By Peter Henshaw

It normally takes two or three years to design and prototype a new motorcycle. Using existing components saves time [as with the Ducati Monster – ed.], but even with cutting corners, the process takes many, many months. But the design engineers at Norton-Villiers, Bob Trigg and Bernard Hooper, were given just eleven weeks in 1967 to come up with a new model for the aging Norton lineup. There was no time to develop a new motor, so Norton’s existing 750cc twin-cylinder engine was a given, but they had to find a way to tame its fearsome vibration. Trigg and Hooper came up with the Norton Commando, a hastily designed stopgap that became an icon, keeping Norton afloat for the best part of a decade. And, let’s just repeat this, they did it in eleven weeks. How was this possible?

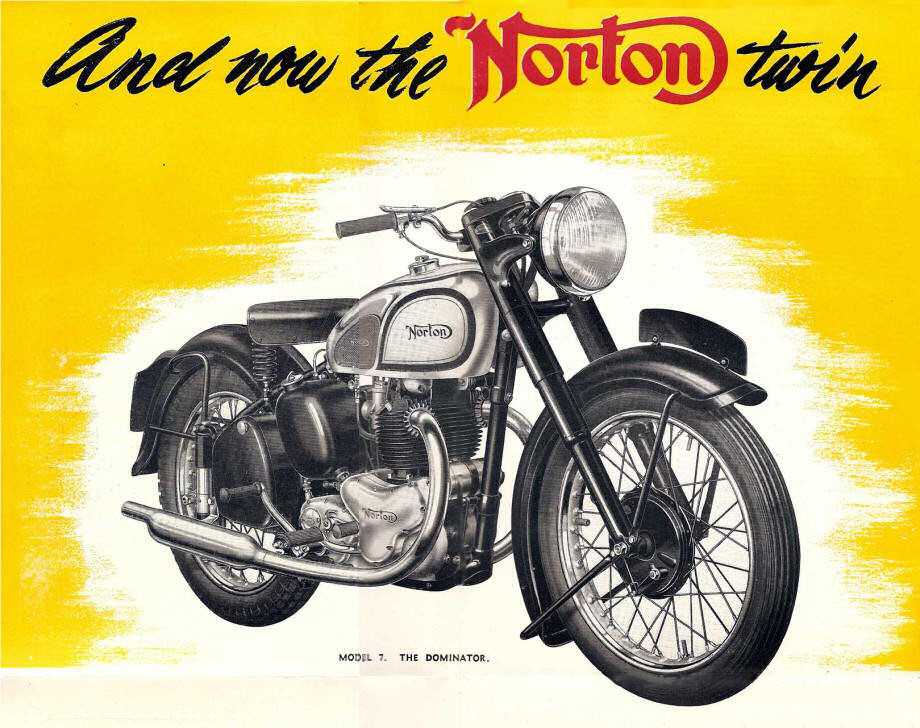

The roots of the Commando story stretch back to 1949, when Norton launched the Dominator, a 500cc parallel twin to rival Triumph’s incredibly successful Speed Twin. Norton’s twin was drawn up by Bert Hopwood, one of the giants of Britain’s postwar motorcycle industry, who tried to cure a few flaws in Edward Turner’s Triumph motor. Turner’s engine had a tendency to run hot, it was mechanically noisy, and it leaked oil through its many components – especially the separate rocker boxes and pushrod tubes. Hopwood’s Norton twin had well splayed exhaust ports to improve airflow, a single chain-driven camshaft to reduce noise, plus integral pushrod tubes and rocker mounts to prevent (some of the) leaks.

The new Norton parallel twin Model 7 Dominator was well received, but Bert Hopwood left Norton before it went on sale, in frustration over the company’s fixation with racing its increasingly outdated big singles. Six years later he was invited back, as Managing Director, in a bid to turn around the company’s ailing fortunes. With a new emphasis on road bikes, talented engineers like Doug Hele were promoted or brought in; tighter financial controls were introduced and a deal was done with Joe Berliner to distribute Nortons in the growing North American market. A smaller twin was introduced, the 250cc Jubilee, and Norton made a £300,000 profit in 1958.

