John Surtees - the Last Interview

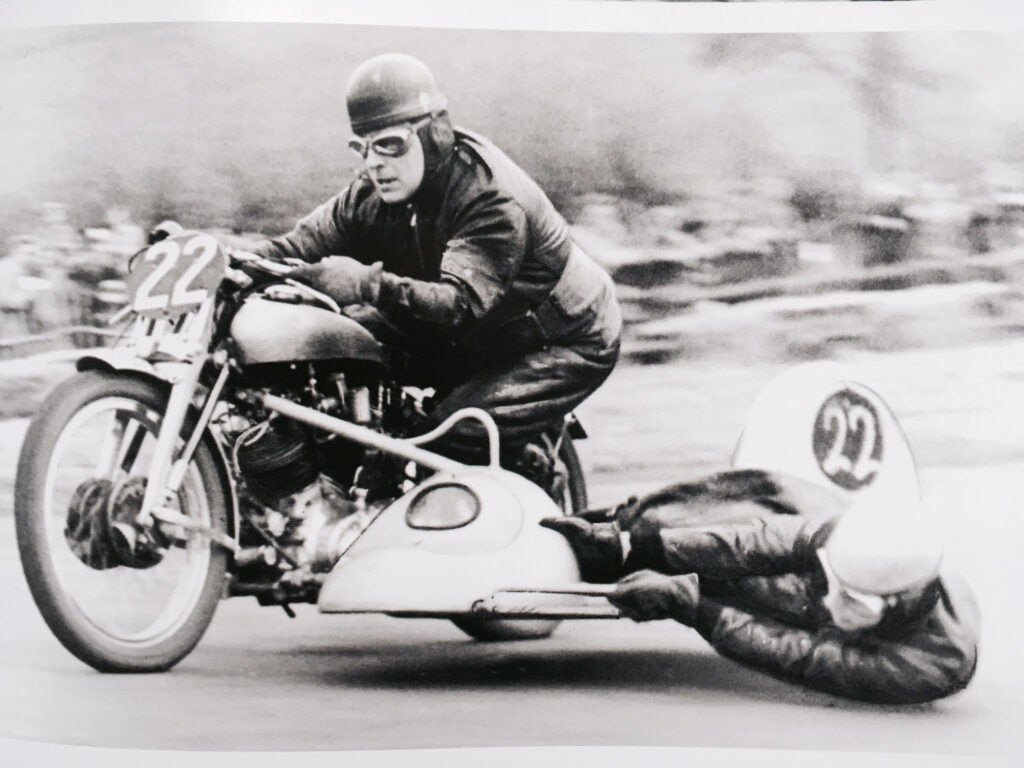

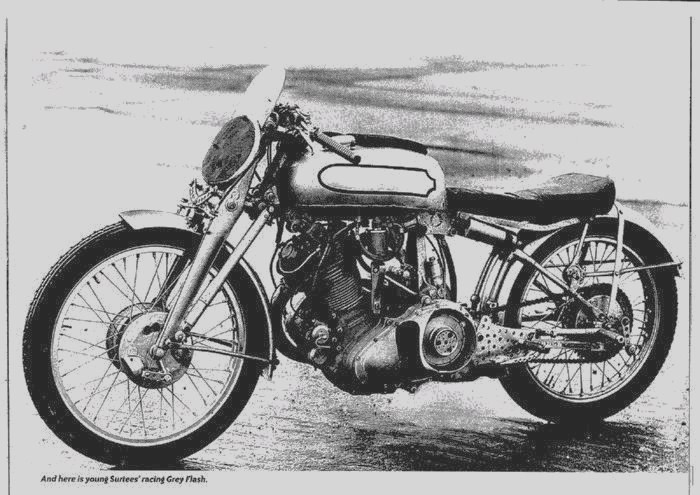

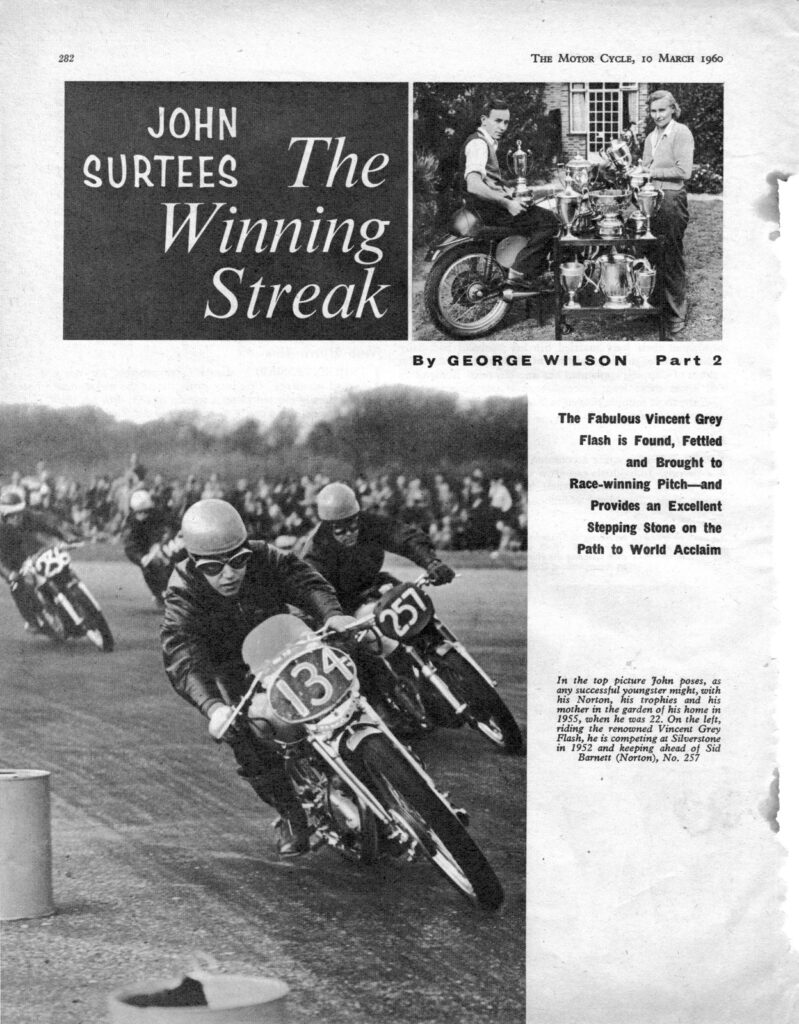

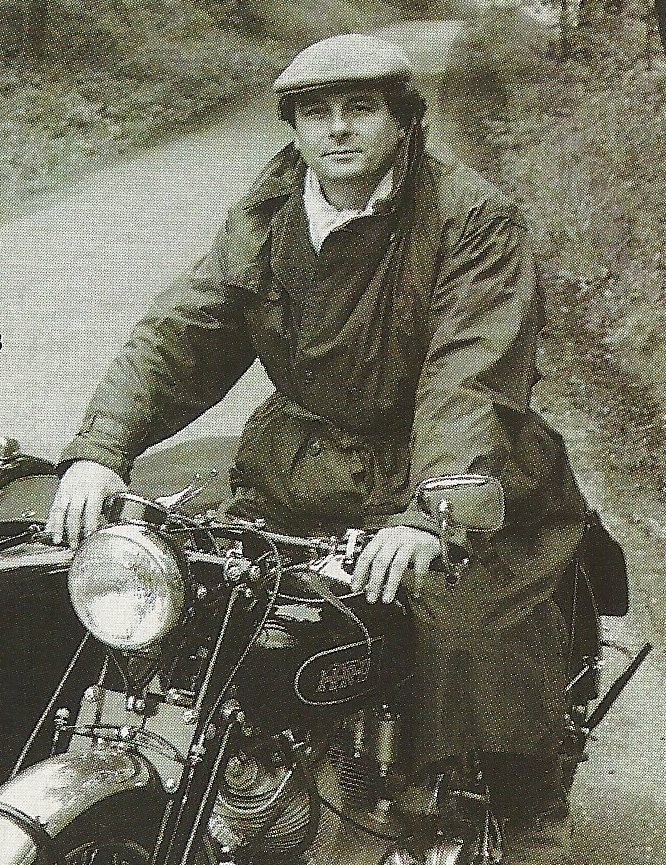

Speed is Expensive director David Lancaster’s interview with one-time Vincent apprentice John Surtees would prove to be one the racer’s last. To mark the release of unseen footage from the award-winning documentary, here is David’s account of meeting the only man to win World Championship titles on both two and four wheels: Surtees won seven motorcycle championships between 1958-60, and one F1 title, in 1964.

