Art and the Motorcycle

100 Years After the 'Indian Summer', Part 4: Oliver Godfrey

[Adapted for TheVintagent from the excellent book ‘Franklin’s Indians’]

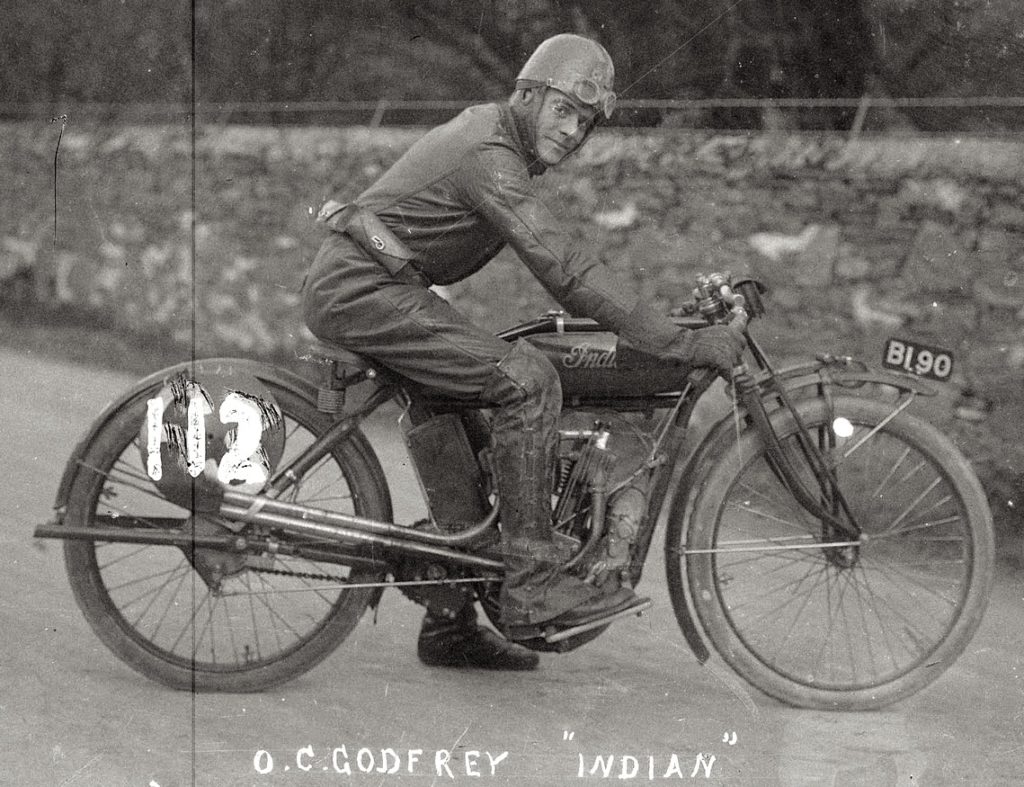

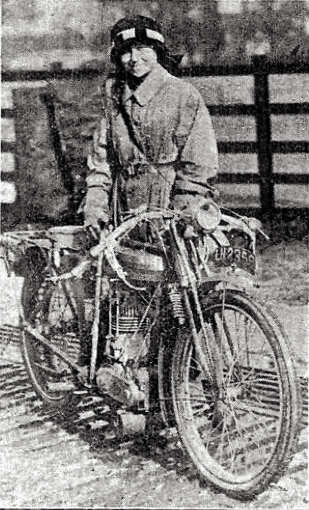

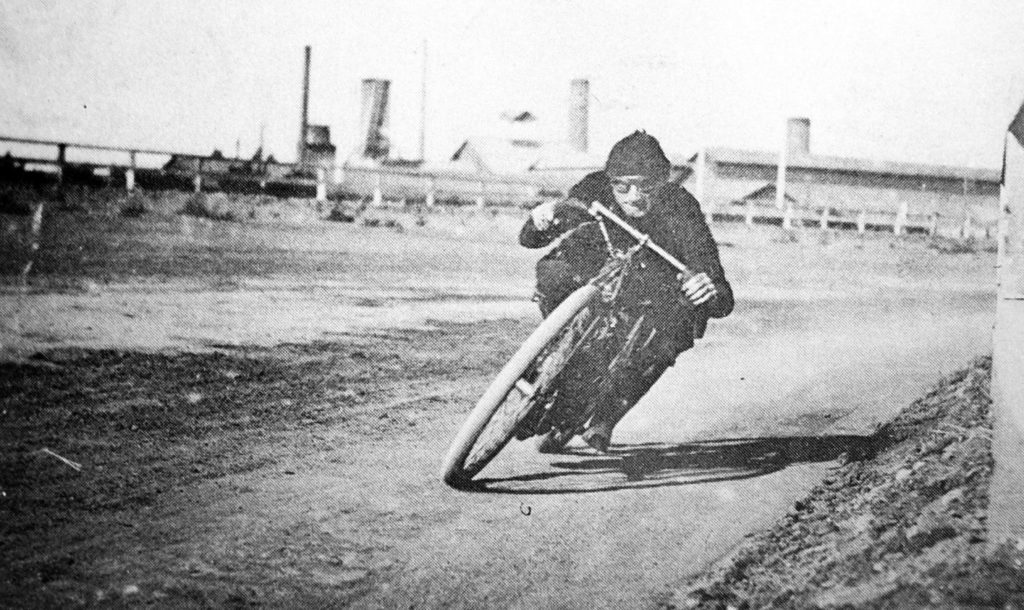

Oliver Cyril Godfrey was born in London in 1887 to an artist father, a painter and engraver, who decamped to Australia before 1901. Mrs Godfrey eventually remarried, and as late as his 1911 TT win, he was still living at his mother and step-father's home in Finchley, employed as a 'motor spindler' (ie, machinist). By this time, young Oliver was a dedicated racing motorcyclist, and began racing at the Isle of Man by the age of 19, first on 726cc Rex twins in 1907 thru '09, then the ubiquitous Triumph single-cylinder in 1910. He at last won the TT in 1911, on his fourth attempt, and raced on the Island until 1914, but didn't get far in 1912, when mechanical trouble at the start line put paid to dreams of a second win. All his TT appearances from 1911 onwards were aboard an Indian.

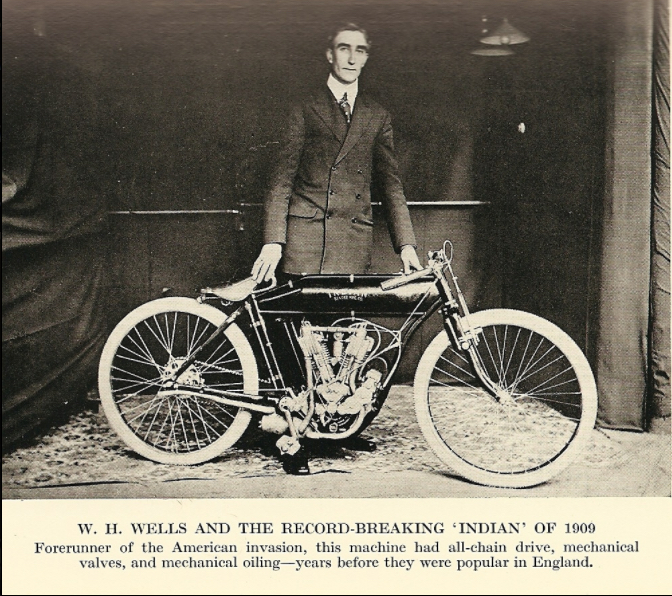

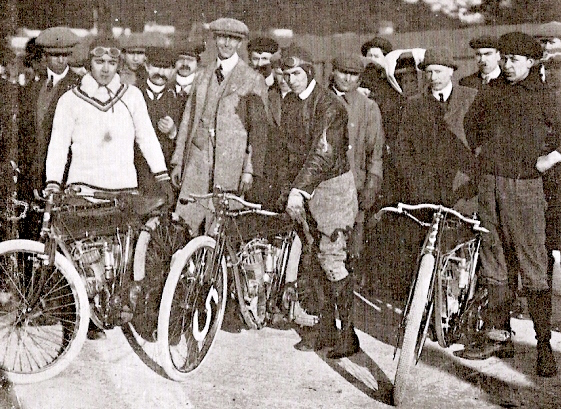

Godfrey was one of five riders supported by the Indian factory to enter the 1911 TT, the other riders being a mixture of English, Irish, Scots and American in the form of Arthur Moorhouse, Charles Franklin, Jimmy Alexander and Jake De Rosier respectively; all these riders are profiled in The Vintagent. The Indian team was managed by UK Indian concessionaire Billy Wells of the Hendee Mfg Co.’s London branch, and “technical advisor” was the great Medicine Man of Indian himself, chief engineer Oscar Hedstrom.

Given the unpaved, country roads which comprised the Isle of Man TT course in those days, falls over the dirt, mud, and stones were common; both de Rosier and Alexander had significant crashes in 1911, yet Godfrey rode consistently and well to finish the race without a fall, just ahead of Charlie Collier (Matchless) who was second to cross the finish line. CB Franklin similarly had a straightforward race, and Moorhouse, although he did fall off once, kept his place on the leader board. Collier had misjudged his gasoline consumption and was forced to take on fuel at an unauthorised filling point, and was disqualified, which elevated Franklin and Moorhouse to 2nd and 3rd places.

Godfrey’s winning feat established a number of “firsts”, including the first ever '1-2-3' clean sweep by a factory team, first TT win by a foreign manufacturer (Indian), first Senior TT win, first win on the new 'Mountain' course over Snaefell mountain (the same course used today), and first Mountain course Race record (though Frank Applebee’s Scott set the first Mountain course Lap record). In a rather upbeat TT race report reprinted in the 1912 Indian UK sales catalogue, Godfrey was described as “small in size, but a bunch of muscles and nerves and a magnificent rider”.

Godfrey failed to start in the 1912 TT, “Did Not Finish” in 1913, but was able to claim 2nd place in the 1914 Senior TT. His Isle of Man record and results at the Brooklands Track in Surrey place him at the forefront of motorcycle racers pre-World War One. Godfrey was a business partner with 1912 Senior TT winner, Scott-riding Frank Applebee, in Godfreys Ltd, motorcycle retailers located at 208 Great Portland Street, London W1. This firm continued trading until the 1960s. A 1920 magazine advertisement laid claim to experience in all aspects of the motorcycle trade “including winning the 1911 and 1912 TTs”. Certainly a rare attribute!

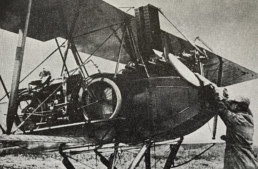

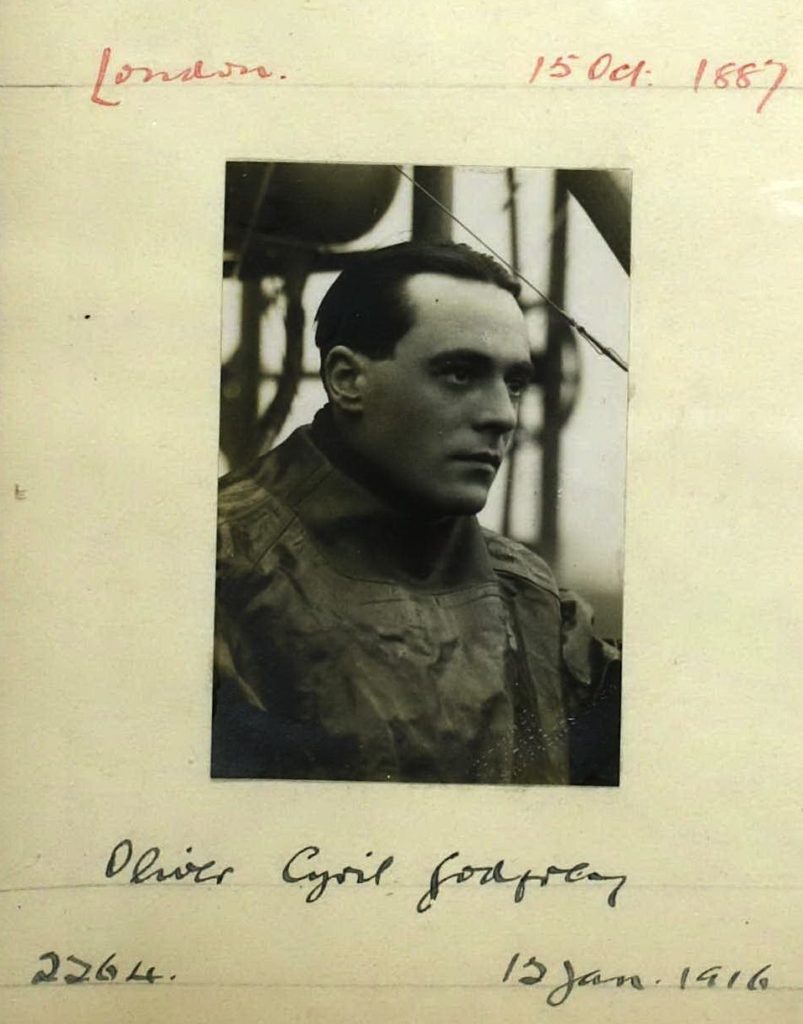

When war against Germany was declared in 1914, Godfrey enlisted as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps. He earned his Royal Aero Club Aviator's certificate in a Beatty-Wright bi-plane at Hendon (now a massive RAF museum) in January 1916. The RFC used the Royal Aero Club for pilot certification through WWI, training about 6300 pilots during the War. In the photo above, from Godfrey's flying certificate, the wires behind him are likely wing-wires on his Beatty training bi-plane.

Oliver Godfrey was posted to 27 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps which first arrived in France in March 1916 and by June was based at Fienvillers, 10 miles west of Albert in the Somme Valley, and 15 miles behind the front lines. Their “base” used a cow pasture for a runway, where the fliers and ground-crew all slept in tents. The squadron was equipped exclusively with single-seater fighter scouts, the Martinsyde G100, nicknamed the 'Elephant' as it was big and responded slowly to pilot input. Unsuitable as a fighter, the 'Elephant' had a long flight range, so was redeployed as a bomber and reconnaissance scout, and flew missions up and down the western front, to Bapaume, Cambrai and Douai.

The bombing success of 27 Squadron became their main role from 9 July 1916 onwards, and enemy airfields at Bertincourt, Velu and Hervilly were added to the list of targets. Oliver Godfrey joined the Squadron at this point, a relatively easy period for British fliers, when the chances of survival were still reasonable. The start of the Third Battle of the Somme on 15 September saw the squadron attack General Karl von Bulow’s headquarters at Bourlon Chateau, followed by more bombing of trains around Cambrai, at Epehy, and Ribecourt. By August 1916 the German Imperial Army Air Service was reorganized, and new “hunter” squadrons were created, becoming the pioneers of specialist fighter aircraft formations and tactics (the 'Dicta Boelke'), soon to be universal. The first 'hunters' were Jagdstaffel 2, formed at Lagnicourt, under the command of Oswald Boelcke, Germany’s top-scoring pilot at the time, and a young Manfred von Richthofen (the 'Red Baron') was among pilots hand-picked by Boelcke for the new unit, and by 16 September Jagdstaffel 2 had received enough of its allotted aircraft to commence operations in earnest.

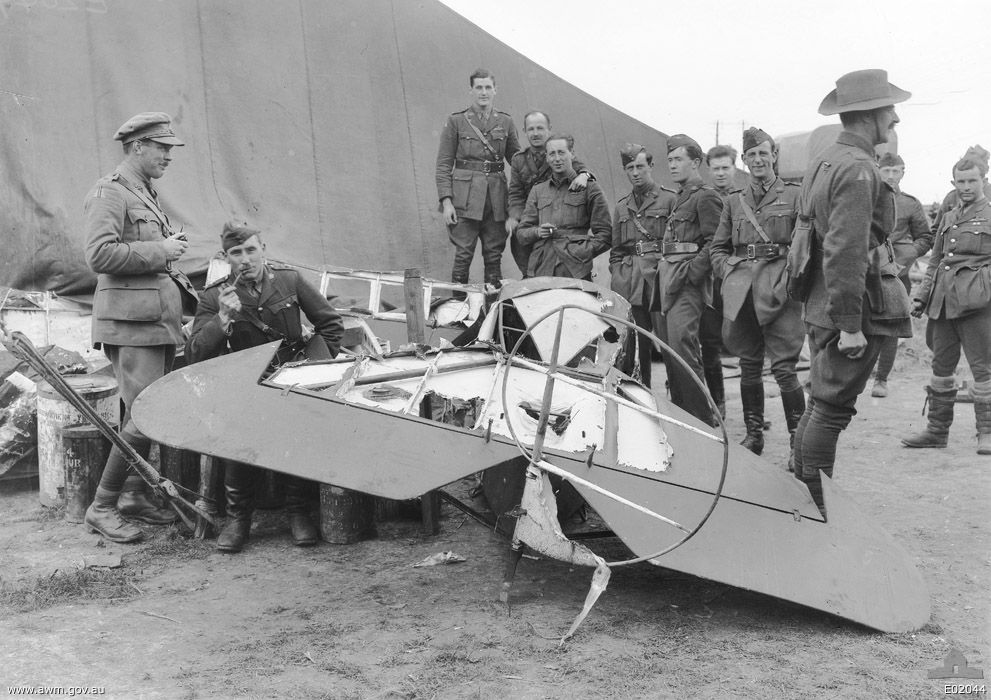

For RFC units like 27 Squadron, their 'honeymoon' in France was definitely now over. It was during a bombing mission by six Elephants to Cambrai on 23 September that Oliver Godfrey lost his life, most likely shot down by Hans Reimann of Jadgstaffel 2, who was himself killed in the same engagement. The events of that day are described in a history of 27th Squadron written by Chaz Bowyer: "On September 22nd bombing raids were carried out on Quievrechain railway station. One pilot, seeing that his bombs had failed to explode, proceeded to strafe the engine driver of a train attempting to leave the station quickly. Later in the day, fifty six 20lb bombs were scattered in Havrincourt Wood, suspected of harbouring German infantry. The following day 27 Squadron sent six Elephants on an Offensive Patrol over Cambrai, setting out at 8.30 am. All six were attacked over Cambrai by five Scouts of Jagdstaffel 2 led by Boelcke in person - with disastrous results for the Martinsydes. Sgt. H. Bellerby in Martinsyde 7841 was shot down almost immediately by Manfred von Richthofen (his 2nd official victory) while within seconds two more Elephants piloted by 2/Lts. E.J. Roberts and O.C. Godfrey were destroyed by Leutnants Erwin Boehme and Hans Reimann. Recovering from the shock of the first German onslaught, the remaining three Martinsydes continued the fight despite being outnumbered and outclassed by superior German aircraft. Lt. L.F. Forbes having exhausted all of his ammunition made one last defiant gesture by deliberately charging at the Albatros piloted by Hans Reimann, ramming the German scout in a near head-on collision. Reimann spun to earth and his death in a crushed cockpit, but Forbes, in spite of one collapsed wing with aileron controls shattered, managed to nurse his crippled Martinsyde towards base."

