Cliff 'Soney' Vaughs and 'Easy Rider'

Adapted from Paul d'Orléans' book 'The Chopper: the Real Story'

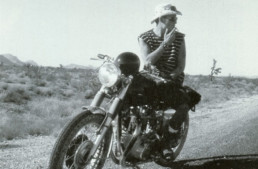

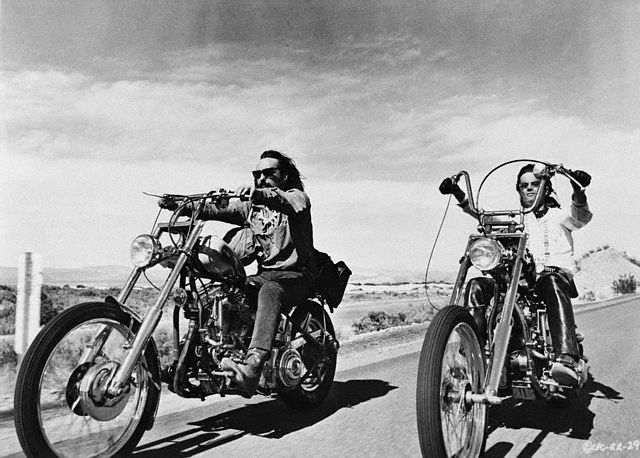

It’s the most famous motorcycle in the world, period. Show someone a photograph of the ‘Captain America’ bike from ‘Easy Rider’, and everyone knows what they’re looking at. Show them Rollie Free stretched out in a bathing suit over his Vincent at Bonneville in 1948, and they’ll laugh, but won’t know a thing about the bike or the man. Show them TE Lawrence on his Brough Superior, and they’ll recognize neither the quizzical WW1 hero, nor his Brough Superior. The Captain America chopper transcends its own story; nobody needs to have seen the film, nor recognize Peter Fonda, to understand they’re looking at an icon, a magical talisman of Freedom. Such is the power of the machine’s image, and its place in the cultural history of motorcycling around the world. Far more people idolized that motorcycle than ever saw the film; all they needed was a photograph of Dennis Hopper (on the ‘Billy’ bike) and Peter Fonda, riding through the anonymous landscape of the American West, modern day cowboys roaming the land; free, just free.

If anyone thought to ask ‘who built that?’ (and few did), they might have assumed Peter Fonda built it, but most admirers of Captain America were simply glad it existed, as if it had been delivered from the gods. Its lines and proportions are perfect, as is the American flag paint job, which slip under one’s skin and electrify subconscious associations: the cowboy, the outlaw, America, freedom, power, speed, sex, drugs and rock music. Those admiring the Easy Rider choppers didn’t want to be Peter Fonda, they wanted to be Captain America. They wanted to own that bike and ride it and eat it and absorb everything the bike stood for into their very beings, to become the gods that bike promised we could become. It is a powerful work of art, a coveted, elusive object, copied a thousand times all over the globe, but it cannot be truly captured, as it exists only in the realm of dreams.

Who Is Soney Vaughs?

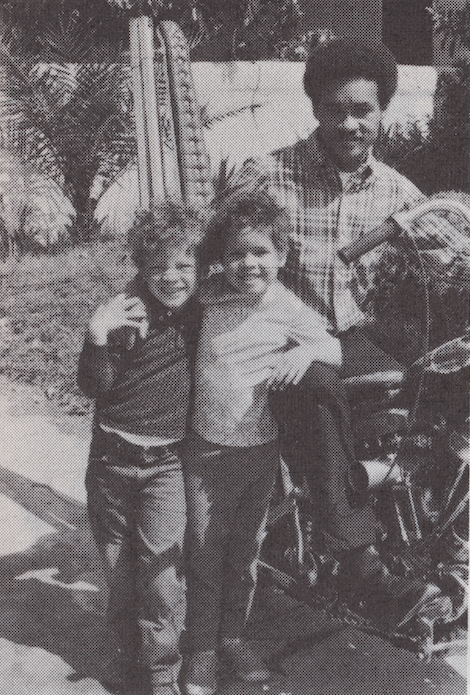

Clifford A. ‘Soney’ (the spelling is his mother’s) Vaughs was born in Boston on April 16th, 1937, to a single mother who was 16 at the time; she’d been kicked out of the family compound in Gibbsboro, New Jersey, for her unwed status, so moved to Massachusetts to be near a more sympathetic aunt. As a boy, Cliff attended the Boston Latin School, from whence he derived a particular pattern of speech, and a facility with language – Cliff was specific about his words, and at times prickly in their usage. In 1953 he joined the Marines, and tested so highly he was scheduled for flight training, and sent to a base Pensacola, Florida. He was immediately rebuffed by the CO of the base, who turned him right back to Boston, refusing the possibility of a black pilot on his watch, and an integrated flight training school. “Things were different in Florida than Boston”, noted Cliff. Instead, he was transferred to Electronics Technician School at Great Lakes NTC. After 3 years of active duty, he worked at the Boston Navy yard on the cruiser ‘Boston’ as a technician on its radar installations for guided missiles. After the USMC he took a job with Raytheon, working on the guidance systems of Sparrow and Hawk missiles. He decided to further his education at Boston University for his BA, then trekked to the University of Mexico in Mexico City for his Masters, driving his Triumph TR3 all the way from Boston. “At the time they offered a progressive Latin American Studies graduate Program. Plus I liked driving my TR3 from Boston to Mexico City. I had family friends living in Cuernavaca; buddies from the ‘Village’. Acapulco on weekends.” He hung out, of course, with future F1 racing legends the Rodriguez brothers (Pedro and Ricardo), who seemed immune from the law’s attention while driving unregistered Formula racing cars on the streets of the District Federal.

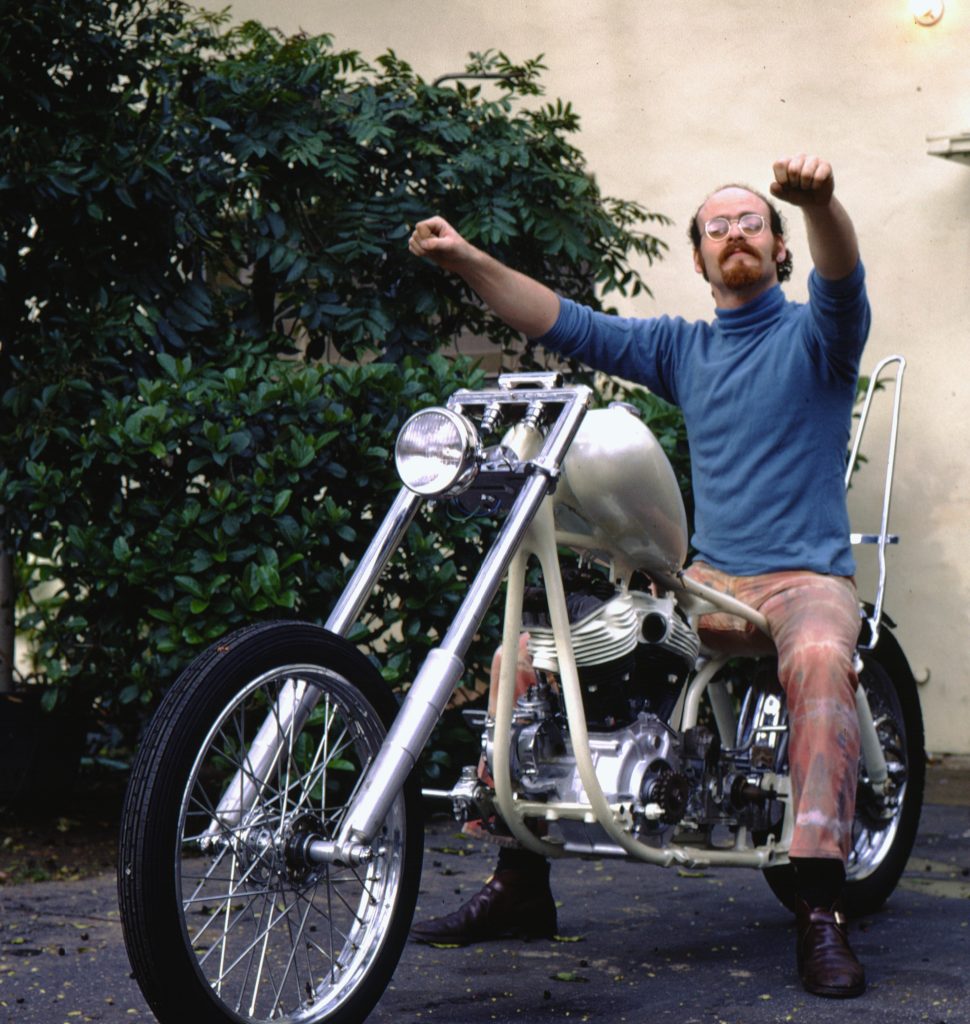

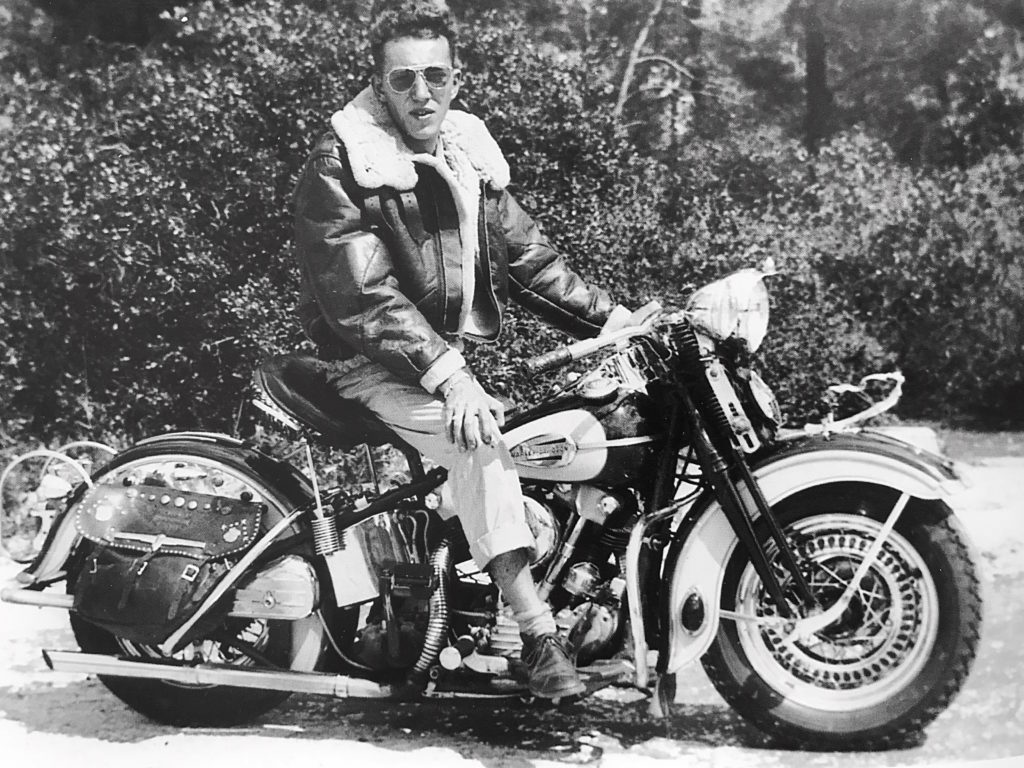

1961: First Chopper

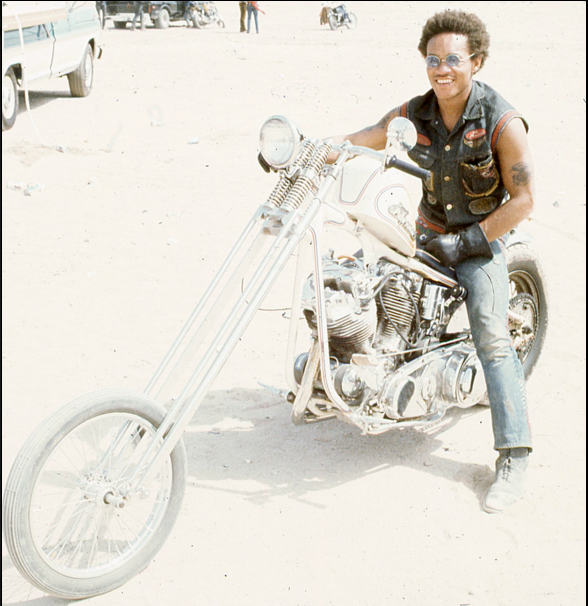

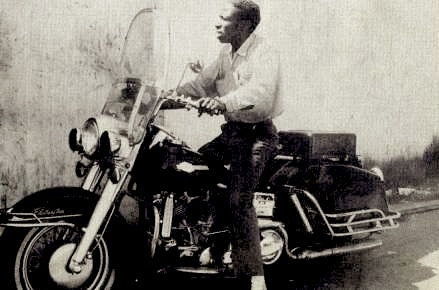

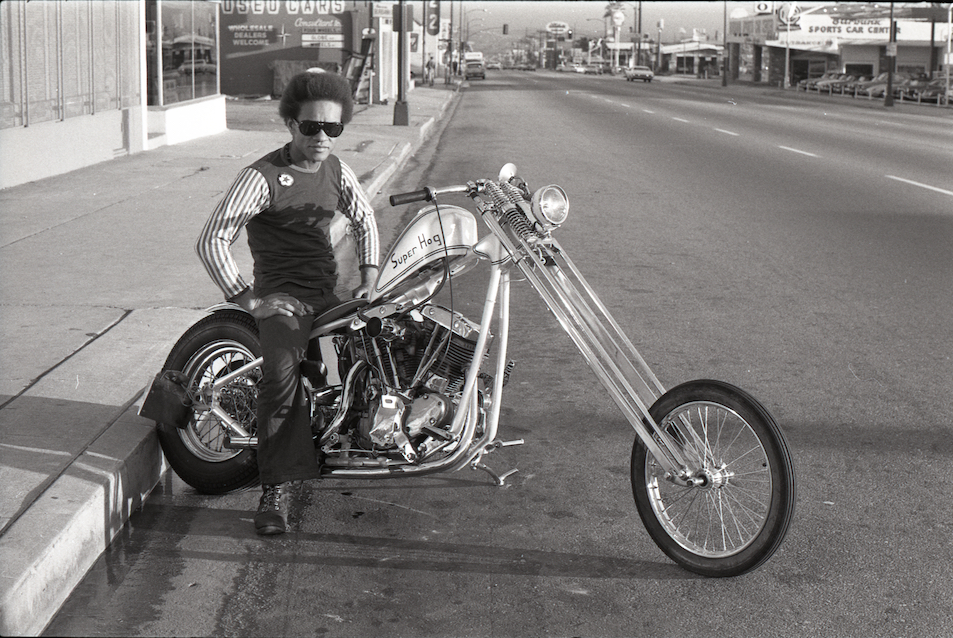

By 1961 he “went from Mexico to Santa Monica where, I had a sort of ‘drawing room.’ [An] art, literary cocktail scene just as I had on a regular basis in Boston. Several friends came to visit. In those days we were called Bohemians.” In Santa Monica, living very close the beach, he had purchased an AJS Model 18S enduro for $300 from Motorcycles Unlimited on Pico Blvd, for plonking around town. His 5 uncles all rode Harley-Davidsons back in New Jersey, so motorcycling was in his blood. The Ajay had ‘knobbies’, which led to a slide-out on Dead Man’s Curve on Sunset Blvd; luckily he’d worn a helmet, for he could hear it clonking on the ground as he slid. The AJS took him and his then wife Wendy down to Tijuana for the Tecate Enduro races, and encountered about 2000 other riders, most of whom had ridden from SoCal. “As I rode home two-up on the Ajay, it seemed like all 2000 riders went roaring past us on Hwy 1. So I sold my AJS, and bought a Knucklehead chopper from a friend who needed some money. When I got the Knuck, I knew nothing about motorcycles really. Nobody in Santa Monica knew anything about them, but I’d heard of Ben Hardy in South Central, and another guy named Wes who had a shop too, but was less popular. When I needed parts, Ben Hardy would send me to Jim Magnera of MC Supply; it turned out Jim had subsidized Ben to open his shop. Black shops at the time couldn’t buy parts directly through the Harley-Davidson dealer, so Magnera became the small shops’ conduit for Harley parts.” He met the Chosen Few MC while sleeping by his chopper on the side of Highway 99 en route north; they invited Cliff to join them on a run to Oakland to visit the East Bay Dragons MC, and after they returned, Cliff was presented with his CFMC ‘club cut’, “I didn’t have to prospect, they just made me a member.”

Recruited to the Cause

Vaughs admits that when Dr Martin Luther King Jr led the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, “I was building a chopper in my backyard. I knew it was happening, but I hadn’t been politicized. Boston had nothing going on in terms of race at the time, it was all mixed race among my friends. We were all the American refugees; Italians, Jews, blacks, etc. I’d heard about the Freedom Rides, but, being from Boston, I thought, ‘What could happen?’ Cliff met Civil Rights legend Bob Zelner, the first white field coordinator for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), when he passed through LA in 1963 on a fundraising tour. Vaughs was recruited to the SNCC cause, and drove his 1953 Chevy half-ton pickup to Mississippi. Of course, being Cliff, he laid stainless steel in the truck’s bed, with teak runners, and a white fiberglass tailgate with ‘SNCC’ in big black letters. Outrageous, and an instant target, “In the window I had an ‘Ole Miss’ [University of Mississippi] sticker; I’ve been shot at many times.”

"They took a shot at us from behind and missed."

Even more outrageous was riding his blue Knucklehead chopper to Arkansas in 1964, with a white girl on the back. “The fiery ending of ‘Easy Rider’ is an example of art imitating life. I was riding my chopper on the highway between Pine Bluff and Little Rock, pursuing an assignment for SNCC to initiate a school boycott there. I had with me a staff member of the Arkansas Project, a Miss Iris Greenburg. A pickup truck passed us going in the opposite direction, stopped and turned around. They took a shot at us from behind and missed. They didn't pursue us any further...so I lived to tell this tale.” Of all the crazy motorcycle tales one hears about the 1960s, this is perhaps the hairiest story of all, and a sign that Soney was both a civil rights volunteer and a bit of a provocateur. “I may have been naïve thinking I could be an example to the black folks who were living in the South, but that’s why I rode my chopper in Alabama. I’d visit people in their dirt-floor shacks, living like slavery had never ended, and it was very tense; I was never sure if the white landowners would chase me off with a shotgun. But I wanted to be a visible example to them; a free black man on my motorcycle.”

"You are crazy," John Lewis said, "I will not march next to you."

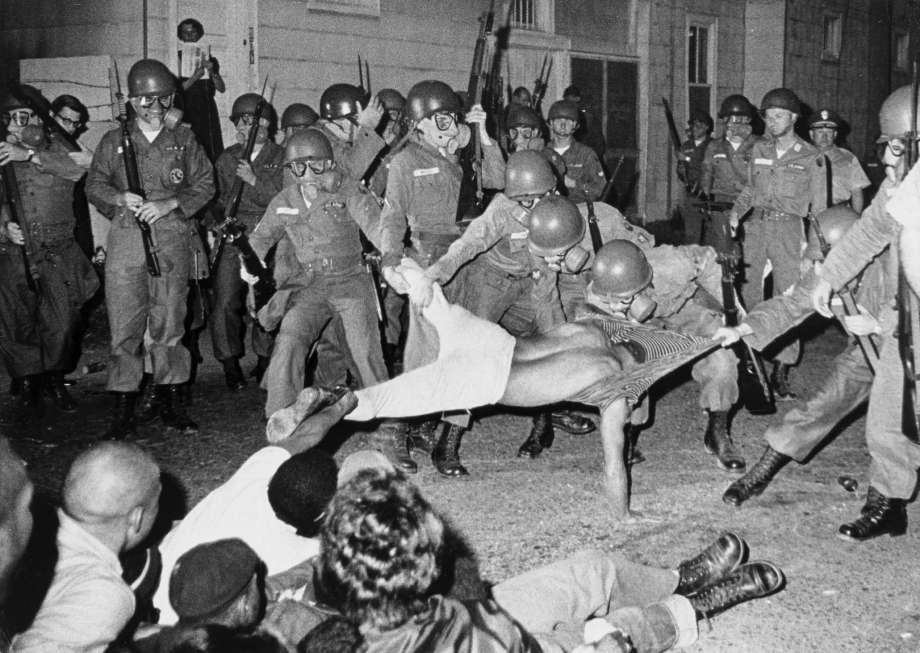

He carried on with SNCC through 1964, which is when he met photographer Danny Lyon (of ‘The Bikeriders’ fame), who snapped the infamous photo of Vaughs being bodily lifted, shirtless and shoeless, by no less than 6 helmeted National Guardsmen in Cambridge, Maryland, on May 2nd, 1964. “Stokely Carmichael is holding my other leg in that photo”, says Cliff. “Later on, Danny Lyon lived next to me in Malibu.”

