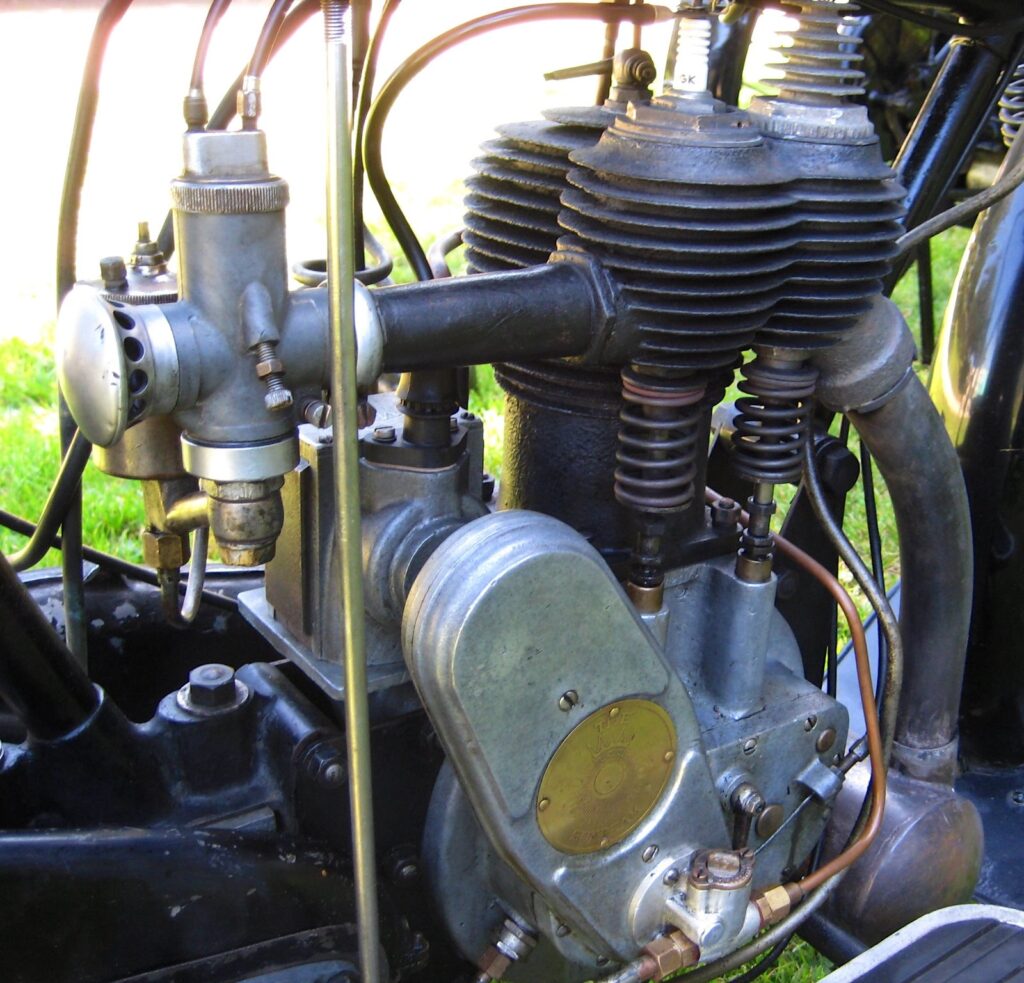

Sunbeam motorcycles were built by John Marston Ltd. starting in 1912 in Wolverhampton, England, as an outgrowth of Marston’s highly successful Sunbeam bicycle business. Marston began his career in 1851, manufacturing ‘japanware’; glossy enameled home accessories and furniture with a luxurious black or red finish and gold leaf accents, modeled after traditional Japanese lacquer ware. Japanware was all the rage in the late 1800s, and in 1887 Marston took the advice of his wife Helen and expanded his business into the booming bicycle trade. With over 30 years of experience in top quality paint and gold leaf, Marston’s Sunbeam bicycles were renowned for the superb black and gold finish, and for the patented pressed-metal ‘Little Oil Bath’ chaincase that kept the rider’s trousers clean. Sunbeam bicycles were expensive, but designed to last a lifetime, and many a centegenarian+ Sunbeam bicycle still retains its original finish in perfect condition.

What are they like to ride?

