In one of the first photos I saw of Anne-France Dautheville, she posed for the camera astride a Kawasaki 125, sporting a floral dress and black kitten heels. In the distance, the lilac-tinted thunderclouds behind her look daunting, but Dautheville’s insistent stare reads unfazed by the approaching storm. After all, she was prepared. Punctuating her rig were jerry-cans holding extra oil and her cargo consisted of two plastic bags strapped to the handlebars, which also kept her hands warm while she rode–an imperative trick she learned after starting her epic journey.ADV:Overland celebrates the spirit of adventure and exploration. Our Petersen Museum exhibit runs from July 2021 – April 2022. These are the stories behind the vehicles in the exhibit, and others we need to tell because they are amazing, like this story of the first woman to ride solo around the world, Anne-France Dautheville, by Arabella Anderson.

The photo was taken in the former Republic of Yugoslavia while she was embarking on a trip around the world, traversing three continents and over 12,500 miles in the year of 1973 when she was 29 years old. “A girl on two wheels didn’t exist very much (then),” Dautheville recalled when we spoke.

Dautheville, now 77 years old, is sprightly and full of humor, usually ending her recounts on the road with a joyful laugh, still entertained by the experience decades later. She exudes the spirit of someone who has lived a robust life, imbuing a sense of adventure and excitement as she recalls visiting sacred monuments as if it was as simple as running a quotidian errand.

As a fellow female motorcycle rider, I was instantly dazzled by the mythos of Dautheville–a veritable trailblazer, who was saturated with the courage to travel to countries she had never visited and where she didn’t speak the language. What could have possibly inspired a young woman, who describes her upbringing in France as very traditional and “do as you’re told,” to undertake such an arduous journey all by herself? It wasn’t simply for the optics–this was a time when social media was a tangible photo album you kept at home; there were no hashtags, there was no brand sponsoring or humble-brag posts to prove you were, indeed, a wild child. Dautheville wanted to simply defy the norm, to prove she was strong, and to experience the world.

Dautheville’s journey into the world of motorcycles began in May 1968, which was a perilous time of civil unrest in France. Paris was under siege by wildcat student demonstrators, protesting against capitalism and American imperialism, bolstered by sympathetic strikers. Street battles between protesters and police created a vulnerable environment for the working pedestrians, lasting for weeks. This is when Dautheville first became interested in riding motorcycles. During that era, motorcycles were not considered a good image, “it was for hooligans” as Dautheville recalls. Think of the quintessential, leather-clad outlaws in Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels. Unconcerned with image, Dautheville began riding motorcycles from a place of utility–needing to commute to work (she worked in advertising as a creative copywriter,) from her flat in Paris.

She rode a little Honda 50cc moped, having neither a license to operate a car or a motorcycle, but cherished the feeling of freedom, being able to always move. After riding the moped to see the Mediterranean one holiday, Dautheville humorously recalled asking herself, “How much do I pay my money?” and realized she was unhappy at her job, writing copy for American laundry detergent companies. She quit, upgraded from a moped to a 750 Moto Guzzi that a French importer lent to her, and decided to follow a motorcycle rally called the Orion Raid from Paris to Isfahan, Iran in 1972.

There were 105 bikers in the rally, and Dautheville was the only woman rider; the other women in the cavalcade were passengers, riding on the backs of motorcycles. Publications interviewed Dautheville, fascinated by the spectacle of a woman on a motorcycle while also, on the side, making a morbid bet she would crash before 500km into the trip. Dautheville did eventually take a spill during the trip, going straight into a sharp curve and hitting a stone milepost on the side of the road, but this was 750km in, on the Mont Cenis pass between France and Italy. Twisting the front forks of the Moto Guzzi, Dautheville rode in the rally’s assistance truck with the bike to Belgrade, where the bike was fixed. Dautheville soon got back on the road and rejoined the rally, never turning back. Of the 105 motorcyclists that left Paris, 92 reached Iran. 11 carried on to Afghanistan. 5 then to Pakistan. And Dautheville was there for all of it.

