Moto Major: Italy Reinvents the Motorcycle

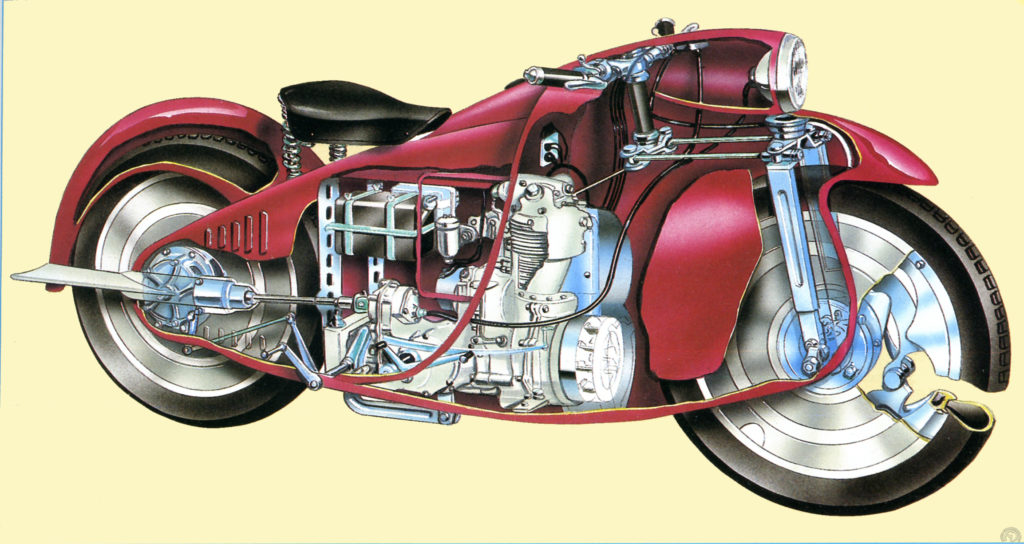

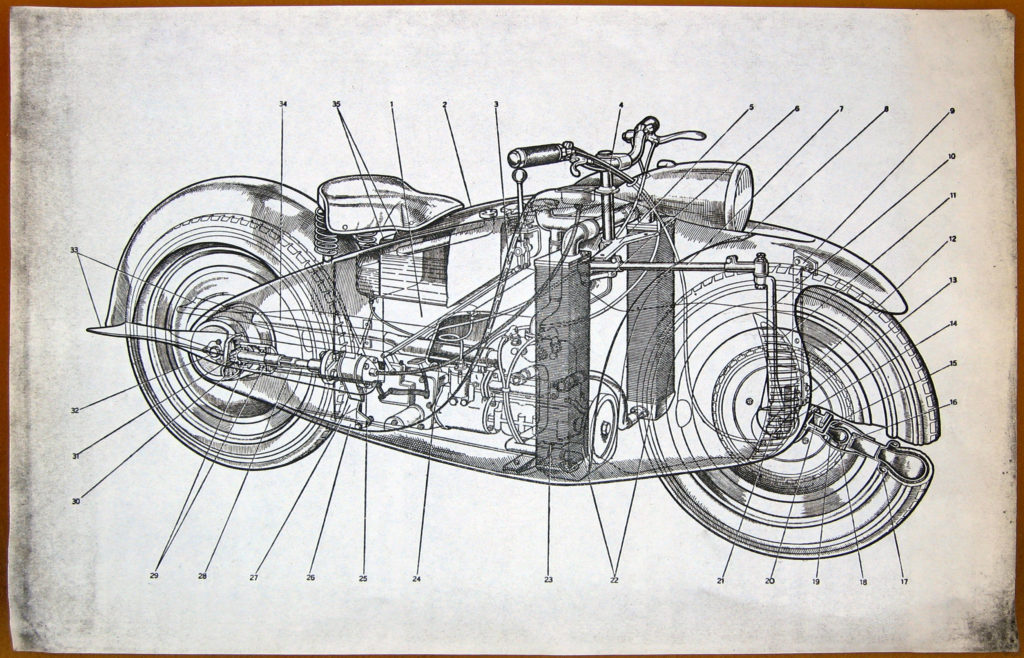

During the long history of the motorcycle, very few designers have managed to realize exceptional fantasies as production motorcycles: they almost always remain as prototypes, left to us as beguiling 'what ifs'. Such is the fate of the fantastic Moto Major, created in 1947 by Piedmontese engineer Salvatore Maiorca, which never ceases to create a stir. The Moto Major has been featured in BikeExif, voted Best of Show at the Concorso Eleganza Villa d'Este in 2018, and is currently presented (from this November 29, to March 30, 2020) at the National Museum of the Automobile in Compiègne (France) as part their exhibit 'Concept Car: Pure Beauty.'

The Moto Major's 350cc engine was developed in collaboration with engineer Angelo Blatto, who had significant experience in the 1920s and '30s at Aquila, Augusta, OMB and Ladetto & Blatto. It's an aero-engine inspired four-stroke, with a turned steel cylinder and an aluminum cylinder head. A fan at the end of the crankshaft provides cooling by forced air, while the long crankshaft drives a four-speed gearbox controlled by footshift, and a shaft final drive. The kickstarter is removable, as on the first Honda 1000 Gold Wing of 1975.

Engine: 4-stroke vertical single-cylinder engine with longitudinal crankshaft / Turned steel cylinder, aluminum cylinder head / Forced air cooling / 349.3cc (76 x 77 mm) / 14 hp @5200 rpm / Dell'Orto carburettor / Lubrication by oil circulation and double pump / Battery-coil ignition.

