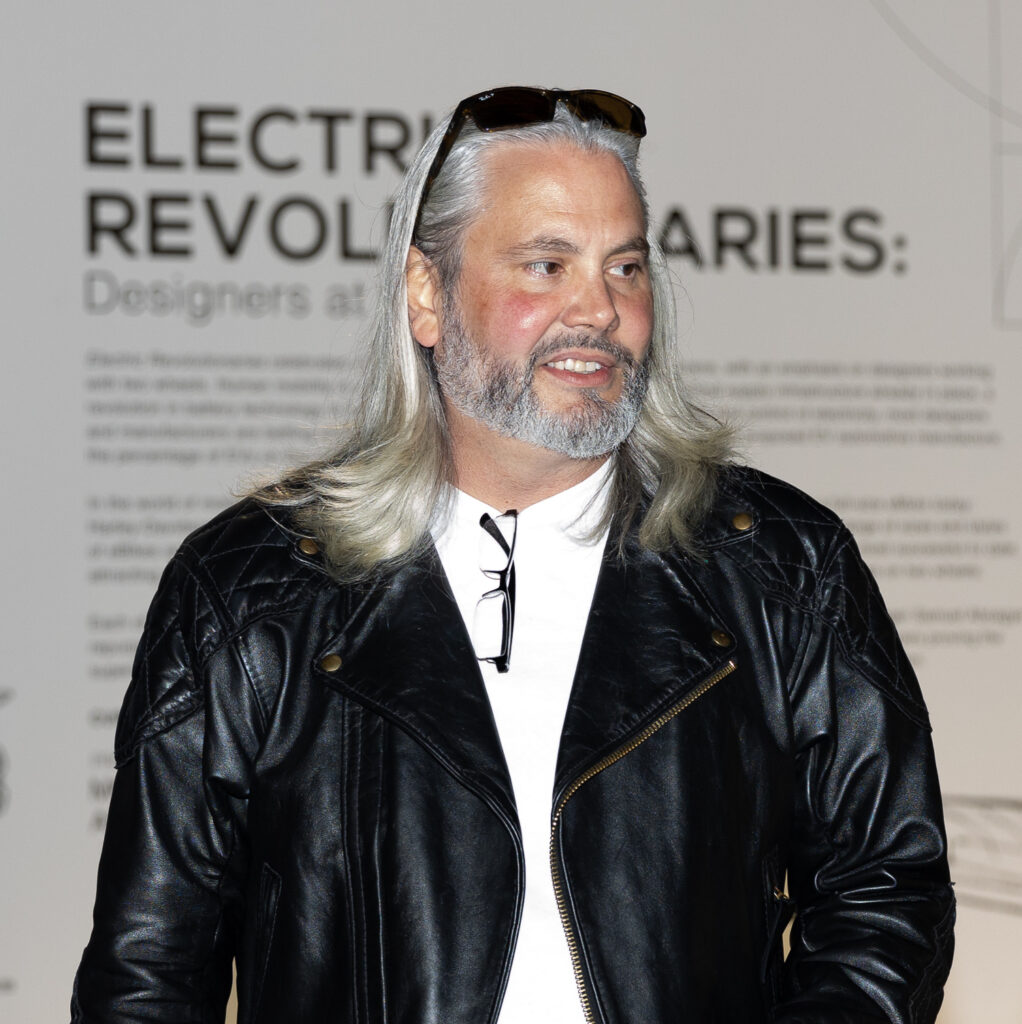

JT Nesbitt is a legend for his fiercely independent status in the motorcycle world, and two of his designs – the Confederate Wraith and G2 Hellcat – are among the most distinctive designs of the 20th Century. A New Orleans native, JT received his Master of Fine Arts from Louisiana Tech University’s School of Design. A stint writing for Iron Horse magazine led to a job with Matt Chambers of Confederate Motorcycles, and after Confederate left New Orleans after hurricane Katrina, he founded Bienville Studios, and drove his Magnolia Special CNG car across the USA, setting a record for an alternative fuel vehicle. When Matt Chambers changed course on his bespoke motorcycle business to focus on electric vehicles as the Curtiss Motorcycle Co., JT Nesbitt joined him once again to design The Curtiss One. While JT’s earlier designs flexed with aggressive, exposed structures, the One is an entirely different animal: elegant in an old-world way, with Art Nouveau lines and a joie de vivre surely reflecting his New Orleans roots.

Paul d’Orléans (PDO): Are you in New Orleans?

T Nesbitt (JT): Yeah, I’m joining you all from the what is now our [Curtiss Motorcycles] manufacturing facility. I’m in the electrical subassembly area of my shop, and this is where I do all the tuning; it’s all done via computer, the same computer that I’m talking to you with right now. We’re going to be lifting torque values, raising the torque limits.

PDO: Whose software are you using?

JT: We’ve engaged with the company called New Eagle, and they do a lot of EV integration This is a whole new world for me. I mean, I’ve built a fuel injected wiring harness before, but I’ve never done anything like all this high voltage stuff, I mean it’s dangerous. I’ve learned more in the past two years than I learned in the past 10.

You know, New Orleans actually has a pretty vibrant history of motorcycle manufacturing. Here’s one for for Paul, I bet you maybe you know this; in 1952 when Indian went out of business, the second largest producer of motorcycles in the United States was Simplex.

The Simplex motorcycle from New Orleans was once the second largest motorcycle manufacturer in the USA. [Mecum]

JT: No, it’s not that poetic. The old Simplex factory is now a Home Depot on Carrollton Ave. The funny thing is, it’s a history that that people here in New Orleans don’t celebrate because it’s so crazy that it could actually happen here. But it’s legit; the next motorcycle factory in New Orleans was Confederate. I’m going to call the Legacy Project, because it was serious production. So Curtiss is actually the 3rd bite of the apple.

PDO: Let’s just dig right into this: how long you been working on the Curtiss project?

JT: To be a motorcycle designer. I think you have to know a lot about motorcycles. You and I are kind of birds of a feather, we really embrace that history.

PDO: Right, nerds!

JT: Moto nerds. I’m a blood and guts kind of guy, and other designers are more conceptual. Well, it brings it brings up the whole question about contemporary motorcycle design.

