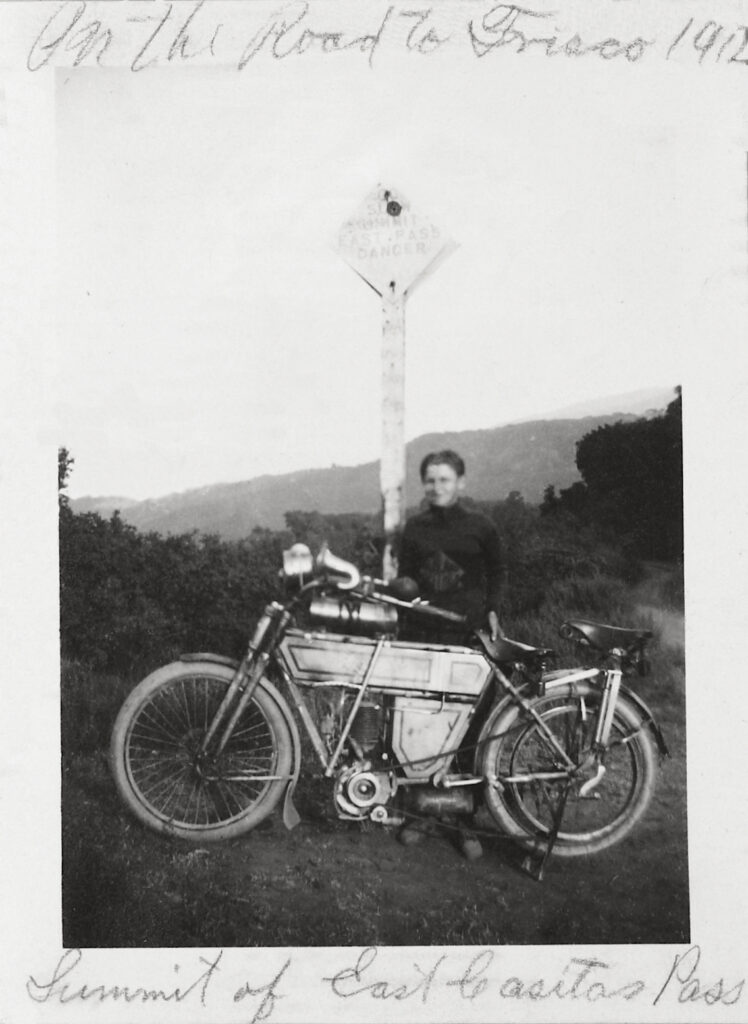

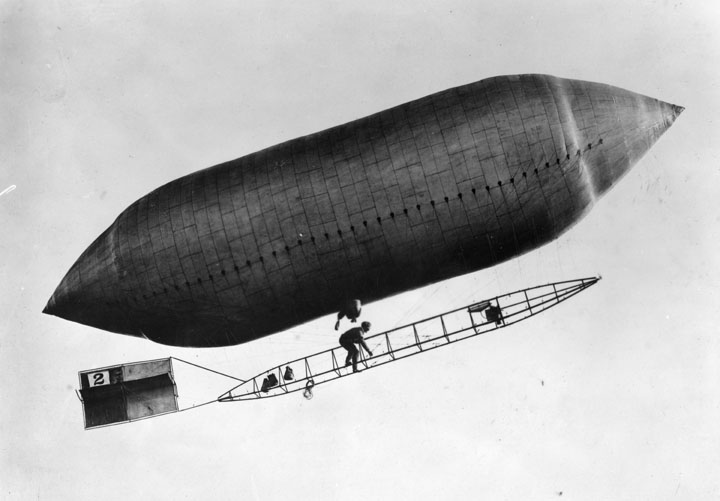

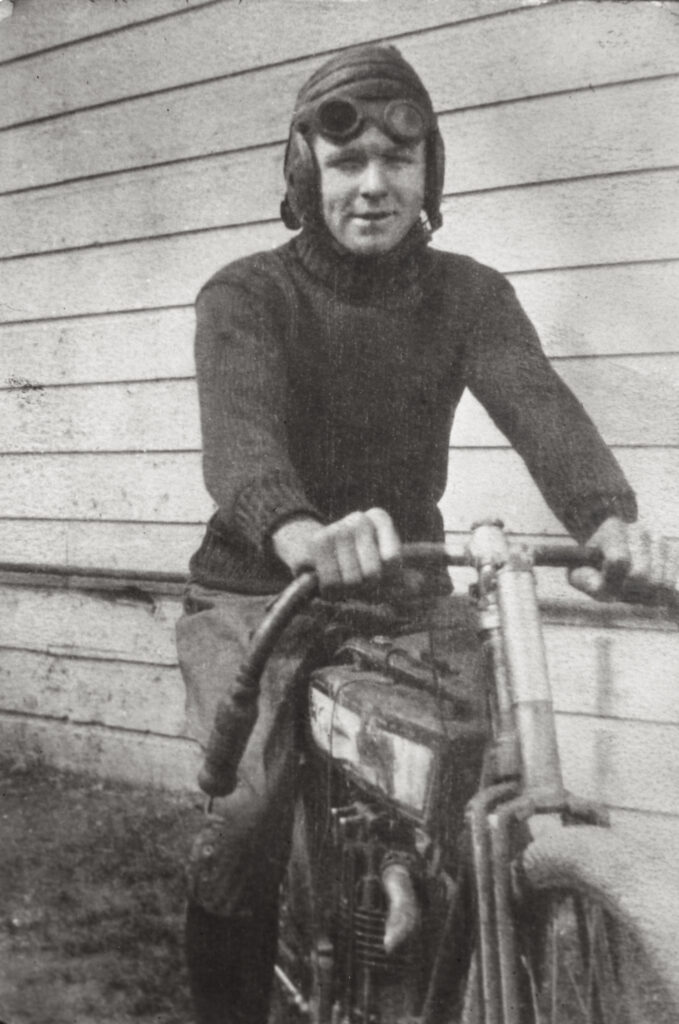

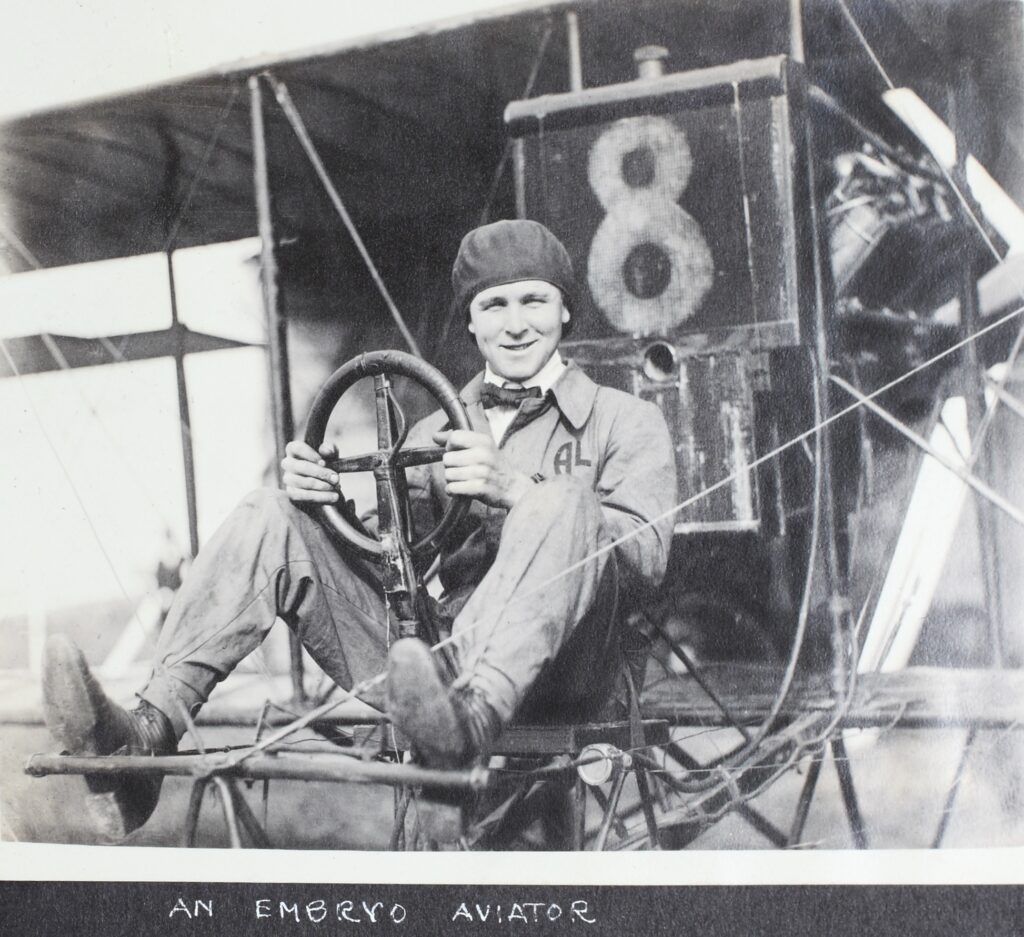

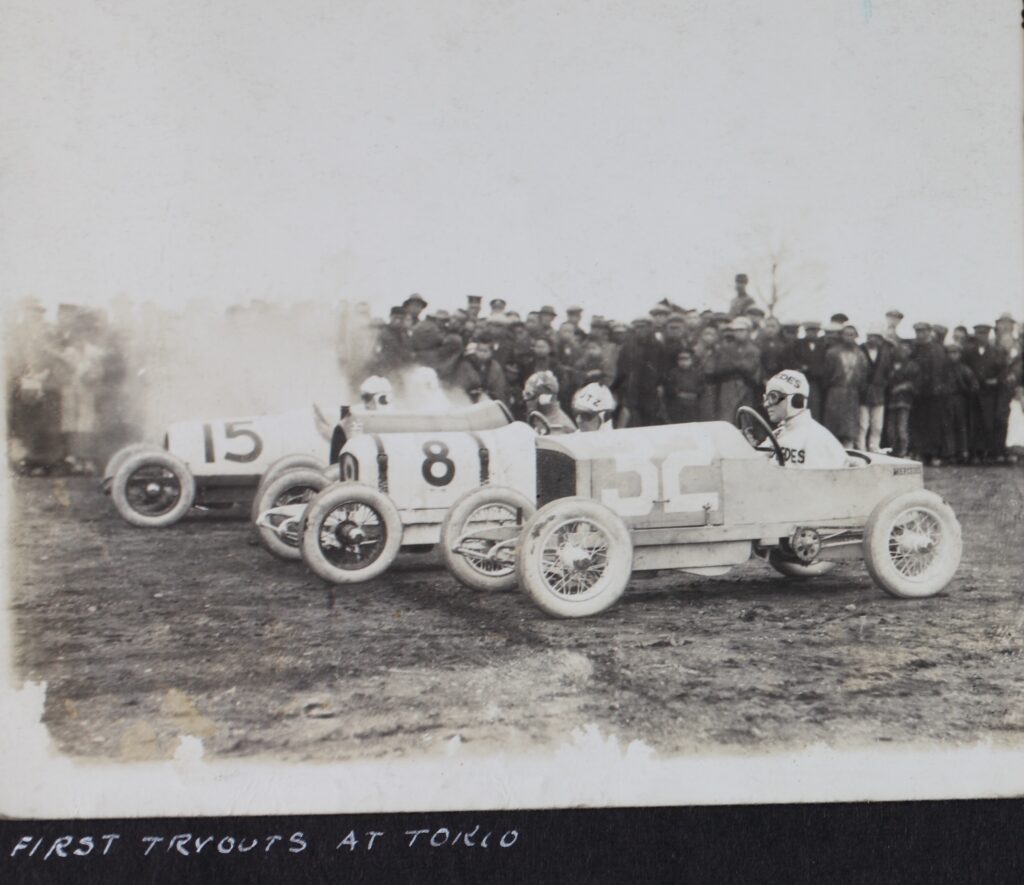

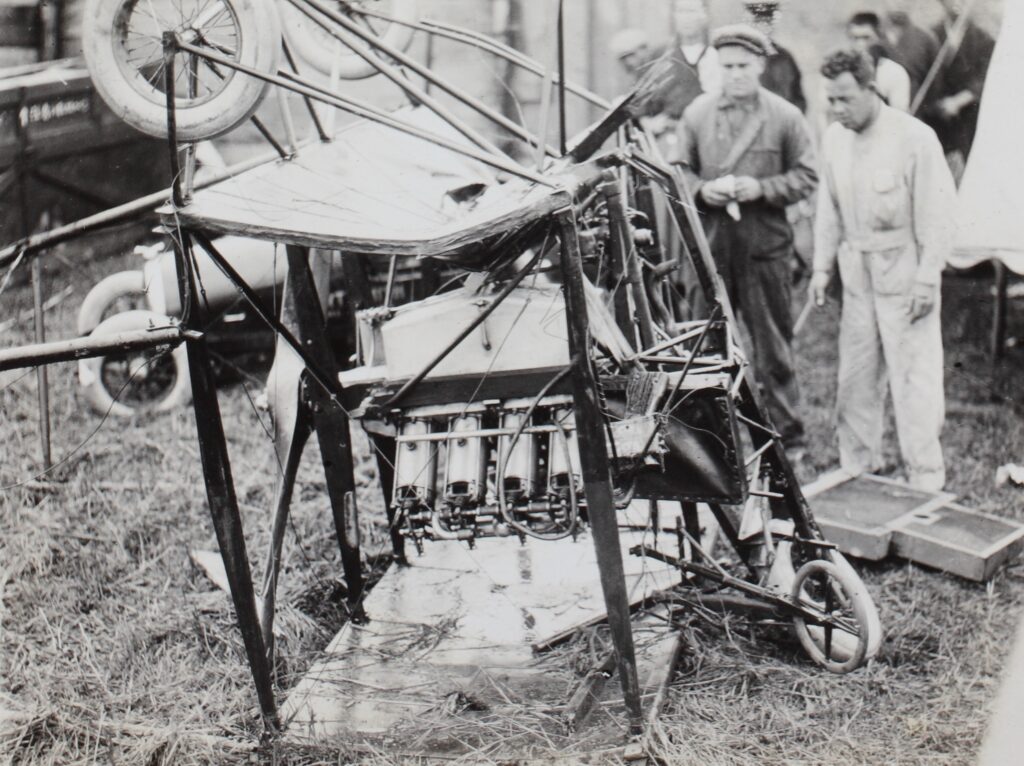