Transmission: Dry multi-plate clutch / 4-speed gearbox with footshift / Transmission by shaft and bevel gear final drive

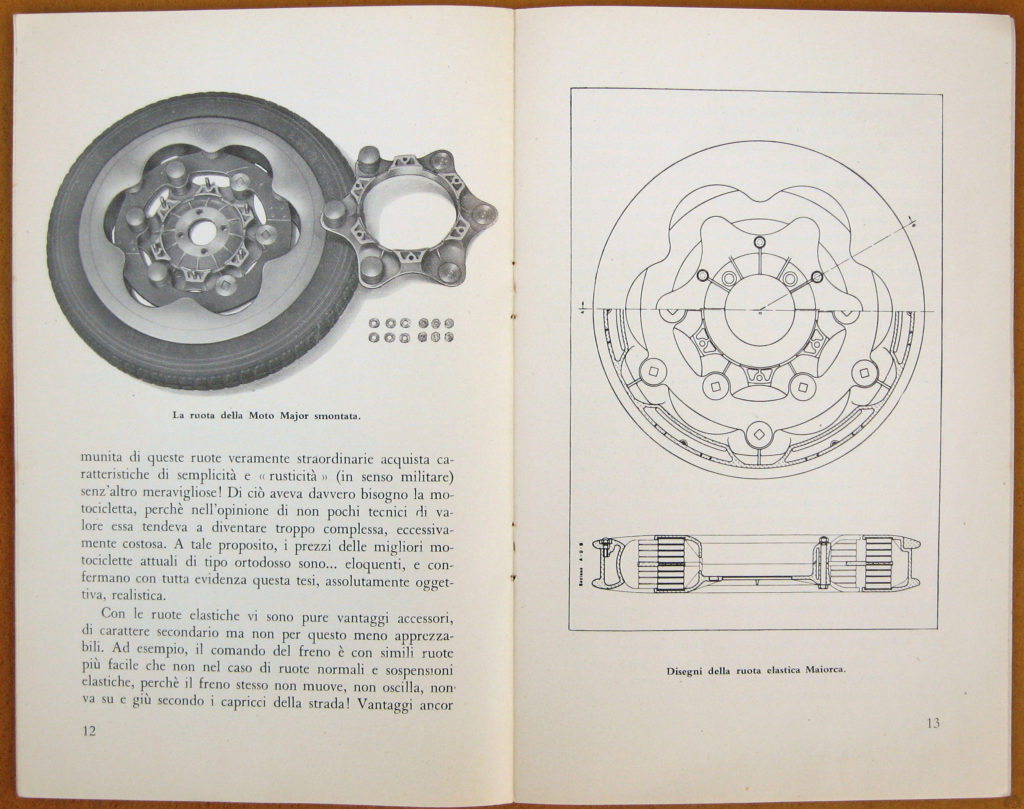

Chassis: Self-supporting sheet steel body / Spherical hub and rod-controlled steering / 19" elastic wheels with 24 deformable rubber-block suspension

Dimensions and Performance: 150 kg in running order (43 kg engine) / Tank 13 liters / 105kmh (63mph)

Legends of Montlhéry at the Cafe Racer Festival: Part 2

By Francois-Marie Dumas (translated/expanded by Paul d’Orléans)

Café Racer magazine (France) hosts its annual Café Racer Festival at the Montlhéry autodrome on the third weekend of June, and it remains the sole motorcycle-only event held at that historic track. Other events like Vintage Revival Monthléry are mixed car and bike, so the CRF is something special [but watch our film on Montlhéry here!]. This year the event was made extra-special by the efforts of French moto-journalist and historian Francois-Marie Dumas (a Vintagent Contributor), who organized an exhibition of simply remarkable machines with racing and record-breaking history at or near the track. Francois-Marie kindly provided us with photos from the Café Racer event, plus historic photos of these motorcycles racing and taking records at Montlhéry and nearby Arpajon in their day.

Here's a second batch of remarkable machines exhibited this year at the Festival:

