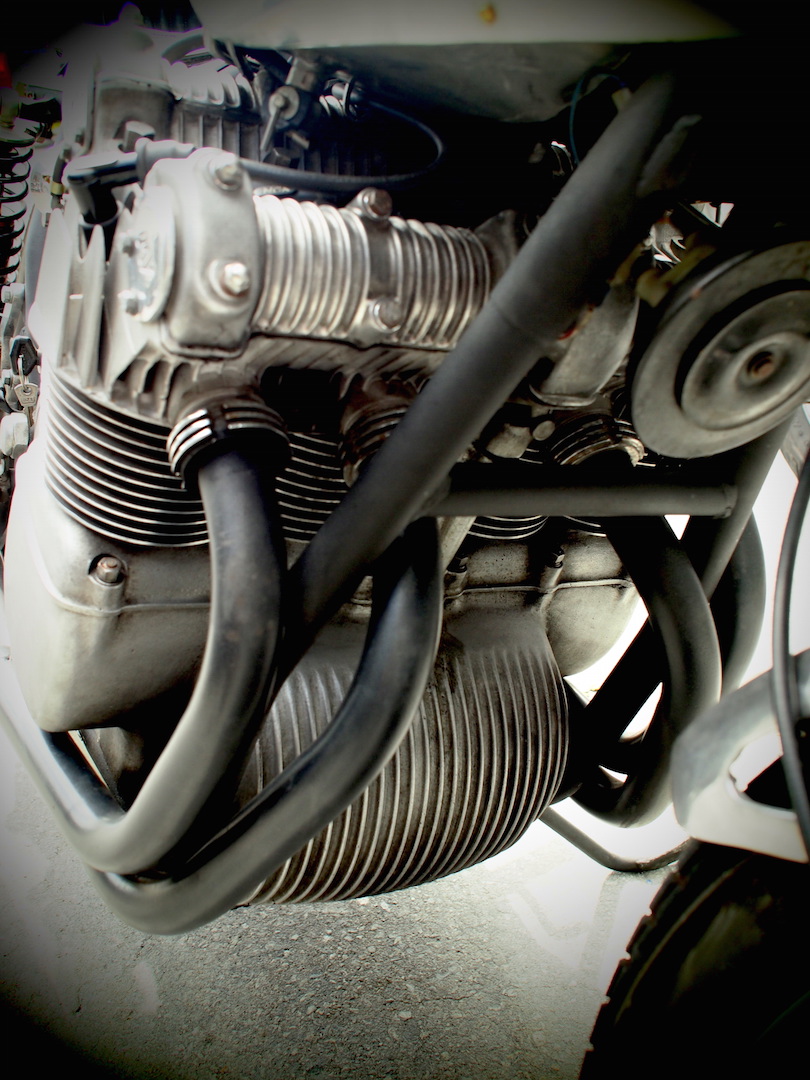

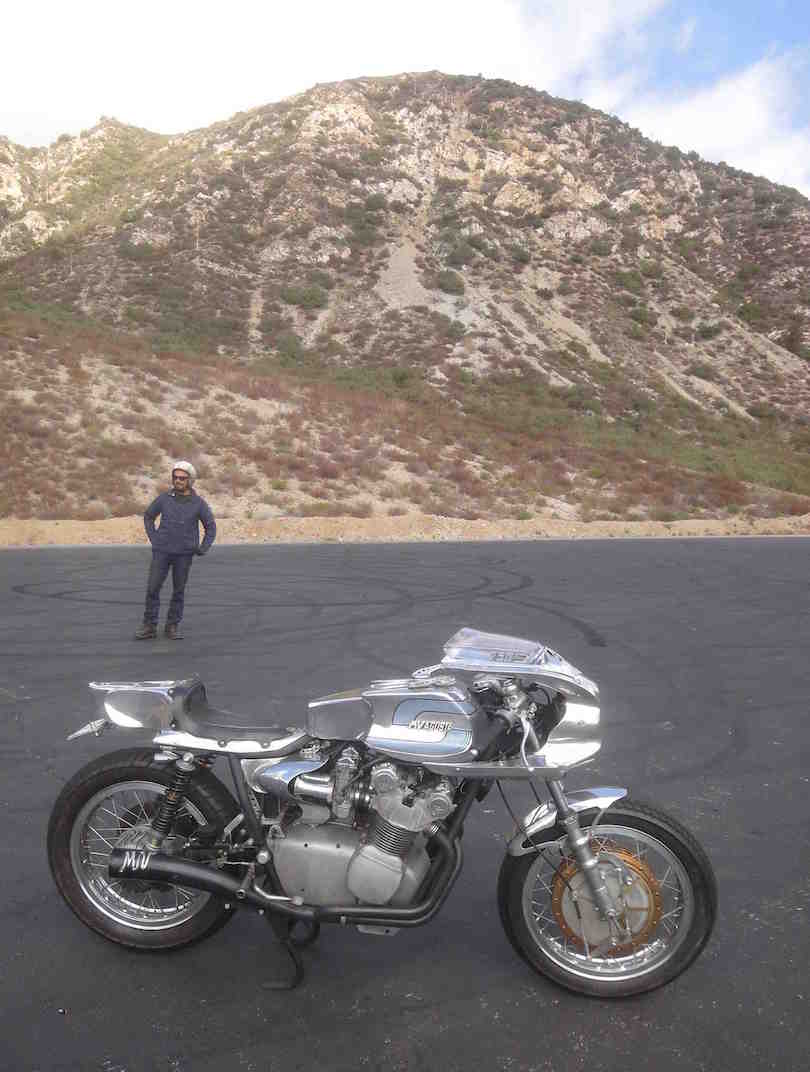

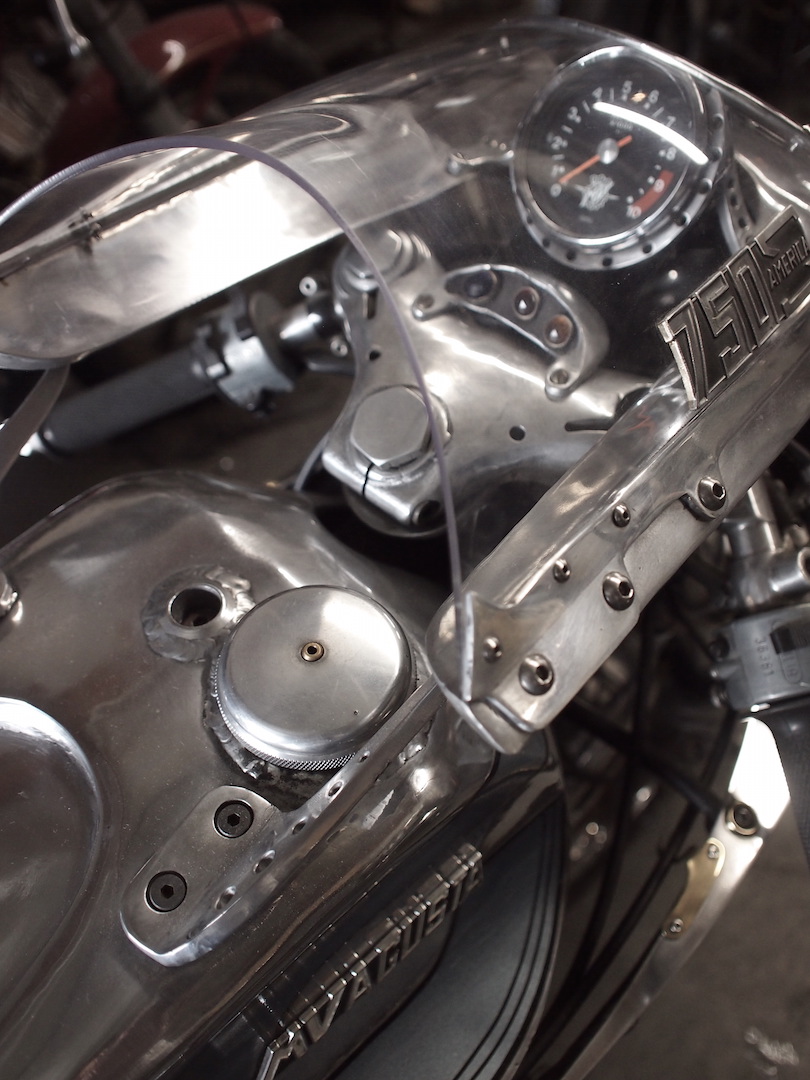

The original 1970s MV Agusta ‘4’ is legendary for its beautiful lines, and collectors scrabble when they come up for sale. To dare approach Count Domenica Agusta’s glamourous baby, intent on customization, is almost unheard of. In modifying a ca.1974 MV Agusta 750S, Shinya Kimura has kept the chassis intact, to the point of retaining the Count’s ‘you’ll never race this’ shaft drive, the first item every MV hotrodder in history has ditched. Why? ‘I really like the radial fins on the final drive, it’s very pretty’. His attitude fits his self-described role as a coachbuilder; respect your chosen chassis, but clothe it in a bespoke suit. MV fours, though expensive and coveted, are hardly rare, and plenty have been racerized by the likes of Arturo Magni and Albert Bold. None look like the naked aluminum creature in these photos.

With stock power output about 66hp at a modest (today) 8000rpm, that kind of weight won’t be setting quarter-mile records. If the MV is to be ridden quickly, you need to employ the old single-cylinder racing trick of ‘maintaining momentum’, ie, fast into corners, hard over, don’t brake unless you’ve seriously underestimated the turn…or overestimated your gumption. Easy on a 350lb hotrod Velocette Thruxton, not so natural on a quarter-ton Latin legend with masterpiece bodywork.

I really don’t “get” this custom. Do most find it more pleasing than what the master turned out, so many decades ago?

yes considering “the master” purposely dumbed down his road bikes in favor of his own factory works racing team, and then and now, every one knows it, and then and now thats why people choose to pay far less for a suzuki lol. track bike from MV? shit yes. road bike? nah ill buy a norton, suzuki, triumph, yamaha, etc from the period way quicker.

A lil Big Sid ( Biberman ) wisdom fer y’all ;

” Stock is a can of soup on a shelf ”

e.g. … if there’s plenty to go around … why not hot rod a few here and there … I mean seriously … does ya really think the profit driven – designed by consensus – corporately homogenized bike is the pinnacle of what it can be ?

Don”t get me wrong … MV’s are mighty fine … but why not individualize a few .. not to mention potentially make em better ?

Sheesh …

The longer you do it, Shinya, the better you get at it…haha.

Gratulation, it turned out EXCELLENT.

Lawrence, if it has to be explained then you wouldn’t understand.

Missed out on this one for what ever reason .Great to see a Shinya bike road tested ….. though … errr … a video would of been awfully damn nice !

( yeah yeah … the Grump strikes again …. but hell … it just means i likes y’al )

😎