'A Novel and Sure Method of Suicide' - Henri Fournier

Henri Fournier’s ‘Infernal Machines’

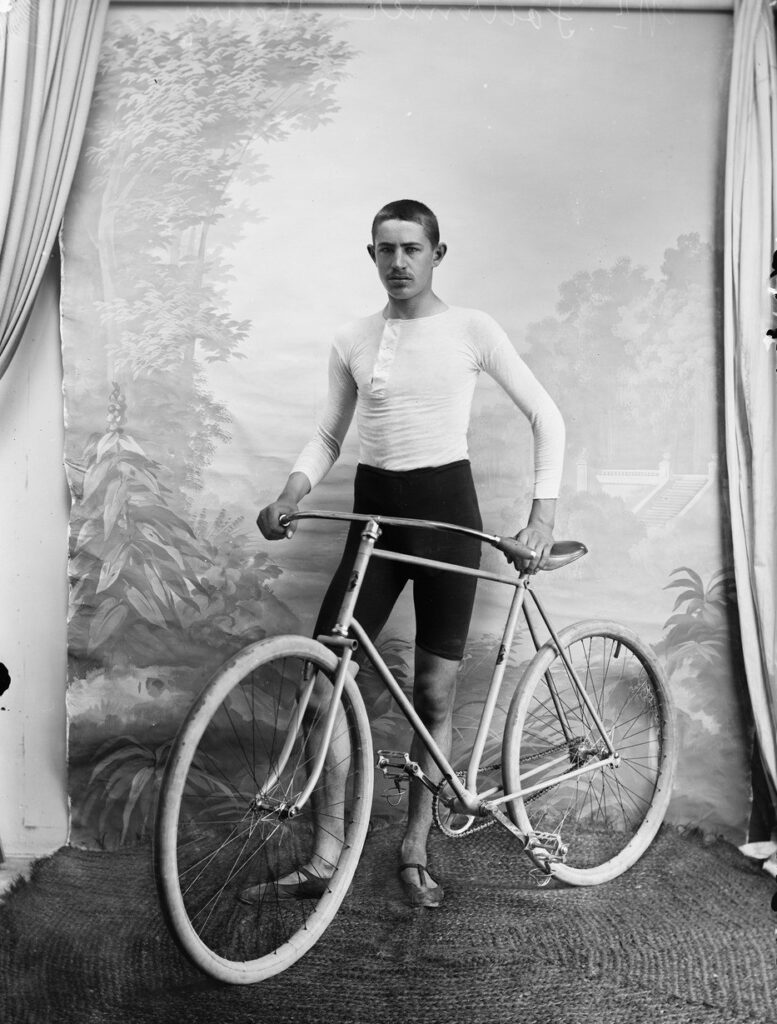

On a cold winter day, in November 1898, a man was riding a motor bicycle on Fifth Avenue, New York. This may seem like a bland statement today, but in the Big Apple of then, the fastest way to travel was by bicycle or horse and cart; motorized transport was never seen. On seeing this unusual contraption traveling at a fast pace, a policeman tried to stop the rider, but had to give chase. On seeing the policeman, the motor cyclist ‘supposed the policeman wanted a race, and putting on about 25 miles speed, left the policeman behind at once.’(1) Unable to keep up, the lawman tracked the felon to his hotel where he was arrested; the machine was confiscated though the suspect released. The ‘criminal’s’ name was Henri Fournier, a Frenchman who had recently arrived in New York with various petroleum-powered machines.

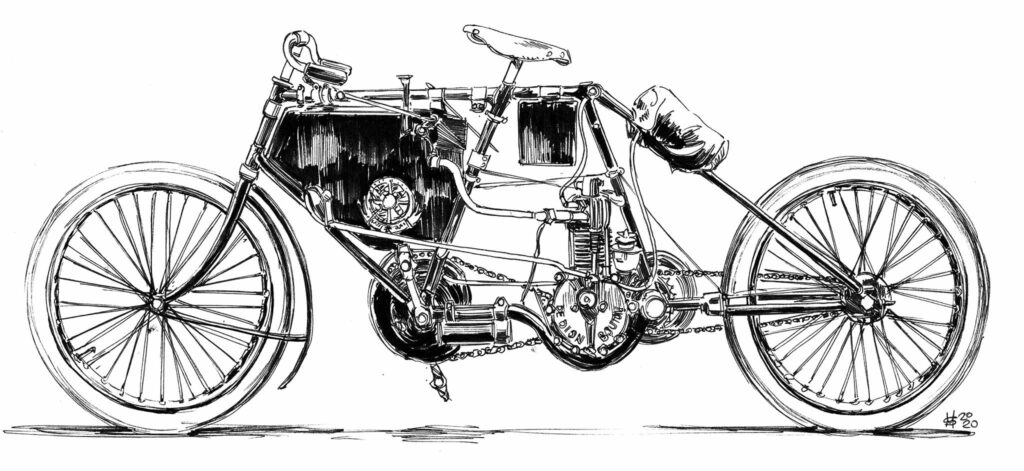

With this background in engineering and cycle sport, it’s no wonder Henri took to the invention of the motorcycle with vigour. One early account of Fournier on a motorcycle was made by Charles Jarrott (a British sporting gentleman deserving his own article), who in the spring of 1897 was walking through the Bois de Boulogne, a large public park on the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, and when he saw Henri flying along the road mounted on a motor bicycle. The machine was of an unusual length with the rear wheel extending ‘four or five feet behind the rider’. (2) Jarrott was so taken with the machine that he tracked Fournier down and bought the machine from him; he would later use this ‘sporty’ machine on the road, and on the cycle tracks of London.

A year after Fournier sold Jarrott the motor bicycle, he was in New York actively riding and promoting his machines in his flamboyant manner. Fournier’s antics on his motor tricycle were well-known due to an article published in American newspapers in September 1898. The article discussed how Fournier had reached 40 kilometers per hour on this new motorized machine. The writer's tone emphasized the dangers of this emerging technology: ‘His performance suggests the grave danger that would accompany trips such as his on a road where similar machines are dashing along. Fournier alone on a level, smooth road, with no one to kill but himself, and no machine to smash but his own, is a sight sufficiently thrilling. Multiply the sight by 10 and imagine that number of Fourniers mounted on flying automobile tricycles, and the spectator cannot help thinking that this would make a novel and sure method of suicide.’(3)

