'The Chopper: the Real Story' Reviewed

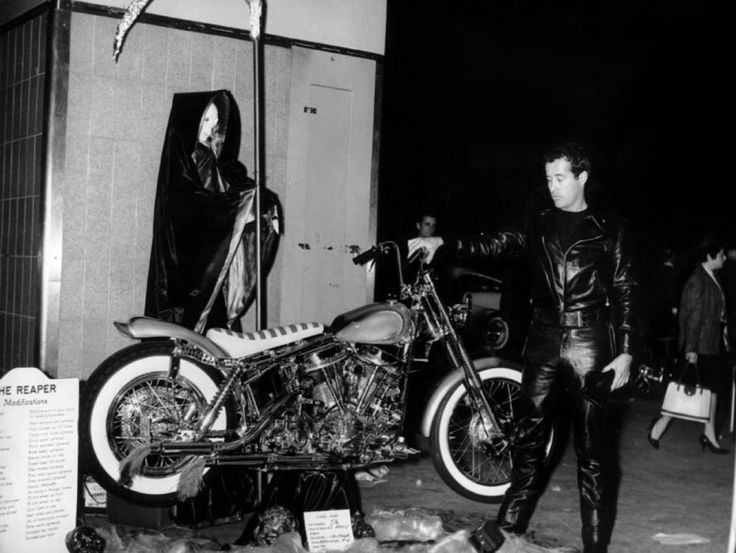

Speedreaders.info, which features 'authoritative reviews of transport books and media', has seen fit to review my most recent book 'The Chopper: The Real Story', and to their great credit they've clearly read it cover to cover (and noted its 60,000 word content). They also grasped my intention for the book; to provide a new context for understanding the chopper thing, as a uniquely American phenomenon akin to Jazz, Rock n' Roll, the Beat scene, and Abstract Expressionism. The chopper can be understood as a Folk Art movement with deep roots in a multi-racial American counterculture, as my research demonstrates in the book. I'd be honored if you'd give it a read; you can purchase The Chopper: The Real Story

here!

Read the review on Speedreaders.info here!

Vintage Revival Montlhéry 2015 (Pt 2)

George Orwell's Motorcycles

Vintage Revival Monthléry 2015 (Pt 1)

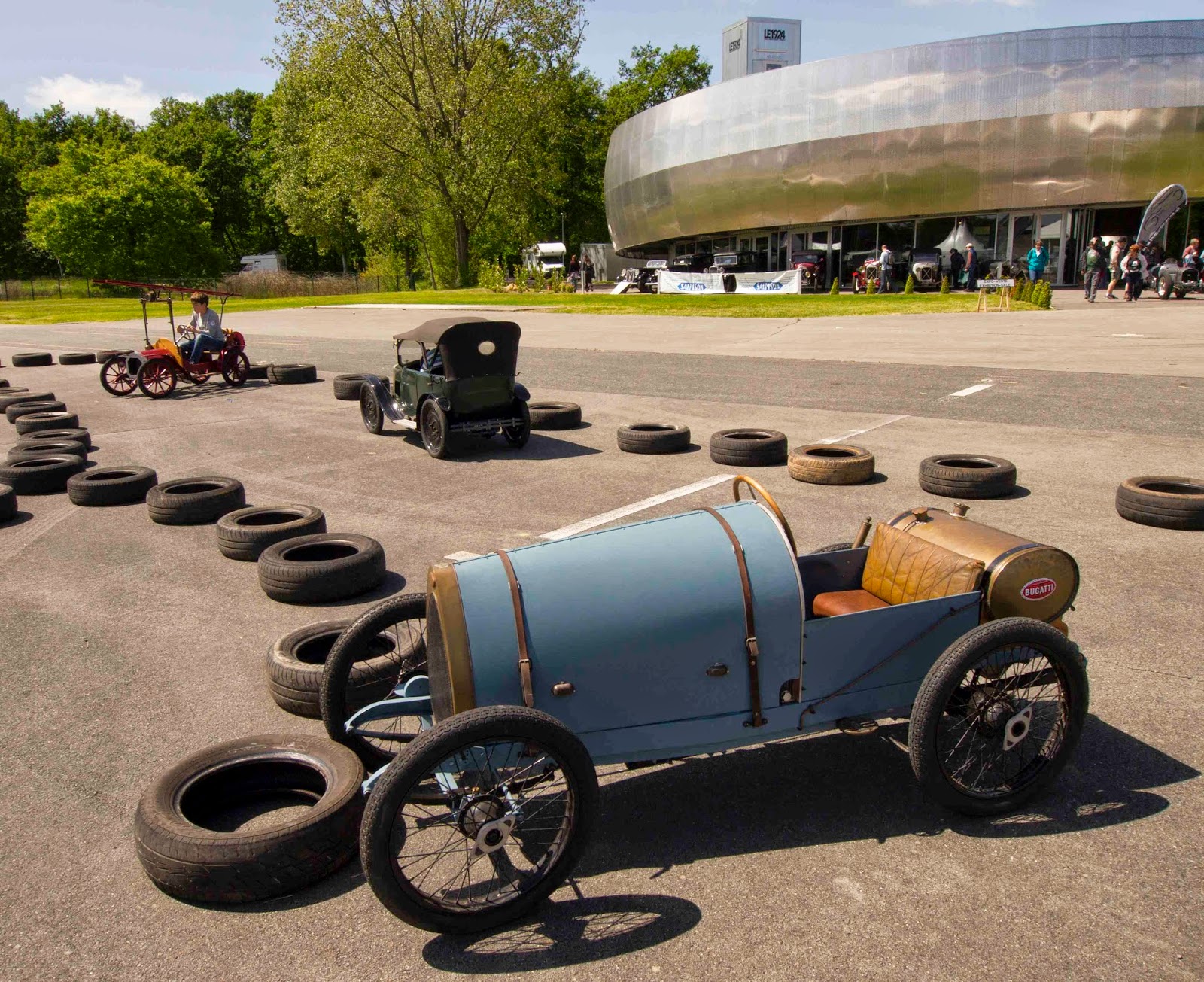

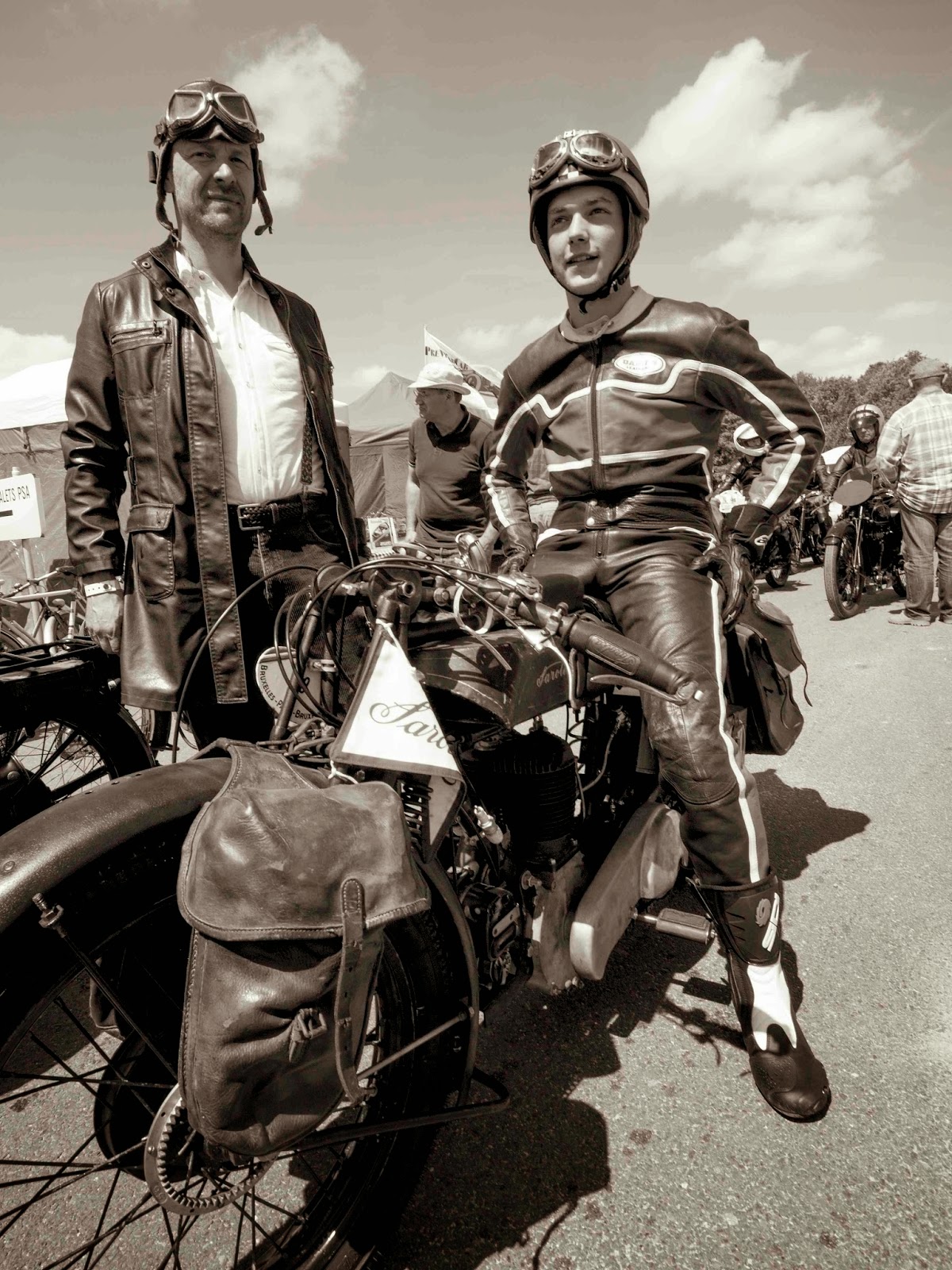

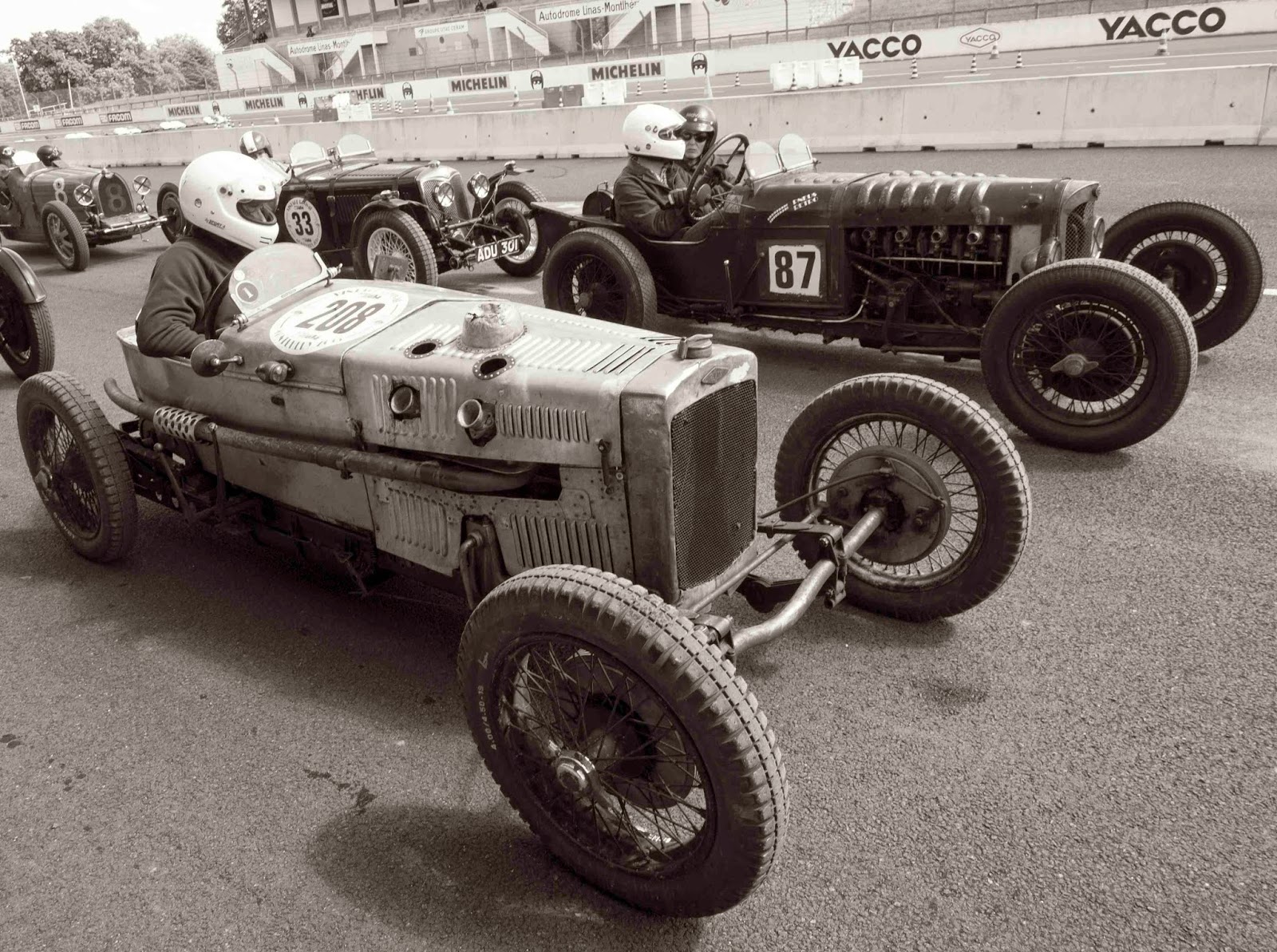

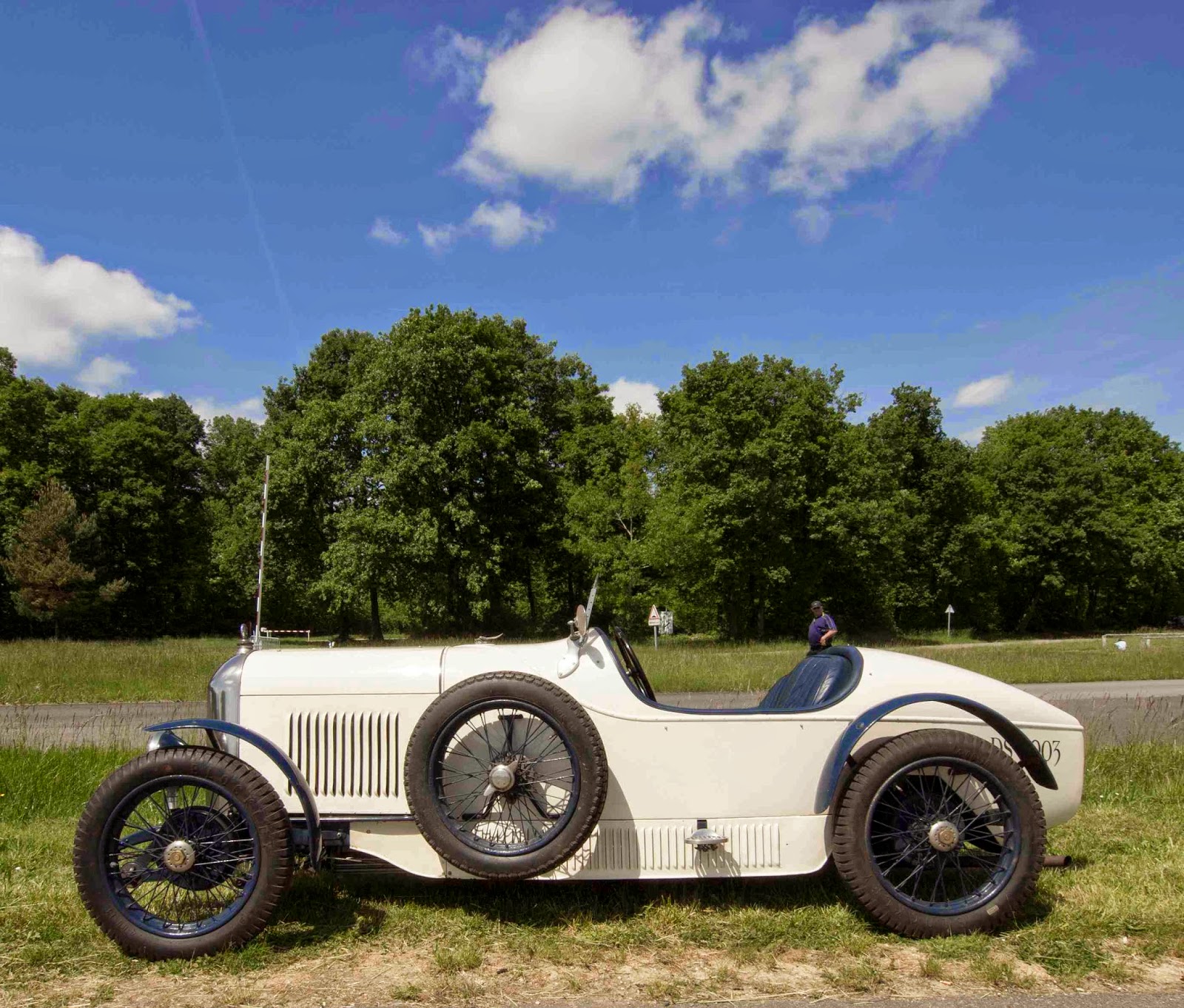

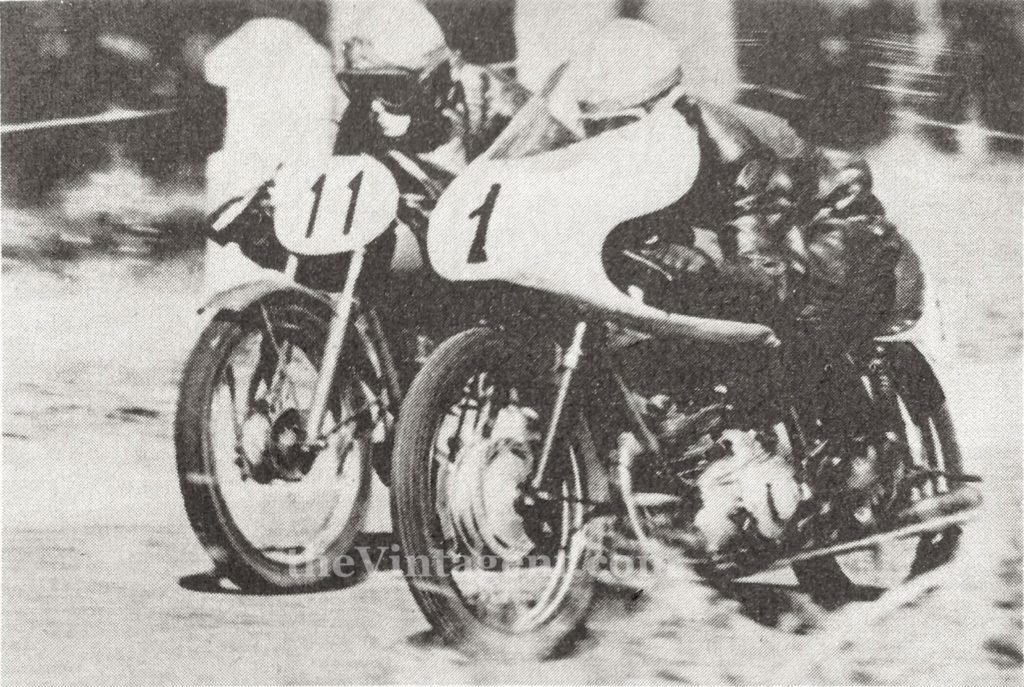

Why on earth, my friends ask, would I travel 20 hours on a round-trip plane to Paris, and spend a couple of grand of my own money to attend a weekend event at a suburban Parisian racetrack in lousy condition, with shabby amenities, mediocre food, which is a pain to reach unless you have a car? The reason is simple; it’s worth it. If you’re a fan of pre-1940 racing cars and motorcycles, there really isn’t a comparable event, anywhere. Vintage RevivalMontlhéry has become to my eyes the most authentic vintage motorsports event in the world. Not as in ‘period correct’ as per the Goodwood Revival, that glorious costume party of 50,000 people, who are not allowed access to the truly interesting stuff, like the pits. It may be the right crowd, but it’s Disneyland crowded, and shares a bit too much of that park’s gloss for my taste. I prefer a little grit, because pre-war racing wasn’t a theme park, it was dangerous and poorly-paid stuff, and the participants did it for the love of the sport.

I suppose if that tens of thousands turned up at Montlhéry there would be tiered access as well, but as the crowd is still 4-figures small, with a very large playground, it feels very much in tune with the old Brooklands ad – the right crowd, and no crowding. VRM is the work of Vincent Chamon, who took on the mantle of the late lamented Jacques Potherat, the grandfather of vintage racing in France, who organized a ‘Vintage Montlhéry’ gathering for decades, before his untimely death 15 years ago. The track was without such a mixed-vehicle event for ten years, until Chamon decided to do something about it. This is the third of these bi-annual events, and it just seems to get better.

