The recent Age of Irony took a scant view of the Future’s unbridled optimism; forward-looking, visionary projects, from architecture and urban planning to product and technology design, had shown a fundamental flaw in the Future, a deep contradiction within its gleaming heart; the Future was not for everyone. Or, if it was planned for everyone, these envisioned socialist utopias smelled totalitarian, and had proved, when actually built, to be failures on a grand scale.

The tall housing projects with surrounding parkland, so geometrically beautiful in Le Corbusier’s ‘Plan Voisin for Paris’, had been built on a smaller scale in New York and Paris, and by the 1970s had become dangerous slums. Critic Jane Jacobs rightly assailed such out-of-touch and un-human urban planning, and her influential analysis of what makes cities healthy was groin-kick to Future planning. Whether homespun like Frank Lloyd Wright, socialist like Corbusier, or outright fascist like Antonio Sant’Elia, rigorous urban planning looked bitterly dystopian by the 1980s – we had seen the Future; it wore jackboots, and didn’t age well.

Luigi Colani is an old-school future-dreamer, the type of hyperconfident character whom skeptics disregarded during the ironic 1980s. His career as an industrial designer began in 1953, at the special projects division of McDonnell-Douglas aircraft, after studying aerodynamics at the Collége de Sorbonne. During the late 1950s and early 60s, he worked with several Italian auto makers (Fiat, Alfa Romeo, etc), creating special bodies and winning design awards.

By the 1970s he was famous for his increasingly outrageous organic shapes, which he calls ‘biodynamic’, in imitation of Nature’s graceful forms, and designed products ranging from tea sets and cutlery to heavy articulated trucks and aircraft. “Soft shapes follow us through life. Nature does not make angles. Hips and bellies and breasts — all the best designers have to do with erotic shapes and fluidity of form.”

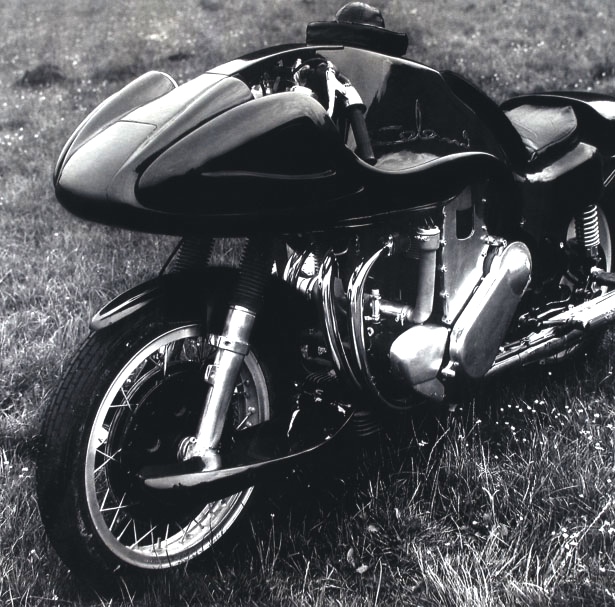

Feeling underappreciated in Europe, he relocated to Japan in 1982, and flourished, producing both ‘improbable’ designs for vehicles, and very up-to-date products, including the first ‘ear buds’ for Sony (1989…long before the iPod), and the first ergonomic body for a camera (the Canon T90 of ’86), along with uniforms for SwissAir and the German police. Among his many transportation projects, Colani has long dabbled with motorcycle design, from sculptural shape-studies to creative bodywork over incredible machines, most notably the Münch Mammut and Egli-Kawasaki – an incredible turbocharged fire-breather with 320hp, which set the 10km flying-start speed record in 1986.

Colani doesn’t consider himself a designer; “I am a three-dimensional philosopher of the future.” With the necessary combination of third-person egotism and unbridled imagination, Colani developed from an industrial design innovator to a full-blown psychedelic guru of flowing organic shapes for every application. While he sounds ripe for ironist derision, Colani’s work is enjoying a resurgence after a long period of embarrassed silence from industrial designers.

After decades of developing, envisioning, and championing flowing organic shapes, the Future has finally caught up with Colani, and he is enjoying another day in the sun. The practical development of computer 3D modeling, and more recently the rise of rapid prototyping systems, has given ‘Colani’s children’ – Zaha Hadid, Ross Lovegrove, and the new generation of organic-shape disciples – the kind of real-world relevance unthinkable in the 1960s and 70s, when Colani’s work seemed utterly fanciful, even self-indulgent. Now superwealthy backers and attention-hungry governments actually build structures which seemed impossible a mere 20 years ago. Colani’s future has arrived.

Having followed his work for decades I’d be the first to stand in defense of the viability of Colani’s bats**t crazy ethos and design . Problem is Paul despite all your optimism no one is using any of the concepts and designs he’s created despite CNC etc etc . In other words all the technology in the world still hasn’t allowed the world to catch up with Colani’s near madness (in the best of ways ) visions and concepts for the future .

So what is the real problem you may ask ? Our Twitterholic addiction to technology for technology’s sake and an even worse addiction to recreating the past rather than looking forward to the future . One look at say EICMA , Geneva etc makes that very clear . When it comes to transportation at this point in time … there is no future .. only a clinging to a past most do not so much as comprehend never mind remember

And much as it pains me to say this ..as the likes of OddBike etc have stated so clearly .. motorcyclists and motorcycling … are the most guilty .. with automobiles running a very close second

PS; Fact Check Time . Read the history and biographies ( skipping his egomaniacal autobiography ) Frank Lloyd Wright was anything but …. homegrown .

I agree that buyers of most consumer products are very conservative, especially high-value items like motorcycles or cars. It poses some interesting questions about design, such as: is there a need for continual updating of successful designs, or is that merely Capitalism’s requirement to continue selling things to people over and over again? Are certain designs ‘right’ for people, which makes them classics and thus of continual appeal? Etc.

We’ve yet to see how 3D printing changes product design; my daughter worked for a 3d metal and glass-printing startup for a time, and it became clear the market and technology just aren’t there yet for a viable 3D-print business. Colani’s designs work for injection-molded plastics; as he doesn’t design on a computer (as far as I know), the baroque intricacies of 3D printing are unnecessary for his work. But, quite a few of his designs have gone into production. He’s not ubiquitous like Jonny Ive, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t a success.

Regarding Wright; he is ‘homegrown’ in the sense of being from the USA, my intended meaning. My mentor at University was Reyner Banham, and I studied architectural history extensively, along with political theory, art, and environmental studies. So yes, I’ve read up on Wright, and Sant’Elia, and Corbusier, etc…

Someone I heard describe modern motorcycle design as jet skis on wheels. All points and no curves.

I must add, that at the record attempt with the Colani-Egli-Kawasaki, due to sidewinds at the track, after a few terrifying runs, Fritz Egli decided that the motorcycle was unrideable at high speeds, and out of safety reasons, decided to ride the record speed with the original Egli Mrd1 turbo designed and built bodywork.

Yes, Colani was many things, but not an aerodynamics engineer! His seat-of-the-pants ergonomic design was groundbreaking, but real-world performance is another matter, and when a rider’s safety is on the line, choose caution over creation…