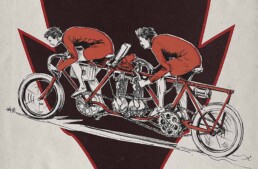

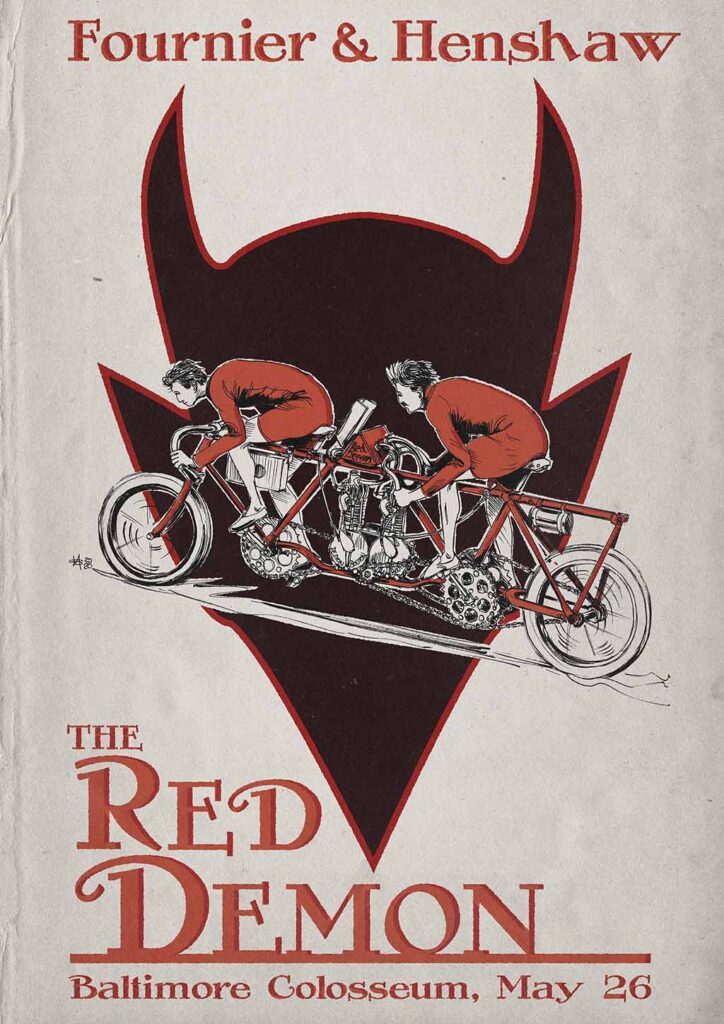

From publications of the time it is clear that Fournier was very active in not only promoting his machines but demonstrating their potential on the track. Often, events with paced matches would also include a solo run by Fournier as part of the program. This would not only thrill the audience but also demonstrate that his machines were not a joke. It was also a chance for Fournier to put the machine through its paces at top speed and possibly set records. All this helped with promotion and development with what became known as Fournier’s ‘infernal machine’ by the press. Initially, Fournier had his tricycle and possibly a motorcycle, as mentioned previously it was later reported that Fournier shipped in two motor-pacing tandems, which arrived on November 21 via the steamship Normandie, just in time to be prepared for their debut at Madison Square Garden on December 5th. The 10 lap to the mile track at Madison was host to a huge meeting on December 5th word had got round that Fournier was to demonstrate his machines both solo and in an hour paced match between Edouard Taylore and Harry Elkes.

When Fournier mounted his ‘cumbersome machine’ the crowd was quick to cry out ‘choo-choo’ and ‘ting-a-ling’ as they found the sight of this strange machine something akin to a toy train due to the noise of the engine. Once the machine was up to speed and Eddie McDufee was in tow, the team reeled off an exhibition mile in just over two minutes. With the thrill of this new spectacle, the audience let out cheers of excitement. Fournier had demonstrated that this new technology, both in speed and excitement, was a perfect combination for a spectator sport such as track racing.

Fournier’s machine was still met with condescending howls as he came out onto the track, though as the participants got up to speed and Eaton and Elkes rode up behind their respective pace machines, the contest was most certainly on. In these races, the different teams start at opposite sides of the track, to make for a safe start and encourage a chase on the banked track. The initial pace was fast, with Elkes taking the lead, the second mile ridden in 1 min 57 seconds. By the third mile, Fournier was finally gaining on Elkes when the drive belt slipped, putting Fournier’s pacer out of action. Tandem teams were sent out to bring Eaton and Goodman through the rest of the race, but with the upset it was impossible to catch Elkes, who won by one mile and completed 20 miles in 41 minutes 41 seconds.

This was a small win for the human pace teams but this event was extremely important historically as it may have been a disappointment for Fournier, but this spectacle was witnessed by Oscar Hedstrom, who was competing in the professional matches that evening. Hedstrom at the time was making bicycles and competing, and would go on to form a partnership with George Hendee to produce the first Indian motocycle only three years later. One imagines that on seeing Fournier at Madison Square Gardens, the mechanically-minded Hedstrom would have been very interested in the possibilities of this new technology. Some have said that on seeing this pacing machine he saw the potential and the opportunity to better the Frenchman by producing his own pace machine. However, as far as my research has gone, this is just an assumption due to them both being at ‘the Garden’ on that night.

The proving ground of Fournier’s pacers would be in the middle distance events. One such match was at San Jose, California, on March 6. Fournier paced Orlando Stevens in a 10-mile match against Harry Gibson, who was paced by two triplets and three tandems in succession. Stevens beat Gibson by one and three quarter laps on the third of a mile track. Fournier didn’t miss an opportunity to demonstrate the speed achievable by his pacing machine, so, with Tom Barnaby steering, they achieved a 1 minute 35 second mile at the same meeting. The machine was pedal-assisted and Fournier believed they could achieve a 1 minute 30 second mile. Fournier’s activity on the East and West Coasts of the USA, along with developments in France, stirred the cycling press to discuss the future potential of motors… ‘If his motor pacing proves enough of a success early in the season to establish it as a feature or the solution of the middle distance game here, either more machines will be imported or our American makers will turn them out a home without much delay.’(5)

The tracks that were available at the time were designed to accommodate the speed of pedal power, not the increased potential of motor cycles. It wasn’t long before new tracks were being built in order to accommodate these higher speeds. One such track was the Baltimore Colosseum, which had its opening on May 26 1899. The event was very well attended, with 5000 people crowding the seating, possibly beyond its intended capacity. The colosseum had the steepest banking of any of the tracks built by Jack Prince, a racer promoter and track builder.

At this time, Fournier was the only person with a motorised pace machine for hire, though this was to about to change. American concern Waltham Manufacturing (builders of Orient bicycles) were now building their own pacing tandems and these machines used the De Dion Bouton engine with their own frames. Ten days after pacing with Fournier in New York, on May 30 Harry Elkes was riding an exhibition five miles in the slipstream of an Orient motor tandem at the Waltham track, Massachusetts. This was not a record attempt but a chance for the Orient pacer to be demonstrated with one of the best middle distance riders of the time. The ride was successful and proved to the press that Waltham could build a competent machine and, as a result, Fournier risked losing his monopoly.

On top of American petroleum tandems being built, there were also reports of racers such as Charles W. Miller, Edouard Taylore and Tom Linton importing machines for their own use and to rent. Within the same report it is stated that Fournier was now working with Tribune bicycles who were providing triplets made ‘to fit the French motors he intends to import to America.’

‘The Waltham machines that Elkes will ride behind will have the same motor as is fitted to Fournier’s machines, the De Dion, so that other things being equal, the victory will lie with the motor engineer, with him who is the better judge of pace and can regulate it more judiciously for his follower. But we Yankees are quick to learn a new game, and weeks of practice at Waltham will teach the pilots of Elkes a great deal.’7

After the Orient exhibition ride at the end of May, Fournier and Henshaw travelled to Waltham to pace Gardiner against Elkes in a 20 mile match. Elkes had two Orient Tandems and a human quad team as backup. The match was back and forth, with Gardnier showing great form behind Fournier. Elkes kept pace but the Orient machine tended to jump, causing Elkes to lose confidence. A series of punctures on both sides caused issues, but with Fournier only having one petroleum machine, Gardiner was forced to ride up behind Elkes, while Fournier found an alternative. He apprehended a triplet from the sidelines, with an amateur in the middle seat. It was not long before the amateur ‘objected to the kidnapping and dismounted on the fly.’ For the last mile a human quad came out to bring Gardiner home, but he was too far behind to catch Elkes, who finished the 20 miles in 37 minutes and 3 seconds.

‘Fournier says that although the French people undoubtedly build the best gasoline motors, we are many years ahead of them in the construction and design of our frames and running gear. He is of the opinion that the American motor tandems which were used in the Elkes race are just as strong and much faster than the French machines, though weighing only one-fourth as much.’8

We will finish this part of Fournier’s story with a high speed event at the Manhattan beach track on September 4, where pacing tandems were run in their own race. It was a 25 mile race with five teams competing for a prize of $500. Four teams were riding Orient tandems, with Caldwell and Judge riding a Jailu & Co. machine. Without the concerns of pacing a cyclist, the participants could run at a fast pace. Previous reports would have had the audience thinking that this was a pretty even match with most of the machines from the same manufacturer, but the twist was that it was the Jailu & Co. machine that led whole the race, while the others struggled amongst themselves. It was stated that the Jailu & Co. had its motor muffled and sped along silently with no ‘clickety-click’9. The superior speed attained was laid to a more perfect form of carburettor than those employed on the American machines.’ It is interesting to read that it was possibly the carburetion that was the deciding factor. There is a certain amount of irony that Fournier came to America with advanced knowledge and having been in America for nearly a year, he had possibly been isolated somewhat from French developments in tuning due to his immersion in the American industry.

Fournier would go on to continue his pacing activities until he moved on to racing automobiles in 1902, when he joined the Mors racing team in France. In his first year, he won both the Paris-Bordeuax and Paris to Berlin races, and he would also return to America to set a new mile record with his automobile. Fournier was a born racer competing from a young age all the way up to the age of 31 in 1902 when he set a new land speed record of 123km/h. All these are great achievements but his adventures in America between 1898 and 1899 must not be forgotten as they were hugely influential in kickstarting the world of motorcycle racing, especially on banked tracks.