Despite the profits, Norton’s parent company – Associated Motorcycles (AMC), owner of Matchless, AJS, James, Villiers, and Francis-Barnett – was leaking cash, and absorbed Norton’s profits into the group. In the summer of 1966 AMC reached a crisis point, and when a deal to source working capital from Joe Berliner fell through, the company went bust.

Mr Poore wasted no time, dropping the slow-selling James and Francis-Barnett lines from the AMC stable as well as Norton’s smaller Jubilee, Navigator, and Electra twins. He knew what the trimmed-down Norton-Villiers division needed was a new flagship motorcycle. The Norton Atlas 750, launched in 1964, was a torquey beast – the biggest British twin on the market, with the Royal Enfield Interceptor – but it suffered appalling vibration above 5000rpm, because the increase in engine capacity came via a long-stroke crankshaft: there was no money to design new crankcases for a short-stroke 750cc engine, or add modern balancing shafts.

A redesign got underway in early 1967, aiming to have the new bike ready for the Earls Court Show in September. It would use the P10’s bottom end with a new top end using two short timing chains and simple bucket-and-shim tappets. While this was heading in the right direction, there simply wasn’t time to develop this all-new engine in six months. In desperation, Poore summoned design engineers Bob Trigg and Bernard Hooper to a board meeting in London. Both were young, with impressive pedigrees: Trigg had cut his teeth at BSA and Ariel before joining Norton-Villiers, while Hooper had worked with the renowned Hermann Meier on racing two-strokes.

Bob Trigg recalled, “We were would told that if we didn’t have a new bike at Earls Court that year, the company would go bust. And we couldn’t have a new engine, so we would have to use the Atlas, due to lack of time and money.” And one more thing, they had to find a way to eliminate the big twin’s vibration, which was increasingly unacceptable in North America. It was, to say the least, a tall order.

On the train back to Birmingham, they got to work. Trigg suggested rubber-mounting the engine to combat vibes, which of course had been one of the P10’s bugbears, but Hooper thought he had a solution. Engine, gearbox and swinging arm, as a single unit, would be rubber mounted, but with the swinging arm mounted solidly to the engine to overcome the chain pull problem. If the whole assembly was kept in a single plane fore and aft, the wheels would stay in line, and there was a chance the bike would still handle well.

Back at his drawing board, Bob Trigg got to work. Rubber specialists Metalastic were too busy to help, but did tell him that the rubber had to be a high enough rate to absorb the vibration – if the rate was too low, the vibes would simply destroy the mounts. In quick time, an initial prototype was put together and tested on the factory’s internal roads. The new system did cut vibration, but only over 6500rpm. Norton’s Engineering Director Stefan Bauer, who had little motorcycle experience but was a lateral thinker, told them to slice the mounts in half. Trigg thought that would reduce their life, but did as he was told – now they cut vibration over 4000rpm. Again, Dr Bauer said, slice them in half.

“We took the bike up the road,” said Bob Trigg, “and it was like being in an aeroplane, bumping along at low revs and then at 2300rpm it would smooth out. And that was great, because you could still feel a big twin under you at very low revs, but it took all the hassle out of vibration when riding.” At that point, the Norton Commando was born.

Given the time constraints, Bob Trigg assumed they would modify Norton’s existing Featherbed frame for the new bike, but Dr Bauer insisted they design from first principles. Dismissing the hallowed chassis as “a Christmas tree,” he sent Trigg back to the drawing board, and the result was elegant: a frame with almost every tube straight, which weighed only 24lb. Some existing parts were retained, like Norton’s excellent Roadholder forks. Then there was the Atlas engine, a long-stroke iron-barrel vertical twin of 745cc: the design harked back to Hopwood’s 1949 original, but as a 750cc it was bursting with torque and power – a claimed 58bhp at 6500rpm, not that anyone could ride it at those revs. The Atlas’s separate four-speed gearbox was carried over too, but the Commando did get a new diaphragm clutch to reduce lever effort and a triplex primary drive with single-bolt alloy cover.