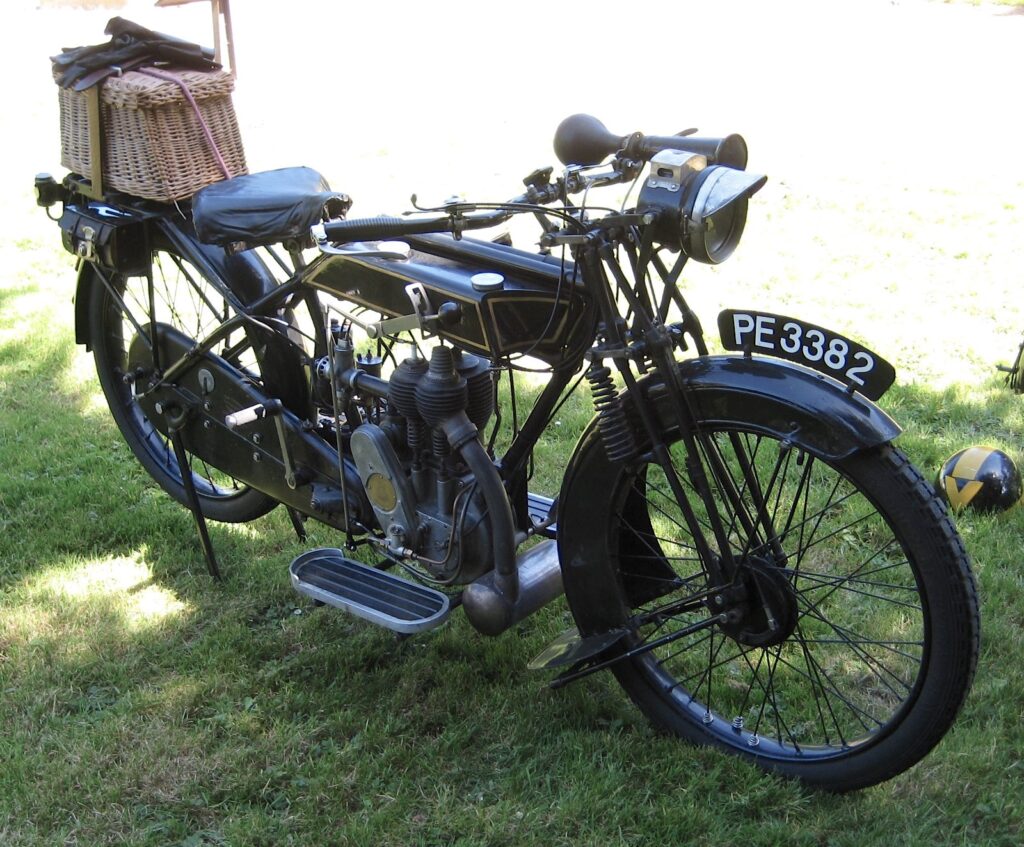

Since my 1925 Sunbeam Model 6 Longstroke arrived two weeks ago (March 2008), I’ve been curious to compare its character to that of James Johnson’s 1924 Model 5 touring model. They’re both sidevalvers from the mid-20’s, with very similar running gear and mechanical configurations, from the same esteemed manufacturer; how different could they be?

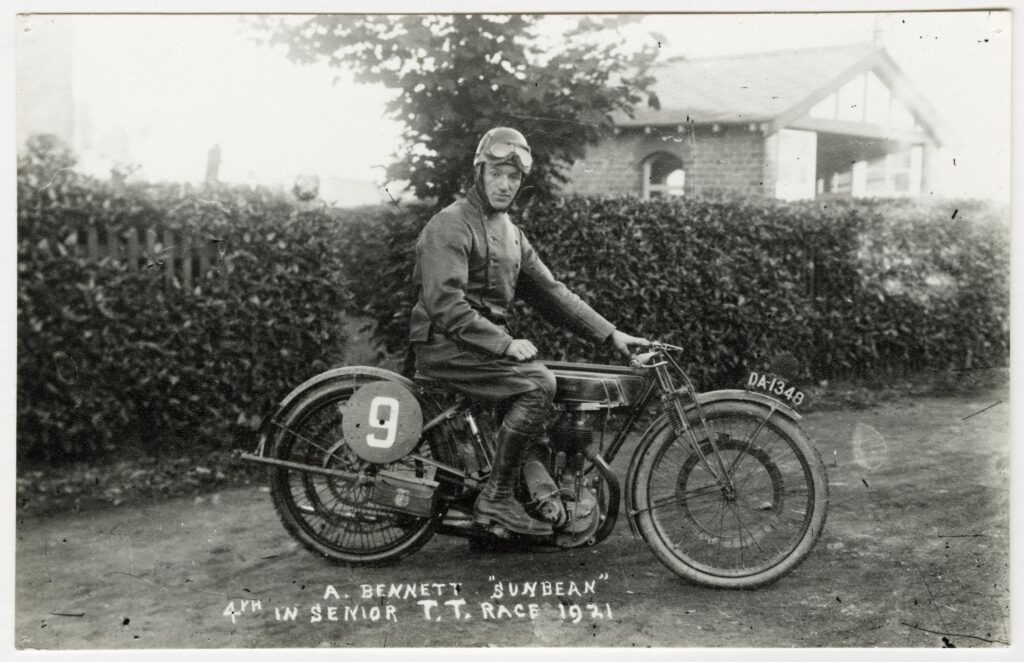

The Longstroke was developed from Alec Bennett’s 1922 TT-winning (at 58.31mph) machine, and was initially known as the ‘Model 6’. The ‘Longstroke’ name was added for 1925, to what would have been the ‘Sports’ model in that year, but was called the ‘TT Replica’ in 1923. How quickly things changed in those critical years between 1923-25, where the Longstroke dropped in esteem from TT Replica to a ‘Sports’ model in just 2 years. That’s because Sunbeam added a new overhead-valve engine to its line in 1924, the Model 9 (and its variants), which sounded the death knell to the sidevalve as a racing machine.

James purchased his ’24 Model 5 from British Only Austria about two years ago, and has spent considerable time in his workshop, making the 84-year old Sunbeam perfectly reliable. Now he feels confident in its mechanical soundness, and several long rides (including one 800 miler!) have borne out his conviction that his Sunbeam can be ridden as the maker intended.

Hmmm …. so lets see now ….. an ancient frail fragile barely a step above a motorized bicycle Brit bike …. that on a good day might be good for getting you there …. but definitely will not get you back ….. compared to another .

Hmmmm

I mean … as a riding article on either or even a feature article …. certainly …. but as a bloody comparison test ??????

What is the point good sir ? Truly … what is the point indeed …. ” Much ado about nothing ” pretty much sums it up … unfortunately .

😎

You know, you were right, so I added some historical context before the article written in 2008 – the ancient days of The Vintagent! There’s plenty to be interested in with Vintage bikes, but their charm is lost on many…

Rest in peace James. You left our circle of San Francisco old ‘bike enthusiasts far too soon.

So true, Chris. I’ve yet to repost my ‘Death of a Vintagent’ article, but will soon. Somehow it’s harder to take now than when it happened. Memento Mori…