When Dautheville returned home, she holed up in her parents home in the French countryside and wrote her first book about her experience during the Orion Raid. When she returned to Paris, she learned that rumors had spread that she was a ‘hoax,’ that she rode in the back of the assistance truck with her motorcycle the whole time, and pretty much just about “anything bad you could say about a girl…” was said, Dautheville recalled. It was clear that the world was not yet ready for a woman like Dautheville, but that would not stop her. In fact, it fueled her. Furious, Dautheville decided to defy the erroneous rumors by doing something ambitious, something that had never been done before: a solo world-tour on a motorcycle; a journey that would be irrefutable by the gossips back home.

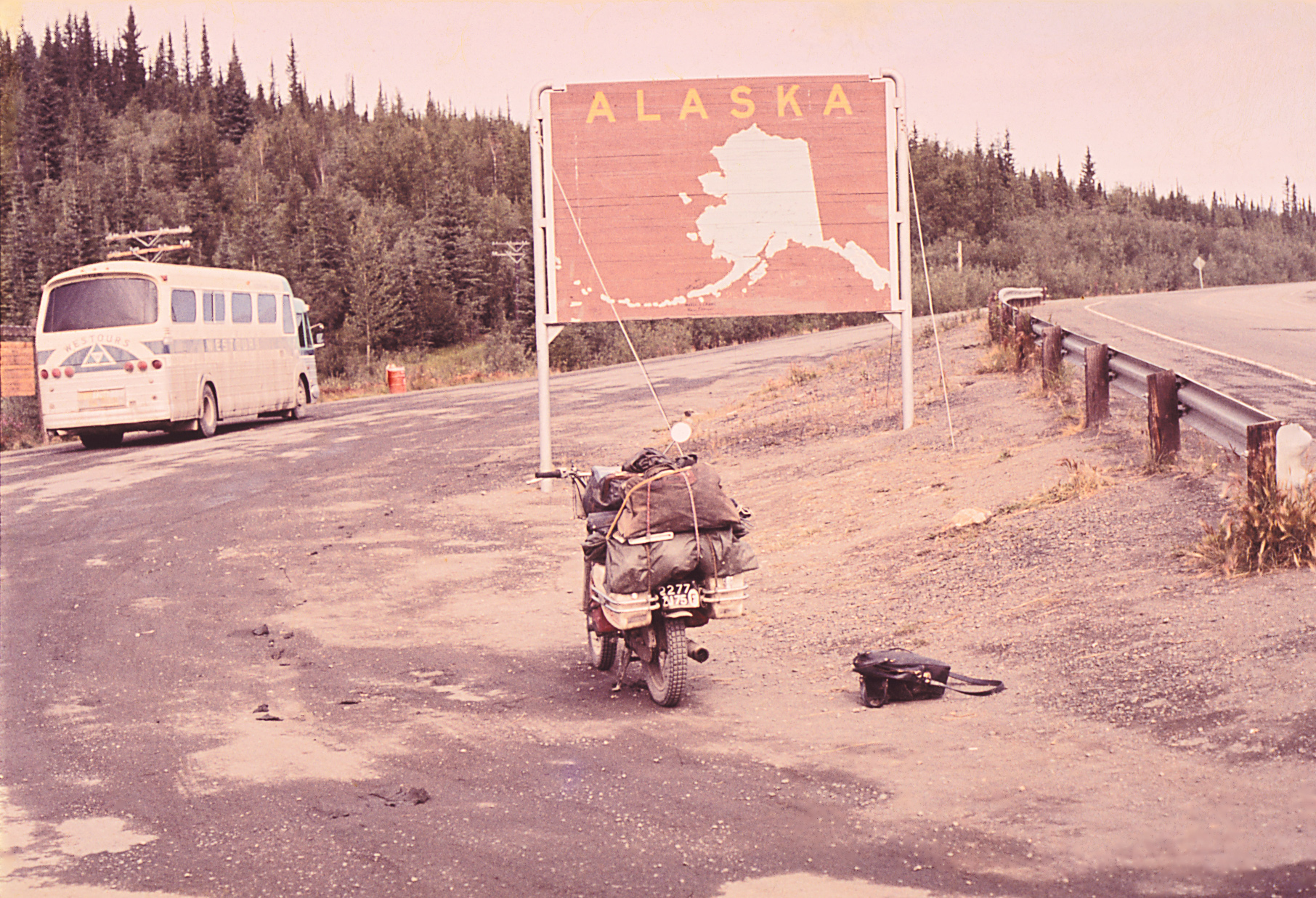

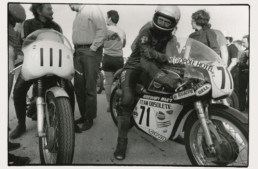

The journey began in July 1973 in Montreal on a 125cc Kawasaki 125, a bike she had borrowed from an importer. She chose to borrow a bike instead of being paid to sponsor so she could truly be “free” on her journey, supporting herself by writing articles along the way for magazines such as Moto Revue. Plus, borrowing a bike meant repairs at dealerships along the way at no cost. Dautheville started this ambitious trip in Montreal, explaining it was somewhat of a trial run for her overall journey. Montreal to Anchorage is quite a distance; a vast 6437 kilometers (4000 miles) of, at the time, mostly gravel roads.

Not long into her trip, Dautheville was struck by a fishtailing trailer being towed by a truck. Dautheville recalled the world spinning around her as she and the bike tumbled into a ditch. She suffered no major injuries, but after being bandaged up by the doctor, Dautheville sincerely asked him if she could have a glass of whiskey–a panacea for the resilient. Once the bike was fixed, Dautheville hit the road, camping her way across Canada, arriving in Alaska about a month later.

