[This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of The Automobile magazine. It looks much better in print: order a copy!] Picture a scooter. Any scooter, every scooter. Regardless of brand or era, they’re fundamentally the same, a genotype of unthreatening little motorcycles with three common elements: enclosed bodywork, a flat footwell, and small wheels. They are ubiquitous and popular around the world, because, in our murky subconscious, sitting in a chair does not conjure the psychic potency of straddling a horse. Dedicated motorcyclists understand that a scooter’s harmless countenance is an illusion, that ponies are the cruelest of mounts, and that we are all of us doomed knights on an unforgiving road. It’s understandable that most people find it daunting, or inconvenient, to gear up and saddle up for a coffee on a motorbike, so the wide world is enamored with the scooter for its ease and simplicity; especially women. More on that anon.

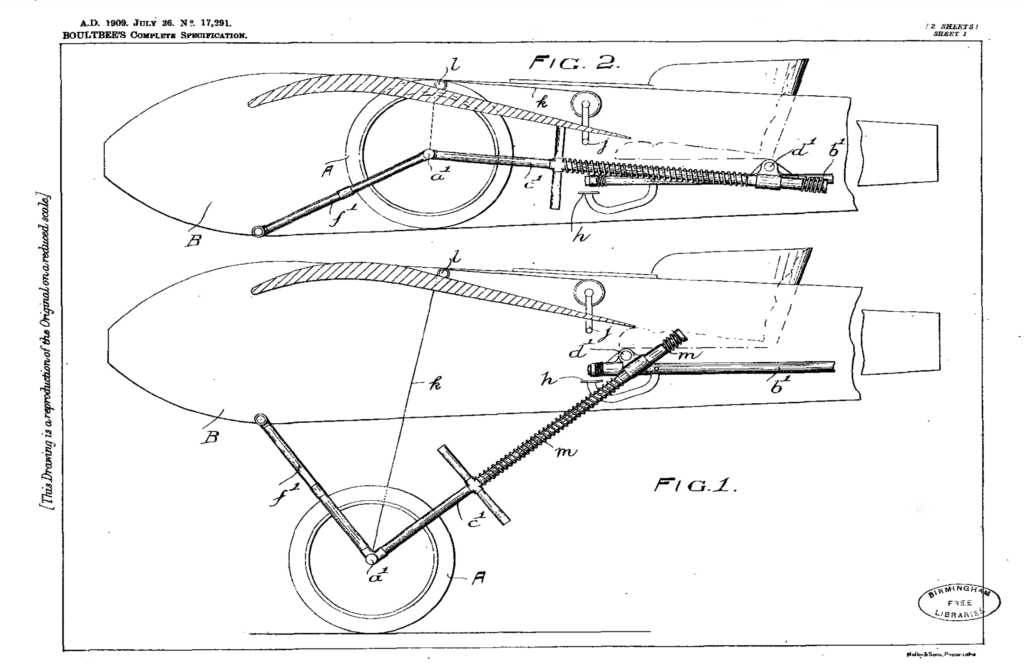

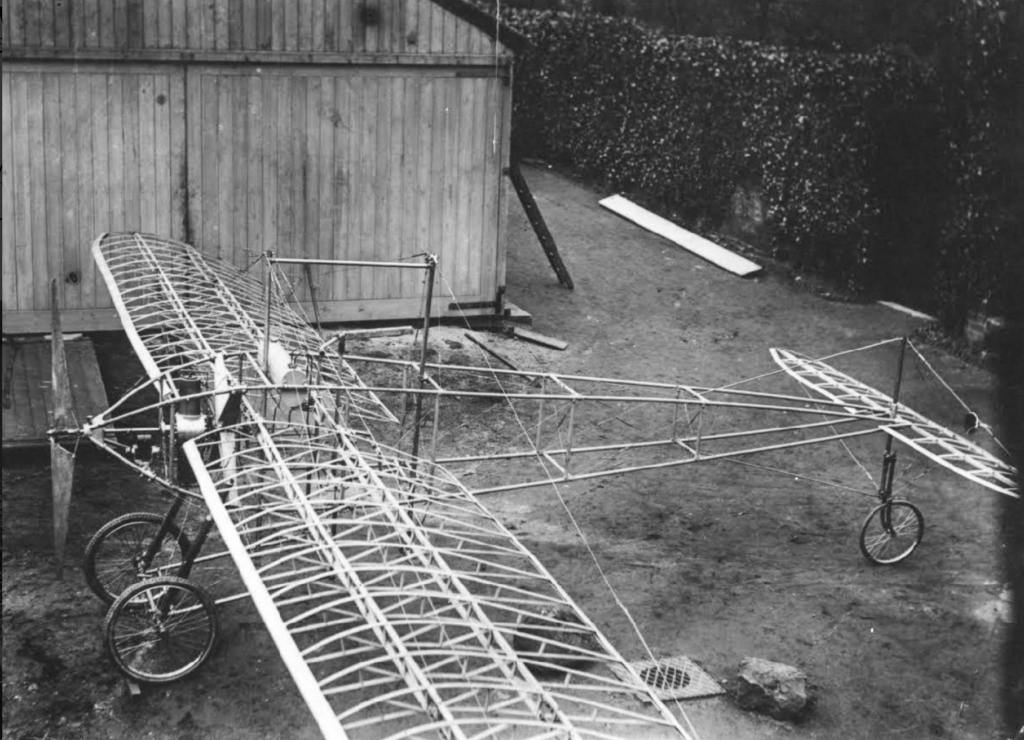

Harold Dalton Boultbee, born 1886 in Eaton, Yorks, graduated from Cambridge in 1908, when young men of a certain economic strata were infected with aero fever. The Wright brothers had proved a kite launched by rubber band and boosted by an anemic motor could sustain flight for a few hundred yards, and changed the world forever. That the litigious Wrights proved more an impediment than a boon to the development of flight was immaterial, as the point was made it could be done, albeit better, and soon was. Boultbee was one of those eager to improve the breed, and in 1909 made his point by patenting the first design for retractable landing gear: it was his first association with wheels on vehicles, but not his last.

