Stuart Allen - Form Following Function

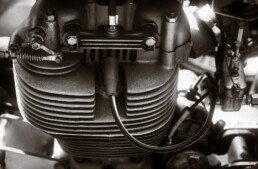

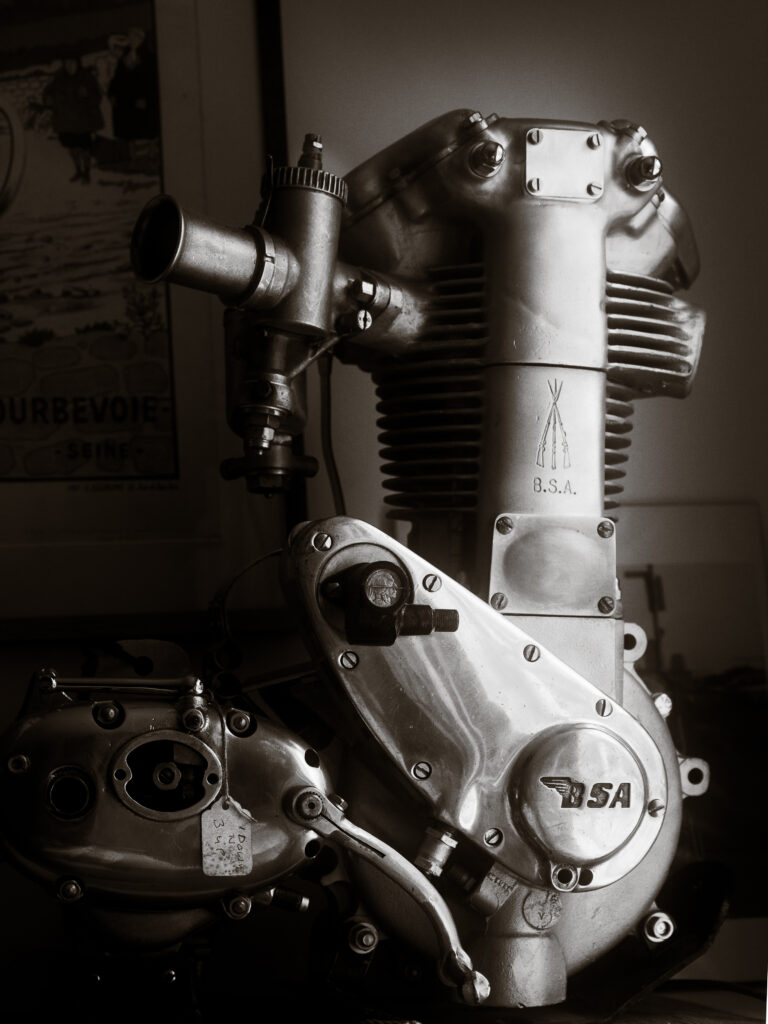

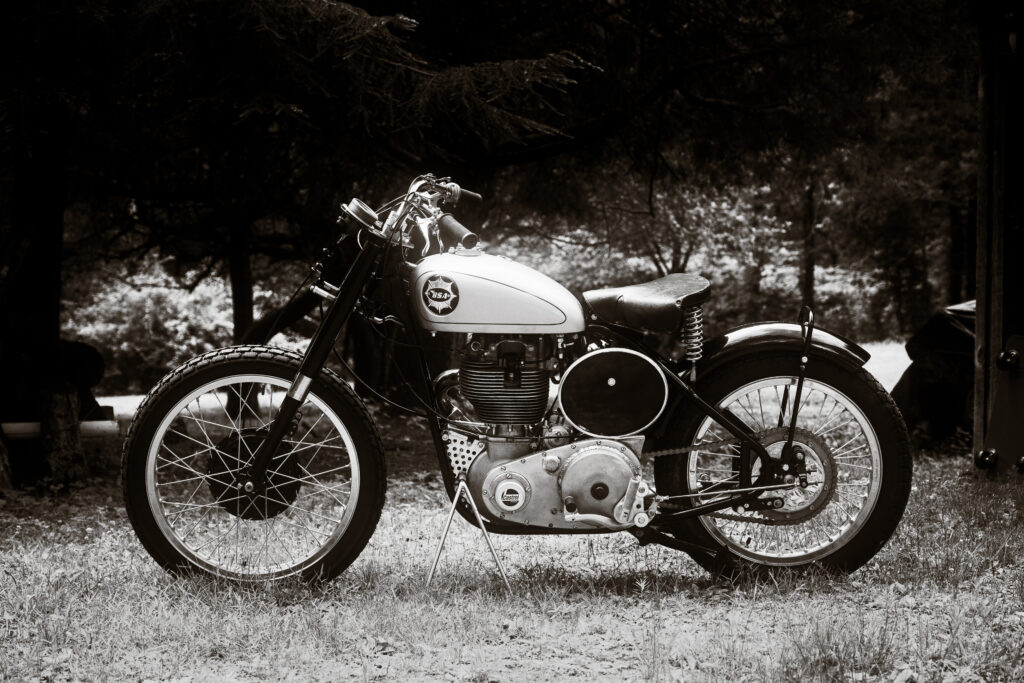

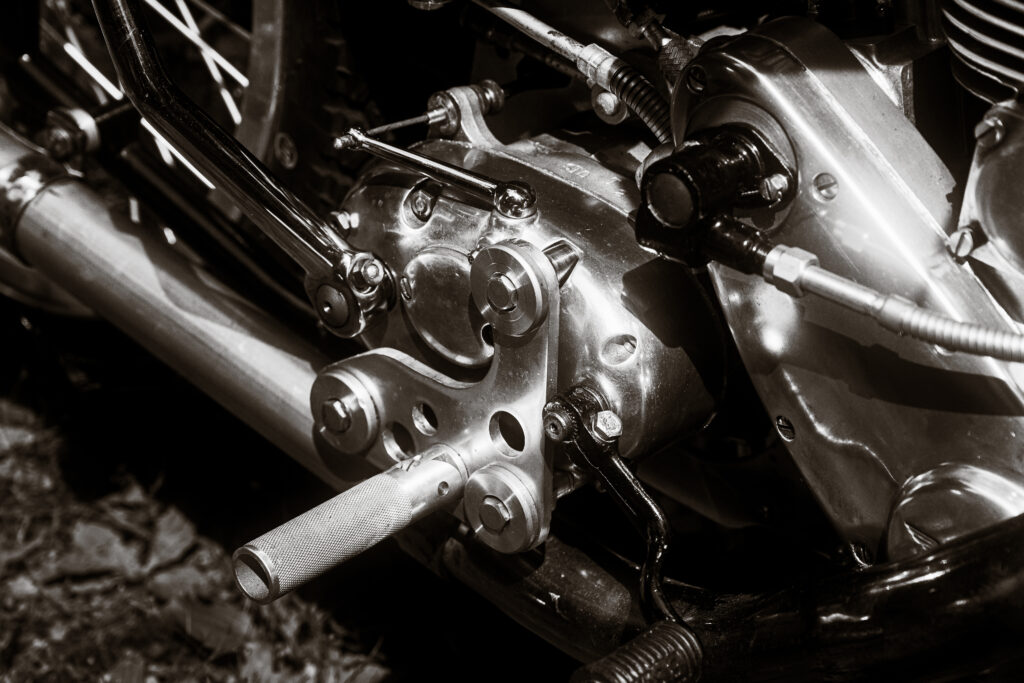

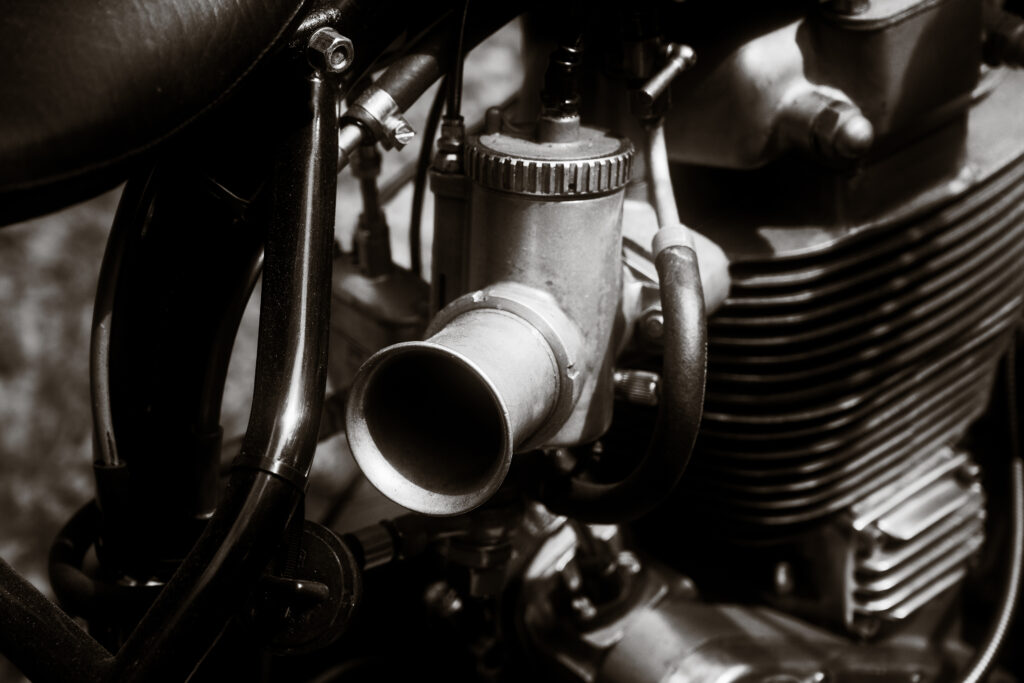

Down a tiny road in what’s called The Quiet Corner of Connecticut is the 1760s farmhouse and garage of Stuart Allen. Stuart is a special kind of biker/builder. His collection contains one-offs, factory racers, and privateer specials, bikes you’re not likely to see anywhere else. These are not pretty boy customs. They are racers, made only to go fast without breaking. All around the garage are motors that can run wide open for an hour or two, frames and hardware thick enough to survive the pounding. These are bikes purpose-built, brutally efficient and beautiful in their own special way.