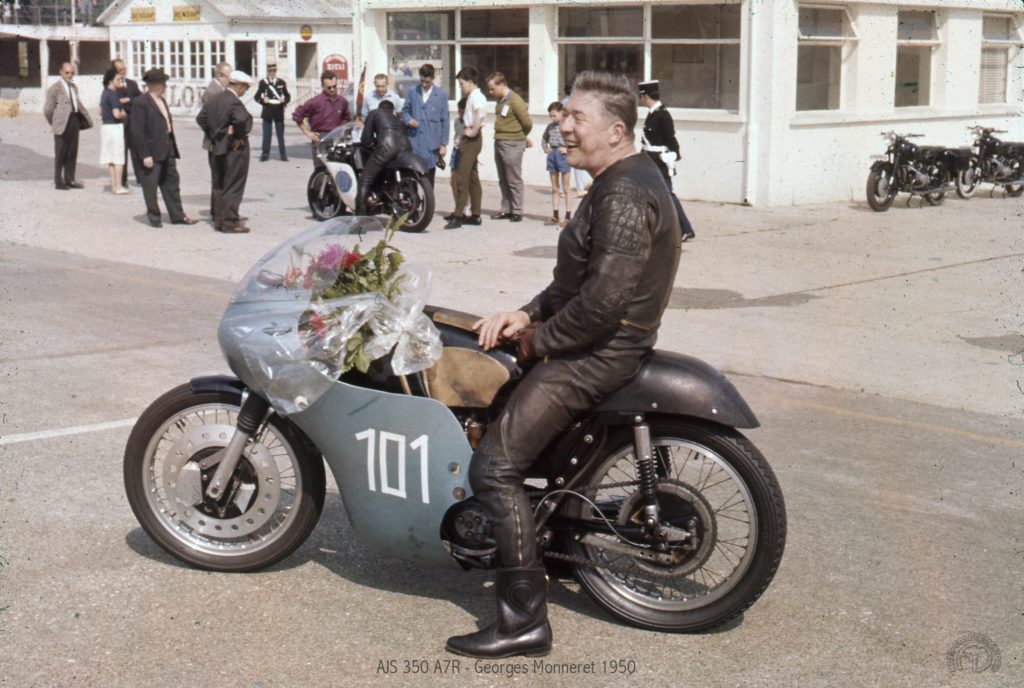

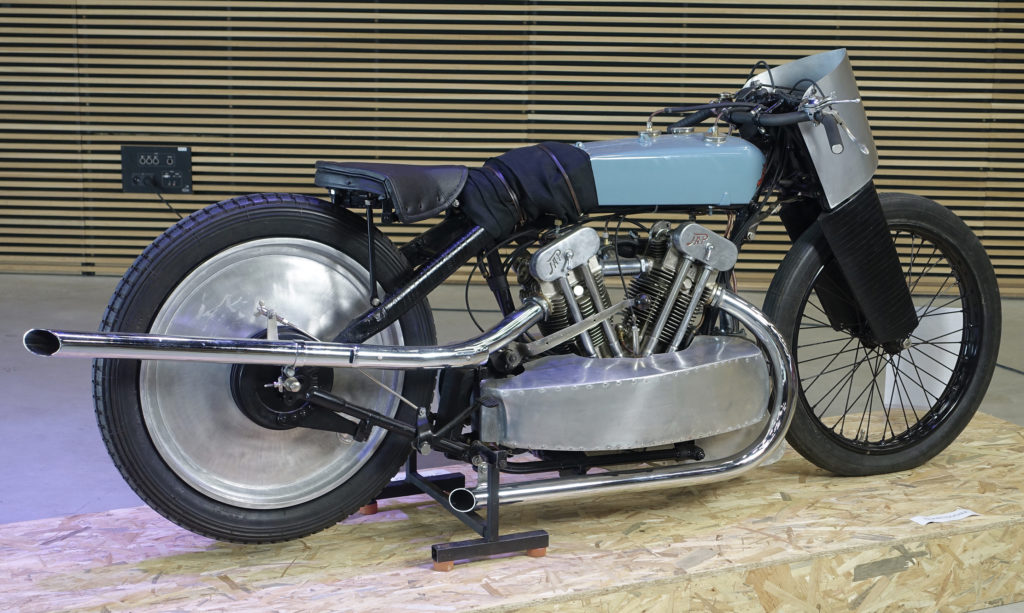

1935/1952 Koehler-Escoffier 'Monneret' 1000cc

Collection: Henri Malartre Museum, Lyon (France)

1937 AJS R10 500cc

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

1937 Gnome & Rhône 750 Type X with Bernardet 'Avion' sidecar

Collection: Jean-Claude Conchard (France)

1938 Nougier 175cc DOHC

Collection: Stable Nougier (France)

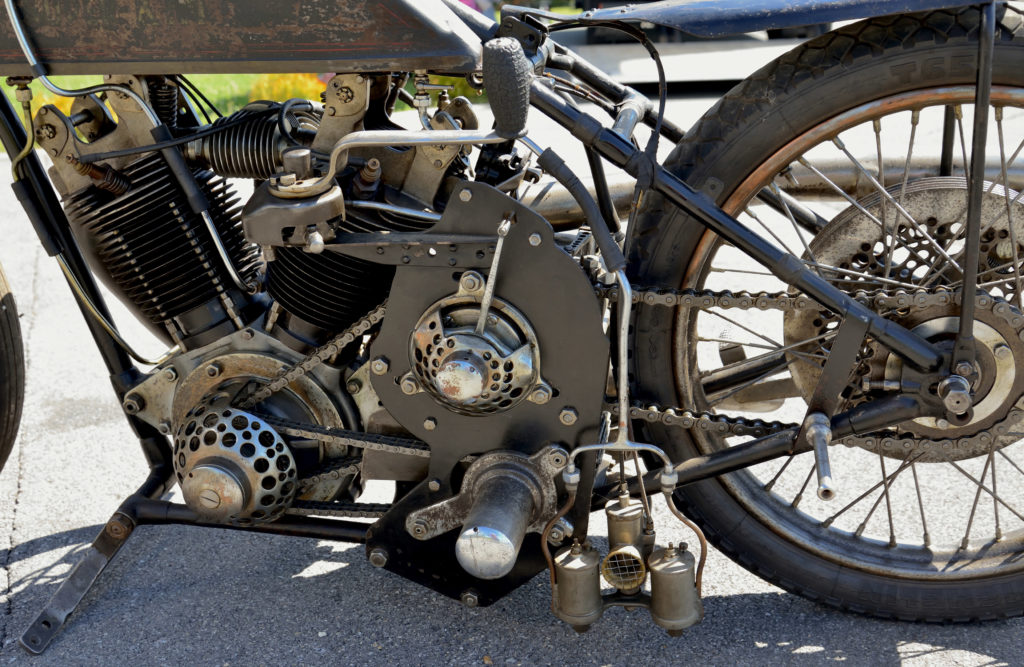

Jean Nougier was an engineer who spent his pre-war career upgrading French race machines with advanced overhead-camshaft cylinder heads, and other improvements to make them vastly more competitive. In 1935 he built a 175cc double-overhead-camshaft racer based on a Magnat-Debon, that so impressed the Director of the Magnat-Debon/Terrot factory (Jean Vurpillot), he supplied Nougier with raw castings of magnesium crankcases, and aluminum cylinders and heads. The hot engine of the new 125 DOHC racer built by the Nougier brothers for 1937 looks very much like Magnat-Debon's 175 LCP from 1935, but everything inside was different: the crankshaft was homemade and the fins of the barrel are square, a rarity at the time. A cascade of gears drives the camshafts.