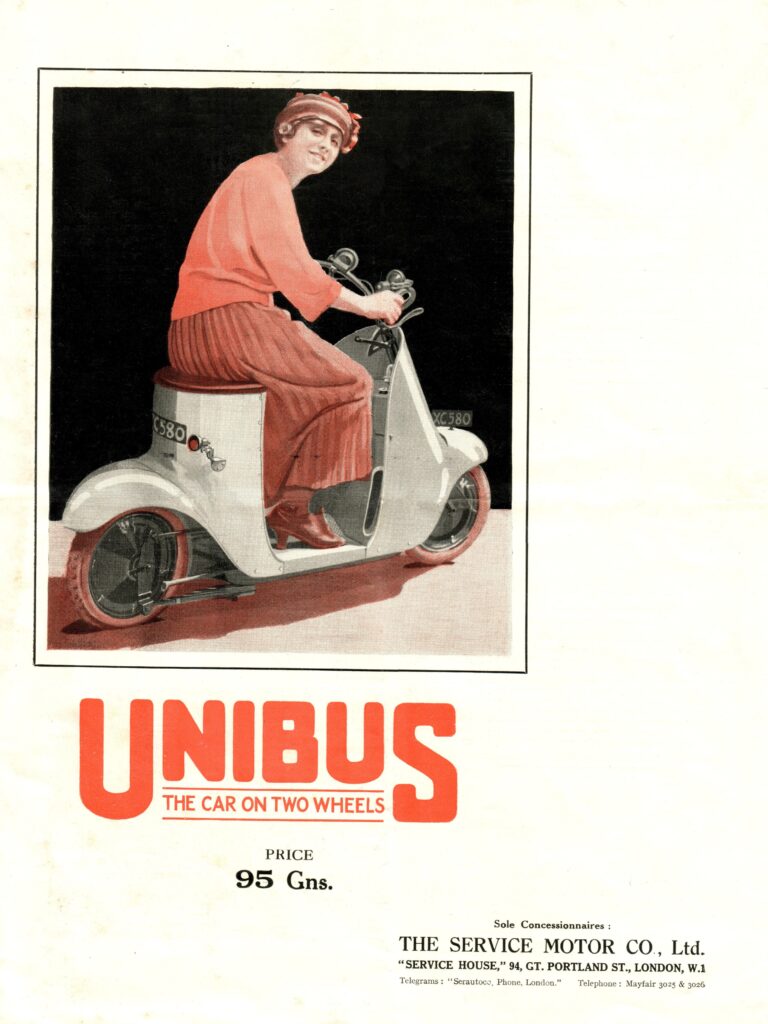

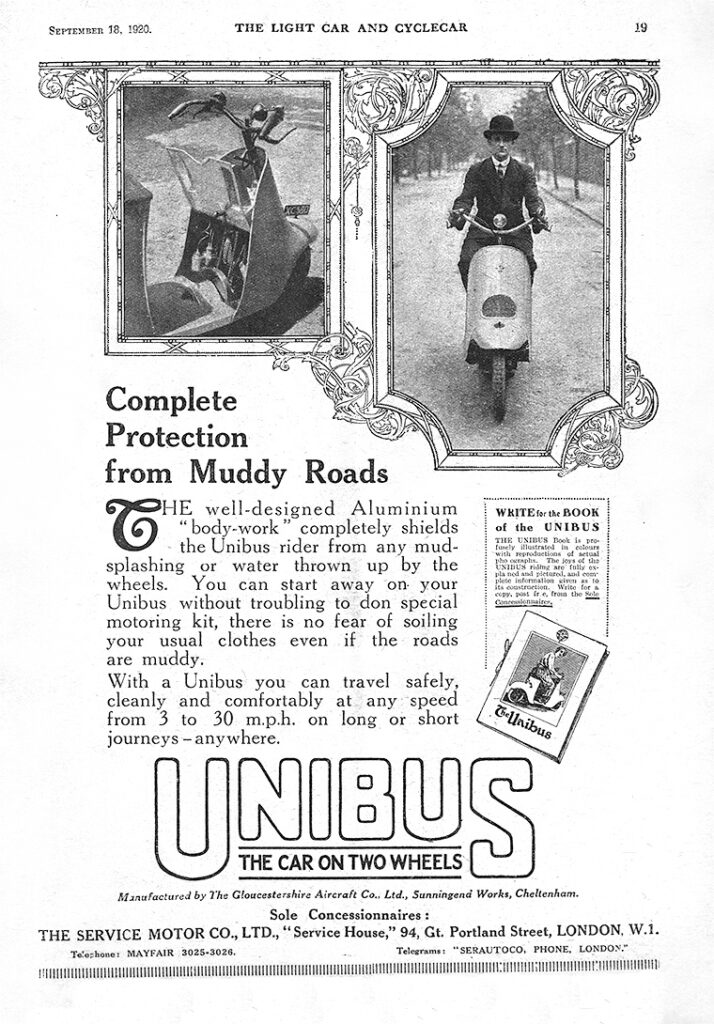

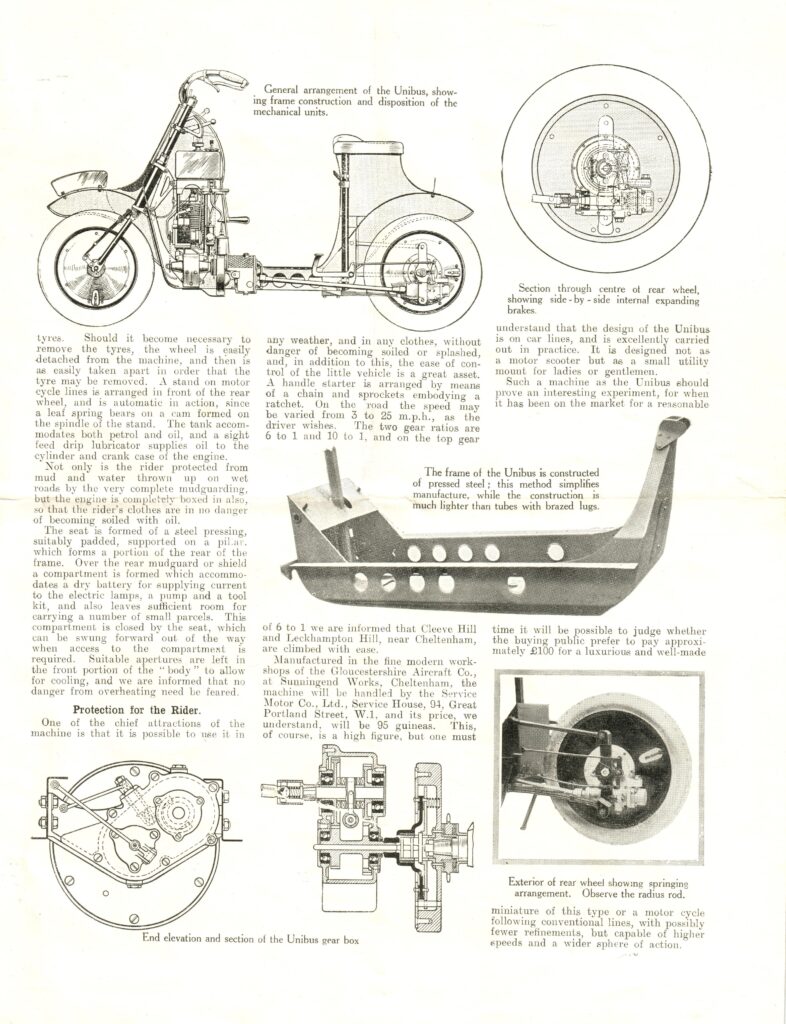

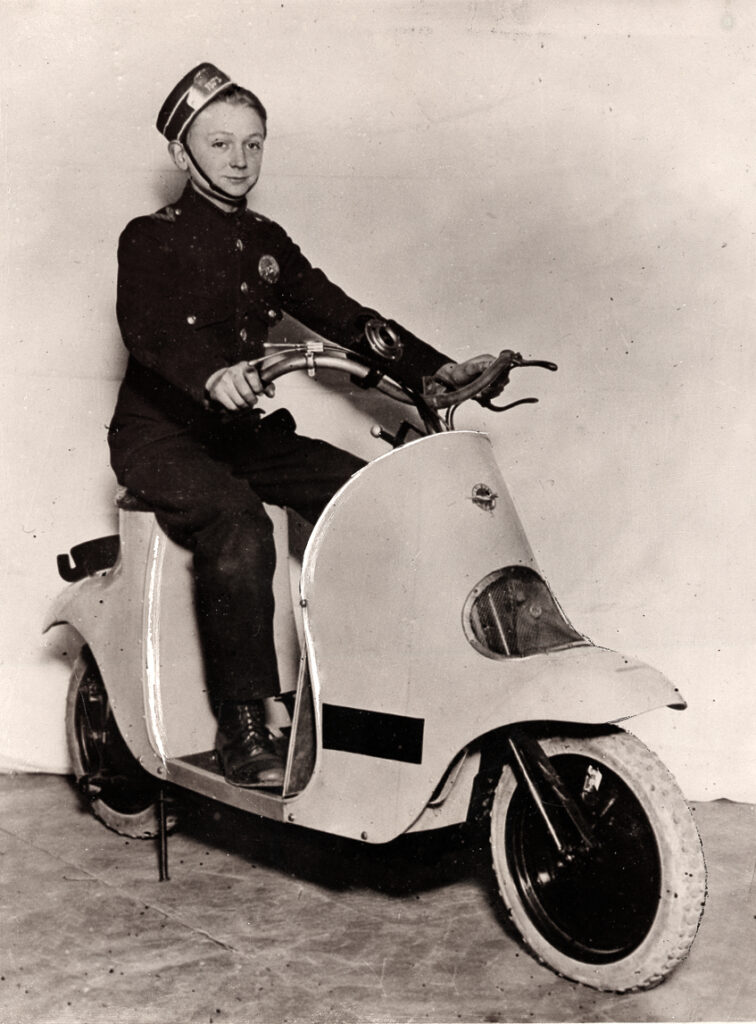

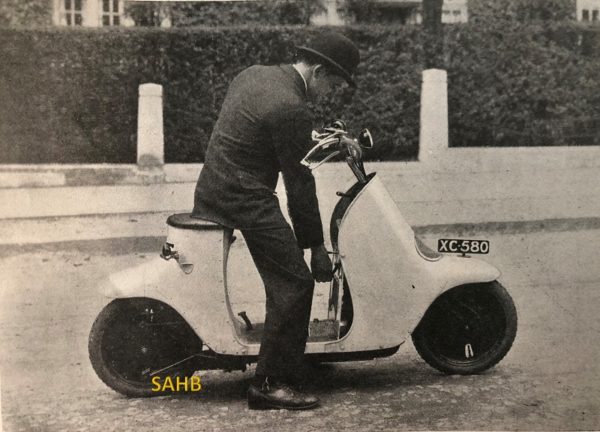

Harold Boultbee’s design for Gloster was unique, and caused a stir when the Unibus was revealed in the Summer of 1920. Dubbed ‘the car on two wheels’, the Unibus was aimed at a genteel clientele, and was priced accordingly at 95 guineas: the same price as the new Brough Superior superbike, and a year’s wages for most working folk. What did one get for such extravagance? Among the most sophisticated two-wheelers on the road, in specification if not in sheer speed (George Brough having comprehensively claimed that space). Technically that meant a simple two-stroke with two-speed gearbox built ‘on automotive principles’, with full springing front and rear plus total bodywork enclosure. The frame was also built on automotive practice, being a sheet steel ‘tub’ with drilled-out horizontal runners and simple cross-panels forming boxes that extended upwards for the steering stem and seat post. The pressed-aluminum bodywork enclosed the whole of the engine, fuel/oil tanks, and mudguard up front, and the flat seat (with copious enclosed cubbys beneath for tools and storage) and rear mudguard combo.

