“Time seemed stationary, yet the painful pressure of time was constantly felt.”

Hubert Selby Jr. The Room, 1971

“The true New Yorker secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding.”

John Updike. The New Yorker, 1976

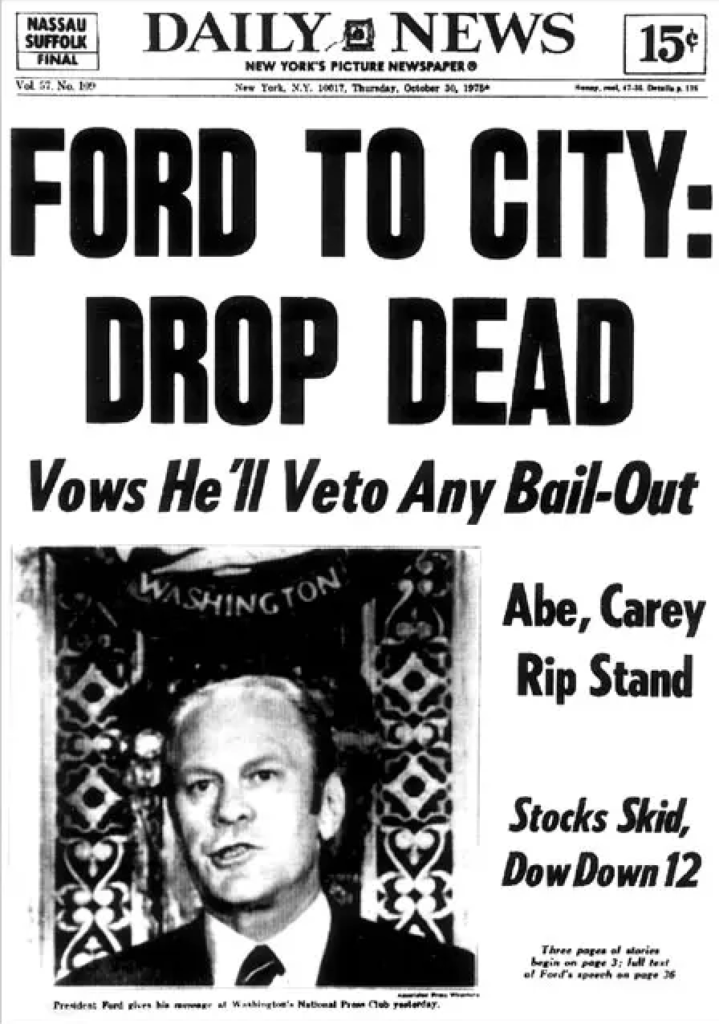

The 1970’s in New York City were a dangerous, dystopic, but also a liberating time, when a beat-up, two-bedroom East Village apartment was one hundred dollars a month. A glass of Rheingold Beer in a Bowery bar was twenty-five cents (and came with lively bartender conversation). Photographer Langdon Clay was born in New York City in 1949, and at twenty-five, after schooling in New Hampshire and Boston, returned to New York City – more specifically lower Manhattan in 1971. In New England he had experimented with making 8mm movies and began to develop his eye. A friend suggested a few photographers he should look at: Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He learned about the camera’s capacity for documentation.

Langdon Clay (LC): I was born at St. Vincent’s Hospital. I don’t think it’s there any more…it’s some condo building now. I lived in Princeton, NJ in the ‘50s and then we moved to Vermont. I went to some fancy boarding school. In school we were making 8mm movies without sound. But scheduling got complicated. On a trip to New York I went to Olden Camera at 34th Street and bought a Pentax. I was familiar with cameras to a degree. I was familiar with the notion of recording things. I did not migrate to still cameras as a complete neophyte.

I was reading Camera Magazine and seeing all the European people, but wanted to get away from it. I didn’t want to be an imitation of it. I wanted to do something that was mine. I understood the difference between an impressionist and expressionist perspective. I wanted to record. If photography is one big tree, one branch goes off and it’s realistic and it’s recording things and the other is expressing things from an artistic point of view using light sensitive material. For me, using the camera is to record. That’s always how I’ve felt about it.