1: The Cycle Age and Trade Review volume 22 p26 (Smithsonian Library)

2: Ten Years of Motors and Motoring, Charles Jarrott (1906, London, Grant Richards)

3: The San Fransisco Call September 4, 1898

4: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 22 p460 (Smithsonian Library)

5: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 22 p774 (Smithsonian Library)

6: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p120 (Smithsonian Library)

7: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p176 (Smithsonian Library)

8: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p220 (Smithsonian Library)

9: The Cycle Age and Trade Review, Volume 23 p486 (Smithsonian Library)

10: Photos courtesy Bibliothéque Nationale de France

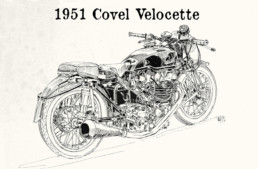

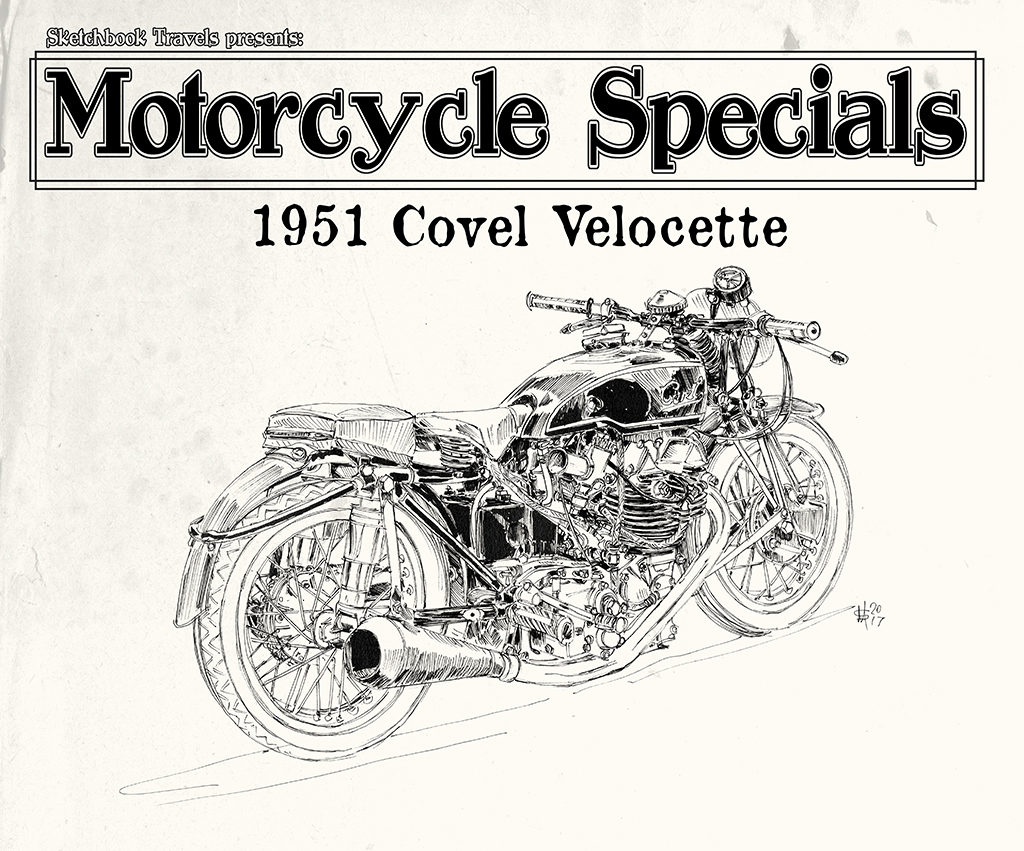

Double Trouble: the CoVel Story

Martin Squires: Jake De Rosier at 90mph

Illustrations by Martin Squires

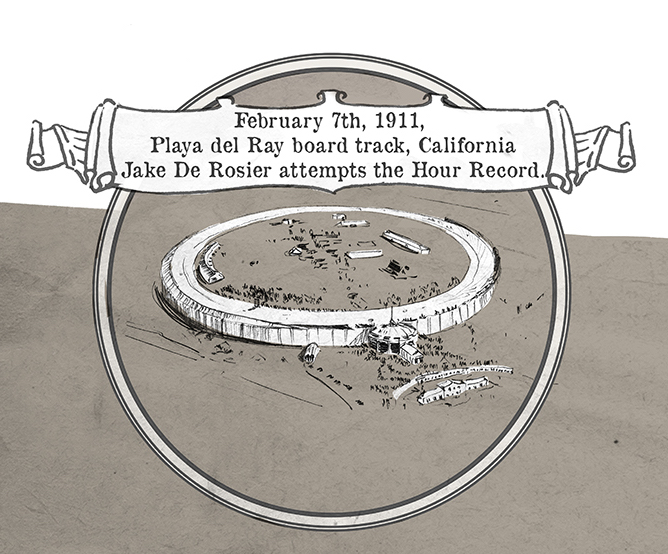

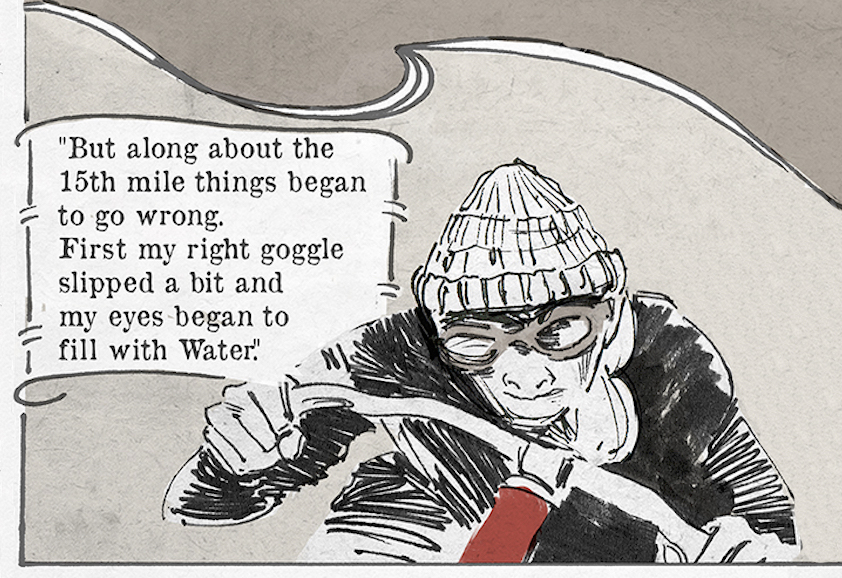

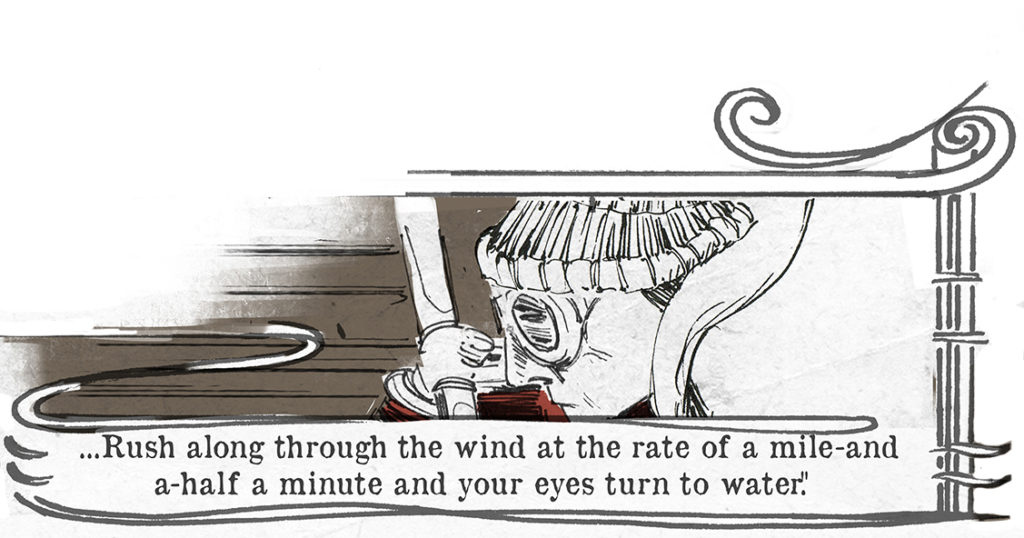

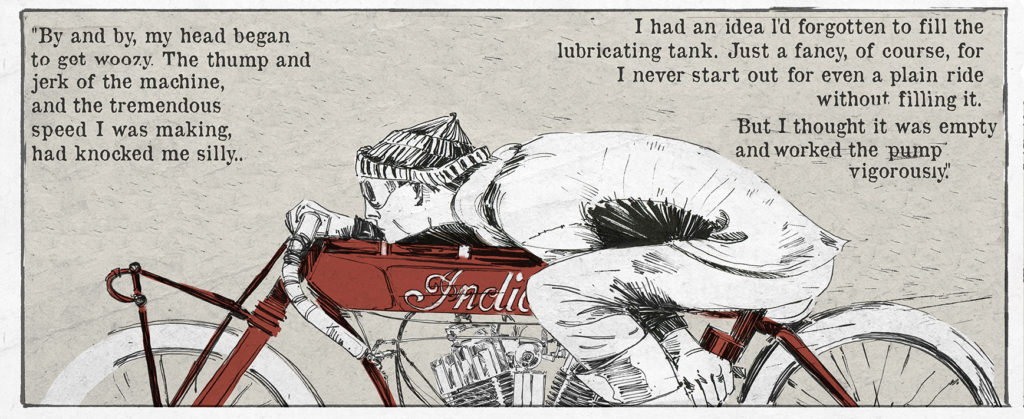

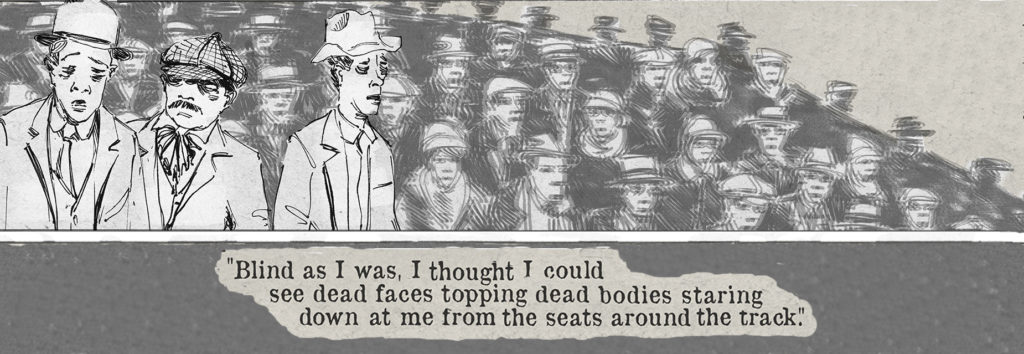

