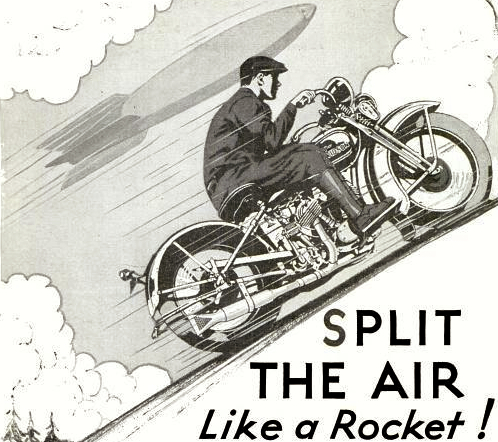

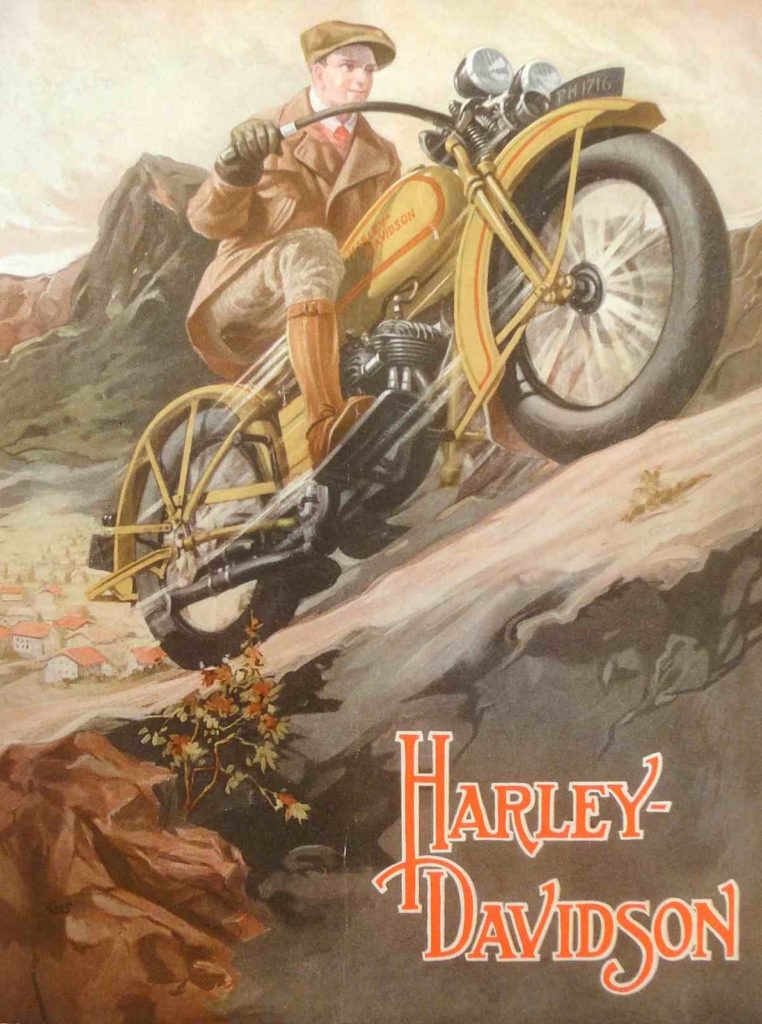

Selling Speed

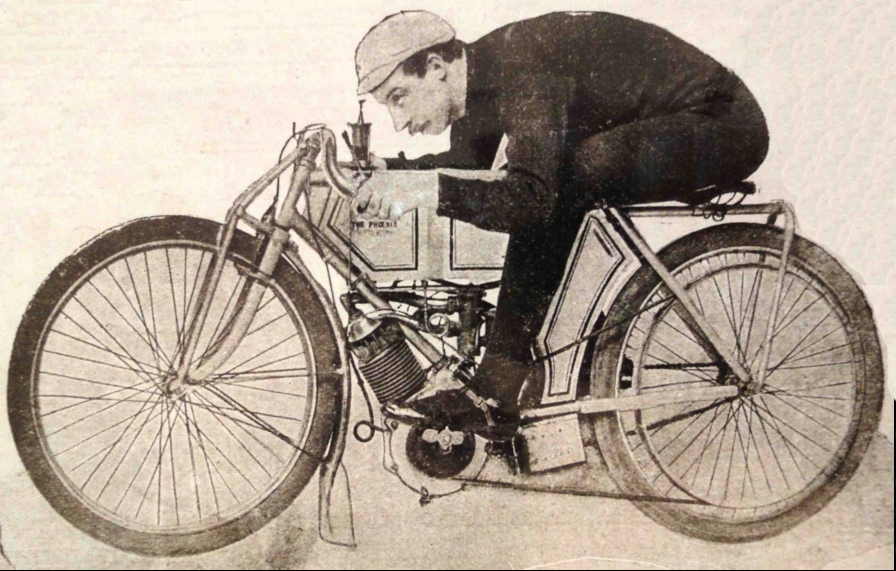

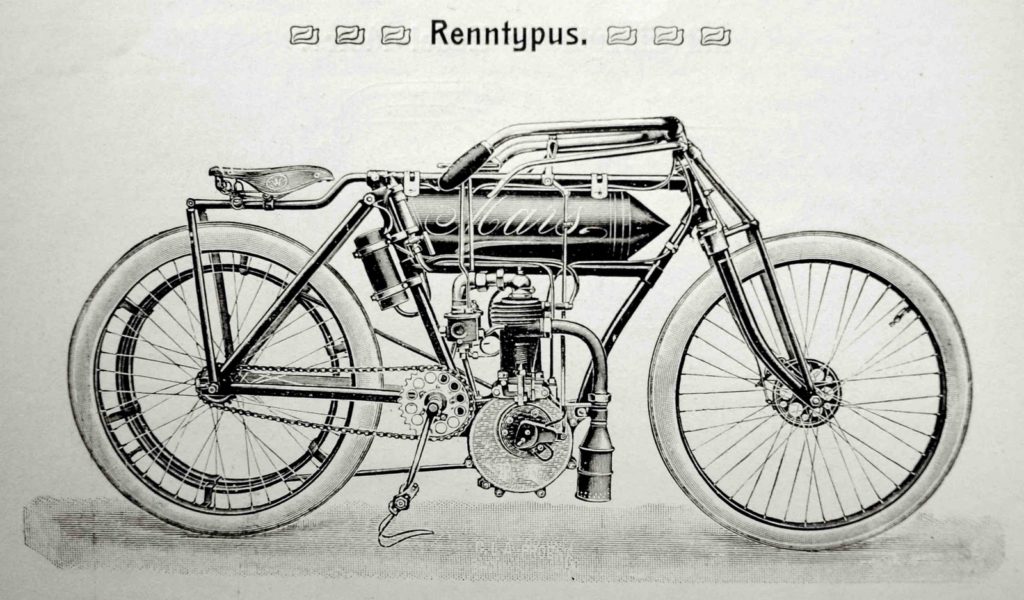

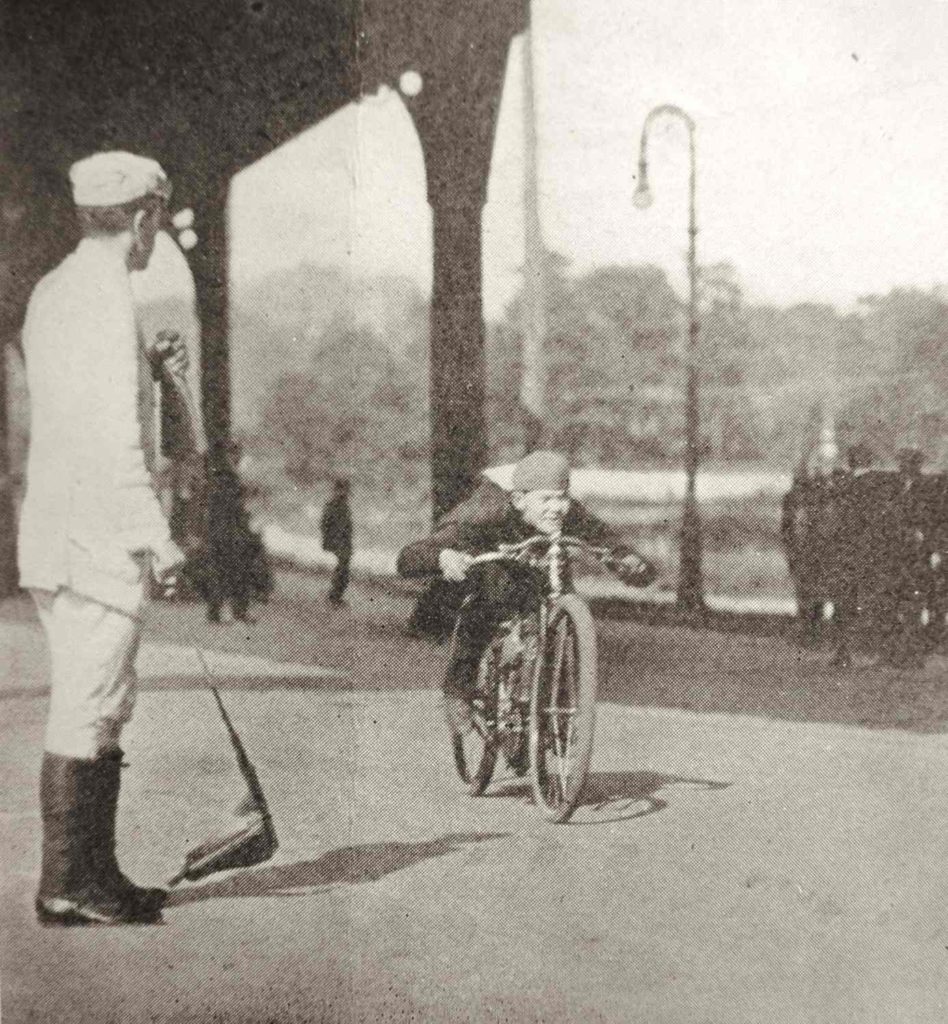

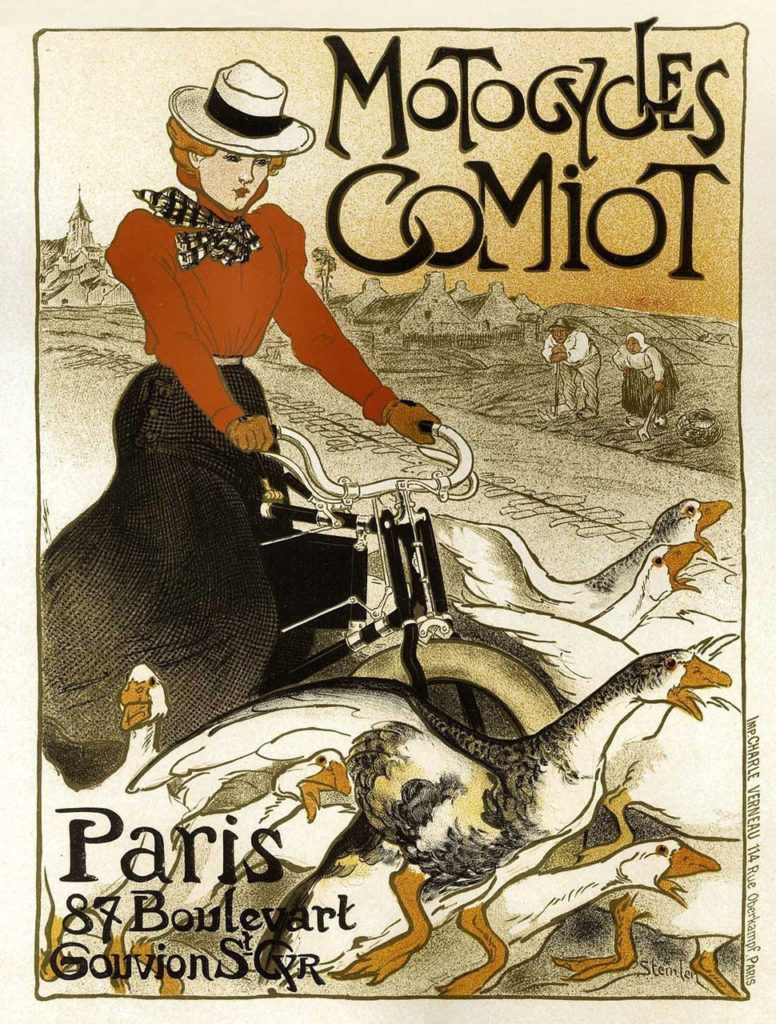

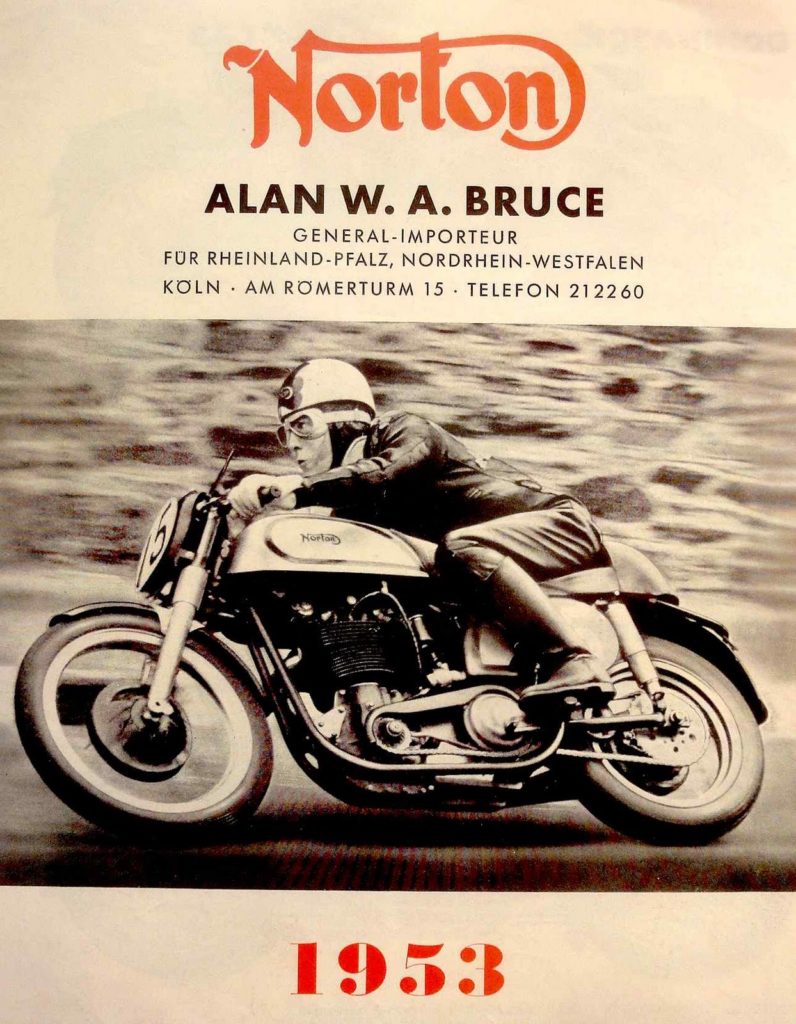

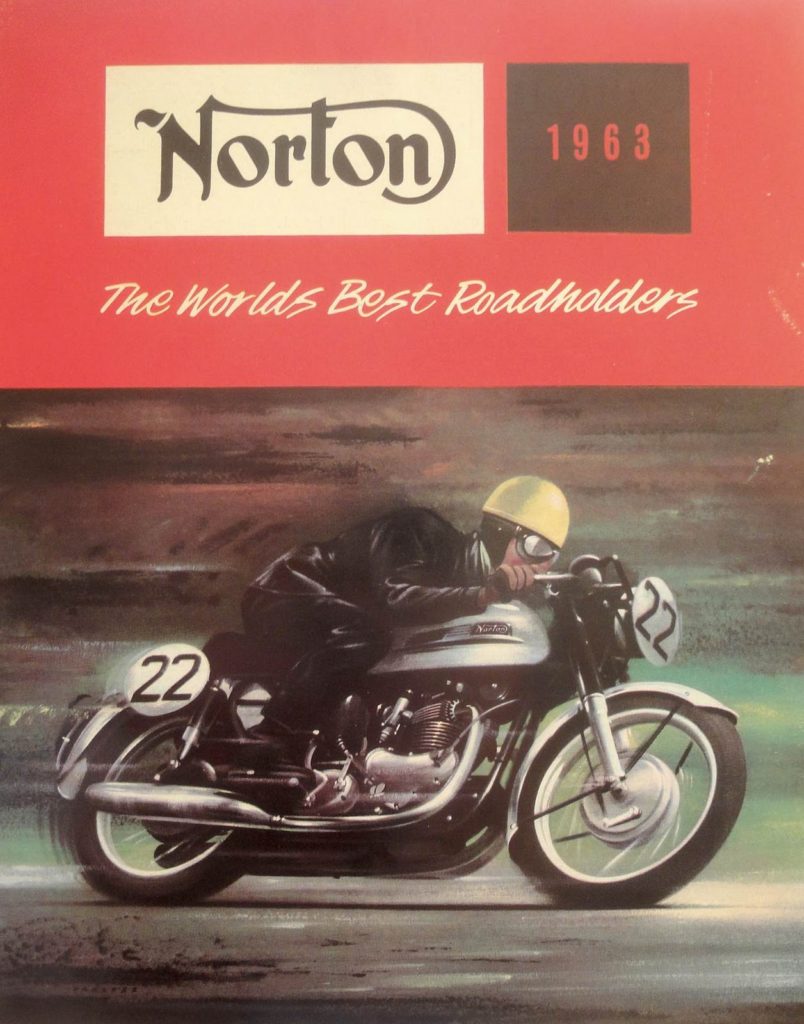

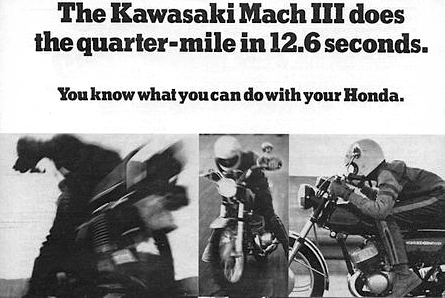

The first motorcycle race started when the second motorcycle was built. And the first motorcycle advertisement was placed immediately post-finish, crowing the winner's superiority. Motorcycle ads have a natural ‘hook’ in the lure of Speed, although manufacturers have had mixed feelings about selling what riders really wanted, deep down in their speed-demon souls. From the first days of the 20th Century, builders and buyers of motorcycles have played a complex dance around the subject of Speed, with the Industry anxious to spread a message of respectability and docility for their noisy, horse-scaring moto-bicycles, keeping a low profile about the exhilaration of pulling the throttle lever all the way back. Customers were savvy to the game, navigating the great restrictive forces of Love and Law - parents, spouses, and the police – who could not abide an explicit celebration of the narcotic draw of Competition and its handmaiden, Danger. It took decades before the public acknowledged that a dangerous, speed-crazed hooligan lurks in the puritan hearts of all motorcyclists, hell-bent on going faster than anyone on the damn road.

Gillian Freeman, Eliot George, and 'The Leather Boys'

We've just learned that Gillian Freeman, whose 1961 novel "The Leather Boys" was made into the seminal Rocker/Ace Cafe/Cafe Racer movie of the same name, has died age 89 in London. The novel was commissioned by the London publisher Anthony Blond, who reputedly suggested she write a novel depicting 'Romeo and Romeo in the South London suburbs'. Freeman wrote the book under the pen name Eliot George, an inversion of 19th Century writer Mary Ann Evan’s nom de plume George Eliot, used to conceal her identity as the female author of the astounding "Middlemarch", and the equally famous "Silas Marner". Freeman's novels were not literature in the same league as George Eliot's, and "The Leather Boys" is a one-night read, and a pulpy novella that was nevertheless groundbreaking for its frank depiction of a homosexual relationship as spontaneous and free of even the consideration of shame.

“The leather boys are the boys on the bikes, the boys who do a ton on the by-pass. For their expensive machines, they need expensive leather jackets. They are an aimless, lawless, cowardly and vain lot with a peacock quality to their clothes and hair style.”

The two main characters, Reggie and Dick, become part of a casually organized gang of criminals who hang out at cafes much like the Ace Cafe. After committing rather senseless acts of vandalism and a successful robbery with the gang, Reg and Dick plan a robbery on their own, and Reggie is beaten to death by the gang members in retribution, which is followed by a trial in which the gang leader is convicted of murder.

Ms. Freeman also wrote several screenplays after "The Leather Boys", including for an early Robert Altman Film ("That Cold Day in the Park" - 1969), and also collaborated on scenarios for ballets with Kenneth MacMillan, including his “Mayerling,” about the Austrian crown prince Rudolph, and "Isadora" about Isadora Duncan. To motorcyclists, though, she'll always be remembered for "The Leather Boys", which remains the only semi-realistic account of working class Rockers in the early 1960s, and films their milieu with an accuracy only possible with the use of actual Ace Cafe denizens in the period. Godspeed, Gillian Freeman.

Paul d'Orléans is the founder of TheVintagent.com. He is an author, photographer, filmmaker, museum curator, event organizer, and public speaker. Check out his Author Page, Instagram, and

Paul d'Orléans is the founder of TheVintagent.com. He is an author, photographer, filmmaker, museum curator, event organizer, and public speaker. Check out his Author Page, Instagram, and

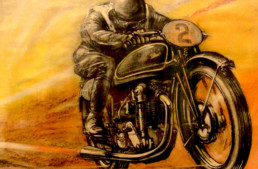

T.T. OK!