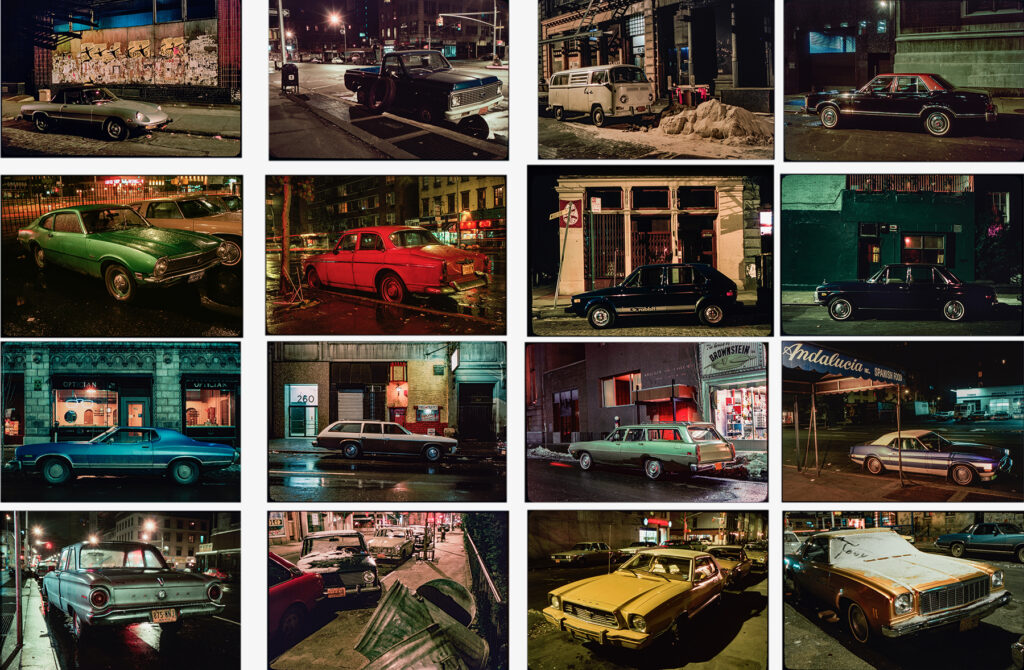

LC: You know what they say… If you are a writer, write about what you know. So if you are a photographer follow where you are. You can always find something. To photograph something which I had done for a long time in Black and White is one thing, and then to turn it into a project where you are going out a couple nights a week kind of hunting, is kind of another level. So it brings you to the whole question in photography of how do images and sequences, how does the ordering, compound the meaning and questions like that. Photographing the cars was the first time I had put together that I was actually kind of on to something not so random.