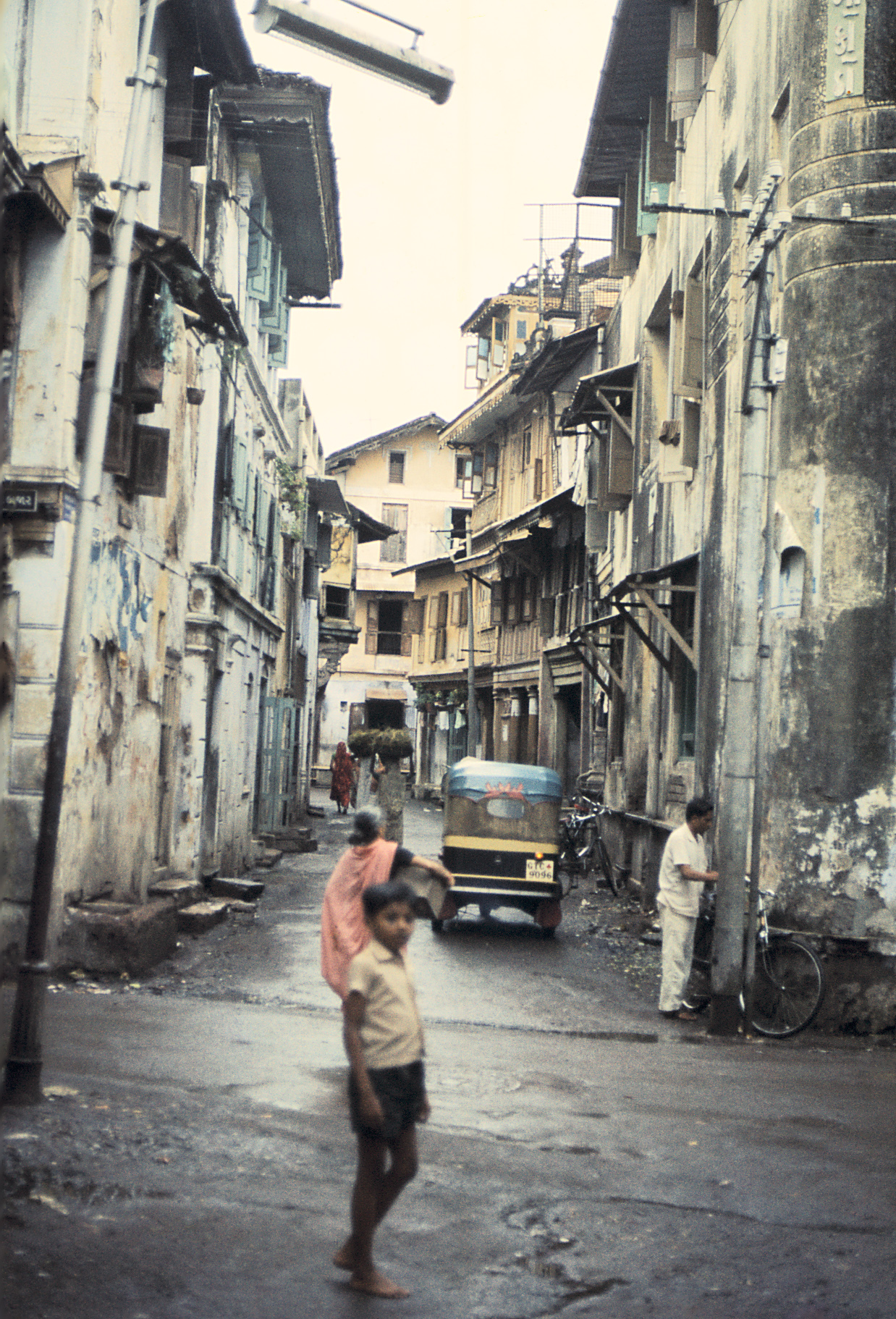

From Anchorage, Dautheville and her Kawasaki boarded a flight to Tokyo and spent three weeks exploring Japan. After a local Kawasaki in Tokyo dealer remounted the engine in her bike to make it sturdier for the rest of her trip, Dautheville continued her journey to India. Though soon after arriving, on her way to Bombay, her bike broke down in Surat (as a result of wrong parts being used for the remounting of the engine in Japan) and Dautheville resorted to taking a train with her bike to New Delhi, stranded there for two weeks while the French Embassy ordered her the proper parts. Dautheville, quite the optimist, laughed as she told me that her downtime in New Delhi just felt like a holiday, allowing her to have some time to sunbathe at the Hilton swimming pool and explore the city, taking photos of all the friendly people she met along the way. “Every day was Christmas Day,” she told me, her voice tinged with nostalgia.

