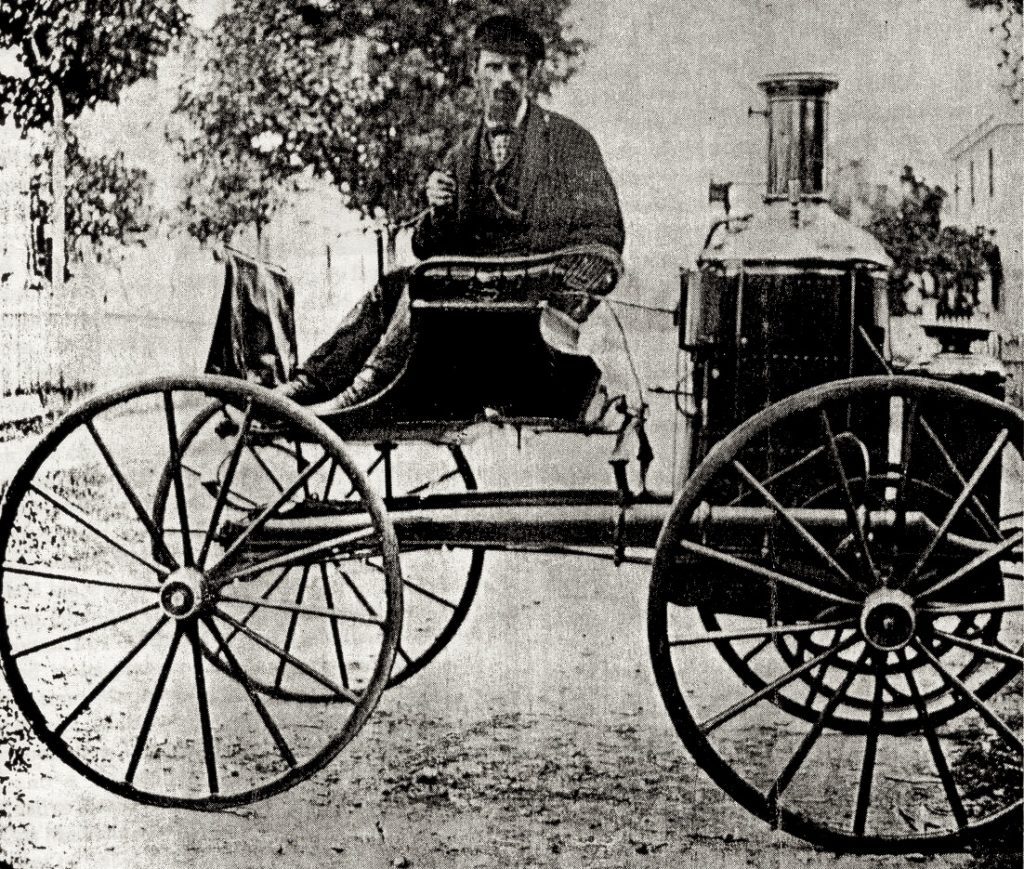

Sylvester Roper, born in Francestown, New Hampshire in 1823, was a singularly brilliant individual, patenting sewing machines, machine tools, furnaces, shotguns, fire escapes, as well as building his steam-powered two, three, and four-wheelers, which he did not patent. His Steam Velocipede was created a few years after building his first Steam Carriage (ie, automobile) in 1863, in the midst of America’s Civil War, while he was stationed at the Springfield Armory. His first Velocipede of 1867/8 used a very small steam engine, which Roper built himself. The engine was suspended from a forged iron frame -purpose-built for the machine- on spring steel strips, which absorbed many of the road shocks typical of the ‘boneshaker’ bicycle chassis. The front fork was also iron, and wheels were wooden with steel ‘tires’, 34″ in diameter. Water for the engine’s boiler was carried inside the rider’s saddle! The engine had two pistons of 164cc capacity, each connected by a crank-arm and rod to the rear wheel. The total engine capacity was 328cc.

The rider controlled the Velocipede by rotating the handlebars forward – and thus the twistgrip throttle was born, decades before Glenn Curtiss claimed the same with his first motorcycles, which was again before Indian received general credit for this excellent idea! To stop the Roper, the rider rotated the handlebars backward, which pressed a steel ‘spoon’ onto the front wheel. Water was automatically fed from the seat to the boiler via a water pump actuated by engine rotation. The small firebox at the bottom of the motor was fed with charcoal, and a pressure gauge mounted on the steering-head kept the rider apprised of power, and danger.