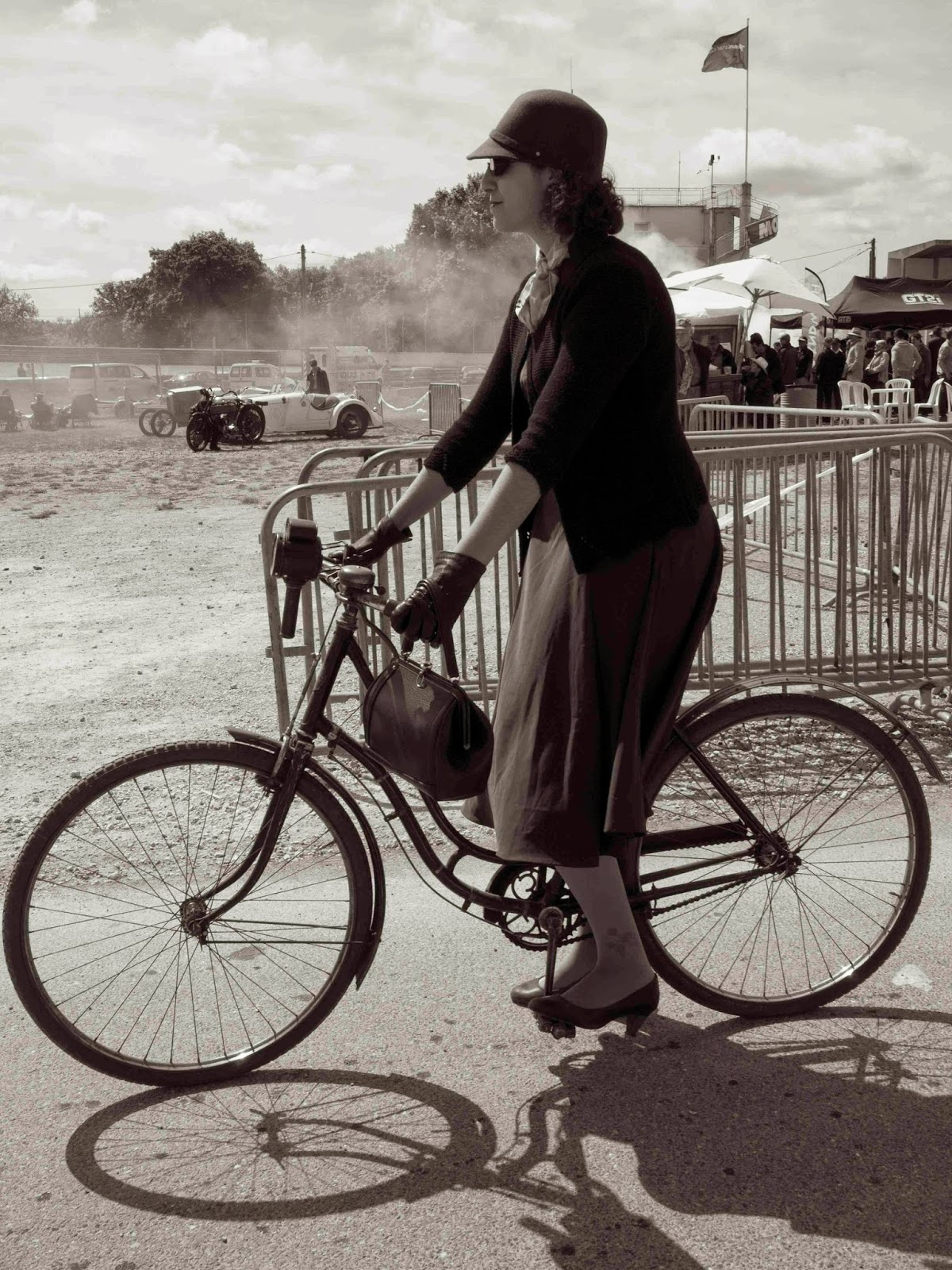

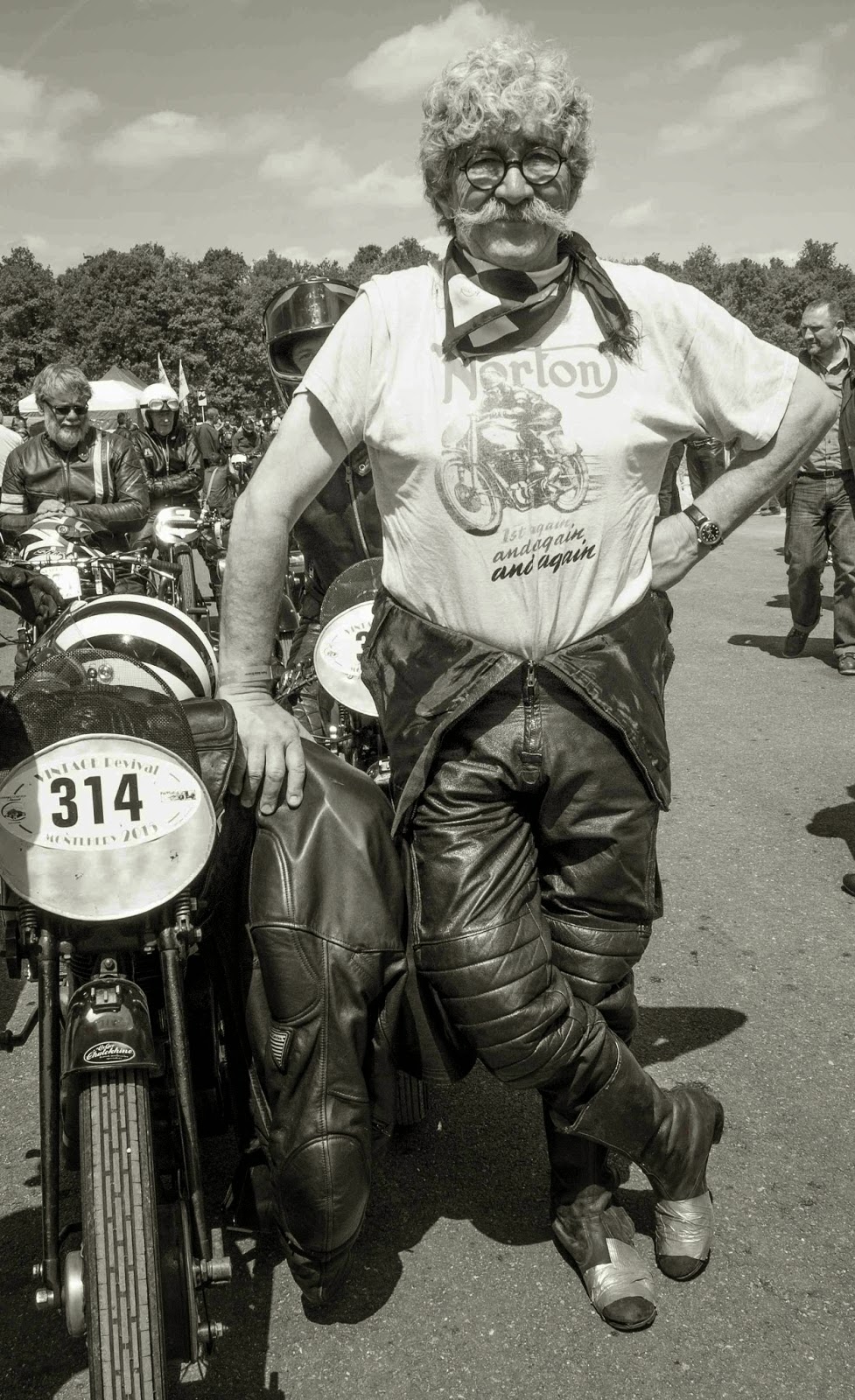

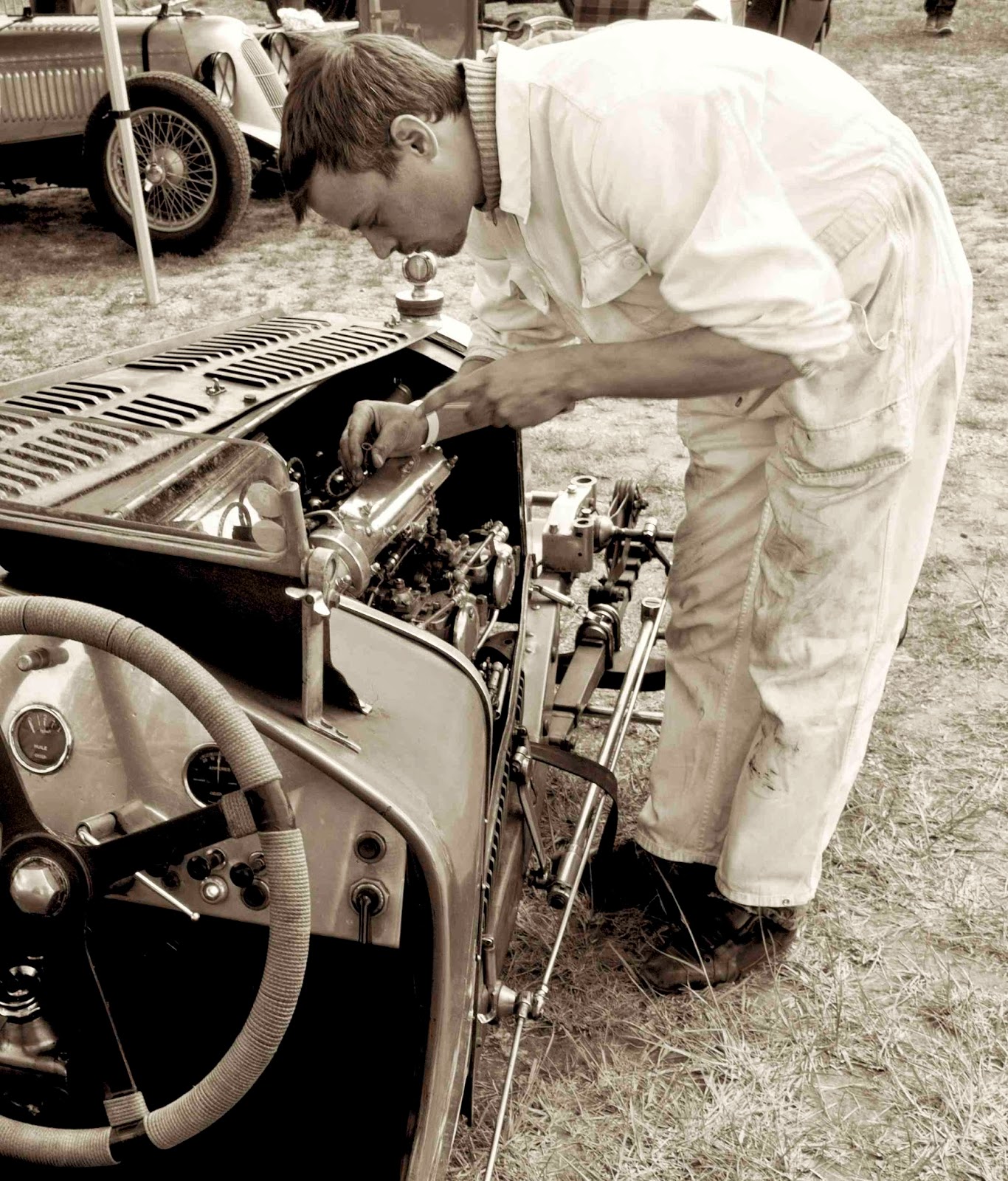

Unlike most motorsports events, the organization is almost invisible, with a very light touch. Gents and ladies in white boiler suits direct the action, and their attention is generally focused on getting vehicles onto the track in an orderly fashion. The glorious chaos of the scene, which actually has a fluid and orderly movement, includes a mix of pedestrians, bicyclists, children, and racing vehicles using the main throughfare/track access, which means there’s a constant mix of revving racers and ordinary folks milling along, with a kind of friendly acceptance of of each group’s needs. The frustration level looked very low, and I didn’t hear a voiced raised in anger amongst the scrum between pits and track, which considering the high temper of a rider or driver about to do hot laps, is really something.

Perhaps it’s because there’s nothing to win; the track time is a ‘parade’, which means a few take full advantage of the fantastically historic track’s banking and chicanes, while most are content with a fast but not furious pace. Some even potter, and know well enough to stay out of the way, clinging to the very bottom of the banking, while the really fast ones sail up the top line, which feels awfully near vertical when you’re on it. It’s an eerie sensation to gaze at the top of another rider’s helmet as you pass by/over and they’re perpendicular to you. But it is bumpy on the crumbly old concrete. Riding the track is truly living the history of the place, as an awful lot of world speed/distance records were set there from its inception in 1924 through the 1960s. Unlike Brooklands, competing interests (like tanks) never sullied the architectural concrete track banking, and we can still enjoy the magnificence of the place today. I found it especially poignant to be back at Montlhery after visiting Daytona for the first time last September, during the Cannonball, and being sorely disappointed at the lack of romance about the place. The center of the Montlhéry track is a forest, with big swaths of green grass, flowers, and shade if you need it. The grandstands will hold a thousand people at most, all else is trees and sky in the environs; it’s simply gorgeous. Visit the place before something stupid happens.