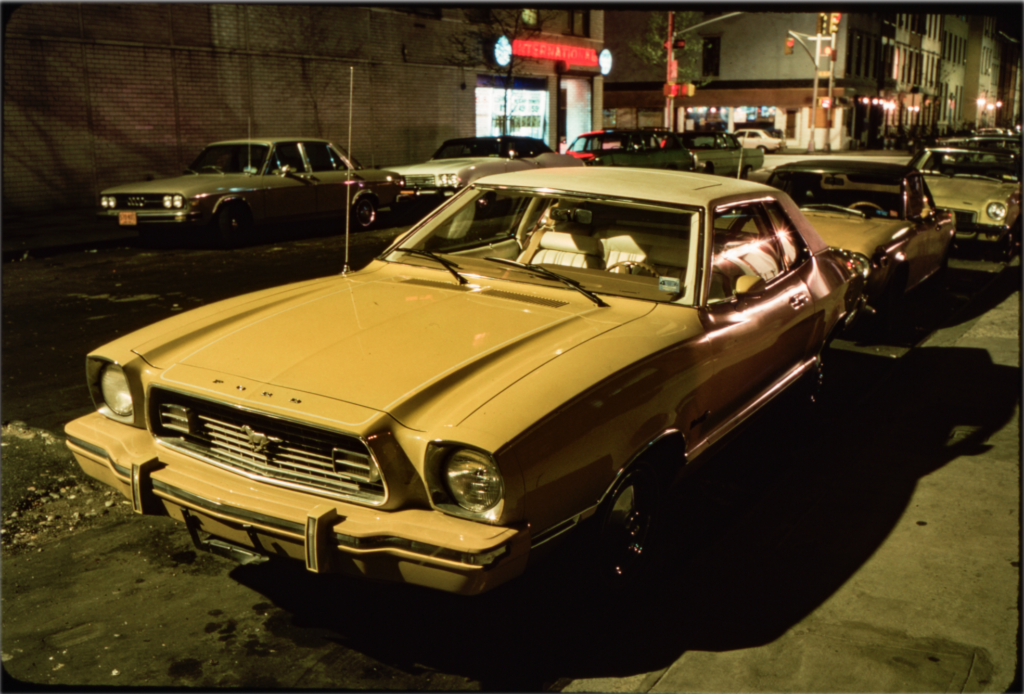

LC: I knew they wouldn’t always look like that. In fact, I took those photos in ‘74, ‘75, ‘76 and we’d already had the gas crisis. Several things had happened with cars: they had to get smaller. And the other thing that had changed is the design engineers had come up with the wind tunnel and probably some early computers. Instead of being designed by a sculptor, who would make a life sized model of what the car would look like with no regard for the cost of gas, the gas crisis [meant] the design of cars was going to change. And the cars I was photographing on the street were still from four, five or eight years earlier. And the ones I picked were the cool designs but by they were all rusting out and banged up. I knew to that degree, since things were changing, that those cars and my photographs would be a little bit of history. In ‘79 I did something about 42nd Street and that really was done for history. The newspapers were full of stories about the need to renovate (read clean up) Times Square and I thought, ‘fuck I better do something about that’, to make a record.

MM: You said about the older car designers, “At the time designers were crazy. They were real artists. They could do anything they wanted but above all they were drawn by hand.” So at the time did the cars seem important and worth documenting? And why at night?

The French were early on the weirdness of design. The Nordic types and Germanic ones had a different approach to cars. Most of their designs were better I would say. That’s just me. Now as far as photographing them, I don’t have much interest now. The only ones I like around where I live (down South) are those same cars from the ‘70s.

MM: At what point do you think as you are walking around and noticing these cars, like that Lancer, your personal sensibility… You realize you have stumbled onto something. It’s dark, the streets are not congested. You were using existing light of the Sodium Vapor street lights.

LC: During the 1970s Mercury Vapor was used to illuminate places like basketball courts at night. Then to save money, the city switched to Sodium Vapor which is much warmer and more golden light and it works very well with Kodachrome. I tested different films and that one worked the best. The problem for the city is that it’s cheaper to use that light but the trees keep growing at night. So then you’ve got to get the tree people in to trim the trees. So there’s always something. I tested all that because I was just learning about color and switching from Black and White to color. I tested different color films but the best one was Kodachrome. I am glad I picked it. There is a permanence and some weird richness in Kodachrome.

LC: I was hoping to find the right technology for the aesthetic. I could tell, I got to a point where out of a roll of film, I could use everything on it. The pictures found me at a certain point. So I knew when I had a match between a car and a background.

MM: You said, “To see what it is, to record clearly and pass it on faithfully to your children and their children or inquiring Martians or leave it to posterity. It became kind of a calling. I had to see it for myself.” Was this some kind of a calling?

LC: Yeah, it was kind of, and the Village along with those cars had a similar effect to Paris. The scale of the West Village or Hoboken which then was an easy run under the World Trade Center on the Path train. And it wasn’t scary to be in those places. The East Village had a different feel from the West Village. So, I was living on 28th street and the Village was a walk, I took a couple in Murry Hill, the highest I got was 59th street or something. If there was a calling it was to my own neighborhood. I had a sense of place. I didn’t have a lot of money. I’d paint apartments. I could do that for a couple weeks and then take two weeks off and go to the movies with my friends. Hang out and play cards.