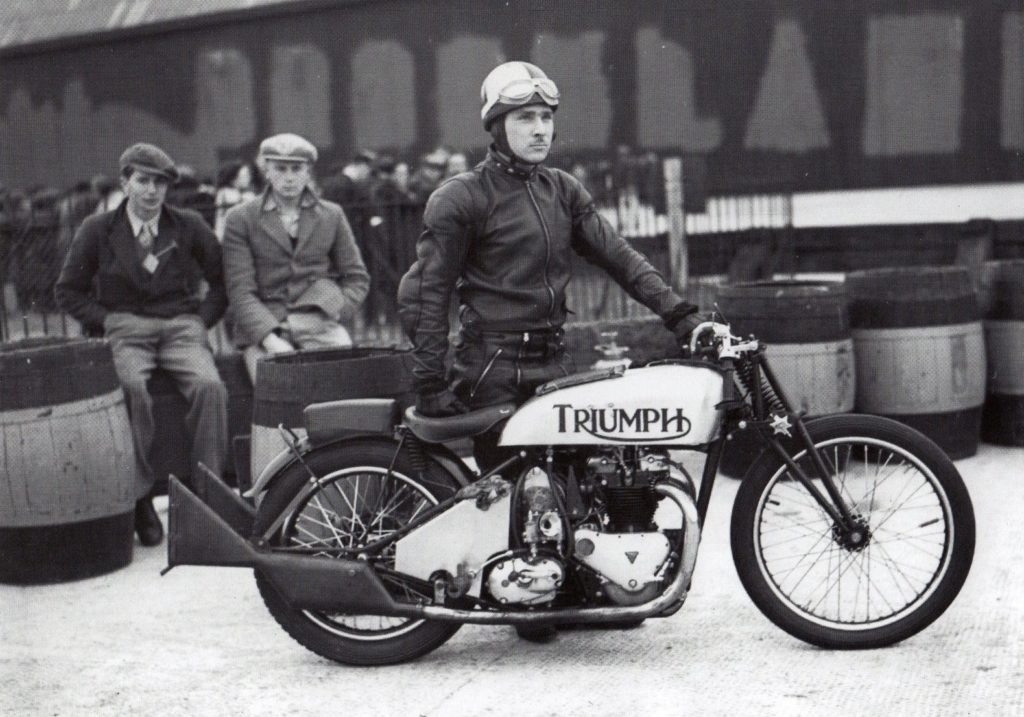

1938 Wicksteed-Triumph Speed Twin supercharged

1949 Triumph Thunderbird 6T 650cc

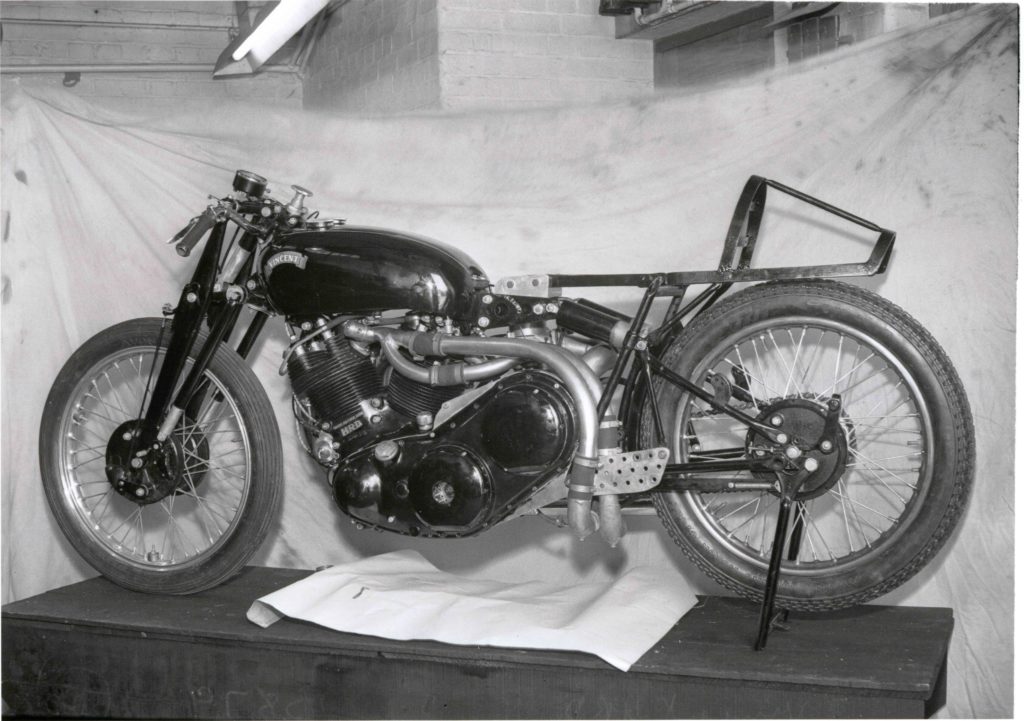

1950 Vincent 'Dearden' Supercharged Black Lightning 1000cc

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

1954 BMW RS54 500cc streamliner with sidecar

Collection: BMW Group Classic (Germany)

1956 NSU SportMax 250cc

Collection: Top Mountain Motorcycle Museum - Hochgurgl (Austria)

Legends of Montlhéry at the Café Racer Festival: Part 1

By Francois-Marie Dumas (translated/expanded by Paul d'Orléans)

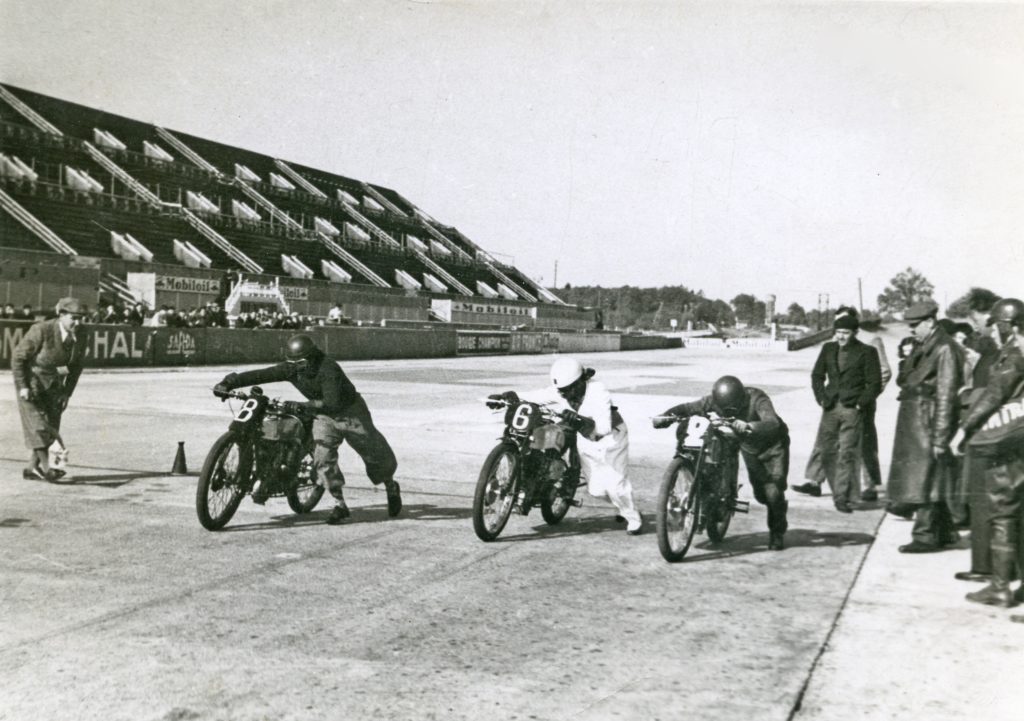

Café Racer magazine (France) hosts its annual Café Racer Festival at the Montlhéry autodrome on the third weekend of June, and it remains the sole motorcycle-only event held at that historic track. Other events like Vintage Revival Monthléry are mixed car and bike, so the CRF is something special [but watch our film on Montlhéry here!]. This year the event was made extra-special by the efforts of French moto-journalist and historian Francois-Marie Dumas (a Vintagent Contributor), who organized an exhibition of simply remarkable machines with racing and record-breaking history at or near the track. Francois-Marie kindly provided us with photos from the Café Racer event, plus historic photos of these motorcycles racing and taking records at Montlhéry and nearby Arpajon in their day. Let's hope such exhibits become a new tradition at the Festival! Below is the story of some of the amazing bikes exhibited.