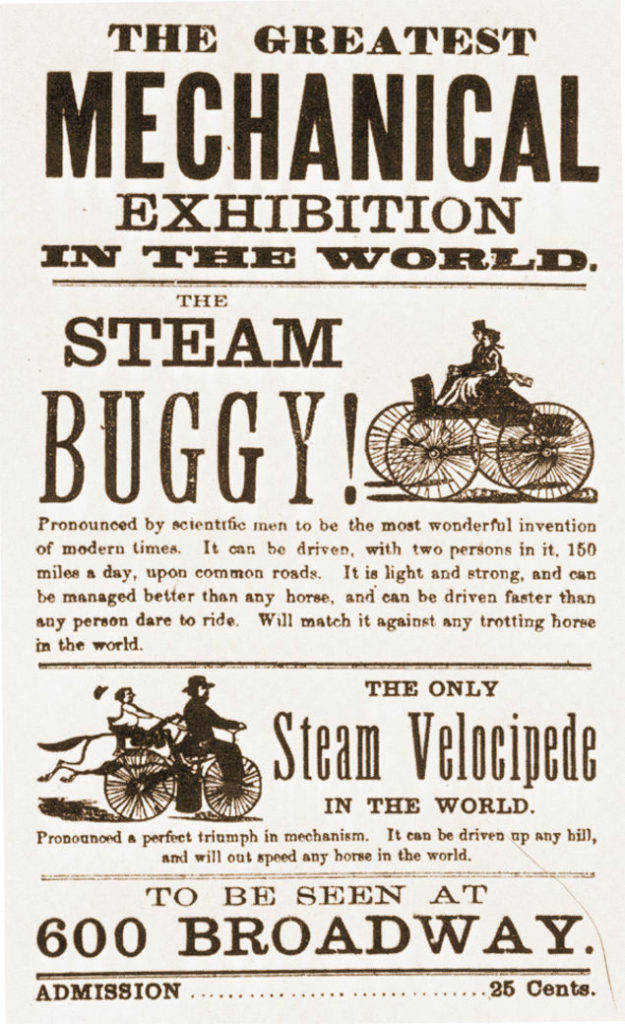

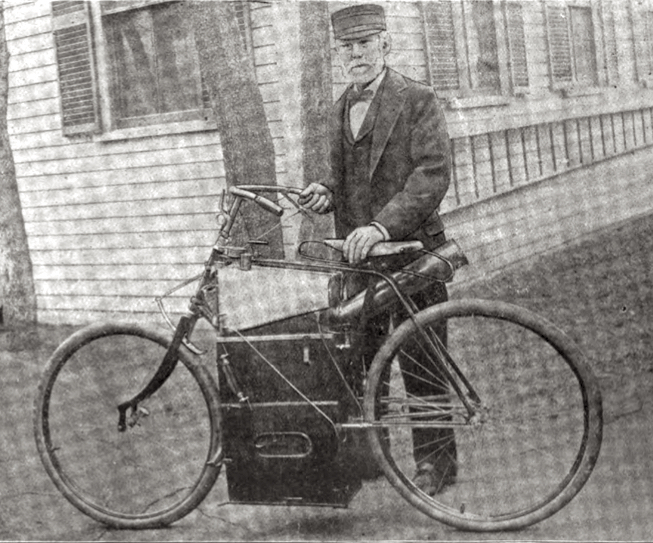

The contraption worked, although perhaps not as well as his Steam Carriages, which had space for much larger engines, and carrying capacity for water and fuel, which meant a longer travel range. The harsh ride of the wooden wheels with steel tires must have become tiresome as well, in contrast to his four-wheelers which used buggy springs for rider comfort…Roper postponed work on his Velocipedes for 15 years. In the intervening years, bicycle design had undergone a sea change, as in 1880, the Rover Safety Bicycle was invented, and rubber tires came into general use. These improvements must have spurred Roper to take up two wheels again in 1894, when Albert Augustus Pope commissioned Roper to make a new Steam Velocipede using a modified version of Pope’s popular ‘Columbia’ safety-bicycle frame, with pneumatic ‘Dunlop’ tires. The intention of Pope (who by 1911 manufactured his own motorcycles) was to use the machine as a cycle-pacer on the incredibly popular bicycle racing velodromes of the day.

Roper designed a new steam unit weighing about 125lbs, making an all-up weight of the machine 150lbs. The bump absorption capacity of air-filled tires made it possible to solidly mount the engine to the frame, in the ‘right’ location, with the weight low and centrally between the wheels. A single cylinder and piston of 160cc drove the bicycle via a long connecting rod, and a short crank at the rear wheel. Steam pressure was kept between 160 and 225psi (for hills), although the engine was tested to 450psi. The machine was good for at least 40mph, and carried enough coal for a 7-mile trip. The new machine was compact, light, and very fast, and Roper, pleased with his results, put in quite a few miles on his steamer, regularly riding a round-trip of 7 miles between his home in Roxbury to the Boston Yacht Club. American Machinist magazine noted, “the exhaust from the stack was entirely invisible so far as steam was concerned; a slight noise was perceptible, but not to any disagreeable extent.”