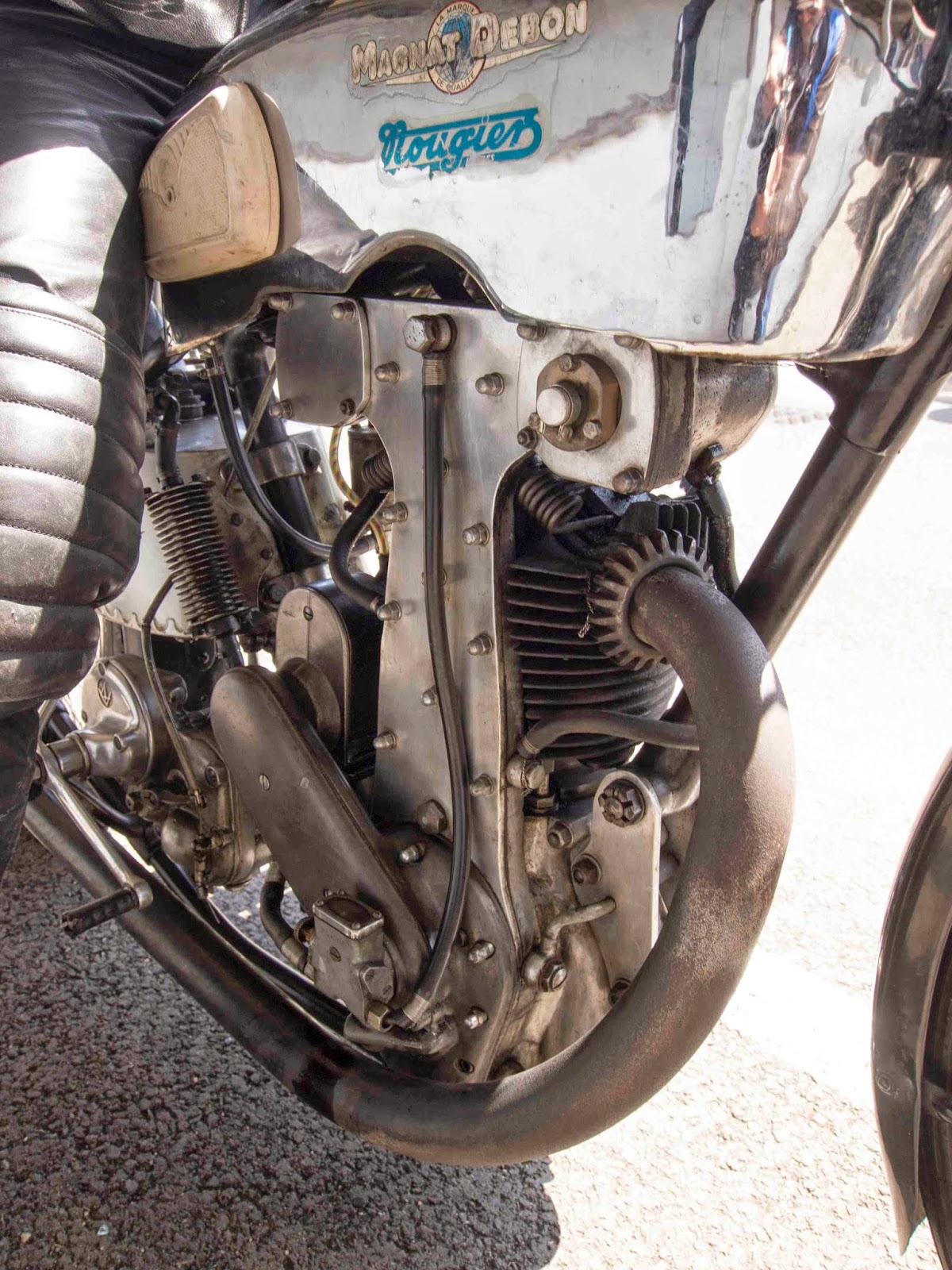

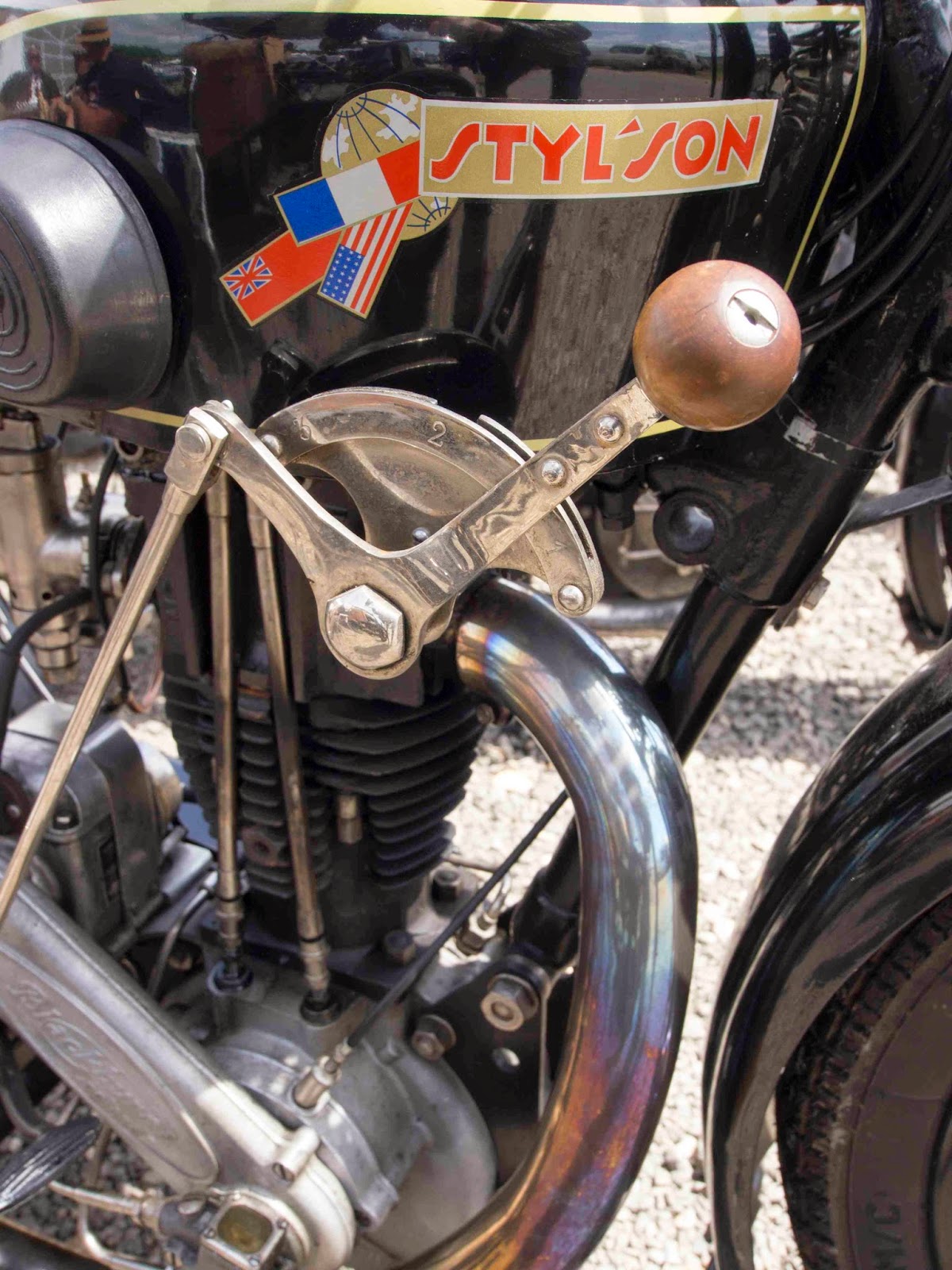

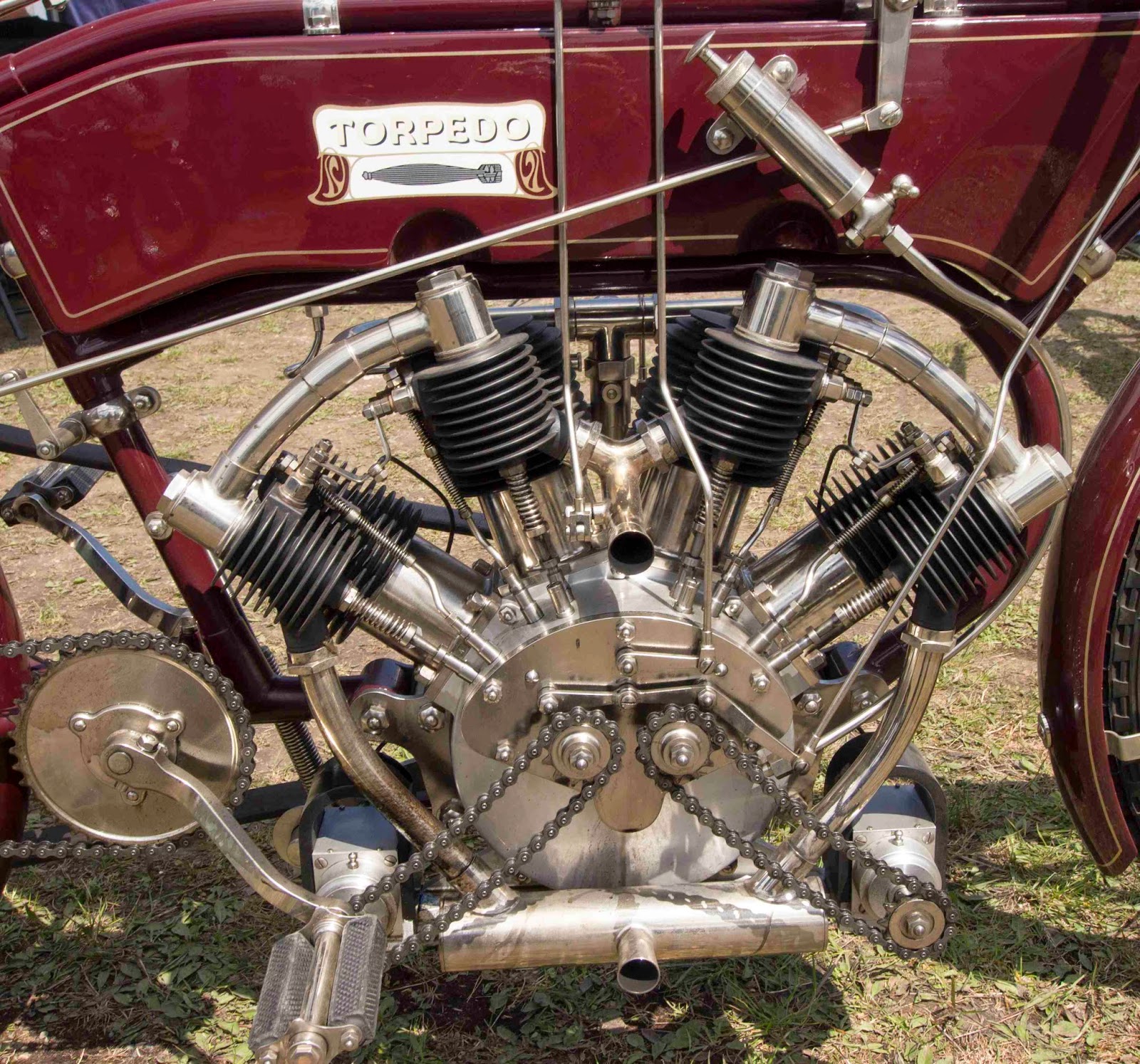

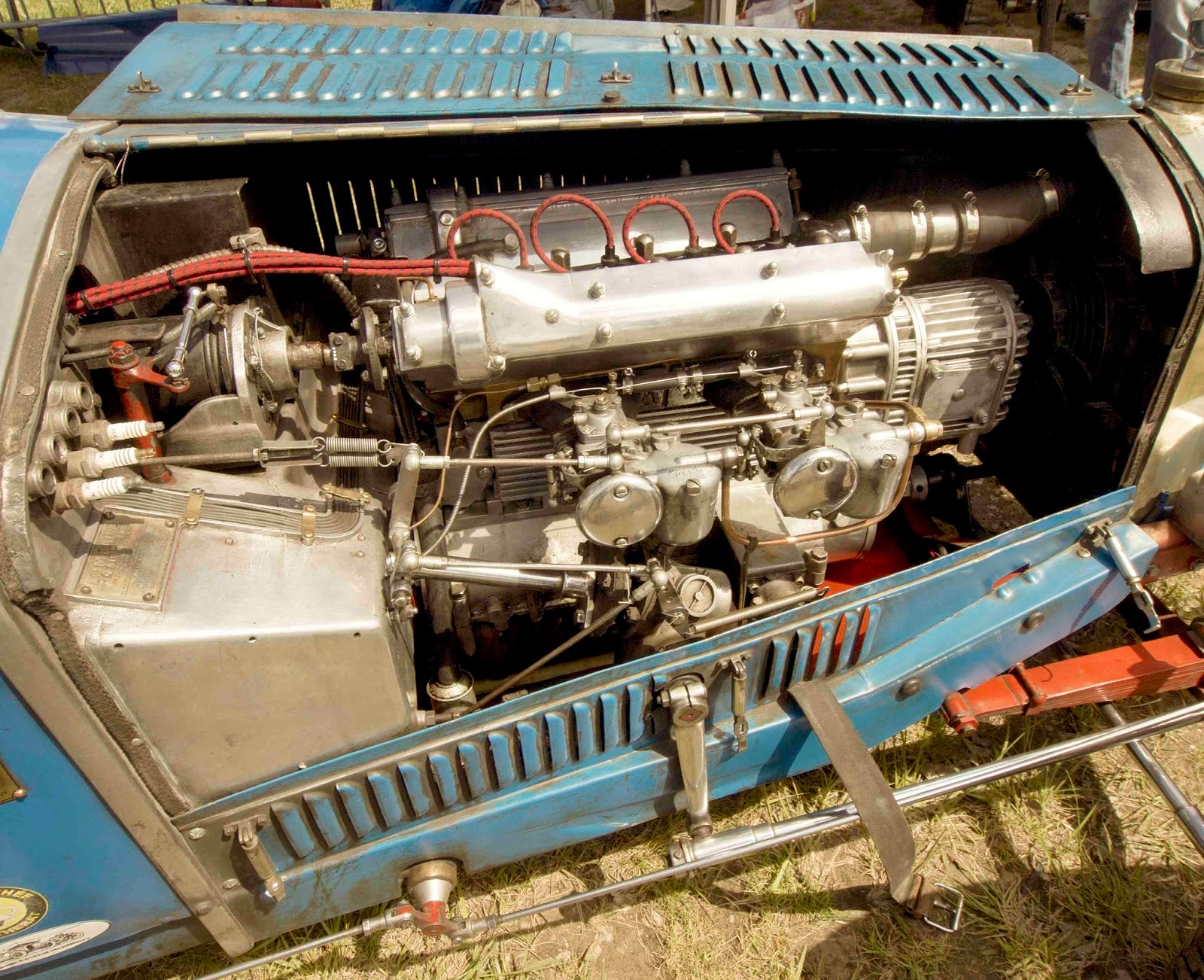

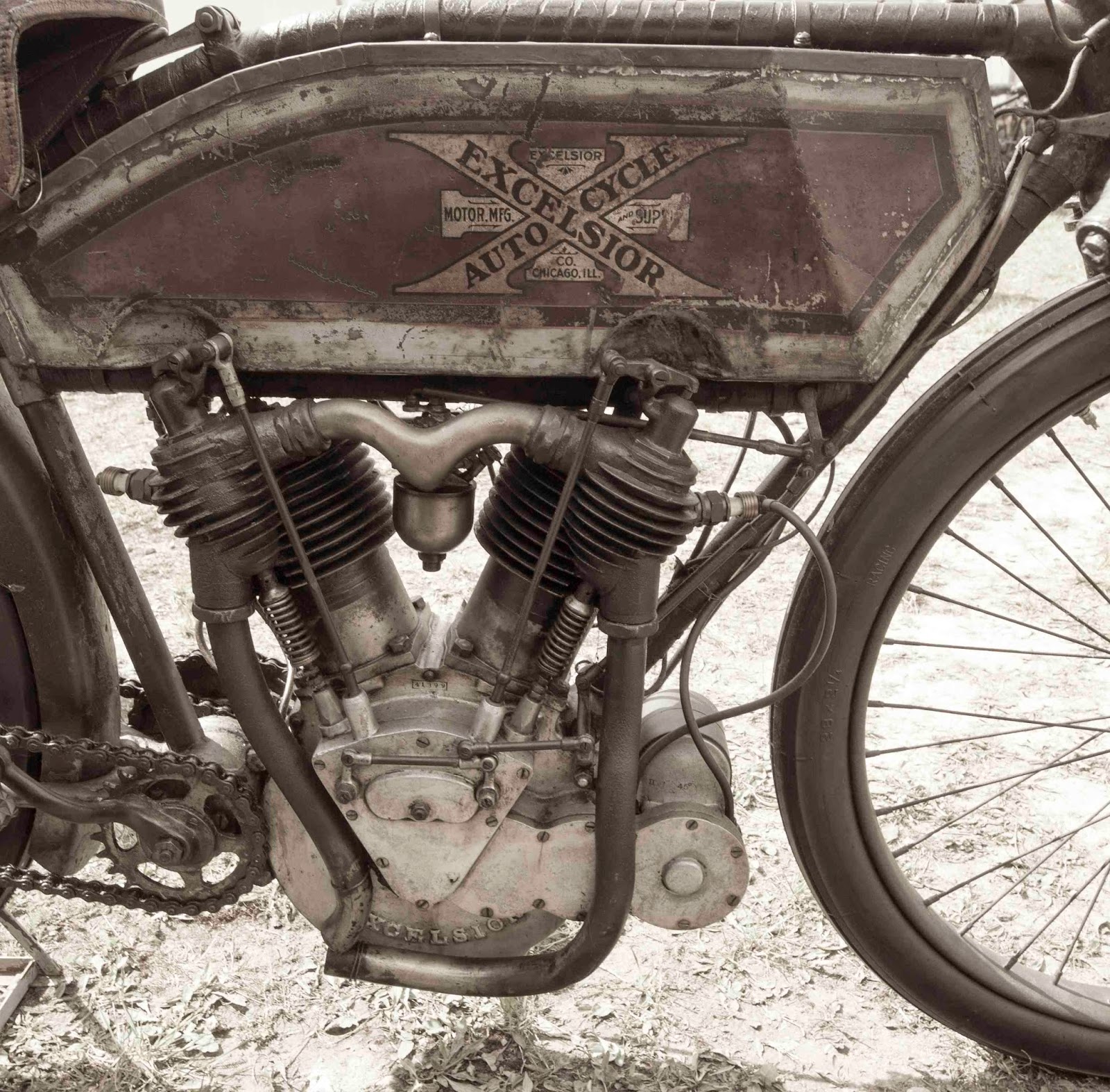

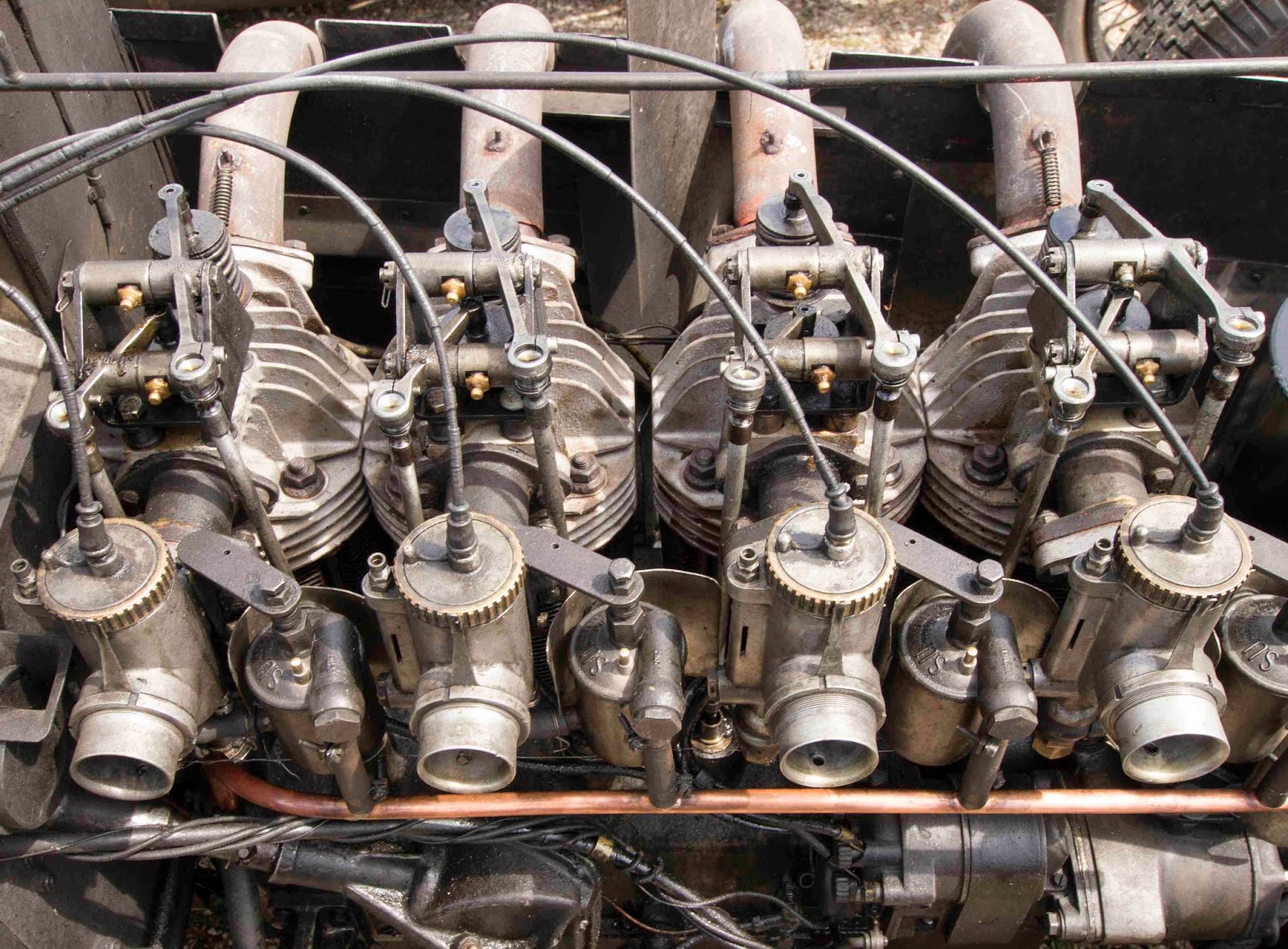

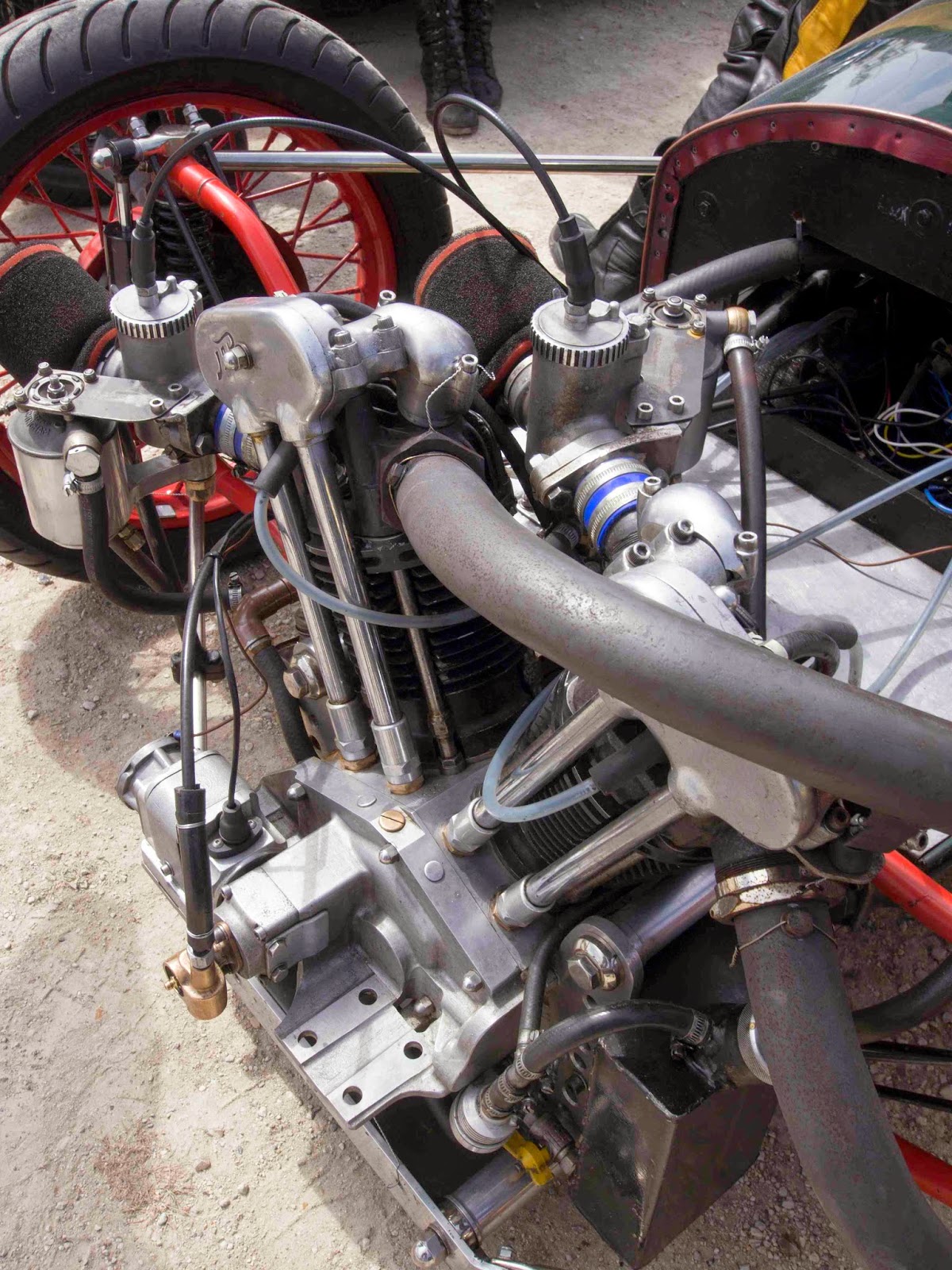

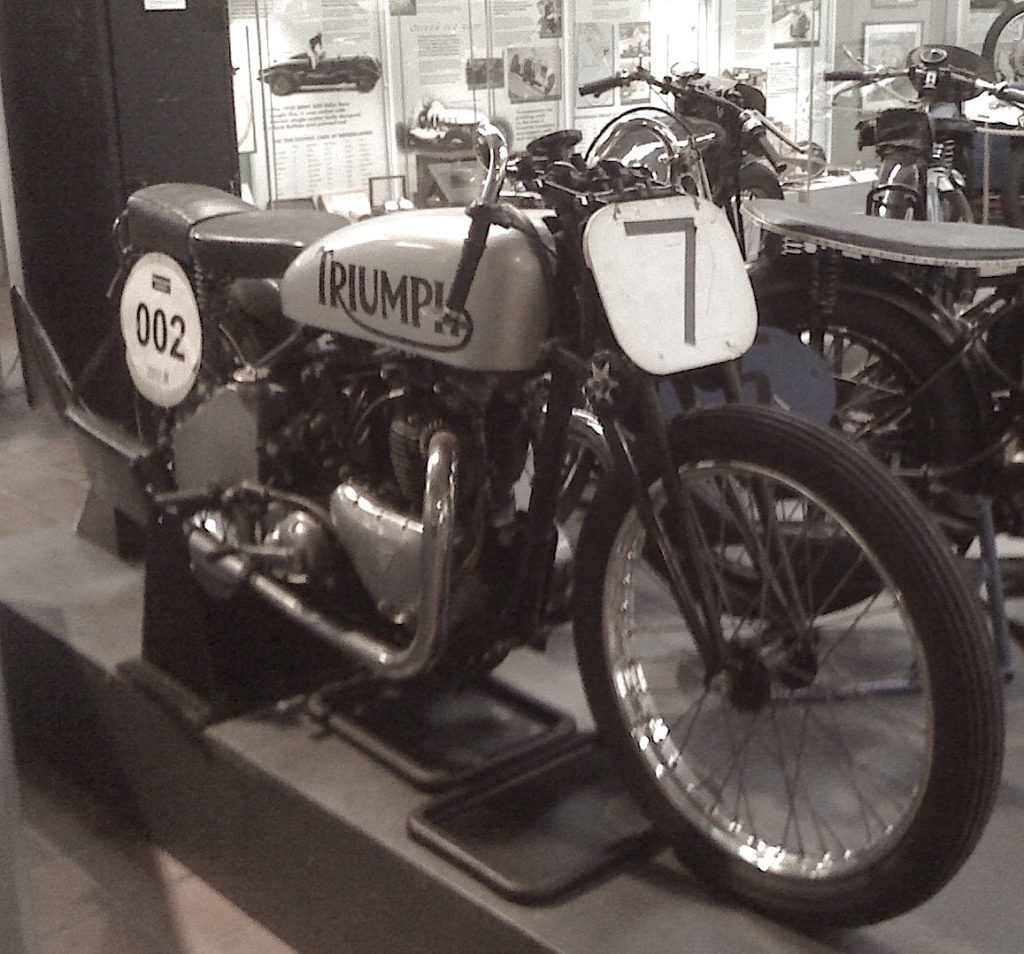

What appeared in 2015? Racers from collections all across Europe, from as far as the Czech Republic, with plenty from Germany, Holland, Italy, and England. To date, no motorcycles from US stables have appeared, a situation I’d love to rectify in 2017. There were American bikes certainly, Indian and Harley and Excelsior board trackers which seemed right at home on the banking – just about the only venue suitable for them actually. Mostly it’s what you would have seen on European Grand Prix circuits from the early 1900s through 1940, with plenty of ultra-rare machines you’ll see nowhere else, dragged from the depths of family collections far from the public (and the tax man’s) eye. The photographs here are a reasonable selection, but don’t encompass nearly everything – just the ones I managed in an attractive shot.

Here’s huge thanks to Vincent Chamon and his team for putting on an exceptional and beautifully run weekend event, and for arranging perfect weather too!

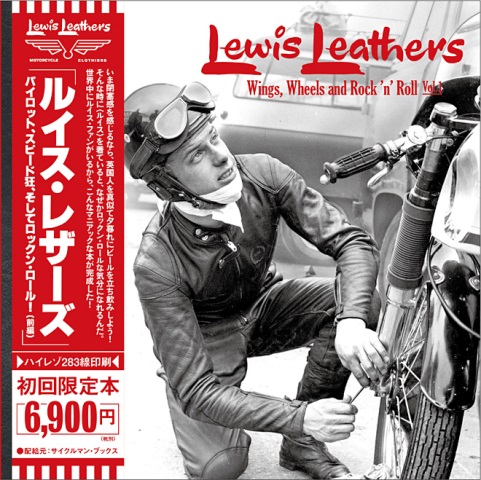

Book Review: 'Lewis Leathers'

If your library isn’t half full of Rin Tanaka’s books, it’s time to upgrade your bookshelves. He’s produced the My Freedamn! series since 2003, exploring the history of motorcycle, surf, and skate culture, mostly through the lens of clothing. His books are self-published, but you’d be very wrong thinking they’re anything but first rate, even when documenting the seemingly prosaic history of SoCal surf tee-shirts from the 1960s!

He’s also produced books in collaboration with Harley-Davidson (The Harley-Davidson Book of Fashions), Steve Mcqueen’s 1963 ISDT ride - Steve McQueen 40 Summers Ago....Hollywood Behind the Iron Curtain (Cycleman Books), a general history of leather jackets (Motorcycle Jackets: A Century of Leather Design), and even helmets (The Motorcycle Helmet: The 1930s-1990s

)!

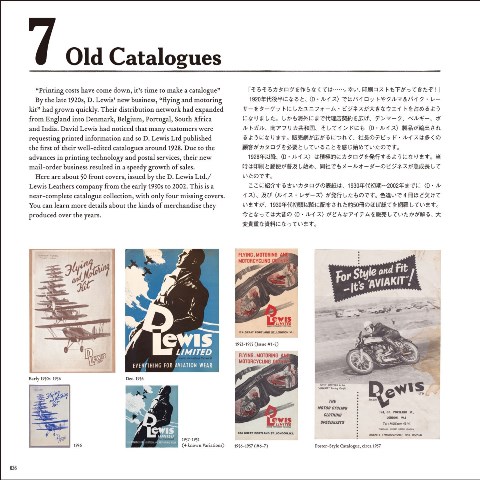

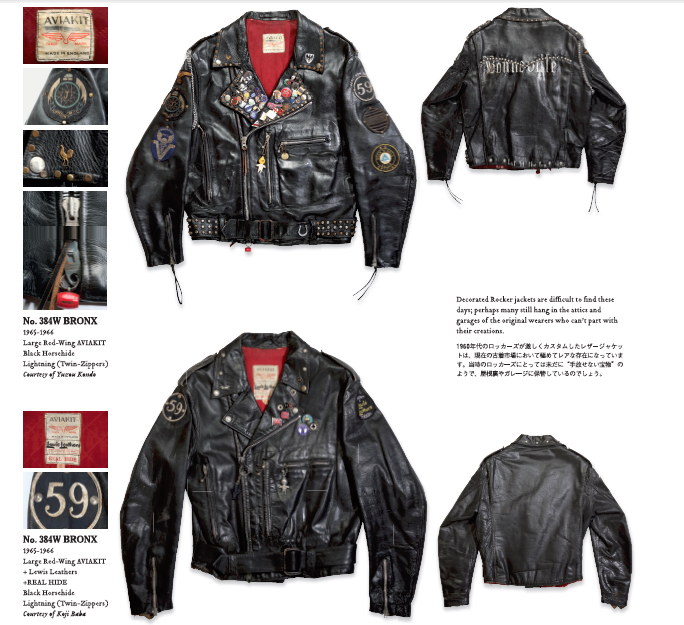

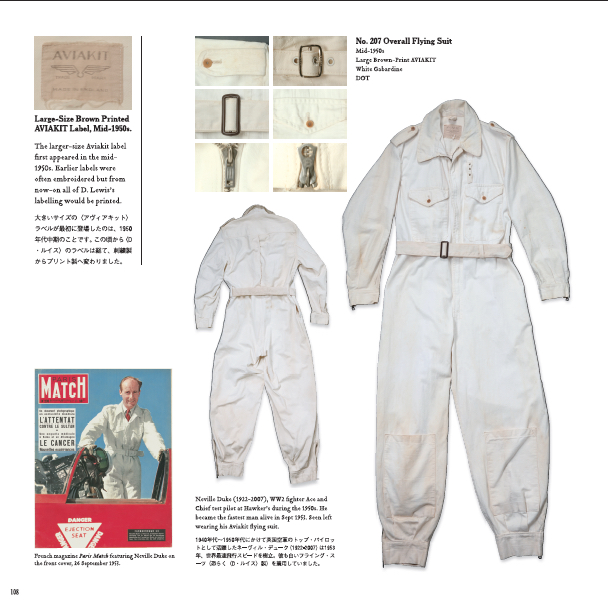

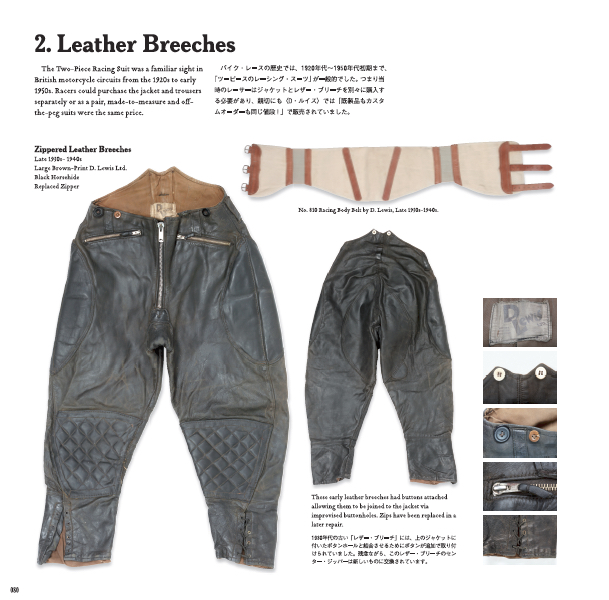

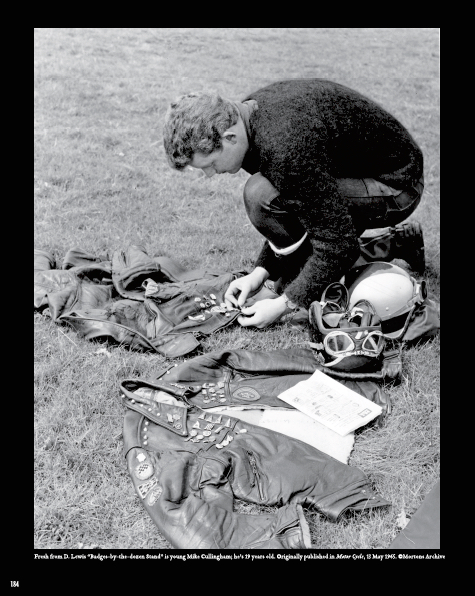

Tanaka’s latest history is Lewis Leathers Vol.1: Wings, Wheels and Rock 'n' Roll (English and Japanese Edition), a fine-grained exploration of the esteemed Lewis Leathers, the oldest motorcycle clothing company in Britain, ‘since 1892’. His book benefits directly from decades of research by Derek Harris, the current owner of Lewis Leathers, who has obsessively archived the designs and advertising materials of the company he purchased in 2003. Since 1991, Harris had been sourcing vintage Lewis Leathers jackets to satisfy demand for the Japanese market; at the time, the company had none of its vintage patterns to hand, and Japan wanted the company’s designs from the 1950s and ‘60s. Harris would purchase and disassemble old LL jackets to make patterns, and have the old designs replicated, down to the correct labels and zippers used in the originals. Harris is an archivist extraordinaire for this single subject, having spent 25 years pulling together the intellectual property of this 125-year old company.

Lewis Leathers and its various side brands – D. Lewis, Aviakit, etc – have gone through countless cycles of popularity with different groups, from aviators, motorcycle racers, and in latter days to punks and fashionistas. Rin Tanaka’s new book, ‘Lewis Leathers: Wings, Wheels, and Rock&Roll! Vol. 1’ is an extraordinary compendium of the clothing, advertising materials, and period photographs documenting the early history of the company. With 1600 photographs, the book shows how Lewis Leathers became an absolute icon of racer/rocker/punk/fashion history.

This book is a must-have! You’ll spend hours poring over the photos, which are really terrific. You can order Lewis Leathers Vol.1: Wings, Wheels and Rock 'n' Roll (English and Japanese Edition) here!

