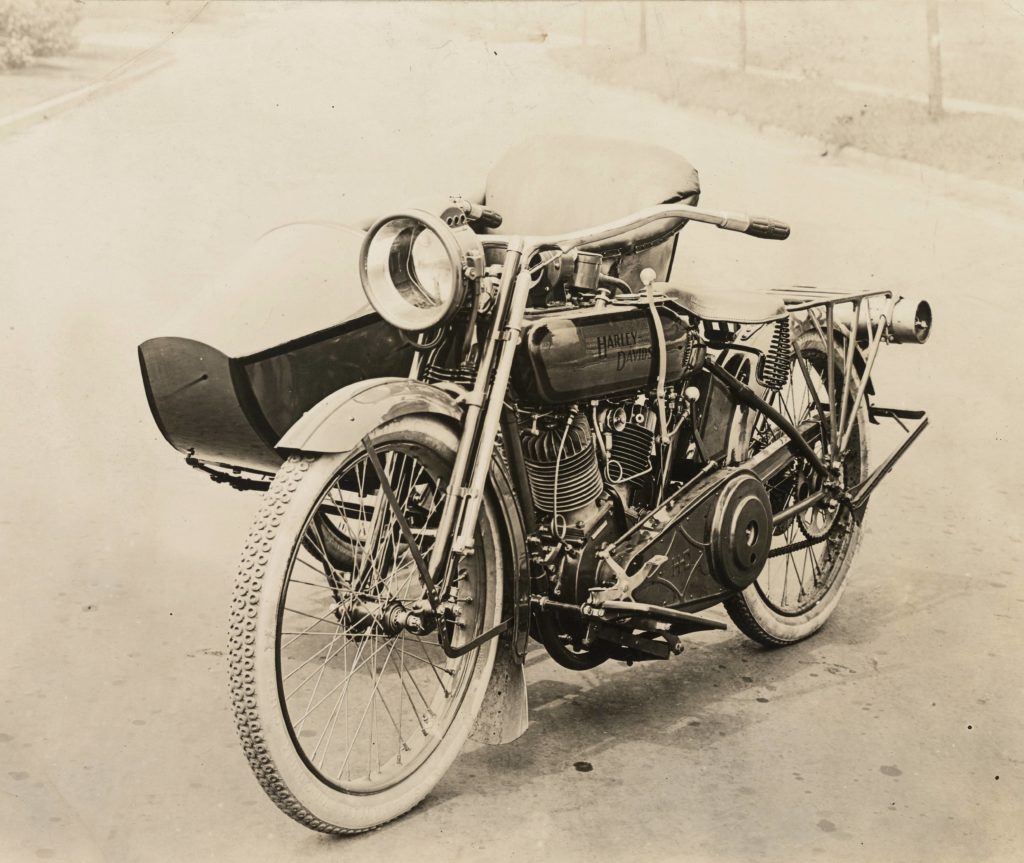

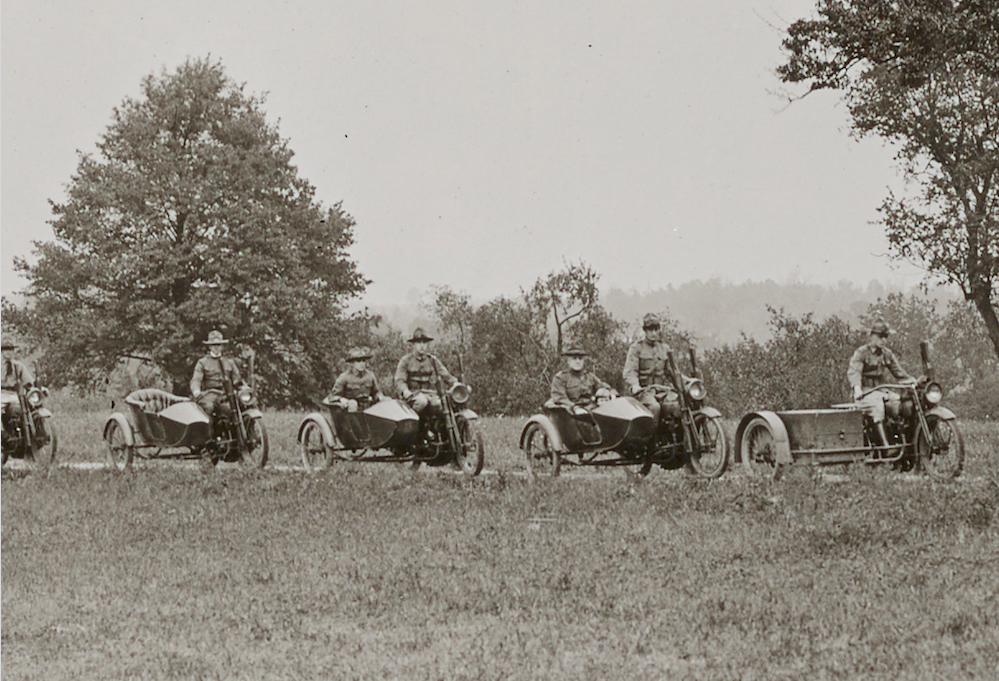

100 Years Ago: Harley-Davidson Military Testing in 1918

When the USA declared war on Germany (although not on the Central Powers) in April 1917, there was an unprecedented scramble to fill the requirements for modern warfare. Among the novelties: motorcycles that were used for messenger duties, or as mobile gun platforms, or even highly mobile (and highly uncomfortable) ambulances. While President Woodrow Wilson had expanded the navy in the 'Teens to protect the supply chain selling American-made goods to the British and French, he hadn't built up ground or air forces, thinking this would deter the USA from joining the war that had already cost millions of lives.

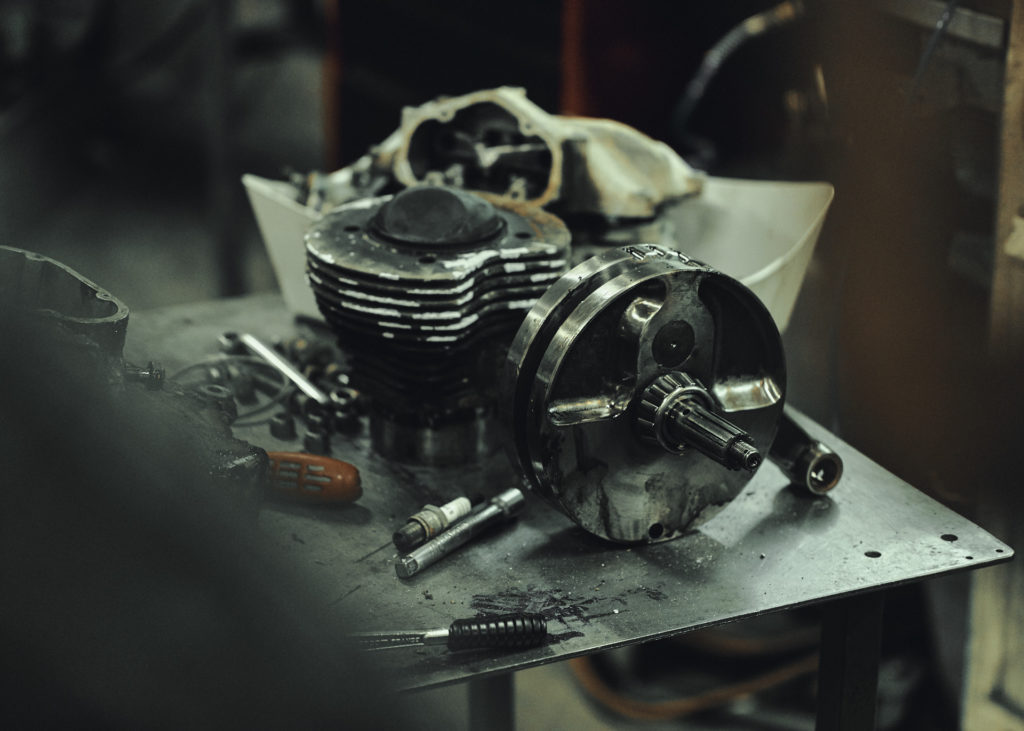

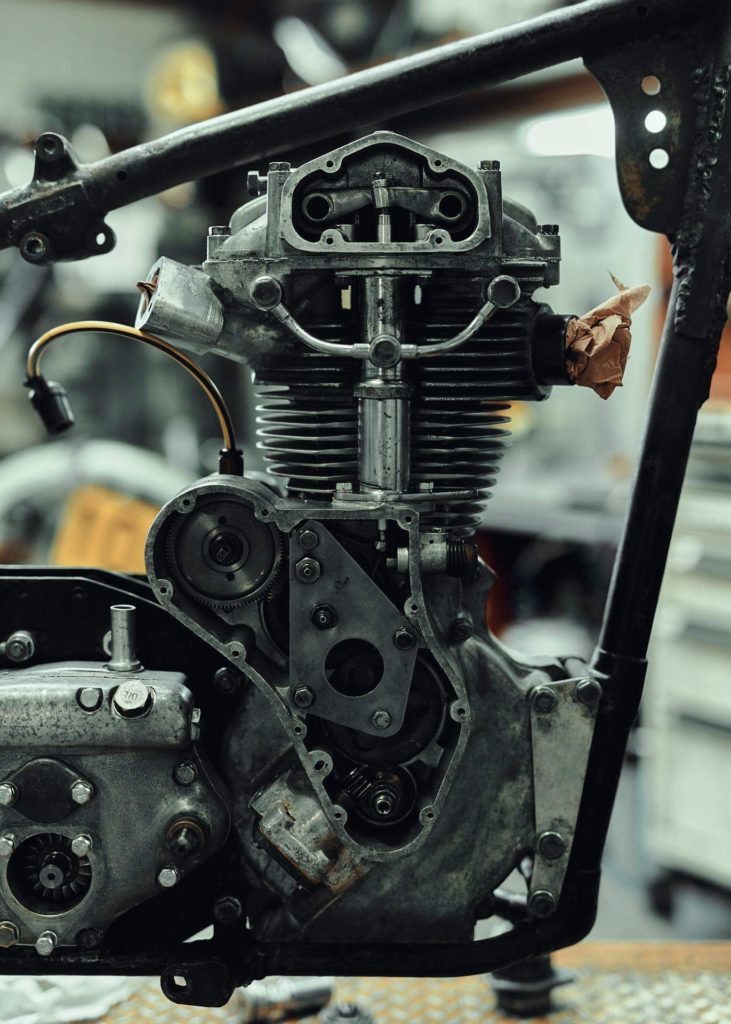

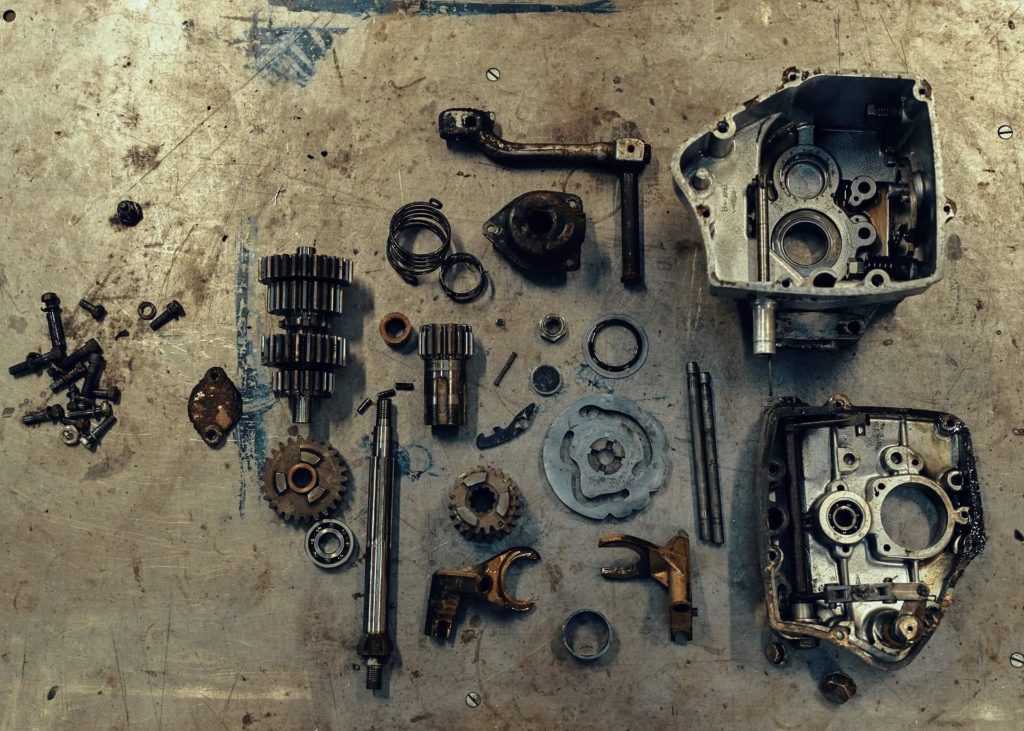

Reviving a Racer: Atelier Chatokine by Laurent Nivalle

Esteemed French photographer (and Vintagent Contributor) Laurent Nivalle visited the workshop of Atelier Chatokhine in the village of Ouerray recently, to document the resurrection of the Richard Vincent racing Velocette MSS. This historic machine was raced in Southern California in the mid-1960s by Richard, who lived in Santa Barbara and was a surfer, photographer, filmmaker, pilot, and motorcycle racer in the golden days of the 'Endless Summer' generation. We documented some of Richard's story on The Vintagent with our short film 'The Ended Summer', by David Martinez, and Richard's motorcycles and surfboards were exhibited at Wheels&Waves California in 2016, and Wheels&Waves France in 2017.

The Motorcycle is 200 Years Old Today?

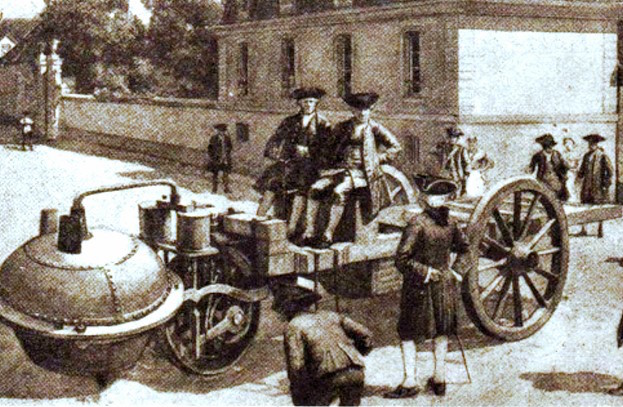

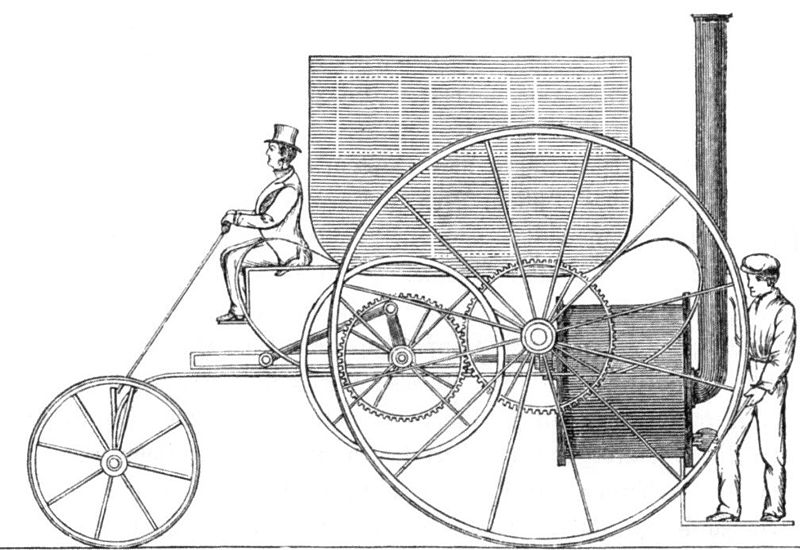

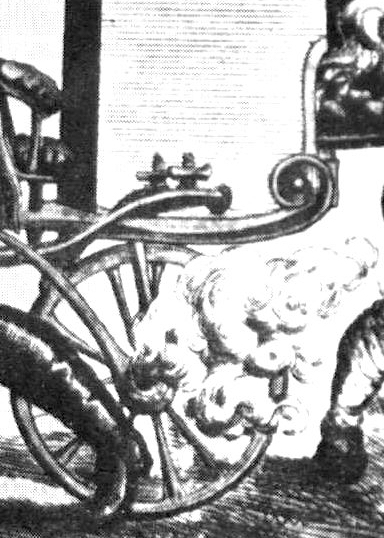

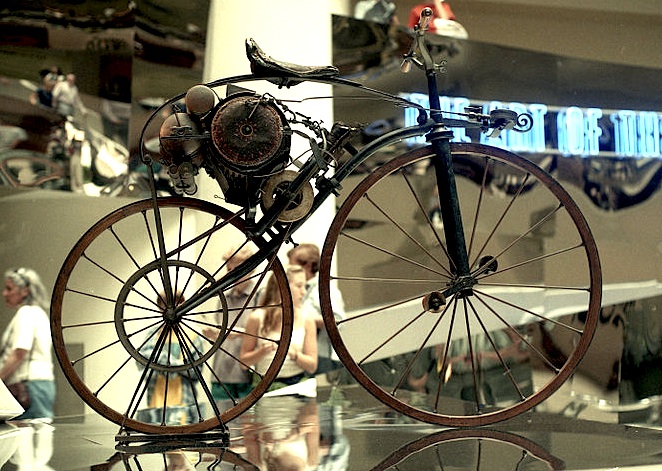

The first known depiction of a motorcycle celebrates a demonstration of a steam-powered 'drais' (pedal-less bicycle) in the Luxembourg Gardens of Paris, on April 3, 1818. The contraption, dubbed a Vélocipédraisiavaporianna (steam-powered drais), is depicted in a period lithograph, with minimal text explanation, nor even the name of its German builder. Some historians consider the lithograph a joke, as no other documentation of this event has been unearthed to date, but the context of the drawing, and its technical details, suggest it was certainly possible, and it would not have been the first steam-powered vehicle in Paris in that era.