The contemporary portraits of John Surtees were taken by Steve Read.

Then, pausing, the blue eyes beginning to water: “And I know Henry would approve, too.”

John Surtees was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul's Church in Lingfield, Surrey, next to his son Henry.

The Speed is Expensive Deluxe edition download package features the full film – plus 50 minutes of extra footage with John Surtees, Jay Leno, plus friends and family of Philip Vincent and Phil Irving. Head to -

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/speeddeluxe

He lectures in journalism at the University of Westminster and is director-producer of SpeedisExpensive. Follow him on Instagram and on Facebook.

Back to Black at Montlhéry

Capturing the story of Philip Vincent’s life on film sees the SpeedisExpensive crew filming at the historic banked circuit in France last year – featuring one of Patrick Godet’s finest creations

By Mike Nicks and David Lancaster

Photography by Bernard Testemale, Mike Nicks, David Lancaster, Steve Read, Philip Vincent-Day and others.

Today’s lock-down on travel and gatherings – this year’s TT was cancelled a couple of weeks back – has cast the calendar of 2019 in a new light. We look back and wonder when fans will be allowed to ride this historic banked circuit again. Or meet at the Rock Store west of LA? Or ride to Box Hill in Surrey… or connect the corners of the Isle of man’s mountain circuit? The sad answer is, we don’t know. So, last year’s Café Racer Festival’s tribute to Frenchman Patrick Godet, who died in 2018, has gained added poignancy. Not only was Godet the doyen of Vincent restorers and special builders, he relished the social side of motorcycling too – founding the French Section of the Vincent Owners Club, hosting its first rallies and during the late 1970s and '80s making the most of the free-wheeling, often unexpected rewards of touring on motorcycles with friends: taking the wrong turn, lunch on the road, repairs on the way. Event organiser Bertrand Bussilet handed the track over to some 70 Godet Vincents, Egli-Vincents and standard bikes which took part in a parade to mark Patrick’s life.

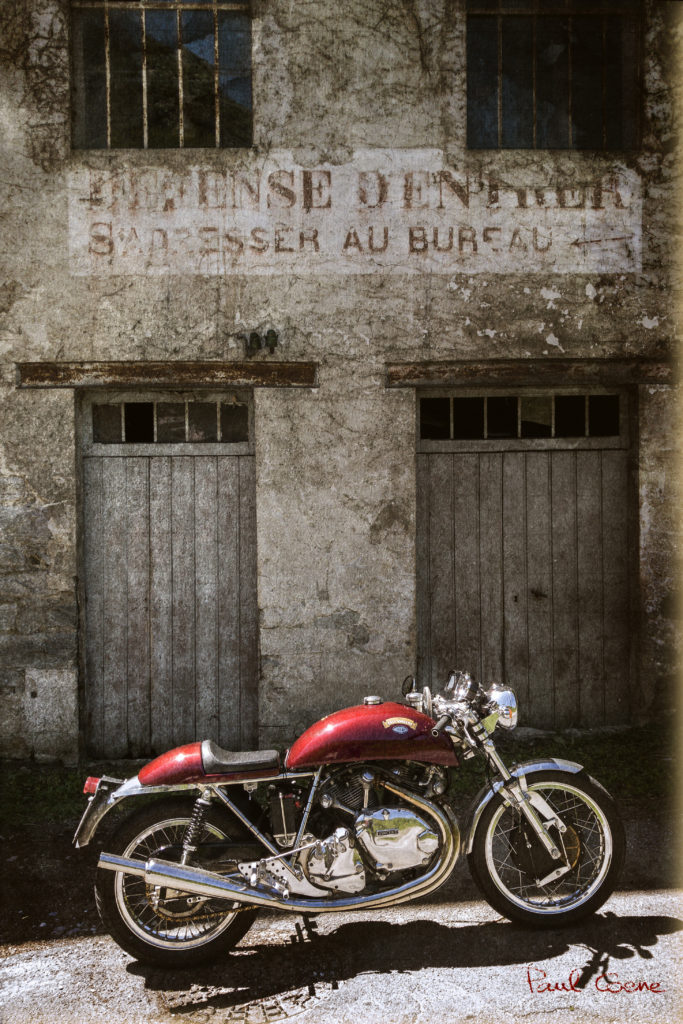

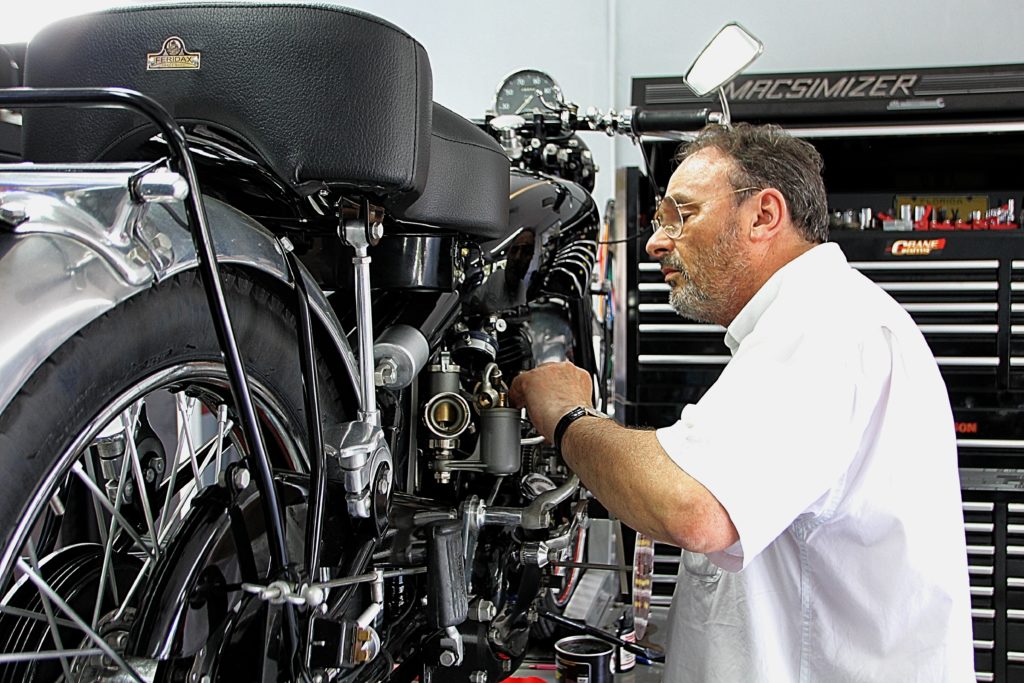

The Godet lineage is continued by workshop chief François Guerin and his team, who are carrying on with restoring Stevenage bikes and building their own Godet Vincents. Patrick was a fan of improving his machines – he was one of the first to fit the Grosset electric starters - but also resolute in his view that the late 1960s bikes which Egli himself produced were the epitome of a Vincent-powered special. He always refused requests to fit disc brakes, or upside down forks or other so-called updates, as other Egli-Vincents wear (and customers asked for). Yet now it is more likely bikes such as Jean Luc Charrier’s stunning Lightning special – which the owner writes about below - will emerge in the coming year or so. It is a bike that breaks rules, bringing together styling cues and components from different eras to a customer’s specification with a stunning result.