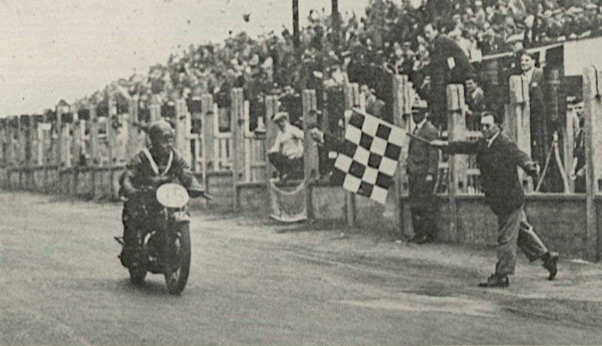

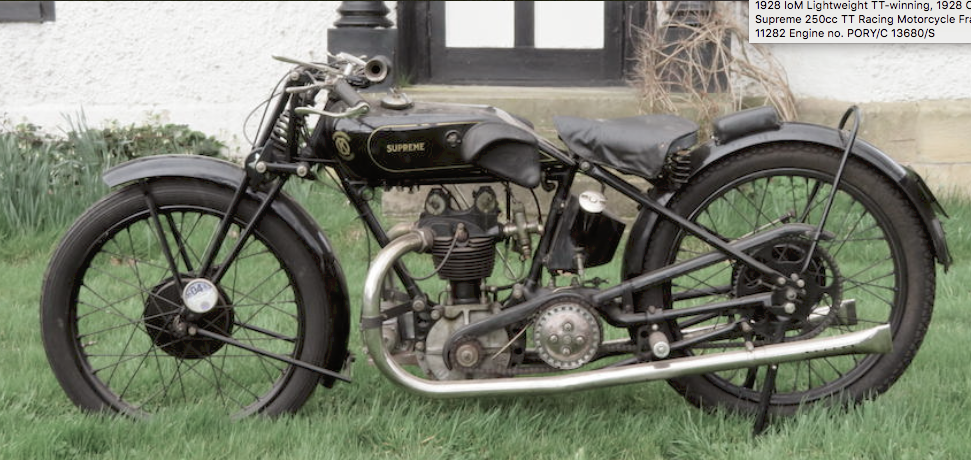

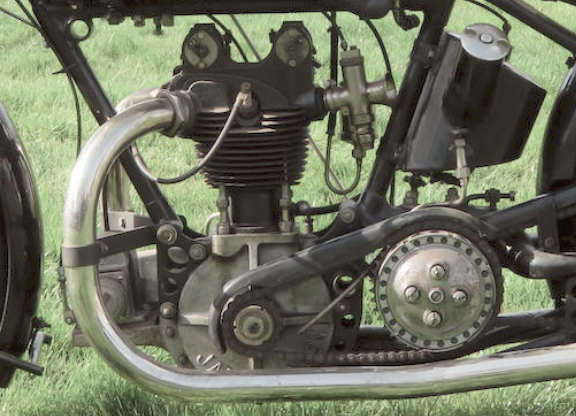

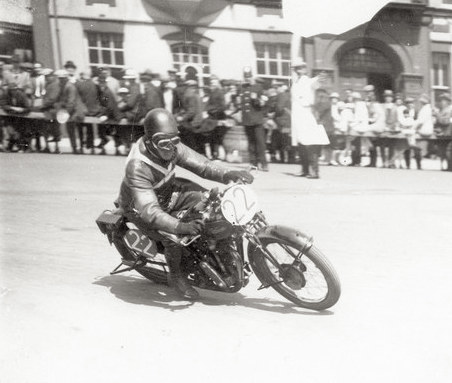

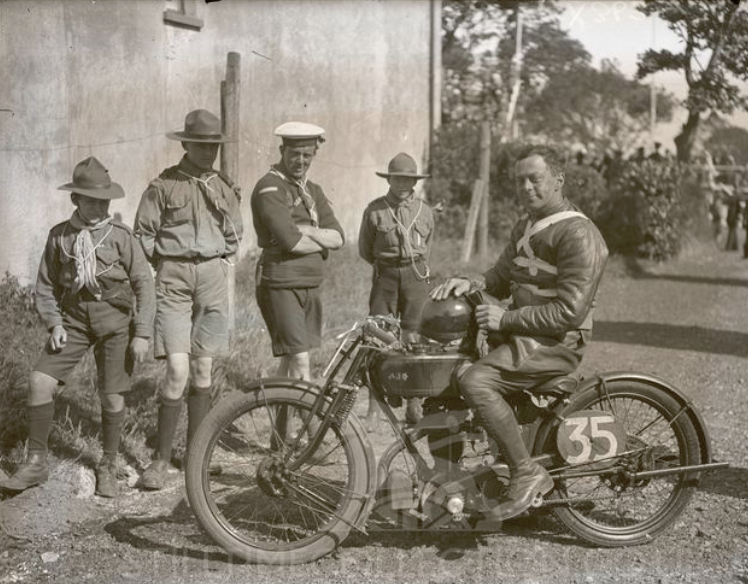

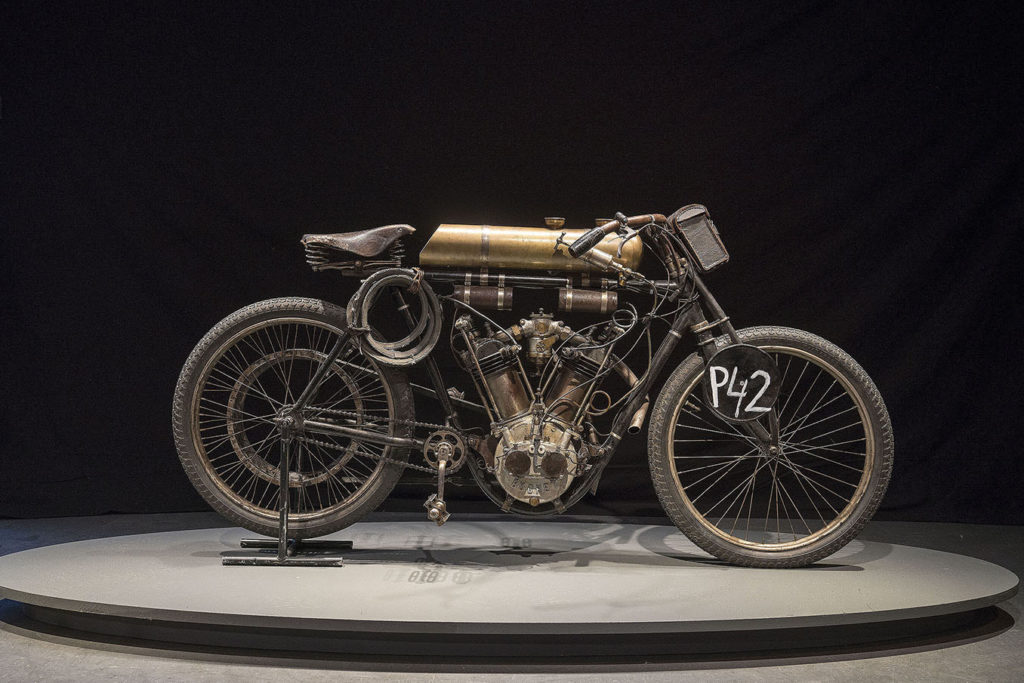

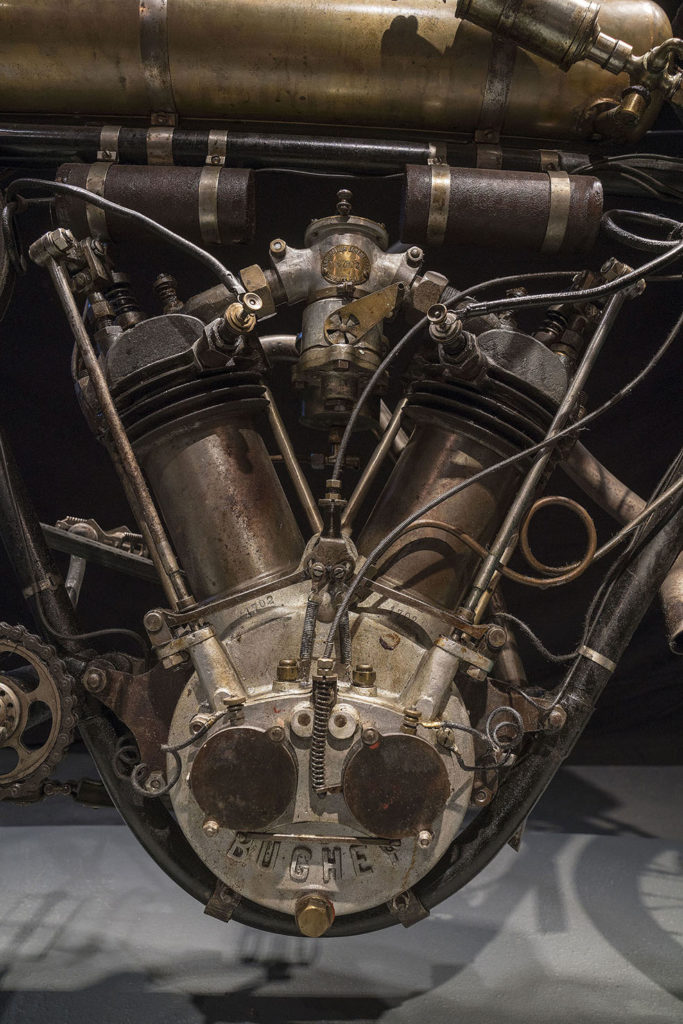

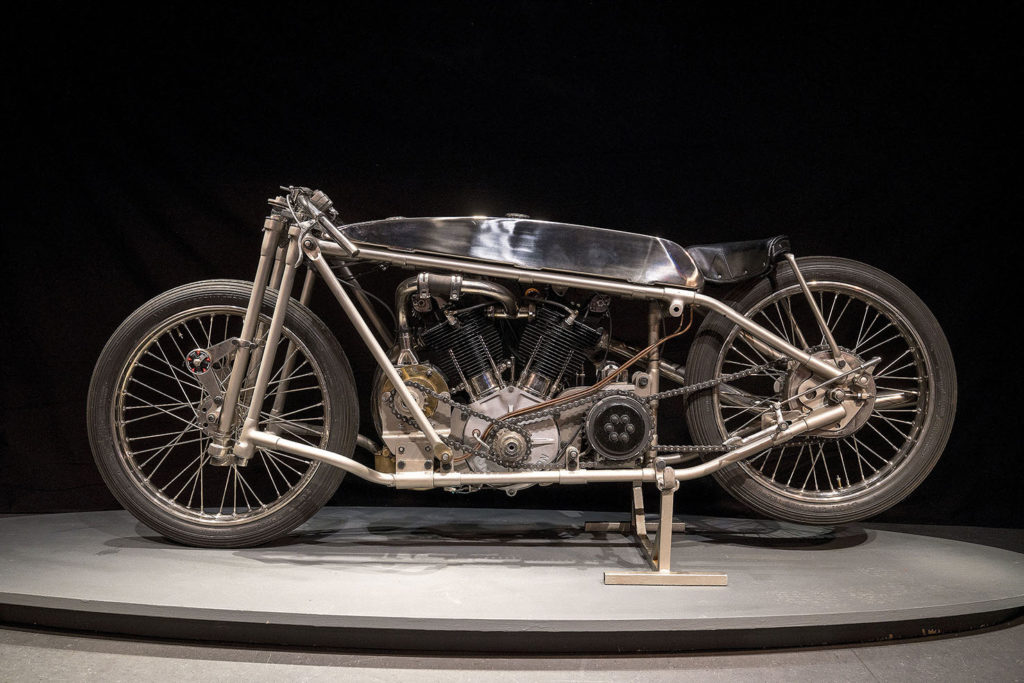

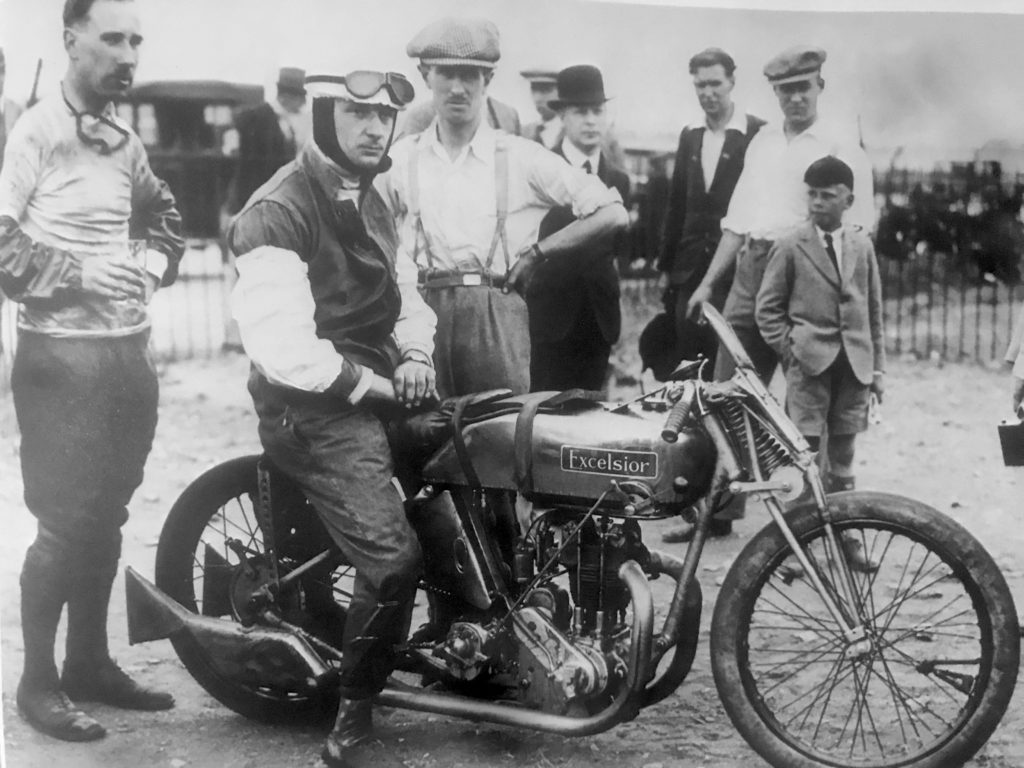

Among the many 'lost' motorcycle brands that once made headlines and won races, OK Supreme has become one of the most obscure. In the 1920s and '30s, though, they were a well-known British make, with some of the best graphic transfers in the industry, and a string of podium finishes in the Isle of Man TT. They had only one win on the Island, though, in the 1928 Lightweight TT (250cc), with Frank Longman riding.

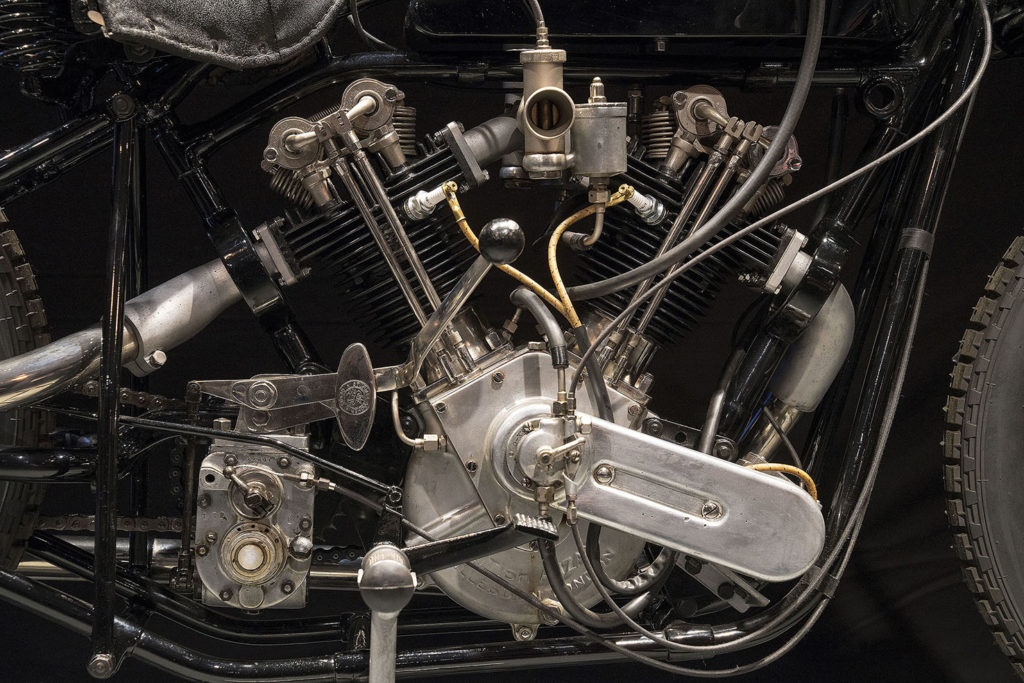

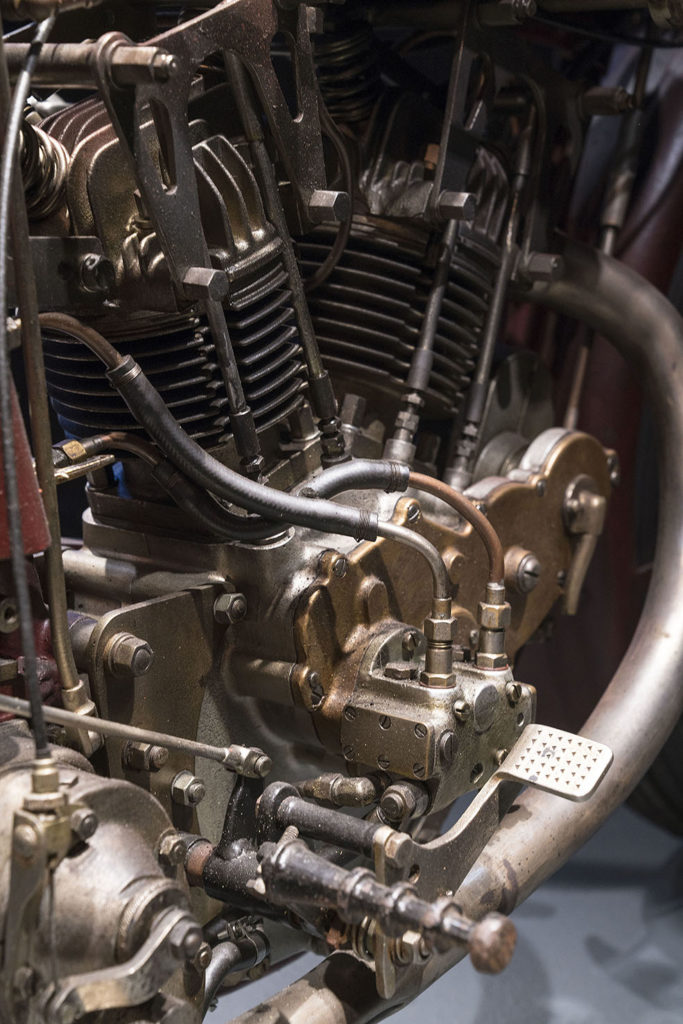

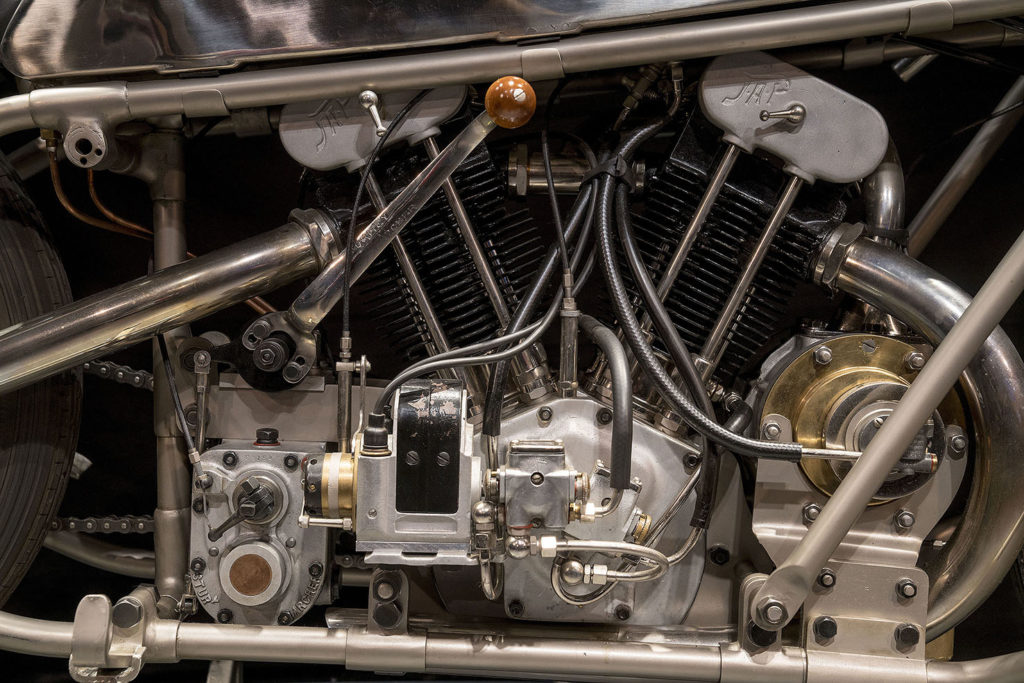

Perhaps the addition of 'Supreme' did the trick, for in 1928 they finally won the Lightweight TT, using a racing JAP engine. OK Supreme had a troubled practice period before the TT, as their new duplex-tube frame designed by G.H. Jones proved fragile, so Jones actually returned to the factory in Birmingham to fetch the previous year's racing frames, a traditional 1920s open-cradle design with the engine acting as a stressed member, with a triple-stay rear end to aid stability. The frame swap was slightly problematic, as the factory had already submitted paperwork for the machines with the A-CU for the '28 TT, so the 1927 frames had their VIN numbers stamped over by Jones to match the entry paperwork.

Longman's TT-winning 1928 OK Supreme has survived nearly a Century in mostly unchanged condition, and was registered for the road in 1932 under the registration CG 1150. An ex-TT winner must be the ultimate café racer for a Promenade Percy, the name attached to racy young men who rode flashy competition machines on the street... I'll explore the full history of the Promenade Percy in my next book, coming this fall. Check out my previous exploration of cafe racers for Motorbooks - Café Racers (2014).

The following is a period account of the 1928 Junior TT race from Motor Sport magazine:

"PURSUING the meal-time analogy, the 250 c.c. race should, perhaps, be described as the" soup" of T.T. week, though this year it would have been more appropriate if the Junior race were described as "cocktails," the lightweight as the hors d'oeuvres, and the Senior as the soup—in which element the riders were certainly involved! The Lightweight entry list promised a fierce tussle between Handley (Rex-Acme) and Bennett (O.K. Supreme), but during practice it became apparent that Frank Longman was seriously to be reckoned with, whereas Handley seemed to be treating this year's races with considerable diffidence.

Alec Bennett had evidently experienced trouble as he was not in the leading dozen, and after a very slow second lap, he retired with baffling ignition trouble. Thus, the issue was simplified, and for five laps Longman drew steadily away from Handley who, in turn, drew slowly ahead of the field, led by the consistent Hampshire rider, C. S. Barrow.

1. F. A. Longman (246 O.K.-Supreme) 2. C. S. Barrow (246 Royal Enfield) 3. E. Twemlow (246 Dot) 4. G. E. Himing (246 O.K.-Supreme) 5. C. T. Ashby (246 O.K.-Supreme) 6. V. C. Anstice (246 O.K.-Supreme) 7. S. H. Jones (246 New Imperial) 8. J. A. Porter (246 New Gerrard) 9. S. Cleave (246 New Imperial)"

[Full disclosure: Bonhams is a sponsor of TheVintagent.com]

Mecum Phoenix 2019 Preview

For its first-ever auction at Phoenix-Glendale AZ, Mecum is adding 100 motorcycle to its roster of 1100 cars. The March 14-17th auction will be televised on NBCSN, and we'll be interesting to see how the mix of four and two wheels will affect motorcycle prices, after their blockbuster, record-breaking all-motorcycle auction in Las Vegas last January. The featured lots include the mixed collection of Buddy Stubbs and the all-Triumph focus of the Hamilton collection, which seems of consistently high quality. While I won't be a TV commentator on the motorcycle auctions this March, my regular Las Vegas partners Scott Hoke and John Kraman will liven up the action on the small screen (check TV times here).

'Rekordjagd auf Zwei Rädern'

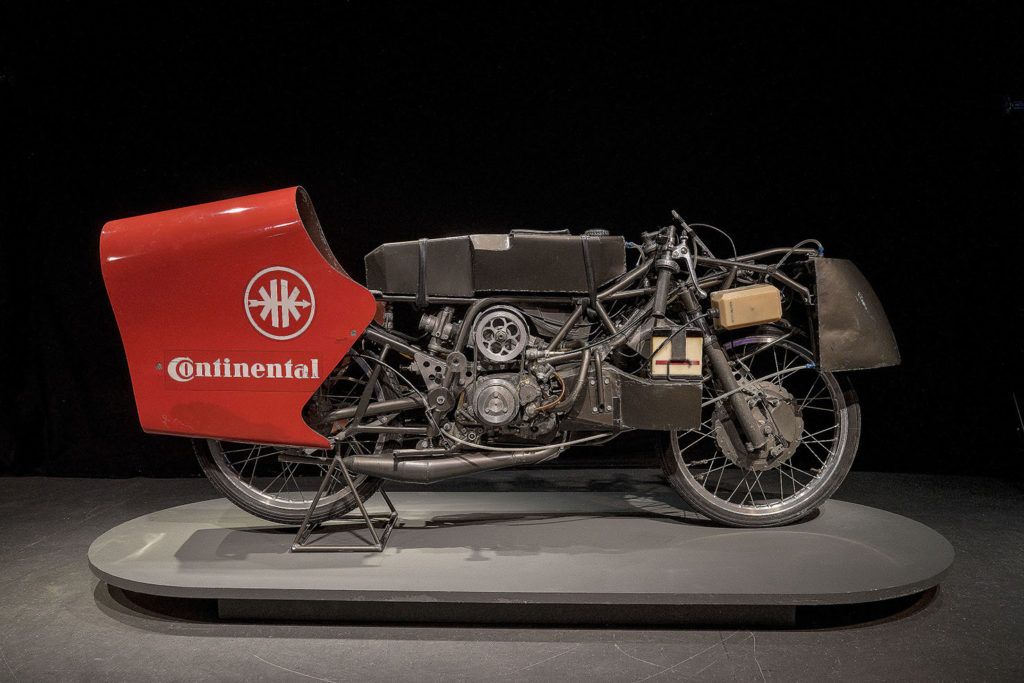

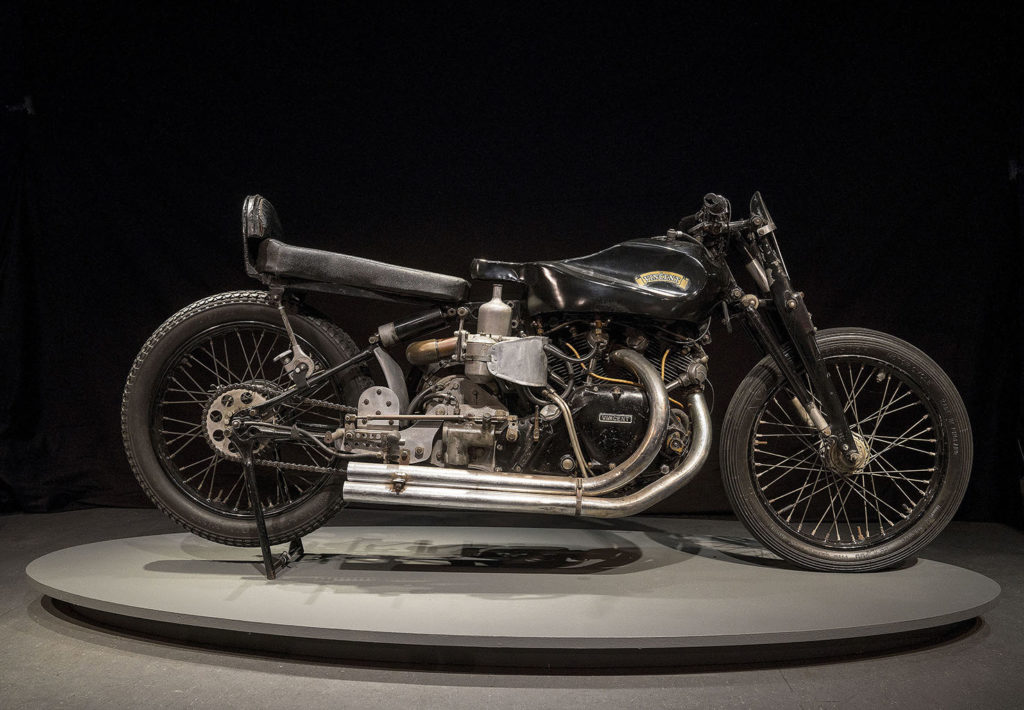

The esteemed motorcycle museum in a fabulous old schloss in Neckarsulm, Germany, has a new director, Natalie Scheerle-Walz, who has expanded its program of exhibitions, with the ambition of transforming this charming cabinet of curiosities (and the oldest motorcycle museum in Germany) into a living cultural history center. Formally known as the Deutsches Zweirad-und-NSU Museum Neckarsulm, the space has long housed the nicest display of two-wheelers in Germany, including ultra-rare factory racers from NSU, who were based in a factory nearby, on the Neckar river. If you've ever drooled over photos of the gorgeous, World Championship-winning 1950s NSU Rennmax racers, this museum is your chance to see them in the metal and up close - definitely worth the visit.

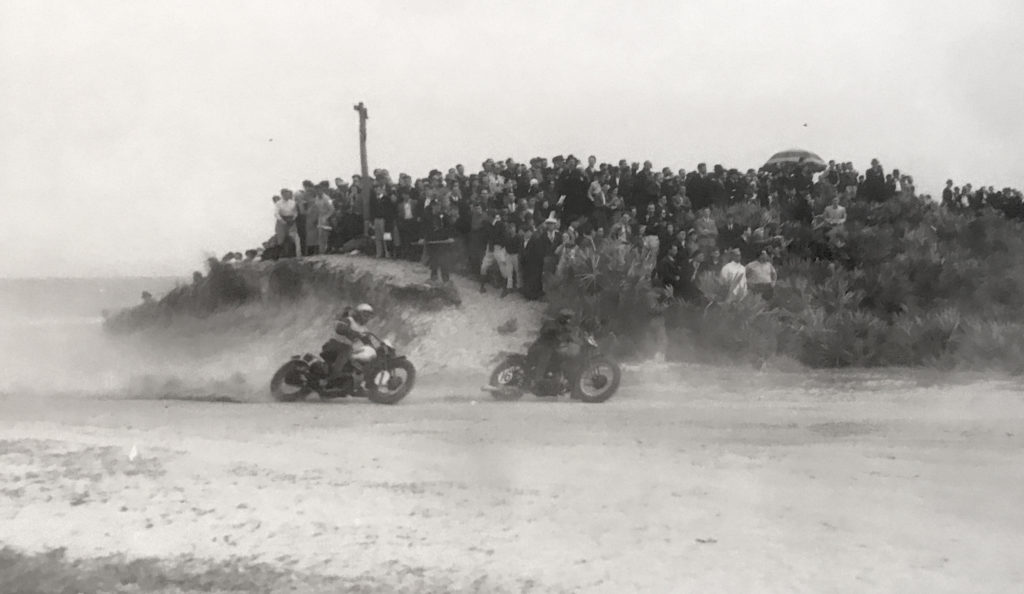

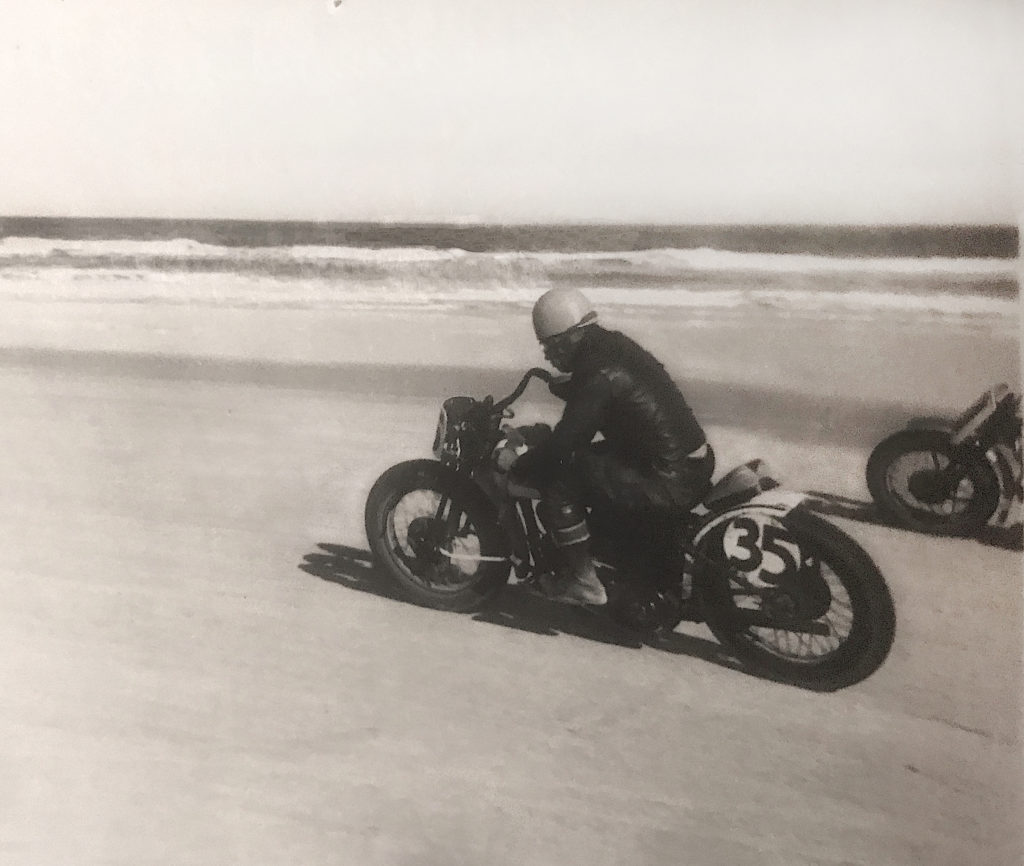

The First 'Handlebar Derby': the 1937 Daytona 200

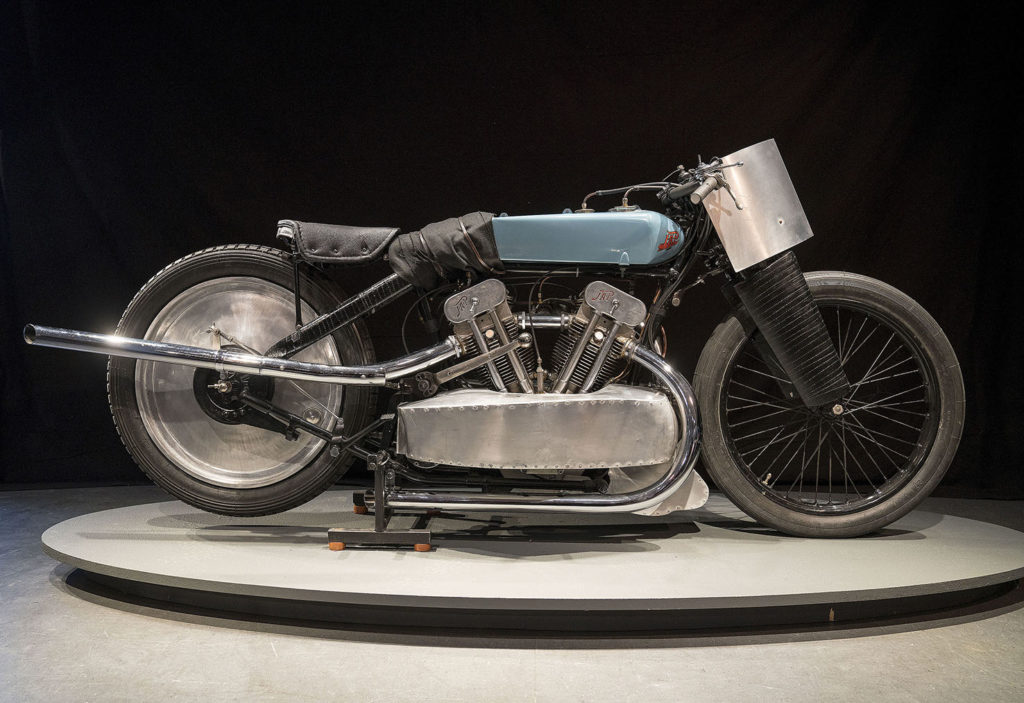

Daytona/Ormond Beach had been used for speed trials since the dawn of motorcycle competition in the USA, in 1902. The earliest speed records for cars and motorcycles were taken on the Ormond Beach end of this very long strand, probably because the Ormond Beach Hotel was the only hotel in the area, as difficult as that is to imagine if you've been to Daytona today. At the turn of the Century these beaches had yet to be developed, but were one of the few places in the country where flat-out speed could be explored without harassment by local authorities. Land Speed Record attempts continued through 1935, when Donald Campbell and his Bluebird racer shot between the pilings of Daytona Pier at over 300mph! Everyone involved knew the speed jig was up, and the whole speed circus decamped to Bonneville for their annual fun, once a minimum of facilities were established in that former desert wasteland.