Godfrey had only been in France 3 months, and was one of 252 crew and 800 planes lost during this 4+ month campaign, in which the RFC lost a staggering 75% of its men in the battle...yet on the ground it was far worse, with 750,000 dead in an evil Autumn. Many of the pilots coming to France at that time were relatively inexperienced, deployed to replace downed airmen as fast as they could push them out of the training schools. German pilots, with vastly superior aircraft and plenty of tactical combat experience as the months went by, racked up hundreds of 'kills', before the tide of the war turned, and they in turn became the hunted.

When Godfrey was shot down, Cambrai was situated miles behind enemy lines, and its unclear what became of his body or whether, indeed, there was anything left in the burned-out wreck to bury. His memorial is Ref. IV. F. 12. at Point-du-jour Military Cemetery, Athies, near Arras. On settling his estate some 18 months later, the small fortune of £1475 went not to his mother, but to Frank Applebee, Scott-mounted winner of the 1912 TT and Oliver’s business partner in Godfrey’s Ltd, the motorcycle dealership in London which carried its founder's name nearly 50 years after lying down in the green fields of France.

[Adapted from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’, by Timothy Pickering, Chris Smith, Harry V. Sucher, Liam Diamond, and Harry Havelin, available here]

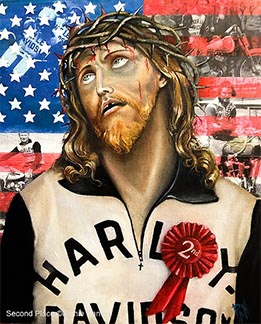

'Built for Speed' Exhibit

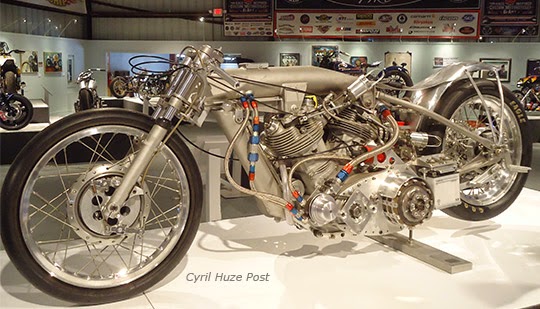

The world's most popular custom motorcycle website - the Cyril Huze Post - was kind enough to review my 'Built for Speed' exhibit at the Buffalo Chip in Sturgis, which ends tomorrow. I'll write my own notes on the show here soon, but 5 days of travel plus the effort of physically mounting a show with 32 motorcycles and 100 pieces of art has left me temporarily drained and 'away from my desk'. Enjoy Cyril's reportage:

The 14th Annual Michael Lichter’s “Motorcycle As Art” exhibition officially opened on Sunday August 3rd under the theme “Built For Speed”. The who’s who of the motorcycle industry gathered at the Buffalo Chip exhibition hall to admire the beautiful and rare display of more than 35 race-inspired custom motorcycles curated by internationally famous photographer Michael Lichter and vintage motorcycles expert Paul d’Orleans. Members of the press had the opportunity to get a preview of this exhibition and to learn about the builders and how they found inspiration in one of the many branches of racing: Speedway, Flat Track, Drag Racing, Board Track, Grand Prix, Land Speed Record, etc. Each machine is displayed with its description and racing style origin, from “Cut-downs” of the 1920s, “Bob-jobs” of the 1930s, “Café Racers” of the 1950s, ‘Drag-bike’ Choppers of the 1960s, and ‘Street Trackers’ of the 1970s.

As always, entry to the Buffalo Chip's 7000' purpose-built Michael Lichter art gallery is FREE and this year, hours have been extended, now opening at 10:30am into the evening concert hours (10:30pm). The show is open until Friday night August 9. To find the gallery, head to the Buffalo Chip and turn east on Alkali Road; go to the East entrance. The gallery is next to the EAST entrance and does not require a ticket to enter.

Michael Lichter wants to give a special thanks to the 'Motorcycle as Art' industry sponsors; Ace Cafe Orlando, Avon Tires, Baker Drivetrain, Burly Brand, Carhartt, Crusher Exhaust, Hot Leathers, Icon Motorsports, J&P, Kuryakynb, Motor Bike Expo Italy, Mustang Seats, Progressive Suspension, Ridewright Wheels, Tucker Rocky/Biker's Choice, S&S Cycle.

The 32 motorcycles in 'Built for Speed' include customs by long established and emerging builders, side by side with factory-loaned machines. Builders sending bikes include Alan Stulberg (Revival Cycles), Arlen Ness, Bill Dodge (Bling Cycles), Bill Rodencal (Fat Dog Racing), Brandon Holstein (Brawny Built), Can 'Bacon' Carr (DC Choppers), Dan Rognsvoog/Skip Schultze, Jason Paul Michaels (Dime City Cycles), John Reed (Uncle Bunt), Kenji Nagai (Ken's Factory, Japan), Kevin 'Teach' Baas (Baas Metal Craft), Kirk Taylor (Custom Design Studios), Matt Olsen (Carl's Cycle), Michael O'Shea (Medaza Cycles, Ireland), Nate Jacobs (Harlot Cycles), Pat Patterson (Led Sled Customs), Paul Cox (Paul Cox Industries), Paul Wideman (Bare Knuckle Choppers), Roland Sands (RSD), Skeeter Todd, Tator Gilmore, Warren Lane, and Zach Ness (Arlen Ness, Inc).

Factory-built machines include a custom 'Street' 750 from the Harley-Davidson design dep't, Indian's 'Spirit of Munro' streamliner built by Jeb Scolman, and a Land Speed Racer from Confederate Motorcycles, alongside Icon 1000s' 'Iron Lung' road racer, a replica of George Smith's 'Tramp' from S&S, Deus Ex Machina's 'Dakdaak' Honda CRF 450x, and Clem Johnson's original Vincent 'Barn Job' from John Stein.

Artists on the walls include Conrad Leach, Darren McKeag, David Uhl, Eric Hermann, Harpoon, Jeff Nobles, Marc Lacourciere, Michael Lichter, Richie Pan, Scott Jacobs, Scott Takes, Susan McLaughlin and Paul d'Orleans, Tom Fritz, Trish Horstman, and an all new '21 Helmets' display of race-inspired Bell Helmets from SeeSee Motor-Coffee in Portland.

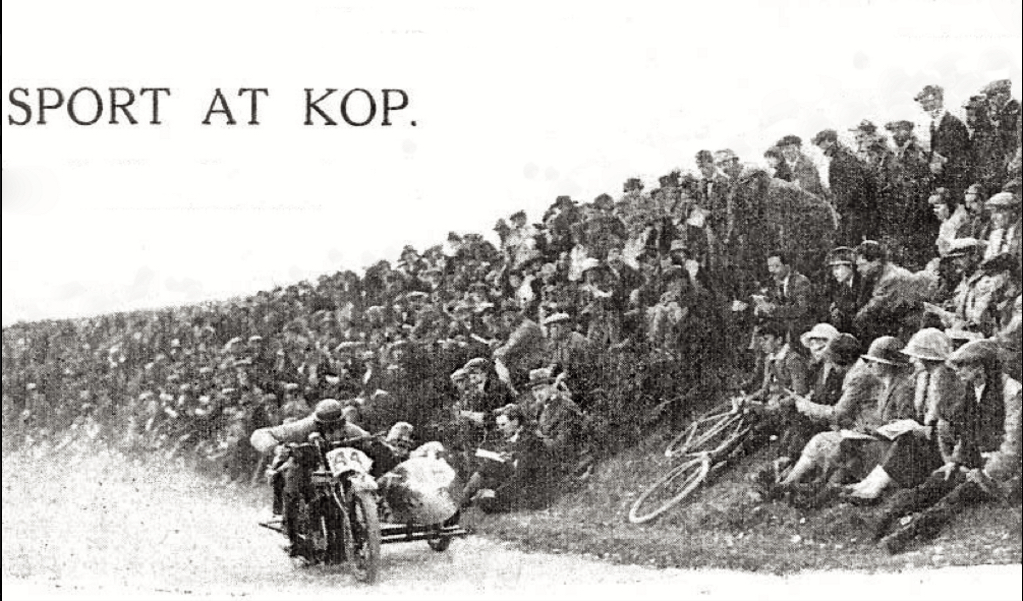

Kop Hill Climb

[Words: Colin West and Paul d'Orléans]

In the heart of Buckinghamshire Country, deep in the British countryside, the Kop Hill Climb is among the most historic of all road races. The first race was held in 1910 as a test of machinery on the unpaved, winding road up the tallest local hill. The course begins gently, but the mid-section is a 1-in-6 grade (17%), and steepens to 1-in4 at the end (25%), which seemed nearly insurmountable in those early years of single-speeders with slipping belt drives.

'Crazy' George Disteel and the Vincent Hoard

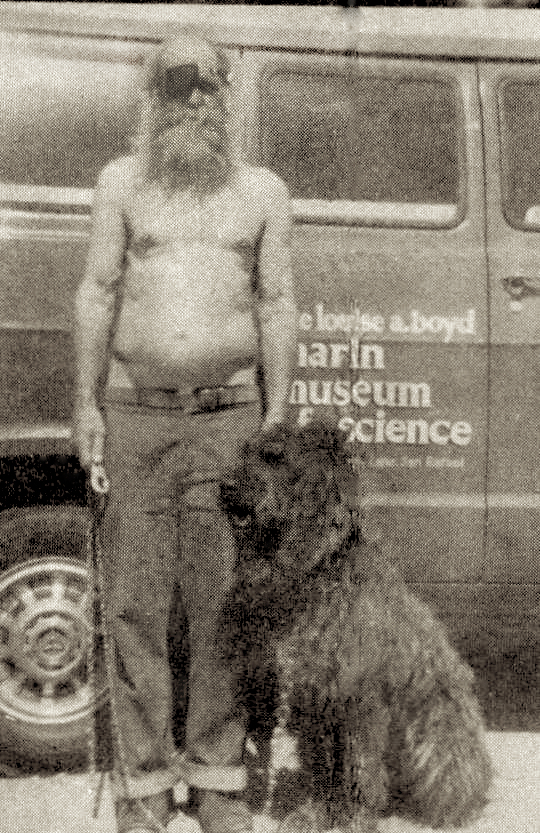

It was a rumor wafting over the San Francisco 'old bike' community for years - the crazy old guy whose son was killed on a Vincent Black Shadow, who spent the rest of his life hunting down Vincents, which he squirreled away in chicken shacks on his property. The rumor was, as far as anyone can tell, based on the real life of George Disteel. George was an avid motorcyclist and fan of Vincent motorcycles, owning a Black Shadow named 'Sad Sack', and was apparently a rider of some skill. Born in 1904, he discovered Marin county in the 1940s after serving in the military - a motorcyclist's paradise, full of empty, twisting roads and year-round mild weather. No one today knows what machines George owned before the Vincent, but he seems to have purchased his Shadow brand new, and created an impression in the local motorcycling community, not only for his riding ability and choice of the World's Fastest Production Motorcycle (as it said in the Vincent advertising), but of his increasingly erratic behavior, and appearance.

A man of great personal discipline, George walked or bicycled many miles per day, maintaining a rigorous exercise routine. He was also fond of wearing very little clothing in sunny Marin, and his ever growing beard usually served as his only upper-torso modesty. Sometime in the late 1950s, his behavior became erratic, and he confided in an apprentice (Disteel was a master carpenter) the story of his 'son', who was tragically killed riding a Vincent at 20 years old. George was never married, although he did have a few liasons earlier in his life, but no-one has yet been able to corroborate whether he had a son, or a paternal relationship with a young man.

In a sense, it doesn't matter, as this story became the justification for his bizarre actions, such as stuffing every nook and cranny of his home and jobsites with paper and old cloth, and searching northern California for fast motorcycles, especially Vincents, to buy and hide away, with the intention of preventing the death of another unsuspecting youth.

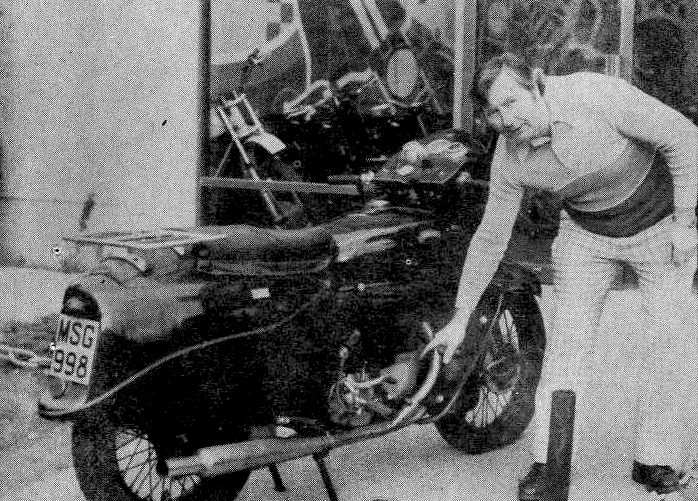

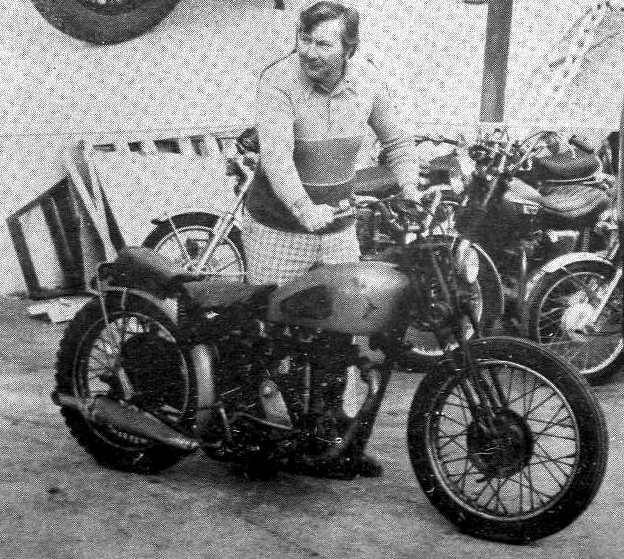

By the end of his life, George had hidden 18 Vincents, two KSS Velocettes, a Norton International, two Moto Guzzi Falcones, an R51/3 BMW, Sunbeams, DKWs, Royal Enfields, plus a lot of rifles, clocks, oddments, antiques, etc. He'd paid for all of this via canny investments in real estate, which made him quite rich - in truth it was hard not to become rich in the San Francisco real estate boom from the 1950s onwards. He certainly didn't appear rich though, with his near-nakedness, lack of bathing, and odd behavior. While he owned 23 properties in Marin county, he lived for a time in a 1952 Hudson Hornet filled with trash. Eviction from the car meant moving into a single-resident-occupancy hotel in San Francisco's seedy Tenderloin district. But first he took a sledgehammer to the Hudson, and had it towed. Towards the end of his days, with cataracts making reading difficult and driving impossible, he wore a pirate's eyepatch made of gaffer's tape, switching from side to side in order to see better.

He collapsed on the street in SF in 1978, aged 74, and a keen-eyed coroner realized he was no indigent, which began a chain of discovery of the man's multiple homes, lands, sheds, hidden caches of motorcycles, storage units, etc. As no heirs could be found, the motorcycles were sold at Butterfields auction house in San Francisco, where the Vincents fetched from $800 - $1500... Some of these motorcycles were brand new or nearly so, and many merely needed a good clean after their years packed in rags within sealed toolsheds. A few of my friends own these bikes, so I'm fairly sure the story is true...at least, the Vincent-in-a-chicken-coop part.

