Greg Willams: What’s the back story to Speed is Expensive?

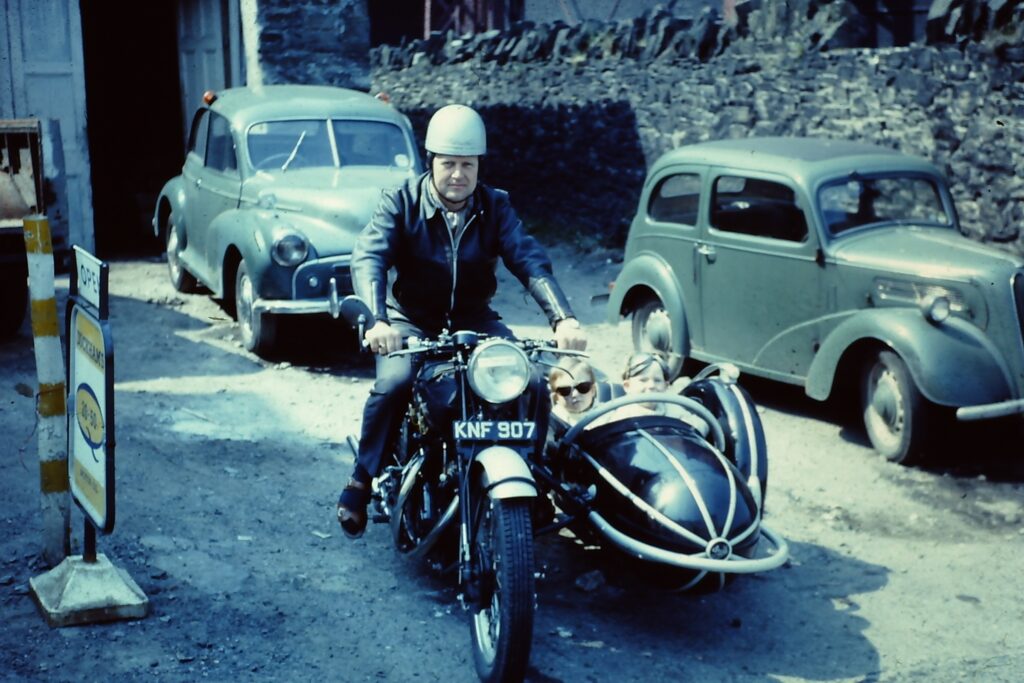

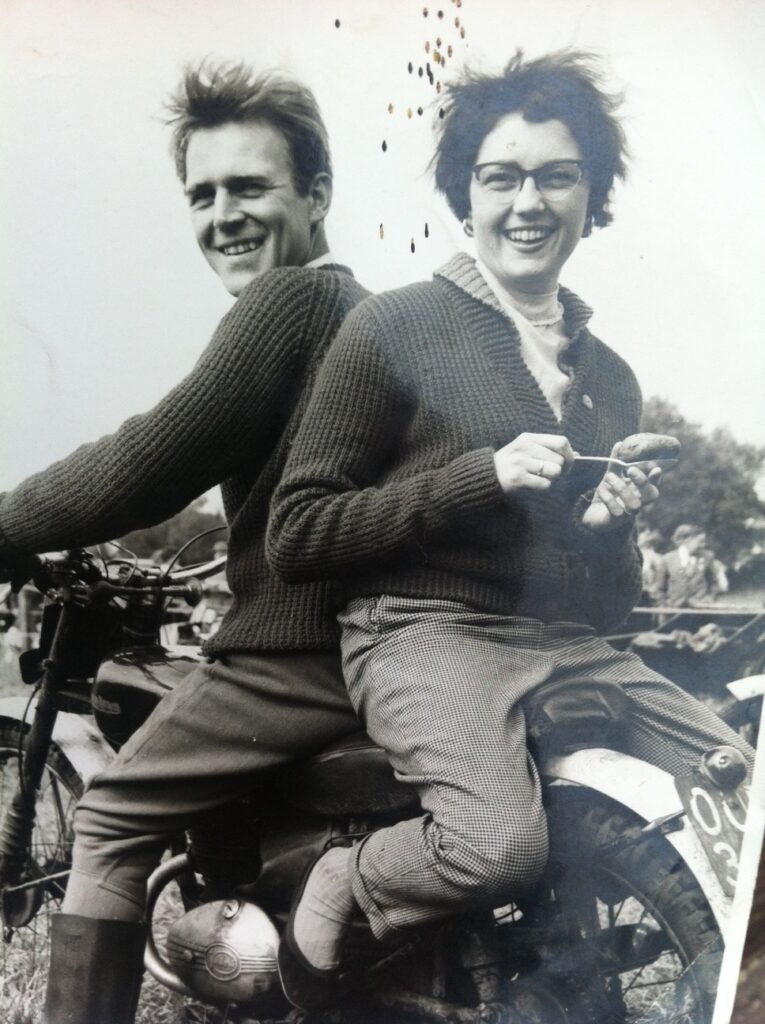

David Lancaster: It started, way back, with me looking through some 35mm slides my parents had taken of their Vincent trips in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, after both had passed away. My folks’ slides were from just 10 or so years after the Second World War ended in 1945 – and they were pioneering taking a bike that far into Europe at the time. No phones back then – no Euro, no credit cards and major currency restrictions (you were only allowed a certain amount in or out of each country). I’ve always read history, and there was a drift emerging that history could – or even should — be told from the shop floor as much as the directors’ office; that