Franz Mohr was interviewed in a German magazine in 1949 about his fantastic creation:

“After the end of the racing season in 1947, during which I drove a refurbished BMW R75M engine in its original Wehrmacht frame, I came up with the idea to convert this engine into a overhead camshaft motor. Thanks to the energetic support of the well-known racing driver Kurt Fuglein, the financial basis for such a project was established.

New parts included two new crankshaft drive housings, screwed to the former magneto shaft; two camshafts connected to the crankshaft by two shafts; four special gray cast iron cylinders with four large square-threaded cylinder head bolts; 4 cylinder heads and valve covers, for which first models were made; 8 rocker arms; the associated axles, bearing housings, valves, and camshafts. The cams, made by hand, had to be ground one degree at a time, since no cam grinder was available for us; 8 output housing for the conical shafts and their bearings, lock nuts, protective tubes with rubber rings for oil seals.

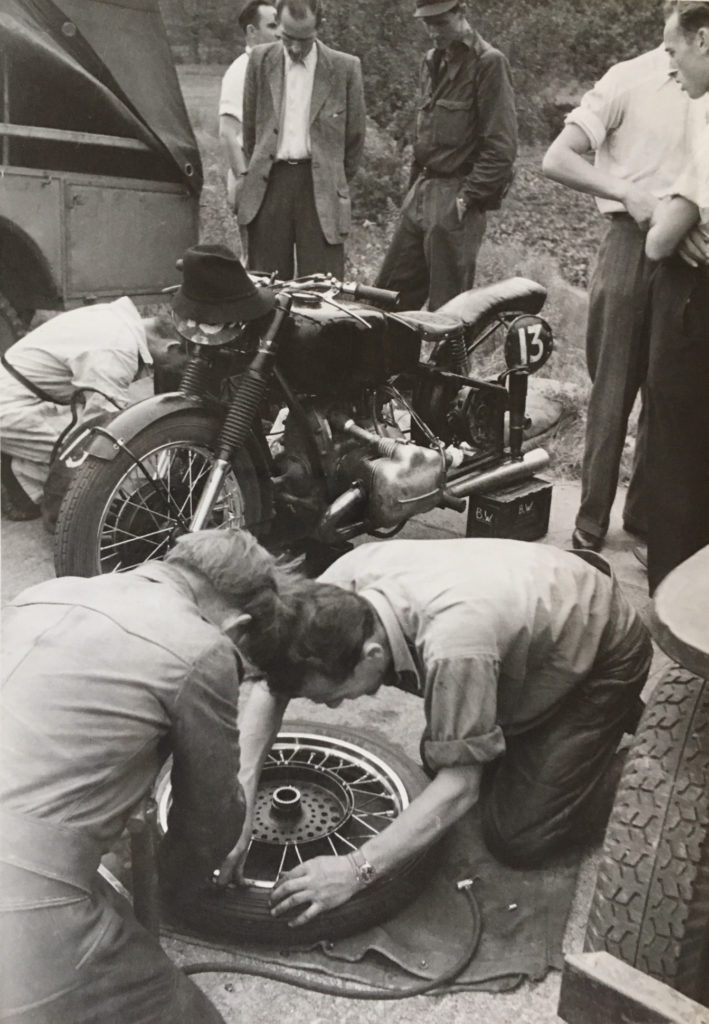

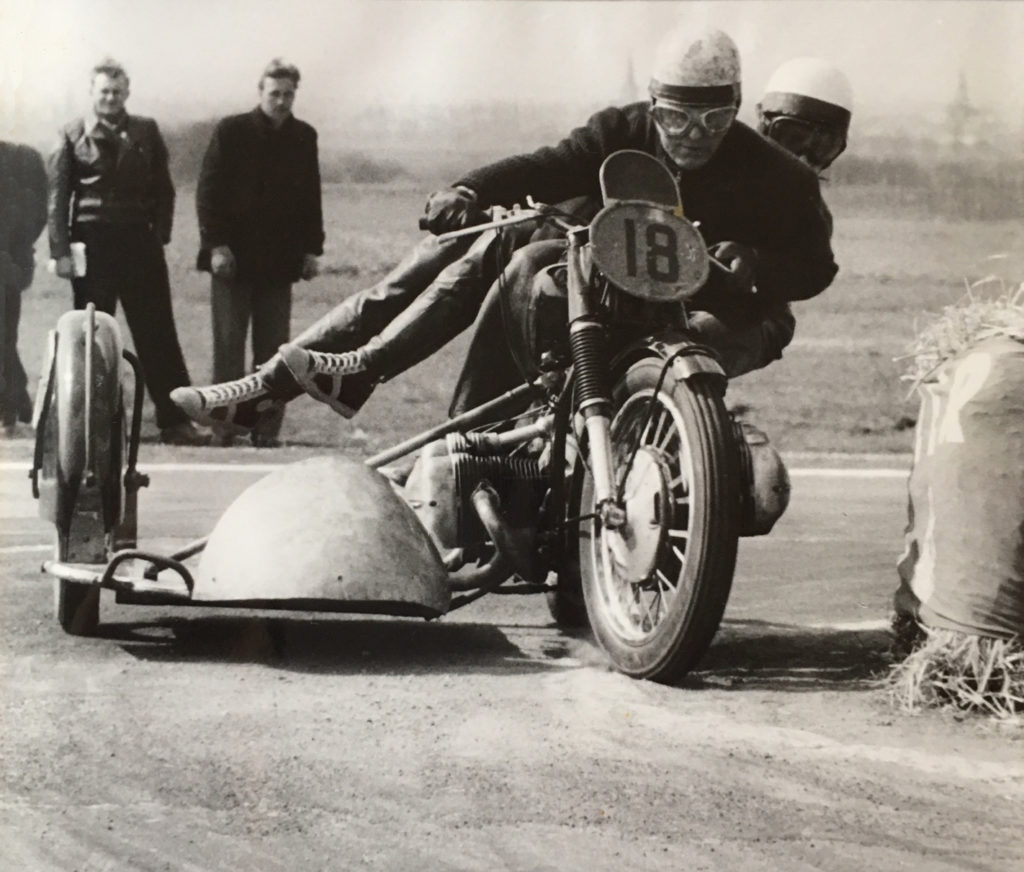

But one day it was finally time. Perhaps the readers will be able to gauge what this was for us – that inner joy – all the effort, all the hate was forgotten, and we listened to the engine with devotion. A few days later, on July 4, 1948, was the Garmisch race. With the new engine, I drove the fastest practice time, but then had to replace the bike and race my old loyal R75, as our camshaft shapes had to be changed. Within eight days we had made new camshafts, and in Karlsruhe I easily won the first prize. Another eight days later, we drove in Reutlingen, setting the fastest lap of all sidecar classes with 83.6kmh, but could then hold only second place due to clutch problems. Again, we had to make a new clutch, because the high engine output of our OHC motor resulted in failure.