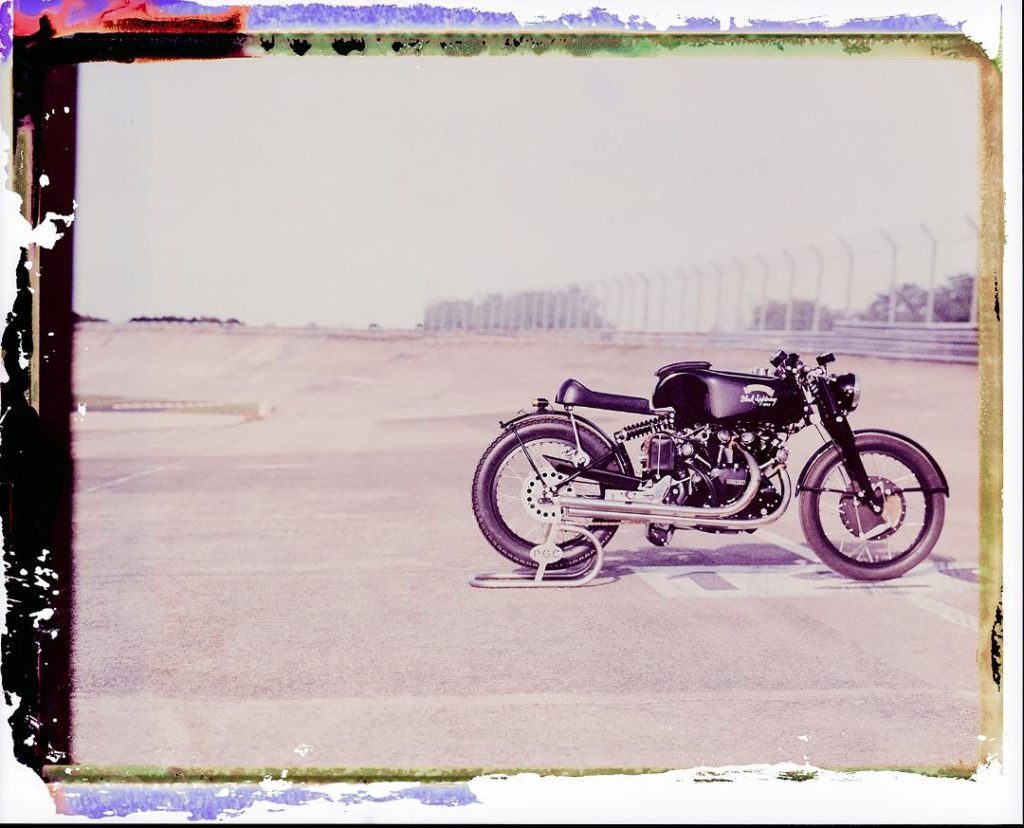

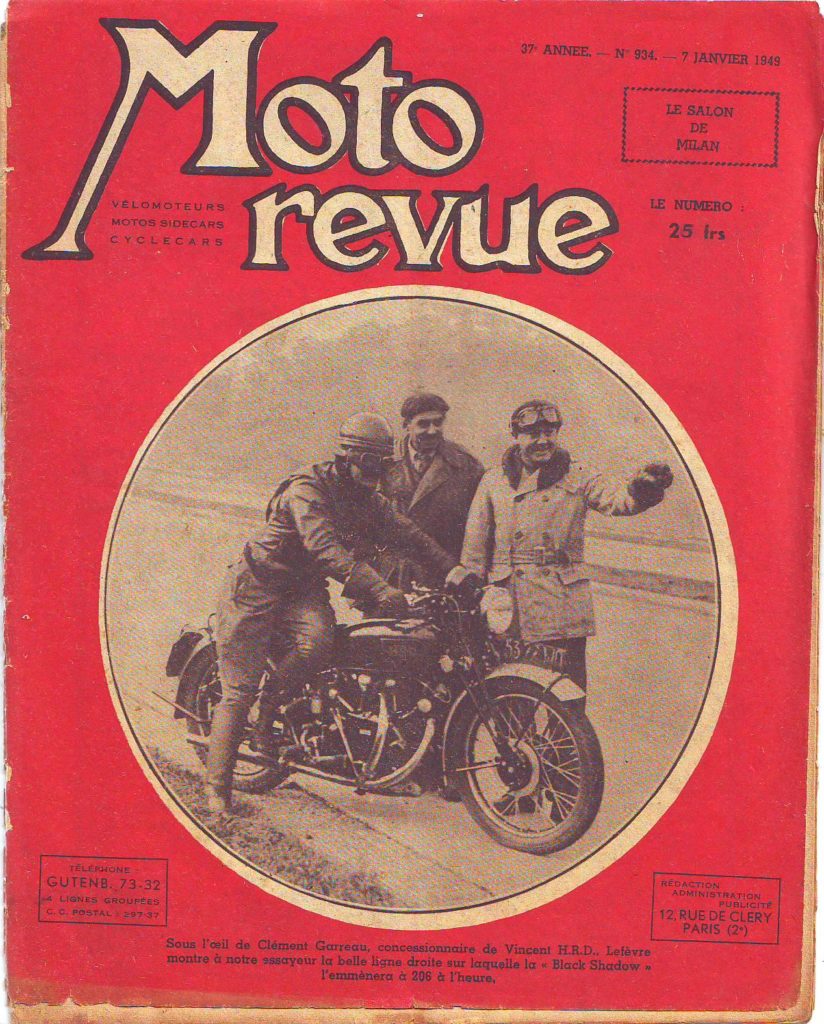

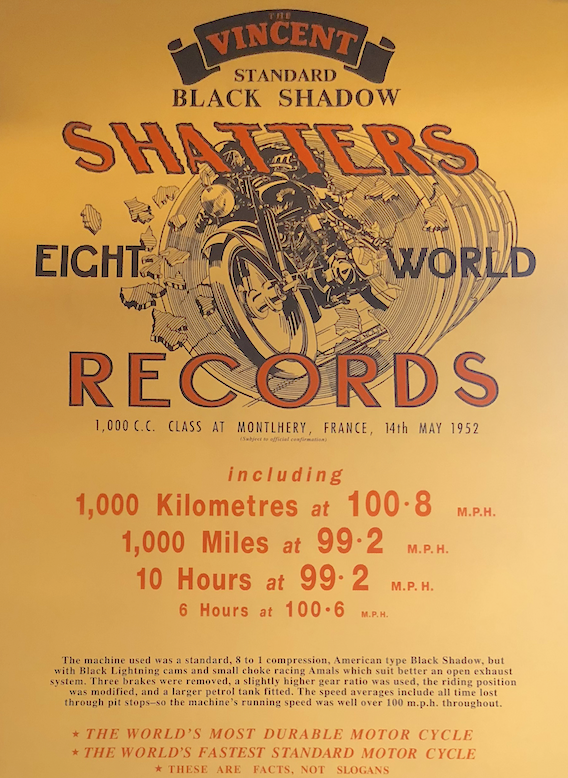

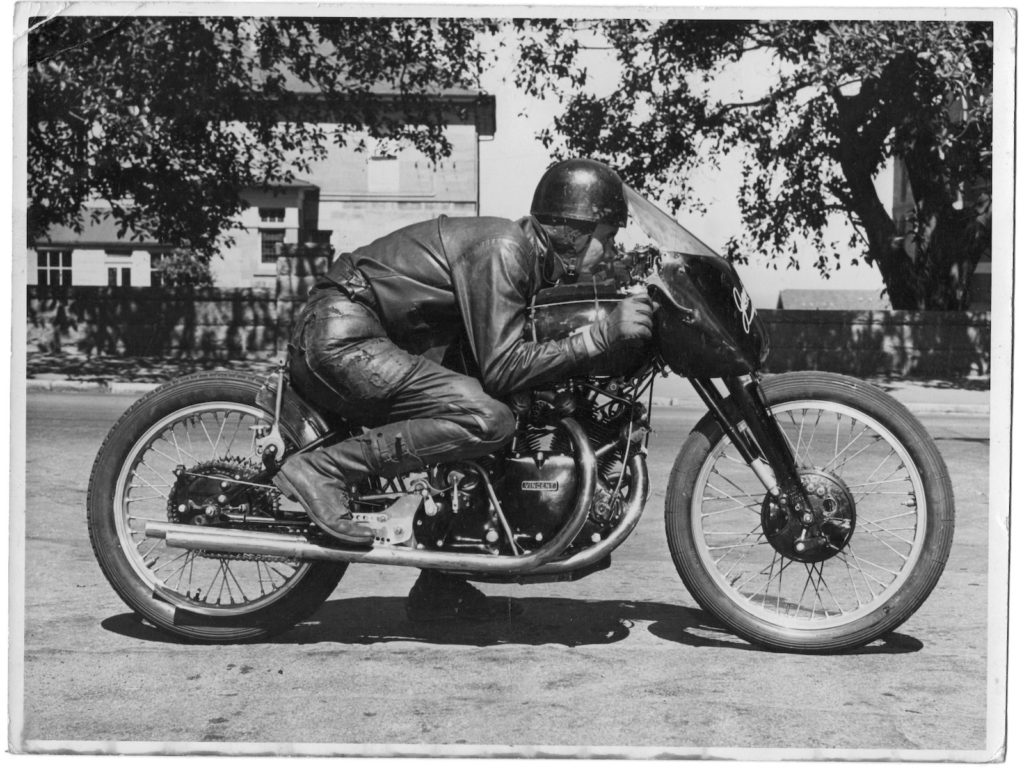

To pay tribute to the 1952 record-breaking runs, director of photography Steve Read and producer/cameraman Gerry Jenkinson filmed two notable bikes on the banking: Jean Luc’s Lightning special and Dominique Malcor’s Series B Black Shadow, the first to be imported to France in 1948 and a machine that was timed by Moto Revue magazine at 208kmh, or 128mph, on the autoroute between St Cloud and St Germain. This was at a time when the fastest bikes made by Triumph, Norton and BSA - 500cc parallel twins - would only reach around 85-90mph. There has probably never been another time in motorcycling history when a new model has so far out-paced the opposition. If the Black Shadow was the ‘world’s fastest standard motorcycle’ – as the company’s advertising claimed – then Malcor’s was the the fastest of the fastest.

