Sweet Savage DNA - A Father’s Day Story

By Catherine O'Connor

Angela Savage wishes she could turn back time. The posthumously born daughter of flat tracker turned Indy driver, David Earl “Swede” Savage, Jr. wore all black to this year’s Indianapolis 500. In the midst of stoked Memorial Day revelers cheering and screaming for their favorite Indy rivals, Angela did her best to cope, sitting in the stands with her 17- and 11-year-old sons. She often wears the Swiss-made Omega Speedmaster watch and her father’s wedding ring as an amulet to feel close to him.

“I kept staring at turn 4, knowing his spirit was there. I cried a lot, and just couldn’t stay for the whole race, just wishing I could have my dad back,” Savage said. Growing up she always felt lost and abandoned and so lonely. And Father’s Day won’t be easy.

Born three months after her mother witnessed her father’s fatal crash, Angela Savage spent decades suffering crippling addiction and mental health challenges. What the younger Savage learned was that she was dealing with inter-utero, psycho-injury, a type of inherited trauma that can be passed down from a pregnant mother to her child. Mourning a bewildering sense of longing for the father she never met, Angela spent years struggling to reconcile the history and meaning of his death and life, painfully detangling herself from the unexplained, trans-generational life stress surrounding her Savage legacy.

But with the help of a group of endearing fans and IMS, (Indianapolis Motor Speedway) she had a chance encounter with Ted Woerner. He is an author and impassioned Indy fan who had heard about his hero, Savage’s crash, on the transistor radio he smuggled into his sixth-grade classroom. Their support enabled Angela to find the courage to finally visit the track which took her father’s life. ”It was like soul surgery,” Angela has said of her visit to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, where the fatal tragedy occurred 50 years ago.

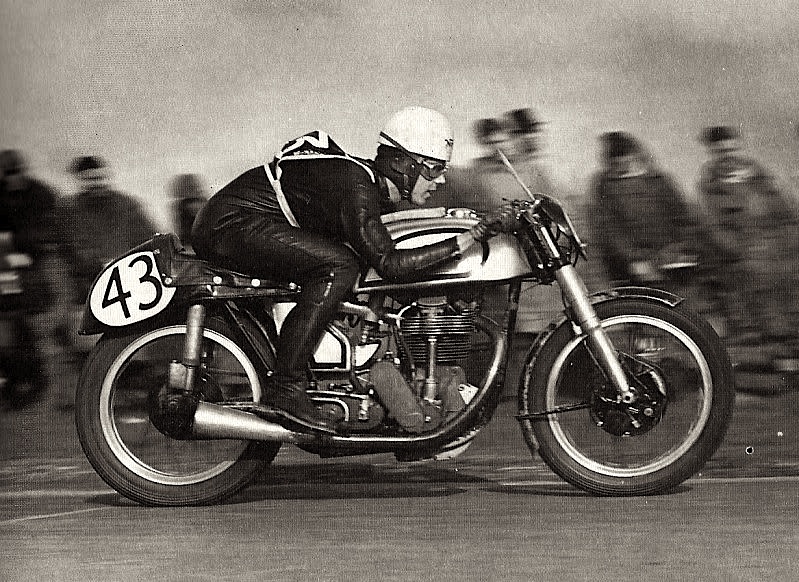

Together they collaborated to write Savage Angel: Death and Rebirth at the Indianapolis 500, a book that skillfully and candidly interweaves details of her life trauma and eventual healing, with revelations of a unique motorsports legacy. Among Savage’s memorabilia are news clips showing that Swede raced as an AMA Amateur in 1965 at the Springfield Mile. Revisiting the motorcycle track where he competed alongside contemporaries, Bart Markel, Dick Mann, Gary Nixon and Eddie Wirth, to watch her first motorcycle race a couple years ago, in Springfield, lifted Angela. “I was blown away at my first flat track race. I just love it!” Angela said.

Her imagination must run to the 18-year-old Swede, the blonde hunk, the son of a prosperous veterinarian, a carefree rebel, traveling the flat track circuit, in the mid 1960’s. From Ascot to Daytona and state fair tracks across the Midwest, in bar-banging combat, Savage competed in AMA’s Expert class finishing among the top 20 riders in the nation, with a total of 24 career AMA wins.

Angela, who now works for Woerner’s Miles Ahead company in Indianapolis, can step into the past in the Savage suite exhibit room that has been created there. Shelves hold her father’s early race artifacts, his tattered leathers, steel shoe and images of the photogenic, beloved native son of San Bernardino. Recognized early for his innate riding performance talent, the original letter Savage signed for a short term deal with Evel Knievel to perform in his Stunt Show of Stars at Ascot Park in 1967, is framed in glass. Pages of emergent race accomplishment, in a “race resume” typed in 1969 by a young David Savage Jr. is but one curated clue in the historic archive Woerner has meticulously pieced together.

A wall of Swede’s 70’s vintage auto racing suits, are a neatly hung team of empty fabric onesies that brave, Indy drivers wore before the evolution to today’s high-tech safety gear. On the wall, charred remains of his race car nose section with Swede’s race number 40, marred and scorched, steels a horribly devastating moment in time.

Woerner and Savage often meet motorsports fans who are intrigued by Savage’s story of evolution from two wheels to four, and the impact of his life ended too soon. The California native, her husband and family relocated in 2018 to live in Indianapolis, the city where Angela’s father died. Angela’s message of healing and survival simply flows out. “I’m proud that the Savage family is still here, 50 years later. I want to tell my story, and his story.”

Buoyant and open to talk, Angela Savage along with documentarian Ted Woerner, who continues researching the life and times of Swede Savage, will be on hand at the Illinois State Fairgrounds Springfield Mile on Sept 2-3. There, auto racing fans’ eyes will pop, when they see Woerner’s freshly painted dayglow red #40 STP Oil Treatment Special Eagle-Offenhauser replica of Swede Savage’s STP race car, a special premiere feature at this year’s Springfield Mile.

Please check out SAVAGE42.com for more info.

