Web exclusive: To accompany another on-location report from the producers of the Vincent documentary SpeedisExpensive, we’re showcasing the first of a series of short films sponsored by AVON Tyres giving some clues to what will be in the final film.[by Philip Vincent-Day]

………………………

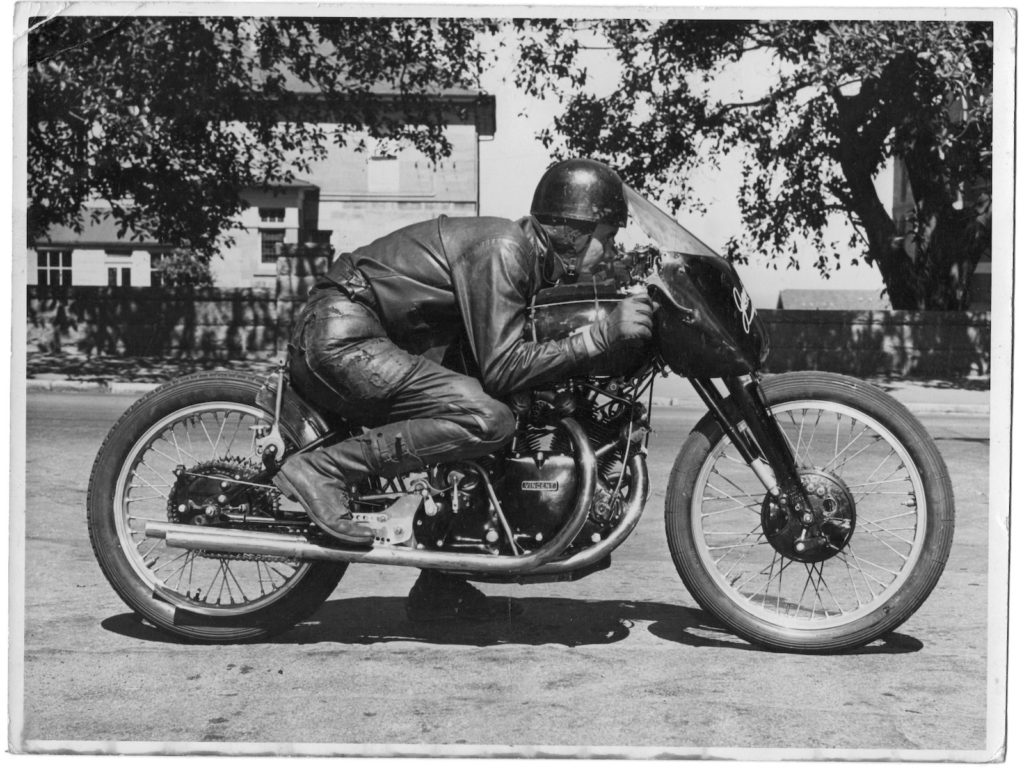

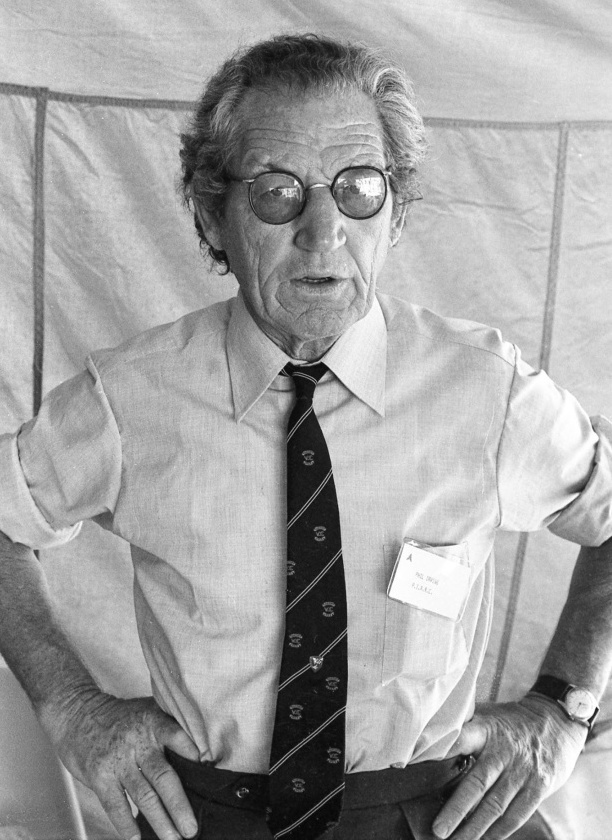

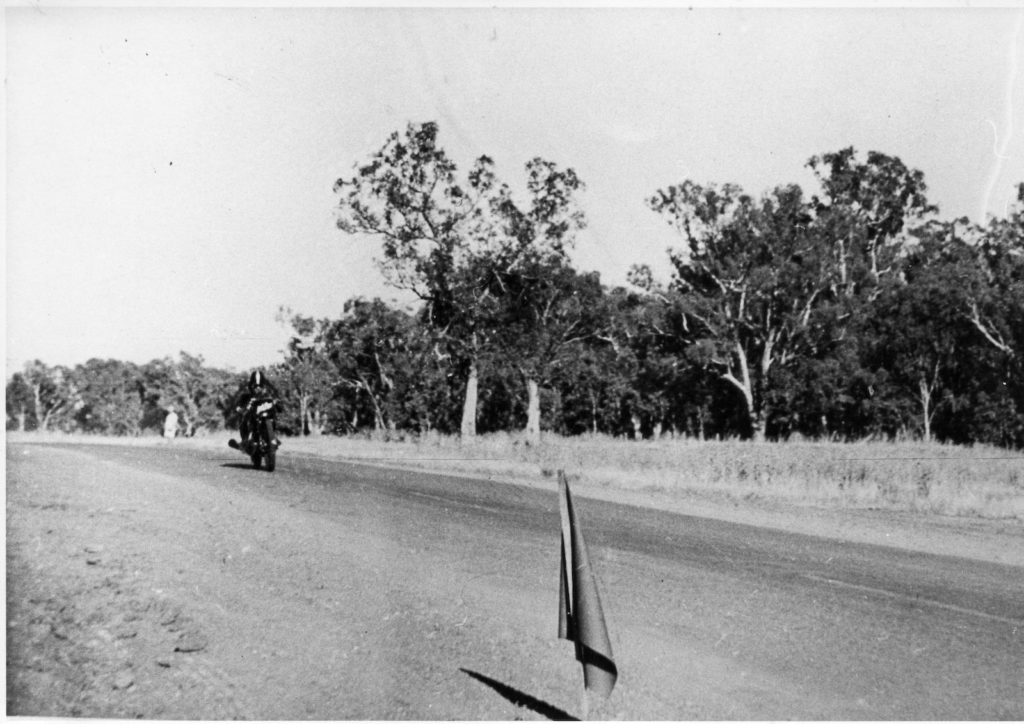

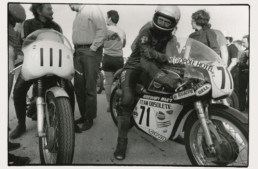

Readers may recall the post from last year in which Mike Nicks detailed our filming in and around LA (https://thevintagent.com/2018/11/03/speedisexpensive-the-la-shoot-road-trip/). We hooked up with Jay Leno to talk Vincents and reunited Marty Dickerson with his record-setting Blue Bike. In April, we embarked on another major trip: this time crossing the world to capture some of the most exciting Vincents in Australia and meet key figures in the story of my grandfather and his machines down under.

Was I mad? Did I need to do this?

The questions are ;

1) When will this be released

2) Will it be available in the USA on DVD/BlueRay for those of us who don’t do no subscriptions to online video /social media etc

3) And if yes to #2 .. when … how .. and how much … cause folks … ME WANTS !!!!!!

😎

Hi – release should be Spring next year. Conversations have started on what platforms.

Keep watching our social media feeds for updates.

Cheers,

David Lancaster and the production team behind SpeedisExpensive: The Untold Story of the Vincent Motorcycle

Errr … David …. don’t get me wrong … I genuinely appreciate the reply ….. but………….may I refer you to #2 of my comment … specifically ;

” ….. those of us who don’t do no subscriptions to online video /social media etc ”

So I guess I’ll either (A) – have to depend on the likes of Paul dO’s site ….. or (B) unfortunately despite being the Vincent aficionado that I am …. do without

Here’s hoping for A

Rock On – Ride On – Remain Calm – Carry On … and do acknowledge there are those of us both of a ‘ certain age ‘ and younger who either never have or no longer do participate in the cesspool that has become ‘ social ‘ media … which is in reality anything but ‘ social ‘ 😎