PDO: And why is it so ******* awful? I wrote when the new Indian FT series came out, ‘this looks like a remarkable motorcycle. But why did they make the engine so ugly?’ Do people think it doesn’t matter anymore?

JT: Well, you know what I think man. I think it’s about who your heroes are. In all the time that I’ve been interviewing interviewing motorcycle design guys, the first question you should ask them is ‘who are your heroes?’ And in the EV world, it seems like their hero is Elon Musk. Not known for his exceptional taste. Elon Musk is not a motorcycle designer. He not even an automotive designer; he’s a visionary, which is a different matter. Therefore, he is not my hero. Steve Jobs is not my hero.

PDO: So who are your heroes then?

JT: well, let me let me show you something – I want to ask your opinion. What’s the most valuable motorcycle in the world?

PDO: The most valuable? Well…

PDO: That’s one of them.

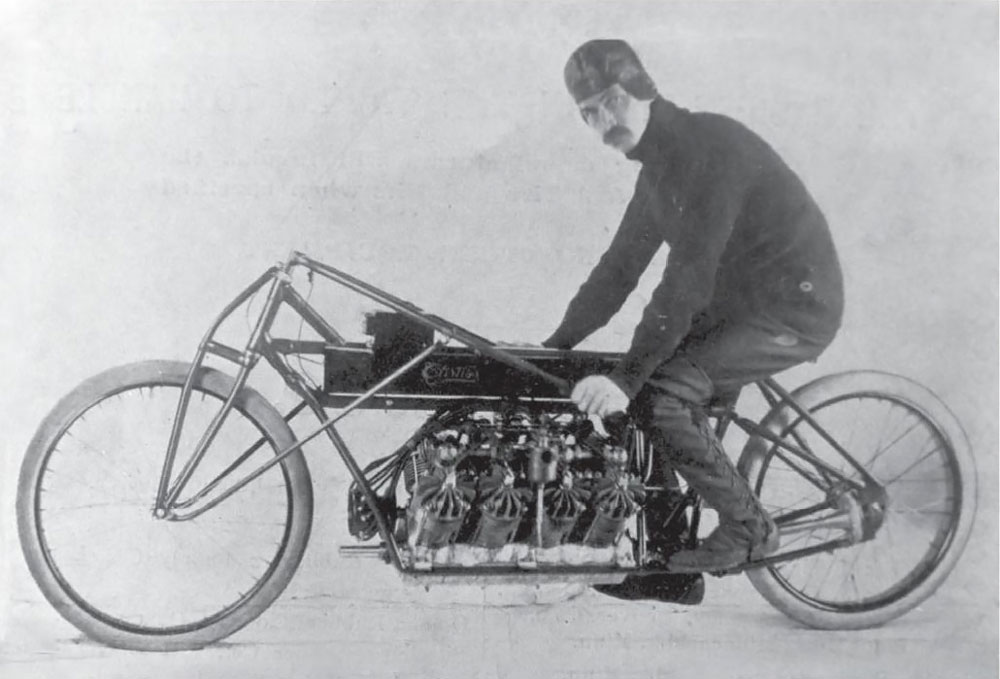

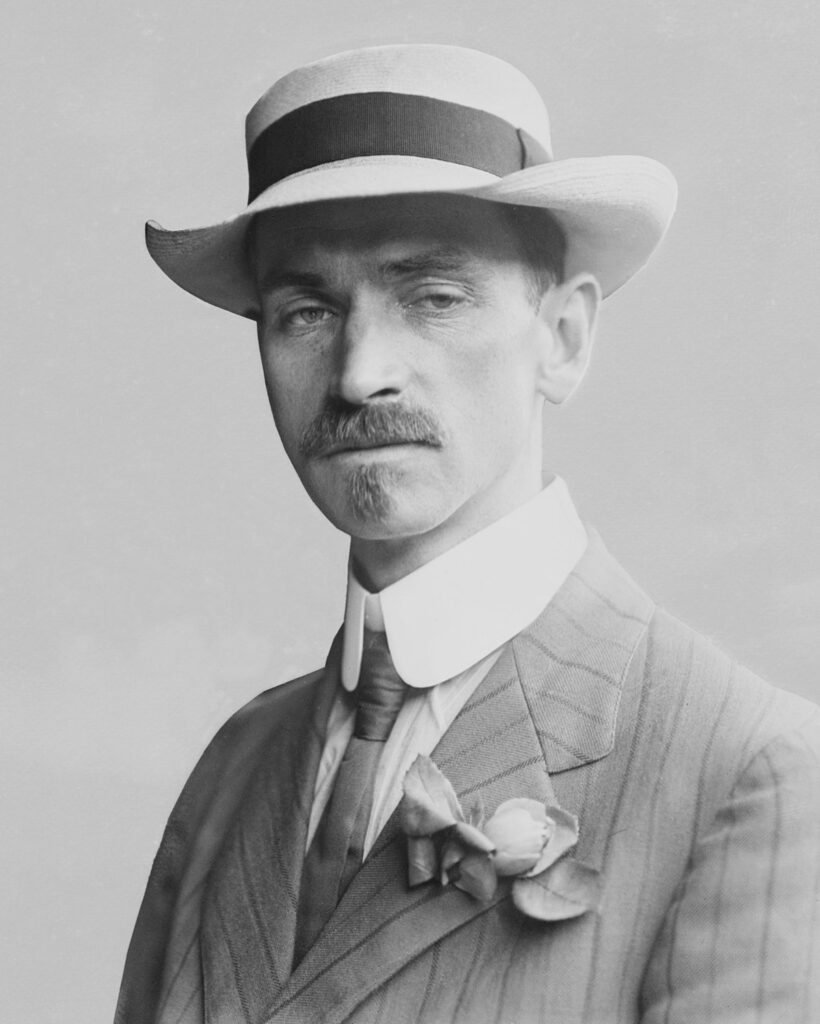

JT: So, the Vincent [that currently holds the record for most expensive vehicle at auction] is a very cool motorcycle, right? But this is a national treasure. This lives in the Smithsonian. It’s not in private hands. It could never be in private hands. So who are my heroes? Well, Glenn Curtis, who went 136 miles an hour in 1907. Yeah, I’ll take that guy.

PDO: On a machine of his own construction.