What's widely acknowledged as the world's first self-propelled vehicle was a steam trike built in 1770. Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot built his 'Fardier a vapeur' (steam cart) after several years of experiments with models, including a smaller version of his Fardier built in 1769 as a proof-of-concept. The question of how to translate the pushing power of a steam jet into forward motion had yet to be addressed, even though the power of steam to move objects was first described by Vitruvius in the 1st Century BC. It's generally agreed that Cugnot was the first to successfully translate the power of steam into mechanical motion, with power enough to carry a passenger. In the 1700s and 1800s, France was truly the land of invention, where the first internal-combustion automobile was built in 1807 by Isaac De Rivaz, and the first internal-combustion boat demonstrated to Napoléon that same year, built by Nicephore Niépce, who was also the inventor of the first fixed photographic process (the Daguerreotype) in 1837. Thus, France is the place one would most likely find a depiction of the first motorcycle, as it was the hotbed of vehicular invention. Of course, an artist might also make fun of this situation!

Cugnot's original Fardier still exists, and can be visited at the Musée des Arts et Metiers in Paris, where it has sat since 1800. The Revolutionary government of France created this museum to science in 1794 in a deconsecrated church, as part of their rejection of religious dogma in favor of scientific fact in the Age of Enlightenment. The French calendar was changed to a decimal system in 1793 (which lasted 12 years), and the 'metric' system of measurements adopted in 1799, which has since become the system of measures used worldwide. The transfer of the Cugnot's fardier from the National Armory to the Musée in 1800 was part of a continued celebration of science in Revolutionary France that continued under Napoléon when he assumed power in 1804, and beyond. While the anti-monarchist Revolutionary government stripped Cugnot of the royal pension granted him by Louis XV in 1772, Napoléon restored his reputation and pension before Cugnot died in 1804. A replica of Cugnot's Fardier was built in 2010, and I was privileged to witness it in action that year in Avignon, as seen below in my YouTube video.

Thus, steam-powered vehicles had been around for 50 years before our steam drais supposedly appeared, and the technical details on translating steam from a boiler into rotating wheels was understood, even if no particular system was settled on. Cugnot used an inelegant ratchet system in 1769, although the steam piston engine had been invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and vastly improved by James Watt in 1781. Watt's engine design was efficient and kept the steam in a closed system, which meant a motor could be run reliably without constant attention or constantly varying steam pressure; his design formed the basis of reliable power and electricity supplies which formed the heart of the Industrial Revolution.

So, was a crude steam-powered motorcycle built in 1818? The lithograph notes that the 'startling machine' was intended to replace horses, while mocking its builder's claim of speed, reliability, acceleration, lightness, etc. Obviously this machine was nowhere near a replacement for the horse, but the reference has significance for that historical moment, at the end of a 3-year stretch of severe climate change brought on by the 1815 eruption of Mt Tamboura in Indonesia. 1816 was the 'year of no summer', a time of famine in Europe and all of the Northern Hemisphere, as the dust from Tamboura added to dust from the 1814 eruption of Mt Mayon in the Philippines, creating an aerosolized sulfate layer in the stratosphere. The result in Western Europe was food riots in 1816 and '17, and a significant decrease in the horse population as they became targets for food. Thus the 'en cas de mortalité des chevaux' (in case of the death of horses) was a real fear, and a German inventor would be motivated to use current technology to 'remplacer' (replace) the horse.

Was the lithograph a joke? It's impossible to say for certain today: there's enough detail in the drawing to suggest it was a real machine, or that the artist had enough familiarity with steam power to include petcock valves and steam pipes along with the burner/boiler on the machine. No indication is made on how the steam was translated to forward motion; small turbines in the wheel hubs? We simply don't know. But it's certain that, at least, the idea of the motorcycle as a powered two-wheeler emerged in 1818. The first known, and still extant, steam motorcycles were built nearly simultaneous in both Paris and Boston in 1869, by Louis-Guillame Perreaux and Sylvester H. Roper, respectively. So, is the motorcycle 200 years old today, or 150 years old next year?

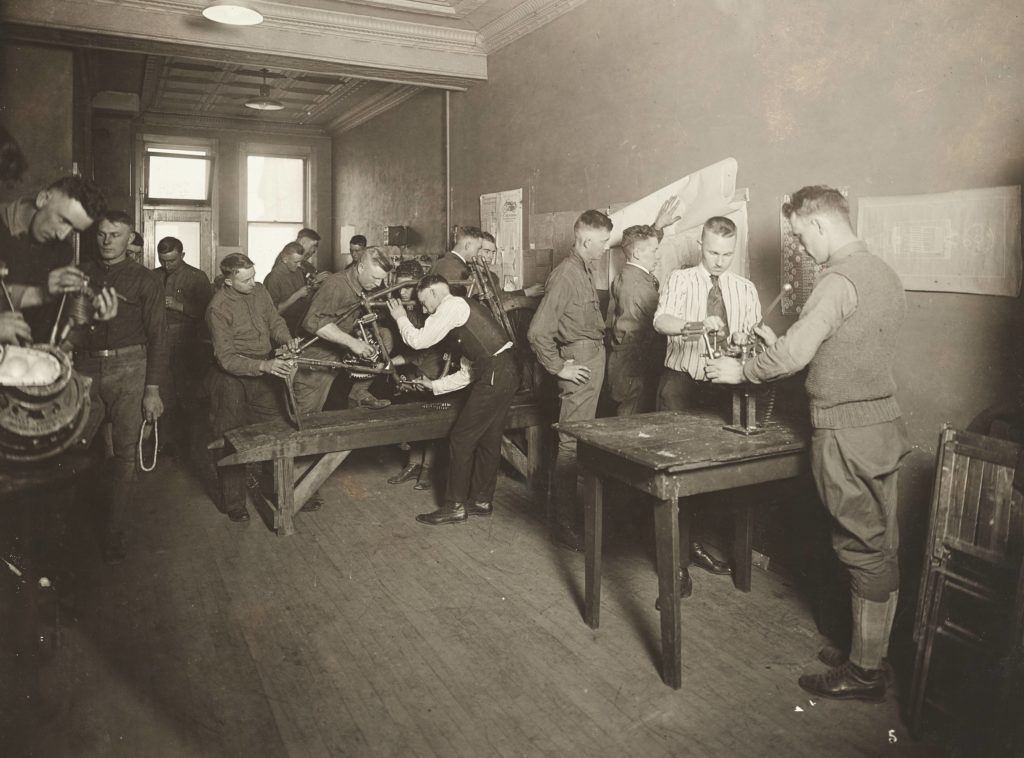

100 Years Ago: Harley-Davidson Training Schools in 1918

The greatest innovation in World War 1 among the 'Big 3' motorcycle companies trying to secure government contracts, was the offer by Harley-Davidson to provide training schools to military mechanics. The schools would instruct recruits on how to repair motorcycles in the field and in military workshops...and of course the demonstrators they provided to work with were Harley-Davidsons! It was not only brilliant marketing to the military, training was also truly necessary for maintenance and repair, as military recruits were generally ignorant of mechanical matters, or had never worked on a motorcycle before.

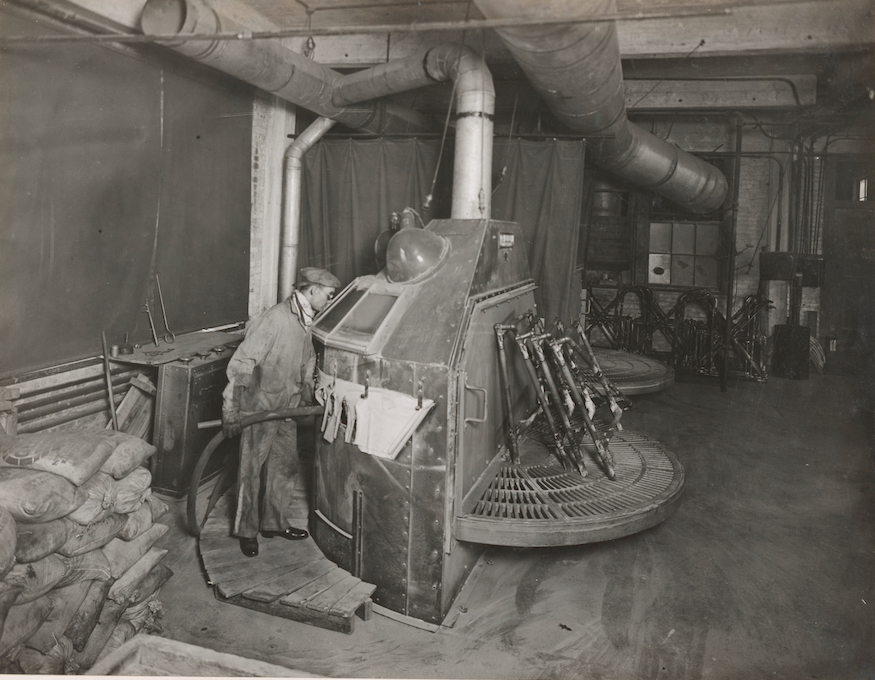

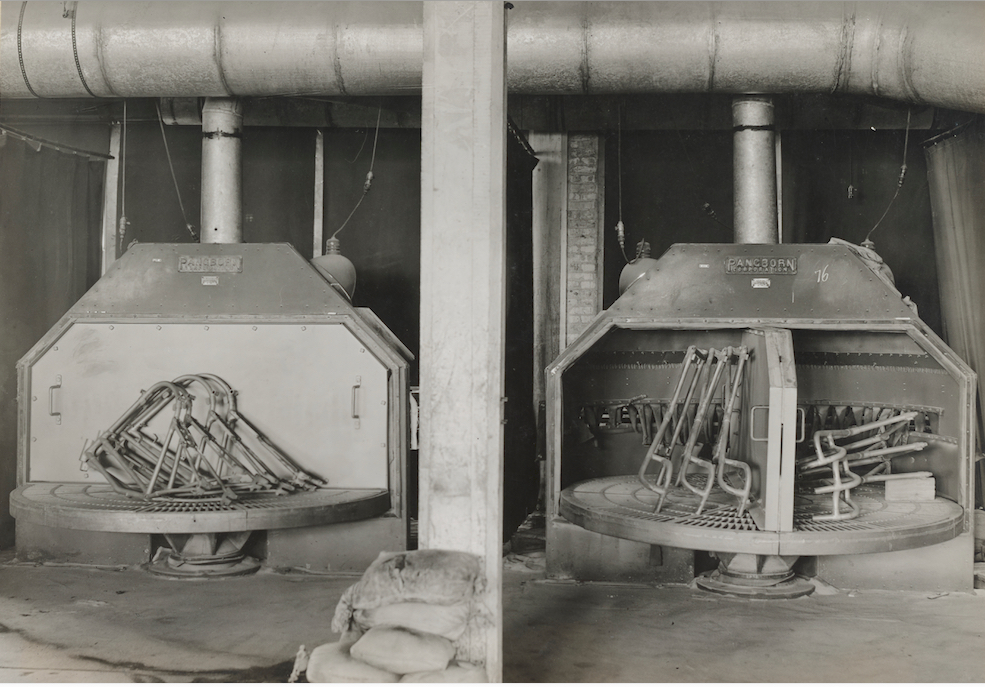

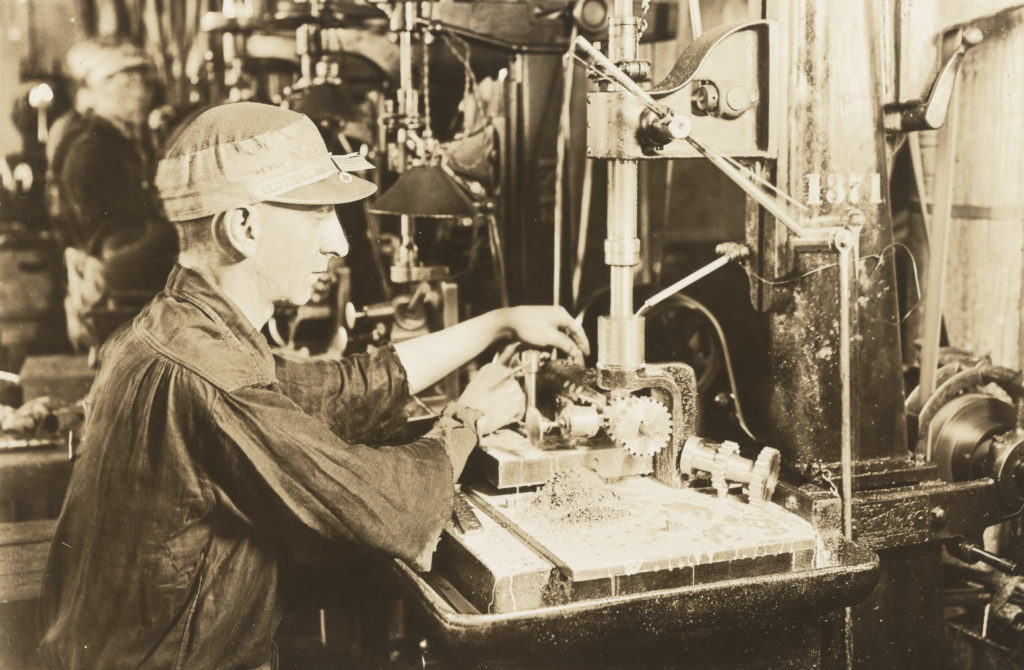

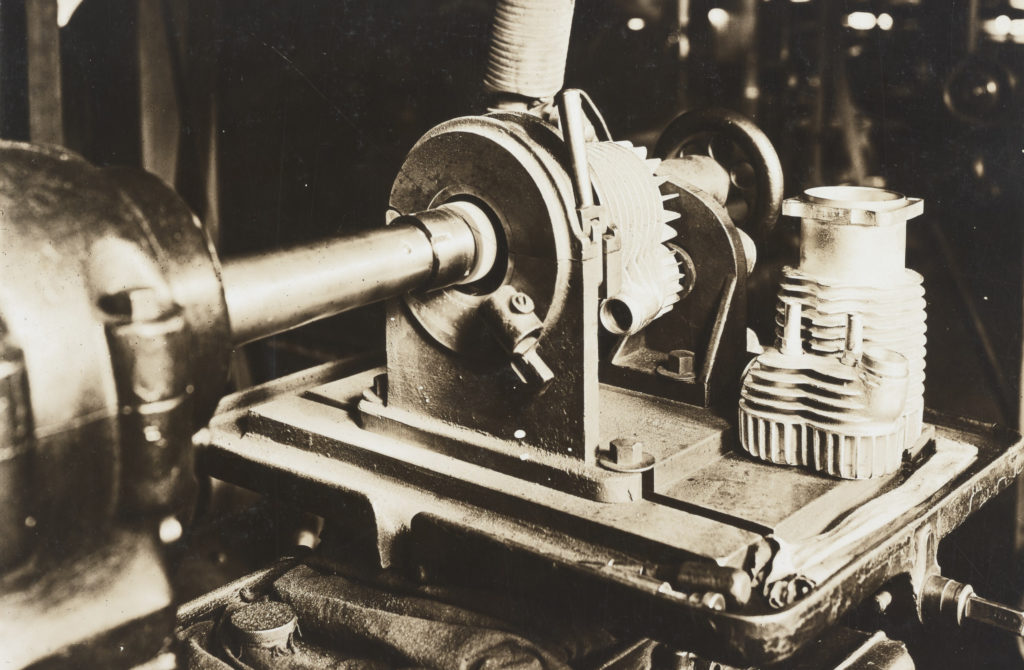

100 Years Ago: Harley-Davidson Manufacturing in 1918

Of the 'Big 3' American motorcycle manufacturers responding to US Military requests for motorcycles, it was Harley-Davidson that gave the matter the most thought. Every manufacturer had a good motorcycle to offer, and none were specialized at the kind of harsh service required by the military. Then again, motorcycling in the USA in 1918 was a pretty rough business, as paved roads only existed in the center of towns, and roads didn't even exist in many parts of the West.

