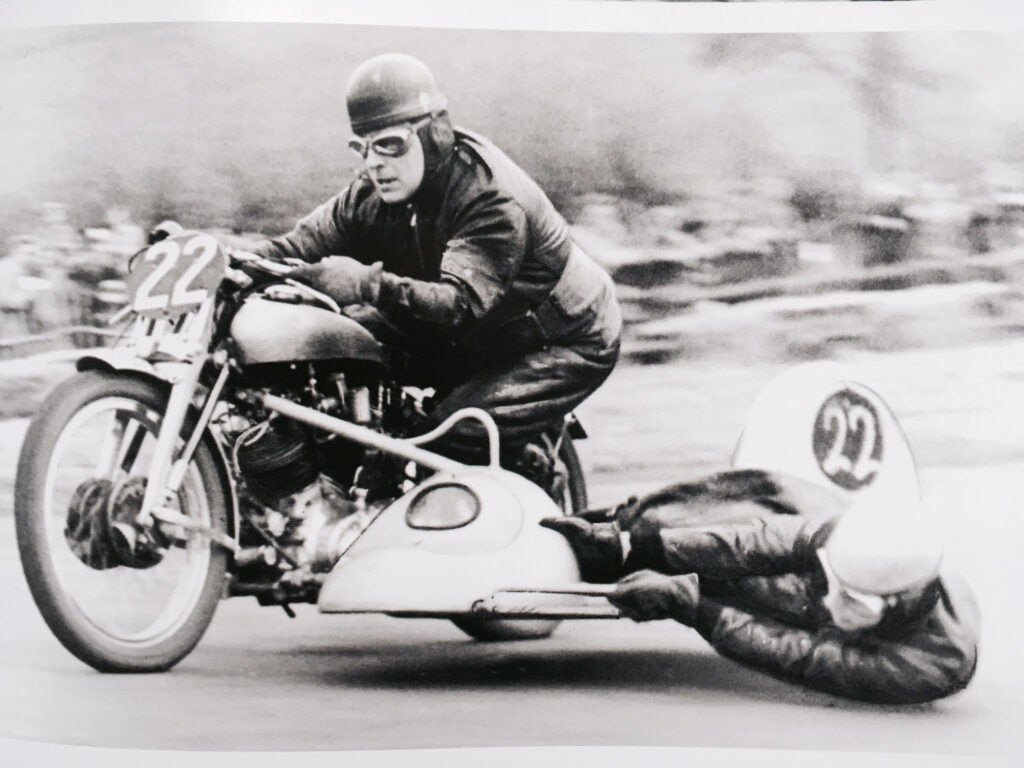

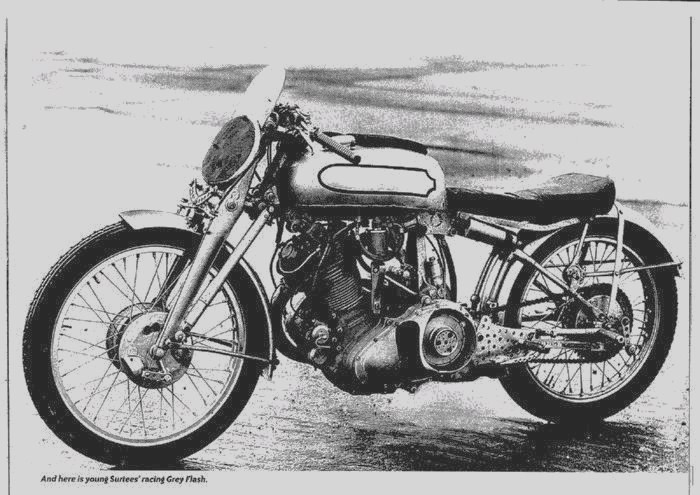

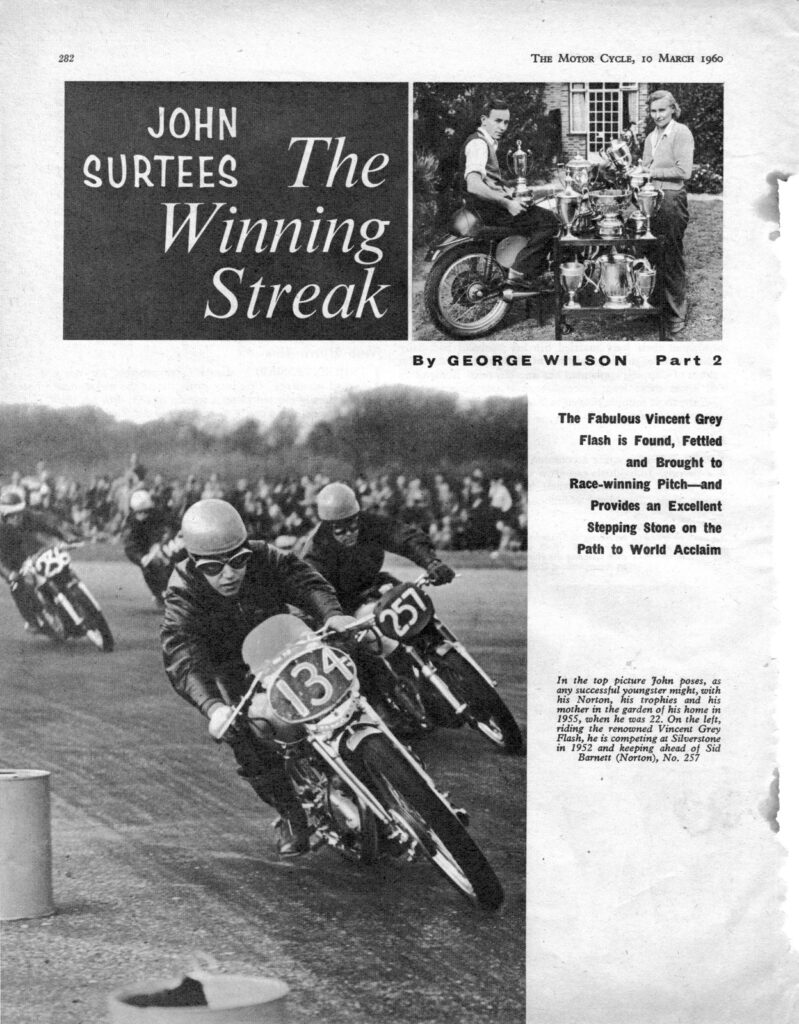

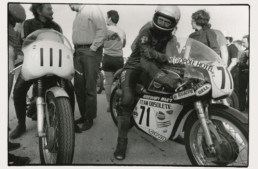

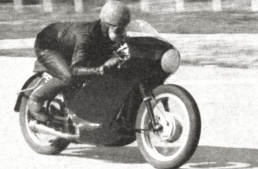

Speed is Expensive director David Lancaster’s interview with one-time Vincent apprentice John Surtees would prove to be one the racer’s last. To mark the release of unseen footage from the award-winning documentary, here is David’s account of meeting the only man to win World Championship titles on both two and four wheels: Surtees won seven motorcycle championships between 1958-60, and one F1 title, in 1964.

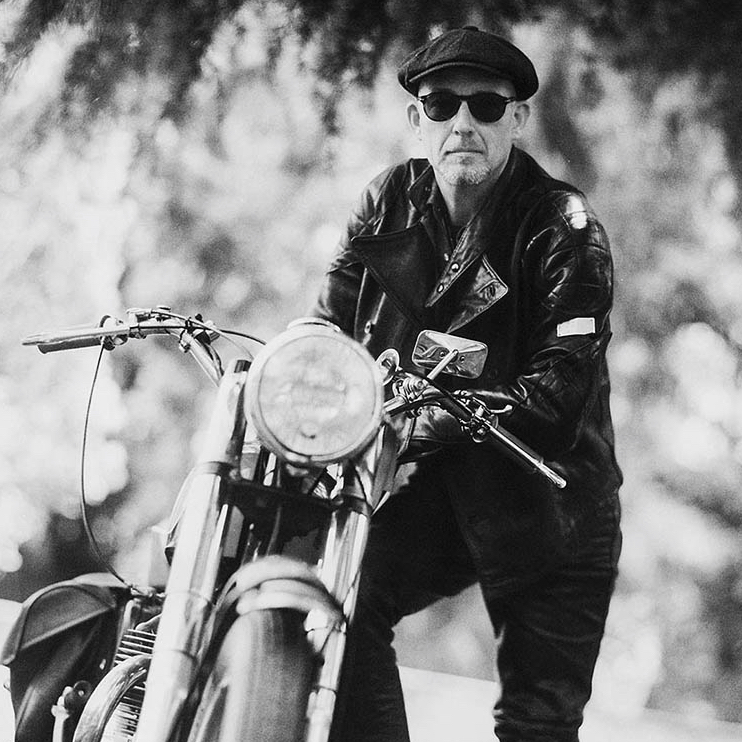

The contemporary portraits of John Surtees were taken by Steve Read.

Then, pausing, the blue eyes beginning to water: “And I know Henry would approve, too.”

John Surtees was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul’s Church in Lingfield, Surrey, next to his son Henry.

The Speed is Expensive Deluxe edition download package features the full film – plus 50 minutes of extra footage with John Surtees, Jay Leno, plus friends and family of Philip Vincent and Phil Irving. Head to –

He lectures in journalism at the University of Westminster and is director-producer of SpeedisExpensive. Follow him on Instagram and on Facebook.

Related Posts

February 26, 2018

Velocettes at Montlhéry: 24 Hours at 100mph

It's a record that's never been beaten:…

Ahhhh …. Surtees … the one and only ( F1 & MotoGP world champion ) … not to mention Vincent enthusiast /racer ..never to be repeated again .

Sigh … Rossi had his chance ….but like a strunz he turned it down .

Oh well … as for the video … still in unobtainium land …. unfortunately …. sigh …

” Oh well ”

😎

Hi – you can buy the DVD in the USA from Amazon, on here – https://www.amazon.com/Speed-Expensive-Vincent-Million-Motorcycle/dp/B0CFP5KCBW

Best wishes,

David Lancaster

David…. I know I’m/we’re outliers ’bout this’n …. but we don’t do no Amazon …. or any other kind of online financial transactions …. for a multitude of reasons …

Got one more option to try after the holidays …. but after that …

” Oh Well “

when was the first motorcycle race?

when the second motorcycle was built

Not sure it even took that long … all bets being … the first was between a horse and an M/C

😎