JT: That’s right: design, manufacture, construction and riding. Amazing what a what a person.

PDO: And he never crashed an airplane that he designed.

PDO: Pretty much so, I think: his was the first to take off under its own power, and return to its start location.

JT: The Wright brothers had a kite with a little lawn mower engine in it.

PDO: You don’t have to tell me: I’m firmly in the Curtis camp on this one. The Wright brothers needed a slingshot to launch their kite with a little putt putt on the back, and Curtiss made an airplane that you could actually maneuver.

JT: Yeah, take off: the Wright brothers hated him. It’s about ailerons – Curtiss invented the aileron instead of the wing-warp thing the Wrights used. That’s a good place to start, don’t you think?

PDO: Yeah, for sure Glenn Curtis’s probably the original. I mean, it’s just a shame that he basically gave up motorcycle manufacturing in 1912. I mean he licensed his name after that, but only briefly, to carry on motorcycle manufacturing. But then he just became involved in airplanes.

JT: So you know, people who are real motorcycle geeks know the Glenn Curtis story. But sadly, very few people know the history of the things they love.

PDO: Well, that’s why I’m so excited to be talking to you.

JT: Because your audience gets it.

JT: Because that whole world is dead. I mean it, it’s just gone, there’s no way to fix it, not not in our lifetime and moving forward. Then all these cars are going to be self-driving at some point, and I think in the fairly near future everybody’s going to have transportation pods…except for motorcyclists, because there’s almost no way to make a computer understand how to self-drive a thing that requires countersteer. So the only freedom the only freedom in 50-60 years is going to be on two wheels, right?

PDO: I agree, and it’ll be safe because all the cars will be programmed to avoid them. It’ll be the greatest time to ride motorcycles since 1912.

JT: Here’s the question for you. What are the electric motorcycles that are being made now? How are they going to be viewed in 50, 60, 70 years?

PDO: They’ll be the awkward Pioneers.

JT: No, they’re all going to be on the trash pile. They’re going to be in a landfill. Except for the Curtiss One. Because this one is designed to last forever.

PDO: In what ways – talk to us about that?

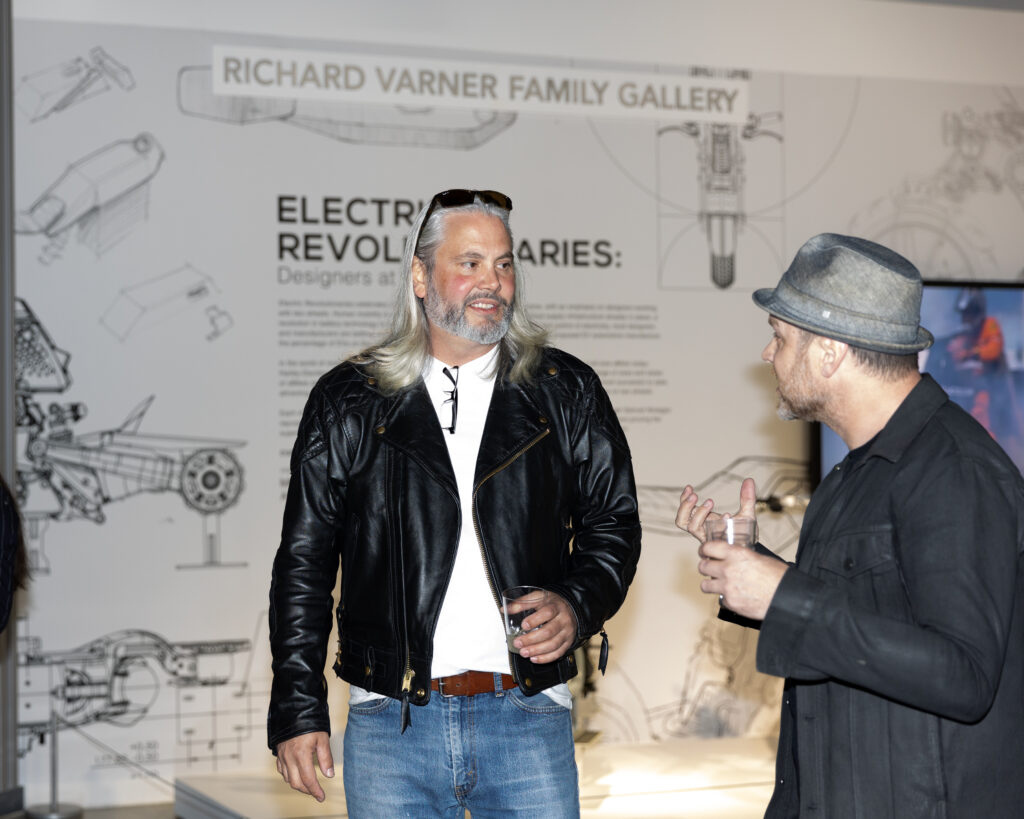

PDO: When I curated our Electric Revolution exhibit at the Petersen Museum, we featured the Mission One, built way back in 2009. A dear friend of mine, Mitch Pergola, who actually used to work for me, was President of a design firm called fuseproject, belonging to Yves Béhar. He’s an internationally famous product designer, who teamed up with a bunch of ex-Tesla employees who called themselves Hum Cycles, which became Mission Motors. They built the first electric sportbike – the Mission One – and it debuted in January of 2009, and Mitch did me the favor of letting me break the story: I wrote about it for The Vintagent. When I curated Custom Revolution, I reached out to my Mitch and we eventually tracked down the Mission One. Mission Motors only built two motorcycles.

JT: And then they got hired by Harley, the Mission Motors design became the basis of the LiveWire.

PDO: Seth LaForge eventually found the Mission One and the Mission R racer. The Mission One went to the Isle of Man, and was featured in the Neiman-Marcus Christmas catalog in 2009! Definitely the first eBike there. Anyway, I asked Seth, who owns both bikes, ‘can we can we ride this around?’ He said, ‘no man if you try to charge this thing up, it’ll probably burst into flame because of the old batteries; we would have to remanufacture batteries because they’re obsolete now.’ And we’re talking like 9 years later, and it’s an important piece of history. It was the first electric sportbike. It’s a beautiful machine, and it was the first time a famous designer had put put their hands on an electric motorcycle; it’s super important to history but can’t be ridden. It was an interesting lesson. I’m so used to dealing with old motorcycles, you know; it doesn’t matter how old it is…1904? Sure, man, it’s just basic principles. You get the clearances right, you sort the parts, it’ll run.

