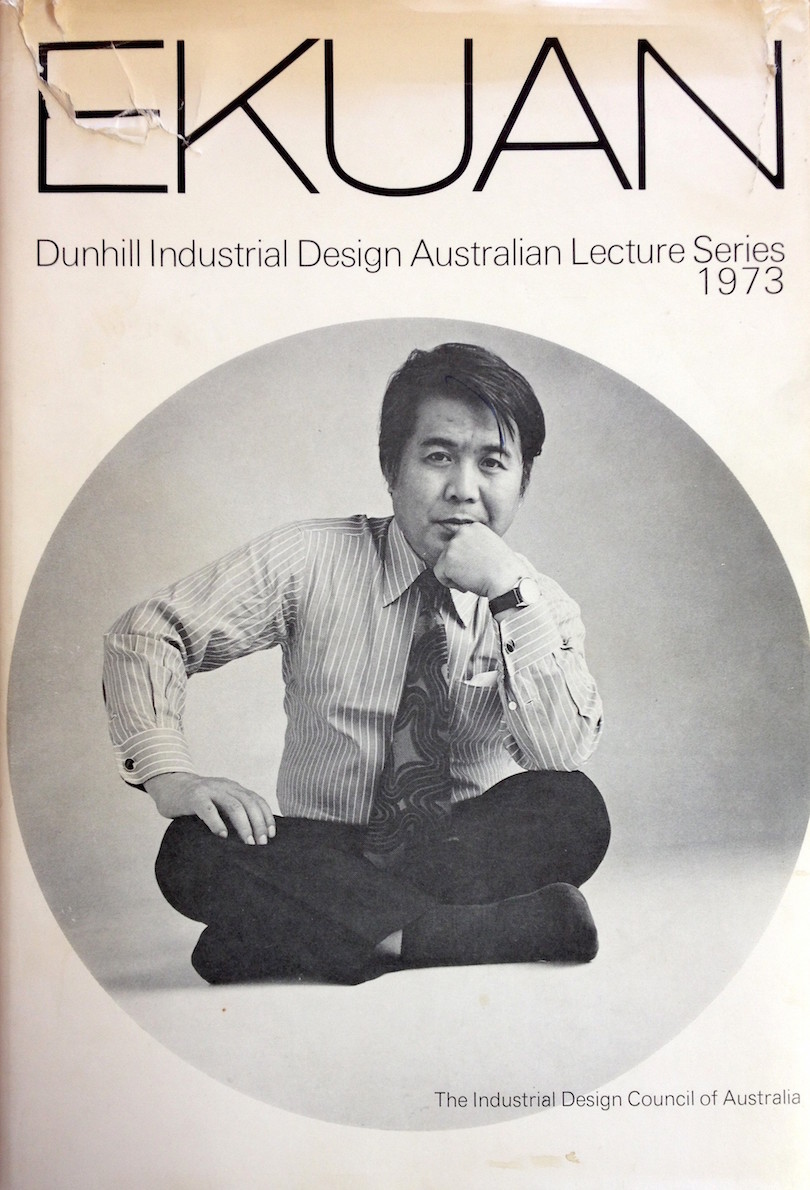

Kenji Ekuan

As a child, he wandered the streets of his native Hiroshima just after the nuclear devastation, and spoke of hearing the voices of 'mangled streetcars, bicycles and other objects', lamenting they could no longer be used. After his father died from radiation poisoning, Kenji Ekuan became a monk, but changed course to become the most celebrated industrial designer in Japan. He graduated from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in 1955, and set up his own design business in 1957. Regarding 'futuristic' design, Ekuan stated, "When we think of the future of design, we might imagine a world where robots are everywhere, but that's not it. The ultimate design is little different from the natural world."

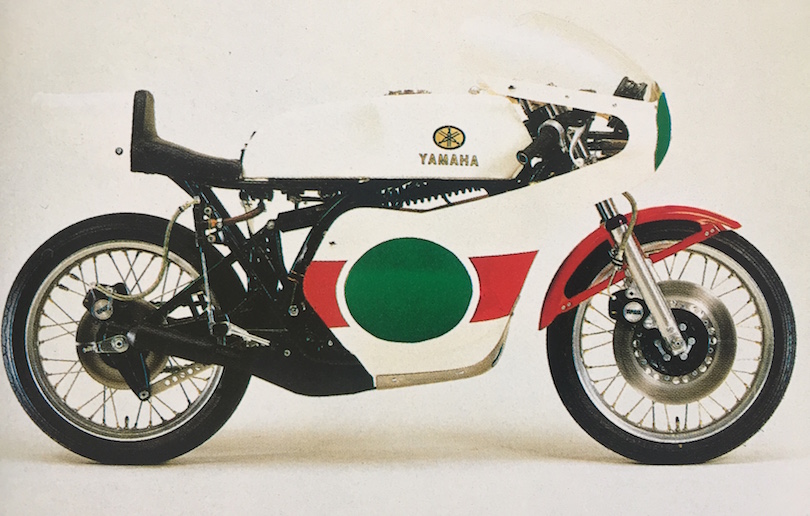

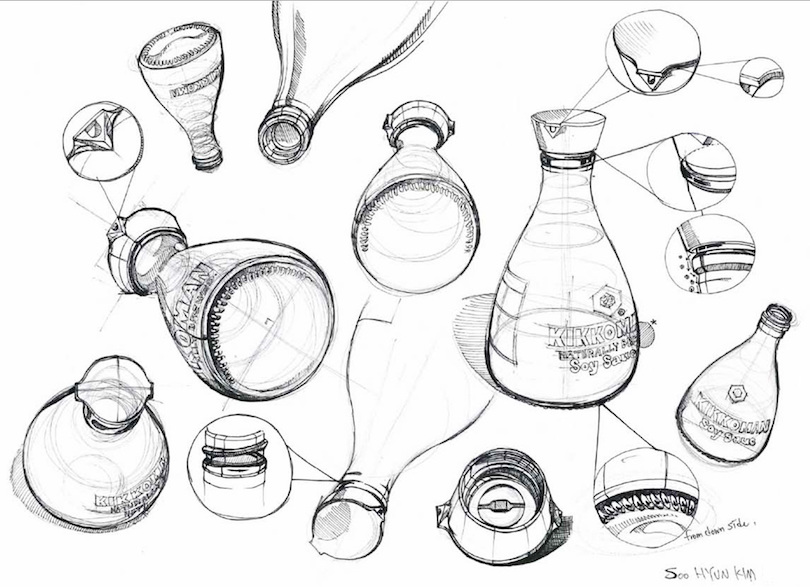

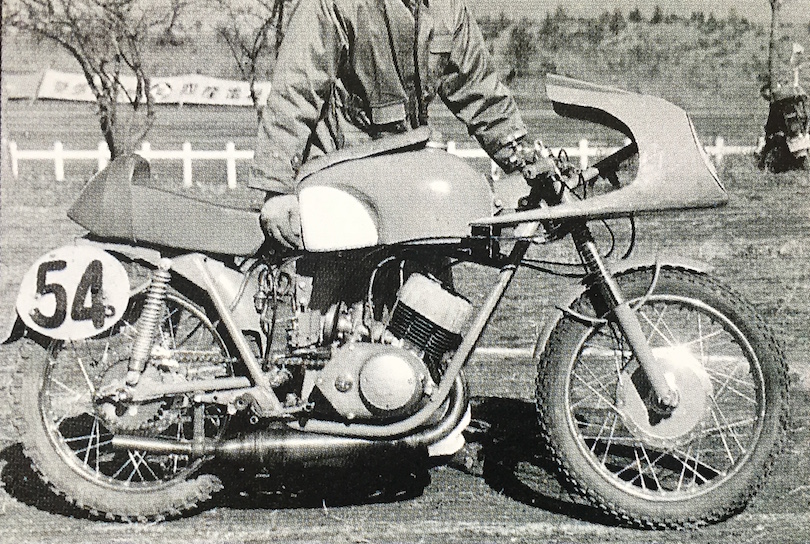

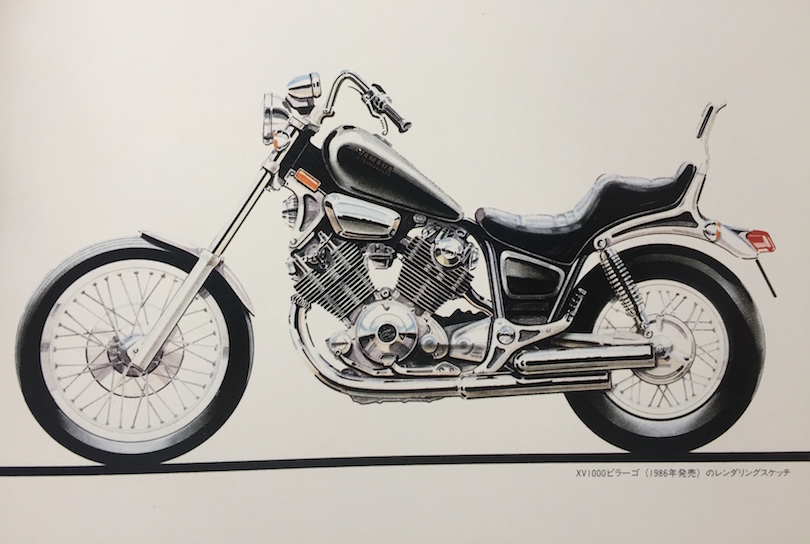

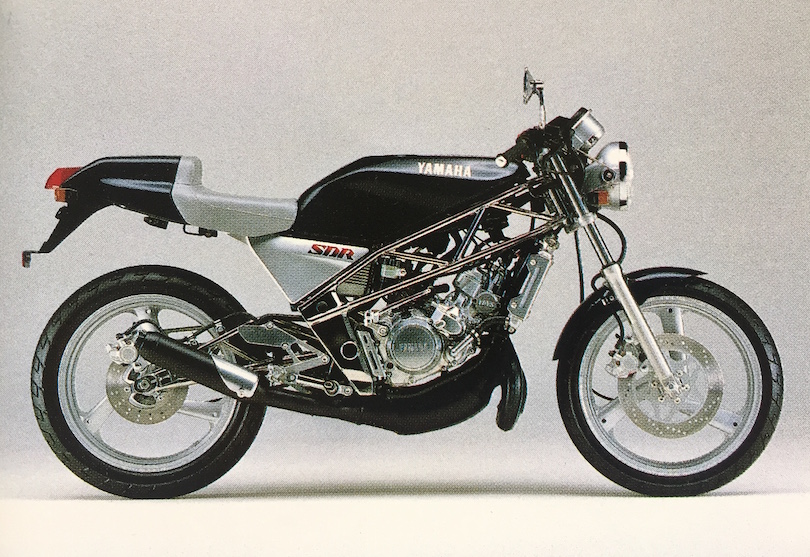

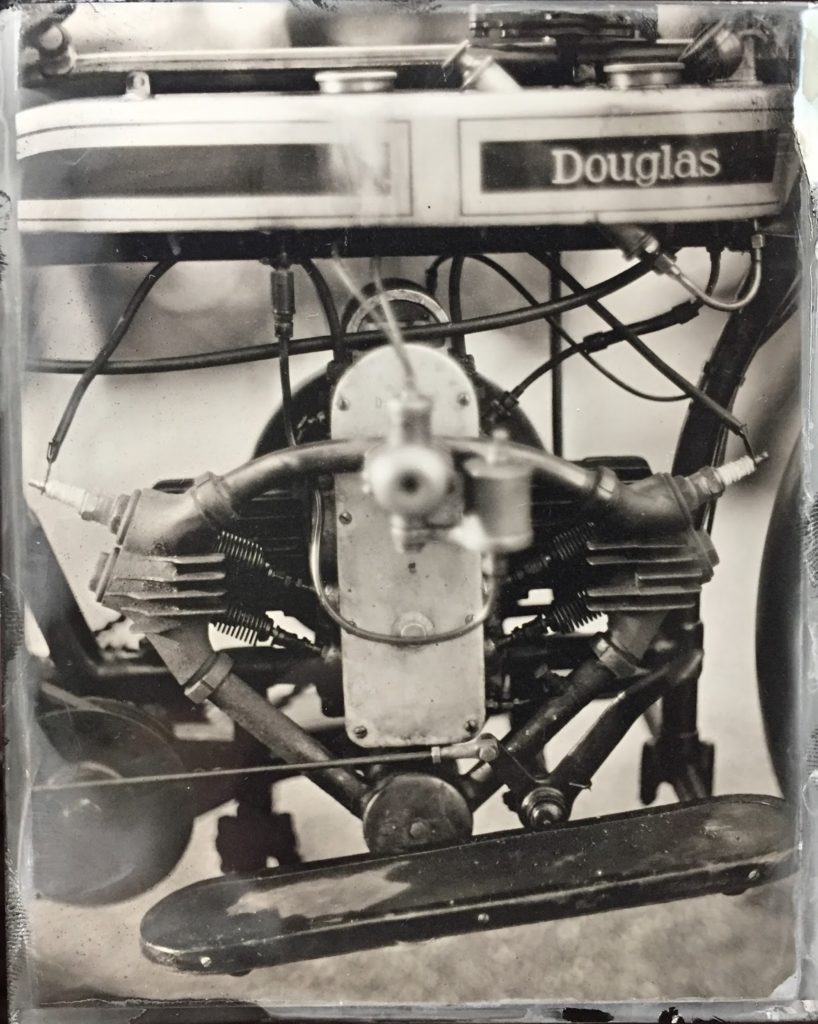

Ekuan's GK Design Group went on to work with Yamaha, and the VMax is one of Ekuan's most famous motorcycle designs. Far more famous is his ubiquitous red-capped Kikkoman soy sauce bottle of 1961, which was inspired by watching his mother struggle with transferring a large bottle of soy sauce into a smaller container for the table. The GK group also designed Japan's Bullet Train, corporate logos, and musical equipment. Kenji Ekuan was awarded the 'Golden Compass' award in Italy for his lifetime of brilliant design. Ekuan was born on Sep.11th 1929 in Tokyo, and Feb 10, 2015.

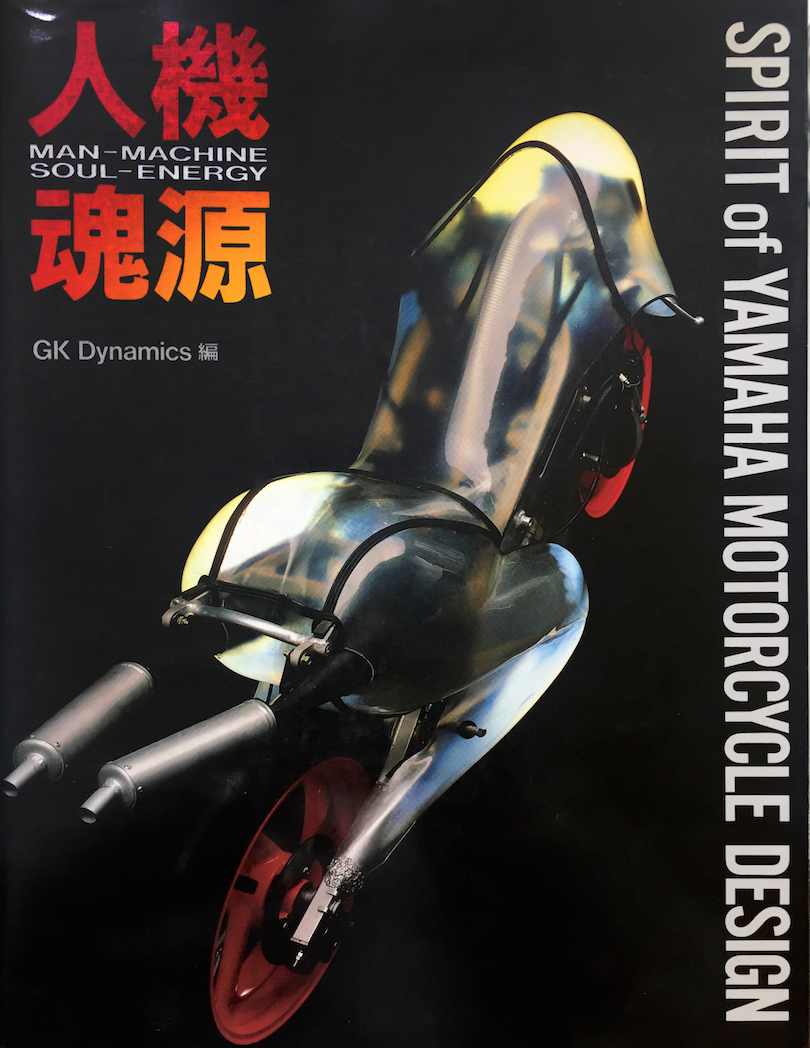

According to Yamaha, GK Design Group was responsible for nearly all of their motorcycle designs until very recently. In 1989, a separate division within GK Design Group was formed specially to deal with vehicle design, GK Dynamics, which also contracted with Toyota. It wasn't until 2014(!) that Yamaha formed an in-house design team, headed by Akihiro 'Dezi' Nagaya.

I've been familiar with the unorthodox design philosophy of GK Dynamics since 1989, when they published 'Man-Machine-Soul-Energy: the Spirit of Yamaha Motorcycle Design'...which I've always referred to as the 'Yamaha Sex Tract', as it is the first published motorcycle design document which explores the erotic and sometimes explicitly sexual nature of our relationship of "the second most intimate machine" (my quote - the first most intimate is, of course, the vibrator).

I recommend reading the book if you're a student of design, or would like to explore how differently the Japanese designers in Kenji Ekuan's firm thought about and discussed their work - it's a fascinating glimpse into a wide-open mind and industrial design philosophy, and I doubt any such discussion was ever held at Harley-Davidson or BMW! And I reckon few industrial designers working for major corporations have publicly acknowledged the debt of modern design to DADAist artist Marcel Duchamp. It's remarkable stuff.

Here's a sample from the book, written by current GK Dynamics President Atsushi Ishiyama:

"When I first came into contact with the motorcycle as an object to be designed, my first impression was that it is extremely sexy, even considered in terms of pure shape, the single cylinder engine is truly phallic...the part where the engine connects to the frame is thick, giving it the very shape of a sex symbol. The muffler also has the unique glow of metal, making it look just like internal organs. The tank has a richly feminine curve, and the metal frame bites tightly into the engine like a whip. I am certain the the designers did not have this aspect in mind, but it is quite a shock to anybody who suddenly comes into contact with it for the first time. The mechanical parts of the engine, the suspension...as well as all other structural parts give the impression of a sexual analogy. The first time I saw one, I felt like I had come into contact with a very abnormal world.

I feel that such works as 'Nude Descending a Staircase' and 'The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors' by the father of modern art Marcel Duchamp were the first artistic expressions of eroticism through mechanism....Duchamp's fresh approach is seen in his use of mechanism as his means of expression. The motorcycle is also created upon the basis of a thoroughgoing desire to create a loveable artifical life through a mechanical assembly of the mechanism of human sensitivities."

No matter your taste regarding the VMax or other Yamaha products, designers Ekuan and Ishiyama have created design for the ages, and have long been an inspiration of mine.

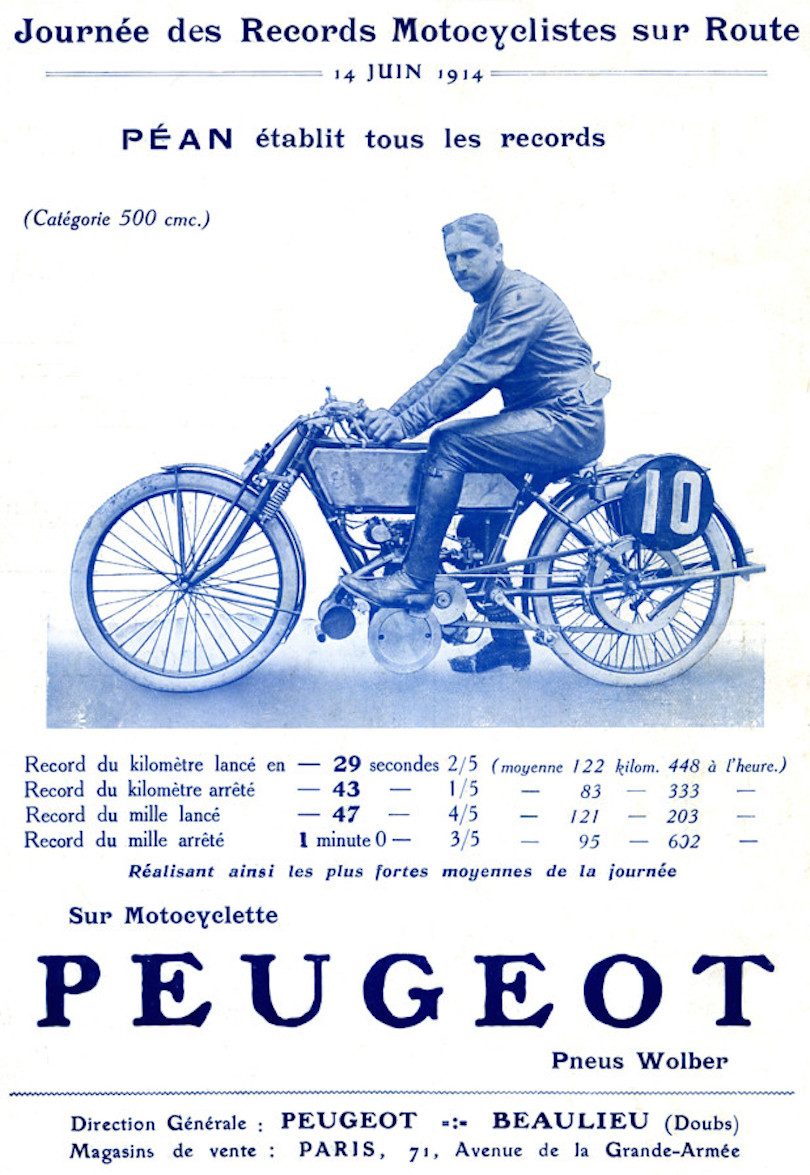

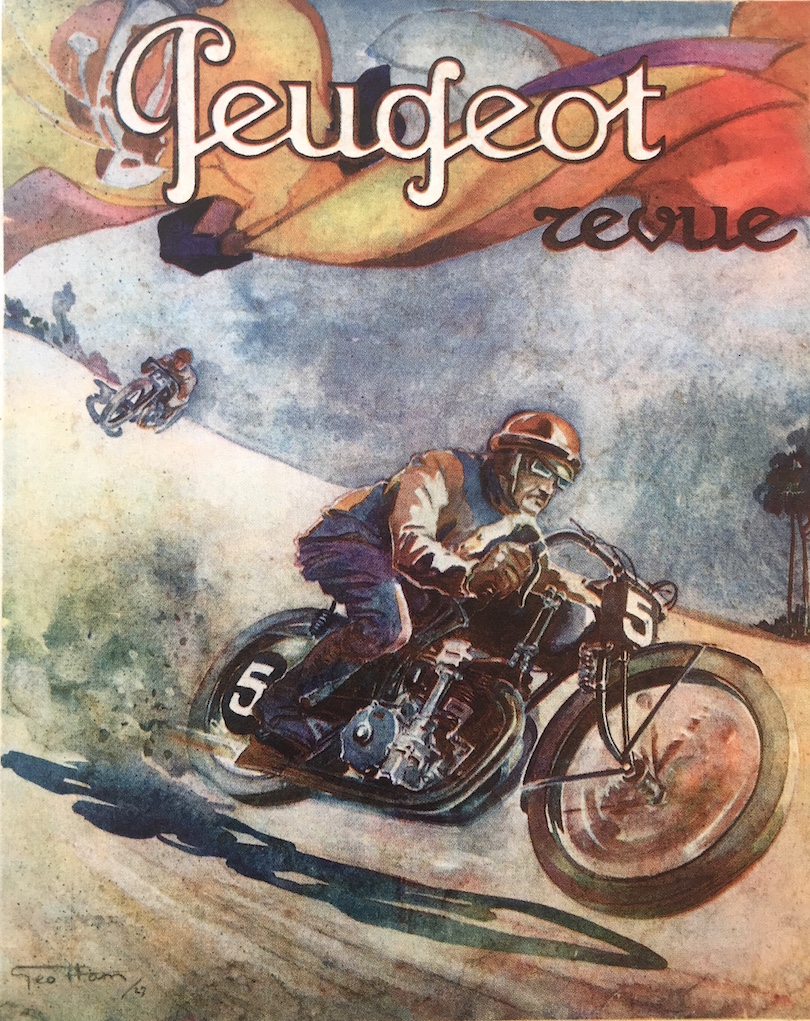

The Lost Peugeot Racers

Here's a fun fact: Peugeot is the oldest motorcycle manufacturer in the world, since 1898. Sorry Harley, sorry Indian, the French got there first...but you knew that, right? Most American factories based their early engines on a French design - the DeDion motor - whether copied or licensed (except for Pierce, who copied a Belgian design, the FN four!). But Peugeot's heyday as the world's preeminent force in two- and four-wheel racing was so long ago it's nearly forgotten today.