The Origin of ‘Easy Rider’

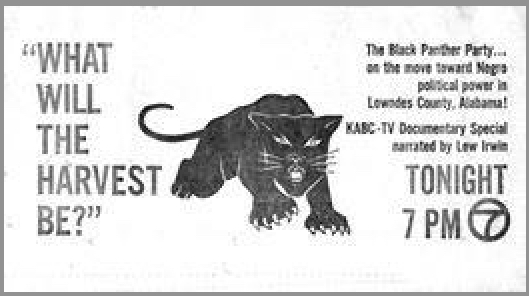

Vaughs began making documentary films with "What Will the Harvest Be?", narrated by Julian Bond, about the rise of Black Power (a term Stokeley Camichael popularized) in the South, which included interviews with Dr Martin Luther King Jr, Carmichael, and Julian Bond, which was aired on ABC-TV in the mid-60s. He was also working at Los Angeles radio station KRLA, which is how he met Peter Fonda. “Peter was arrested for possession of marijuana. I was mildly amused that so much interest was engendered by the incident, considering the number of citizens detained and incarcerated for smoking ‘pot’. We chatted for a while at the courthouse and I called in my story. He was interested in my hobby: designing and building motorcycles. It turned out that we lived in the same neighborhood, West Hollywood. I told him I was usually found in my back yard enjoying my hobby.”

"We ad-libbed a story line: two friends (not quite ‘bikers’), traveling across America seeking adventure"

Elder Pattison de Turk III (henceforth Pat de Turk) remembers,“I moved into Cliff's house in West Hollywood in the fall of '67. I was working full time, and preparing to begin a career in computer programming…I met Cliff in 1961 while I was studying at UCLA and riding Harley 45”, and Cliff had an AJS scrambler. I soon had a lime green Knucklehead chopper that I bought for $300 on Venice Blvd. I was in the living room when Peter [Fonda] and Dennis [Hopper] were visiting. Dennis was slightly mad and a motormouth, he was incessant, so he pretty well dominated the conversation, and I was completely intimidated by the situation, I was just Sonny’s friend and all of the sudden here were these movie stars in the room. They came over several times…and of course, there was the ever-present small tapestry on the wall - "Where has my Easy Rider gone?"

Larry Marcus; the Mechanic

Larry Marcus, mentioned above, was a mechanic, who Vaughs said “knows more about tools than anyone”, and who was also living at Cliff’s house at the time the Easy Rider project began in 1967. “The first time I recall meeting Soney was while I was working as a mechanic at Motorcars by Sutton on Western Ave, the Fiat / Rover/ Jaguar/ Triumph/ Renault dealer, it just a little tiny shop. I used to drive up to Griffith park for lunch. Soney walked in one day to get his Fiat 500 fixed, he was working for KRLA at the time, wearing a hippie shirt and flowered tie. KRLA did a lot of avant garde stuff on TV, things that had never tried before, like Ernie Kovaks. At the shop, he pulled me aside, and said he knew who I was, but didn’t want to acknowledge me as we were both on our jobs; he said we’d met at Goddard College back East, we had mutual friends there. I had been living in Europe in ‘62/’63, but applied to Goddard to stay out of the draft, as I’d been told I’d be drafted immediately if I showed up at a European draft office. After college I moved to Cali in 1966. Anyway, I offered to work after hours on Soney’s Fiat, so he didn’t have to pay the shop rate.”

Making ‘Captain America’ and ‘Billy’

Larry Marcus was living with Cliff Vaughs by 1967, when discussion for Easy Rider began. “The title ‘Easy Rider’ was Soney’s idea, taken from a Bessie Smith song from 1928. There was a thing on the wall … a little tapestry hanging, which said ‘Where Has My Easy Rider Gone’ with no question mark, the letters were sewn on, in paper, I’d never seen that kind of art before. A girlfriend of Soney’s made it, long before the film.”

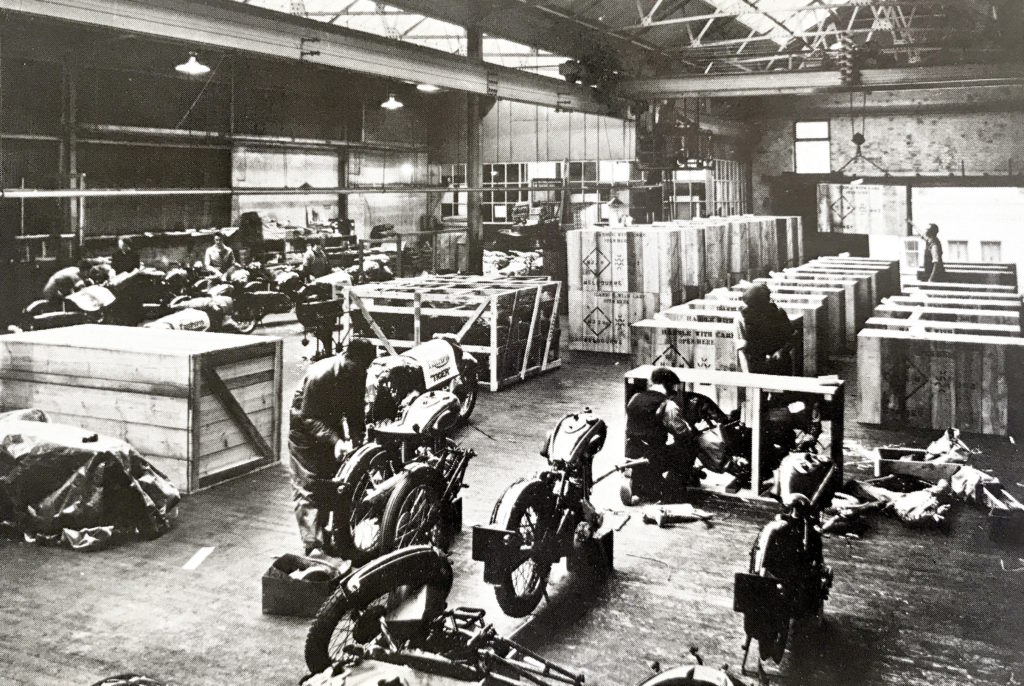

"Ben Hardy built the first two Easy Rider bikes."

Vaughs’ recalls of the Captain America bike, “When we did the first prototype of the bike it had no front brake, as I never used a front brake, which led to some harrowing experiences, especially with a chromed rear brake drum which would heat up quickly and fade. You’re always working the gearbox to slow down. For the movie, I had to put a hand clutch on the bike, as Peter wasn’t used to a suicide shifter. I could assemble a bike after all the parts were finished in about 6 hours, but it took time for Buchanan’s to build the frames, and Dean to do the painting. But with my resources and contacts through Ben Hardy, we got all our parts finished in 3 weeks. I had the money, and they all knew we were working on a film. In the creation of the bikes we used Buchanan’s for frame fabrication, Dean Lanza for the artwork [painting], Larry Hooper for upholstery, using LAPD junkyard engines, which were rebuilt by Mr. Hardy. Mr. Hardy also designed and constructed one of the fine points on the motorcycles; I had wanted something unique and he built the curved tail light brackets. After I had completed the construction of the machines, the registration (pink slip) was in the name of Pando Company.”

Ad-libbed and Ad Hoc

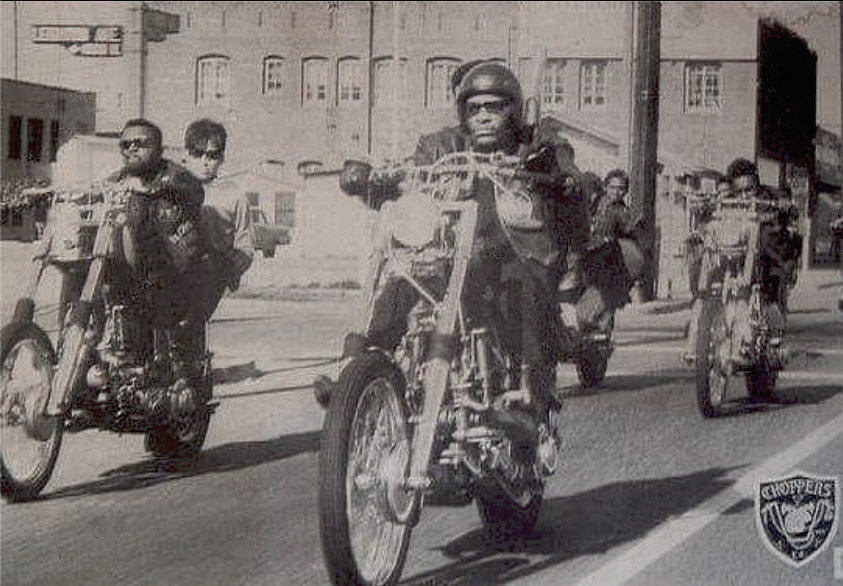

The actual filming of Easy Rider was notoriously chaotic, with an ad hoc film crew and, as Marcus says, “Terry Southern writing the dialogue on the crew bus between takes!” With Vaughs as co-producer and Marcus working as a sound technician, Marcus recalls his pay rose to $150/week during the actual shooting. “I’m proud to have about a minute of sound in the film, I worked with Les Blank, who was on the second crew with me. When one of our bikes wouldn’t start on the set, we were fired.” He adds, “I worshiped the ground Dennis Hopper walked on, he was an extremely talented guy, but I never got along with Peter.” A deleted scene from the film included Hopper and Fonda, broken down with their choppers on the side of the road, when a black chopper club (members of the Chosen Few) approaches and stops. “We have a situation where the two main characters are riding across country. Their bikes break down and they run into about 50 black cyclists. They are very, very up-tight, scared and shaken up. But, it works out very well because the black cats just say, “Can we help you get some gas?” Everything is very groovy. And that to me seems a real situation. I maintain if that situation can happen and it does in real life there is still some hope. There are many, many people that maintain that it can’t happen. But I’ve seen it happen this way.” But, after Vaughs was fired, this scene was deleted from ‘Easy Rider’, and “there were no African Americans in the film as actors or participants in the production.” Interestingly, Vaughs’ own experience as a black chopper rider echoed the deleted scene; “I never experienced issues around race with bikers. There’s a myth of racism around 1% clubs, but I’ve never experienced it. I was always offered the helping hand of fraternity.” Both Vaughs and Marcus lament the cutting of the ‘Chosen Few’ scene, which to them spoke to the reality of chopper riding in LA at the time. Had that scene not been deleted, it might have altered the perception in the years after ‘Easy Rider’ that choppers were solely a white man’s game, and the cloud of racist associations hovering around this ‘folk art’ motorcycle style might have been cleared away.

[There are more terrific stories in 'The Chopper; the Real Story' - buy it here!]

DG Manktelow, Cafe Racer

[Words: Paul d'Orléans. Photos: D.G. Manktelow]

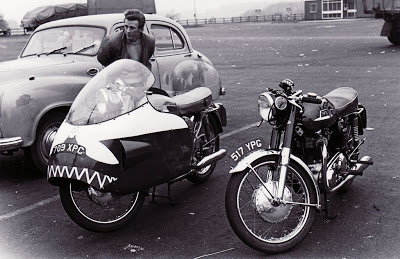

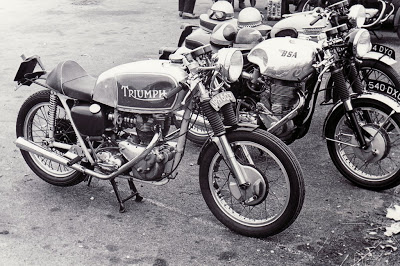

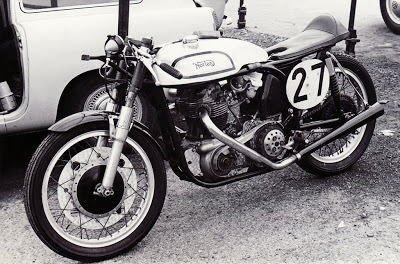

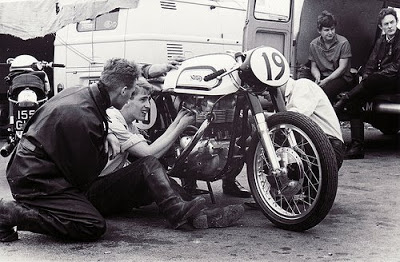

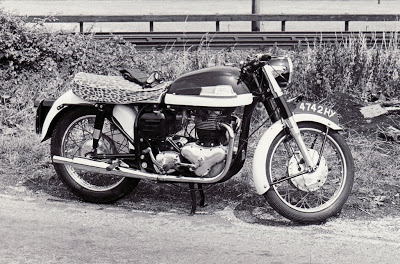

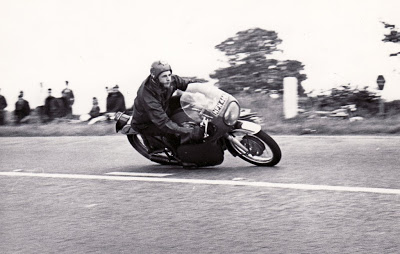

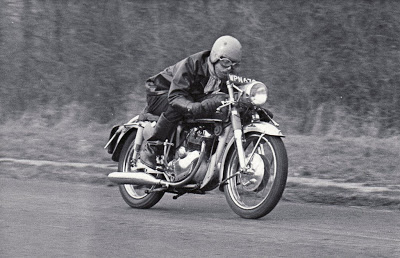

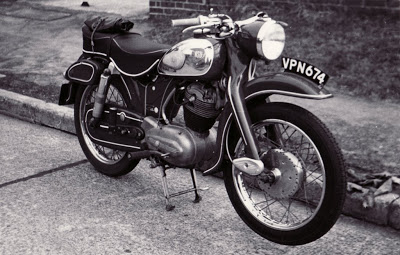

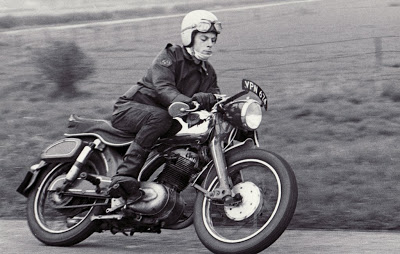

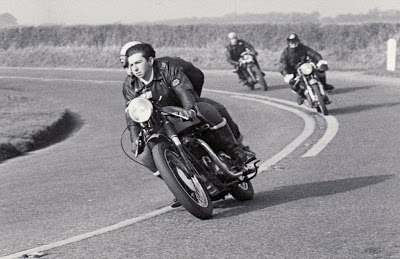

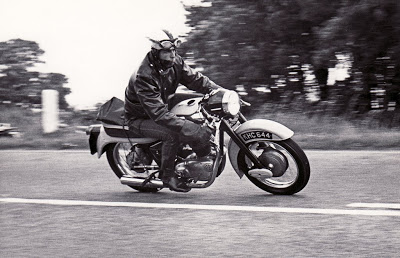

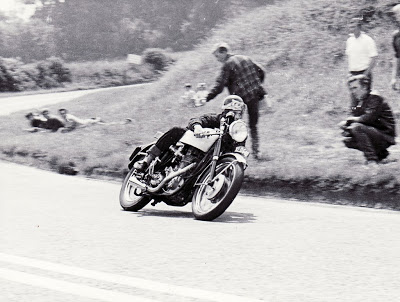

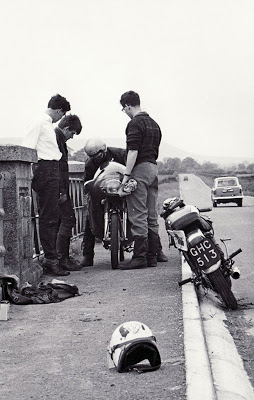

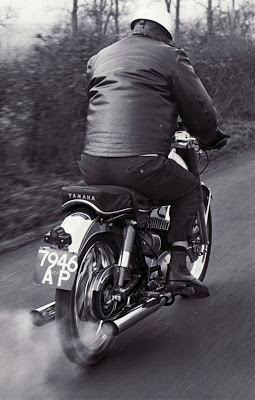

D.G. Manktelow needed a few college credits, and had an interest in photography, so took a photography class in East Sussex, England, in 1960. He documented his friends in the the British Rocker scene from 1960-65. Be careful what you study as an afterthought in college - it's likely to become your career after graduation, as happened with D.G., who became a professional photographer. His son Adrian Manktelow has kindly consented to show some of D.G.'s photos on The Vintagent, as a tribute to his father's skill, and the unique period he documented. Many of the riders remain family friends, although a few didn't pass the trial by fire of the Rocker years...

And all the classic Rocker gear is represented; the Goldies, Bonnies, Dommis, dustbin fairings, even a Norvin, and at the end, a couple of Japanese lightweights.... There was always a bit of real racing to inspire the 'go faster' look of the Rocker boys; these shots (above and below) of a racing Dominator 88 were taken at Mallory Park. A very tasty machine indeed, and worthy of imitation.

The Current: Mission Motors Electric Sportbike

In February of 2009, the best designed new-generation electric sportbike was unveiled by Mission Motors of San Francisco - the Mission One. It looked very much like the future of motorcycling, and the design of the chassis was developed by Fuseproject, the studio of industrial design savant Yves Behar. We'd been speaking with Yves and his CEO at Fueseproject, Mitchell Pergola, for over a year prior, about their concept of a zero-emission sports motorcycle with better performance than a gasoline engine. We were certainly intrigued by their vision, and expected something very interesting to come from their studio; Fuseproject makes some of the most advanced industrial designs in the world, their work has been exhibited in many museums - but they'd never before worked on a motorcycle.

Other high-profile industrial designers have dipped a toe into the motorcycling world, with varying success; on our best-results list goes Phillipe Starck's Moto 6.5 collaboration with Aprilia, and my worst-case has to be Giorgio Guigiaro's ruination of the lovely Ducati bevel-drive twin - the 860GT of 1975. Yves Behar's affinity for organic and unusual shapes seems to fit well with contemporary motorcycle styling, and the Mission One was as forward-looking as it needed to be to sell a new concept and technology.

On the technical side, the project included members of the Tesla Motors design team, who helped develop the Mission One's engine, its battery technology, and more importantly, the throttle response algorithm. The electric motor is a liquid-cooled, 3-phase unit developing 100ft-lbs of torque @ 0rpm; 100% of the engine's torque is available from a standstill to its top speed, which is targeted at 150mph. Moderating that power is the trickiest part of the e-bike business, which tames a beast into a civilized machine.

The onboard computer of the Mission One has a data acquisition capacity, meaning you can plug your laptop to your motorcycle and retrieve all your riding data, and 'tune' your bike with your computer. The engine management system is ultra modern, shaping the power curve and throttle response to varying conditions of load and traction and road speed. It's not simply an electric motor, it's a managed power delivery system. The chassis is perhaps the most standard aspect of the bike; top-shelf components like Ohlins inverted forks with TiN coating on the fork tubes, Ohlins rear shocks, Marchesini wheels, Brembo 4-piston monobloc calipers, etc. The brakes have a regenerative charging system - when applied, they send electricity back to the batteries. Recharging takes 2 hours from a 220v outlet, and costs under $2.

The goals of the Mission One project aren't just performance-oriented, although to be competitive in the real world, the bike must go as well as any available sportbike. The first major test of the Mission was in June 2009, at the Isle of Man TTXGP races for zero-emissions motorcycles, and the Mission One made 4th place. We couldn't imagine a more appropriate testing ground than the oldest race course in the world, to compare and develop a totally new branch of motorcycling. The Tourist Trophy was established in 1907 for exactly this reason - 'competition improves the breed' - and finally, the concept is coming full circle.

The Mission One was intended to be as 'green' as possible, with regards to the materials used in its construction, and how they might be recycled after use. Lithium-Ion batteries are the most 'friendly' available, and can be chipped and recycled, or the materials can be recaptured and reconfigured into new batteries. The bodywork materials are still being investigated - there is a new type of organic panelling under test, which uses feathers from the poultry industry rather than carbon-fibers, embedded in soy-based resin. The quills are hollow, making the material extremely light. It's intended that as many other components as possible are fully recyclable - no blown foams for the seat or pvc bits; according to Forrest North, one of the development engineers on the project, the goal for non-green materials on the bike was the brakes and tires; quite a lofty goal. Even the coolant for the electric motor will be low-impact, and they researched organic/biodegradable oils which can do the job. Castrol R, anyone?

