[A series of never-before-published photos from the National Archives]

It’s difficult to imagine today, but at the dawn of the 20th Century the United States had a tiny military, and its foreign policy was steered by the majority pacifist inclination of its people. Leaders of the ‘no war/no military’ camp included the Church (especially Protestants), the women’s movement, the large farming lobby, and scholars/left-leaning thinkers who feared the USA becoming a militarized state. World War 1 (as it became known after WW2) dramatically changed American politics, priorities, infrastructure, and economy in the ways we see today, with most Protestant sects identified with military boosterism and conservative political activism, and over half the federal budget dedicated to military spending. While the US was ‘only’ involved in the European war for 20 months, it proved the hinge that pivoted America in a totally new, militarized direction, and boosted the fortunes of motorcycle companies able to secure government contracts to supply military equipment.

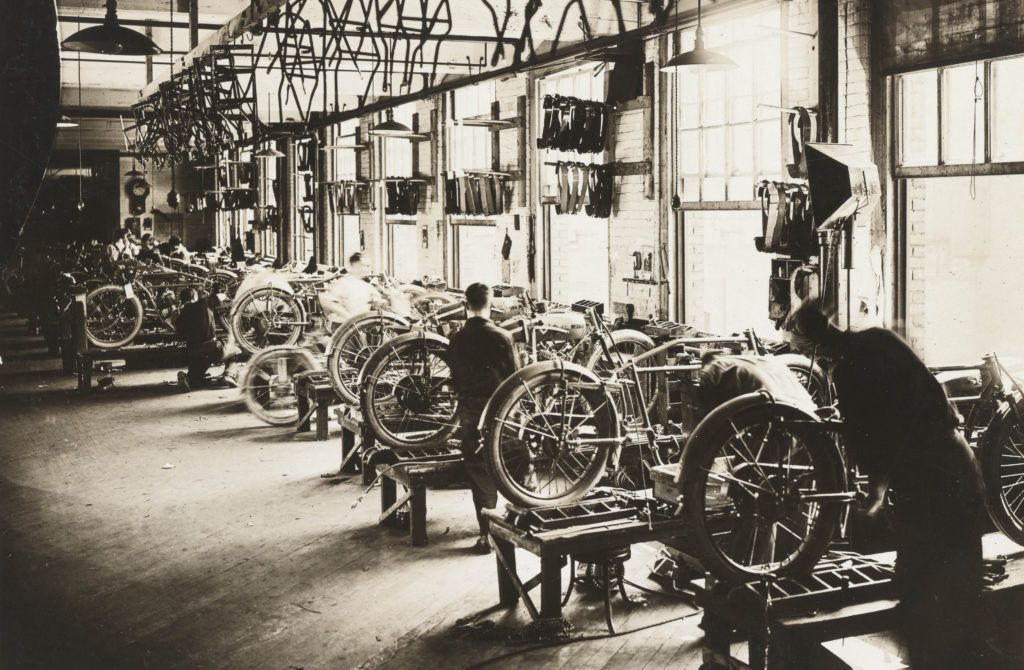

wow, very nice find. a small possible correction? – the photo of the fellow assembling the wheel – i suspect he is using the hand crank drill as a driver to spin on spoke nipples rather than making holes.

That was my first thought, and on closer inspection of the full-res photos, the holes are pre-drilled, and the spokes are being laced into the wheel, so he must be using the hand drill to tighten the spoke nipples. A clever tool!

Found this webpage doing research on what Indian motorcycle my grandfather., as a post- WWI Washington DC motorcycle cop.

Good stuff!

Paul,

Thanks for bringing these wonderfully revealing images to our attention—invaluable insights into ‘the Wigwam!’ How did you come to realize the National Archives contained the Indian, Harley, and Excelsior manufacturing photos?