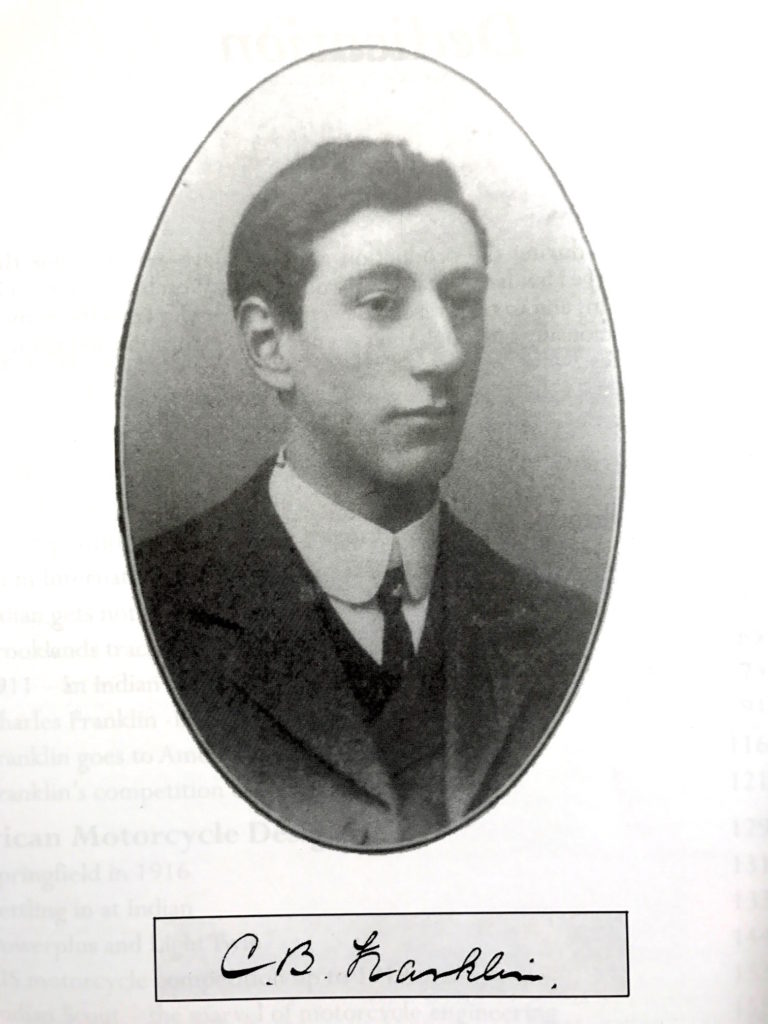

100 Years After the 'Indian Summer', Part 3: Charles Bayly Franklin

[Adapted for TheVintagent from the excellent book ‘Franklin’s Indians’]

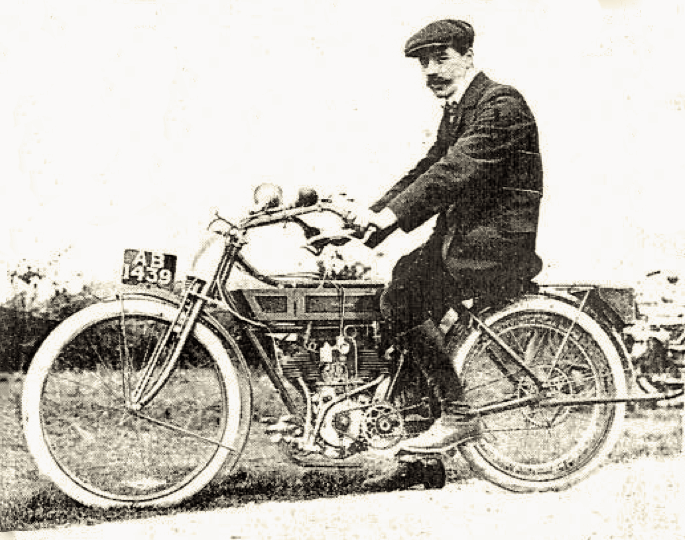

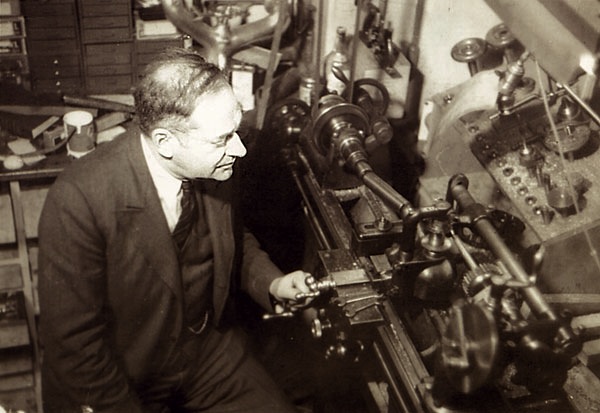

Charles Bayly Franklin was born on 1st October 1880 in Dublin, Ireland, and died on 19th October 1932 in Springfield, Massachussetts, USA, at the age of 52. He was descended from English settlers who came to Ireland during the 17th Century to be farmers. His grandfather’s occupation was stated simply as “gentleman”, while his father was a shipwright and a metal merchant. Charles was educated at a good private school where he showed an aptitude for sciences, and proceeded into tertiary education as an electrical engineer.

By 1905 Franklin was acknowledged to be the first major star of Irish motorcycle competition, and so it was no surprise when he announced his intention to enter, at his own expense, the selection trials held on the Isle of Man to choose a British team for the International Cup Race in France. His machine was a specially ordered JAP 6hp vee-twin, built into a frame of his own design made from Chater-Lea components (who typically supplied raw frame castings). In the selection trial he was up against top riders like the Collier brothers from the Matchless factory in London. Franklin was in the lead until the fifth and last lap, when valve trouble stopped him from finishing. But he had ridden so consistently well that he got selected anyway, along with Harry Collier and JS Campbell. But in France all three had to drop out with mechanical problems and the race results overall were discredited due to rule-bending by the host-country organisers. Simply by being there, Franklin gained the honour of being first to represent Ireland in international motorcycle competition.

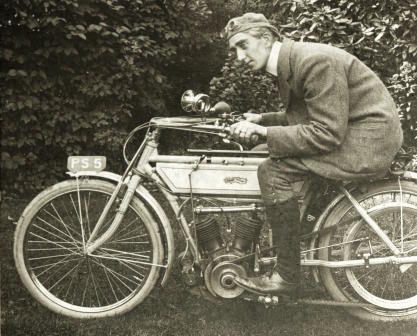

Franklin was selected again for the 1906 British team for the International Cup race, this time held in Austria, and his two team mates were both of the Collier brothers - Harry and Charlie. He rode a giant 8hp JAP vee-twin, and again, the race was plagued with rule-bending and chicanery, but protests were ignored by the organizers. On the train journey back to England the two Colliers, Franklin, their team manager the Marquis de St Maur, and the Auto Cycle Union’s Freddy Straight got to talking. Why not hold a British race? Why not encourage standard road and touring models to enter, instead of freakishly light-weight speed models? But where? In Britain, motor racing on public roads was explicitly outlawed, and a national speed limit of 20mph was in place. So the ACU went to the Isle of Man, which has always had an autonomous parliament, the Tynwald. Recognizing the economic benefits from the thousands of visitors drawn to such an event, the first “Isle of Man Tourist Trophy Race” was announced in 1907. Unfortunately, Franklin couldn’t go; work pressures kept him in Dublin. But he did compete on The Island in 1908, even though his wife had given birth to their first child only 3 days prior! His mount was another JAP single-cylinder machine with Chater-Lea frame, and he did creditably well, coming 6th. The race was won by a Triumph...a fact duly noted by Franklin, as sure enough, in the 1909 TT Franklin appeared on a Triumph coming 5th, and bringing home the Private Owners Prize. Not bad, for an amateur who competed against factory-supported teams!

1909 was the first year Indian racers appeared in the TT, and the lesson Franklin took from the brilliant ride of Lee Evans against Harry Collier is that if one wanted to do well in this race then one really needed to be riding an Indian [or be Harry Collier! - pd'o]. Thus, Franklin was one of several private owners who arrived at the Isle of Man in 1910 on Indian twins, augmenting the officially factory supported Indian team of Evans, Bennett and Bentley. Billy Wells must have supported all of the Indian riders by giving them tyre inner tubes, and all proved to be from the same bad batch. A rear tyre blow-out on the infamous Devil’s Elbow bend saw Franklin crash into the stone wall, nearly going over it and down a cliff. It was not an Indian day.

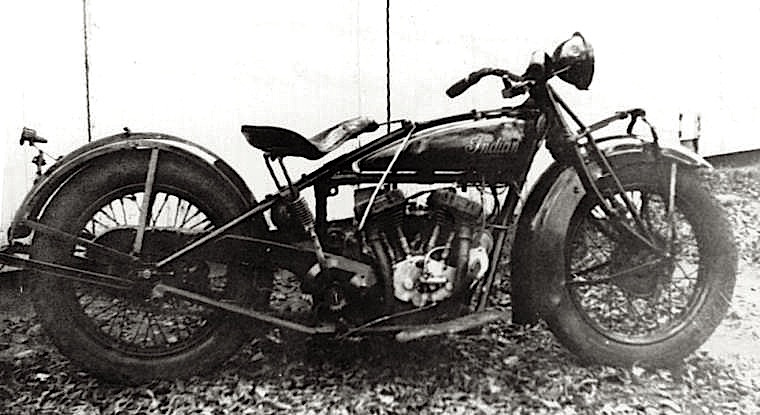

In 1910 Franklin resigned his post at the power station and opened an Indian agency at his suburban house in Dublin. He rode exclusively on Indians, and dedicated himself totally to Indian competition, sales and service, from that day forth. This change of career also gave him the freedom to start competing at the Brooklands Track in England, where he consistently did well against the Collier Brothers and other top cracks, billed as “the Irish Champion”. Indian’s luck changed in the 1911 TT race, now run over Snaefell Mountain, which gave Indian a real advantage with their all-chain drive and two-speed countershaft gearbox. Among the British entrants only Scott and P and M (later Panther) could boast similar arrangements. Other brands used direct belt-drives, sometimes with variable pulleys or epicyclic rear-hub gears; all engineering dead-ends. Franklin rode a steady and flawless race which saw him ultimately take 2nd place, his best-ever TT result.

Race reports described him as “a quiet chap” but “a fearless rider with plenty of good judgement” and one who rides “with the regularity of a well-timed express train”. He was also described as “an Indian convert”. In 1915 Indian’s British concessionaire Billy Wells decided to open a Depot in Dublin for Indian sales and service. He recruited Charles Franklin into the Indian company to be the Dublin manager. But in 1916 wartime conditions and import restrictions forced Wells to close the Dublin end of the British operation. Wells, by now a Director on the Indian board, was able to have Franklin transferred to the Wigwam in the USA where he entered the Design Department.

He was the first designer at Indian to have formal engineering qualifications. Franklin’s subsequent achievements at Indian are another story entirely, for it was Franklin who designed the Indian Scout and Chief models. These holistically designed machines are said by many to be among the very first examples of the ‘modern motorcycle’. They were influential models, and their sales saw Indian through difficult economic times in the early and late ‘twenties. In racing too he continued to contribute to Indian glory, this time as race engine designer and tuner, and overseer of the Indian racing effort against the famous Harley “Wrecking Crew” of 1919-1922 and beyond. But by 1931, the start of the du Pont era at Indian, Franklin does not look very well in official company photos. In August of 1931 he asked for a leave of absence to recover his health. He got steadily worse and passed away in October 1932, of bowel cancer.

Franklin was a man with a rare combination of talents. He had the sporting qualities and the moxie necessary to succeed in the cut-throat world of motorcycle racing. And he had the education, intellect and marketing instinct needed to succeed in the manufacturing side of his beloved motorcycle industry. From the 1911 TT race Charles Bayly Franklin went on to become one of the world’s great motorcycle designers.

[Adapted from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’, by Timothy Pickering, Chris Smith, Harry V. Sucher, Liam Diamond, and Harry Havelin, available here]

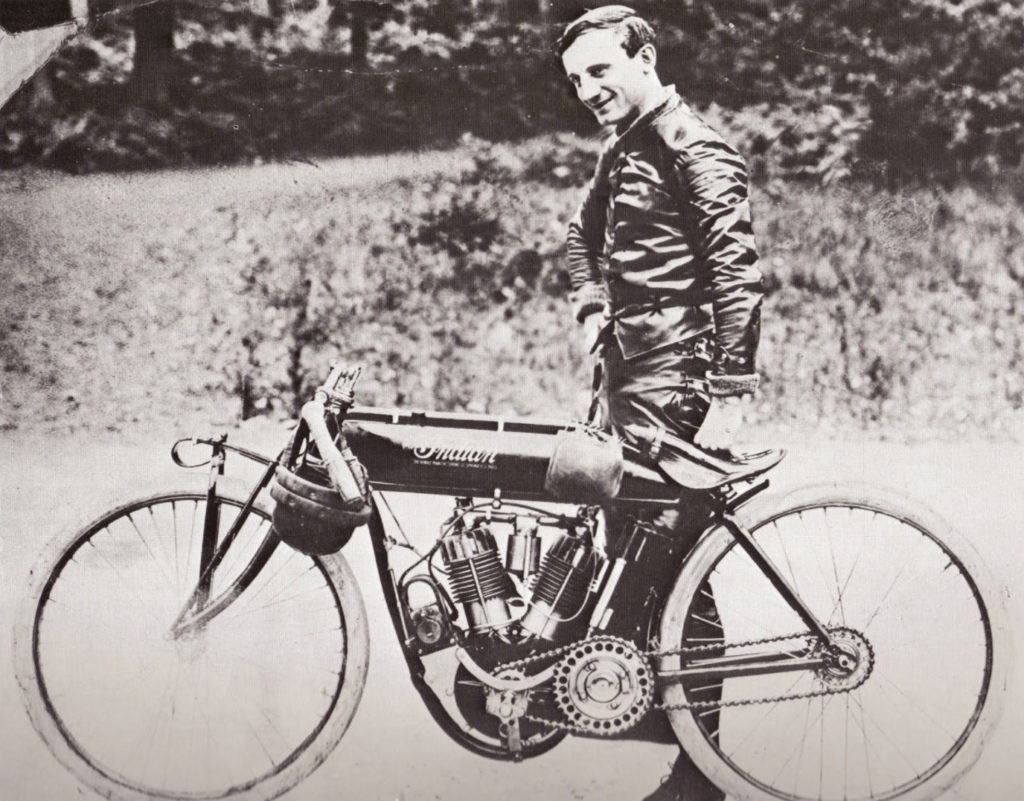

100 Years After the 'Indian Summer', Part 2: Jake De Rosier

[Adapted for TheVintagent from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’]

Born in 1880 in eastern Quebec, Jacob de Rosier was a French Canadian, but his family soon moved to Massachusetts. His two-wheeled competition career began at age 14 as an amateur cyclist at Fall River, Mass., but his talent soon saw him re-designated a professional cyclist, and he pursued pedal power until 1898. That November, he spied the two motor tandems imported from France by Henri Fournier for use as pacers in cycle competition. Jake was immediately drawn to the powered cycles, and proved very good at managing these unwieldy devices. De Rosier was consequently selected as a steersman in the first motor-paced cycle event ever run in the US, held at Waltham, Mass. at the end of 1898, in which he paced the famous Harry Elkes. The advent of motor pacing revolutionized cycle sport in the US, as it had already done in Europe.

Operating a motor tandem was not for the faint of heart; keeping an internal combustion engine alive and spinning was a hands-full occupation for a dedicated mechanicién, while a the steersman kept the whole contraption pointed in the right direction. According to a January 1900 commentary on the new technology, "The experience of running a motor at 40 miles an hour is thrilling, and requires nerve, which is often found wanting if a 'chauffeur' should have ever experienced a fall”. The ability to ride or race a bicycle was no guarantee of skill at handling a motorized tandem.

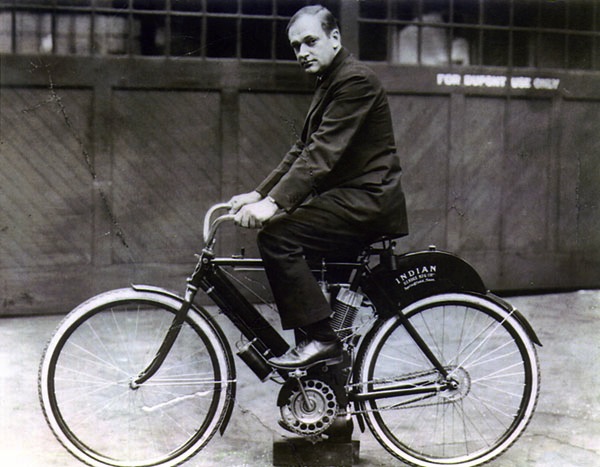

The Hendee Mfg. Co. hired de Rosier as a pacer-driver and a mechanic in 1901, but his employment lasted just a few months, and he continued his 'pacer' career for cyclists like Jimmy Michael until around 1905. The pacer crews at cycle races began to stage races with each other, in addition to supporting the bicycle competition. From 1905 de Rosier dropped the trailing cyclists and switched to motorcycle racing which was now gaining ground as a sport in its own right. As a result of various mishaps and spectacular get-offs it is said that, toward the end of the new century’s first decade, small and slightly-built De Rosier had not a patch of skin more than three inches square that had not yet been gouged, cut, bruised or torn. Of broken bones, multiple fractures and missing ribs there was now an extensive catalogue in his weighty medical file. His grit and determination to get to the top of this glamorous but dangerous new sport, and stay there, was evident in his conduct, his competitive spirit, and his refusal to be deterred by the prospect of further physical agonies or months-long spells of enforced idleness in a hospital bed. In the summer of 1908, Oscar Hedstrom presented de Rosier with a new experimental Indian to take away and test. It looked very different from Indian's first motor bicycles, the 'camel backs'. The new machine had a huge v-twin engine with scarcely any cylinder finning, slung low in a loop-frame rather than perched high in a bicycle frame. Jake spent his summer in New Jersey doing demonstration rides, setting national speed records on a cycle board track, and throwing down cash-purse match race challenges to other motor bicycle competitors. As a result of his successes on the prototype loop-frame racer, de Rosier was again hired by Indian, this time to be their official factory rider, becoming the world’s first professional salaried motorcycle racer.

He quickly repaid Hendee’s investment, with interest. By 1910 he held the US records for all distances from one to one hundred miles in the name of Indian. He was firmly established as the major star of US motorcycle racing, among a coterie of riders whose gladiatorial feats had greatly popularized the new sport and of whom it was said “They furnish excitement as thrilling as it is served in any form and cause one's blood to creep every minute they are in action”. Timber board tracks were now being established all over America by promoter Jack Prince. By early 1911 racing and record-breaking speeds in the USA soon climbed over 90 mph, undreamt-of and widely doubted in Britain where the mid-eighties was the best that anyone could yet manage. When Oscar Hedstrom decided that Indian should go all-out to be “third-time-lucky” and win the 1911 Isle of Man TT race, de Rosier was detailed to show the British what he could do. On arrival de Rosier was treated like a star and became the centre of a media circus; everywhere he stopped, crowds gathered to see and meet him, and his magnetic personality, and modesty about his riding ability, charmed the English and he became very popular.

