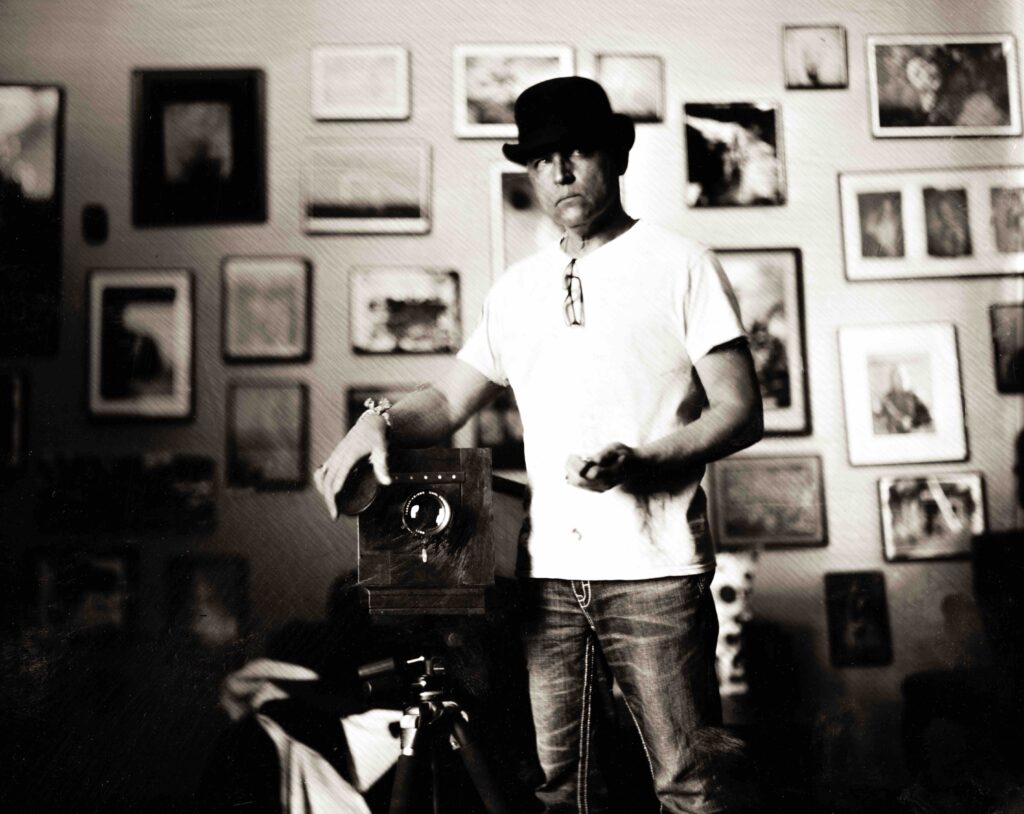

Shooting for Us All: Shane Balkowitsch

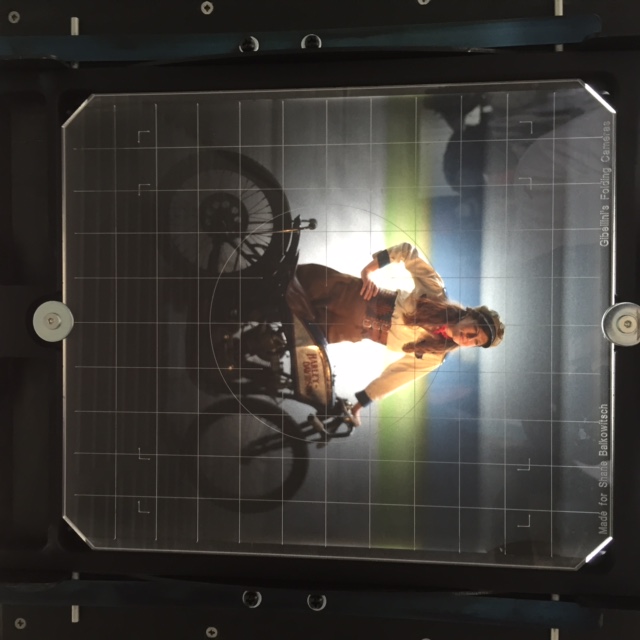

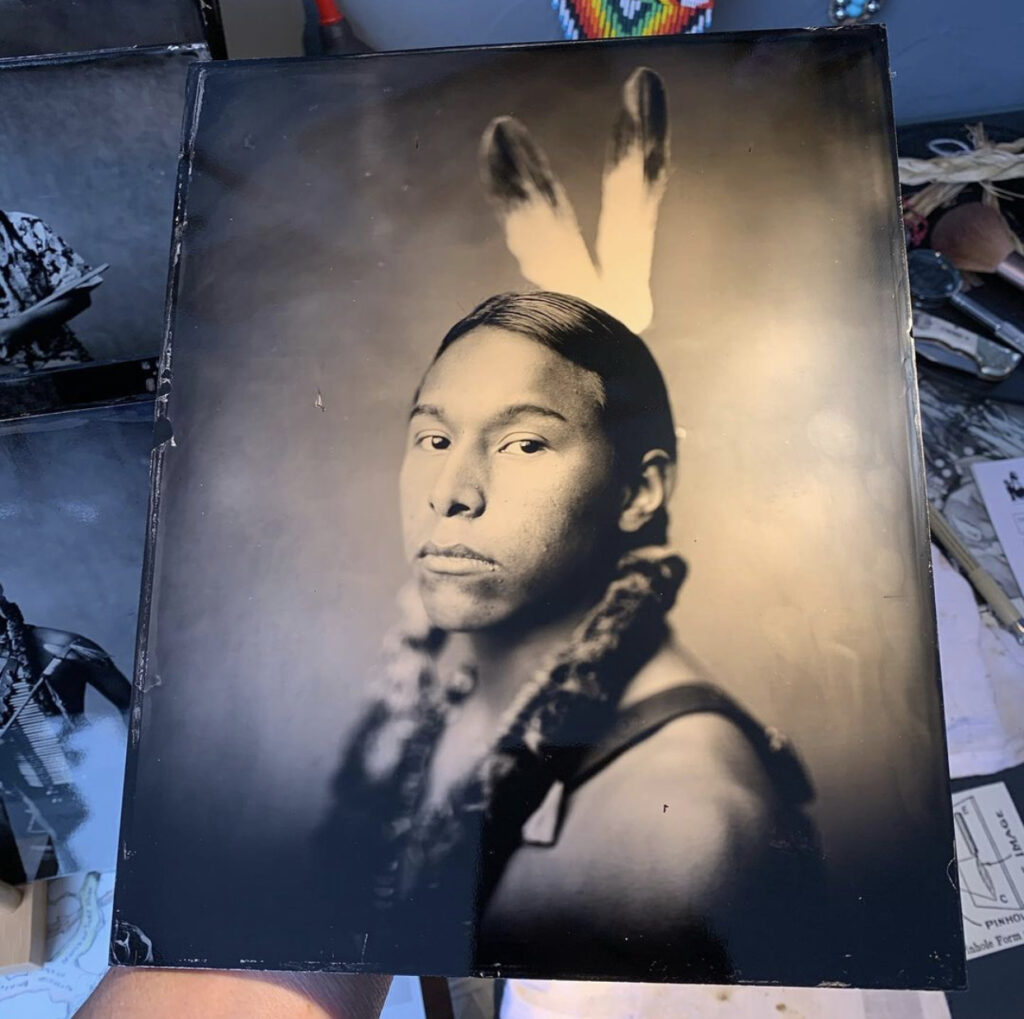

In a well-tuned internal combustion engine, ten seconds at 5,000 revs per minute is enough time for a crankshaft to rotate 833 times. Ten seconds for the average person is at least a couple of eye blinks and a few inhalations of oxygen. And that ten seconds, to wet plate photographer Shane Balkowitsch of Bismarck, North Dakota, is a lifetime. Ten seconds is roughly how long, after pulling the lens cap off his large-format camera, a sitter would have to remain motionless for a clear portrait to be captured on glass plate.