PDO: What a great quote!

PDO: And so is bad design.

JT: Right?

PDO: I’m so with you. And you know the truth of the matter is, it’s just my personal editorial policy, we just don’t cover something if we don’t like it, you know, it’s like, I don’t need to tell the world that this thing is ******* ugly. You know whatever it is, the world will decide this. I’m often shocked at how little taste people can have, but in general, people vote with their feet, they’ll let you know in the comments section how freaking ugly they think something is.

JT: Well, everybody thinks the Curtiss One is ugly.

JT: I think it’s because we’re getting lumped in with the other EVs. And not getting putting the bike in in context. All right, let’s pull up the image of that Moto Guzzi. I’m a huge fan of William Henderson, but my heroes are Glenn Curtis and Carlo Guzzi. There’s something about the radially finned cylinder [of a Moto Guzzi Falcone], man, I don’t know why I’m so crazy about that. I’ve never been able to give that radially-finned round object out of my head. It’s just lovely, isn’t it? It’s the best part of the motorcycle.

JT: And it’s funny that the Guzzi singles are not better known. I mean, Carlo Guzzi was amazing, and what a life.

PDO: Yeah, Moto Guzzi probably, of any motorcycle manufacturer ever, had the greatest range of engine designs they explored: single cylinder, V twin, V 8, inline triple, inline4 four It’s like incredible what they built.

JT: You can’t go to the Moto Guzzi Museum and not be overwhelmed with the amount of sheer joy that man lived his life with. That’s my hero as far as how do you live? What’s a life well lived ? And Carlo Guzzi nailed that.

PDO: Absolutely.

PDO: I see your motorcycle – it’s almost the same silhouette, that’s amazing.

PDO: It’s partly because NSU got sold to Volkswagen in 1969, and the problem with so many of these companies, it wasn’t convenient for car manufacturers to celebrate motorcycle DNA. So they become these lost characters.

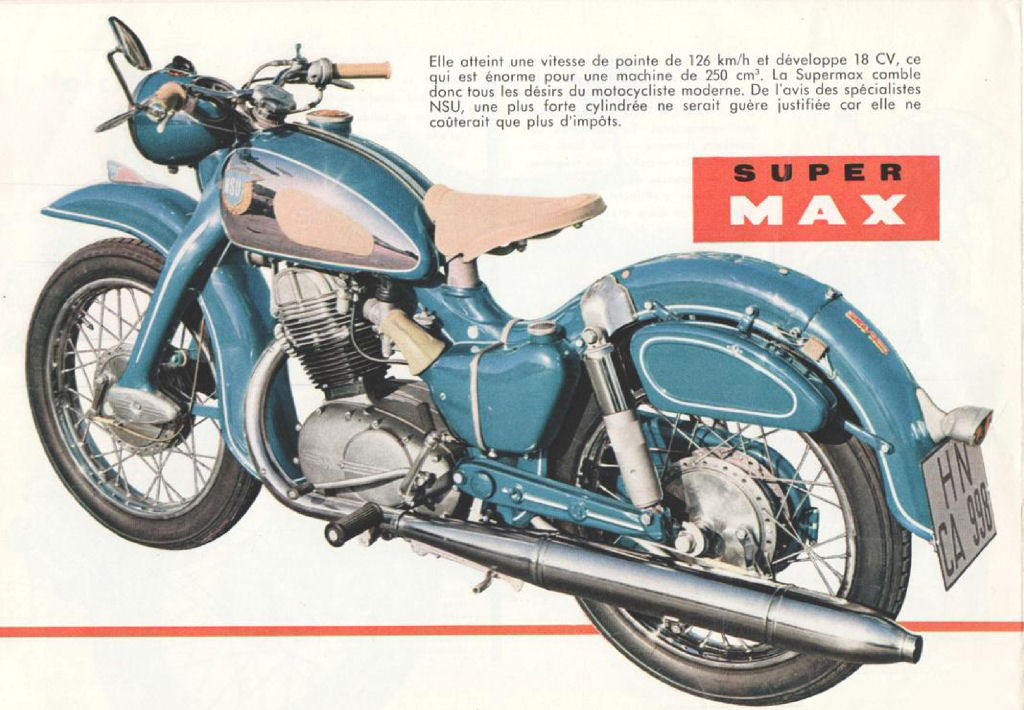

JT: Here’s something you may or may not know. In 1953, I believe it was when the NSU Max debuted, Soichiro Honda bought one.

PDO: Of course he did.

JT: And they reverse-engineered it and that’s what became the Honda Dream. He took this beautiful shape that we’re looking at, with all these sensuous curves, which I have absolutely used on my bike. All these beautiful curves. Soichiro Honda took this and he squared it all off. Like everything. The headlights square and the shocks are square. He took the most beautiful little motorcycle ever and ruined it. But, one of the things that he did is copy the shift pattern. NSU was strange for a European motorcycle because it shifted on the left. The reason why all motorcycles now shift on the left? It’s because of what we’re looking at right now.

PDO: I think the Japanese had a different agenda around design. I’ve thought a lot about Japanese science fiction and their motorcycle designs after the War. It’s just fascinating, but anyway, that’s a little too esoteric for this discussion. But yeah, as far as I know through my research, Soichiro Honda visited the NSU factory in 1955, when they were at the top of their game winning every Grand Prix race they entered.

And they shared everything with him, and he may have even – I’ve never been able to confirm this – they may have sold him an obsolete racing engine. And that was the true basis of the twin-cylinder overhead camshaft Honda design.

JT: Let’s look at that image of the NSU one more time. One of the things I want you to notice about this, Paul is the distance between the exhaust pipe and the front fender. It’s so tight. And if you look at the Curtis One in the sport position with the 27 degree rake, you’ll see this super tight clearance between the front fender and the battery zone. Something you could never achieve with a telescopic front end, right? Can we look at the Imme You know that bike?

JT: Tell me why?