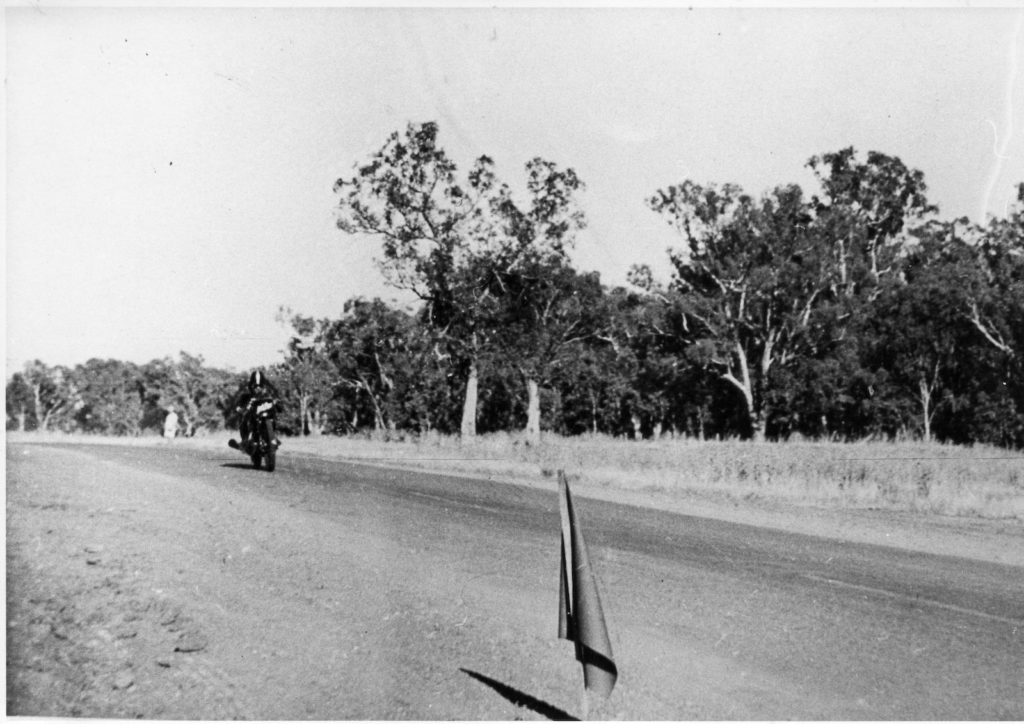

Architect Jean Luc’s ‘Back to Black 1955’ machine is so named because his daughter adores the work of the late Amy Winehouse, whose song Back to Black helped cement her reputation in 2006, and because 1955 was the last year of Vincent production. See below for Jean-Luc’s full description of this fascinating machine. The sequences filmed will form part of our film’s coverage of the records set at the circuit back in 1952 – in many ways a last hurrah for the factory – as it was the final time the firm fully backed racing and record-setting. In addition to these two bikes, filmed with a drone as well conventional panning and tracking, US Producer James Salter captured dramatic footage high on the banking from the sidecar of Australians Bob and Joy Allan’s 1953 Black Shadow/Steib 501 outfit with a Super 8 camera. Go Pros were mounted on several bikes, including fast solo laps by Peter Fox on his own Godet built Lightning Replica.