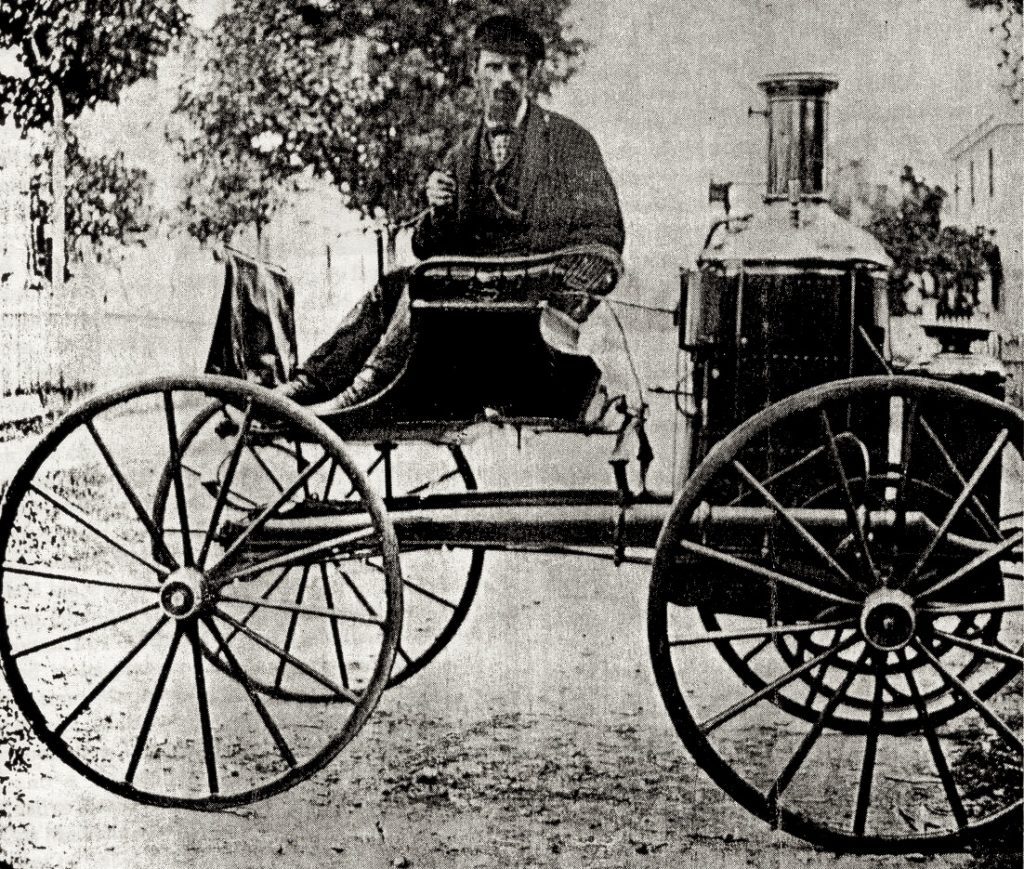

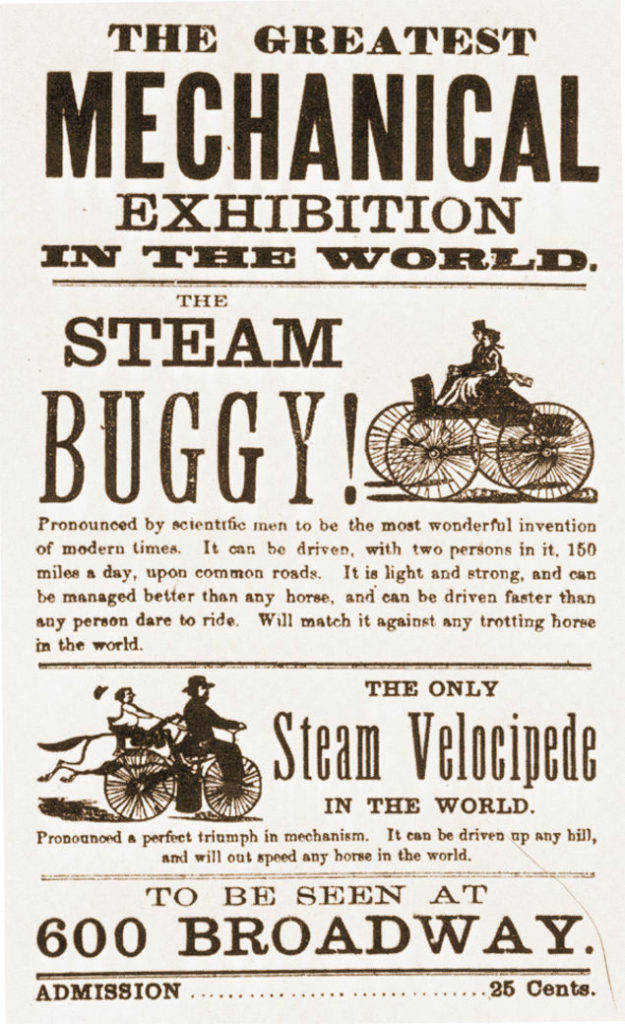

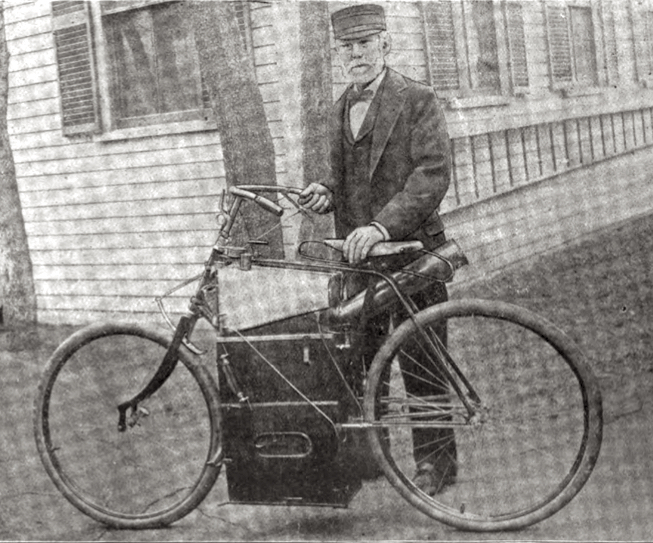

Sylvester Roper's Steam Velocipedes

The earliest years of motoring and motorcycling are poorly documented, as inventors were far ahead of the press of the day, and their inventions even predated categories to name their machines. What to call a self-propelled vehicle of 2, 3 or 4 wheels? The first known self-propelled vehicle, Nicolas Josef Cugnot's steam-powered 'Fardier', was built in 1769 by this military engineer, who envisioned it replacing the horse as a heavy-duty hauler. The first known image of a motorcycle was published in 1818, although it's unknown if that steam velocipede was ever built, or was meant as a satire of steam enthusiasts and inventors. Unless another claimant is documented, it appears Sylvester H. Roper invented the motorcycle in 1867/8, in the Roxbury district of Boston. Recent research suggests the 'other' claimant, Louis-Guillame Perreaux, built and patented his own steam velocipede in 1869, in Paris. These 'first' dates are squishy, but what's remarkable about Roper and Perraux is they built their inventions independently, and nearly simultaneously. Small, light, portable power units were nonexistent in the mid-1800s, so both men had to build their own steam engines to attach to the 'boneshaker' bicycles of the day.

Sylvester Roper, born in Francestown, New Hampshire in 1823, was a singularly brilliant individual, patenting sewing machines, machine tools, furnaces, shotguns, fire escapes, as well as building his steam-powered two, three, and four-wheelers, which he did not patent. His Steam Velocipede was created a few years after building his first Steam Carriage (ie, automobile) in 1863, in the midst of America's Civil War, while he was stationed at the Springfield Armory. His first Velocipede of 1867/8 used a very small steam engine, which Roper built himself. The engine was suspended from a forged iron frame -purpose-built for the machine- on spring steel strips, which absorbed many of the road shocks typical of the 'boneshaker' bicycle chassis. The front fork was also iron, and wheels were wooden with steel 'tires', 34" in diameter. Water for the engine's boiler was carried inside the rider's saddle! The engine had two pistons of 164cc capacity, each connected by a crank-arm and rod to the rear wheel. The total engine capacity was 328cc.

The rider controlled the Velocipede by rotating the handlebars forward - and thus the twistgrip throttle was born, decades before Glenn Curtiss claimed the same with his first motorcycles, which was again before Indian received general credit for this excellent idea! To stop the Roper, the rider rotated the handlebars backward, which pressed a steel 'spoon' onto the front wheel. Water was automatically fed from the seat to the boiler via a water pump actuated by engine rotation. The small firebox at the bottom of the motor was fed with charcoal, and a pressure gauge mounted on the steering-head kept the rider apprised of power, and danger.

The contraption worked, although perhaps not as well as his Steam Carriages, which had space for much larger engines, and carrying capacity for water and fuel, which meant a longer travel range. The harsh ride of the wooden wheels with steel tires must have become tiresome as well, in contrast to his four-wheelers which used buggy springs for rider comfort...Roper postponed work on his Velocipedes for 15 years. In the intervening years, bicycle design had undergone a sea change, as in 1880, the Rover Safety Bicycle was invented, and rubber tires came into general use. These improvements must have spurred Roper to take up two wheels again in 1894, when Albert Augustus Pope commissioned Roper to make a new Steam Velocipede using a modified version of Pope's popular 'Columbia' safety-bicycle frame, with pneumatic 'Dunlop' tires. The intention of Pope (who by 1911 manufactured his own motorcycles) was to use the machine as a cycle-pacer on the incredibly popular bicycle racing velodromes of the day.

Roper designed a new steam unit weighing about 125lbs, making an all-up weight of the machine 150lbs. The bump absorption capacity of air-filled tires made it possible to solidly mount the engine to the frame, in the 'right' location, with the weight low and centrally between the wheels. A single cylinder and piston of 160cc drove the bicycle via a long connecting rod, and a short crank at the rear wheel. Steam pressure was kept between 160 and 225psi (for hills), although the engine was tested to 450psi. The machine was good for at least 40mph, and carried enough coal for a 7-mile trip. The new machine was compact, light, and very fast, and Roper, pleased with his results, put in quite a few miles on his steamer, regularly riding a round-trip of 7 miles between his home in Roxbury to the Boston Yacht Club. American Machinist magazine noted, "the exhaust from the stack was entirely invisible so far as steam was concerned; a slight noise was perceptible, but not to any disagreeable extent."

Roper was happy to demonstrate his steam vehicles to the public, at fairs and exhibitions, and claimed his latest Velocipede, or 'Self Propeller' as he called it, could "climb any hill and outrun any horse." On June 1st, 1896, he rode to the Charles River Speedway in Cambridge, to show the local bicycle racers his new cycle-pacer. Several cyclists agreed to keep pace with him on the banked 1/3 mile cement track. The Boston Globe reported on June 2, 1896: "The trained racing men could not keep up with him and he made the mile in two minutes, one and two-fifths seconds. After crossing the line, Mr.Roper was apparently so elated that he proposed making even better time and continued to scorch around the track. The machine was cutting out a lively pace on the back stretch when the men seated near the training quarters noticed the bicycle was unsteady. The forward wheel wobbled badly...", and it seems track-side viewers rushed out to catch the slowing rider, who had died of a massive heart attack while riding, at age 73. As Roper controlled the throttle with a cord around his thumb, steam power shut down as he relaxed into the arms eternal night, having proved himself motorcycling's Speed Merchant, and its first martyr.

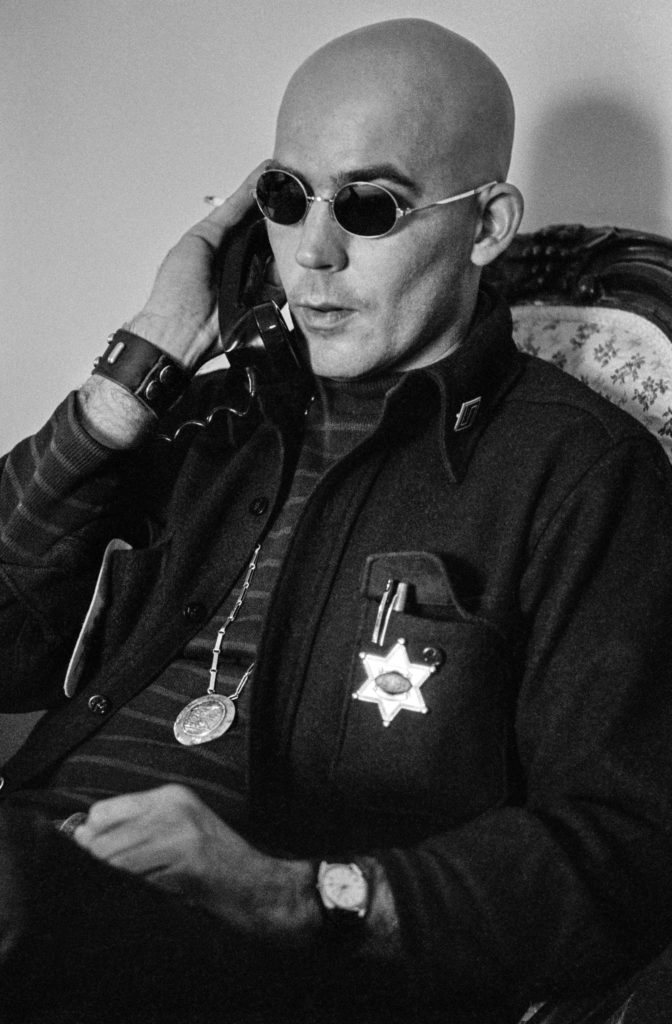

Freak Power: Hunter S. Thompson for Sheriff

[Words: Paul d'Orléans. Originally published in At Large Magazine]

He was a bitch from birth, or so said Virginia, the first woman to suffer Hunter Stockton Thompson, by pushing him complaining and bald into this world in 1937. He exited in the same state in 2005, taking a cue from Papa Hemingway and pulling the trigger on his inability to live up to a reputation for drink, drugs, mayhem, and - decades prior - the writing brilliance that secured a place in literary history. Long before a cartoon doppelganger overlapped and sucked the mojo from his real life, Hunter S Thompson was a ballsy and original human, the ‘pole around which trouble would occur’ according to a schoolboy chum. His authenticity was born of character, and not as in –acting; a charismatic little provocateur, he led a local street gang, who all agreed Hunter could ‘out think and out perform you’.

Thompson’s father Jack croaked a week before his 15th birthday, and Virginia washed her pain with booze. Hunter capped his high school career in Louisville with a month in jail for car theft, so never graduated, enlisting in the Air Force instead…but not until shooting every boat in the local marina beneath the waterline, sending most to the Ohio’s muddy bed. His early (but honorable) discharge in June ’58 might have been a summary of his whole life – “this airman, although talented, will not be guided by policy. Sometimes his rebel and superior attitude seems to rub off on other[s].” Reasons to live.

Thompson could ride bikes, shoot guns, and swallow drugs on par with any Angel, and his internal bullshit detector guided the story on this gang of romanticized losers. Motorcycle clubs had been chum to a media frenzy since 1947, when LIFE magazine ran Barney Peterson’s faked-up shot of a badly listing Eddie Davenport aboard a Harley-Davidson in Hollister. A patently false account of the Hollister street party - ‘Cyclist’s Raid’ - followed in Harper’s, which metastasized into ‘The Wild One’ movie. Thus began decades of shitty treatment for bikers, and demonization of the Hell’s Angels and most motorcyclists the press. Angels they were not, but any real societal impact was minimal, barring their glamorization as post-War boogeymen. In the context of such notoriety, ‘Hell’s Angels: the Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs’ was a huge success, and secured Thompson’s reputation as a journalist, although ‘Gonzo’, and the perfection of his writing style into literature, were as yet a few years away.

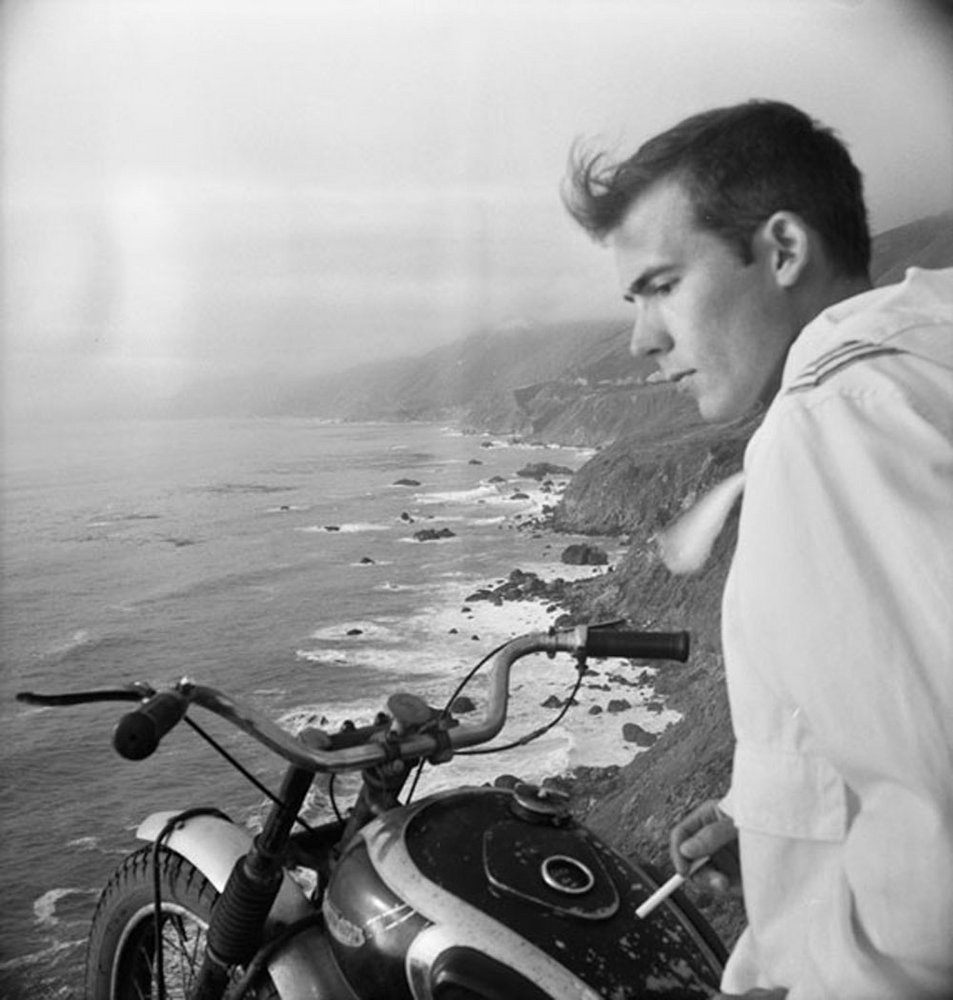

By late 1967, his small family decamped yet again from San Francisco, as Thompson envisioned an unpleasantly domesticated future there as ‘a magazine editor with a mortgage’. They headed for the mountains of Colorado. By 1968, royalties from ‘Hells Angels’ brought $15,000 (that’s 100 large today, an enviable sum for any writer), which Hunter turned into a brand new BSA A65 Lightning, ‘the fastest motorcycle ever tested by Hot Rod magazine’, and a few acres – Owl Farm- in the hamlet of Woody Creek, 14 miles outside Aspen.

Hot on the heels of the Thompsons, a significant chunk of the Summer of Love followed in 1969; hundreds of hippies came and stayed in the area. The mountain town buzzed from both hippies digging the spectacular views and clean air, and ‘land rapist’ developers who saw dollar signs in those same features. Older residents were simultaneously seduced by development money and its associated businesses, and mortified by hundreds of dirty hippies swarming their parks. Aspen’s police magistrate, restaurant owner Guido Meyer, decreed “Riots, hippies, beatniks. They are all the same; working from Moscow. Lawlessness and disorder will be our downfall,” and arrested anyone with long hair, handing out 90-day jail terms for vagrancy. The Aspen Times commented on Meyer’s tinpot tyranny, “having long hair, beards, and sandals is not yet a crime in this country. His lack knowledge for, and respect of, the law, make his tribunal a mockery of justice.”

Meyer met his match in Joe Edwards, a 29-year old lawyer (and biker) with a civil rights background, who’d just been hired as counsel by the Snowmass ski resort. Highlighting Guido Meyer’s outrageous and unconstitutional antics in State court was easy pickings for Edwards, as Meyer had neither law nor police training; both Meyer and the bulk of the town council were shortly ejected. Edwards noted, “They got their ears boxed, and the police chief was fired and the entire city council was ousted.” Thus Joe Edwards was an instant hero, and Hunter S. Thompson had a flash of insight: the swelling population of hippies and heads just might elect a new set of politicians. Thompson dubbed this ‘Freak Power’, and became Edwards’ de facto campaign manager for a run for mayor of Aspen in 1969. “The Old Guard was doomed, the liberals were terrorized, and the Underground had emerged, with terrible suddenness, on a very serious power trip. Throughout the campaign I'd been promising, on the streets and in the bars, that if Edwards won this Mayor's race I would run for Sheriff next year … but it never occurred to me that I would have to actually run.”