In the TT itself de Rosier struggled, riding valiantly but clearly not comfortable on the rough and loose surfaces of the IoM’s gravel roads. He was leading the race at the end of the first lap, but had crashes and then accepted outside help which disqualified him. Yet he managed to ride the full distance. It was the British Indian riders who secured the 1-2-3 placings, after Charlie Collier of Matchless lost his own 2nd placing due to disqualification for re-fuelling at an unauthorized stop. The next day, de Rosier stunned the crowds by winning several sprints held down the narrow and curved Douglas Promenade, in windy and slippery conditions, at 75mph. De Rosier had brought with him “Number 21”, the 1,000cc Indian upon which he’d set all his current US records.

He was looking for match races and he found them, for it was arranged that he should have a Best-of-Three with English champion Charlie Collier (builder/rider of Matchless motorcycles) for a purse of £130. This was held at Brooklands Track near London, and the first race was won by de Rosier who slip-streamed Collier and then dashed past in the final instant. In the second race Collier led, and won because de Rosier’s front tyre came off at high speed. Yet Jake didn’t drop the bike, and he motored it back on the bare steel rim. The spectators were astonished by his skill. In the final race Collier again led, until his spark plug wire came loose. While struggling to hold it on with his bare hands, de Rosier came past to win. Before leaving England, de Rosier also broke the existing British one-mile and one-km speed records. But Charlie Collier had the final word after Jake had departed, for Collier next got his Matchless machine to take back all Jake’s records just set and he also became the first man in Britain to exceed 90mph.

Back in the USA, Jake soon fell out with Indian's Board for reasons that are still not clear. For some reason, de Rosier was not presented with one of the new Indian eight-valve racers, which had been released while he was away in England. As a result, Jake joined the race team of Chicago firm Excelsior. But he soon had other problems. A new Excelsior rider named Joe Wolters burst onto the scene and started breaking all of Jake’s US records. Other too, like Erle Armstrong, found that the French Canadian was no longer unbeatable. Newspapers began referring to him in race reports as “the former champion” and “the old war-horse”. In February 1912 Jake and the Excelsior team went out west to compete in events at the newly-opened L.A. Stadium saucer board-track. Promoters played up race duels between de Rosier and Charles “Fearless” Balke as crowd-pleasing grudge matches. It was in one of these that a mistake by Balke saw both bikes go down and, locked together, they dragged their riders along for almost 500 feet. Balke was okay, but de Rosier’s left leg was broken in three places. He underwent surgery to pin everything back together, and then rested for a good many weeks, before further surgery and weeks of bed-rest, and by the time he was able to return home to Springfield Mass, all his savings had been spent on medical bills. As his leg had not healed properly, in February 1913 de Rosier entered hospital for yet another round of surgery. It didn’t go well, and he died on 25 February 1913. As de Rosier was quite famous in Springfield, home of the Indian Motocycle Co., his funeral cortege wound through the town, and as it passed, all work at the Indian factory ceased, and their flag was lowered to half mast. Ocscar Hedstrom tendered his resignation from Indian that very day, for reasons which have never been explained.

[Adapted from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’, by Timothy Pickering, Chris Smith, Harry V. Sucher, Liam Diamond, and Harry Havelin, available here]

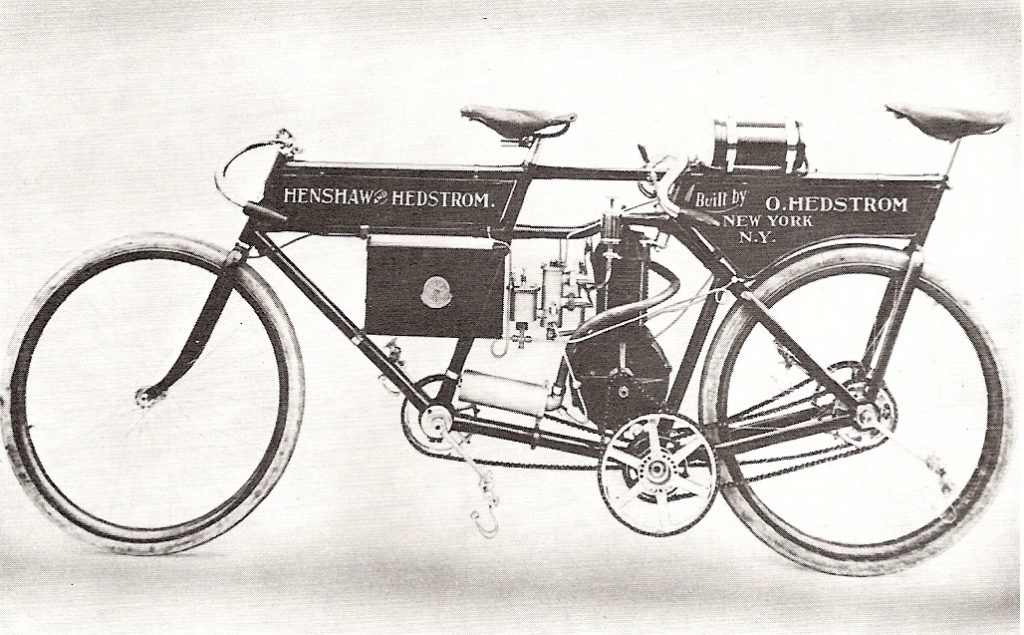

100 Years After the 'Indian Summer', Part 1: Billy Wells

[Adapted for TheVintagent from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’]

William Huntingdon 'Billy' Wells was born in Winthrop, Maine, on 28 March 1868. As a young man he was a keen bicycling competitor, in those days, before the invention of the 'safety bicycle', he raced dangerous 'high-wheel' cycles, which used enormous front wheels before chain-drive made multiple gears possible. Wells began working as a bicycle builder in 1884, around the time the 'safety' bicycle was invented - setting the two-wheel pattern we still recognize today.

In late 1902 he moved to England as an agent for the steam-powered automobile the 'Stanley Steamer'. The car was not a commercial success, and Wells switched to importing German-made Allright/Lito motorcycles which he marketed in Britain as the 'Vindec Special'. With bicycle competition in his blood, he modified a few Vindecs for competition, some with Peugeot 1,000cc v-twin engines, and gained a reputation for winning in hill-climbs and reliability trials. Wells entered the inaugural 1907 Isle of Man TT race on a Vindec twin, and was leading the race comfortably until the last lap when he had three punctures in quick succession. It was while repairing the third puncture that Rembrandt Fowler on a Norton went past him to win the twin cylinder class of the first ever TT. He regretted ever after not winning the race, and history might have looked slightly different had an American won the first TT! Wells' import company, South British Trading Ltd, went into liquidation after 5 years in business, and with no immediate prospects in England, Wells returned to the USA in March 1909. He happened to meet an old friend from his bicycle competition days, George Hendee, who had commenced manufacture of motor bicycles under the brand name of 'Indian'.

Hendee urged Wells to immediately return to England and set up an Indian marketing, sales and service organization for all of Britain, her colonies, and Europe. Hendee termed this entity a 'branch office' of the Hendee Mfg. Co. Ltd. Thus, the Indian depot in London opened for business in May 1909 at 178 Great Portland Street, in the West End close to fashionable Oxford Street and Soho. Launching an extensive sales campaign, Wells worked hard to set up a dealership network in Britain. Always keen on competition, he began offering Indians to top British racers for events at Brooklands and the Isle of Man TT. Billy Wells and Guy Lee Evans entered the 1909 Senior TT on Indian twins. Wells crashed at or very near the start, and was injured. Evans rode a heck of a race and, after the faster of the two famous Collier brothers (Charlie) was forced to retire, Harry Collier had to dig deep and try every trick he knew to stay in front. Harry managed to bring his Matchless twin to the finish line just a minute or two ahead of Evans. It was a thriller of a race.

The 1910 TT was expected to be a repeat of the excitement in 1909. Indian chief designer Oscar Hedstrom came over from the US to observe. Wells did not ride but entered an official Indian team of Lee Evans, Charlie Bennett, and Walter Bentley (later famous as “W.O.” of Bentley cars). Entrants on privately-owned Indians included Arthur Moorhouse, Jimmy Alexander from Scotland and Charles B. Franklin from Ireland, all new converts to Indian. But a faulty batch of tire innertubes saw them all drop out, or crash spectacularly from blow-outs. The Collier brothers won easily. The 'Indian Spring' was dismal, although Indians did very well at other events during the year. The high point of Wells' career was the 1911 TT when, again as Team Manager (with Hedstrom also returning as Technical Advisor) he entered a five-man factory team of star American track specialist Jake de Rosier, along with experienced British IoM riders Moorhouse, Alexander, Oliver Godfrey and Charlie Franklin. The combination of their skilled riding and the fact that Indians used chains/gears/clutches over the new 'Mountain Course' at the TT, meant Indians took an unprecedented 1-2-3 in the Senior TT.

In recognition of his efforts to boost Indian export sales, Wells was made a member of the Hendee Mfg. Co.'s Board of Directors in 1911, a position he held until the company was reorganized and renamed as the Indian Motocycle Company in November 1923. In 1914 Wells recruited Charles B. Franklin to Indian as manager of a newly-opened Dublin Indian depot. Business was slow with Europe at war, and the depot was closed down again in 1916, and Indian board president Hendee imported Franklin (a trained engineer) to Springfield on Wells’ recommendation, to start a job in the Design Department of Indian. Wells’ recommendation had major implications for Indian’s future, for it was Franklin who designed the immortal Indian Scout and Chief models.

After WWI Wells supported further Indian entries in the TT, and was successful in gaining 2nd and 3rd placings. But a decreasing volume of Indian business in UK made the effort of racing at this level difficult for him to justify beyond 1923, when Freddie Dixon made 3rd place at the TT on his single-cylinder 500cc Indian. By 1925, international trade protectionism meant a 33% tax levied on imported motorcycles in the UK, significantly raising the price of his Indians during an already rough period of the British economy, and Wells was forced to shut down his British Indian operation. Out of work again and deeply depressed, but started a motoring accessory business. In 1928 Wells was approached by entrepreneurs who wanted his help to introduce 'dirt-track' (later Speedway) racing to Britain, which had proved wildly popular in Australia. Ever the team manager, Billy Wells became Secretary of Meetings and Clerk of the Course of Stamford Bridge Speedway Track, organizing the first big speedway event at night under electric floodlights. The experiment worked, and the new sport became hugely popular, and profitable, in Britain from then on, with paying customers in the tens of thousands. He was by then in his mid-60s, so returned to his first love in semi-retirement, working from home as a bicycle repairer.

Wells passed away in Harrow, England on 15 January 1954, a pivotal figure in Indian’s international sales success and the architect of Indian’s finest international sporting achievement, the 1-2-3 clean-sweep of the 1911 Isle of Man Senior TT.

[Adapted from the book 'Franklin's Indians', by Timothy Pickering, Chris Smith, Harry V. Sucher, Liam Diamond, and Harry Havelin, available here.]

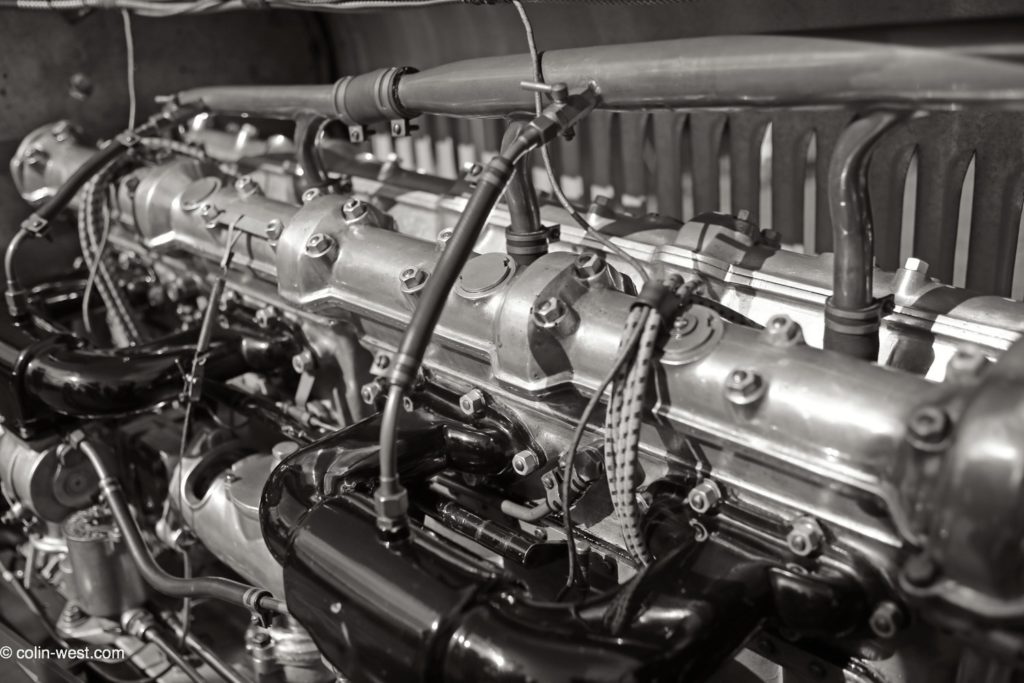

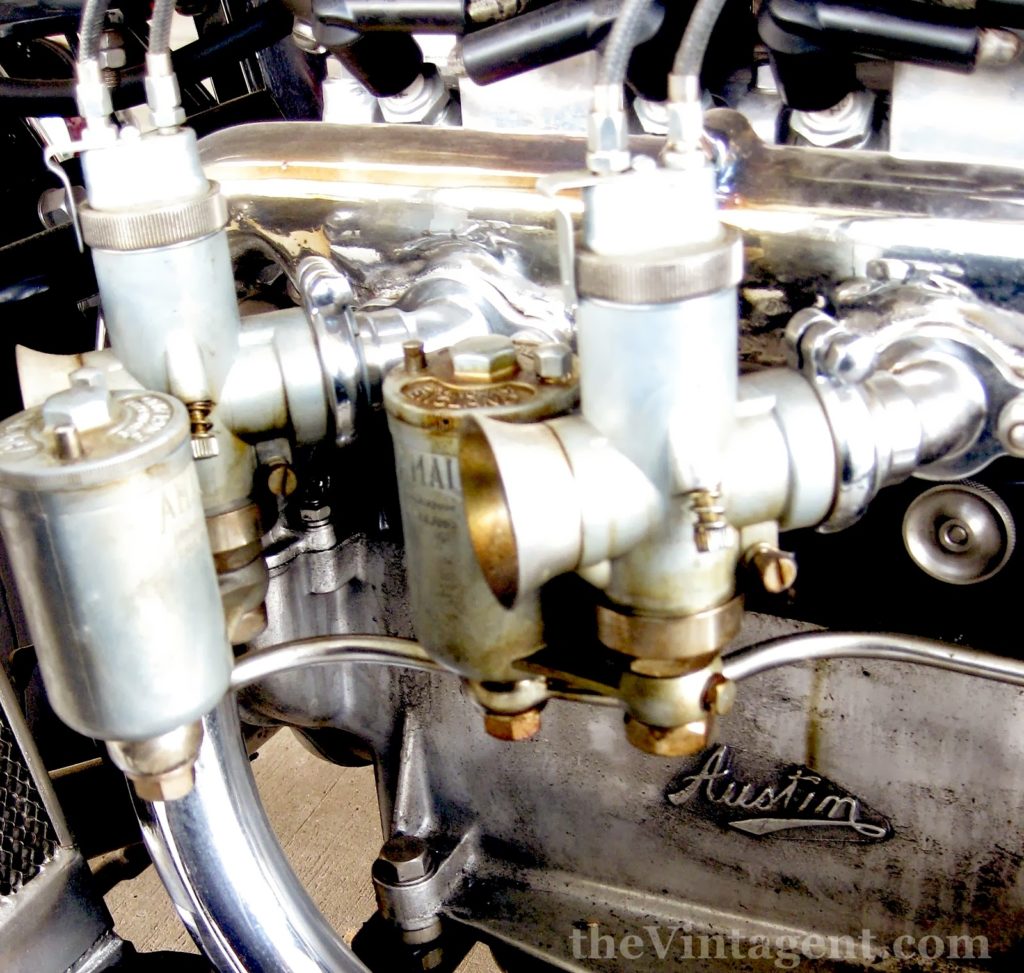

Road Test: 1930 Brough Superior-Austin Four

The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world's rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

A large collection of old motorcycles is often a depressing sight; the usual scenario is rows of desirable machines, which could best give pleasure if taken out on the road, yet are left to gather dust like a Chinese warrior army, holed up in someone's barn or warehouse, waiting for Godot...

So, now it's my turn. First, familiarize self with gearchange, which is a car shift turned to face forward - a strange pattern, but it makes sense once the beast is underway. Second, familiarize myself the the brakes... and I know from experience that the front is no 'stopper' - totally useless. The rear brake with 'BS' cast into the pedal is more reassuring, and hauls the heavy (700lbs?) four-wheeler down rapidly. Third, where the hell is the throttle? Indian-style, it's on the left 'bar, which will take a moment of getting used to, especially as the clutch lever is next to it. Luckily, there's a foot clutch as well, which becomes my preferred device - too akward to feather the clutch and open the throttle with one hand.

Curious about the ride? Take a spin yourself:

I can say, hand on heart, that this is the nicest motorcycle pulling a sidecar that I've ever ridden, and I've ridden all manner of outfits; German, English, Yank, Jap. There is a feeling of tireless solidity about the machine, the engine just feels very right, the handling is, well, Superior. George Brough was a great advocate and rider of sidecar machines, and all of his bikes work well pulling a mate, but this one is better. I'm not sure one can pinpoint exactly what makes it so good, but it is, for all of the novelty and rarity, an incredibly relaxing motorcycle to ride. There's no point in hurrying, as the ride itself is the point, and I think I just called this Brough Superior a Zen motorcycle. My expectations were completely overturned... unlike the outfit...