as much wisdom, probably more, would emerge from sitting in the workers’ canteen as in the directors’ restaurant for an hour.

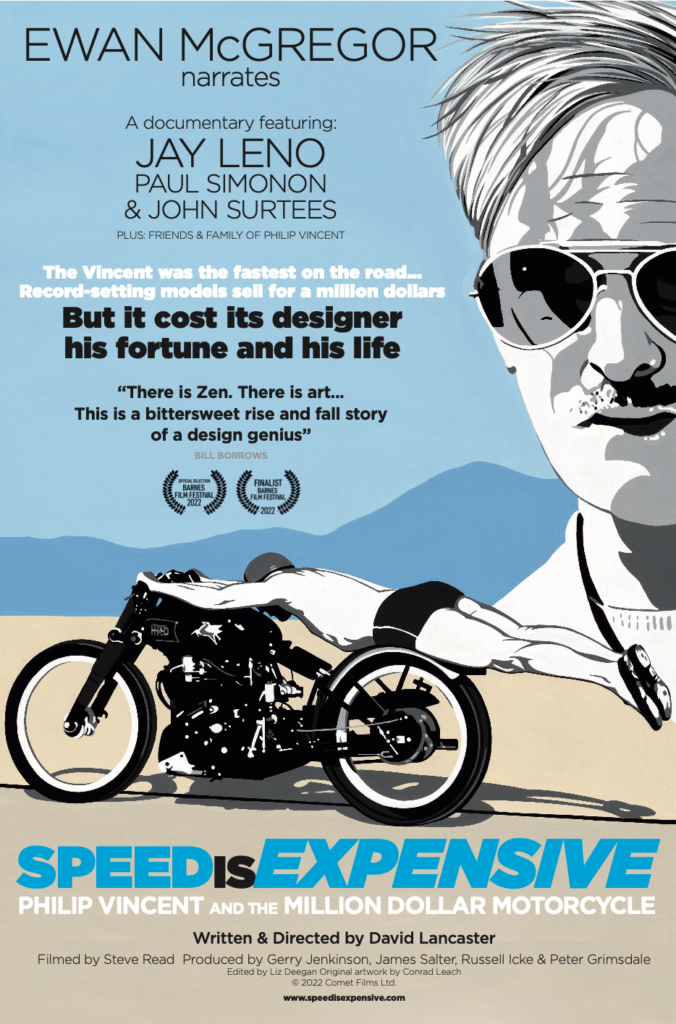

So, over a beer or two, we hatched a plan to track down the remaining men and women who’d built Vincents, to record their recollections. In the end, through social media, contacts and research on sites such as Ancestry, we filmed 14 men and women who worked at Stevenage, the most famous being John Surtees, who was an apprentice there. It was John’s only ever normal job in fact – payslip at the end of the week, day release for college with the other apprentices. From then on, he freelanced for factories becoming, of course, the only man to win world titles on two or four wheels. An amazing man with crystal clear recollection of events 70 years ago.