For the first time, I returned to the Grenzland track and achieved the fastest practice time. By an most unfortunate event, I retired in the second lap of the race: the undisciplined behavior of the spectators, who compared the route to a wastebasket, was to blame. A large bag, without being noticed by me, caught on my left cylinder, blocking its cooling: the piston melted, and molten aluminum stuck on the crankshaft. By the way, Eberlein (a factory BMW racer) fared just as well, – his motor ate a scrap of paper and tore off his cylinder.

Now a short summary of the entire working hours:

Design hours: 580

Planning, making tools: 250

Pattern-making hours: 1000

Machining hours: 2500

Assembly hours: 950

Testing and fettling: 500″

[If you’ve ever considered building your own motor, or wondered at the expense of custom machine work, the above hours are sobering!- ed.]

Fantastic story! Thank you.

Fantastic story! Thank you. What an époque that was

Such an INSPIRING story that SHOWS what dreams, determination and persistence can DO!!

The R75 engines were occasionally used by the factory too. The French would put capture R75 engines in R-71 frames and they were refereed to as R73 ( 75+71=146/2=73 ). Another “hot” conversion was grafting a K-601 Zundapp tranny and differential to a BMW. The Zundapp transmission ( a series of chains) was considered more reliable.

I have a friend in San Francisco with just such a machine, a proto-cafe racer from the 1940s, not sure where it was built but it’s an R75M engine in an R71 chassis, with a Schorsch Meier RS tank. Nice early cafe racer…

Zundapp KS 600 motors were also “grafted” into of factories frames too.

can send pix if interested?