2019 Las Vegas Auction Recap

The 'bike week' in Las Vegas hosts the world's largest motorcycle auctions, with a total of 1850-odd vintage machines on sale this year. With two sales during the week, hosted by Mecum Auctions and Bonhams Auctions [full disclosure - both supporters of TheVintagent.com], the variety of motorcycles available makes this literally a 'something for everyone' event. All price ranges, all types, makes, configurations, ages, and countries of origin were present, from a replica 1894 Hildebrand&Wolfmuller, the world's first production motorcycle, to sport bikes from 2016, with literally everything barring steam motorcycles represented on the auction block. Many come to buy, many come to sell, but all come to enjoy seeing that many old motorcycles in one place, as the auctions are by default also the largest vintage motorcycle display in the world. It's a museum where everything is for sale, although you never know what any machine will fetch once the hammer falls. Bargain or world record? It's impossible to tell beforehand.

- 1938 Triumph Speed Twin $175,500

- 1939 Crocker Big Tank $705,000

- 1967 Velocette Thruxton $56,100

- 1974 Münch Mammut TTS-E 1200 $112,000

- 1981 BMW R80 G/S $38,500

- 1981 Benelli 250 Quattro $15,400

- 1982 Bimota SB2 $56,650

- 1986 Ducati Mike Hailwood Replica $49,500

- 1986 Norton Interpol II $33,000

- 1988 Honda RC30 $121,000

- 1992 Honda NR750 $181,500

The takeaway: most of these are for post-1980 bikes. That's the hottest part of the motorcycle marketplace now, with recognition (in the form of money) going to the best motorcycles of the 1980s. Generally, bikes from the 1920s/30s/40s held their value (barring the '25 SS100 at $357,500, about $100k off the expected price), while those of the 1950s/60s slipped on the whole.

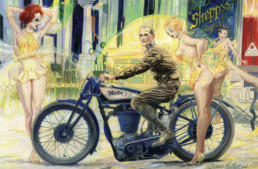

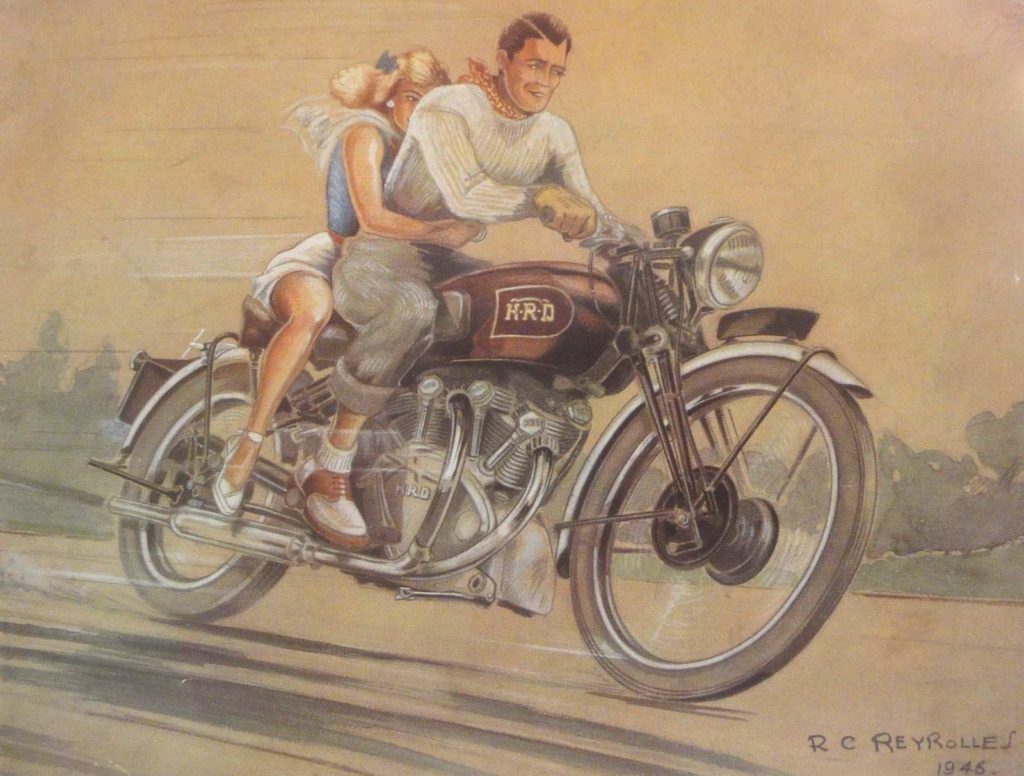

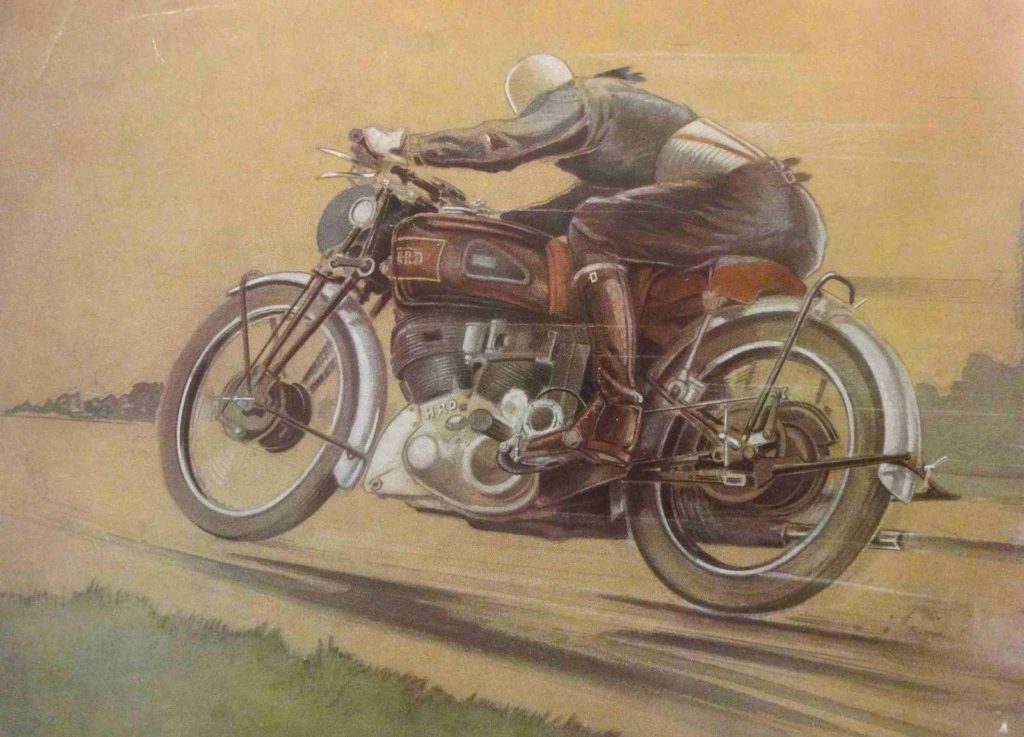

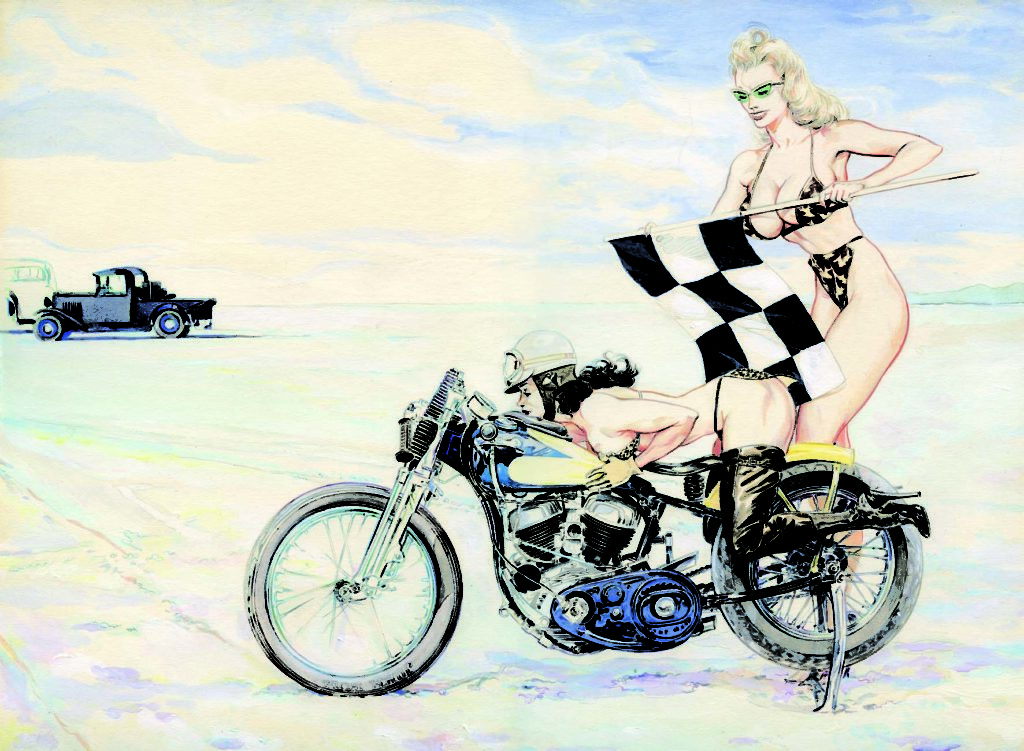

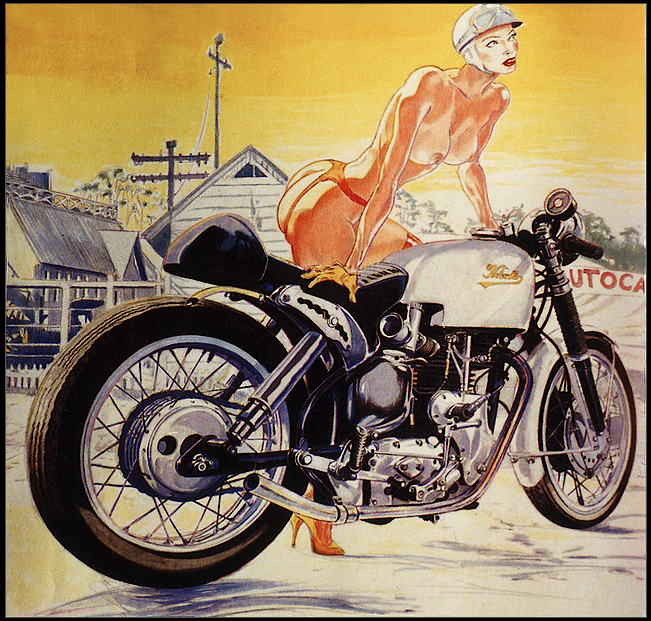

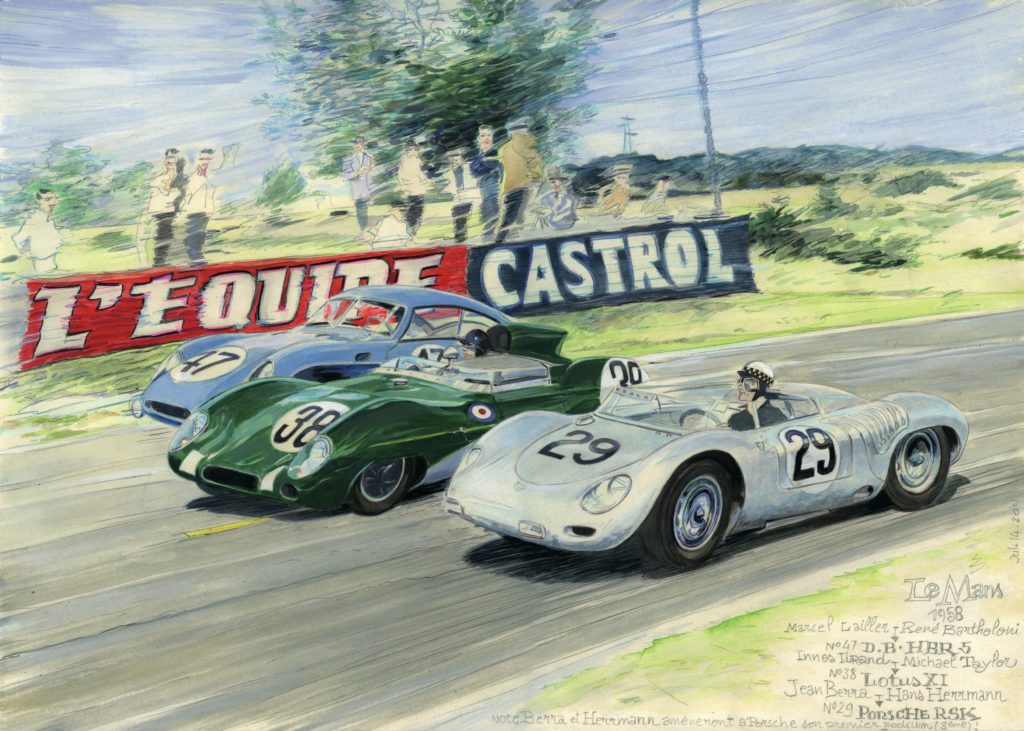

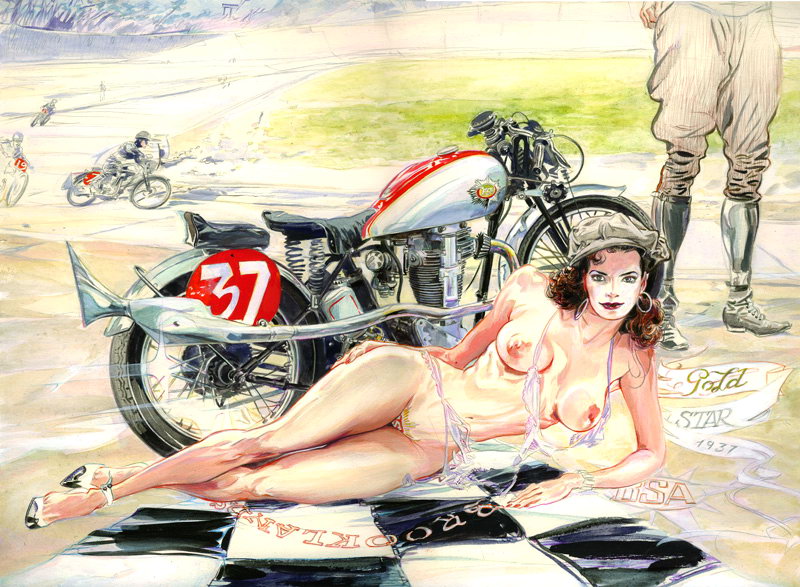

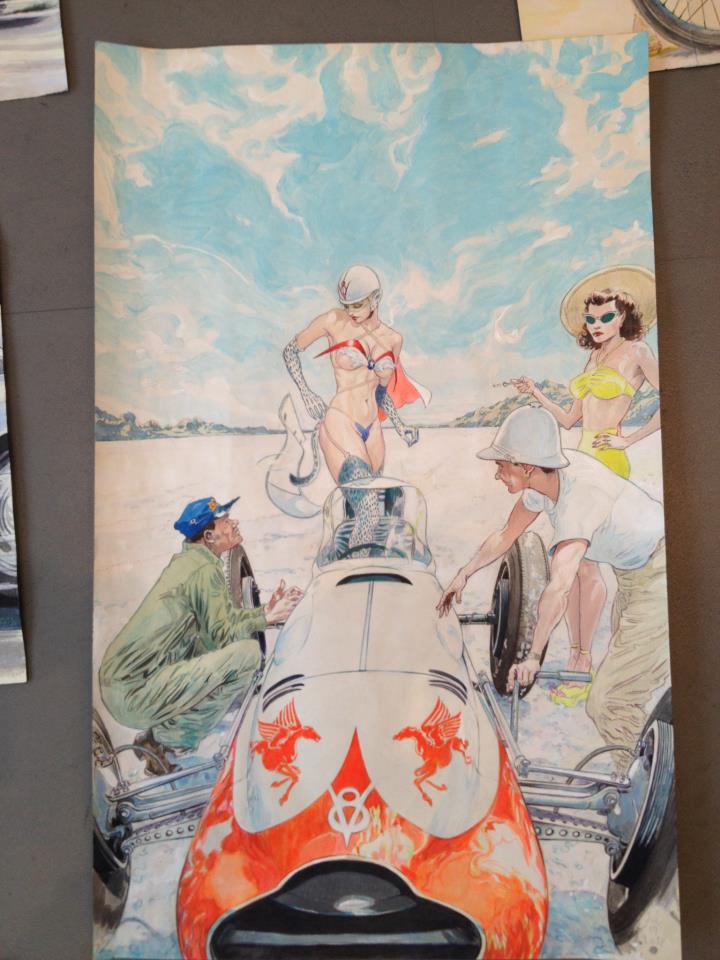

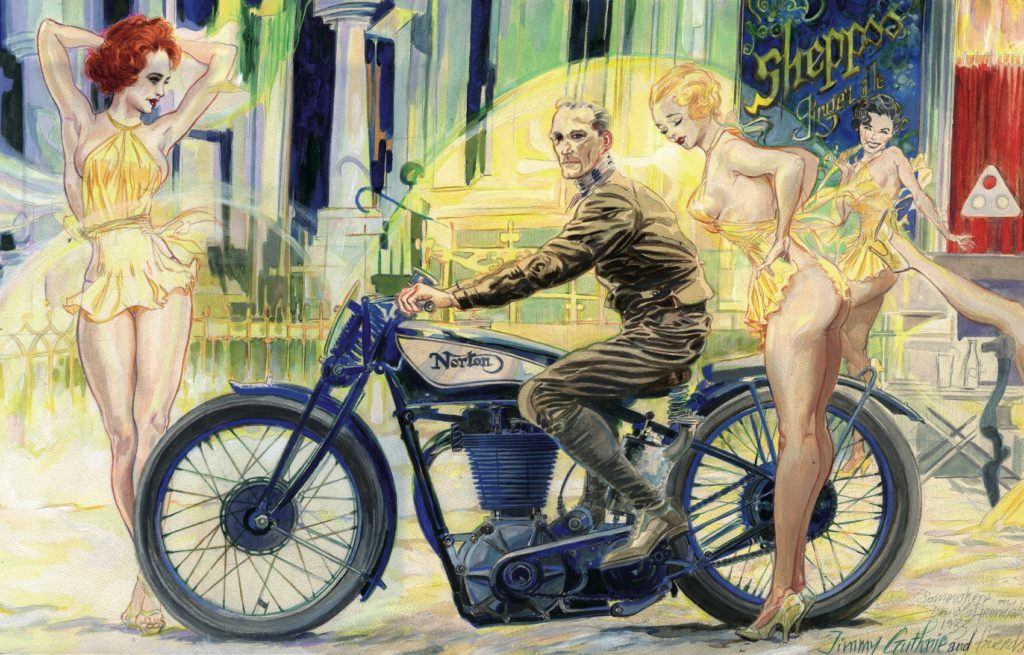

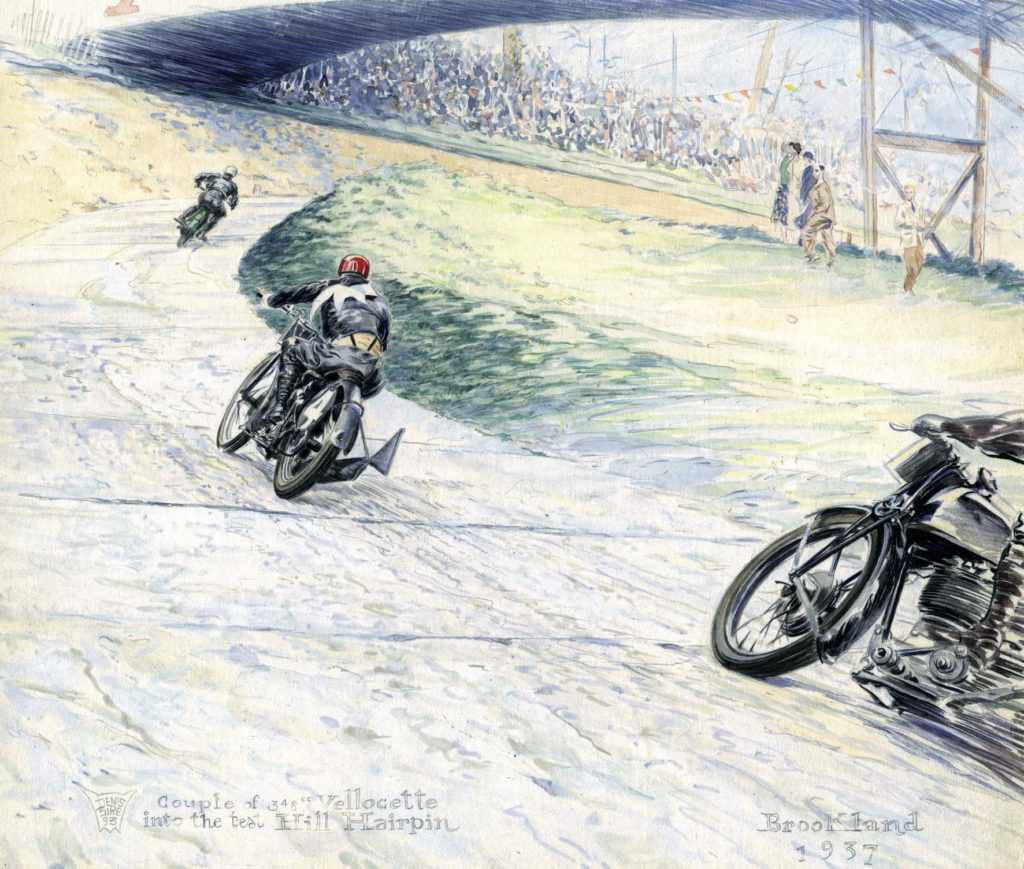

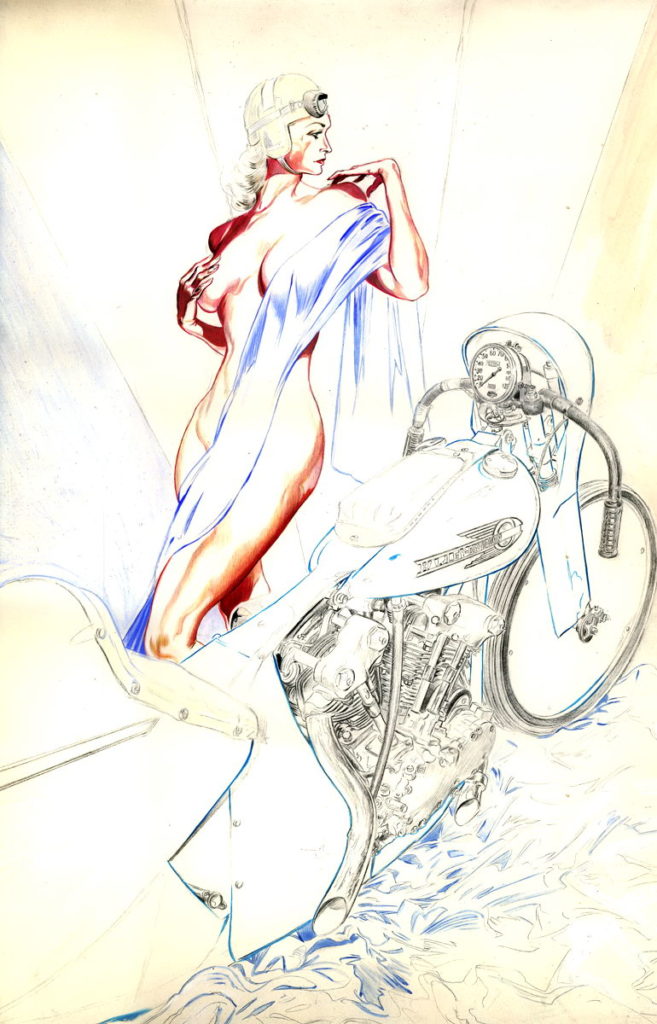

Denis Sire

Legendary motoring artist Denis Sire, champion of inserting fantastical pinup girls into historical situations, has died. His work is well known to a generation who came of age in the 1980s, during the second wave of Rocker style, when Sire was already well established as an artist and musician in France, and his work was exposed worldwide in popular magazines. Sire was born in 1953 at Saint Nazaire on the Atlantic coast, and studied art in Paris at ‘L’Ecole des Arts Appliqués. His work is most familiar to 1980s readers of Playboy and Heavy Metal magazines, and I've had a copy of his Velocette Thruxton sketch on my office wall since the mid-1980s, and admired his outrageous mix of scantily clad femininity with hot rods, record breakers, fighter planes, and motorcycles. Meeting Sire in person last February at Rétromobile in Paris, I discovered he also possesses a unique sense of style, befitting his outré artistic ouevre.

The following excellent interview appeared in 2015 on the French website, Monsieur Vintage, who regularly featured his work. I've translated it from the French for our readers, as it gives the best insight to his character and story. Vale, Denis:

Denis Sire you have 2 facets, rocker and draftsman. In a few words, who are you? I am a dandy rock and roller and refined designer, although the profit is not always the result, but in any case I feel free.

My Japanese moment was very short, I followed up with a BMW R68, Aermacchi 350 Sprint, Harley Sportster 1000 XLH, H-D Duo Glide (which I never rode), a BSA B31, a Norton 850 Commando (Fastback), an H-D Cafe Racer (cast iron Sportster), a Panther Model 100, a Triumph TRW (ex-Paris Police), BMW K 75. Then a Buell M2 Cyclone (orange fusion), for me the greatest pleasure on 2 wheels.

Later we moved to Sceaux fortunately [a suburb of Paris - ed.]. We were in a refuge city, a garden city, great. With the Parc de Sceaux in the 60s it was great, it was crazy, still old-fashioned with small farms, the shopping street, there were still printing houses, those who printed Bibi and Fricotin, Feet Nickelés ... I was skateboarding and cycling, and at 14 I rescued a moto Solex from a cellar. I went straight to bikes, there was no moped between the two. I bought a Honda PC50, with 4 speeds and a horizontal motor: I though that had class. My father told me "You can ride a moto, but you have to buy them."

Later, I met Frank Margerin, who studied Applied Arts at the same time as me, and I went to flea markets with Los Crados, and we formed a good band. I was already doing comics, I decided it at age 11 because my father bought me Spirou, I always had the Spirou it gave me ideas. Franquin was my master, I managed to meet him and interview him before his death.

To come back to the past: what interested me, came from the past. To please the ladies, it was great, we did a concert on the Place de la République in '81. We sang the twist, it was the easiest thing to sing, I did not think I was bad in English. We cut our hair and slicked it back. At the time the news was Yes and groups like that, I did not like them, so I stayed stuck in the past. I rediscovered the Early Beatles, which is pure Rock'n'roll, and their premiers on the BBC were crazy, McCartney sings great, as on Long Tall Sally.

My father told me his stories from the war, it was fascinating, the Guérande peninsula. My grandfather Sire was an engineer at the Atlantic shipyards, he made sea tests from Normandy. My father was a great storyteller, where I discovered the childhood of my parents, and my grandparents.