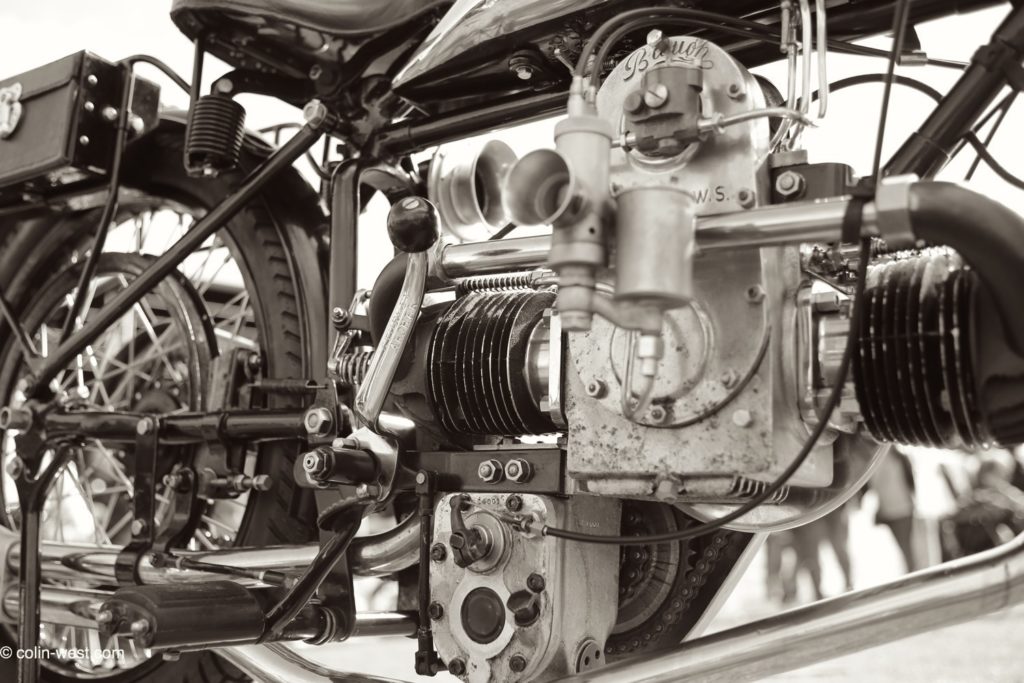

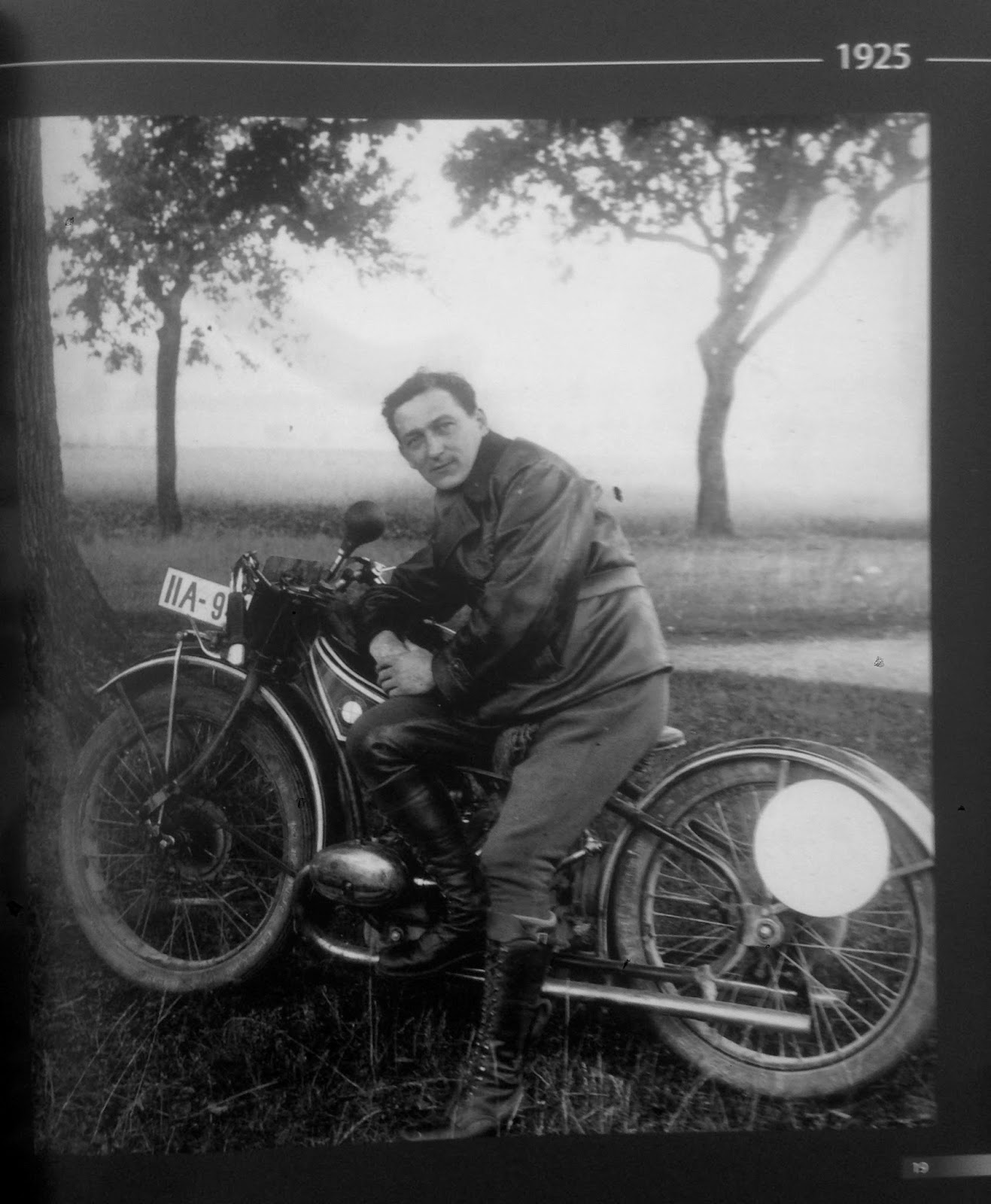

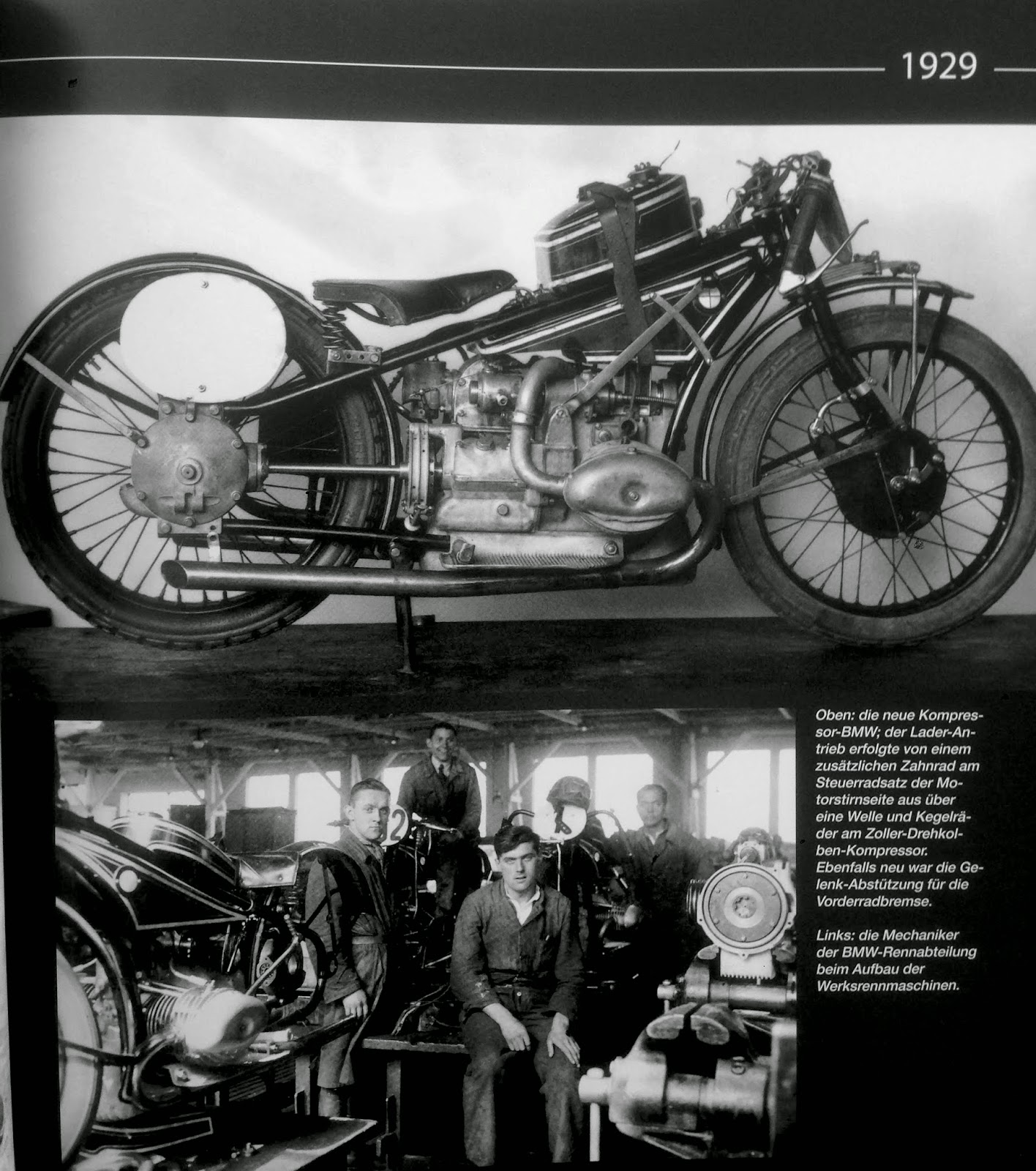

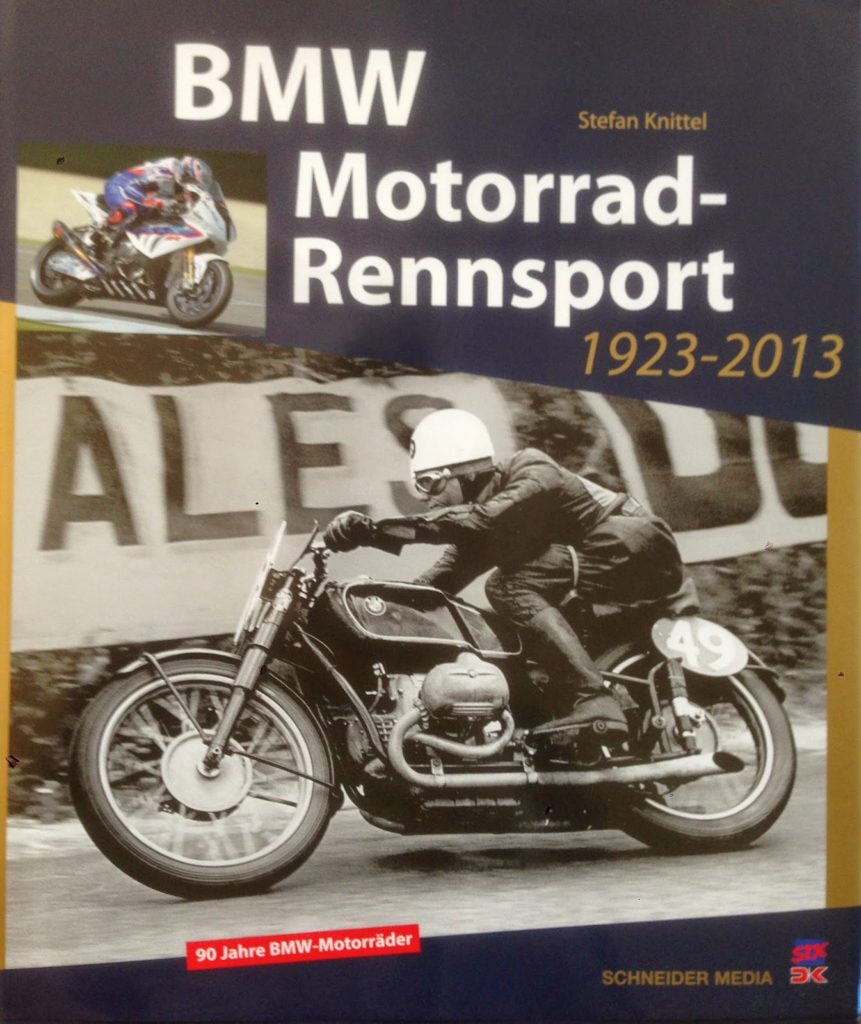

Book Review: 'BMW Rennsport'

Author Stefan Knittel has literally 'written the book' on BMWs (among other marques), and has developed a close relationship with that factory's archive. No-one is better placed to assemble a book of historic BMW motorcycle racing photographs from the factory's own files, and for BMW's 90th anniversary, Schneider Media UK Ltd commissioned a book documenting the full history of BMW on and off-road racing machines.

'BMW Motorrad-Rennsport: 1929-2013' has over 600 photos, many of which you've never seen before, and most of which are simply friggen' awesome. I think it's fair to say that BMW has supported more types of motorcycle racing over a longer period than any other brand in history, from the GP circuits of Europe on two and 3 wheels, the record-breaking autobahns of Germany, the muddy trials courses of the ISDT, and the sands of Africa in the grueling Paris-Dakar races. They were pioneers of supercharging in the late 1920s, and photos of all the blown bikes are included here, from the first pushrod 750s to the last national-championship OHC machines of 1950, when BMW was banned from international racing, so kept using their RS Kompressor racers, because they could (supercharged racers were used in off-road competition too, pre-War).

While competing in so many fields, BMW built dozens of wickedly cool one-off bikes; dirt bikes, streamliners, road racers, concept machines, sidecars, etc. All of them are idiosyncratic, devastatingly functional, and stylistically unique, and usually quite beautiful. The book is crammed with rare images of these amazing machines, including later-era stuff we vintagents didn't even know existed!

OK, the bad news, it's in German only at this point. But you really only wanted the pictures, right? Order here from Schneider Media, it's 49 euros plus shipping. Totally worth it.

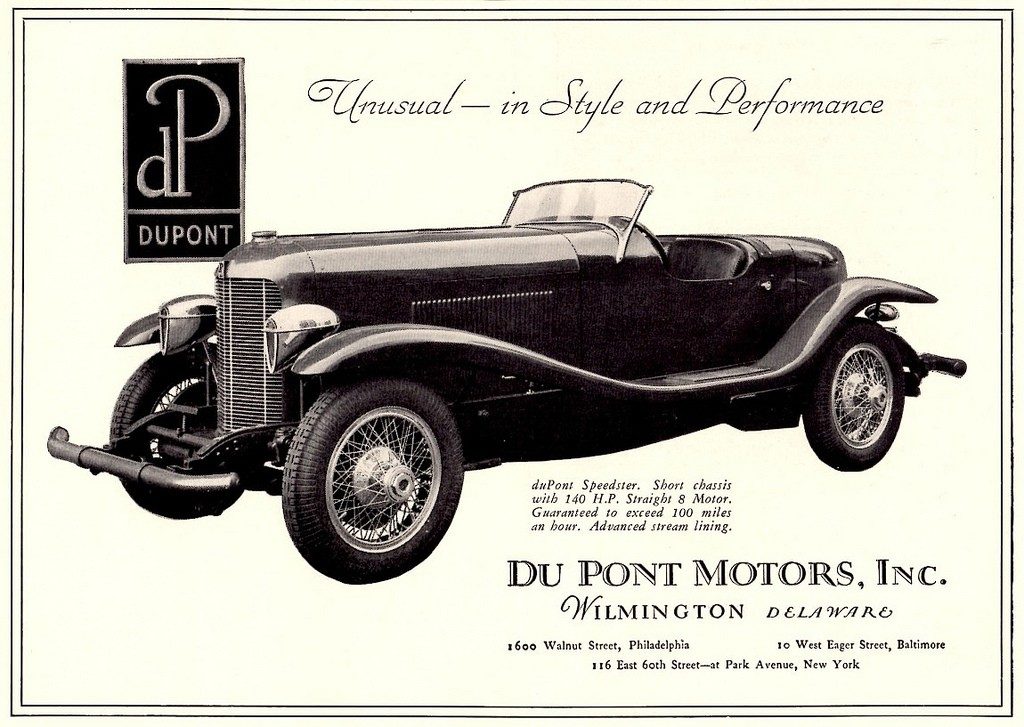

The Motorcycling Du Ponts

Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours was born a Parisian in 1771, of a family soon to be granted a noble title by Louis XVI (in 1784). The du Ponts, especially father Pierre Samuel, had close ties to the government of France but were advocates of reform to the country's finances, which were heading rapidly towards bankruptcy after the French, to spite the English, heavily funded the American colonists' rebellion. The French Revolution of 1789 saw many reform-minded aristocrats such as the du Ponts (many of whom were members of Masonic clubs advocating democratic change) elevated to important positions. Pierre Samuel was even President of the National Constituent Assembly, and added 'de Nemours' to the family name to distinguish himself from other du Ponts in the new government.

Tension between radical Jacobins and moderate aristocrats, both seekers of change, became increasingly focused on class distinction, and many nobles lost the titular d' or du or de appending their surname, bowing to the fashion for 'egalité', and an increasingly hostile atmosphere towards inherited titles. For Pierre Samuel, his physical defense of King Louis and Marie Antoinette from a bloodthirsty mob in 1792 culminated in imprisonment by 1794, which meant the guillotine for any aristocrat, and thousands of others put to a defense-less trial, or no trial at all. But, as 'revolutions eat their heroes', the beheading of Maximilian Robespierre later that year meant du Pont and his family survived, but the continuing political and economic turmoil of the Directoire period (1795-99), plus the sacking of their home by a mob, saw the du Ponts sailing for America in 1799.