PDO: Because they use a single-diameter of tubing in the whole chassis, and duplicate functions; the swing arm is the exhaust pipe, it’s crazy. He he took it a little bit too far, though, because he was into this whole one-sided thing and used a an overhung single-sided crankshaft which was the weak point, and bankrupted the company because it failed early and they had warranty claims. But what an incredible design.

JT: You know he drank a little of his too much of his own Kool-aid, but the chassis worked. What this motorcycle represents is true minimalism. That doesn’t mean minimalism as a styling key. Because its styling is not minimalist, right? It has no flat surfaces. This isn’t a minimalist styling exercise. It’s actual minimalism. Minimalism is about the bill of materials and parts reuse. What I’m drawing from Norbert Reidel, from his most excellent project, is the ability to reuse parts in very creative ways. I don’t know if you’ve noticed on our bike, but the suspension members are all the same. Have you noticed that?

JT: So our girder our girder blades: part #1, quantity 4. There’s no fore and aft, and there’s no port and starboard. It’s the same part that does all of the suspension work on the motorcycle. Which is way more difficult to design, because if you make a change on the front right, it changes the front left and the rear right and the rear left. It changes it in three other places. So it’s a lot more work, but at the end of the day, you get this melody. The Imme has it has a melody to it, because of its minimalism.

PDO: That makes sense. It’s like a Steve Reich composition, if you repeat things and then have a variation on a theme, you create a new kind of music.

PDO: So was I.

JT: There you go. Who’d you follow?

PDO: I was a huge fan of Max Beckmann and the Expressionist and the Blue Rider group in Germany and people like that. This was the early 1980s, I was into punk, and for me it was about expression. But I certainly learned my art history up and down.

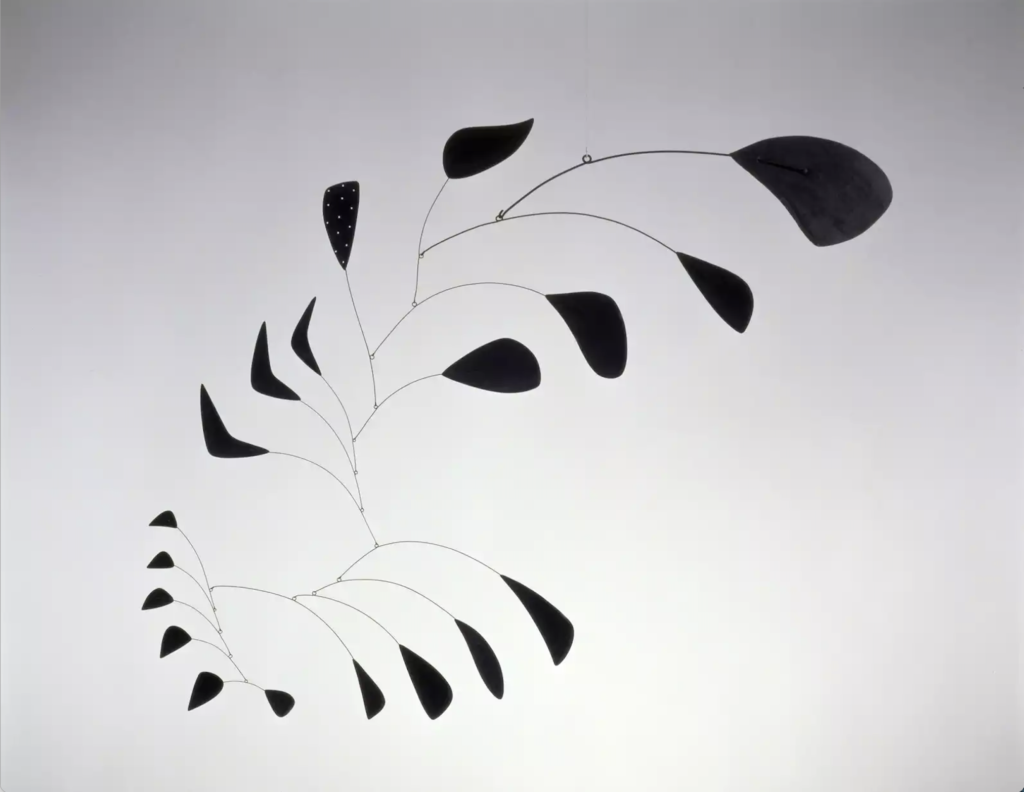

JT: OK, I love Calder, Calder invented kinetic sculpture. And kinetic sculpture actually translates quite well into our chosen passion. Sculpture that moves, and what we love are sculptural things that move.

PDO: Would that more designers adhered to such a philosophy, or acknowledged it, or even looked at art. God knows what they’re looking at these days.

JT: Or had any philosophy?

PDO: Can we kind of explore the importance of beauty to you? You know, a form over function almost. Can you talk about that?