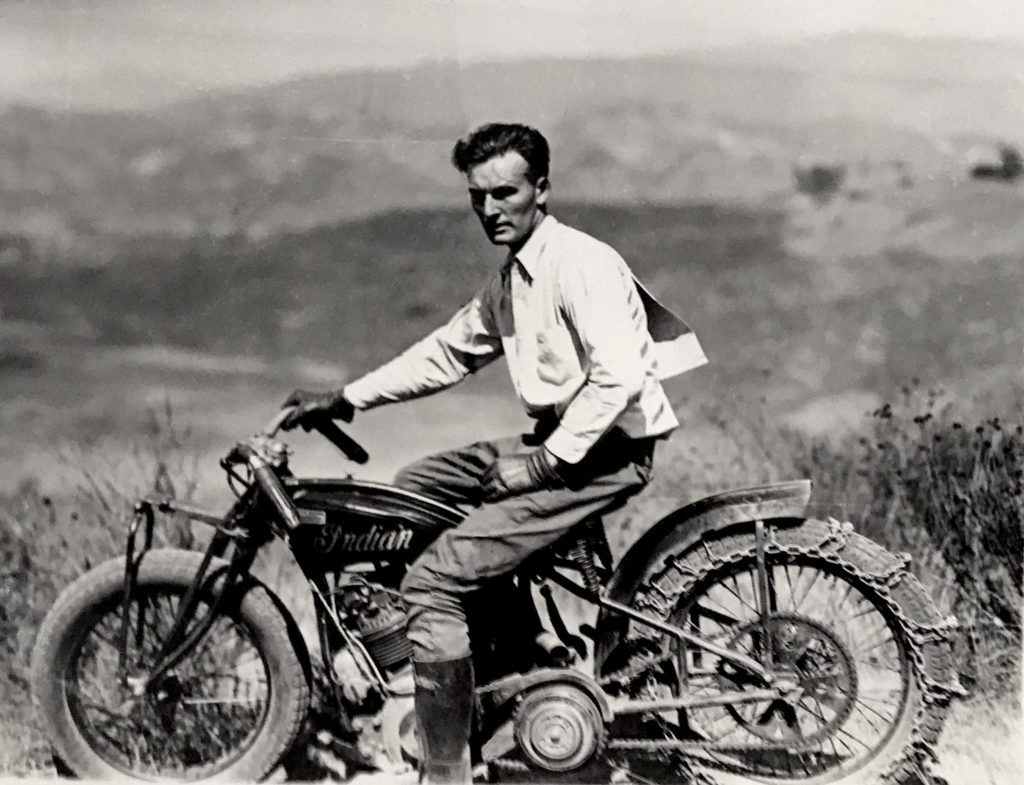

100 Years Ago: Excelsiors in 1918

The response of the US government to the declaration of war against Germany in April 1917 was astonishingly rapid. Virtually overnight, 4 Million men were drafted, and military contracts handed out to every likely contributor to the war effort, including the motorcycle industry. By 1917, after the 'terrible 'Teens' leveled the majority of American motorcycle factories (due to rising material and labor costs), only the Big 3 (Excelsior-Henderson, Indian, and Harley-Davidson) were able to supply motorcycles in large quantities required. Smaller brands also supplied machines (like Cleveland's little two-stroke single) in miniscule quantities.

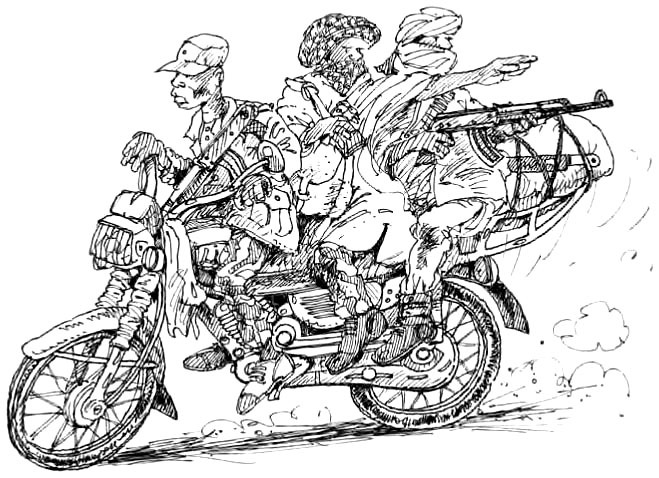

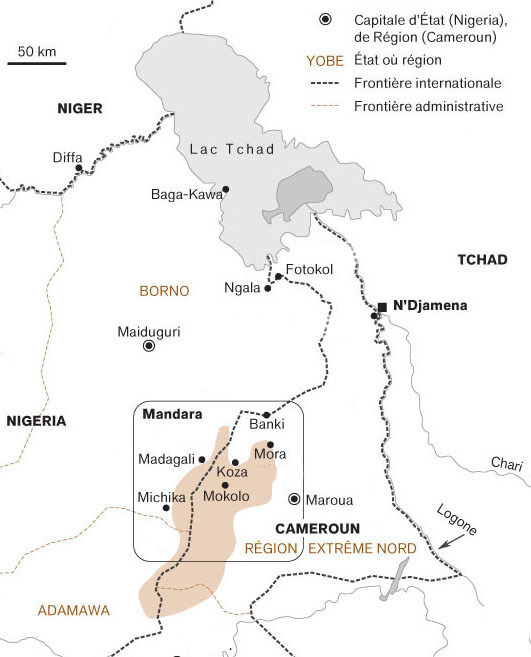

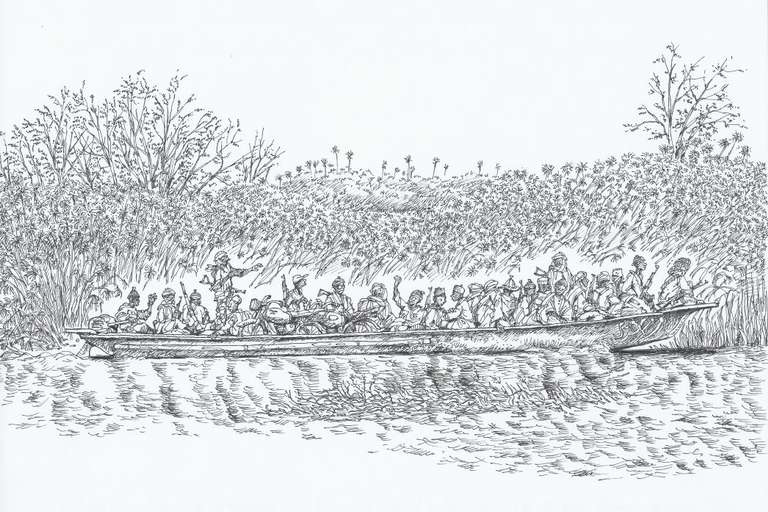

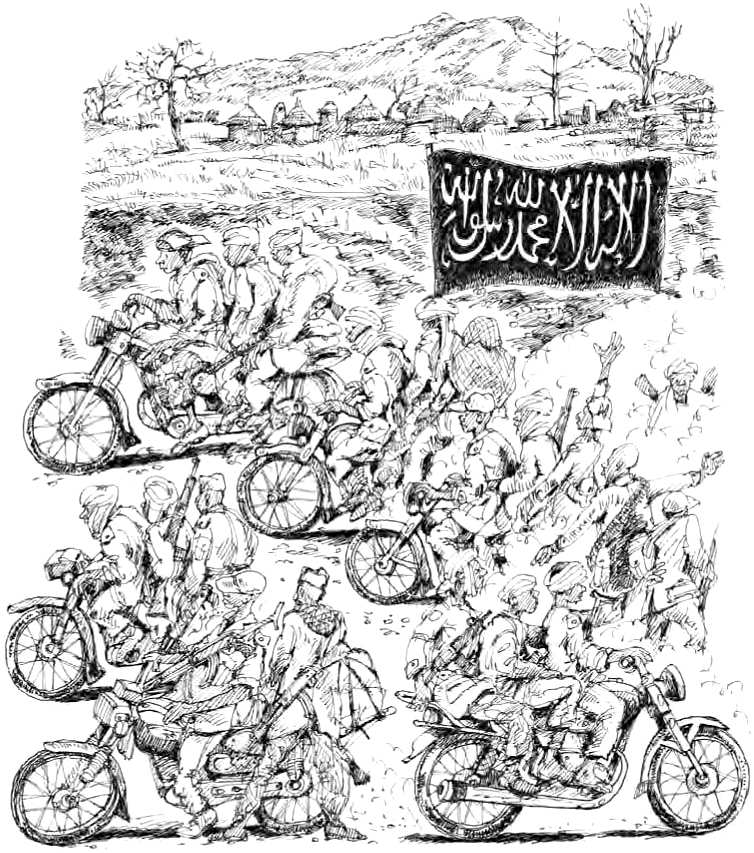

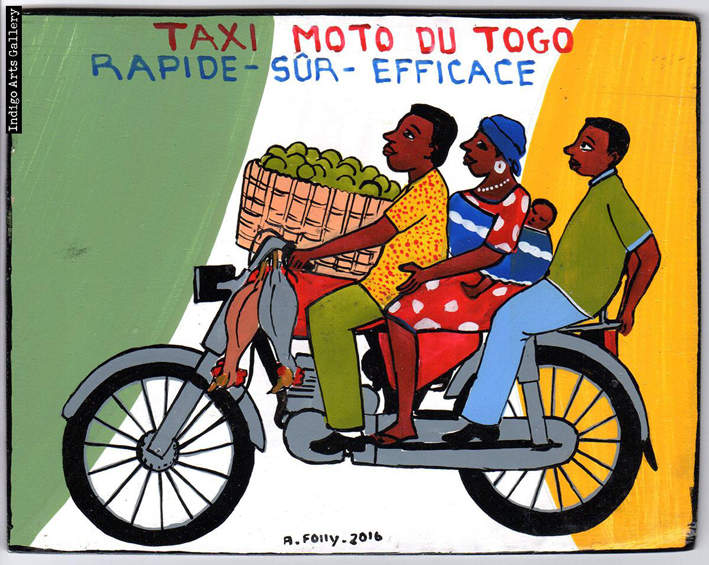

The 'Motorized Cossacks' of Africa

[By Jean Bourdache]

The rapid diffusion of motorcycle transport has positive effects on the lives of Africans, both in urban centers and in the countryside, as noted in our previous article. But the ubiquitous Chinese motorcycle has also increased jihadist's nuisance capabilities, especially the infamous Boko Haram sect. Very active in Nigeria (where it was founded in 2002), Boko's abuses have spilled over to neighboring states of northern Cameroon and Chad. The Mandara Mountains have long been a haven for the Boko Haram bases, from which flash attacks into Cameroon began. The Cameroonian army, backed by Chad, forced direct clashes with the jihadists, who then moved further north to Lake Chad itself.

The Ride: Max Hazan's 'Musket 2'

Every great single-cylinder motorcycle has inspired fantasies of doubling the jugs to make a V-twin. It's a very old story, as both Indian and Harley-Davidson tried it (hello), and plenty of customizers have done the same over the years; there are V-twin Velocettes (the Vulcan), Rudges, and even the odd Norton. Ohio's Aniket Vardhan not only sorted how to make a V-twin Royal Enfield (the Musket) using mostly original parts (barring the crankcases of course), but has series produced the motor for a few lucky customers. Celebrated custom builder Maxwell Hazan of Los Angeles ordered two of the current batch of seven Musket motors, and he's just finished his second Musket custom, as seen in a chance visit to his workshop in downtown LA last week.

Max Hazan rapidly fixed his star in the custom motorcycle firmament, as his design sense is impeccable. Hazan's engineering, on the other hand, is polarizing; the dramatic, clear lines of his 'silver machines' catch they eye, but freak out engineers, who worry about that delicate tubing and its robustness in real-world riding situations. But Hazan does consider tubing strength, and finds clever solutions to the various demands placed on his chassis. He's known to vary the wall thickness of the tubing he uses for frames and forks according to the loads they'll face, so while a part might look unbelievably delicate, it might just weigh a ton, as he's been known to use 1/4" wall thickness at times; the go-to pipe of plumbers!

Hazan is stretching his engineering chops in other areas of the chassis, including clever touches like the combined handshift/clutch lever on the rider's left side, and the dual brake pedals on the right. Those cool elements free the handlebars from clutter, and the Musket 2's bars are admirably clean, with internal twistgrips and metal handgrips giving a nearly flush, curved line from side to side.

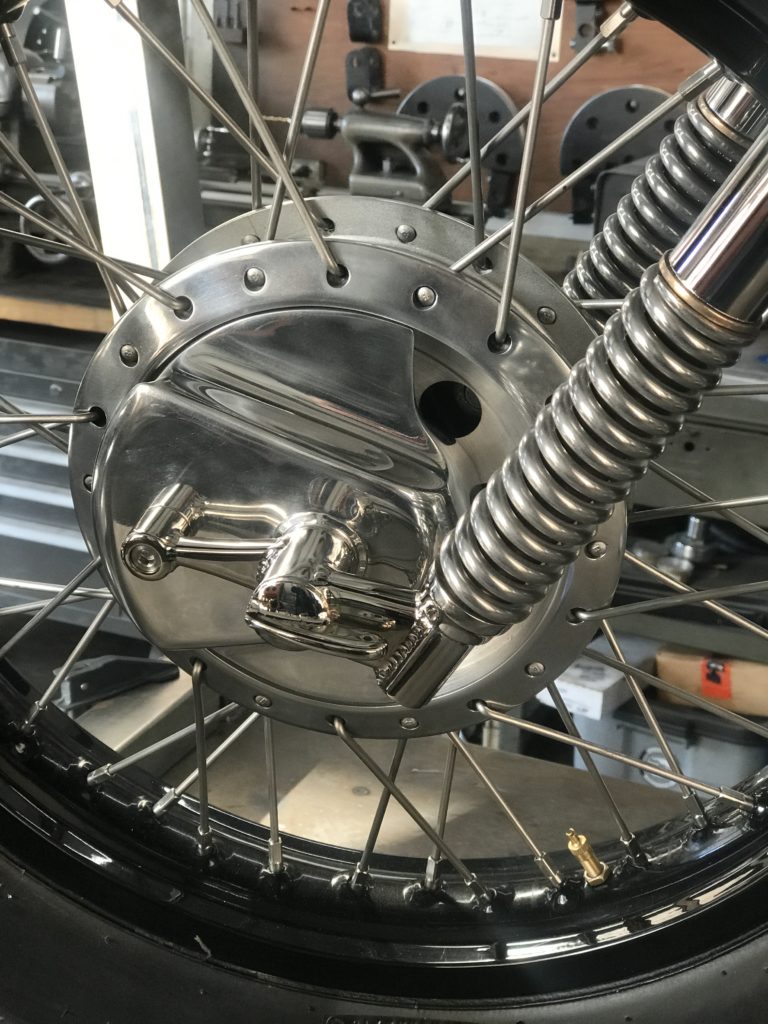

The front forks are Hazan's own design, and 'upside-down' with springs near the axle. The brake plate anchor visually counterbalances the leading-axle bottom fork lug, while it's mirrored on the other side of the hub by a faux brake plate that directs cooling air via a scoop into the brake drum. Very snazzy, and a motorcycle part I've never seen. While the front wheel has a spoked drum, the rear wheel is a solid mag sourced from an automotive catalog. Painted black, it gives a masculine solidity to the back end, and takes a car tire of course, which has become something of a standard for Hazan's builds. The rear brake plate has two clever cams worked by a cable, and the smooth, featureless transition with the brake drum, as well as the lovely forward-facing brake plate anchor, is beautifully balanced.