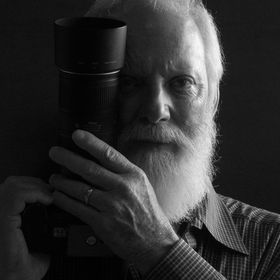

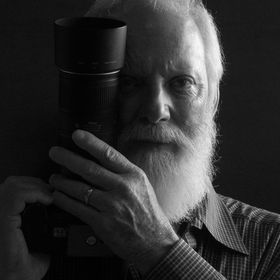

A Life on Wheels, With a Camera

I have always loved motorcycles

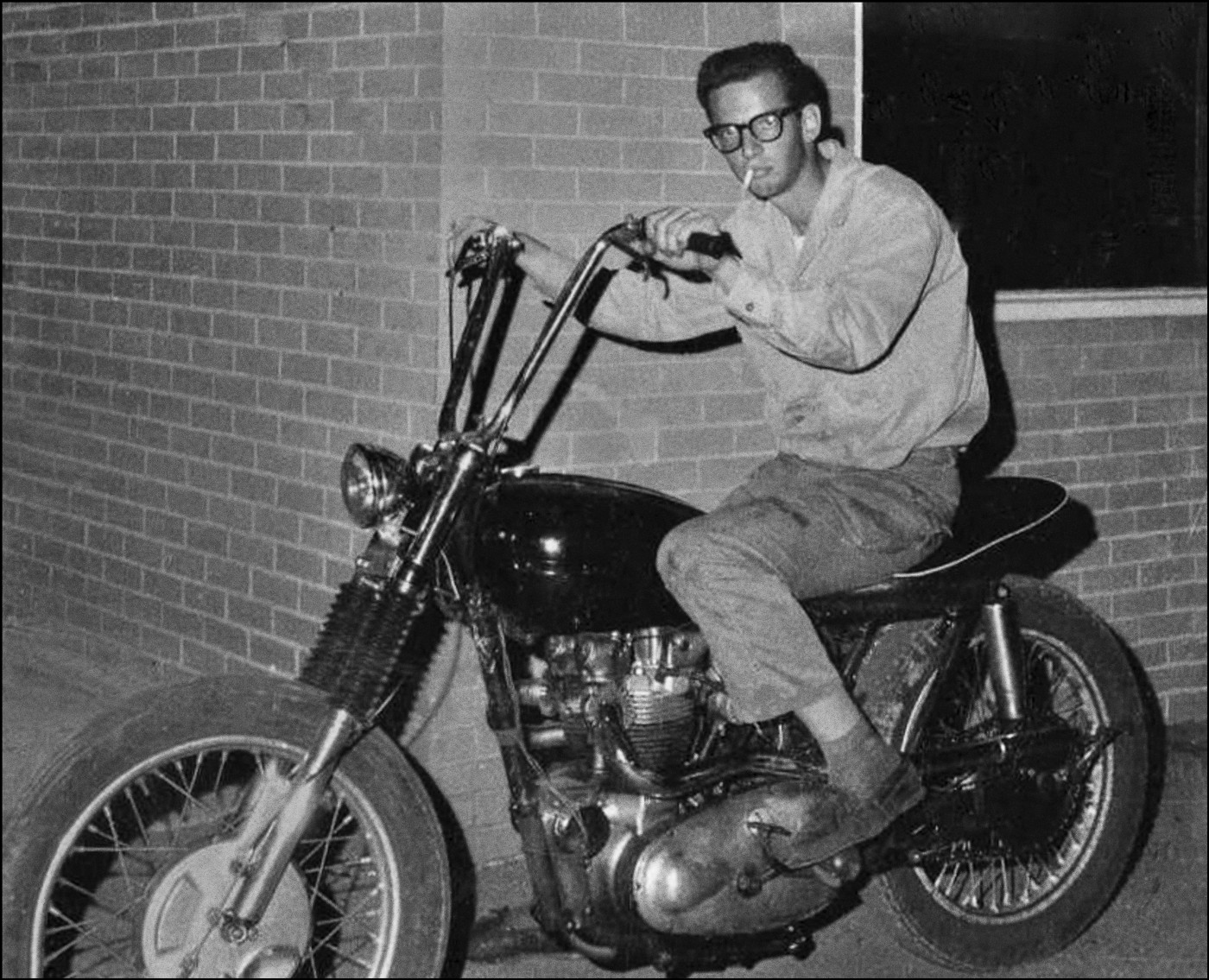

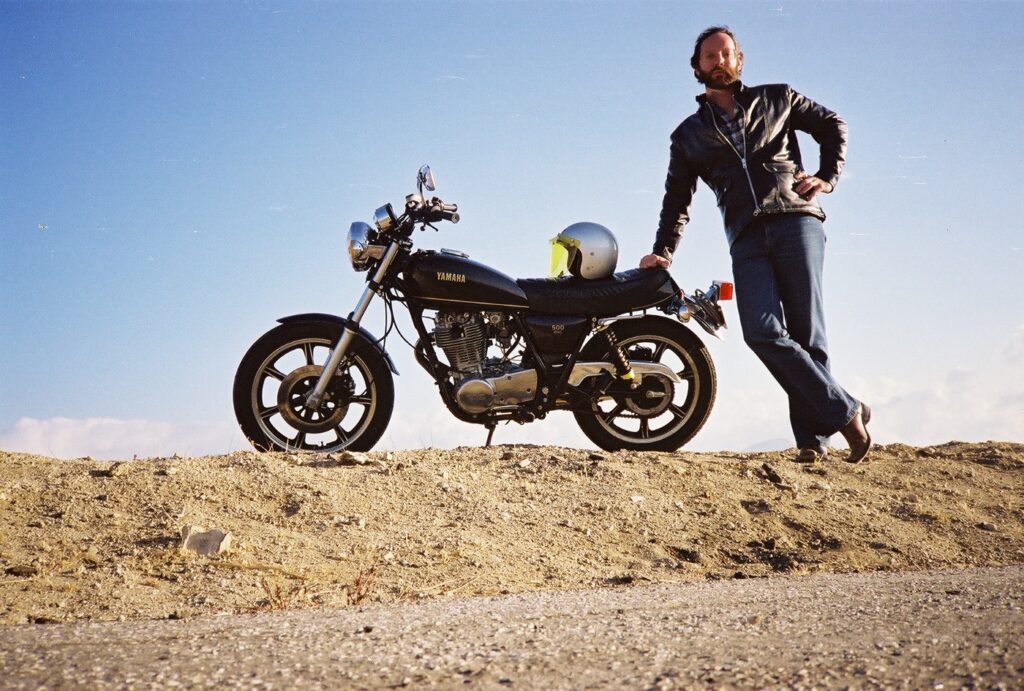

The first riders I remember were Chicago Outlaws. They charged headlong through the downtown Chicago streets, all black and chrome and straight pipes blasting. They weaved through traffic, greasy denim kings on shiny metal horses. They owned the road, and they transfixed my fourteen-year-old soul. About a year after I saw them I got my first bike, a Whizzer, and I taught myself how to ride and how to fix it. I graduated from that to a James 125 and then I had a long string of bikes, an Indian 80, some Harley‘s, a Triumph, a BSA 500 single and an Ariel Square Four. As I neared forty, I still had bikes, an Ossa trials bike for the dirt, a Honda Gold Wing for the interstates, and a Yamaha SR 500 for carving the canyons. For a little while, I worked as a bike mechanic, and along the way, I built a few fast-motored drag bikes and raced them in the streets. Mostly the bikes I rode were street rats.