I am also interested in history, of the 1940s among others, where the French social malaise comes from all accounts. The '30s are very interesting, the Speed Twin Triumph, it dates back to the '30s we did not invent anything better. These motorcycles were perfect machineries: we see that when we draw them.

Your drawing stroke is very fine and dynamic, how do you work? I'm crazy, I cut my pencils to 0.5mm on the cutter to have a finesse. They are already thin and I size them more. I can not do that anymore because of my eyes. In my Zybline and Bettie comics, I worked in India ink, extremely fine. It was wash and brush. With Willys Wood, we were influenced by a lot of people, including Americans. With Will Eisner and The Spirit he used the same technique. I met him through Heavy Metal for the first time, with my first print publication.

Willys Wood, this is a reference to the Betty Page pinup? I discovered Betty Page through Jean-Pierre Dionnet and it was a timeless love story. She was also the muse of Dave Stevens.

In your artistic journey, if there was anything to change, what would it be? Better to surround myself. All alone is rather hard, especially since I do not know how to sell myself.

You are edited by Zanpano Editions, is there a comics project at home? No, no comic book, a Volume 3 of Dolls of Sire and then that's it.

Do you work for hire? Yes, I'm currently working with Vincent Marquis on the Continental tire brand, but that's another approach. There are delays, more constraints, and an order remains an order.

Do you work on media other than paper? No, I had proposals for cars, but I don't see too much interest. I want to use perspective, but they want flames: what Alexander Calder did on the BMW LeMans racer was great - it suited the car. Calder it is not figurative and it would be more in that sense that I would work.

Have you ever wanted to re-group a rock band? We would only want to go back on stage. But hey, there was the death of Schultz [of Parabellum], which clipped my wings a little. And then, there is the alcohol, the drugs, and you say to yourself "What am I doing? I do with, or I do without?" When we look at the history of Rock all this is related, it's the same for the bluesmen: they drink, their fingers are messed up, but they're high and continue to play. There is time to consider too, you can not do everything at once; family life, drawing, music, motorcycle. It's a lot. When I was with Dennis Twist, I could not do comic books, because when you draw there is an immersion that has to be done.

It's hard to say. Like that, nothing comes to me. The regrets, they are more connected to the losses of original drawings, from the flights, and there were many. Once in the United States especially, when I worked for Heavy Metal: a poster that I had to fly to New York. I found the original for sale by one of my gallery owners, he had bought in a Comics Convention! Another time, returning from Rome, I lost a whole box on Harley-Davidson, for whom I worked. But that loss is even more stupid, more annoying.

For your Pin-Up drawings do you work with models? I drew the Heavy Metal boss's wife, but it depends.

Today, if we want an original Denis Sire, how do we find one?

There are exhibitions that I do sometimes, but I do not sell live, I do not sell myself either, it is better to go through my publishing house.

What are your available collections?

'Denis Sire' at Nickel Chromium Editions

'The Amazon Island' at Albin Michel

'Bois Willys' by Les Humanoides Associes

[Interview conducted on Dec. 20 2015 by Philippe Pillon for monsieurvintage.com]

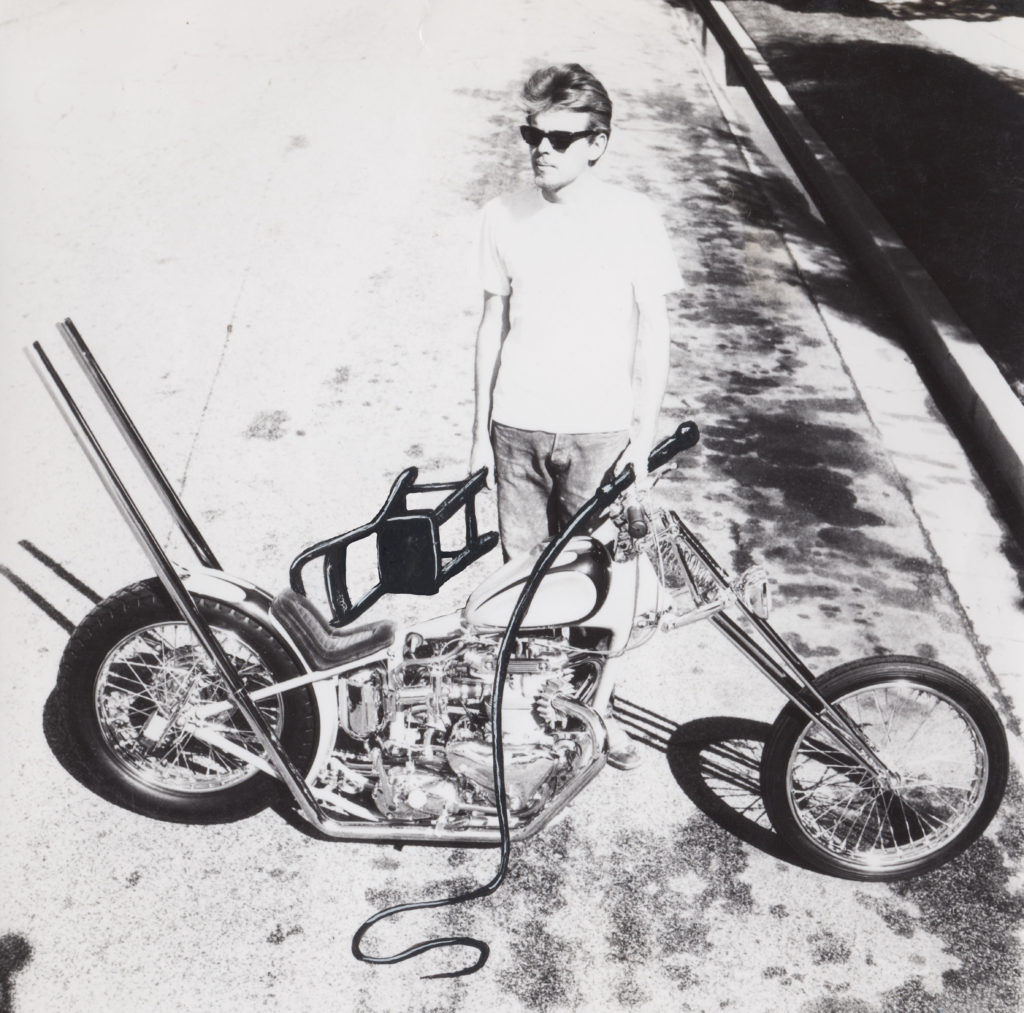

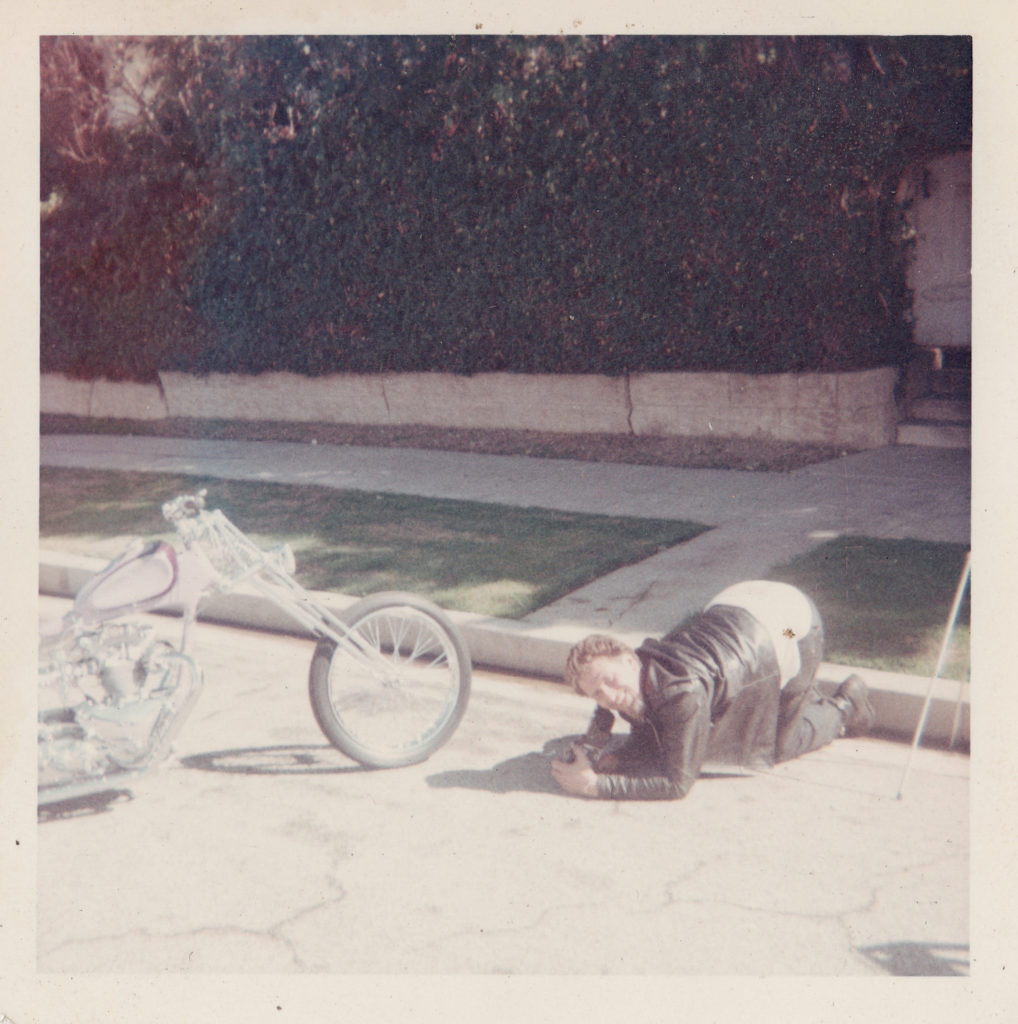

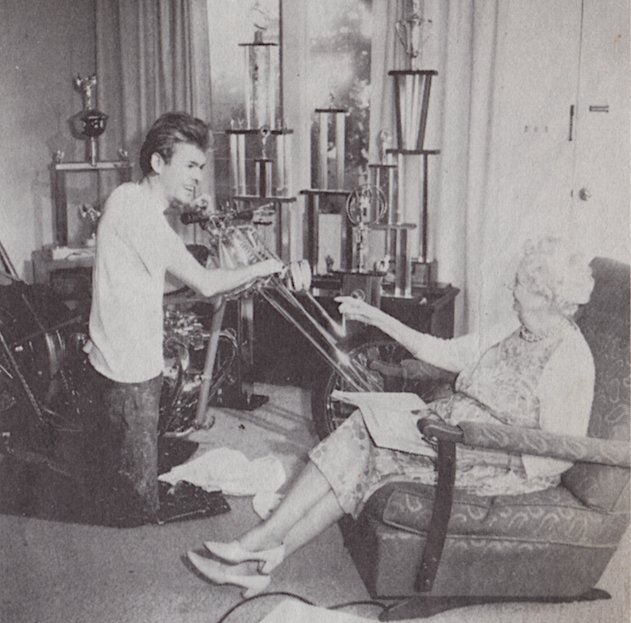

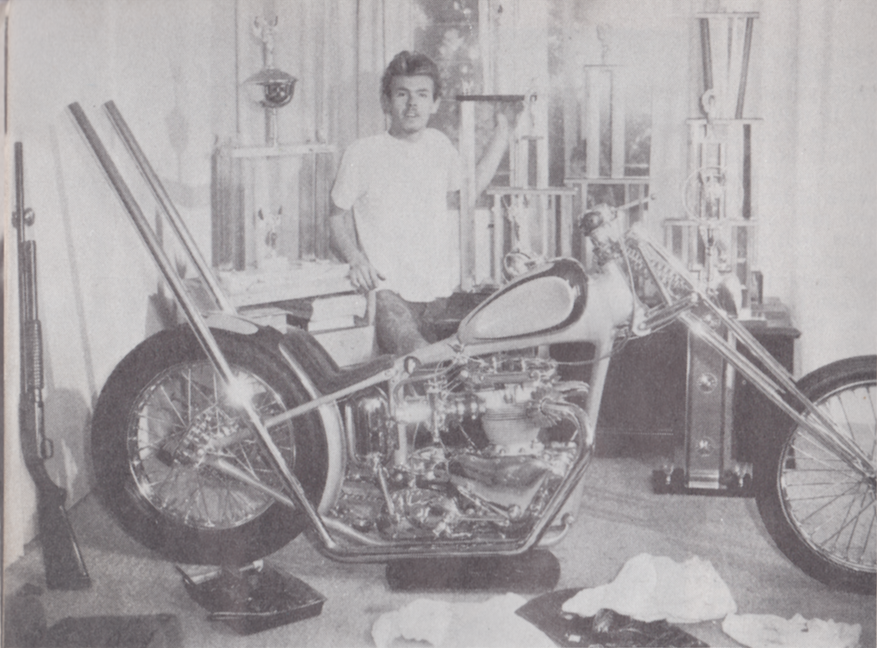

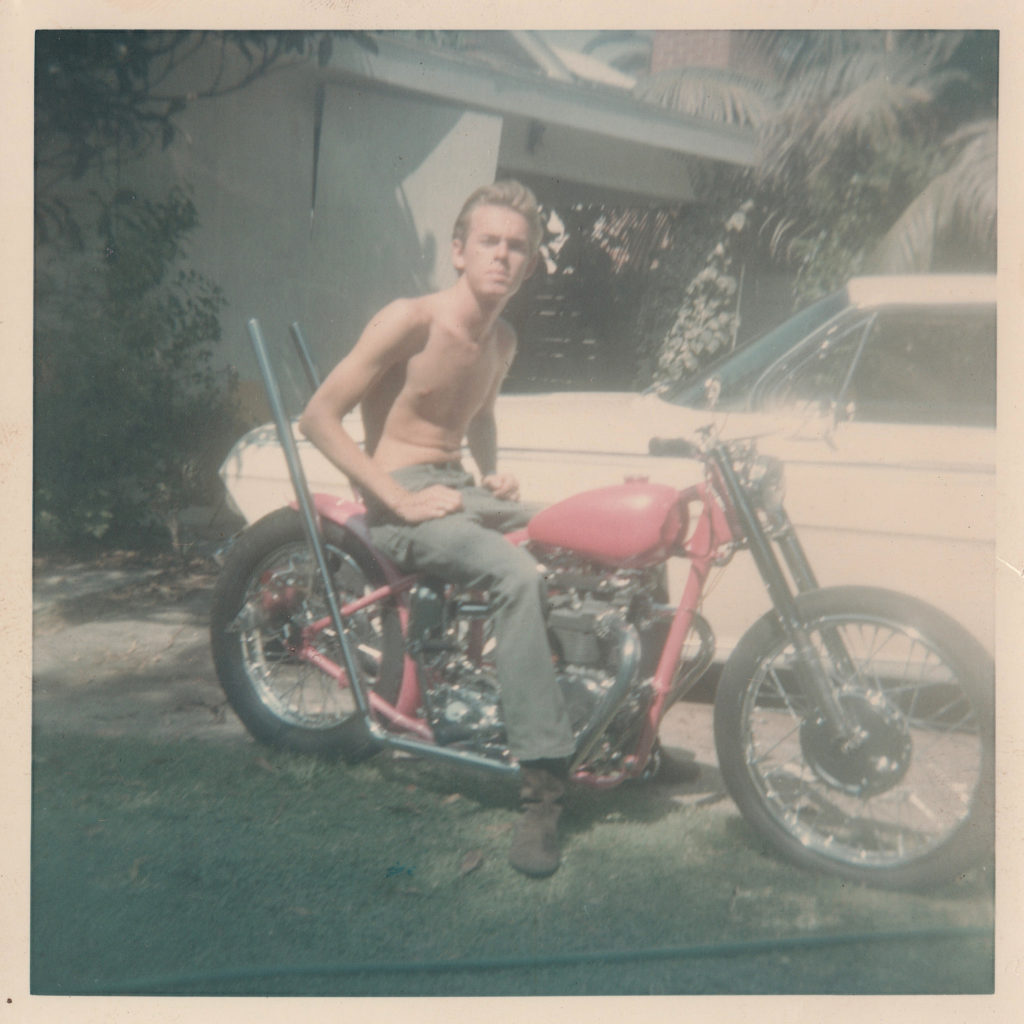

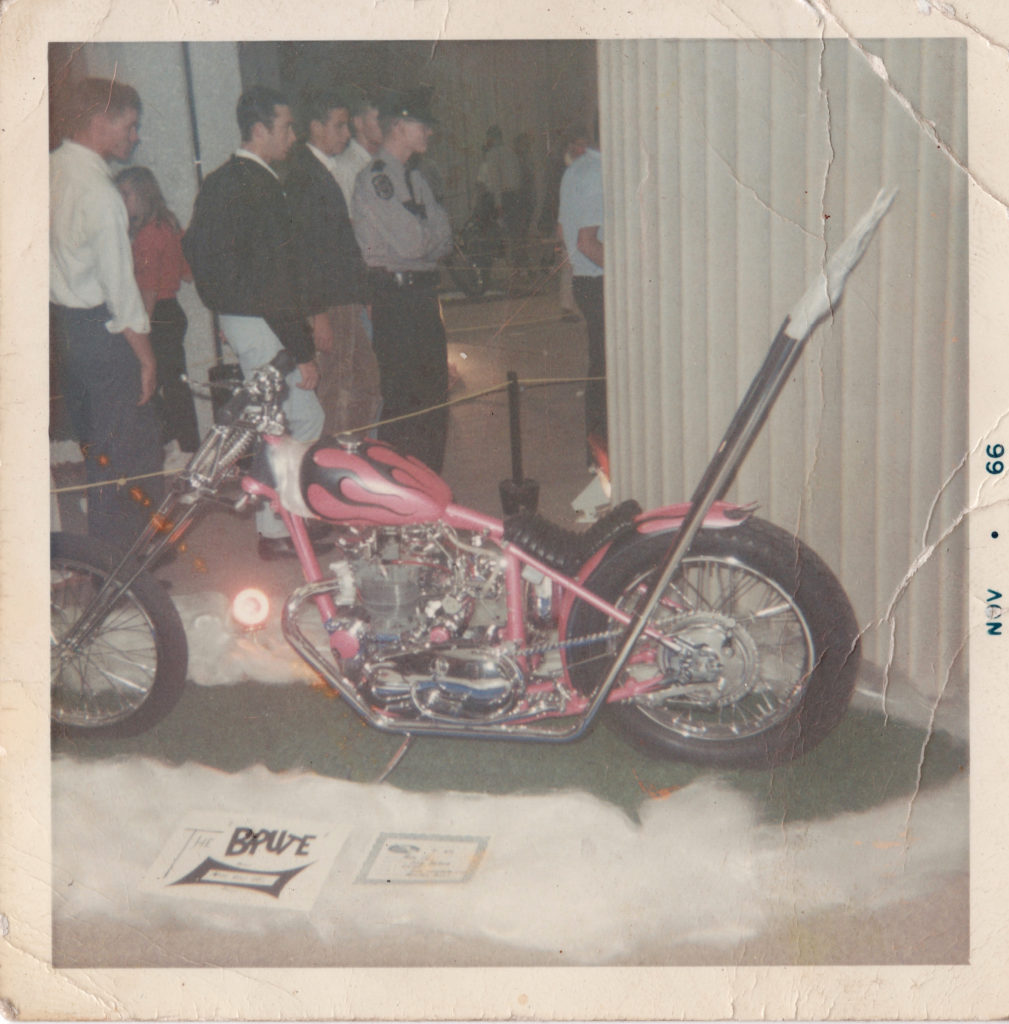

The Brute: 'Fass Mikey' Vils

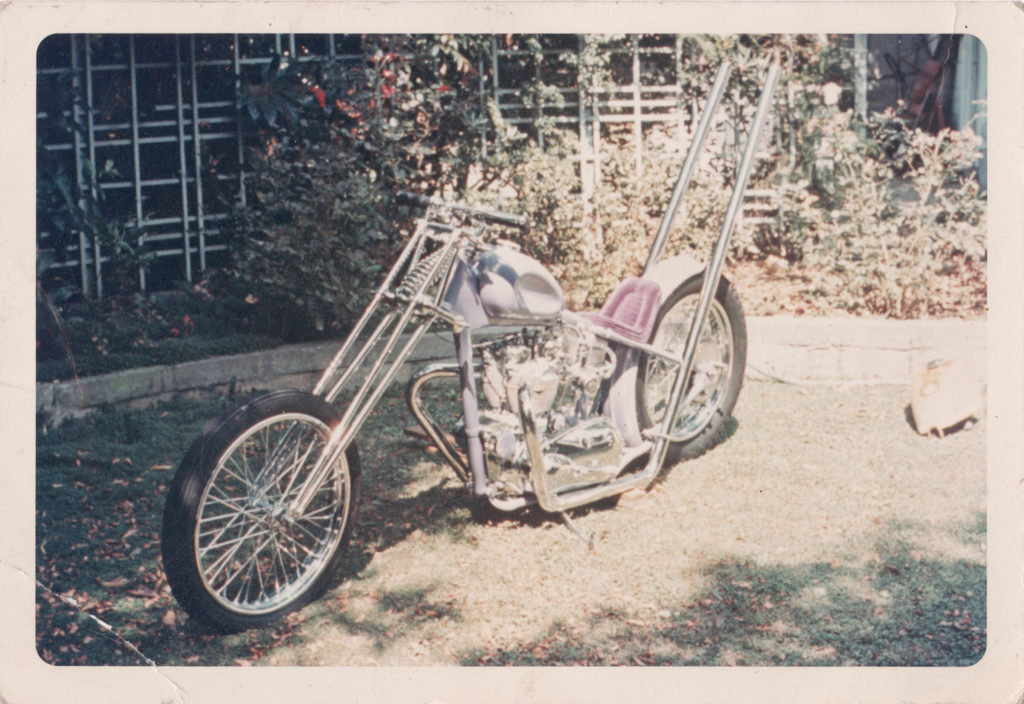

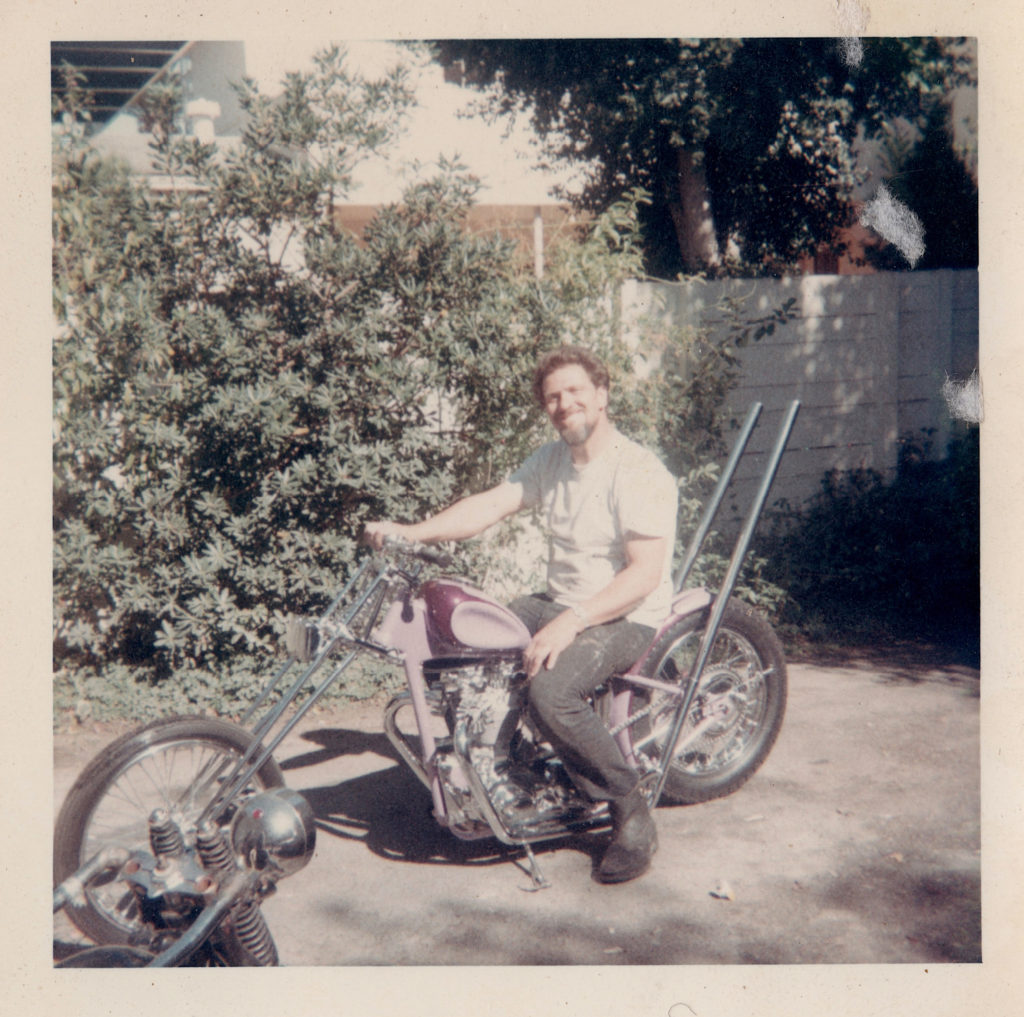

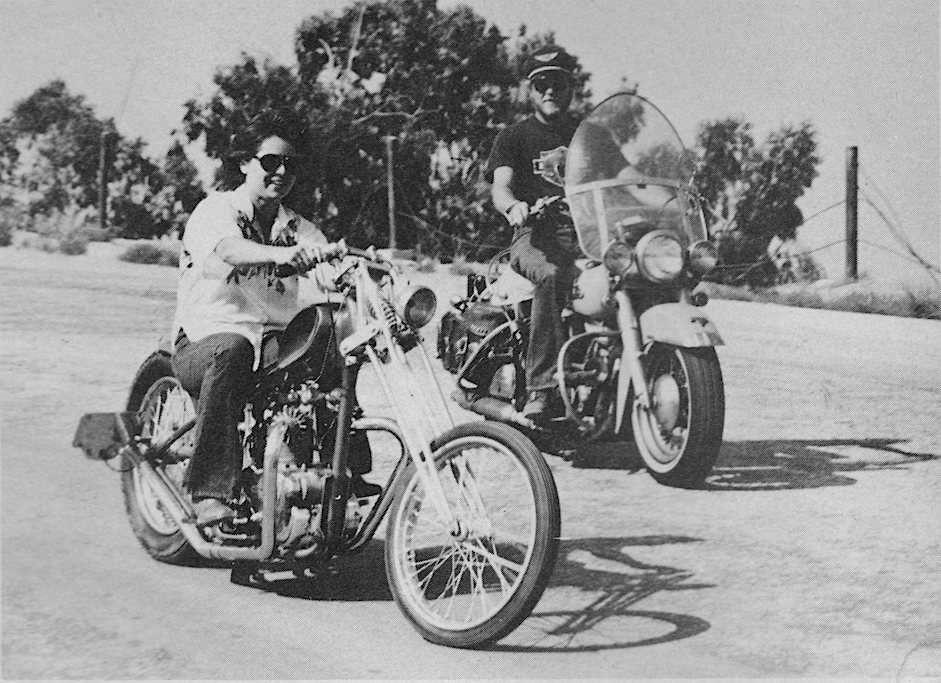

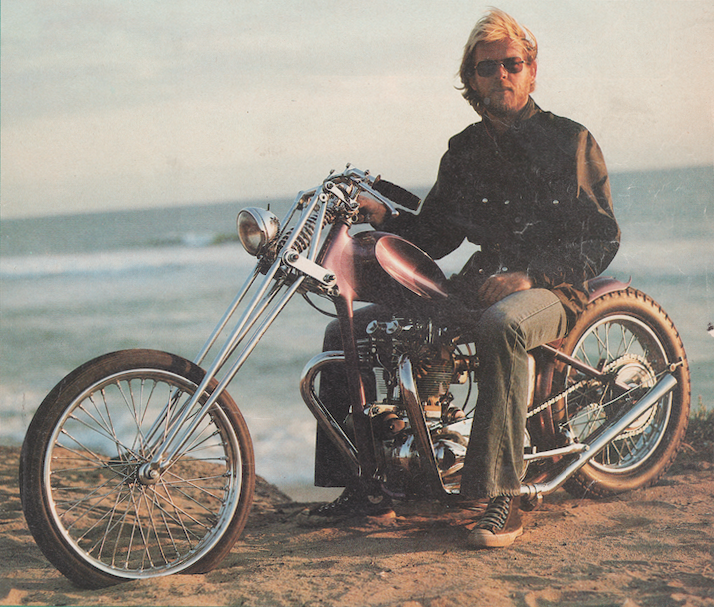

Long before he'd earned the nickname 'Fass Mikey' for his rapid motorcycle painting skills, covering the entire factory Yamaha road-racing team practically overnight in the 1970s, Mike Vils was a legend. He'd been building choppers and show bikes since the early 1960s, and worked at Ed 'Big Daddy' Roth's shop from 1967-69, before branching off on his own, working for Yamaha in the '70s before becoming a building contractor in SoCal.