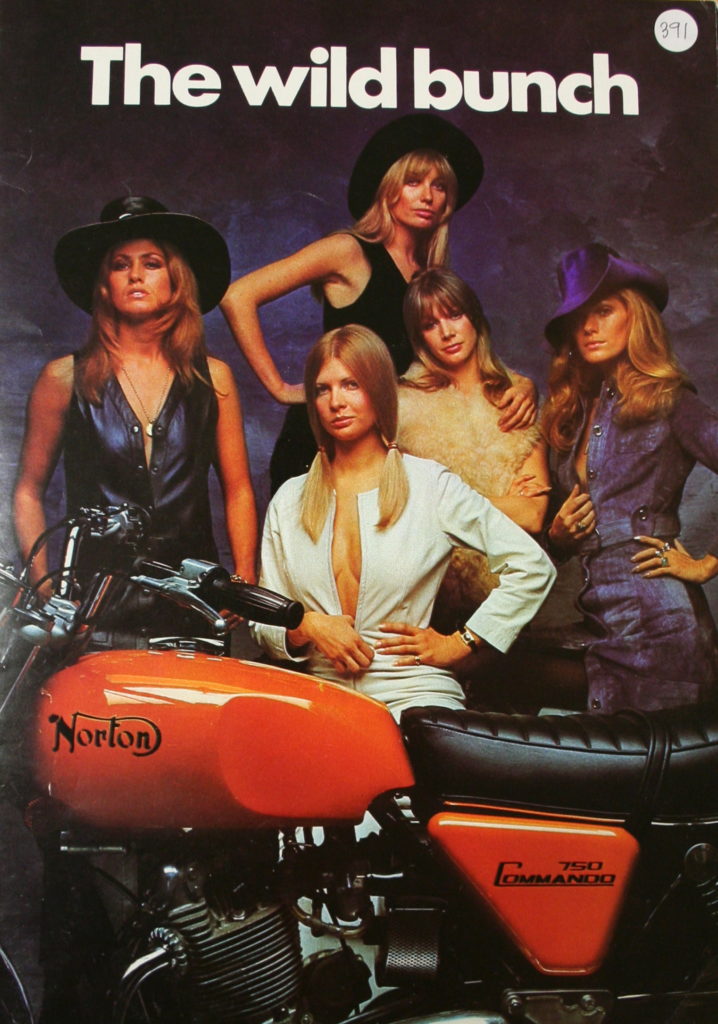

As the summer of ’67 drew to a close, the final touches were made. Bob Trigg had already given the Commando its distinctive canted forward engine with rear shocks at a similar angle, but Dennis Poore wanted radical styling to match the new concept, calling in the design consultancy Wolff Ohlins. They came up with the one-piece seat and tail unit blending into the tank – the Commando Fastback.