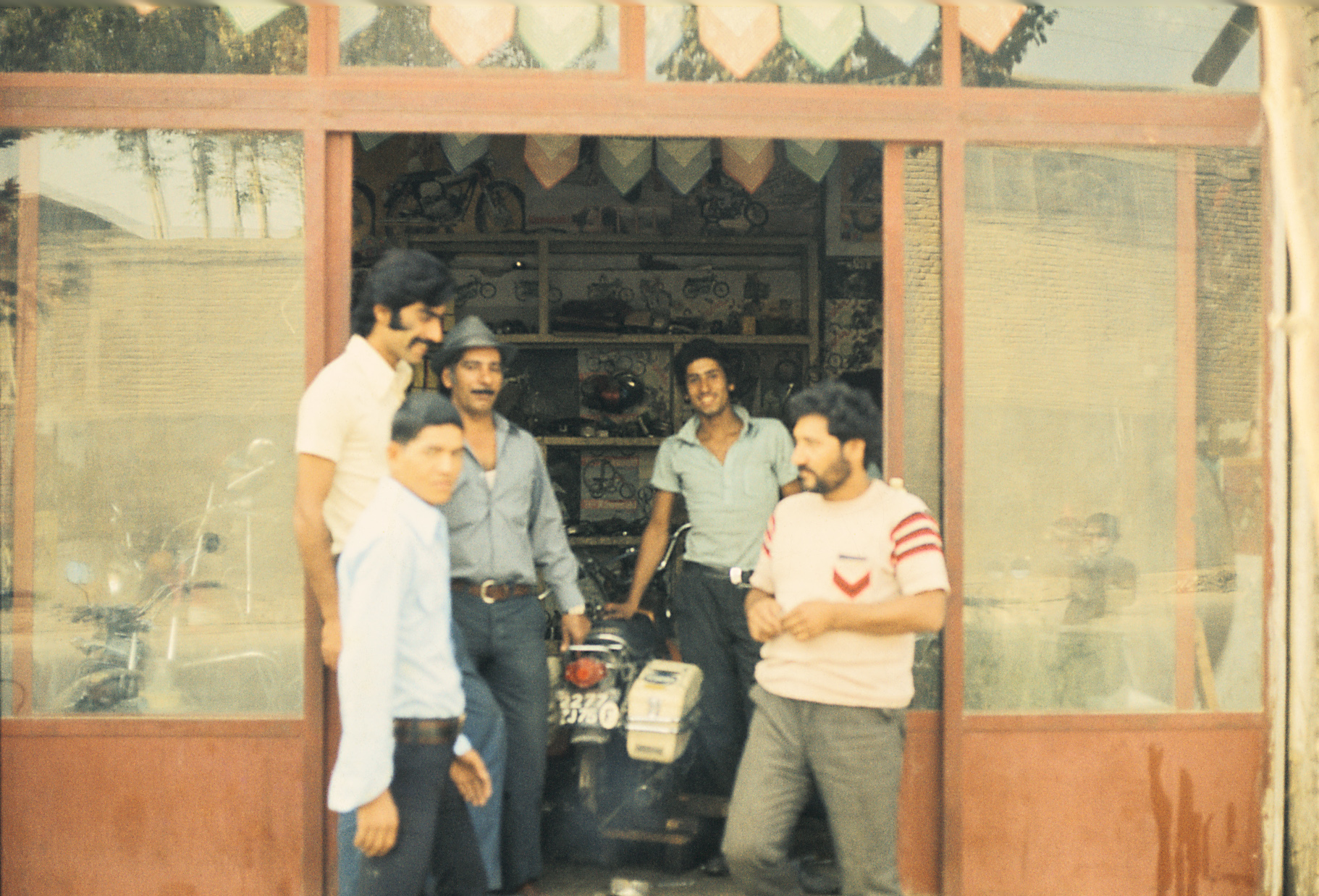

Once her bike was repaired, she traveled to see the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and then carried on to Pakistan. Dautheville recalled how funny it was that people were so excited to see a woman on a motorcycle, cheering at her as she rode past: “I was color TV and everyone wanted to see me.” In Pakistan, Dautheville went to a restaurant for a meal (eating a lot of food on a trip like this is crucial, Dautheville explained, “When you go on a long trip like that, you have to take care of the engine, and your body.”) When she asked for the bill, she was surprised to learn that a complete stranger had paid for her meal, something that happened a few times during her trip. She suspected it was because, “A woman traveling alone (was) absolutely sacred.” Evoking a sense of sanctity meant respect. “I never felt scared or unsafe.”