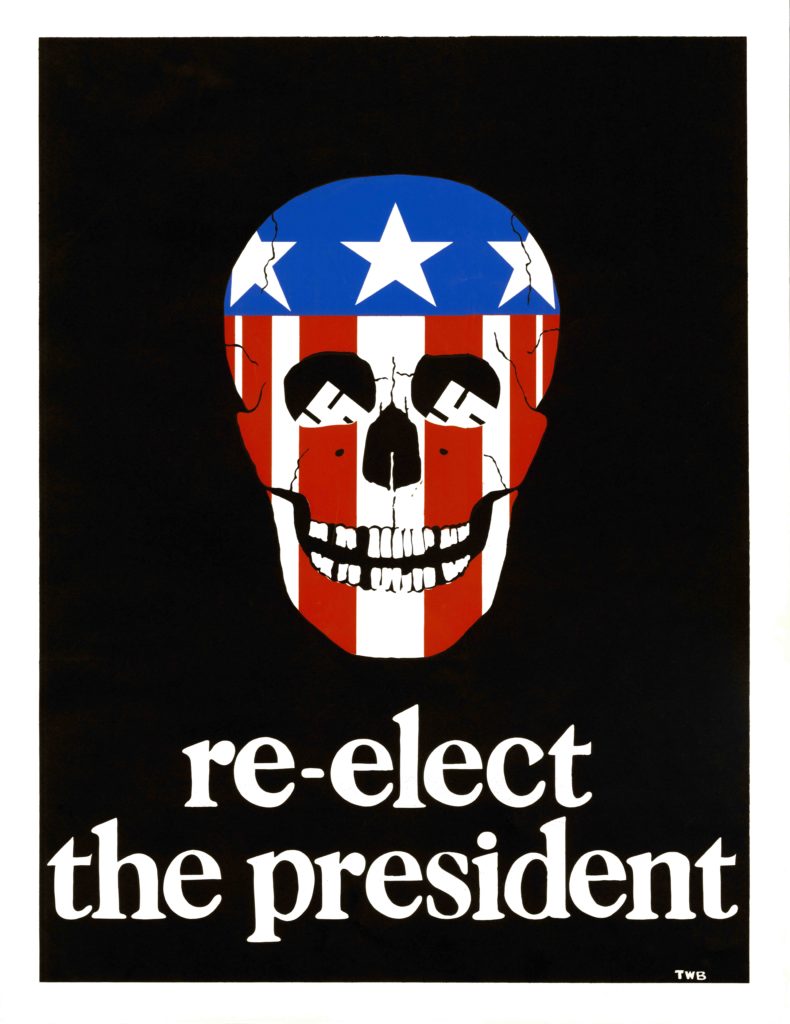

Edwards lost by 6 votes, but Thompson, his personal and artistic powers peaking, ran anyway, on a nationally watched ‘Freak Power’ campaign, whose logo was a double-thumbed fist clutching a peyote button, superimposed over a sheriff’s star. He brought real media savvy to the small town, buying radio time and producing a surreal TV ad of Hunter riding an enduro motorbike along a gravelly mountain road. Novelist James Salter (the best writer you’ve never read) narrated: “Hunter represents something wholly alien to the other candidates for Sheriff: ideas. And, a sympathy towards the young, generous, grass-oriented society which is making the only serious effort to face the technological nightmare we've created. The only thing against him is, he's a visionary. He wants too pure a world.”

Thompson was a well-known journalist for ‘Hell’s Angels’, but his gonzo antics were not yet the stuff of legend. Still, his campaign pointed the way towards his literary future, the start of both his legend and downfall. He knew in his heart his bid for Pitkin County Sheriff would fail, but damned if he wouldn’t go out with a pyrotechnic, psychedelic circus. “Why not run an honest freak and turn him loose, on their turf, to show up all the normal candidates for the worthless losers they are and always have been?" The campaign was a gesamtkunstwerk, with writing, video, radio, posters, and even Thompson’s appearance contributing; he shaved his head to refer to his rival, the crew-cut Sheriff Carrol D. Whitmore, as ‘my long haired opponent’. Now an established resident of the area, he invaded town hall meetings wearing his trademark Converse All-Stars and shorts, but underneath the show and bluster was serious talk about dangers to the local environment from development and hunting and fishing, and railing against the ‘silly’ laws against marijuana. He also promised never to take mescaline on the job.

His campaign promises stretched far beyond the normal parameters of the job, and included building a large parking facility outside Aspen, tearing up all asphalt roads in town in favor of grass, and providing a fleet of public bicycles. Aspen would be re-named ‘Fat City’ to discourage development, and “the Sheriff’s office will savagely harass all those engaged in any form of land-rape." The Sheriff and his deputies would be unarmed in public, to discourage ‘blood-baths by trigger-happy cops’, and would put ‘dope dealers’ in stocks on the courthouse lawn, as ‘no drug worth taking should be sold for money’; marijuana users would be ignored. Hunting and fishing by non-residents would be banned. A police ombudsman would keep track of power abuses, and a new drug treatment center would educate schoolkids on drug abuse. An office would be established to detect environmental crimes. All this was a clear fight against unbridled Capitalism, but the tone of the campaign, its big-pupil teeth gnashing, scared the shit out of the locals. Even worse, Thompson’s energy turned people on, and it was clear he had a lot of support. His ‘straight up Mescaline platform’ was pure druggy Dada, the coyote trickster path to Truth, and enough folks could see the wisdom beneath the madness that he almost won.

It took a cabal of Republicans, Independents, and Democrats (the ‘RID’) to foil the plan; they agreed not to run candidates against each other, and fight Freak Power together. There were threats of violence of course, so Aspen police recommended the Freak Power campaign offices be moved out to Thompson’s ranch, and that they arm themselves. The night of the election, Owl Farm took on the paranoid cast of Fear and Loathing, with stoned, gun-toting Freaks sweeping the property with flashlights, tensed for the imminent attack.

Hunter considered his Aspen antics a failure before he’d even begun, and was too self-absorbed to acknowledge the long-term success of the Freak Power project. He was really a political Johnny Appleseed (who we’ve recently learned intended alcoholic applejack, not snacks for rosy-cheeked schoolkids). In the next election, the entire city council was ousted, and liberal candidates like Joe Edwards took office. The next sheriff, Bob Braudis, overhauled the office and was re-elected 5 times; he was a great admirer of Thompson, and wrote the forward to the book ‘Freak Power’ (where much of this information was sourced). Growth was also severely restricted in Aspen, maintaining its natural beauty and subsequently raising property values significantly. And the final coda, of course, is that Colorado became the first state to legalize recreational use of marijuana, a result dear to Thompson’s heart…the man who threw a pound of dope into a Kinshasa swimming pool rather than watch Muhammed Ali fight George Frazer.

Two years before he kicked his home state in the nuts with ‘The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved’, incidentally inventing a new form of literature, Hunter S. Thompson’s political lark exposed what was best about the man. He’d taken the hippies to task in ’67 for abandoning the civil rights movement and the New Left in favor of simply getting high, and pulled a political stunt not repeated until punk hero Jello Biafra garnered 7000 votes for mayor of San Francisco. Thompson’s last words were still on the rollers of his IBM Selectric when Juan Fitzgerald discovered him dead in 2005: counselor. It’s the word that sticks in your craw during Handel’s Messiah, that fearful and strange composition of awesome beauty. Beethoven uttered on his deathbed, ‘and he shall be called Wonderful.’ Hunter took the next line. Johnny Depp generously re-created the Freak Power campaign’s double-thumbed mescaline-clutching fist as the cannon from which his ashes were shot over Owl Farm.

The Vintagent Selects: 'Not So Easy'

https://vimeo.com/236935464

The Vintagent Selects: A collection of our favorite films by artists around the world.

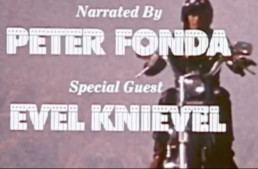

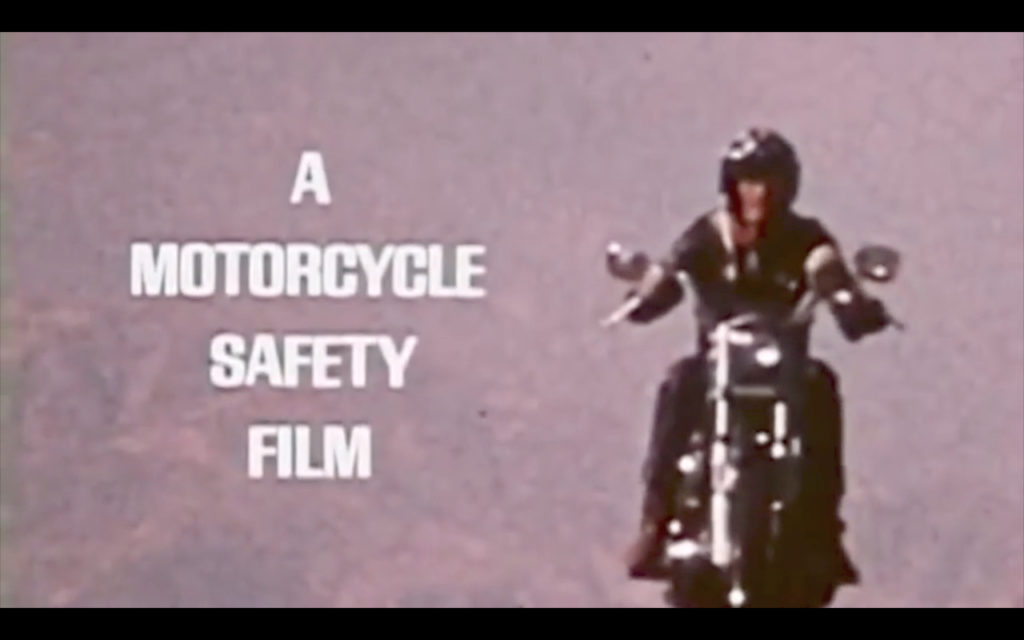

NOT SO EASY (1973)

Run Time: 17:57

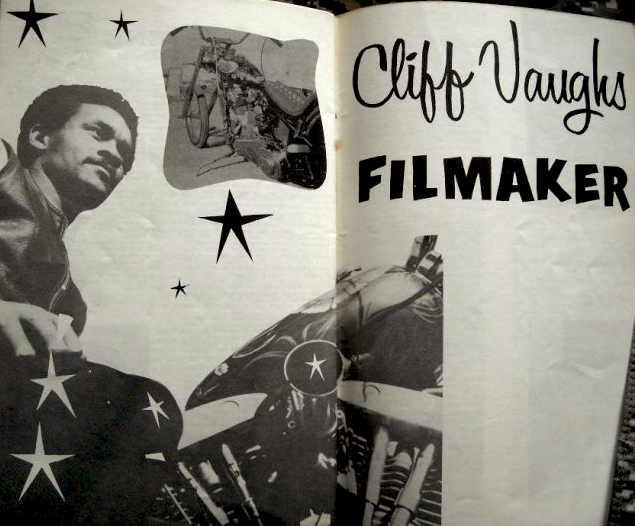

Producer: Cliff Vaughs/Filmfair Communications

Director: Cliff Vaughs

Associate Director/Writer: Norman Rose

Editor: Phil Content

Director of Photography: Harry Winer

Assistant Cameraman: George Leskay

Sound: Conrad Rothman

Original Music: Jeff Hathaway, Bob Tomasky, John Webb, Terry Boylan, Frank Blumer

Key Cast: Peter Fonda, Evel Knievel, Cliff Vaughs, Wendy Vaughs

THE FILMMAKER

Cliff 'Soney' Vaughs was a chopper enthusiast and Civil Rights worker in the early 1960s, spending time in the South with the SNCC as an official photographer and activist. Returning to Los Angeles in 1965, Vaughs worked at KRLA producing stories, and making films such as 'What Will the Harvest Be?'. In 1968, he met Peter Fonda while reporting on Fonda's arrest for marijuana possession; the two discovered a mutual interest in choppers, and discussed Fonda and Dennis Hopper's idea for a 'new Western' with motorcycles.

Cliff Vaughs was named Associate Producer of what would become 'Easy Rider', for which Vaughs provided the title, critical parts of the story (from events in his own life - like being shot at in the South on his chopper), and the two iconic choppers in the film, 'Captain America' and 'Billy', which he built in collaboration with Ben Hardy. When Columbia Pictures took over production of Easy Rider, Vaughs was bought out of his contract as Associate Producer, and his name never appeared in the credits.

In 1972, in response to a wave of motorcycle fatalities during a great boom in motorcycle sales to new riders, Vaughs filmed 'Not So Easy', and asked his friends Peter Fonda and Evel Knievel to appear, with Harley-Davidson supplying motorcycles. The film was shown in motorcycle rider education classes across the United States and Canada through the 1970s and early 1980s.

SUMMARY

While motorcycles are great fun, they're also 'not so easy', and need careful training to ride safely.

RELATED MEDIA

Top 10: Most Expensive Motorcycles

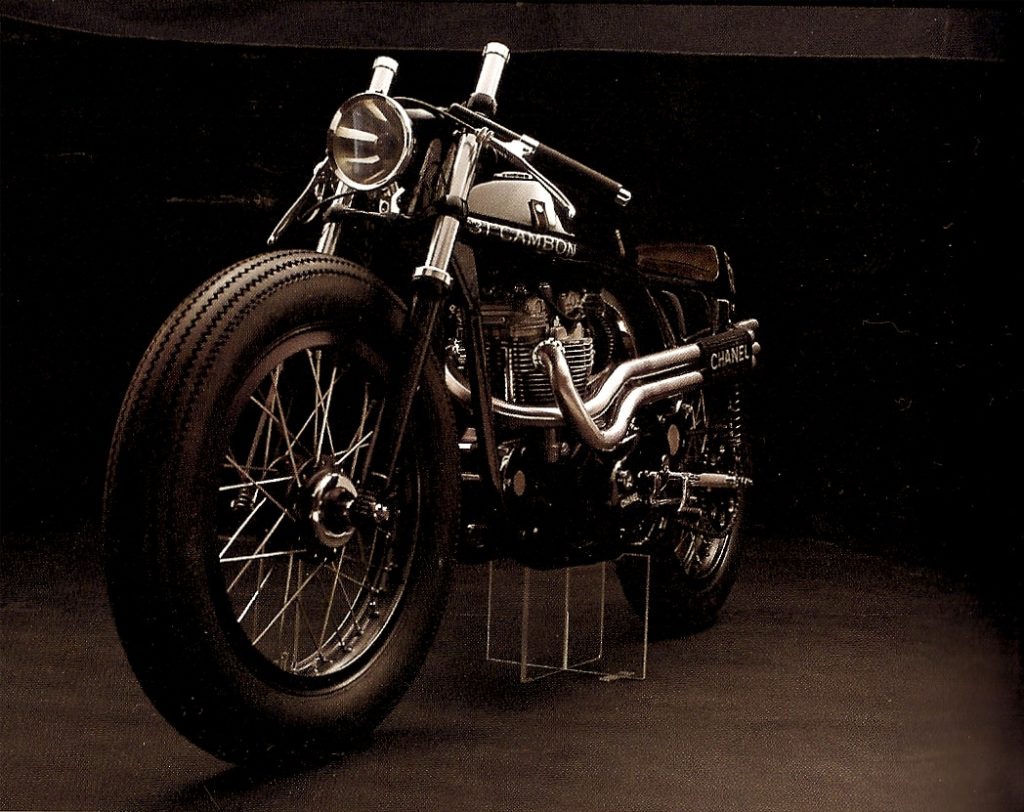

The Chanel Triton

July 2009: the fashion world was abuzz with two leaked photos (by Stéphane Feugére) of a custom-built 'Chanel Triton' being photographed for use as a prop for a Chanel photo shoot. Staff explained the photos were for their 2010 Spring collection, 'Starting Point', during the shoot on the Rue Royale Chanel boutique in Paris, during Fashion Week. The photos were no surprise to The Vintagent, as we'd watched the bike come together during the year, and were curious how this beautiful problem child would be received by the world.

Models Lara Stone and Baptiste Giacobini were draped over the bike, and the Triton wasn't merely used for a photo shoot; Karl Lagerfeld, the infamous Creative Director of Chanel, featured the Triton as the principal prop of his latest film - 'Vol du Jour' (the film is nonfunctional on the Chanel website, watch it below). In the film, Stone and Giacobini shoplift clothing from various Chanel shops in Paris, and escape by stealing the Triton! A plotline with a sense of humor...but Karl should definitely keep his day job, as his films aren't nearly as polished as his clothing, or his image.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hEHJnMh4skA&feature=youtu.be

The Triton was built as a collaboration between several French creatives: Daniel Delfour (builder of the Norton Alla'Verde hybrid, and a violin maker by trade), Vincent Prat (Wheels&Waves founder), and Frank Charriaut (an original Southsider, and former Chanel designer...which may have something to do with the Triton...), with paint by Momo. It was also born into trouble, being built without the the permission or knowledge of Chanel themselves. While Karl Lagerfeld loved the Triton, and rented it for Chanel's advertising and his own film that year, lawyers representing the firm insisted all identifying logos be removed from the machine. The raison d'etre of the exercise thus defeated, the Chanel Triton was then completely dismantled, having been built for a purpose. Its parts were scattered to serve other projects, and it exists today only as photographs and a short film, an avant garde alt.custom before its time, that was appreciated by creatives, but destroyed by lawyers. Handkerchief, please.