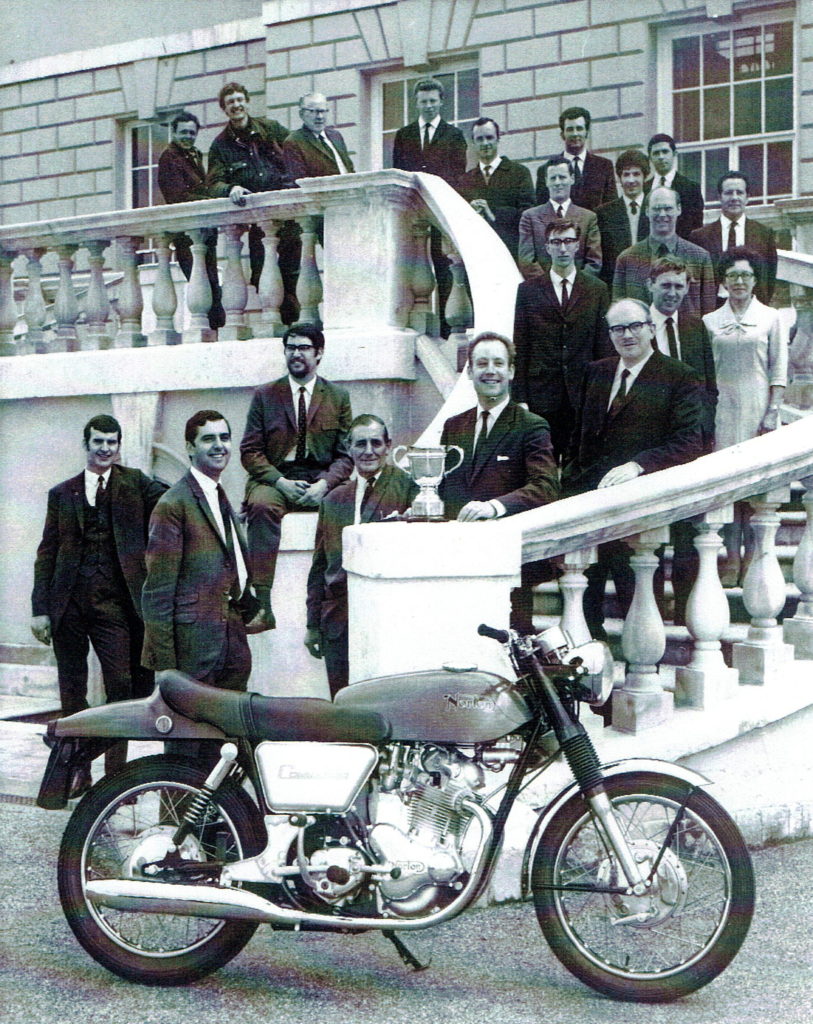

Hastily sprayed a shotgun silver metalflake, and with just 1000 test miles under its belt, the prototype Commando made it to Norton’s stand at the Earls Court Show in September. Years later, Bob Trigg reflected on those manic eleven weeks, “I worked all the hours God sent and lost over a stone in weight, but we did it. We all worked on it as a good team, and we couldn’t have done it any other way.”

The Commando was a miracle of expedience, as it became a motorcycle for the ages, but it could only have been built under the direst of financial and time constraints. It won ‘Motorcycle of the Year’ for five years running in Motorcycle News reader’s polls, and even hardened journalists were amazed how good the Commando turned out to be. There should be a lesson for future designers in the story, but perhaps the lesson is one of management: Dennis Poore applied the pressure, and Norton’s development team produced the diamond.

Bernard Hooper was the co-designer not Dennis Hooper.

Thanks for the correction!

I did not realize that the road holder forks that go with my vintage feather bed frame were an actual Norton product. Thanks for the info.

Without detracting one iota of credit from Bob, the design of the Commando was more of a team product (as always with success) than your excellent story describes. I feel that you should also include Dr Stefan Bauer, Tony Dennis and John Favill (the latter who, after the demise of Norton, sorted out the Harley Davison quality problems and who still lives in America).

Peter, many thanks for your reminder: something as complex as a motorcycle takes many hands indeed, some of whom will never get the credit they deserve. Yes, Peter Henshaw did a great job on the article. I missed that John Favill went to H-D after Norton – there’s a story waiting to be told…

In light of your feedback, I realize my conclusion for Peter’s article gave too much emphasis to two designers over the whole team: that’s been amended. Thanks again.

Peter Williams, fair comment, I have put together a website about the sister machine, the AJS Stormer, it also covers the Norton Commando, amongst others and the people involved in these machines development, including yourself.

If anyone would like to know more about these machines and the people involved, I attach a link for you,

https://ajsstormer.wordpress.com

thank you Peter for your article, doing the Ton on a Commando is the closest thing to flying, Cliff.

Where to start with this one? The root cause of the 750cc Atlas engine’s significant vibration issues wasn’t as much due to its undersquare dimensions, but rather the need (as with any 360-degree parallel twin of the Norton’s displacement) for balance shafts and central crankshaft support. The last two generations of ‘modern’ Triumph Bonneville prove this; yes, it’s an oversquare design but is now out to 1,200cc and still a smoothie!