Les Charlatans

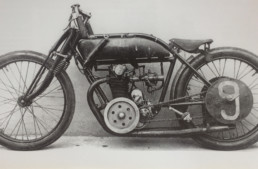

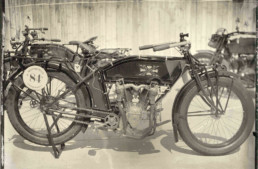

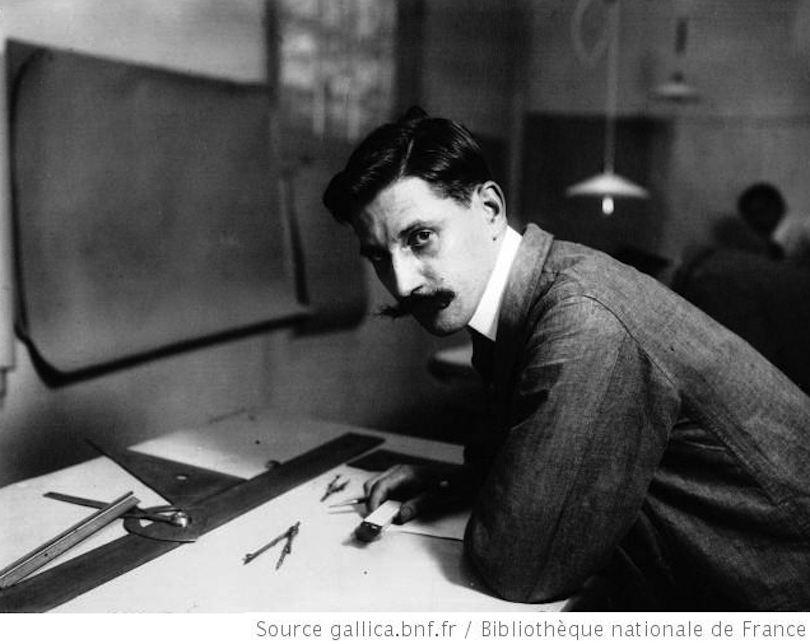

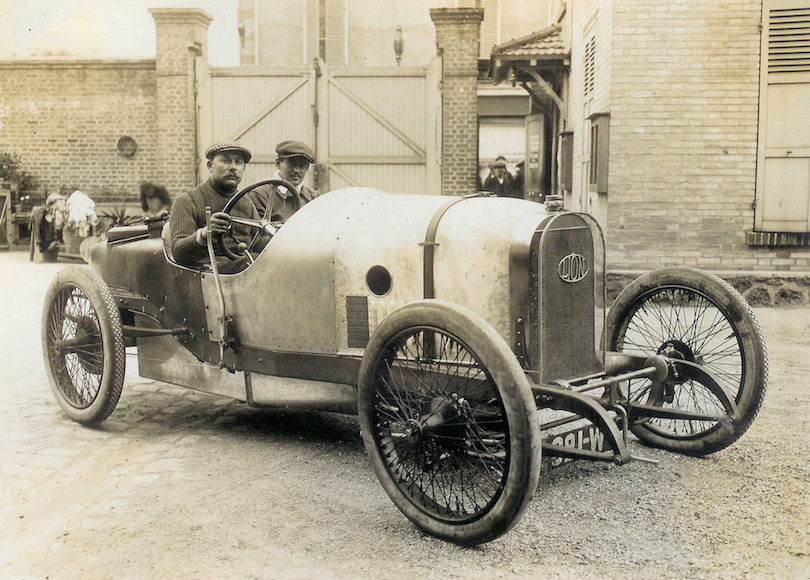

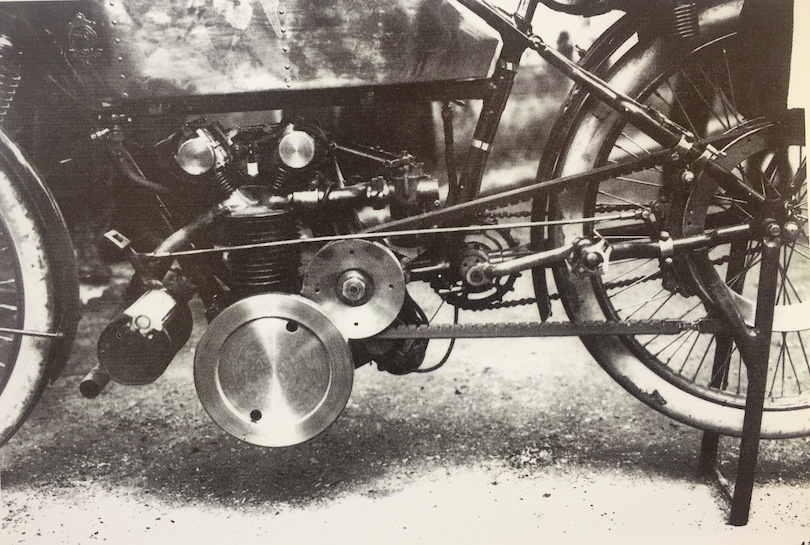

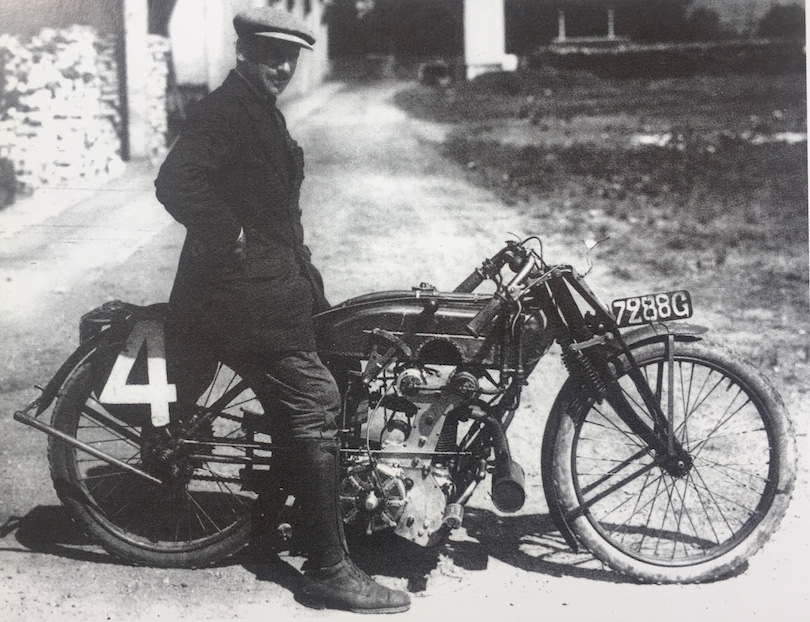

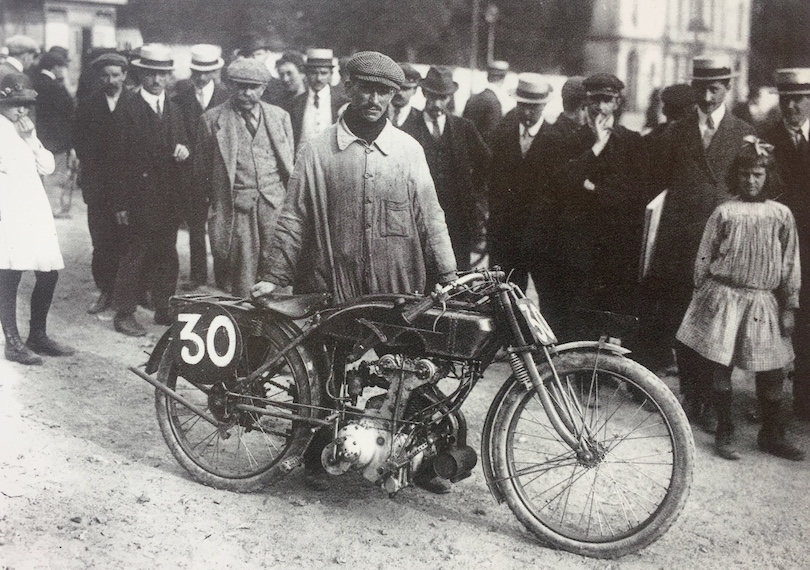

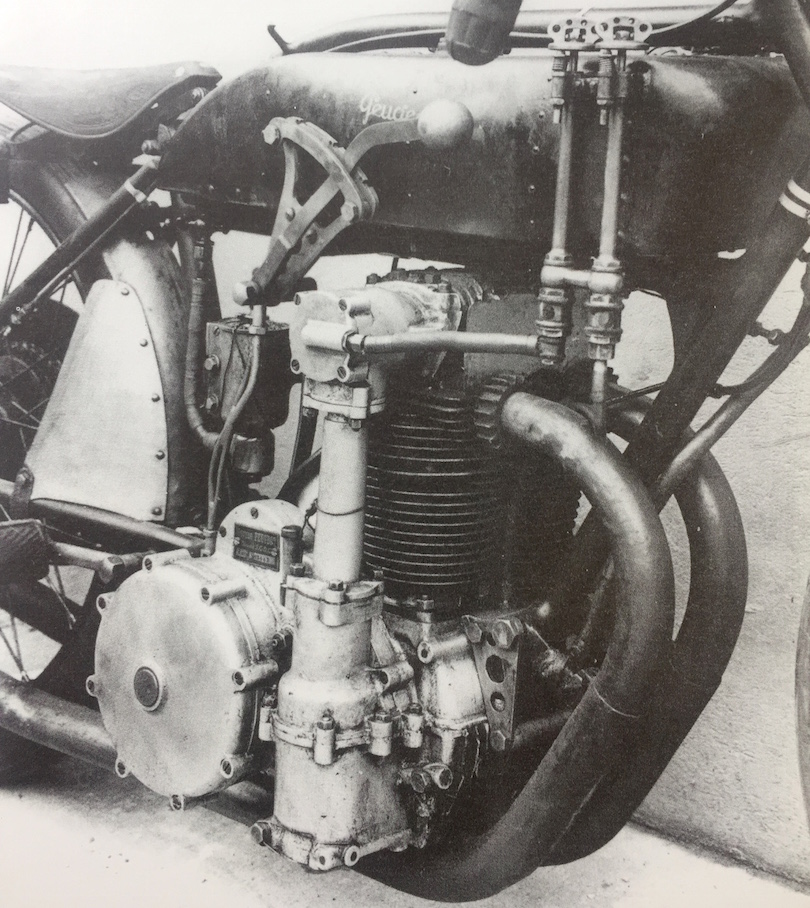

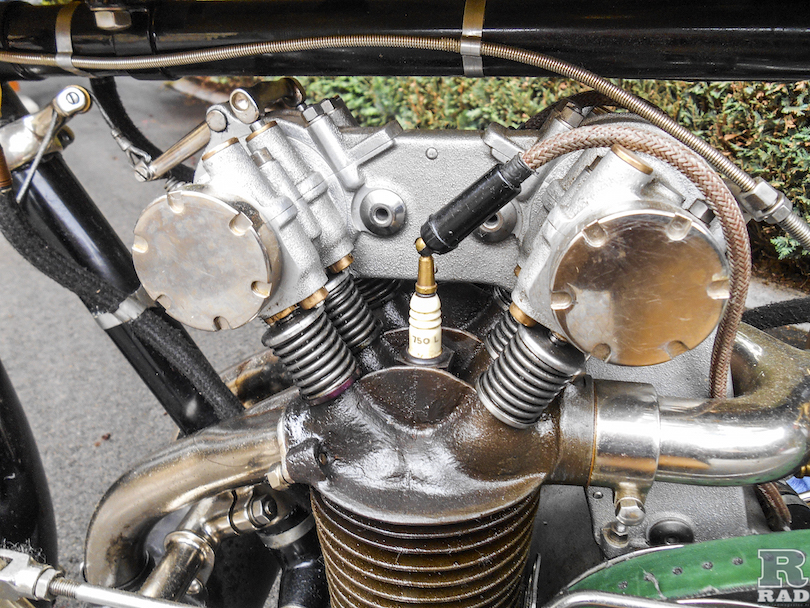

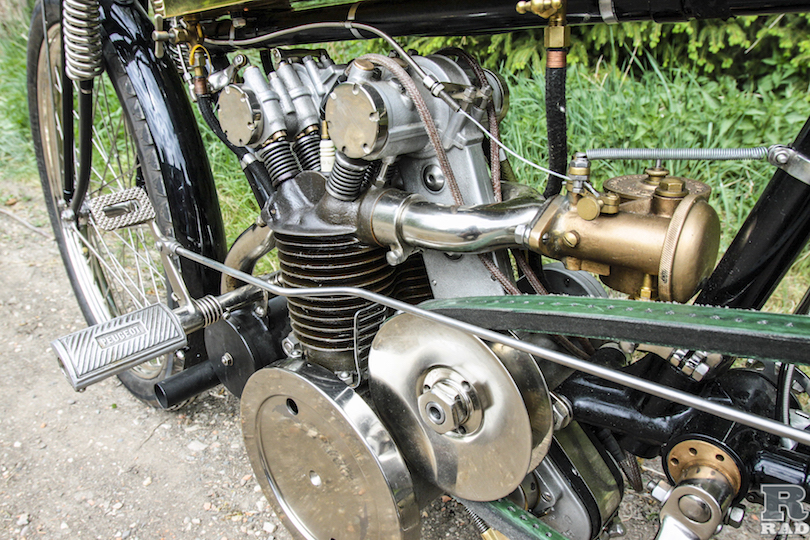

While Peugeot's early v-twins (as used by Norton et al) were reliable and reasonably fast in the 'Noughts, in the 1910s Peugeot débuted the most technically sophisticated engine designs in the world, first for automobile racing in the burgeoning Grand Prix series, then in a series of remarkable motorcycles. In 1911, Swiss engineer Ernst Henry was commissioned by 'Les Charlatans' (Peugeot racing team members Jules Goux, Georges Boillot, and Paul Zuccarelli to draw up a new four-cylinder racing engine from ideas they'd discussed. Henry wasn't a 'qualified engineer' but a draughtsman, with enough experience in motor design already (for boats and cars) to have caught the attention of the Peugeot team drivers.

Post WW1

In 1919, the Peugeot OHC motorcycle project was revived by a new engineer, Marcel Gremillon, who added a clutch and 3-speed gearbox with all-chain drive. Henry's original 500M was a nightmare for even simple maintenance, with its one-piece casting for both cylinders/heads and 8 valves, so even simple tasks like valve adjustment and decoke required a total engine strip.

The Recreation of a 500M

- 'Motos Peugeot, 1898-1998; 100 ans d'Histoire', Bernard Salvat / Didier Ganneau, 1998, EBS

- The Automobile, 'Peugeot Racing Engineers: Ernest Henry', Sébastien Faurès Fustel de Coulanges, 2012

- RAD magazine, 'Résurrection d'Une Peugeot 500 DOHC', Alain Jardy / Fabrice Leschuitta (photos)

- 'La Motocyclette En France; 1894 - 1914', Jean Bourdache, 1989, Edifree

- Bibliothéque Nationale de France digital archives

- Yves J. Hayat/ NewYorkParis

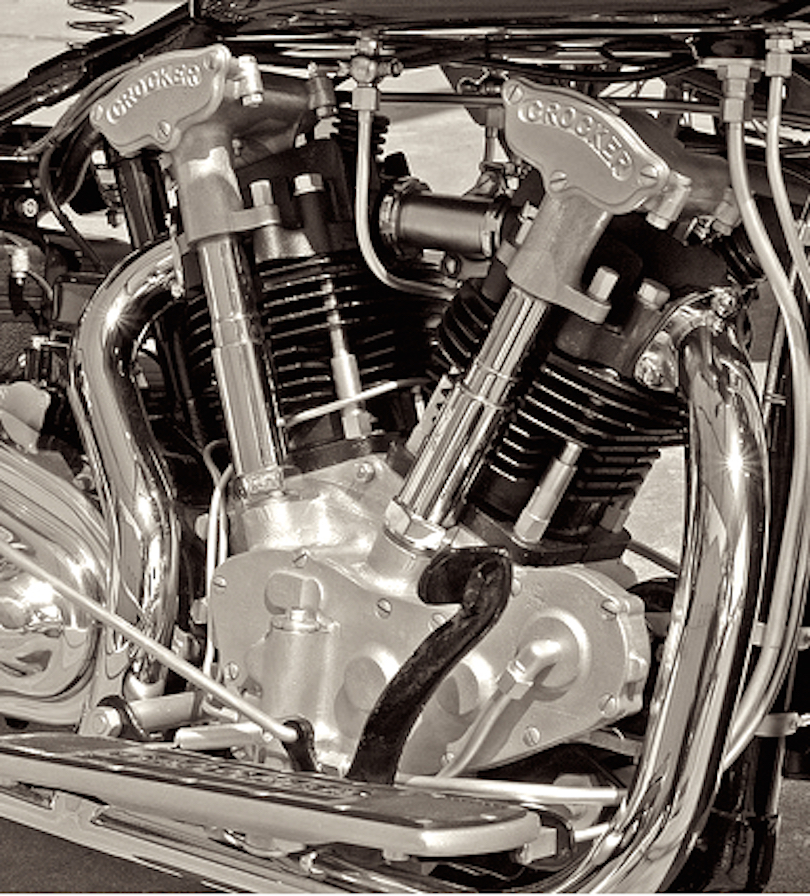

The Crocker Story

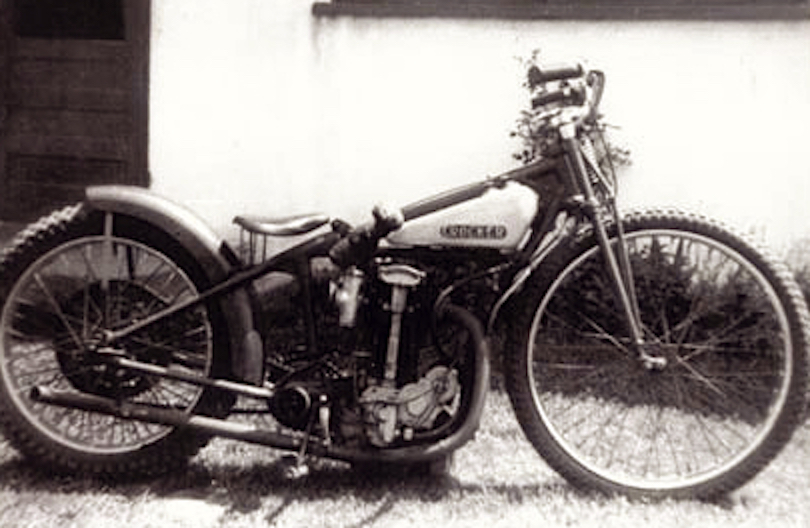

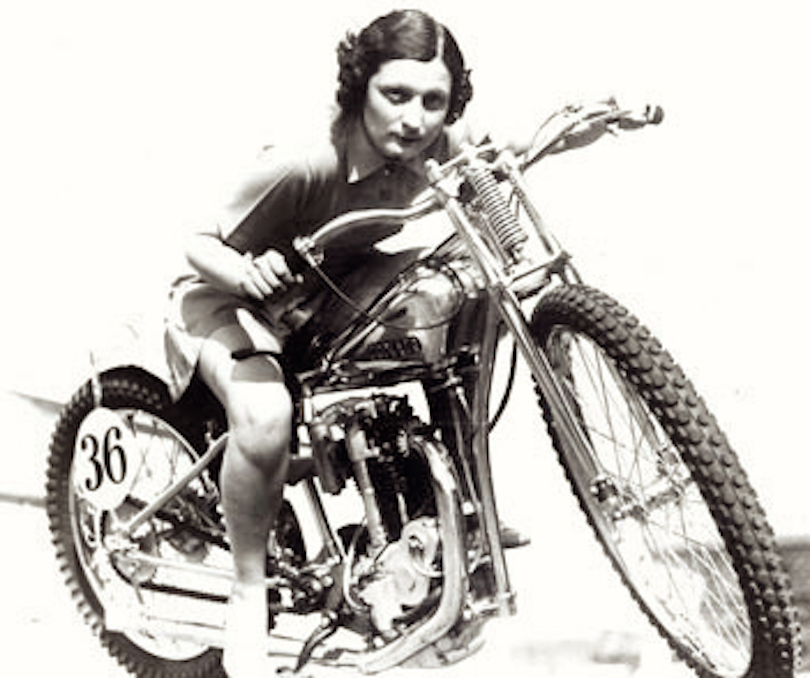

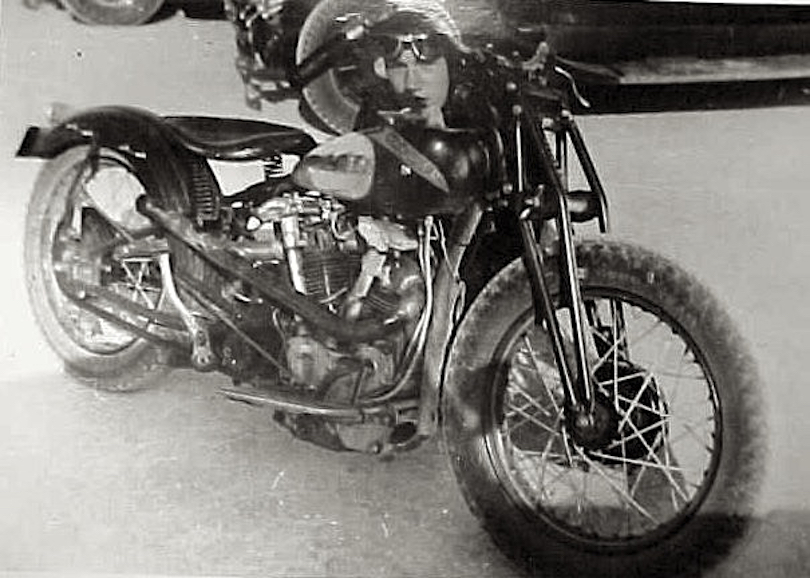

The story of Crocker motorcycles has been obscured by tall tales and myths since the very day they were introduced, first as Speedway racers, then big V-twins, and finally a scooter, all built before official US involvement in WW2 put a halt to civilian motorcycle production. Wading through the murk around this famous American name, one bumps against vested interests and fast-held opinions, but enough facts emerge to which we can anchor our tale. What is definitely known is they have skyrocketed in value in the past decade, filling many spots on our Top 100 Most Expensive Motorcycles list.