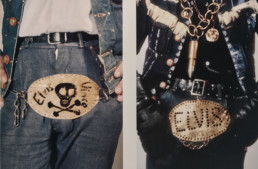

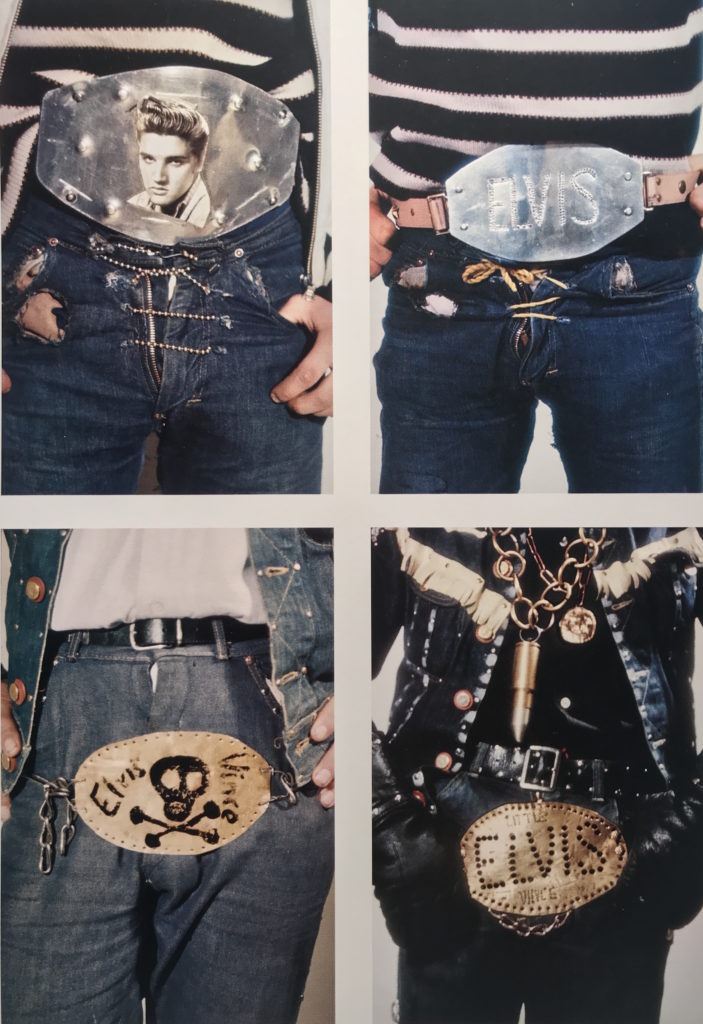

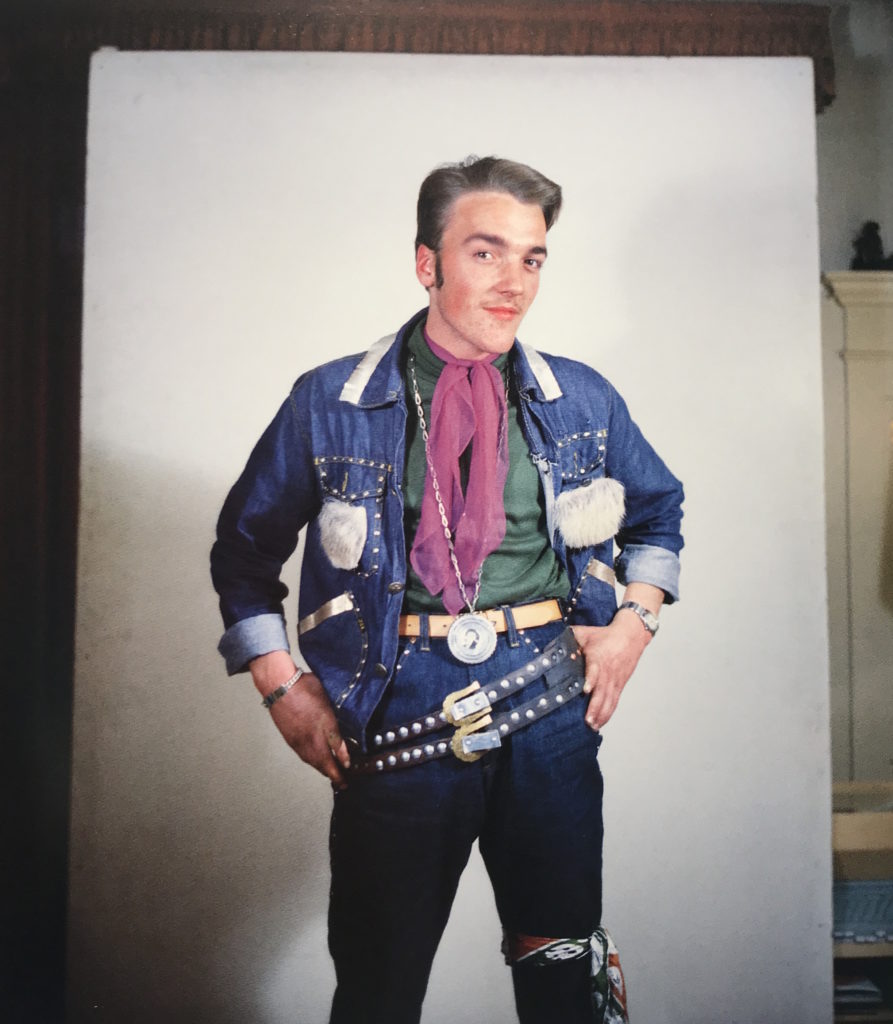

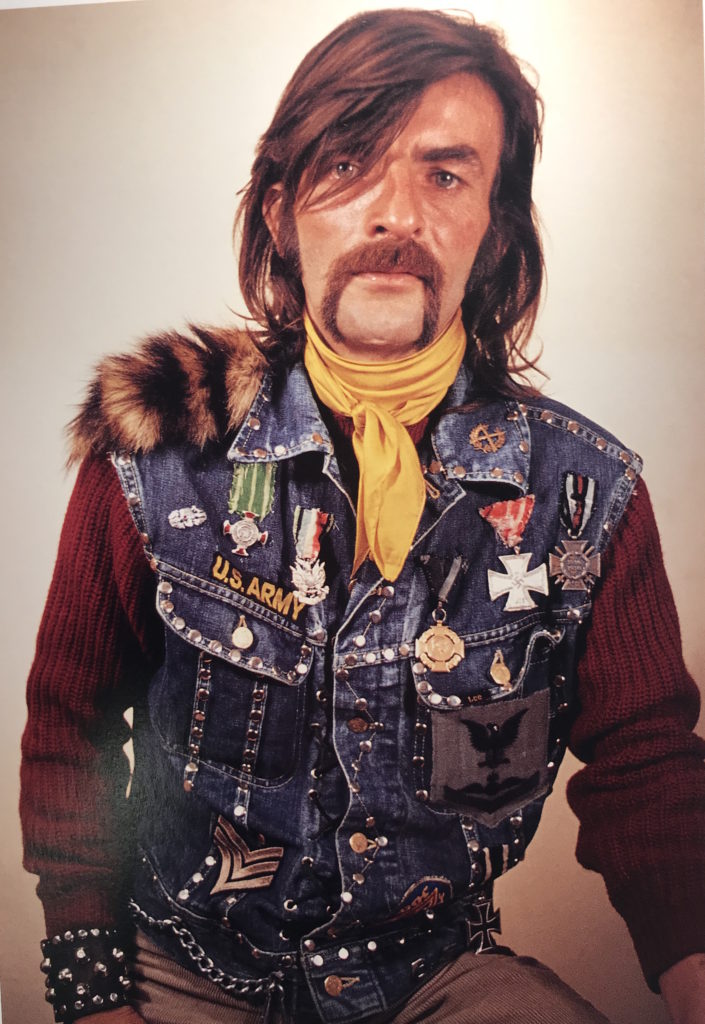

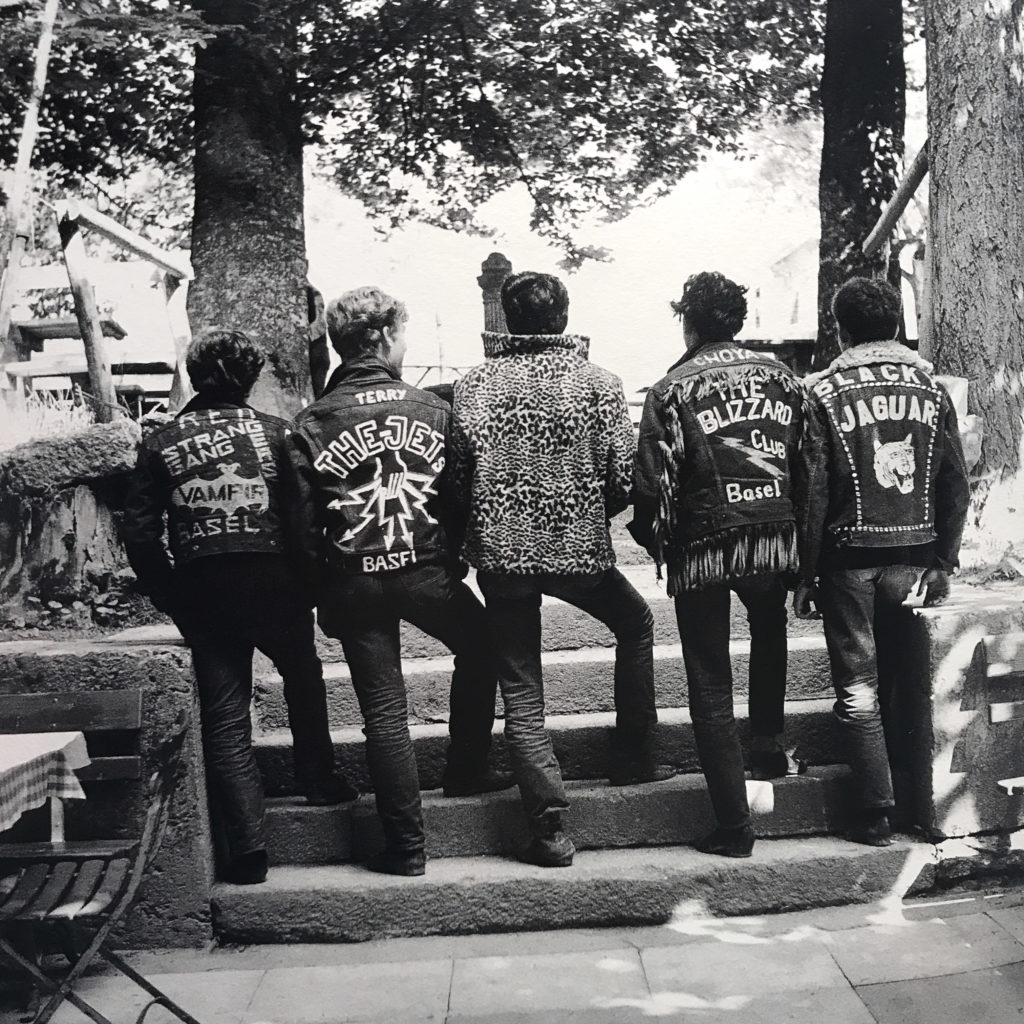

Karlheinz Weinberger

He was a 'grey man' in a suit, an ordinary worker, never missing a day in his job as an inventory clerk at the Seimens-Albis factory in Zurich, Switzerland. By all accounts, Karlheinz Weinberger was unassuming, quiet, kept to himself, and was a loyal employee. But in the evenings and on weekends, this self-taught photographer stalked the 'dark' places of the Swiss psyche, working under the pseudonym 'Jim' as a member of the gay beefcake photography club 'Der Kreis' in the early 1950s. If our story ended there, he would probably be forgotten as just another closeted gay man in squeaky-clean Switzerland.

Around 1958, he insinuated himself into a totally different 'scene' of young rebels and bikers, who squirmed under the thumb of Conformity, and grasped at the crack in the universe which was Elvis Presley, James Dean, rock music, and motorcycles... just like kids in the rest of the world! These youngsters (dubbed 'Halbstark' - half-strong - by Swiss media) home-grew a flamboyant style, which veered away from the American 'rebel' dress code of blue jeans, t-shirts, and boots. They wore belt buckles the size of hubcaps, with crudely chased images of skulls, Elvis, or Gene Vincent, favoring oversize artillery shells, animal skins, and horseshoes as necklaces. They wore cowboy boots with heels rather than engineer's boots. Better still, addressing the very source of Teen energy, they tore out the zippers of their blue jeans and replaced them with bolts, chains, or barbed wire, in an almost Medieval display of crotchery.

The Halbstark shaped a fiercely independent identity in their small, close-knit culture, and evolved in relative isolation, away from the prying eyes of the international press. After all, how many Swiss rock bands 'broke out' in 1958? Or ever? What part of Cool ever came from Zurich? The members of these gangs were 'Nowhere' and they knew it, but created their own life raft via subculture of fashion identity.

By the mid-1960s, the Swiss media began to take note of this homegrown oddity, and Karlheinz Weinberger's photographs of the gangs were published for the first time. He remained loyally embedded with his friends over the years, documenting their dissipation as the 60s wore into the 70s, and the era's corrosive elements began to take their toll.

In the last 7 years of his life, Weinberger was transformed from an obscure photographer to a celebrated cultural chronicler of a fascinating, lost subculture. In 1999 the first book of his photos was published - 'Karlheinz Weinberger' (Andrea Zust Verlag, Binder/Meyer/Jaegi authors), which is long out of print, and is now a collector's item. Before and after his death, Weinberger was featured in numerous exhibitions around the world, and his photographs are in the collections of major museums. He was born in 1921 and lived most of his life in obscurity, but when he died in 2006, he was a famous artist.

During the 1950s and early 60s, other pioneering artists working with motorcycle gangs as subject matter (Danny Lyon, Kenneth Anger, etc) produced rich and fascinating bodies of work with very similar themes. Let's call it the Zeitgeist of the 50s, which led these photographers and filmmakers into some interesting territory. A branch of Motorcycling evolved in the 1950s that was self-consciously 'antisocial', and brandishing imagery that was highly charged, threatening, or just plain offensive. They mined cultural turf that was anxiously avoided by 'straight' society (homoeroticism, fascist symbols, sadomasochistic hardware, blasphemous language). Motorcycles, symbolizing independence, fearlessness, and fun, became the perfect accessory for individuals who just didn't jibe with how they were 'supposed to be', as the rest of society (mostly, their parents!) desperately grasped for a period of normalcy after the horrors of global War and the threat of nuclear annihilation.

While the numbers of 'rebels on motorcycles' were relatively small in the US, Britain, and Europe, their powerful imagery stained the public's perception of Motorcycling for decades. Films about motorcycles during the 50s through 70s almost always featured violent gangs of ignorant thugs, with a few bright exceptions like 'On Any Sunday'. It took the concerted efforts of Soichiro Honda and his advertising team to shine a light back on Motorcycling as a fun pastime, allowing just regular folks to approach 'two wheels' without stigma for the first time since the 1930s. But damn, those thugs looked cool.

You can purchase a terrific compilation of Karlheinz Weinberger's work here: Rebel Youth: Karlheinz Weinberger.

Kop Hill - the Perfume of Authenticity

[Words: David Lancaster Photos: Dave Norvinbike]

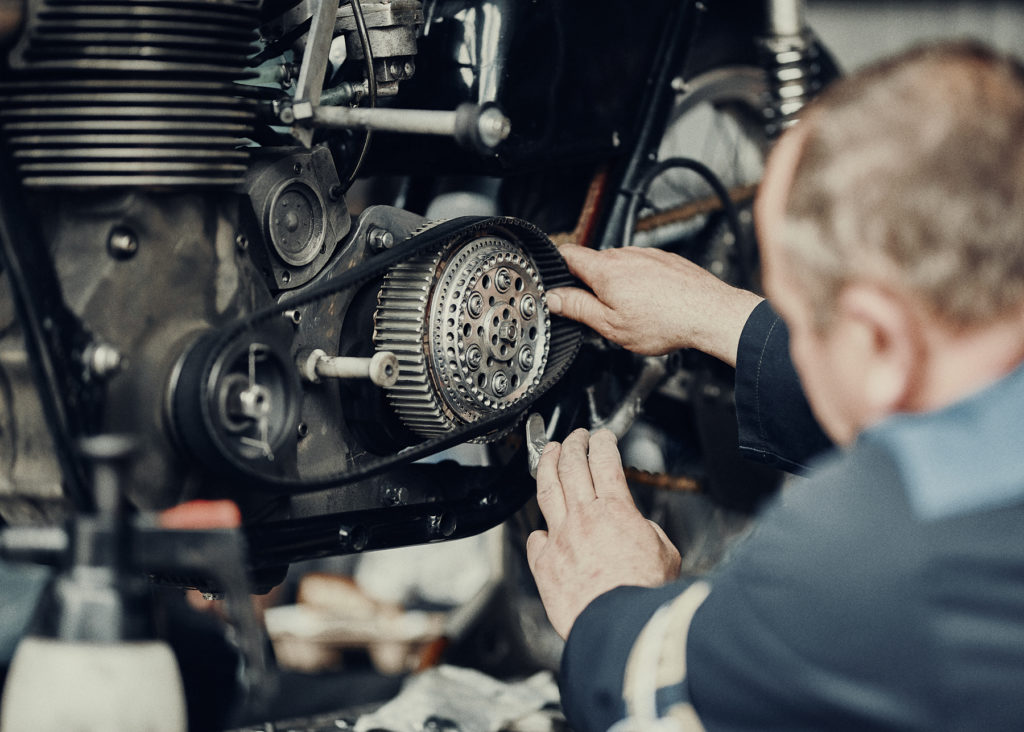

What explains an addiction to old motorcycles? They’re costly, dirty, noisy, not always reliable, but something keeps bringing us back for another hit. But what?

Well, they’re just great fun to ride. They’re involving. On an old bike you see, hear, even smell the cycle working beneath you. In an age of diagnostic servicing and electronic driver aids, they ask something of the rider; sometimes they ask a lot. But an older bike – running nicely, running fast – is a credit to its pilot-mechanic, not a computer. There’s also the appeal, for many of us, of riding back in time – older bikes have lived through history we can only read about. Doing so at pre-war venues such as the Montlhéry autodrome and the Brooklands speed bowl is a thrilling exercise in riding with ghosts; fast ones.

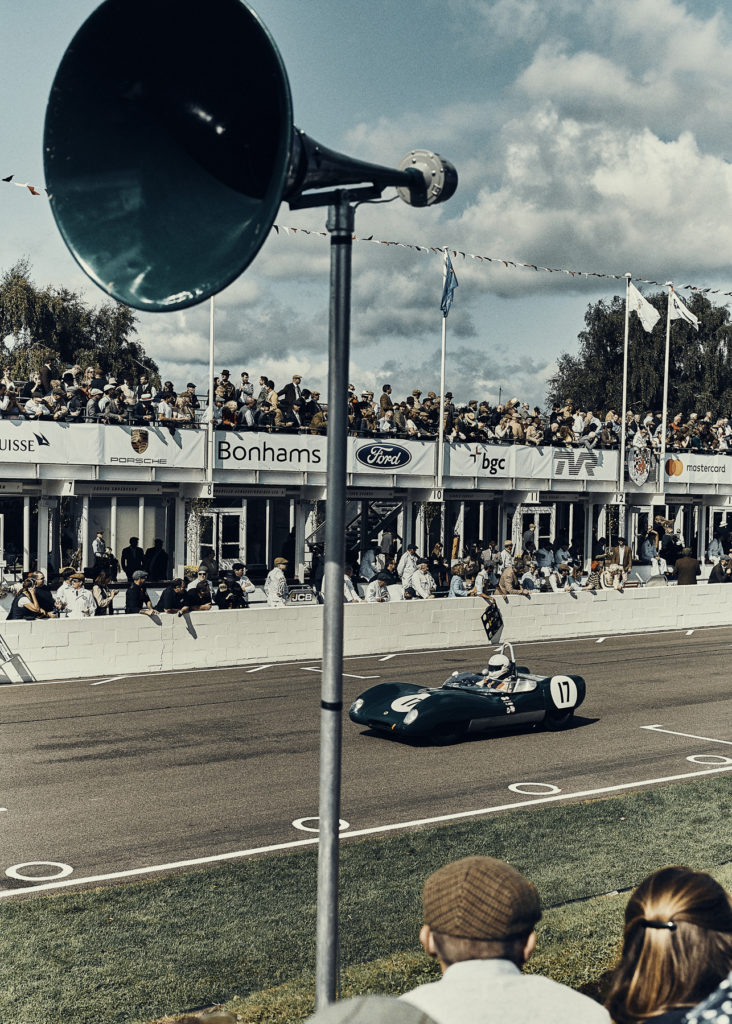

Kop Hill, in rural Buckinghamshire, has a history as rich as those historic venues, and it too has a lineage back to the pioneer era. The hill itself runs for just over a two-thirds of a mile, snaking gently into the English countryside with subtle turns on the way up. From 1910 until 1925 the Kop Hill speed trial was one of the country’s major motoring and motorcycling events, home to fierce competition between top riders and drivers of the day. These included the likes of Malcolm Campbell in his Talbot Blue Bird and Count Zborowski in his eight-cylinder Ballot.

Fastest of all was Freddie Dixon, who in 1925 on a 736cc Douglas set the outright record for two or four wheels by taking the timed section of the climb in just over 22 seconds, at a remarkable 81mph average. This, over a stretch of ‘road’ which was mostly loose gravel back then, bumpy and with a one-in-five climb at its steepest point, was a high velocity swan-song for the original event.

It has another claim to history, too. When in 1925 a spectator (who had been warned about standing too close to the action) was hit by a competitor’s car, the road-safety and political classes increased their opposition to motorsport events taking place on public roads, even if closed to traffic. The British establishment has been called a ‘committee which never meets’ and soon its various arms - by then including the governing bodies the Auto-Cycle Union and Royal Automobile Club - closed ranks and stopped all competitive riding or driving in the UK outside of purpose-built circuits like Brooklands.

Kop Hill’s closure in 1925 was a victory for a vocal anti-motorsport lobby in the UK. The Isle of Man TT races were established in 1907 because the Manx government took a more indulgent attitude towards racing than the rest of the UK. And the famous British racing green of pre-war Bentleys, and later Jaguars and Aston Martins, owes its adoption to mainland drivers and team managers racing in Ireland. The famous Gordon Bennett Cup had moved there as early as 1903, leading the local paper the Leinster Leader to note excitedly that Ireland would be ‘the battle-ground on which to decide the supremacy of the latest inventions to revolutionize locomotion.’ British lawmakers looked the other way and British teams took on the green of Ireland as an act of thanks, tribute and rebellion.

Since 2009, local enthusiasts have staged runs up the original Kop Hill for a cadre of mostly pre-1950 cars and bikes, with the numbers and quality of the vehicles increasing every year. Demonstration runs, of course, but amongst the open tourers with children nestled in the back (one was spotted happily asleep in an Alvis as the car headed off the start line), several hit high speeds from properly brisk take-offs. Unlike the short, sharp ascent of Brooklands’ Test Hill, here riders and drivers can charge through gearboxes and navigate the narrow lane, building speed all the time. The big shots turn out too: from the modest grandstand or watching from feet away along the length of the hill, spectators can see, hear and breathe-in Bentleys, Rolls Royces, Bugattis, Brough Superiors, Rudges, Vincents-HRDs gunning up a hill which is both longer and – should you wish – faster than you expect.

Proceeds from the two days of the September weekend go to the Heart of Bucks Community Foundation and since 2009 over £400,000 has been distributed to local charities. It’s all rather wonderfully British: a little chaotic at times, polite, run by dedicated amateurs. But it has an air of informality and stubborn democracy, in contrast to more rigidly organized events. As a result, Kop Hill retains a perfume of authenticity, redolent of the Century-ago pioneers of competitive motor-sport.