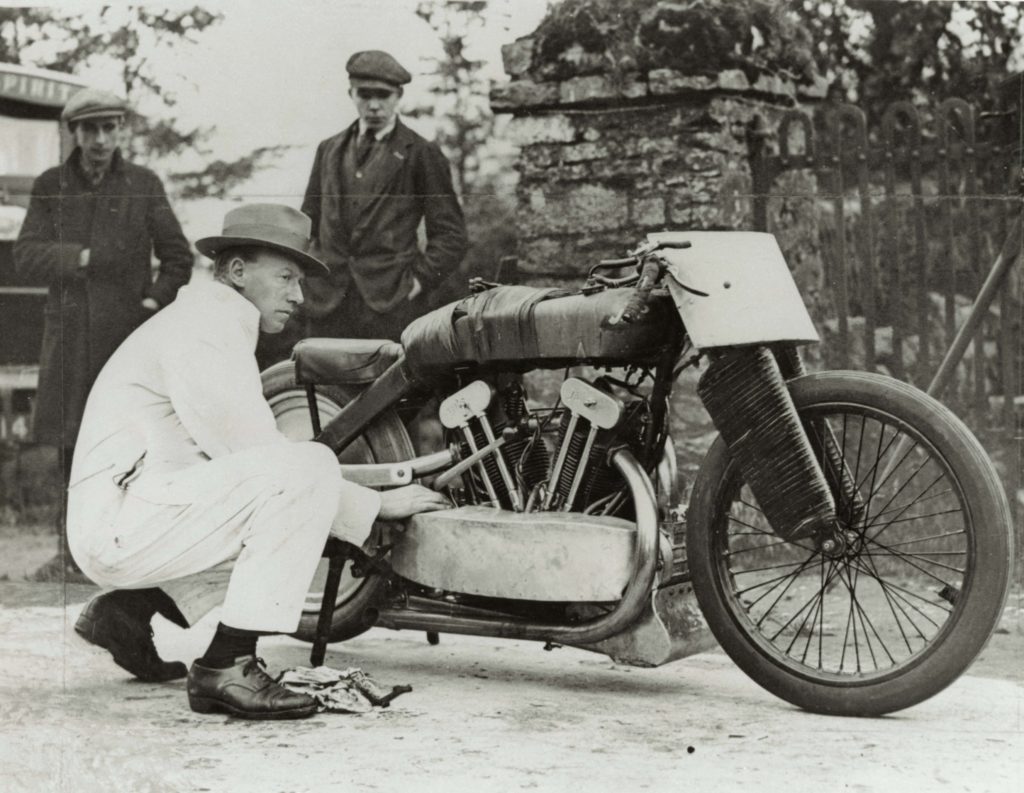

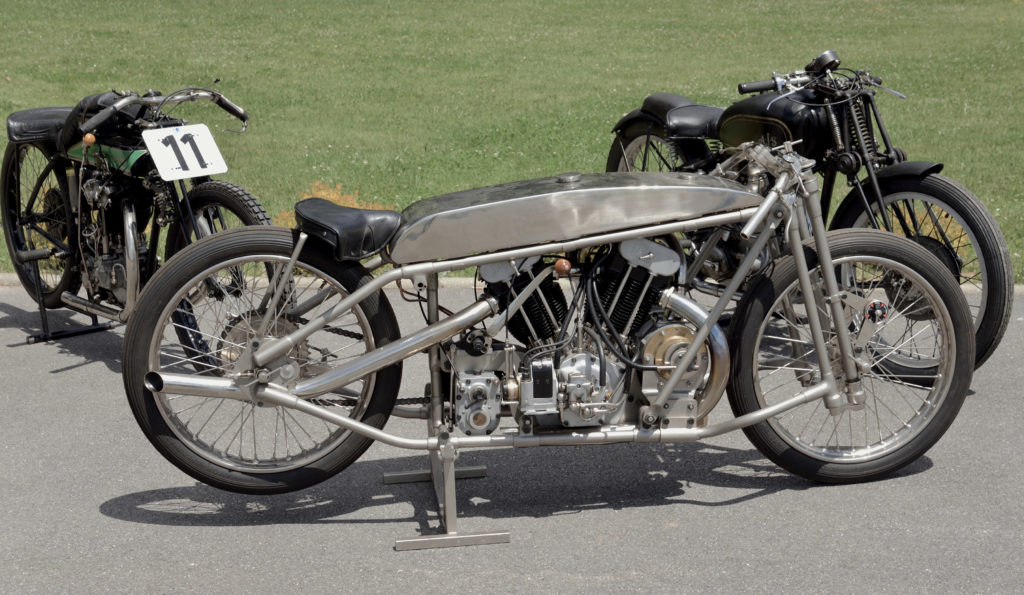

1924 McEvoy-Anzani with 8-Valve 1000cc Anzani engine

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

1924 New Imperial with 350cc JAP DOHC.

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

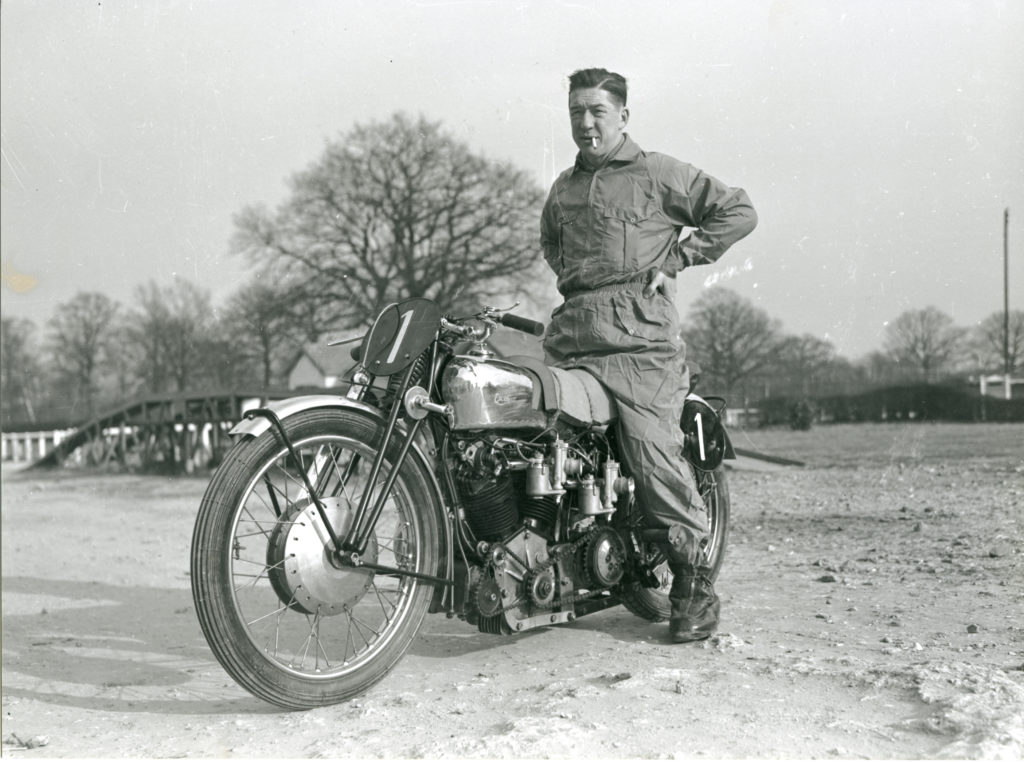

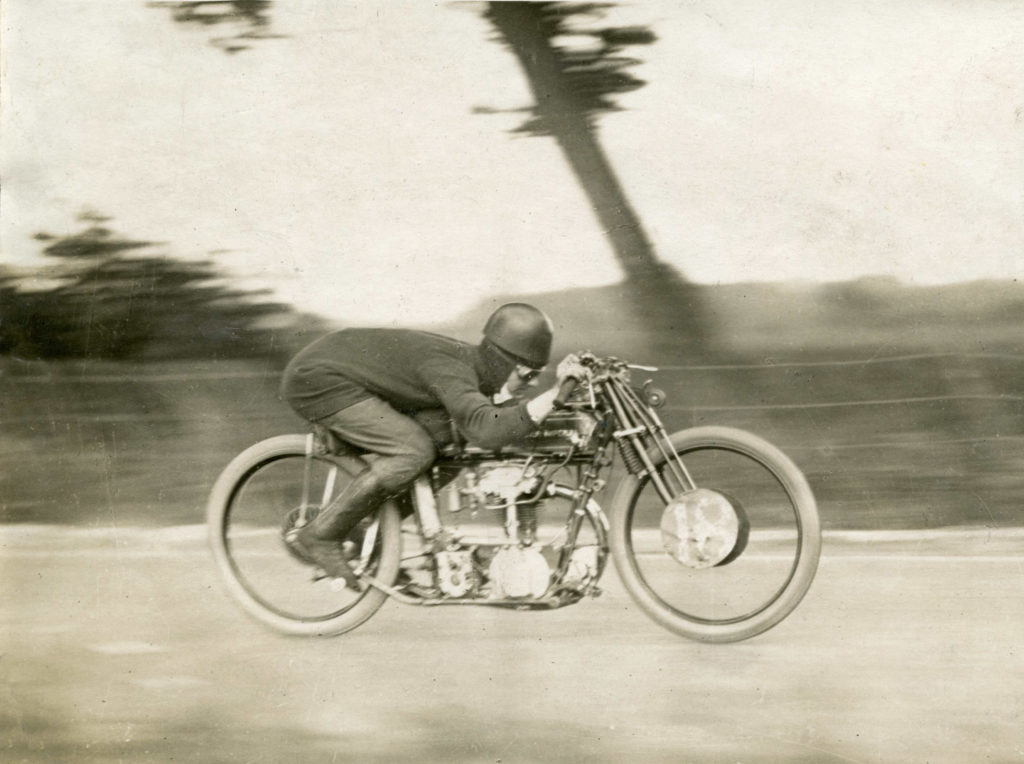