The Crocker has rightly become a coveted and very expensive machine, deserving of its place on the Olympus of Motorcycles, with the Brough SS100, Vincent Series A Rapide, and Zenith Super 8; the world's first 100+mph production motorcycles. All were big, impressive V-twin Superbikes built in small numbers for a very discerning clientele...and all are very, very expensive today.

Road Test: Shinya Kimura's MV Masterwork

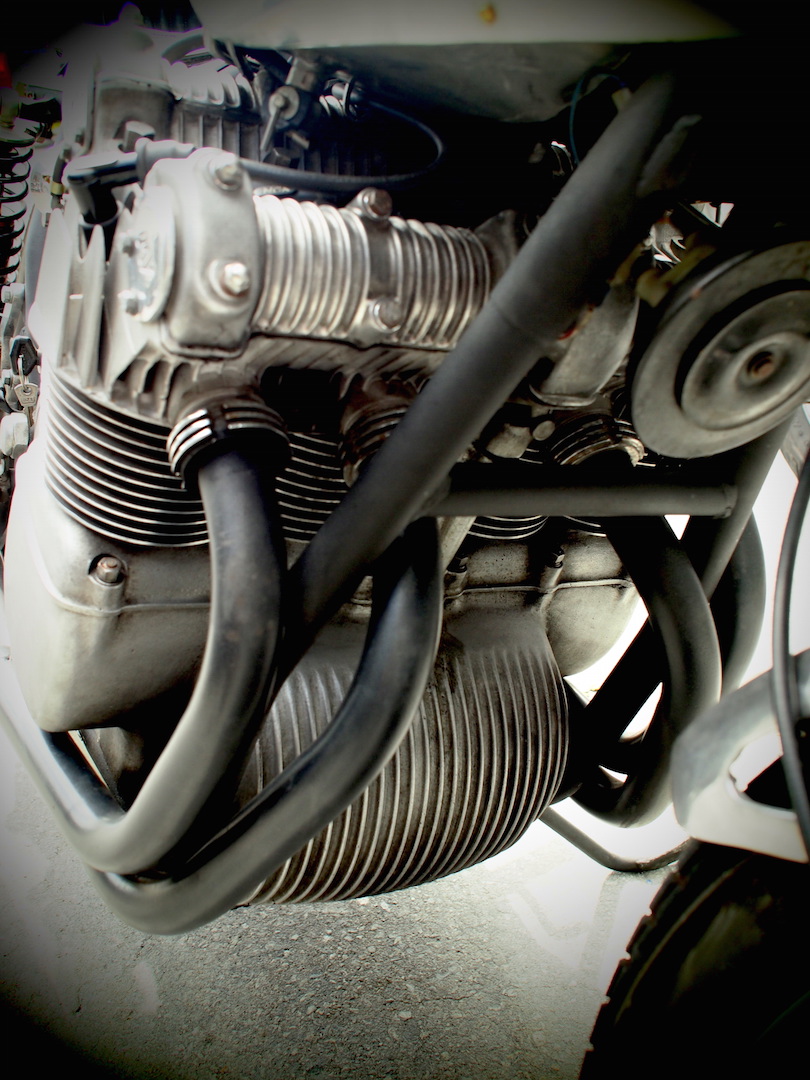

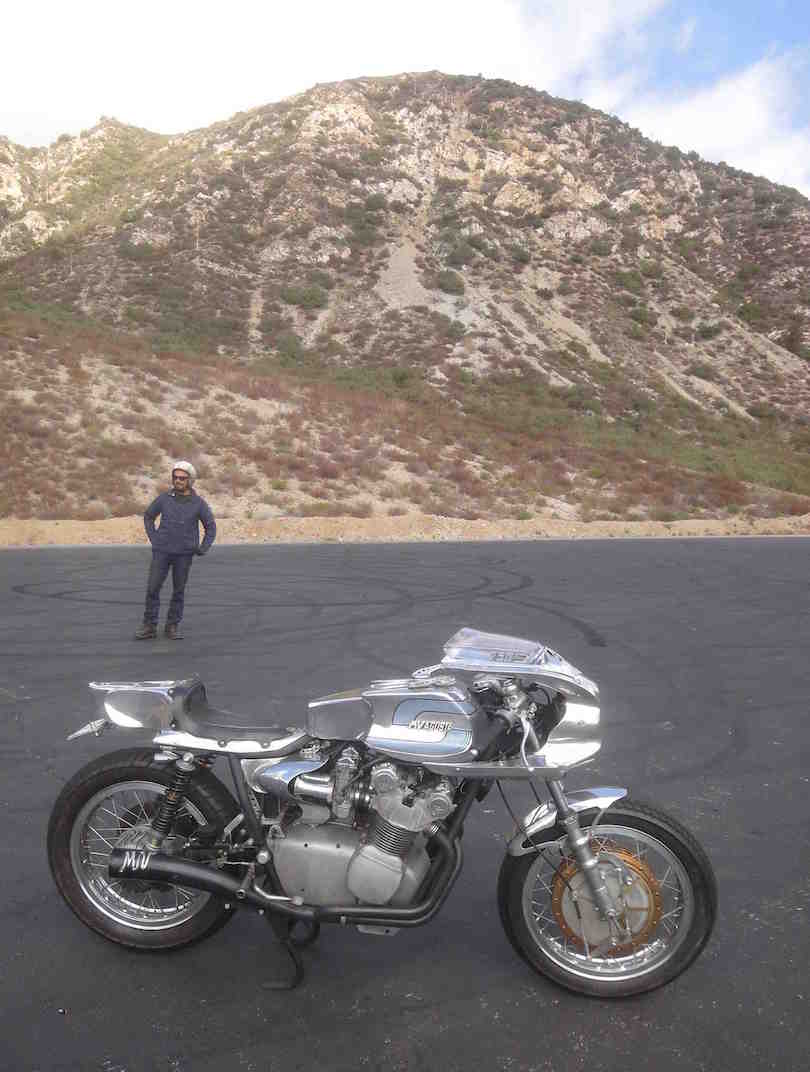

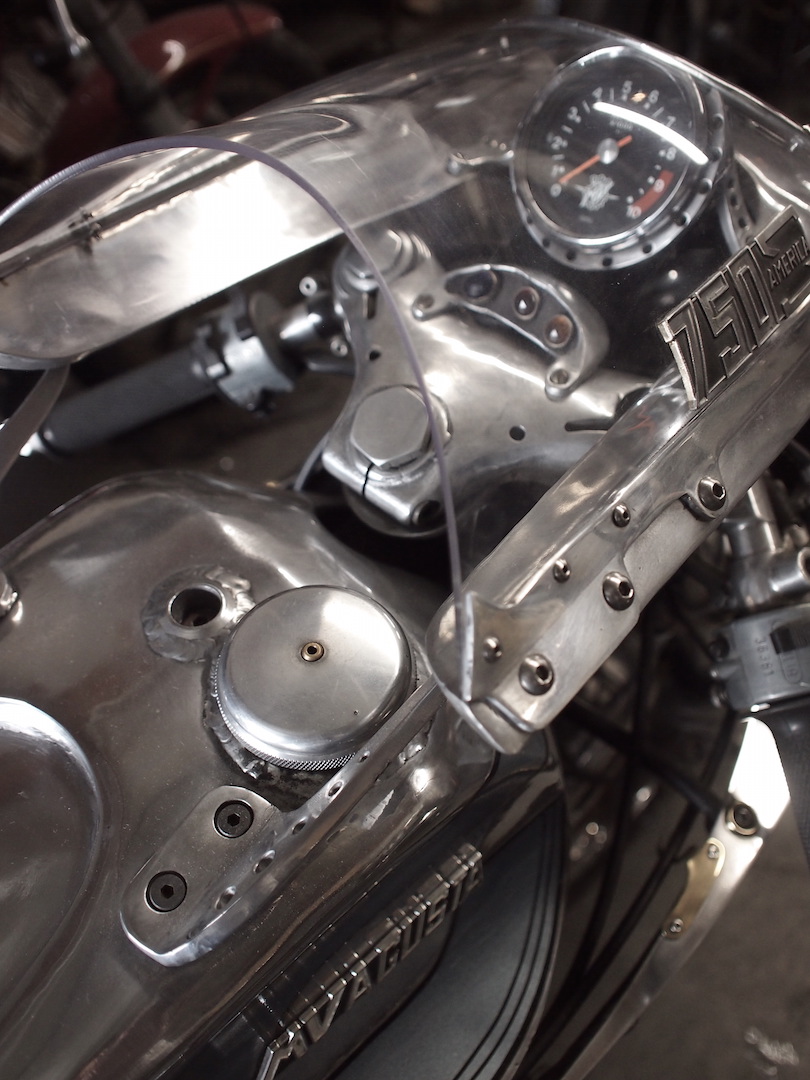

The original 1970s MV Agusta ‘4’ is legendary for its beautiful lines, and collectors scrabble when they come up for sale. To dare approach Count Domenica Agusta’s glamourous baby, intent on customization, is almost unheard of. In modifying a ca.1974 MV Agusta 750S, Shinya Kimura has kept the chassis intact, to the point of retaining the Count’s ‘you’ll never race this’ shaft drive, the first item every MV hotrodder in history has ditched. Why? ‘I really like the radial fins on the final drive, it’s very pretty’. His attitude fits his self-described role as a coachbuilder; respect your chosen chassis, but clothe it in a bespoke suit. MV fours, though expensive and coveted, are hardly rare, and plenty have been racerized by the likes of Arturo Magni and Albert Bold. None look like the naked aluminum creature in these photos.

With stock power output about 66hp at a modest (today) 8000rpm, that kind of weight won’t be setting quarter-mile records. If the MV is to be ridden quickly, you need to employ the old single-cylinder racing trick of ‘maintaining momentum’, ie, fast into corners, hard over, don’t brake unless you’ve seriously underestimated the turn…or overestimated your gumption. Easy on a 350lb hotrod Velocette Thruxton, not so natural on a quarter-ton Latin legend with masterpiece bodywork.

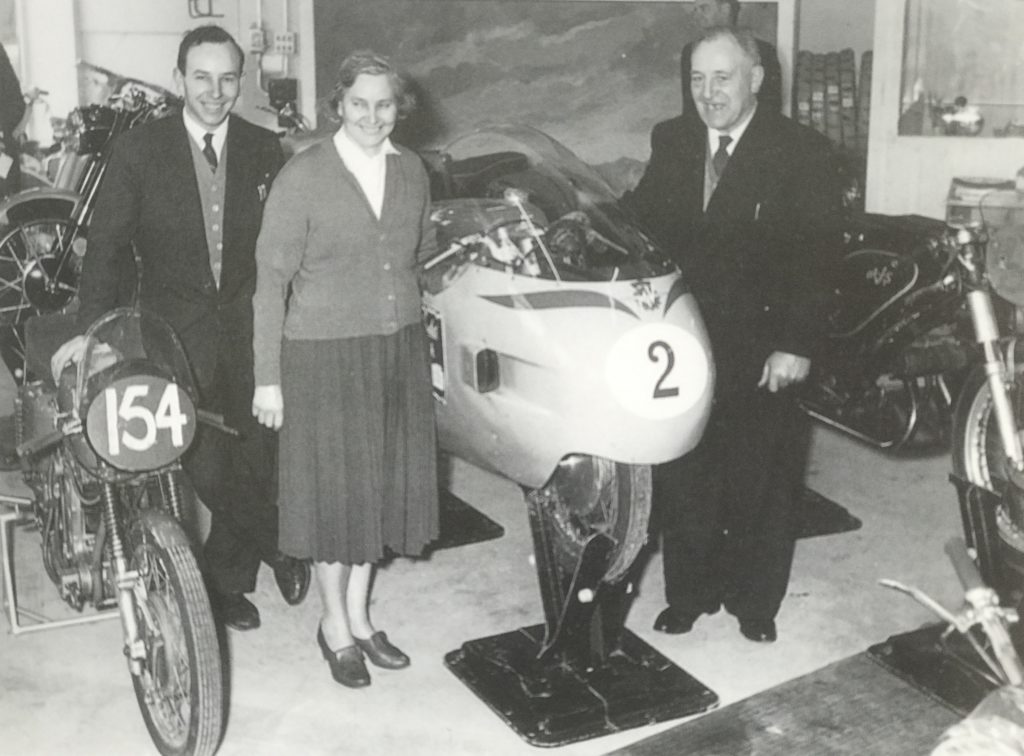

John Surtees

Written by Paul d'Orleans for Cycle World magazine, reproduced with permission.

He wasn’t a showman with movie star looks, like many World Champions; John Surtees had a sparrow’s physique, with a modest but intense demeanor, who suffered autograph hounds with a friendly noblesse oblige. No doubt he treated his rivals the same, giving very little away, his attention seemingly elsewhere…like memorizing every braking point at the Nurbrurgring or Isle of Man circuits. If you were close enough to observe his expression on the track, it meant you were about to lose your race to the most stylish and disciplined rider of the 1950s.

Jay Leno and the White Collection

It's not typical to auction a major classic vehicle auction for charity, but that's what the late Robert White stipulated in his will. Jay Leno purchased his collection of 17 Brough Superiors last year, with the funds headed entirely to the hospital Mr. White wanted to support; a cancer treatment center in an area of Britain not well served. Jay's video is a testament to a friend, and a plug for the upcoming Bonhams auction of the remainder of Robert White's motorcycles, cars, Leicas, etc. It's worth a look!

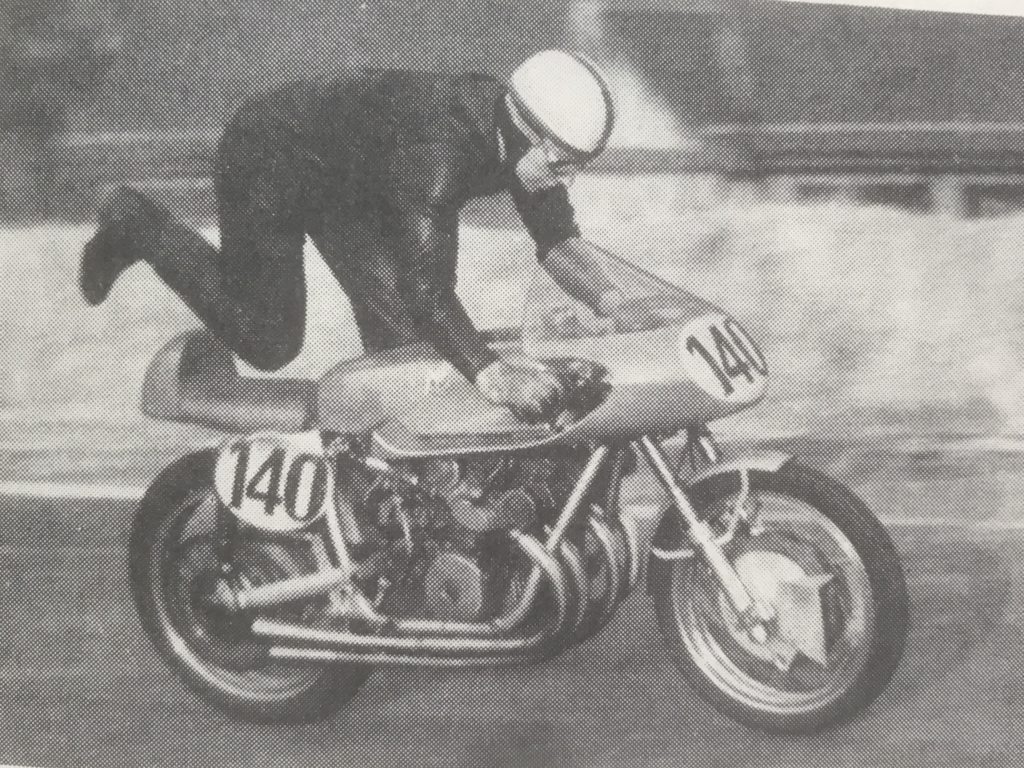

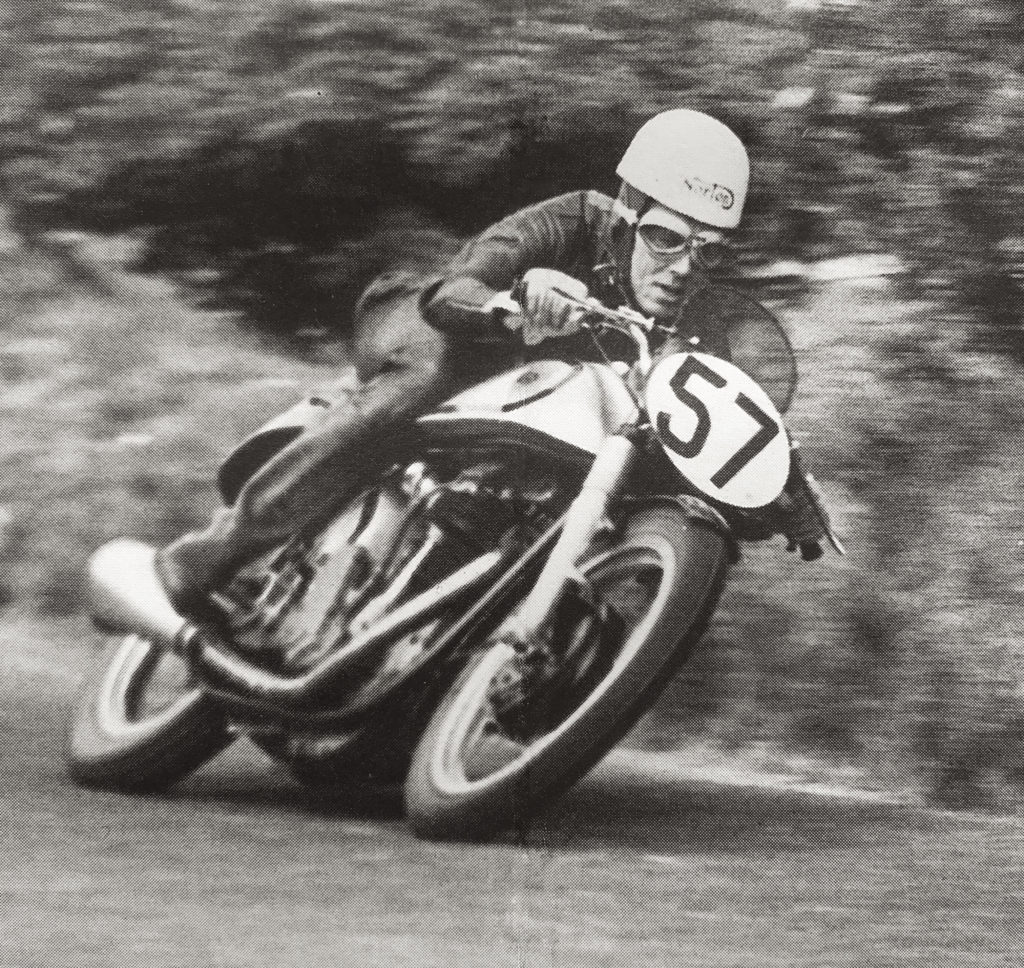

Rara Avis: The Unique Lynton Racer

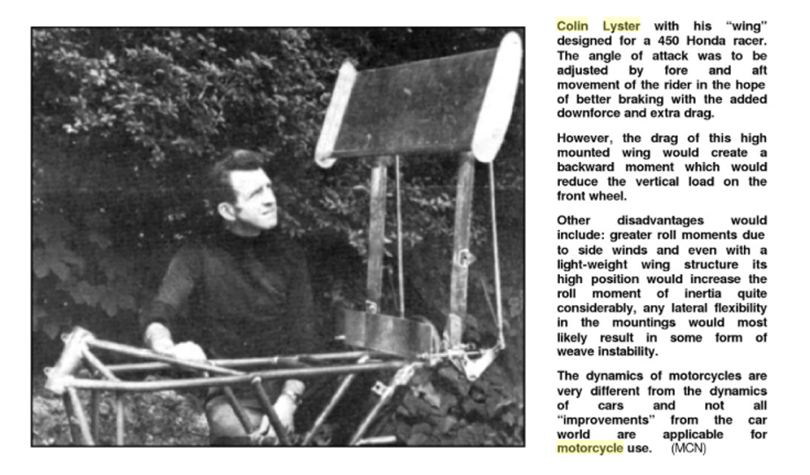

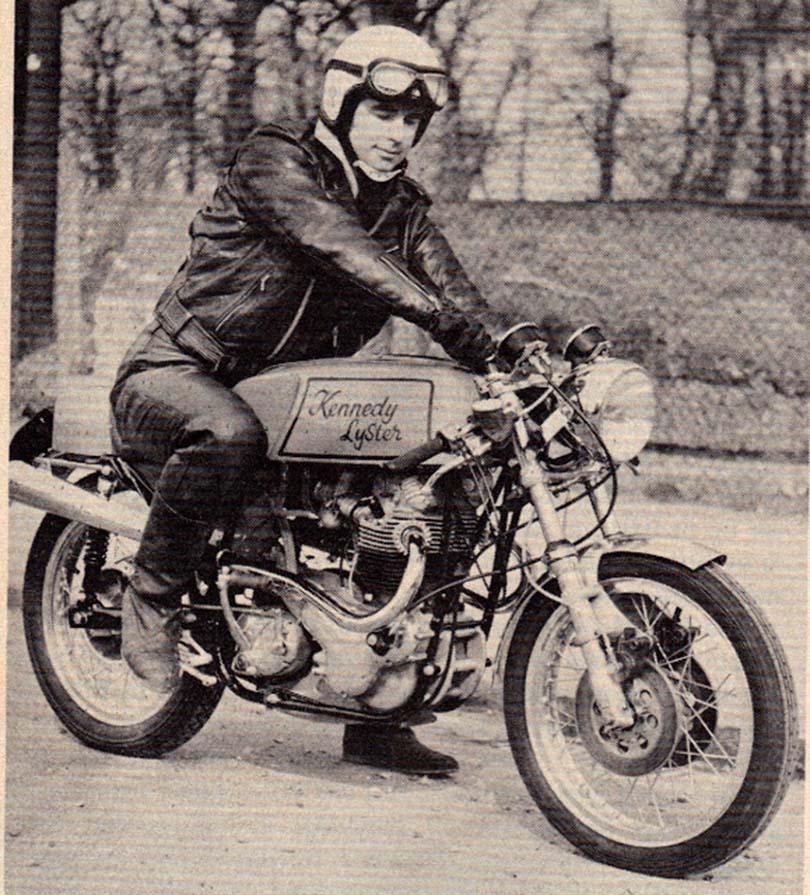

Colin Lyster isn’t a household name, unless you’re a hardcore café racer fan, in which case, he’s a demigod on par with Dave Degens and the Rickman brothers. A former Rhodesian road racer, Lyster moved to Britain in the early 1960s, and set about re-framing Triumphs and Hondas to reduce weight and improve chassis stiffness. His frames were ultra-rigid and half as heavy as comparable Norton item; he typically discarded the lower frame rails, using the engine as a stressed member, and thinwall tubing of smaller diameter than considered prudent for a street machine.