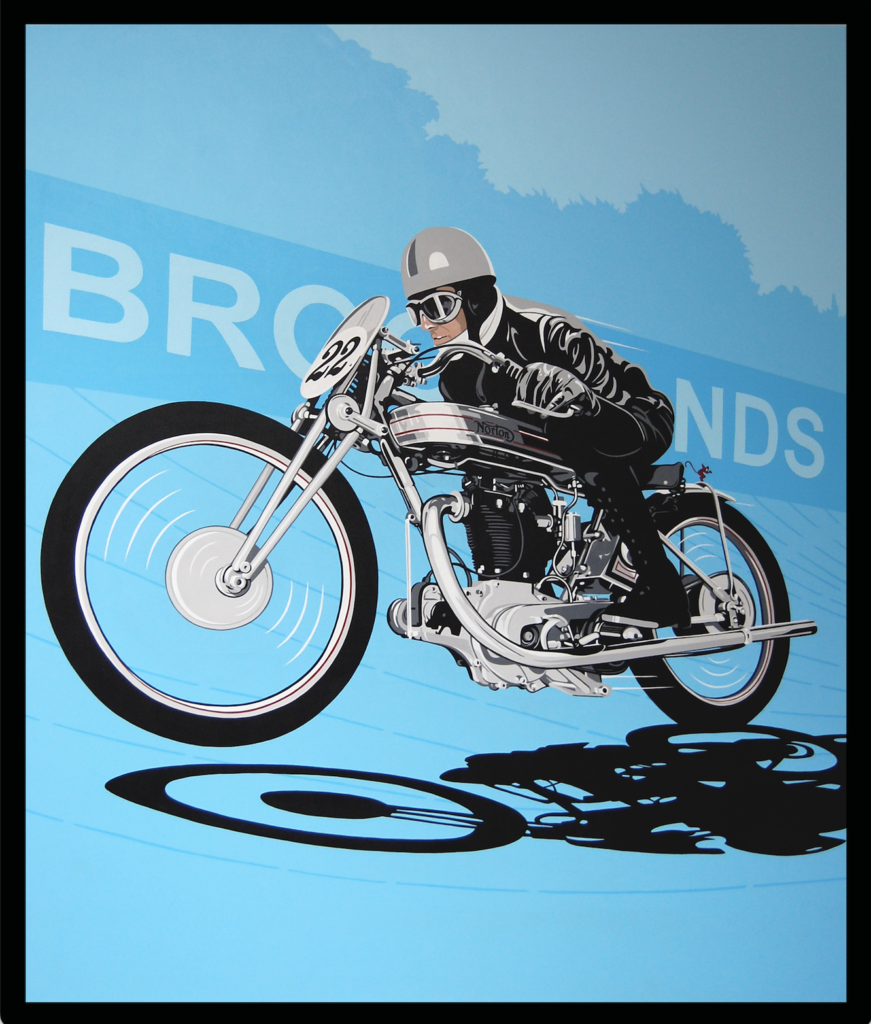

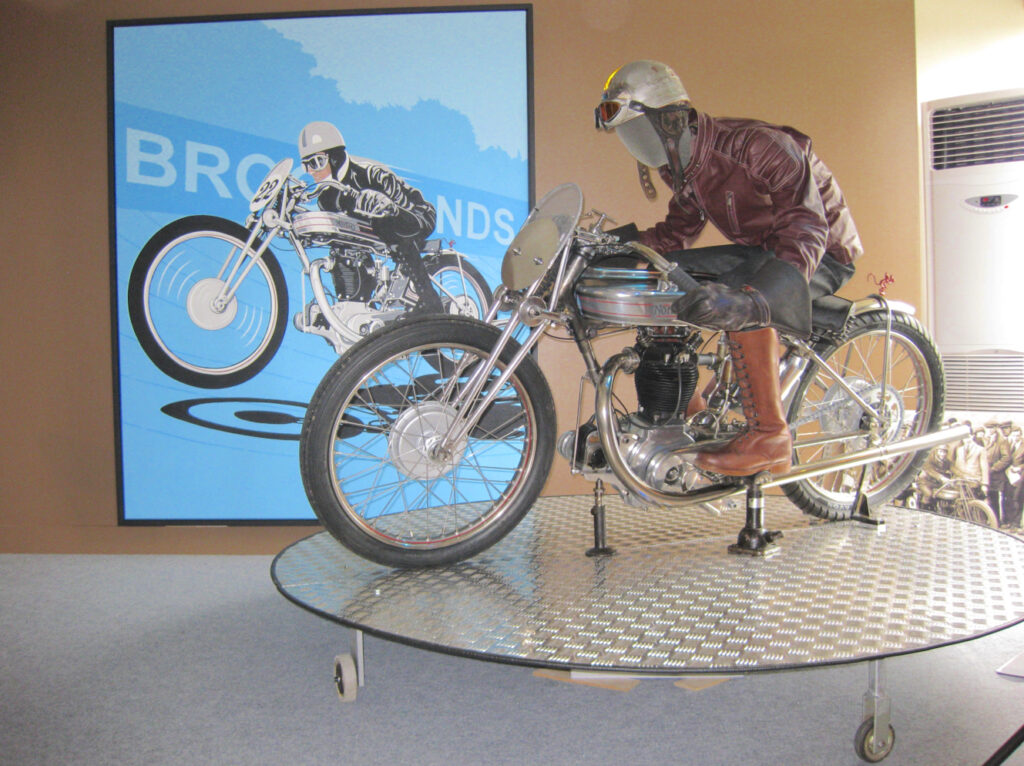

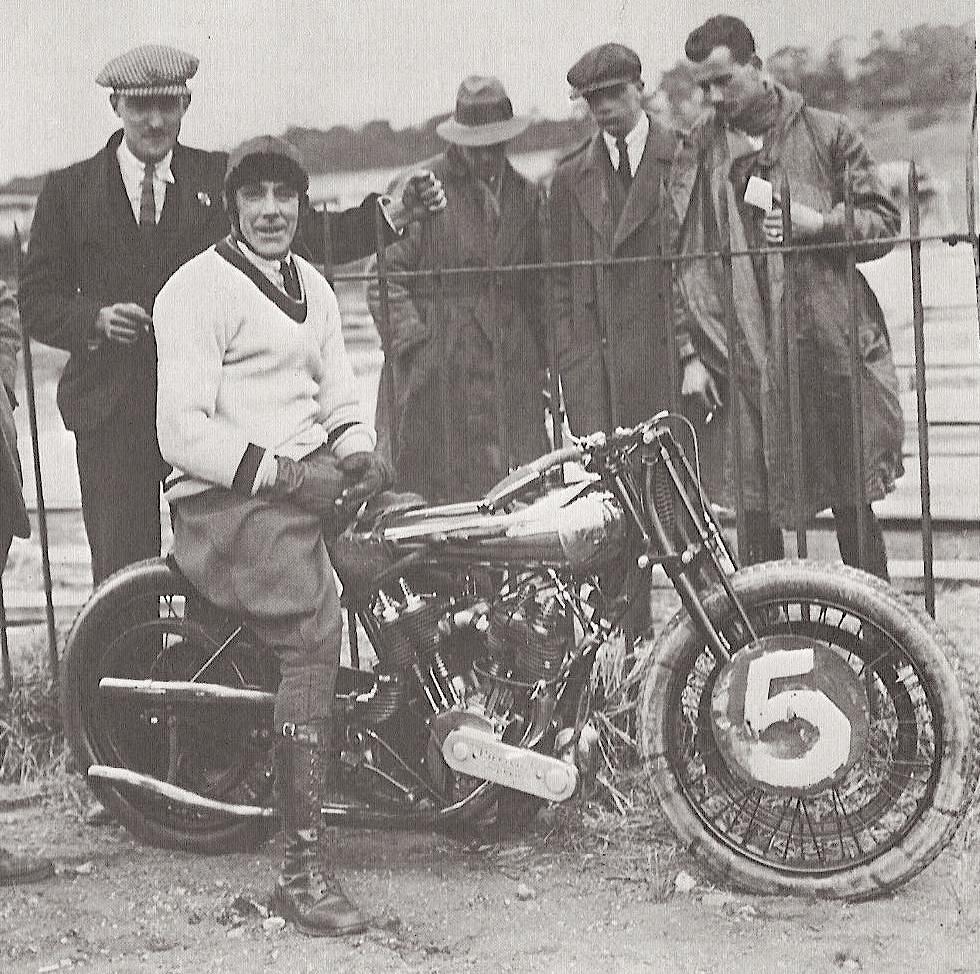

'Brooklands George' - Conrad Leach

The Vintagent presents Brooklands George, a 2008 painting by Conrad Leach, 50x60", acrylic on canvas. Commissioned by the late Dr. George Cohen ('Norton George'), and originally displayed at the Dunhill Drivers Club during the 2008 Goodwood Revival meeting. Being sold on behalf of Sarah Cohen. Price on request: contact us here.

The paintings of Conrad Leach are iconic, because for years he has explored the imagery that creates icons. 'Brooklands George' (2008), while depicting a particular man, motorcycle, and location, is also timeless, featuring the shape of a machine built for speed, an evocative locale, and a hunched-over racer pushing the limits of speed and danger. Leach's influences range from 20th Century movie posters and advertising, to art/historical references like Beggarstaff posters and Roy Lichtenstein's graphic blasts. His cool surface technique is contradicted by saturated colors and a strongly contrasting ground, plus the kinetic, magnetic appeal of his human and mechanical subjects.

Conrad Leach is best known for his exploration of heroic imagery, from British racing vehicles (motorcycles, cars, planes) to contemporary Japanese pop stars and Ukiyo-e woodcuts. He's not a nostalgist, but responds on canvas to people, machines, and events from the past and present that resonate with our culture. He explains , ‘So much is sexy from the interwar era! The Supermarine Schneider Trophy racer, Malcolm Campbell’s Bluebird, the Brough Superior ‘Works Scrapper’, are nearly forgotten today, but the aesthetics of the era are so pure and functional. This was pretty radical stuff back then, but my work has to be relevant now, as I’m not interested in recreating the past. My painting technique is contemporary, even Pop, and attempts to create resonance between a viewer today and images from that era. To take an enormous bespoke object like the Bluebird onto Daytona beach in Florida and attempt to go faster than any human, that required an incredible train of thought, and I’m trying to get into the heads of those people.”