You can follow Shane's work on Instagram and Facebook: there's also a documentary on his wet plate work - 'Balkowitsch' - and you can watch the trailer here.

Velo on the Chase

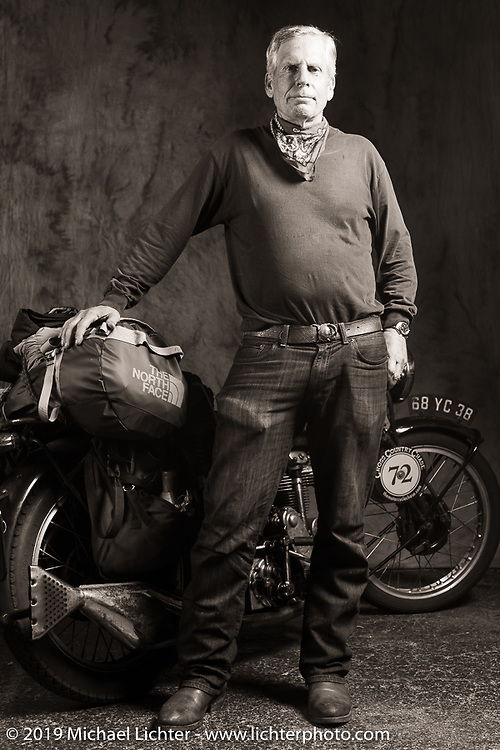

Working with nothing more than a hammer, a Crescent wrench, a screwdriver and a pair of Channellock pliers, a 15-year old Larry Luce assembled his first motorcycle. Those simple tools and the skills he learned led to a lifetime of repairing, riding and touring long distances on vintage machines – including most recently covering 2,400 miles on his 1938 Velocette KSS Mk2 on the first Cross Country Chase. An off-shoot of the Motorcycle Cannonball cross-America adventure, this inaugural event included motorcycles built between 1930 and 1948, with riders traveling north to south from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan to Key West, Florida. Those skills helped him become the first rider to successfully cross the USA on a Cannonball event riding a sophisticated overhead-camshaft machine.

But that didn’t prevent a mechanically inclined Larry from taking apart and fixing all of his friends’ motorcycles, go-karts and minibikes. By the time he was 15 and bought the BSA, the family dynamics were different, and his parents thought him responsible enough for a bike. Plus, there was doubt he’d ever get the B25 functional. Larry promptly diagnosed the source of the lower end noise; the oil pump drive gear was chipped. Finding a replacement gear, he says, is what introduced him to the world of British motorcycles and the people who dealt with them. “English motorcycle businesses tended to be enthusiast operated,” Larry explains, and adds, “I dealt a lot with Jim Hunter – and he was a curmudgeon, he’d just give you shit, saying things like, ‘What the hell are you doing here? What are you looking for and what’s the part number? You wouldn’t be here if you knew what you were doing.’”

Keen Velocette owners in the U.S. and Canada formally organized the Velocette Owners Club of North America (or VOCNA for short) in the early 1970s. Quite simply, these Velo-fellows wanted to share their mutual interest in the English marque that got its start in 1905 when German-born Johannes Gutgemann (who became John Taylor before formally changing his name to John Goodman) and partner William Gue built their first motorcycle, the Veloce. By 1913, Velocette was simply the model name of a two-stroke, 206cc machine and Veloce was proud of early engineering features such as the ‘footstarter’. Later, Velocette developed the first positive-stop foot shift gear change.

By now Larry was working as a civil engineer with the City of Los Angeles, and he had a small fleet of motorcycles. The KSS was taken apart and stashed into boxes, while Larry began looking for replacement parts. Long story short, though, “The KSS wasn’t my main focus, and it sat around in pieces for probably 20 years. The best part of the bike was -- to the best of my knowledge -- it’s the original frame, engine and transmission. But the worst part of it was, there wasn’t one part on it that wasn’t seriously worn out. For example, the crank was junk. The head was junk. “The gas and oil tank were good, but the fenders and stays were all bodged up and kind of a mess. I’d maybe work on something and make a little progress, until I decided that for the 2013 VOCNA rally in Volcano, California, I was going to get it together and use it there.”

Larry has attended most of these rallies. Not only does he complete the 1,000 miles of the event, he also has often ridden to remote rally locations. So, by his reckoning, he’s covered more than 100,000 miles aboard old Velocettes. For the Volcano rally in 2013, Larry had help from Mike and many other VOCNA members to finally get all the parts together for his KSS. Mike helped with the engine build, while Richard Denaple built and balanced the crankshaft. With zero miles on the odometer of the completed KSS, he trucked it to the start of the Volcano rally. “I’m not long on cosmetics,” Larry laughs. “I usually get a bike running and sorted, but don’t spend a lot of time fussing with the aesthetics. The KSS was in bare metal and some primer when it got to Volcano.”