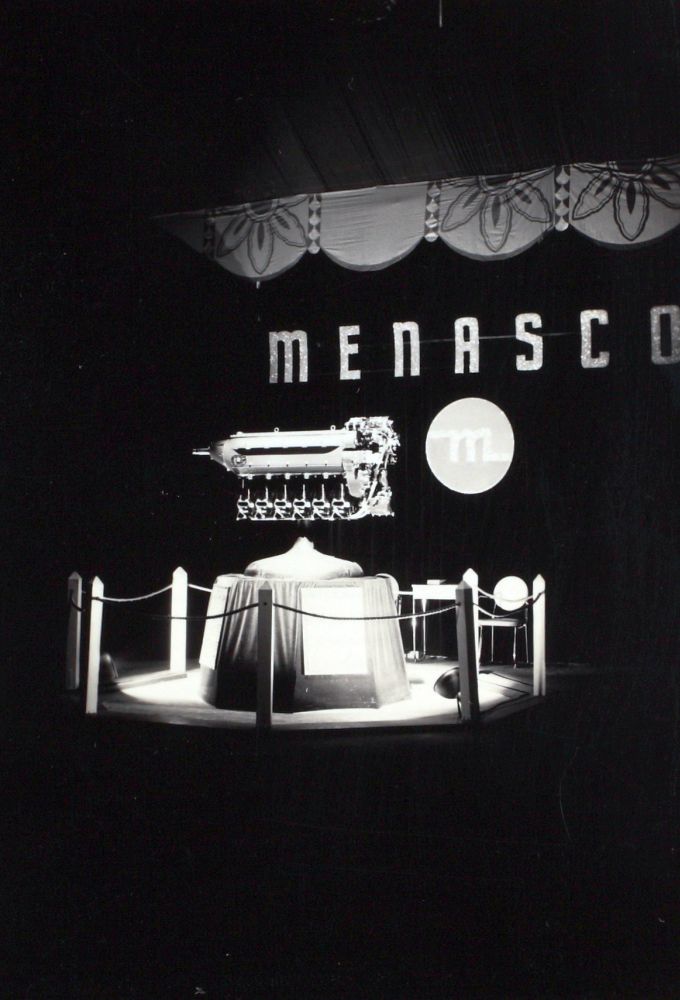

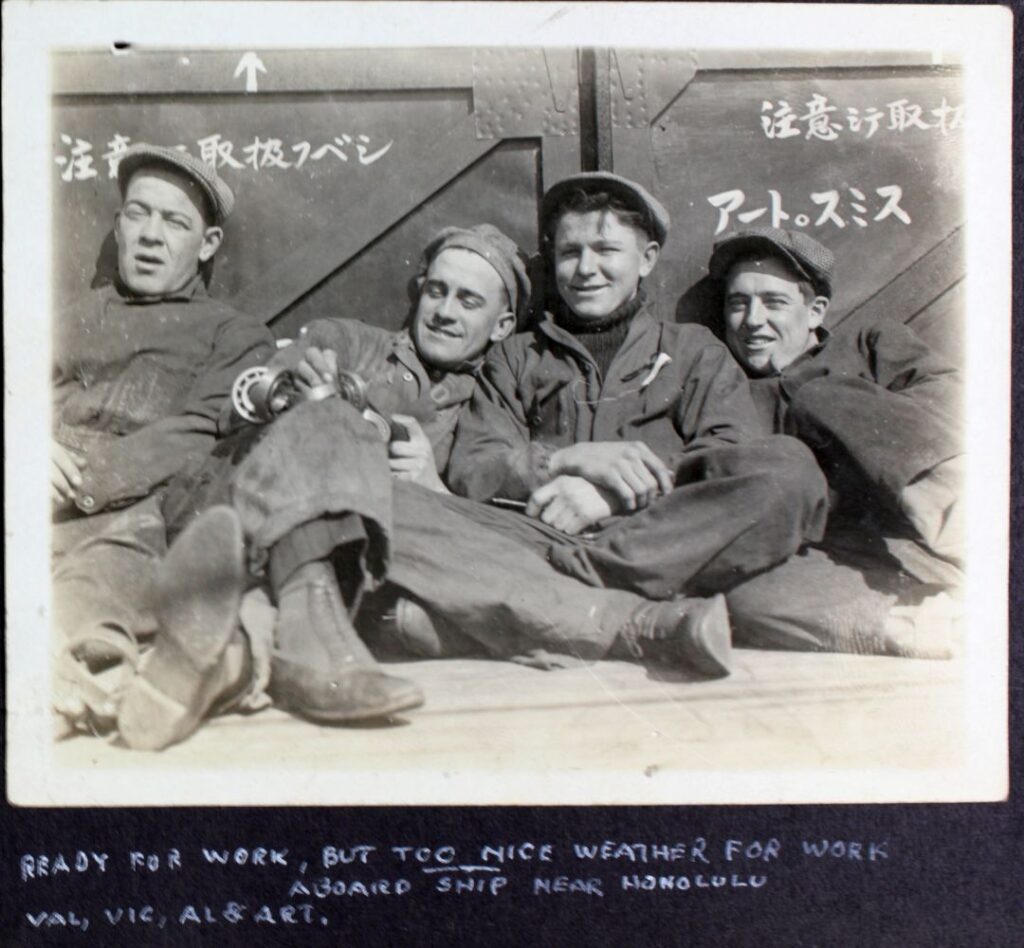

If you were asked to define a swashbuckling life, what would that include? How about motorcycle racing, wing-walking, car racing, working an international carnival circuit, piloting experimental planes, and manufacturing the winningest aero racing engines of the 1930s? There’s only one man with such a resumé: Albert Menasco. And yet, I’d never heard of him until Dr. Robin Tuluie (see our article ‘Actually it IS Rocket Science’) introduced me to the name via the 1928-ish aero-engine race car he’d built using a Menasco engine, but more on that anon. Curiosity about Menasco revealed he was a quintessentially adventurous American in the ‘Teens, a motor-showman when a cocktail of unbridled enthusiasm, innocence and technical know-how would typically end with you famous, dead, or famously dead. Menasco somehow walked the middle way, and ended as neither, while his legacy and impact continue to this day, nearly unheralded.

Two thumbs up to the power of ten for this’n PdO !!!!!