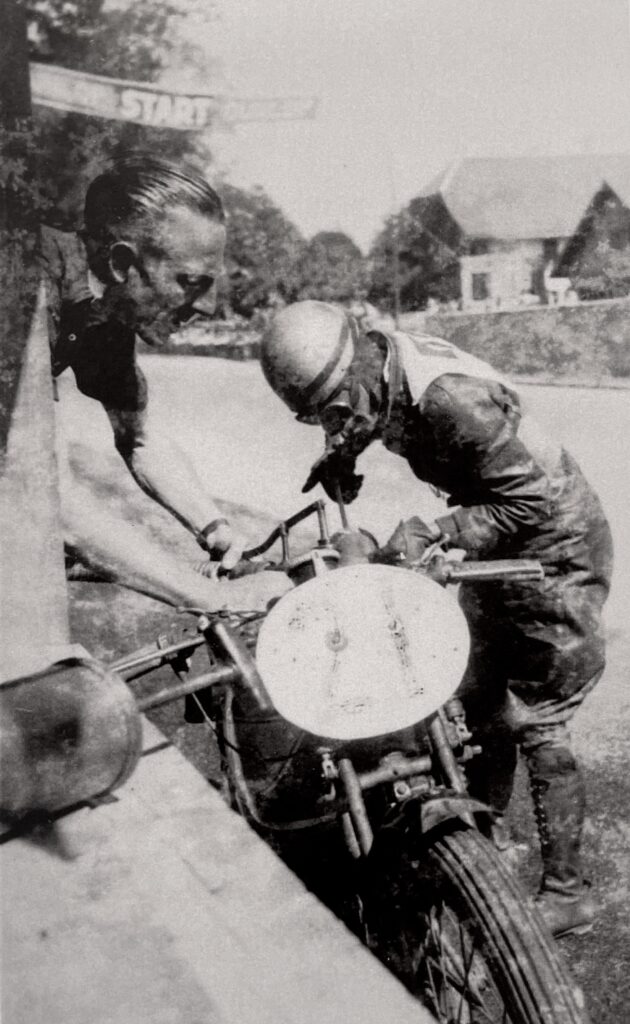

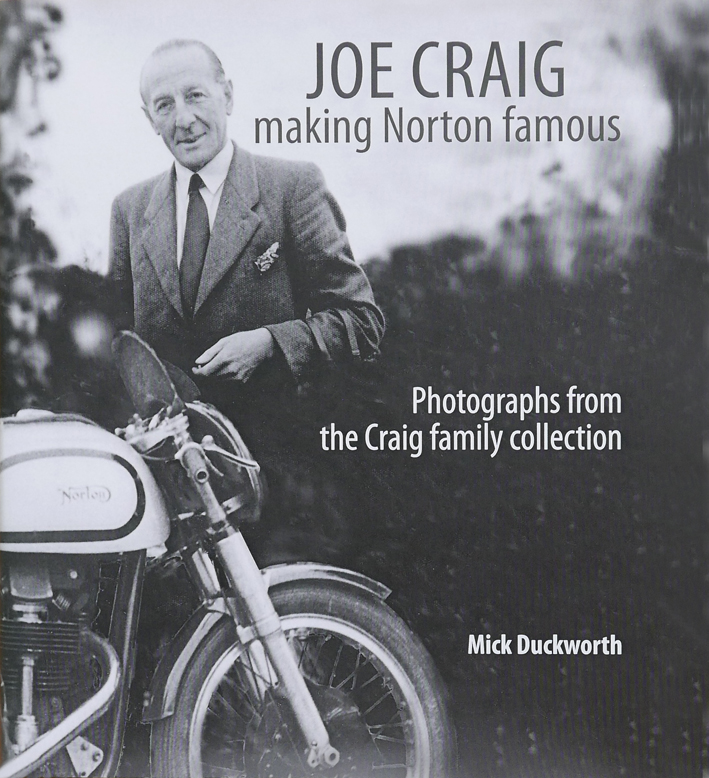

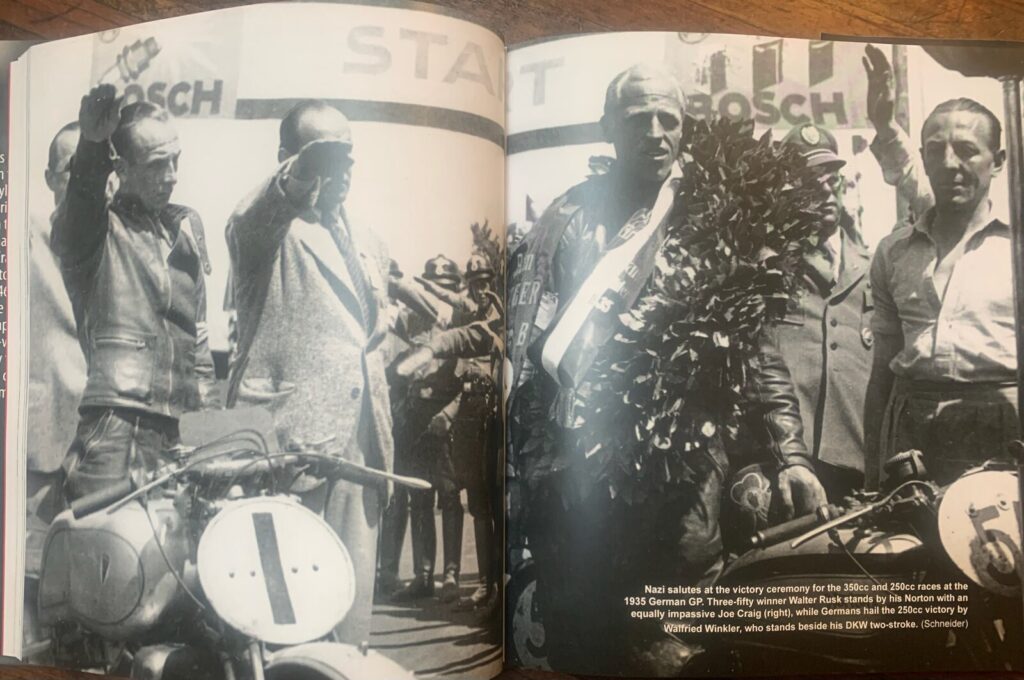

'Joe Craig: Making Norton Famous'

If any single person deserves credit for Norton's extraordinary decades of racing dominance from 1930 through the mid-1950s, it must be Joe Craig. The de facto racing team manager for Norton under several owners, Craig at first successfully raced the factory product himself in the 1920s, then switched to the role of development engineer in 1930. He held that position (despite a break from the company during WW2) through 1955, when postwar company owners Associated Motor Cycles (AMC) decided exotic factory specials could no longer be supported financially, and focussed on selling factory catalogued racers like the Norton Manx, AJS 7R, and Matchless G50 models, all of which were produced simultaneously under their corporate ownership.