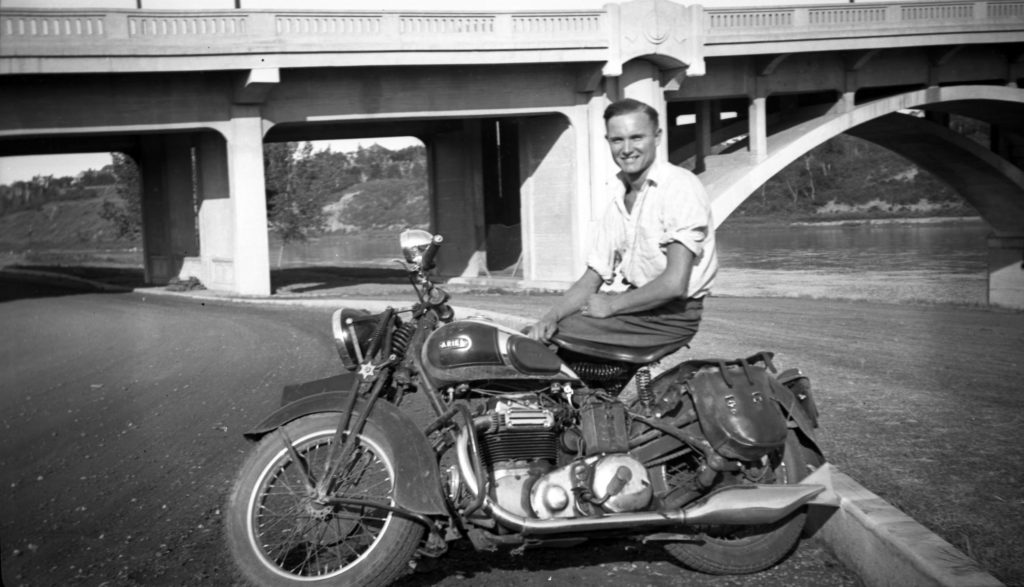

Eventually, Larry ended up spraying the bare metal with a rattle can paint job, but there are no distinguishing Velocette decals or gold lines anywhere to be seen. This is the bike he’d ultimately ride on the Cross Country Chase, an event he knew nothing about until a chance encounter with Todd Cameron, son of legendary Velocette rider Dee Cameron and grandson of the legendary John Cameron, a founder member of the Boozefighters motorcycle club, one of the first SoCal 1%er clubs made famous by the 1953 film ‘The Wild One.’ “I didn’t really know Todd at all, but Mike (Jongblood) and I were at a vintage motorcycle gathering here in Huntington Beach when Todd showed up on a Velocette GTP (another of Velocette’s two-stroke models). We looked at it and asked him what he was going to do with it. That’s when he said he was going to ride it on the Cross Country Chase.”

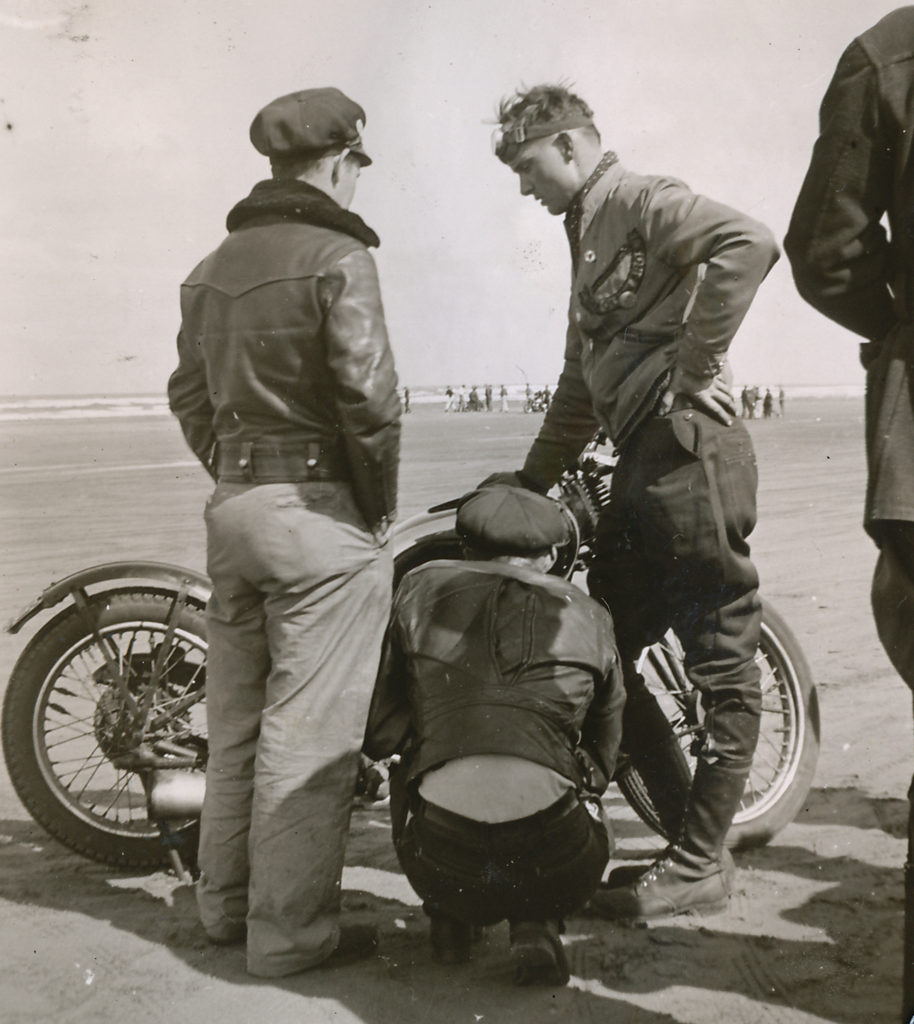

It was the first time Larry had heard of the Chase, but he quickly deduced the GTP was not in any shape to run a long distance. He and Mike talked to Todd for some time, humbly informing him of why they thought the 250cc GTP wouldn’t make the adventure. After that, Larry went home and looked up the Cross Country Chase. He learned the event, staged by the same people who host the Motorcycle Cannonball, was open to bikes built between 1930 and 1948. “I’d always been intrigued by the concept of the Cannonball but didn’t have any motorcycles that were built prior to 1929, one of that event’s criteria,” he says [actually, the rules vary on the Cannonball – from strictly 100+ year old bikes to as late at 1936, depending on the event – ed]. “On the Cannonball, you’re allowed a support team to follow you along, but on the Chase you are on your own. You need to carry everything you’ll need and keep up the maintenance and repairs – but you can ask a fellow competitor for help, or any casual volunteers.”

Larry put the freshened 348cc engine back in the KSS, adjusted chains and tightened all fasteners before adding 150 test miles to the bike. Deeming it ready to go, final modifications included the installation of a modern programmable speedometer and a route sheet holder. Canvas saddlebags bought for $26 from Amazon went over the rear fender, where he stashed oil, an assortment of fasteners, a good assembly of tools, and extra cables and a complete spare magneto. He didn’t need much of what he packed, but Todd utilized some of it.

Todd’s unrestored BSA arrived just nine days before the pair’s departure date. In that limited window of opportunity, Todd did his best to familiarize himself with a machine he knew nothing about. Together, they loaded the Velocette and the BSA on the trailer behind Todd’s Sprinter RV, drove to Sault Ste. Marie and started off on the Chase. Now, the Chase is a competitive event testing endurance (of both motorcycle and rider), speed (completing the 250 to 350-mile stages in a timely manner), navigation (following the prescribed route), and general knowledge. Yes, there was a test – and the results counted toward an entrant’s final score.

On the backroads of eight states covered in 10 days, Larry’s only breakdown was a flat rear tire; an easy fix he completed in the parking lot of the Harley-Davidson Museum in Milwaukee. Todd’s BSA consumed a quart of oil every 100 miles and could not be ridden faster than 55mph, normal travel speed was less than 45mph. Larry says they did not stop much during each day’s ride. Todd managed with dogged determination, some advice from others (for example, retarding the magneto timing so the 493cc Sloper engine would carry him up hills) and some parts and pieces from Larry to become the unlikely hero of the Chase. He won the Class I award, and earned himself a Legend award, a Jeff Decker custom bronze, special number plates if he decides to partake in another Chase, and $7,500.