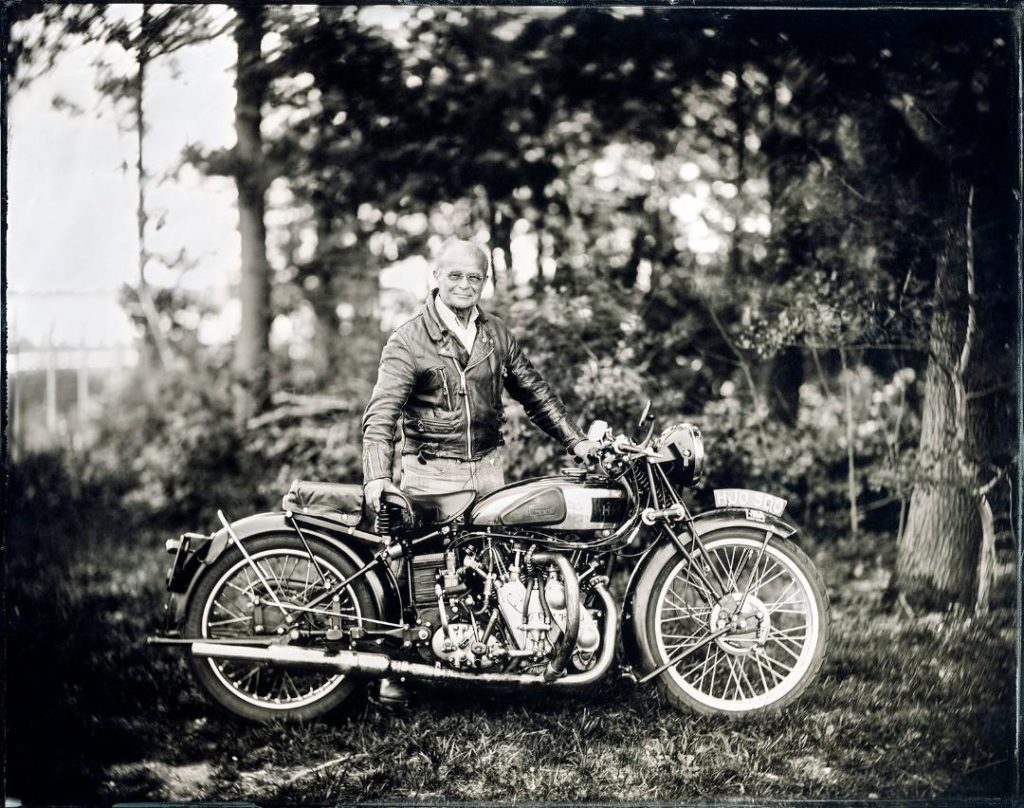

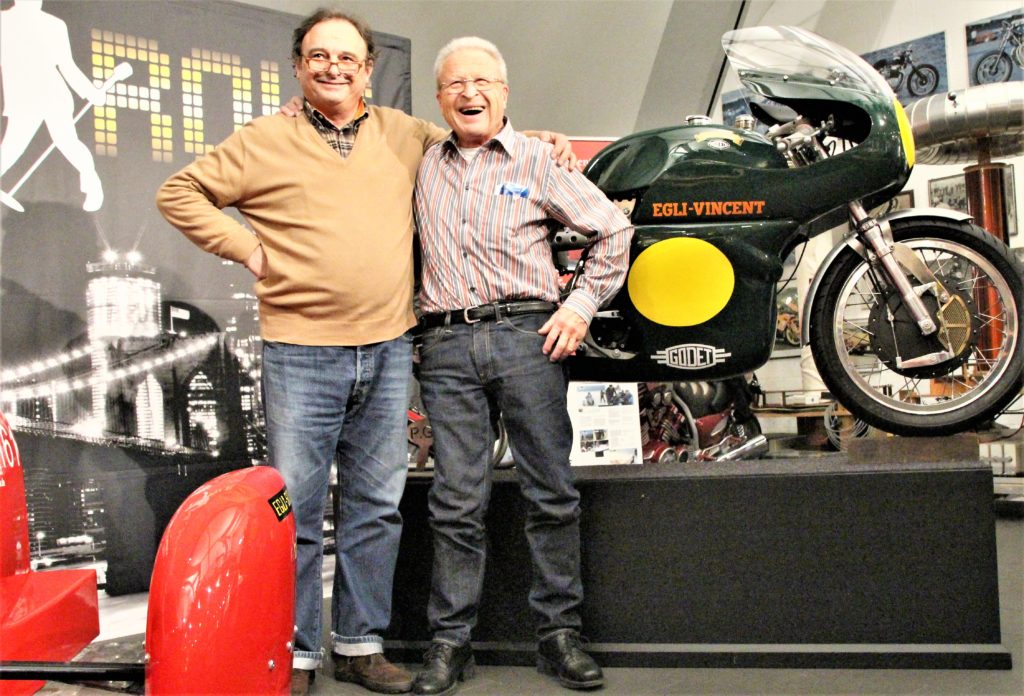

Both brothers are long-term and high-mileage Series A Rapide riders, with great insights into the many highs – and the lows – of racking up thousands of miles on the bikes. A few years back, they shipped their Rapides to the USA and rode them the length of Route 66. Jay Leno got to hear of their journey and welcomed them into his car and motorcycle collection in LA, full of admiration of the brothers’ dedication to ride 80-year old cycles across America. Another friend of our film project was also at work at Montlhéry: Bernard Testemale, an innovative photographer who will be familiar to readers here, and who had set up shop with his wet-plate equipment inside the track. Over the two days of the Café Racer Festival, Bernard captured stunning images of Philip Vincent-Day, Fritz Egli, moto-blogger Evangeline (@lapetitemotorouge), Harvey Bowden with his pre-war Rapide, and others.

SpeedisExpensive has now entered post-production. Transcripts of interviews – with record-setters, factory personnel, family and friends of Vincent and Irving – are being read to begin to map out a structure for the documentary. Philip Vincent’s life was not easy in its final chapters, and it was a life marked by amazing highs but also crushing lows and personal challenges. The aim is to edit the material into a film which anyone, not just petrol-heads, can engage with to bring those high and lows to the screen.

The ‘Back to Black’ Godet-Vincent special

French architect Jean-Luc Charrier describes what inspired his stunning custom Vincent:

"The first time that I saw a Vincent engine was in a joinery near Gras, in the Ardèche region of France, where I was designing furniture. In the corner of the room the workshop chief had some Vincent parts - a frame, an engine, a set of Girdraulic forks and a fuel tank. At first I thought they must have come from a French motorcycle because of the name Vincent. I saw the engine as an aesthetic structure, and I was struck by the design. But they said that it was an English motorcycle that had been the fastest in the world in the 1950s, and I thought that was magnificent. I was about 30 at the time, and I didn’t have the money to buy a Vincent, but that bike stayed in my head. I started buying motorcycle magazines where I could read about Vincents, and I saw an article in the French magazine Cafe Racer on Patrick Godet, who was what we call in France la Pape (Pope) de la Vincent. I was reading the magazine at a motorway service station, and I called Patrick Godet, and said, ‘Monsieur Godet, bonjour, I’m passionate about Vincents, and I would really like to have one.’"

"The parts that I had seen in the joinery were from a Black Shadow Series C. I asked Patrick if he had one for sale, and he said, yes, he had one with a Steib sidecar. With my joiner friend I flew to see him and bought my first Vincent. At first I took the sidecar off and rode the bike as a solo for two or three years. But one day I decided to take my little son to school in the sidecar. Patrick visited my house and showed me how to ride an outfit in a big car park one Sunday, with him sitting in the chair. Then I decided that I wanted a more minimal Vincent, but I didn’t have the skill to restore one. So I sold the sidecar outfit and Patrick built this bike for me, using some of my ideas. For example, I liked the way that Rollie Free streamlined his Girdraulic forks by taping round them for his 150mph speed record at Bonneville in 1948, and I wanted to get that look. So Patrick removed the long spring from the forks and fitted a modern compact one in front of the headstock. The forks now have the shape of those on Rollie’s bike, but where there was tape hiding the spring there is now metal in the same shape. I made the seat and the tank pad myself, in the style of 1950s’ racing motorcycles."

"We arrived at the name of the bike because my daughter, who is a singer herself, loved the music and the sensibility of Amy Winehouse, and she was very upset when Amy died (the song Back to Black was one of her hits). The new generation of technicians and craftsmen at Godet motorcycles are now taking the Vincent legend forward. I am an architect and a designer, so my work, it’s my eye. For me the Vincent engine is magnificent - the way it is suspended from the spine tube, the Girdaulic fork, the tank, the gold lettering on the tank. It’s unique. Monsieur Vincent wanted to create the best motorcycle using the best materials, regardless of the price. The Vincent is the Bugatti of motorcycles. I’m a curious person, and when you’re curious you wonder - why? Why is this motorcycle so mythic, why do people react to it in the way that they do when they see what is really just a mechanical object? The Vincent goes beyond the fact of just being a motorcycle. There are thousands of motorcycles, but there’s only one Vincent."

'SpeedisExpensive': the Australian Shoot Road Trip

[by Philip Vincent-Day]

Web exclusive: To accompany another on-location report from the producers of the Vincent documentary SpeedisExpensive, we’re showcasing the first of a series of short films sponsored by AVON Tyres giving some clues to what will be in the final film.