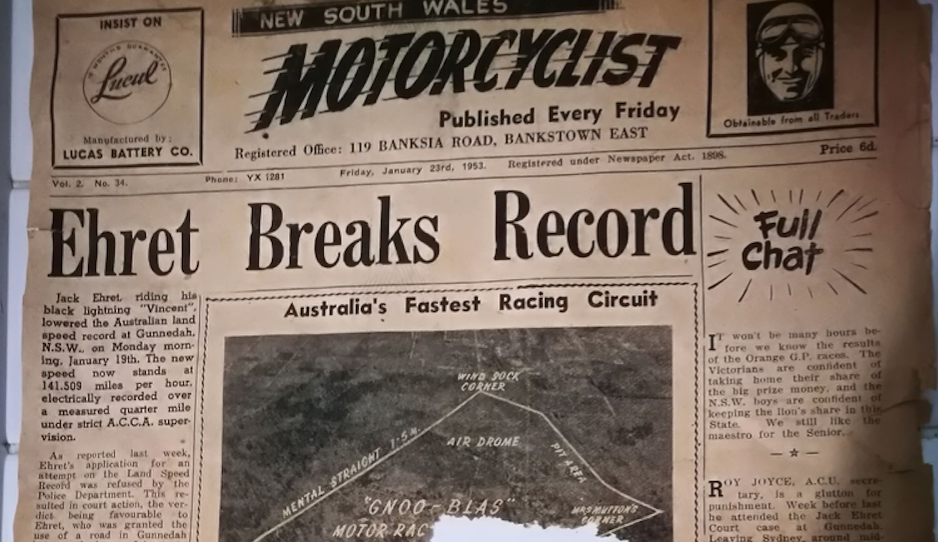

G’day David I notice my name has been misspelled Malone, if it is possible I would be grateful if you could alter it to Moline. At one stage there was a clip getting around of some of the Gunnedah filming. Is this still available? It would be nice to have a copy. Regards and best wishes to you and the crew.

Bill Moline

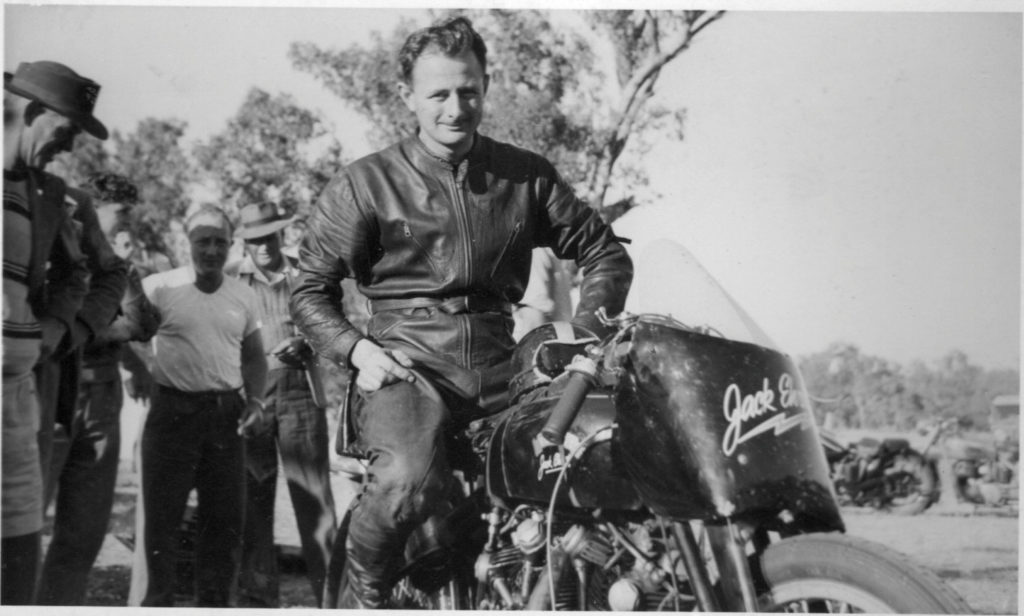

A great story. Several generations of the Jaeger family were involved in racing dirt bikes at the wonderful Porcupine Speedway in Gunnedah, from the very early days after WW2, right up until the 1980s when the Speedway finally closed.

I had the good fortune to know many of them, including Bruce, when I lived in Gunnedah in the 70s and 80s.