[For more history of Kop Hill, read this]

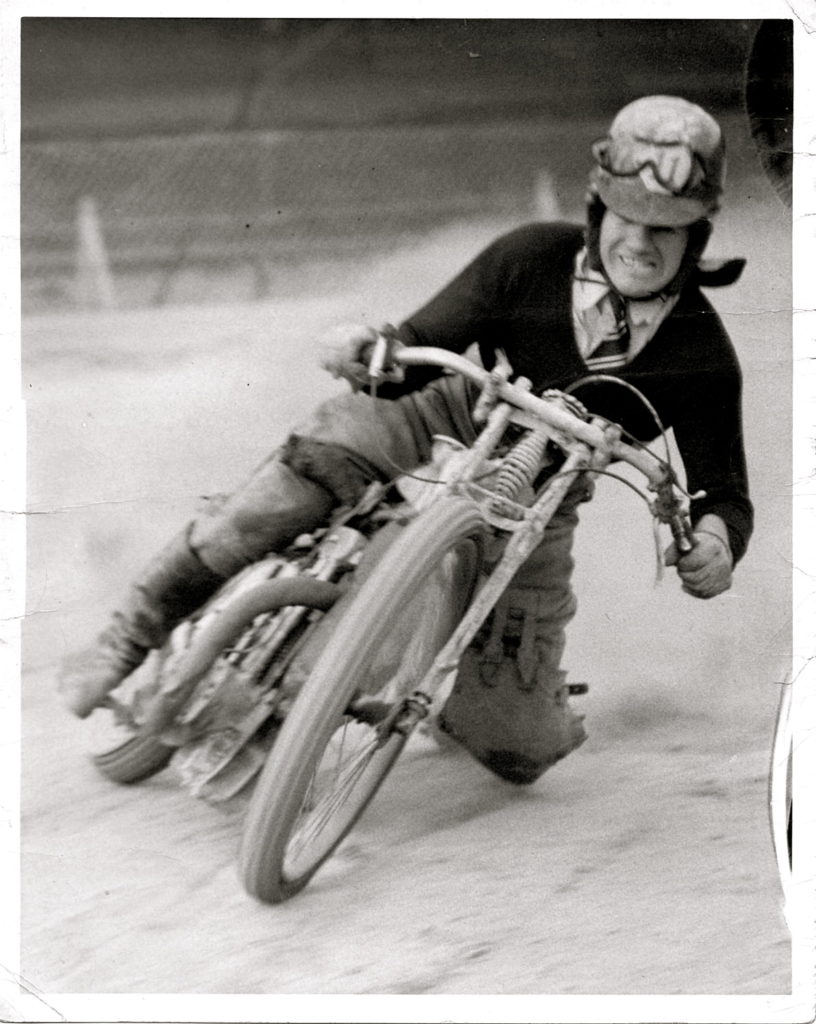

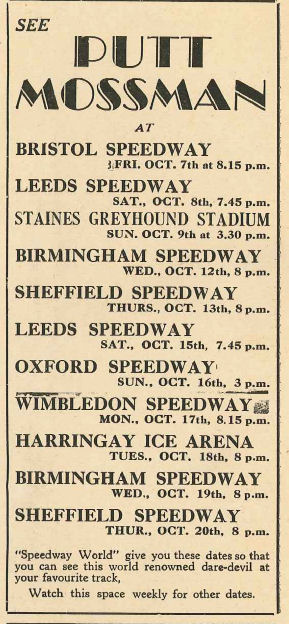

Showman in a Suitcase - Putt Mossman

[Words: Chris Illman]

Some 20-odd years ago, whilst browsing a Junk Shop in Greenwich (southeast London), I found a very scruffy suitcase gathering dust, filled with a pile of old newspapers. Closer inspection revealed some interesting stuff, including a mountain of photographs of pre-WW2 Speedway racing – a particular passion of mine! That set the heart racing; without wanting to appear too eager for fear of escalating the price, the obvious question was asked - “How much for this old suitcase full of Newspapers?”. The welcome retort was “Give us a fiver!”

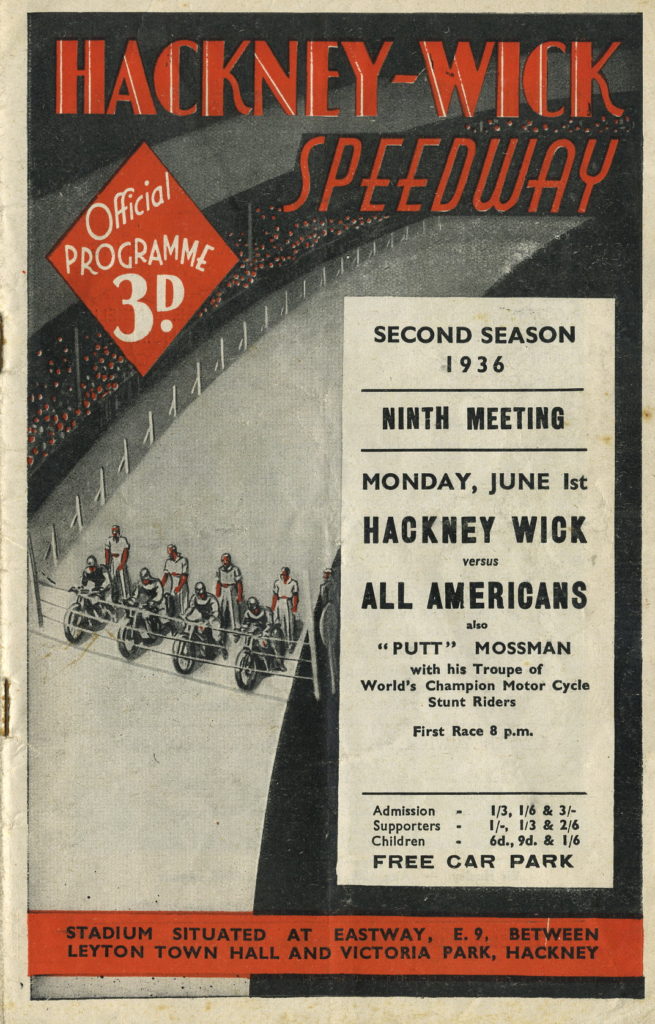

My anticipation was agonizing during the drive home, as there was no way to properly assess the contents of my prize until they could be spread out and sifted through. That humble suitcase revealed a treasure trove of material related to just one man; Frederick Lindop Evans. Fred Evans was the Manager of Hackney Wick Speedway team, and it quickly became clear that the case contained personal effects from his time as Hackney ‘Wolves’ Manager, covering the period 1935 until the outbreak of the 1939-1945 conflict in Europe. Fred Evans survived the War, but apparently he was never reunited with his treasured possessions, which remains a complete mystery. To relate Fred’s story and explore the entire contents of the suitcase is beyond the scope of this post, but after years of dipping in and out of the thousands of items, many stories emerge.

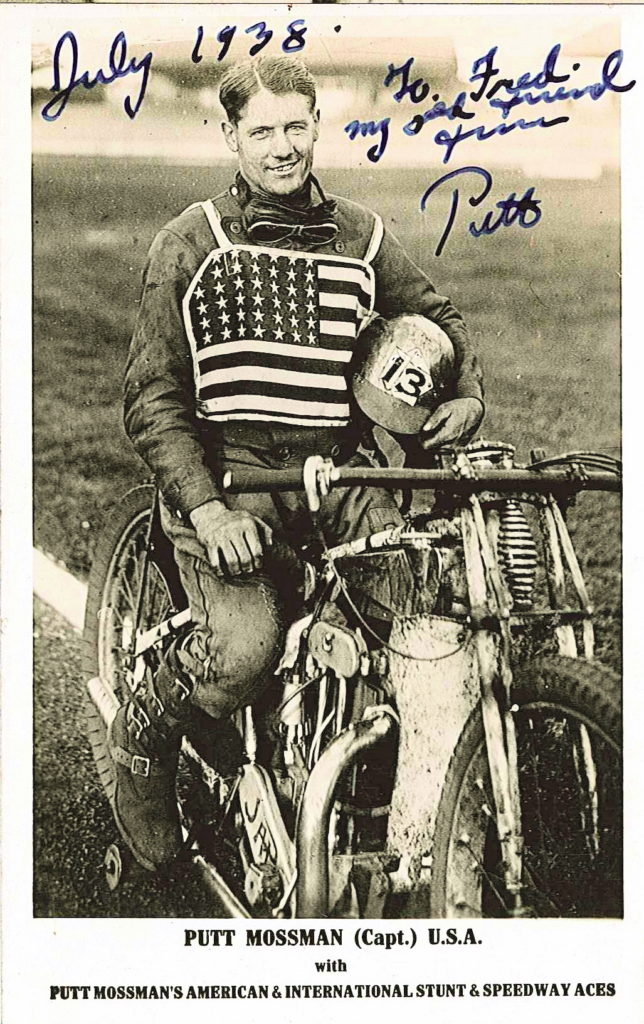

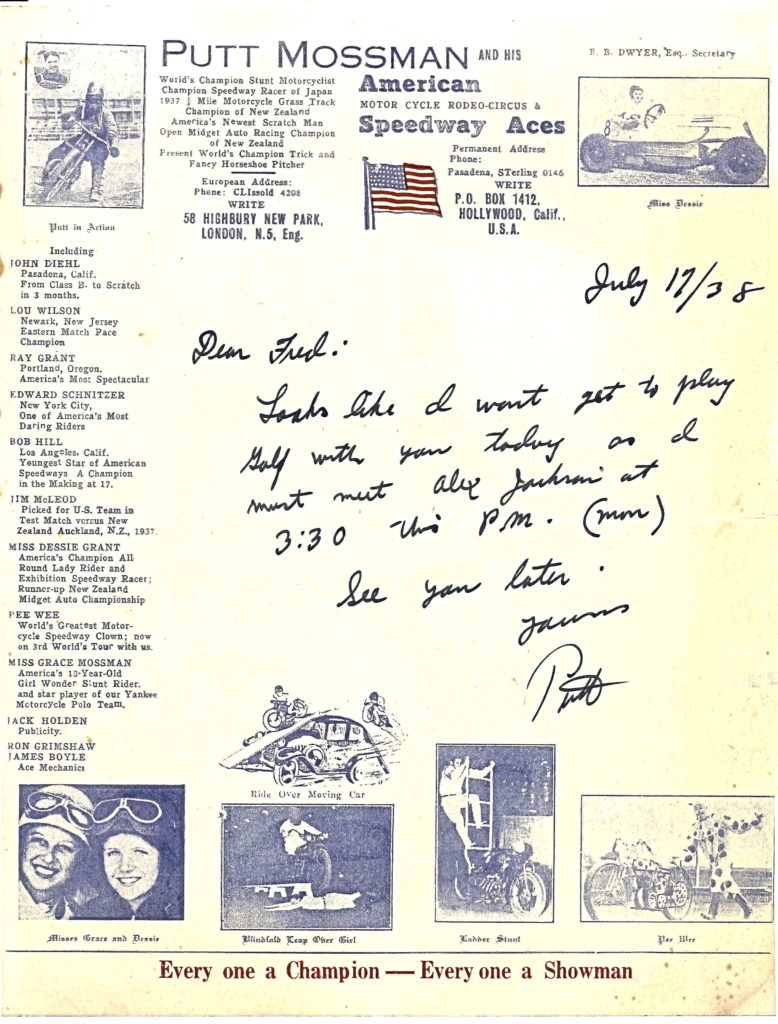

And this is where Oren 'Putt' Mossman comes into the story. Putt was born in Iowa, USA in 1906, and traveled the world as a stunt rider, midget car racer, boxer, actor, and all around carny and showman. Fred Evans was great friends with Putt! During these Pre-War years, Speedway in England was big; indeed for a while, it was Britain’s top spectator sport. Fred and Putt shared much in common. The most significant pattern to emerge is a shared obsession with ‘Self Publicity’. As well as the obvious Speedway connection, they both loved to play Golf and as it happened, Fred was a member the exclusive Chorleywood Golf Club in Middlesex. From Fred’s diaries it seems that whenever Putt was in London, they tried to fit a game in at least once a week. Given that Fred and his Hackney Team were touring the Country at least 5 nights a week, where they found the time is beyond belief, as Putt’s schedule was probably just as hectic!

On occasions their schedules didn’t work out - see the note from Putt, with his wonderful Letter Headed paper proclaiming his achievements - saying sorry that golf would not be possible on July 17, 1938. Both appear to have been accomplished Practical Jokers, if examples of the outrageous tricks they played one another and on the Hackney Riders are anything to go by! Showman Putt needed an opportunity to present his exploits to big audiences, and it seems that our Fred was also keen to make the most of the large attendances at Hackney by adding new attractions to his Speedway meetings. The synergy was obvious and Putt’s Stunt Show fitted the bill perfectly for the intervals. The Hackney Wick crowd was already huge, but the added attractions swelled the gate, giving a mutual benefit to both parties. Putt of course would go on to spend a great deal of time in England, and his schedule of shows defies logic. My god, he must have had some stamina!

A quick glance at the attached Press Cutting (above) will show how he managed to pack in more than 11 shows across the country in just 13 days - it is said that he once did 100 shows in England in just one year. Given his propensity to push himself to the limit and beyond, he had terrific self-confidence, not allowing himself the luxury of a few days recovery should he tumble (and tumble he did it appears, on many occasions!).

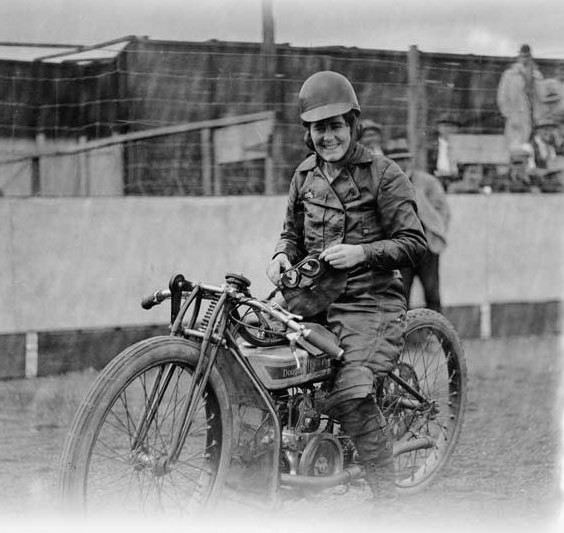

As well as the Stunt Shows, Putt was a Speedway rider of some note, and appeared with the American team on a regular basis. A photograph of the Tram outside the famous Hackney Empire Music Hall and Theatre, clearly expresses the sentiment that ‘It pays to advertise’. Wonderfully evocative of pre-war London, it encapsulates the Mossman/Evans connection via a banner promoting an American Speedway Team vs. Hackney Wick match. The photo of Putt in full ‘Leg Trailing’ mode not only demonstrates his skill as an accomplished Speedway rider, but shows him casually wearing a pullover and a tie!

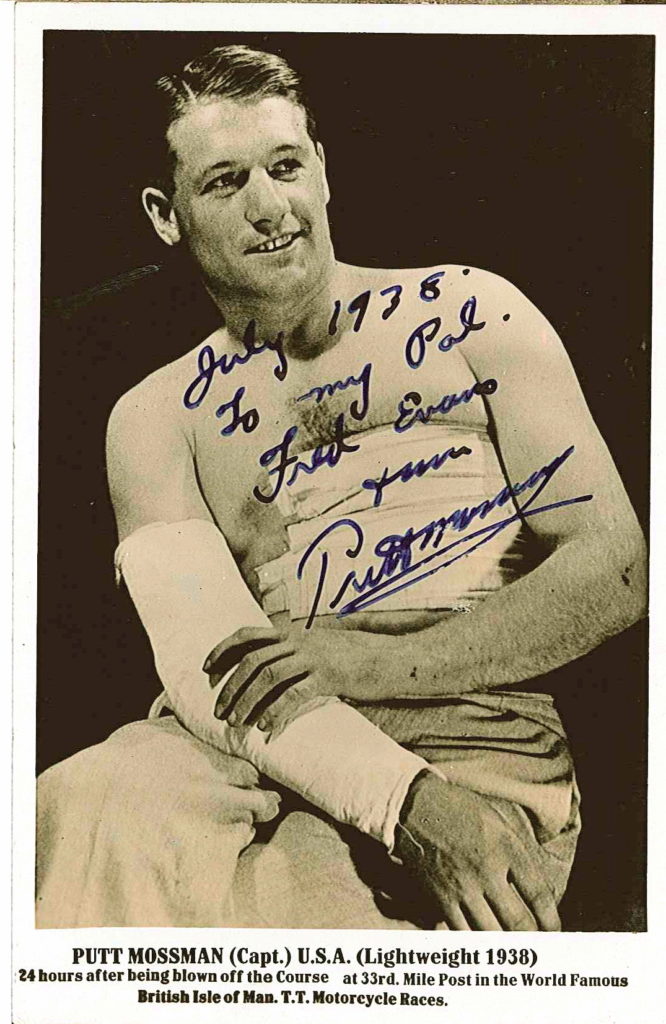

During one of his many visits to Britain, Putt participated in the 1938 Isle of Man Lightweight TT, on an OK Supreme. Sadly, he did not finish, falling at the 33rd Milestone and suffering a serious arm injury. As if to wear his failure as a glorious Badge of Office, he printed up the Post Card below, which, like so many of the others found in the case, is personally signed by Putt to Fred Evans.

Incidentally, whilst on the subject of the Isle of Man, it is a little known fact that Putt also did the Stunt Riding for the iconic film ‘No Limit’ that starred George Formby as a TT Rider which was actually shot in the I.O.M in 1935. Among his stunts, perhaps one of the most dramatic was staged at the Hackney Wick Stadium. A makeshift scaffold was erected, and a ramp descended from the top of the Grandstand, sweeping down to a take-off ramp, where Putt was propelled though the air to land in 15” deep pool of water. As if this feat was not daring enough, the pool of water was topped off with burning petrol! Although the leap was a spectacular success from the crowd’s perspective, personal recollections of a spectator reveals that a heavy landing resulted in a broken and bloody nose for Putt. In true showman’s spirit, he completely disregarded his injuries, picked himself up, and rode a lap of honour, to the great acclaim of the assembled masses.

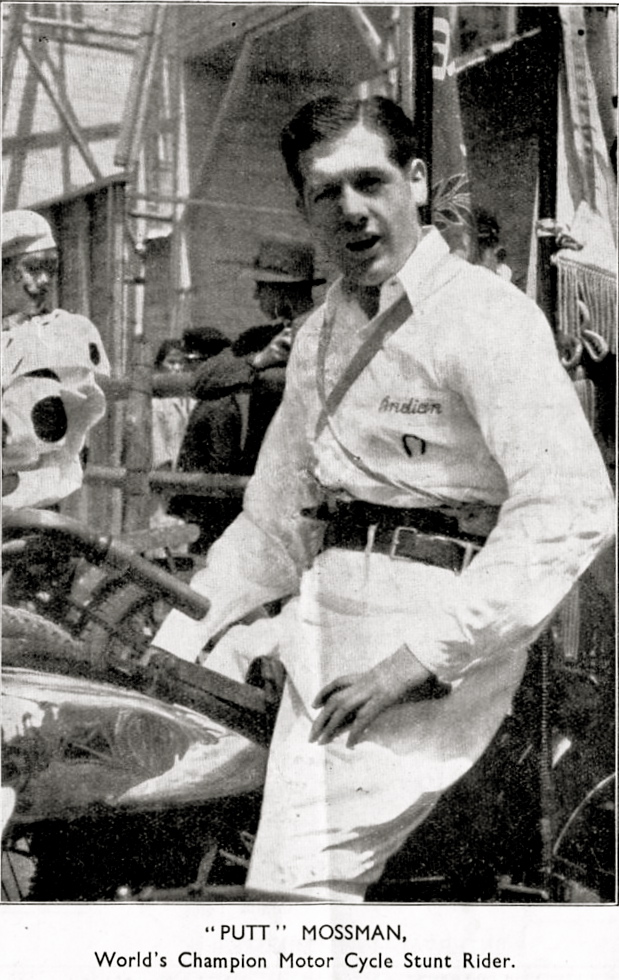

Although well known for his Ladder Walk, the top photo in this article, which has been published on several occasions I believe, is again rather special as it is personally signed and dedicated ‘To my good friend & Pal, Fred’. The bike incidentally, is an Indian 4-cylinder job, with an amazing exhaust system! It was an expensive machine then; I wonder where it is now? These images are a small selection of the treasures associated with Putt that came from this wonderful goldmine of Pre-War Speedway ephemera. Stunt Riding was effectively a ‘Part Time’ job for him; amongst other things, Putt was, or had been, a Speedway Champion [Japan 1936] a Champion Shoe Thrower [Horseshoes], Midget Car Racer, Boxer, Baseball Player and Vaudeville artist. His public swan song was an appearance on the Johnny Carson Show, pitching horseshoes between Johnny's legs! What a man.