Hazan is fond of very slim saddles, sometimes with wooden tops; he wanted to explore stretching leather over the aluminum seat frame in this case...but the client wanted wood! Such is the price of having a signature seat. The saddle pivots on its nose and is sprung by a bicycle shock. That compensate's for the rigid frame, which has an uninterrupted line from the rear axle to the headstock, free of distractions like struts or gussets, just clean lines and curved silver tubes. Would the frame hold up to regular usage on LA's rough pavement? No, but this bike isn't built for such use; it's a design exercise that functions, and an artistic statement in the shape of a motorcycle.

The fuel/oil tank is a softened wedge shape and does triple duty, hiding the voltage regulator in its nose as well, with a funnel-shaped porthole directing cool air at its finned body. The scale of the tank matches that of the headlight, making for a unified top deck, and a very basic silhouette for the whole machine: wheels, frame, engine, tank/light. The masses are so very reduced the bike is almost cartoonish, but any further examination beyond the basic outline reveals the seriousness of Hazan's intention. He's following his own star, and this is the kind of machine we can expect. Long may it continue; his work is a welcome respite from same-same production bikes, and the heaps of unclever customs flooding our inbox.

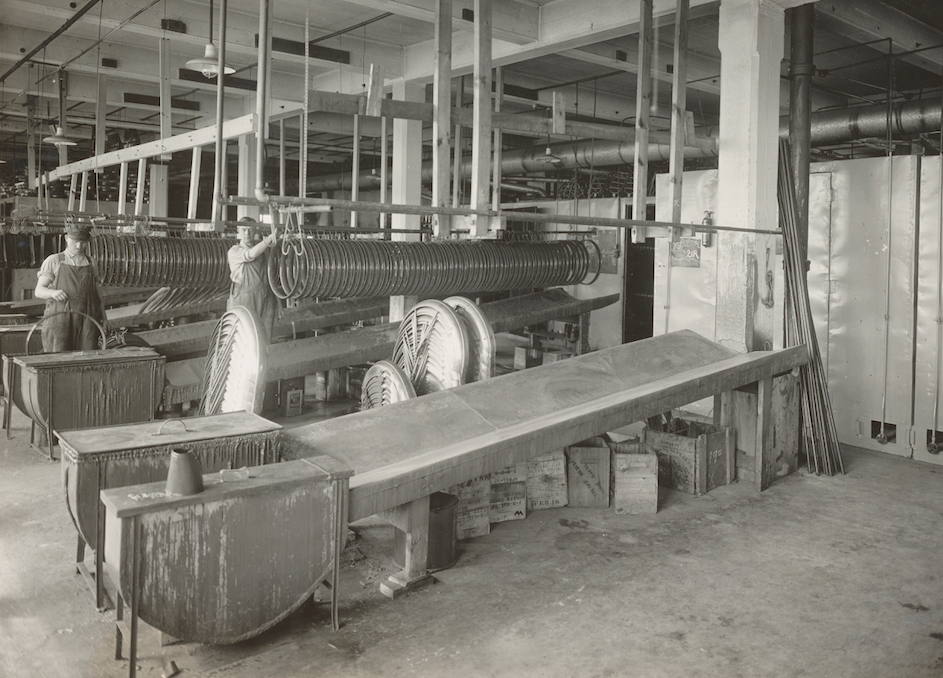

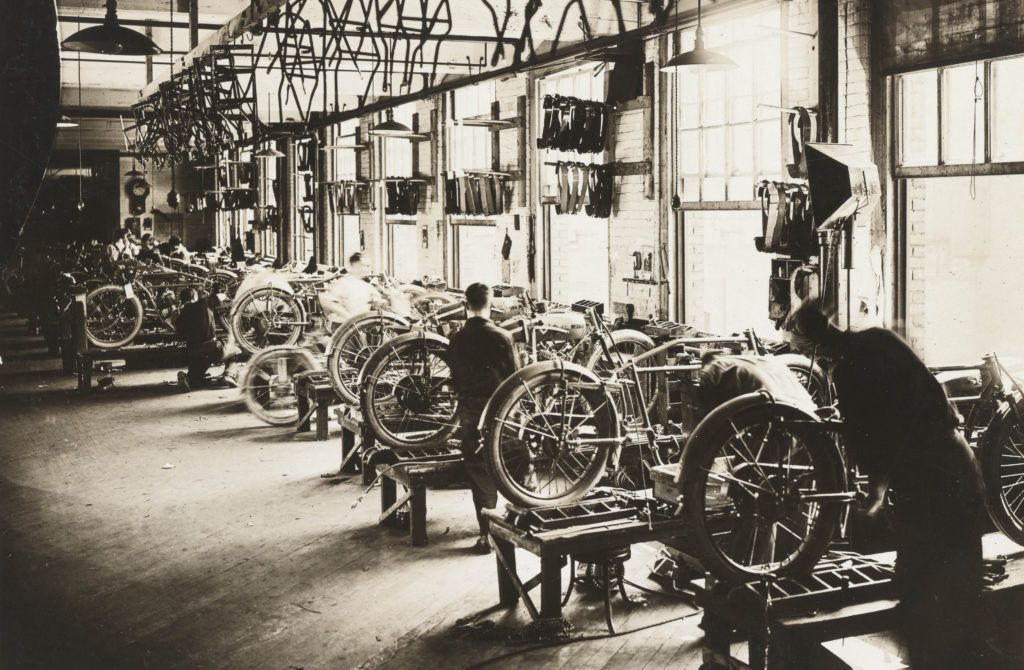

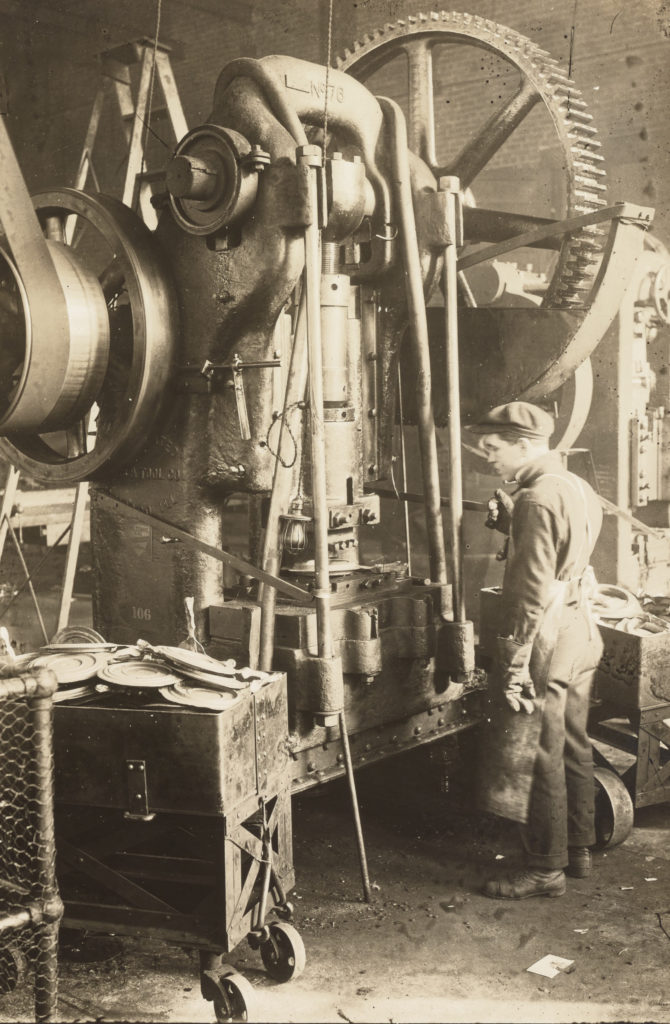

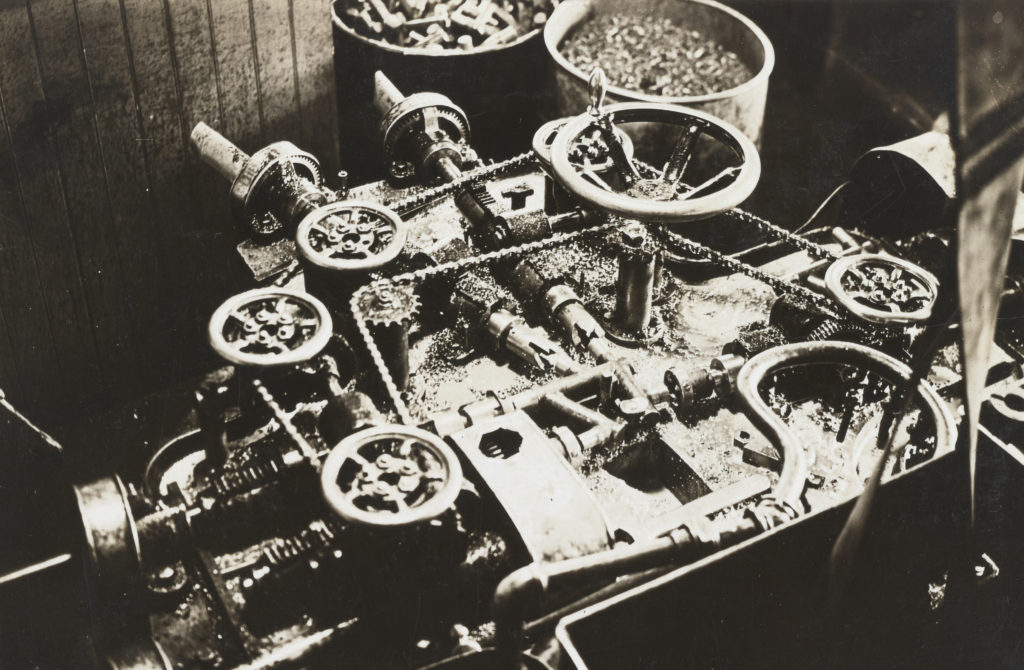

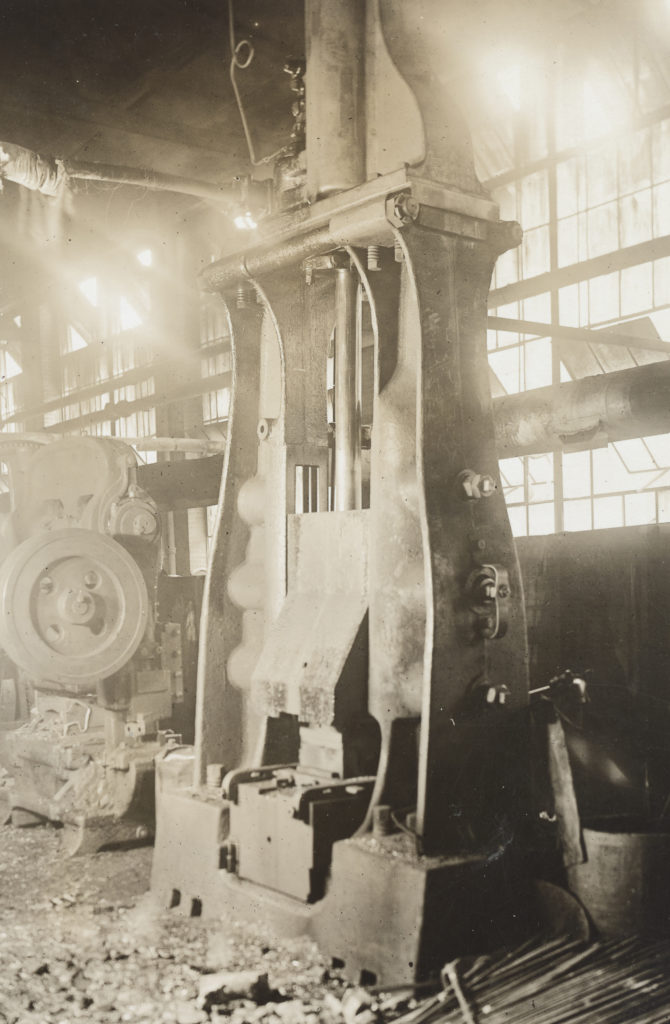

100 Years Ago: Inside the Indian Factory in 1918

[A series of never-before-published photos from the National Archives]

It's difficult to imagine today, but at the dawn of the 20th Century the United States had a tiny military, and its foreign policy was steered by the majority pacifist inclination of its people. Leaders of the 'no war/no military' camp included the Church (especially Protestants), the women's movement, the large farming lobby, and scholars/left-leaning thinkers who feared the USA becoming a militarized state. World War 1 (as it became known after WW2) dramatically changed American politics, priorities, infrastructure, and economy in the ways we see today, with most Protestant sects identified with military boosterism and conservative political activism, and over half the federal budget dedicated to military spending. While the US was 'only' involved in the European war for 20 months, it proved the hinge that pivoted America in a totally new, militarized direction, and boosted the fortunes of motorcycle companies able to secure government contracts to supply military equipment.

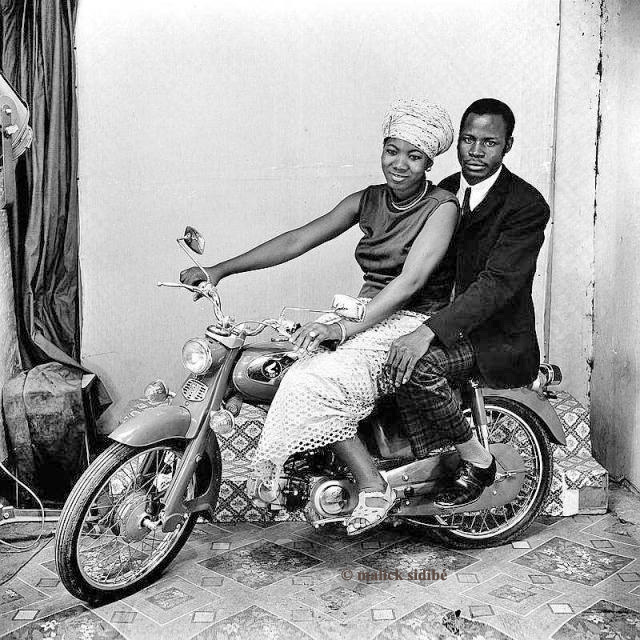

Africa: The Motorcyclists' Continent

When Japanese motorcycles began their conquest of the Western world in the 1960s and 70s, they did so by developing revolutionary technology (after a phase of copying Western designs). The Japanese industry built machines with staggering performance, with engines revving to previously unknown heights, plus 'traffic conveniences' such as turn signals, electric starters, tachometers, double-cam brakes, and no leaks, all at affordable prices. In the past two decades a comparable revolution has occurred at this scale on another continent: Africa.

Only 15% of these machines remain in Togo, according to Giorgio Blundo (director at the School of Higher Studies in Social Sciences - EHSS), who states that "Togo imported from China motorcycles worth $250Million in 2016...with 320 factories and nearly 125 brands included." The list of brands is enormous, ranging from Apsonic to Zongshen, and passing through Bli, Boxer, Chunlan, Dayang, Haojin, Haojue, ZF-KY (or Huawin), Jialing, Lifan, Lingken, Pantera, Qinqi , Rato, Royal, Sonlink, Senke, Volex, and dozens and dozens of other brands that might be named for particular retail outlets.

'Custom Revolution' Exhibit in LA Times

[From the Los Angeles Times, Feb 28, 2018]

'Alt custom' motorcycles to begin one-year exhibit at Petersen Automotive Museum

Strange and wonderful things are coming to the Petersen Automotive Museum.

The Miracle Mile facility, devoted to the art and science of four-wheeled vehicles, will host its first-ever exhibit dedicated to the art of custom motorcycles.

The "Custom Revolution" show will begin a one-year run on April 14. It will include about 25 motorcycles, from 25 different bike builders, representing the best of what's known as alt custom design.

The show will be guest-curated by motorcycle historian Paul d'Orléans, founder of the Vintagent website and respected author of multiple books on motorcycle design and culture.

The exhibit will feature motorcycles that have never been seen together. Many have never been exhibited in a museum space.

The collection will include such iconic machines as Ian Barry's Black Falcon, Mark Atkinson and Mehmet Doruk's BMW Alpha, El Solitario's Petardro, Kingston Custom's White Phantom, Revival Cycle's J63 Ducati, Shinya Kimura's Needle, Roland Sands' 2 Stroke Attack and Medaza Cycles' Rondine.