Would love to see such photos, Adrian! Send to Paul@thevintagent.com

Interesting piece, Paul, to your usual high standard. But your intro statement (“the victorious nations couldn’t stomach the thought of losing a race to competitors from a country they’d been at war with for 6 years”) needs a shot of historical reality. By “victorious nations” here we really are talking about Britain primarily, as it was the hub of motorcycle sport. And frankly as of late 1945 the Brits, ever the sportsmen, had the shits of the fucking Germans. Six years of being bombed and rocketed from aircraft that were the real focal point of the supercharging and advanced alloy development that had put BMW, Auto Union, and Mercedes on GP podiums in the ’30s…enough already. It would have been disgraceful for Germany to have been welcomed back into international motor racing during the immediate postwar period. Hey, no hard feelings…

The result of the FIM “banning” supercharging was the end of Velocette’s “ROARER” racing motorcycle.

that then led to the scrapping of them releasing the “MODEL-“O”–street machine. what a loss!

Are you sure it was the F.I.M.?—-I thought it was the A.C.U. of G.B.! (Auto Cycle Union.)

Well, ‘victorious nations’ must include the French and Belgians (regardless their status as occupied during the war), who were also hubs of motorsport on the Continent, hosting more Grands Prix than Britain, plus the important scene at the Montlhéry speed bowl and Arpajon record-breaking straight. By the very late 1930s, no French machine could compete seriously with Brit/German/Italian racers, but FN and Saroléa racers filled the ranks of Continental events, and did honorably well. All suffered under Hitler’s megalomania…as did, let’s not forget, many millions of Germans (my own family included).

Your points are entirely valid, of course, and there’s an interesting cultural study waiting to be written about the relationship of various governments to motorsport and domestic motorcycle production over the past century. I picture the humble race departments of Norton, AJS, and Velocette, contrasted to the industrial research centers at BMW, Gilera, and Moto Guzzi, which looked like the industry of today, minus the robots.

Thanks for posting, Paul. Great story indeed. The MFK has similarities to the Rennsport Type 253 motor. What do you think the connection is?