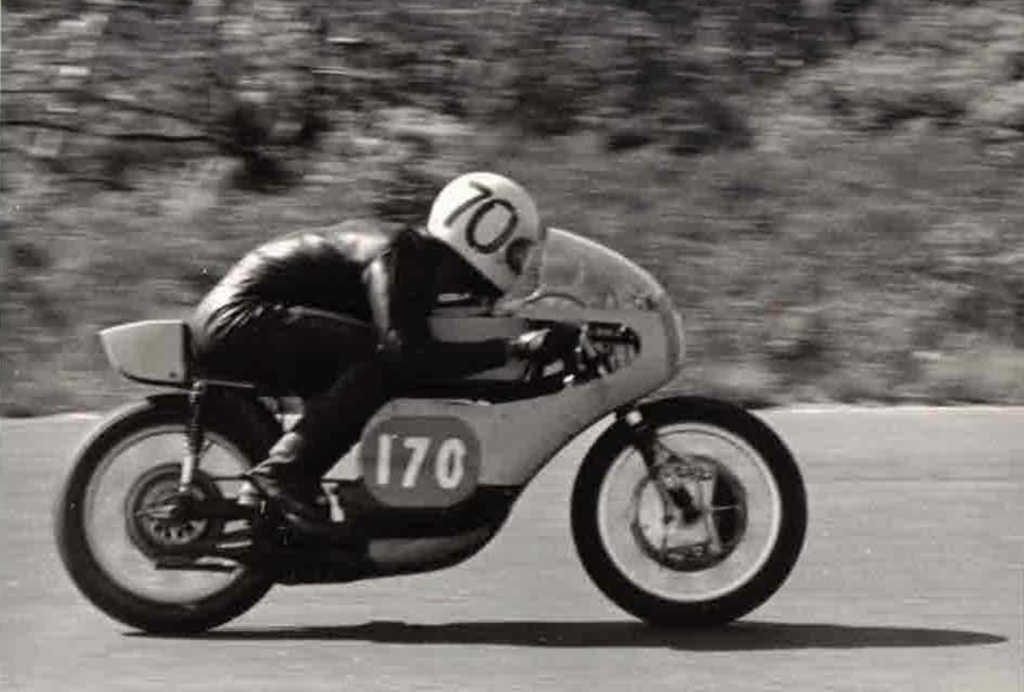

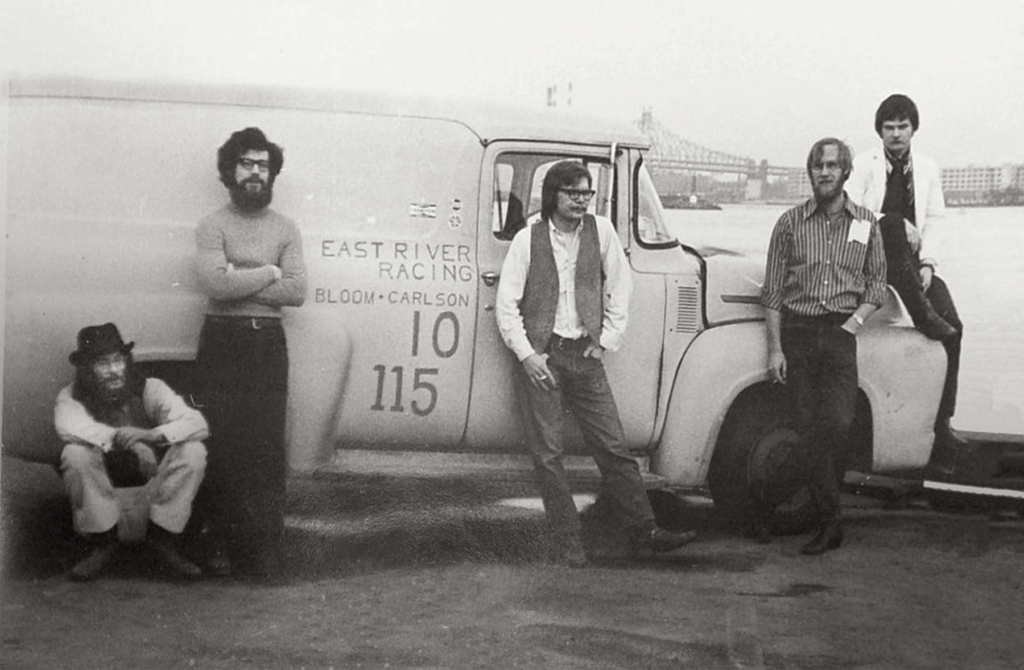

East River Racing in the 1970s

By Sandy Hackney

The story of East River Racing began in September 1969, all because I had been seen risking life and limb on a ’69 Yamaha YDS3 (250cc) on a series of curvy roads in Durham, NC that Summer. A mechanic at the local Yamaha shop said to me, “You should race.” Huh? But the seed was planted, and there was a AAMRR Labor Day race weekend coming up at VIR; it was several days long and featured one 5-hour race. After exploring this some, I approached a local roofing company, who fashioned a set of expansion chambers to TD1 specs and I was set! Top speed was increased to about 110mph; damned thrilling.

Soon we had a core group made of several colleagues from the Respiratory Therapy Department at NYU Medical Center; we were all in our early 20s and in love with motorcycles. We rented a storefront on E. 12th between 1st and 2nd Ave, and East River Racing was truly born. Our truck was purchased by me from a NC monk for $80. A great deal. We added a couple of fine women as tuners - and more. One tuner is married to this day to Bill.

RIDE 70s Spring Raid Invitational

[Editor's note: Vintagent Contributor Fabio Affuso recently founded a moto-touring company with seasoned petrolhead Pietro Casadio Pirazzoli, RIDE 70s, using classic (mostly) Italian bikes to explore classic Italian landscapes. For the inaugural tour of RIDE 70s, he chose Tuscany, and invited a dozen friends and journalists to test the bikes and his organizational skills. HIs Spring Raid Invitational last month coincided with my own tour of Italy on classic Italian bikes, otherwise this would be a first-hand ride report!]

To celebrate the beginning of our RIDE 70s touring season in Italy, we were thrilled to guide an eclectic group of friends on an unforgettable expedition, a motorcycle journey across the picturesque landscapes of Tuscany.

Continuing our journey reinvigorated, we arrived in the enchanting town of Montepulciano, renowned for its Renaissance architecture and exquisite wines. Here, we reveled in the rich flavors of Tuscan cuisine, savouring pecorino cheese, handmade pici pasta, and tender braised wild boar. The indulgence was accompanied by the velvety notes of Nobile di Montepulciano wine, adding a touch of elegance to our dining experience.

The Anamosa Broughs: a Superior Collection

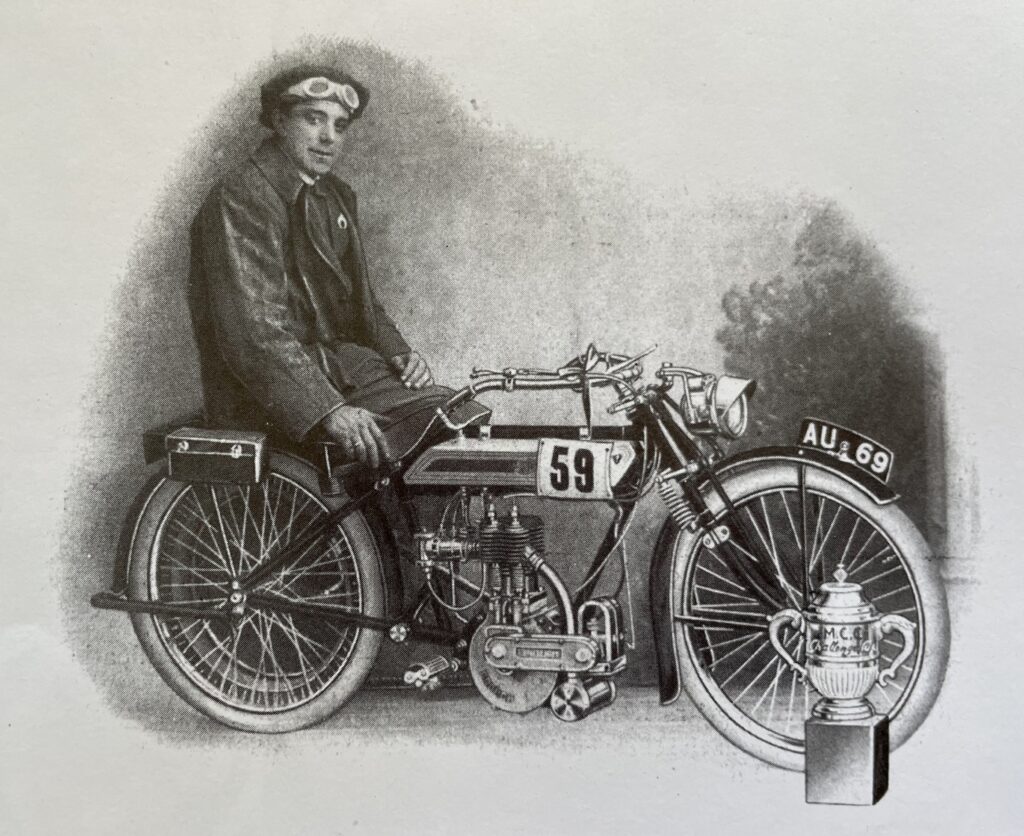

It might have seemed the height of pretense to label a new motorcycle company ‘Superior’ in 1919, but George Brough had a vision of building the fastest, most elegant motorcycles in the world, and delivered. His father William built well-respected motorcycles in Nottingham from the 1890s, and commenced his own brand – Brough – that earned a reputation for high quality. Young George was the factory’s official competitor in road and off-road events, which he often won with panache.

During WW1, George Brough envisioned manufacturing an ultimate high-performance motorcycle, but his father refused the concept, so George set up his own factory nearby. He assembled the best racing components from engine, gearbox, forks, and wheel manufacturers for his first model, the Mk 1 of 1919. It used a J.A.P. racing OHV v-twin motor of 1000cc and a heavyweight Sturmey-Archer 3-speed gearbox, in a very robust frame with a long wheelbase, crowned with the world’s first round-nosed saddle fuel tank, resplendent in nickel plating, black paint, and gold pinstriping. A friend suggested he call it ‘Brough Superior’, as it so clearly was, but father William was not amused, presuming the family product was then relegated to ‘Brough Inferior’.