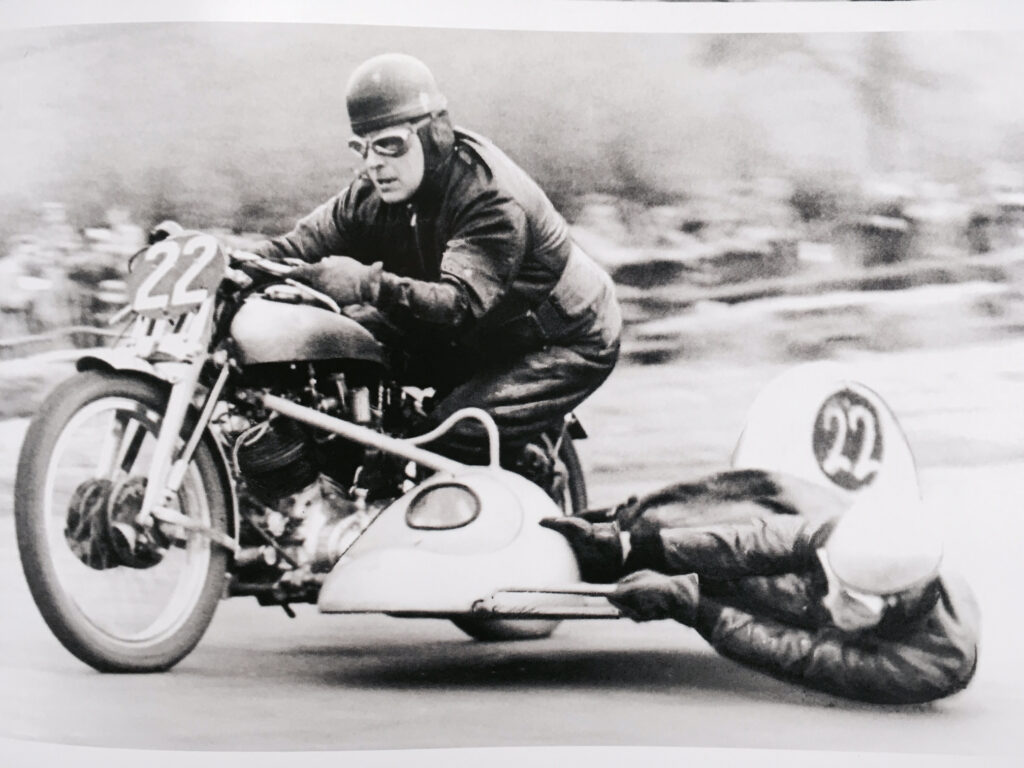

DL: I’d known the Vincent family for many years through my parents: Dee, PCV’s daughter, her husband Robin and then young (grandson) Phil as he grew up. I’d met Phil Irving a good few times at Vincent events, but sadly I’m not sure I met Vincent before his death in 1979. But I may have done. So, Gerry and I asked – badgered, might be more accurate, but that’s documentary-making — to look over and perhaps restore the films shot by Vincent in their care. It was a revelation: home life, race meetings, travel in the USA meeting dealers, some of it on 16mm, filmed with his Bolex camera.

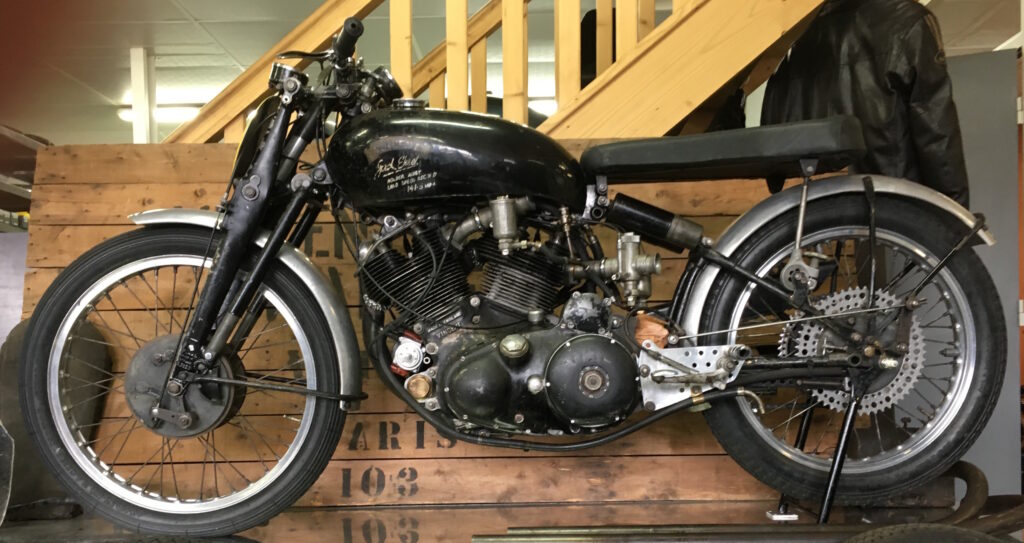

DL: The film was so long in the making because for the most part Gerry and I did everything: research, production, much of the early filming of interviews, then to travel to the USA, Montlhéry in France, and Australia, where we filmed the amazing Irving Vincents on the track, and the record setting Jack Ehret Lightning, back on the very road it set the southern hemisphere land speed record – for bikes and cars – at 141.5 mph in 1953. We were both busy working, too – Gerry lighting shows and me lecturing in journalism at the University of Westminster in London. The quality and extent of Vincent’s films was a milestone – and there were others, each of which elevated the project’s scope and quality: the Australian shoot above, the last full interview with John Surtees, then with our US producer James Salter helping us set up a day with Jay Leno and on to filming Marty Dickerson being re-united with his famous Blue Bike at the Mojave Desert.