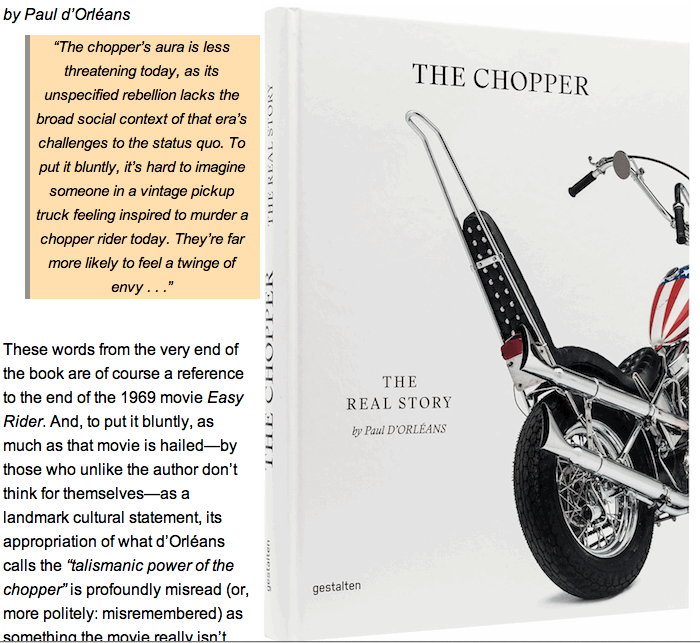

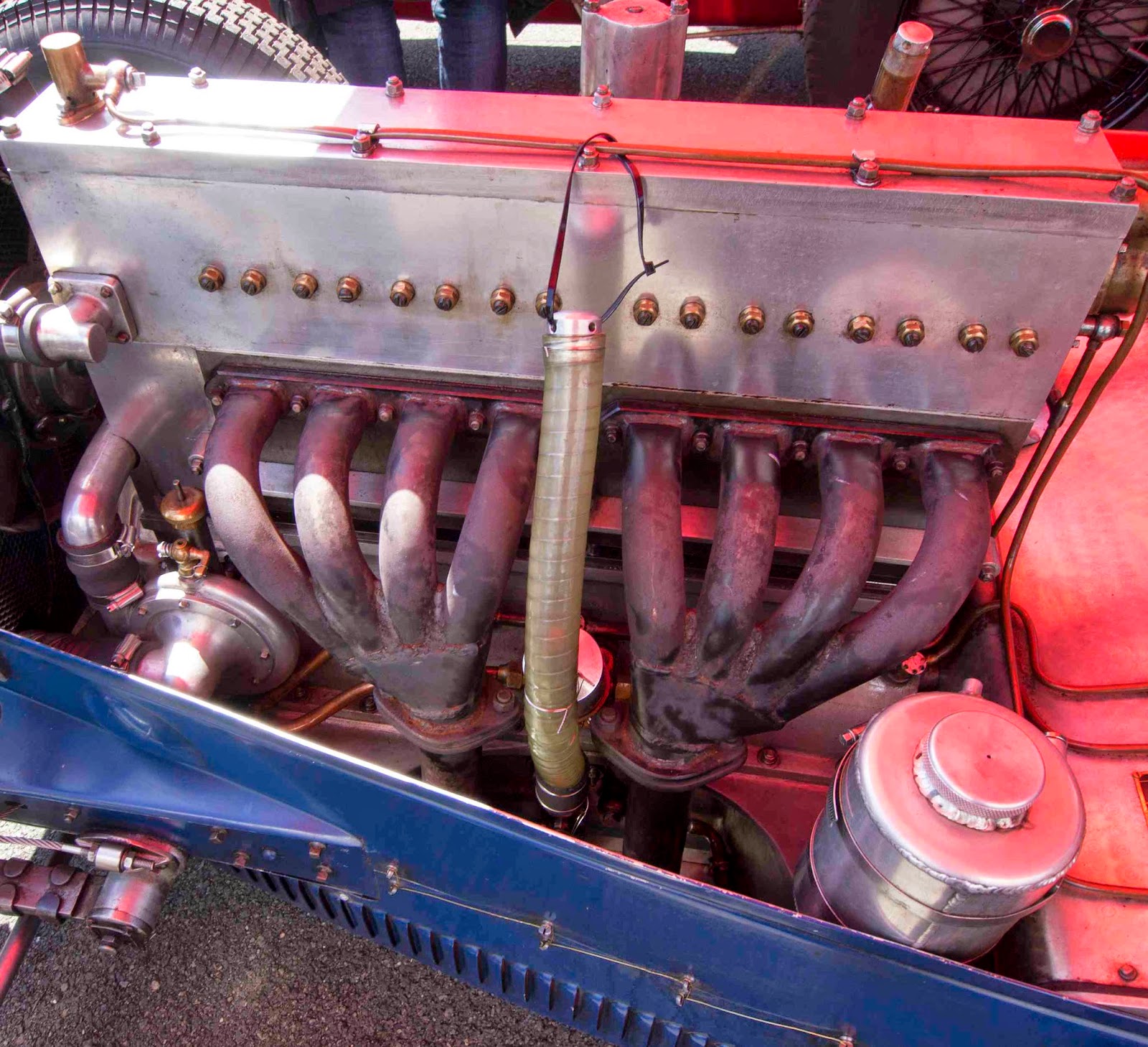

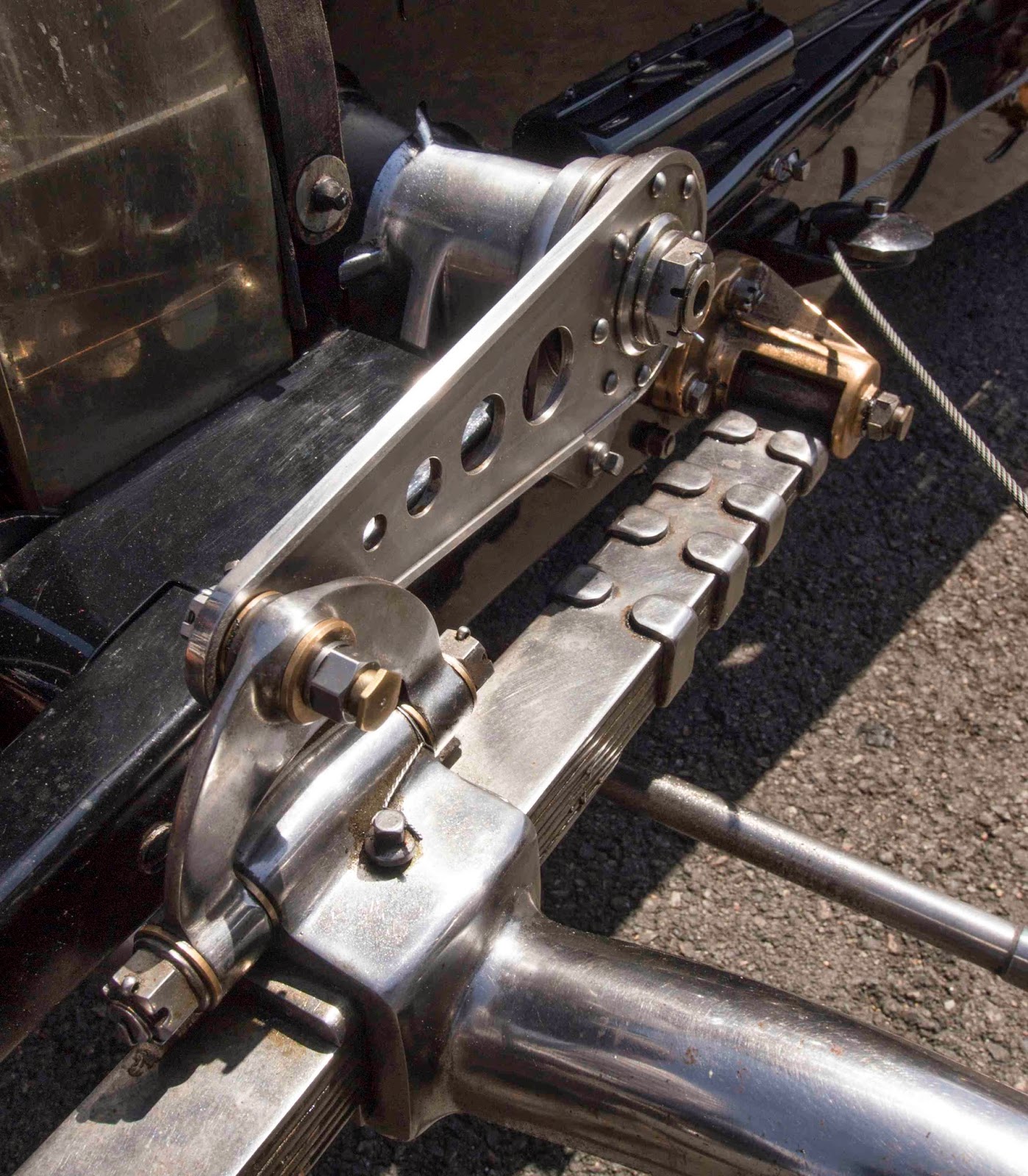

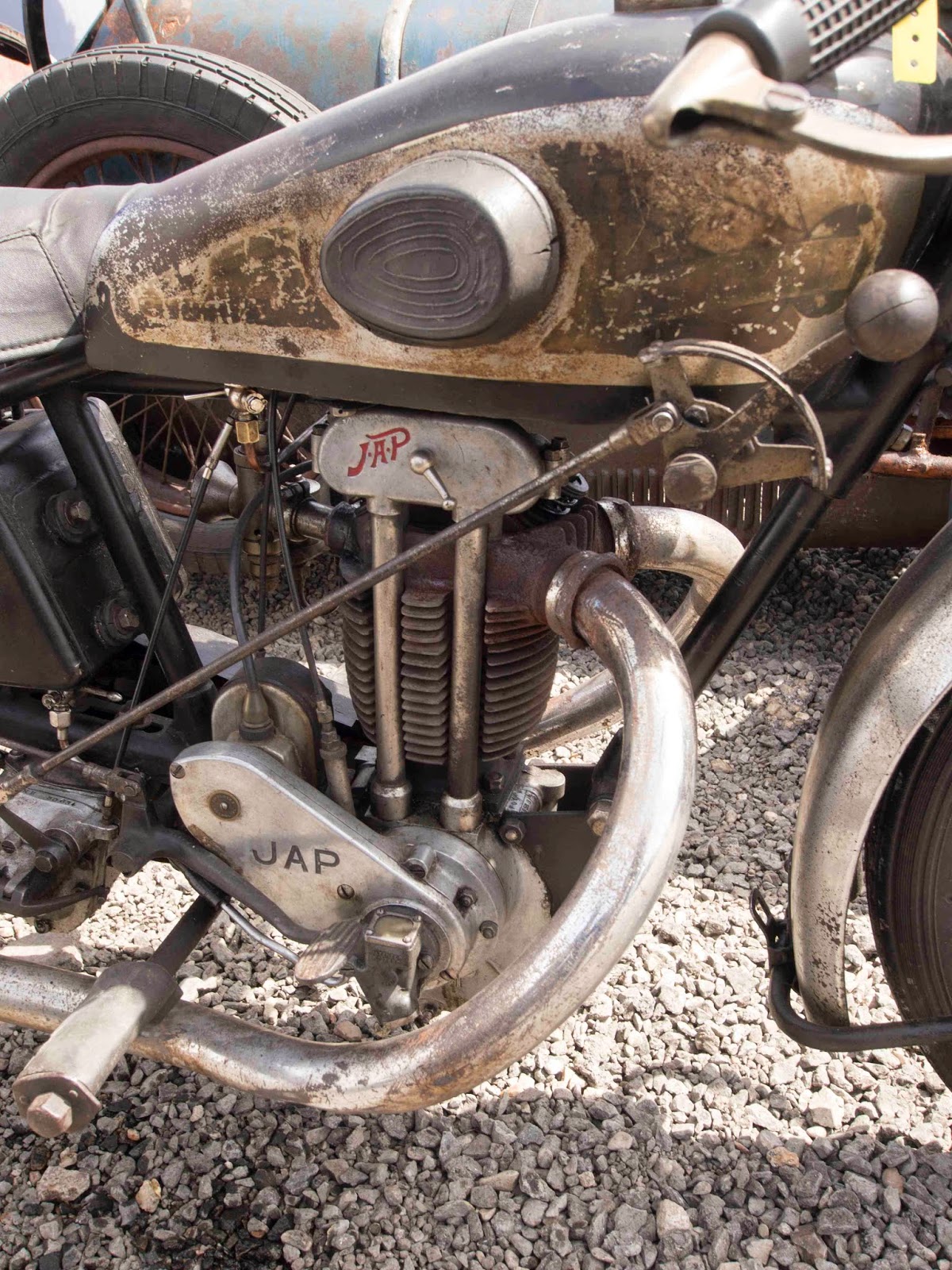

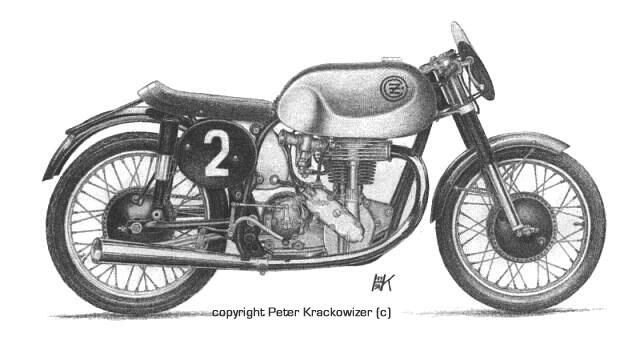

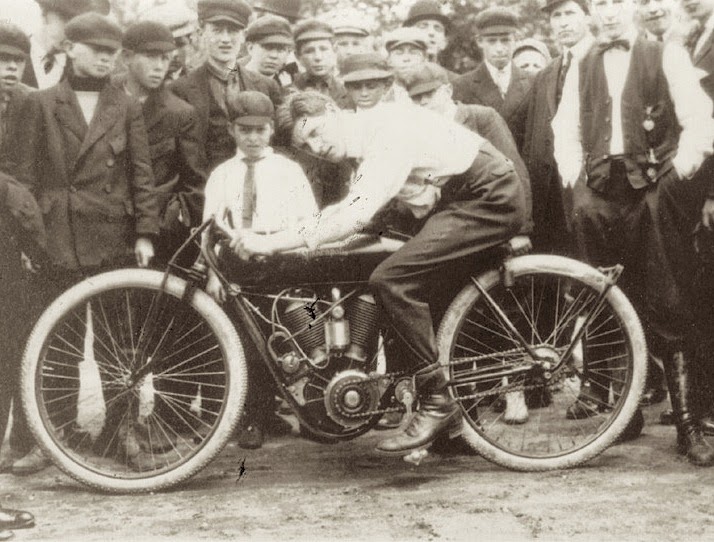

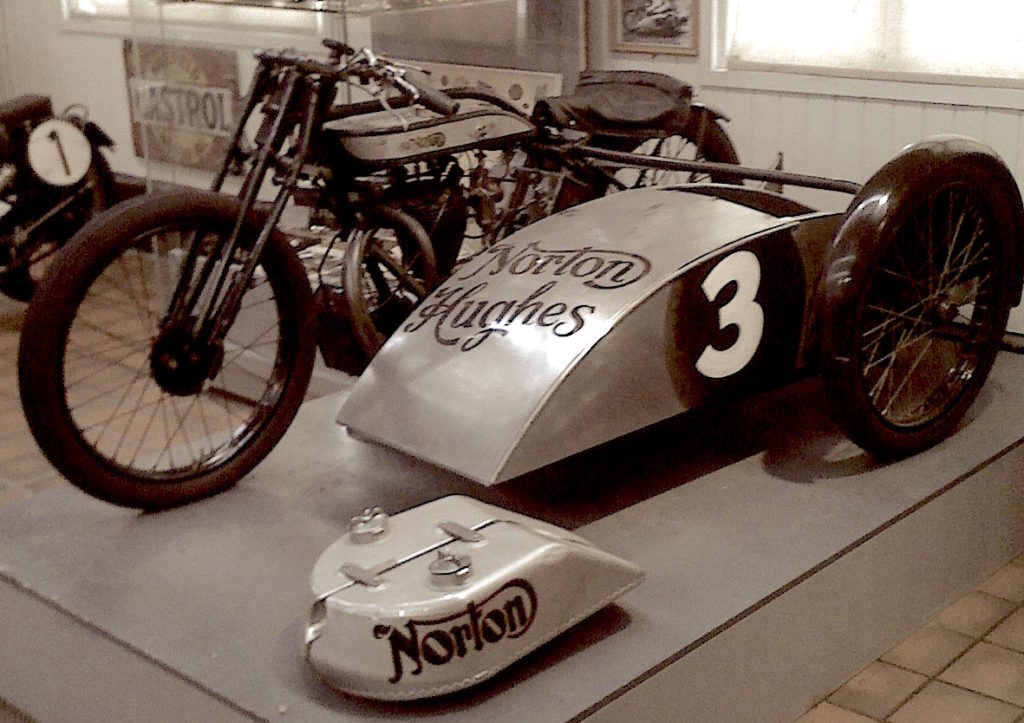

NLG: Brooklands' First Winner

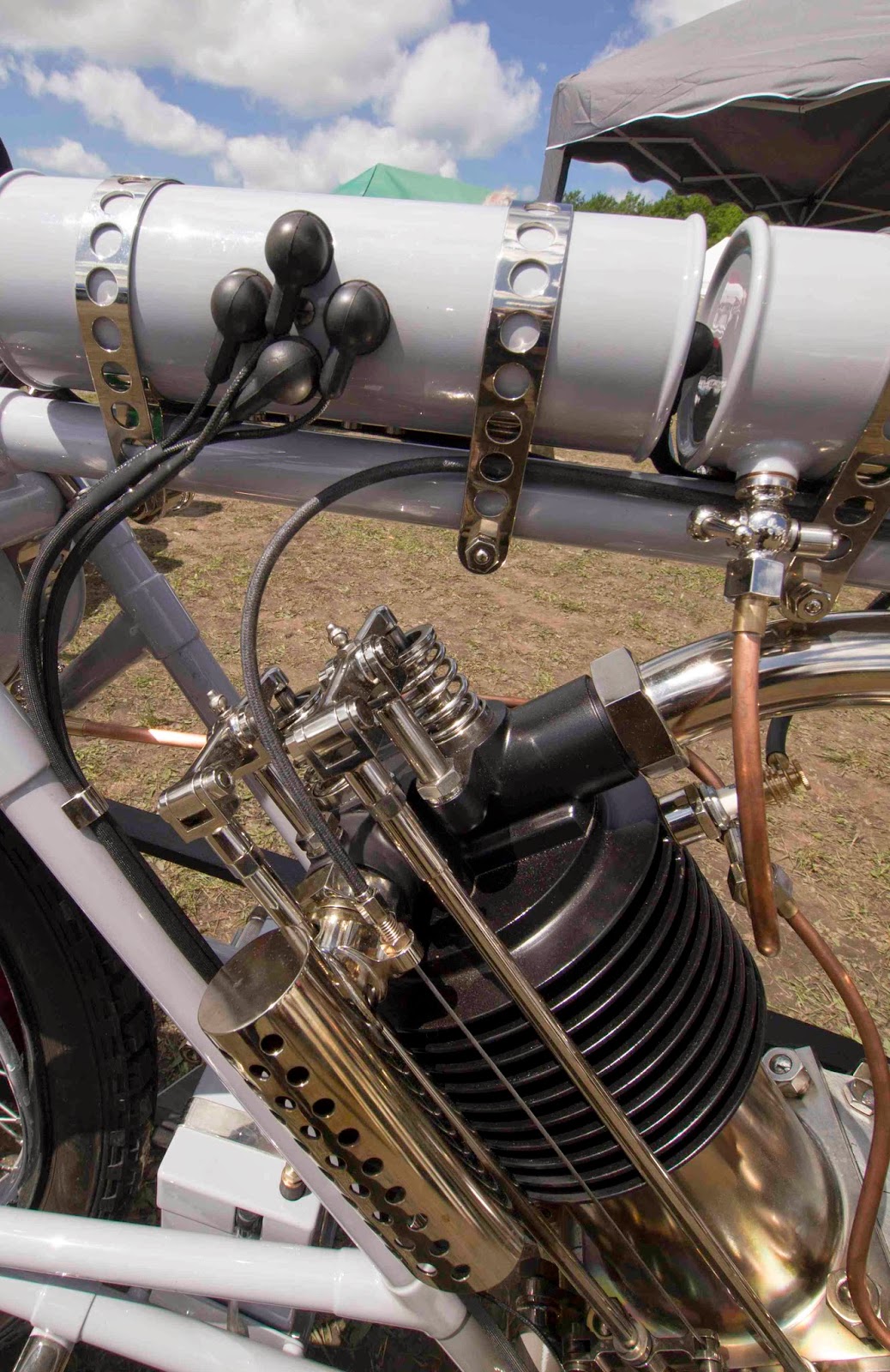

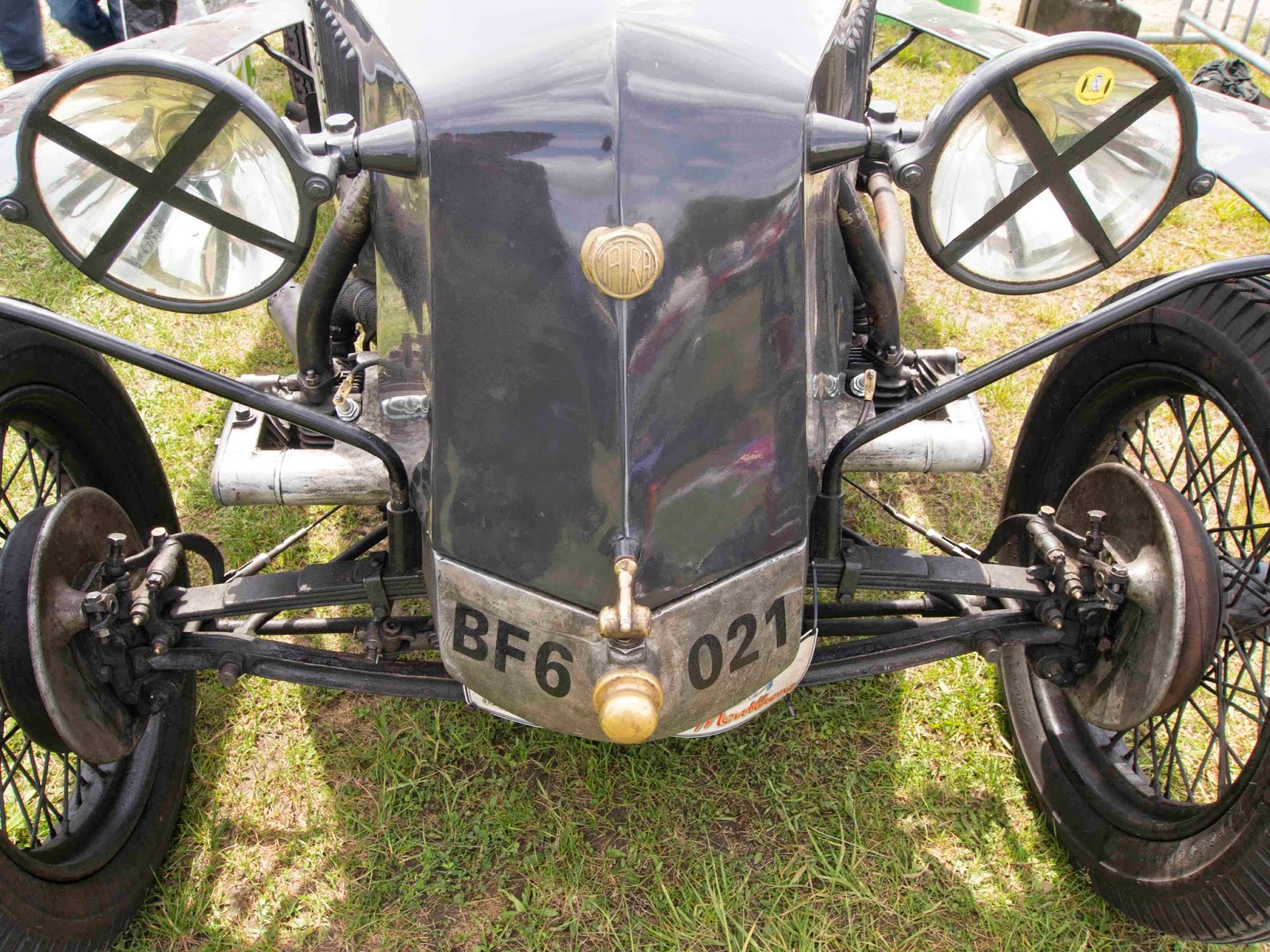

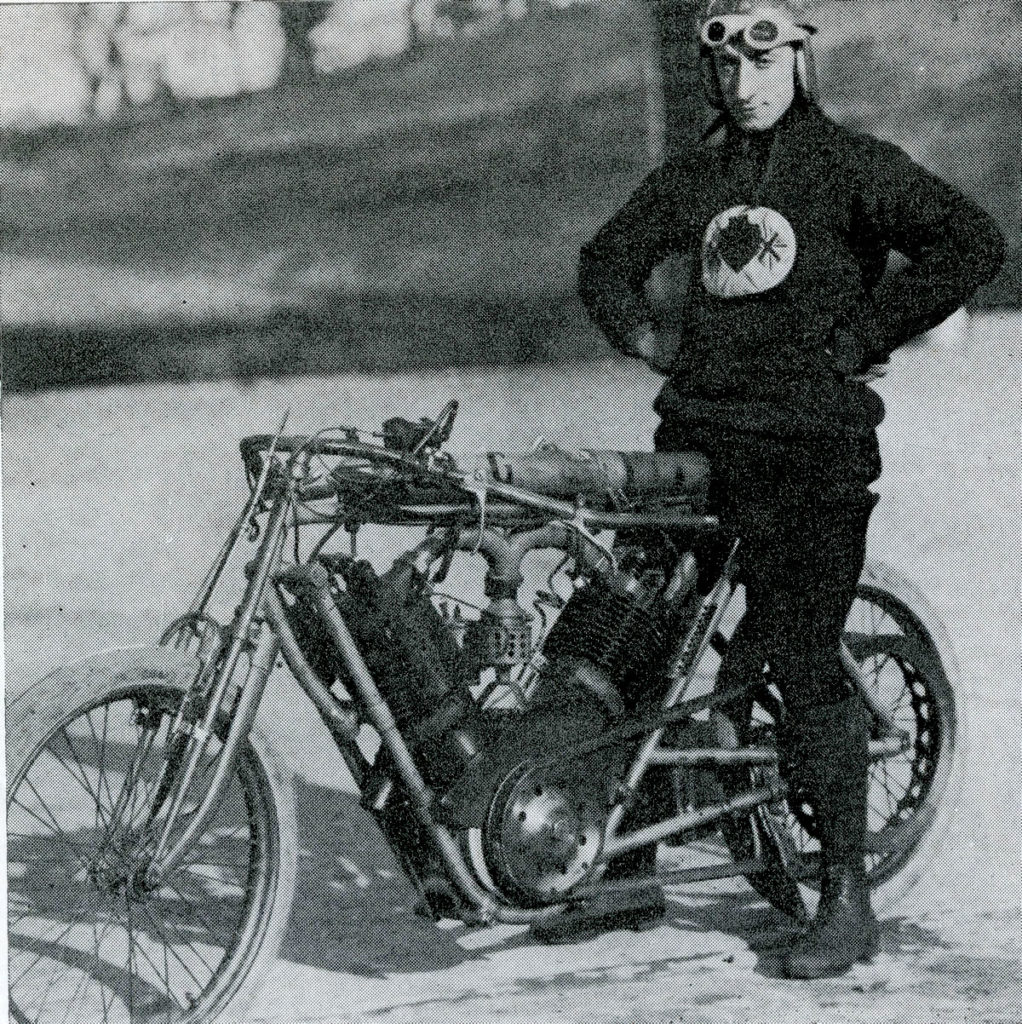

This amazing NLG (North London Garages) won the very first official race at Brooklands 100 years ago, on Easter Monday, April 20th, 1908 (apparently there was one unofficial match race the previous year). The track itself opened in 1907, but this first 'Motor Cycle Scratch Race', as it was billed, took place the following year, and was described thus; "Over 2 laps, 5 1/2 miles, for machines not exceeding 80x96mm per cylinder. Long start and finish". One hopes that not too many races required a 'short finish' at Brooklands, as the typical track racer had no front brake at all!

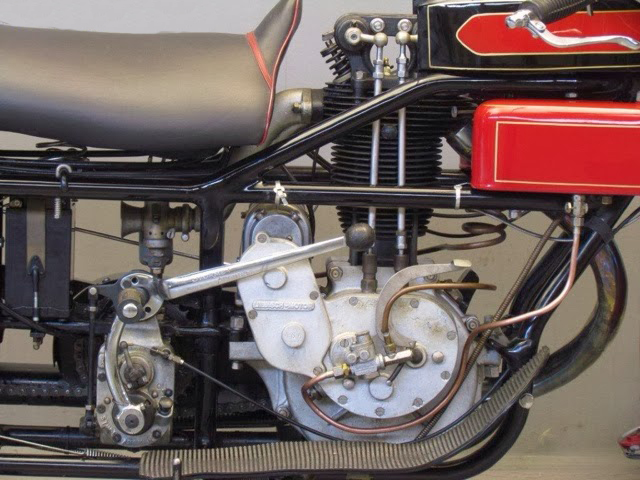

This NLG was raced by W.E. Cook (see photo below), but was owned by A.G. Forster, owner of North London Garage, the automobile repair works where Cook was employed. He competed against 20 other riders, including Charlie Collier, winner of the first Isle of Man TT the previous June (single-cylinder class) on the Matchless of his own make. Apparently though the Peugeot-engined NLG (shades of Norton's first TT winner - note the 'PF' cast in the crankcase - Peugeot Freres) walked away from the competition during the race, to win by over 5/8 of a mile; quite a distance for such a short event, with a speed of 63mph. The prize for the race was 20 Sovereigns - a fortune in those days (probably equivalent to $20k).

Another Peugeot-engined machine placed second in the race. The engine has a 80x94mm bore and stroke, giving a capacity of 944cc, using automatic inlet valves (ie opened by the suction of the piston in the bore), with cast iron pistons. The barrels have been copper plated, perhaps in hope of better cooling, and drilled through their fins. A French Longuemare carburetor is used, and below it can be seen the large brass contact breaker assembly for ignition timing, with the ignition coils mounted on top of the gas tank. The cycle parts are built from Chater-Lea castings, who supplied many in the motorcycle trade with their chassis fittings.

A look at the side of the tank shows the lever for the throttle, and in front of that a lever to control ignition timing, with finally the oil pump handle and tube. During the race on the notoriously bumpy Brooklands concrete track, the rider would probably have left the carb and ignition levers fully forward for flat-out running, but would have had to reach over from those wonderfully dropped handlebars to give the oil pump a press several times during the race. Interesting details abound on this machine, sorry I didn't get to take more detail pix (click on the photos for a better look), but note the individual cast aluminum 'mufflers' on the end of each exhaust pipe, the extensive drilling of all parts for lightness, and the big wooden battery case carried on the front forks. A truly elegant racer.

Anke Eve Goldmann: 'Soviet Racing Women'

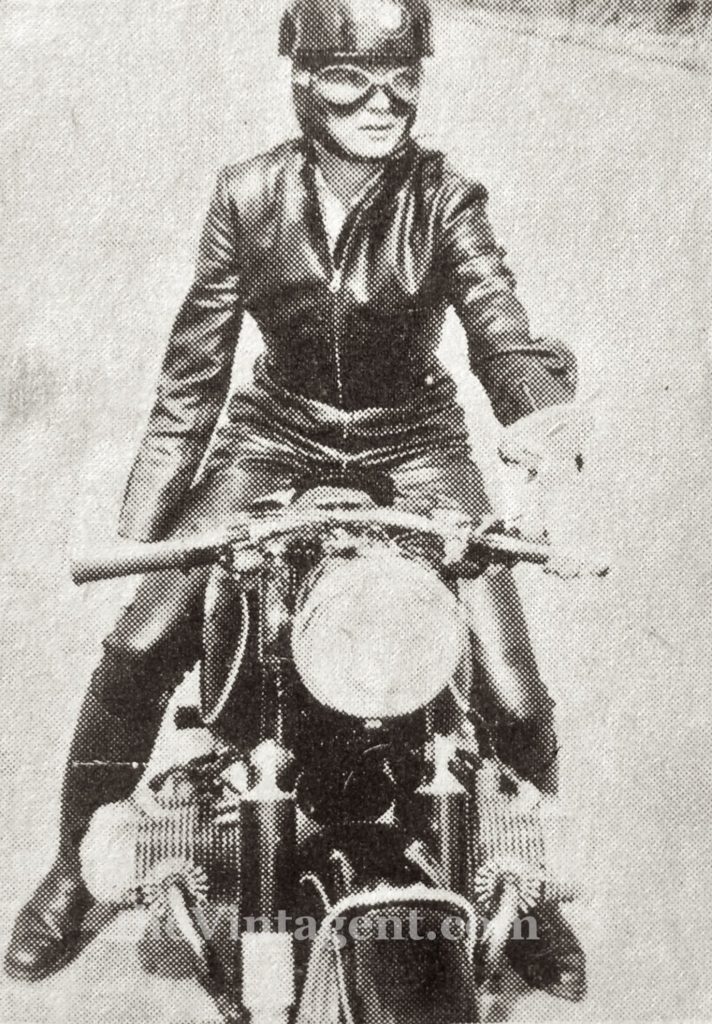

Everyone's favorite vintage moto-heroine, Anke-Eve Goldmann, is best known today for early 1960s images astride a BMW in her self-designed leather catsuit. Yes, she was stunning, and 2 meters tall (that's 6' 6"), and a very brave, independent woman, willing to bear the scorn of postwar German tongues, wagging at the scandal of merely being herself; enjoying motorcycles, wearing racing leather like the boys, and frequently beating them on the road and track. I've conducted interviews with people who knew her well in the 1950s and 60s, and gained a fuller picture of how this remarkable creature - still alive at 81 years old in Germany - came to prominence in a country deeply in shock from its experiences in the War. AEG, as she's affectionately known, prefers her privacy today, rebuffing all attempts at interviews or participation in a biography, but her story will inevitably be told...she's too bright a star to hide forever.

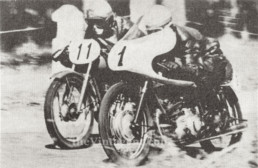

The tides of her acceptance in German society began to change when Goldmann started writing for motorcycle magazines around the world: Cycle World, Moto Revue, and Motorrad among others, documenting of her experience riding the Nurburgring, plus European race reports, etc. Her most intriguing article documents an all-but forgotten chapter in Soviet sports history: the Women's motorcycle racing circuit of the 1950s/60s. For a West German woman to document Soviet motorsport in 1962, while the Berlin Wall was being built, was a shockingly defiant act. As a result, this article never appeared in any European magazine, and only Cycle World in the USA published the story, as the bleak tensions of the Cold War ramped up dramatically, with Berlin as the focal point of a possible nuclear war between superpowers.

But Goldmann had no such political agenda; she wasn't a closet Socialist with Soviet sympathies, but was, rather, a feminist before that label was popularized. Her experience of being shut out of racing tracks because of her sex rankled as an injustice, as was the ridicule she experienced for daring to be a woman on a fast motorcycle, able to handle herself and her machine with 'masculine' aplomb. AEG, who helped found the Women's International Motorcyclists Association (WIMA) in Europe in the late 1950s, was the first and only Western journalist to document Soviet women's racing, with no need to comment on the irony of women being 'free' to race motorcycles in the Soviet Union, while she in the 'free' West was not.

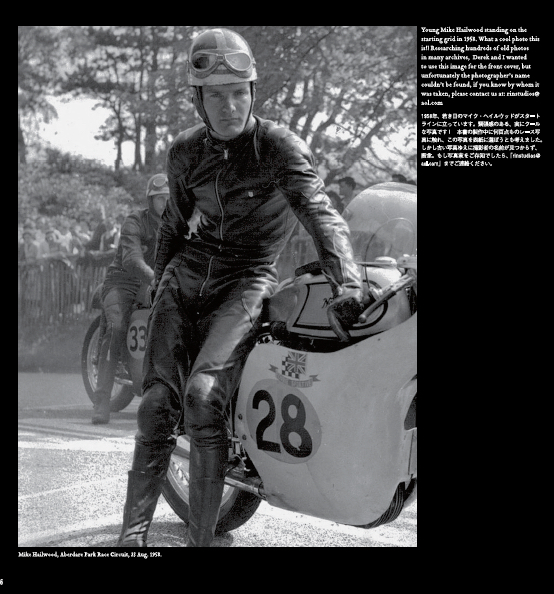

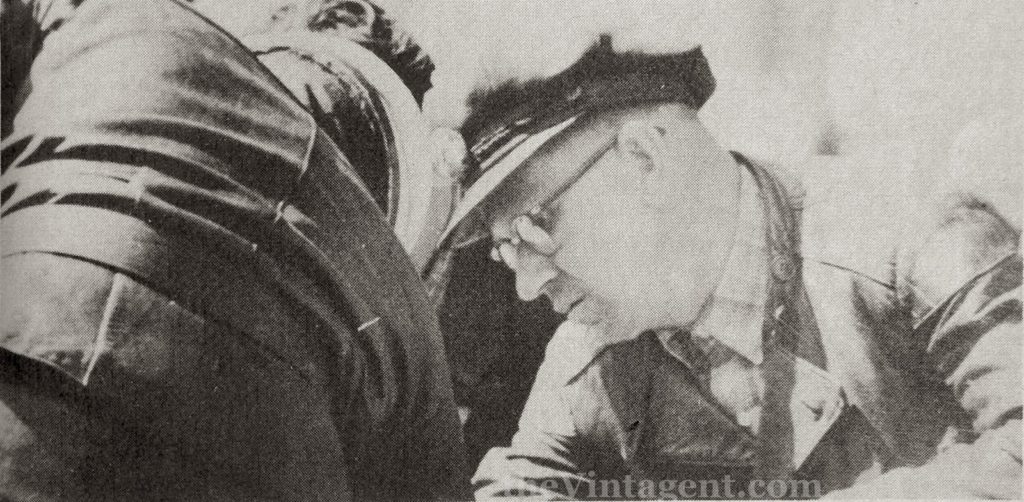

Goldmann had arranged in 1961 to visit the Soviet Union as a journalist to document women's motorcycle racing, but a visit from the American CIA (an attempt to recruit her as a spy) horrified her, and she cancelled the trip. Instead, AEG built up a correspondence with the Soviet women she documented, and relied on them to supply photographs and race results, plus the names of the riders with a few details, like their hair color...the habits of a patriarchal viewpoint die hard, and while Goldmann never referred to Mike Hailwood as 'blonde' vs. a 'gorgeous' Giacomo Agostini, she includes such notes as a way of distinguishing the characters in her report, which must reflect on the extremely limited information available to her...although it does add charm to the story.