Norton wasn’t the only maker to have a 750 in production–Royal Enfield did, too.

John Favill’s story has already been told by Mick Duckworth, both in Mick’s essential Commando history book and also in subsequent magazine articles.

Doug Hele told me during our many conversations for my ‘Triumph Racing Motorcycles in America’ book that AMC during this period was an absolute wreck–it made BSA Group look like a modern-thinking, well-run company by comparison. Norton had to stick with the Atlas lump (still with a separate gearbox!) for the very reason the British industry was in terminal-cancer straits: Refusal to invest in truly new product architectures and plant when the profits were there to do so, and refusal to take the Japanese competition seriously when the latter were still making “little bike” 250s and 305s not 750s.

Commandos–certainly a stopgap product at the time–are certainly beautiful to look at, were fast in their day, and today can be made acceptably reliable. It’s a fine platform for a patient and involved owner. But when they were new they seemed to fall into two categories: ones that blew up, and ones (particularly 850 Mk1s) that delivered many miles of reliable service. Made on a Wednesday, or made on a Friday…

Thanks as always for your input Lindsay: the article has been updated to clarify on the points you raised.

Thanks for the great article Paul. Just a side note. My friends TC Christenson and John Gregory , builder and rider of the worlds fastest drag bike for 5 years, The Hogslayer. They owned and operated Sunset Motors in Kenosha Wisconsin. A Norton shop which is still open by the way. Anyway, they had a pretty close working relationship with Norton sales team. Norton gave them a Commando in 1969 and asked them to make changes to appeal to the American market. They did that , and that is part of the reason the Commando sold so well in the states. I think we can agree that a 74 roadster looks better than the 69 fastback. Thanks again

Ken, I would agree the Roadster was a much finer design than the Fastback, which is retro-modern cool, but a bit over-styled for my taste. The Roadster is an absolute classic.

And, the Hogslayer is an awesome machine! I’ve seen it at the Barber Festival – what a competition legacy, your friends deserve significant kudos.

It would be interesting to see how many parts were unique to the Commando and how many were from the parts bin. It sounds like most came from the parts bin. It is amazing how little money was spent to design the bike and how well it sold. Too bad Norton Villiers could not improve the production build quality and at least get to reasonable specifications, such as a third main bearing and unit construction. Splitting the cases horizontally, like Honda was doing, would have solved the leakage problem, and the 3rd main bearing at the cost of a lot of design expense and new molds. Probably a few extra pounds as well.

Dennis Poore wanted to use the Triumph 750 triple as the basis for a new bike, but the Meriden strike etc ended that dream. My fantasy is a V4 using the Atlas heads. One head would have to be reversed, Unit construction, stacked gearbox and perhaps the swing arm pivot in the case and a reasonable wheel base would be possible, certainly shorter than the Ducati 750. With a 360 degree crank and a single carb per cylinder bank. Destroking the 600 twin could give a 900cc V4. Not the same as the Honda 750, but very cool!

Where did the name COMMANDO come from ?????

That’s a great question. In all the Norton books on my shelf (there are 30 of them!), I’ve never seen the reason or origin of Norton’s names post-war. The International was named in 1930 for its international racing success: it was the first Norton with a name and not simply a model number. That was followed by the Manx Grand Prix in 1936 (a production racer), and post-war the Manx from 1948, the Dominator series from 1949, the Nomad from 1957, the Atlas from 1962, the Manxman from 1962, and the Commando from 1967.

In the 1960s the term ‘commando’ was sexy in British society, meaning an elite soldier, the equivalent to a Green Beret in the USA. There was plenty of pop-culture use of the term in the title of TV shows and comic books of the 1960s, so its use for a motorcycle was not out of left field, and fit with Norton’s hard-man names for their sports motorcycles (Dominator – yeesh).

The Commando frame did not hold oil. A separate oil tank is hidden behind one of the side covers.