[Full disclosure: Mecum Auctions is a sponsor of The Vintagent]

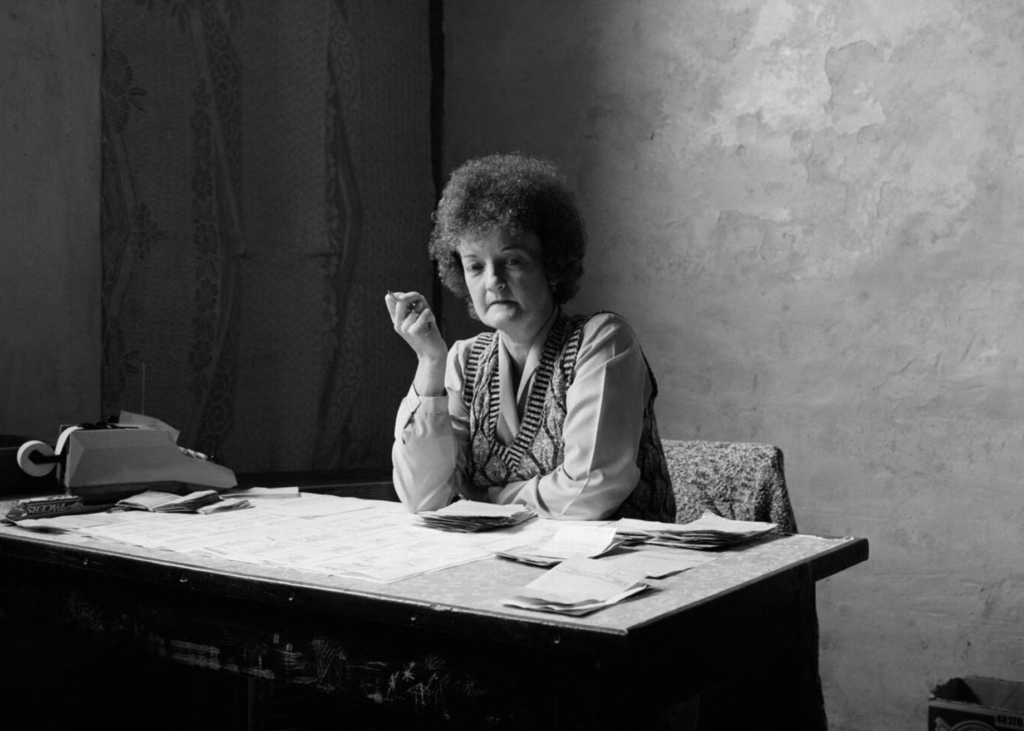

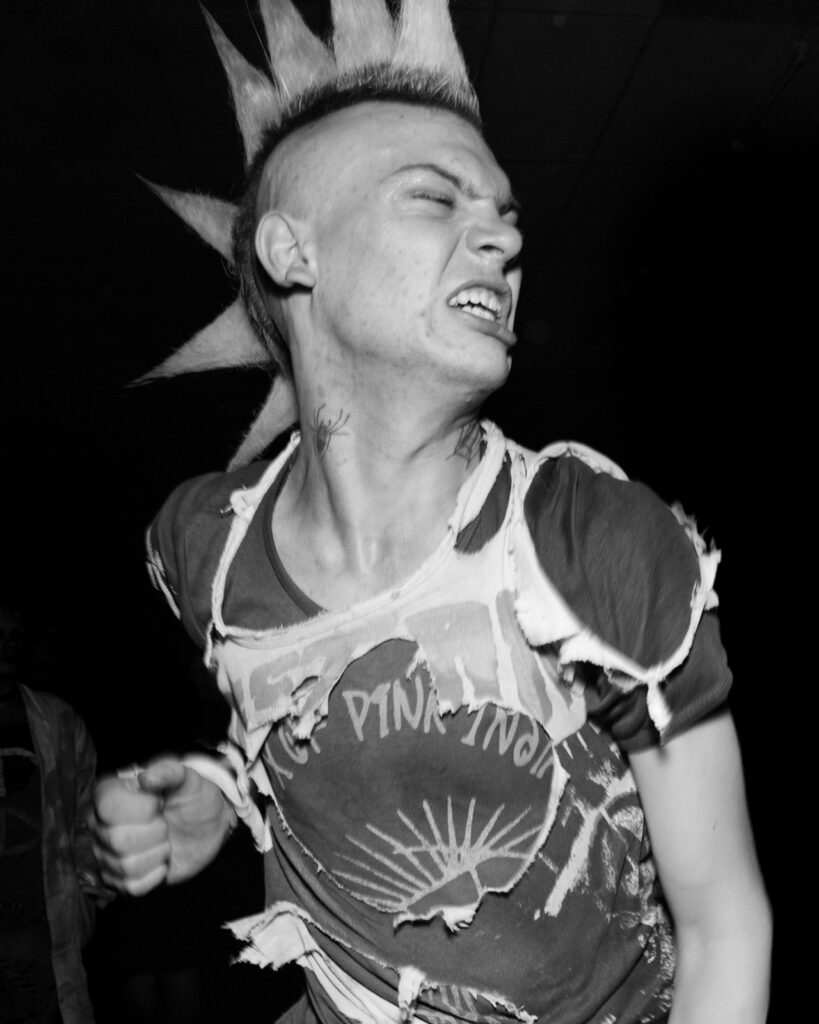

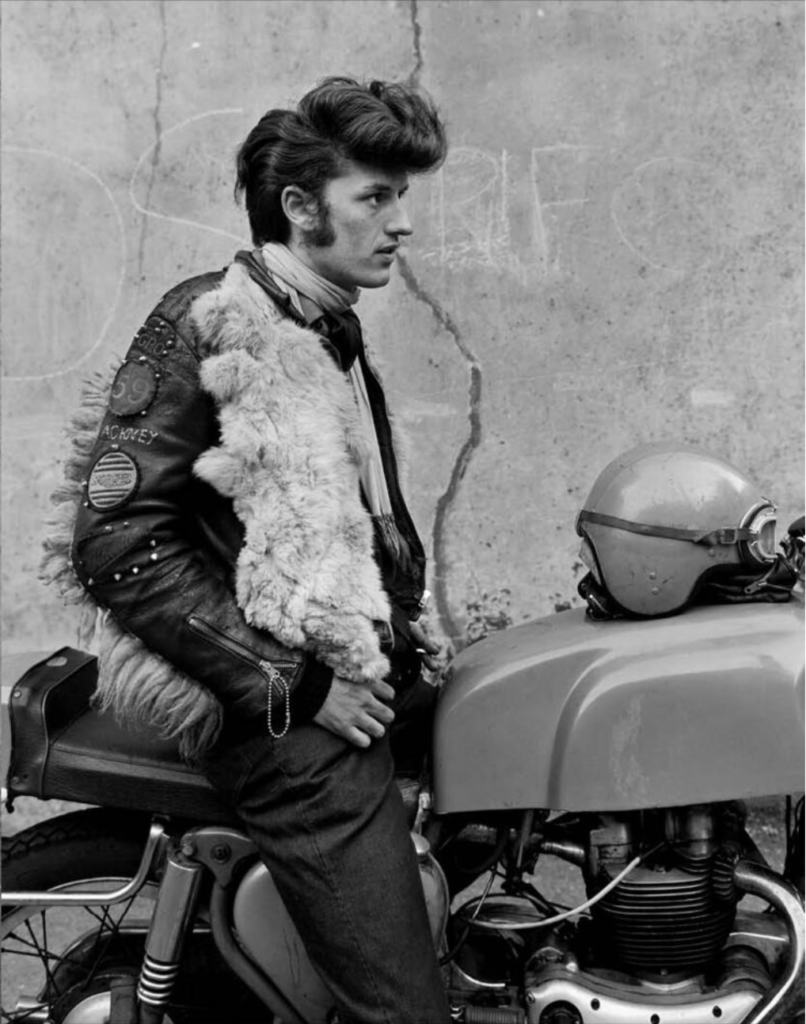

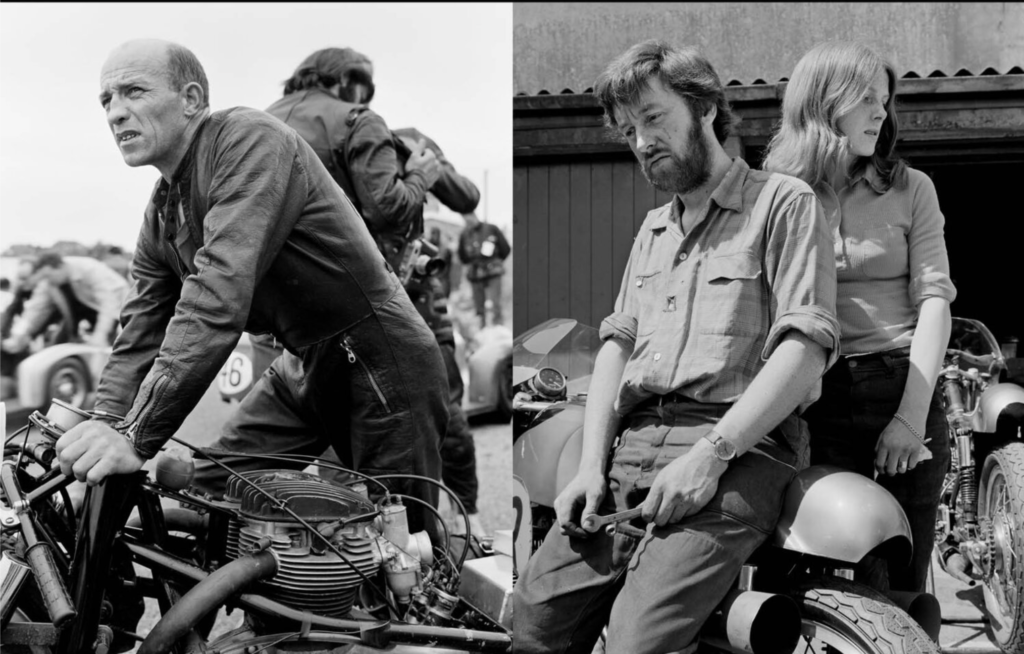

A Chris Killip Retrospective

While photographer Chris Killip was known as a social documentarian, his upbringing on the Isle of Man meant it was inevitable he'd take a few extraordinary moto photos. A legend in photographic circles, and a professor of visual and environmental studies at Harvard from 1991-2017, Killip was born in Douglas, where his parents owned the Highlander Pub - perhaps you've had a pint there on a trip to Mona's Isle? Who knows what inspired the son of pubholders to take up a camera as a profession, but of course, a public house is a natural place to develop one's skills at social observation at a neutral distance: the parade of customers passing through are highlighted on a gimlet-lit stage, locals and tourists in a never-ending spectacle.