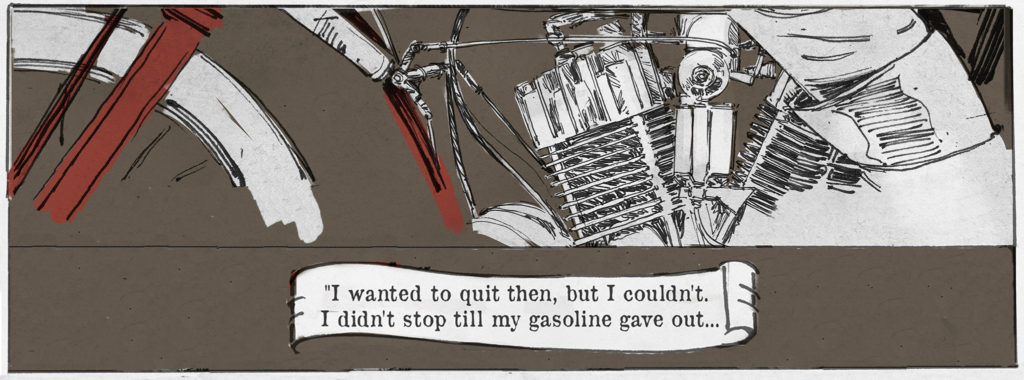

What does it feel like to do 90mph? Plenty can answer that today, but very few could in 1911. The question was posed to Jake DeRosier in 1911, after the successful completion of a 90mph stint on the Playa Del Rey board track, on an Indian V-twin with no suspension or brakes, riding over the rough, uneven, and slippery surface of pine board laid end-to-end in an endless loop. DeRosier was the most famous competition rider in the world in the first decade of the 20th Century, and the first salaried professional motorcycle racer. He would shortly cross the Atlantic to race for Indian at the Isle of Man and Brooklands, where Indians took 1-2-3 at the TT, and DeRosier beat his great rival, Charlie Collier on his Matchless, in a series of match races at Brooklands: he was on top of the world, but from this interview, it doesn't sound easy.

Vintagent Contributor Martin Squires was inspired to illustrate a famous interview with DeRosier from MotorCycling magazine, published in their 14th March 1911 issue. He's broken up his format specially for TheVintagent.com.

