A recent publication from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC explored the history of one of their motorcycles (yes, they have many, including Sylvester Roper’s ‘first ever motorcycle’ of 1867, and the Curtiss V-8 record-breaker of 1906, which clocked 136.3mph at Ormonde Beach, FL). Their intern Christine Miranda did a little investigating, and came up with this story – it seemed perfect for The Vintagent (and thanks to David Blasco for the nudge!).

“In museums, it’s common for a single artifact to tell many diverse stories, far beyond the scope of any one exhibition. Christine Miranda, who interned with our Program in Latino History and Culture, explores this idea when she encounters a motorcycle used in Guatemala and digs further.

Our America on the Move exhibition on the history of U.S. transportation is designed to transport you around the United States. As visitors explore all 26,000 square feet of our Hall of Transportation, they “travel across America,” entering a variety of carefully curated historical moments. One of the exhibition’s later segments, “Suburban Strip,” immerses museumgoers into the life of the “car-owning middle class” in Portland, Oregon, 1949. The display, complete with a replica road, features an array of vehicles typical of the time and place: a pickup truck, a Greyhound bus, a motor scooter, and even a genuine Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Despite the bike’s 1949 Oregon license plate, it was never actually ridden in the Pacific Northwest.

Where was it really used? The roadways and landscapes of Guatemala. What’s more, the customized motorcycle was owned for several years by the Central American country’s president, Jorge Ubico.

I discovered the object’s mysterious past while searching the item catalogues for traces of hidden Latino history at the museum. I guess you could say I hit the jackpot. Though a Guatemalan ruler’s motorcycle may seem like an odd choice for the collections at the National Museum of American History, its inclusion in fact sheds light on the global impact of U.S. transportation industries and broadens our understanding of who, what, and where “America” includes.

Jorge Ubico, a well-educated lawyer and politician from his nation’s capital city, ascended to the Guatemalan presidency in 1931. He would then stay in that post for 13 years and become the self-proclaimed “little Napoleon of the tropics.” Besides his flair for the ostentatious and suppression of political dissent, Ubico is best remembered for his aggressive pursuit of foreign investment and close economic alliance with the United States. Notably, Ubico strongly supported the U.S.-owned United Fruit Company (UFCO), the corporate giant nicknamed el pulpo (“the octopus”) for its wide-reaching influence throughout 20th century Central America.

During his regime, UFCO became the largest landowner in Guatemala and enjoyed exemption from taxes and import duties. Via the International Railways of Central America (IRCA), UFCO also owned and operated the nation’s rail network, which facilitated its own international trade. Interestingly, when visitors first enter our America on the Move exhibition, they encounter the giant steam locomotive Jupiter, ostensibly at home in Santa Cruz, California. Though the train did originate there in 1876, Jupiter actually spent the better part of its career transporting bananas along the IRCA in Guatemala!

Like Jupiter, Ubico spent many years traversing Guatemala with the help of American transportation technology. His flashy motorcycle, a 1942 Harley-Davidson Model 74 OHV (Overhead Valve) Twin, was infamous. As described by American journalist Chapin Hall in his Los Angeles Times column:

“When President Ubico, of Guatemala, starts on a tour of inspection, which he does several times a year, he doesn’t order out the guard and a special train, but hops on a motorcycle, shouts ‘c’mon boys,’ and leads a squadron of two-wheelers, each one manned by a government department head.”

Despite the almost comical image conjured by Hall’s description of Ubico aboard his blue and chrome motorcycle, his “inspections” were the mark of his harsh, militaristic rule. Ubico’s Harley-Davidson enabled him to travel to rural communities, where he personally settled local disputes and “imposed his own brand of justice,” according to the same Los Angeles Times column.