From the project 'In Flagrante' 1973-1985. [Chris Killip]

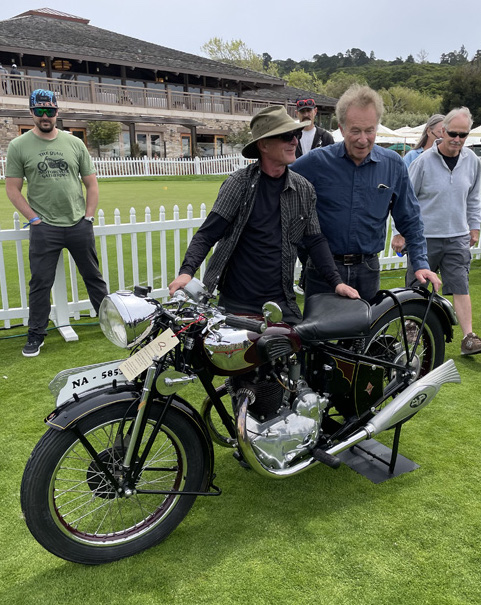

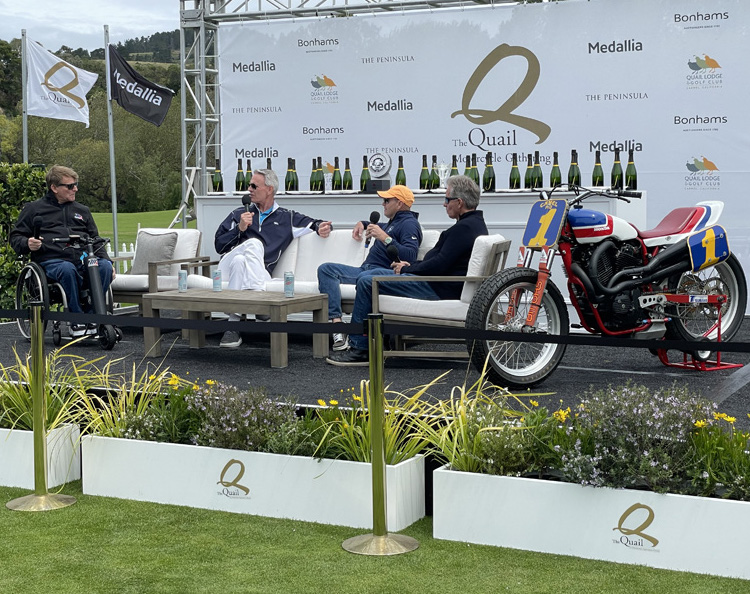

2023 Quail - No Rain, No Pain

California has been swimming an atmospheric river so long its residents are traumatized, tired of getting wet, and pulling U-turns at the first sight of an orange cone. That might be an explanation for the dozen empty spots on the grass at this year's Quail Motorcycle Gathering, or it could simply be lucky year #13 parsing the solidly committed from the those who let a 20% chance of rain convince them to miss a pretty amazing weekend.