Taking pleasure in his journey was certainly due in large part to the careful preparation of the KSS engine by Mike Jongblood, whom everyone whispers has some kind of voodoo magic with Velo motors. Success in the ride was also testament to Larry’s wrenching skills, learned decades ago and beginning with nothing more than patience and perseverance and four simple hand tools.

Larry adds, “There is something to be said for a level of technology which allows an enthusiastic kid with few tools and eve less knowledge to turn a pile of parts into a functioning motorcycle. A machine which, if it falters, there is a fair chance you can fix it with what’s in your toolbox and what you find on the side of the road,” and of his latest adventure, he concludes, “The Cross Country Chase is an event that allows vintage motorcycle enthusiasts to use their machines in the manner the makers intended. It also proves vintage vehicles can be viable long-distance transportation. In my opinion, there are few better ways to travel.”\[Many thanks to Michael Lichter for allowing use of his amazing Chase photos. Michael has photographed every Cannonball event since 2010: see all this photos here.]

Coping with COVID: the Auction Scene in 2020

It’s not a brave new world: it’s a strange new world (apologies to Aldous Huxley). Life has certainly changed during the COVID pandemic, but one thing remains the same; riding a vintage motorcycle or cruising in an old car or truck IS a socially distanced activity.

Buyers and sellers of special-interest vehicles are keeping auction houses busy, but there have been challenges in the sales calendar. Luckily, in the land of motorcycle auctions, the large January 2020 Mecum sale in Las Vegas was unaffected by any COVID fallout. The story was different by mid-March.

From their website, posted March 17, an update said, “In accordance with the CDC’s recommendation to postpone events involving more than 50 people over the next eight weeks, we will be rescheduling our March and April events.” Some were rescheduled, like the Gone Farmin’ Spring Classic and Indy 2020 auction. Other events, such as Portland 2020 and Denver 2020 were canceled outright. Mecum’s first live auction took place June 17 to 20 in Davenport, Iowa, with the Gone Farmin’ sale of vintage tractors.

To ensure each live event meets state, county, town and venue guidelines, Mecum submits their plans well in advance to authorities. New regulations include temperature checks at the door, mandatory use of face masks (whether indoor or outdoor), physically distancing in auction arenas and one-way entrance and exit scenarios. “We adjust and add to our plans to the point where we all feel safe, it’s a great team effort,” Sam adds.

“There could be up to 50% of bidders just online or on the phone, and the more photographs the merrier,” Sam suggests. “The more you can give a potential bidder, the better the result. We’re helping sellers understand why we need as many photos as possible, because there might not be as many potential bidders able to see a motorcycle in person. We also encourage sellers to send in video of a bike being ridden or starting and running – that’s highly educational for bidders to see, especially those who can’t or won’t be there in person.”

Daredevil in Training: Corinna Mantlo

Riding the Wall of Death is a hard business. It’s a particular brand of vertiginous motorcycle daredevilry requiring long hours of backbreaking labor and little pay. Moving, setting up and riding the Wall takes dedication and commitment, with danger as a constant passenger. Once a part of almost every traveling carnival, the Wall of Death has almost disappeared from modern culture -- as few as four remain in the U.S., with 11 or 12 still operating in Europe. It’s a hard life, but the Wall of Death and other mechanized daredevil shows have captivated Corinna Mantlo. The New Yorker, with a background in history, film, fashion and upholstery, is riding in the tracks of women and men who, over the past century, have ridden the Wall and entertained hundreds of thousands at carnivals and country fairs. She’s learning the art of getting horizontal at speed – and 2020 was to be her year to finally get higher up the boards. Coronavirus cancelled those plans, but Corinna remains a champion of the lifestyle.

[Corinna's film career included the only documentary on NYC's Fulton Fish Market, 'Up at Lou's']

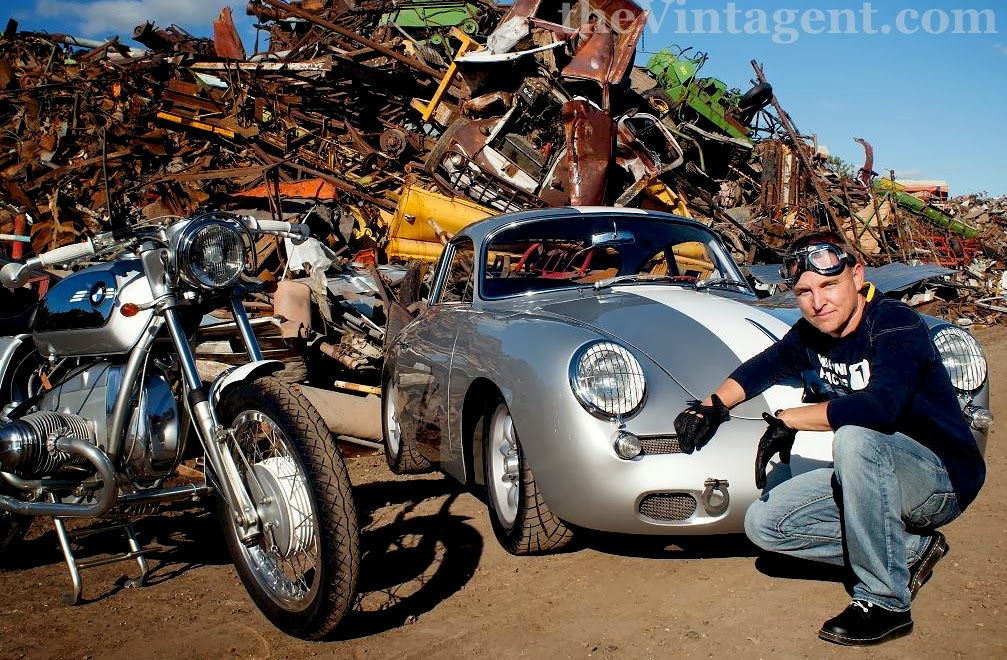

She continues, “By 2013, to take these films to a much larger audience, I cold-called Paul d’Orleans (founder of The Vintagent), and said, ‘I’ve got this project I could use your help with.’ Within 10 minutes, we were together on the idea.” The 'idea' was to create the first international Motorcycle Film Festival, riding the wave of energy building around the new custom bike scene. The Motorcycle Film Festival was incredibly popular with filmmakers, with over 100 new films submitted every year, and had the support of the motorcycle industry too, with support from Honda, BMW, and Cycle World, among many others. Paul came on board as a mentor and Chief Judge, using his industry and media connections to build an amazing international judging panel, including the likes of Ultan Guilfoyle (curator of the Art of the Motorcycle exhibit), Mark Hoyer (Editor of Cycle World), Melissa Holbrook Pierson (The Perfect Vehicle), customizer Paul Cox, and many other heavy hitters in the world of motorcycles and their related culture. The MFF premiered many features, like 'Why We Ride' and 'On Any Sunday: the Next Chapter', and had satellite screenings at Wheels&Waves in France and at EICMA in Milan (via Deus ex Machina). The arts festival scene is every bit as difficult as riding the Wall of Death, and the MFF was knocked down in 2016. But when the front door shuts, there's always a window, and when The Vintagent was rebooted in 2016, film became an integral part of its architecture, and Corinna came on board as the Editor for Film. She brings new films every week to this site, which has become the world's largest collection of curated online motorcycle films.