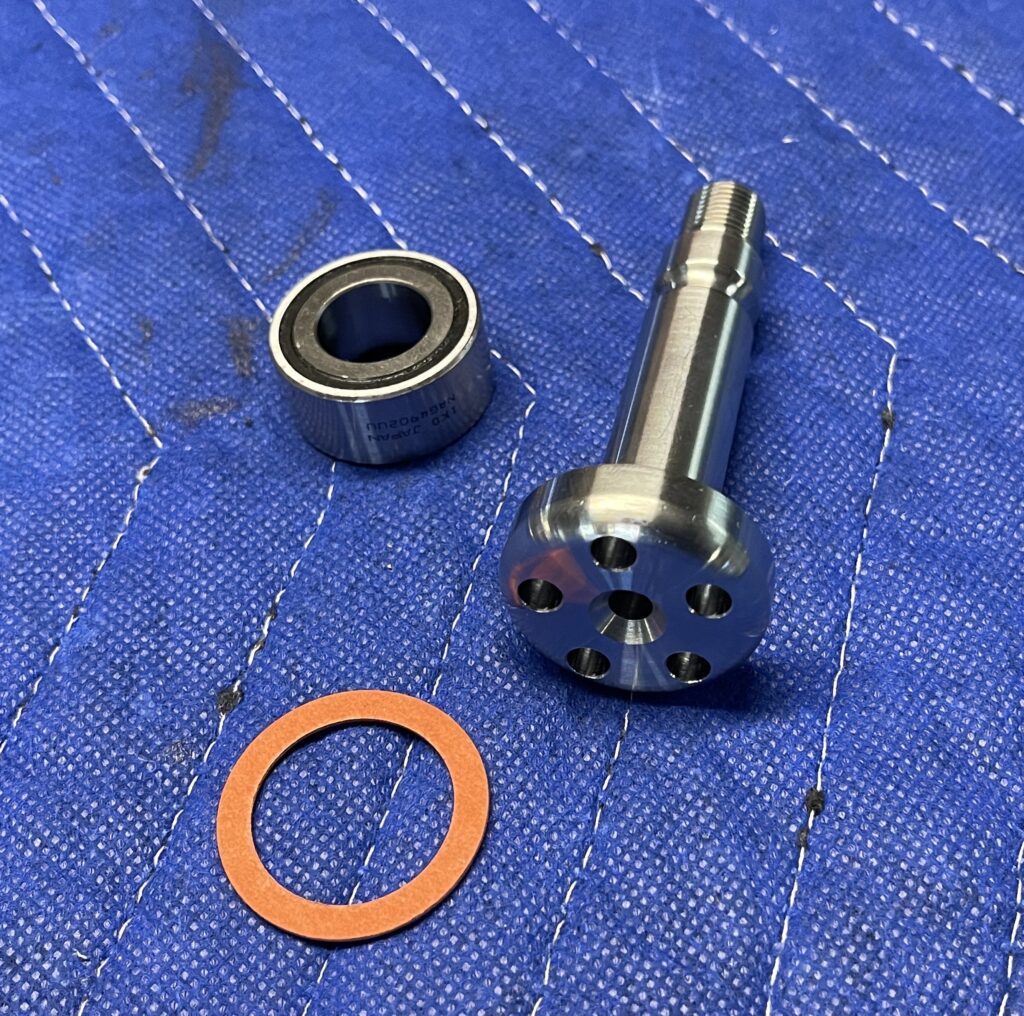

JT: OK, let’s have a look at this. So I think this is one of the most beautiful parts on the motorcycle. This is our hardware; I designed all of our own hardware. And I designed it because of this bearing. So this is a very rare bearing; a double-row sealed needle bearing with a 15 millimeter shaft. There are no shoulder bolts for 15 millimeter shafts. Therefore you have to make one. So if you look at our bolt, you see a little lip on the inside of it. That fits a fiber washer that serves as a guard for a 15 millimeter double sealed needle bearing. There’s a chamfer on the center; that’s so that our tool is self centered. The little divot is for a set screw that actually locks the bolt in place. This system is used everywhere on the motorcycle where there’s reciprocating motion. We don’t have a single bushing on this motorcycle. There is no stiction anywhere. As you well know, with hydraulic fork tubes, one of their main issues is stiction. This eliminates all the stiction. And this bearing retails for $75. When people ask me ‘why is this motorcycle so expensive?’ It’s because this bearing is 75 bucks. Just this. So when it comes to beauty, there’s a great quote by Ettore Bugatti: “There is nothing that is too beautiful or too expensive.”

PDO: I love that. Sounds like something Coco Chanel would say.

PDO: Of course they are!

PDO: Well, Bimota SB2 has an adjustable rake. We had one in our Petersen Museum exhibit, ‘Silver Shotgun’.

JT: It has adjustable offset; functionally the same, but we can have another conversation about that. But no, it’s not the same at all. Adjusting the offset is the angle of your fork, that is not your rake. Your rake is your steering head angle, and that’s fixed, right, so you can adjust the offset not the rake. This motorcycle has an adjustable steering head per se. I’m talking about an actual adjustable rake, right? Rake is dictated your steering axis, which is dictated by your chassis.

PDO: What’s your history with EVs?

PDO: And he had a grant of $400 million from the government to do that.

JT: I was just a guy in a car with a credit card. Leno did a did a spot on it for Jay Leno’s garage. When I got to LA, I reached out to Ian Barry. One of my fenders had a hairline crack in it, it used all aluminum fenders and I needed somebody with a welding machine to tack it up. He brought me into his shop and was real nice to me.

PDO: I’m just thinking that you two have a similar philosophy about design. When he’s building custom motorcycles, I’ve written about how he approached reassessing design decisions on existing motorcycles. It’s like, OK, let’s look at the shifter mechanism on this Triumph. That part was designed by someone within certain parameters. So how can we re-approach this design problem, and see if we can make something better, maybe improve it, maybe make it more beautiful, maybe make it lighter. I’ve talked to a lot of motorcycle designers. and not a lot of them think that way.

PDO: Yeah, that’s true. I’ve ridden those bikes. I mean, some of them hurt.

JT: Why go to the trouble of coming up with all those very crafty, clever solutions, yet produce something that doesn’t solve one of the most fundamental problems of motorcycles, and that’s ergonomics. Something that nobody’s talking about. Now, let me let me grab a part. [Picks up Curtiss One seat]

Stephanie Weaver: It looks like a horse riding saddle!

JT: Very perceptive – and an English saddle at that. The problem is that motorcycles ergonomics are all based on the early days of a mashup of a bicycle with a little motor clipped into it. When you’re pedaling a bicycle, you don’t use the seat. You’re standing on the pedals and and any friction that that you would encounter between your thighs and ass would slow you down. Using bicycle seats on motorcycles is like putting lawn chairs in sports cars. It’s crazy. Where should we be looking for inspiration? 2700 years of research and development. That’s the interface of man and animal. That’s where it all comes from. This is where you grip the motorcycle, and one thing that I’ve noticed is I can tell when I’m looking at a female riding a motorcycle. They ride differently than men: men do this manspreading thing. Women grab that motorcycle with their knees. Now, why in the hell do we have human beings grabbing a piece of painted steel with the most sensitive parts of your knee? That’s crazy. All of the surfaces of of interface between man or woman and machine need to be reconciled. We have to start over with this whole proposition. First principle, originalist thinking dictates that we rethink motorcycle ergonomics, and we make them gender neutral.

JT: Well, here’s the thing, Paul. You’ve never ridden a motorcycle where you could feel the chassis through your inner thigh, and the it’s sensitive part of your knee. No one has. It’s delightful because you can really understand what’s going on with the exchange of information from the chassis to your body. It gives you much more confidence, you can actually for the first time really feel what the chassis is doing. The thing is, when you eliminate, all of the vibration, all these little things that you don’t really notice on a bike that’s buzzing around underneath you start coming to the surface. Because your your mind is now free to think about those things.