D'Orleans, who is also a columnist for Cycle World magazine, said he hoped the show would demonstrate the degree to which "outsider" motorcycle design is actually leading the motorcycle industry.

"Every motorcycle history ever written has been driven by factory histories, but in fact it has been the creativity of custom designers and racers that has always been the leading edge," D'Orleans said. "Factories follow, not the other way around."

The Petersen has included some motorcycles in its permanent exhibit since the late 2015 remodel and reopening. Many key Petersen board members, in fact, are keen motorcyclists — including Bruce Meyer and Richard Varner.

Petersen personnel hope attendees drawn by the motorcycle exhibit will be exposed to automotive arts, and that car fans might have their consciousness raised about motorcycles.

"People may forget that the first motorized vehicles were actually motorcycles," said Varner, who is also the Petersen treasurer and chief operating officer of MotoAmerica. "Everything that you love about the automobile probably started as technology on a motorcycle."

"In all our exhibits we try to look for cultural crossover, and this is a phenomenon that melds motorcycles and art and even fine art, as well as engineering and fabrication," Stevens said. "Many of these motorcycles are meant not to be driven but to be contemplated, like an art piece."

Stevens said the seeds of the exhibit were planted in the early 2000s, when he was living in downtown Los Angeles not far from the garage where Ian Barry was building his now-famous Falcon motorcycles.

Stevens' interest in alt custom bikes was further fueled by the website Bikeexif.com, the online bible of motorcycle art, and by a series of books called "The Ride," to which d'Orléans has contributed.

Besides, Stevens said, the art of the alt custom motorcycle is also a homegrown Los Angeles product.

"It's a global phenomenon now, but it has a definite L.A. component," he said. "Some of the most significant bike builders are from here."

D'Orléans, who as author of the book "The Chopper: The Real Story" is considered an authority on that kind of custom motorcycle, said there will be no bikes of that sort at the Petersen show.

"That's not part of the vision for this exhibit," d'Orléans said. "So there won't be anything from Arlen Ness or Jesse James."

Entrance to the exhibit is included with a general admission ticket — $16 for adults, $13 for seniors and students, $8 for children — which can be purchased online or at the museum.

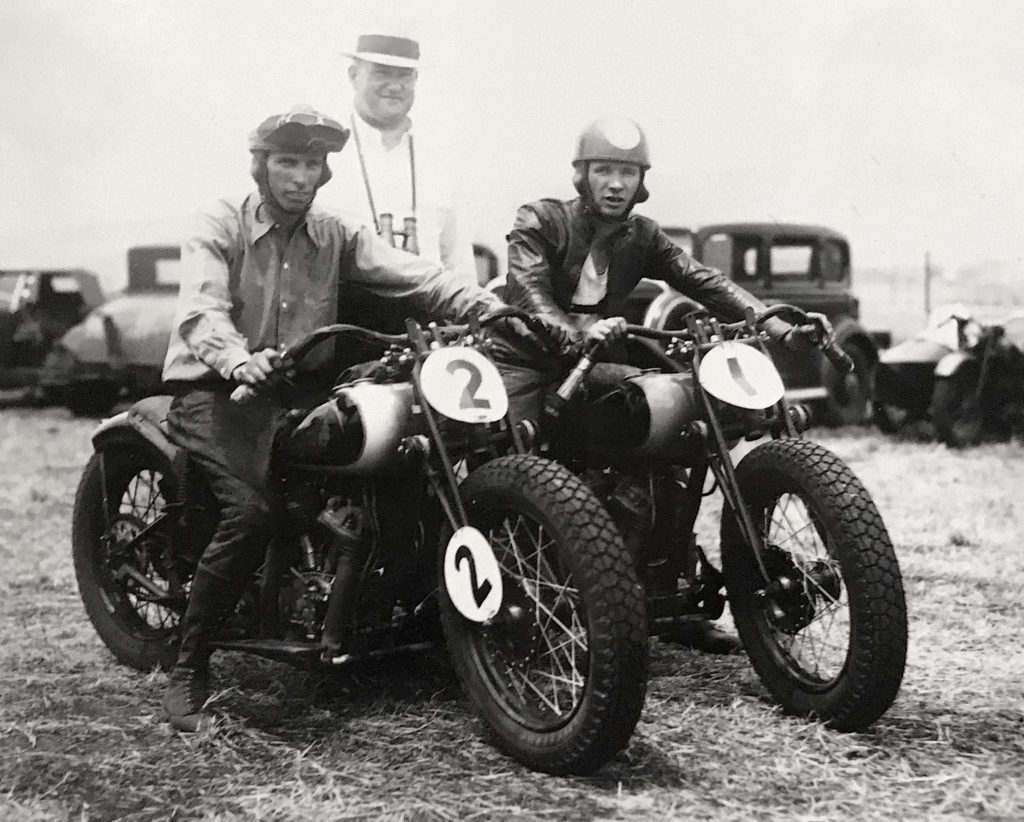

Class C Racing in California: 1935

Dirt: it pretty much defines American motorcycle racing. Powered moto-cycles were first introduced to the USA on bicycle velodromes as pacers, but outside the arena, paved roads were very rare. Only the very center of larger towns had cobblestones, while the rest of the country faded from dirt roads to cart tracks to horse paths, the farther on traveled from a city. Adventurous cross-country riders before the 1920s encountered amazing hazards and an absolute lack of roads in many areas of the Midwest and far West.

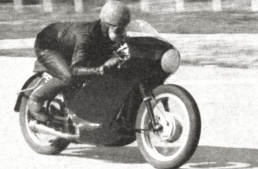

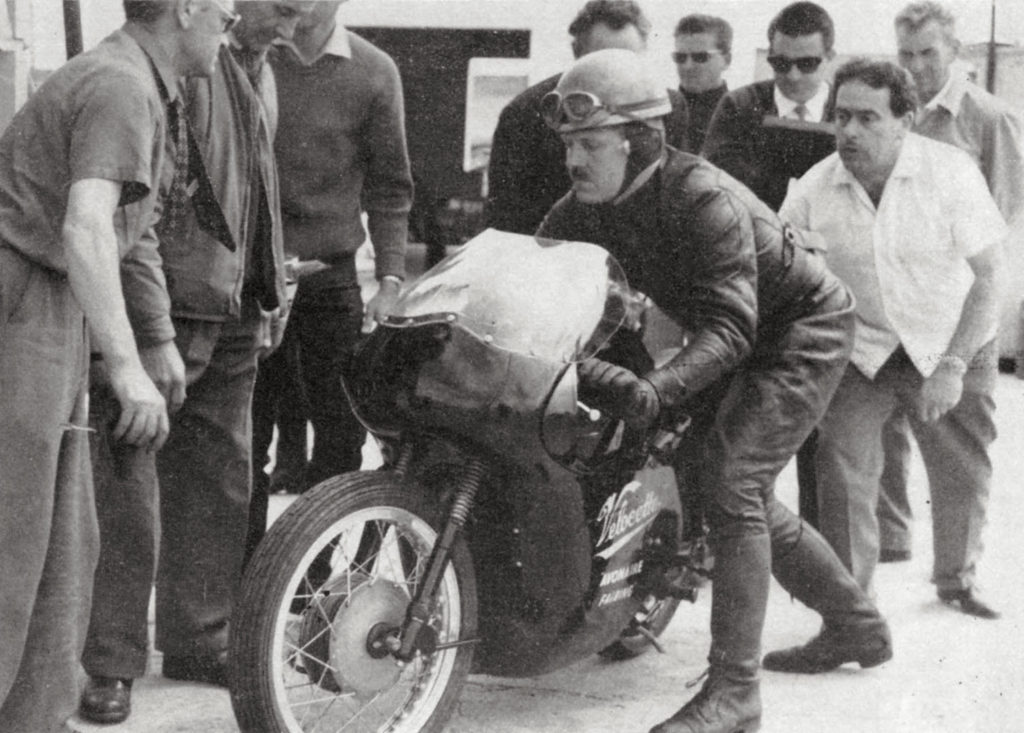

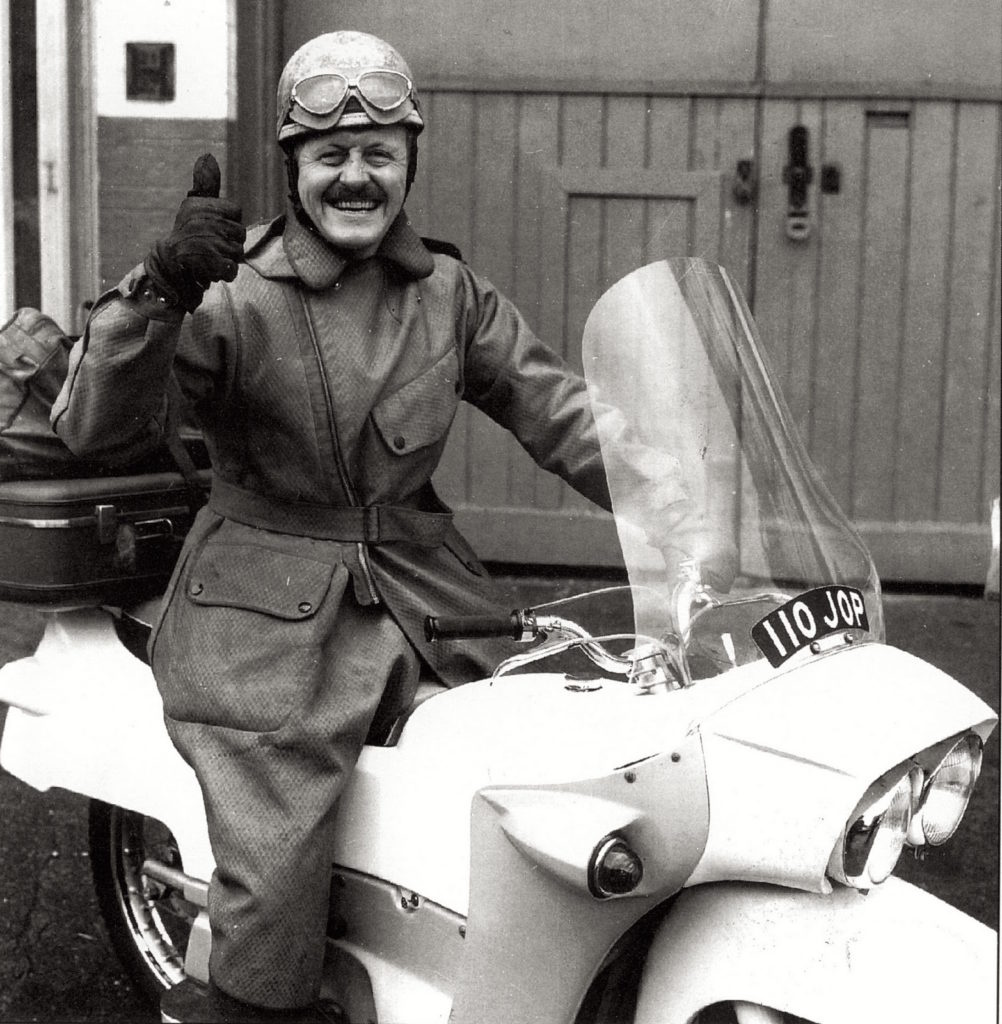

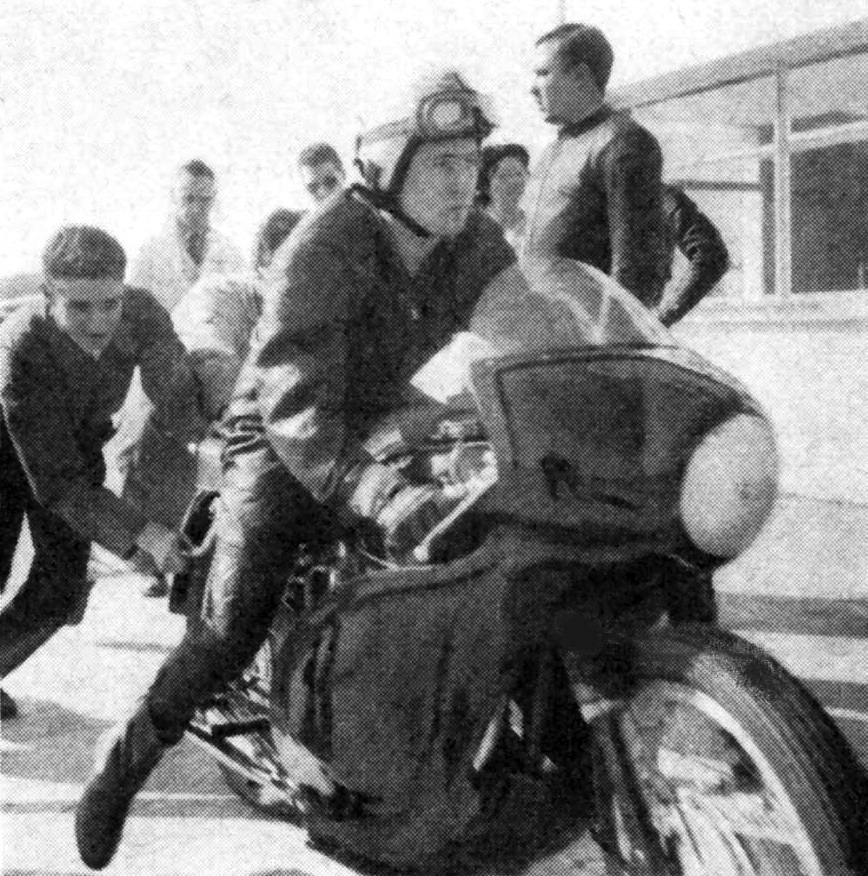

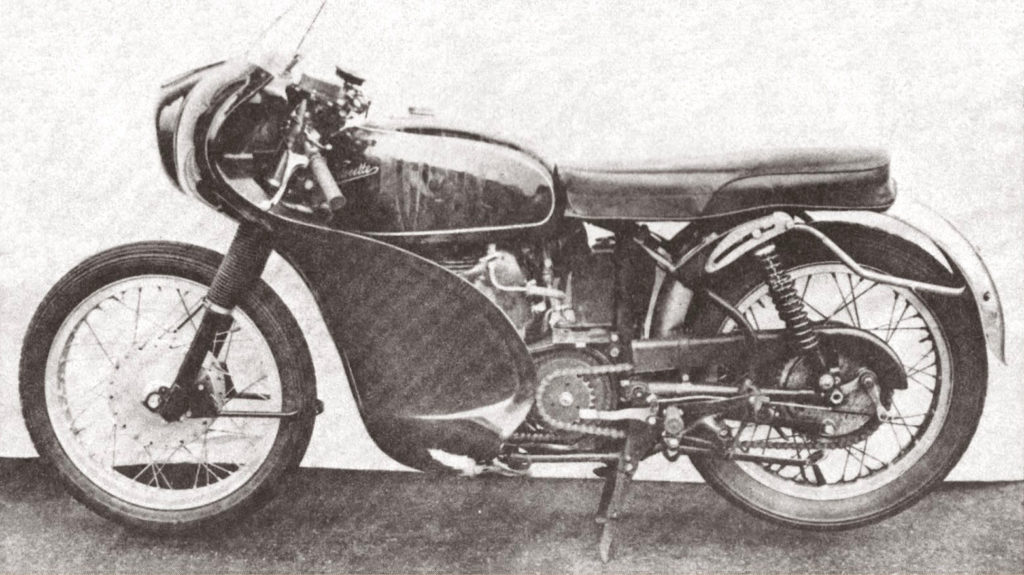

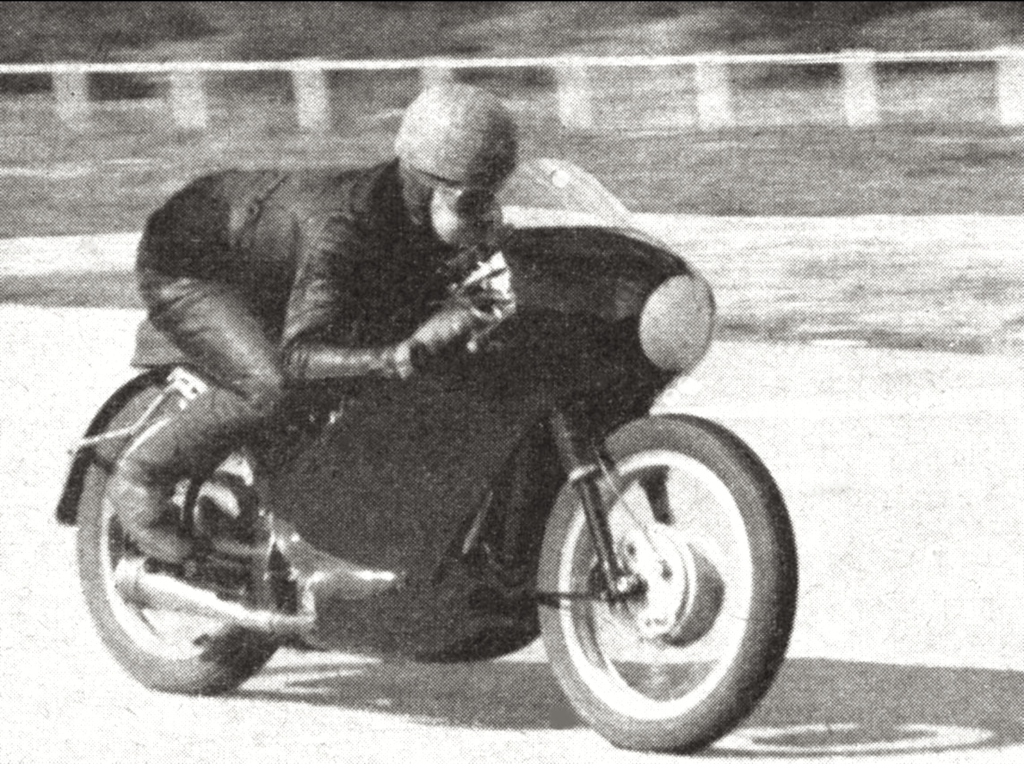

Velocettes at Montlhéry: 24 Hours at 100mph

Nearly 60 years have passed since an international cadre of Velocette enthusiasts braved certain discomfort and actual physical peril, to ride a humble Velocette Venom with no lights around the Montlhéry race track for 24 hours, lapping consistently at 107mph, to average 100.5mph. Many had attempted the 'ton for a day', and some succeeded afterwards, but Velocette was the first to do it, and the record still stands for a 500cc machine, set half a century ago, on March 18th/19th, 1961.