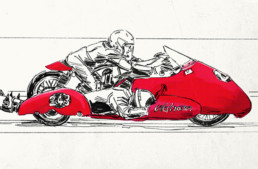

Motorcycle Specials: Maurice Brierley’s Methamon

Words and Illustrations by Martin Squires

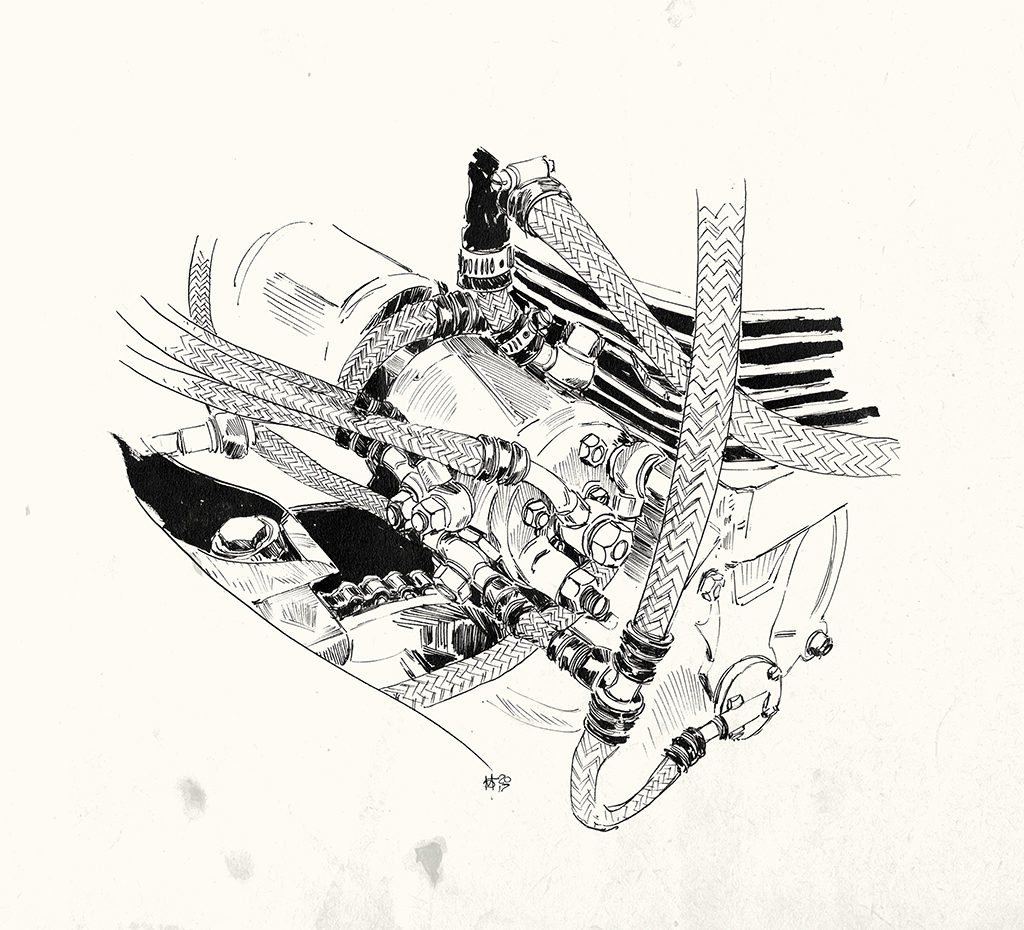

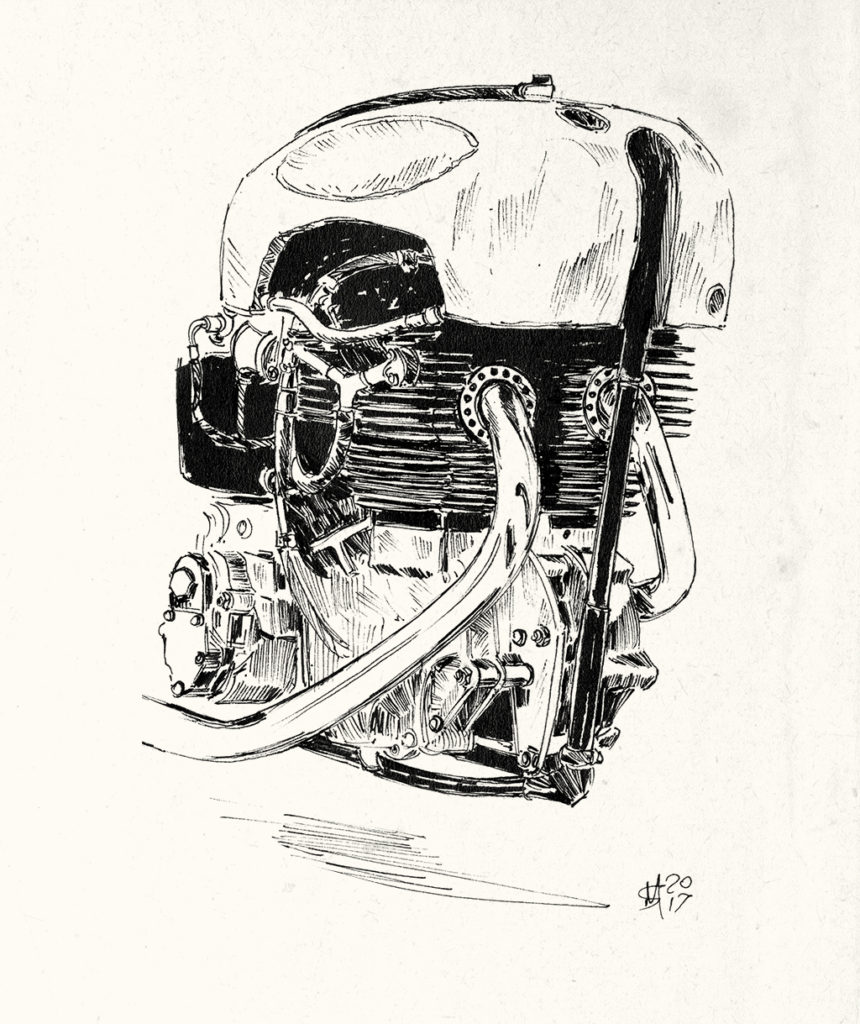

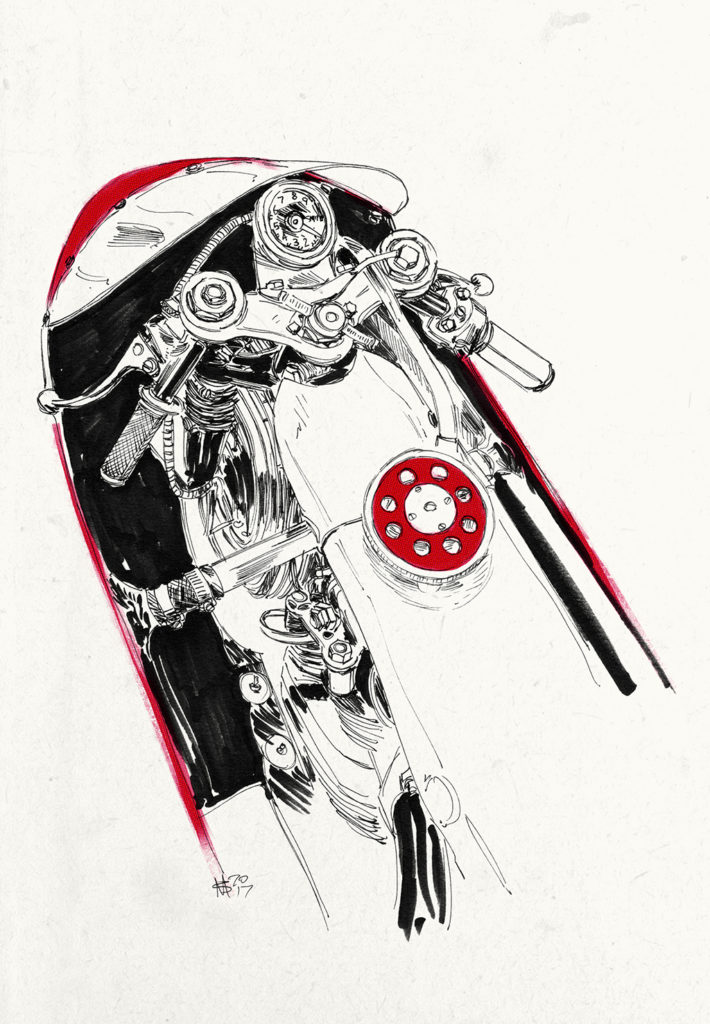

Found on the VMCC stand at the Stafford show, over April 27/28 2017, I was intrigued by this sprint sidecar outfit. I hadn’t seen or heard of Methamon before, and was instantly pulled into the intricacies of the engineering involved in building this special. I was soon to find out more about this fantastic machine and its creator.

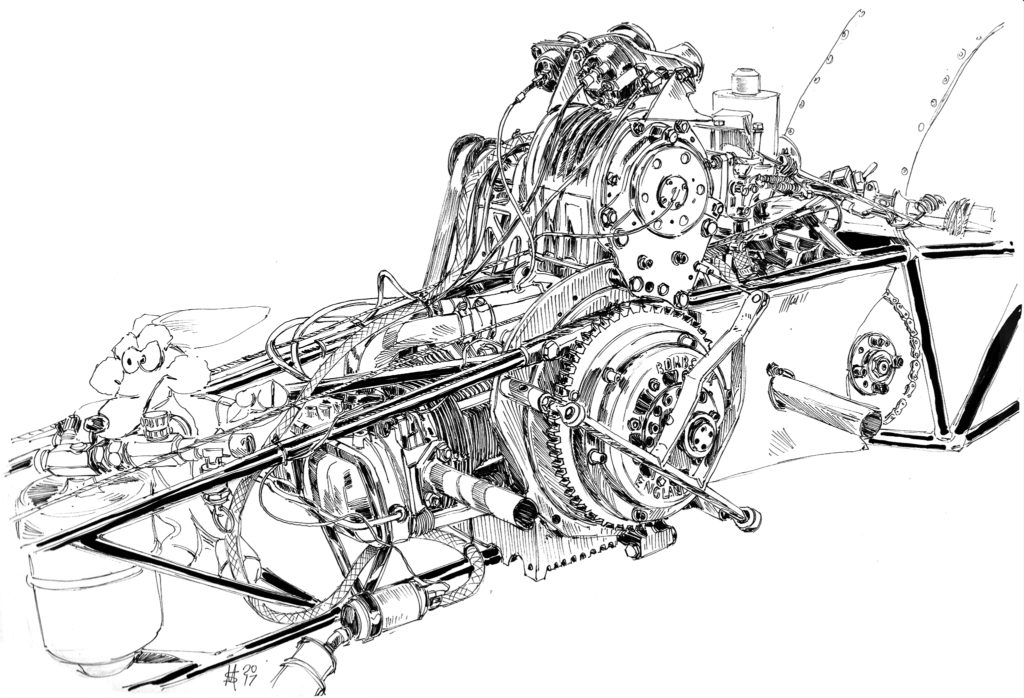

Maurice Brierley had worked for de Havilland in the early 1950s and was an accomplished engineer, despite sometimes being described as a quintessential ‘English eccentric.’ Outside of his work for de Havilland, Maurice competed in hill climbs and sprints, using both cars and motorcycles. In the early 1950s, while leaving work on his motorcycle from the de Havilland site in Hatfield, he was side-swiped by a car, with the accident resulting in him losing his right leg. This didn’t deter Maurice from continuing to indulge in his love of racing. In 1959, he built and subsequently ran a Vincent sidecar outfit, a third-wheel chosen for stability due his now missing right leg. The special sidecar was provided by Watsonian and fitted on the ‘wrong’ side which gave Maurice somewhere to rest his false limb. Maurice had quite a few passengers, but the platform was often frequented by Sheelagh Neal, in a feet first position. This enabled Sheelagh to keep her weight towards the back for better traction.