Hired by Big Daddy

While making the rounds of the hot rod/custom show circuit, Mike met all the characters who also traveled the country showing their vehicles, one of whom was Ed Roth, who was already legendary in the Kustom Kulture scene of the mid-1960s. According to Mike, Roth was a bit fed up with the hot rod scene by then, “Ed got away from cars at that time, as he saw motorcycles were the future, they were going to be a big deal.” Roth began hanging around with members of the Hells Angels like ‘Buzzard’ and ‘Foot’, and even began selling large black-and-white posters of bikers on their choppers at car shows, and via his latest publication, Choppers Magazine, which he started publishing in 1966. Roth saw something refreshing in Mike Vils – a young man with talent, who was creating artistic motorcycles, with no ‘attitude’ or axe to grind. Ed hired Mike Vils, who was “paid $35 a day, and all the cheeseburgers I could eat. I was 6’3” and 135lbs, so I didn’t eat many burgers! There was some cheap and horrible burger place nearby, but you’ll eat anything at 20 years old.”

The Vintagent Archive: Wheels And Wings

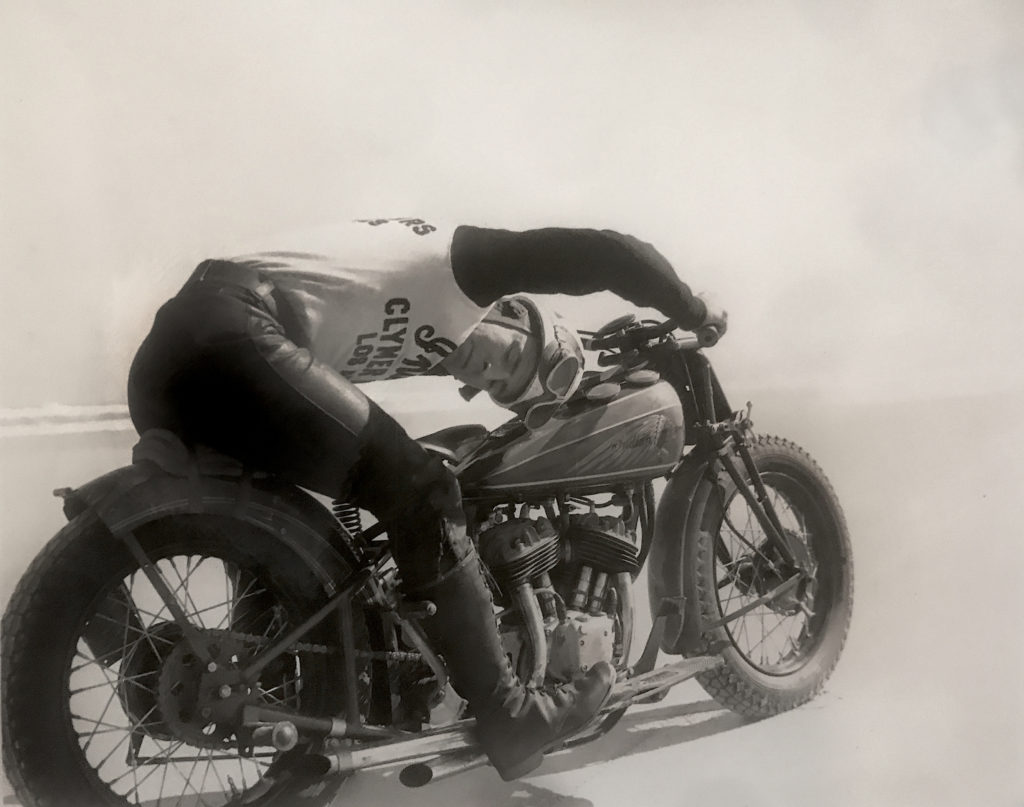

How Speed Work varies on Motor Cycles, in a Car, and in Aeroplanes

[From 'Power and Speed', published by Floyd Clymer, 1944]

By Flt.-LT C.S. Staniland

Chief test pilot, Fairey Aviation Ltd, Motor Cyclist and Racing Driver

I suppose that, before I begin writing about aircraft and motor racing, I had better tell you how I first came to be mixed up in this business of fast moving in the air, on four wheels and on two.

Soon after learning all I could about this Douglas I became the owner of my own machine, a Rudge Multi, looked upon in those days as something very hot indeed. It had a single-cylinder engine, belt drive, and a complicated arrangement whereby moving a lever altered the position of the back-wheel driving sprocket and so altered the gear ratio. The result was that with this device you had a very wide variety of gear ratios, with the option of a high top gear for fast cruising.

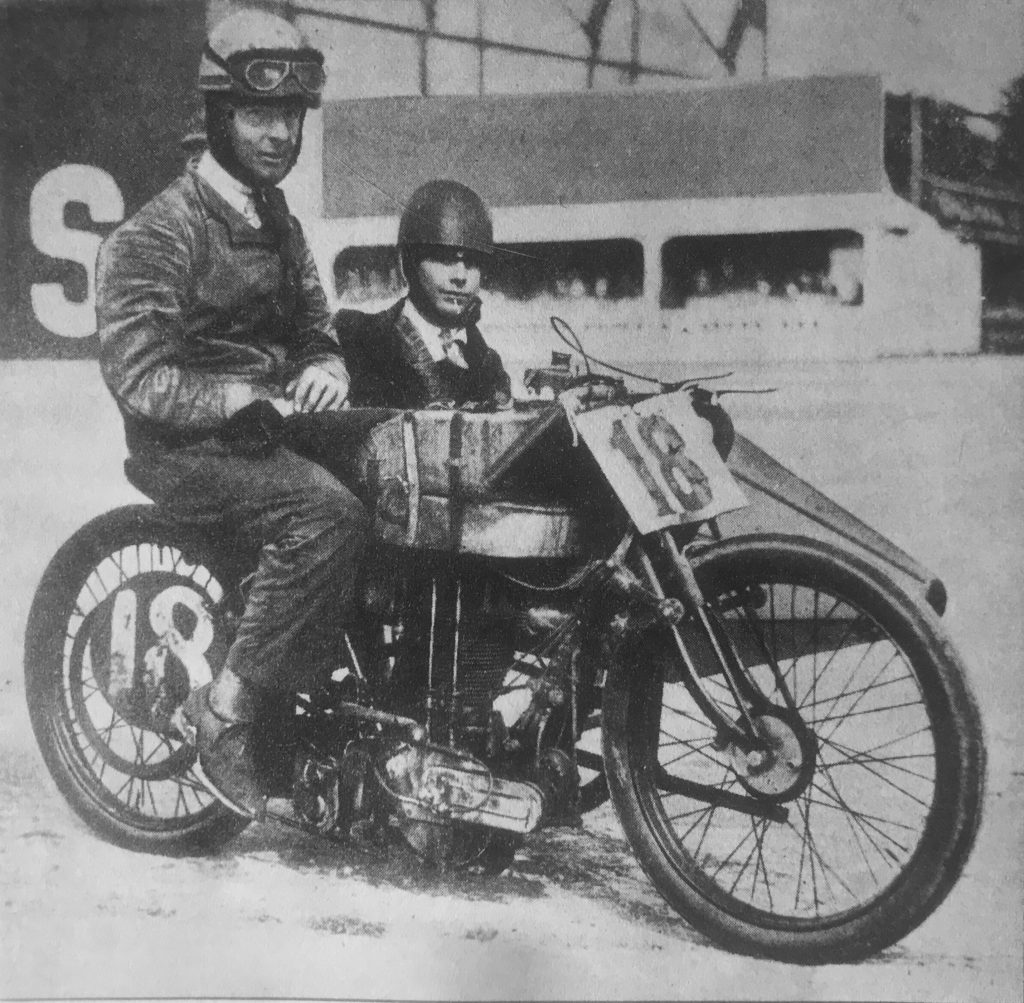

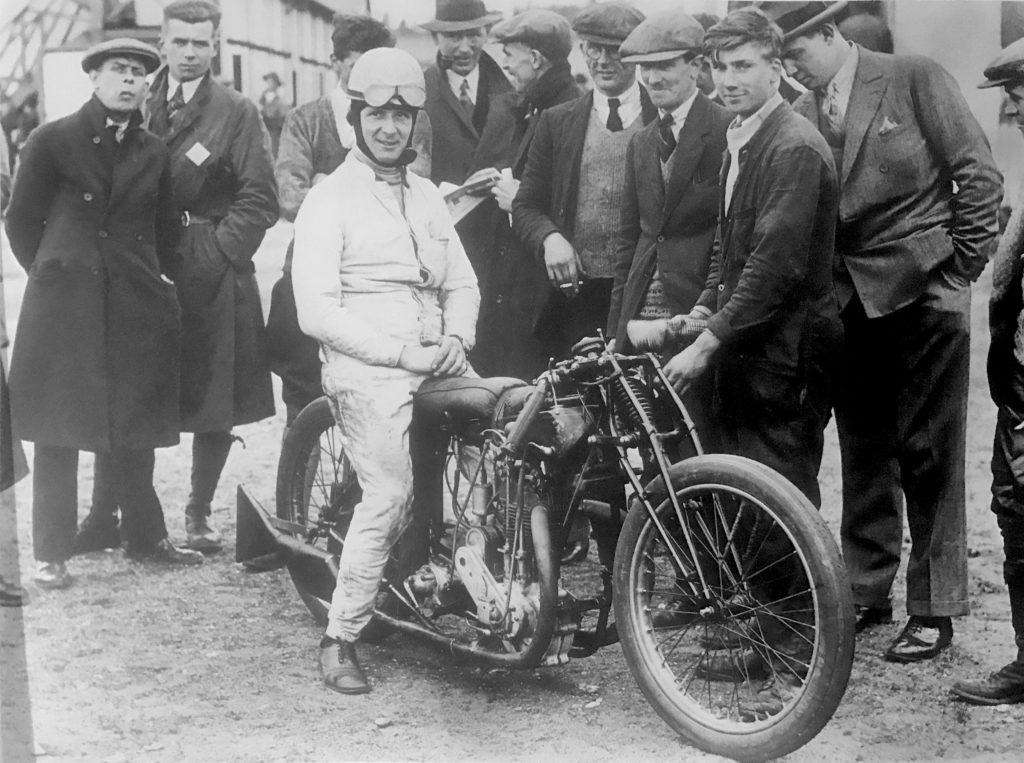

In 1923 I achieved an ambition and raced at Brooklands, and won my first race – a standing start lap at no less than 54mph. I rode Nortons in 1924 and in that year I joined the RAF. During this time I was stationed in Cheshire and raced consistently at Brooklands. Soon after this I began to ride machines for my friend, RM 'Nigel' Spring, and we had rather a successful time in the 500cc and 750cc classes, including the breaking of several records.

Up to this time I had always looked down on the motorcar racing game but I very much admired a Bugatti of George Duller’s, and in 1926 I acquired a 2-liter straight-eight Bugatti of my own, the second of the type imported into this country. With this car I had a shot at car racing at Brooklands and met with a measure of success. Since then I have raced motorcycles (not so much on the two-wheelers this last year or so, for various reasons) and all sorts and shapes and sizes of racing cars.

As you may know I was a member of the Schneider Trophy team in 1928-29, and then, leaving the Royal Air Force, I became test pilot for the Fairey Aviation Company, the famous aircraft concern.

In both forms of sport there is the same need for perfect judgement of speed, the same gentle touch for braking and the same benefits from experience. A motorcycle has to be ridden – there is no question of a machine keeping itself up owing to its speed. Riding a motorcycle at great speed calls for the utmost physical fitness. When you see a motor cyclist flying down a bumpy road at over 100mph it keeps upright by reason of the skill, courage, and experience of the rider and for no other reason.

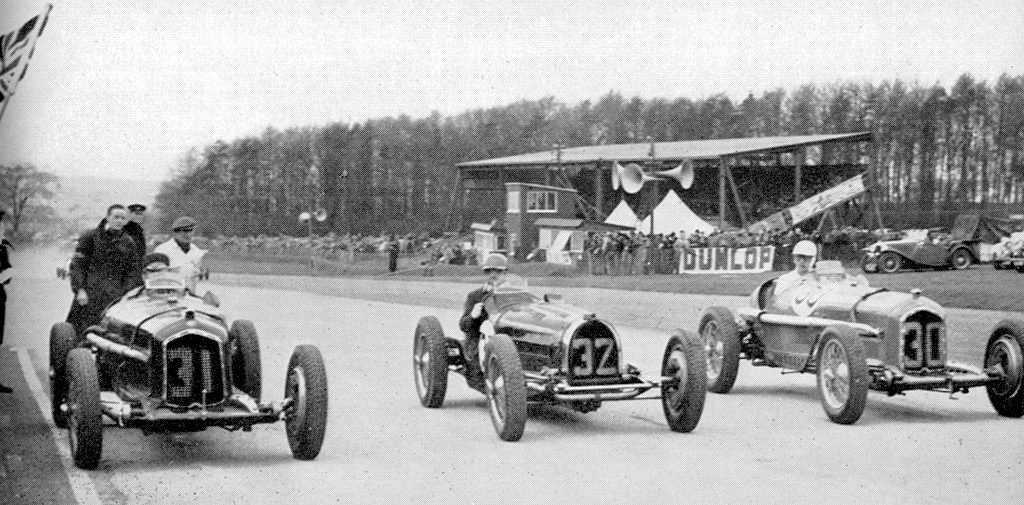

The fastest cars are faster than the best motorcycles. The power to weight ratio is about the same in both, but the car has better streamlining. A road-racing motorcycle will weigh about 350lb and will develop about 50 brake horse-power. A Grand Prix car of the 1937 type weighed about 18cwt and gave off about 500bhp. The car has better road holding, better suspension, better braking and greater inherent stability, which all tends to make the car faster on the road. On road circuits where cars and motorcycles both race at various times, the cars have proved the faster, by as much as 10mph on the lap speed.

The motorcycle record for the standing start kilometre is 98.9mph whereas the car record for this distance is 117.3mph [this is 1938... ed.].

Racing motorcycles will develop as much as 120 or 150 horse-power per 1000cc of engine size, but the latest Grand Prix cars will exceed this. Most racing cars have supercharged engines, producing astonishing power from small units by this means, but supercharging has not yet caught on in the motorcycle world owing to special problems of carburetion, added to which although a supercharger can be mounted on a motorcycle quite neatly, it absorbs some power in the drive and the extra power produced seems offset by the power used up in the driving.

The carburetion problems of aircraft are far more complex than either in a car or a motorcycle. A car operates always at about the same barometric pressure, so that carburetors can be tuned with precision for every given racing circuit and left at that for the race. An aeroplane needs carburation for varying barometric pressures and for varying temperatures according to the height at which the aeroplane is flying, added to which the carburetion must be right for all weathers, including frosty conditions. An aeroplane starts off from sea level and is called upon for maximum speed at say, 20,000ft, where the weight of air drawn into the cylinders is far less than on the ground. Every tourist knows how his motor car loses power in climbing a high Alpine pass of perhaps 6000ft, owing to the fall in barometric pressure which allows the mixture to become too rich. An aeroplane at 20,000ft would in the same way have a hopelessly over-rich mixture and would lose a great deal of power at what is its usual service altitude.

Aero engines resemble car engines in all essentials, but are much more expensively made, with the finest procurable materials, the best labour and with exhaustive tests, which all send up the price. A racing car engine is tuned much nearer to breaking point than an aero engine, and after one race has lost its fine edge of tune and has to be inspected and perhaps reconditioned. Thus after a Grand Prix, the German cars are sent back to the works for inspection and re-tuning, while a different team of cars is sent out to the next race. An aero engine, on the other hand, must be capable of giving off its full power for very long periods with only routine maintenance – checking of valve clearances, plugs, filters, and so forth.

Speed on two wheels feels colossal. A car feels slower at 100mph than a motor-bicycle at that speed owing to the rider of the latter being exposed to the wind and being much closer to the ground flashing away under him.

But 100mph in a car feels far more exciting than an aeroplane at 300mph – and many RAF aeroplanes will do far more than that flying straight and level. It is extraordinary how, after flying at high speed and the pilot comes in to land at 80mph, the machine appears to be crawling. Reduction from high speed to low velocities is always deceptive, as one mechanic found out at Brooklands when his driver slowed down to 30mph and the unfortunate man stepped out under the firm impression that the car had nearly stopped.

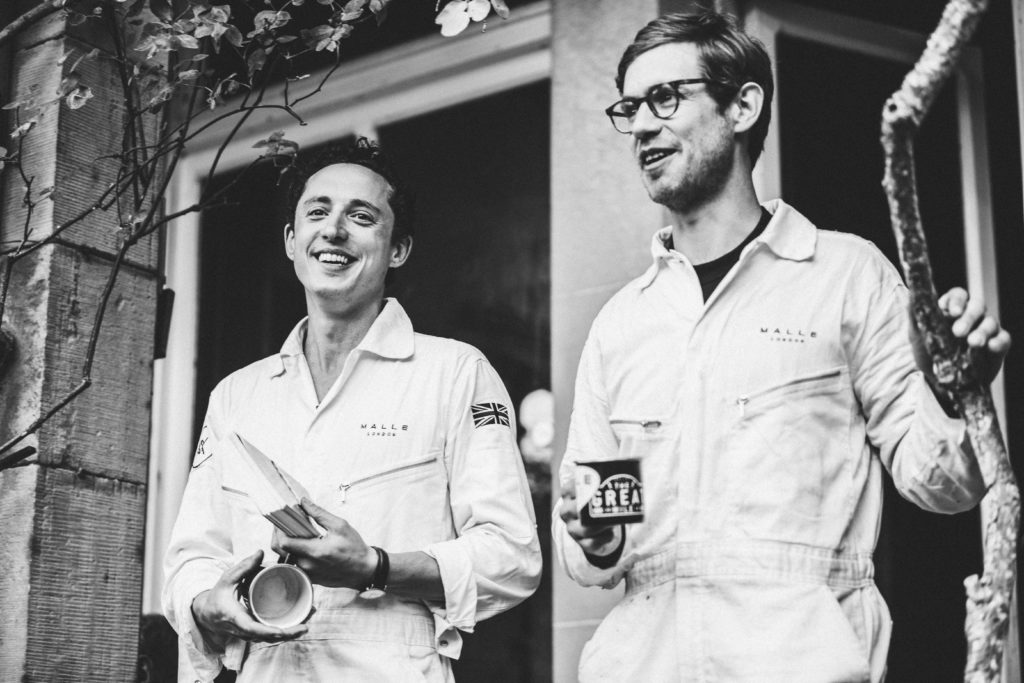

The Great Mile Rally 2018

NAME, COUNTRY, NUMBER AND WHAT ARE YOU RIDING IN THE RALLY?

Robert Nightingale, England, Rally Number #57. Against the advice of many, I decided to ride my late-fathers 1957 custom Triumph Thunderbird, which I got working earlier this year and it turned out to be the oldest motorcycle in the 2018 rally.

IS THIS THE FIRST TIME YOU’VE ENTERED THE RALLY?

Over the last 3 years I’ve helped the Malle team research the rally route, normally from the back of a support vehicle, but this was my first time riding in the rally with a team: a completely different experience!

TELL US ABOUT YOUR RALLY PREPARATION?

The day before the rally, like most of the riders I was scrambling to complete the bike in time, finding last minute spare parts that might break or rattle off. On the forecourt of The Classic Car Club in London, bits of the Thunderbird were littered around the bike, while more and more custom/classic rally bikes were being dropped off every hour, which only added more pressure to the impending deadline. I managed to fit a new oil-feed pipe, “new” custom California handlebars, bent the mud-guards out a bit to accommodate the larger off-road trials tyres, fitted race plates and gave it a fresh oil change. After a quick lap around the backstreets of Shoreditch past the BikeShed to test the brakes and the oil flow - the bike was pretty much ready to go.

First thing the next morning we helped the professionals load the bikes into crates at The Classic Car Club and onto the rally trucks. Strapped in tight, for the long and slow journey up to the Castle of Mey, located at the very Northern tip of mainland Britain. It was a bit sad seeing my old bike leave for Scotland without me, like sending away the family dog and watching it stare at you out of the rear-window as it was driven away and out of sight.

The boys at Ace Classics helped me fill my tool roll with some more extras (seals, plugs, strange bolts, more cables, levers etc.) and advised me to take it real easy if the bike was to survive the rally - to ideally ride on alternate days, giving the old bike a rest day between stages... which was definitely the plan.

WHAT HAPPENS AT THE START LINE?

After 24 hours of driving North from London we finally reached the top of the country in the support vehicles and set up in the rally camp at the Northern tip. Overlooking the North Sea from the Castle of Mey, with the glow of the oil refineries on the horizon behind the islands of Stroma and Orkney, seals playing in the bay beneath camp. Up there the coast line is pretty harsh and jagged, with few buildings on the land, the weather can do a full 180 in minutes, turning from sunshine to blizzard.

The team from the Nomadic Kitchen (Tom & Will) arrived that afternoon, after riding a pair of borrowed Royal Enfield Himalayans 800 miles straight up from London. As soon as they unloaded, they got out their knives, lit the fires and started prepping the first night's wild cooking feast - fire roasted pork loin and mouth-watering roasted salads. The 70+ riders descended on the Castle of Mey from all over the world (mainly Europe) for the Riders Check-In that afternoon.

After all riders had checked in, with fresh rally numbers on each machine, we left the castle as a pack. Lead by Jim the head groundskeeper at the castle on his old BMW (after a quick change from his kilt to riding leathers). We rode 5 miles along the coast up to the lighthouse, perched on a slab of rock 250m above the lashing sea. 70 completely unique classic/cafe/custom motorcycles made up the pack, as we snaked back and forth up the hill to the lighthouse. I turned to see all the bikes behind me meandering up the hill in single file, moving as one continuous line, the headlamps lighting up the hill in the dusk - it was a beautiful sight. We road back along the coast and the local villagers had come out of their house to wave the rally past, very sweet. The feeling that the rally was about to begin was building.

Back at camp, we had the first and most detailed riders briefing, describing the next day's route, with riders from last year's rally joining in with local tips on the route and their thoughts on the rally experience and team riding. The briefing was followed by the now customary whiskey pairing; local single-malt with locally caught/smoked salmon. After three attempts at a synchronized toast, there was a cheer, a gulp of whiskey and it was back to the bikes.

WHAT HAPPENED ON THE FIRST DAY IN STAGE 1?

I don’t know if Tom and Will from the Nomadic Kitchen made it to bed that night, I woke at 5am and they were slaving away over the fire, knocking out a hearty wild cooked breakfast for everyone. Rally mornings are always the most rushed and the first day was the most chaotic, bikes and kit everywhere - riders running from tents to bikes, half dressed in leathers, toothbrush in one hand, with a coffee and spanner in the other, trying to find some odd component that they were sure they packed. We had a quick briefing with the rally marshals at 6am, minutes later they tore off on bikes, which in that moment felt like we were about to play the largest game of hide and seek in the land. With a 2-hour head start, the marshals went ahead to set up check-points and report back of any route problems. We threw our rally duffels into the support vehicles and headed to the start-line at the Castle. Luck was already on our side, not a cloud in the sky and it was beautifully warm: when Scotland is good, it’s bloody great!

With all the planning in the world, some things you can’t predict. After half of the bikes and I had reached the start line, with not a soul in sight, a local farmer (not realizing there was another 40 bikes behind us) closed the in-road with a JCB, acting as a blockade for his cows. As we soon learned, the “Royal Cows” take priority, and the big herd ran boisterously down the castle track - you don’t want to put a motorcycle in the way of that stampede.

Minutes later, everyone was assembled in front of the castle, which was the first time some of the teams had really met each other. Log books out, stamped, the flag dropped - and the rally had begun. Teams departed in 5-minute intervals. My plan was to ride out as soon as the last team had left and catch up with them. Second hitch of the morning, a modern street-scrambler suddenly wouldn’t start. Calum from deBolex Engineering who heads up the engineering team can fix anything. He got the King-Dick tool chest out, with jump leads, meters...and found a serious charging issue.

My team departed an hour or so behind schedule, but it felt so good to finally be out on the road, after the months of planning, logistics and comms, we were in it. I was riding with Team #7: two couples on a mix of modern Triumphs and Bobbers. We barely saw another vehicle for the first few hours of the day, hugging the coastline that rises and twists along the hilly coast, one of the best parts of the North Coast 500 route. The Thunderbird was pulling strong and running like clockwork, we made great time: across the Tongue Bridge, through checkpoint #2, on to checkpoint #3 - stage 1 was pretty easy going. We only needed to turn right about twice, the rest the of the day was following one gorgeous yet tiny B-road down the entire Western side of the Scottish Highlands, through truly wild countryside. In places the sea was a turquoise blue, if it wasn’t for the fact that you were in Scotland, the white sand beaches could be in the Caribbean. By the 4th checkpoint we had caught up with a few more teams and met up with the BMW Motorrad team, lead by Ralf and Lucas with photographer Amy Shore [whose photos illustrate this story - ed] who was documenting the rally. That day Amy was flying along in a vintage Mini with the top down, shooting riders out of the back with her cameras.

Faster than we realized, the 7-hour ride was ending and the signs for Torridon started to appear. As we came across the small pass from Kinlockewe, reached Loch Torridon, and rode along it until we found the rally camp at the grand Torridon Estate. I kept an eye on the edge of the loch as we rode: the last time we were up here on a research trip, we spent an hour watching a family of otters fishing for trout along the bank. Torridon did not disappoint, the estate is run by a wonderful Scottish/German couple that served up ‘Tartan Tapas’ with local scallops and fish from the sealoch. After the rally briefing and the whiskey pairing, the instruments were out, Scottish music started and somehow ended up in an impromptu Highland Games. After we were thrashed at a Tug of War... I turned to something I was slightly better at, bike tinkering. The bike seemed to be doing well, it was keeping up with the modern BMW’s and she was in her element on these tiny twisty roads, much lighter than most modern bikes I’ve ridden, it’s quite easy to steer the nimble bike with your knees, keeping the bars straight and pushing the back end around corners.

WHAT WAS THE RIDING LIKE IN SCOTLAND ON STAGE 2?

On day #2 of Scotland we had an early start, and after a Scottish breakfast served amongst the trees, the morning rally ritual of oil/coffee/briefing - with the marshal-dash and then pack / suit up - ready for the day. Suddenly the midges decided to make an appearance, within minutes riders may not have had their jackets on, but most of us had helmets on with visors down - midges are a hellish event - this sped up our departure, log-books stamped, flag down - off we rode. Another gorgeous day of sunshine as we headed straight over to the highest pass in Scotland and the steepest legal road in the UK, for the AppleCross pass. The roads around there are beautifully smooth and seem to have been laid out by a roller-coaster engineer, with a good sense of humour, twisting up and down over endless hills, perfect.

First engineering hiccup of the day - Ravi’s Moto Guzzi had arrived at Checkpoint #2 at the start of the pass and then decided to throw up all over the road. A big black pool of fresh oil beneath the bike - a leaky hose or a faulty clip. After 30 minutes of fettling, our new friends in the BMW team arrived. He looked at the hose and said “I’ve got just ze thing”, we thought he was going to come back with a brochure for a modern BMW, but came back with some very smart white plastic gloves, tools and spare hoses. Ten minutes later, both teams were back on the road, and what a road the AppleCross pass is. Getting to the top is one thing, but the view down into the valley with the Isle of Skye in the distance is amazing. The road boasts a dozen hair-pin bends as it progresses down the valley - as soon as I reached the bottom I just wanted to ride back up and do it all again. But there were more mountain passes to come.

Stage 2 was definitely a longer day, about 8 hours or riding in total. We arrived at Checkpoint #3 at the start of Glencoe - the Great Glen. A breath-taking ride through that monstrous valley, imposing mountains on every side, the stags were grazing up on the heather/granite foothills - you’re riding through a whiskey advert! As we came to Checkpoint #4, I parked the bike up and something smelled bad. With an old bike, there’s no warning light if something’s starting to go wrong, you have to use all of your senses, touch, listen and in this case smell the motorcycle - normally the bike has a gorgeous hot-oil aroma to it - something didn’t smell right.

We carried on the ride through Loch Llomand and the Trossachs and down the coast to the extremely bizarre and beautiful Kelburn castle where our rally camp was based for the night (the Castle was painted by a group of Brazilian street artists). As I turned up the drive to the castle, I wasn’t getting as much power as I normally would, or was it just my imagination, when you’ve been riding all day, 280+ miles, you’re tired and your mind can play tricks on you, maybe it’s me not the bike? The Nomadic Kitchen team were already at the fire when we arrived, roasting butterfly lamb. Dinner that night was a well lubricated affair, after a walk around the grounds of the castle, back at camp we were greeted by a fantastic sunset over the bay.