MM: Did you have any precondition about what kind of car you wanted to photograph? You are walking down the street and you see an old banged up Studebaker and you’d say to yourself, “That’s a good one. I better take that one.”

LC: Yeah, I passed by a lot. And of course I went past the same streets and same buildings over and over and over again. But the cars changed, so that’s why I went back again and again, because something might turn up that would work. In the beginning I did even wider sort of streetscapes where there might be two or even three cars, like a red car and a green car right next to each other. I pretty quickly got down to just one car and one background as an aesthetic approach. At the time I was learning more about Renaissance styles.

When I first showed these photos in Paris in ‘76, the French thought I had just moved the cars. They thought it was an arrangement thing. But that would be pretty theatrical and I didn’t have either the money or the imagination to do it. Nothing was particularly planned other than I would roam the streets.

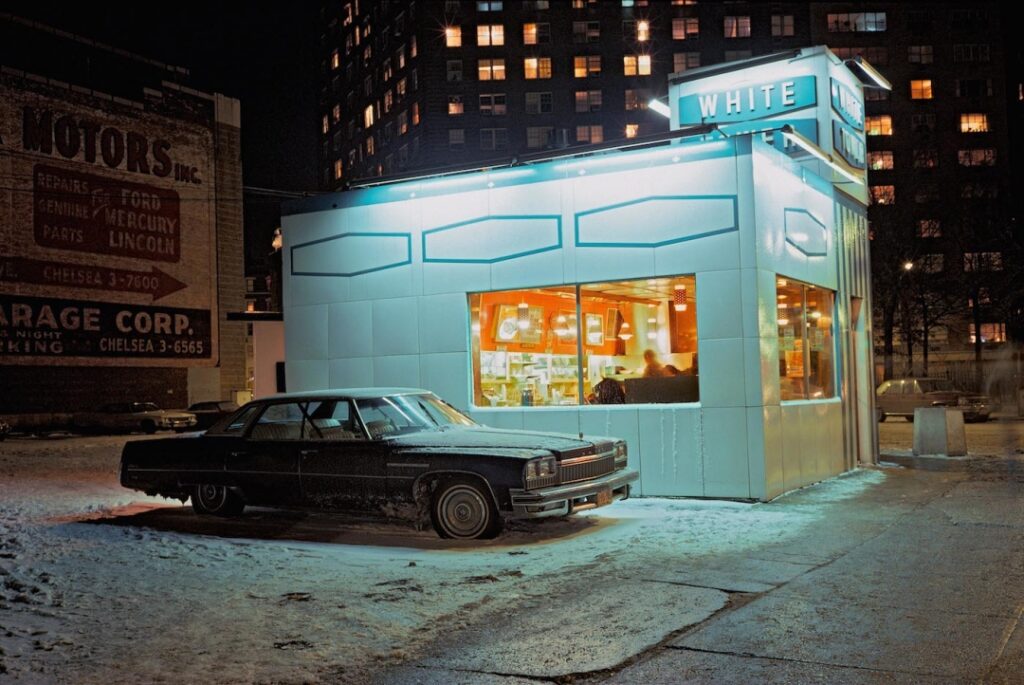

LC: Yeah, but actually, I don’t care all that much about cars. I cared about the whole picture. You know, for photographers when near, middle and far line up in this way, you want to comment on other things in the picture. Sort of like a poem I guess. You need something happening where the parts of the picture are talking to each other in a way. There were photographers like Brassai who photographed Paris at night who was an inspiration. You can go further back into French painting- Georges de La Tour did a bunch of night scenes with candle light, with gloomy shadows. And there was Edward Hopper. I don’t know why I gravitated to that. Another thing was, not so many people were photographing at night at the time. Now with digital, it’s much easier; the lighting works better. You don’t need all the filters, etc. And now, you can tweak them in the computer.