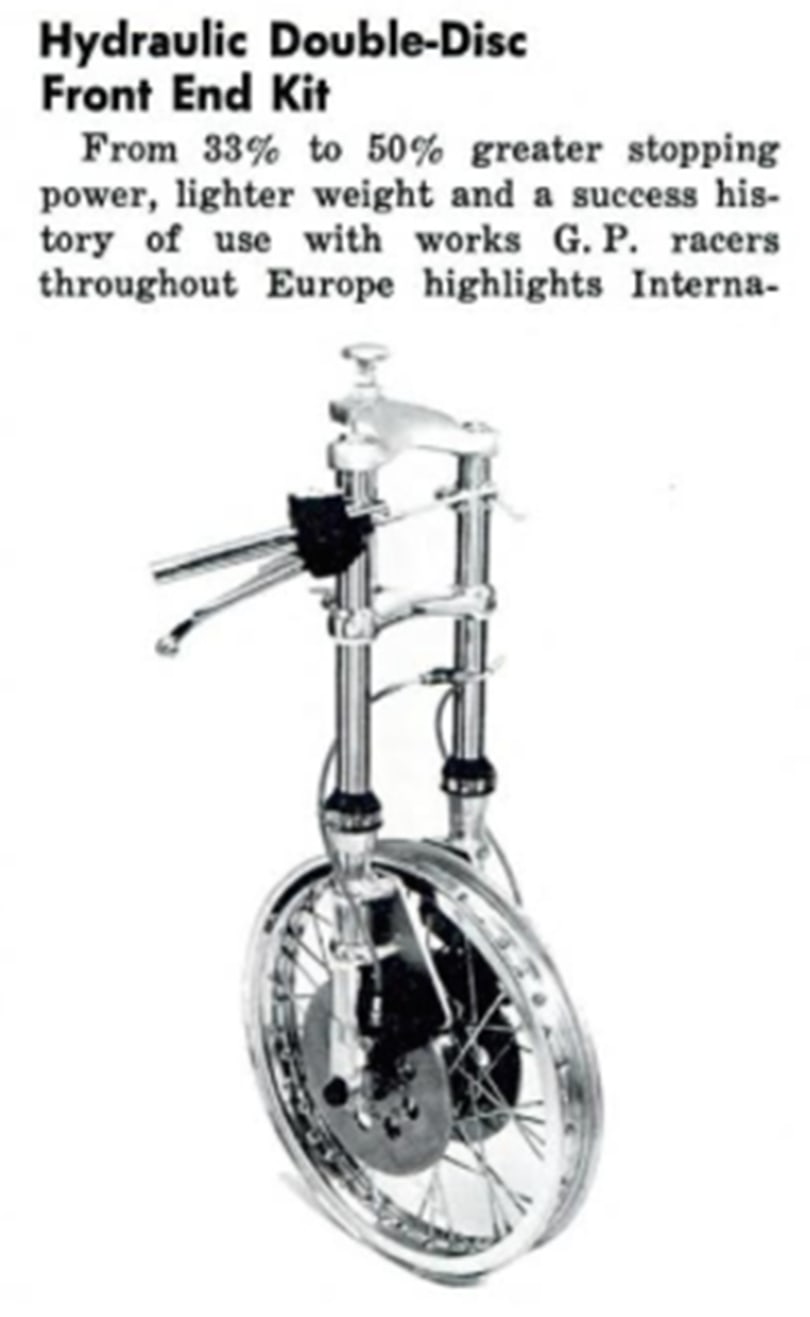

Still, hotshot riders can’t resist a road racer with lights, and a few Lyster-framed roadsters can be found in books on the café racer craze. Lyster’s frame output was low, but his impact on the industry was outsized. He developed the first triple-hydraulic disc braking systems for motorcycle racing teams in the mid-1960s, using specially adapted Ceriani road race forks and his own fabricated swingarms, with his own cast iron discs. Triple juice discs became a must-have item on winning road racers; Lyster began selling kits to the public in 1971. After failing to interest the British motorcycle industry in his product, he sold his patents to AP Lockheed. Ironically, it was Honda who first used hydraulic discs on production motorcycles, in 1968. Still, it was Lyster’s patent, and he changed motorcycling forever.

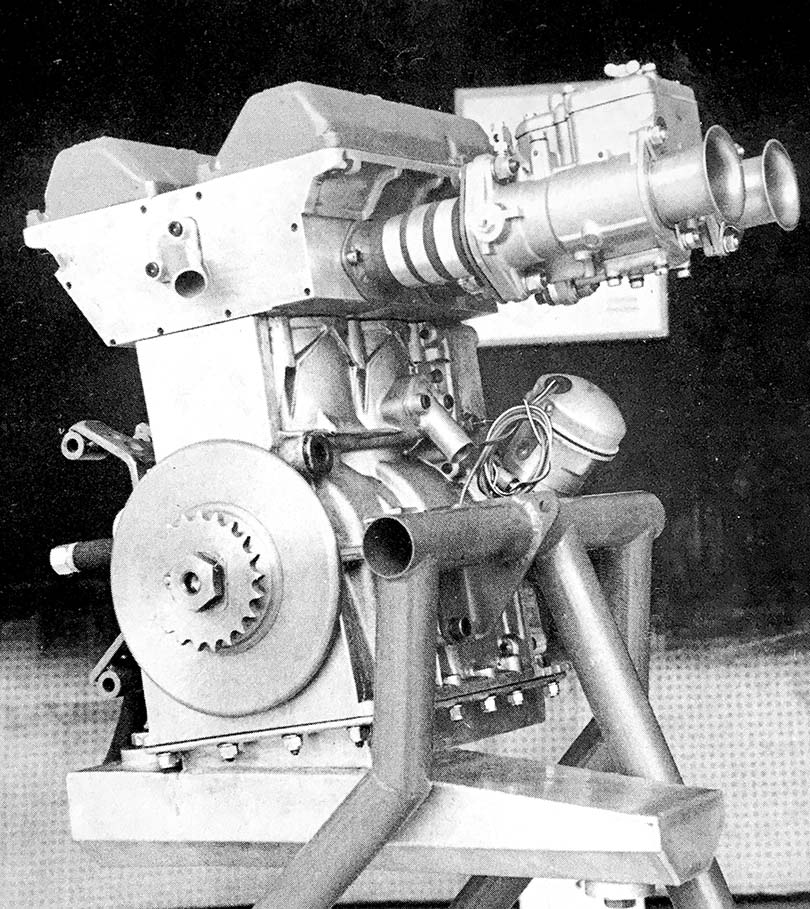

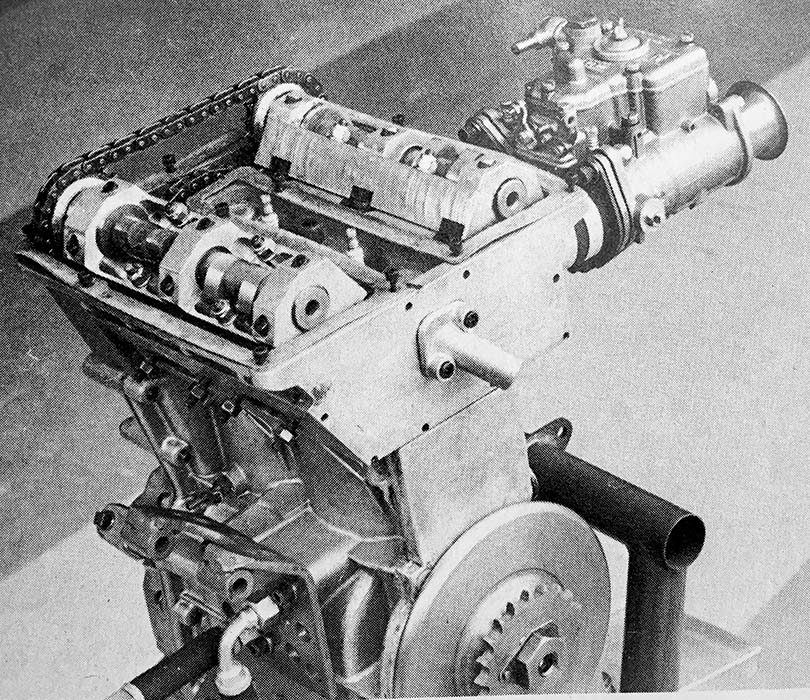

By the mid-1960s, the British motorcycle industry had given up on Grand Prix racing, but enterprising builders hadn’t. Colin Lyster thought a reasonably-priced, competitive engine could be built from automotive parts, and he cut a water-cooled 1000cc Hillman Imp 4-cylinder car motor in half, and built a DOHC, 8-valve cylinder head for it. Interestingly, the Imp motor was designed by Leo Kuzmicki, the Polish ‘janitor’ who was ‘discovered’ by Joe Craig, race chief of Norton, as having been a research scientist in combustion theory before becoming a WW2 refugee. It was Kuzmicki who kept the Norton Manx engine competitive a decade after its sell-by date, extracting ever more power from the aging single-cylinder design. After leaving Norton, he moved to the Rootes Group, and designed the extremely reliable and very fast Imp motor.

As reported in Cycle World in July 1968, Lyster’s Imp-engined ‘Lynton’ racer was a collaboration with Paul Brothers, and used an ultralight Lyster full-cradle frame, with his own triple disc setup. The cylinder head is a chunk, and the side-draft Weber DCOE carb doesn’t inspire confidence that the watercooled engine is light. The builders claimed 60hp from the motor, which used a 180-degree crankshaft, a modified Hillman part, as were the rods. Slipper pistons from Mahle and cams by Tom Somerton painted a picture of speed, and the projected price of £300 undercut a Matchless G50 single-cylinder SOHC motor by £75. Orders were not forthcoming, though, as the project needed more development, and it remained yet another British ‘what if?’ It seems only the prototype motorcycle was built, although Lynton offered a full four-cylinder version of its special cylinder head to Imp rally drivers; a few of these are floating around, including rumors on one cut in half for a motorcycle!

Britain’s H&H Auctions turned up the sole Lynton racing motorcycle; it’s an uncompromised beast with a pur sang pedigree, and a lot of near-forgotten stories surrounding its build. Colin Lyster moved to the USA in the early ‘70s, and worked with Canadian national champion road racer Ed Labelle to build Lyster-Labelle racers, using Triumph Bonneville motors in lowboy frames with triple discs. Only a few were built before Lyster moved on to New Zealand, where he carried on with other projects until his death in 2003.

Road Test: the New Brough Superior SS100

The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world's rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

Want to get bikers up in arms? Revive a hallowed brand. Established manufacturers get a pass when producing ugly or ill-considered motorcycles, and nobody questions their right to exist, but a new manufacturer using an old name fights steep resistance, no matter how committed it is to the old name. Brough Superior owner Mark Upham is doing his best to honor the spirit of the late George Brough, which is probably impossible in the 21st Century, because Brough invented a genre – the luxury motorcycle – that was bombed out of existence in World War II.

Brough Superiors were built between 1919 and 1940, and immediately earned a reputation for quality, innovation, handling, speed, and beauty.

The new Brough Superior lifts its tank design directly from a 1920s Pendine racing model, which used triple straps to bind tank to frame; it’s the visual DNA of a Brough Superior, and a feature Mark Upham insisted on. Underneath that old-school tank (built in polished aluminum) we leave the past behind and enter the 21st Century, with a unique motor and innovative chassis.

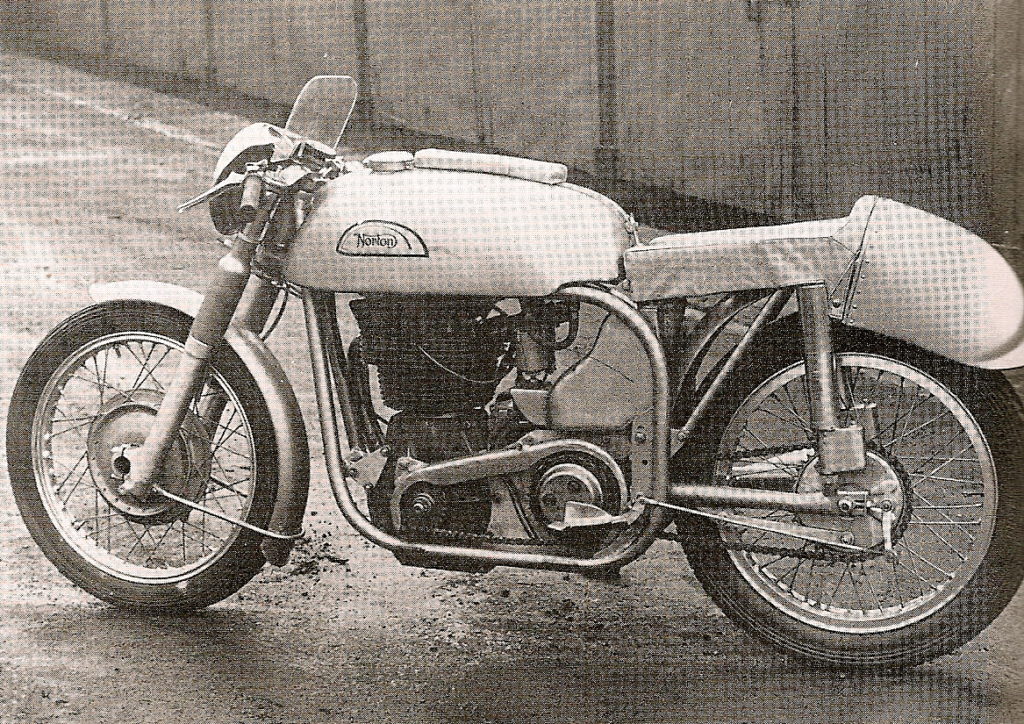

The First 'Triton' - A Prewar Cafe Racer

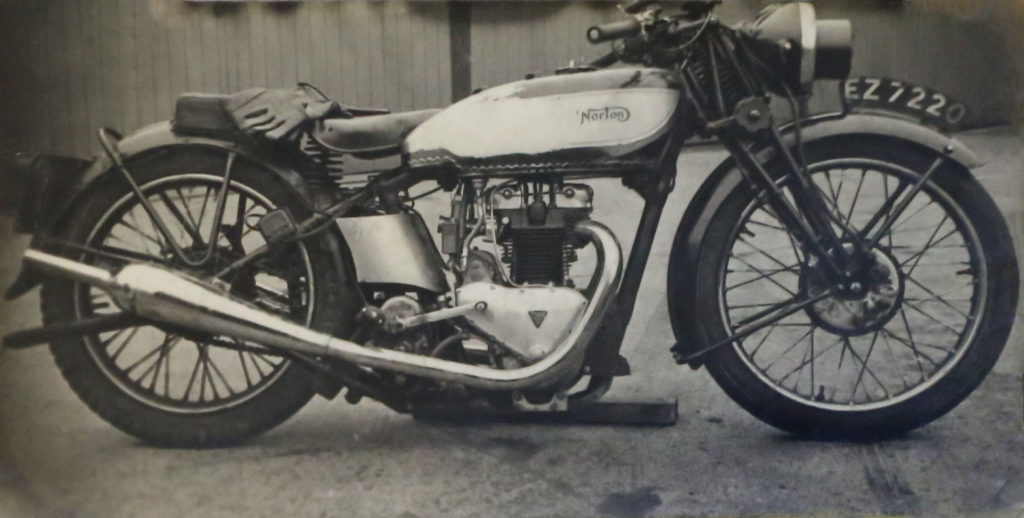

Back in 2008, I wrote about the McCandless brothers' invention of the first modern swingarm motorcycle frame in 1944. Norton race chief Joe Craig took note of this radical new chassis, leading Norton to purchase the rights to the McCandless design in 1949. Geoff Duke debuted the McCandless-framed Norton in 1950 housing a factory Grand Prix racer, and sweet-handling design became known as the 'Featherbed'.

Rex McCandless and his brother Cromie were an interesting pair, devoted to motorcycle engineering and racing, and changed the motorcycle industry forever without the need for an engineering degree. Rex famously wrote, "I never had any formal training. I came to believe that it stops people from thinking for themselves. I read many books on technical subjects, but always regarded that as second-hand knowledge. I did my best working in my own way." It slipped my attention then, but it seems the McCandless brothers also seem to have invented the most iconic custom motorcycle of the cafe racer era - the Triton, a Norton/Triumph hybrid.

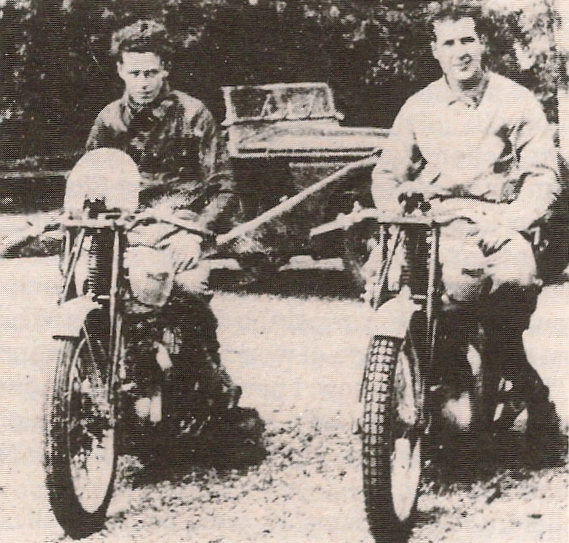

Rex McCandless tuned and raced his own motorcycles before WW2, first turning his attention to a new twin-cylinder Triumph Triumph Tiger 100 in 1940. His home-tuned Tiger was was faster than the factory-tuned bronze-head Tiger 100 of his friend, Artie Bell (future Norton Works racer), and Rex won the Irish 500cc Road Race and Hillclimb championships that year. While the motor was fast, the Triumph chassis made 'unreasonable demands of its rider'. The story goes that McCandless began experimenting with weight distribution on the Triumph, and eventually designed his own frame, which became the Featherbed. But it seems he tried a known better-handling chassis first for his Triumph motor, and installed the Tiger engine in a racing Norton International chassis. He'd already proven his T100 engine faster than a racing Norton, but their chassis was the gold standard for handling. Thus the first Triton was born during WW2, as evidenced by photos in the VMCC Library, passed along to me by Dennis Quinlan.

Thankfully for us, the Norton also didn't live up to McCandless' idea of what a frame could be! He carried on experimenting; "I had noticed that when I removed weight in the shape of a heavy steel mudguard and a headlight, that the bike steered a lot better. It made me think about things which swiveled when steering. I was in an area about which I knew nothing, but set-to to find out. It seemed obvious to me that the rigidity of the frame was of paramount importance. That the wheels would stay in line, in the direction the rider pointed the bicycle, regardless of whether it was cranked over for a corner, and to resist the bumps on the road attempting to deflect it. Of equal importance was that the wheels would stay in contact with the road. That may seem obvious, but fast motor cycles then bounced all over the place. I decided that soft springing, properly and consistently damped, was required."

McCandless knew his Benial had the best-handling frame in the industry, and approached Norton with a challenge, and the intention to sell his design. Norton's 'plunger' Garden Gate frame had a tendency to break, and handled like a camel. Joe Craig made the frames heavier, to stop the breakages, but in McCandless' view, this showed an insufficient understanding of the stresses involved on the chassis, "...all they did was to fix together bits of tube and some lugs.." In 1949, he told Gilbert Smith, the Managing Director of Norton, "You are not Unapproachable, and you are not the World's Best Roadholder. I have a bicycle which is miles better!" The Norton brass set up a test on the Isle of Man, where a relative of Cromie McCandless' wife was Chief of Police. They closed the roads, "Artie Bell was on my bike, ultimately christened the Featherbed by Harold Daniell. Geoff Duke was on a Garden Gate and both had Works engines. Gilbert Smith, Joe Craig and I stood on the outside of the corner at Kate's Cottage. We could hear them coming from about the 33rd [milestone]. When Geoff came through Kate's he was needing all the road. Artie rode around the outside of him on full bore, miles an hour faster, and in total control. That night Gilbert Smith and I had a good skinful."

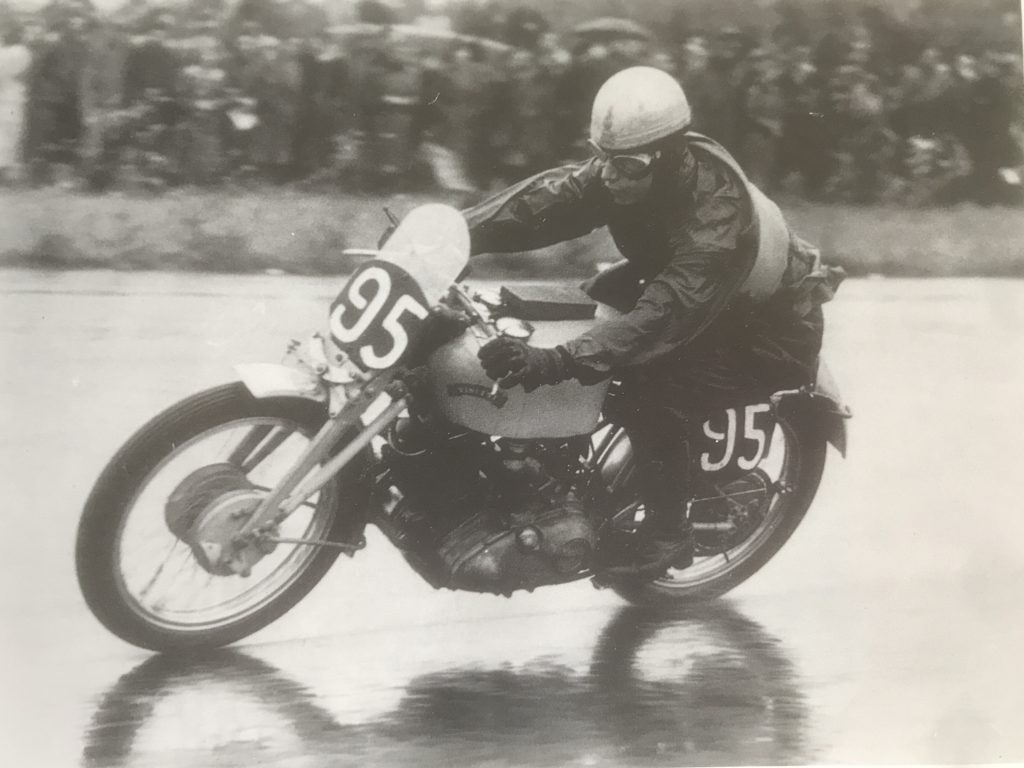

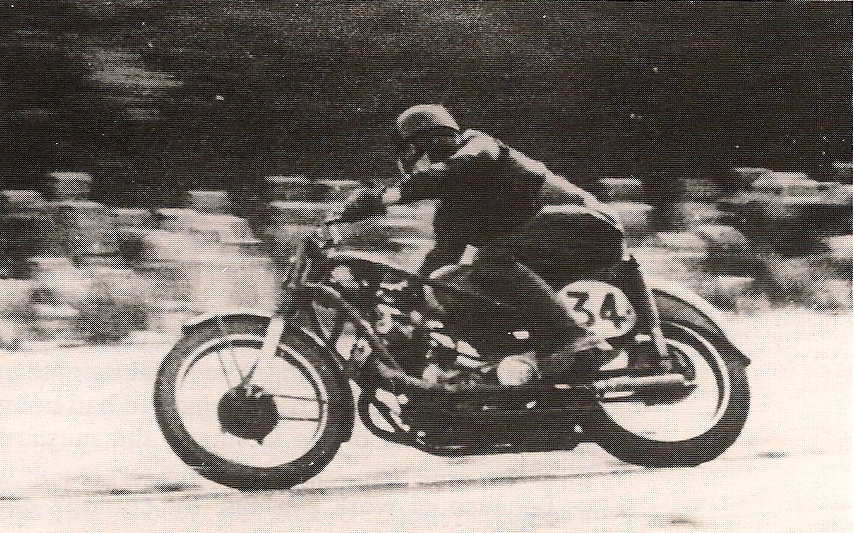

Further testing took place at Montlhery, with four riders (Artie Bell, Geoff Duke, Harold Daniell, and Johnny Lockett) going flat-out for two days. "We went through two engines, then the snow came on. The frame hadn't broken so we all went home." The debut of the new frame came at Blandford Camp, Dorset, in April 1950, with Geoff Duke aboard (below, winning that race). The string of successes which followed gave a new lease on life to a 20-year-old engine design, and Norton won 1-2-3 in the Senior and Junior TT's that year. Norton didn't have the facility to produce the Featherbed frame themselves, nor could Reynolds (the tubing manufacturer), so Rex brought his own jigs over from Ireland, and personally built the Works Norton frames from 1950-53. The original jigs still exist - what a historic piece of scrap iron!