Calum and I had a look over the bike and realised the throttle was misbehaving, sticking slightly...but nothing major it seemed., nothing to explain the smell or the power loss. At this point I should probably have taken that pre-rally advice and maybe given the bike a days rest.

TELL US ABOUT STAGE 3 IN THE LAKE DISTRICT?

Another early start and the good weather was still on our side. I knew this was going to be a long day, 300+ miles on the route card. I joined the last team to leave who were enjoying a leisurely start, but then it appeared that the old Police issue Moto Guzzi had snapped an alternator belt, after some quick calling around, we located a shop 20 miles down the road where we might get one. Our team headed out on a brief detour to source belts and parts, adding an hour off course. After we crossed the border and left Scotland for the lake district, we were happily cruising for a few hours as a team, when I felt power suddenly drop on the Thunderbird. I limped along to the next turning, 2 Minutes down a country lane, I found a safe spot to park up, for some reason the bike was only getting full power when in high or low revs, but nothing in the middle. I searched the electrics, then got word that the support vehicle was only 5 minutes away, we looked over the bike, stripped the carb, gave it a clean and then the bike seemed to be running fine, strange.

I caught up with my team at Checkpoint #3 and we rode as a team down in to the Lake District, across the 2 highest mountain passes in the Lakes - from Buttermere across the Hardknot pass. The Thunderbird was back in her element, throwing it from side to side up the mountain roads. The sun was shining, a fantastic afternoon of riding over the passes and along the lakes, dodging stray sheep, cows and tractors.

Unbeknown to us, late that afternoon a lorry driver had fallen asleep on the M6, knocking out an entire motorway bridge, he was completely fine, but it shut down the motorway for 24 hours (the local newspaper the next morning called him the most unpopular man in Lancashire). Which meant that all that traffic spilled onto every other nearby route, bumper to bumper traffic for 50 miles in every direction - exactly in the area we were all trying to ride through. Luckily we were on bikes and could filter through the bad patches. We should have been back at camp by 6pm, but arrived starving at around 9pm, at the very quirky and eccentric Heskin Hall. Our support crew weren’t quite as lucky, the Malle-Rover turned up at the Manor gates just after midnight, with a Commando in the back (the Norton had fallen off it’s centre stand and snapped a vital lever).

WHAT WERE THE HIGHLIGHTS OF STAGE 4 IN WALES?

By day 4 you could start to feel the toll of 3 solid days of riding, 750ish miles, 2 countries behind us as we crossed over into Wales. I started that day with the BMW Motorrad team, and the thunderclouds threatened to break. A couple of times we stopped, threw on wet weather gear, but most patches were just light showers, so we rode as a pack through the winding tracks of Snowdonia National Park, down the infamous A470 (voted the most beautiful road in the country) around the back of Mt Snowdon and down through the valley. By Checkpoint #3 we were joined by another team with a very fast Triumph Thruxton leading. To keep up with them I really had to press my chin on the tank, tuck elbows in and try to get another 10mph out of the bike. Somewhere in Snowdonia my key must have rattled out, so I borrowed a small teaspoon from the cafe which did the trick of starting the bike. The weather held but as we left the Brecon Beacons the wind picked up, bringing with it the energy you feel before storms. Riding with 3 teams now, 12 or so bikes together, we crossed the Severn bridge at a furious rate. Riding in all 3 lanes, I’m not sure if we were actually going that fast, or if it was the head on wind that was bashing the bikes about as we rode across the huge suspension bridge - quite a departure from the quiet tracks of the Scottish highlands, but riding in a fast pack like that is so much fun. I think the BMWs were politely humouring my attempt at keeping up the pace, through my wildly vibrating side mirror I could just make out the image of Jochen grinning and riding along side-saddle on his cafe-racer BMW and then occasionally wheelying past me. I didn’t think being overtaken would be a highlight...but it was a great memory of that stage.

We were chasing each other down the lanes of the Mendip Hills, when the welcome sight of 2 rally flags appeared up ahead. The guys from Sinroja motorcycles led the Marshal team that day and waved us in smiling. The landscape was completely different around there, the camp was perched on top of the Cheddar Gorge on a large flat plain, with gorges surrounding the area on 3 sides. Word spread that night that there was a full lunar eclipse, with a blood moon - unfortunately the storm clouds had descended on the dark camp, so instead we hosted a motorcycle race.

The boys wheeled out the Mini Malle Moto, a half-thrashed monkey bike from The Malle Mile. I pushed the Thunderbird out into the the long grass a hundred meters away, and the support vehicles turned on full beams to light up the “track”. One at a time every rider and Marshall took a timed lap around the marker-bike and back, 10% didn’t make it across the start-line and then the Belgian rally team proved that it was actually faster to run the route by foot and beat the monkey bike. After the race finished and the winners were awarded a cold beer, I was walking the Thunderbird back across to camp and realised the tank badges must have rattled off somewhere in Wales. Steadily it seemed, I was leaving bits of the Triumph on roadsides up and down the country.

HOW WAS THE FINAL STRETCH TO THE FINISH LINE?

The last day of the rally was supposed to be the shortest day, but the motorcycle gods had other plans....We woke to good news that the storm hadn’t broken yet, but big dark clouds hung menacingly on the horizon, full of water. I guess on the last stage of the rally, you need a little drama - you don’t want everything to be too easy. For the last day we had arranged for the press-marshal Rachel Billings - who was writing about the rally - to ride with our team to shoot 35mm film from my bike....slight problem... the bike wouldn’t start. After 30 minutes of tinkering and some kind words whispered to the bike, she suddenly roared into life. By that time all of the teams were now 30 minutes ahead of us. We jumped on and headed down into the Gorge, ok it’s not the Grand Canyon, but its a great ride. In the rough words of Bill Bryson “England doesn’t have the biggest or the highest or the deepest of anything, but it does a lot with what it’s got” and the county here is unique, varied and pretty. Tiny postcard towns and castles connect the dots all the way from Wales to Devon and on to Cornwall.

En route to Exmoor, it poured with rain, black skies above, the sort of downpour where immediately there are deep pools of water on the lanes, mini rivers at the sides. Somehow water gets into your boots, soaks your socks and you hunch your shoulders and neck to try and close any gaps between helmet and jacket and soldier on. I remember shouting to Rachel “shall we take shelter” as we sped through the driving rain, but she shouted back “just keep going” - she’s got grit! The rain was relentless, but then the rain ended and there was a faint hint of blue sky up ahead, things were looking up...and then bike died. We rolled to a silent stop in an old school house drive. Out with the tools, so much for Rachel’s rally team photos which was the photo-brief for the day. I was pretty sure we were miles behind the other teams. By sheer coincidence Calum and the support Land Rover drove by only 10 minutes later, we went over the obvious things, then took out the battery, only to discover that the 2 new lithium batteries had fused together in some horrible hot-molten-mess. The bike might be out of the rally and only 150 miles from the finish line.

Luckily we weren’t in the wilds of Mongolia: it was midday on a Saturday in England, so we called all the local bike garages to find a classic 6V battery. After 10 no-goes we find a shop on our route that thinks they has one in stock, so we stuck the bike in the trailer while four of the rally teams roared past us, beeping. So we weren’t last after all at that stage. We found the old motorcycle shop, owned by a young guy who specializes in vintage Japanese imports from the 1980s...quite niche, but he had the battery! £6.50 later it was installed, the sun shone and we were back on track. We headed for checkpoint #2, still in the running and things look good. As we reached Exmoor, the landscape changed completely to a wild open moor, with animals running across the roads. We crossed the top and the bike seemed to be struggling again, fine in high revs, but no power below max revs, it coughed, spluttering...and then just the sound of air rushing past, as the bike free-wheeled in neutral down a very long hill into the deepest valley in Exmoor. We rolled to a silent stop outside an old garage that looked closed for decades. No network connection, Rachel walked up the valley, still nothing, I started going over the bike, no joy, the battery was completely dead.

After 20 minutes or so a little voice popped up from the hedge behind the garage “need some ‘elp?”. A small older gentleman, in a blue baseball cap came through the gate smiling. I explain the bike problem, the man in his late 70’s, tells us he used to get a lot of these bikes here back in the day and he owned a similar model once. He rubbed his big mechanics hands over the engine and said “Well let’s try and fix it”. He heaved open the sliding doors of the ancient petrol station, and I noticed the faded paint on the inside walls of ‘The Black Cat Garage’. Inside he had a load of old bike parts, some possibly working, some hanging from the ceiling, but he had a workbench of old tools - this might be the best place we could have broken down in the whole of England! He had an industrial battery charger, but after no success with the old 6V, Fred says “I have an idea”, pulling a battery out of an old scooter. “This might work” - it still has charge. We put it next to the Thunderbird and with makeshift copper wiring we hooked it up. The Thunderbird kicked over first time! Fred wouldn’t accept a penny for the battery, we wrangle it into the battery box on its end, holding it in place with gaffa tape. We thanked him again, loaded up and headed off down the green tree-lined tunnels of Exmoor - and the rain had stopped.

To make it up to Rachel for that last 5 hours of riding in the rain, 3 dead batteries, 2 garages, 4 pairs of soaking gloves, I suggested we stop in Dartmoor for a quick bite to warm up. We rode in to the oldest pub on Dartmoor, where a wedding was going on in the back of the pub. The bride walked out in head-to-toe white lace, looking radiant, while I was dressed head to toe in Black waxed canvas, covered in black oil and dirt, hungry and looking angry. “I think we’re complete opposites” I mentioned. We went to start the bike, nothing, silence. The rain started spitting, I reluctantly called the support vehicle, Calum’s 2 hours South almost in Cornwall. A rowdy group of young male wedding guests came out of the back of the pub, half cut, they all had an opinion on how to start the bike. Moments later they’re taking turns to help me push the Triumph to the top of the hill, across the bridge and bump starting me across the river. On the 15th go, it roared back to life, they cheer, Rachel downs the last of her drink and we’re back in the game.

A few hours later as we crossed into Cornwall, the rain started again, I saw a familiar Land Rover in a country lay-by. After 9 hours on the bike, 6 of them in the rain, Rachel wisely swapped her seat on the bike for a drier one in the support vehicle.

As I pulled away - with determination to complete this rally on the Thunderbird - the rain really set in. Tt was already raining but now it was pouring, my last pair of gloves were soaked, and then the bike started to misbehave again, only running at full revs. Then I realised I’d lost the lights, and then the front brake gave up. I saw the sign for Helston and The Lizard...only 17 miles. I’m not giving up now, and kept the bike at full revs, hammering it down the lanes, taking all of the roundabouts in 3rd gear. I considered taking the more direct route across the middle of a round-about, rather than around it, but thought better of it. Hunched on the saddle, trying to keep the water out, watching the odometer count down the last 17 miles, shouting out at each mile marker for a morale boost “15....14....13”. Finally the sign for ‘Mile End’ appeared, the last mile South on mainland Britain. I arrived at Lizard Point just after sunset, 9pm, 4 hours late to the final checkpoint and the finish-line. No one in sight, the rally flags had long since been cleared away, but so good to be there, gazing over the sea at Lizard Point. I turn to get back on the bike, the lighthouse lighting up the horizon and the silhouette of the Thunderbird, reminding me of the view North from the lighthouse at the Northern tip of Scotland, just a few days ago, but it seems like an age away. The poor bike...bits missing, smelling bad, no lights, exhausted and in dire need of lubrication...we had a lot in common at that moment.

ANY LAST WORDS ABOUT THE RALLY EXPERIENCE?

When I got back to the rally camp from the finish line at The Lizard, the afterparty was in full swing, fires lit, drinks flowing, with a gale still howling across the Cornish peninsula - I walked into the food tent like a half-drowned cowboy. I was the last to leave Scotland and the last to arrive at the finish line, but once I started riding those roads with my team, there was no way I was going to miss out and take a rest day. Things went wrong, bits fell off, but I wouldn’t change it one bit, that was the adventure.

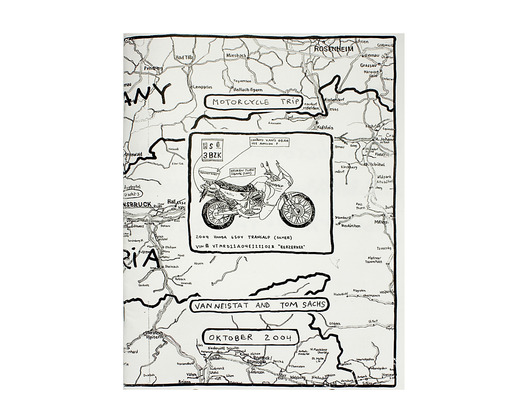

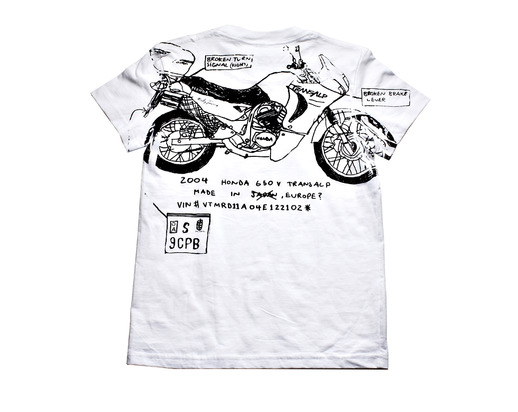

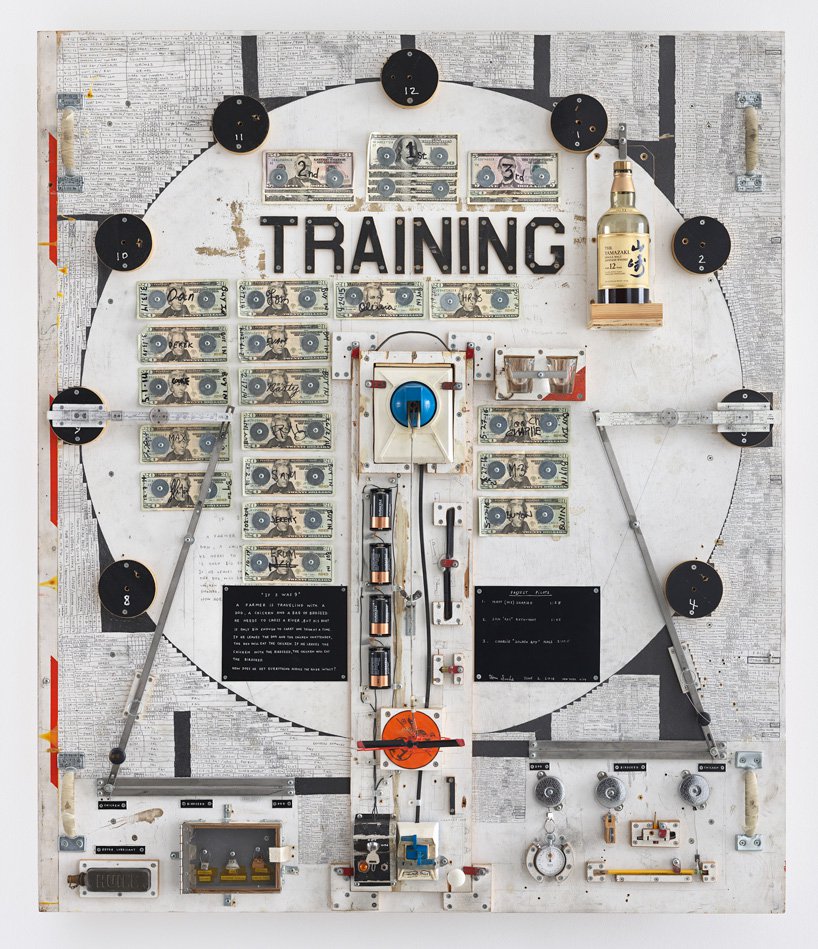

Tom Sachs: 'The Pack'

Not so far from Basel (the real town of Basel, not the metastasized art fair), the haute ski town of St Moritz is quietly becoming its own art destination. Painter/film director Julian Schnabel's son Vito Schnabel has chosen St Moritz for his own eponymous Swiss outpost, which is currently hosting an exhibition by artist Tom Sachs. Sachs' deep digs into his personal obsessions, like his years-long Outsider-esque variation-and-theme play on NASA imagery, makes his work among the most intriguing of all contemporary artists, on par with Grayson Perry for his widely variable expressions and air of sincerity in all the mad things he builds.

NYC Norton

Photos by Peter Domorak

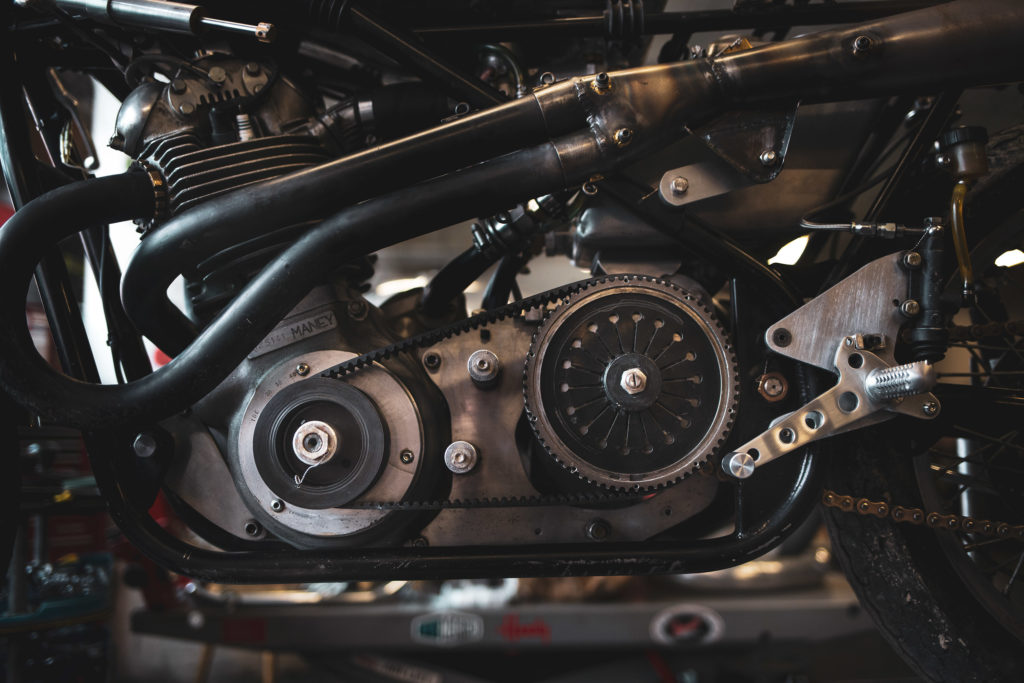

We all love beautiful things, and some people have a flair for creating beauty. It’s like cooking: you can give the same ingredients to a dozen chefs, and maybe, if you’re lucky, one will prepare a dish that’s simply exquisite, makes you roll your eyes back in your head, remembering the smell of madeleines, and the bicycling days of your youth. There are quite a few builders of Seeley-framed race bikes and café racers based on Norton Commando and Matchless G50 motors, but there’s one builder who stands head and shoulders above the rest combining these ingredients – a master chef named Kenny Cummings. His NYC Norton has a reputation for building impeccable race and road bikes around the Seeley frame, which is a great spine on which to hang your work. What is it that makes his bikes so special, especially as there have been so many Seeley-framed special builders since the 1960s?

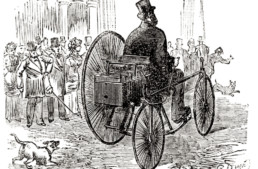

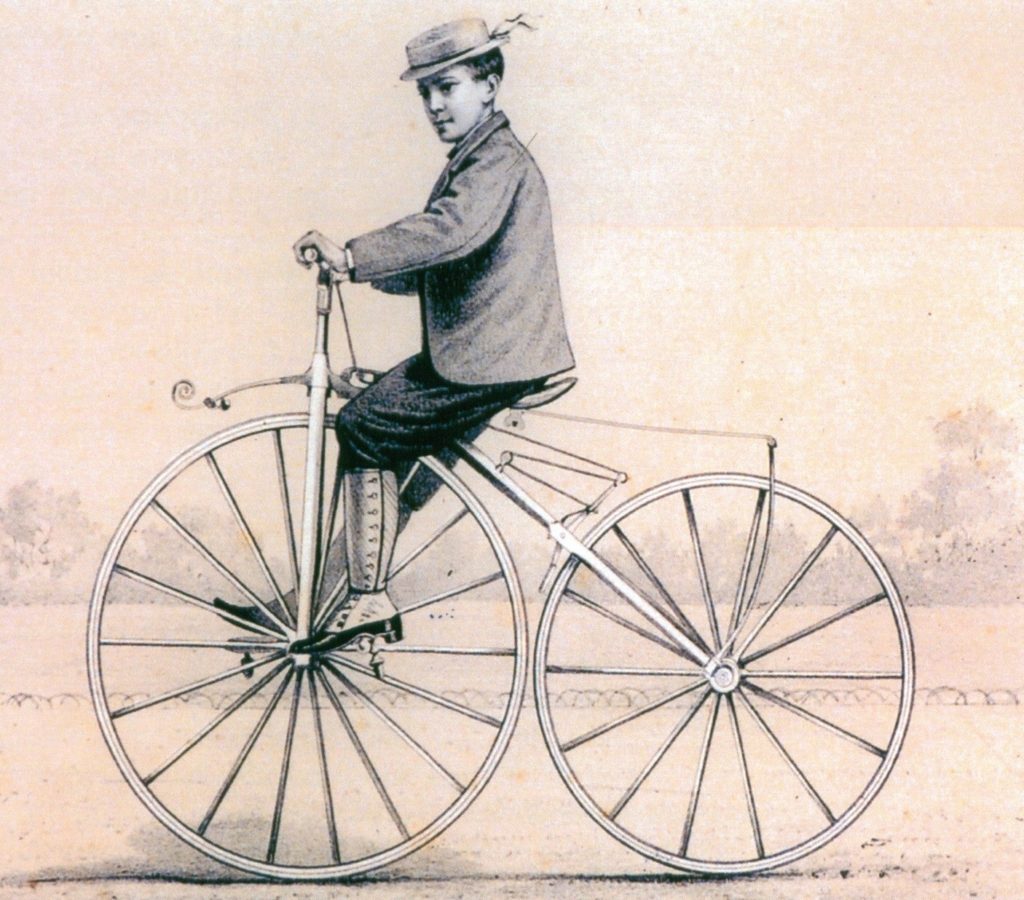

The Vintagent Archive: "A Two-Wheeled Steed" (1869)

Originally published in Chambers's Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Arts, May 1, 1869

I am not ashamed to admit having always cherished a peculiar admiration, at one time amounting to awe, for anything that would go round. A wheel has never been without its charm for me. I remember, at school, the affection with which I regarded wheels of all sorts, and how all my favourite toys as a child were rotary ones. The knife-grinder who used periodically to stop in front of our play-ground gates to grind the young gentlemen's knives, has probably died without knowing the inward comfort he administered to my breast, through the opportunities he afforded me of seeing his wheel go round at public expense.

Only the other day, I confided to an old friend that I still possessed a sneaking regard for wheels, and though he rewarded my confidence with a pitiful sneer, I know that this wretched old hypocrite himself keeps a wonderful brass top that will spin for an hour, under a glass case on his study-table, and in secret delights to watch it in motion.

A clever marine engineer, who loves wheels too, once told me with great gravity that the human mind has never yet discovered anything so wonderful as the principle of the common wheelbarrow, 'an invention,' he said, 'to which that of the steam-engine itself is nothing. The wheelbarrow,' he went on, 'is the only example I am acquainted with in which the very weight of a load is fairly utilised as a locomotive power.' There was a copy of Punch on my table. Our conversation had turned to the subject of wheelbarrows from looking at Mr Keene's vignette, in which, some three years ago, Mr Punch was depicted as Blondin, but performing the impossible feat of wheeling himself in a wheelbarrow along a tight-rope in the Crystal Palace transept.

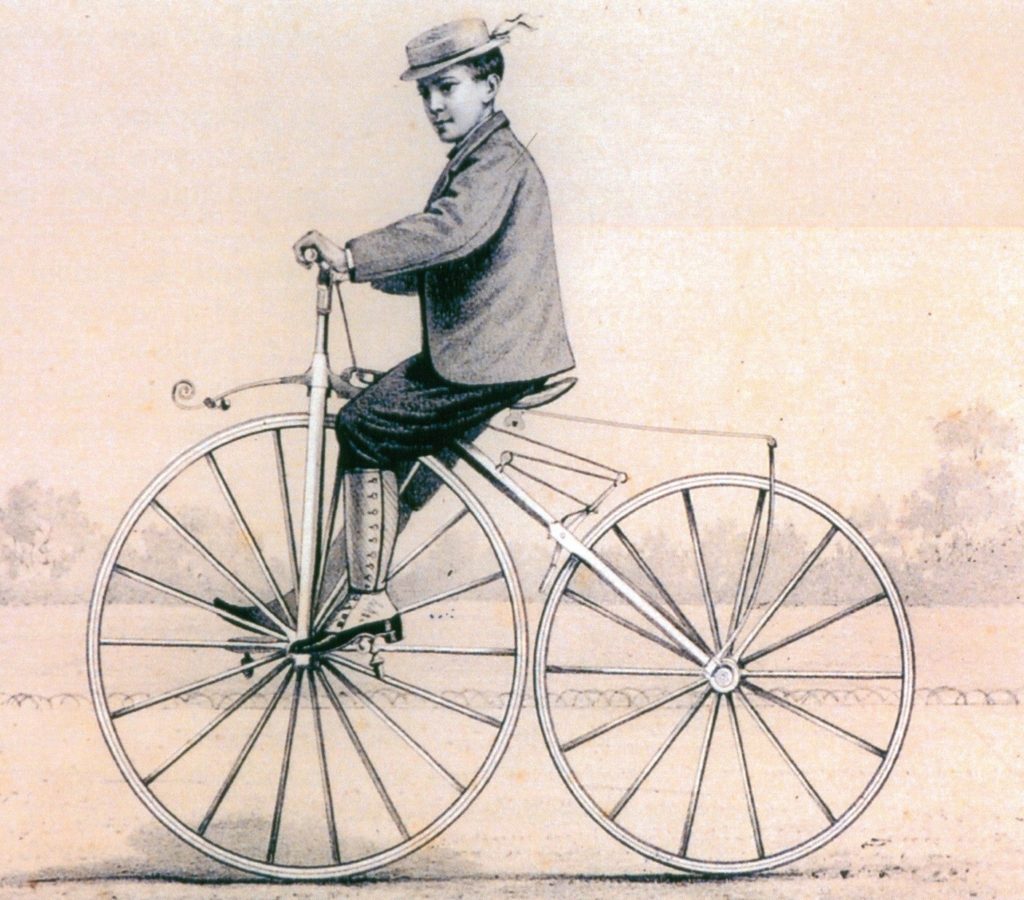

The two-wheeled velocipede or bicycle is in part a realisation of Mr Keene's picture. It depends upon motion for its balance. The two wheels, one in front of the other, with a saddle between, whether mounted by a rider or not, will not stand upright for a single instant at rest; but, like the boy's hoop, being kept trolling, they maintain a perfect equilibrium.

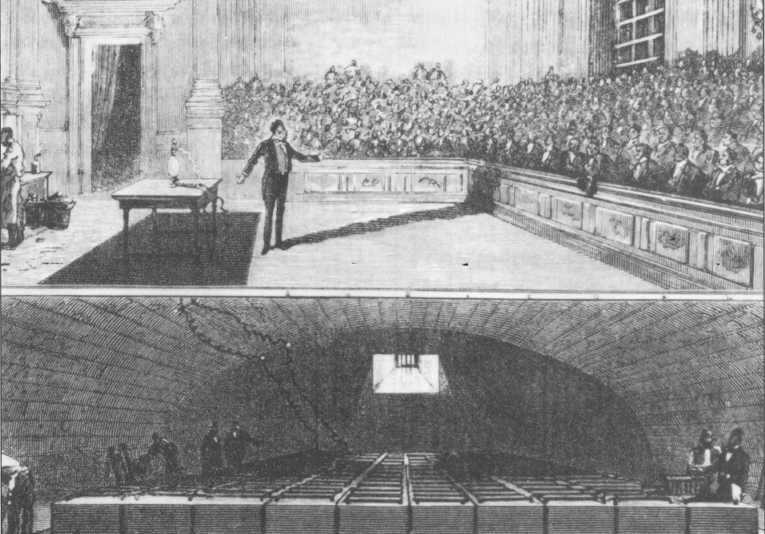

A Wonder Which Drove All Paris Mad

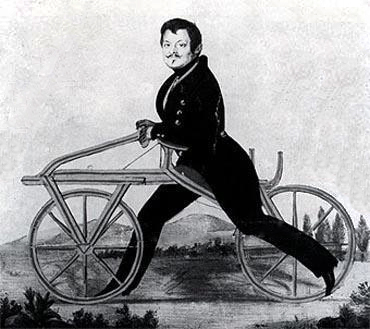

The bicycle can hardly be called a 'new invention,' being to a great extent a modification of that very old toy-vehicle of our fathers, the hobby-horse, whereon the rider used to sit and row himself along, so to speak, by paddling with his feet on the ground; at the same time, the entire reliance on the principle that motion would be, under any circumstances, sufficient to produce balance, is sufficiently novel almost to justify the use of such a term. The French appear to be entitled to whatever of credit attaches to the original invention of the hobby-horse (a miserable steed at best, which wore out the toes of a pair of boots at every journey. M. Blanchard, the celebrated aeronaut, and M. Masurier conjointly manufactured the first of these machines in 1779, which was then described as 'a wonder which drove all Paris mad.' The French are probably justified, moreover, in claiming as their own the development of this crude invention into the present velocipede, for, in 1862, a M. Riviere, a French subject, residing in England, deposited in the British Patent Office a minute specification of a machine identical with that now in use. His description was, however, unaccompanied by any drawing or sketch, and he seems to have taken no further steps in the matter than to register a theory which he never carried into practice. Subsequently, the bicycle was re-invented by the French and by the Americans almost simultaneously, and indeed, both nations claim priority in introducing it. It came into public notoriety at the last French International Exhibition, from which time the rage for them has gradually developed itself, until in this present 1869, it may be said, much as it was a century ago, that Paris has again been driven mad on velocipedes.

