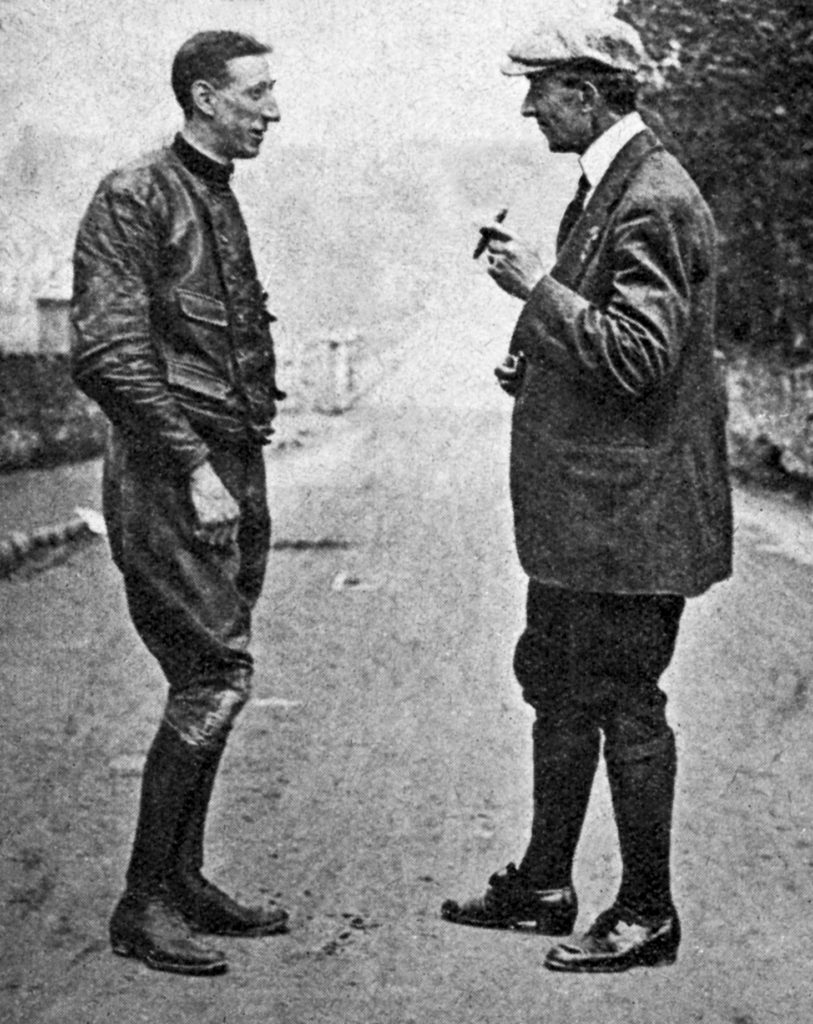

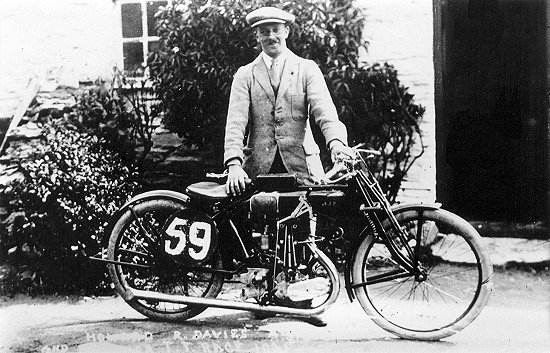

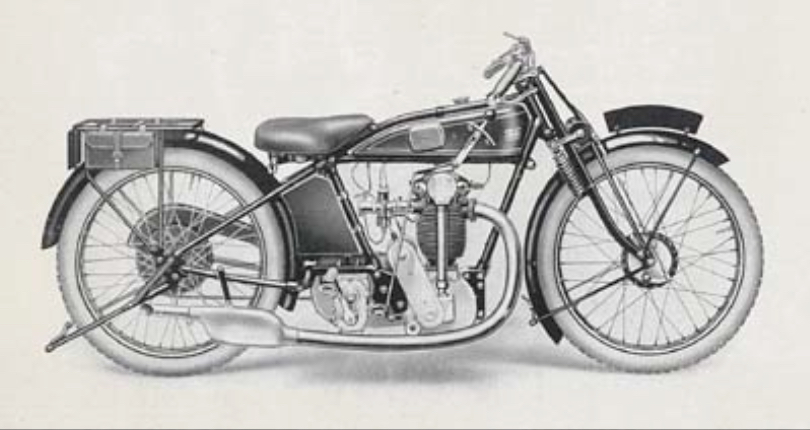

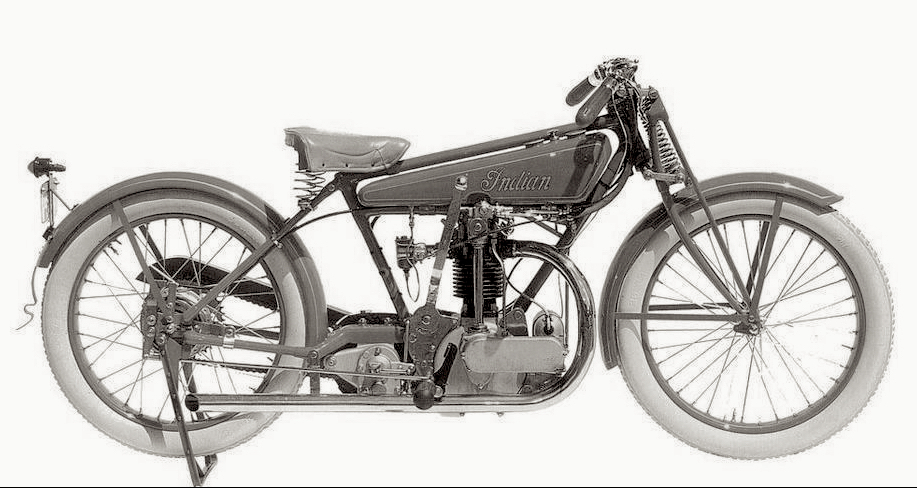

Indian continued to send factory specials to Britain up until that country entered WW1 in 1914. After the war, when racing resumed, Indian carried on giving factory support to riders: the first Isle of Man TT was held in 1920, and HR Harveyson made 5th place on a 500cc Indian Scouts, while his team-mate DS Alexander made 6th. The first four places in the race were taken by Sunbeam (Tommy DeLaHaye won on one) and Norton sidevalve singles, so CB Franklin, Indian’s chief designer, chose to make ‘half a Scout’ – a sidevalve single – for his European racers. Indian’s best result at the Isle of Man TT in the 1920s was taken by professional racer Freddie Dixon, who managed 2nd place in the 1921 Senior, on a factory-supplied 500cc sidevalve single. He was beaten by Howard R Davies (who soon founded his own motorcycle brand – HRD), in the only instance where a 350cc machine won the Senior TT!

Related Posts

August 9, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 4: Oliver Godfrey

Oliver Cyril Godfrey won the 1911 Isle…

July 27, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 1: Billy Wells

Over 100 years ago, Indian swept the…