Cannonballs Deep: In The Thick Of It

After the debacle of Day 1, a reckoning was made by quite a few riders. If their machine had failed so utterly, or burned to a crisp, was there a point in carrying on? Normal humans have jobs and responsibilities, and blocking out 3 weeks of motorcycle time requires considerable planning. If your motorcycle went bust, is the remainder of the event a ride of shame, a holiday spent watching your friends achieve glory, or an opportunity for an unexpected holiday? Folks took each path, some trucking their broken bikes home, spending a week on a different vacation, and returning to meet us at the finish. Some simply disappeared. A few were already part of a team, and carried on as support for those still rolling.

| Don't try this at home! John Pfeifer's 1916 Harley-Davidson, with the leaky fuel tank. Could he fix it as a patina ride? No. |

There's also the expense: in addition to 3 weeks of hotels etc, the Cannonball has skewed prices for pre-1917 motorcycles, in total contrast to the automotive market. A year ago, when this 'century ride' was announced, it was intended to be both a motorcycle AND automotive event, with a staggered start for the cars, the bikes following a day behind, and a shared day off in Dodge City, Kansas. With almost no publicity, there were a dozen entries for the automotive class within a week, and both Lonnie Isam Jr and Jason Sims, the Cannonball organizers, purchased c.1916 Dodge sedans in excellent condition, each costing roughly $15,000. For even the humblest of Cannonball motorcycle entries (say, the 1914 Shaw motor bicycle), you'd double that price, and for most, you'd need an extra zero. That's because there are plenty of old American cars sitting idle, and zero demand for them. There's hardly any events in which to use them. In the end, it was decided the Cannonball would remain all-bike. And the auction companies had a field day: Mecum auctions is now a major sponsor of the Cannonball, and Jason Sims mentioned they were pressing him to reveal the cutoff year for the 2018 Cannonball, so they could cultivate a new herd of eligible bikes for the big Las Vegas auctions.

|

| The road as big as the sky |

Day 2, September 11th, was my 54th birthday; it was my 3rd birthday on the road with the Cannonball, and the best so far. York PA is not far from Gettysburg National Military Park, and I'd never been to a Civil War battlefield. The town is charming, and when we discovered the best donut in the world (Treat Yo' Self), we asked which direction was the battlefield, to be told 'you're in it.' True enough, war is messy, to be cleaned up later by historians and those with an agenda. We were lucky to encounter a group of gents whose hobby was period correct camping, comprising a regiment of blue-coated regulars in a field with their tents - the 53rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. They were delighted to work with us, posing for wet plate photographs - they'd done so previously, but never on the scale Susan and I attempted. The resulting wet plate images are real time-benders, in the very spot which stuck the wet plate photograph in the world's consciousness, via the work of Matthew Brady, who posed his corpses and cannonballs as keenly as we did our living subjects.

|

| Posing our regiment in Gettysburg. Thanks boys! |

My birthday dinner was our 2nd excellent meal of our 21-day adventure, at Tin 202 in Morgantown, West Virginia. Thus encouraged, we had high hopes for a trail of good meals, but the next 3-star dinner was 2400 miles away.

| I asked for it as a birthday present, but this lovely '46 Indian Chief and sidecar needed to be ridden home that morning... Shiloh, Pennsylvania |

Day 3 on the relentless schedule West found us at lunch in Williamstown, WV, at SandP Harley-Davidson. All but 3 of our scheduled lunches were hosted at Harley dealerships, and our organizers must have sent out a memo for 'no pulled pork', as that was the ubiquitous fare in 2014. Cannonball rules stipulate you MUST stay at a hosted lunch or dinner stop, as the quid pro quo for a meal - the venues advertise a display of our old bikes, and draw healthy crowds. Not so painful, unless you're a vegetarian, or prefer a different sort of lunch experience than foldup plastic tables in a charmless and makeshift storage room at a bike dealer. We're thankful for the food, of course, but I much preferred when the local Elks clubs made us lunch in a city park - that seemed more an act of generosity and goodwill than the commercial opportunity afforded by our presence at a place of business. Your mileage may vary. Susan and I were busy jumping in and out of our wet plate van, taking photos at the lunch stops, and didn't explore the food until the riders had thundered off, and we were starving. 75% of the time we simply turned around to find a local, non-chain diner, which was work in itself. Susan's daily goal was a good grilled cheese sandwich, something not offered by Subway or MickeyD.

| Does a Henderson handle? See for yourself - a looong wheelbase and decently rigid chassis equals a stable ride. Near Clarksville, Ohio |

And then there are the hotels, motels, Holiday Inns. The quality of accommodation was way up over 2012, but the succession of Quality, Hampton, Comfort and Fairfield Inns became a blur. We'd learned from 2012 that excellent coffee sets the tone for our day, so a French press, a few pounds of our favorite grand, and a teakettle are essential for our mood. I pity other addicts who suffered through hotel coffee for 3 weeks. Susan takes hers black (she's tough like that), but I carried cream in our cooler, preferring 'kitty coffee', as a balm for the assaults of the coming day.

|

| Zika eradication squad! Architect Ryan Allen smokes away on his 1916 Indian Powerplus in Williamstown, West Virginia |

Which came mostly in the form of rain; after the muggy heat of our first 1200 miles, relief came in torrents from the sky, and we were pissed upon suddenly and relentlessly. The timing was treacherous, as in a twisted bit of humor, we undertook a series of unmarked rural roads to cross the 'Cannonball Bridge' near Vincennes, Indiana. Its construction was unique in my experience, being a converted railway bridge with the usual gapped sleepers, with a pair of tire paths made from lengthwise boards of various thickness, laid down like a threat before the riders. It felt pretty damn wonky in my truck, but was hellishly slippery for the riders crossing in a downpour. Cannonball bridge indeed.

| A foggy morning in Dodge City. We all ride alone. |

As our caravan of 300 souls and all their support vehicles sped relentlessly Westward, we passed through Chillicothe Ohio, Bloomington Indiana, Cape Girardeau and Springfield Missouri, and Wichita Kansas. Just outside Wichita, in the suburb of Augusta, fellow Cannonballer Kelly Modlin has recently opened the Twisted Oz Motorcycle Museum, with a terrific display of restored and original-paint motorcycles, most of which could have been on one or more Cannonballs. It's a terrific display, and Kelly's family put on a welcome meal under the framework of the museum's next expansion, which will double its size already, within a year of its opening. We all got too many bikes, and not enough willing asses for their saddles!

|

| Rick Salisbury on his 1915 Excelsior |

Saturday September 17th we arrived in Dodge City, Kansas, grateful for our day off on Sunday, where riders could wash clothes and catch up on maintenance and rest. For Susan and I, that meant double the work, as riders were available all day for portrait sessions, and we set to, taking a record 24 tintypes on Sunday in a variety of spots, including at the site of old Dodge City board track, where H-D Museum archivist Bill Rodencal was determined to get a tintype of his machine. His 1915 Harley-Davidson racer had won Dodge City a century before, and he wore period gear to be immortalized on the very spot, which we were honored to do. The photos came out great, including one Bill caught of us!

| Thanks Bill Rodencal for working the lens cap of our 4x5" camera! Bill's 1915 Harley-Davidson racer... |

| ...which he rode over 2300 miles. The bike has NO suspension at all, an uncompromising riding position, and a single speed! 'America is my Board Track' |

|

| Michael Norwood and his 1916 Harley-Davidson at the big train on Boot Hill, Dodge City, KS |

| The solitary Reading-Standard to attempt the Cannonball, a single-cylinder belt drive model, with Norm Nelson piloting. 1744 miles covered. |

| Niimi! On his shared Team 80 1915 Indian, with Shinya Kimura. Caught in the rain in Ohio. |

|

| Kelly Modlin with his grandson at his Twisted Oz Museum in Augusta, Kansas |

|

| Team 80 takes a gander at the Hillclimber selection at Twisted Oz |

|

| Dawn and Doc, and the 1916 Harley-Davidson with wicker sidecar with which they covered every single mile of the Cannonball - a truly impressive achievement. |

|

| A one-block town with one brick building, and a nice red frame for the 1916 Indian Powerplus of Kevin Naser. Neodesha, Kansas...pronounced 'Nay oh du Shay', we were instructed |

| Storm's a brewin in Kansas... |

| Kevin Naser stopped in Grant, Missouri, for a change of gear. |

|

| Brent Hansen and his 1914 Shaw, popping along the plains of America's vast middle |

|

| Quonset huts are rare today, but tailor made for a retro cafe, as in Springfield Missouri |

|

| What becomes Europe's largest Harley-Davidson dealer best? Americana ink. |

|

| Miss Route 66, Sara Vega, poses with Alex Trepanier and his 1912 Indian single. Alex covered nearly every mile of the United States, an epic achievement. |

|

| The future rolls out before you on the Missouri/Kansas border |

| The Powerplus team of the Rinker family, father Steve (here) and twin sons Justin and Jared |

|

| Missouri |

|

| A small-town radio station in Cabool, Missouri |

|

| The heartland is full of great motorcycles; this is Powderkeg Harley-Davidson in Mason, Ohio |

| Powderkeg H-D was named for a nearby gunpowder factory, now being converted to condos. Swords to plowshares? |

|

| South African Hans Coertse, on the only Matchless to compete in the Cannonball to date, a robust 1914 t-twin |

|

| With so many Centurions on the road, it was easy to overlook the everyday cool bikes which tagged along, including this neat BMW R60/2 that also crossed the country |

| As Team 80 is unlikely to attempt a 5th Cannonball in 2018, I regret not witnessing the nighttime poetry of their plein-air workshop, conducted in silence, with hand-held lights. |

Cannonballs Deep: The Beginning

It was history to be made, and 94 riders grasped the gauntlet; to be the first 100-year old vehicles of any sort to cross the United States. Cars, planes, bicycles, rollers skates, whatever - the 2016 Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Rally, this year called the Race of the Century, would the be the first attempt to my knowledge for any Centurion vehicle to cross the country.

That claim was staked at the starter's banquet in the Golden Nugget hotel on September 9th in Atlantic City, New Jersey, during an oppressively hot and muggy late Summer week - 95 degrees and 90% humidity - the hotel having chiseled off it's 'Trump' name some years ago during a bankruptcy proceeding.

The Motorcycle Cannonball was initiated by Lonnie Isam Jr, as both an homage to the achievement of Erwin 'Cannonball' Baker's cross-country record breaking sprees in the early part of the 20th Century, and a challenge to the many owners of early motorcycles who didn't ride them all that much. Lonnie believed early machines were just as capable of crossing the country today - on paved roads rather than dirt tracks - as they were when new, and the first Cannonball was held in 2010, with a small cadre of riders on pre-1916 machines accepting the challenge. That first year was notoriously difficult, and an admirably bonding experience.

Nobody had tried such an incredibly long ride - 3500 miles - on such old machinery, and nobody really knew what to expect, or how the bikes would hold up to riding and average 250 miles/day on a rigorous schedule.It wasn't the only evidence of Trump, or bankruptcy, we'd encounter on our third trip over backroads America. Three Cannonballs, this one likely to be my last, and for once totally bikeless, as my partner (with the bike) couldn't take the 3 weeks off this year. My artistic and life partner Susan, after a crisis huddle, decided our MotoTintype project was too important to abandon, so we chose to follow the Cannonball as photographers, taking as many 'wet plate' photos as we could, and round out the hundreds of images we'd already shot on the prior 2 events, in order to make a book of the best images. Susan's brother Scott drove my Sprinter to NYC, and thus began another epic road trip.

Not surprisingly, the tales of woe and late nights spent making repairs, every single night, made that 2010 event legendary. Most of the original 45 riders vowed never to do it again, and kept their promise! Some returned in 2012 though, especially as the rules were relaxed to include bikes up to 1930. That allowed me to naively enter the 2012 Cannonball with my 1928-framed Velocette Mk4 KTT. 'The Mule' had been my reliable rally machine for 12 years, taking in 7 week-long Velocette rallies, covering 250-mile days with aplomb. I'd already effectively double the Cannonball mileage on a similar daily schedule, so it seemed a plausible effort.

With no motorbike to concern us this year, Susan and I had an all-Sprinter Cannonball rally, and embraced the experience. Following the same route as the riders, we were blessed with the endlessly beautiful and fascinating landscape of the United States. The natural beauty of the East Coast forests, with their winding hills and hollows, lovely climbs were perfect motorcycle roads, dotted regularly with podunk villages and oddball eateries, brought a mix of awe at Nature and concern at Nurture. Signs supporting a blustering demagogue were inevitably mixed with Confederate flags in Pennsylvania, a clear repudiation of both the policies and race of our current president, in parts of the country left far behind the technology-based prosperity of my native California.

September 10th was a short ride of 158 miles through an endless series of New Jersey stoplights. The heat, and the constant stop-start, took a heavy toll on machinery and riders, and by the end of the day in York, Pennsylvania, 23 machines were hors de combat. Some refused to start in the heat, some broke parts, some seized, and one burned to the ground. John Pfeifer had built an extra-capacity fuel tank for his 1916 Harley-Davidson, and the weight of a full tank pressed down onto the rear cylinder's rocker arm (atop the cylinder head on an F-head motor). It only took 80 miles or so for the rocker to wear through the metal, fuel to spill onto the magneto, and a great ball of flame to erupt. John watched his machine burn for 20 minutes before a fire truck arrived with a decent extinguisher. The first day was the worst day overall, culling the field quickly, and serving notice this wasn't going to be an easy run.

On a bright note, Susan and I had a terrific meal at the Left Bank in York, the first of 3 excellent meals on our 17-day trip. We tried our hardest to eat well, searching daily for the 'best restaurant in X', and finding lists online which invariably included chains like Jack in the Box. It's not difficult to draw conclusions about rural American culinary habits from this, and you'd be correct - America grows food for the world, but eats poorly in the very regions that food is grown. But we'd discovered that a couple of times already, and brought a sufficient stock of coffee and wine from home!

Readers of my2012 Cannonball reports on TheVintagent.com know I had terrible problems with two replacement camshafts I installed, the first lasting about 20 miles total, and the second, installed after many hours modification at a machine shop, lasted only a further 1000 miles. Those were blissful miles over the Rockies, I'll confess, but the truth was, the Cannonball defeated my preparation. The Mule remains the only overhead-camshaft motorcycle to run the Cannonball, and several H-D riders suggested that a machine which couldn't be fixed with a hammer had no place on a run like the Cannonball. Perhaps they're correct.

Cris Sommer Simmons has ridden 'Effie', her 1915 Harley-Davidson, on 2 Cannonballs now, and it acquitted itself very well.

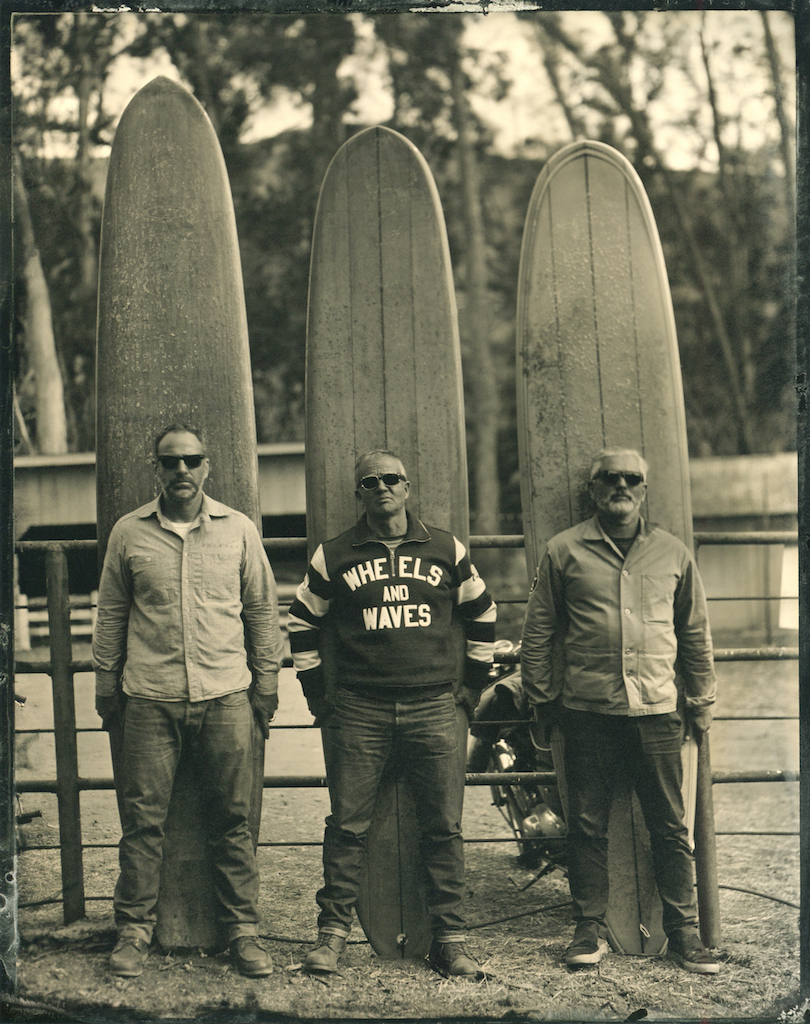

Wheels & Waves Cayucos

[A co-production of the Southsiders MC and TheVintagent.com]

The Southsiders MC have been organizing rides in Biarritz/the Pyrenees/Spain since 2009, when we made up a baker's dozen for a few days riding on vintage machines. I'd met Vincent Prat at the Legend of the Motorcycle Concours in Half Moon Bay in 2008, and he'd invited me to come ride with his friends in France. With exceptional riding roads, little traffic, and terrific Basque food, our merry band of vintagents had found a perfect combination of company and environment.

The event was repeated the next year, and the next, growing with each iteration; by 2011, the Southsiders added a party in Toulouse to the ride, with an art exhibit and music, which was the prototype for Wheels&Waves, which began in June 2012 in Biarritz. That little ride with a dozen of us is now an event with 15,000 attendees, still with the ride in the mountains, and other fun in the region, like the Punk's Peak hillclimb/sprint, and now a flattrack race in Spain, along with the ArtRide exhibit, and music at the central 'village' at the Cité de l'Ocean in Biarritz. It's a terrific mix of moto-centric fun, and a unique mix of the vintage, custom, chopper, surf, race, and skate scenes.

What does this have to do with The Vintagent? It's a strategy: one-make vintage motorcycle clubs, and groups like the VMCC and AMCA, have an aging membership, and their members/boards lament and fret on how to interest younger riders in old machines. Younger riders are in fact already interested in old machines - alt.custom sites like Pipeburn and BikeExif feature plenty - but aren't interested in hanging around a boring bike club. A mix of old an new machines is happening organically at events like the BikeShed and Wheels&Waves; what better place to fan the interest of younger riders than to bring old bikes, and ride them in the mix at cool events?