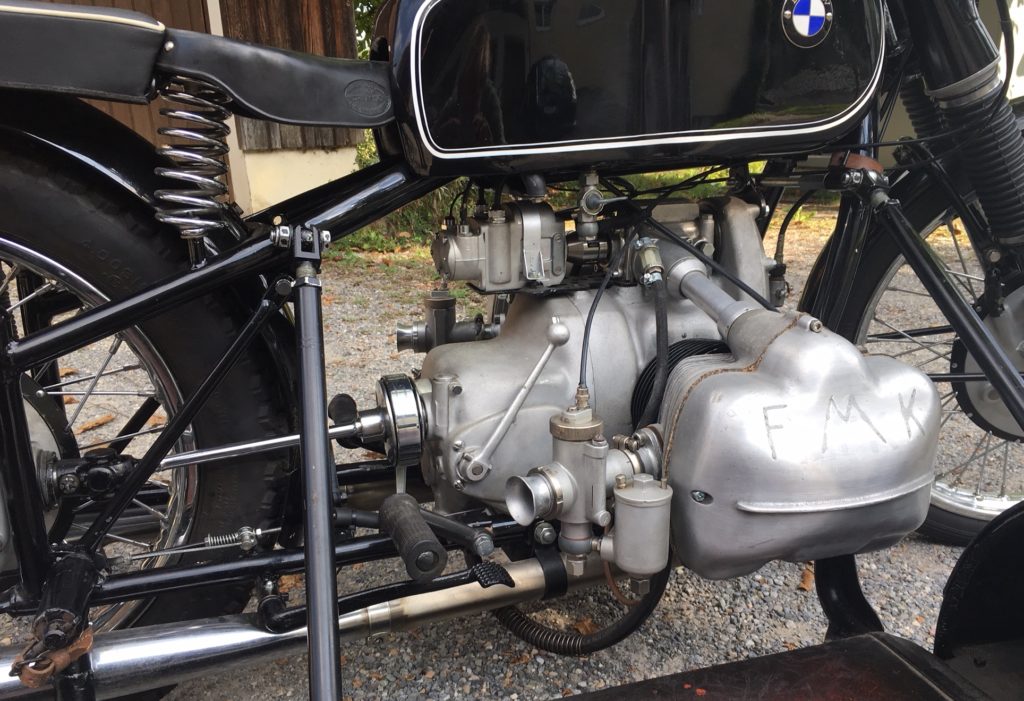

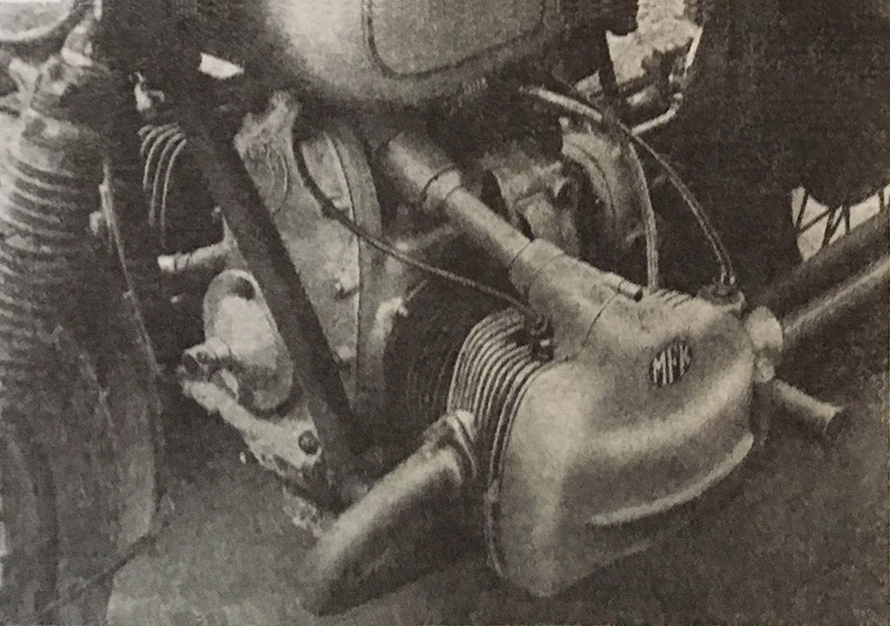

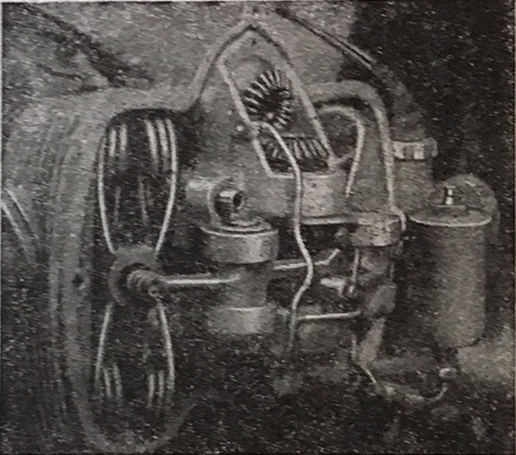

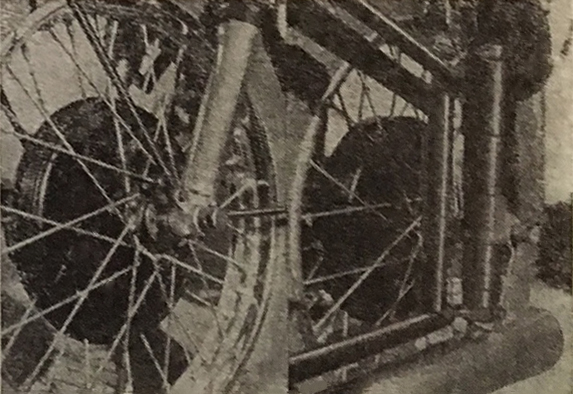

Interesting question: the OHC M255/2 (the BMW engine code) supercharged Rennsport motor is similar in layout but very different in detail. The MFK uses the existing BMW R75M timing case at the front of the motor, which uses gears to drive the magneto at the top of the engine. The MFK instead drives a shaft on top of the motor in place of the magneto, that drives the two cylinder shafts from a crownwheel and pinion gears on top of the motor – on the Rennsport the shafts are under the cylinders. The MFK’s engine-top shaft carries on to drive the magneto, which sits further back over the gearbox. The BMW RS motor is double-overhead-camshaft, while the MFK is a SOHC design. The layout is very simple and clever, as is the drive system: they kept the R75M crankcase intact, and didn’t try to make a drive system inside the crankcase, as the BMW does. If you look closely at a couple of the engine photos, it all becomes clear – they didn’t reinvent or recreate the RS255, but adapted the military engine to suit their needs.

Excellent! Thank you.

Now how about a look at Helmut Fath’s incredible homemade engines?

I spent a summer working in Germany, rented a room from a nice family. Wandered down to the basement one day and, like Alice going down the rabbit hole, was stunned to find a complete WWII era machine shop. Having some training in that field myself it was immediately apparent that this had been the lair of a master machinist, the grandfather.

The family had three sons around my age — none showed even the slightest interest in the machines slowly gathering dust beneath their feet.

The Germans…..