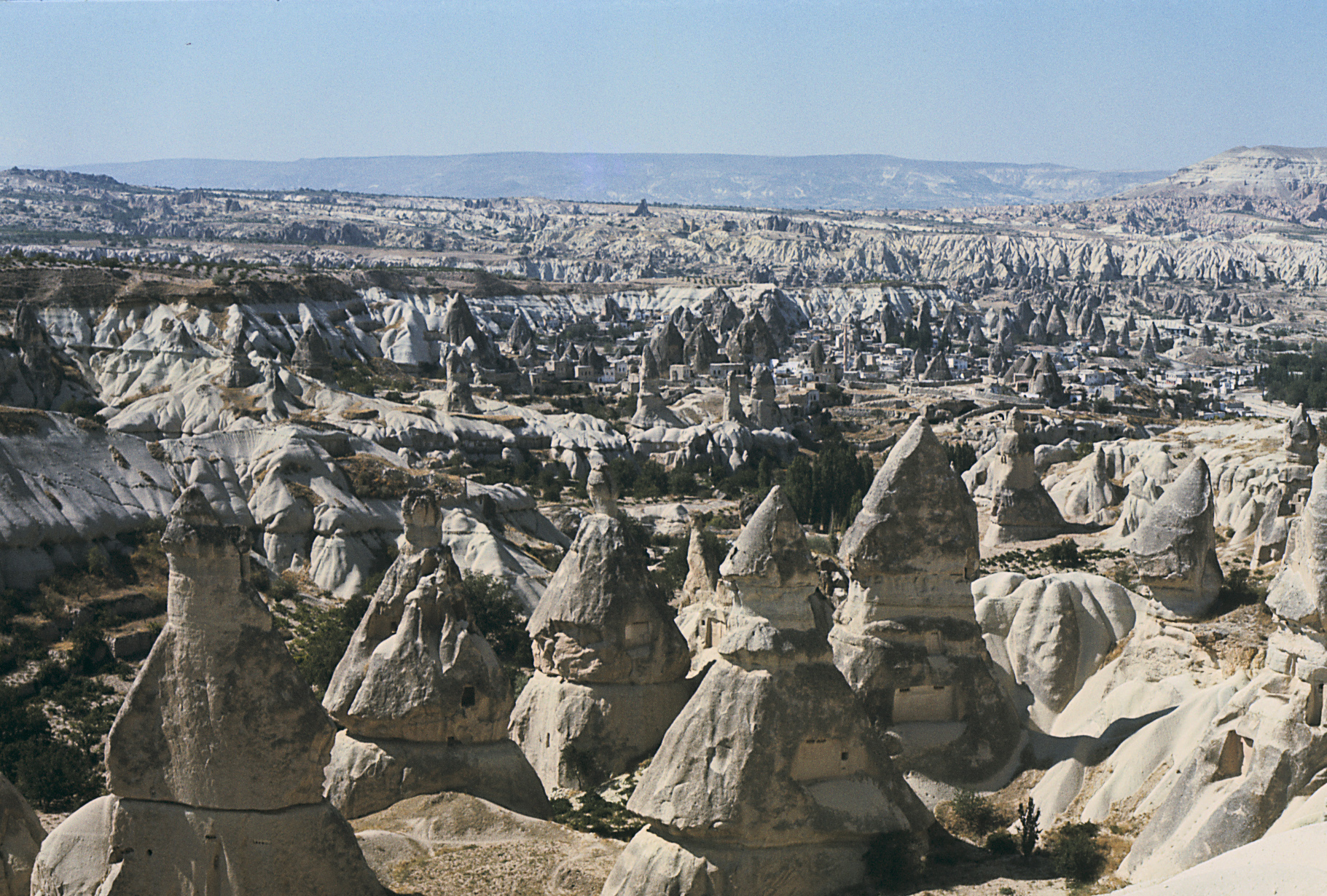

After Pakistan, Dautheville made her way to Afghanistan, which she declared is her favorite country. “The landscapes are so powerful and pristine,” Dautheville remembered, saying that it felt like you were “on the moon,” and constantly mesmerized, describing the Valley of Buddhas in Hazarajat as a “perfect place.” She described how kind and welcoming the Afghan people were because they were proud of themselves, “They were welcoming you because they were the kings of their own country.” Hearing this passionate remembrance of Afghanistan was so powerful and heartbreaking, as Dautheville’s time there was only five years before the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan staged a coup d’état and usurped then-president Mohammed Daoud Khan, only to then later be ravaged by the Soviet-Afghan war, and then, eventually, the U.S. war in Afghanistan. “They have been crushed by betrayal of the whole world for thirty years.” Dautheville lamented.

While waiting to cross the border from Afghanistan into Iran, a man beckoned Dautheville over to his car. As Dautheville approached, she saw a woman wearing a chadree in the passenger seat holding her infant. The father passed the baby to Dautheville to hold. “I think it was a way to honor me with holding what was most precious in his life.” Dautheville was seen as a good omen; a woman on a motorcycle, exuding freedom in a foreign country where she did not speak the language, garnered absolute admiration.

Years later, while waiting on a subway platform back in Paris, Dautheville overheard two young men talking in a language she did not know, but could recognize. They were Afghani. Dautheville, a confident conversationalist, pulled out her iPad and showed the two young men some photos from her trip to Afghanistan, a version of their homeland that they never got to know, that is no longer there. “We were not from the same world, but there was something very strong, like a recognition. A communication through the roots not of the culture, but of humanity. A communication through the roots of life.”

After crossing over to Iran, Dautheville rode to Turkey, then to Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Austria, Germany and back home to Paris, concluding her trip towards the end of November 1973. She returned to her normal life and started writing her second book, Et J’ai Suivi le Vent (And I Followed the Wind), about her record-setting worldwide trip. “No one could destroy me anymore. I was too strong.” Dautheville said, referring to her past travels being tarnished by lies started by ornery gossips back home. When I asked Dautheville what she learned from this experience, she replied, “This trip had taught me two things: I am built to travel alone, and I must have a bike I can pick up by myself.” Everything else she experienced, saw, and felt, was just a part of the journey. “It was a state of fascination all the time. I was in front of blue rabbits all the time.”