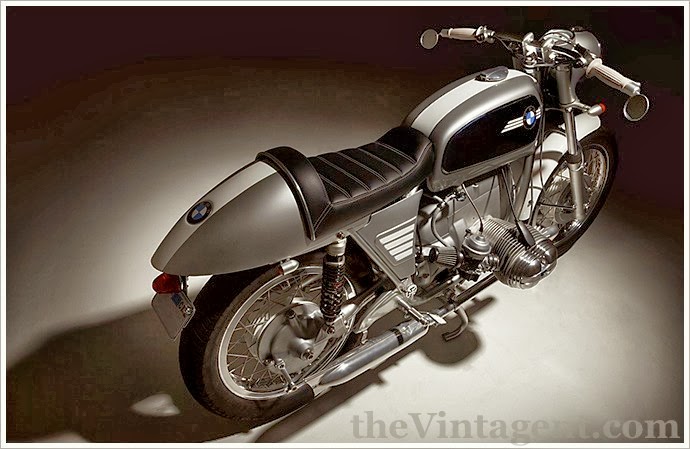

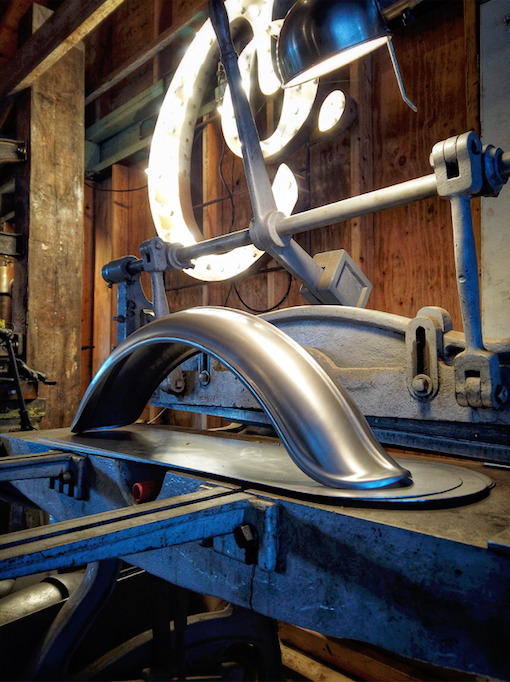

Cooper Smithing Co.

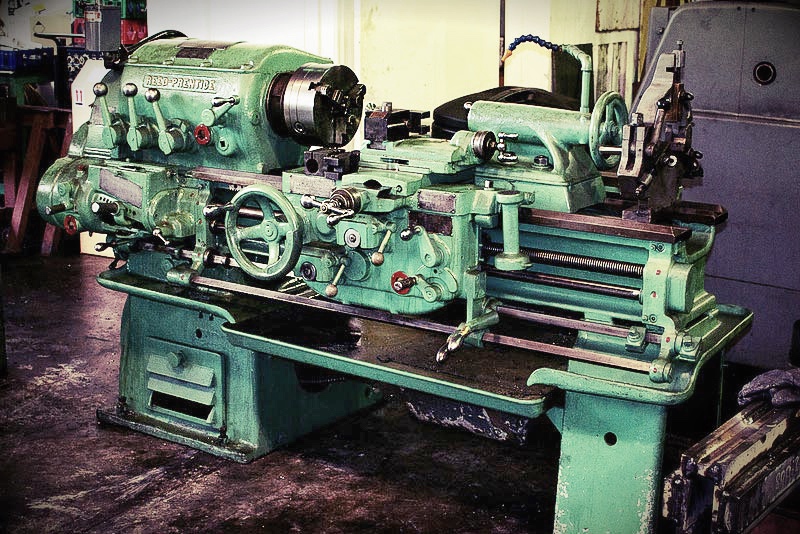

A warm summer rain is falling in Washington state when Joe Cooper answers the phone. He missed picking up the first call; probably he was swinging a hammer to form a signature Cooper Smithing Co. custom motorcycle / hot rod fender. Or, he was wearing hearing protection while manipulating metal with one of his vintage machine tools. Either way, after talking about the sere conditions and how welcome the moisture is, we slowly segue into talking about Joe’s passion for metal and machines.

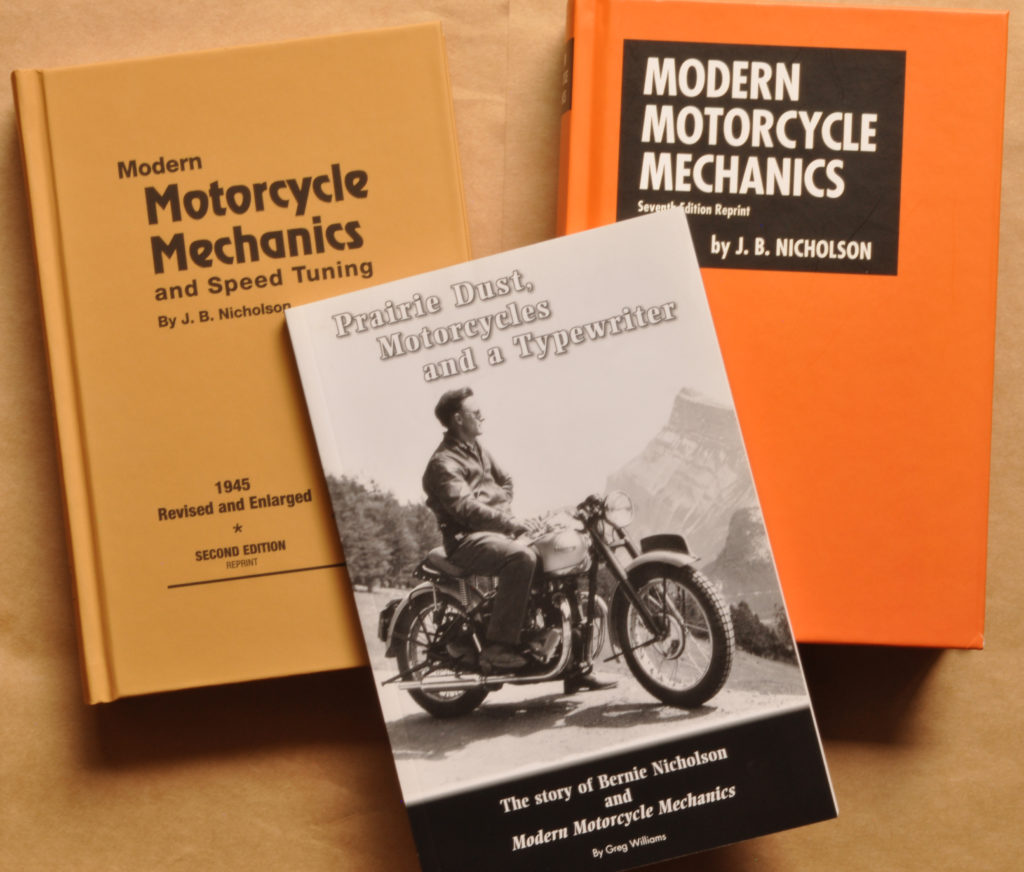

Modern Motorcycle Mechanics: a Dual Origin Story

We were 18 when my pal Dave suggested borrowing a friend’s 1973 Plymouth Duster to drive east from Calgary to Saskatoon. He wanted to visit his dad, who lived in the so-called Paris of the Prairies, while I was eager for a road trip.