1926-30 Zenith-Temple with Supercharged 1000cc JAP

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

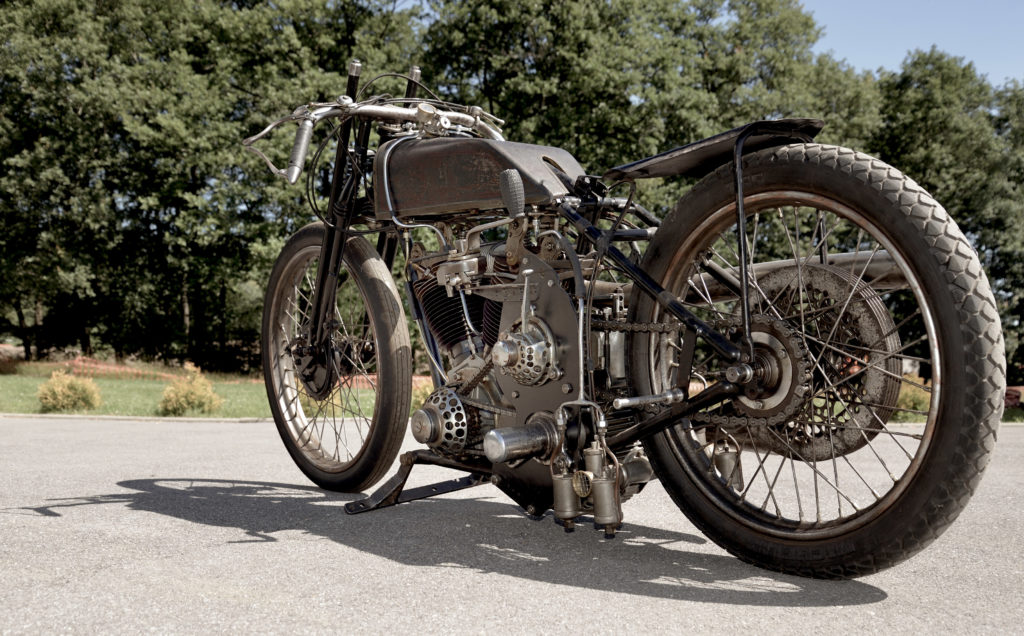

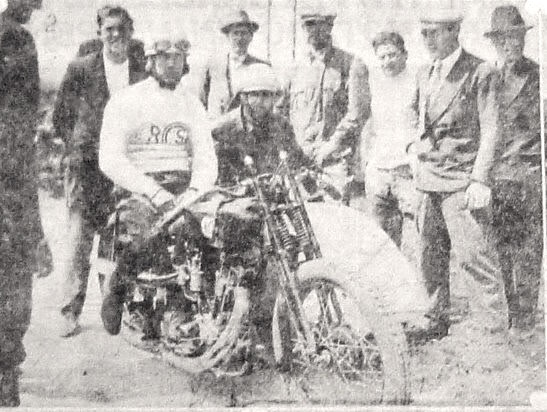

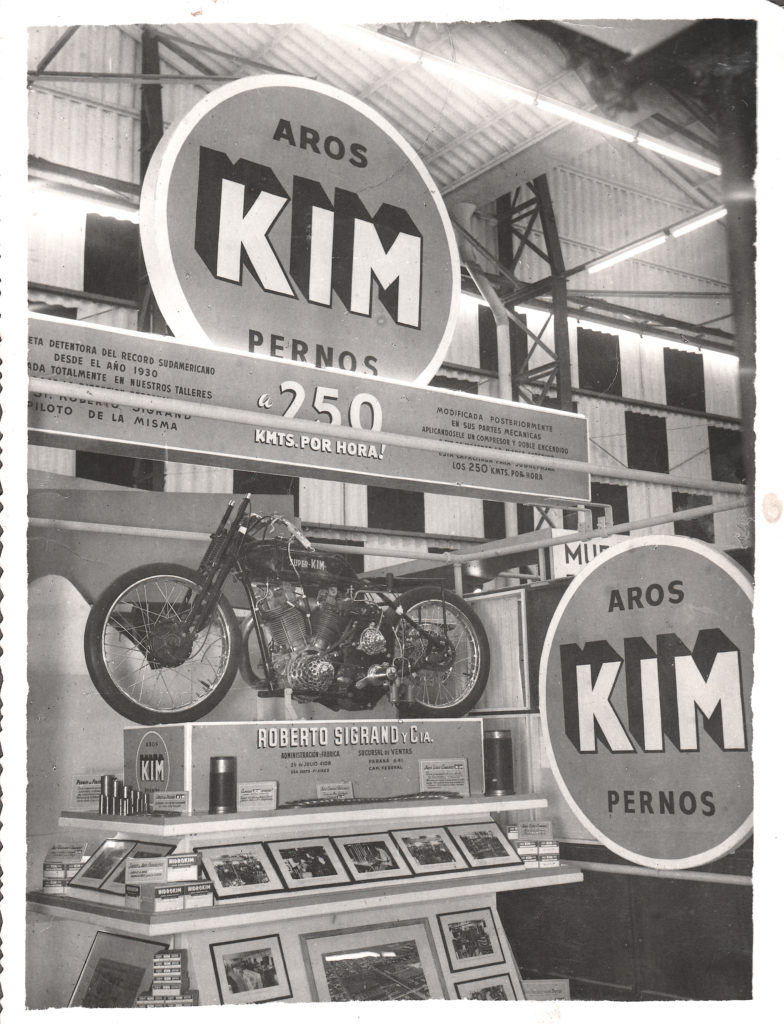

1925-30 Zenith 'Super Kim' with Supercharged JAP 1700cc

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