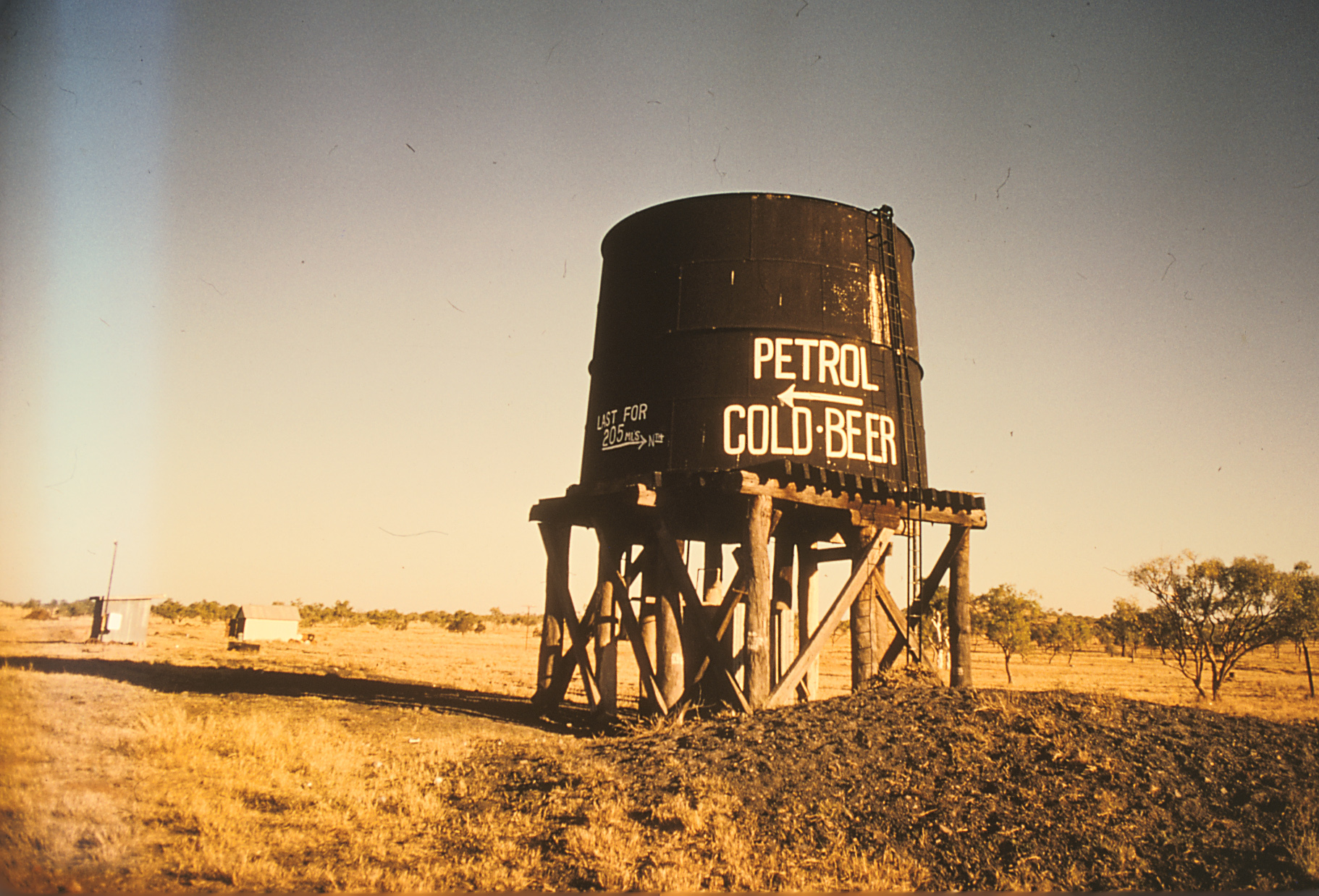

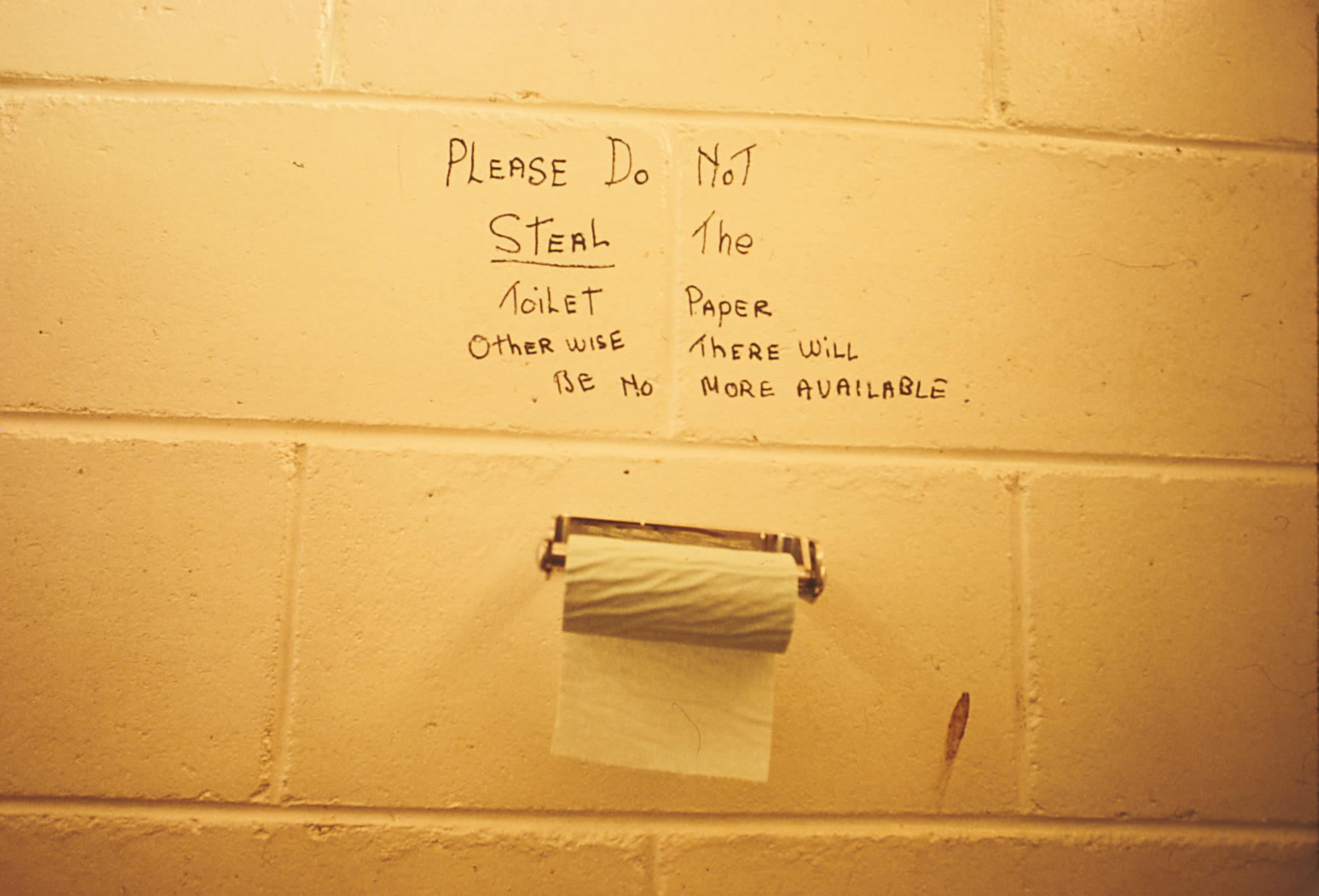

The road would call Dautheville’s name for decades, as she continued traveling the world, doing long, solo trips through South America and across Australia, writing about her experiences for Moto Revue and Match Magazine, penning numerous books, doing a Ted Talk, and even becoming a muse for the fashion brand Chloe in 2016. After a car accident in 2012, Dautheville retired from motorcycle riding, but Dautheville doesn’t want that to take away from the many journeys she embarked on: “I’ve had a very good life. At my age, you look back at what you had, not what you don’t have anymore.”

Dautheville’s two-wheeled travels show us how important it is to explore outside of the realm in which we inhabit, in order to educate ourselves on how to be present and be ready to embrace adventure every step of the way. When it comes to recommending advice for fellow bikers and aspiring travelers, Dautheville withholds the specifics, instead sharing vital wisdom: “I was not traveling with my brain, I was traveling with my heart.” But a piece of advice I felt to be just as crucial was when I asked Dautheville if anyone in her life tried to stop her from going on these trips. Dautheville, without hesitation, proclaimed, “Nobody tried to stop me, because I am unstoppable!”

Written by: Arabella Anderson

Instagram: @arasmella

Images provided by: Anne-France Dautheville

Managing Editor: @markmacinnis

Really fantastic reading.

Such a great spirit! She’s not a motorcyclist in the way that most of us are, where the bike and the gear and the tools are such a central part of it. The motorcycle was just a tool — though an essential one — that enabled her to go where she wanted to go and do what she wanted to do.