That tired orange Duster with its 318 cubic inch V8 engine was thirsty for both fuel and oil, but it traveled the 380 miles to Saskatoon. After meeting dad Ray, Dave immediately wanted to show me what was in the garage. A lifelong motorcyclist who commuted to his job as a press operator from the moment it was warm enough to ride in the spring until the frost would form on his beard in the fall, Ray’s two-car garage held a daily-ridden Harley-Davidson along with a couple of projects in pieces. Tucked into a corner, however, was a dusty Triumph Bonneville. I went straight for the Triumph, thinking it a rather attractive motorcycle.

Until I saw the Triumph in Ray’s garage. Although it took me another three years, and with a substantial loan from a very sympathetic girlfriend who is still by my side, I finally managed to secure the purchase of a 1971 Triumph TR6R. When I bought the bike, the seller handed me a greasy, dog-eared catalog and said, “If you ever need any parts or advice, call up these guys.”

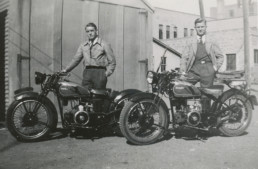

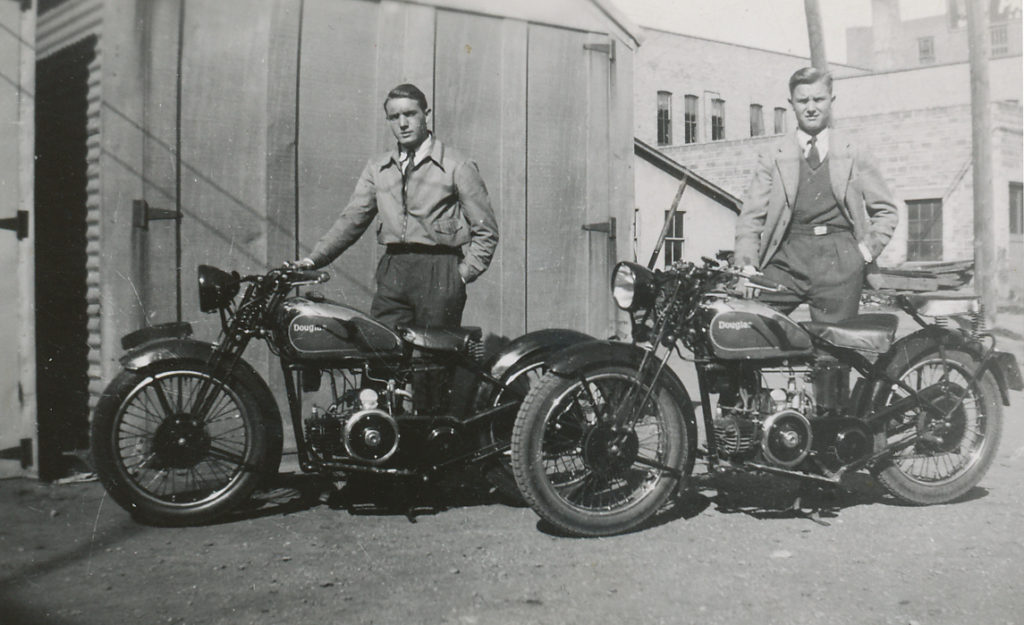

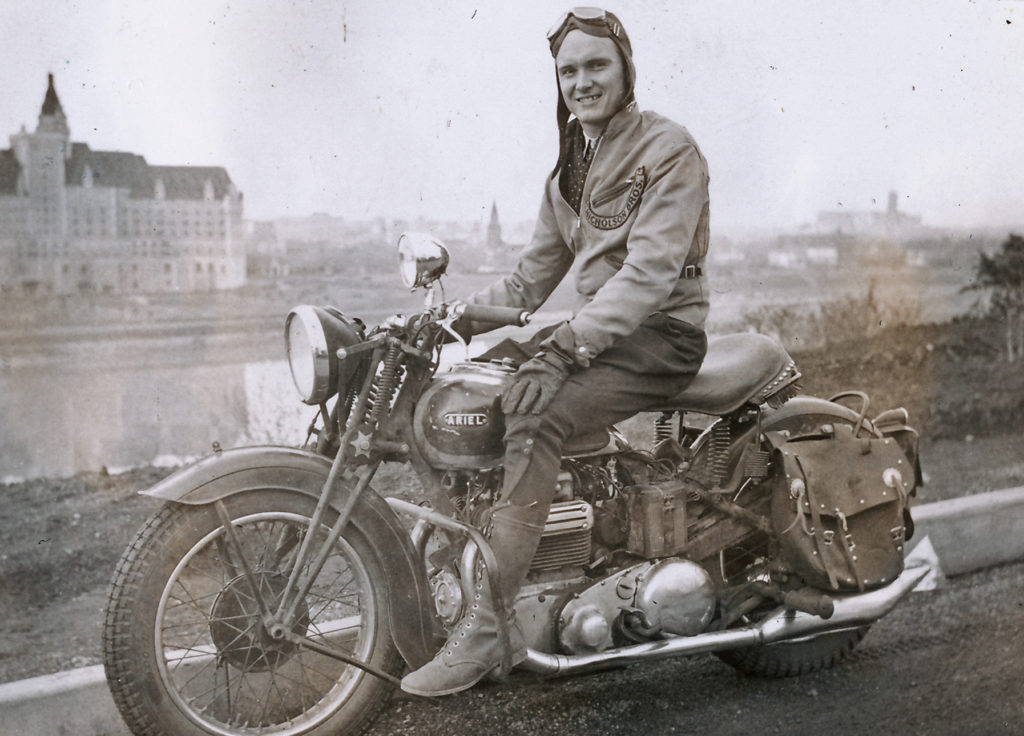

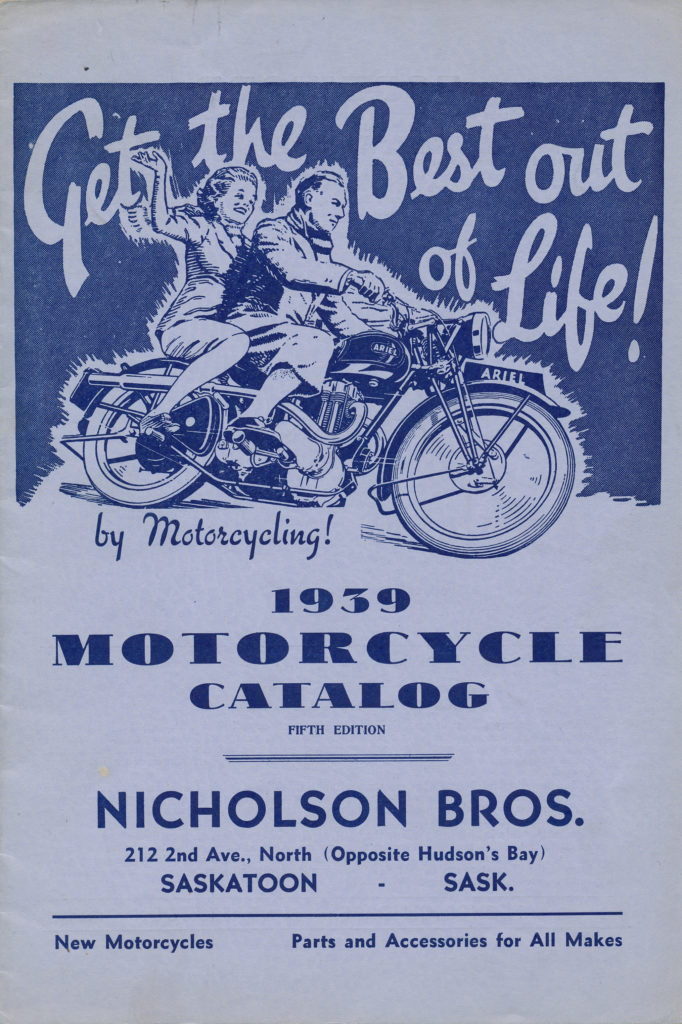