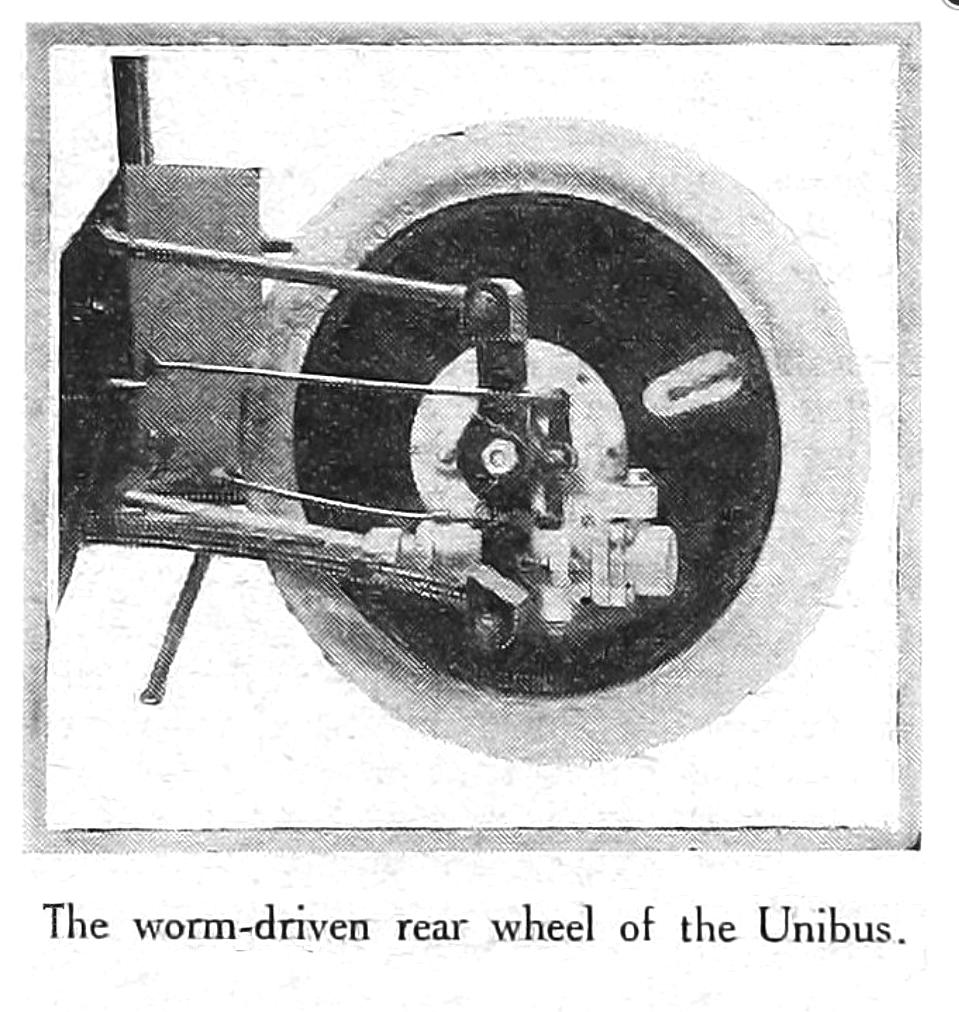

The motive power was a 2½ h.p. (269cc) two-stroke single-cylinder engine set across the frame, which drove through a single dry-plate clutch to a two-speed constant-mesh gearbox set across the frame. The gearbox was connected to a prop-shaft ending at the rear wheel, and used an enclosed worm drive. Perhaps the most unorthodox feature of the Unibus was its dual braking system, with two internal-expanding brakes, one controlled by hand and the other by foot, both acting inside the rear drive housing, rather than the wheel hubs, as later became the norm. Unusually for a motorcycle of the period, the rear wheel was fully sprung, using quarter-elliptic springs attached to a bracket on the worm drive housing, with parallel pivoting arms. The forks were also leaf-sprung, with short fork legs pivoting from the lower steering stem, and the ends of the quarter-eliptics attached to the steering stem and a leading link ahead of the front axle, meaning the fork’s movement was purely fore-and-aft. This was terrible physics, as the wheelbase changed with fork flexure, but in practice (as on the later Neander using the same principles) is surprisingly comfortable and does not spoil handling. Stability was enhanced by using 16” diameter wheels, made of split steel discs (like a Vespa), providing a far more secure ride than a small-wheel machine, and echoing modern practice for more powerful scooters.