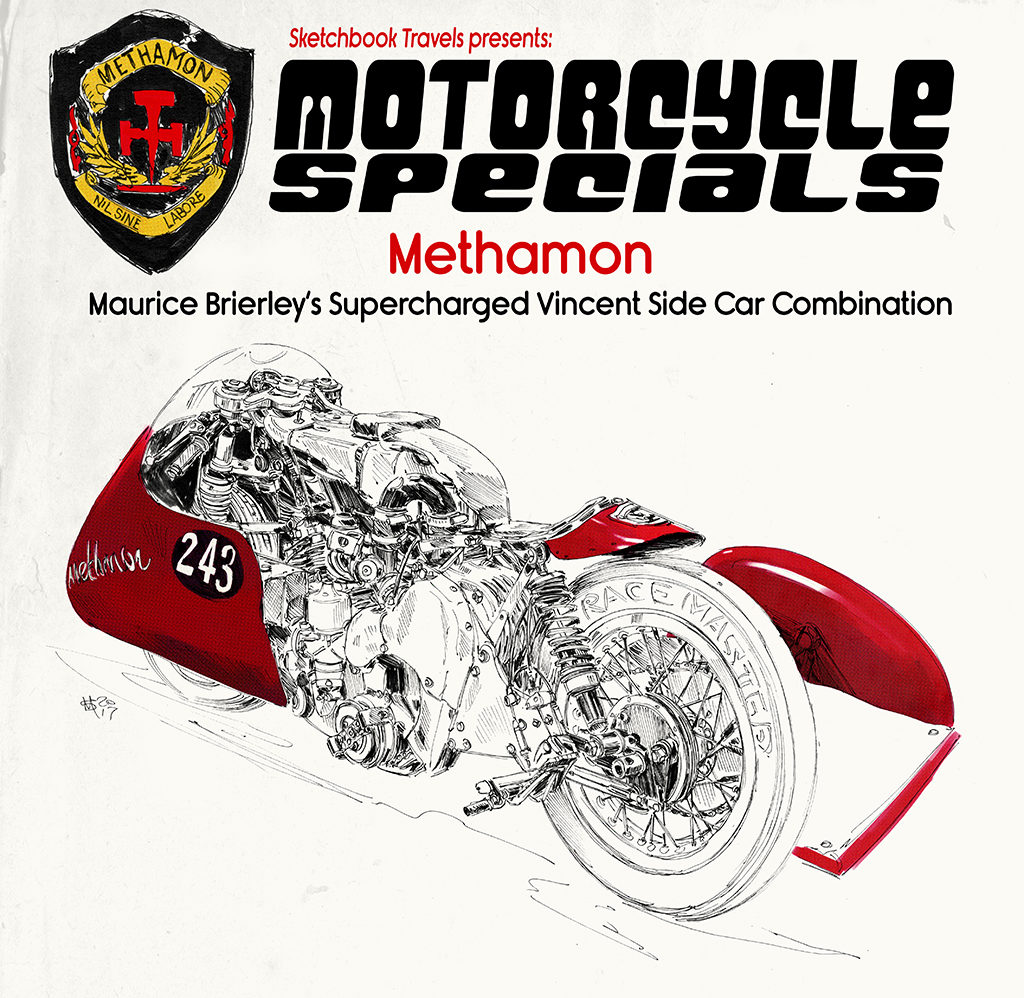

The Vincent engine was developed to such an extent that it exceeded what could be measured on Maurice’s home-made dynamometer and once he reached the limit with normal aspiration, he made the decision to run a C142 Shorrock supercharger. This is a large 1500cc supercharger that runs at about 15-18psi of boost. Different valve timing and compression ratios were employed on front and back cylinders in order to compensate for the different lengths of pipe from the supercharger. The cylinders run 90mm bore Manx Norton pistons – taking the total capacity out to 1142cc – and are topped off with big port Vincent Grey Flash heads. Typical of the time, Maurice was using parts that were plentiful and affordable and using them to their best ability.

Moving over to the supercharged incarnation, Maurice had to lengthen and lighten the chassis. The outfit has many nuts and bolts that were used in the aviation industry, due to his work at de Havilland. Another thing that comes through from Maurice’s engineering background is that there are no washers in sight; he believed that they were unnecessary and only added weight. Methamon was also fitted with AJS 7R forks and brake and an extended Velocette swinging arm.

With only the use of his left leg, Maurice adapted Methamon to have all the foot controls on that side. These incorporated a rear brake that would partially lock on, enabling Maurice to engage first gear ready for take-off and stop the wheel from spinning too much on leaving the start line. The brake is automatically released on engaging second gear.

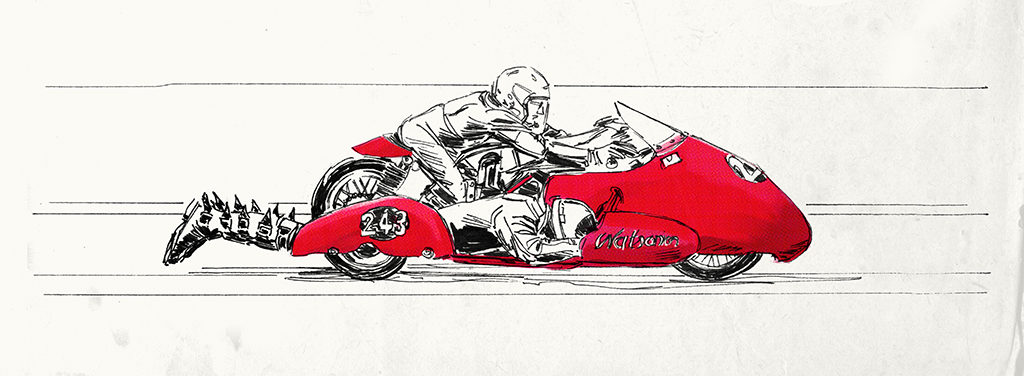

Over a period of four years, Maurice and Methamon dominated the 1200cc three-wheeled class. On June 20, 1964, Maurice set two world records at Chelveston Airfield – the One Kilometre Flying Start at 222.952kph (138.536mph) and the One Kilometre Standing Start at 154.825kph (96.204mph). Having set these records, Castrol offered to sponsor Maurice to go to the USA to attempt to break the 200mph barrier. But due to Castrol moving funding to the Monty Carlo Rally, Maurice was subsequently told there was no money left to fund his attempt. After this, he felt that he had taken his sprinting as far as he could and retired. His parting song to the sprinting world was a small book called ’Supercharging Cars and Motorcycles,’ a concise 56-page volume which is something of a bible on the subject of superchargers.

Initially, Methamon was displayed in the Shuttleworth Collection in Bedfordshire, before being donated to the VMCC museum at Stanford Hall. From here it disappeared, eventually ending up in the basement of the Donington Park Museum, still geared to exceed 200mph. In 2010, it was exhumed from the basement to be resurrected by the duo of Chris Illman and Colin Jeffries of the VMCC Sprint Section. Their first run on the sidecar outfit was at Mallory Park in 2011 at the Festival of 1000 Bikes and it has been run in competitive sprints and demonstrations ever since, with times now equalling those of Brierley at his peak.

