The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world’s rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

Too much tap, tap, tap on the Mac, not enough wrist-turning brrumm brrumm, makes Jack a dull lad. So, at the end of the northern hemisphere’s riding season, on a cool but clear morning in London’s Chelsea district, the offer of a road test on a nice old Brough Superior was like a cup of warm tea in cold hands: a very good idea.

Super read! Good to see a machine like this on the road where it belongs! I prefer this kind of bike to a showstopper that is stored in a museum or worse; in a vault. Great story, thank you!

Anton, Netherlands

Nice to see a Classic being ridden rather than trailered

Reading this though begs the question from myself

Am I the only one that wishes one of the Modern Manufactures would produce a reasonable weight ,straight forward , unfaired , low , comfortable , what I’ve know as a gentleman’s Roadster M/C for the modern era ?

Guitar Slinger

Paul,

A good front brake on a Monarch-forked SS80 is quite possible. It requires some effort in using soft linings, skimming them so that the maximum amount of contact is made with the drum (seeing that the drum as laced in the wheel is fairly round) and using a conventional (instead of the inverted) long lever.

With the sidecar on the ’38 SS80 I’ve had for 42 years it is possible, when linings are quite fresh, to lock both the front (and back as well for that matter) wheels.

Any front drum brake from the ’30s (and later, in racing use, Michelle Duff once told me) will fade on repeated frequent stops so I have modified the front brake lever on the SS80 to incorporate an adjuster.

Also. Last winter I made and fitted a Karslake propstand which i machined from parts supplied by the Brough Club. I have had no grounding problems due to the stand. From the picture you showed of the ’36 SS80, I suspect that a little re-alignment or alteration in the location of the toe peg might solve the problem.

Incidentally, if the standard Brough “fishtail” is fitted to the silencer it reduces both the idle and 2000 rpm SAE test noise level values by 3 dBA. My SS80 with fishtail was 79 dBA at idle and 90 dBA at 2000 rpm when tested last year. The proposed SAE limits are 92 dBA at idle and 96 dBA at 2000 rpm. The Brough is therefore less than 1/4 of the allowable idle level and 1/2 of the 2000 rpm level for bikes made as much as 70 years later. Perhaps George Brough’s claim that the late SS80s were the quietest bike on the British market, and the SS100 the second quietest, has some merit to it?

Nice read Paul and not a bit about stylish wear (thank god), but that is a nice photo of you turning left and looking right…