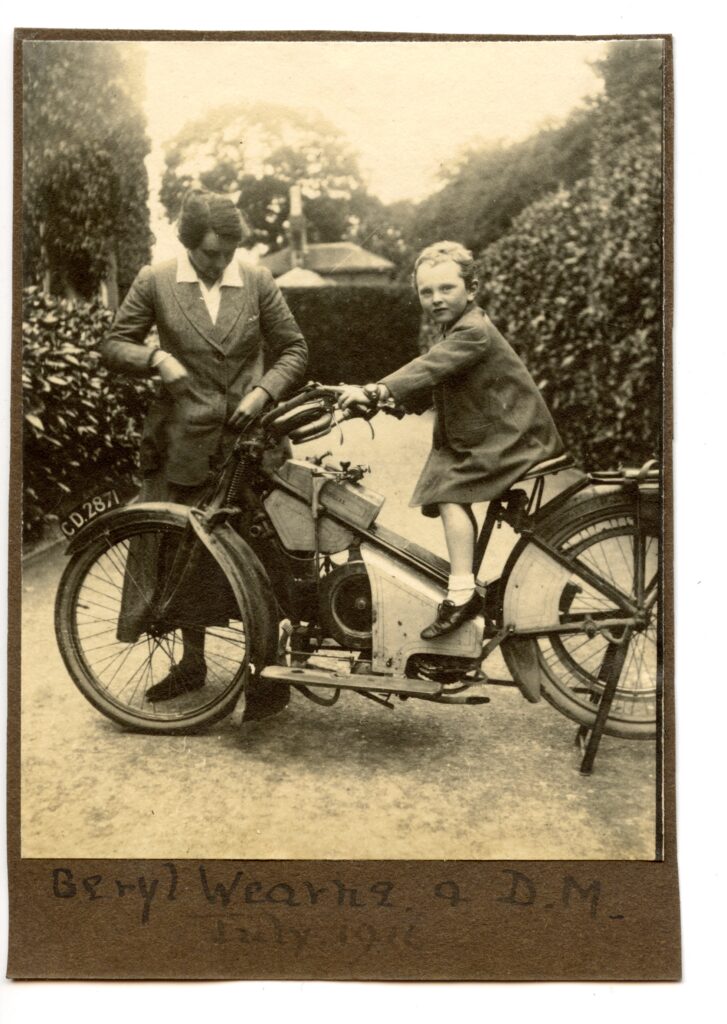

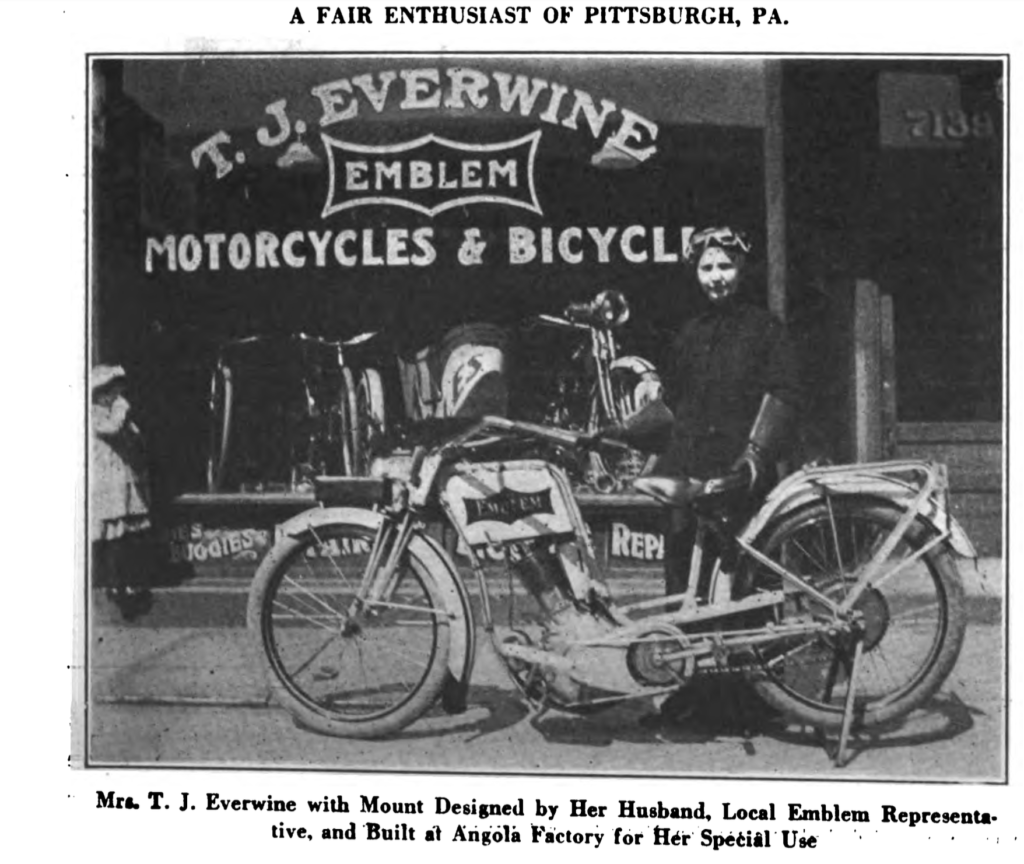

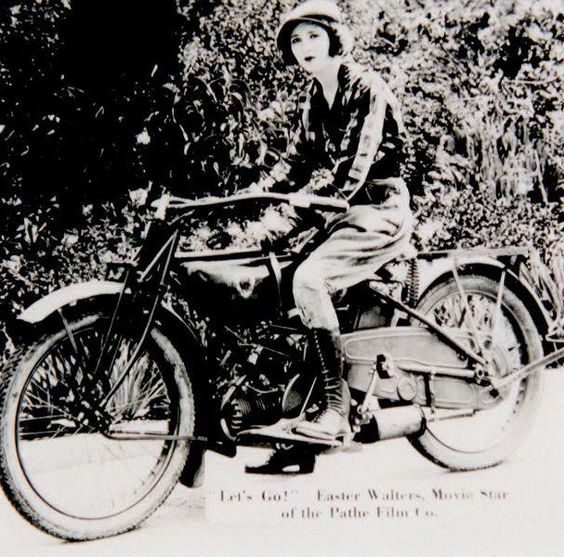

There’s another story to tell around the Unibus and the invention of the scooter: the social history of women on wheels. Two wheelers played an important role in societal changes for women, as the bicycle rolled over Victorian ideas about suitable clothing for women, and their freedom of movement. The Ordinary bicycles’ extraordinary popularity from the 1870s onward had exposed bodices and hoop skirts as simply impossible for a modern lady on the move. In the late 1880s, the smell of freedom wafted around the new Safety bicycle, the original Suffragette conveyance, and in the late 1890s, at the dawn of the motor industry, advertisements featured women riding motorized trikes. By the ‘Noughts and ‘Teens, motorcycles designed especially for women – the Ladies Models – appeared in the catalogues of most British motorcycle manufacturers. The ‘Teens were a heady time for women’s suffrage movement, women were on the verge of gaining the vote in the UK and USA, and the motorcycle industry was eager to exploit what seemed an imminent new market as women took to the wheel.

Once again great piece of 2 wheeled history blast from the past from the pages of Automobile .

Thanks PdO !

So … a lil appropriate fun update to tickle yer fancy ?

Did ya know … that Paris ( as in Paris France … not all the ones over here ) has a Moped / Scooter.. errr … gang ?

Cause yup … much like the Moped Marauders of KCMO I’ve mention in the past …. they do ! Know what they call themselves ?

Hells Accountants …. which when you think about it … is pretty damn apposite …

😎

FYI ; to all you suburban urban hipster wanna best … THAT ( the club/gang’s name ) is genuine Irony . Not all that pretentious crap y’all still spew out thinking yer ironic .

So … on the subject of women on motorcycles . Something all you misogynists out there question criticize and ponder yourselves more oaten than not into a drunken stupor .

But … do you know why women not only adapted to motorcycles as quick as their male counterparts … more often than not getting there first … exceeding male accomplishments etc et al ?

The safety bicycle … which was the gateway to independence and freedom for women across what was a very limited America back in the day .

And jumping on a motorcycle ? Barely an effort seeing as how the early motorcycles were just motorized bicycles . And so on it goes on … till the present day …

Sorry all you macho misogynists … you lose

And now you know !

😎