The attempt was set in motion by Velocette managing director Bertie Goodman. Veloce Ltd were a small, family-owned company with a peerless reputation for quality machines, and an excellent racing pedigree. Unlike the Board of nearly every other motorcycle manufacturer, the helmsmen (and women) of Veloce were daily riders of their own machinery, and enthusiastic supporters of racing, to the extent of participating in record runs and even the occasional international-level road race. For example, during his stint as Sales Director, Bertie placed 3rd in the 1947 Ulster GP, and his son Peter had significant success in racing as well.

As Managing Director from the 1950s onwards, after the death of his father Percy Goodman, 'Mister Bertram' (as factory employees called him) took special pleasure in speed-testing the company products at the MIRA test-track, which he insisted helped keep his weight down! Such testing proved excellent for revealing faults, and Velocette production models were renowned for their mechanical reliability and excellent handling.

Their nearly standard 'Venom' 500cc model had been very carefully assembled, but was not highly tuned. Goodman insisted using time-proven production parts meant less likelihood of component failure, so the record-breaker Venom differed from standard only in the addition of a GP racing carburetor, megaphone exhaust, and production prototype fairing, made by Doug Mitchenall, a friend of the Goodman family, and manufacturer of Avon Fairings (and the beautiful bodywork on Rickman motocrossers). Much was removed from the Venom though! The front mudguard, battery, lights, speedometer, number plate, headlamp cowl, primary chain cases, etc, were all removed, probably 50lbs of extraneous metal.

Building the record-breaker Venom took 5 months, as the Veloce race shop had closed 8 years prior, after taking 2 World Championships and countless Isle of Man and GP victories, in a bid for the tiny, family-run company to focus on their production roadsters. When the bike was completed, Bertie Goodman tested it at MIRA for 14 hours at absolutely full throttle, averaging nearly 110mph. The engine was never internally inspected or disassembled during or after testing; that means it ran 1400 miles at full bore, before the record attempt had even begun.

Management of the record attempt, including sponsorship deals and track arrangements, was the job of Georges Monneret. As the Montlhéry circuit had no lights, the 12 hours of night riding were illuminated by 55 Marchal car headlamps connected to batteries! Rider testing - to determine team members - was carried out the night before the record attempt; if you didn't have the 'bottle' to keep the throttle right at the stop, you were out! The team thus consisted of Bertie Goodman, Bruce Main-Smith, Georges and Pierre Monneret, Pierre Cherrier, Alain Dagan, André Jacquier-Bret, and Robert Leconte. While Bertie Goodman was a relative 'oldster' at 42, Georges Monneret was 55 at the time... and of course, these two old dogs were among the most consistent and fastest of the attempt.

Night riding at 107mph through stroboscopic bands of light and dark proved psychologically demanding in ways the riders could not have anticipated; hallucinations, hypnosis, and phantom 'fog' beset every rider, and those with steely temperaments (Goodman, Dagan, and the Monnerets) shouldered the heaviest riding burdens. The bumps were awful, but the Velo steered as they all do, "taut, waggle-free, 100% safe" said BruceMain-Smith, in his epic writeup of the event. He wrote "I am genuinely frightened...punishment from the bumps is awful...my nose and mouth run, onto the chin pad to which I press my head to keep it behind the screen...it seems an eternity...the noise from the megaphone chases me round the track like a wild beast...after 60 laps I know it would sabotage the attempt if I continued. I come in..." He finds motivation to continue, thinking first of his Country, then his readers, and finally - that he was being paid!

The rough hours of the day passed into evening, and with them the 12-hour record at 104.6mph. Worth celebrating, but the grim reality of constant pounding and a further 12 hours' riding meant no champagne. The nightmare hours hammered onward, punctuated only by fuel stops and rider changes, at times after only 15 minutes, as younger riders complained of blurred vision and fatigue. The older riders (Goodman, Monneret) dutifully fulfilled every one-hour stint, while young Dagan, the fastest of them all, was first to leap onto the saddle and revive the average speed when others flagged or surrendered. By morning's first light, he made the final push, bringing the Velo over the timing line for the last time. All were exhausted, cold, and ready for sleep! Yet, for 2400 miles and a road average of 107mph, the Velo never skipped a beat, and gave a remarkable 37mpg, ridden flat out. When the engine was finally opened for FIM inspection, after 3800 miles of 100+mph riding, it was found to be in perfect condition.

Two-Wheeled Icons of the 1980s

Each decade of the 20th Century produced its icons of design; products that distilled the vibe of an era into 3 dimensions. These cars, motorcycles, armoires and toasters were rarely the top sellers of their time, and often outright shunned by consumers, but this only pushed them into the realm of Collector's Items - death for production, but life for connoisseurs. In 2018, we're having a moment of increasing appreciation for 1980s design, as witnessed by rapidly escalating prices for two of the motorcycles included in this list (the Honda Motocompo and Vetter Mystery Ship), and a flurry of activity on social media appreciating what was formerly derided and discarded. It's the old story, the bell curve of collectability from nadir to zenith, and the wave is just forming for a price peak on the best of 1980s motorcycle design. These bikes aren't the best sellers, or the biggest winners, or even the best looking, but they're definitely design icons and points of reference for the motorcycle industry of the 1980s. So, in chronological order...

1980 Vetter Mystery Ship

Craig Vetter had an outsize influence in motorcycling, beyond his personal fame or fortune, although he's had plenty of both. While the motorcycles he designed for production were strictly limited-edition specials (including the 1973 Triumph X75 Hurricane - you'll find that on our upcoming 1970s Design list!), his Windjammer fairing and hard bags were seemingly everywhere in the 1970s and '80s, and pushed the OEM manufacturers to include streamlined wind protection on their production touring motorcycles.

1980 Target Design ED-1

1981 Honda Motocompo NCZ 50

Nevertheless, the design of the Motocompo is ingenous, and perhaps the only real inheritor of the 'Motosacoche' concept, being truly a 'moto in(to) a suitcase'! The design is impeccably 1980s, with its flush, integrated head- and taillamps, retractable everything, and terrific graphics. Best of all, the City/Motocompo advertising campaign was launched with the British ska band Madness providing entertainment and music for the ad. It, too, is a highlight of 1980s design!

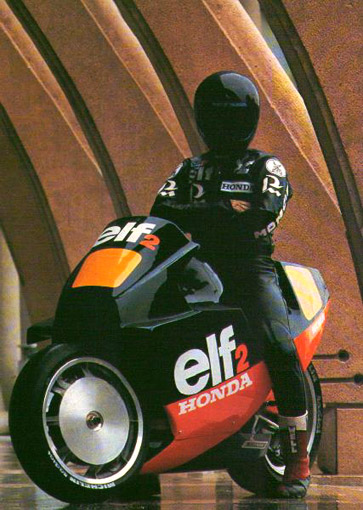

1981-6 Honda ELF racers

1984 Fantic Sprinter

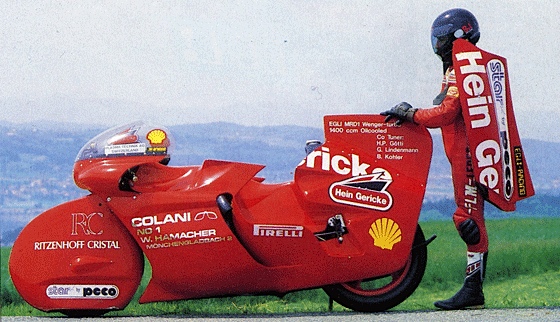

1986 Colani Egli MRD-1

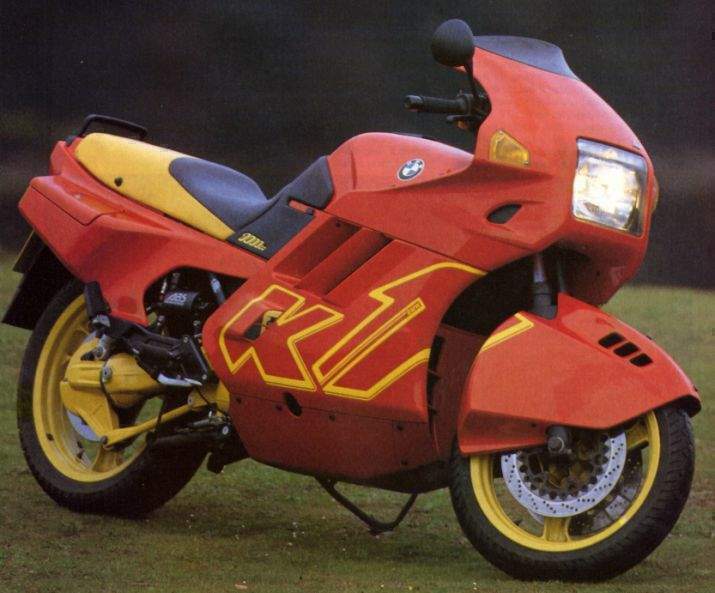

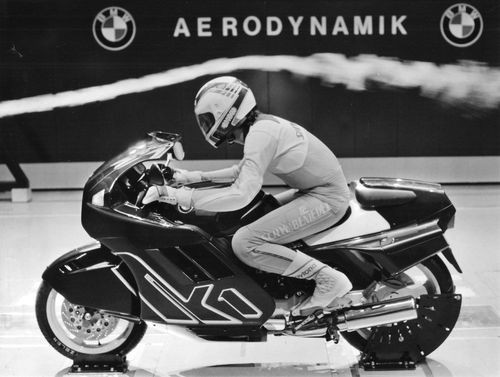

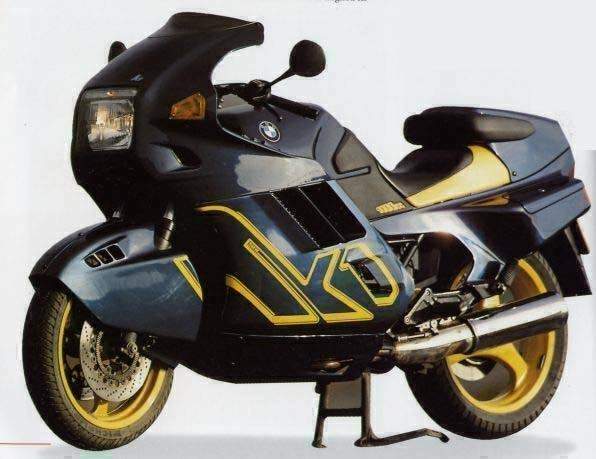

1988 BMW K-1

The Current: Harley-Davidson - 'E-Bike in 18 Months'

With American motorcycle sales dropping 50% in the past 10 years, and Millenials more interested in swiping left than twisting a throttle, how will Harley-Davidson survive? They've opened a plant in India, and have designed a line of smaller V-twins intended to appeal to women, urban riders, and foreign markets. Now it seems they're doubling down on their Livewire electric motorcycle program, hoping a spot as a premium e-Moto brand will secure a new generation of fans.

The Harley-Davidson team embarked on the Livewire project 6 years ago, gambling that battery technology would develop quickly enough to give their design the range and power it would need to compete head-on with traditional dinosaur-juice motorcycles. A new generation of ultra-compact, ultra-powerful batteries still hasn't emerged, but the e-Bike market is expected to expand 45% by 2020, as opposed to a continuing slide for Internal-Combustion (IC) motorcycle sales. Harley-Davidson announced an 11% drop in their sales in the last quarter of 2017, and closed their Kansas City plant. H-D CFO John Olin said they will invest $25-50Million per year to develop their electric motorcycle technology, with the goal of dominance in the premium e-Moto market.

'Slant Artists': Hillclimbers in California, 1925-35

What do you get when you combine drag racing, motocross, and a vertical surface? Hillclimbing, the American way! Two-wheeled motorsport in the USA went through dramatic changes before WW2, but it was hugely popular, depending on what 'it' was. From around 1910, Board Track racing fascinated crowds of tens of thousands, crammed into bleachers and peering over the banked wooden speed bowls, risking their heads (literally) as the riders risked their hides. With the press calling them 'murderdromes' by the 'Teens, and the sanctioning bodies losing their taste for 100mph bloodsports, the Board Track era died by the early 1920s.

Whence Came the Swingarm Frame?

The first motorcycles were hard things, that shook like hell over the rough cobbles and horse-shit roads of the late 19th and early 20th Century. Figuring out ways to absorb shocks and control a bike over bumps has been a challenge from the very early days of the industry. Spring forks were adopted first, as a bouncing front wheel is a lousy way to steer, and sprung rear wheels followed in an amazing variety of configurations, most of them surprisingly 'modern'. In the 'Teens, Merkels had monoshocks, Indians had leaf springs, Jeffersons had short links, and a dozen variations of all these appeared on bikes around the world.

[Special thanks to Dennis Quinlan for his original article on this subject, and Pete Young for his further research into early rear suspension, and a posthumous thanks to Stephen Wright for his brilliant research into early American motorcycles; please find a copy of 'The American Motorcycle: 1869-1914' and be amazed and enlightened!]

1935 - The Greatest TT?

[By David Royston]

Memorable races match two top rivals of comparable skill and equal valour, driven by the need to succeed, riding machines at the leading edge of performance, backed by well-drilled and determined teams. The Isle of Man Tourist Trophy provides the perfect setting to test man and machine, with challenges of the timed interval start, the mountain climb and weather, and the ordinary roads. My “Greatest TT race”, the Senior TT of 1935, brought all this together to provide one of the epic races of all time. But the story of this race really began in 1933.