The two-wheeler, when on the turn, stands at an inclination like a skater's body.

With regard to the speed which may be attained, fifteen miles an hour, under the most favourable circumstances, that is, good hard road, not level, but without very steep hills, and no wind blowing, is probably the limit of the velocipede's powers; but a pace of nine or ten miles an hour may be maintained for five or six hours without distress. Long journeys on level road are perhaps the most fatiguing, on account of their monotony, because then the feet, as in walking, are nearly always at work. Still, even in this case, the driver can maintain his speed with one foot, resting the other on the leg-rest; or, if disposed, he may even place both feet on the rests, and run four or five hundred yards without working at all. The slightly increased labour of climbing a hill is nothing to the zest imparted by a knowledge that there is sure to be a hill the other side to go down, and that is the most luxurious travelling that can be imagined. Descending an incline at full speed, balanced on a beautifully tempered steel spring that takes every jolt from the road - wheels spinning over the ground so lightly they scarce seem to touch it - the driver's legs rested comfortably on the cross-bar in front - shooting the hill at a speed of thirty or forty miles an hour - the sensation is only comparable to that of flying, and is worth all the pains it costs in learning to experience it.

The sensation is only comparable to that of flying.

The velocipedist feels but one pang when he reaches the bottom of a hill, and that is, that it is over; and but one exquisite wish, which is, that the entire country might somehow become metamorphosed into down-hill. But the hill is bountiful even after one has left it, for the impetus derived from a good incline will carry the rider at least the hill's length on level ground before he need remove his feet from the rests and commence working again. The slightest incline on a good road is sufficient to obviate all necessity for working with the feet, so that what little labour there is (and it is of the easiest), is by no means incessant. In a journey of twenty miles on good road, a driver should not work more than twelve - the inclines do the rest. Of course, there are hills so steep that to ascend them is impossible: yet, for myself, living in a hilly county, which I have pretty well explored on my two-wheeled steed, I can reckon up their number on the fingers of one hand. There are also hills where the labour becomes as much as, or more than, walking, but these must be of a gradient something like one in twelve, and such hills are not frequent. When they do occur, the rider may, if he will, dismount.

Good hard road is essential for velocipede-driving. In muddy or loose gravelly road, the work becomes proportionately laborious. But with good 'going ground,' it is difficult to convey how little labour is really required to maintain a high rate of speed - in fact, the great trouble with beginners is to get them to restrain the expenditure of muscular force. Velocipede-driving is, I believe from experience, most healthy and exhilarating, since it exercises all the muscles of the limbs in a manner much more uniform than would at first be credited, and certainly without undue strain on any part of the body. To the spectator, the velocipedist appears almost wholly to employ his legs, but in reality the muscles of the arms are in strong tension in the act of grasping the handles, so as to counteract the motion of the feet on the pedals, which motion would otherwise tend to sway the wheel from side to side. In fact, after a long journey, the driver will feel more fatigue in his arms than in his legs. Once mastered, the two-wheeled steed is a docile and tractable animal, equally sensitive to bit and bridle, and a sturdy friend to the traveller. For him the pike-men throw open their gates without asking for toll. He needs neither corn nor beans, nor hay nor straw, neither hostler nor stableman. His stable is a bit of the passage-wall, against which he reposes, without taking up any room, until his master needs him again - his only food, a pennyworth of neat's-foot oil per month.

Now that the supposition about the new velocipedes frightening horses has been proved to be groundless, there seems little reason to doubt they will become equally popular in this country; and that after the first 'rage' for the novelty has died away, the two-wheeled steed may drop into its proper place as a serviceable nag, that can do a great deal of work in a very little time, and, after the first cost, at a very inconsiderable expense."

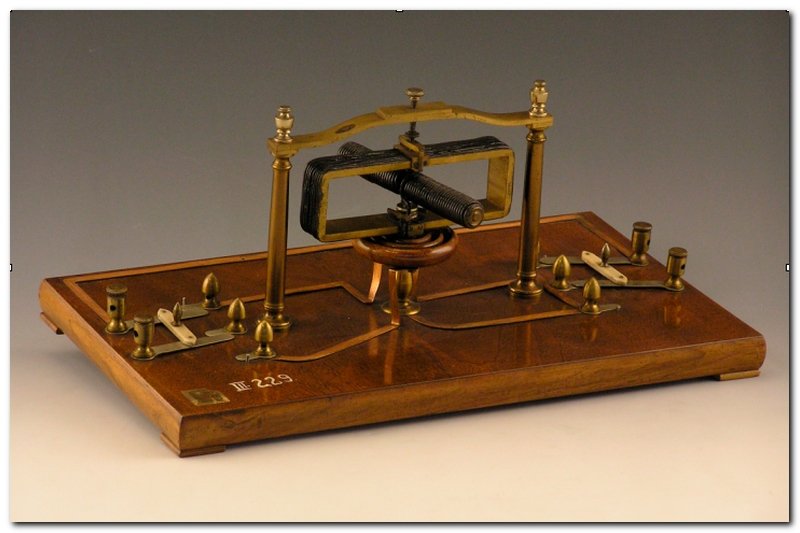

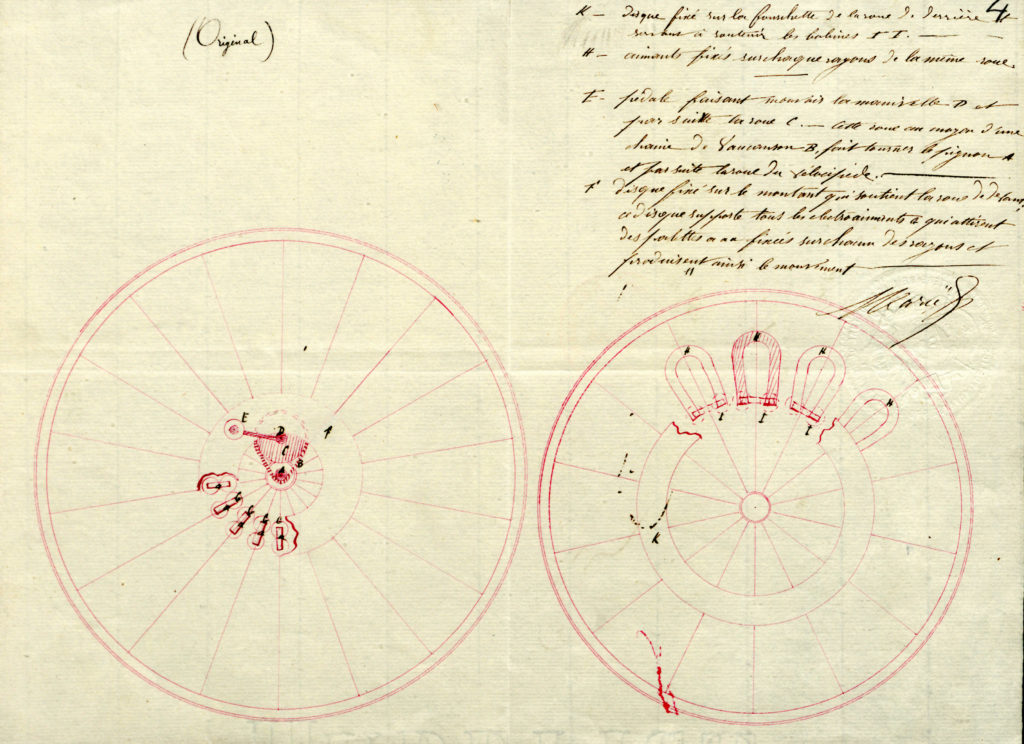

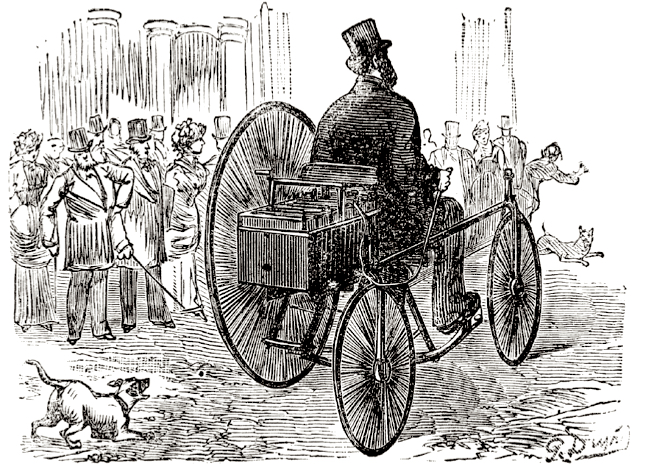

The Current: A History of Electric Motorcycles (Part 1)

[Forward: in the book 'The Current' (2018 Gestalten), I stated in my introductory essay that 'Electricity is Modernity'. The scientific and technical process of harnessing electricity for human use defines the modern era, and has transformed our lives in ways we scarcely acknowledge today. We have become creatures seemingly independent of the sun, moon, and stars, or at least, the ability to abolish the night gave rise to such thinking, which increasingly looks like hubris. It's the use of electricity, not fire, that is the 'true Promethean moment', although our embrace of fire in the form of petroleum looks more like a Faustian bargain every day.

The history of electric vehicles is little discussed today, but goes back well into the 19th Century, paralleling developments in steam power for vehicles, and predating the use of petroleum to power engines. We all know the story of Benjamin Franklin and his experiments with kites in storms in the 1700s, but compared to steam (the first experiments date back thousands of years), electricity is a relatively new field. In this series, The Vintagent explores the roots and development of electric powered two-wheelers, as part of our celebration of e-Bikes on our web channel The Current.]

"The slightly increased labour of climbing a hill is nothing to the zest imparted by a knowledge that there is sure to be a hill the other side to go down, and that is the most luxurious travelling that can be imagined. Descending an incline at full speed, balanced on a beautifully tempered steel spring that takes every jolt from the road - wheels spinning over the ground so lightly they scarce seem to touch it - the driver's legs rested comfortably on the cross-bar in front - shooting the hill at a speed of thirty or forty miles an hour - the sensation is only comparable to that of flying."

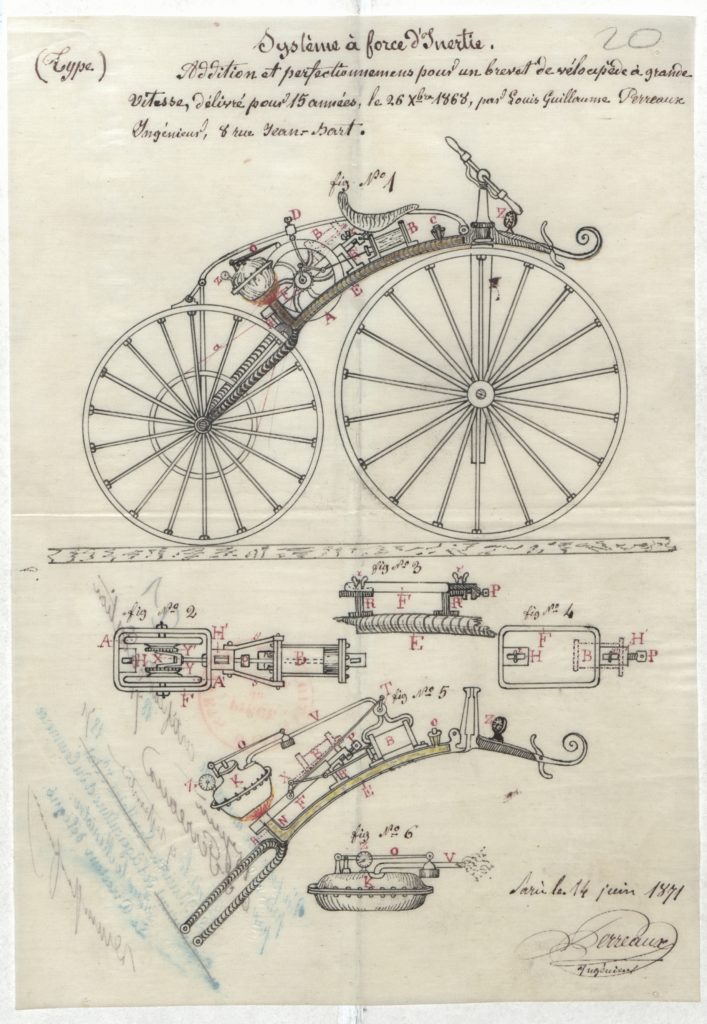

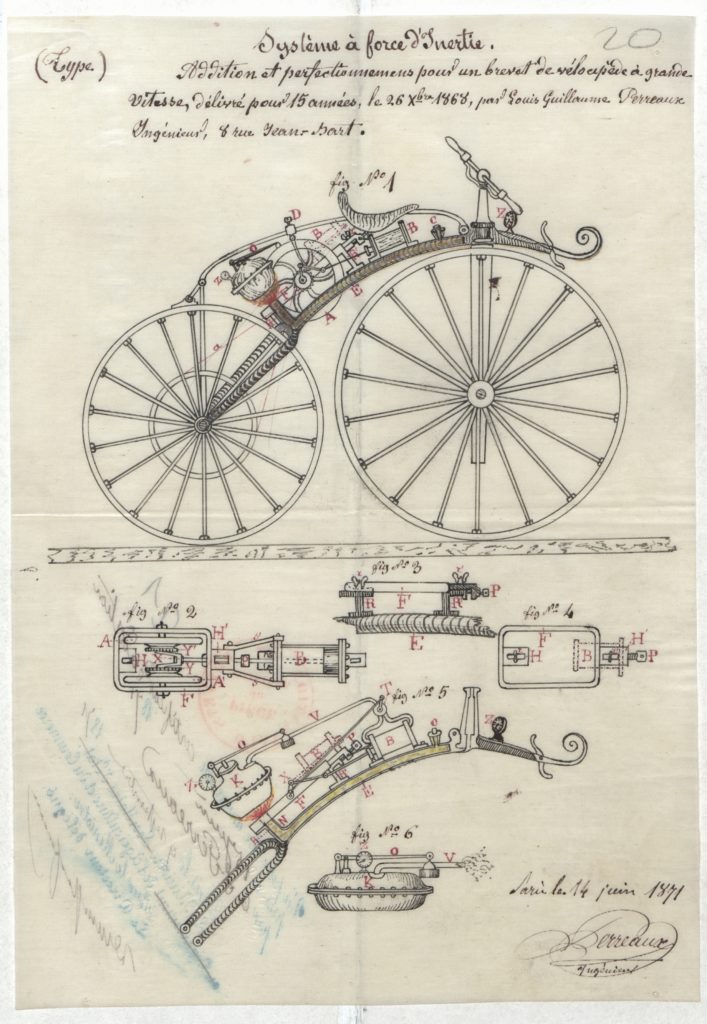

The idea of adding a motor to the bicycle was a natural follow-up, to perpetuate this amazing feeling: the exhilaration felt by all motorcyclists on an open road and a rising throttle. The idea for the electric motorcycle was first suggested (it seems) by the very fellow who first patented the concept of the motorcycle itself: Louis-Guillame Perreaux. There has long been a debate over who built the first motorcycle - Perreaux or Sylvester H. Roper (read our story about Roper here), but it seems today Roper built the earlier machine, while Perraux probably built his in 1870/'71, and patented his steam-cycle in 1871 (Roper never patented his motorcycle, but did ride it extensively). Of course, a credible claim can be made that the motorcycle concept dates back to 1818, as discussed in our post on the 'Vélocipédraisiavaporianna'.

Next: The first electric motorcycles!

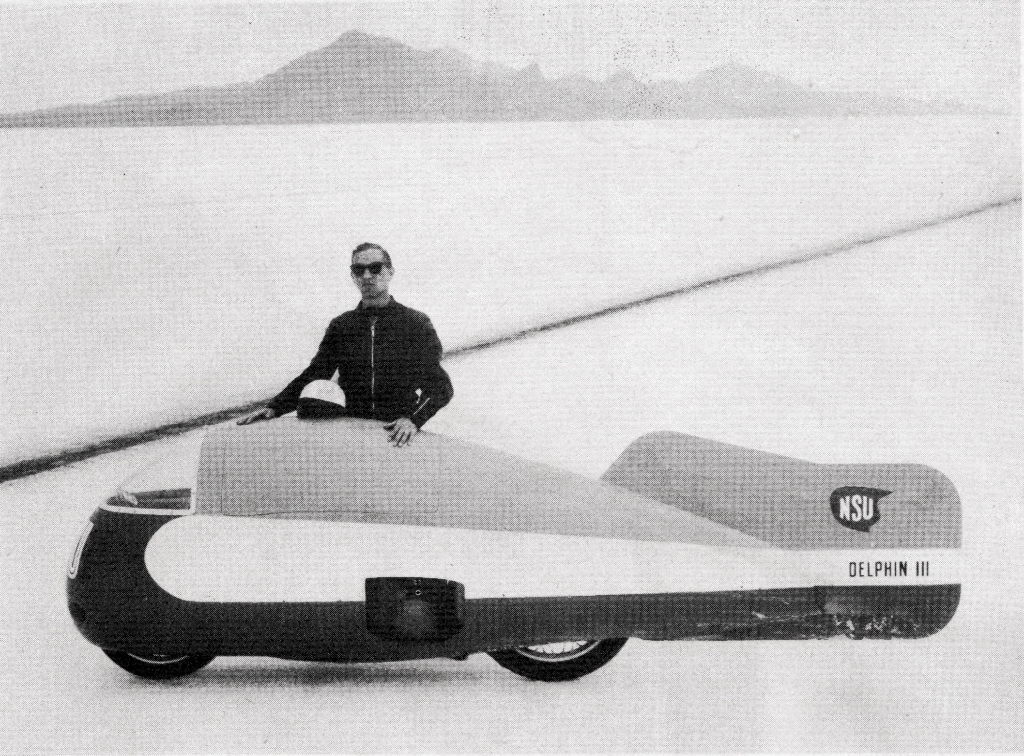

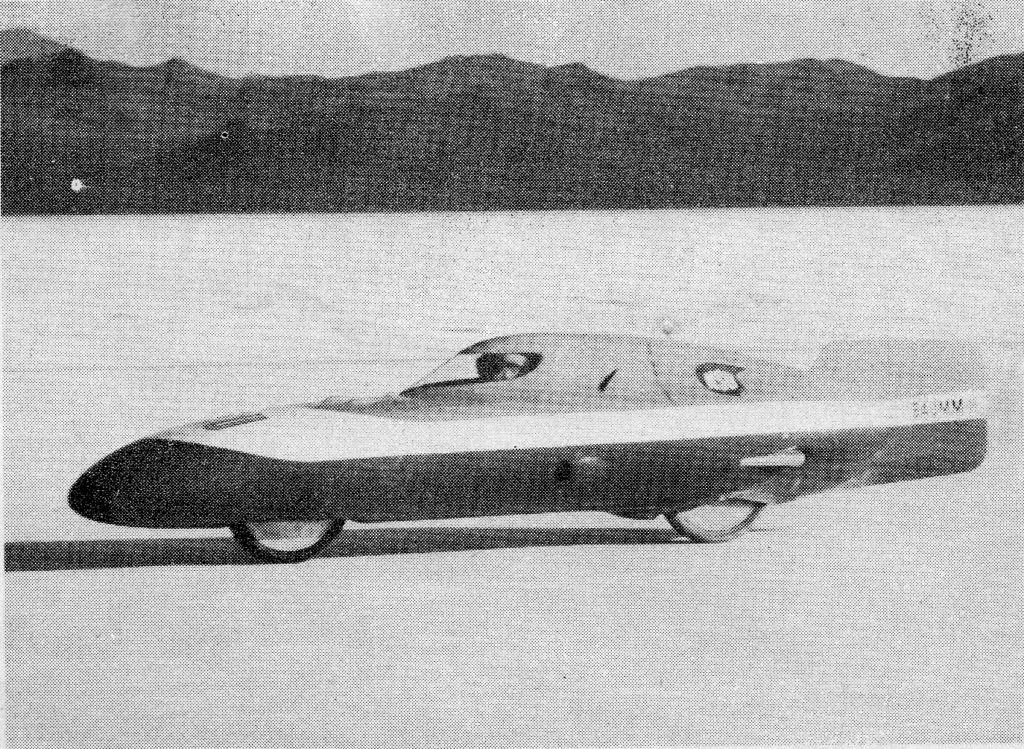

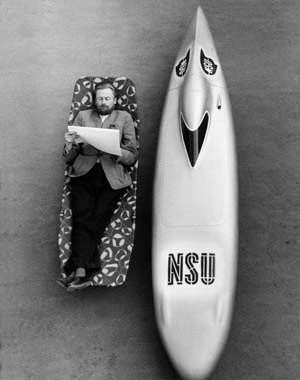

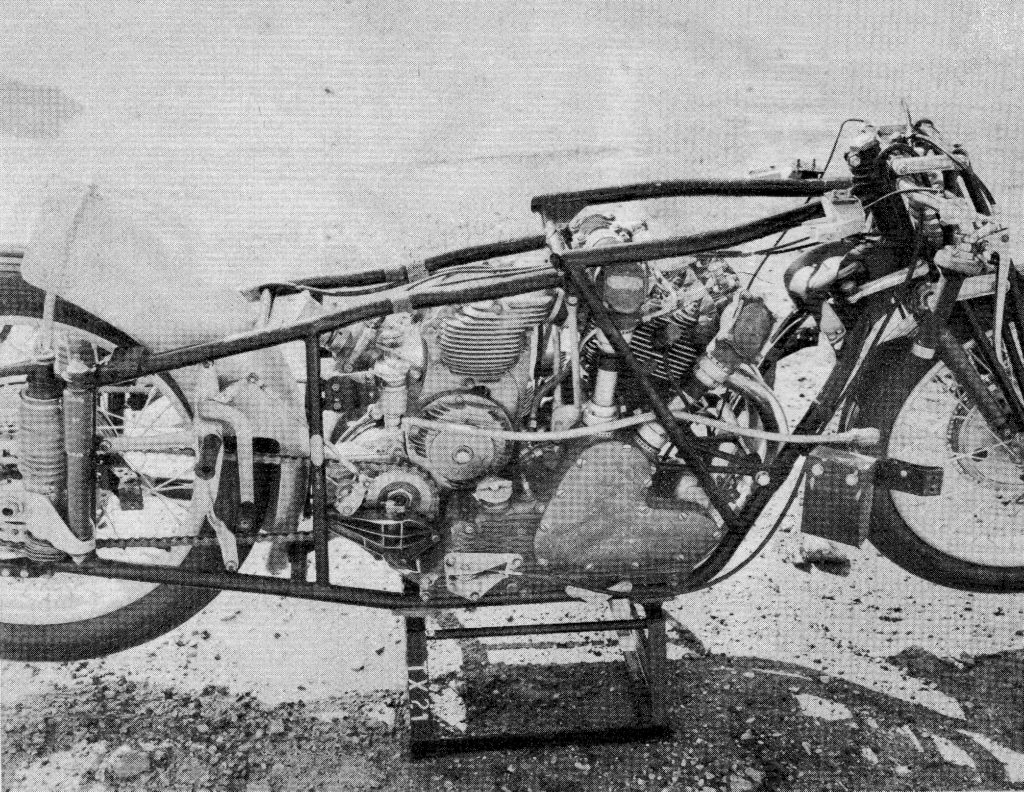

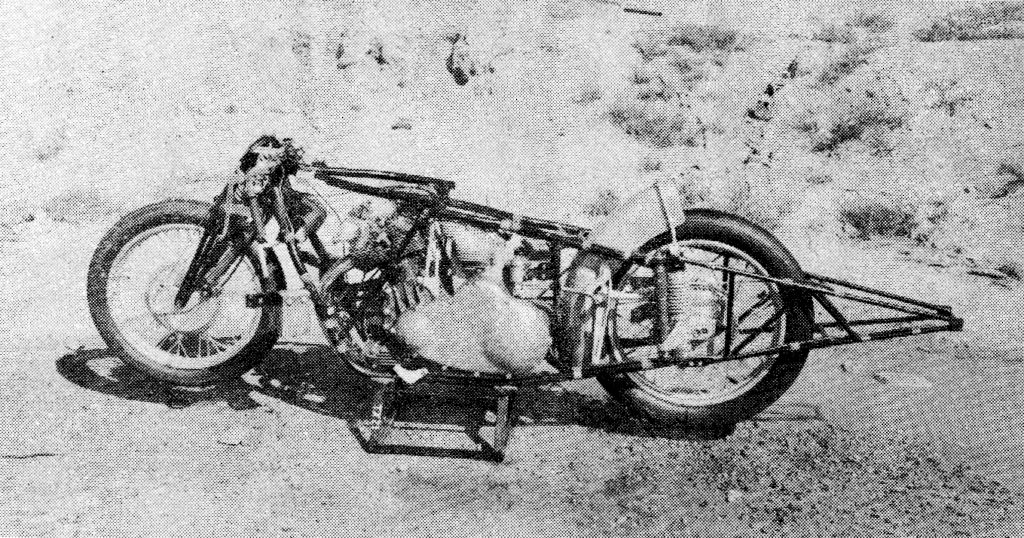

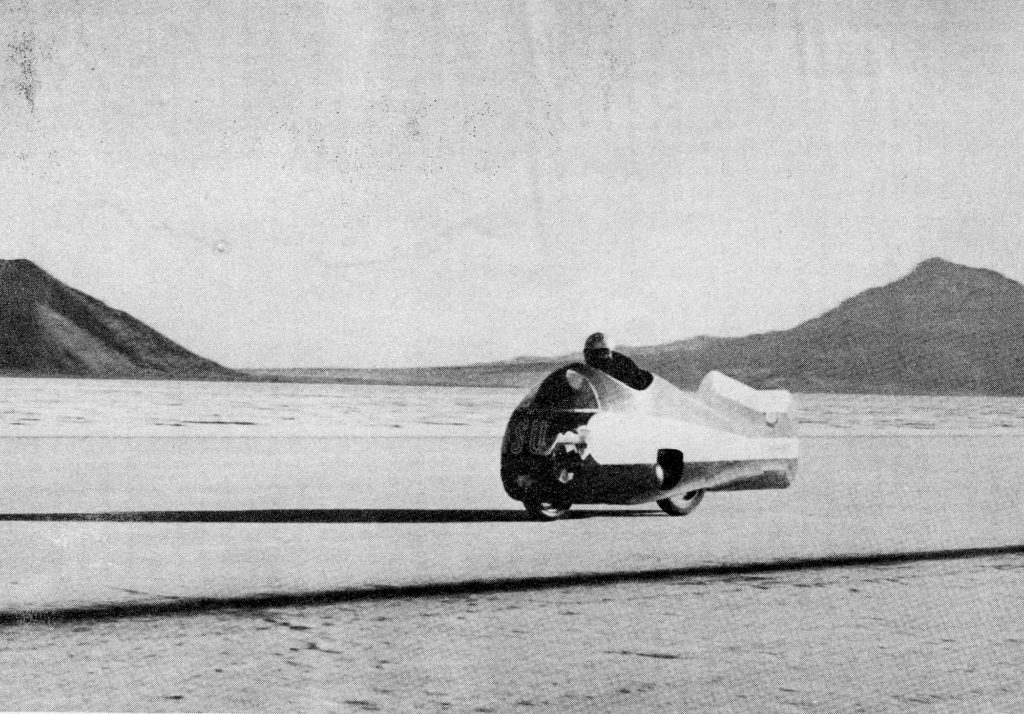

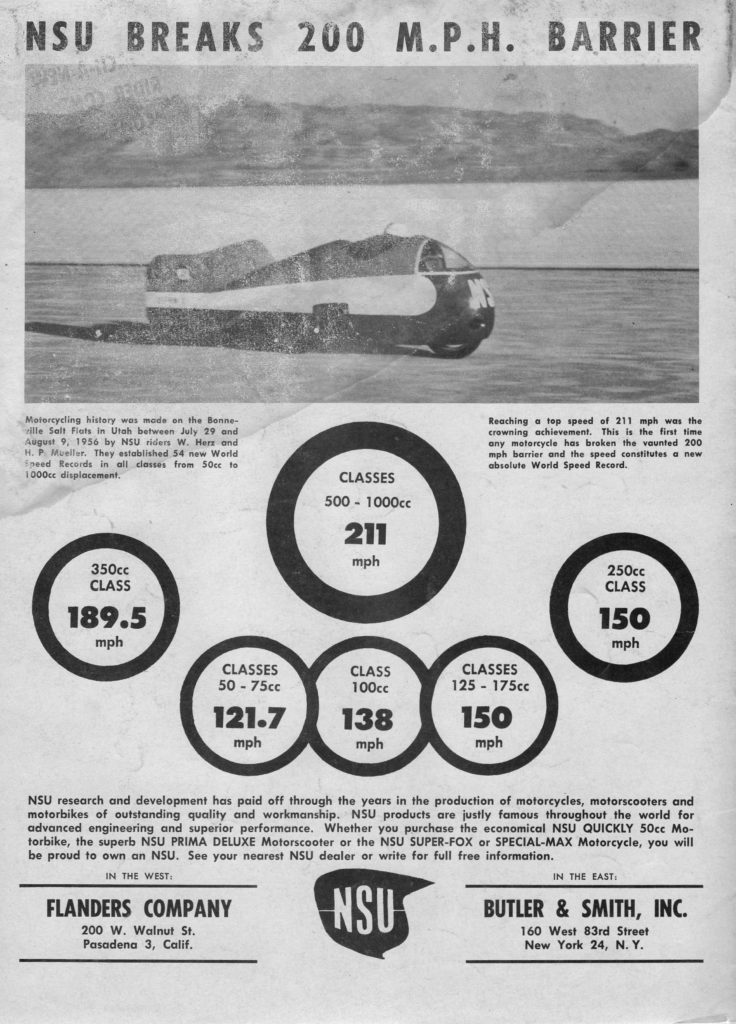

NSU Breaks 200mph Barrier!