Éleuthére had worked with the renowned French chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (before he was condemned with "The Republic needs neither scientists nor chemists", and beheaded in 1794) at the Paris Arsenal, gaining expertise in gunpowder and nitrate extraction/manufacture, which would play a huge role in the family's development of nitrocellulose lacquers, and 'smokeless' gunpowder, in the US. The family intended to create a French cultural community in Maine, but a hunting trip with a US military gunpowder procurer (and former French officer, Louis de Tousard) demonstrated the inferior quality of American black powder. Éleuthére's expertise in the manufacture of gunpowder led the family to invest heavily ($84,000 in 1802) in the creation of E.I.du Pont de Nemours and Co., or simply DuPont, in the Brandywine Valley of Delaware.

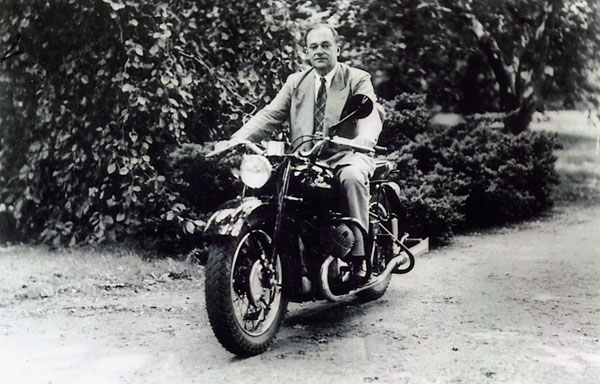

Subsequent generations of du Ponts arranged inter-marriage to cousins, keeping their rapidly expanding wealth, and family control of their business, close at hand. The Du Pont corporation grew into the world's third largest chemical company, inventing things like nylon and kevlar and neoprene. As their wealth exploded, du Pont family members invested in many other areas, including, for a time, automobile (Pierre du Pont was president of General Motors in 1920) and motorcycle manufacture.

The family dabbled in making DuPont automobiles of their own starting in 1919, when E.Paul du Pont, a lifelong tinkerer and 'gearhead', grew from making marine engines for the US WW1 effort, to full automobiles. As only around 600 DuPonts were made in the 12 years of the company's existence, it was clearly never going to be an enormous success, especially after the stock market crash of 1929. E.Paul's brother Frances had invested $300,000 (in 1923) in the Hendee Mf'g Co., makers of Indian motocycles, and Indian's near-bankruptcy in 1930 meant the family was likely to lose a substantial investment. E.Paul merged DuPont Motors with Hendee in 1930, deciding in '31 to drop autos completely, and concentrate on making Indians.

As the new president of Indian, E.Paul made significant changes; as a lifelong motorcyclist (having built his first clip-on moped as a teen, then owned an early Indian 'Camelback'), he felt the days of motorcycles as utilitarian vehicles were over, and embraced the idea of a motorcycle as 'leisure object'.

To support this view, the company focused on three areas: the new production-based 'Class C' racing in the US, the DuPont Company's huge automotive paint color palette, and the styling of Briggs Weaver. DuPont pioneered fast-drying nitrocellulose lacquer auto paint in the early 1920s, and suddenly brilliant colors were no longer a hindrance to manufacture, as previously only black paint would dry quickly enough for economical manufacture (Henry Ford's famous 'any color as long as it's black' was a practical dictum - only black paint dried quickly). Thus, Indian motocycles were shortly available in 24 different, brilliant colors, while their sheet metal grew more elaborate and Art Deco-inspired, and their racing team grew increasingly successful (E.Paul's son Steven was an engineer and helped developed the 'Big Base' racing Scout).

By 1938, Indian had gone from losing hundreds of thousand of dollars per year, to amassing huge profits with their beautiful and iconic motorcycles - the Chief and Scout. Briggs Weaver's styling of these models remains emblematic of Indian's identity; the deeply skirted Deco fenders and Indian-head motifs are still our first image of Indians today, and the brand identity of every subsequent revival of the Indian marque in modern times. As WW2 approached, riders smelling an upcoming war bought out the company's production, before civilian production stopped, and the factory concentrated on building motorcycles for the US military. The immediate pre-war period was the peak of Indian's profitability, but E.Paul Du Pont's health was declining, and the profitable Indian factory was very attractive to investors. In 1945 Indian was sold to an investment group headed by Ralph B. Rogers.

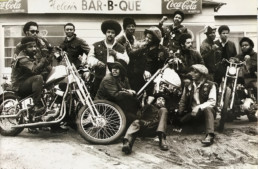

'Black Chrome'

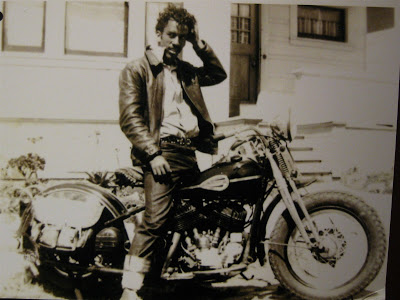

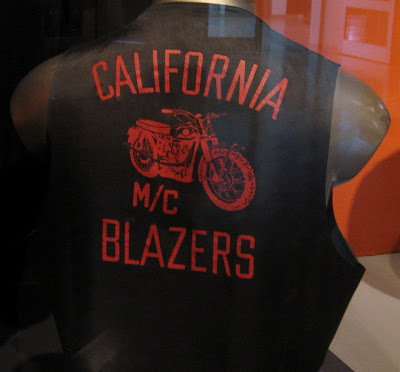

The California African American Museum in LA hosts 'Black Chrome', an exhibit featuring black motorcyclists, their bikes, and a bit of history (through April 12th, 2009). I managed to catch it last weekend - the show is poorly advertised in the motorcycle community, and only a chance google result raised the website of the museum, which sits next to the LA Coliseum (and its stunning Robert Graham headless nude man/woman statues, which caused such controversy at the 1984 LA Olympics). The museum complex also includes an Aerospace Hall, with an SR-71 'Blackbird' plane outside - amazing.

'Black Chrome' (gotta love the name) is a mixed bag of a show - a superlative and long overdue concept, with a few real gems, but on the whole it lacks the depth needed to make a statement about motorcyclists 'of color'. The gems; I never knew that the builder of those seminal choppers in Easy Rider, Ben Hardy, is black! A claim is made that the whole extended fork style of custom motorcycle was created by Black rider/artisans - take that, nazi bikers! It all makes sense of course - who invented the 'look' and sound of Rock music, who created Jazz and Blues, who started the trend for outrageous stage outfits/antics which were parroted and expropriated by everyone else? Okay, I'm done.

But, this tidbit of information is presented on a 8" square card, between two 'Easy Rider' posters. I'm not sure if the curators really appreciate the significance of this nugget of information, and the exhibit strikes me as curious for its lack of a catalog or much background information at all. Someone is either completely unfunded, or isn't really savvy to the impact a show such as this could/should have on popular culture. They are aware, however, of the popularity of the Chopper craze, as quite a few bikes on display are new OCC-style bikes.

A Discovery Channel video on the History of the Chopper (a Jesse James project), on continuous loop, does explore the exclusion of Black riders from Chopper magazines In The Day. The video also allows 'Sugar Bear' to explain his own history of building custom bikes since the 1960's, and most significantly, mention is made of photographs of Black choppers dating back to the 1950s... and you can bet The Vintagent will pay this man a visit!

The period photos in 'Black Chrome' poorly reproduced, displayed, and explained - they speak volumes, but I truly wish the curators had spent more time exploring a world most of us don't know. Where's the sholarship on the subject? I guess it's here - hire me folks, I write cheap. The photo above is Esvan Mosky, with his dog Koo Koo Man, on their modified BMW /2 tourer - Esvan was in show business somehow, but I'd like to learn more about this intriguing fellow.

Images of women riders are included, with a brief mention of Bessie Stringfield, founder of the Motor Maids, and a few words that women had their own motorcycles within the riding clubs, then and now. More please.

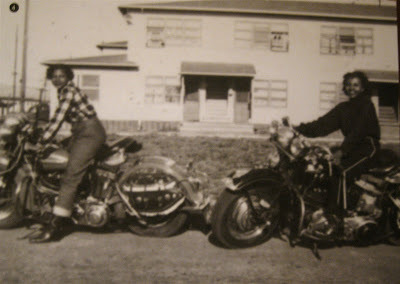

Gang and Club 'colors' are prominently displayed, including the East Bay Dragons, a still-active group I see on the road at times. Their Drag Bike (see photos) is perhaps only intact as it had a rather serious 'issue' with the crankcases during a sprint. Oops. I love that it is presented 'as is'! Unfortunately, a 1960s Sportster is also presented thus (ie, incomplete) with no good reason other than to fill space. A nice orange metalflake Panhead makes sense, as does a beautifully pinstriped Sportster named 'My Man', owned by a woman.

My favorite Club jacket - the 'California Blazers M/C' (above); aesthetically uninspired, barring the late-model Velocette Scrambler used as their logo...cool.

[The black/white period photographs from the 'Black Chrome' exhibit are used here by kind permission of Na'il 'Shayk' Karim, publisher of The Black Biker magazine and Breezin on Two Wheels. Shayk painstakingly collected these photographs from family members of the subjects, and the photos were licensed exclusively to Shayk.]

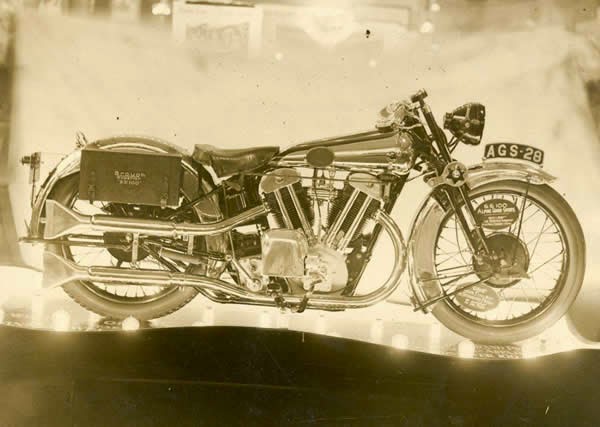

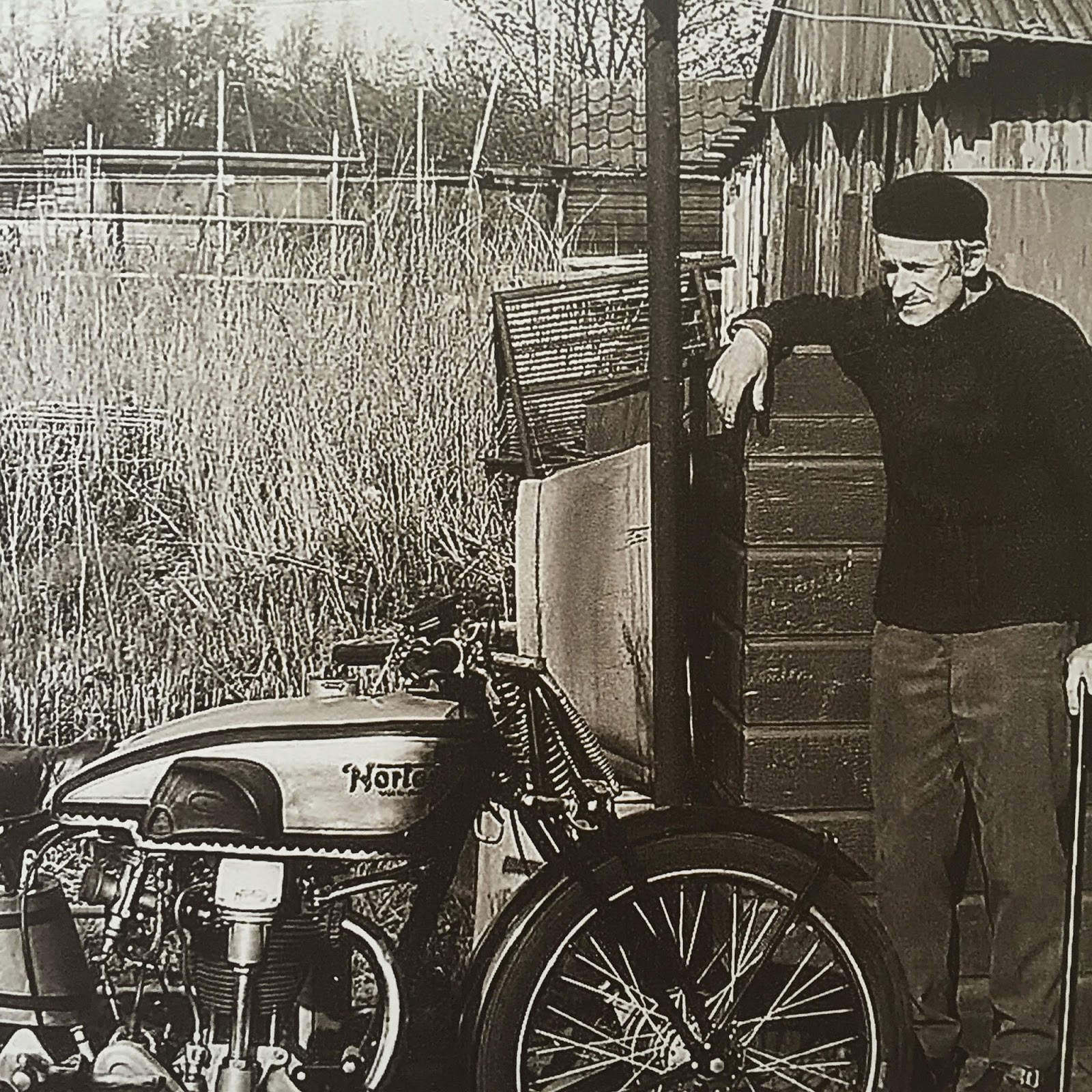

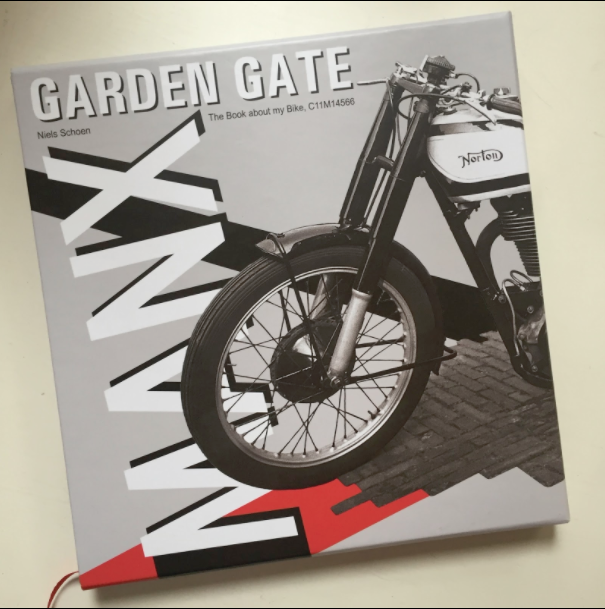

Book Review: Garden Gate Manx

A host of terrific motorcycle books cross my desk every year; in this I'm very lucky, as books are one of life's great pleasures. Books are also the foundation of TheVintagent, along with decades' experience with vintage machinery, and not web-search content - long may it remain so. I write books too, and contributed this year to 'The Ride: 2nd Gear' from Gestalten, who published my magnum opus on choppers last year, 'The Chopper; the Real Story'. And while I reviewed 'The Ride: 2nd Gear' on CycleWorld.com, there's a solo effort you won't find in any bookstore which absolutely blew my mind this year.