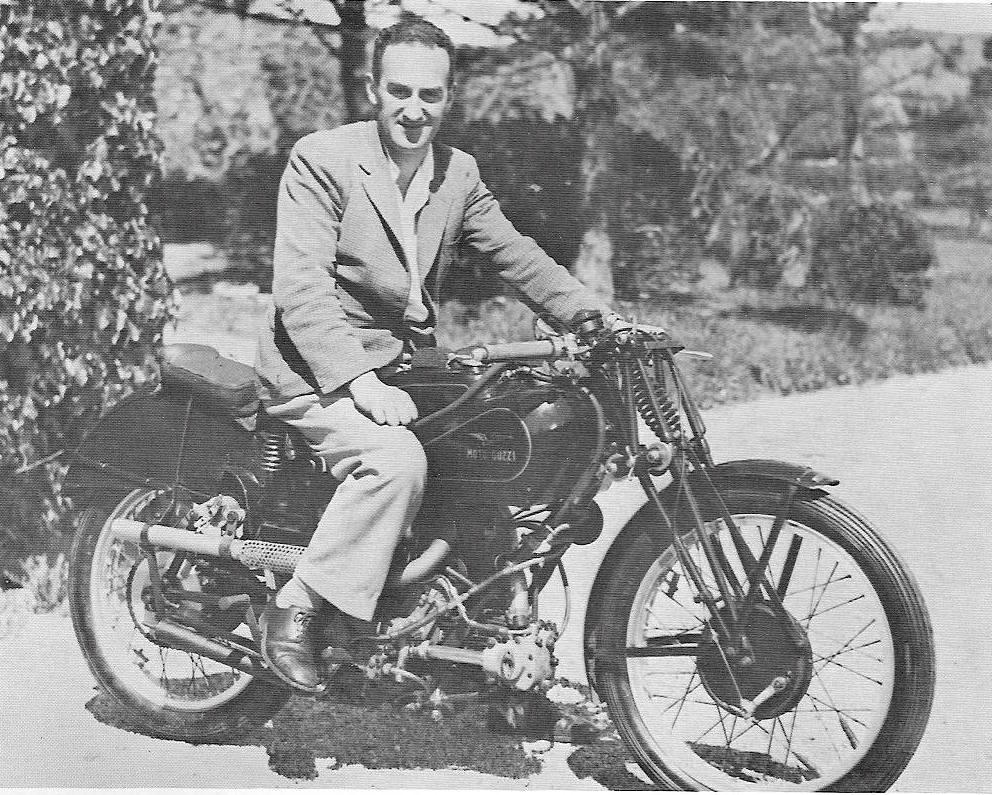

Preparation

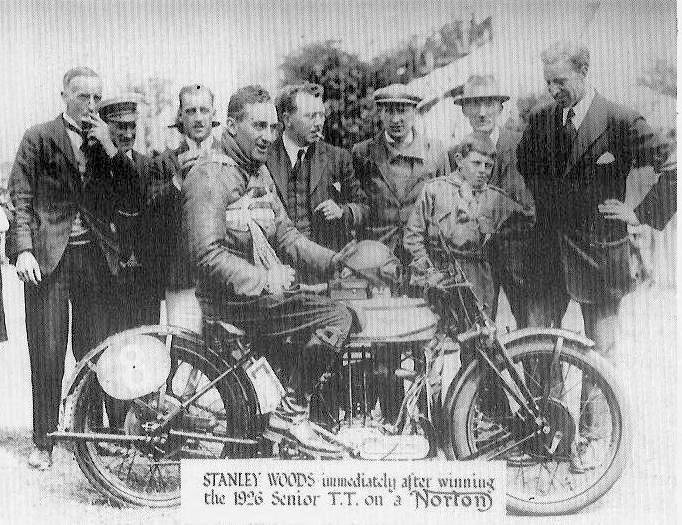

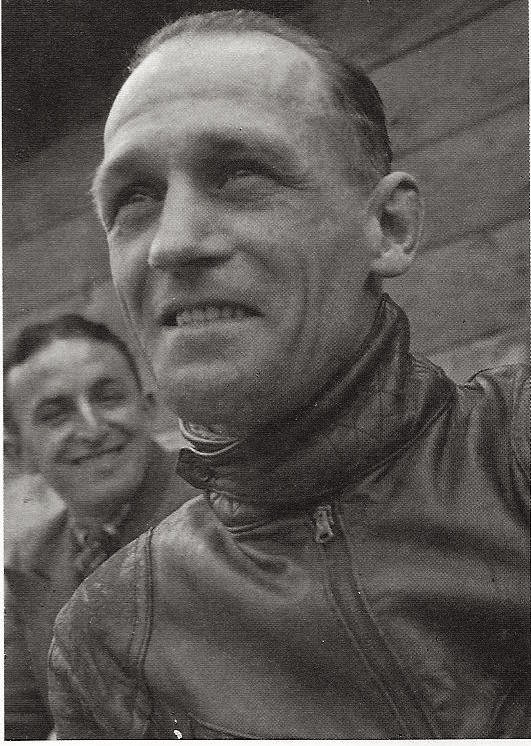

Stanley Woods, a Dubliner and rider of outstanding talent on any form of motorcycle, began his TT career in 1922 as a precocious 17-year old. Initially he combined riding with his work as a salesman for the sweet makers Mackintosh’s. In the following years Woods would provide boxes of toffees (from a business with his father) for the boy scouts that ran the leader board at the TT. He won his first (Junior) TT in 1923 on a Cotton; he moved to Norton in 1926 to win the Senior TT that year (at 21) and to begin a string wins for Norton including the Junior and Senior TTs in 1932 and 1933. By 1933 Norton had established such supremacy its winning was called “the Norton Habit” and the team began to allocate wins to particular riders in the team. This did not suit Woods who was the Norton team’s star. By the early 1930’s, motorcycling had become a professional sport and Woods, now at his peak, relied on wins and retainers to make his living: he decided to leave Norton. For the 1934 TT he was retained to ride the 500c twin Folke Mannerstedt designed light, powerful, but thirsty Husqvarna.

Jimmie Guthrie was from Hawick in Scotland, where he ran a successful motor business with his brother Archie. A survivor of the horrific 1915 Quintinshill troop train rail crash near Gretna, he served in Gallipoli and Palestine, then as a dispatch rider at the Somme and Arras. Guthrie had come into national motorcycle racing in his late 20’s, competing in his first TT in 1923 (the year of Woods’ first win). Four years later he returned as a regular competitor; he finally got a works ride with the Norton Team in 1931. Guthrie was well aware that he was older that other competitors and he had a vigorous training programme to keep fit. Guthrie took over as the lead rider for Norton at the end of 1933 and immediately showed he was on top of his form. He made his mark winning the 1934 Junior and Senior TTs. The latter after a strong challenge to the Norton team from Stanley Woods. That challenge failed on the last lap with a spill at Ramsay Hairpin followed by the Husqvarna running of fuel 8 miles from the finish: the feared threat from foreign machines, ‘the foreign menace’, was at the doorstep.

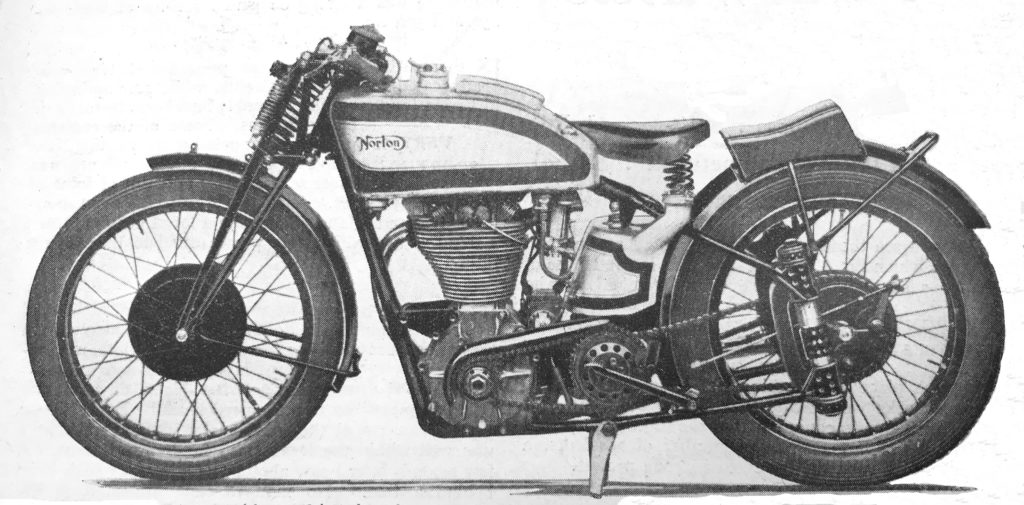

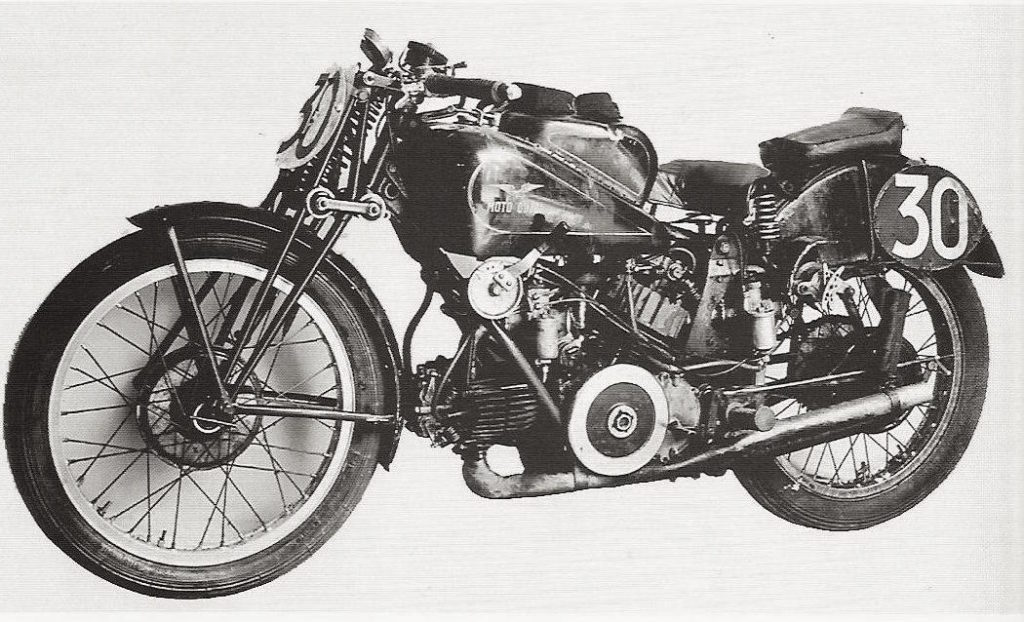

By 1935, the Norton team was a well-oiled TT-winning machine with ‘the Fox’ Joe Craig (and his TT signal stage system) in charge. Its bike was the best in the business. Walter Moore designed a powerful ohc-single engine in 1926/7 for Norton (Moore used the Chater Lea system for reference; Stanley Woods said impishly Moore took the worst aspects from it). Though the engine was an immediate winner it was unreliable and was progressively redesigned and improved significantly from 1929 by Arthur Carroll and Joe Craig, to more closely resemble the Velocette system of 1925; Moore had 'copied the wrong one!' The 500c engine probably was developing 35-38 bhp by 1935 (sadly the year Arthur Carroll died in a crash while riding his fast ‘tweaked’ side-valve Norton). The TT Norton had a good handling (for the period), though it still used a rigid frame with girder forks. The whole package was refined with an emphasis on lightness. Velocette was still in its wilderness years: it had pioneered the ohc single successfully at the TT in the late 1920’s but had lost its way at the top level on frame design and brakes.