PDO: User interface (UI) is a huge industry now. I actually have a niece who studied brain/computer interface as her postdoctoral research at MIT, and then she went to work for the train industry. Because we haven’t designed a new train in the United States since, what, the 1950s really, and you know and and the number one problem with train design is keeping the operators awake and interested. So you’ve got this huge investment that’s happening in user interface for very specific reasons. For all sorts of industries, but I don’t see a lot of UI research going into motorcycling.

JT: It’s because all people care about is the way a bike looks on the sides; that’s not how how motorcycles are actually seen in the wild. They’re all seen with a rider on board. So while this motorcycle [the Curtiss One] might look a little weird, once you snap the person into place, it completes the object. It’s incomplete without the rider attached to it.

JT: You know why people treasure this object? You know it’s about the experience. It’s completely unique. You know there’s nothing, nothing that comes close. But a Vincent, I’d much rather experience it on the side stand.

PDO: Is that right? Well, I love the experience of moving through space under under the power of my right hand, on the throttle or lever or whatever my vintage motorcycle is. And sometimes sometimes they’re uncomfortable. But it’s also sheer joy.

JT: I got to tell you man, my Norton Commando is now up for sale. Because I’ve seen a new way and man, this is just better.

PDO: You’ve been ruined!

JT: I have. It’s better because the feeling, the sensation is so much more connected. The stress level is like down because of all the things that we’ve done to elevate the riding experience, that analog riding experience. It’s just better in every way. I have no desire to ride my Commando. I’m a Vincent owner who’s getting rid of his Vincents.

PDO: How interesting. I can’t wait to ride your machine.

JT: I hope that you’ll agree with me.

PDO: Well, it’s a motorcycle and I love motorcycles. I already think it’s beautiful. I’m really curious to see how it feels to ride it.

Revolutionary ;

” A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term revolutionary can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor” ( WikiP)

Sorry folks … much as I may of appreciated some of JT’s previous ‘ creativity ‘ … Revolutionary is not a term I’d of ever applied to him or his ‘ work’ . Eclectic .. a bit iconoclastic … artistic even .. yes … revolutionary … not hardly .

In as far as this specific MMtB ( More Money than Brains ) M/C is concerned .. NIMBY ( not in my backyard ) sums it up quite nicely … e.g. … over priced never to be ridden jewelry … verging on wretched excess carbon footprint heavy* garbage

Seriously JT … drop the whole M/C thing .. do less damage .. and turn your talents to sculpture and art … cause the M/C thing aint been workin out fer ya so far .

Sigh … how the mighty are falling left and right as these futile desperate attempts at profit in this rapidly decaying age of Anarcho -Capitalism overwhelms common sense , engineering and intelligence . Karl Marx’s warning that capitalism will ultimately consume itself coming to mind

( full discloser … I do not adhere to communist ideology … of any kind … but when someone is right despite their agenda .. they’re right )

Hmmm … the difficulties of dealing with ” Cassandra Complex” sailing on this pathetic ” Ship of Fools ” of our own creation

—————————————

* Fact ; The manufacturing of an EV has a carbon footprint many times larger than that of any equivalent ICE . With an EV depending on brand , source of electricity etc taking 3-5 years ( or more ) to become equal to an ICE’s overall carbon footprint .

The greatest ironies ?

The majority of EV’s projected lifespan ( especially the battery ) is five years or less .

With the overwhelming majority of EV ownership being between 1 and 3 years .. meaning the majority of EV owners buy/lease a new EV every one to three years .

So do the math …. it aint pretty .. nor is anyone who participates in this NIMBY greenwashing ” Road to Perdition ”

( information from DW news … the German Transportation Admin . .. BMW / Toyota / M-B / Honda etc .. et al .. ad nauseam )

Woah! Trollin’ just 2 troll. A lot of talk with nothing to say. So disillusioned from reality. I bet you were team Amber Turd lol 😂

The bike is exquisite. The pictures don’t do it justice. I’ve had the pleasure of seeing this project go from charcoal and newsprint sketches to a motorcycle that is not only beautiful but also really fun to ride and approachable even for a novice like me. The ride is smooth and comfortable and the silence allows you to take it in your surroundings in a way you can’t on an internal combustion bike.

Slinger Wow are you out touch. This guy nailed it with his new Curtiss and had the balls to back it up with his philosophy. Who would dare to tell you to sell the Norton or Vincent, but give you a peek into his design inspiration. He told it like it is- to him. OH hell yes. You on the other hand reminded comments of a bumbling mumbling grand stander off his rocker with trolling shade. He would accept critique, but yours is just like the wind that was just passed. Go see the Doctor and have your Blisters removed from your mind, you just poked the Bear. GO home.

Well, here we go again.

This fucking Troll.

Hey “GuitarSlinger” – My name is JT Nesbitt. I don’t hide behind my keyboard. I have dedicated my life to the pursuit, and advancement of motorcycle design. If that means suffering the pitiful critique of chumps like you who have never actually built something new, it is a small price to pay.

While some of us are in a fight to save the Motorcycle from the downward spiraling trajectory that it is currently on, there you sit, at your keyboard, achieving nothing. — JT

“Guitar Slinger”, another tiresome bore hiding behind a self-aggrandising pseudonym.

Let’s deal with your mud-slinging point by point:

Your advice to JT:

There’s no call for taking personal pot-shots at someone because you don’t like their motorcycle. What have you designed and built?

“Over priced and never ridden”:

The bill of materials alone on the machine dictates the cost of the machine. Name one other production motorcycle that has carbon composite structural members? What other motorcycle has a fully machined chassis and a full immersion battery? This level of build quality costs money.

The motorcycle is built as a ‘forever ride’. it is designed to be ridden for many decades, it’s anti obsolescence. There are so few moving parts on the machine that it requires minimal maintenance and the quality of the parts are so high that deterioration will be negligible over several decades. It’s designed around the rider, allowing the rider an unprecedented range of adjustments – that can be achieved by the rider with just three simple supplied hand tools – to set the bike up for optimum comfort.