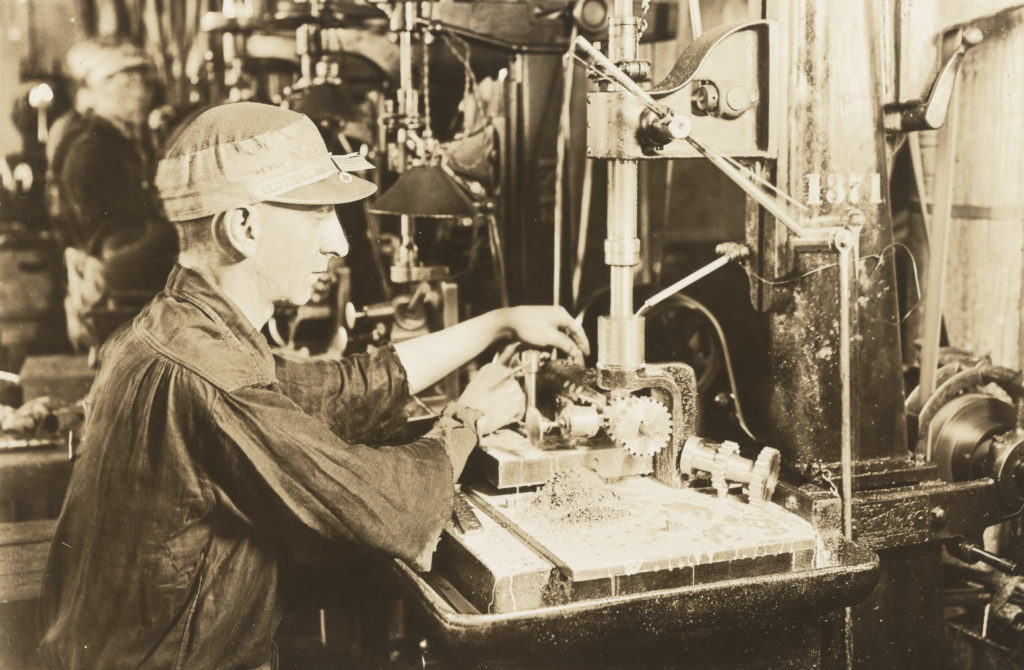

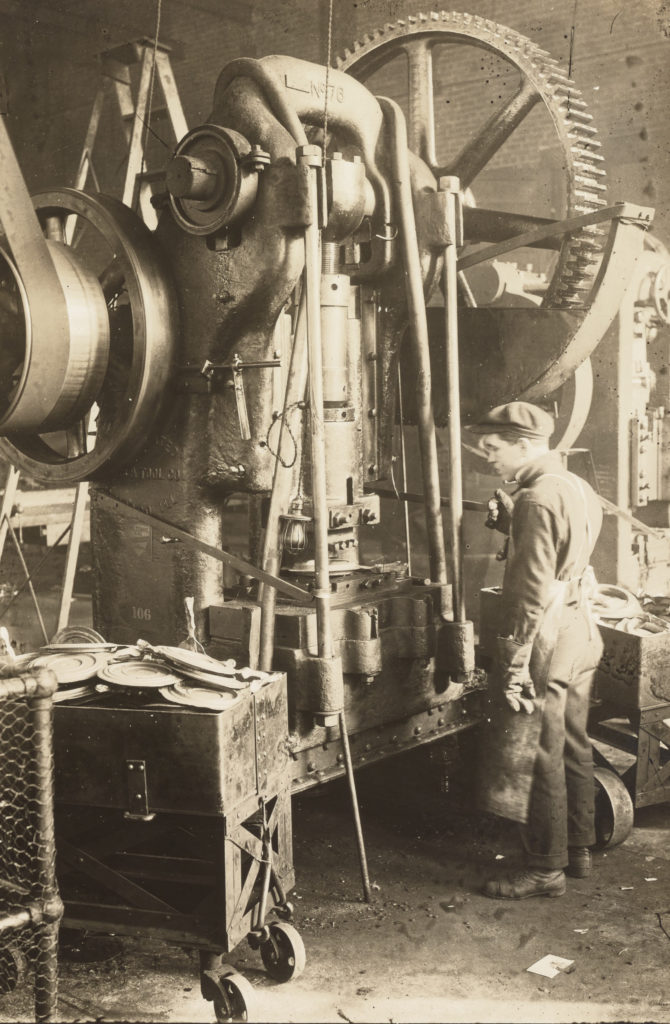

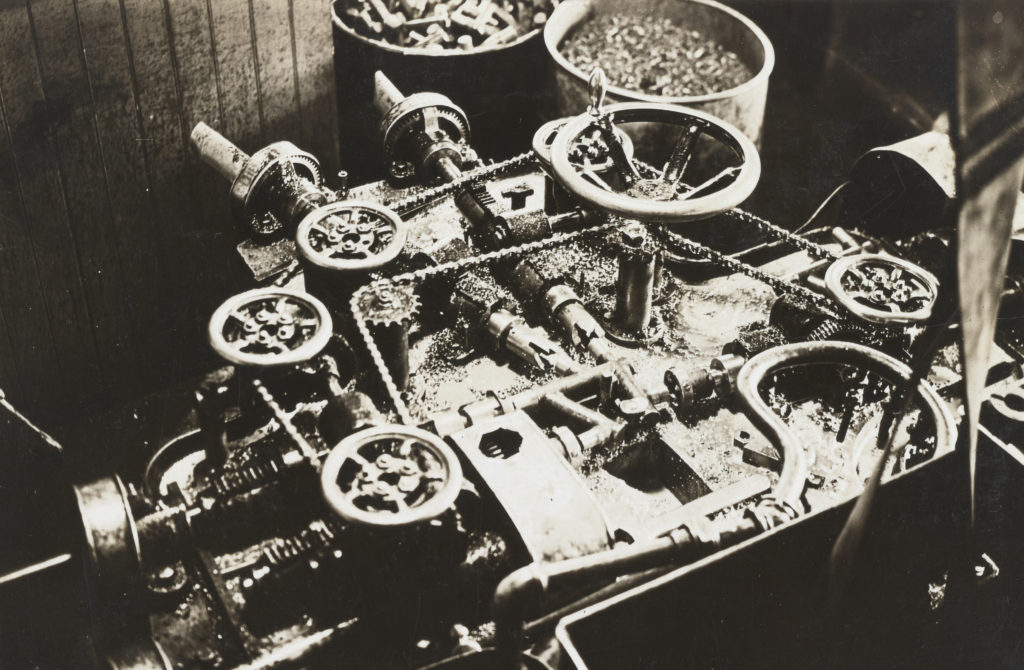

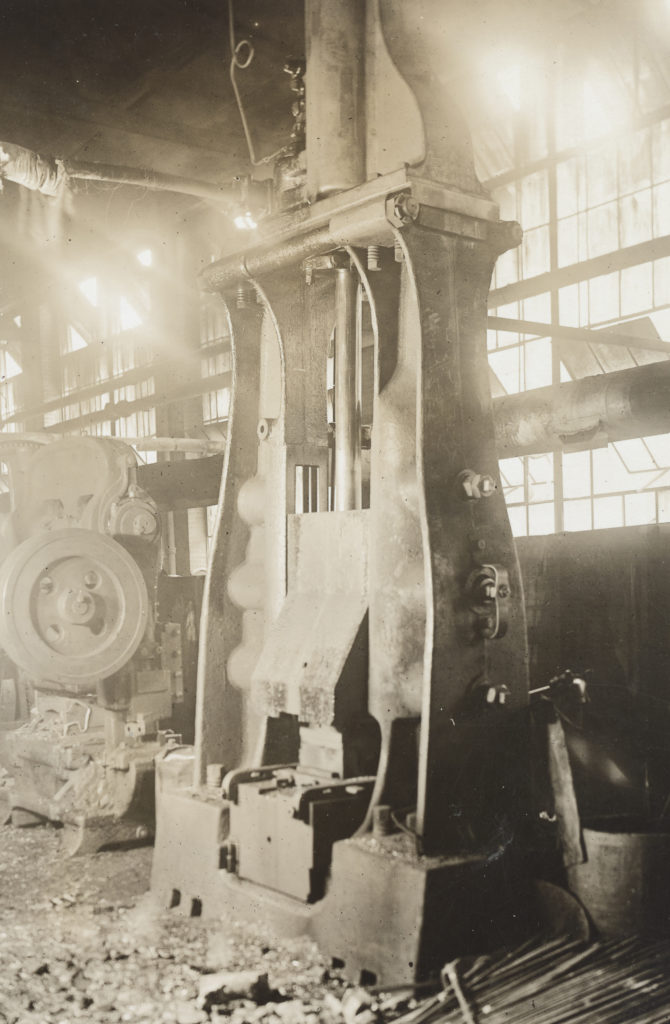

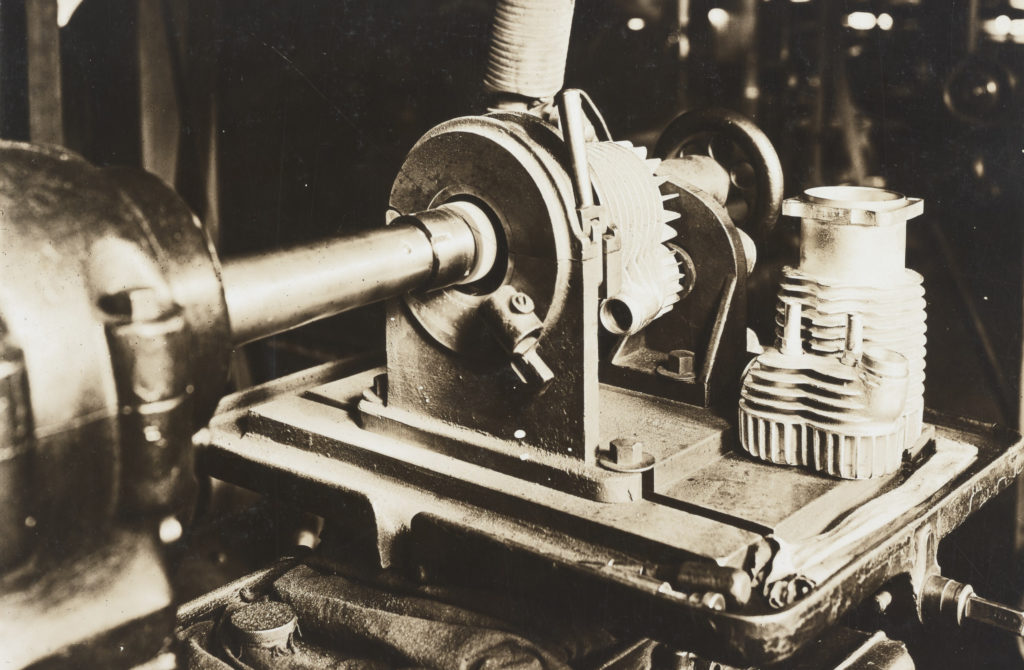

A few comments: The Springfield factory photos reveal the enormous gap that existed, circa 1918, between Ford’s state-of-the-art Highland Park colossus and the world’s largest moto(r)cycle maker. Being a student of the former, including authoring a Model T history, I believe the Springfield factory was a generation behind Ford, in terms of process and technology, at this time. Henry owned a Henderson Four, by the way.

Also, your preamble regarding American society pre-WWI and the influence of the Great War on America’s military contains arguable points. Socialism’s utter failure to take hold in