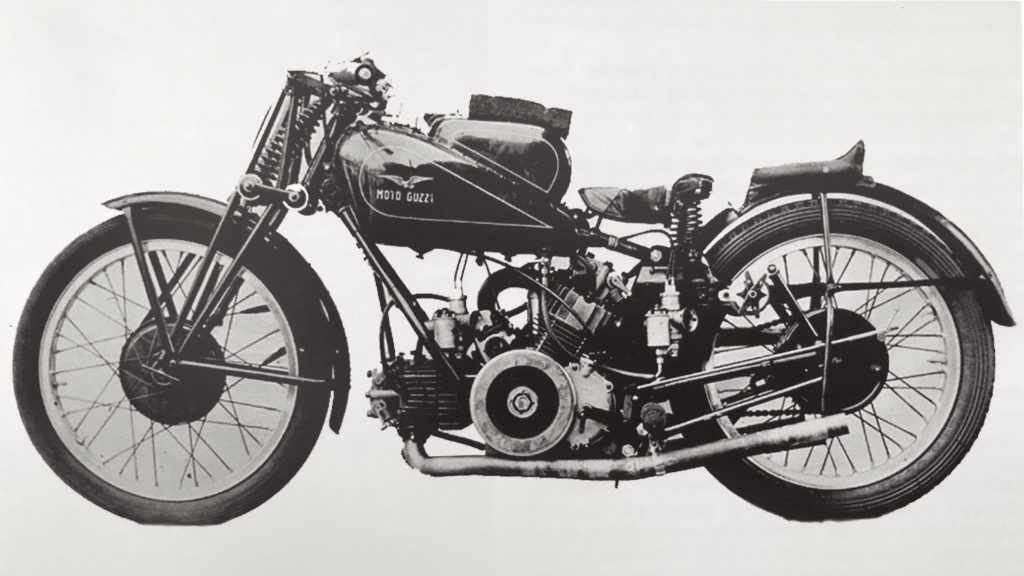

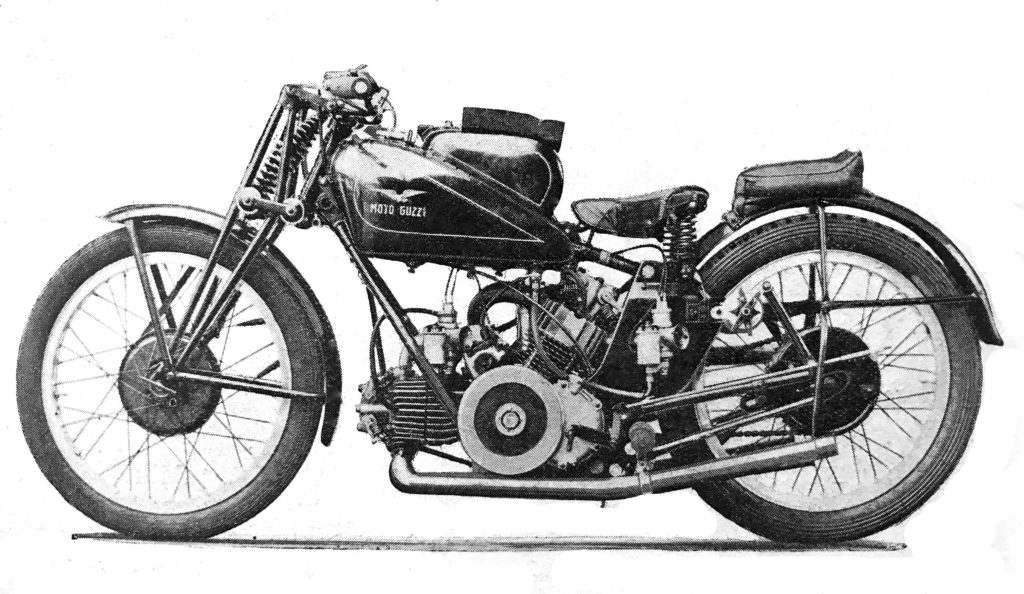

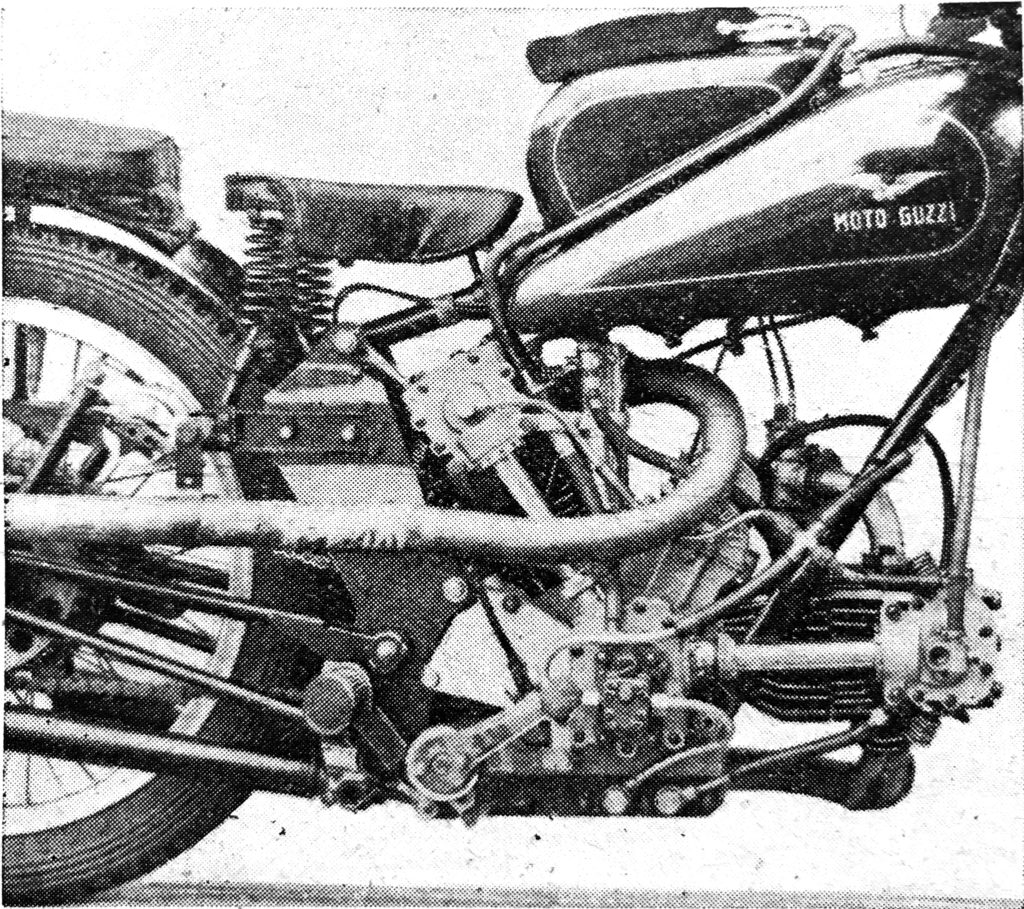

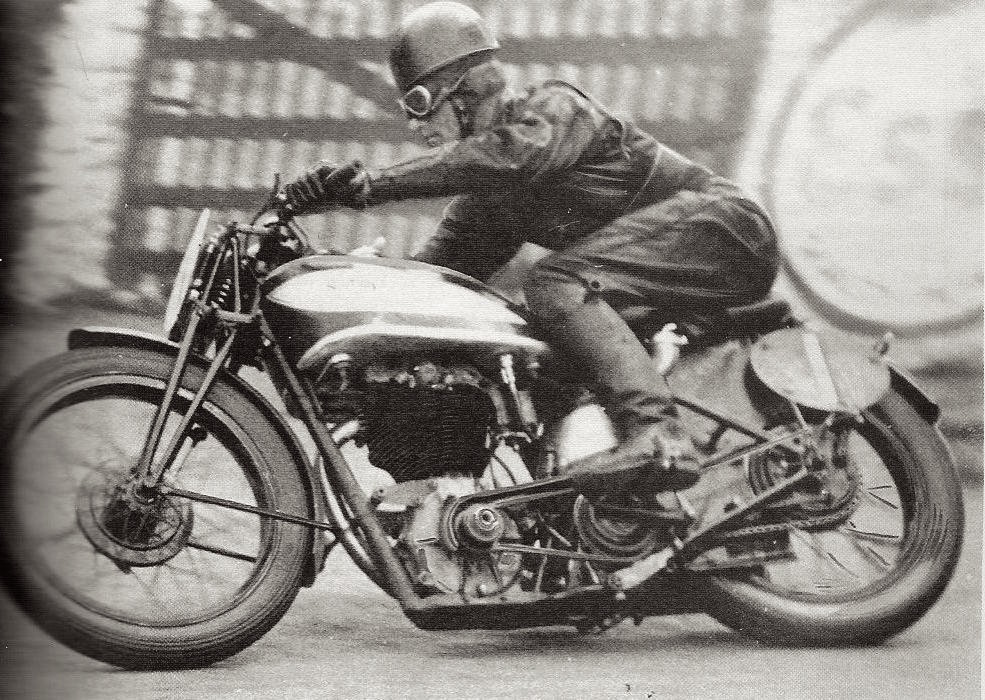

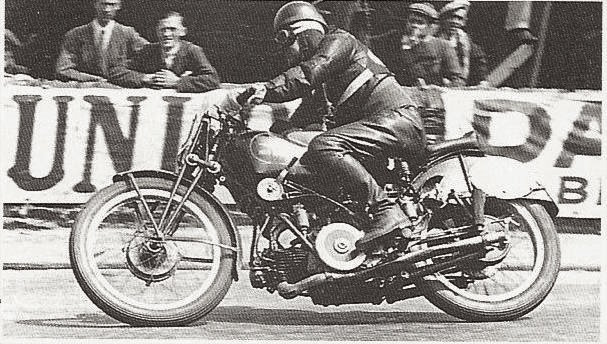

In practice for the Senior TT, Norton preparation was developed to new levels. But in the background there were reports of high speeds from the Moto Guzzi including on the last day of practice an unofficial lap record. Then Stanley Woods won the Lightweight TT on a 250cc horizontal single Moto Guzzi, a first for a foreign bike: the ‘foreign menace’ had arrived.

The Race

Fog covered the Isle of Man on Friday June 21st the day of the Senior TT and the race was postponed to 11 am the next day. As Saturday dawned fog still covered the Island and many were concerned that the race could be cancelled. The start was put back half an hour to 11:30. With tension building the clock crept towards the new deadline. Finally the fog lifted enough for the race to start; all involved looked to the event with great expectations.

The third lap was the one where teams were to take on fuel. Guthrie came into the pits after yet another lap record of 26 minutes and 28 seconds. The Norton team moved smoothly into well-practiced action and had him refuelled and out in 33 seconds by the reporter’s stopwatch. Almost 15 minutes later Woods came into the pits now 52 seconds behind and, to the surprise of onlookers, in a lightening stop was away in 31 seconds by the same watch. With such a short stop there was speculation as to whether the twin had enough fuel to make the next four laps at record pace? Especially given the Husqvarna experience the year before.

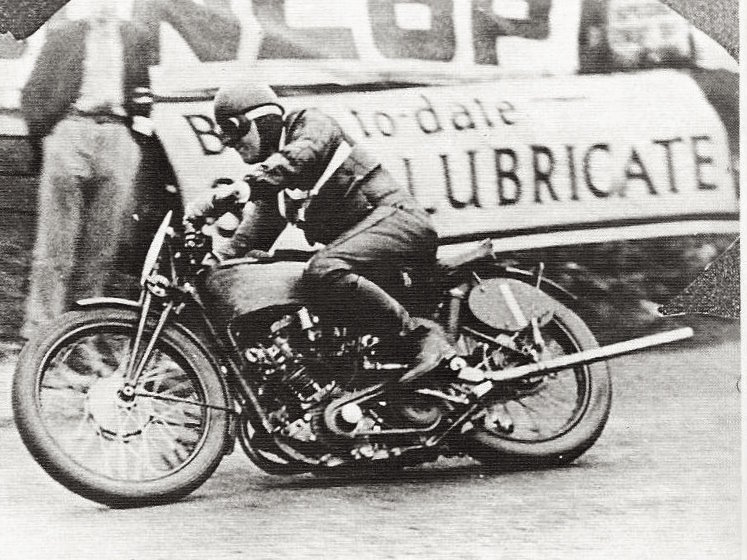

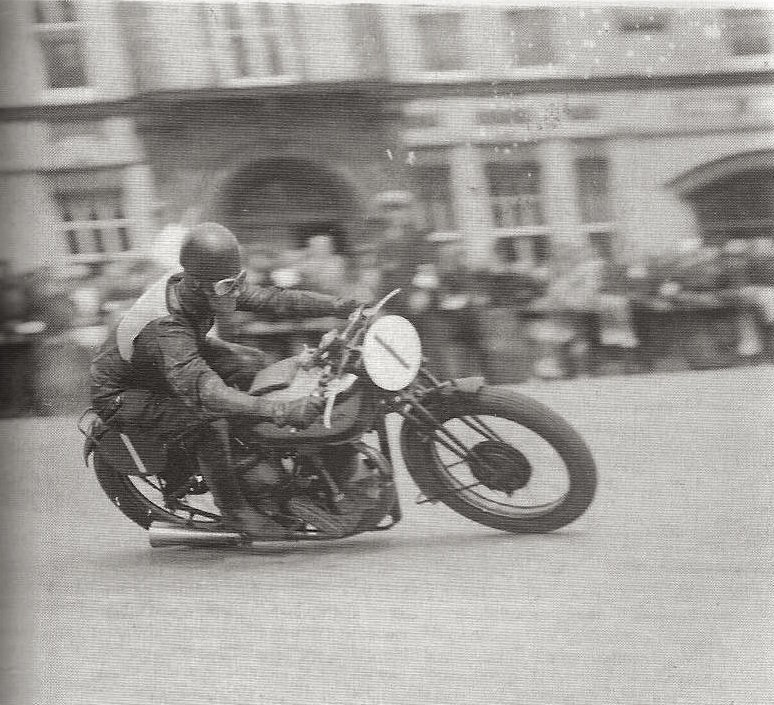

On the Fourth Lap, both Guthrie and Woods continued at near record pace. Motorcycling magazine shows pictures of both riders and their bikes coming down Bray Hill. The Norton has its front wheel in the air; the Moto Guzzi is firmly planted on the ground. It was said the sprung frame could be worth as much as 20 seconds a lap, would this tell? Woods closed the gap to 42 seconds.

On the fifth lap Woods reduced the lap record to 26 minutes and 26 seconds, closing the gap to 29 seconds. He had pulled back 13 seconds on just one lap; the challenge was on.

We now come to end of the critical sixth lap. Guthrie’s Norton went through without stopping. The Moto Guzzi team busied themselves setting up for a fuel-stop and the grandstand crowd expected Woods and the thirsty Guzzi to stop for fuel. Joe Craig may have thought Norton had the race won. It is said he had sent signals to his station at Glen Helen for Guthrie, almost ⅔ of a lap ahead, to ease his pace perhaps fearing the record laps could affect the bike and the rider.

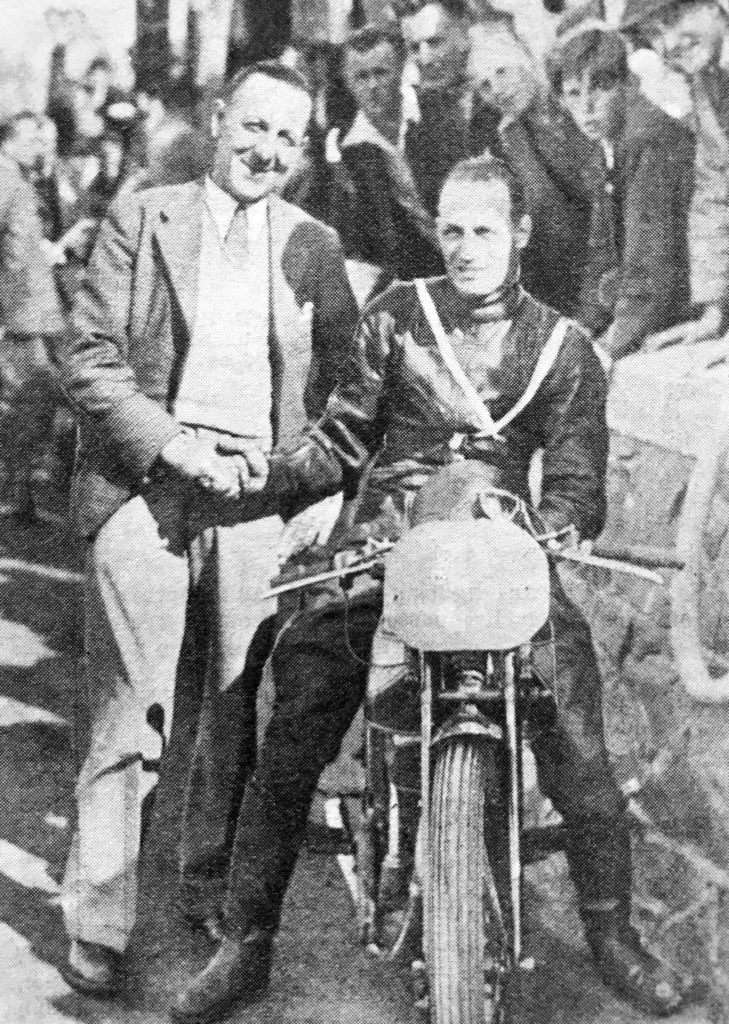

Stanley Woods and the Guzzi could be heard approaching the Grandstand. To the surprise of everyone but the Guzzi team, he shot through, on the tank, flat-out, now 26 seconds behind: man and machine on a mission. Could the Moto Guzzi pit-stop ploy have made a difference? Norton immediately rang through to Ramsay to signal Guthrie to speed up. It was now all up to Woods. As Mario Colombo (from a Guzzi perspective) puts it: “L’ultimo giro, il settimo, si svolge in un’atmosfera di tormento e di sofferenza, gli occhi al cronometro, l’orecchio teso” (“The seventh and last lap unfolded in an atmosphere of suffering and torment, with all eyes on the stopwatches and all ears alert”). Reports were coming through that Woods was running fast all around the circuit: the Moto Guzzi ‘bicilindrica’ was rising to the occasion. At the base of the mountain he had the gap down to 12 seconds, down the mountain he had the bike wound up to 125mph. At Creg-Ny-Baa the gap was 6 seconds. Guthrie had come through on his seventh and final lap at near-record pace – he knew Woods well enough maybe not to trust the signals. Colombo writes: “Guthrie arrived at the finish and silence fell like a tangible thing: everyone had their eyes fixed on the beginning of the final straight”. Not all it seems, the officials and the radio commentary, based on the times from the sixth lap, thought Guthrie had won. He was toasted and congratulated by the Governor of the Isle of Man. Motorcycling magazine has a photograph of the Guthrie and the bike surrounding by supporters as a smiling ‘winner’. An official was leading Guthrie to the microphone when, after 14½ minutes of suspense, with its characteristic roar, the red Guzzi with Woods “buried in the tank” flashed across the line. “A thousand stopwatches clicked and feverish calculations were made”. That official was stopped with the news that Woods had won by 4 seconds. He’d done it. Woods had ridden an outstanding last record lap (26minutes and 10 seconds, 86.53 mph). His race time was 3 hours 7 minutes and 10 seconds, an average speed of 84.68mph. The crowd understood the significance of the moment, setting aside any thoughts of the ‘foreign menace’, the grandstand rose to cheer the winning team and rider, “…spectators thronged around Guzzi, Parodi, Woods and the mechanics in a display of sporting spirit those present never forgot”.

Guthrie looked dazed by the abrupt change of fortune but took it in good grace reflecting the depth of his character and reserved manner (off a bike!): he was amongst the first to congratulate Woods. After the race Jimmie Guthrie said; "I went as quick as I could but Stanley went quicker. I am sorry but I did the best I could." They were friends as well as rivals. Stanley Woods said years later: “I turned on everything I had on the last lap. I over-revved and beat him by 4 seconds and put up the lap record by 3-4 mph. And that (beating Norton), I think, gave me more satisfaction and more joy, the fact that I had beaten Norton. Its what I had set out to do. It was very very satisfactory”. MotorCycling magazine carried a second photograph with Stanley Woods, and his trademark grin, as the true winner of my ‘Greatest TT’.

Was the difference in those pit stops? It is possible both riders covered the ground in the same time. What about the fuel in Wood’s tank? A reporter said there was an inch in the bottom almost enough for another lap; it seems that the Guzzi did have an extra-large tank for the TT, maybe it was very full on the first slow laps. MotorCycling magazine discussed whether the fake pit stop was sporting but accepted the tactic as legitimate (quaint considering team tactics these days). Perhaps for once the fox was just outfoxed?

What happened to these two great riders? Guthrie continued with Norton and turned the tables in the 1936 Senior TT (winning by 18 seconds over Woods now riding for Velocette). In 1937 Guthrie won the Junior but his bike broke down at ‘The Cutting’ in the Senior. He was killed later that year (at 40) while leading the German GP at the Sachsenring. Woods was slowed in that race (by broken fuel line) and saw a rider ahead too close to Guthrie. It was said the accident was a result of mechanical failure. Woods, interviewed in 1992, said he thought Guthrie had been forced off line and into the trees at the Noetzhold corner. Woods was the first on the scene and went with him to the hospital: “the surgeon came out and said that they'd revived him momentarily, but that he had died. You can imagine how I felt. We'd been friends, team-mates and rivals for ten years. I was shattered." The ‘Guthrie Memorial’ stands where he had stopped in his last TT; the ‘Guthrie Stone’ marks the accident spot at the Sachsenring. Woods won the Junior TT for Velocette in 1938 and 1939; also with Velocette he was a close second to Norton in the Senior TTs of ’36,’37 and ’38 and just missed third by 6 seconds behind Freddie Frith (Norton) when the BMW supercharged bikes took first and second in 1939. Woods did not return to racing after 1945 but did test rides (including on the Guzzi V8 in ’56) and demonstration rides at the TTs into his 80’s. It took Mike Hailwood to beat his ten TT wins. Stanley Woods died in 1993 aged 90, still regarded by many as the greatest rider of all.