Revolutionary:

The Centred Power Axis. This is the first time this patented technology has ever been used on any motorcycle – ICE or electric. It reduces stress and wear considerably thus increasing lifespan of the motorcycle considerably. it centres the drive train in the motorcycle and allows the rider to be centred on the machine enhancing balance and stability.

Full immersion battery technology: This proprietary technology is the first time this technology has been used on an LEV. The immersion technology and design of the vessel allows the battery to operate at a touch over 30 degrees centigrade, much cooler than any other LEV and eliminates the danger of the batteries catching on fire.

By your lazy definition these two examples qualify as ‘revolutionary’.

Manufacturing:

The Curtiss 1 has only 175 different proprietary machined parts with 75% of all parts used in more than one place performing different functions. For example the output shaft is also the swingers arm pivot. These factors alone reduce the manufacturing footprint considerably.

The decaying age of Anarcho-Capitalism:

Not to school you, but the US is one of the most, if not the most centralised and heavily regulated capitalist economies in the world, so therefore is the opposite of the definition of Anarcho-Capitalism. Stop trying to sound clever by brandishing terms you don’t understand. Also, as a matter of interest, how many exemplary examples of two wheeled transport, or four, has been produced by Marxist economies?

To quote you: “The difficulties of dealing with ” Cassandra Complex” sailing on this pathetic ” Ship of Fools ” of our own creation” – now you really are mixing the metaphors in your sub-par high-school thesis.

EV projected lifespan:

The Curtiss 1 has built in anti-obsolescence as explained above. Furthermore, the batteries are entirely modular. Worn/outdated cells can simply be removed from the vessel and updated with contemporary technology. This is a service offered by Curtiss. Therefore the lifespan for The Curtiss is for as long as you wish to maintain the bearings, replace the worn tyres and upgrade the battery cells. It’s capable of having a generational lifespan.

I could go on and on, but ultimately your commentary really is a thinly veiled deluge of insults aimed at a man who had the courage to innovate, invent and reimagine what designing and manufacturing a motorcycle can be. All whilst you don’t even have the courage to publish your name and stand by your statements.

“Guitar Slinger” I’ll start by saying of all the people I’ve met in my life and specifically the motorcycle community and it’s a lot, JT is one guy that certainly doesn’t need anyone to stand up and defend him. I’ve spent the last 2 years riding around the US, Canada, and parts of India photographing some of the most incredible people in the motorcycle community. Builders, racers, collectors, and world travelers. Last summer JT was kind enough to allow me to spend some time with him in New Orleans and show me around his shop while finishing up The Curtiss One. I have never seen such incredible attention to detail in anything in my life. JT’s commitment to getting it right and making it beautiful at the same time is next level. You may not be the type of person to buy a bike like this or to embrace new ways of thinking but to essentially shit on someone that takes his skill, passion, and creative vision and brings it to life is a sad commentary. But there will always be people like you. Sitting in your armchair or standing on your soapbox. Perhaps the only reason for someone like you is to spur on people like JT. I’d love to see your letters to Steve Jobs and Horatio Pagani. I should also add that JT is an incredibly kind and generous person. He took me in sight unseen and put me up, shared his home, and “broke bread” That’s a testament to his character, your letter is one to yours.

Great interview, Paul!

When I began working with Matt in 2015, he asked me the “heroes” question. I answered “JT Nesbitt of course; he’s why I’m here”. A few years later JT joined us at Curtiss and I’ve had the privilege to work (and learn) alongside one of my personal design heroes for the past four years. Inspirational to say the least, and a ‘revolutionary’ if there ever was one.

The 1 is so thoroughly considered from front to back and it is an absolute joy to ride. You’re going to love it, Paul.

Fascinating approach to design. Imagine a world where everything was so considered! Can you design us all an electric car JT!? The only point I don’t buy is the “styling” bit. Styling was OF COURSE considered, whether you want to admit it or not. The interesting pinstripe inlays and the contrast stitching on the seat among other things were of course aesthetically considered. It is all very well managed in my opinion too. Great work — just don’t disregard the IMPORTANCE of good styling and taste. In the end, it is what gets someone to take the bait. Good engineering is important (of course) and necessary for the level of sustainability Curtiss is attempting to achieve, but style and taste are just as important if not more! It’s okay to admit that styling was considered… it’s okay to admit that it matters, because it does (and you’re great at it)!!! Love the bike and your new website is killer. Some great additional photos on there, folks. When will we get some more riding focused videos??

JT created the perfect motorcycle to launch our restoration of the all American Curtiss legacy marquee.

It has great style and great design roots, but the battery change needs to be quicker. ie 5 minutes from a cross-continent chain of service stations stocking fully charged drop in batteries. It will only take a billion dollars. Without range and support, the future “freedom of the road” will be the domain of the metro distinguished ‘gentleman’ only.

Battery needs to be 5 times larger.

For a while after I bought my Black Shadow I would find myself, with the bike up on the lift, just standing there appreciating some small detail. Time would stop and I’d come back to reality a half hour later having noticed a half-dozen other beautifully crafted, eye pleasing small details. I’ve seen the Curtiss One, and it has that same effect. The whole is visually arresting, and greater than the sum of its thoughtfully executed parts… it is in fact rolling art. Every time I look at one of these I see something more.

Unlike Mr. Nesbitt, I’m not ready to part with my Vincents or my Nortons, but I’m certainly ready to make room next to them for a true modern classic.

Nice interview, JT and Paul, very informative and interesting, and inspiring. Time will validate the significance and genius of the Curtiss One, just as already proven of the G2 Hellcat and Wraith before it. From those of us who motorcycle, or at least from me personally, a sincere and heartfelt thank you, as your bikes are truly life changing and enhancing. Understatement. Congratulations to you, JT and to the entire Curtiss Team, you make life better. Well done, keep doing great things.

Wonderful article on design from the designer, and design’s ultimate purpose.

Looking forward (In more ways than one) to see what JT creates next.

Oh yes – even the tool set is captivating….

PS: Meeting JT at the 2019 Quail was a real kick!

The Mission R is back out there? Excellent! A lot of talent went into that machine.

RIP, Sandy Kosman,

Can’t wait for the ride report Paul.