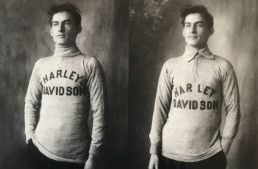

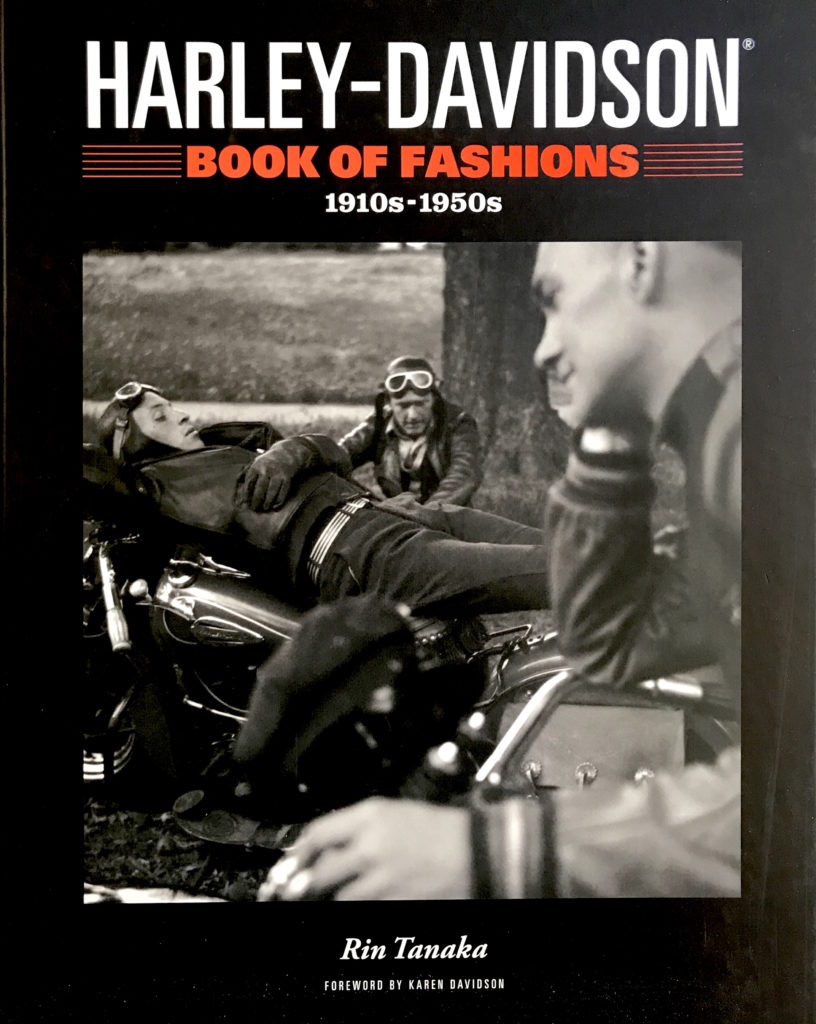

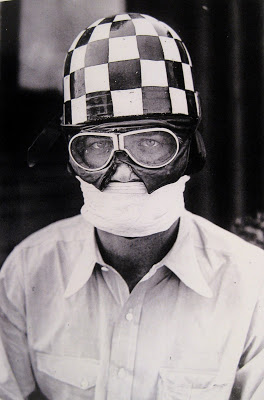

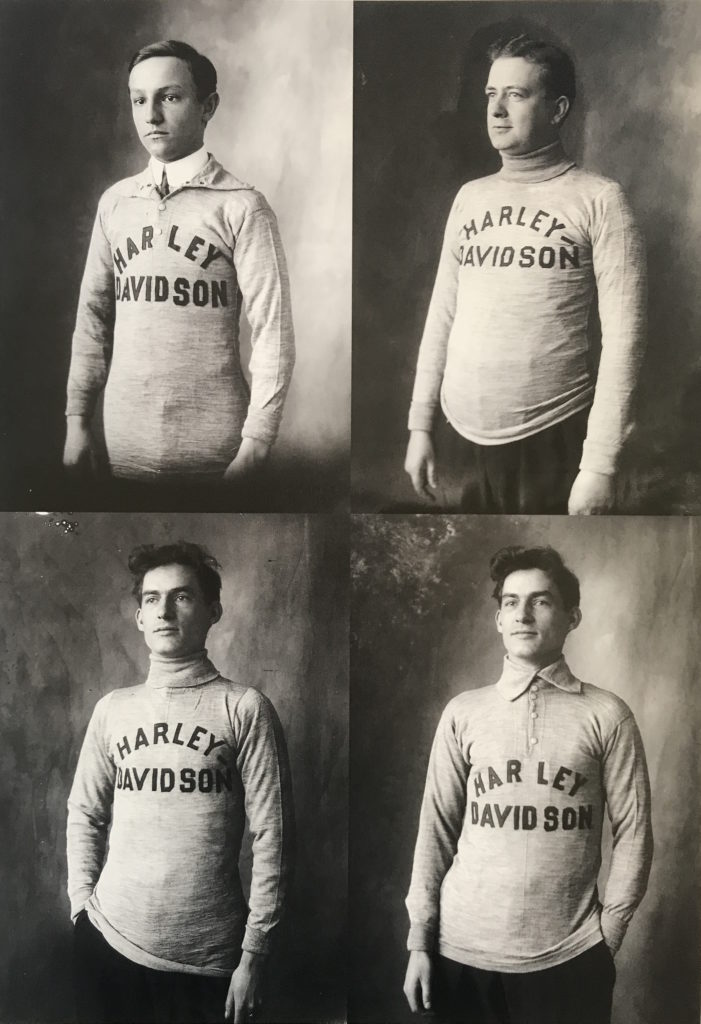

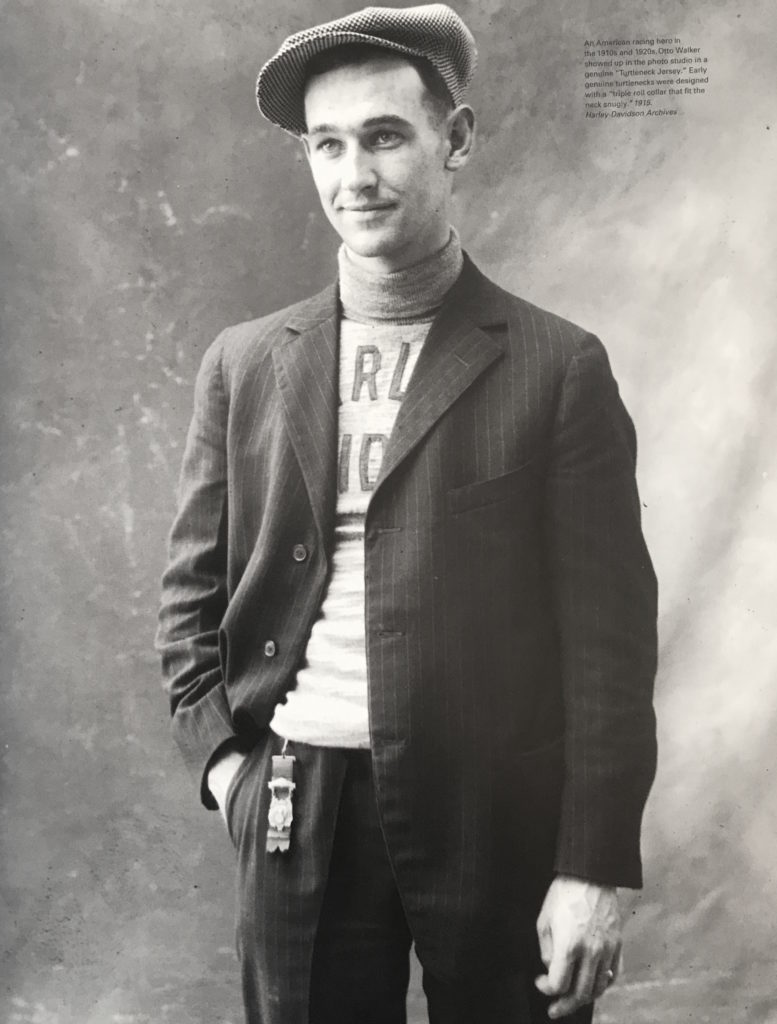

Book Review: Harley-Davidson Book of Fashions

Rin Tanaka has outdone himself. The master of books on vintage clothing has published the definitive history of American motorcycle gear, 'Harley-Davidson Book of Fashions: 1910s - 1950s', after he was given rare access to the Harley-Davidson Museum and Archives, with their over 100,000 photographs spanning their entire history from 1903 to the present. H-D was one of the first motorcycle manufacturers to hire professional photographers to document their progress, and kept photographic and documentary records of their various lines of accessories which they offered from 1914, along with the entire run of The Enthusiast magazine and contributions from various dealers, clubs, and race promoters.

With access to this vast array of totally cool stuff, Rin couldn't fail to make an outstanding book. His self-published specialty has been a series of obsessive picture books documenting, in chronological order, various styles of motorcycle jackets - Motorcycle Jackets: A Century of Leather Design and 'Motorcycle Jackets: Ultimate Bikers's Fashions (Schiffer Book for Collectors)

' - and helmets ('The Motorcycle Helmet: The 1930s-1990s

'), t-shirts (My Freedamn! 3, 4), etc. He was also granted the rights to publish recently found documentation (photos and film) of Steve McQueen's foray into the ISDT, which he published as '40 Summers Ago', which I can't recommend highly enough - you can purchase Steve McQueen 40 Summers Ago....Hollywood Behind the Iron Curtain (Cycleman Books)

here.

One doesn't really think of 'Fashions' per se when the name Harley-Davidson comes up, but Tanaka makes a compelling case that their extensive line of Motor Clothing, produced for the last 90-odd years, has made a sartorial impact far beyond those who simply ride H-D motorcycles. The book, which is large format (11" x 14") and beautifully printed, moves between official publications / catalog photos, and shots of contemporary riders actually using the purpose-designed clothing and accessories in races, club events, official business, and the military. Each chapter focuses on a decade (1910s, 20s, etc), and shows the evolution of 'gear' as motorcycling itself changed and conditions demanded new and better products. He also explores how customization of clothing (and by implication, the bikes too) developed from various small accessories into the blaze of custom culture in which we now live.

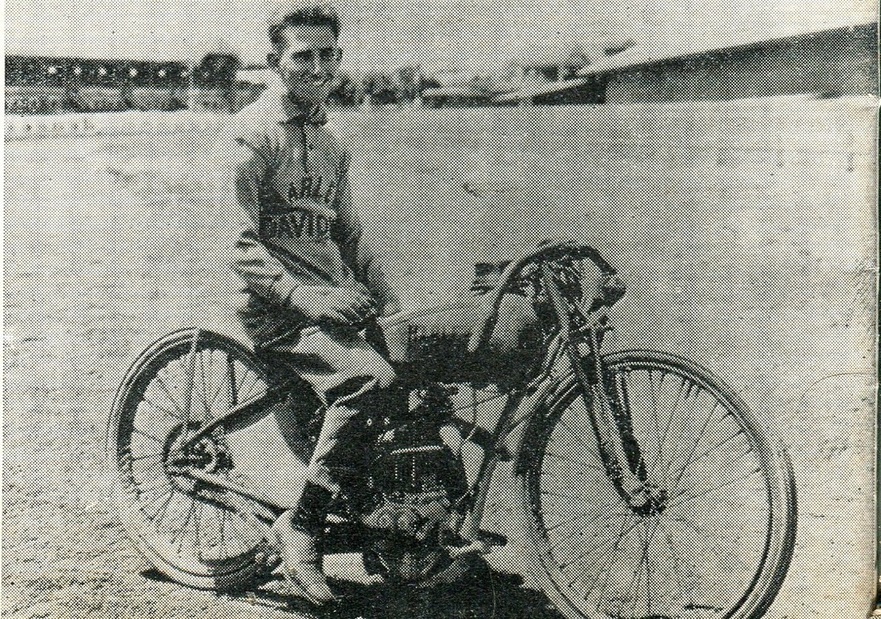

The 600 photographs are luscious and beautifully reproduced, and lots of surprises turn up, such as this 'Harley' Board Track racer which uses a Cyclone engine with one cylinder blanked off! The photographs are gorgeous, and Tanaka has chosen mostly never-seen shots from the Archives. Tanaka knows his vintage motorcycle gear history, and has the eye of a designer laying out the book. The copious images are clearly the point of the book, and the text is minimal - there are times when a bit more exposition would be welcome, but in truth I imagine that few people have a total grasp over the enormity of the Archive and all the details represented. The first edition print run was 10,000 copies - huge by motorcycle book standards, but with H-D attached to the project, I imagine this book will require further print runs.

Purchase Rin Tanaka's outstanding Harley-Davidson Book of Fashions 1910s-1950s here!

Road Test: 2010 Falcon Kestrel

The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world's rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

Sometimes a scoop is a whispered favor; sometimes you grab it with both hands and run. I had the great luxury of spending a weekend in the company of the Falcon Motorcycles team; the Bullet, the Kestrel, Ian and Amaryllis, a talented trio of fabricators from Falcon, and Leif who built up the engine, at the Quail Lodge for the Motorcycle Gathering. I've had the rare opportunity not only of having (well, hijacking) the first real ride on the Kestrel, but of watching the entire process of its development from a sketch through 'wouldn't these parts look cool if I mated them this way' to firing up the bike and easing the clutch home.

When I first saw the Bullet while judging at the 2008 Legends, I thought it was a well-executed Custom, worthy of praise, and thus tolerable to a Vintagent who had little interest in the genre per se, but certainly an appreciation of good workmanship and passion. The Kestrel is different. Ian Barry has shown there is Vintage blood running in his veins, plus something else, but I'll let history name that. Mark my words, it will. I'll stake a claim here and now that the Kestrel has broken out of the Custom shell, and has become something completely new. This man and his team made a Motorcycle the world will have to reckon with.

So I spent more time with the Kestrel, and each time I looked I found something new. A funny little gearbox adjuster, with positive stops and a brace to prevent any axial play. An internal throttle which exits through the end of the clip-on handlebar, with a knurled cable adjuster fixed unobtrusively in place. The little locking levers on top of the TT carbs, which adjust the idle speed. The brackets which hold the two pannier tanks together, which are...turnbuckles... and adjustable to be sure the tanks will fit together just so. An articulated shifter mechanism which mimics the fine bones of the inner ear. And gradually, I was awe-struck.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=m7OIpIJcjpA

The Kestrel isn't a first-look or a ten-foot motorcycle, it's a third look machine, or a fifth. Like a work of fine art, it needs to be lived with to soak it in. It rewards time with time, those thousands of hours spent on its creation slowly leak back out, if you let them. It's a monumental achievement, and among the most beautiful two-wheelers ever made.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=HbWuxy8K4q8

Does it work? Or like Mona Lisa, is it a lovely work of Art? I had reconnoitered the field access a bit earlier by riding my late-entry (ie, no entry, and at noon) '28 Sunbeam TT90 from the street onto the lawn, and thank you Courtney Porras for telling Quail security that I could 'do whatever I want'. Give a man an inch! Thus I knew it was perfectly possible to ride the bike straight from the grass to the road, and nobody would stop me. Up the grassy slope - road clear - and off I went, first right, to all smiles from the hundreds of motorcyclists parked up along the street, and back again to the left, where the highway beckoned.

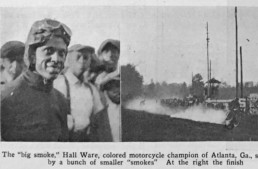

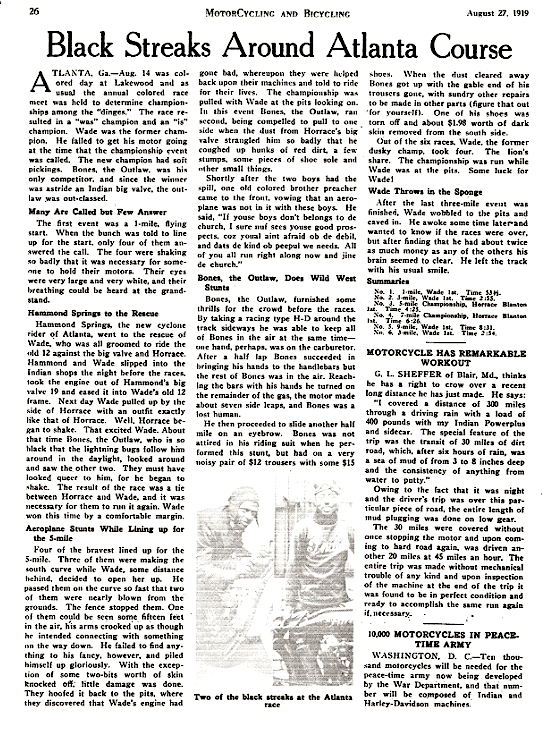

Atlanta's 'Black Streaks'

[Words: David Morrill]

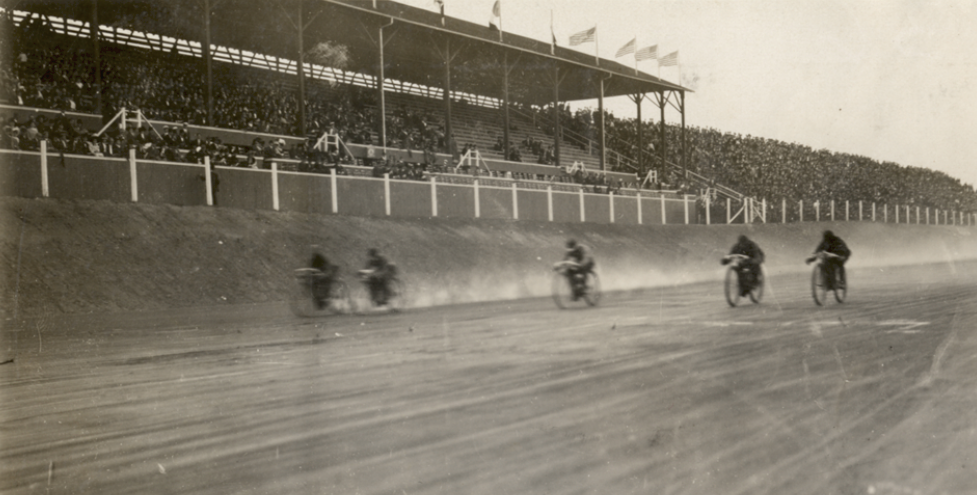

Beginning in the mid-Teens, factory racing teams from Indian, Harley-Davidson, and Excelsior fought a hard battle for dominance on the board- and dirt-tracks around the country. Great riders like Gene Walker, Shrimp Burns, Otto Walker, and many others made their names riding for either the Indian 'Wigwam' or the Harley 'Wrecking Crew'. The bikes they rode were little more than bicycles, with powerful V twin engines, and no brakes. Motorcycle racing was a major spectator sport and drew tens of thousands of spectators across the country.