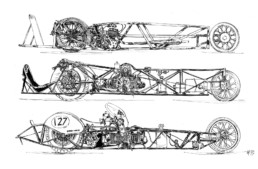

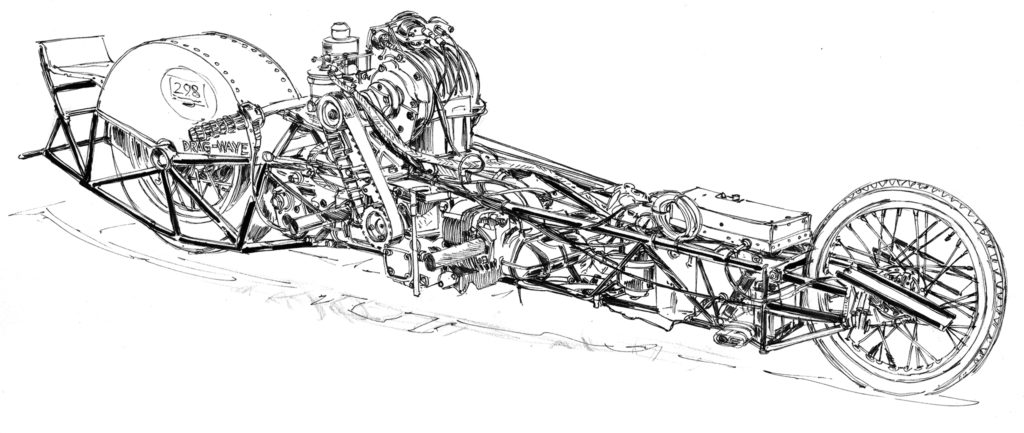

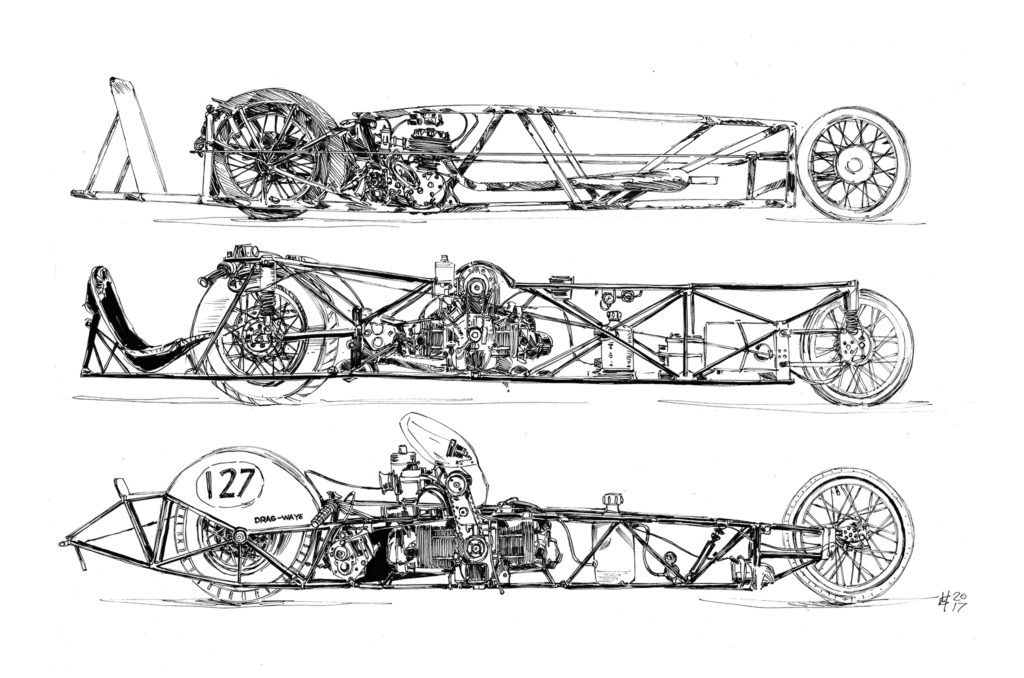

Motorcycle Specials: Drag Waye

The next day I searched Keith Lee’s excellent ‘Drag Bike Racing in Britain’ to research John Hobbs and his incredible Hobbit machines. There I discovered my 'long bike', called Drag Waye, the oddball machine with the rider right out back. I wanted to find out more, but it wasn’t until the next year's George Brown Sprint that I spent time with Drag Waye and had a chance to talk to the current campaigners of this historical oddity.

In order to achieve this 10 to 12% slip, Waye designed a chassis that moved as much weight towards the back wheel as possible. The majority of weight on a motorcycle is comprised of the rider, engine and gearbox, so Waye decided the simplest solution was to move the rider fully to the rear a machine, behind the rear wheel, as moving the engine and gearbox behind the wheel was more complicated. This thinking mirrored the American 'slingshot' four-wheeled dragsters of the period, which placed the driver behind the rear axle, and the engine just ahead.

To test his theory in 1961, Waye modified an old 16H Norton with a sidevalve 500cc motor - hardly an inspiring start for a dragster - and removed the steering head. He extended the frame using scrap water pipe to create a 'rail' frame with a long wheelbase. The seat was mounted behind the rear wheel and hub-centre steering was incorporated to keep the centre of gravity as low as possible. Initial tests on a disused airfield, with Howard German at the helm, revealed that riding the prototype had a psychological component, as a rider needs to lift his/her feet off the ground so the machine can take off. Once this was overcome, Waye was convinced of his idea, and a new machine was built.

The VW flat-four was a controversial engine choice; designed for long life at lower power, the air-cooled car engine was not an obvious choice for sprinting. To produce real power, the VW motor would need to be supercharged, and a four-cylinder engine would deliver smooth power to the rear wheel. The cylinders were sleeved down to give a total engine capacity of 980cc, using widely available (at 10p each) 350cc Royal Enfield WD side-valve pistons!

Waye, an electronics boffin, equipped his dragster with recording equipment, so data could be analyzed from each test run; an unheard-of practice at the time. One instrument recorded the distance covered every tenth of a second, while a second instrument recorded the acceleration in G-forces, utilizing a weighted pencil pushing against a spring that plotted a graph on a scrolling piece of paper. In this guise, the machine he named 'Drag Waye' recorded 12.1s runs on the quarter mile. The test equipment would not be mounted on subsequent timed runs, as the machine needed to lose weight, and the engine needed more power to be competitive.

An update in The Motor Cycle, September 23, 1965 reported the weight was now down to 450lb. The main change was a lighter frame. Stress engineer Jim Strong (who also worked at Hawker) worked with Waye to produce a simpler structure with lighter gauge tubing. The centre of gravity was lowered and the wheelbase was shortened by a foot... but that was done so the bike fit it in the van! The rear suspension was replaced with a rigid back end, and the front hydraulic suspension was replaced with a single pivoted fork using rubber bands. All these changes added up to a great weight saving. The initial problem with this lighter weight build was its tendency to wheelie on take-off, so a lead lump was added up front to solve the problem, although this counteracted some of the clever weight saving.

In 1967 Howard German had to retire from the Drag Waye project due to other business commitments. Luckily Dave Lecoq had test-ridden Drag Waye since 1965 and so the project wasn’t without an experienced rider. After his first few rides, Lecoq convinced Waye that a new riding position was required; Lecoq would hunch over the rear wheel, putting more of his weight directly over the wheel, allowing more control in a power slide. Along with this, Drag Waye was changed to single speed, in the manner of fellow dragster Alf Hagon.

All these changes certainly made a difference as Motor Cycle News reported on Wednesday, August 2, 1967 that Dave Lecoq had taken second place at the Duxford Sprint on July 30, with a run of 10.73s. Drag Waye ran at the 1969 NSA World Record Attempts at RAF Elvington where it took the 1300cc world record with a run of 9.815s for the standing quarter mile. Lecoq ran an east/west run of 9.88s and equalled it on the west/east run; this didn’t beat Alf Hagon’s record of 9.954s by the 1 percent required by the FIA, so was discounted. Determined to beat Hagon, Lecoq ran again recording 9.75s east/west and with his west/east run the average was 9.815s, giving him the 1300cc record. These runs were also the fastest ever over the standing start quarter mile, with an average of 91.69mph.

Drag Waye continued to set faster times. In 1971, at Elvington, our oddball hit 150mph, with a time of 9.58s. After 1972 Drag Waye took a hiatus, but returned to Elvington in 1977 with a new pilot, Brian Jones. Even though it had some handling issues, it set a new 2000cc standing kilometre record of 22.37s. Drag Waye competed until 1982, when it was retired after running at the George Brown Memorial Sprint that year.

Once in their possession, it wasn’t long before John was rebuilding the engine. The plan was to put the machine back to its late 1960s/early 1970s incarnation, as this was when the machine was at its peak. This was no easy task, as there were no notes, only period photos, and the machine had been changed, especially the frame. Tom Touhy, a trike builder, was the man for the job of sorting the frame and work continued with all the interested parties.

Unfortunately, John suffered a stroke that he would never recover from and so work stopped – not only due to the loss of the most capable assistant, but also Terry’s grief curtailed his straight-line enthusiasm. He even sold the sprinter that his father had built for him.

Keith Lee asked Terry on a few occasions if he could bring Drag Waye to Dragstalgia. Initially, Terry couldn’t bring himself to finish the project, though during this time Drag Waye was given over to Tom Touhy in the hope that progress would be made. It did, slowly, but only the motor was fitted into the frame within the following year. Keith Lee rang again; this time, Terry had a change of mind and decided having a deadline would force him to get on. Within six months, more work was done on Drag Waye than had been in the eight years since Scott handed it over.

In July 2016, six years after Terry’s father death, Drag Waye was started in the paddock at Santa Pod for the first time since 1982. Terry has been running and learning about Drag Waye, first hand, since this return to Santa Pod. When I saw it at the George Brown strip last year, Terry had been attempting to run Drag Waye at North Weald and Dragstalgia, but had various issues, including getting thrown off Drag Waye, breaking a couple of ribs and dislocating his shoulder.