For most of my time in New York at least until the early ‘80s I didn’t even own a car. Even back then, to keep a car in a parking lot cost as much as having an apartment. Before, when I lived in Vermont everyone had VW bugs. I was a little partial to them because I knew if you got stuck in a snow bank, it only takes two people to lift them out.

LC: Well, you know what it means. From living in that city in particular. Back then, you weren’t always safe. There were three guys coming at you down the block and you’d cross to the other side to save yourself a bunch of grief.

Photographing at night in that light was a different thing. Particularly during the summer- the humidity and the night are protective layers, so you don’t have to worry about the sky. You are focused to the street level. Basically, photographing the cars was very objective. I was also very keen to maximize any detail in any given image. The issue of recording evidence. Yes, there are the cars but there is also all the other information in the frame. For me that’s what’s important. In one-hundred years that’s what I hope people will get out of these things. I guess some of what is in the background of the photos is still there but many of those places are no longer there.

LC: I guess a lot of it is still there but they have painted over the buildings. Some of the buildings are gone. I was in the city recently and went looking for some of the places where I took the photos; like the White Tower hamburger place I photographed with a car in the snow… That’s gone. There is a big apartment building there now.

MM: You as a young man, you were twenty-five, you were impressed with this city, you had a camera- you could have taken pictures of so many different things. You could have taken pictures of store fronts.

LC: Atget did this in Paris. He wasn’t afraid to show the mannequins in the windows. There’s another part to it for the photographer which is- to make an image and then later- a week, ten days later after it was developed and came back in the mail, to look at it and to discover what it was you took a picture of. Especially what you didn’t see at the time because you were worried about the guy down the street or getting run over by a car. Then later at your leisure project it on the wall and think about it. So that’s still for me the fun of photography. Although now with a digital camera you can see it immediately. I am not complaining about that but I have to train myself not to fall in love with what I just took and put on my computer. Just give it some time. It’s kind of like when you are angry with someone and you want to write a mean letter – before you send it, give it a few days. So that is a kind of wonderful thing about even recent history; you have to give it a little time to become history.

LC: Yeah, absolutely. And there is another part that involves the darkroom. Which I didn’t do with these transparencies; the issue of switching from negative to positive. That’s another drill to add to the mix. I always liked that. And if you are using large format with ground glass, everything is upside down and backwards. Seeing is in your brain not in your eyes. It’s not the lens you are using, it’s your perception.

MM: I remember you described how you felt as a young guy in the city. Borrowing from an old 1964 Roger Miller song, Dang Me– “My Pappy’s a pistol, I’m a son-of-a-gun…” You said, “We were all pistols on fire, New York was ours in the 1970s, so we thought…” That sense of freedom walking around as a young person back during the ‘70s.

LC: Well you know what it’s like, when you are twenty-five and sort of cocky. That song used to be on a ten-inch reel in the darkroom that went on for hours. That’s why I put in the last part- “So we thought…” Now at my age, the things I thought as a kid would become more clarified, are now more muddy. There is no linear way to progress through old age, retirement and complete understanding. You just have to look in at any given stage in your life and see what’s up. So that’s what I was doing when I was twenty-five. Those years in New York during the 1970s were pretty incredible – life was affordable, creative.

For more photography content on TheVintagent.com, click here.

[1] Source: John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

[2] Source: Publication of New York Women in Criminal Justice in collaboration with Prostitution Task Force.

Ahhhhhhh …. NYC …. back in the pre gentrification days …. when just waking up the next morning alive and unscathed was a major accomplishment . When Hells Kitchen really was hell ….. a loft was an attic space above a business or a factory … when musicians , artists , poets and writers could afford to live there in relative comfort .

Ahhhh …

Now ahhh … I’m not so sure I’d want to do it all over again at my age …. but I’m sure glad I got to do it back in the day . And its sad this generation will never experience it . ! Not that the little snowflakes could deal with it mind you 😎

BTW … the article … the photos …. two huge thumbs up … and thanks for the nostalgia trip