The Ultimate Collector Motorcycles - Taschen

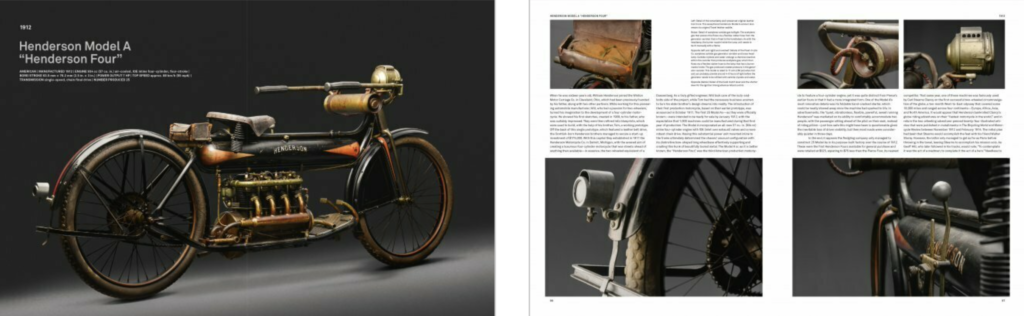

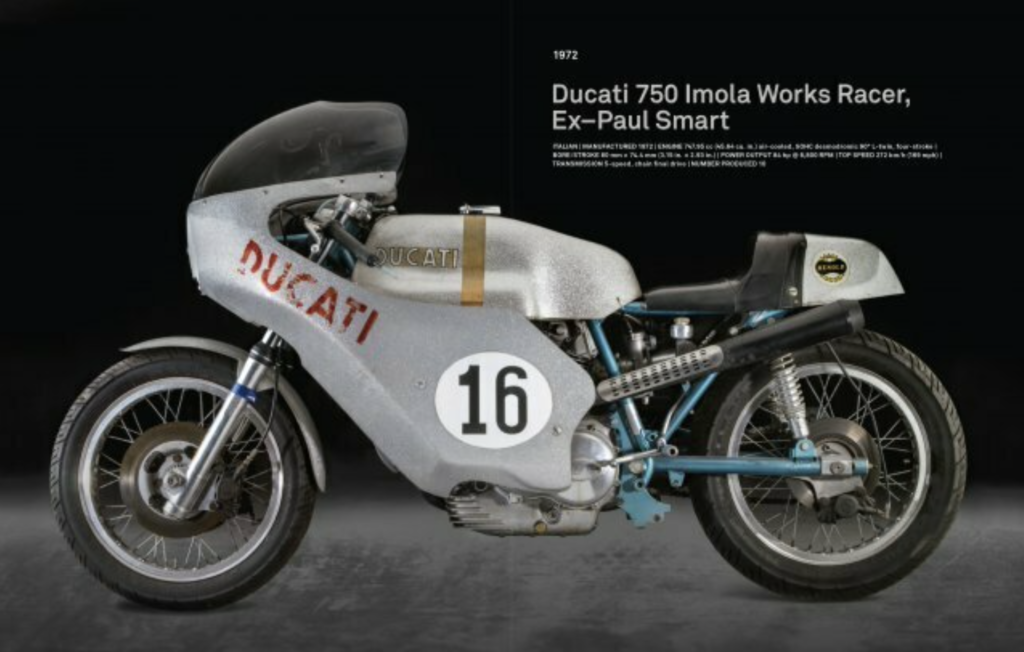

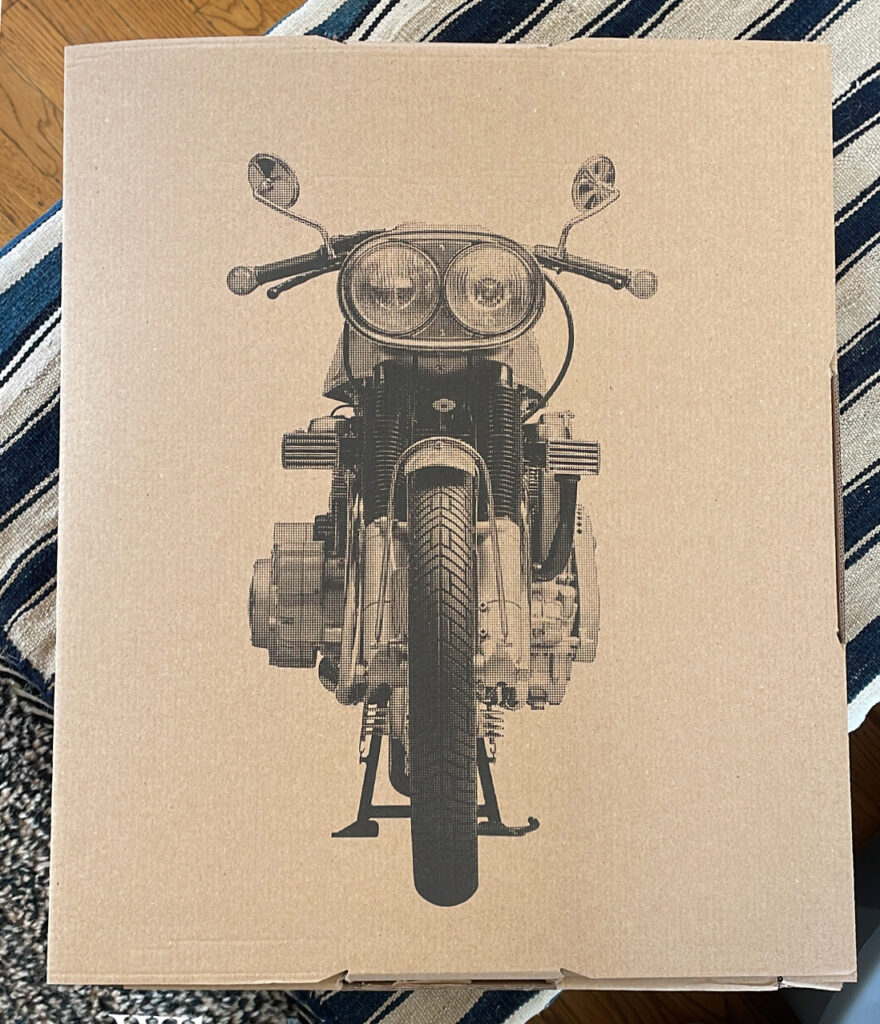

I had the pleasure of advising on (and being included in) a mammoth new project from publishers Taschen: the 2-volume set of The Ultimate Collector Motorcycles, a 20lb behemoth in a lovely slipcover with several cover variations - my advanced copy has a Münch Mammüt, but I've also seen a Brough Superior Golden Dream and Gilera Four GP. The books are written by Peter and Charlotte Fiell and edited by Taschen; it's a real blockbuster, and like nothing else published about motorcycles. The intent was to revisit the idea of a Top 100 list of the most important ('collectible') motorcycles, and the bikes were sourced from around the world, in private collections and museums, representing a truly remarkable array of machines...some of which I've Road Tested on The Vintagent!

Support The Vintagent! Order your Collector's Edition ($250) here with free shipping anywhere in the world!

Order your Fine Art Edition ($850) here, it's the most lavishly produced motorcycle book EVER!!! It comes in two separate slipcases, and has a tipped-in cover photo printed on metal, with an extraordinary deep gloss, silver paper edging, and larger size (11.25x14.5"). It's so impressive, we sold four at the Quail Motorcycle Gathering - there's really nothing like it anywhere!

From Taschen PR:

"Dream Rides: the most spectacular bikes on the planet. From the 1894 Hildebrand & Wolfmüller to the 2020 Aston Martin AMB001, this book lavishly explores 100 of the most desirable motorcycles to have ever sped thrillingly around a circuit or along an open road. From pioneering record-breakers, luxury tourers, and legendary roadracers to GP-winning machines, iconic superbikes, and exotic customs, this book celebrates motorcycle design and engineering at its highest level. Many examples are from acclaimed private collections and very rarely seen. Others are the all-out stars of renowned motorcycle museums - such as teh 1938 Brough Superior 'Golden Dram' or the 1957 MV Agusta 500 4C, which took John Surtees to World Championship glory. Alongside some early survivors in astonishingly original condition is a stable of fabled racers - the actual machines that were competed on by the likes of Dario Abrosini, Tarquniio Provini, Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini, Barry Sheene, and Kenny Roberts.

The fascinating stories behind these fabulous motorbikes are expertly recounted in detail, alongside stunning imagery specially taken for the book by the world's leading motorcycle photographers. Also included are rare archival gems, from early posters to remarkable action shots. In addition, there is a forward by legendary petrolhead Jay Leno, and interviews with George Barber, founder of the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum; Sammy Miller, championship-winning racer and founder of the Sammy Miller Motorcycle Museum; Ben Walker, Department Director of Motorcycles at Bonhams; Paul d'Orléans, founder of The Vintagent; and Gordon McCall, cofounder of the Quail Motorcycle Gathering, the world-renowned motorcycle concours event.held in Carmel Valley, California.

We'll have discounted copies available soon on The Vintagent - stay tuned! The 'famous first edition' is limited to 9000 copies, while there's an art edition of 1000 copies coming too - more details to follow on our Instagram and Facebook pages.