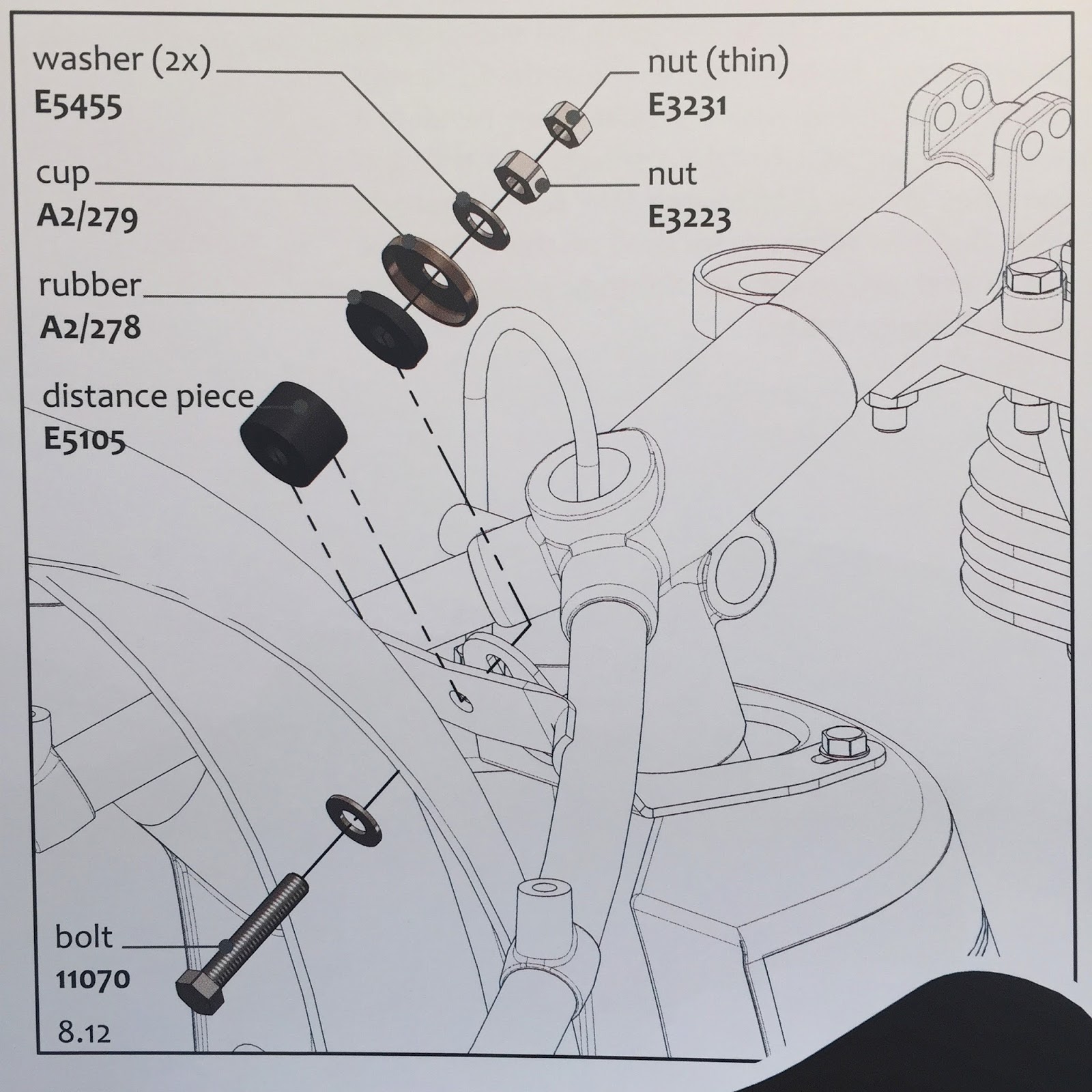

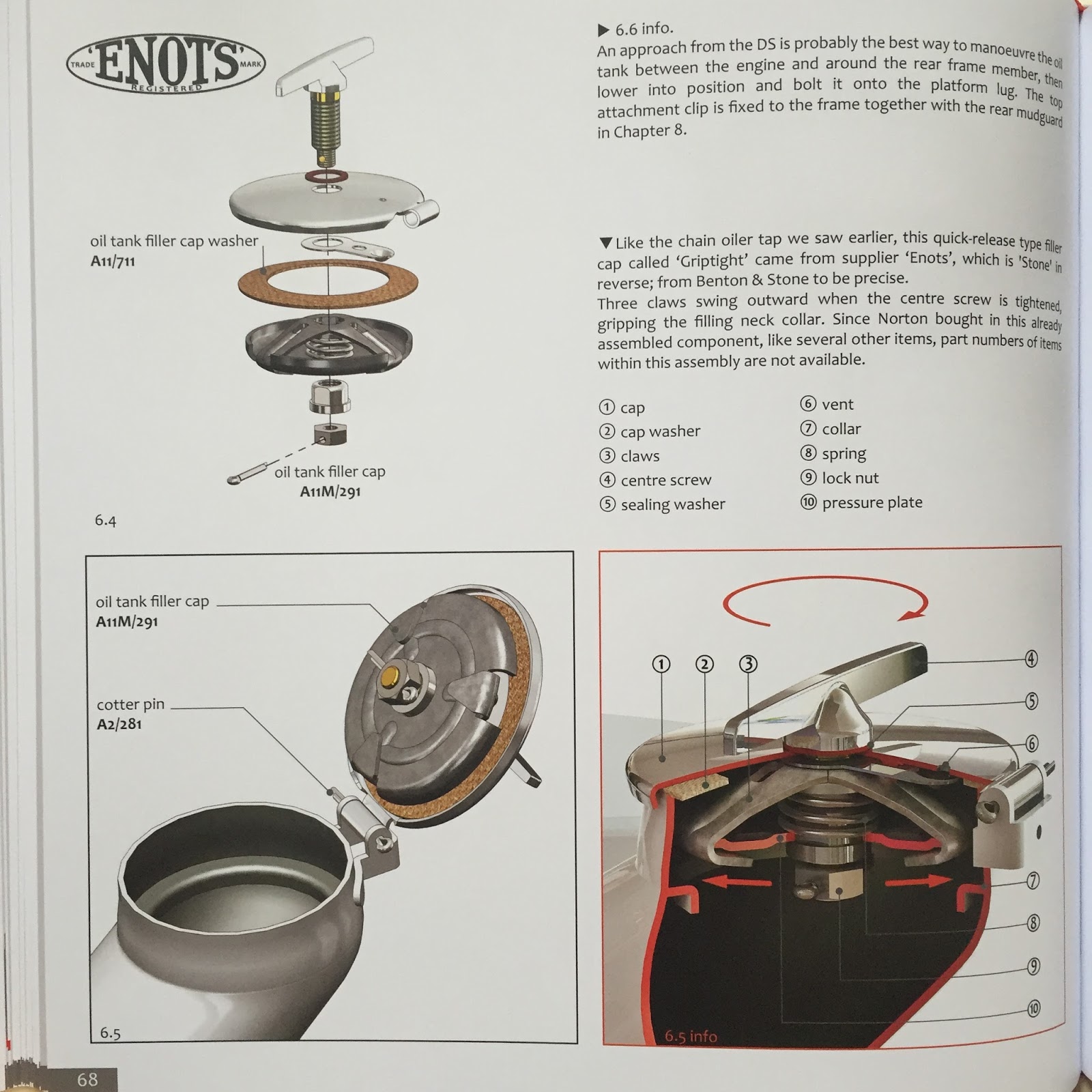

It's called 'The Book About My Bike, C11M14566', and I know - the un-sexiest motorbook title ever. I was merely geek-interested when Niels Schoen offered to send his self-published book about Uncle Ko's Garden Gate Manx, which he inherited and restored. But Niels is a freelance CAD-engineer, and while taking his uncle's Manx to bits, he thought it 'a good training exercise' to render every single part of the Manx in the SolidWorks program, so the bike could be dis/reassembled virtually while the same was happening in his living room. Niels lives in a 4-storey walkup in Rotterdam, and has no workshop, so the disassembly, scanning, cleaning, and reassembly was done literally in-house.

Scanning and rendering over 800 parts took 9 months, and was completed in September 2010. It took a further few years to figure out 'how to present and share all the oddities, the beauty and the marvels I encountered in the process.' He took inspiration from Mick Walker's 'Manx Norton' book of 1990, as well as an original 1948 Norton advertisement featuring the Garden Gate Manx. The resulting layout is impeccable, as is the information; every exploded view of a parts assembly is accompanied by the relevant part numbers, and labeled according to Norton's original nomenclature. The text is a mix of family history, Norton lore, and straight-ahead explanation of what's shown. The book is, in sum, the best parts list/assembly manual ever devised for a motorcycle. It's the manual every confused motorcyclist wishes for; an absolutely clear view of how it all fits together, so brilliantly self-explanatory it makes a Haynes manual look utterly primitive.

I understand it's far too much work to create such a manual for every motorcycle, but I'm jealous there isn't such a book for all my motorcycles. And for, say, a Velocette Mk8 KTT or Brough Superior SS100 for some fascinating entertainment. Niels Schoen isn't the only person to have rendered every single part of a motorcycle; Uwe Ehinger has done the same for most Harley-Davidsons ever built, and anyone making replicas (or 'continuations') today is no doubt using SolidWorks to render their parts as well. After building an actual motorcycle, I can't imagine a better use for all that information, than to share it with the world as Schoen has. It's a first-class integration of the very modern with the vintage, the new in service of the old. I laud his accomplishment; may it serve as an example for others.

The only way to order 'The Book About My Bike' is directly from Niels Schoen. He has a FaceBook page (https://www.facebook.com/GGMbook) and to order, send an email to Niels direct (newstep3d@gmail.com) with your mailing address and preferred payment method (IBAN or PayPal), and he'll sort you out.

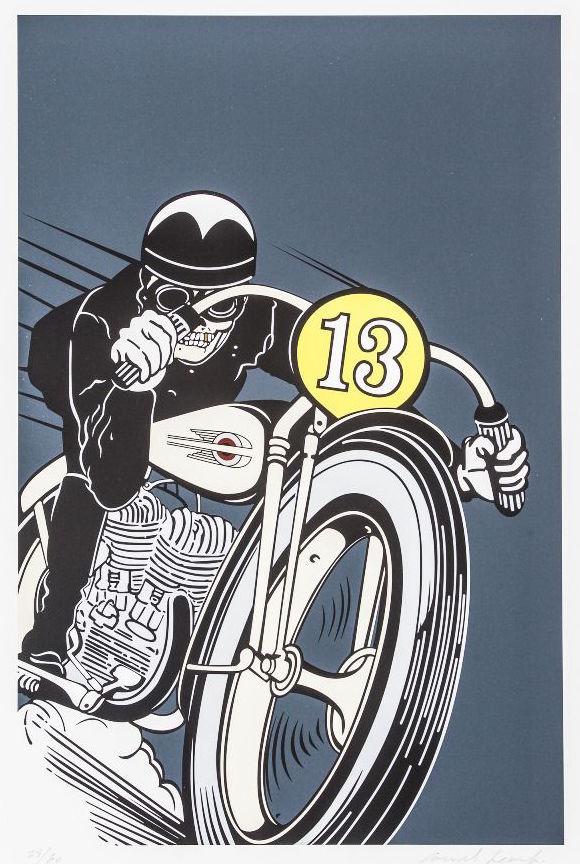

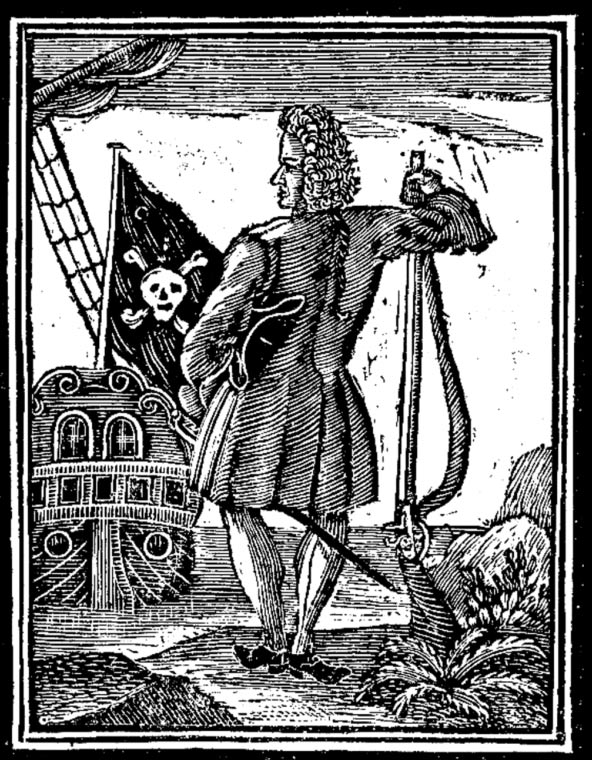

The Skull and Crossbones

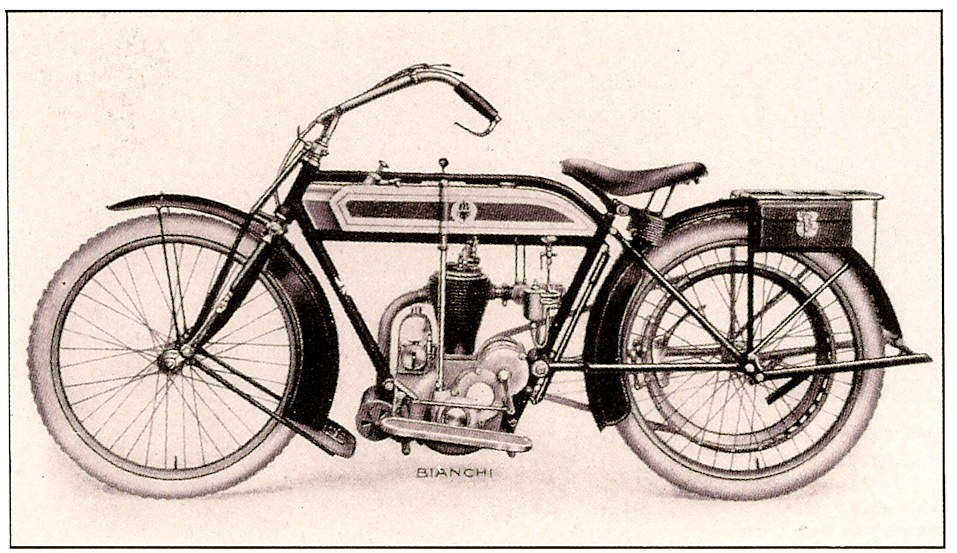

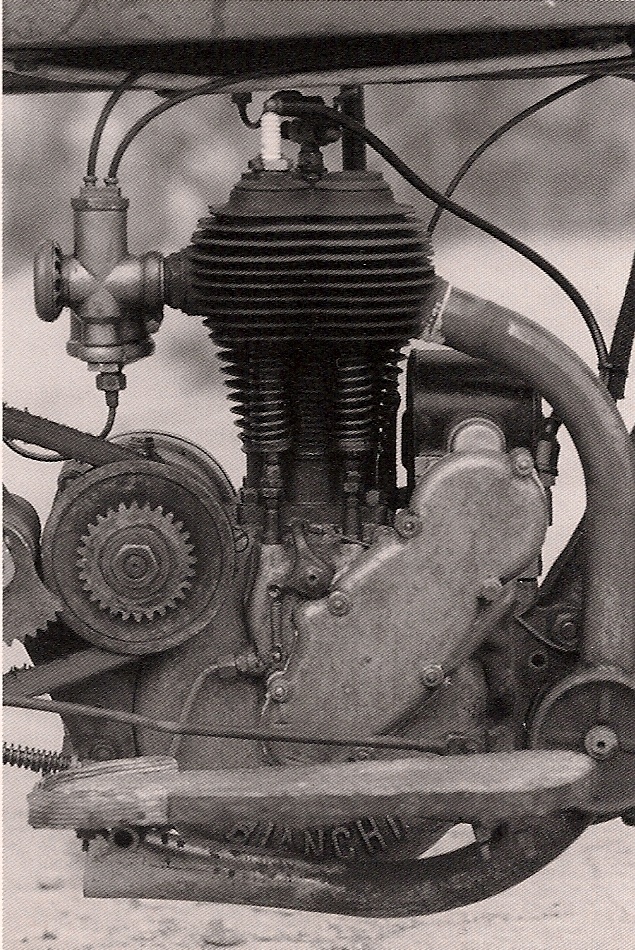

Perusing Aldo Carrer's excellent book 'The Motorcycle Uniform During the World War One' (Zanetti, 2008), I was struck by this image: does this photograph show the first instance of a 'skull and crossbones' (or Jolly Roger) on a motorcyclist's outfit? The photo was taken in Italy during WWI, and shows 'Renzo' on a Bianchi Model 500A. Renzo ("waiting for action" it says on the back of the photo) was an Ardito (literally - 'audacious man'); the Arditi were the equivalent of Special Forces in the Italian Royal Army, created during a difficult period during the War for a specific job - to break a stalemate on the entrenched Italian Front. They were specially trained as an elite unit, with (according to 'Italian Arditi') "special recruitment procedures, training, arms, uniforms, priveleges, and benefits. For the first time, an Italian soldier was given concentrated, specific training, both psychological and physical; the Ardito also received the best available equipment and enjoyed superior living conditions. In order to counter the high casualty rate (!)... esprit de corps was very important..particular attention was focussed on comraderie and attitude, in order to motivtate the men and help them bear the psychological stress involved."

Regarding the history of the skull and crossbones; there is evidence it originated on the flag of Roger II of Sicily (1095-1124), a sponsor of the Knights Templar. After the Knights were disbanded, former Templars flew Roger's flag when pirating at sea. In the 1700s, the 'totenkopf' (death's head) became very popular, and was used in an official capacity by von Ruesch's Hussar Regiment #5 of the Prussian army. In the same era, the 'Jolly Roger' was adopted by pirates, privateers, and corsairs plying the world's oceans, and the first citation of sighting the 'Jolly Roger' was in 1724, in Charles Johnson's 'A General History of the Pyrates').

The Jolly Roger has been utilized by 'bikers' in the twentieth century for the same purpose - as a 'memento mori' (reminder of mortality), and to signify 'no fear' of death. The image has been modified in a thousand ways since this first, simple logo on Renzo's riding outfit, but the message remains the same; don't mess with me.

The motorcycle is a Bianchi Model 500 A, a 498cc sidevalve single-cylinder machine with a short-leading-link front fork (see patent drawing from Jan 19th, 1915), a Bosch magneto, and Zenith carb. This was Bianchi's mainstay model, introduced in 1916, which dates the pic of Renzo between 1916-18, as the Arditi were disbanded after WW1.

The Bianchi used a cone clutch inside the unitary engine casting, plus a kickstarter and a geared primary drive, all very advanced for 1915, although the final drive is still a single-speed belt. While similar in profile to the ubiquitous Triumph used by English despatch riders during WW1, the Bianchi is a better-engineered machine - the clutch alone makes for a far more useful motorcycle.

The photograph of Renzo can be found in Aldo Carrer's amazing book 'The Motorcycle Uniform During the World War One' (Zanetti, 2008), which can be ordered (and his previous effort, 'The Dawn of the Motorcycle') from Aldo directly here.

The Bianchi motorcycle photos are from 'Eduardo Bianchi' (Gentile, NADA, 1992), which is a lovely book in English/Italian.

The photo of the Arditos (knives raised!) is from 'Italian Arditi: Elite Assault Troops 1917-20' (Angelo Pirocchi, Osprey, 2008). As a further note, many of the Arditi joined Fascist paramilitary units just four years after WW1, to support Mussolini's rise to power. They were created about the same time as the Austro-Hungarian and German armies founded the Sturmtruppen - not a very romantic outcome.

For more information on pirates, I recommend 'Under the Black Flag; the Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates' (Cordingly, Harvest, 1995), which is the best book I've found on the subject.

The Alt.Custom Scene - Co-Opted?

Sideburn magazine's Gary Inman, a friend of mine, wrote a thought-provoking piece on Influx.co.uk (a multi-motor blogazine) called 'Custom Bikes and Trophy Wives'. I'll quote a few bits here, but if you're at all involved with the alt.custom scene, it's worth a read, and I'd love to hear your opinion. I confess to be deeply embedded in this world professionally, while never having been an owner/rider/builder of alt.customs themselves. Still, I count many of the most important players in this business as personal friends, so am well-placed to write about their world. Hence my 'Custom and Style' editorship at Cycle World...