………………………

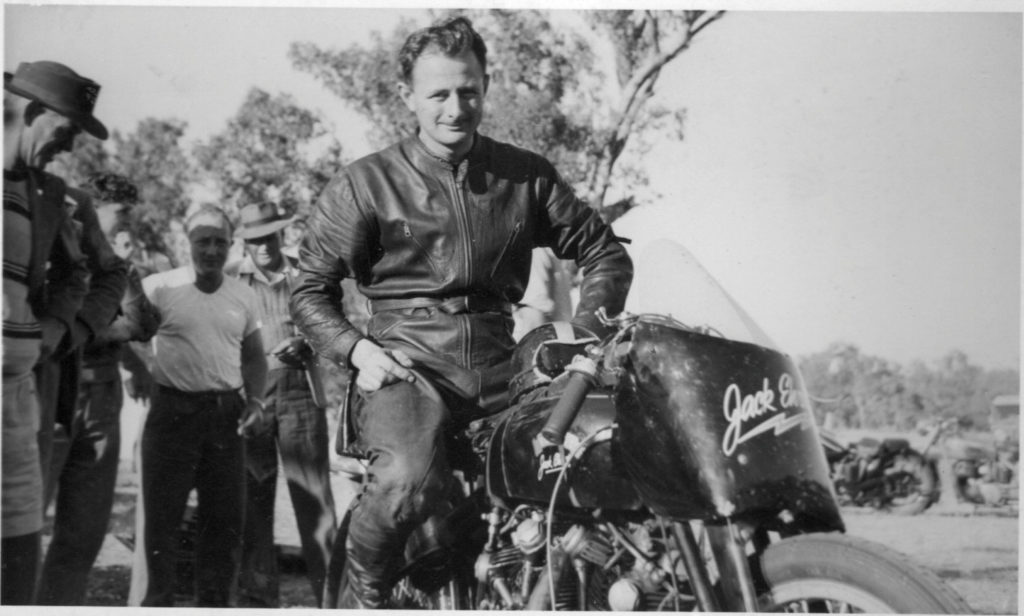

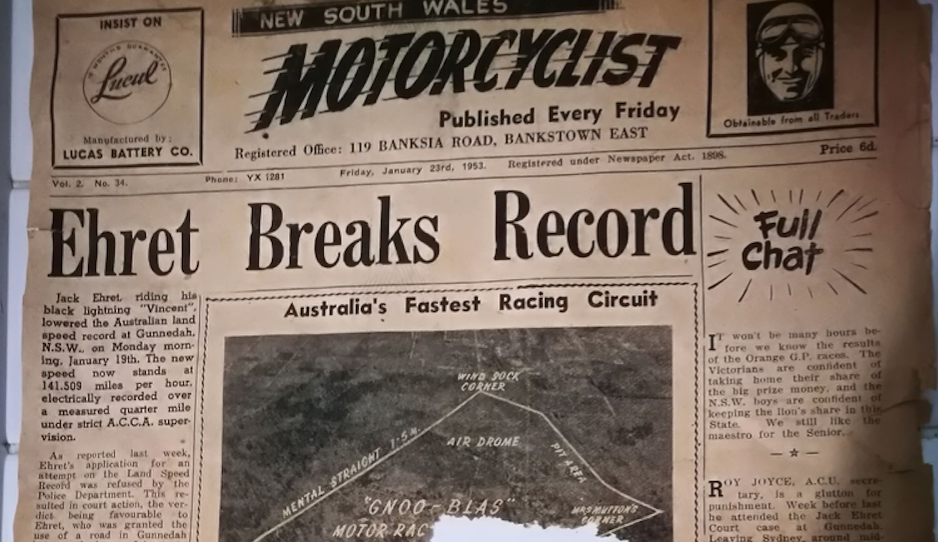

Readers may recall the post from last year in which Mike Nicks detailed our filming in and around LA (https://thevintagent.com/2018/11/03/speedisexpensive-the-la-shoot-road-trip/). We hooked up with Jay Leno to talk Vincents and reunited Marty Dickerson with his record-setting Blue Bike. In April, we embarked on another major trip: this time crossing the world to capture some of the most exciting Vincents in Australia and meet key figures in the story of my grandfather and his machines down under.

Was I mad? Did I need to do this?

Patrick Godet Remembered

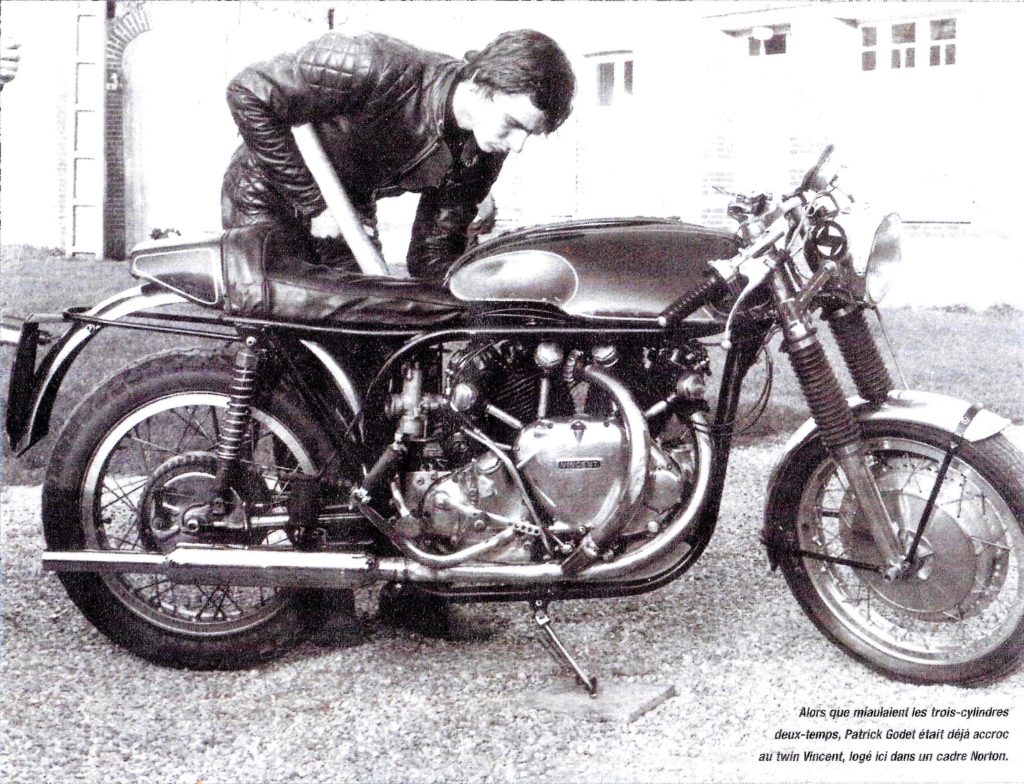

He was a bear of a man, whose fanatical love for Vincent motorcycles lasted over 40 years, and developed to the point of manufacturing the amazing Godet-Egli-Vincent specials for which he became famous. At his small factory in Malaunay, just outside Rouen in Normandy, Godet built over 250 of his beautiful Vincent specials, and repaired/restored countless original Vincents and engines for owners around the world, with incredibly high standards. The Godet Vincent reproduction engine could be ordered up to 1330cc, with double the horsepower of the original, and was built to a higher standard to cure many of the known faults of the 1940s design.

Patrick was passionate about all Vincents. He first learned of our Egli special chassis from our successes with Fritz Peier and Florian Bürki, racing on British circuits. Soon, Patrick serviced Egli-Vincents in his Malaunay workshop; these were early machines delivered to French customers. He was very pleased with the handling, with the weight saving and soon a commercial cooperation started. Patrick became our French distributor for the Egli-Vincent chassis.

I finish with some of the words I said at Patrick’s funeral service:

‘Your decision was strong and brave, as you were. I was shocked. All our friends were shocked. Then we learned the brutal facts and we understood and accepted it. Patrick, sometime, somewhere in the universe we will re-unite: there will be no pressing burdens, no speed limits. Farewell my dear friend. We will meet again, with our Vincents, and we will release the clutch, and open the throttle.’

I was lucky enough to meet Patrick about twelve years ago when an old friend, Peter Fox, suggested we ride down together to Malaunay on Peter’s Godet Egli Vincent and the Ducati 750SS I owned back then. The Egli was going home to Patrick for its first service. We arrived quite damp after a good fast haul down the A16 from Calais. Patrick looked over the Ducati and said: ‘if you like café racer - you must try mine’. It was the first of several trips in Springtime, sometimes by van, to bring back or collect a bike. Usually we spent day or so looking at the latest developments in the works, followed by an excellent dinner with Patrick in Rouen or nearby.

We are all so sad to lose him. Patrick was one of those rare people with the enthusiasm to enhance other peoples’ lives - ‘a true keeper of the flame’, a passionate and skillful designer and engineer, and a lovely guy.

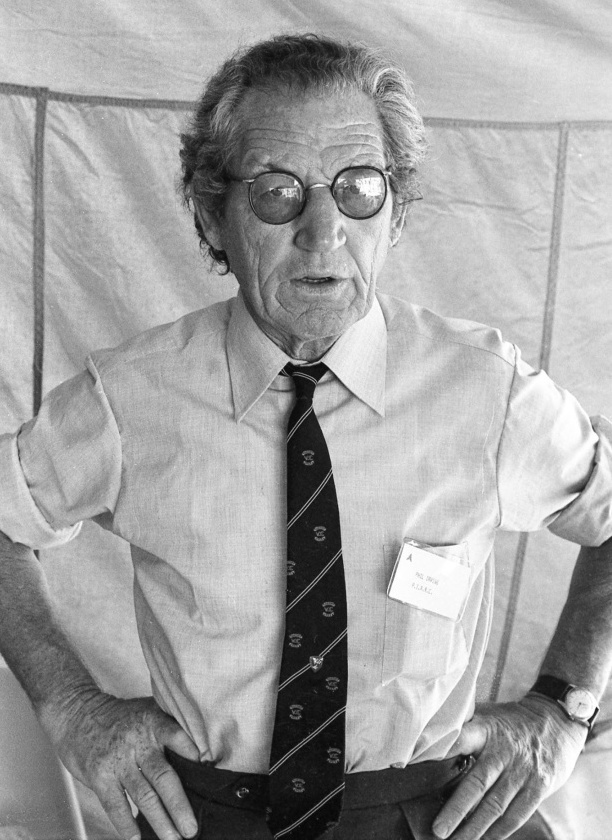

'Small Library Burns Down In Normandy'

Patrick Godet became friends with my parents in the early '70s, although in terms of age he was closer to my brother and me. He stayed with us often in London usually to attend Vincent Owners' Club (VOC) events. I remember teaching him to play cricket as a youngster. He would always remind me of this. Patrick's mind was a 'sponge' for anything Vincent-related even then, picking the brains of survivors such as Phil Irving, Eddie Stevens, PCV himself, even Rollie Free at the North American Rally in '77. He returned home to set up the Section de France and unearthed the original French importer of the marque. Patrick grilled M.Garron about any remaining bikes or parts that he knew of.