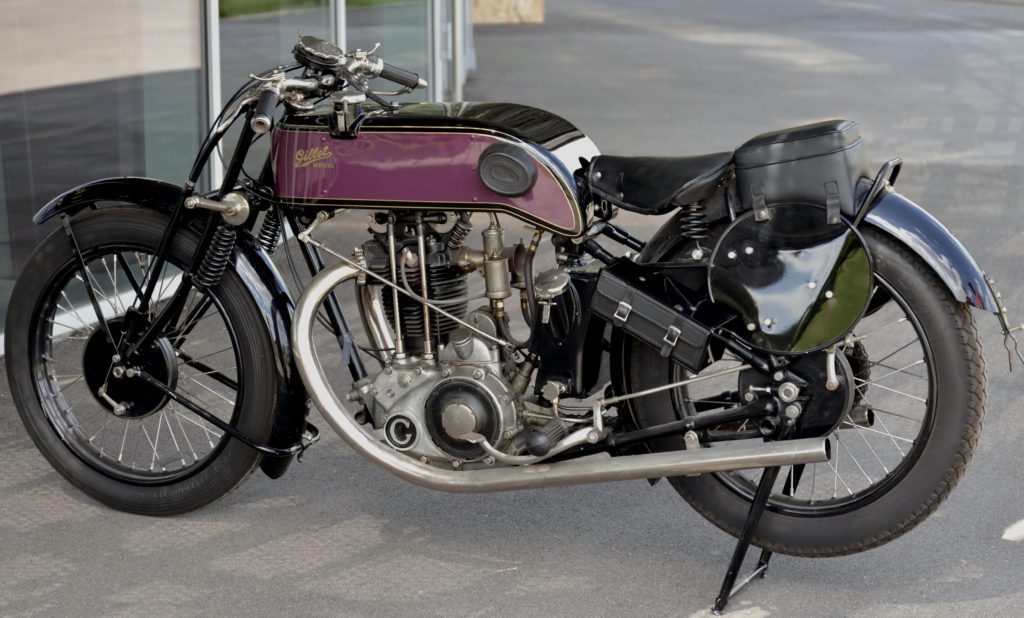

1928 Gillet-Herstal 600R.

Collection: Yves Campion (Belgium)

It's impossible to imagine an exhibition on Montlhéry's motorcycle records without a Belgian representative, because FN, Saroléa and Gillet, three brands established with Herstal-Lez-Liège, took plenty of records at the Autodrome.