Some thoughts from Gary: "The annexation of the most vibrant motorcycle sub-culture in decades didn’t take long...For marketing departments, desperate to find any growth in Northern hemisphere biking, it’s an easy sell. It’s all smart haircuts and expensive denim, an appreciation of art, architecture and photography, a willingness and the means to travel. The holy-bleeding-grail of target audience if you’re trying to shift ‘lifestyle’ products. And the bike manufacturers didn’t have to lift a finger for the scene to become so large they could no longer ignore its potential. What was an exciting niche is now a cliché. Inevitably. But – another question that only time has the answer to – is it a bad thing for ‘the scene’?..."

On that note, it might be worth re-reading my 'Instafamous/Instabroke' essay, or my very similar thoughts on the Industry poking fingers into the Custom scene, called 'Awake, Leviathan'.

The Sex Machine

Words: Paul d'Orléans / Photographs: Rita Minissi

She squeezed me, shouting over the freeway wind-roar, “Guess what?” ‘That’ was the latest in a long string of confessions, at which I could marvel but sadly never share: she’d had an orgasm while riding pillion on my vintage Triumph Bonneville, buzzing at a steady 65mph. It’s a heady old cocktail, sex and motorcycles, stretching back to Art Nouveau posters with bloomer’d ladies astride crude motor-trikes: hardly rousing now, but straddling and riding was understood as the playground of Victorian sex bombs. Women are the fastest-growing segment of motorcycle sales today, and despite clichés of choppers draped with bikini babes, female riders imagine new scenarios of sexuality and power with bikes.

The motorcycle is the second most intimate of machines: the first being, of course, the vibrator. An older motorcycle combines these intimacies, because they too vibrate. Within the aluminum confines of an engine, hot steel shafts push oily pistons up tightly-bored holes, with explosions every four strokes. A motor is a natural sexual metaphor, but technical progress has engineered vibration out of new machines. Lovers of old bikes embrace vibes as one note in the symphony of flaws adding up to the near-human quality of ‘character’. Before advanced engine balancing systems in the ‘80s, designers could only choose the vibratory and smooth periods for each motor. For example, I own two Velocettes: the touring Venom is dead-smooth at 65mph, while the production-racer Thruxton is glass-table dreamy at 80mph; they’re the same motor, but tuned differently, like instruments. Music works as a metaphor for riding, as we conduct a song of combustion with the wrist, shifter, brakes, and clutch, finding emotional resonance in motion and the exhaust note.

"The motorcycle is the second most intimate of machines: the first being, of course, the vibrator."

I love this music, it transports me in every sense, and while sex frequently swirls inside my helmet on a ride, its my brain, not the bike switching on the juices. Tragic, compared to the ladies, who respond quite differently to their genitals pressing atop a pleasantly buzzing, 400lb machine. Many passengers in my 37 riding years have admitted unexpected pleasures aboard my various motorbikes, and this recent event inspired an email poll: 1. ‘Have you ever?’ 2. ‘Tell me more.’ A few responses: ‘HAHAHAHA never’; ‘I’ve always wanted to share this – yes I love it’; ‘One time, on the back, holding on tight, doing the ton down a California highway on a perfect day’; ‘No - I’m too busy riding’; ‘Once as a passenger, ’96 Sportster, magic hour, he broke my heart, don’t mention my name’; ‘Last time was on Park Ave in a traffic jam smiling at the cab driver next to me.’

The general trend: passengers have more orgasms, but do they have more fun? Given motorcycling’s eternal dance with lethality, a distracting orgasm at the helm of a fast machine binds eros too tightly with thanatos. But as research fodder, the unsung pleasures of the passenger has potential; the unfathomable variety of women’s sexual response clearly extends to motorcycles, as evidenced in my brief survey. We’ve reached Terra Incognita, a great undiscussed erotic secret, hiding in plain sight. More research is needed: stay tuned - we're on the case.

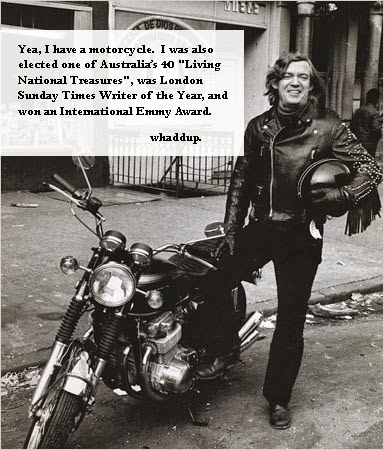

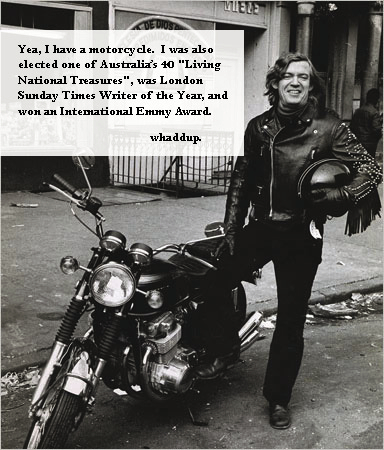

Robert Hughes: Art Critic, Motorcyclist

A champion of Motorcycling has died after a long illness; Robert Hughes, creator/host of the 'Shock of the New' television series and long-time art critic for Time magazine. While artists and public television watchers knew Hughes for his acerbic opinions on art and artists (he once described the work of Jeff Koons as "so overexposed it loses nothing in reproduction and gains nothing in the original"), he was also a motorcycle fan. More importantly, he was the most visible and well-known art critic to defend the inclusion of motorcycles in the Guggenheim Museum, at the 'Art of the Motorcycle' show.

The most famous art critic in the world 'came out' as an avid motorcyclist in his Aug 18, 1998 column in Time magazine, 'Art: Going Out on the Edge': "The fact that the great spiral of New York City's Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum is at present full of motorcycles has annoyed some critics. Not this one. If the Museum of Modern Art can hang a helicopter from its ceiling, why can't the Guggenheim show bikes? "The Art of the Motorcycle" may seem an opportunistic title until you actually see the things. Design is design, a fit subject for museum consideration, and in any case I'd rather look at a rampful of glittering dream machines than any number of tasteful Scandinavian vases or floppy fiber art."

The article laments the inclusion of only a single 'custom' motorcycle in the 'Art of the Motorcycle' show; the 'Captain America' chopper designed by Cliff Vaughs for the film 'Easy Rider': "...everything in [the show] is stock, so that it ignores the creative ingenuity that has gone into making the custom bike one of the distinctive forms of American folk art." Of course, the international explosion of Custom motorcycles since this 1998 article has merely reinforced Hughes' opinion on their importance at the 'art' end of the motorcycle spectrum.

Hughes wrote of owning two Norton Commandos before moving on to Honda CB750s in the early 1970s, and to having a bad accident on a Kawasaki, which ended his biking career. A fascinating and controversial writer, he drew from a deep reservoir of historical knowledge to support his arguments, whether or not you agreed with them. More important to The Vintagent, that seminal Time article championing Motorcycles was read by millions, far more than than were able to attend the Guggenheim show itself, and helped usher a sea change in public opinion about bikes, as worthy subjects of study and exhibition.

For Hughes' obituary in the New York Times, click here.

For a selection of his scathing art criticism, click here.

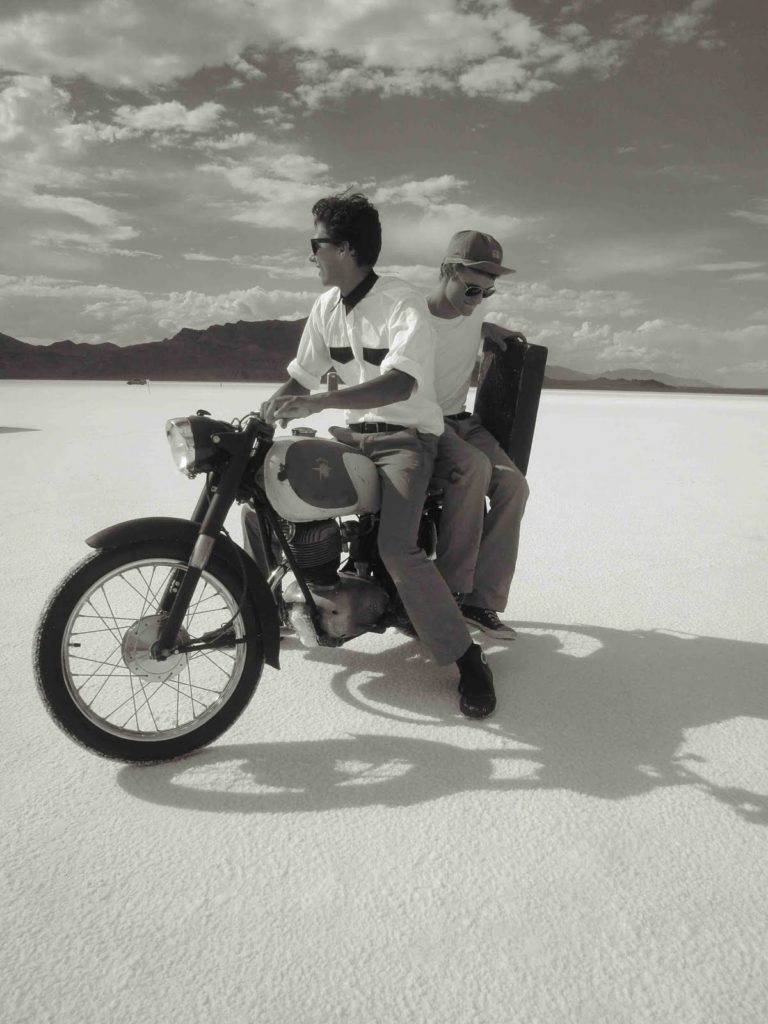

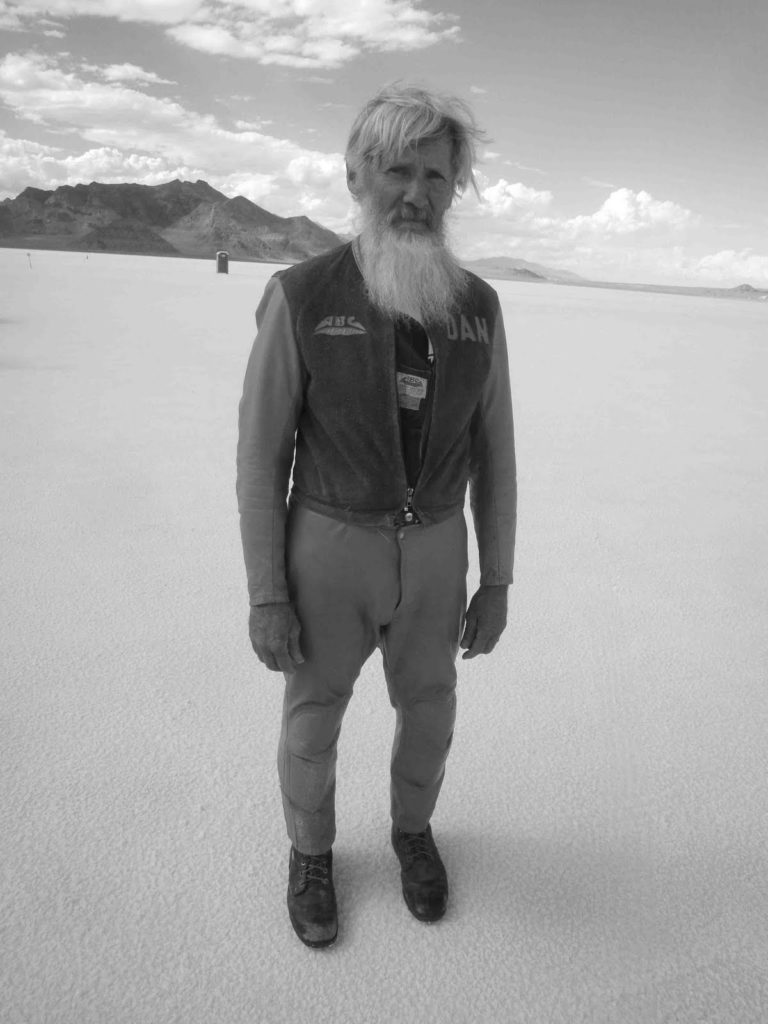

Song of the Salt

In the last Ice Age, Lake Bonneville was a 20,000 square miles large and a thousand feet deep; abused by climate changes and the bursting of natural dams over the past 30,000 years, only a few actual lakes remain, remnants of this once-mighty inland sea. Ringed by high mountains and fished by locals ten thousand years ago, caves a hundred feet up the mountainsides, the former shoreline, are still being discovered with old fishhooks, woven sandals, and bones. Distill a lake that large into the atmosphere, and liquid memory becomes a thin, hard layer of salt, dead flat, but not smooth. Bonneville State Park is enormous, and entered from a 10-mile strip of asphalt called the ‘boat ramp’ - the lake’s memory hovering above.

Bonneville is still a lake at times, as every winter the 4000’ altitude brings rain enough to fill the shallow basin with a few inches, refreshing the surface as a season-long tide smoothing the surface. The alluvial deposits ringing the lake grow a salt-resistant scrub as they descend to the flat, dotting the now-dry waterline with tufts of soft green for a mile as packed silt gives way to a dusting of white, then a thin and soft crust, and finally, a mile and a half from the edge, an inch-thick, hard layer of million-year old salt.

The salt is a terrible place to go fast, and the worst possible place for machinery.

But the salt is disappearing, the hard center pan shrinking every year, as the winter lake is pumped away to extract valuable minerals. The mining companies are obligated to return the salty water and refill the basin, but this costs money, and their years of skimping leave less and less salt, and a grassroots movement to ‘save Bonneville’

The center of the salt flats is no place for a human, utterly forbidding, with no water, no plants, no bugs, visually disorienting, and plenty hot. The nearby mountains are no guide to scale or distance, their bases floating on mirages, the dry clarity of the air bringing them close, but an exploratory hike in any direction will see you plodding for hours, overheated and dehydrated. For all its inhospitality, the salt remains a place of extreme beauty, a photographer’s paradise, a massive white canvas stretched horizon to horizon, making art of anything placed upon it. Every hour of the day, every mood of cloud, sun, or evaporating rain is simply stunning, the most so with a bright blue sky touching the white under your feet in every direction.

Bonneville is also the worst possible place for machinery. Corrosive salt cakes every crevice and cranny, refusing to leave, eating away at anything metal. Washing your machine, your car or motorcycle, is a good idea, and a joke. If you don’t strip your motorcycle down to the nuts, crankshaft, and spokes, you won’t have a motorcycle in a few months; certainly not a safe or rideable one. The salt will eat your chain first, then your steering head bearings and spoke nipples, and eventually start on your frame, because when you washed your machine, liquid salt went inside too. Rental car companies will charge $1000 if they find salt caked under your car, as you’ve effectively destroyed it (although they’ll just sell it to someone else).

The salt is also terrible place to go fast. Yes it is generally packed firm, on a good year, although on a bad year even the scraped-smooth racing lines will have soft spots hungry for your speed. Packed salt gives poor traction, being greasy and slick, with loose bits scattered over the top, and applying power is a delicate business. Plenty of powerful machines simply cannot put all their horsepower through the wheels, and calculating wheelspin into rpm/speed readings is a fine art. Typically estimated at 10% of your wheel rotation, what this means is you’re doing a white burnout all the way down the line. A too-rapid course correction, say after a gust of wind, could well have you spinning off course, or far worse. Braking is a bad idea too, for the same reason; what you are riding on is best thought of as salted ice. Flat yes, fairly smooth (but pretty bumpy in the pilot’s seat), slippery and treacherous for the very people who cannot keep away; acolytes of the cult of Speed.

They come from all over the world. Denmark, Australia, Germany, England, Japan, Canada. It is the most truly international of all race meetings, all comers in a salty embrace. The racers are sometimes rivals, but to a man (and woman), their only true foe is Time, and against clocks they battle, any hundredth of a second shaved from a measured mile a victory. Time is not the enemy though - the salt is. Time will kill us all in the end, but the salt might get there first, or simply bedevil your years-long preparations with niggling little problems, or catastrophic ones. The beginning of a Speed Week at Bonneville creates a mechanical village in the center of nowhere, a 6 mile drive into white blankness, a huddle of trailers, canopies, big rigs and motorhomes huddled close in the vastness. By the third day, holes in the gypsy camp appear as dejected racers and destroyed machines skulk home, to try again next year, or not.

Every vehicle has a crew attached, sometimes just a patient wife providing water and company to a sweaty middle-aged man out for a little low-cost fun on a vintage Suzuki two-stroke. Sometimes the sheltering canopies host spreading mobs of interested semi-participants and hangers on, out to see what their favorite will do, eager to lend support and good cheer, even when magnetos go south or mysterious misfires have riders cursing the gremlins tormenting their labor, and their patience.

Some crews seem to hoard luck, making easy runs at eyebrow-arching speeds, with ratty looking contraptions or immaculate objects of beauty; there is no predicting who will do well by appearance, neither of machine, man, or crew. Every camp has a ‘vibe’ and a look about it; some clean and simple and Scandinavian, some scruffy and full of apparently unrelated metal objects in a good-humored jumble, some professional and cold. Again, no predictor. Some of the most impressive machinery, mighty and awesome in its supercharged, nitro-injected, double-engine streamlinitude, are utterly impotent, posting times bested by 40 year old mid-capacity road bikes. Gremlins; sometimes permanent ones. These sites you avoid, knowing the money and time invested, thinking ‘but for grace, there go I…”

For all its difficulty, for all its harshness, Bonneville remains as romantic as a doe-eyed candlelit dinner with your true love, it is the ultimate temple of going fast for its own sake. There is no reward but a cheap slip of paper with numbers, but something about the history and energy of the place makes you want to Go, man, Go; get on your machine, and nail it. Even in the rental car you’ll have to spend two hours cleaning afterwards…