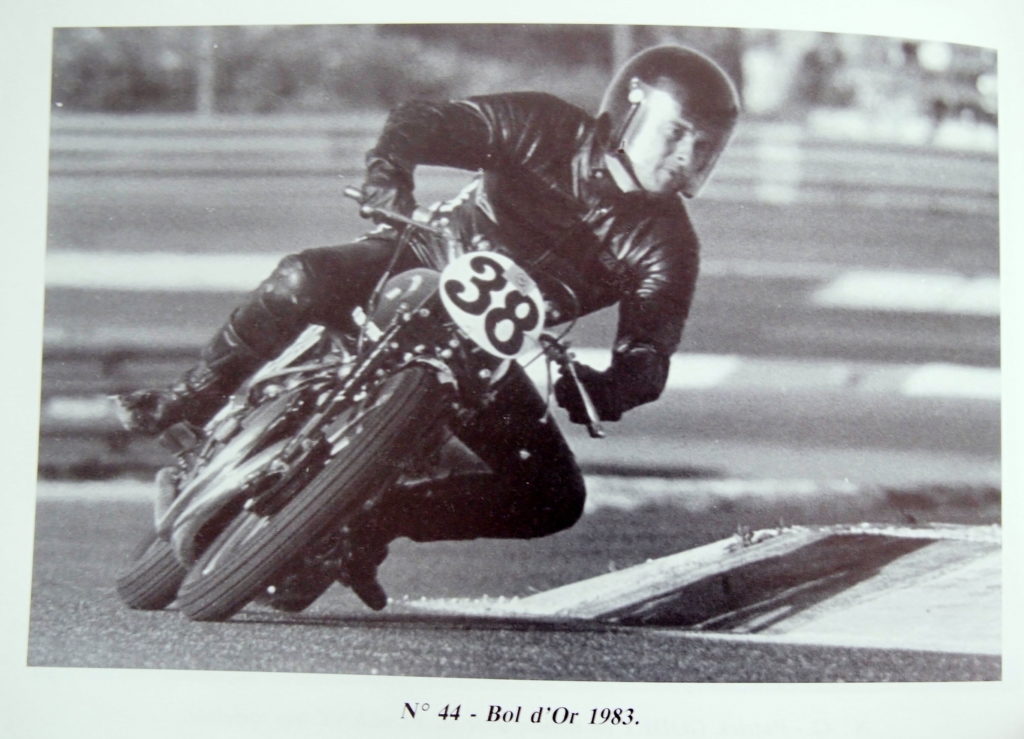

Dad and I rode to Patrick's first French Section Rally. His family in Normandy seemed rather grand with a chateau and a haulage firm to pay for it. His brother was a fine artist in oils I recall. By the mid '80s, I was working for Mark Williams of Bike magazine fame. Patrick was racing then and converting old Comets to Grey Flash spec (somewhat controversially). Editor Rick Kemp and I covered all this happily as Godet and his projects were always good copy. Patrick's step-son was staying with me in London and Patrick came to visit us in a client's Aston Martin DB6. So things were going smoothly.

There was some sadness in Patrick's personal life, although he lived what always seemed the most enviable and worldly bachelor lifestyle. He was a product of les trente glorieuses and it may be that a sense of entitlement was part of the configuration, but his charm and seeming innocence remained effortless and natural. He could light up a pub, bikers' beer tent or any haute brasserie. That changed after Sylvie died three years ago. Patrick was devastated. But he remained unfailingly kind and hospitable to me and my family. It felt like he would always be there for advice and a chat. A ride through Rouen will not be the same without stopping for lunch with Patrick. I can't tell you how much I will miss him.

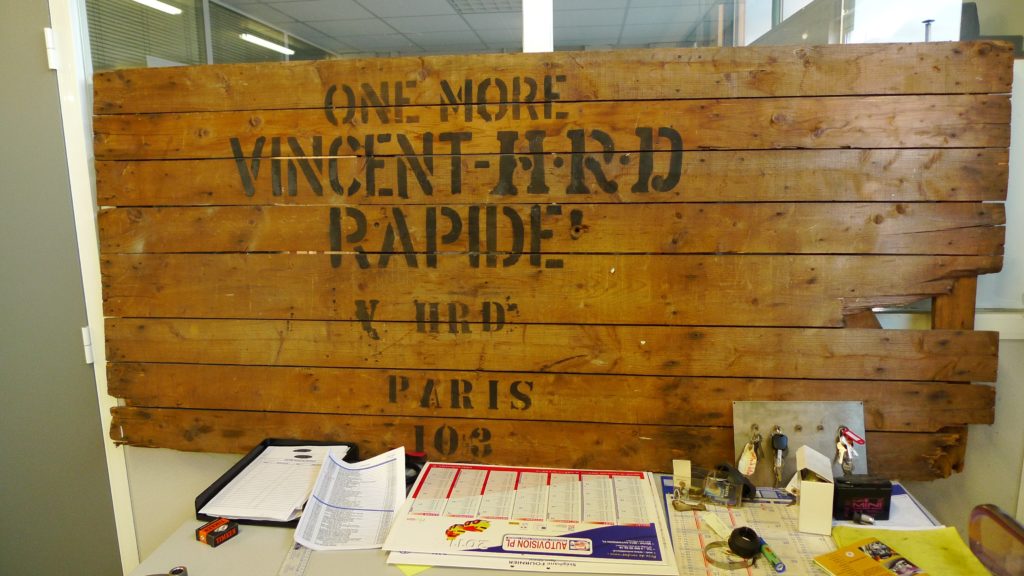

In 1991 Argentina lifted restrictions on the export of its 'national treasures'. These included some 800 Vincent HRDs imported from 1946 to 1950 when the going was good there (not so good in England). The first production Lightning, first Series C Shadow and other glories were said to be among them. Most, in fact, were destined for the Federal Police and Peron's Presidential Guard, plus a few ''playboys'' who would ''tit up and down the Avenida 9 de Julio'' (my translation, from memory).

Patrick and I had spoken of these bikes when I lived in Paris. We would sometimes retourner le monde into the small hours. But we were not alone. The Argentine Vins had been legendary - like a lost tribe - so there was a bit of a gold rush on. I had picked up some colloquial Spanish in a muralist brigade in Chile in earlier years, so I mugged up on my Series B parts list and eargerly took up Patrick's invitation to go big Vin-hunting with him in the Argentine. I read all I could find in the house journal of the VOC going back decades, and consulted a couple of old hands: WW2 veteran Jack Barker and USAF pilot Alex Nofsger had both been down and come away empty handed pre-embargo days.

Loaded with 19'' B spec. sports mudguards - which Patrick rightly guessed would be suitable bargaining chips - I arrived at Buenos Aires airport where Patrick failed to turn up. First visit was to the offices of the original Vincent importers, Cemic, with colonial blinds and ceiling fans as I recall. Everything and everyone seemed to be from 'central casting'. Then it was mostly gum shoe/barn find stuff: asking around at old garages, flea-pits, bars etc. As always, Patrick seemed to fit in wherever we went, even without any Spanish. We set ourselves a limit of one thousand pounds sterling per twin. This meant turning down some real lovelies when, out in the pampas grass, a gaucho-type would dust off a copy of the Classic Bike buyer's guide, much to our dismay. The state of the bikes, however, was usually dire. They'd not been run for decades and there were hardly any matching numbers, or often even numbers at all.