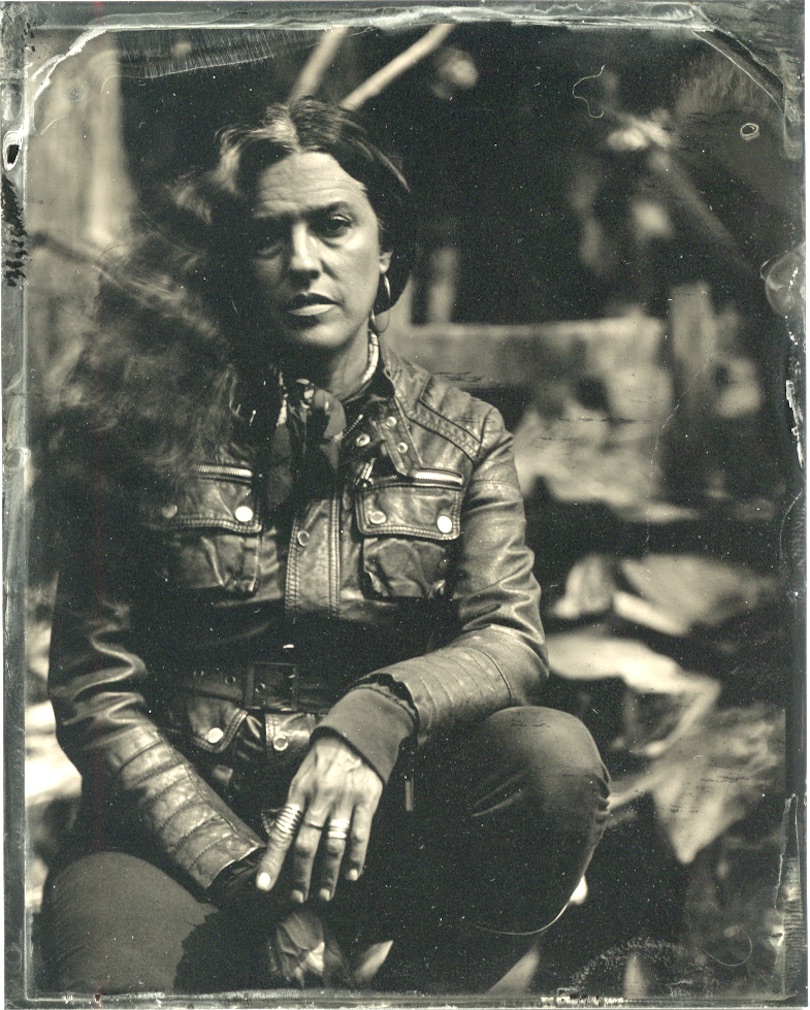

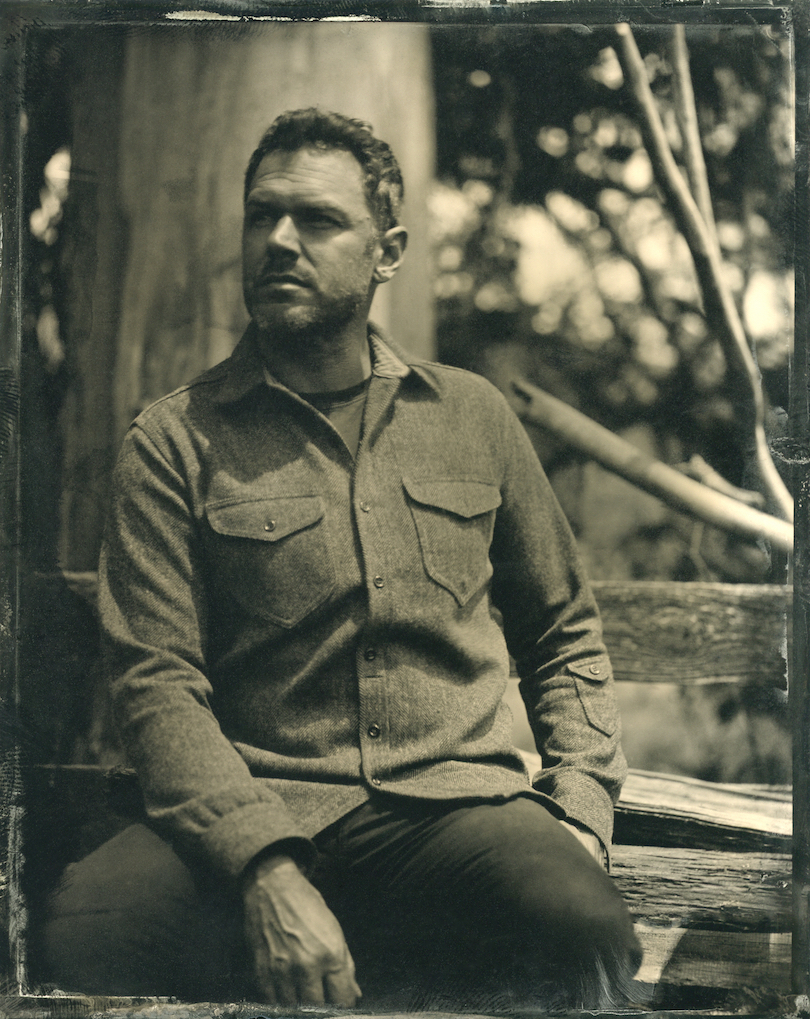

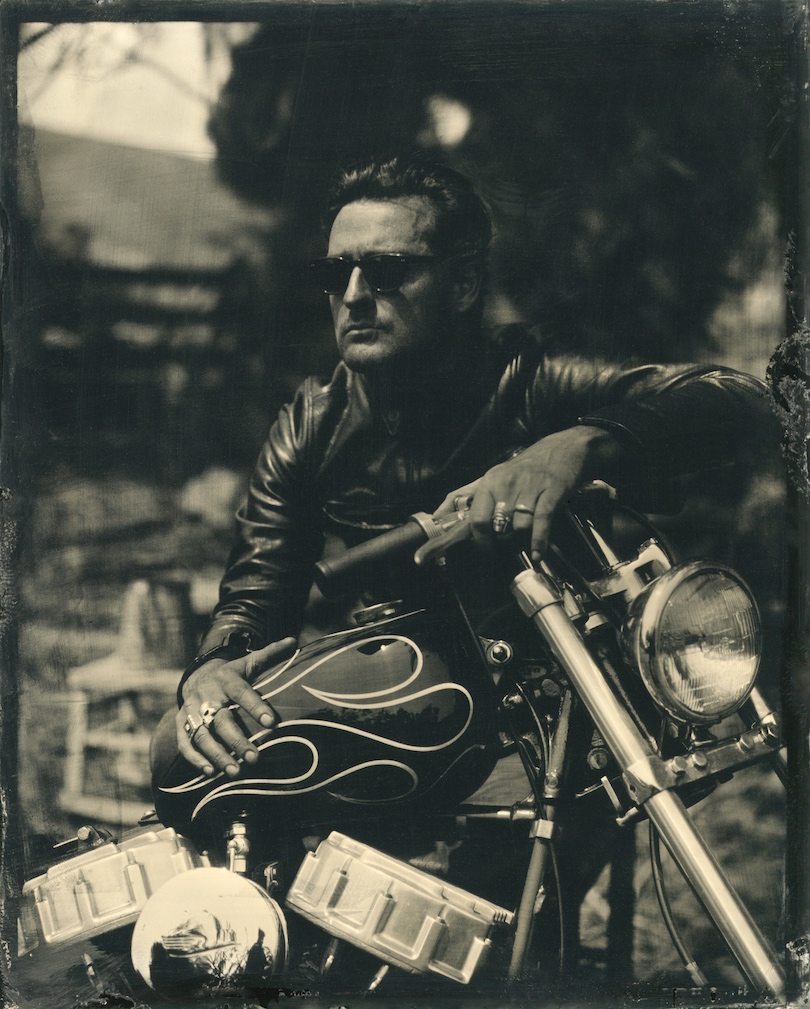

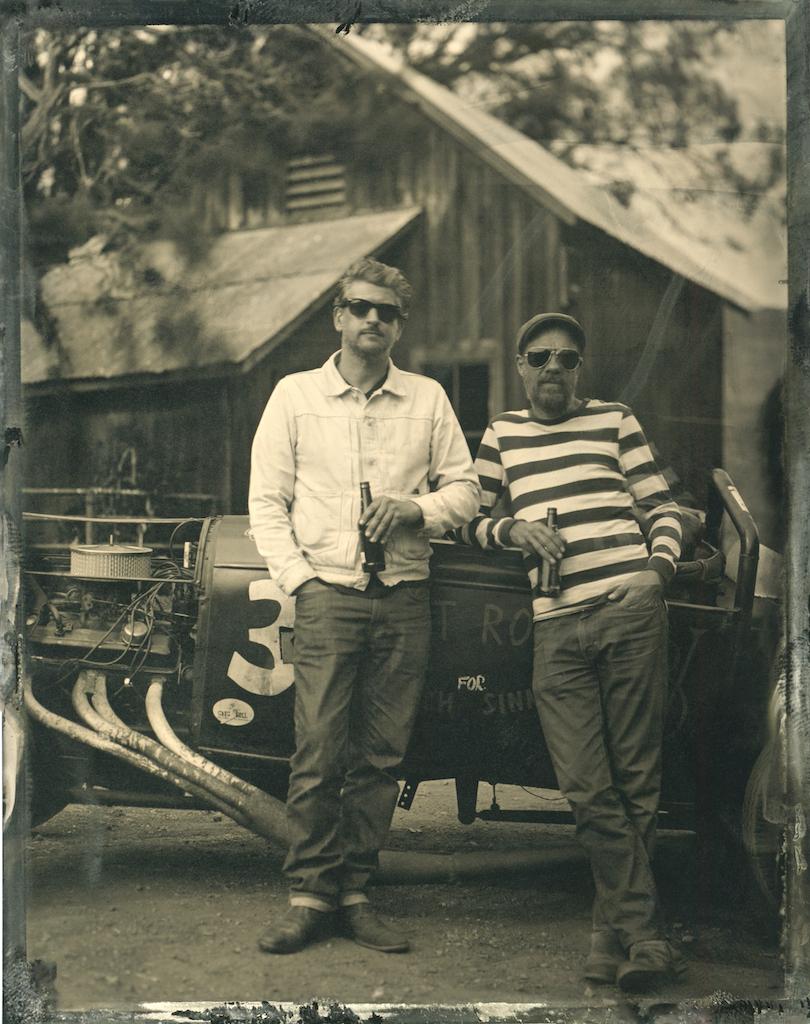

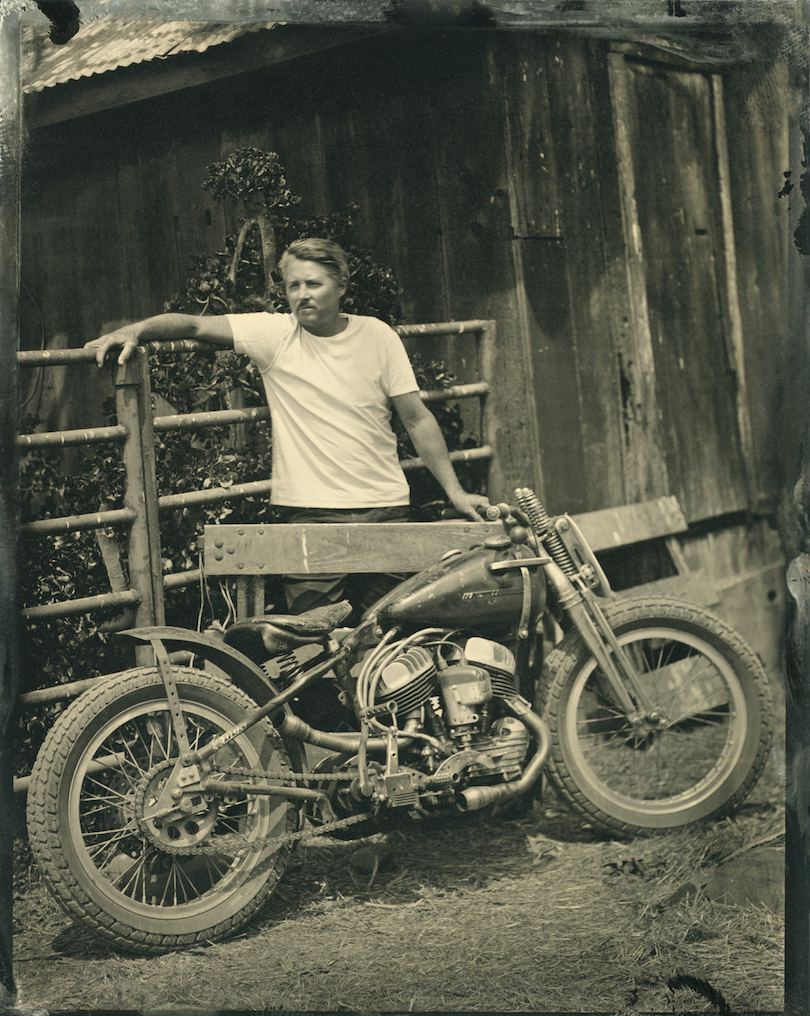

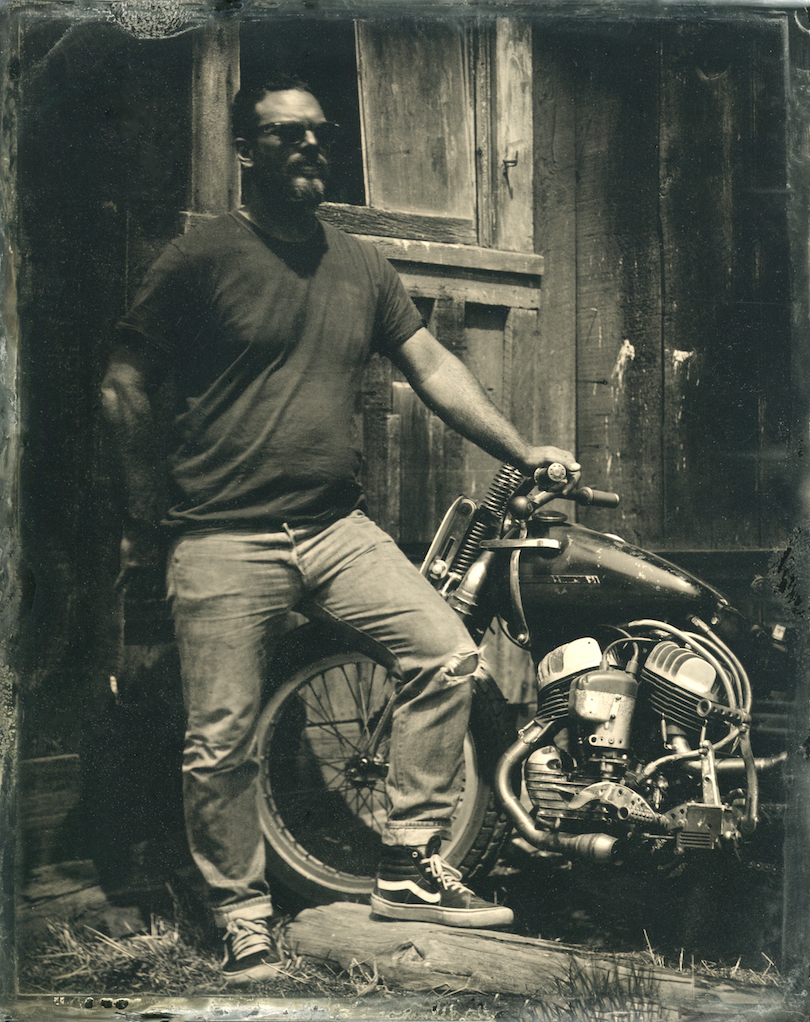

To support this concept, TheVintagent partnered with the Southsiders MC last month to host Wheels&Waves Cayucos, a low-key flag-planting on American soil of a great event. A few friends were invited to the Swallow Creek Ranch for 2 days of riding through the Central Coast hills, and an opportunity to hang out without distraction. Our mascot for the event was Richard Vincent, who raced Velocettes and Triumphs in Santa Barbara in the early 1960s, and surfed in the area too. Richard brought his vintage surfboards, Velocette dirt racers, and a bunch of photographs from his racing/surfing days. Susan and I shot MotoTintypes with our Wet Plate Van, and portraits of a few friends, which I'm sharing here, along with a few of my iPhone shots. Stay tuned for next year's event!

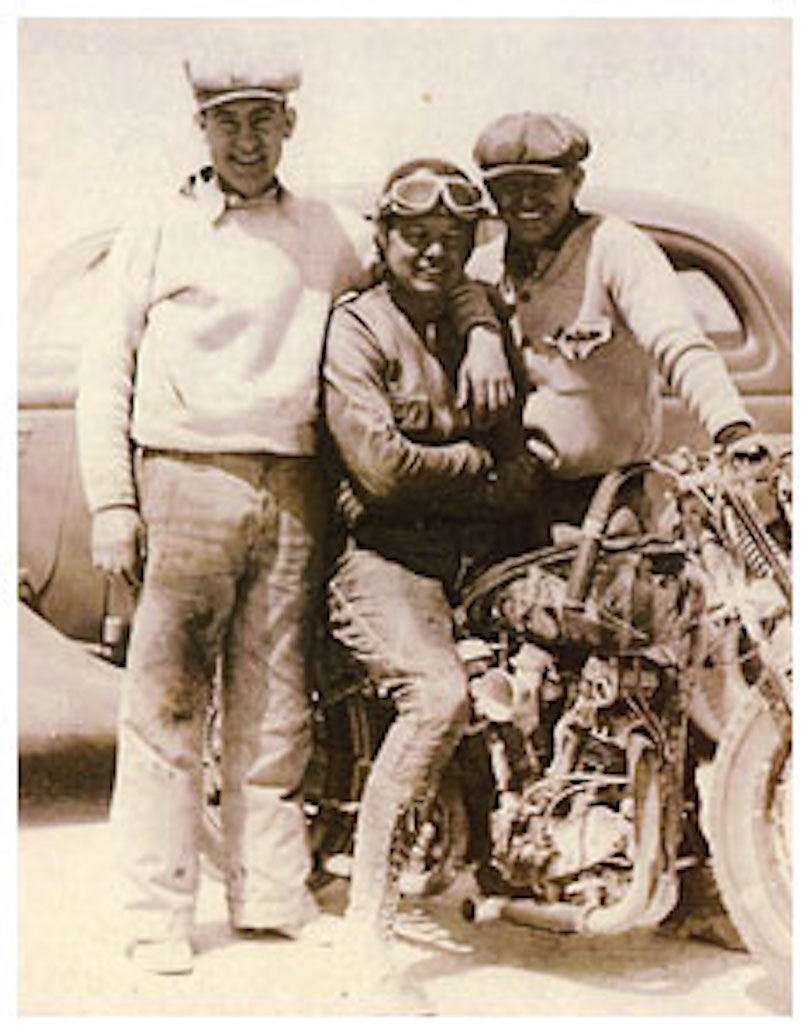

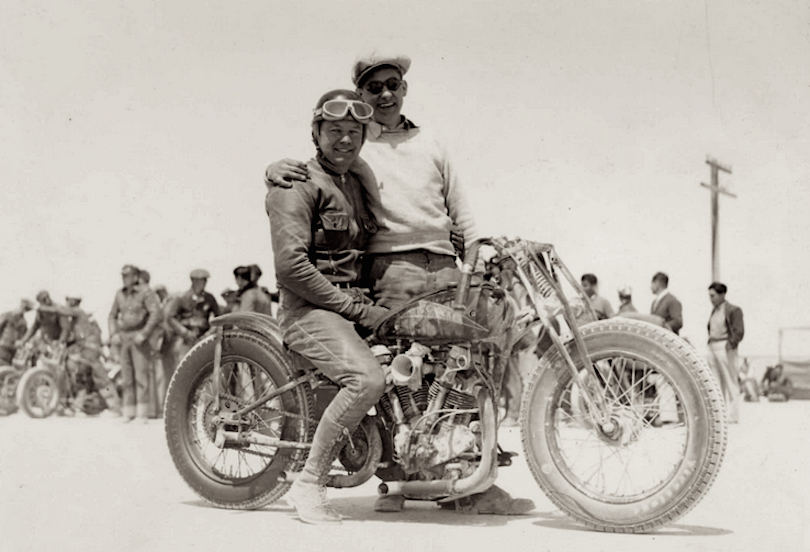

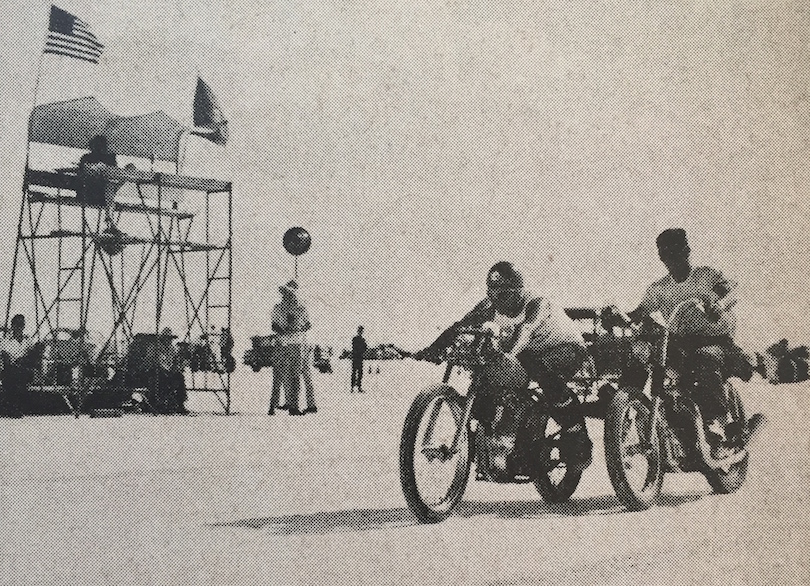

The Old School at Bonneville

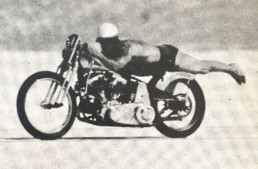

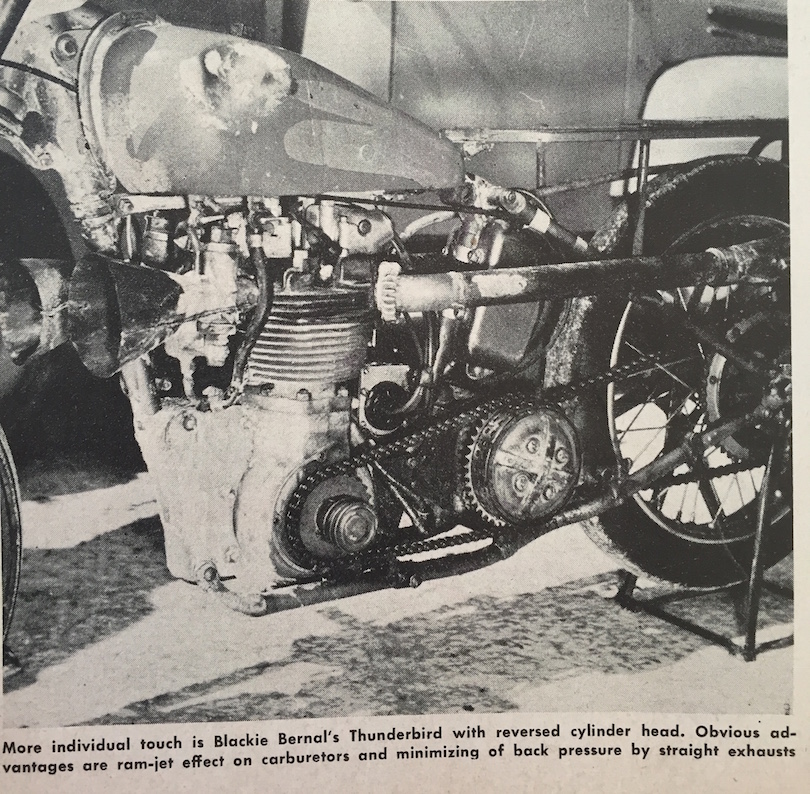

Digging through the bins at my local flea market, I unearthed a gem; a 1952 copy of Cycle magazine. The cover photo was tremendous; Blackie Bernal's Triumph Thunderbird record-breaker, ready to be foot-shoved off the starting line at the Bonneville Salt Flats. The pusher's foot sneaks into the photo, but most dramatically, Blackie is wearing nothing that might be called safety equipment, barring a 1930s era 'pudding basin' helmet. As Rollie Free proved in his 1950 Vincent 150mph 'bathing suit' speed record, less clothing means less drag, and no doubt less heat under the Utah sun. While the Salt Flats sit at 4200', and temperatures are rarely above 90degrees, the blinding white salt and utter lack of shade on the dry lake bed can be punishing.

Blackie Bernal is best known for his use of a 'reverse head' on his Triumph, with the carburetors facing forwards, presumably in the interest of free 'supercharging' of the incoming fuel/air mix. To this end, he fitted huge metal funnels to his carbs to focus the incoming wind, which presumably included a measure of salt spray as well! He ran and re-ran the black-line course for a full 8 days to reach his goal. While the engineering philosophy behind his work is questionable, there's no doubt his machine was very fast; he averaged 144.338mph over two runs, giving him the 40 cubic" Class A American speed record.

That speed was purchased at the expense of a considerable swath of skin from Bernal's rider, Tommy Smith of Turlock, CA. He'd come off at over 140mph, and according to Cycle, "had a spellbinding spill. When he had finally stopped grinding bodily across the salt, Tommy arose and waved to the crowd that he was all right, before sinking back to the ground." Racing on the salt was then suspended for 4 hours, while the ambulance was away with Smith, who required several skin grafts. One shudders to think of a near-naked bodysurf across the surprisingly rough surface of the salt flats - rubbing salt into the wound indeed!

The fastest time of the meet in 1952 according to the organizers the Southern California Timing Association (then only 3 years old!) was 168mph, achieved by the 80 cubic" Harley-Davidson Knucklehead of CB Clausen and Bud Hood. The Knuck had no fairing and no supercharger, but probably ran special fuel - a respectable speed in any era!