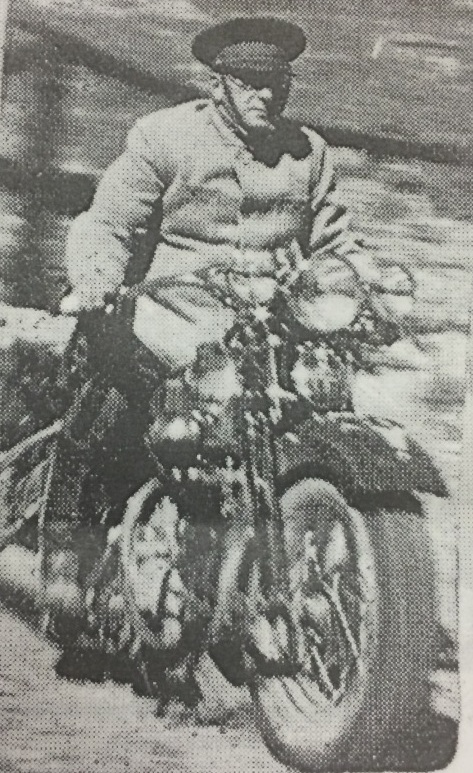

As president of Guatemala, Jorge Ubico repressed democratic practice and political dissent. His pro-U.S. economic policy worsened the plight of the middle and lower classes, while his labor laws (designed to facilitate the development of public works, like roads) utilized indigenous labor. The image of Ubico atop his motorcycle, shown here, reveals the reality of justice under his rule: “the president might appear suddenly, almost out of nowhere, on his fancy, powerful machine to render judgment”. (Quote is from “I Ask for Justice: Maya Women, Dictators, and Crime in Guatemala, 1898-1944” by David Carey.) Image courtesy of Alvaro Aparicio.

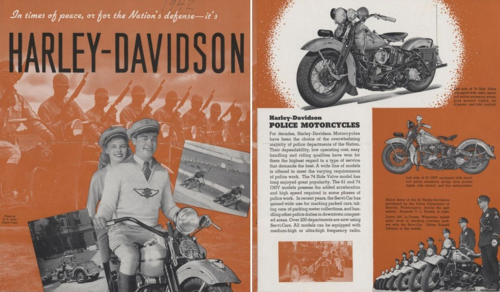

To my surprise, Ubico was far from the first to use a Harley-Davidson motorcycle for military purposes. Already used domestically by American police departments as early as 1908, Harley-Davidsons were ridden by General John J. Pershing’s men in their unsuccessful nine-month pursuit of Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. Harley-Davidson would go on to supply 20,000 military motorcycles during World War I and 80,000 during World War II. In fact, according to Paul F. Johnston, a curator here in the Division of Work and Industry, Harley-Davidson motorcycles were manufactured almost exclusively for the U.S. war effort in the 1940s, with Ubico’s bike being a rare exception.

After the war, Harley-Davidson and other American corporations enjoyed a surge in the motorcycle’s recreational popularity, with returning veterans bringing their experience and interest in riding back home with them. This is where Ubico’s bike enters the story in America on the Move. Stylized with an Oregon license plate, the motorcycle helps recreate Sandy Boulevard, a burgeoning commercial area in the suburbs of Portland during the 1940s and 50s. By bringing to life this history of midcentury suburbanization, Ubico’s motorcycle functions as a 1942 Harley-Davidson, not a symbolic set of wheels.

Since its donation in 1981, the bike has been on almost continuous display, first in the Road Transportation Hall and now, of course, in America on the Move. Chameleonic, it continues to serve various purposes. Millions of museum visitors enjoy it as a classic American artifact, oftentimes recalling their own stories and experiences with motorcycle history and culture. I look at Ubico’s bike and see that. I also see the overlapping social, military, and industrial functions of U.S. transportation, at home and abroad; the story of the man behind the motorcycle; and the multiple layers of history encapsulated by the most unexpected of museum objects. Perhaps, now you can too.

Christine Miranda was an intern in the Program in Latino History and Culture. She recently blogged about eight ways to experience Latino history at the museum.”

Related Posts

July 25, 2017

The Vintagent Trailers: Morbidelli – a Story of Men and Fast Motorcycles

Discover the story of the Morbidelli…