The Nicholson boys were eldest brother Lawrence and his sibling Bernie. Motorcycle-crazy from a young age in Saskatoon, in 1932 when they were 17 and 14 years old, they imported their first British machine, a 198cc DOT. By 1933, they’d put a few miles on the DOT, managed to sell it for a profit, and ordered more English motorcycles. Behind their parents’ apartment block, they used wood from the packing crates to knock together a shed, officially becoming Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles.

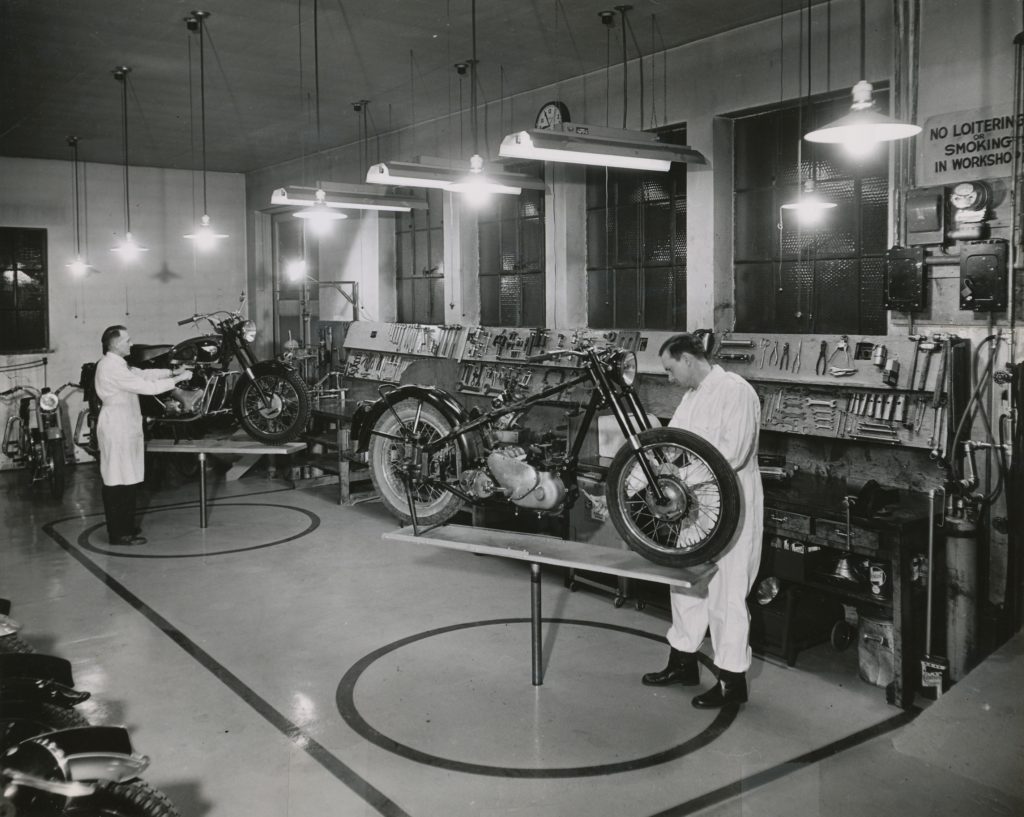

After high school, Lawrence and Bernie attended Saskatoon Technical Collegiate and graduated from the Motor Engineering and Machining program. While they’d already acquired much hands-on repair knowledge, at Tech they honed their skills and learned how to properly operate tooling such as a metal lathe, cylinder boring bar and valve grinding equipment.

Although young, both brothers were exceptionally bright and competent in handling business and wrenches. They were as inquisitive, genuine and honest as a Prairie summer day is long and that helped earn them much trust. Leaving behind the wooden shed, a brick and mortar location in downtown Saskatoon saw the brothers firmly established, where Lawrence looked after the business side of the operation while Bernie, who seemed to be somewhat more mechanically gifted, naturally gravitated towards service.