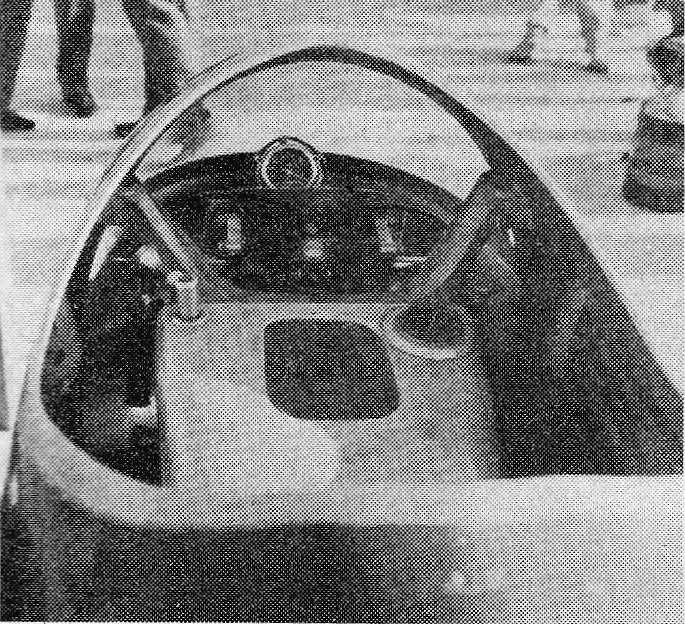

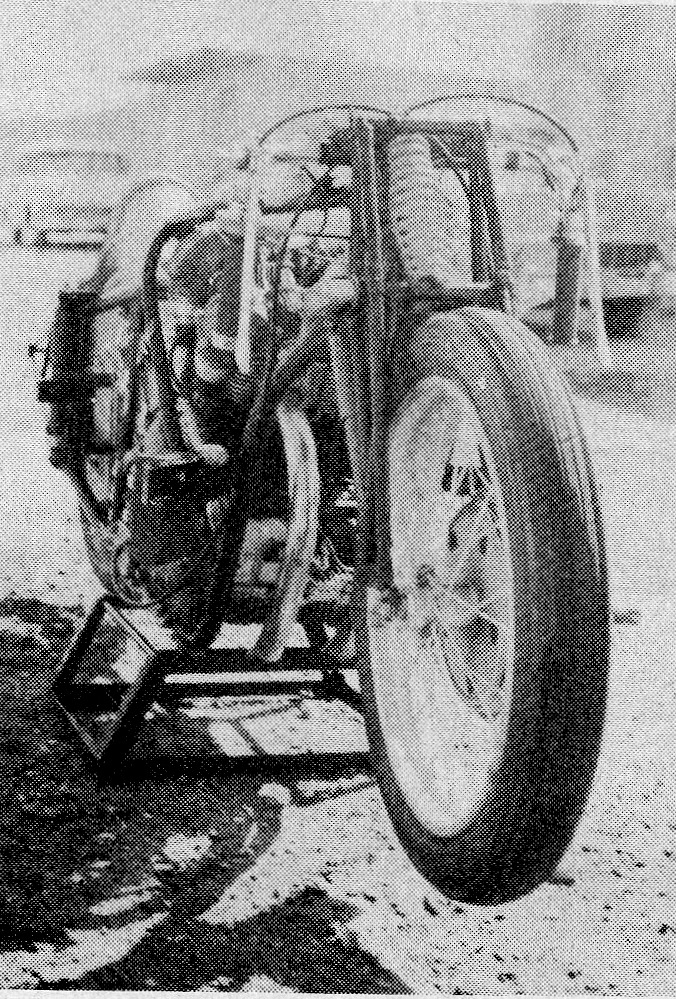

In the midst of the worst motorcycle market in German history, the NSU factory opted to go big with a remarkable multi-bike assault on the World Speed Record on the Bonneville Salt Flats, taking on six capacity classes: 50cc, 100cc, 125cc, 250cc, 350cc, and 500cc. In 1956 the factory shipped over a quiver of streamliners to Utah, arriving on July 25th, and nothing was left to chance; NSU's Chairman Dr. G.S. von Heydenkampf and Technical Director Viktor Frankenberger were on hand to oversee the mechanics, technicians, and officials (including Piet Nortier, from the F.I.M., in charge of timing). A traveling machine shop had also been shipped from Germany, with enough spares and equipment to deal with any mechanical emergency.

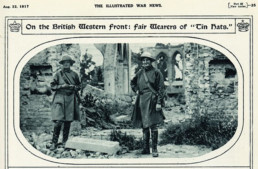

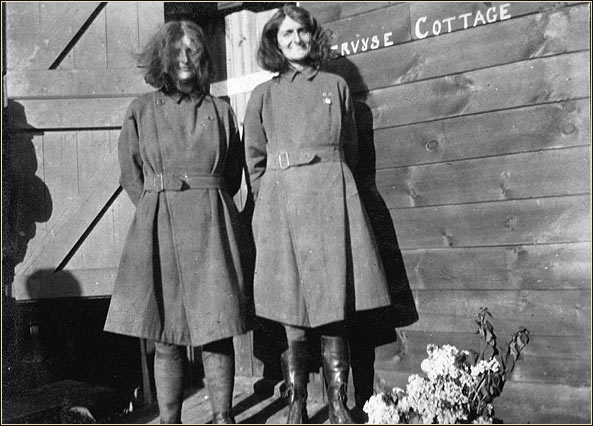

'The Angels of Pervyse'

They were the 'most photographed women of the War' - that war being WW1 - which is a pretty unlikely lot for a couple of nurses. But Mairi Chisholm and Elsie Knocker were a pretty unlikely pair, who spent the War a mere 100 yards from the front line of Ypres ('Wipers' in Tommy slang), in a makeshift basement hospital treating wounded soldiers - British, Belgian, and German alike. Their bravery, and perhaps love of danger, earned both women the highest commendations of that conflict, from Belgian and British authorities. and an awful lot of press in the day. They're nearly forgotten now, but in the 'Teens, Mairi and Elsie were household conversation topics as incredibly brave and 'plucky' women in the Victorian era, before women even had the right to vote. And the path that led to their involvement in that dreadful conflict was a mutual love of motorcycles.

Elsie Knocker was born Elizabeth Shapter (July 29 1884 - Apr 26 1978) in Exeter, was orphaned by age 6 (her mother died when she was 4, her father at 6, from tuberculosis), and adopted by Emily and Lewis Upcott, a teacher at Marlborough College. The Upcotts had the means to send Elsie to study at Chatéau Lutry in Switzerland, and she later trained as a nurse at the Children's Hip Hospital in Sevenoaks. She married Leslie Duke Knocker in 1906, and they had a son, Kenneth, but divorced soon after. She then earned her living as a midwife, and to save face during Victorian social strictures, invented the story that she was widowed when her husband died in Java.

She became a passionate motorcyclist, and wore very stylish outfits while riding, notably a dark green leather skirt and long leather coat, which was cinched at the waist to "keep it all together" - the outfit was designed by Alfred Dunhill Ltd! She owned various motorcycles, including a Scott two-stroke, a Douglas flat twin, and a Chater-Lea with sidecar, which she took to Belgium during the War. She earned the nickname 'Gypsy' as a member of the Gypsy Motorcycle Club, and because she loved the open road.

Chisholm and Elsie Knocker had to apply for Dr Munro's Flying Ambulance Corps, and beat out 200 other applicants. Knocker was a natural, both as a nurse, and because she was an excellent mechanic (and driver), and spoke both German and French fluently, from her Swiss schooling. Lady Dorothie Fielding and May Sinclair were also included in Munro's special unit, with all women acting as nurse/ambulance drivers, and they all landed at Ostend in September 1914. The team initially set up camp at Ghent, but by October they'd moved to Furnesin, near Dunkirk, ferrying wounded soldiers to the hospital who'd been carried from the Front. They soon realized they'd save a lot more lives if they were actually at the Front, regardless the horrors they'd already witnessed. "No one can understand, unless one has seen the rows of dead men laid out. One sees men with their jaws blown off, arms and legs mutilated" - Chisholm.

This was their life for an incredible 3 1/2 years; treating the wounded as totally free agents, who had to raise their own funds at first. Luckily, they had a camera, and began photographing the front, which secured them space in British newspapers, and the fame of these women motorcyclists began to grow, and funds to flow. When they needed a bullet-proof door for their clinic, it was supplied by Harrod's! They returned occasionally to London on fundraising tours, riding a sidecar outfit and collecting money, knitted socks and hats for the soldiers, as well as tobacco and cigarettes. The press loved them; 'Sandbags Instead of Handbags!' proclaimed one British paper.

Their proximity to a local Belgian garrison eventually gained them an official attachment to the Belgian military. Word of their bravery and their work saving soldiers under incredibly difficult conditions spread far and wide. Fellow Flying Ambulance Corps member May Sinclair described Knocker as "having an irresistible inclination towards the greatest possible danger." Many times the women crossed the front lines to save fallen soldiers, sometimes carrying them on their backs through the mud, and under fire, including one German pilot who'd been shot down and wounded in No Man's Land. For that, they were awarded the British Military Medal and were made Officers of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, and awarded the Order of Léopold II, Knights Cross. Yet more awards and honors followed, including the Croix de Guerre, which meant the ladies had to be saluted by all the soldiers, which they found most amusing.

After the War, the Belgian Baron discovered that his wife Elsie Knocker was not a widow, but a divorcée, and the Catholic church forced an annulment of their marriage. Read into it what you will, but apparently that was the breaking point of her friendship with Mairi Chisholm. Chisholm took up auto racing after the War, but her injuries (from the gas attack and septicaemia) had weakened her heart, and doctor advised her to take it easy. She spent the rest of her days on the estate of her childhood friend May Davidson, and moved with her to Jersey in the 1930s, and never married (a man). Elsie Knocker was a senior officer in the WAAF during WW2, and earned distinction, but lost her son in the RAF in 1942, and left the military to care for her elderly foster-father. She lived the rest of her life in Ashtead, Surrey, and was notorious for being "flamboyantly dressed with large earrings and a voluminous dark coat!"

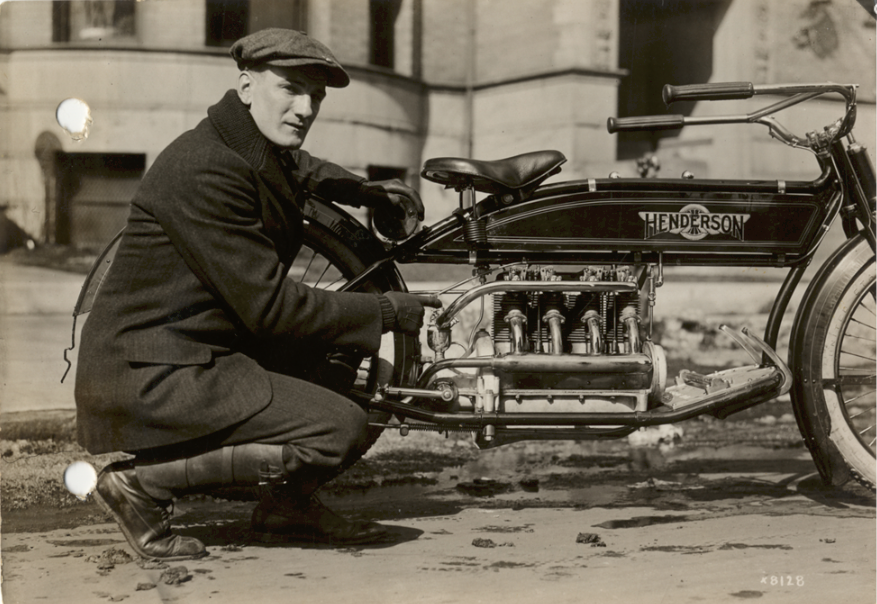

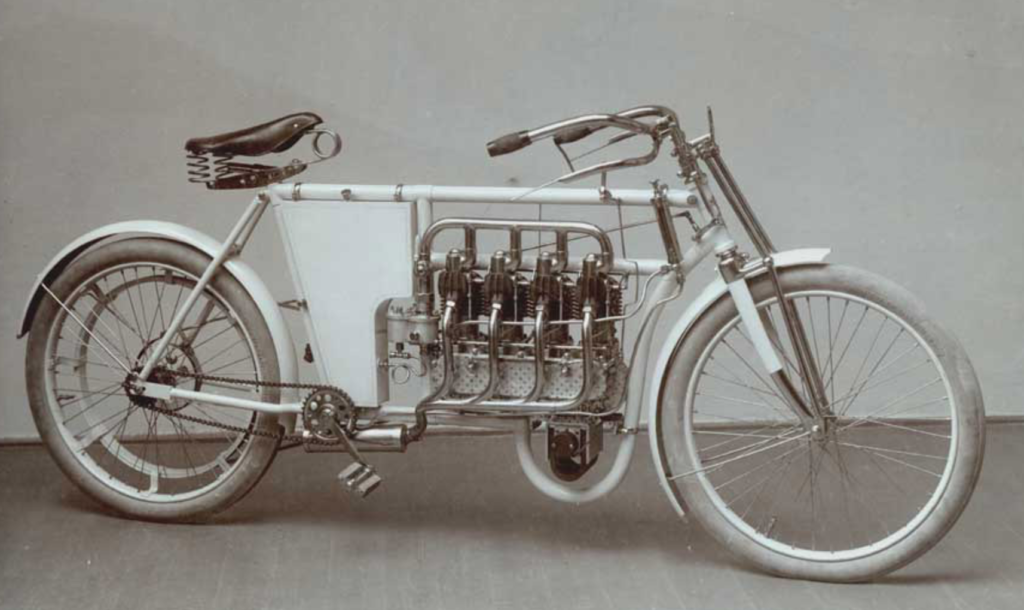

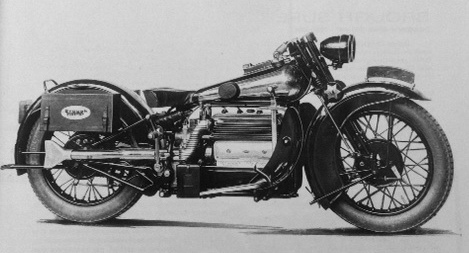

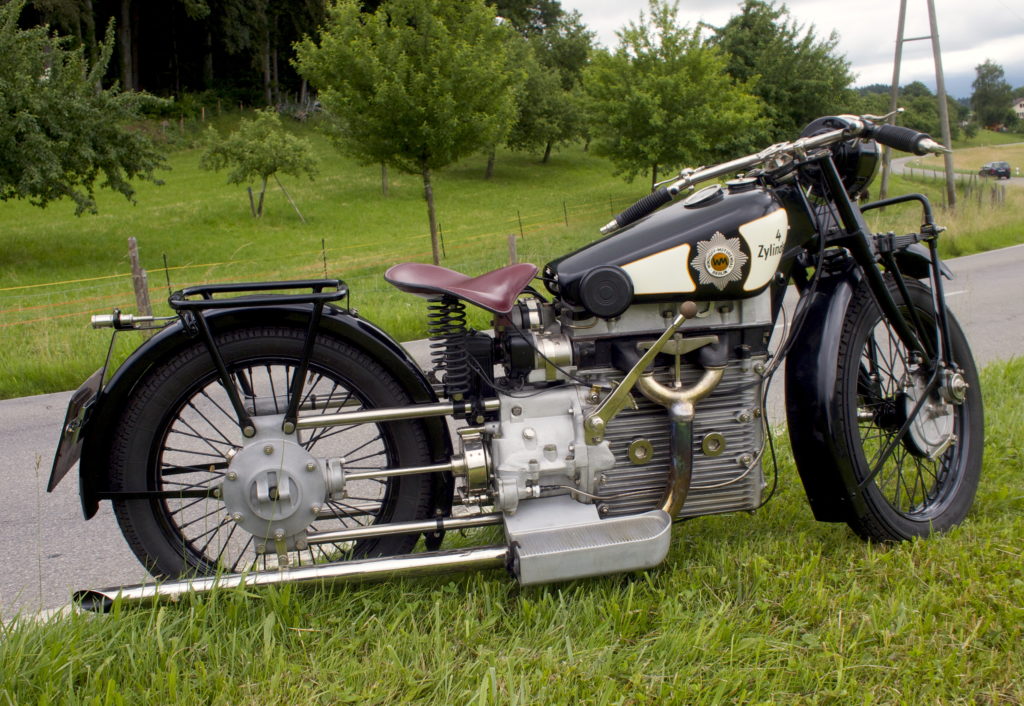

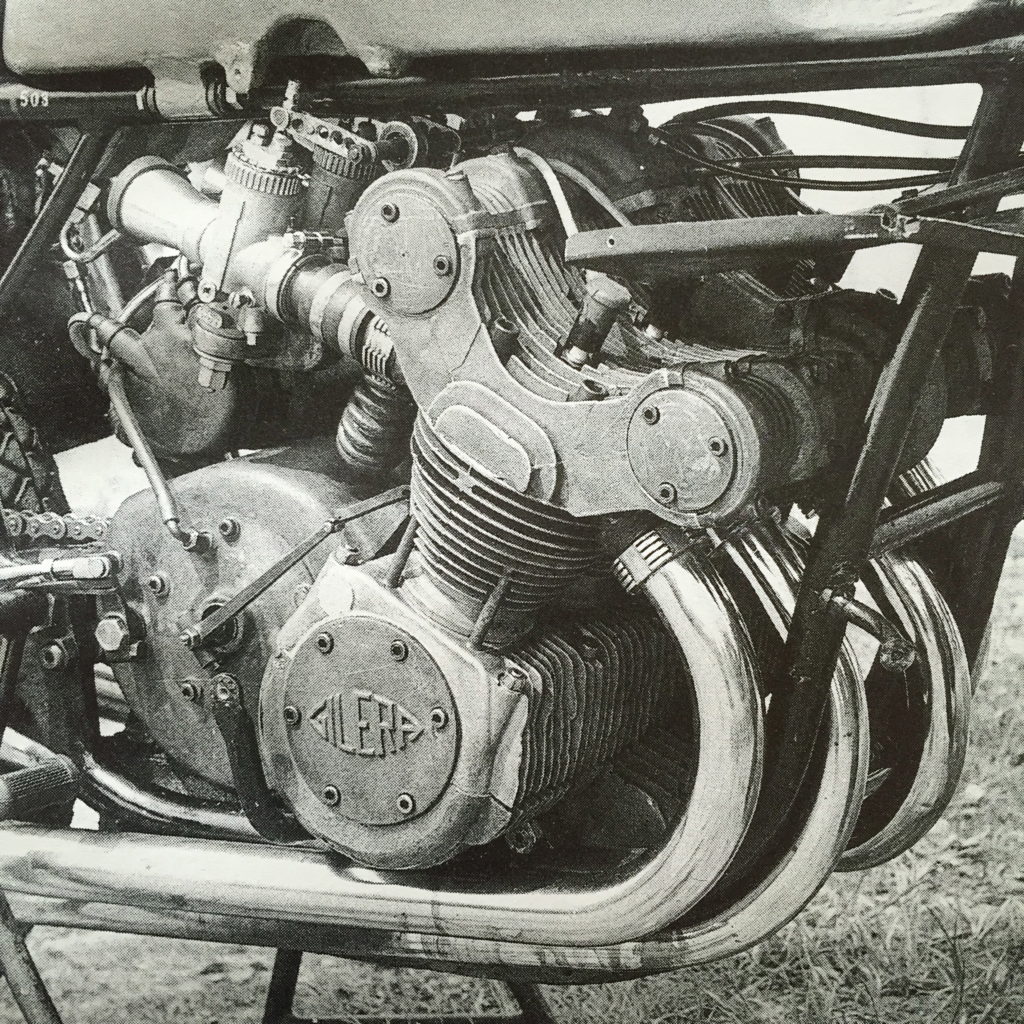

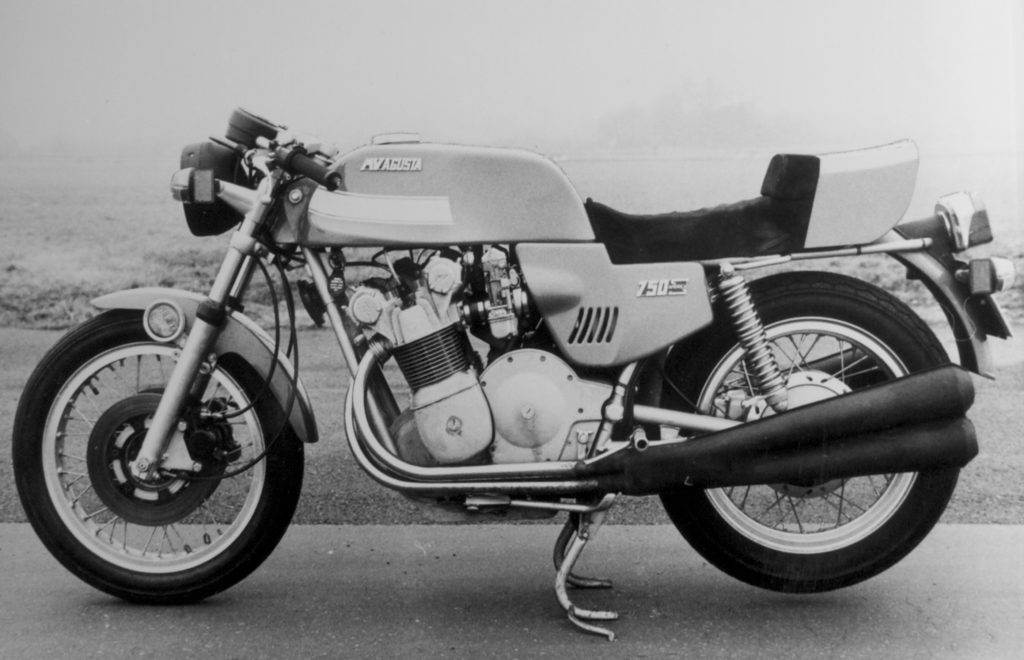

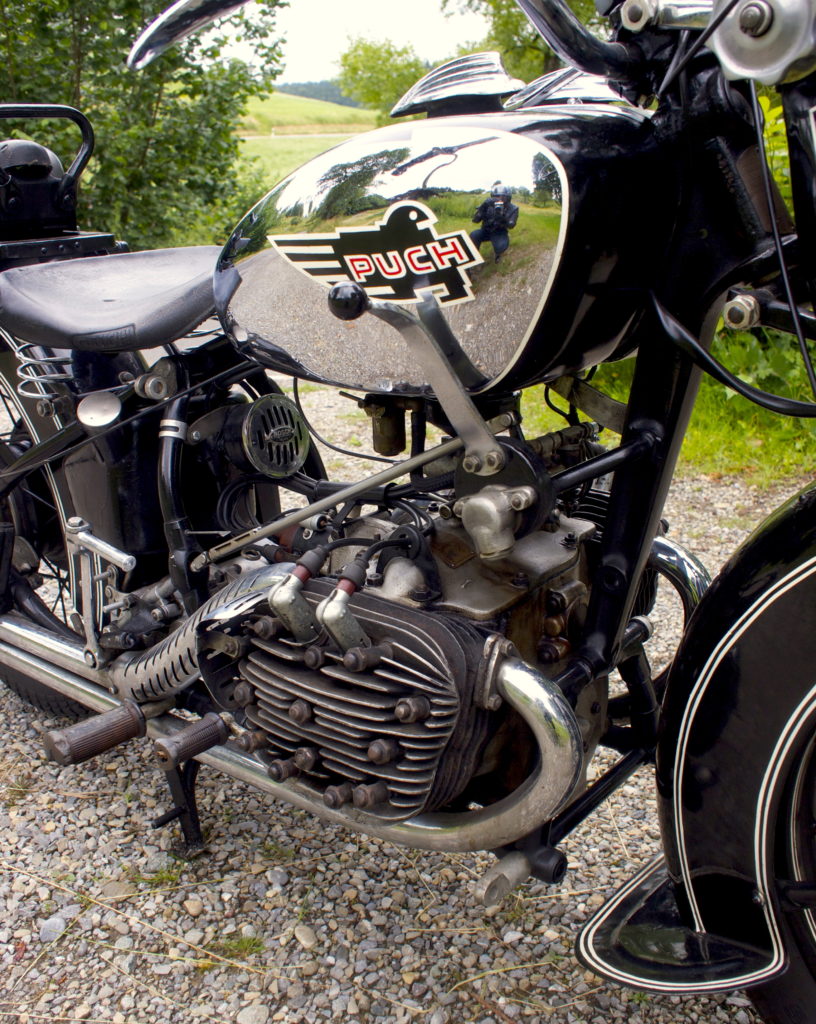

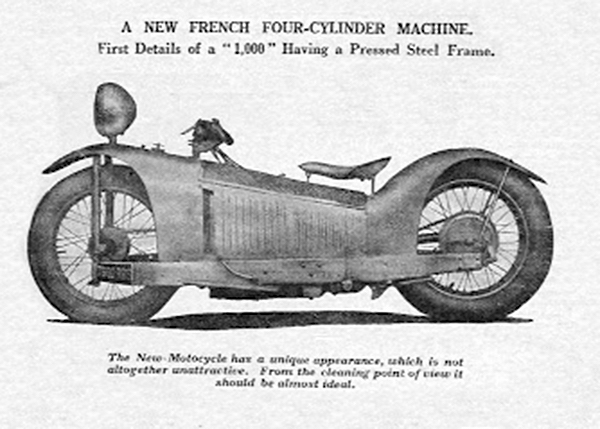

Fours Before Honda: 70 Years and 50 Brands

You’d be forgiven thinking Honda built the first production 4-cylinder motorcycle in 1968, when they introduced the CB750 and changed motorcycling forever. Nobody had previously built an inexpensive, reliable, high-performance ‘four’ in history; it was a magic trifecta, but in truth, Honda had plenty of four-pots to study, and copy, when designing the immortal CB line. From the earliest days of the motorcycle (and auto) industry, it was understood that more cylinders for a given engine capacity meant higher rpms with less stress, and more horsepower with smoother running, at the expense of increased complication and production costs. The motorcycle press from the ‘Noughts onward dreamed of fours as the ‘ideal’ machine, an exciting vision of the future, which indeed became a reality by the 1970s.