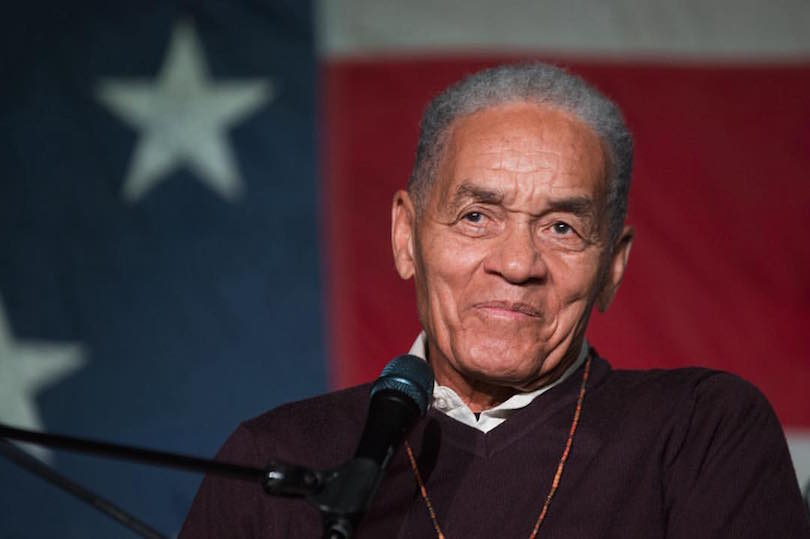

Cliff Vaughs – Rest Easy

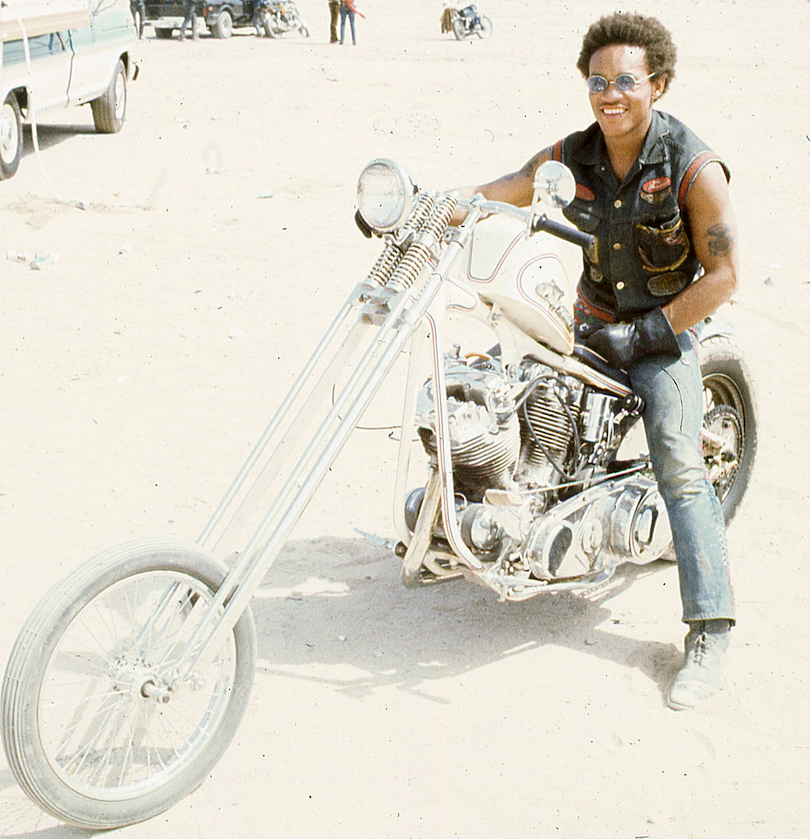

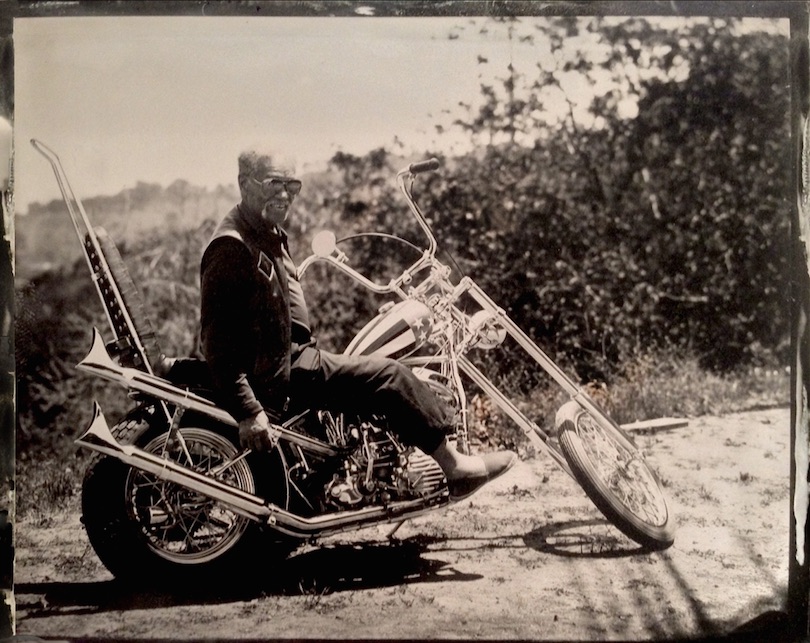

Cliff Vaughs, best known for his creation of the ‘Easy Rider’ choppers, sailed away from this world quietly on July 2nd from his home in Templeton, CA. Had it not been for Jesse James’ ‘History of the Chopper’ TV series, Vaughs would have likely vanished from history, but the question ‘who built the most famous motorcycles in the world?’ needed an answer. That led Jesse to a sailboat in Panama, where he found Cliff, who’d left the USA in 1974. Why he lived alone on a sailboat in the Caribbean, instead of soaking up praise for his work on ‘Easy Rider’, and his filmmaking , photography, and civil rights work, is a long story. I told some of that story in my book ‘The Chopper; the Real Story’, but Cliff’s life was too big to fit into one chapter of a book, and he dismissed 'Easy Rider' as "Three weeks of my life".

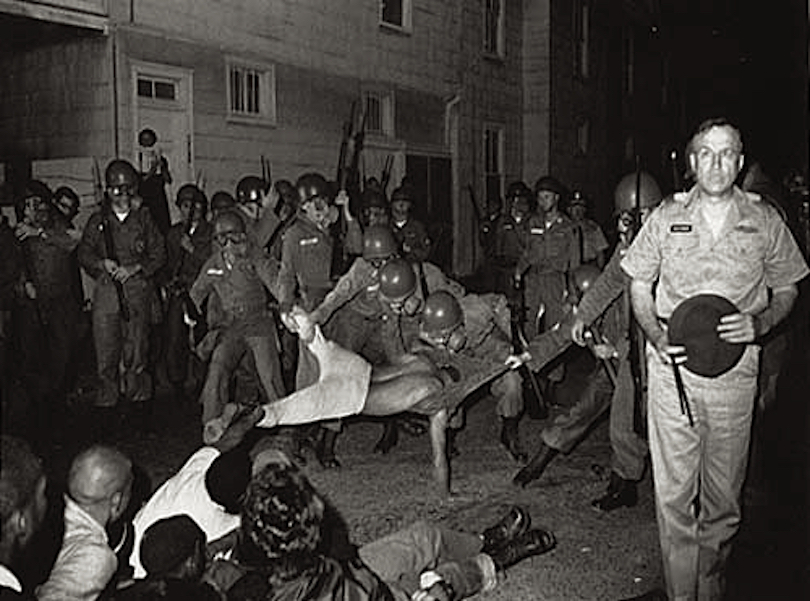

Cliff Vaughs was born in Boston on April 16th, 1937, to a single mother, and showed great promise as a student. He graduated from Boston Latin School and Boston University, then earned his MA at the University of Mexico in Mexico City – driving from Boston in his Triumph TR2. Moving to LA in 1961, he encountered the budding chopper scene, and soon had a green Knucklehead ‘chopped Hog’, as he called it; that’s where he befriended motorcycle customizer Ben Hardy in Watts, who became his mentor. Cliff was recruited to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1963, and brought his chopper to Arkansas and Alabama, where he drag-raced white policemen, and visited sharecropper farms “looking like slavery had never ended.” He added, “I may have been naïve thinking I could be an example to the black folks who were living in the South, but that’s why I rode my chopper in Alabama. I was never sure if the white landowners would chase me off with a shotgun. But I wanted to be a visible example to them; a free black man on my motorcycle.”

Cliff’s chopper adventures in the SNCC was a story never told – he was too radical, too provocative, too free for the group. Casey Hayden (activist/politician Tom Hayden’s first wife) remembered Cliff as “a West Coast motorcyclist, a lot of leather and no shirts. Hip before anyone else was hip. A little scary, and reckless.” Cliff’s ex-wife Wendy Vance added “He was a true adventurer. ... There was just some sort of fearlessness in all situations. It did not occur to him that he was a moving target on this motorcycle. At a march in Selma, the civil rights leader John Lewis refused to stand next to him. ‘You are crazy,’ Lewis said, ‘I will not march next to you.’ The fear was that, somehow, Cliff would make himself a target.”

Cliff was indeed a target of many failed shootings, and his tales of riding his chopper in the South were incorporated into ‘Easy Rider', after he returned to LA in 1965 to make films like 'What Will the Harvest Be?', which explored the nascent Black Power movement. Cliff was Associate Producer on 'Easy Rider', and oversaw the creation of the Captain America and Billy choppers, which became the most famous motorcycles in the world. He didn’t get the recognition he deserved for those bikes, partly because the whole crew was fired when Columbia Pictures took over production, and Cliff’s payout/signoff included a clause keeping him off the film’s credits. Publications like Ed Roth’s ‘Choppers Magazine’ explored Cliff’s role in ‘Easy Rider’ from 1968 onwards, but both Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper at various times claimed credit for building those bikes, and Dan Haggerty took credit too. Hopper acknowledged in his last year the seminal role Cliff Vaughs played, as did Peter Fonda, in 2015. Cliff went on to produce ‘Not So Easy’, a motorcycle safety film, in 1974, but left the US to live on a sailboat in the Caribbean the next 40 years. He was brought back to the US in 2014, as appreciation spread for his contribution to motorcycle history, and he was celebrated at the Motorcycle Film Festival in Brooklyn last year; a documentary from his time in NYC is being edited as this moment. Godspeed, Cliff.

- For my first discovery of the lost black history of 'Easy Rider', click here.

- For Cliff's story on his role in 'Easy Rider', click here.

- For Peter Fonda's acknowledgement of Cliff's role in 'Easy Rider', click here.

- For the NPR story on Captain America, click here.

- For copies of 'The Chopper; the Real Story', click here.

Gearhead Valhalla

[Text/photos by Paul d'Orléans. Originally published in The Automobile - the best old-car mag on the planet]

Lake Como’s leafy sentinel towers over the Villa d’Este’s grand gravel terrace, but the hoary Sycamore is chopped further back every year, its once expansive canopy shrinking to a leafy fat spire, providing shade no longer, yet still the axis of the party. The villa’s Renaissance gardens and pebbled grottoes are intact these 500 years; swapping an elderly companion for younger model may be the habit of the Concorso’s wealthy entrants, but the tide of History demands respect for the old tree, as it does for the automobiles and motorcycles celebrated within the grounds.

Anxiety over the Sycamore’s fate defines the beginning and the end of troubles at the Concorso d’Eleganza di Villa d’Este; as lucky guests and journalists float on the music of clinking glass flutes, the poor tree plays Cassandra for the real world’s troubles - vanishingly absent from the scene otherwise. Burbling Rivas deliver the happily elegant to the hotel’s shores, not the desperate, so we may rightfully celebrate the fabulous treasures of our world on the weekend, and return to reality on Monday.

For 2016’s iteration of the most coveted spot in the show-car/show-bike calendar, Nature offered a 3-day gap between torrents; tourist-brochure perfect days, suitable for the otherworldly perfection of 50 cars and 40 motorbikes gleaming with elbow-grease, from helper-hands conjuring prize-granting djinns via yellow microfiber cloths. And that, readers, is serious work, conducted by an unsung and invisible army, never thanked from the podium by the Jereboam-armed, ribbon-draped swells who paid their salaries. The Little People, as tactless Oscar winners once at least acknowledged, whose labors transformed the inert cash of connoisseurs into an invitation to this truly incredible party beside Italy’s most beautiful lake. As tax-haven oligarchs stage dramatic, black Amex duels at fine auctions houses, sending car (and now moto) values to the lofty heights inhabited by the finest of arts – the realm of the gods - rolling sculpture has become the last publicly visible evidence of real wealth, as great art disappears into freeport bunkers, and nested shell companies obscure ownership of part-time mansions.

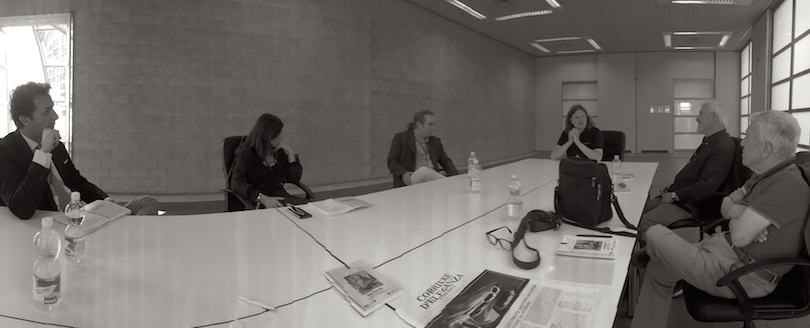

Temporary membership to this sunshiney, sweet-smelling tableau grants one – e.g. me – a few days’ overlap with wildly different Venn circles; it only hurts when the bubble protecting wealth and beauty floats off, and the sweaty tang of real work and deadlines returns. My nominal job at the Concorso di Moto (judging the assembled treasures) is difficult only in the weighing, discussing, and choosing, which can only be counted a pleasure in such company as the since-1949 Motociclismo fixture Carlo Perelli, the director of Prague’s Technical Museum – Arnost Nemeskal, the chief of BMW’s motorrad design - Edgar Heinrich, French moto-institution Francois-Marie Dumas, and, god bless our host country, the editor of Italian Cosmopolitan, Sara Fiandri, who scatters Milan’s pedestrians like leaves aboard her racy Honda.

It must be equally true for our automotive counterparts that Choosing is a profession of thick-skinned devils, as subcurrents of politics, aesthetics, nationality, status, and history swirl around every vehicle, while judges argue – oh yes we do – their views on such matters. We have a day to observe, discuss, ponder, and reassemble before the prizegiving ceremony on Sunday, overseen in the case of motorbikes by the affable and poly-tongued Roberto Rasia dal Polo, while the four-wheeled crowd suffers the inconceivably smooth Simon Kidston, whose puns and light verbal pokes reveal his intimate familiarity with the assembly.

BMW, owner of the Concorso, litters the grounds of Villa d’Este with new Rolls Royces and prototypes, while neighboring Villa Erba, which hosts the Concorso di Moto, is saddled with drudgeries like a ‘Teens BMW monoplane, a terrific display of concept cars/bikes beside the machines which inspired them, and the public, which has free range on the expansive grasslands of the park. This year’s overall theme was ‘Back to the Future’, which translates from German as ‘retro’ – the concept car unveiled at Friday’s swanky cocktail party claimed parentage from the 40 year old BMW 2002 (though it was hard to see resemblance, it was a sharp effort by Adrian van Hooydonk), while the concept motorcycle was an industry first – no factory to my knowledge has ever used a vintage motor as the basis of a show vehicle.

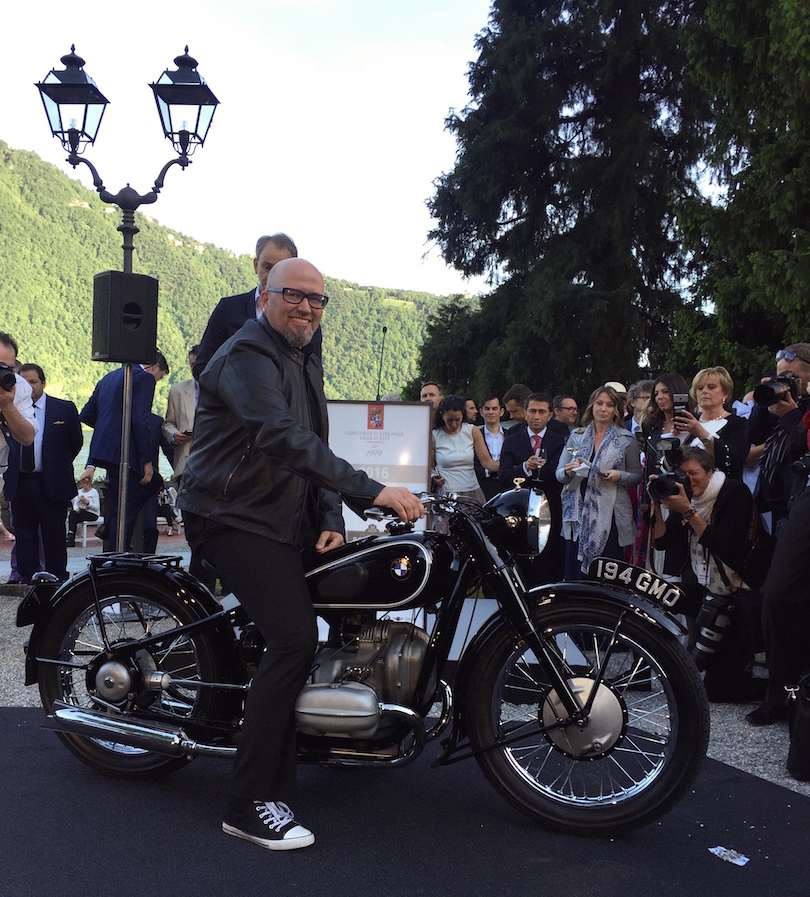

The ‘R5 Hommage’ ridden in noisily by Edgar Heinrich (beside designer Ola Stenegard on an original 1936 R5) used the castings of an 80-year old engine as its heart, although the vintage 500cc OHV motor sported a new supercharger, disc brakes, and a discreet swingarm. While seemingly odd for a technophilic team like BMW to dig around its museum for the actual building blocks of a prototype, ‘heritage’ is the most potent design tool in the moto industry today, and the smooth castings of the old flat-twin motor just might point to an upcoming engine redesign? Back to the future, indeed.

Picking winners in the physical context of Lake Como and a pair of grand Villas seems almost gauche – if you’re there, you’ve won, as has your vehicle. But everyone loves the tension of a contest, and so the list: the under-16 public referendum went rightfully to a 1974 Lancia Stratos rally car, while the drinking-agers chose a bottlefly green ’71 Lamborghini Miura P400SV, which only proves the crowd was Italian, and excitable. The gentry strolling the closed party at Villa d’Este preferred a streamlined ’33 Lancia Astura Serie II, while the judges appointed an exquisite ’54 Maserati A6GCS as Best in Show, a title having much to do, I have learned, with what might look best on the cover of next year’s catalog. This was actually discussed amongst the motorcycle jury, and with vehicles of near-equal money-no-object perfect restorations, what Should tip the scales?

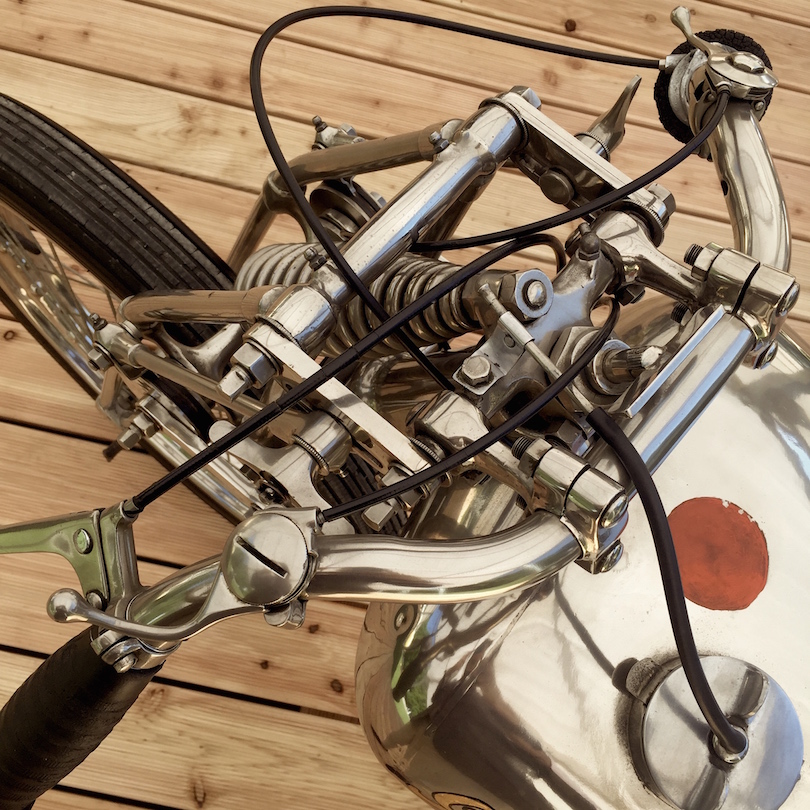

But, we are reminded annually that ours is a Concorso di Moto, not an Eleganza, and thus chose the charismatic and oh-so-English 1929 Grindlay-Peerless-JAP ‘Hundred Model’ with illustrious competition heritage from new, multiple Gold Stars from Brooklands, and a fantastically mechanical, and poster unfriendly, all-nickel finish. What bridged a chasm of disagreement among jurors between suavity and pugnacity was a special Jury Award to the very most elegant ’37 Gnome et Rhone Model X with tailfinned Bernardet sidecar, lovely awash in cream and burgundy, which pretty much describes lunch. Wish you were there.