Sadly, her Soviet correspondence and all related photographs were collected in an album which disappeared from her family's Swiss summer chalet in the 1970s, and this article is what remains of this unique period in motorcycling history. Here's the article in its entirety, reprinted from the October 1962 edition of Cycle World magazine:

SOVIET ROAD RACING CHAMPIONSHIPS FOR WOMEN

By Anke-Eve Goldmann

"How many motorcyclists in the Western world - male or female - are aware of the fact that in the Soviet Union women are enjoying their own road racing championships? While England is already exceptional in dauntless girls on short circuits, there are hundreds of female road racers competing regularly in Soviet Russia.

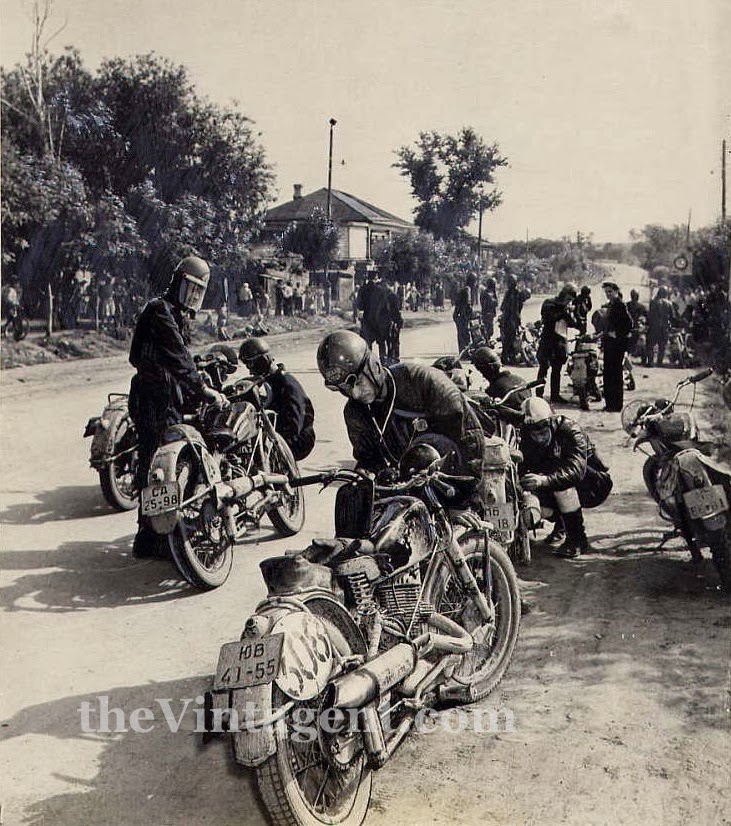

And the most enviable thing is that they have their own championship races. The first of them was held in 1949 on the lovely, 6.746km (4.189mile) road circuit at Pirita-Koze-Kloostrimetsa, near Tallinn, in Esthonia. For reasons unknown, that small country is the center of Soviet motorcycle racing. Naturally, no highly specialized racing mounts were ridden in that first meeting. The 125cc K-125, and the 350cc ISH-50 and IZH-54 two-strokes (very much DKW-looking), which developed about 7.5 and 14.5hp respectively, had solid frames and girder forks.Prytkova won the historical 125 races over 15 laps at a speed of 80.5kph (49.99mph), with veteran Lydia Jefremova second[was she a war or racing veteran? - pd'o]. Most girls lapped at below 70kph (43.47mph), and the best male rider at 86.76 (53.87mph). Irina Ozolina, of Moscow, won the 350 class at 89.76kph (55.74mph), ahead of Lydia Tratsevskaya.

Next year's 125 winner, Nina Mikhejeva, was faster than the best male had been in 1949. That strong, blue-eyed girl who took 7th place in 1949, won both race and championship at a speed of 86.6kph (53.77mph) and a record lap of 91.2 (56.63mph). With Nina, the most prominent of Soviet girl racers had entered the scene. Indefatigable, of great physical strength, and entirely fearless, this woman conceals high personal charm under very determined looks. Second place went to Armenian Tumanjam at 84.84kph (52.68mph), who V.Morosova, T. Trossi and Esthonian N. Ratasepp filled the next places. Irina Ozolina again won the 350 event, this time at 91.62kph (56.89mph) with a fastest lap of 93.3 (57.93mph). Lydia Tratsevskaya finished second.

In 1951 Nina Mikhejeva (whose name was now Susova)[recently married? - pd'o] shattered all records, riding her 125 faster than the male winner of the year before. She averaged 90.46kph (56.17mph) and pushed the lap record to 93.41 (58mph) in the 125 division, out-racing V. Morosova and L. Sviridova. A lovely girl came in fourth - Virve Gustel, of a famous Esthonian racing dynasty [Estonian readers - please clarify? - pd'o]. Tumanjan and Ratasepp did not finish. The 350 event was won, not by Irina Ozolina, but by T. Trossi who, taking things easy, rode to a safe win at 89.29kph (55.46mph). That miss Trossi can ride is shown by her lap record of 93.77 (58.23mph) established when Irina was still in the race. N.Nosenko beat Virve's sister, Ylme Gustel, for second place.

In 1952, both Nina Susova and Irina Ozolina returned to Moscow with their third championships secured. Nina, in top form, smashed all opposition. Though unchallenged, she took the checkered flag after 1 hour, 5 minutes, 2.3 seconds for a 93.35kph (57.97mph) average. A new lap record of 4.15minutes and 95.24kph (59.14mph) also went to her credit. Second place was taken by V. Morosova, who had been lapped by the dashing Nina. Mis Reichenbach finished third. The 350 race was won by Irina Ozolina at 96.01kph (60.62mph) and the lap record now stood at 98.72kph (61.30mph). Runner-up was Ylme Gustel; V. Petrova wound up third.

1953 became the year of the sisters Gustel. Nina Susova was out of the race on the first lap, and lovely Virve defended her first place successfully, averaging 89.02kph (52.28mph). Fastest lap in that race, at 93.18khp (57.86mph), was ridden by V. Morosova who, after a long stop in the third lap, hurtled through the whole field and finally beat Esthonian N. Ratasepp by a narrow margin for second place. Virve's sister Ylme was the winner of the 350cc class after Mrs. Ozolina had engine troubles. Ylme pushed the 350 record up to 97.56kph (60.58mph) and rode to a splendid 350 lap record of 99.67kph (61.89mph). Esthonian Tea Tahk grasped second place, in front o f N. Nosenko. Helju Kuunemae, bearer of a famous name in Soviet racing [more please! - pd'o], went out of the race with engine bothers for the fourth consecutive year.

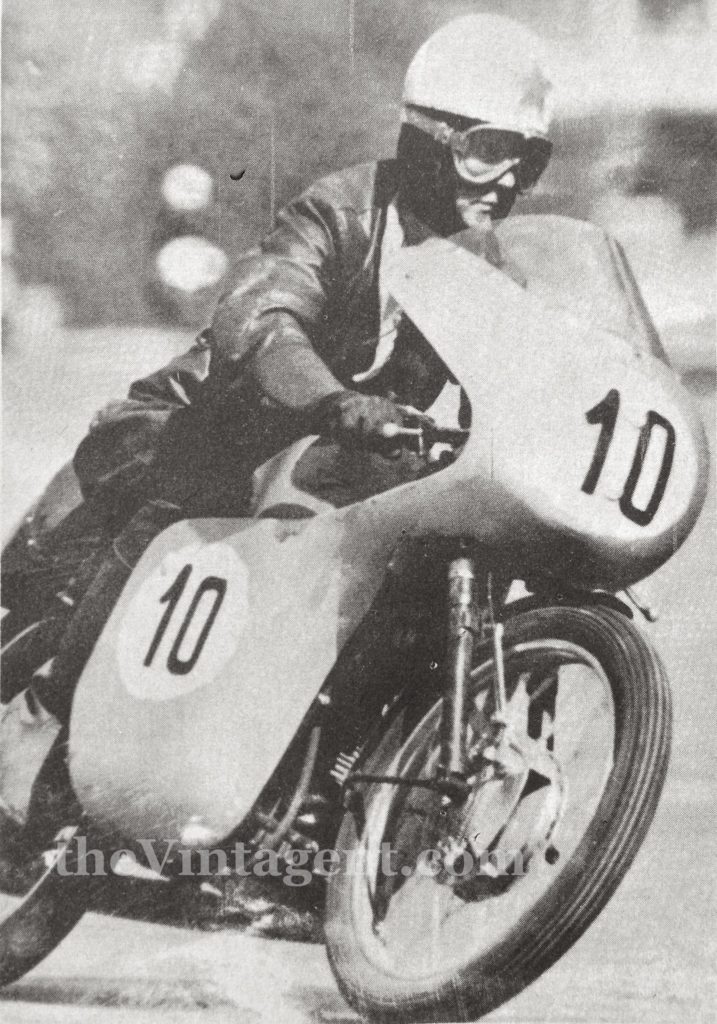

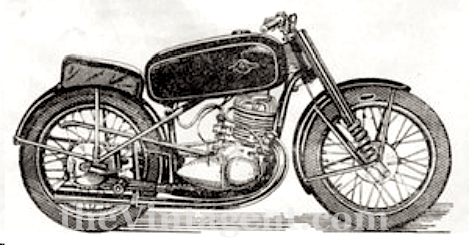

For 1954, the 350 class was abandoned. All girls now competed in the smaller class, and Irina Ozolina won the championship with a speed of 90.91kph (56.45mph) over Nina Susova and I. Tomin. In these years other changes also took place. Different road circuits had been prepared, and the best racers now made use of a new model, the S-157, a twin OHC single-cylinder affair, giving 14.5bhp and built on the lines of the Czech CZ racer. Fairing made their appearance, and the Russian girls met female road racers from other Communist countries, notably Hungary.

In 1955 Nina Susova struck back an won that year's championship, beating Irina Ozolina and Esthonian Evi Nugis, a beautiful fair-haired newcomer who was to become one of the most prominent racers of her country. After the 1956 championship had again been swept by Nina Susova, Evi obtained top honors in 1957, establishing a scintillating new record of 97.16kph (60.33mph) and also a lap record of 99.02 (61.49mph).

The championship was decided by two races for the first time in 1958 - at Leningrad an at Talllinn. The first heat was won by the indestrcutible Mrs Ozolina on her S-157 over blonde Evi Nugis and veteran Tratsevskaya. In the second race, Evi had trouble, so Irina was content to secure a second place behind Nina Susova which was all she needed to take the 1958 crown. Incidentally, no one knows for sure just how old Irina is, but she started motorcycling in 1939, and is now well over 40!

Three races counted for the 1959 championship - Riga, Tartu, and Tallinn. Nina had given up racing so it became a year for the 'old lady' again. At Riga, Irina managed to beat V. Petrova and local star Vilma Oshinja; at Tartu she was chased in determined manner by an unknown 20-year-old girl from Esthonia, Evi Freiwald, who also gave her a breathtaking fight in the third race, at Tallinn. Mrs. Ozolina won, but she had to try all she knew to keep Evi from winning - a girl who was born after Irina had already started to ride motorcycles!

The 1960 championship consisted of two heats: Tartu and Tallinn. The Tartu even was a terrific struggle. The winner was - well, who? - Irina Ozolina, who propelled her S-157 around the circuit at an average of 101.27kph (62.88mph). The lap record, however, was established by Visma Lapinja on an East German MZ at 109.57kph (68.04mph)! Visma took second place in the race at a speed of 100.15kph (62.19mph). Tea Tahk, on another S-157, was third. Evi Friewald had engine troubles. The Tallinn heat was won by Irina, too, at 93.97kph (59.88mph), while Latvian Erika Kiope beat Vilma Oshinja for their berth.

In 1961 several major changes were observed, the most notable being a ban on specialized racing mounts. This decision was taken to level the chances, and meant that star riders no longer were assured the fastest machines. 1961 was also notable in that it brought the 'Ozolina monopoly' to an end. Irina was defeated by Latvian racers. At Tartu, Vilma Oshinja seemed a safe winner when, in the last lap, Erika Kiope made a determined effort and won by a few yards. At Talinn, Irina tried to rescue her championship chances and gave Vilma a sparkling fight for victory, but Vilma won the race and the 1961 championship.

I do not know how the Soviet girls would look in races in Western countries. Without doubt their courage is comparable to the fearlessness displayed by Soviet International 6 Days Trial riders, but I think that their riding style and racing experience still lacks perfection. If given International racing experience the Soviet girls certainly could become racing competitors to be reckoned with, and I would give all the tea in China to see them race against this year's 50cc Isle of Man competitor Beryl Swain, and that dashing Californian, Mary McGee."

[Some notes on the machinery: The IZH 50 was introduced in 1950 as the latest iteration of, as AEG notes, the DKW-based two-stroke single-cylinder roadster, tuned for racing. The IZH 50 was built from 1950-56, and was a 346cc single with an aluminum cylinder and head, producing as she notes around 14.5bhp @4800rpm, with a 4spd gearbox and theoretical top speed of 115kmh (71.46mph). The IZH-54 was introduced in 1955 as a production road racer, with a lightweight rigid (tube) frame and teleforks and a tuned IZH-50 engine giving 18bhp. It was very light at 108kg (238lbs). There were few, if any, alternative road racers available in the 350cc class at that date

The S-157 racer was a DOHC single-cylinder based on the CZ. Here's what Mick Walker had to say in his 'European Racing Motorcycles' book: "The next Soviet racer was the S-157A, an interesting lightweight for the 125cc class. This was a dohc single with valves set at an angle of 50 degrees, measuring 28mm exhaust and 32mm inlet. The stroke was rather long at 58.5mm which with a 46mm bore gave a cylinder capacity of 123.6cc. When FIM President, Peit Nortier, visited the Central Automoclub headquarters in Moscow during 1959, the chief of the technical department told him that it was not intended to put the S-157-A up to the challenge the top Italian lightweights, rather to provide a production racer; and to this purpose a batch of 25 would be constructed toward the end of that year." Walker added he didn't think the S-157 was actually built, but he'd never read AEG's account from 1962!]

Instafamous / Instabroke

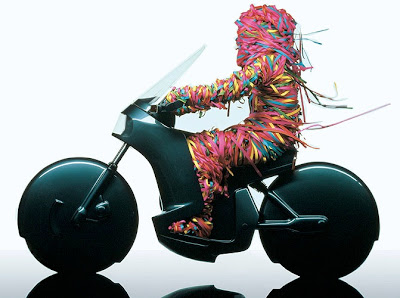

I've been writing a monthly column for Classic Bike Guide for over a year now, and I tend to focus my essays on motorcycle culture, when not simply poking fun. A few columns have hit a nerve, but none more so than my meditation on the Custom bike-building scene, and the struggles I've observed with my friends, trying to make a business of their craft, or art, or vision. The BikeExif post on the demise of Spain's Radical Ducati inspired my thoughts last March, when I wrote 'Instafamous/Instabroke', as did a conversation with David Borras, also of Spain, who's El Solitario is recognized globally, yet he and his crew daily confront the realities of running a business to support David's radical design sensibility. Chris Hunter of BikeExif asked to reproduce the essay, which I think is a first for his website; no motorcycle images! Not all my readers frequent BikeExif, but might enjoy the read. Thanks to Classic Bike Guide for ok'ing the BikeExif post, and this one too:

I’ve been mucking around with old motorcycles since the 1980s, and like many, financed my bike habit via the sport of Arbitrage. That is, turning a profit on a bike after giving it some love. It wasn’t an income; the only people living off the motorcycle game were (impoverished) moto-journalists and employees of legitimate dealerships. I knew lots of fellows, and a few ladies, who spent all their time repairing and modifying bikes, and none aspired to be anything but a garagiste. At the time, Von Dutch lived in a trailer, Ed Roth had long-ago lost his Revell contract, and only bands sold t-shirts. It never occurred to us that someday we’d be aglow with some sort of notoriety. But ‘some sort’ is now within the purview of every human on the planet, via the joys of InstaFame. A downloadable phone trick has the power to make us globally recognizable in weeks. Via the savvy curation of images, we trigger a mutual oxytocin drip in our fans and ourselves, liking and being liked, tapping away like starving lab monkeys, who’ve chosen the button for ‘attention’ over the one for ‘food’.

It’s fame, man, to the hungry end, and maybe even bigger when you’re dead; is that the ghost of TuPac or Indian Larry I hear laughing over posthumous sales? Don’t think I’m judging; I owe the mysterious gods of the Internet a debt of gratitude for my own lifestyle; let’s just hope I don’t owe them my soul. The shimmering dust of glamour has always coated parts of the motorcycle scene, and right now it’s falling on handsome, bearded guys wearing heritage work clothing and riding ’69-clone choppers or knobby-tyred customs, or girls doing seat-top acrobatics aboard same.

The original meaning of ‘glamour’ was the art of enchantment, a spell-caster’s ability to create an illusion around a person, place, or thing. And while the packs of self-paparazzing blogo-grammers crowding custom bike events are indeed beautiful and achingly cool, I fear our glamour is a spell cast in the mirror.

A mix of hopes and pleasures motivate today’s custom motorcycle builders; the joy of creativity mingled with glow of Web attention, and now there’s an established recipe for making a ‘cool’ bike, tested via the comments section on a hundred moto-blogs. It’s easy to mistake the whoosh of online chatter for a wind to fill your sails, and a virtual wind is exactly that, while selling garage-altered metal to strangers has always been difficult. Savvy shops sell logo’d up clothing and calendars and keyfobs, scattering brand stickers in an Autumn of moto-foliage… but even such sales will only pay the bills, not the salary of a desperately-needed employee – or your own.

There are two ways to profit in business; large sales volumes with small profit margins, or high-end retail, and the successful moto-businesses sell the tanks and levers and rearsets the Wannabes need for an InstaFamous custom. At the rich end of the spectrum, the market for hundred grand choppers evaporated in 2008, and I know exactly one builder who’s sold an art-gallery motorcycle for big bucks. Every other shop, then, is in competition for a limited audience, even if it seems at times that ‘everyone’ thinks we’re cool and ‘everyone’ wants your bikes…but is that the magic mirror?

The first signs of iCustom casualties have recently appeared even in the luminous portal of Bike EXIF; shops going belly up, euphemistically ‘starting other projects’, i.e., jobs which pay. It hasn’t exactly been a Gold Rush (that’s happening in the App-creation world itself), and I know young bike builders don’t expect to get rich. Still, it seems the business of pushing aesthetic boundaries with a motorcycle is best trod with a trust fund springing your step, or proceeding with deep humility and little expectation of worldly increase; the hackneyed rule for artists. I’ve spoken with genius motorcycle builders whose controversial but gloriously innovative customs have netted them almost zero sales. A ‘like’ isn’t a dollar. But then again, as they slowly go broke or accustomed to reduced circumstances, the refrain is ‘there’s nothing I’d rather be doing’.

The coolest bike boom since the 1970s has kids buzzing like bees at Wheels + Waves, DirtQuake, and Born Free, and featured in popular books like the ‘The Ride’, to which I contributed. Riding bikes while young, beautiful and creative is a heady cocktail, as is the glamour of InstaFame. But let’s not confuse the rain of electrons, following our every move, for a rain of cash. Because in the end, bikes are just motorcycles, but business is business."

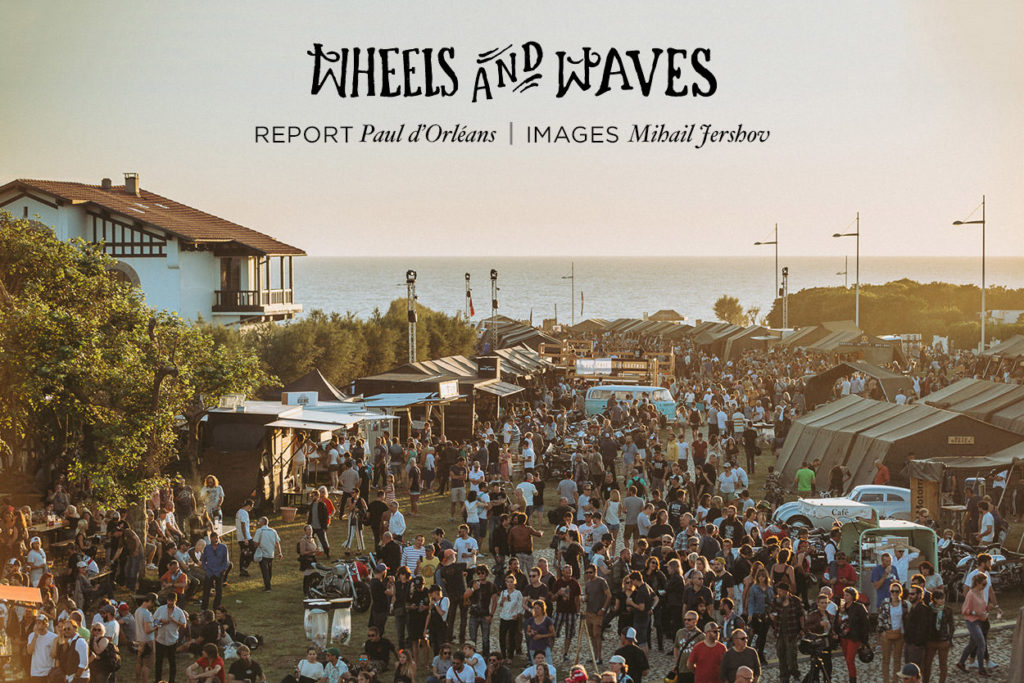

Wheels&Waves 2017: The Best Yet

Story by Paul d'Orléans - Originally published in BikeExif - Photos by Mihail Jershof

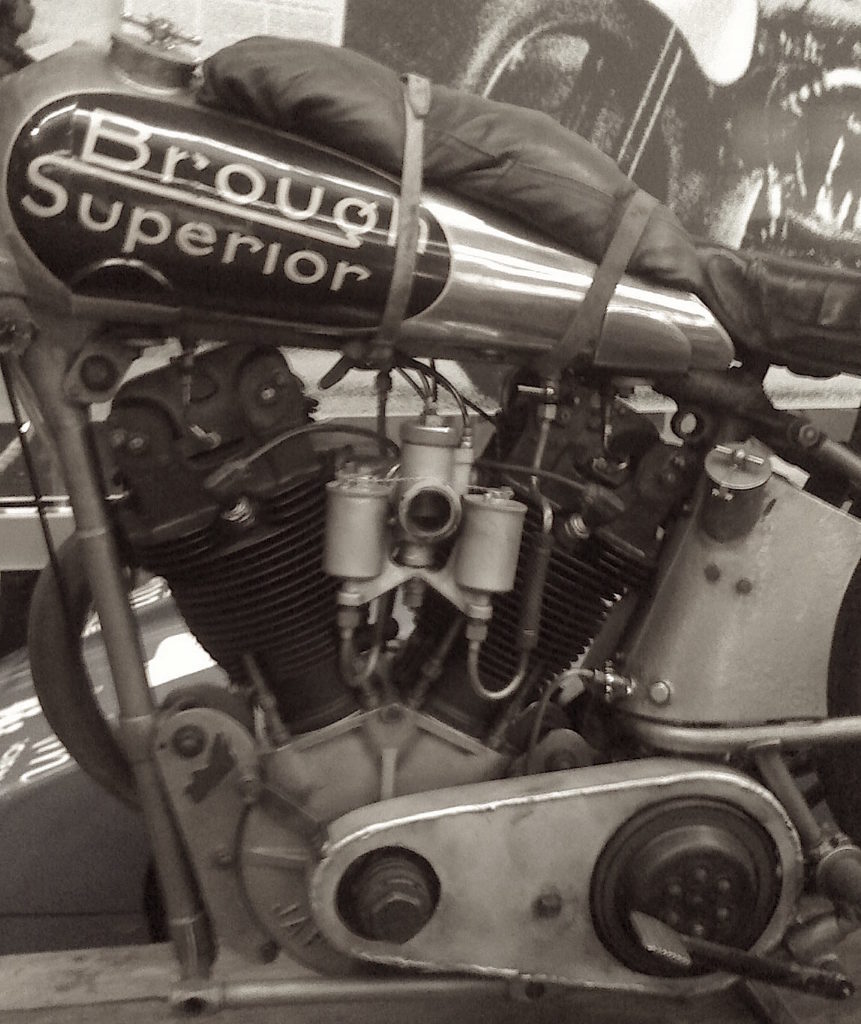

A banner hung outside the ArtRide exhibition stated, ‘You are not in France, you are not in Spain; welcome to Basque Country.’ At the 6th iteration of Wheels&Waves, the sign should read ‘Southsiders Country’, as 20,000 guests of this festival of surf/moto culture invade the sleepy town of Biarritz, filling all the hotel rooms, Airbnbs, and camping spots, plus every bar with a sidewalk. The Basque region isn’t a hotbed of alt.custom culture, and is a long way from Paris, Berlin, or Milan, where you’ll find the majority of European custom shops. But a surprising number of folks ride to the event, on everything from vintage Brough Superiors to the latest hyper-café custom Ducati. They come, I think, as much for what isn’t at W&W – no obnoxious branding, no OEM industry hard sell – as what is; a mellow, carefully curated series of exhibits, races, and rides.

“Our event is about motion” is the mission statement of Southsiders MC founder Vincent Prat, chief of the triumverate (with Jerome Alle and Julien Aze) who organize this legendary surf/skate/moto festival. You’ll need motion to see it all; most of the highlights are an hour’s ride from Biarritz, except ‘the village’ at the Cité de l’Ocean, a series of military tents stretching from this wave-form cultural center to Milady beach. Prat cut back on stalls by 30% this year, to keep the quality high for clothing, scarf, bag, board, and bike vendors; there wasn’t much overlap in the offerings, and what was present was really nice stuff, if not cheap. A big stage held live music afternoons and evenings, the skate ramp was always busy (with legends like Steve Caballero dropping in at random), and the indoor cinema screened fresh material like ‘Sugar&Spade’, ‘The Ended Summer’, and ‘Crystal Voyager’ from 1972 - a legendary George Greenough film, the first shot inside a wave, with a full side of Pink Floyd’s ‘Meddle’ vinyl as soundtrack.

The second ‘El Rollo’ flat track race at San Sebastian’s hipodromo was quadruple the size of last year, with a mix of serious competitors and sloppy day-racers. The races were short enough that it wasn’t a mess, and the mix of machines ranged from the new Indian 750s (currently dominating professional races), to vintage Trackmaster specials with Triumph or BSA power. We must all bow towards Sideburn mag for defibrillating this sport; proof again the custom scene is the lifeblood of the motorcycle industry today. Also refreshing; the mix of age and sex of the competitors, from gnarled vets to fresh young things like Zoe David on her Trackmaster pre-unit Triumph T100.