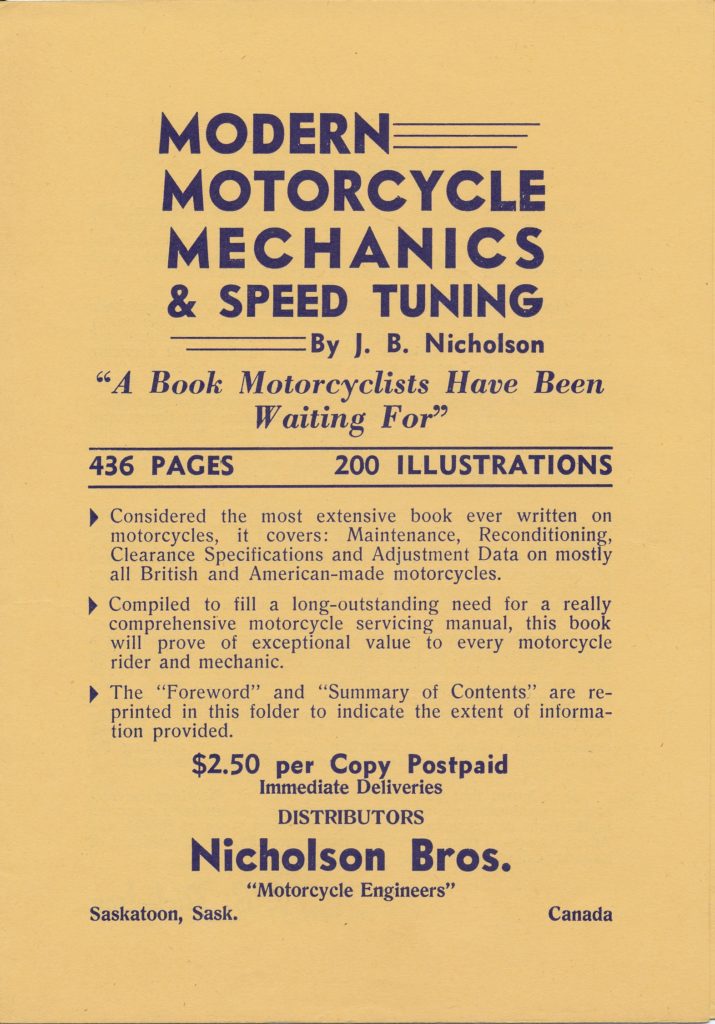

Now, with motorcycles being sold by Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles and shipped by rail to all corners of Canada and some locations in the U.S., consistent repair advice became a necessary commodity. Many of the British machines, however, simply were not supplied with anything that could be considered an essential owner’s manual. To remedy the drought of reliable information, it was J.B. Nicholson who sat down at a typewriter to begin work on a book he’d call Modern Motorcycle Mechanics and Speed Tuning.

Many overseas servicemen maintaining Indian military motorcycles had been writing to Walker looking for assistance. Information they had at hand was nothing more than a parts list, and unfortunately for the English-speaking mechanics, the list was published in French. Walker asked Nicholson to write a technical series to help his Motor Cycling readers understand the internal intricacies of the Indian.

Nicholson’s first article, Servicing American-built Indian Machines Used in The British Army, was published Christmas Day, 1941. He followed that up in April 1942 with a two-part series with the rather ungainly title Servicing the 750cc Side-valve Model “45” Harley-Davidson: Details of a Complete Mileage Maintenance Schedule and Hints on Engine Overhauls Covering a Machine Used in Large Numbers by the American Forces.

Essentially self-published and printed by National Job Printers in Saskatoon, the First Edition was released in June 1942, with a run of 4,000 copies. Immediately successful, another 10,000 copies were printed in 1944. It cost $0.95 a copy to print, and the book retailed for $2.50. Circulars promoting the book were printed and sent out with every mail order, and ads ran in American motorcycle publications as well as Popular Mechanics. Cases of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics were sold wholesale and shipped to buyers including Clymer Motors in Los Angeles and Johnson Motors of Pasadena.

In the Foreword to the Second Edition, published in April 1945, Nicholson wrote: “The revised edition, as the original, has been prepared to render service to all associated with motorcycles, from the novice to the experienced rider and professional mechanic. Design, Operating, Maintenance Requirements and Servicing Procedure are amongst the items extensively covered. In scope and detail the new issue of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics surpasses any previous motorcycle publication.”

When I bought the ’71 Triumph Tiger it ran. Poorly. With the dog-eared Nicholson Bros. Motorcycles catalog in my hand and the words of both the seller and Dave’s dad, Ray, echoing in my mind, one of the first calls placed was to the shop. It was possible to make arrangements and meet Nicholson himself at the warehouse and purchase parts. On our first meeting, I chatted with Nicholson for several minutes and believe I purchased a set of Lucas points and other tune up parts. As the discussion wound down, Nicholson pulled out a copy of his 766-page Seventh Edition, handed it to me, and said I’d find it useful. If I had any questions, he added, I shouldn’t hesitate to call.

After I’d bought the Triumph, I discovered Billy’s News in downtown Calgary. On the stands were titles such as Walneck’s Classic Cycle Trader and British journals including The Classic MotorCycle and Classic Bike. Since 1992, I’d been purchasing and reading these magazines with interest, and thinking of Nicholson, pitched a story about the man and his book to The Classic Motor Cycle. They agreed to let me have a try.

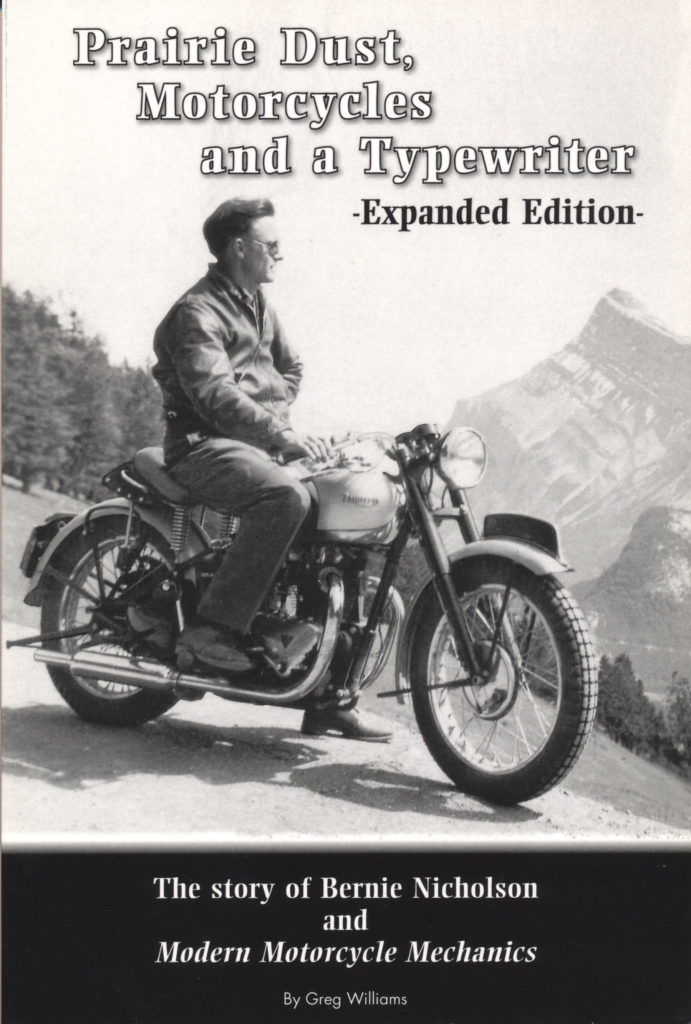

And that brings this tale forward to 2009, when nine years after his death, I began working on a book about Nicholson – essentially a book about a man who wrote a book. In the process of publishing Prairie Dust, Motorcycles and a Typewriter, Nicholson’s son granted me the rights to reprint any of the seven editions of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics. I’ve done that, having enlisted Prairie-based institution Friesens in Manitoba to print and bind both the Second Edition and the Seventh Edition of Modern Motorcycle Mechanics. With a steady demand, another run of the Seventh Edition was reprinted late last year, in 2019.

Nicholson replied, “There was little done by others in the way of compiling a motorcycle manual, and I considered a manual a necessity. The manuals that may have come from a manufacturer were good, so far as they went. But we had machines going to remote corners of this country, with no repair facilities at hand. The manufacturer’s manuals missed a lot of things that could only be gained by personal experience.”

And that’s still the case, although now almost 50 years out of date and certainly no longer Modern, the information contained in Nicholson’s tome remains applicable to any disciple of the Internal Combustion Engine and the motorcycle.