The 2017 visit to the George Brown Memorial Sprint was not without issues, as the crash at North Weald in May had damaged the distributor. Luckily, Ian Clark, a VW nut, lived nearby and came to the airfield to save the day. Drag Waye was converted back to points and was good to go. After a cautious run, Terry experienced first hand what Waye and German had on the Norton prototype.

“I never thought in my wildest dreams that riding Drag Waye would prove so difficult and so totally different. How did Dave Lecoq run a 9.3 on this?”

Lecoq actually visited the George Brown Memorial Sprint in 2017, and told Terry; “You’re going to need a lot of practice. Now, have you had it wheelie yet?” On the Sunday Terry got brave and gave it a bit more wrist and, yes, it did.

Motorcycle Specials #1

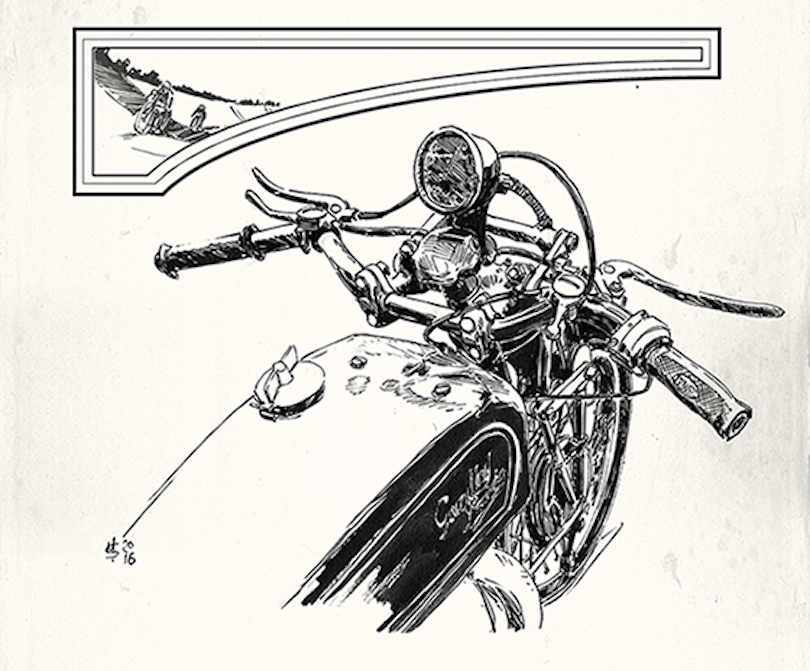

Illustration/Words by Martin Squires

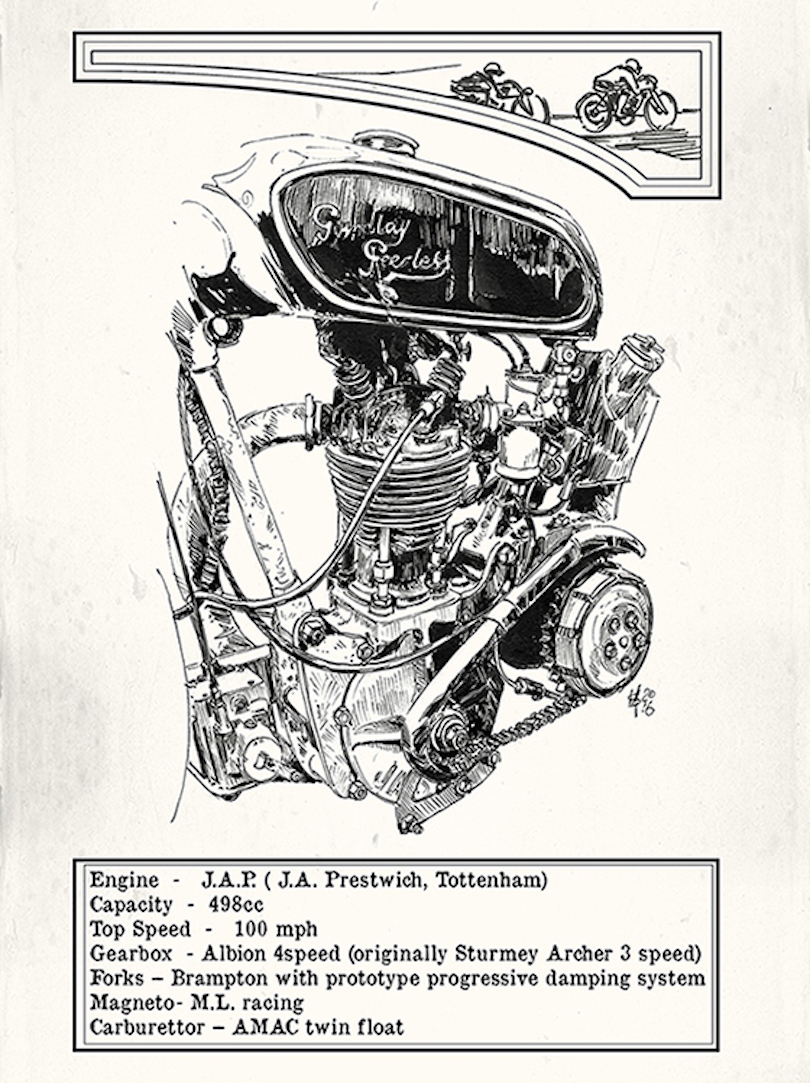

I was overjoyed to see this machine at Stafford Showground on 26th April 2015. I had seen the Original Bill Lacey Grindlay Peerless at Brooklands, but this original condition "Hundred Model" bought a true smile to my face. This particular machine is one of 2 known survivors. The Grindlay Peerless factory produced the “Hundred Model" to celebrate C W G 'Bill' Lacey becoming the first man to cover 100 miles in an hour on British soil in August 1928 on a sub 500cc machine. It’s Believed that the Coventry mark only sold 5 to 6 machines, possibly due to the lack of demand for such a specialist machine. Bill achieved 103.3 miles in that hour on the Grindlay Peerless JAP, an incredible feet of endurance riding on such an early machine. Eariler in the 1920’s the 100 miles in 60 minutes was the ultimate goal for motorcycle manufacturers and their riders. Claude Temple was the first man to do so, averaging almost 102mph at Montlhéry in 1925 on his 996cc OEC-Temple-JAP. The following year at Monthlery Norton rider Bert Denly broke 100mph on a '500' for the first time.

In order to encourage such riding in England The Motor Cycle offered a silver trophy to the first person to break the 100mph mark. Brooklands was the only circuit for such an attempt, an unforgiving course with it’s renowned bumpy surface that launched its riders into the air at any given opportunity. On 1st August 1928 Bill Lacey raised the record to 103.3mph, hitting a top speed of over 105mph which in turn broke the 750cc and 1000cc records. Bill went on to dominate at Brooklands throughout 1928 finishing on the podium at every meeting.

In 1929 Bill increased his distance to 105.25mph setting yet another record. After this continued success Grindlay Peerles produced the “Hundred Model” these machines were essentially the same as the original record breaking machine, complete with nickel plated frame. The replicas were assembled at the Coventry works and then shipped to Lacey’s workshop at Brooklands where Wal Phillips, Lacey’s assistant, would tune the machines to enable them to reach the record speed. Lacey himself would then test each machine to above 100mph on the outer circuit in order to issue an official certificate.

J.D. Potts raced this particular Hundred Model at Brooklands in 1929, in September of the same year he went on to win the Amateur Isle of Man TT. Unfortunately he was disqualified after it was thought he had received factory support, were Grindlay Peerless trying to sell more of these replicas off the back of this, who knows.

In the 1930’s Cyril Norris acquired the Hundred Model. In 1934 Norris had E.C.E. Baragwanath a renowned Brough Superior rider and tuner fit a single port head as this got some more out of the JAP than the twin port the replica was originally fitted with. In order to compete in the 1936 Senior Manx Grand Prix an Albion 4 speed gearbox and an uprated front brake were fitted expressly for the race. These are still present on the machine today. Norris finished 23rd, with a best lap of 33 minutes 37 seconds, averaging 66.9mph.

In the early 50’s Norris used the machine on the road complete with close ratio gearbox and no kickstart! Norris kept the machine until his death in 2000 when it was bought form the family by it’s current owner. Seeing motorcycles like this is such a great experience as you can see the history not only in it's original condition but by the changes from the original factory specification.

Special thanks to Peter Lancaster for his help researching this article.