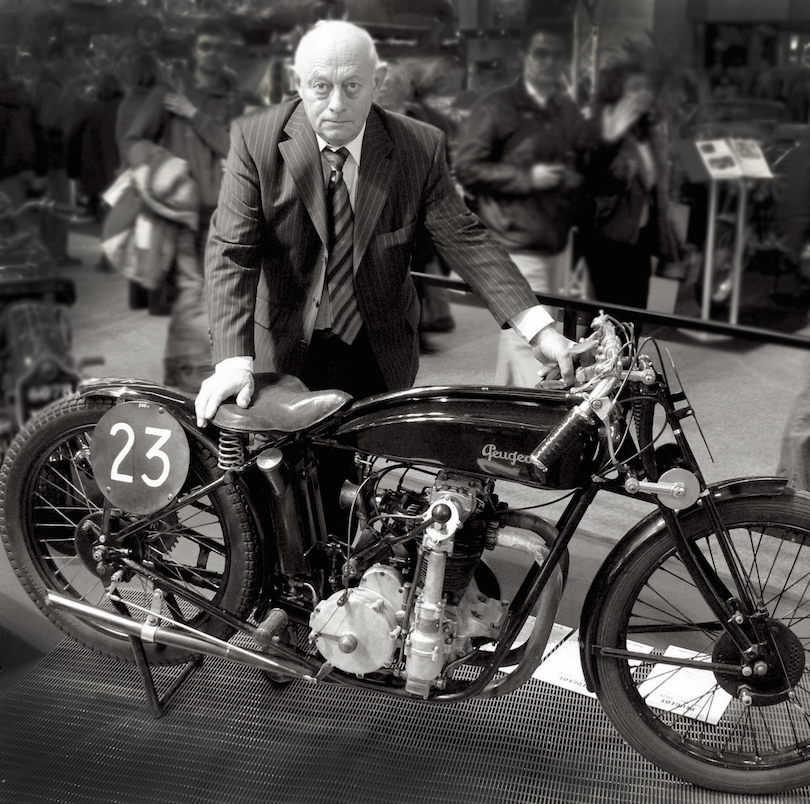

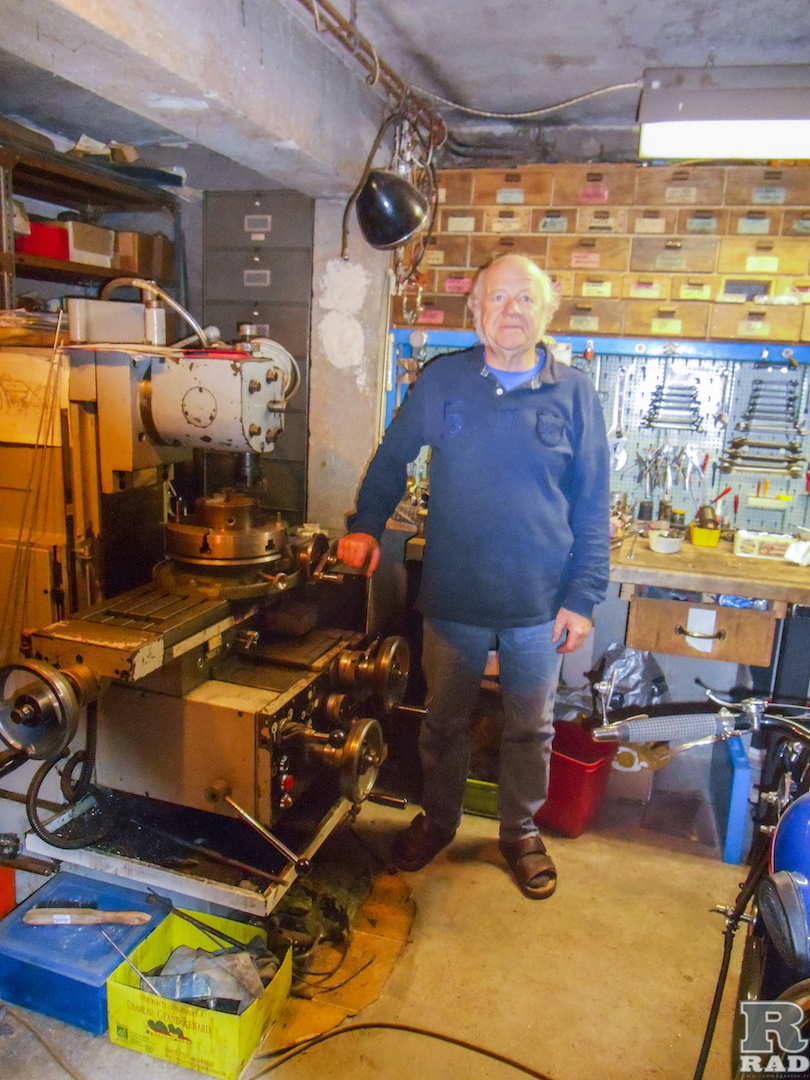

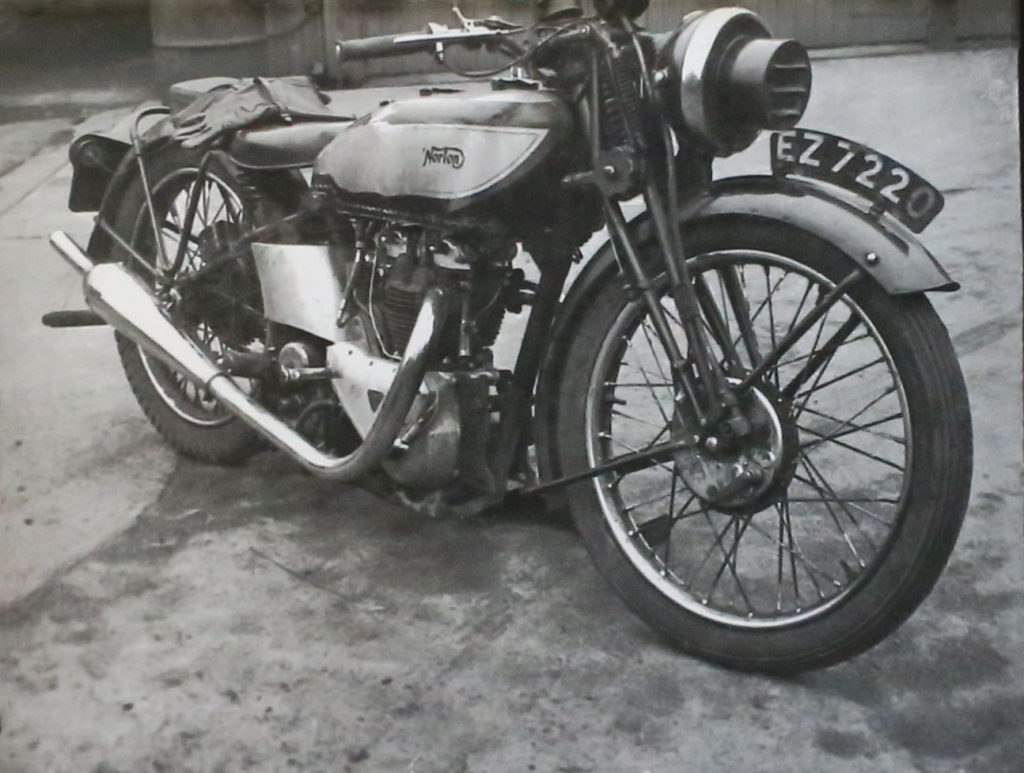

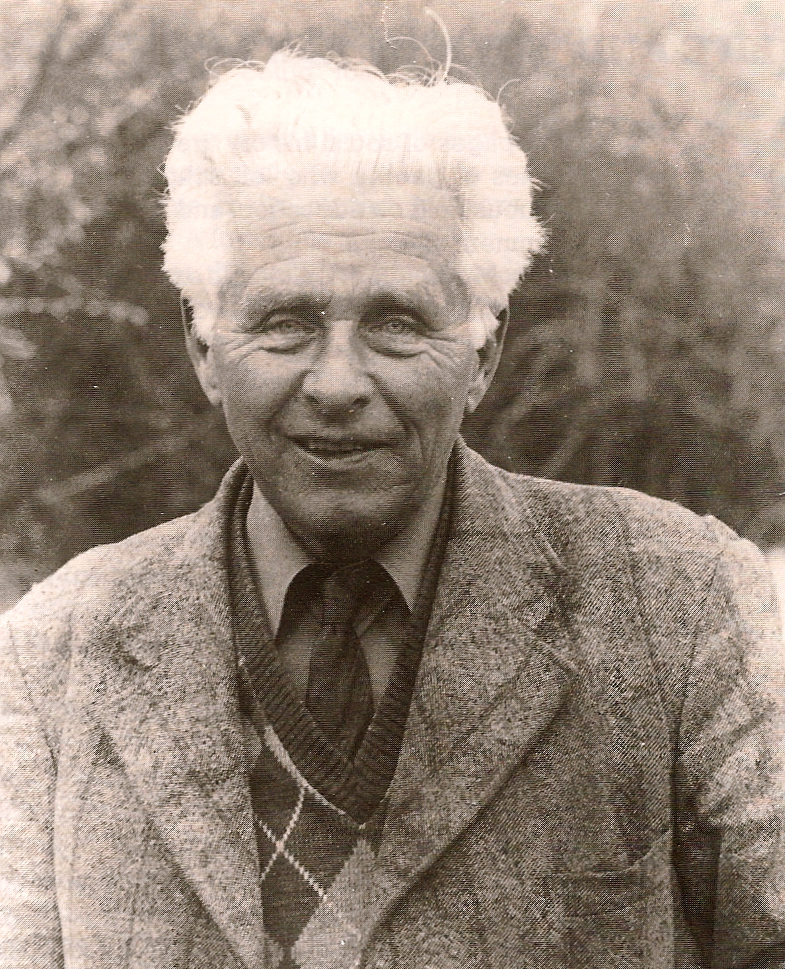

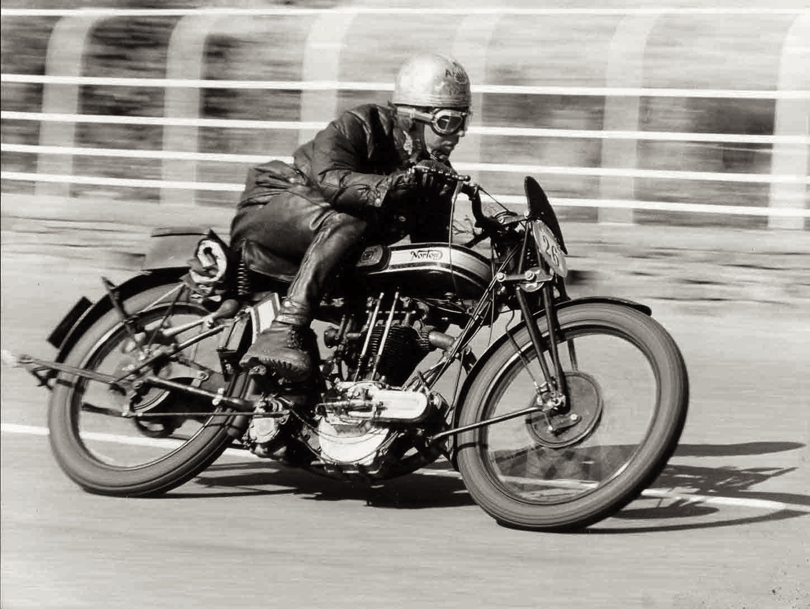

‘Norton’ George Cohen

One of my favorite characters in the old bike scene has left the saddle, and the world is poorer for his absence. Dr. George Cohen, otherwise known as 'Norton George' for his devotion to single-cylinder Nortons (plus a certain Rem Fowler's Peugeot-engined TT racer), fought well against an aggressive cancer diagnosed late last year, but knew the jig was up, that swarf had fouled his mains and blocked the oil lines. What he leaves behind for those lucky enough to have called him friend, is a ton of wry memories, and his distinctive voice echoing through our heads, with some crack about our terrible workshops, ill-prepared machinery, or silly ideas. He was mad as a hatter for sure, but a hell of a lot of fun to be around.

George was also a devotee of using his vintage machinery to the hilt, blasting his favorite 1927 Model 18 Norton racer on the Isle of Man, and the roads around his 'Somerset Shed'. Arriving by train for a visit to George's sprawling country estate was an exercise in bravery, as he'd likely pick you up in his 1926 Norton Model 44 racer with alloy 'zeppelin' sidecar. Strapping your luggage on the back, and no helmet required, meant you experienced the full terror of an ancient, poorly braked but surprisingly quick big single in flight along the ultra-narrow, deeply dug-in Roman roads of the area. The mighty Bonk of the Norton's empty Brooklands 'can' reverberated along the 8' deep earthen walls, as we tore around blind corners of these unique Somerset roads like Mr Toad and Co., headed for home the fastest way possible. Unforgettable!

George visited the USA a few times, and we were fellow judges at the Legends of the Motorcycle Concours in 2008, at the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Half Moon Bay. I'd brought two bikes for us to swap on the Sunday morning Legends Ride - neither a Norton, although I had a 1925 Model 18 racer at the time (it was hors de combat from my own relentless flogging). So George got to experience a vintage Sunbeam for the first time, as the photos show, which he quite liked ('My Norton is faster', of course he said), but preferred a spin on 'The Mule', my 1933 Velocette KTT mk4, which shared his favorite Norton's camshaft up top. Well actually it was the other way 'round, as Norton copied the Velocette design! Which he grudgingly admitted with a half-smile as he hand-rolled another cig.

A few days prior, we'd picked up a pair of racing Nortons from California collector Paul Adams, which were entered into the Concours, and it would be hard to imagine two more dissimilar characters, who both loved Nortons with passion. Paul Adams is an ex-Navy pilot of many years' experience, with the unflappable reserve of a military man, and George, well, flapped. Those two were chalk and cheese, and barely kept from breaking into open argument! Still, George later admitted Paul had a very nice collection, and that his workshop was really clean.

Something else he left behind; his incredible self-published love poem to Norton, created from his personal archive of early factory press materials, photos, and documents - 'Flat Tank Norton'. If you're a fan of early Nortons, it's essential reading, and an entertaining mix - some of the early photos of James Landsdowne Norton himself can be found nowhere else. 'Flat Tank Norton' is the kind of book only a devoted enthusiast can produce, as a publisher would have squeezed out the quirks to increase 'general interest', but they would have taken out the George factor, which is what give the book its tremendous charm. It needs a reprint, as copies run on Amazon for nearly $1000!

Another memorable moment with George came not on a bike, but in one of his select few cars, at the 2013 Vintage Revival Montlhéry meeting. He'd brought his c.1908 Brasier Voiture de Course after breaking down somewhere in France, while driving the all-chain drive monster all the way from his Somerset home. He'd sorted the brakeless beast, and was enjoying flying laps around the banking, and offered me a ride, which I accepted with something like fear. George drove like he rode, and the Brasier had no seat belts, roll bars, suspension to speak of, or front brakes, but it did have an enormous 12 Liter Hispano-Suiza V-8 OHC aeroplane engine with 220hp on tap! I put myself in the hands of Fate, and George. I climbed aboard, clinging to the scuttle, and filmed the ordeal with one hand, laughing 100% of the time, as he slid the rear end on the short corners, and got as high up the banking as he could, while the behemoth shuddered, roared, bucked, and squealed. Unforgettable, just like the man.

'Ton Up!' Exhibit In Cyril Huze Post

This has been an incredibly busy summer for The Vintagent: writing a big chunk of the BikeExif/Gestalten book 'The Ride', organizing the 'Ton Up!' exhibit for Sturgis Bike Week, and writing the 'Ton Up!' book for Motorbooks. Cyril Huze stopped by the 'Ton Up!' Michael Lichter exhibition hall at the Buffalo Chip in Sturgis, and filed the following report on his mega-popular Cyril Huze Post on Aug. 6th, 2013. It's worth a click-back to his site, to read the comments attached, which are always an entertaining mix on CHP...

From the Cyril Huze Post, Aug 6 2013:

TON UP EXHIBITION: SPEED, STYLE AND CAFE RACER CULTURE EXHIBIT AT THE STURGIS BUFFALO CHIP

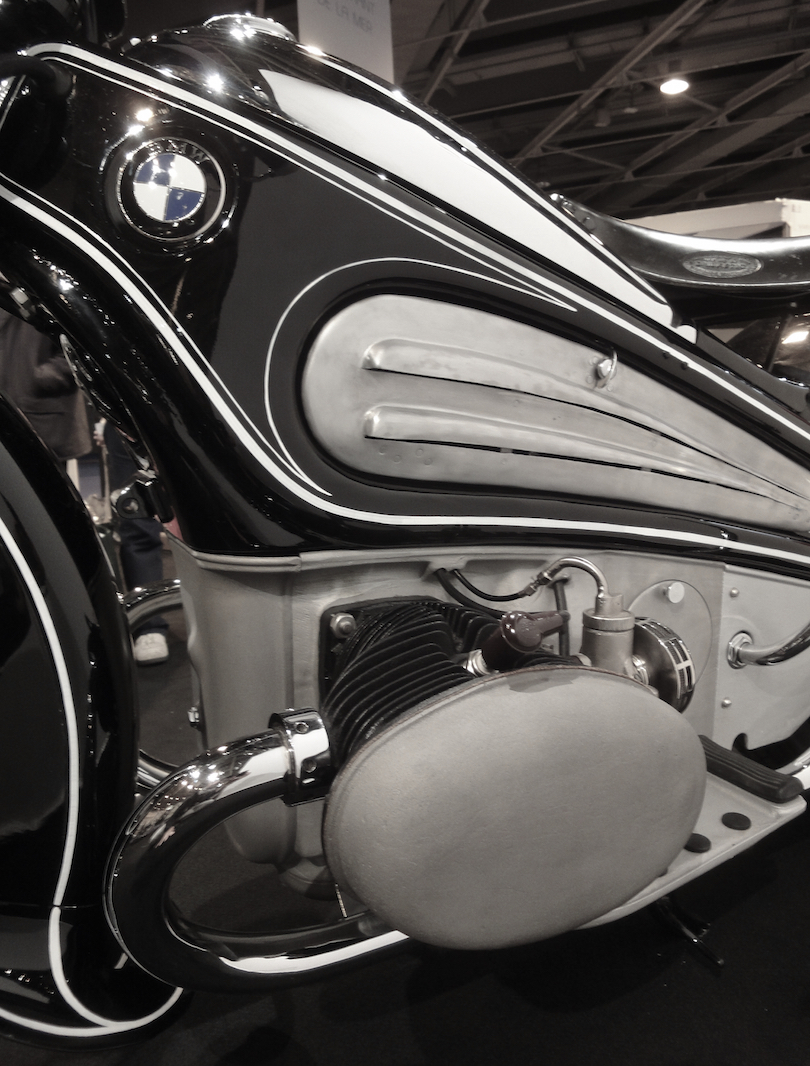

The Best Bike BMW Never Made?

The 1934 BMW ‘R7’ prototype is one of the most talked-about and best-loved motorcycles of the 1930s, yet it never left the factory, and was known only through a single, mysterious photo for over 70 years. The life story of this graceful machine is an untold tale of aesthetic movements, internal factory politics, and harsh commercial realities, in which this lovely motorcycle remained a ghostly ‘might have been’.

First conceived in 1933, the R7 began with a simple brief; create a wholly new motorcycle as ‘range leader’ to replace the R16, introduced in late 1928. The R16 used a chassis built from stamped-steel pressings (sometimes called the ‘Star’ frame), a cost reducer which eliminated the skilled labor necessary to weld or hearth-braze a tube frame. Previous BMW frames had a Bauhaus simplicity, while the pressed-steel ‘Star’ gained a shapely Art Deco flair. The new look begged an aesthetic question too compelling to ignore, given the general industrial trend towards Streamlined shapes on cars, airplanes, trains, and toasters. If the R16 whispered Art Deco, what would a total embrace look like?

The responsibility for this new machine likely fell to Alfred Böning, the designer of BMW motorcycle chassis from the 1930s onwards. While no names were attached to the curved frame and swooping mudguards of the R7, “it is perfectly clear the hand of an artist was involved”, according to Stefan Knittel, author of several books on BMWs. The prototype R7 is elegant, simple, and perfectly balanced – did Böning unleash a hidden flair for styling, or were BMW automotive ‘fender men’ called in for a bit of curvaceous appeal? In the early 1930s, individual designers were rarely celebrated, although a few ‘stars’ in the industrial design world were rising, like Raymond Loewy and Norman Bel Geddes. BMW first gave kudos to their ‘pencils’ with the 1940 Mille Miglia streamlined racing cars…in the 1980s! No surprise then that so little remains of the R7’s genesis.

While the styling was obviously radical for BMW, the engine and gearbox were equally innovative, a fact discovered only during restoration of the dismantled R7, in 2005. Likely drawn up by Leonhard Ischinger, BMW’s ‘engine man’ in the 1930s-50s, the engine bears a superficial resemblance to the rest of BMW range, but the crankcase and gearbox castings are one-offs, as are their internals. The cylinder heads and barrels are a single casting, as per aero-engine practice at the time; one less joint to leak. The unique crankcase was shaped to seamlessly fit the monococque chassis from which it hangs. The front forks are a BMW first in being fully telescopic, leading the rest of the motorcycle industry by several years. Internally, the camshaft is placed atop the crankshaft, and the gearbox uses a primary shaft separate from the gear cluster, which slows down the gear speed and helps reduce the notorious shaft-drive ‘clunk’ when shifting. These last two ideas appeared in BMW bikes in the 1950s, when Böning was finally able to incorporate them on production machines.

The R7 weighed in at 165kg (5kg lighter than the R16) with engine capacity 793cc, producing 35hp @ 5000rpm (2hp more than the R16), breathing through Amal-Fischer carburetors with accelerator pumps (!) and swill-pots to cure any fuel starvation while cornering. Thus the experimental model had seriously hot performance, being capable of over 90mph while looking sensational. Superbike, anyone?

When completed in 1934, the R7 wasn’t exhibited or press-released; it appears to have been shelved immediately.The first the world knew of the ‘Art Deco’ BMW was a magazine article on the new R5 model in 1936, which included a retouched side-view photo captioned “what could have been”. That solitary photo launched decades of mystique around the R7, giving rise to the Question: why on earth didn’t BMW manufacture this beautiful machine?

Complicated forces worked against the R7. While the prototype is a hand-fabricated one-off, actual production would require huge investment in tooling for the metal pressings, new castings for the engine, gearbox, and cylinders, plus setup for all the unique internal parts. With only a few hundred of their excellent R16 sold, recovering the tooling investment was unlikely. Also, BMW were aware that motorcyclists are very conservative consumers, and bikes which read as ‘design exercises’ in sheet metal were never successful: the Mars (Germany), the Ascot-Pullin (England), and the Majestic (France) all trod a similar path to the R7, being ‘ideal’ designs of innovation and great style, yet doomed to commercial failure. Motorcyclists of the Vintage period, dedicated gearheads all, wanted the fiery beating hearts of their mounts visible in all their complication; this remains our enduring delight.

Internal factory politics certainly played a hand as well. Rudolf Schleicher, chief of motorcycling at BMW, was convinced the ‘range leader’ should be a sporting motorcycle, not a luxury machine, and factory notes indicate his plan for a supercharged motorcycle for the public! The prototype of his blown roadster was seen in the BMW ISDT team of 1935, but such an ‘ultimate motorcycle’ was seriously impractical; “Every owner would need his own specialist mechanic, and BMW didn’t want private competition for their factory racing team,” notes Stefan Knittel. As it was, neither Blown nor Deco was produced, but the telescopic forks and curvaceous mudguards of the R7 did find their way onto the R17 model.

The R7 was dismantled, but never destroyed; it remained at the factory, strapped to a wooden palette in the factory basement, well known to BMW employees. It must have been dear to Alfred Böning’s heart, as he kept it close at hand until his retirement in the 1970s. By this time, BMW was re-collecting its history, with their famous ‘bowl’ museum opening in Munich for the 1972 Olympics. While a clamor arose in the 1980s to revive the R7, it wasn’t until 2005 the task was handed to two legendary restorers; Armin Frey undertook the mechanicals, while Hans Keckeisen massaged the sheet metal. The results are sensational.

The 1934 R7 prototype is an unquestioned design success - a graceful and beautiful study of flowing lines, curves, and feminine masses. Almost to a person, especially to non-motorcyclists, it is considered one of the most beautiful motorcycles ever made. As good as it is, the R7 is a total philosophical departure from what is best about BMW during its first 60 years; restraint. The extravagance expressed by the R7 is shockingly French - more Delahaye than Bauhaus.That the R7 was never serially produced makes complete sense, but 75 years on, she’s still a heartbreaker.

This article was written for the 2011 Amelia Island Concours catalog. Copies of the catalog may be available. Many thanks to Stefan Knittel for his insights and information.