El Rollo is the first event of Wheels&Waves, and a great start to the week, on Wednesday. Thursday is the official opening day of the ‘village’, and in the evening another ride to San Sebastian is required for the ArtRide exhibition, held on 3 floors of an old fish-packing warehouse in Pasaia. It’s a mix of fresh custom and vintage bikes, photography and other art, and film/performance. A terrific, enormous montage of vintage MX and surf photos, plus surfboards and suspended racing Velocettes from the mid-1960s, were an homage to Richard Vincent, a surfer/racer from Santa Barbara, best friends with George Greenough, who filmed his racing, while Richard filmed him surfing. With professional equipment, Vincent documented an ideal SoCal life, which was dramatically halted by the draft. He was badly wounded in Vietnam, and his bikes, boards, photos and films sat for 50 years. Wheels&Waves was their first exposure since 1967; a short film about Richard Vincent was screened beside them, ‘The Ended Summer’ by David Martinez (full disclosure; exec produced by TheVintagent).

The Punks Peak hillclimb (an uphill sprint bent in the middle) has spawned a host of imitators, so the ‘El Chupito’ race spices up the pre-’50 to Powerbike mix of racers. Costumes are required to race your 50cc demon, and this year the theme was ‘Superheroes’. All sprints should be done in costume! Especially as sprints grow faster and more serious annually; a few dirty tricks were played, like loosening clutch lever pivots, and one rider seemed hell-bent on forcing his matches off the road – fine but for the barbed wire fencing. One walkaway crash and some hairy moments didn’t dampen things, and the premier event was won by Katja Poensgen – proving women riders rock hard.

Saturday is the all-day DIY rideout into the Pyrenees, and clumps of riders criss-crossed the mountains all day, semi-lost, but with perfect weather this year nobody complained. The views and snaking roads through thousand-year old stone villages, plus the inevitability of a great Basque lunch, make this ride a highlight, and the reason many return to the area. Back at the village, a casual display of exceptional new customs dotted the field, parked without display cards, which made photo IDs difficult, but added to the casual feel, and implied they were actually ridden. Clearly, as Vincent Prat stated, Wheels&Waves isn’t about the show, it’s about the go.

'Scorpio Rising'

Unless you're a serious film buff, you probably haven't seen the work of. Kenneth Anger (below), whose short films have profoundly impacted cinema, advertising, and pop culture. Since 1947, when he was 17, he has been experimenting with difficult and obscure subject matter, using his own milieu as his inspiration, and his cast.

I first saw Scorpio Rising almost 30 years ago at the behest of my pal Madeleine Leskin, who went on to work at the Berlin Film Festival; she urged me into a late-night screening... I've never forgotten the disturbing/alluring quality of the film.

You'll see Anger's visual influence on later movies like Easy Rider (1969), Kathryn Bigelow's The Loveless (1981), George Lucas' American Graffiti (1973) and Martin Scorcese's Mean Streets (1973). Specifically, his camera gazes adoringly at material objects, weighting them with an iconic, erotic power. Although never discussed as such, this camera work probably had it's greatest impact on TV advertising! His films remain almost unknown to a broader audience, and ironically his book 'Hollwood Babylon' (1974), detailing the sordid underbelly of the movie industry, is his most famous work.

His movies are difficult, non-narrative, and certainly non-literal, almost dream-like (in fact the soundtrack of his ode to SoCal automotive culture, Kustom Kar Kommandos, is the Paris Sisters' 'Dream Lover').

Scorpio Rising was completed in 1963, and its central character, Scorpio (Bruce Byron), is symbolic of the mythos of post-Wild One American Bikers. It's hardly flattering, as he projects a homoerotic, sadomasochistic aura, snorting methamphetamines from a salt shaker, humiliating a man at a party, and defiling a church. Through jump shots to clips of other films (including The Wild One and a very bad black and white Jesus biopic), comic strips, and nazi imagery, Scorpio is alternately compared to Jesus, Hitler, and the Devil. Pop culture icons like James Dean and Lucky Strike cigarettes wallpaper the scenery.

It was considered obscene in the day, but now we're all horribly jaded, and it merely seems shocking! Try to put yourself in the mindset of 1963 - Anger is a sly one and it's difficult to tell if he's celebrating Scorpio, or if he considers Scorpio a figment of a frightened citizenry's imagination - everyone's fantasy of what Bikers are Really Like. Using such imagery doesn't constitute an endorsement!

Scorpio Rising is 28 minutes long, and requires a bit of patience; its an avante-garde piece by a filmmaker who is way out on a limb. It still has the best 'title sequence' of any biker film, hands down. With its great period soundtrack (referencing the action of course), it's really the very first Music Video, predating the genre by a full 15 years, although no Music Video was ever quite like this again...

Egli-Vincent for YSL

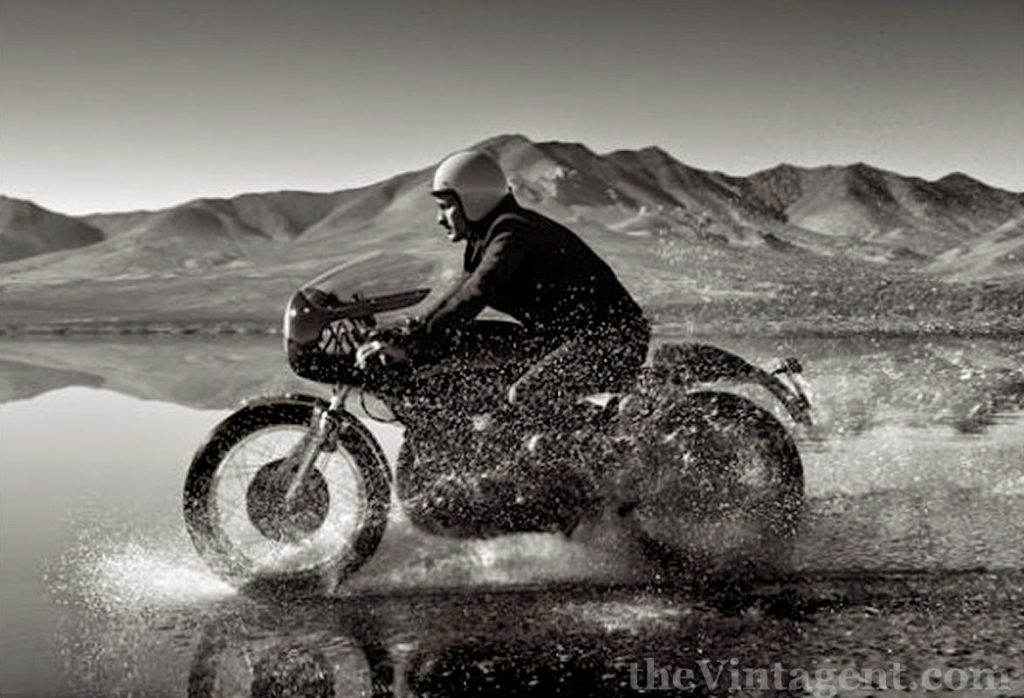

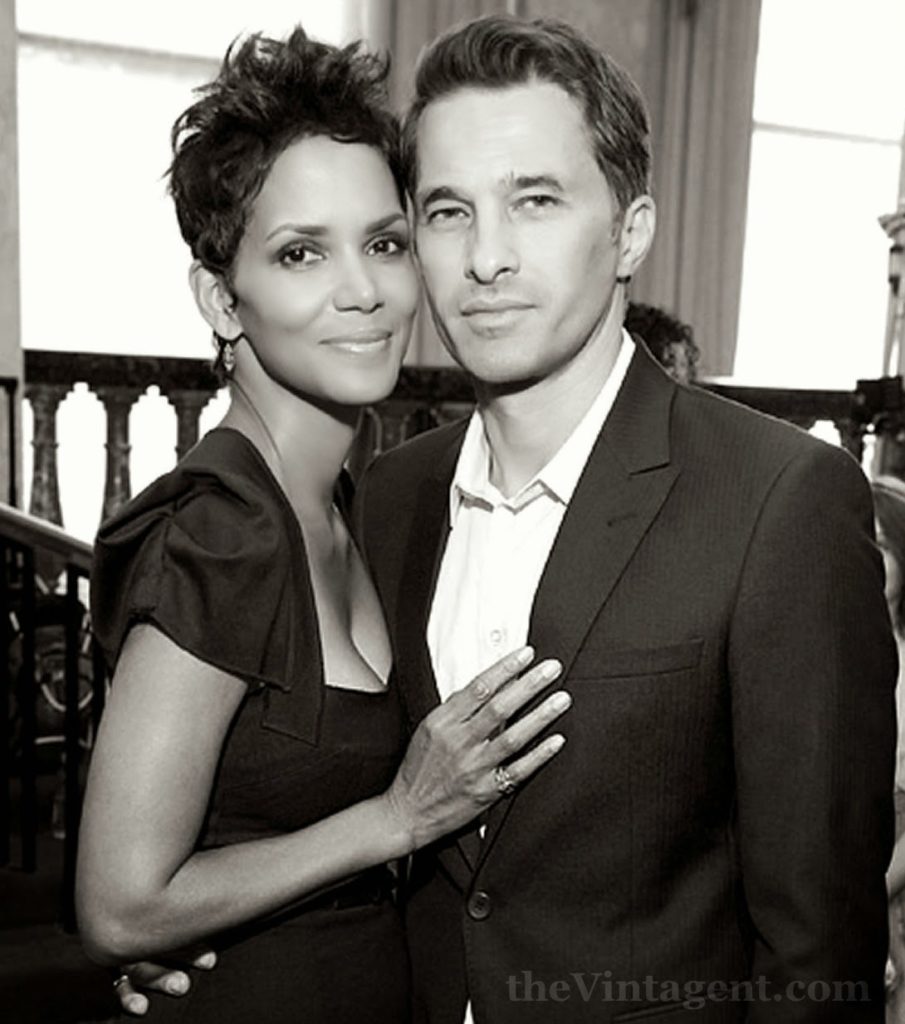

The new ad campaign for YSL fragrance L'Homme Sport features French actor Olivier Martinez riding a Godet-Egli-Vincent Black Shadow through the Mojave desert just east of Los Angeles. The bike is a Patrick Godet creation (the only officially sanctioned builder of new Fritz Egli frames), and uses fresh-cast engine cases for a capacity of 1330cc, giving around 110hp...which gives stunning performance, especially with an all-up weight of less than 200kg. While Godet has built and raced Vincents for decades, his series production of complete Godet-Egli-Vincents began in 2006, with financing from his partner, the French singer Florent Pagny. The new-spec engines can be ordered in various capacities, with the example used in the YSL ad campaign the largest and most powerful street machine offered.

Michael Lichter and I featured this very machine last year in our 'Ton Up!' exhibit at Sturgis, and it garnered plenty of attention with its menacing all-black livery, half-fairing, and upswept Gold Star exhaust pipe. You can examine the bike in detail in Michael Lichter's stunning photography within our book documenting that show, 'Cafe Racers' (Motorbooks 2014). The stunning black Godet-Egli is considered by many to be the ultimate vintage café racer, and can be ordered/purchased for less than the cost of a restored 'standard' Vincent Black Shadow these days...I know which one I'd rather have! But then, I have a café racer heart...

In the ad shoot, Olivier Martinez, whom Americans might know as the husband of actress Halle Berry, rides the machine himself with no stunt doubles (as per the Chanel ad campaigns with Kiera Knightly featured previously in The Vintagent), at times through an artificial water ford for dramatic effect. Enjoy the 'making of' video below, which gives an idea of how much effort/money is required for a simple fragrance ad campaign, which can typically budget $15-20M for a single fragrance... but then, perfume is a hugely profitable, mega-$Billion industry, selling what is basically scented water in a groovy bottle, and needs the romantic associations attached through advertising...

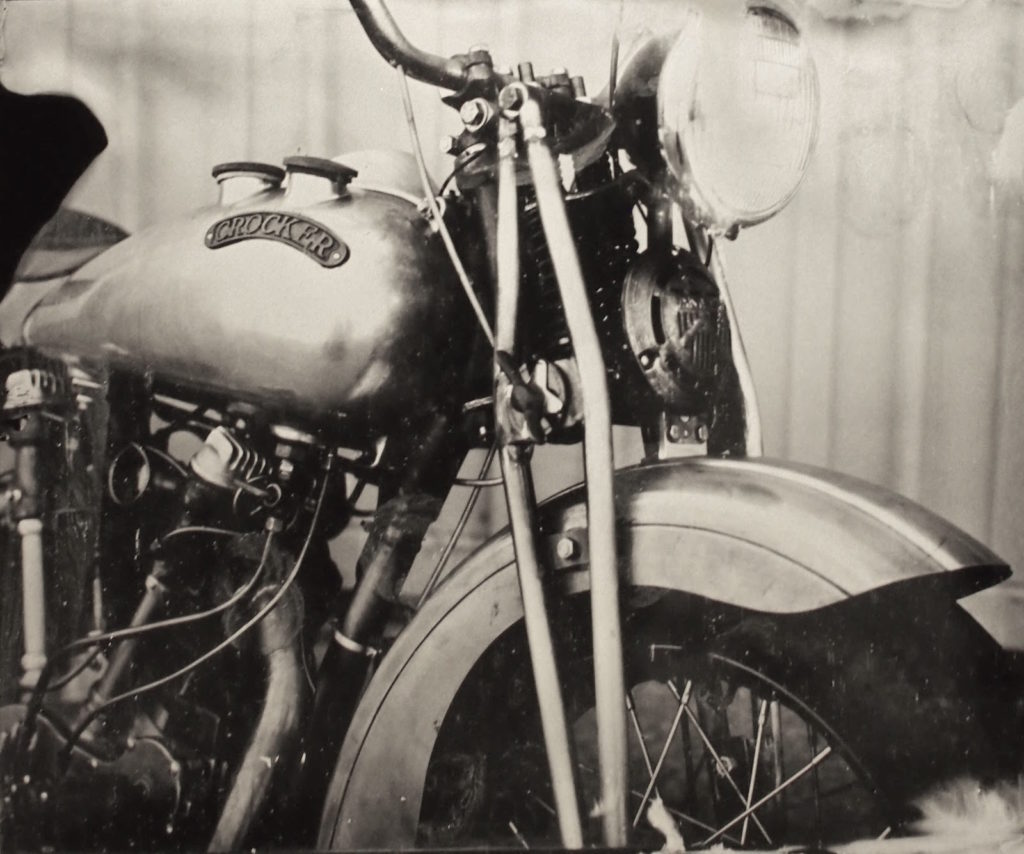

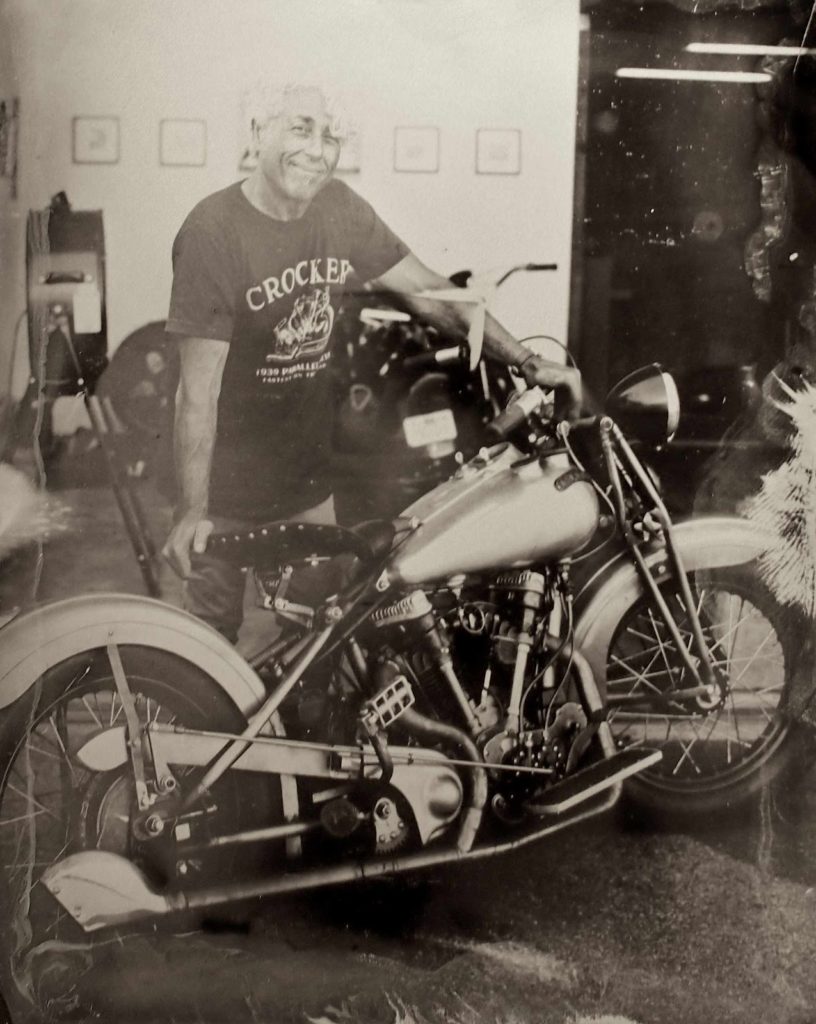

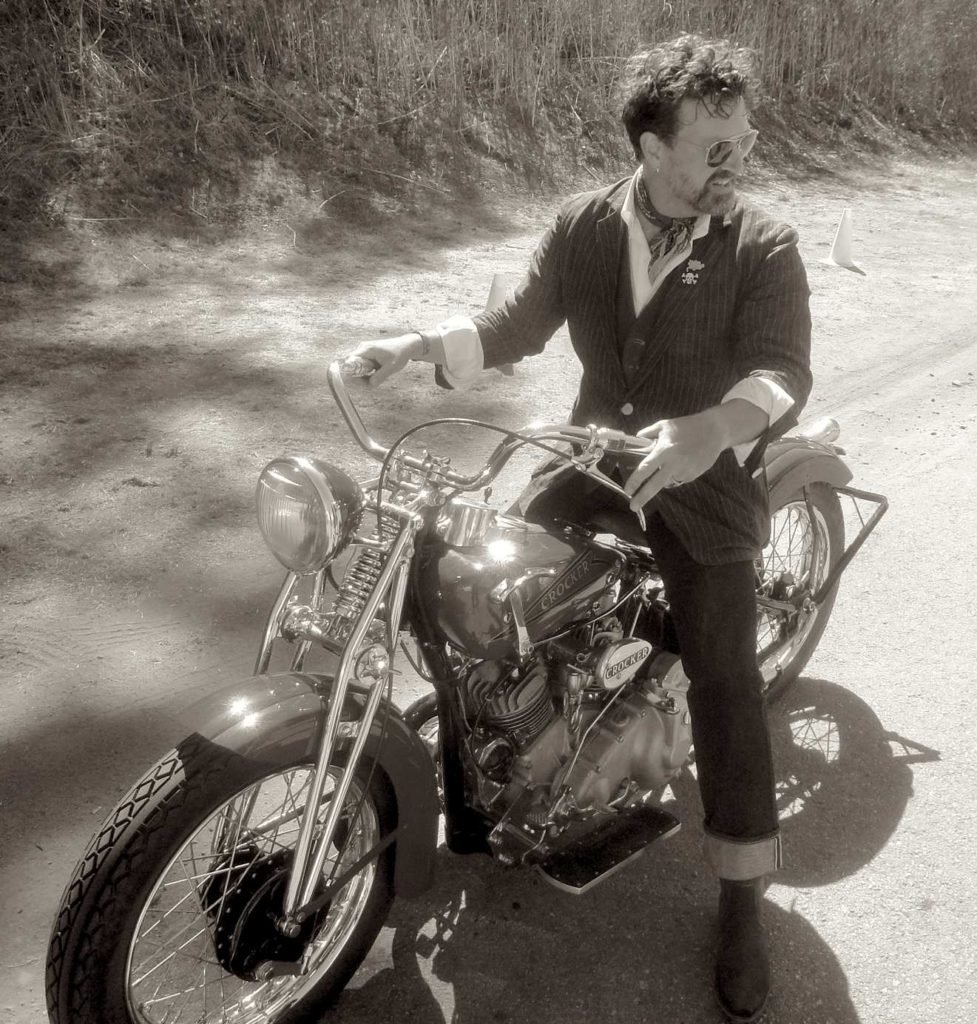

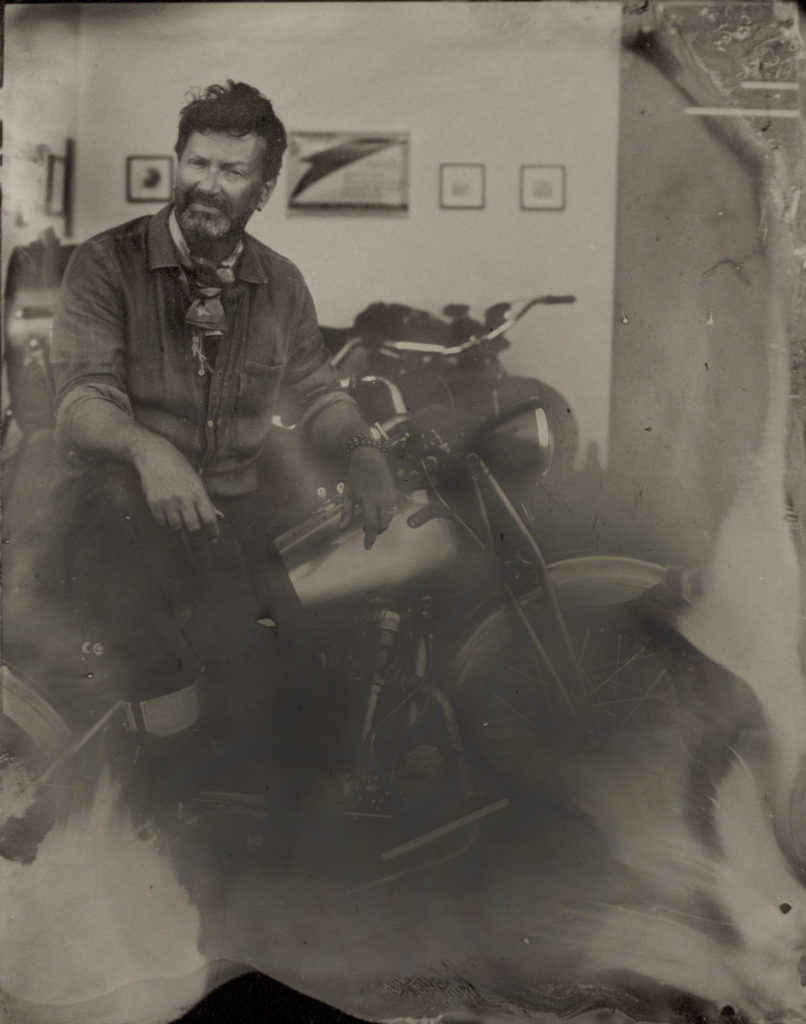

Road Test: 2012 Crocker Continuation

[/caption]The new 'continuation' Crocker motorcycle was unveiled at the Quail Motorcycle Gathering in May 2012, and Michael Schacht, who owns the Crocker Motorcycle name and built that first prototype, offered me a test ride next time I was in LA. Can’t pass up an opportunity like that, so I met Schacht at his warehouse/assembly shop, where sat the rough makings of the next 15 Crocker v-twins. Yep, he’s already making a limited run, ‘whether I have orders or not, I’m just going to build them’. Schacht has invested heavily in cash and time and reputation to make the patterns and cast the parts necessary to build a whole motorcycle, and that first Crocker Big Tank discussed in Cycle World that May was made from the same batch of rough metal seen in these photos.

The Road Test was combined with a wet plate/collodion photo shoot; here Paul d'Orleans is captured on wet plate. [MotoTintype.com]

The Road Test was combined with a wet plate/collodion photo shoot; here Paul d'Orleans is captured on wet plate. [MotoTintype.com]

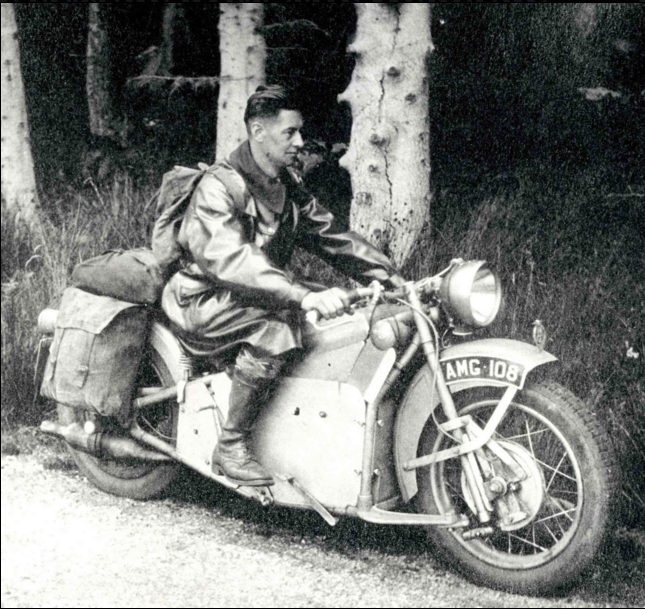

Alternative Motorrad Konzept

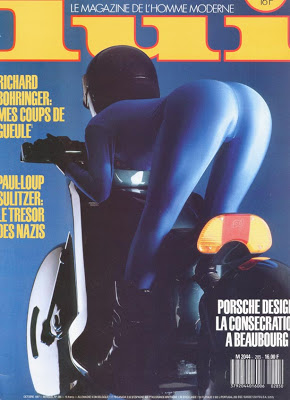

As part of a special exhibition celebrating 40 years of the Porsche Design Studio, the new Porsche Museum in Stuttgart, designed by Delugan Meissl Architects of Vienna (Porsche Design doesn't yet do buildings apparently) is exhibiting a few iconic and experimental projects, which includes the 'AMK' - Alternatives Motorrad Konzept - of 1978. The design brief was a two-wheeler with crossover appeal to automobilists... a project attempted by dozens of motorcycle manufacturers from the very first days of motorized transport. The 'two wheeled car' has met with very little success over the past century, as motorcyclists prefer Actual motorcycles, not an emasculated version dreamed up by automotive stylists frightened of riding.

The AMK was constructed around the venerable Yamaha SR500 (whose little brother, the SR400, just passed a marker as the third-longest produced motorcycle ever, according to my reckoning), and incorporates automotive designer's 'ideals' of total enclosure of wheels and bodywork, to calm irrational fears of spinning rubber and ugly/scary mechanical parts. The resultant machine retains an undeniable appeal (Porsche Design are a talented bunch after all), but in 1979 when the AMK was mocked up, this was radical stuff, penned 10 years before Honda débuted their 'Pacific Coast' to a reception of thundering yawns.

Regardless of the long history of failures in the auto/moto hybrid genre, the AMK has undeniable visual appeal. It looks contemporary even today, garnering the attention of the custom bike universe, via BikeExif. Students of engineering know, however, that total enclosure of wheels, engine, and fairing is a recipe for serious mis-handling in a side wind, and on a stormy highway the AMK would undoubtedly prove dangerous handful. Porsche kept a hand in motorcycle design by helping out Harley Davidson with various projects, most notably the VR1000 Superbike racer and 'V-Rod' VRSC engine.

In the end, the successful 'crossover' two-wheeler has always been the scooter, that charming sub-branch of motorcycling which offends no-one. BMW grasped the concept with their 'C-1' scooter of 2000, which had a short production run, now superseded by another range of 'Maxi-Scooters' (the C600 and C650), which will do over 100mph! Men in suits and ladies in heels feel more comfortable astride small wheels and total mechanical enclosure, while Motorcyclists continue to prove a breed apart.