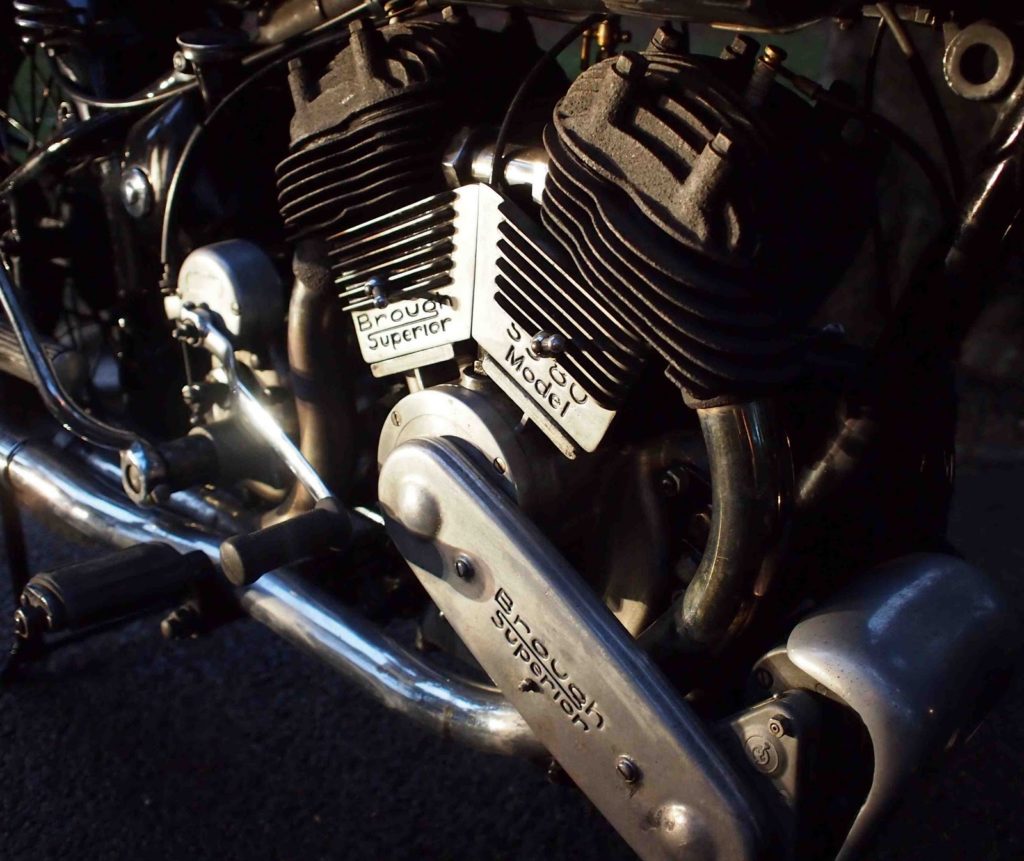

Typical d’Orleans piece: Elegant and insightful prose, relevant and nicely-composed images. SS80–Brough’s ‘affordable’ model! Just don’t call it a ‘flathead’….

Wonderful piece on a beautiful bike, thanks Paul!

And through it all – Gentleman of Wealthy Buyers still have the punch of a motorcycle in their blood. We are a different sort for the love of a two wheeled machine. Well said of the Brough with its tales of entitlement. One could believe you can fall in love with the machine. George was its biggest cheerleader in bravado- he could back it up. How much to buy one you ask? Gentleman do not discuss price. Its already understood you are member of the club. Thank you all for a Wonderfull life of passion – two wheeling. Some just never get it ! Do they?

It’s interesting that George Brough included ‘successful tradesmen’ as among his clients in his PR: I bought my first four Brough Superiors during my (successful) career as a decorative painter/muralist; they were a financial stretch but one I considered worth it. I sold them all around 2000 to purchase a supercharged 1925 Zenith-JAP V-twin, ‘Super Kim’, and didn’t ride another Brough in earnest until the 2014 Cannonball, when I rode an 11.50 across the USA in partnership with Alan Stulberg of Revival Cycles.

That stoked the fire: last year I purchased another Brough Superior, a 1933 11.50 with JAP sidevalve 60deg V-twin, that George himself considered his favorite model of the 1930s. It was a bigger financial stretch, but still possible, as is this SS80-Matchless model, which can be found easily for under $100k. That’s a lot of money, but for a ‘successful tradesman’, still possible. The early SS100s have moved into Fine Art territory though, and fetch closer to $4-500k, which is definitely not affordable!

I’ll take you to task Paul, on the front brake, part of the myth that BS front brakes are no good stems originally from the earlier 8 inch Enfield unit used from 1928 or so.Its design is poor and with use the drum will flex. Add many years of use into the 1950s— to the extent that the bikes were almost worthless , then no one cared about brakes.

Weld the drum to the spool, stitch weld where the 6 rivets are on the drum inner plate ,then machine the brake shoes on the brakeplate . My sons 1928 SS80 has an 8 inch front stopper that is as good as it can be.On the old MOT test rig it pulled more stopping power than the 8 inch rear.

To a greater extent the later seven inch is the same,but the steel drum itself is far better design.Once again machine the linings on the brakeplate & you get results. The very last 7″ front drum of 1939 had a cast iron drum, which was infinitely better then the steel one.On my 11/50 I could get the front brake to squeal under hard braking. Lastly I always use original Ferodo linings rather than the modern asbestos replacement stuff. NEVER have a drum machined true if you can help it . Over zealous wheel builders can pull a drum out of true .I have trued drums by the simple expedient of altering spoke tensions back to where they should be.

Dave, I’ve ridden a lot of Broughs, and never come across one with a decent front brake, so your method is an anomaly, and one I’ll investigate! The older I get, the more I value a good brake – I didn’t care much in my youth, preferring only to go fast!

Lovely Bike.. And the dual exhaust on the SS100’s inspired me to install a similar style on my old VL.

I would be honored if someday, you would take my old bobbed bike around the block…A 101″ flathead

twin is rare but it has been up and running for over 20 years now.

I Got to see this bike at vintage motorcycle days Lexington Ohio it is now in the hands of a friend of mine what a nice machine