What’s in the Garage?

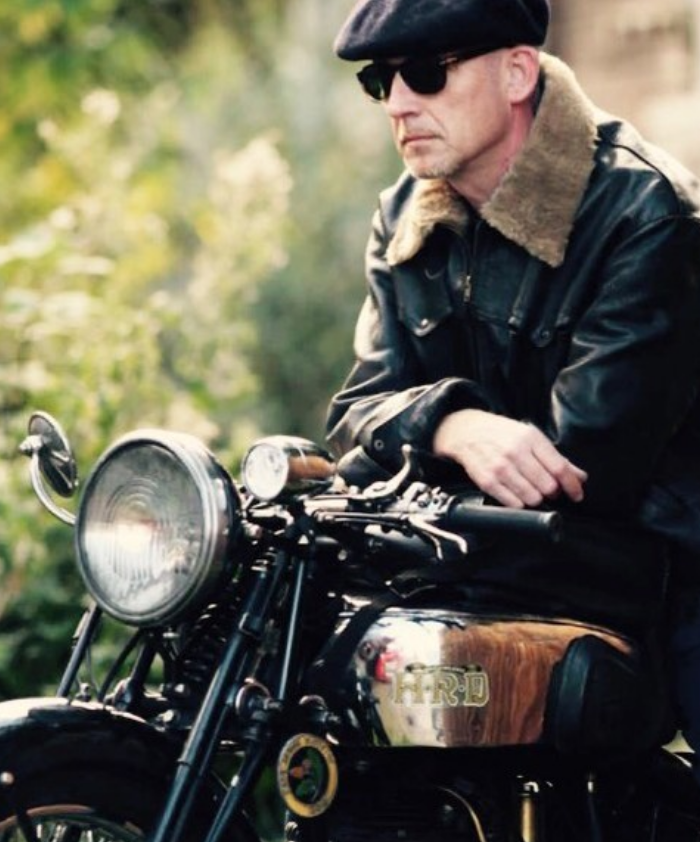

And with that, of course, the film has launched. No word about DVD releases, but David assures me, as noted earlier, that work is underway to get the film out to all markets keen to view it. In the meantime, David will enjoy running his early Rapide, a bike that was owned by his father in the 1950s and the very machine his parents used for many of their adventures. It had been sold out of the family, David found it in Germany, “and then swooped when it came up for sale at Bonhams.” He’s not letting that one go, but he did sell a 1939 Comet which he’d kept for 10 years. Of the Comet, he says, “It was a wonderful bike: reasonably fast, and on a smooth road great handling, with excellent brakes. Had a wonderful ride at Wheels and Waves, 2015 I think, when Johnny Boneyard and I vanned Paul Simonon’s ‘Wot No Bike?’ paintings [read David’s story on Paul’s book here] and our bikes down. I still remember cruising along with Paul d’Orleans and Susan McLaughlin on the northern Spanish backroads, they on a Commando, ducking and diving into bends. Great trip”.

Finally … back to the classics we cone here for .. albeit this.n in film form .

Gotta say … if the multiple clips the producers put on Steal(You)Tube are any indication … the frustrations of waiting will prove well worth the wait once I’ve got this bloody film in hand or on the Tele

In other words … everything about this film says …. Buy/Watch me … ASAP

And err .. thanks for the interview Mr W … a lil sumpin to tide us over till the thing makes it our way !

😎

One concern about the film though after reviewing the multiple YouTube clips and the articles floating around including this one … where the hell is Big Sid Biberman … THE Vincent legend in the US.. the man who established Vincent as a race bike in the US … the man who stood by Vincent thru thick and thin … right down to his esteemed son Matthew .. not to mention most trusted and befriended by none other than …

Philip Vincent himself .

Truthfully I’ve only seen the multiple clips [ film aint made it here yet ] … so maybe I’m out of line … if so .. mea culpa and apologies .. but if not …

Where in the H-E double (bleeping ) hockey sticks is Big Sid ,, and if he aint in it … how in the H-E double hockey sticks did the producers leave him out ?

How can i get in contact with David Lancaster?

Thanks!

Peter

lancaster998 at yahoo.co.uk