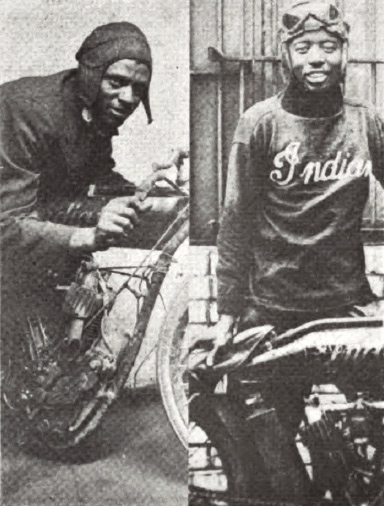

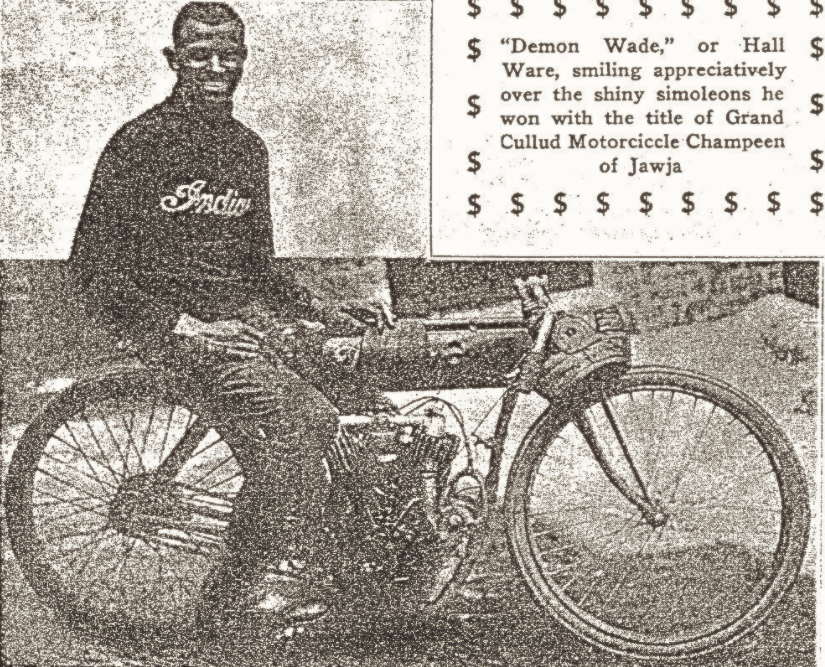

with their Indian Racers - Atlanta 1924

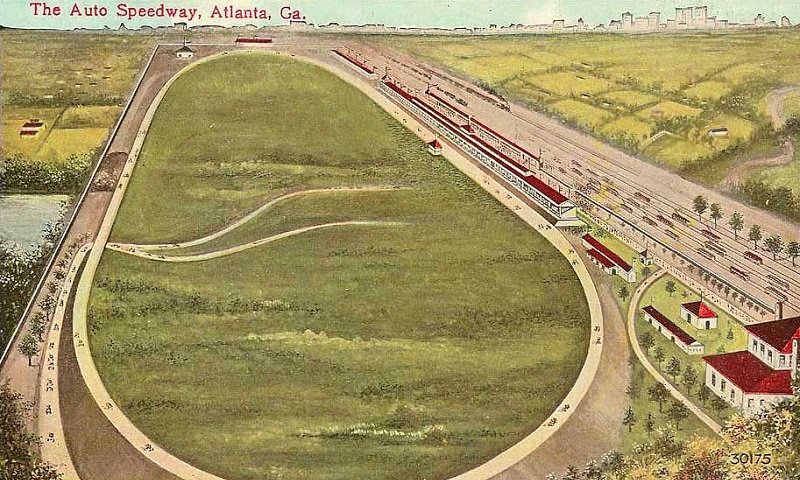

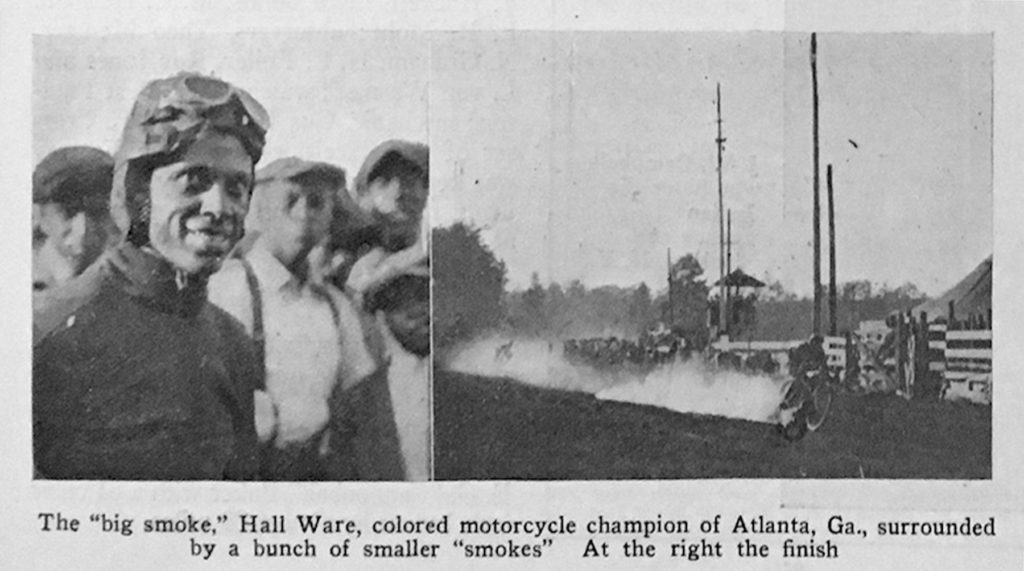

In Atlanta, another group of racers sought fame and fortune, whose story today is virtually unknown; these black riders had colorful nicknames like Hall “Demon Wade” Ware, Horace “Midnight” Blanton, and “Bones the Outlaw,” who raced each other at Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway from 1913 to 1924. They didn't have the latest factory racing bikes, and their racers were often cobbled together with obsolete parts from the scrap piles of local Harley and Indian dealers. They were known as Atlanta’s 'Black Streaks' and while their races were covered by the national motorcycle press, the articles reflected the racial prejudice of the day, such as a 1919 Motorcycling and Bicycling article titled “When Dinge Met Dinge in Georgia"; the text was even worse.

In 1909, Coca Cola founder Asa Candler opened the Atlanta Speedway on what is now the site of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The two-mile oval track featured an asphalt and gravel racing surface, which was modeled after the recently opened Indianapolis Speedway. Motorcycle races (for white riders) were held there beginning in November 1909. The first mention of a motorcycle race for black riders appeared in an Atlanta Constitution article concerning events held at the Speedway on Labor Day, 1913, by the " Atlanta Colored Labor Day Association." The race featured a black automobile racer, "Hard Luck" Bill Jones, who had recently switched to racing motorcycles. The race results appeared in a later Constitution article on Jones; John Sims on an Indian was the winner.

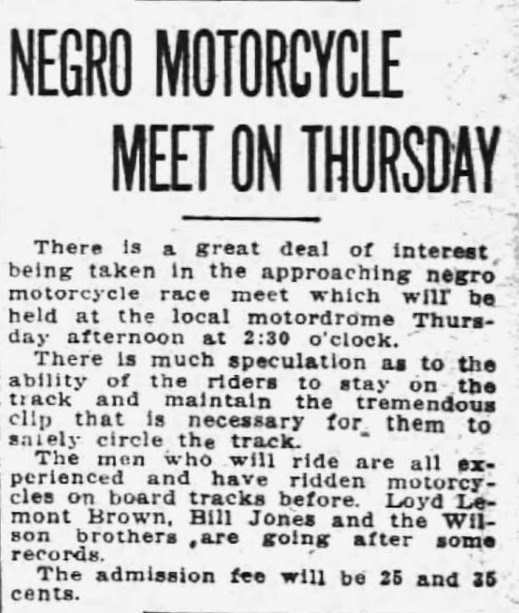

The article quoted local Atlanta Harley-Davidson dealer Gus Castle, and Thor/Jefferson dealer Johnny Aiken. Both dealers' statements reflected the attitude of most whites in Jim Crow Atlanta. Gus Castle stated: "I think the negro racing game is a substantial benefit, as it drives the last nail in the coffin of motorcycle track racing in Atlanta, and that's a blessing of no small importance." Aiken's stated: "Except that it will popularize motorcycling among Negros and in that way cheapen the sport in the eyes of white men." The article went on to state that there were about forty black motorcyclists in Atlanta, and that the white dealers refused to sell them new motorcycles. After reading the article in Motorcycling, Federation of American Motorcyclists (F.A.M.) Chairman John L. Donovan wired the track operators stating the Atlanta Motordrome would be "outlawed" and their race sanctions withdrawn "as the F.A.M. does not allow colored men as members." Despite the threats from Donovan, on October 19, 1913, an article appeared in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper announcing a race featuring black riders would take place at the Motordrome.

The article states "The men who ride are all experienced and have ridden motorcycles on board tracks before" (that statement seems to confirm that black riders rode on Motordrome-style board tracks in other cities, but sadly, that history has been lost). The Atlanta race was postponed twice due to rain. Weather was a constant problem at the Atlanta Motordrome - the riders could not safely race on the steep wooden banking when it was wet, and races were often postponed several times. The race featuring black riders took place at the Motordrome on afternoon of October 28, 1913, and featured black riders Bill Jones, and Lloyd Brown of Atlanta, along with the Wilson brothers from New Orleans, and Ben Griggs and Willie McCabe of Chattanooga. The Atlanta Constitution did not cover the race, and the results are unknown. Less than a month after the race, an article appeared in Motorcycling World and Bicycling Review that stated the owners of the Motordrome had filed for bankruptcy. It further stated: “This Motordrome earned an unsavory reputation by pulling off a race with negro riders, in defiance of F.A.M. regulations, thereby becoming outlawed as long as the present management exists.” The Motordrome reopened the following year under new management. There is no record of any further races featuring black riders at the track. With the opening of the Lakewood Speedway, motorcycle racing shifted away from the Motordrome.

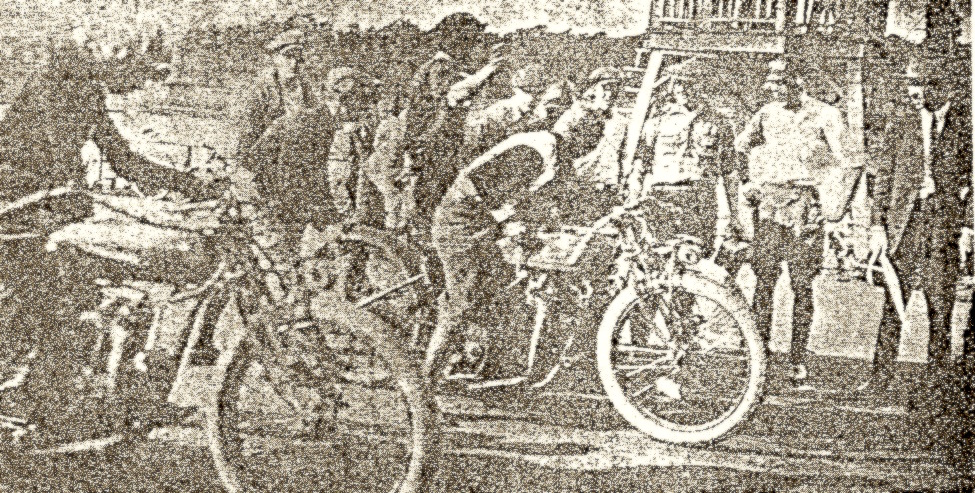

The Lakewood Speedway, one-mile dirt oval, opened south of the city in 1917, and immediately began running motorcycle and auto races. The track owners revived the racing series for black riders, which they billed as the Grand Colored Motorcycle Championship Race. A black South Carolina racer named Tom Reese, who called himself the 'Champion of South Carolina', arrived in Atlanta for the June race. Reese’s manager began to brag that Reese could 'beat any Atlanta rider,' and he was prepared to place a large cash wager to back up his claim. The event drew large crowds from Atlanta’s black community, and bets were placed on the favorite riders. While the Harley-Davidson, Indian, and Excelsior factories had no involvement in these races, the local Harley-Davidson and Indian dealers gave limited assistance to their chosen racers. They also often placed large wagers between themselves on the outcome of the race.

On May 31, 1919, 'Bones the Outlaw' appeared in a photograph (was standing with his employer Harry Glenn) within a pre-race article for the 1919 Southern Dirt Track Championship, which featured top white riders from around the south, including Birmingham's Gene Walker , and Atlanta's Nemo Lancaster. At the local Indian dealer, Hall 'Demon Wade' Ware saw an opportunity; already an accomplished local racer, Ware worked for the dealer as a mechanic. He convinced his boss, Nemo Lancaster, to lend him a competitive bike to race against Tom Reese. While Lancaster recognized Ware’s talent, the rumor was he had a very large side bet with Reese’s manager. At the start of the race, Reese on a Harley-Davidson jumped out to an early lead, and Reese’s manager expected to win the wager. Ware, on the loaned Indian, soon caught the Carolina Champion and passed him, winning the race. Ware claimed the $150 first prize, and Lancaster collected on large side bet with Reese’s manager.

The race in August 1919 was another hard-fought battle between 'Demon Wade' and 'Bones the Outlaw'. 'Midnight' Blanton won several of the preliminary races, and had a shot at winning the championship race. But the night before the race, Atlanta board track racer Hammond Springs (who was white) helped Wade install Springs' new Indian racing engine into Wade’s older Indian frame. The competitive engine allowed Wade the edge he needed to leave Blanton in his dust. On the final lap, he and Bones the Outlaw, crossed the line in a tie. This required a rematch, which Wade won hands down, claiming the 1919 championship.

The race held on June 5, 1922, proved to be a bit of a disappointment. Once again several racers from around the South arrived, prepared to race. When Hall Wade's bike was unloaded, the motor was covered. This gave rise to rumors that Wade had another special racing engine, which was a reasonable supposition, as Wade was close to his former employer, Harry Glenn - by then an Indian factory representative. When race time rolled around, only Horace Blanton came to the starting line to face Wade. Wade won two five-mile races, defending the Southern Champion title he'd held since 1915. The remainder of the the day's races were canceled due to the lack of competition. By the 1924 race, 'Bones the Outlaw' had switched to racing automobiles, and 'Demon Ware' had sold his machine and moved north. For the 1924 races, 'Bones the Outlaw' made a demonstration run in his racing car, blasting around the dirt oval and putting on quite a show, narrowly avoiding a crash several times. In the motorcycle race, Horace Blanton had no real competition, his two chief rivals having moved on, and he easily claimed the Championship over a field of less experienced riders.

A Cowboy at a Garden Party

[Words and Photos: Michael Lawless]

"Welcome to Radnor Hunt Concours d'Elegance, gentlemen." The guards pointed our van up the manicured gravel drive; we drove past the stately clubhouse, and down the hill by the stables. As we rounded a bend we were greeted with a chorus of barking. "Look, doggies!" "They're not doggies Bryan; they're hounds." Radnor Hunt, the 'since 1882' Fox hunting club in a wealthy Philadelphia suburb, is a long way from the world of flat-track.

My mission for the Radnor Hunt Concours is to procure the extraordinary; that's how I landed the job as National Champion Bryan Smith's handler. I'd asked to borrow Ricky Howerton's 2016 flat-track Championship winning Howerton Racing Kawasaki, and he not only said yes, but graciously offered to send the winning rider, Bryan Smith, along with the bike. Getting the bike was terrific, but having the Champ was the icing on the cake.

The Kawasaki is called "The Skinny Bike", and its a stunningly modern interpretation of a flat-track racing motorcycle, a study in minimalism and clever reduction. Motorcycle magazines around the world fawned over this bike, and legendary motorcycle designer Miguel Galluzzi said "The Kawa is what a pure motorcycle should be," high praise from the man who invented the Ducati Monster. I was surprised no other Concours had ask to display "The Skinny Bike."

My deal was to pick up the Skinny Bike immediately after the Williams Grove flat-track race on Saturday, and bring it to Radnor Hunt for Sunday's Concours. Bryan needed to do well in that race to retain his championship, and his riding was 'all in'; he was a contender until he pitched it away in turn three. With Smith out, the championship belonged to Jared Mees. Bryan was fine after his spill, but it's hard to watch a friend do the 'walk of shame' back to the pits, on national TV.

We loaded the Skinny Bike in the van and started heading east, stopping for a quick dinner on the road. No tables were available, so we sat at the bar - it was a hard luck day. Bryan ordered a Moscow Mule (the name says it all); more appeared in short order, courtesy of his fans, whom I think were a little shocked to see him humbly sitting at the bar. Well-wishers stopped for a selfie or an autograph, and he made time for everyone. Flat-track racing is more than a job for Bryan, it's his life.

As we ate dinner, I reflected how easy it was to load the "Skinny Bike" into the van. Switching to the bigger Indian flat-track racer must have been quite a change, but when asked, he just shrugged it off, admitting that the Indian was more like a Harley-Davidson XR750, as Brad Baker & Jared Mees raced last season. It's the mark of a professional that Smith hopped on the heavy Indian and was up to speed immediately...but Bryan did mention he really liked riding the Howerton Kawasaki. Perhaps he'll will race one again?

Offloading the Skinny Bike, we wheeled it past the big white tents spilling over with Rolls Royces, Ferraris and McLarens. Well-dressed ladies in big hats regarded us curiously, and Bryan understood why I'd forwarded the email on 'proper attire for a gentleman'. We strolled the show field after a quick breakfast in the clubhouse, and Bryan was impressed with the uniqueness of every car and bike on display, which included his own. "I've never even seen these on Google before!" Then the red-coated Huntsman's horn blared as he galloped past with his pack of hounds - the ceremonial start of the Concours. The contrast in atmosphere between Radnor Hunt and the Williams Grove flat-track couldn't be greater. Bryan rubbed elbows with the well-heeled Radnor guests, and was surprised to discover they were well-informed regarding flat-track racing, and knew about his Championship, but were more impressed with his X-Games win! That's when Bryan Smith relaxed, and the day became a positive experience for the Champ. I think Radnor Hunt has not seen the last of the flat-track scene!

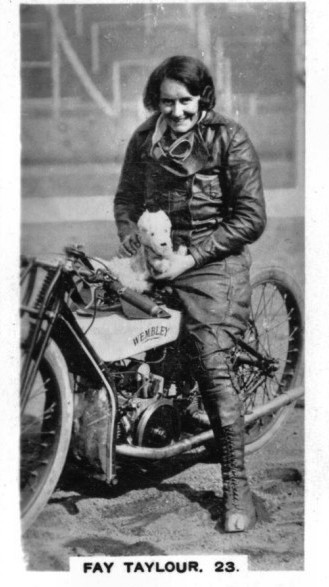

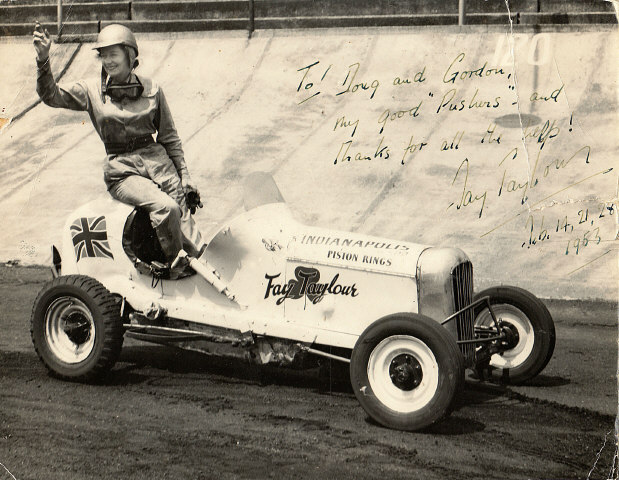

From Glorious to Notorious; the Fay Taylour Story

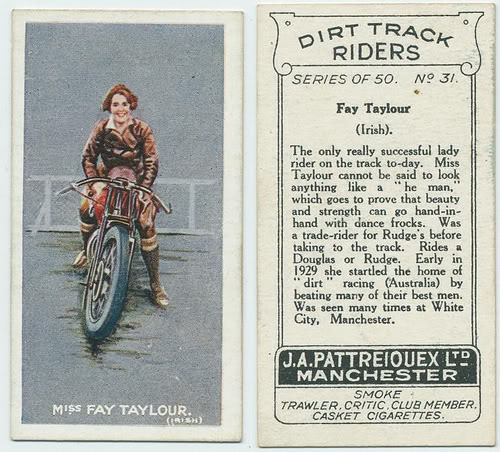

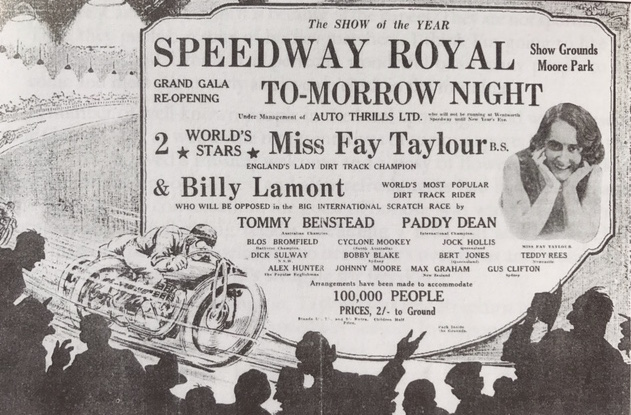

While virtually forgotten today, Fay Taylour was among the most world's most famous motorcyclists in the 1920's, and the most successful female motorsports competitor of the 20th Century. She was a champion speedway rider in the earliest days of the sport, when races drew crowds of 30,000 people. She was a consistent winner on the dirt tracks, and not in 'ladies events' - she held the outright lap record at several speedway circuits in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, which so threatened the men behind the sport they banned all women from speedway tracks by 1930! She then took up auto racing, with less success, but still won many races between 1930-54. Until sexism quashed her ambitions, she was widely respected, interviewed, filmed, photographed, and featured on race programs as a star, wherever she went.