1930 OEC-Temple with Supercharged JAP 1000cc engine

Collection: Motor Sport Museum Hockenheimring (Germany)

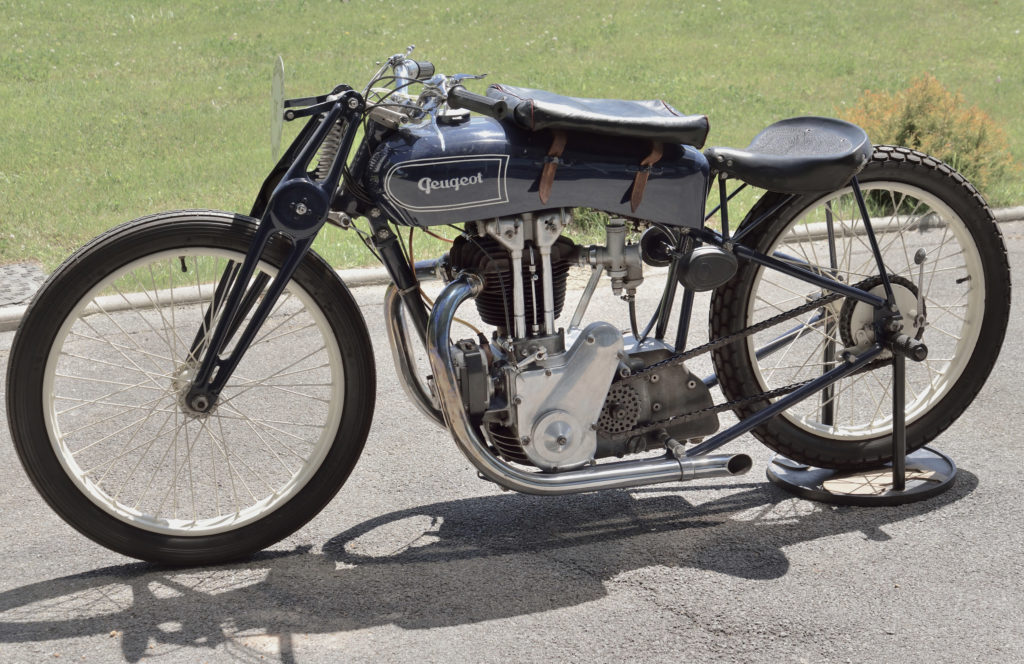

1934 Peugeot 500cc P 515 "World Record"

Collection: Adventure Peugeot (France)

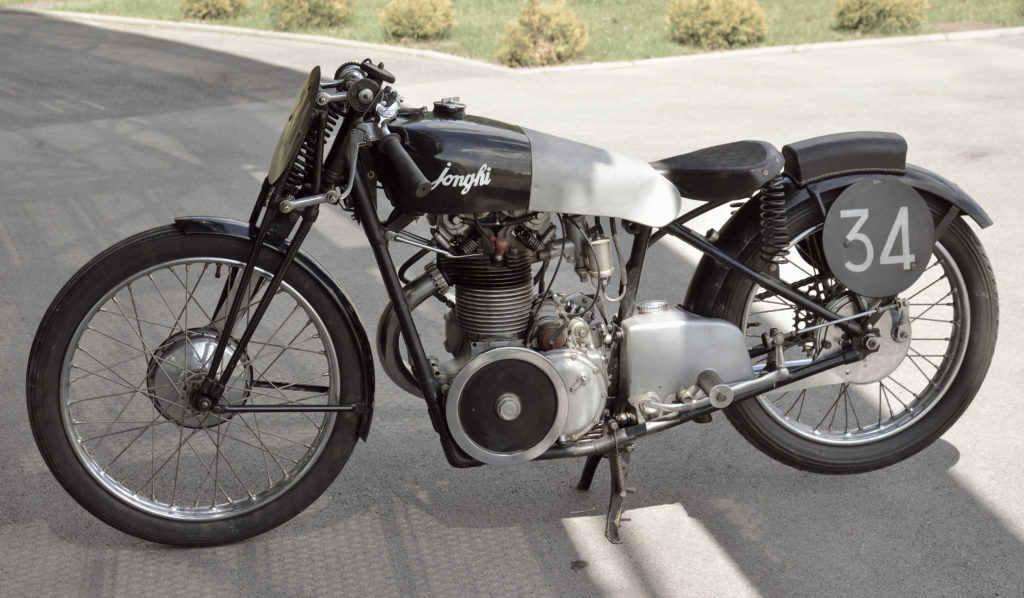

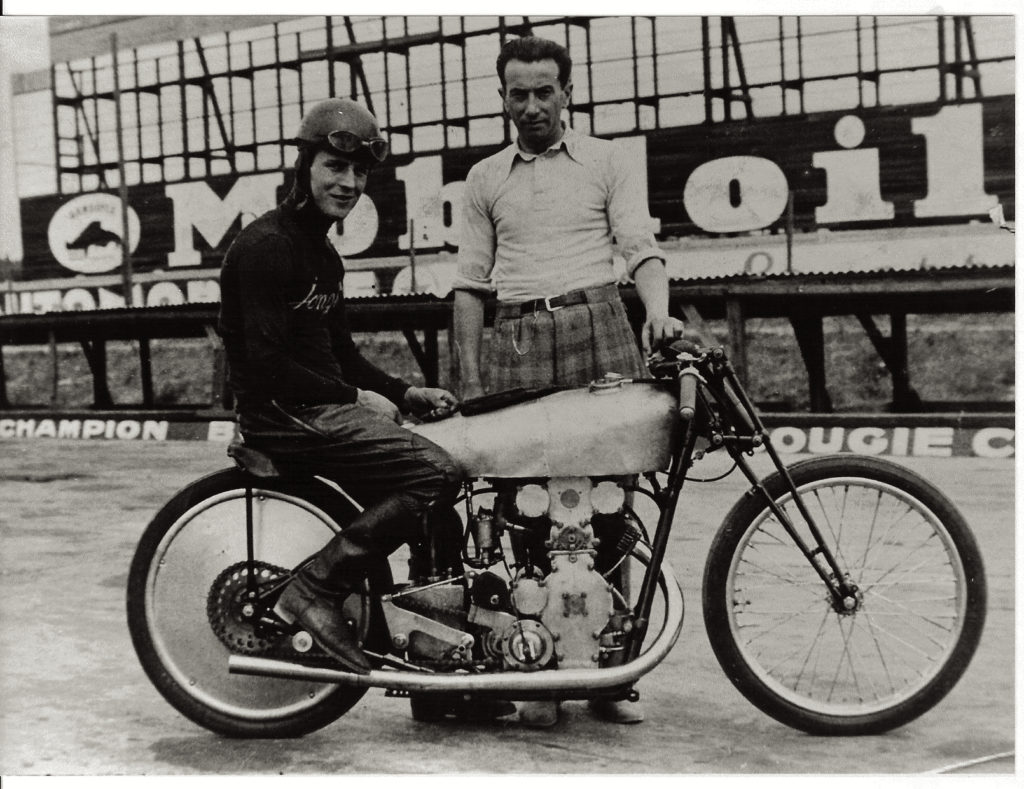

1934/38 Jonghi 350 DOHC

Collection: Stable Nougier (France)