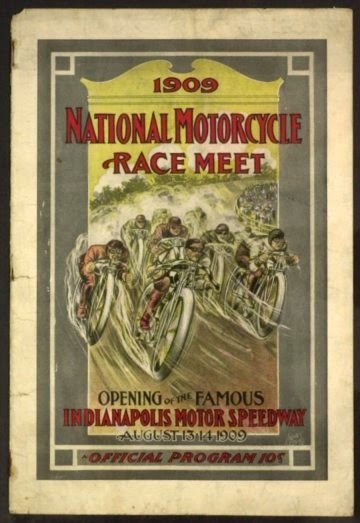

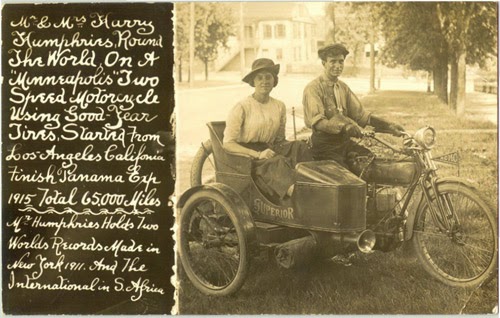

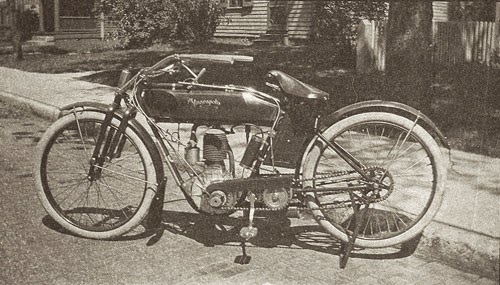

The Remarkable Minneapolis

The brothers Jack, Walter, Anton and Paul Michaelson, while not the first pioneers of American motorcycling, still managed with their small Minnesota company to introduce significant innovations to motorcycling, all of which were later adopted by the industry. Innovation doesn't always equal success, though, and while their 'Minneapolis' and 'Michaelson' brand motorcycles are very rare today, they deserve a place in the motorcycle history as important contributor to the progress of technology.

The Michaelson brothers joined the small ranks of Minnesota motorcycle manufacturers in 1908, when they built a brick factory at 526-530 Fifth Street South in Minneapolis, across the Mississippi river from the Thiem Manufacturing Co. (in the 'twinned' city of St. Paul). Thiem, who'd been attaching small engines to bicycle frames since 1900, provided the Michaelson's first engines, which were the ubiquitous 316cc single-cylinder F-heads with ‘atmospheric’ inlet valves. They called their motorcycle 'Minneapolis' after their home city. According to Anton's gradson Ky 'Rocketman' Michaelson, Jack was president and treasurer, Walter the vice president, superintendent, and machinist, and A.L.Kirk was secretary.

The Michaelson brothers also purchased V-twin engines from the Aurora Automatic Machinery Co. (Thor), another bedrock of the American motorcycle industry. Aurora had been building Oscar Hedstrom's Indian engine design since 1901, since his partner George Hendee, who'd been building bicycles since 1889, didn't have the general engineering facilities required to cast and machine motors. Hendee had all the facilities to build the heavy-duty bicycle chassis, but Aurora built their engines through 1907, after which Indian took over all its own production. Part of Aurora's deal with Indian was licensed production of the Hedstrom motor, an F-head (inlet over exhaust) with 'atmospheric' intake valves, in single and twin-cylinder form, which they sold as their own 'Thor' brand, and also found their way into Merkel, Racycle, Reading Standard, and many other makes, each of which contributed to Indian's (and Aurora's) profits.

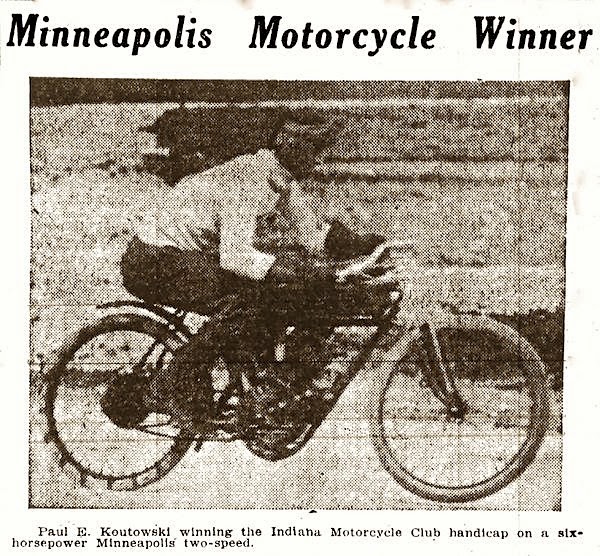

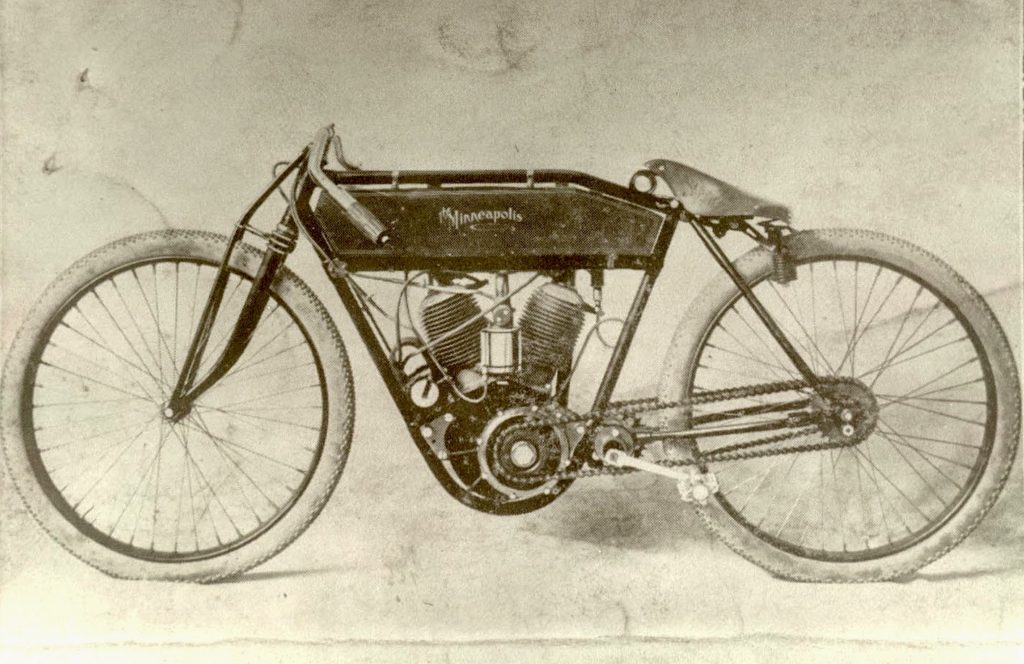

As racing was always the best advertisement, the Michaelson brothers threw their hat into the ring by 1909, participating in various local hillclimbs and track races with single and twin-cylinder Minneapolis racers, both types using the distinctive F-head Thor engines. They won a 5-mile handicap at the very first race at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, on August 15, 1909, one of four motorcycle events that day...although it took another 100 years for motorcycles to return.

Paul Koutowski won that Indy race on a Minneapolis v-twin with Thor engine, which used a two-speed rear hub - a truly historic occasion, although motorcycle racing at Indy is largely forgotten today: the motorcycle races preceded automobile racing on the track by a year, and the rough original surface led to two crashes in the two-wheel race (one of whom was Jake DeRosier), and two fatalities in the first car race. The surface was repaved with bricks in 1911, and the 'Brickyard' was born...with no more bikes until 2009, when world champ Nicky Hayden pottered around on a vintage Indian.

By 1910 Thor had a totally new v-twin engine of more modern design, and their racing development was overseen by William 'Bill' Ottoway, who would lead them to some success...enough anyway for Harley-Davidson to hire Ottoway away from Thor around 1913, to head their new racing department, which debuted under his direction in 1914.

The photographs of Joe Michaelson racing a single and twin-cylinder Minneapolis, in what appears to be a factory racing team in 1910, are from Ky Michaelson's website, but documentation on this period of Minneapolis racing is scarce. It seems they were successful and won the Riverside Hillclimb, of which the Minneapolis Motorcycle Club (the town or the factory?) was a sponsor. R.S. Porter was the winner on a twin-cylinder, Thor-engined Minneapolis.

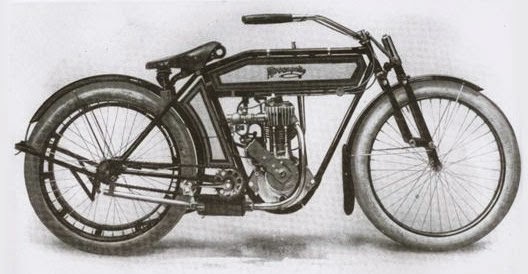

By 1911, the Michaelson brothers had designed their own sidevalve engine, among the first in the motorcycle industry, which relied on the 'F-Head' design almost exclusively since Comte DeDion first designed his almost universally adopted motor back in 1889 (licensed to over 150 moto-cycle factories!). The Minneapolis engine was big for a single-cylinder, at 36cu” (590cc), with a bore of 3.5” and stroke of 3.75”, and sold for $265.

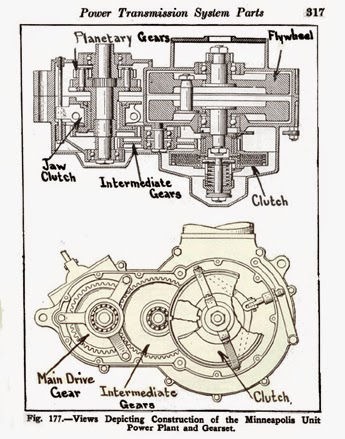

This new Minneapolis was the first American motorcycle to feature a two-speed countershaft (or layshaft) gearbox, and debuted at the Chicago Automobile Show on Feb. 6, 1909. Their two-speed transmission was housed within a unit-construction engine case, which was also a first in the US. The timing chest was one the ‘wrong’ side of the engine, and with valves on the left, the Minneapolis went counter to every other American manufacturer. This seems to be more a matter of brand identity than necessity, as the geared primary drive had an idler gear, meaning the engine and gearbox ran the same direction - unlike the later Indian Scout, which had a two-gear primary drive, and the engine ran 'backwards'.

The combined engine/gearbox was a very compact unit, with a gear-driven magneto and all-chain drive. The front forks were a novel leading-link design, very similar to the FN/Sager fork, but a little more robust in construction - later machines all seem to have leaf-sprung forks though. The Minneapolis was designed as a unique machine bristling with advanced features, some of which were not adopted by other American manufacturers until the 1950s!

The range of 1912 Minneapolis motorcycles were called the ‘Big 5’, and the single was rated by the factory at 11.5hp, who promised the bike was ‘reliable – quick – efficient’.

1912 – Then Bettered them for 1913. We set the pace for ourselves! All that we learned, all that past experience had taught us, all that we could glean from riders and the best authorities everywhere, were incorporated into the new 1913 Minneapolis. The new models are not “makeovers”. Nor are they “leftovers”. We simply made our former sturdy models better than ever. If you knew the 1912 Minneapolis you will be more surprised with our newest models. We have ample facilities, plenty of capital and a competent enough organization to fully guarantee the Minneapolis. As to gracefulness of outline and sturdiness of build, the Minneapolis is all the most exacting buyer could demand. But please look below the surface. Let us tell you a few things we have done and some of the departures we stand for. We were among the first to appreciate the advantages offered by a variable speed drive and for the past four years have steadily adhered to this feature. The standard equipment is 28" wheel, but in lieu of the 2.5" tire formally used, the 1913 standard is 2.75”. The latest type of knock-out front axle and Thor brakes have been adopted…"

Beginning in 1912, to ‘satisfy all demands’, the Michaelson brothers added a v-twin to their range, with the well-known Spacke F-head. The Spacke motor was special for the Minneapolis, as the right-side crankcase half incorporated the gear drive for the Minneapolis primary case, and their 2-speed gearbox was bolted directly onto the rear of the crankcase. Thus, the Spacke engine was placed ‘backwards’ relative to the many other makes using this motor (Sears, Dayton, DeLuxe, etc), but the magneto shaft drive still faced ‘forwards’, as this crankcase casting was a mirror of that used on the Sears and Dayton. Curiously, the ‘Eagle’ motorcycle used a Spacke engine with this same magneto configuration, but with the engine placed in the ‘normal’ direction, so the mag was behind the motor. Perhaps after Spacke made the ‘custom’ crankcases for Minneapolis, they were able to sell a few to Eagle, and occasion to be at least a little different from Sears and Dayton?

By the time the US entered WW1 (late 1914), any American motorcycle manufacturer which hadn't jumped the bandwagon for military contracts found themselves struggling with rapidly escalating labor and materials costs - inflation caused by the a massive US gov't injection of cash into the economy for the war effort. As a result, dozens of US motorcycle makers went out of business during WW1, and the range of motorcycles available shrank to just a handful post-1918, which was further knocked by a sudden availability of cheap war surplus motorcycles. The Michaelson brothers sold the company in April 1914 to the Wilcox Motor Co., with new president Lee W. Oldfield, an automobile racing driver, but it doesn't appear to have lasted much later than 1914, despite a $50,000 injection of capital from I.A. Webb, of Deadwood, SD.

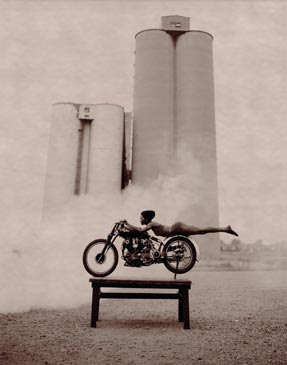

Bill Phelps

I've been awe-struck by Bill Phelps' photography for years - he evokes something mysterious from motorcycles, and his technique is flawless. He seems to be always telling a story, but there are never enough clues to explain the tale, so the images exist as a fleeting moment in a larger, unknown narrative. He's said of his work, 'If I am truly taken with an idea I'll do whatever it takes to make it come to life.'

Some of the more unusual ideas must have taken some doing! Not all of his work is based around motorcycles; he does incredible portraiture as well, and other genres.

Mark Mederski, curator of the National Motorcycle Museum in Amarosa, Iowa, forwarded the link to Phelps' gallery in New York, in case you'd like an original. I would! Check out his work at the Robin Rice Gallery.

Days of Future Past: the Mercury

There wasn't an announcement when the Future died, but die it did, sometime around the 1980s I reckon, as the Age of Optimism was superseded by the Age of Irony. For over 100 years the Future was a popular pastime, the subject of countless magazine articles, fantastic illustrations, and sometimes wacky/sometimes dead accurate conjecture on what our material surroundings would look like, and how they would function, in the Future. As we've passed the Millenium, and are still driving piston-engine cars and telefork motorcycles, it seems our imminent whiz-bang Future hasn't arrived yet, and isn't likely to arrive soon; hell, we don't even have a space program anymore. Our enthusiasm for the Future seems to have died when the bills - financial, societal, environmental- came due.

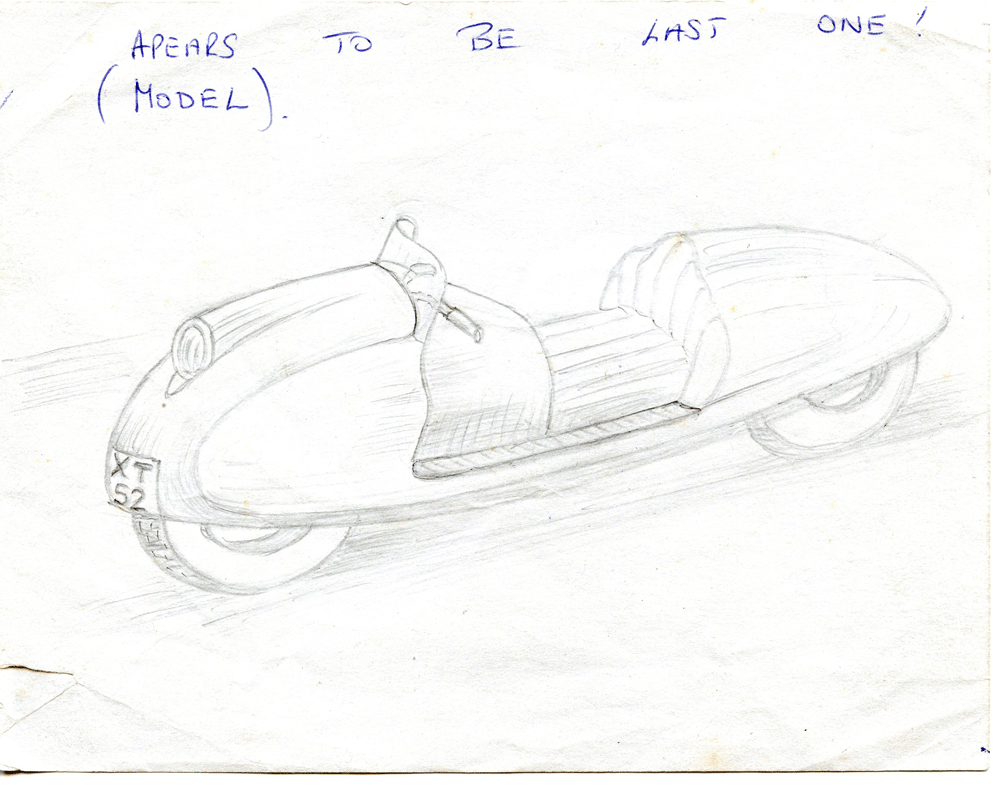

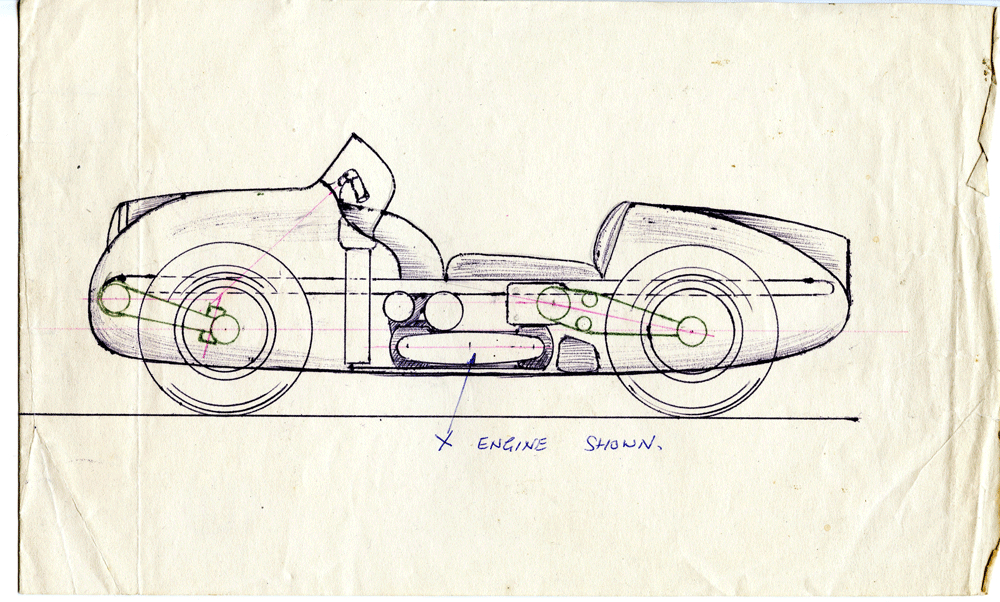

Dedicated Future-hunters in the motorcycle world smile ruefully at regular columns and drawings published in magazines from the 1920s through the 50s, in which visionary readers and schoolchildren sent sketches of their 'ideal' motorcycle (Four cylinders! Suspension!), while a few hardier and more determined souls actually set about building their dreams. It is to them we must truly tip our hat, and, without irony, give thanks, for they are the actual creators of the technologies we take for granted today. Yes, four cylinder, and yes, suspension, and disc brakes, and center-hub steering, and all-aluminum everything. Which brings us to the Mercury.

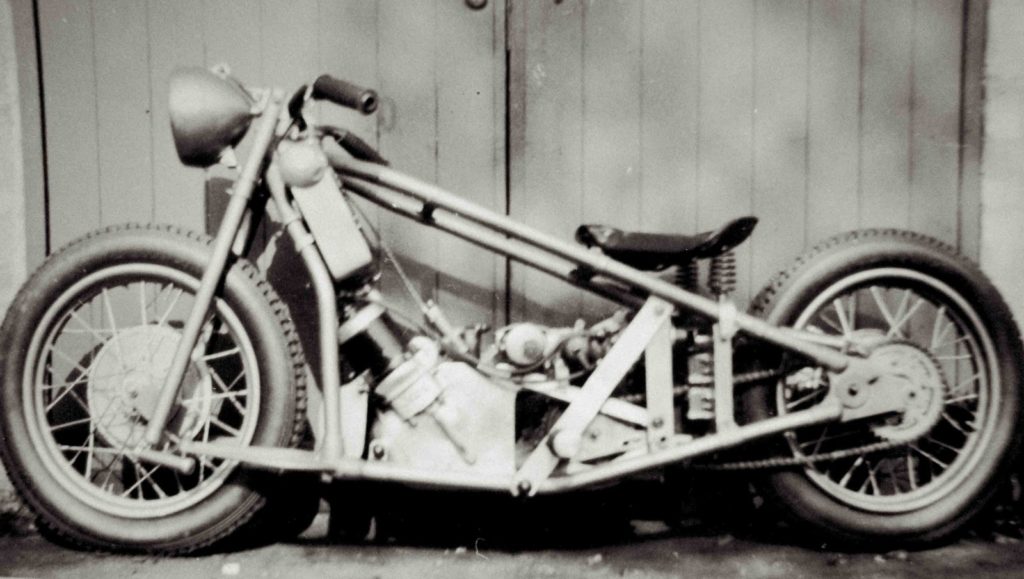

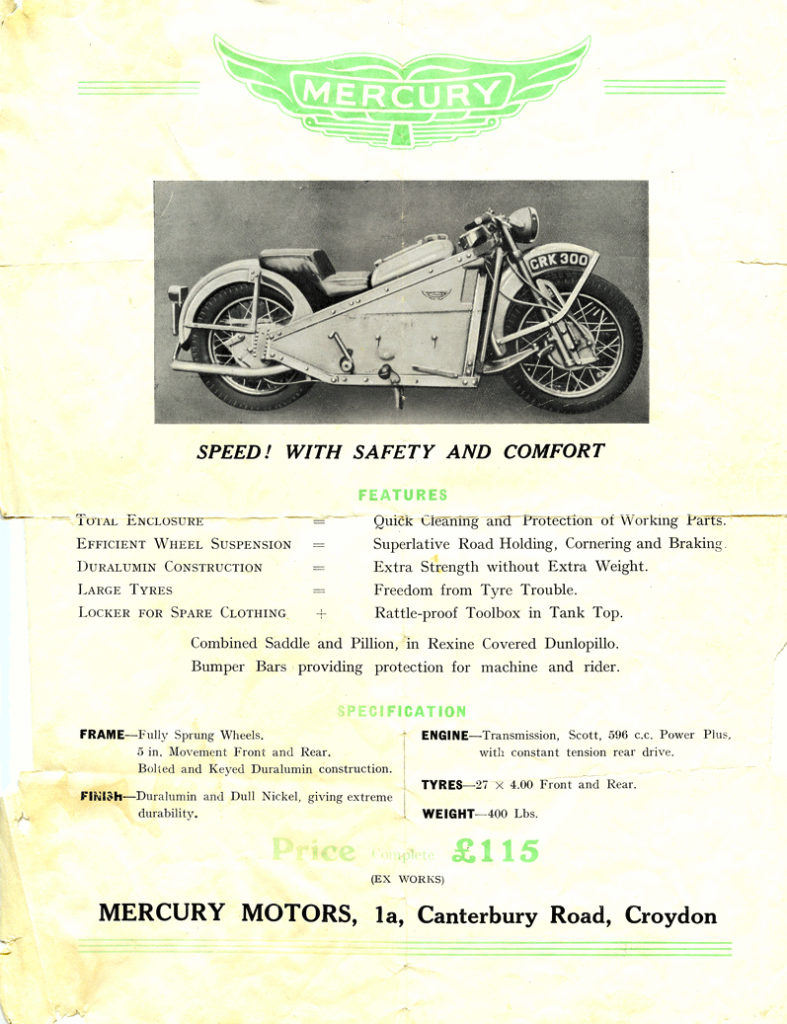

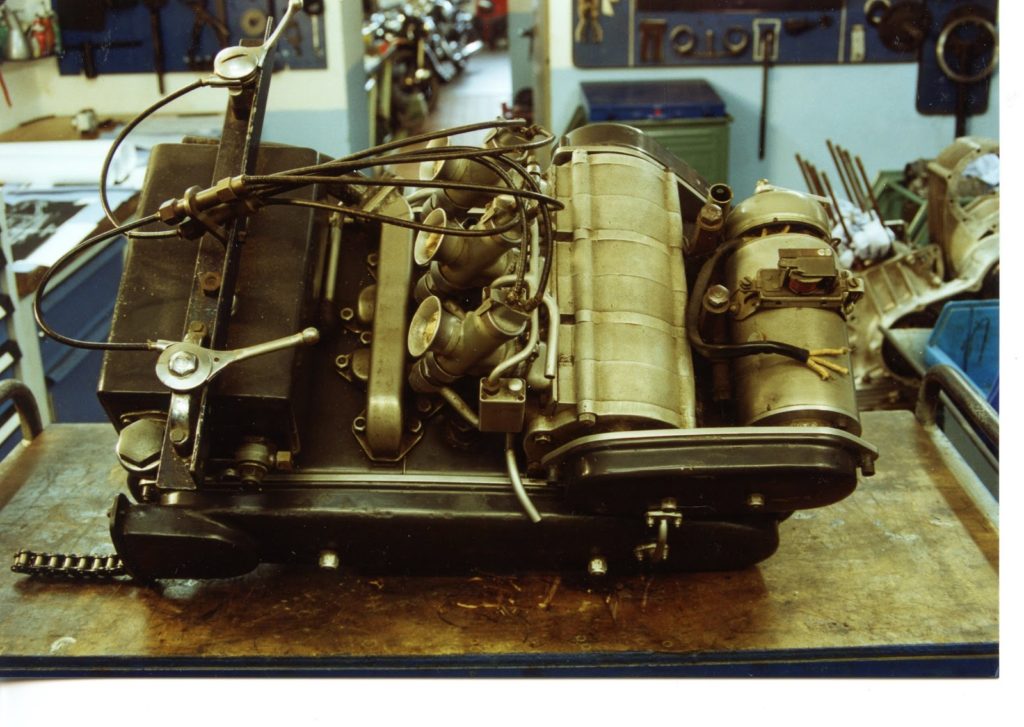

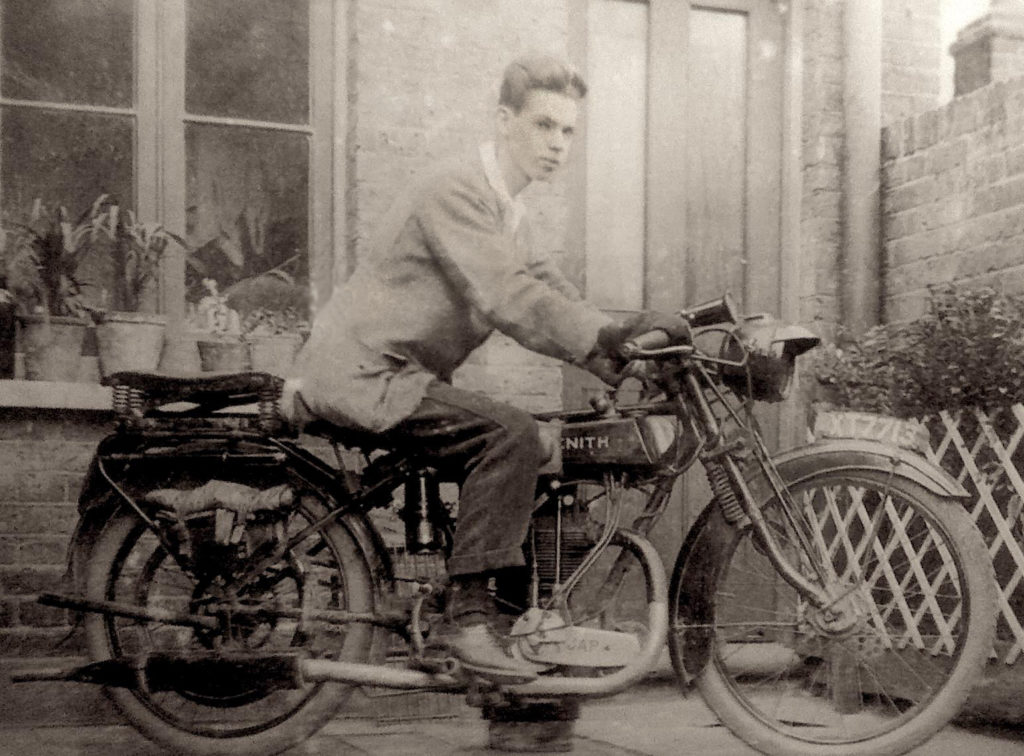

The product of four backyard visionaries, the Mercury project was especially the vision of one man, Laurie Jenks, who had toured extensively on the typical girder-forked, rigid-framed motorcycles of the late 1920s, and decided the time was ripe for a more sophisticated touring motorcycle. His first prototype, built in 1933, featured a tubular frame, with articulated rear suspension and a version of 'duplex' steering up front, similar to the OEC system, a cousin of hub-center steering, which we know had been around since the earliest days of motorcycling (Ner-A-Car of the 20s, and before that, the Zenith Bi-Car of the 'Noughts), the principal advantages being lack of deflection under side loads, and greater stability over rough surfaces/hard use, and zero tendency for 'speed wobbles'.