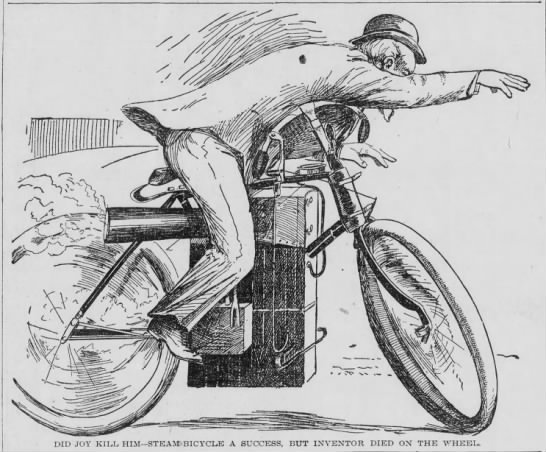

Roper was happy to demonstrate his steam vehicles to the public, at fairs and exhibitions, and claimed his latest Velocipede, or ‘Self Propeller’ as he called it, could “climb any hill and outrun any horse.” On June 1st, 1896, he rode to the Charles River Speedway in Cambridge, to show the local bicycle racers his new cycle-pacer. Several cyclists agreed to keep pace with him on the banked 1/3 mile cement track. The Boston Globe reported on June 2, 1896: “The trained racing men could not keep up with him and he made the mile in two minutes, one and two-fifths seconds. After crossing the line, Mr.Roper was apparently so elated that he proposed making even better time and continued to scorch around the track. The machine was cutting out a lively pace on the back stretch when the men seated near the training quarters noticed the bicycle was unsteady. The forward wheel wobbled badly…”, and it seems track-side viewers rushed out to catch the slowing rider, who had died of a massive heart attack while riding, at age 73. As Roper controlled the throttle with a cord around his thumb, steam power shut down as he relaxed into the arms eternal night, having proved himself motorcycling’s Speed Merchant, and its first martyr.

Related Posts

July 25, 2017

The Vintagent Trailers: Morbidelli – a Story of Men and Fast Motorcycles

Discover the story of the Morbidelli…

Is it more than coincidence that this comes after Dave Roper’s ride at the isle of man? I believe Dave is a direct descendant of Sylvester, the inventor of the motorcycle. Really. There must be something in the genes, because Dave is truly one of the greats, and no better one to be leading the lap of champions.

Peter W

Hi Peter,

believe it or not, it IS a coincidence! I began researching very early motorcycles recently as I ran across the Michaux-Perreaux in Paris, and heard the Roper might come up for sale. Dave Roper contacted me to mention he is a relative of Sylvester Roper; Dave calls it a ‘wandering gene’; a charming acknowledgement of distant relation.

The coincidences built like waves; I had just written an article for the Quail Motorcycle Gathering about the centenary of the ‘Indian Summer’ of 1911, and Dave figures in this, too!

I’ve known Dave since the 1980s, when I was editor of the Velocette Owners Club newsletter (Fishtail), and he submitted writing about a mk8 KTT which he found an ideal motorcycle…

Hello:

I’m from Francestown, N. H. birthplace of Sylvester Roper and have been collecting information about Roper for the Francestown Improvement & Historical Society (FIHS). We invited David Brodeur to speak about Roper at a special meeting, he also spoke at the Lars Anderson Museum. I met Dave Roper at Motorcycle Week at Gunstock in 2003 when he was racing a rare 3-cyclinder AJS. Dave later sent me his genealogy, he is Sylvester’s 2nd cousin, 4 times removed. If you have access to Ancestry.com, you can view my Sylvester H Roper Family Tree. Our annual Francestown Labor Day Parade (2012) is “Inventions and Discoveries”. We are hoping for entries featuring the many inventions of Roper.

Priscilla Putnam Martin

Past President FIHS

P. O. Box 252

Francestown, N. H. 03043-0252

FredMikePris@comcast.net

603-547-3616

Paul, I’ve been extremely impressed by the new format Vintagent and it’s incredible amount of content. In my highly bias view, this article is the best yet, very well researched. I hadn’t known of the connection with Pope. Priscilla is correct, I’m Sylvester’s 2nd Cousin, four times removed, though that was a three valve, not cylinder, AJS that I rode at Gunstock. I think that Gary Roper, who’s Velocette MAC I have raced many times, is also proof of the Wandering Gene Theory. I look forward to the next fascinating article by you and your contributors.

Thanks Dave!

is awesome