In 1950 el Presidente had imposed severe restrictions on imports. Phillip Vincent himself was Anglo-Argentine - we met his sister in Buenos Aires - and close to a quarter of his twins had been exported there. But not even the most basic spares could subsequently get through without bribery or major hassle. Patrick and I were continually amazed - and genuinely impressed - by the subsequent historic adaptations employed to keep these things on the road. Everything, from chain links to servo-clutch parts, had been hand-machined, often evidently to increase horsepower. We were initially puzzled by the widespread gaffer-taping of girder forks to look like the more up-to-date Series C Girdraulics, but accepted this as a 'streamlining' vogue. Hmm. We bagged about a dozen 'complete' bikes and enough spares to help fill up a shipping container. Without the Godet garage and expertise, however, I am not sure that it would have been worth it. Patrick's passion was for the marque, and with him is lost a lifetime of expertise and magic. And a rare old friend.

Back in the 1960s on family holidays we visited Fritz's workshops when he was building his Egli prototypes, mostly with Series B engines. Looking back now, I wonder what Patrick had had in mind for all those Argentine B Rapide lumps with near-useless cycle parts.

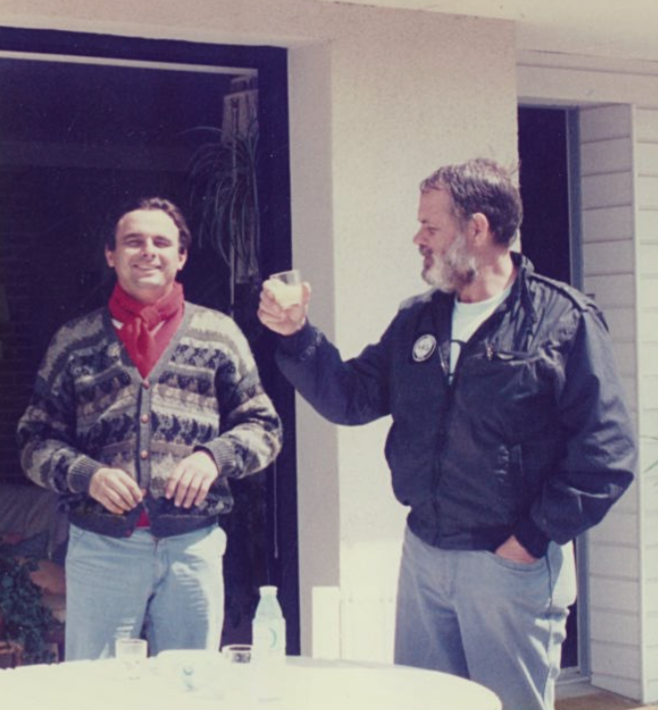

During the 1970s and '80s, I regularly spent summers in Europe riding my Vincent. I met Patrick in 1976, at the first French section VOC rally in Normandy which he organised, riding there with Alan Lancaster and Bryan Philips. In many ways, this set the pattern for many miles and adventures with him: we got lost in the fog off the boat in Dieppe, and came across the rally site by chance.

We took in the sights of his home town, met some girls, and it dawned on me this man was the King of Rouen. His family ran a transport business and soon I was working on Renault diesel engines there. In the evenings I would return to his home – on Rue de Vincent – where sumptuous meals would appear from one of his female friends. The foreman at the family firm, a wonderful man called Henry, saved Patrick’s ass too many times to count. It was a magical time. His cellar was full of Vincent spares and due to his ability there was a never a broken Vincent there for long.

He visited me often in Maryland, helping me build up a Comet from a basket case, which is still racing around in Class C. He was generous beyond belief.

I was saddened to hear of the death of Patrick Godet. Patrick contributed greatly towards keeping the Vincent name alive. His work in restoring Vincents was exemplary, creating demand from many Vincent owners including my son. His Godet racing team competed on Vincents at many veteran events including the Isle of Man Classic TT and Spa-Francorchamps. His contribution to motorcycling was boundless. He will be missed by many.

I can remember the first time I met Patrick. Or at least the first time that I could remember meeting Patrick. I was at a VOC international rally, about 15 or 16 years old, having received notice the rally was taking place in Essex close to where I was living at the time. I was sat chatting with Bryan Phillips when two Frenchmen approached. Before Bryan could introduce us, Patrick already knew who I was - I wasn't quite sure how. I must admit that at that moment I had no idea who he was, and found it odd that I hadn't had to be introduced.

Sandra Gillard (friend and photographer):

In 2012, I wrote an e-mail to Patrick asking about photographing a Vincent. With this simple question, I went in August 2013 to his workshop to shoot the jewels he created and restored. Within a day, I had ridden an Egli-Vincent-Godet 1330 for the first time in my life. From there, I dreamed, travelled and rode with Patrick and his Vincent. Together, for the next five years, we began to write a page of a story that belongs to us. Patrick often told me I was his bench he could rest on.

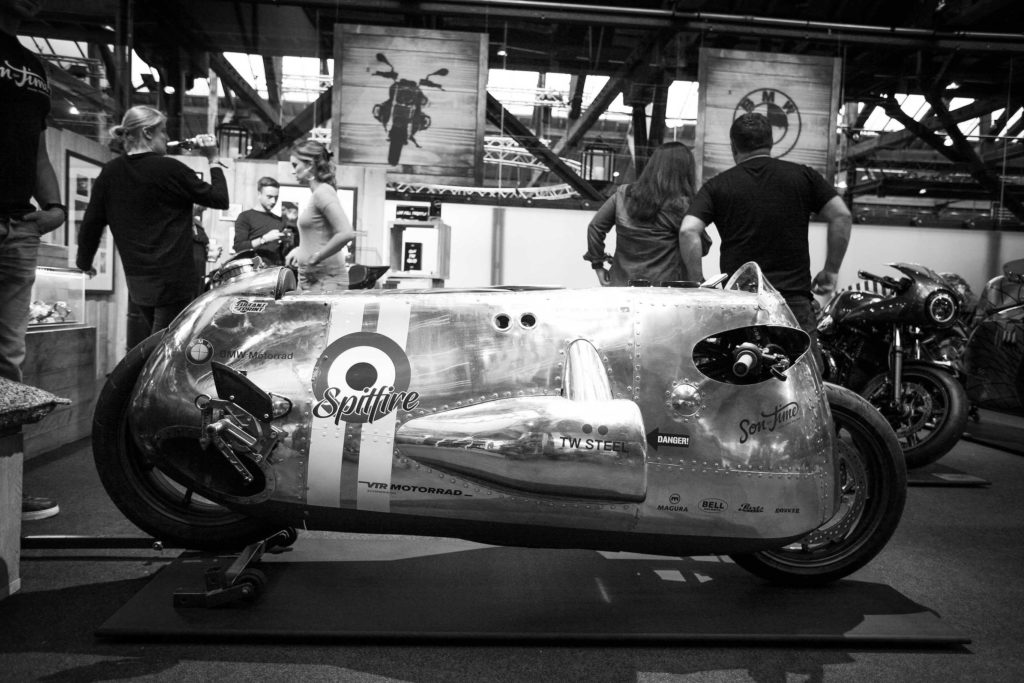

2018 London Bike Shed Show

Special to The Vintagent by David Lancaster

Great cities are marked by great contrasts. I can’t have been the only one riding between two major events last weekend, picking through hot London traffic, who was struck by how far apart they were. The more famous, and much older, is the Chelsea Flower Show – which every May sees the A-list, B-list and green-fingered descend in blazers and other finery to marvel at the innovation, skill, devotion and colour on show. And just a few miles to the east, a very different crowd descends to the Bike Shed London event to marvel – yes, you’ve guessed - at the innovation, skill, devotion and colour on show. But far as I know, the Chelsea Flower Show is yet to host tattoo parlours, panel bashing or beard trimming on site. Maybe next year. [There's hope! - pd'o]

Royal Enfield-based special the R10 [Dave Norvinbike]