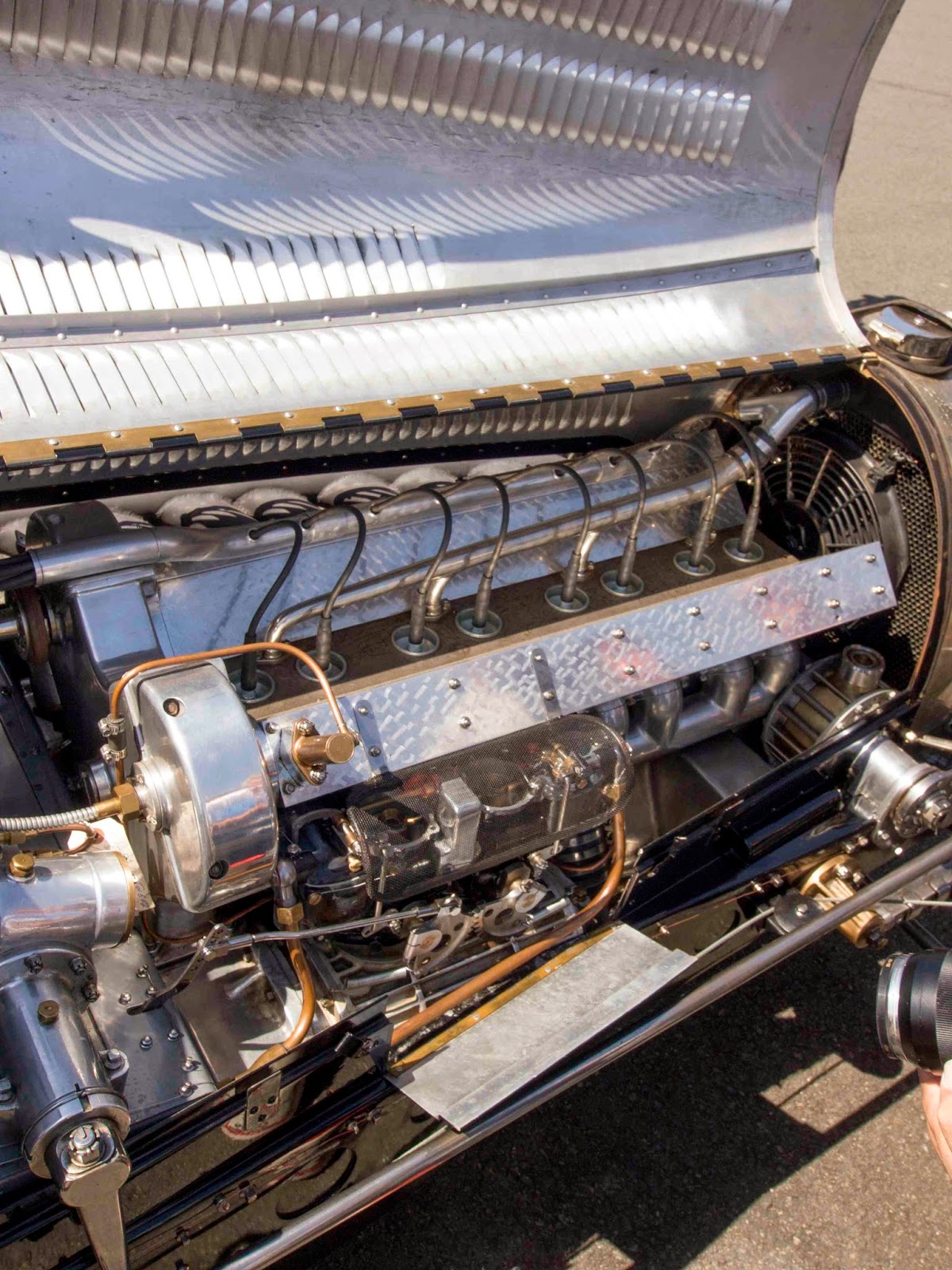

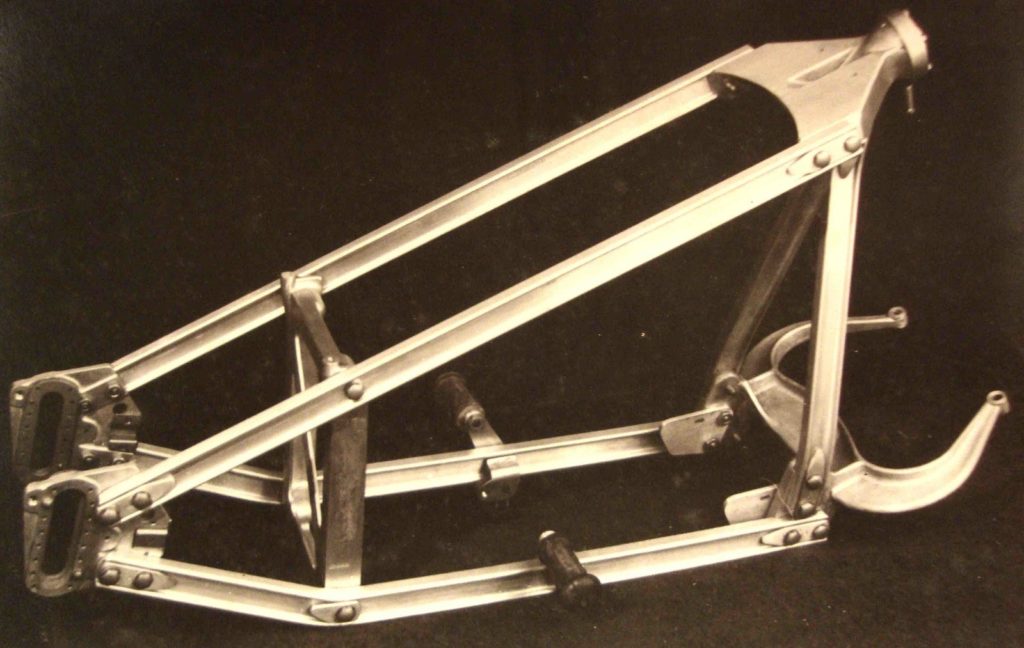

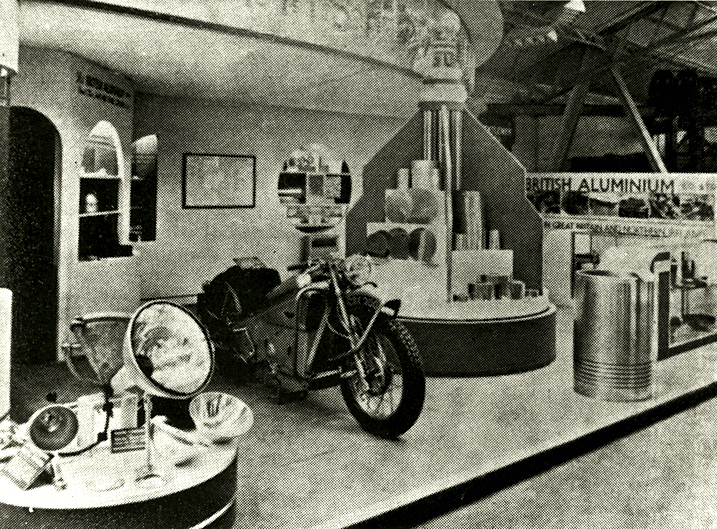

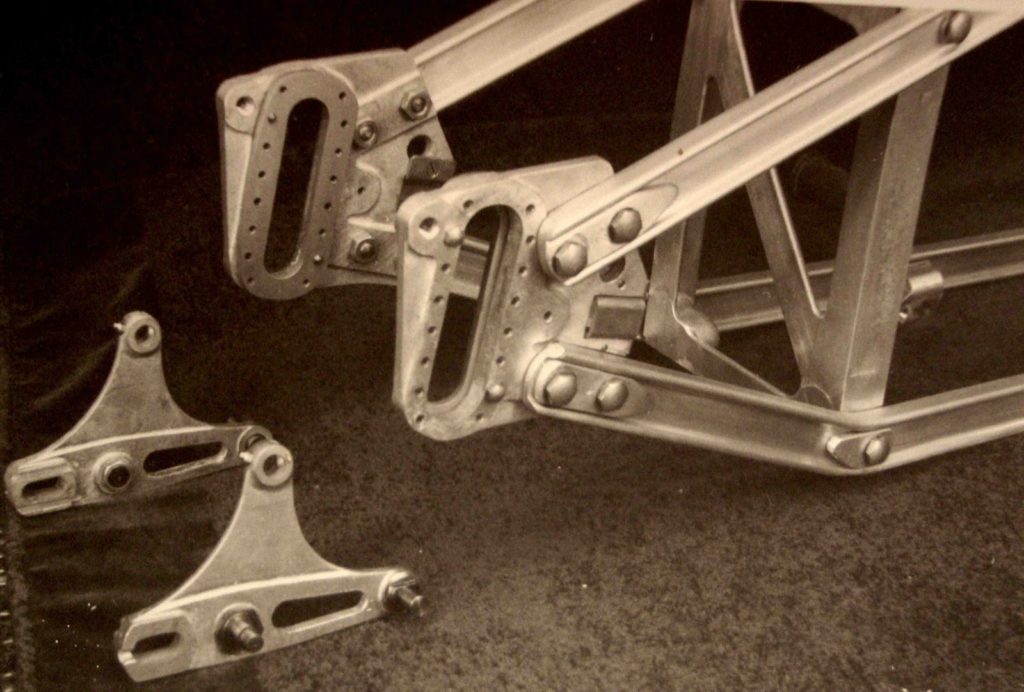

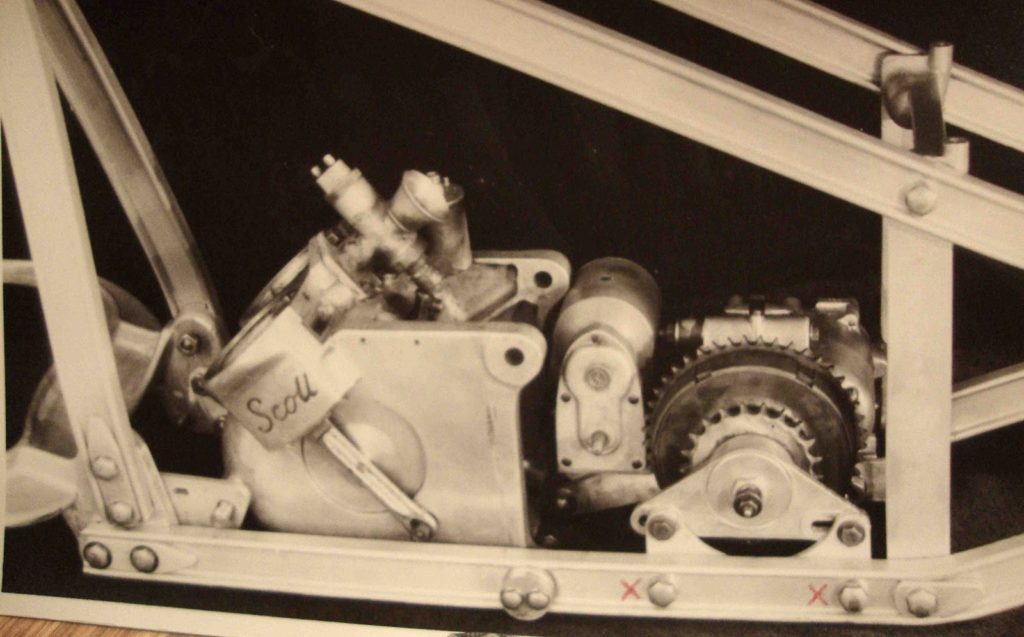

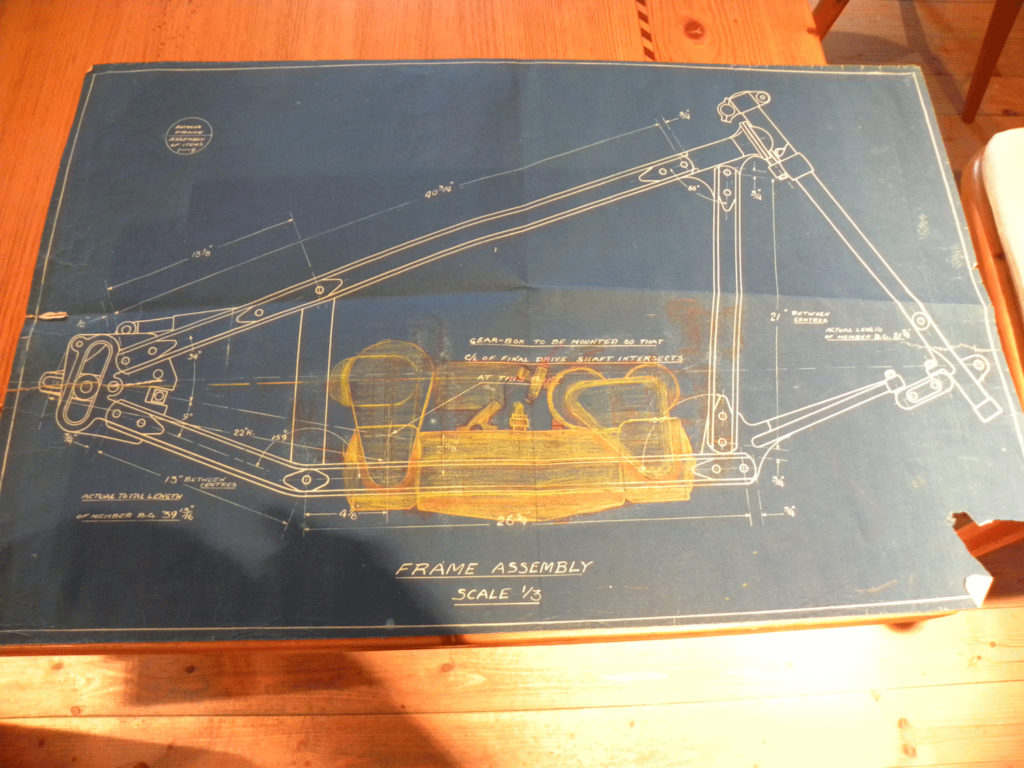

When the tube frame prototype of 1933 proved satisfactory, Jenks' 'Ideal' motorcycle went a step further, with an all-riveted aluminum chassis and alloy bodywork covering his advanced steering and suspension ideas. It took another four years to begin 'production' of the Mercury, after ordering aluminum castings for the steering head and other lugs, plus extruded I-section aluminum for the main frame spars; enough frame parts were ordered for an initial batch of of 4 machines. The shape and material of the Mercury chassis is top-shelf 1930s practice, echoed by the most advanced GP machine of the era, with which it shares many features; the Gilera 'Rondine' also had an ultra-strong twin-spar chassis, and extensive use of aluminum, and water cooling...but the similarities end there, as the Rondine's DOHC supercharged inline 4 was truly the Future, whereas the Mercury's tuned Scott 600cc two-stroke twin-cylinder engine was merely the Present.

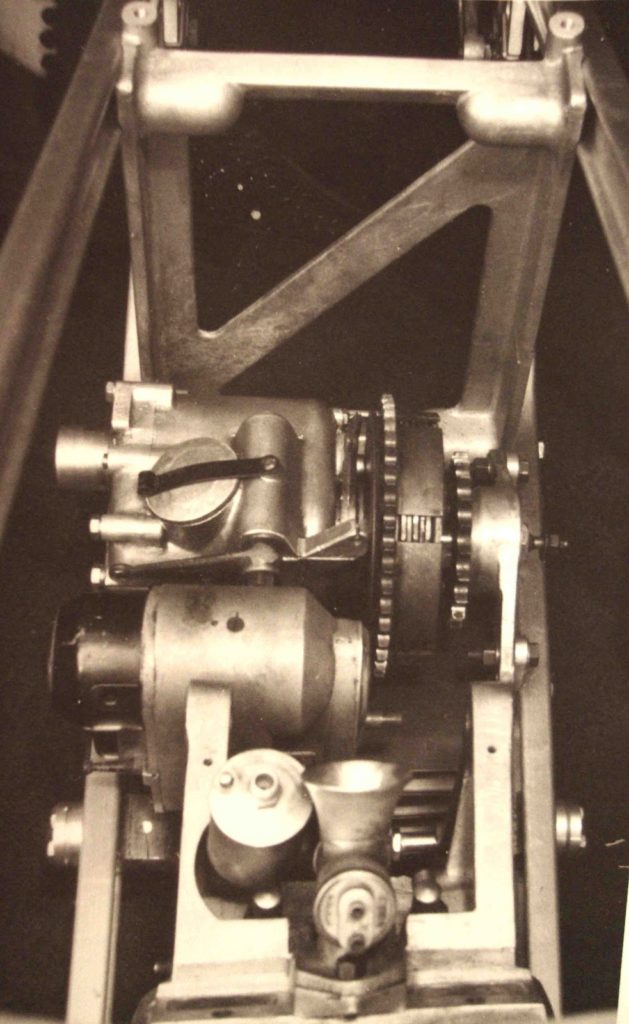

In truth, with limited funds available to buy a new engine (let alone develop a motor of their own), Jenks and his partner Mr. Swabey, who ran a garage tuning Scott engines, relied on the Past for their Mercury motors, and used reconditioned and tuned Scott engines from as far back as 1933 in their futuristic machine.

While Scott was the only 'sporting' and TT-winning motorcycle to never win a Brooklands 'Gold Star' (for a 100mph lap during a race), the Scott engine had its appeal, being very smooth, simple, reliable, and easy to maintain, while possessing devilishly quick acceleration, if not the 100mph top speed required of a truly Hot bike. When press-tested in 1937 for Motor Cycle, the completed Mercury was ridden hands-off around the incredibly bumpy Brooklands track at an average of 70mph, while 90mph was the estimated top whack. When introduced to the world in 1937 as the product of 'Mercury Motors', the price was listed at £115 - the same as a Brough Superior '11-50' model with 1100cc JAP engine (see the full Brough price list here, on the excellent B-S company archives). Those first four aluminum chassis were the only Mercuries built; we love the Future, until we must pay for it.

The Mercury was stable enough for Brooklands, and fast enough at 90mph, even if not a racer; what else was it? Meant for touring, clearly, with a lot of elegant details with the rider's comfort in mind, like the large tool/glovebox in the tank top, which also housed an oil reservoir for a chain oiler. The instrument panel included a fuel gauge, and various pull-knobs for electrical controls. Both front and rear suspension consisted of undamped compression and rebound springs, which Jenks felt kept the wheels in more contact with tarmac over undulations. Large section tires (4"x19" - huge for the day) gave comfortable if slow steering, and all that aluminum protected the rider from oil and mud. While the chassis and bodywork were aluminum, the deep mudguards were nickel-plated steel, giving an overall super-silver look, akin to the sleekest aircraft of the day, all rivets and shiny panels, the very picture of the Future, Buck Rogers on two wheels.

Laurie Jenks wasn't the first, nor the last to build an 'ideal' motorcycle, and his Mercury was better than most in looks and real-world performance. While not to everyone's taste, I find the Mercury visually exciting, and 1930s-futuristic like almost no other vehicle on two or four wheels - closer to advanced aircraft practice. Jenks' fundamental ideas - a comfortable and civilized sporting motorcycle which protected the rider from the elements- were completely sound, and an accurate vision for the Future. A funny thing about the Future, though; when it actually arrives, it immediately becomes the Ordinary. Motorcycle manufacturers have been burned many times by introducing radical new ideas (full enclosure, Wankel engines, hub-center steering) to a non-buying public, but the idea of a sophisticated, smooth, fully enclosed sport-touring motorcycle finally came to fruition in the 1990s, embodied by machines like the Honda Pacific Coast, and later, the fully-enclosed Gold Wing and its cousins. All very efficient and rider-friendly, yet somehow, incorporating good ideas from design Futures seems to leave the 'Wow' factor in the Past...

Many thanks to Norman Gunderson of Canada for the beautiful b/w detail photos of the Mercury; Norman found reference to the Mercury in my coverage of the Concorso di Villa d'Este earlier this year, and was a personal friend of Laurie Jenks, from whom the photos originated. Also thanks to the Hockenheim Museum in Germany, for sending the rest of the photos; four Mercuries survive, plus the tube frame prototype (a chassis only at this point - 2012), and all are at Hockenheim; if you haven't seen this collection, you owe it to yourself to make a trip.

Brooklands

Its a place I never tire of visiting, not caring whether nostalgia or ghosts lure me to the crumbling, mossy banks of this nearly vanished track. Brooklands, the original speed bowl, whose gates were flung wide in 1907 for a parade of touring cars, nearly motorized carriages that day, all billowing ash-stiffened canvas tops and wood spoke wheels, playthings of the rich, curiosities, slow and troublesome, marvelous.

Within 100 yards that opening day procession broke out in a race, the first of a thousand to come, the gleam in the eye of those Edwardians who rotated throttle levers wide and set to passing the car before, ladies and children aboard, forgetting everything, bunting and flowers trailing behind, irrelevant.

None could 'win', but someone hit the clubhouse first, no doubt to drinks and merriment, revved up on speed juice. Things grew seriouser and seriouser with time, the gentleman's club suddenly central to Industry - planes, cars, motorcycles, the military, national prestige, progress.

None could 'win', but someone hit the clubhouse first, no doubt to drinks and merriment, revved up on speed juice. Things grew seriouser and seriouser with time, the gentleman's club suddenly central to Industry - planes, cars, motorcycles, the military, national prestige, progress.

The absolute speedmen were gone by the Twenties, needing far more stretch for their legs, but they weren't Racing, except against Time, doing battle against a common foe, the mortal enemy of us all.

Motorcyclists raced time too, by increments, in clocks, staking claims a little further along the miles - per hour, per day - or against their fellows. They raced for trinkets, enameled copper stars, spark plugs and tires, dotted grainy photos in the press, and a little money to keep going, to be in it. To a man, that was the key, the same gleam bound them, not mercenaries, true amateurs, for the love of the sport, the love of a place. Brooklands.

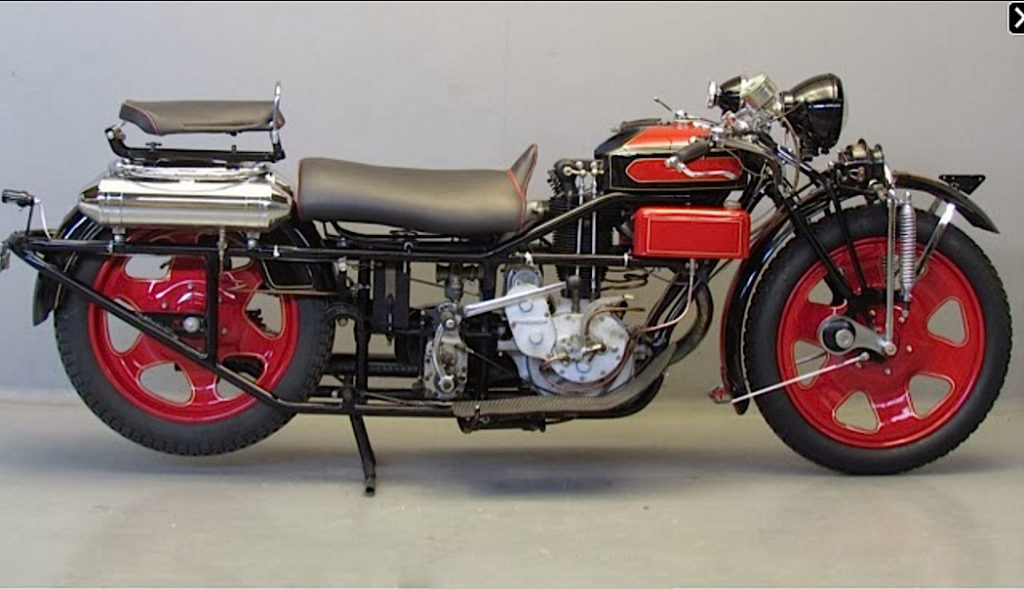

1935 Böhmerland 'Reise'

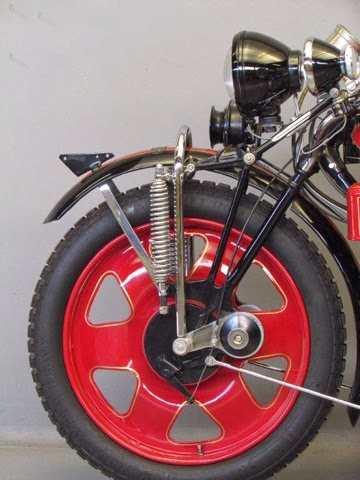

In the 1920s, the Czech motorcycle industry pushed the technological forefront of engine and chassis design, producing the first series built double-overhead camshaft design (the Praga), as well as the longest production motorcycle in history, the Böhmerland. The brainchild of Czech engineer Albin Leibisch, the Böhmerland was built between 1925-1939 in Schönlinde, Sudetenland, and was almost entirely the result of Leibisch’s design and manufacture. That remarkable chassis of welded tubing, the unusual leading-link front forks, the engine, and the cast wheels (a pioneering use for motorcycles, not generally taken up until the 1970s!) were all made in-house, with only the gearbox and various ancillary parts bought-in (magnetos, carburetors, controls, etc). The small factory at one point employed 20 assembly workers, with parts supplied by local subcontractors; production eventually totaled around 3000 units.

The most visually distinctive feature of the Böhmerland was its great length, although several models were produced, from the shortest-wheelbase racing model with a claimed 96mph (160kmh) top speed, to a single-seater ‘Sport’ version, a 3-seater ‘Touring’ model (the most popular, and seen here; seating designation includes the pillion at rear), the extravagant 4-seater ‘Langtouren’ (Long Touring), and even an experimental military model with 4 seats and two gearboxes (the rear ‘box operated by a passenger), giving 9 possible ratios! With a sidecar attached, a Touring Böhmerland could safely carry 4 or 5 passengers, with more elegance and speed than nearly any contemporary automobile of the 1920s. Early models used twin petrol tanks, which kept the cylinder head visible and accessible to the rider/mechanic; later models used a more conventional ‘saddle’ tank (as seen here) which covered the top frame rails. Some later models also used cast steel wheels, as aluminum casting technology lagged behind the far-sighted ideas of Albin Leibisch!

Specifications of the ‘Touring’ Model seen here are a total length of 124” (317cm), with a wheelbase of 88” (223cm). The Leibisch engine is a sturdy overhead valve, dry-sump unit of 600cc (80x120mm bore/stroke), producing 24hp @5000rpm, with a top speed of 65mph (110kmh), giving a frugal 70mpg in normal use.