the US was a constant frustration to Marx and Engels, both of whom acknowledged the reasons why early on. I recommend this book: http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/l/lipset-here.htmls. Socialism’s few US adherents were mainly urban, not rural: the American farmer was clearly no fan!

There was indeed plenty of discussion in the US about the airplane’s use as a weapon, beginning with the Wrights. But unlike in Europe, there was little development of viable combat aircraft here prior to WWI. Finally, after WWI the US went back to sleep, militarily, until 1938-40 when the need to face Hitler and Japan became undeniable. America’s current military-industrial complex, like it or not, was established post-1941, rather than with the Doughboys in 1917-18.

Sorry for the faulty link: the book I referenced and recommend is “It Didn’t Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States,” by Seymour Martin and Gary Marks, W. W. Norton & Co.

Great pictures, the detail is fantastic. Being the lucky owner a 1919 Power Plus, its great to think you’re looking at the guys who actually built the thing. Also knowing who to blame when it goes wrong!

Hey, that’s the guy screwed up my layshaft! :0

In the NJ motorcycle battery picture caption, the machine gun described as a Colt-Martin, there is no such thing, That machine gun is a Colt-Browning M1895 “potato digger”, so called because of its unusual action when firing. Otherwise, a great presentation.

Interesting! That’s what’s written on the photograph’s explanatory text from 1918! I’ll make a note on the photo; thank you for clarifying.