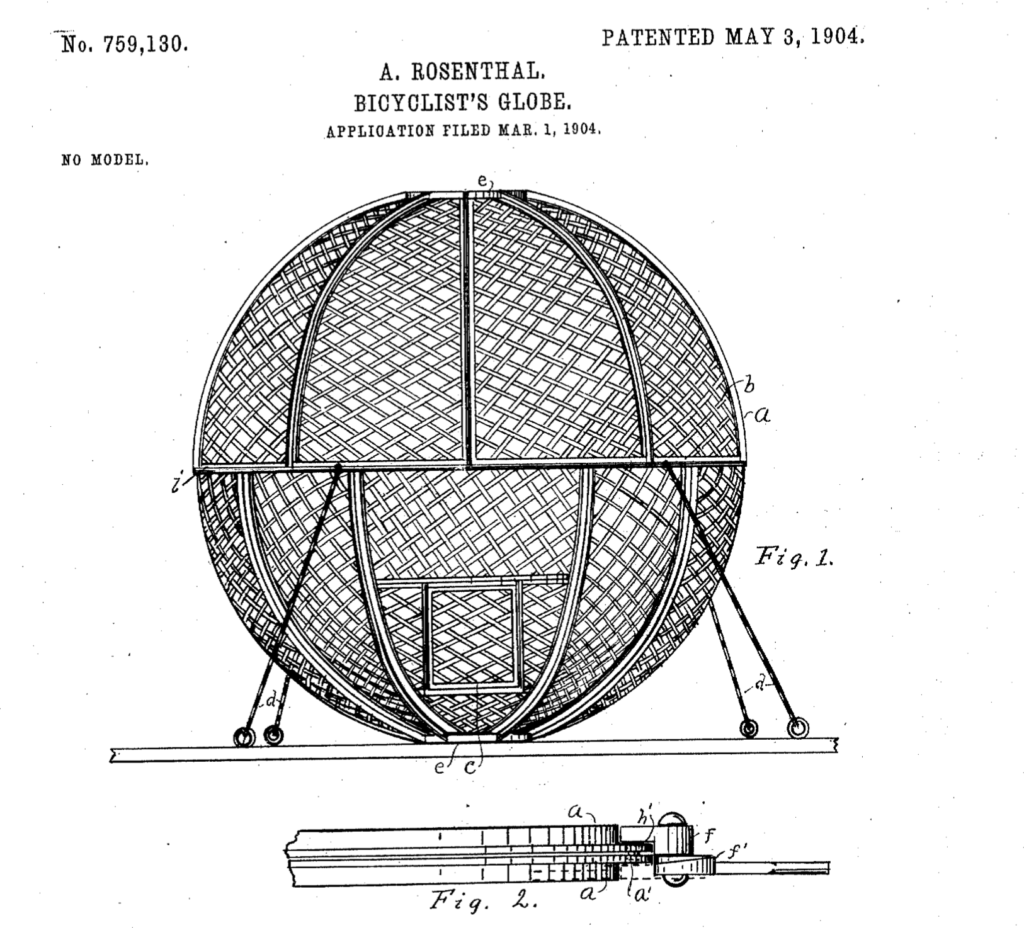

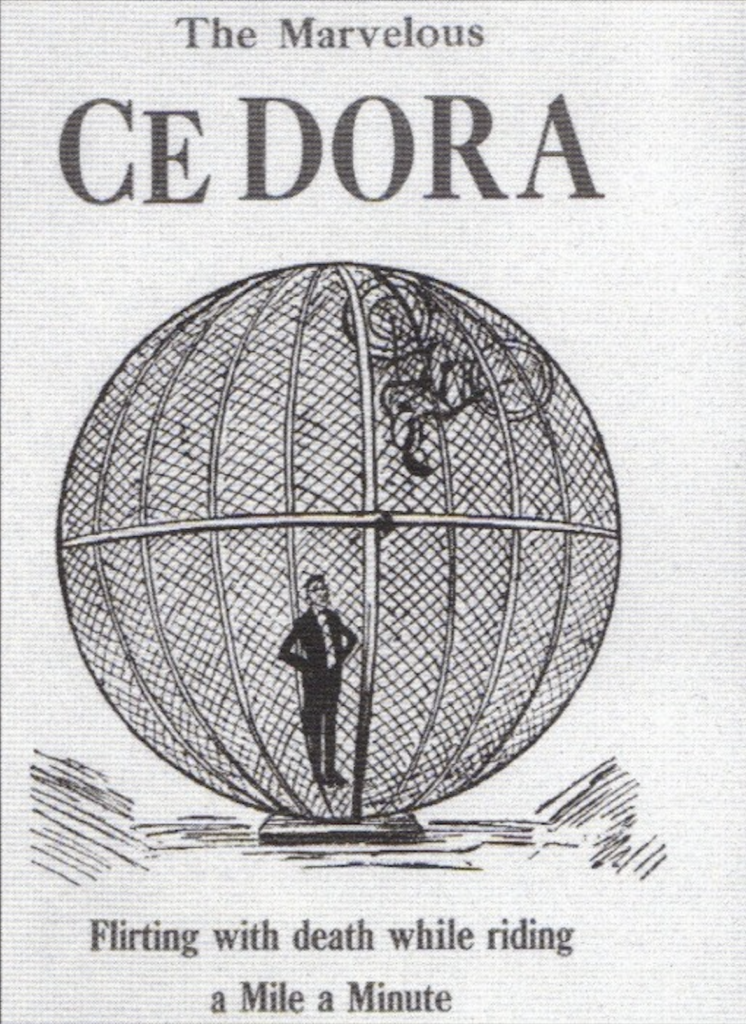

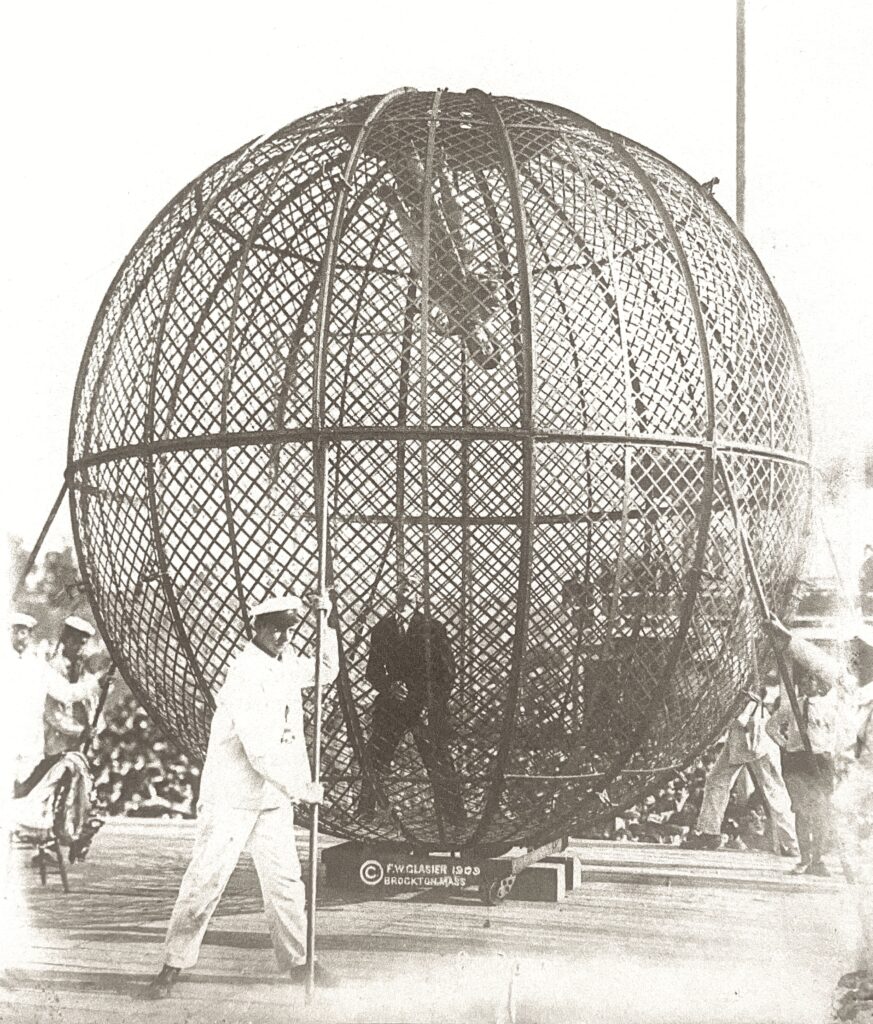

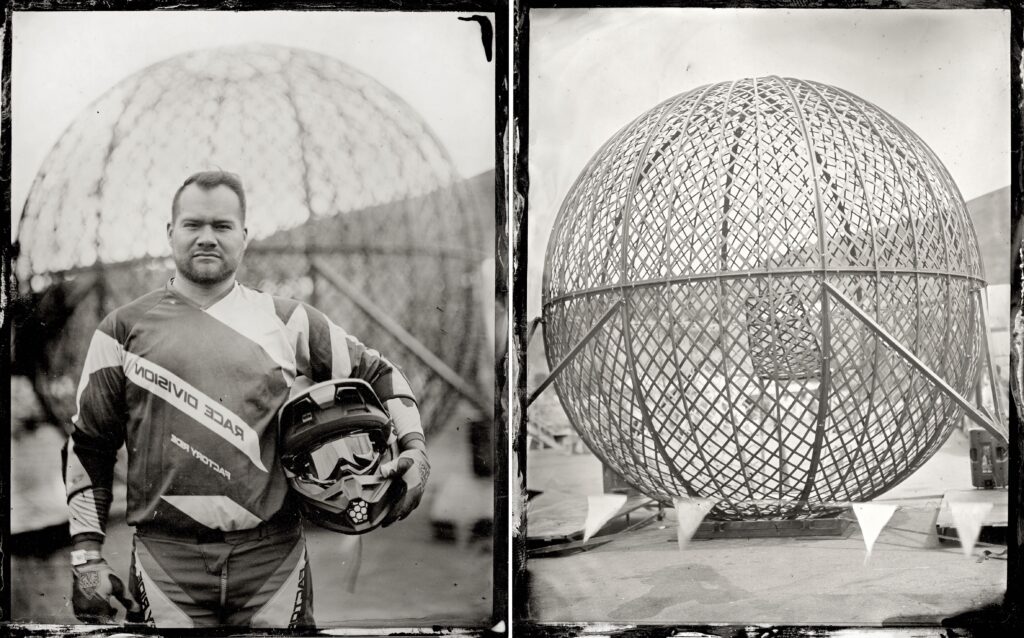

CeDora and the Globe of Death

CeDora. Or Ce'Dora, or C'Dora. Everyone on the Vaudeville circuit had a stage name, and young Greek immigrant Agnes Theodore chose a homophone of her given name as the character for her death-defying motorcycle act in the early 1900s. CeDora rode into history as the first woman to perform in a Globe of Death, and her fame continued even after she retired, as her stage name was used for two generations, when another young woman, Eleanore Seufert, took over as CeDora, riding the Globe of Death through the 1930s.

Agnes Theodore began her Globe of Death career as a bicyclist sometime in the 'Noughts, with her husband Charles Hadfield as a co-rider, stuntman, and manager. Hadfield was a bicycle race promoter who saw the potential of this new act, which they originally called the Golden Globe, a 16' diameter steel sphere made of woven strip steel and a tubular steel frame. The earliest CeDora exhibition posters (from 1905?) show her riding a bicycle exclusively, alongside a male rider, presumably her husband Charles.

The Rarest of Racers: 1915 Indian 8-Valve

Say the words ‘8-Valve’ to a motorcycle collector and watch their ears perk up. That’s how potent the history of these exotic machines, built by both Indian and (later) Harley-Davidson, are in the story of American board track racing. It’s the most romantic era of motorcycle competition, mostly because of the extraordinary danger of the sport, it extreme toll on riders, and the bare-knuckles competition between brands that understood racing was the cheapest form of advertising. It was ‘Race on Sunday, sell on Monday’, and even if your star rider slipped on the two miles of oily pine 2x4s laid at a 50degree angle, and lost his life… well, that was a headline too. For a time in the 1910s, every major and many minor cities in the USA featured banked-track ovals with wooden surfaces, called either motordromes, autodromes, or board tracks. By the late 1920s they were all gone, destroyed by fires or bulldozers, and few missed the ‘murderdromes’, as they were dubbed in the press. Other forms of racing quickly supplanted the boards in the public’s imagination, with hillclimbing becoming the most popular motorsport in the USA by the late 1920s, and dirt track racing the most popular in the world.

Do You Know the Monster Man?

[A version of this article originally appeared in Cycle World magazine]

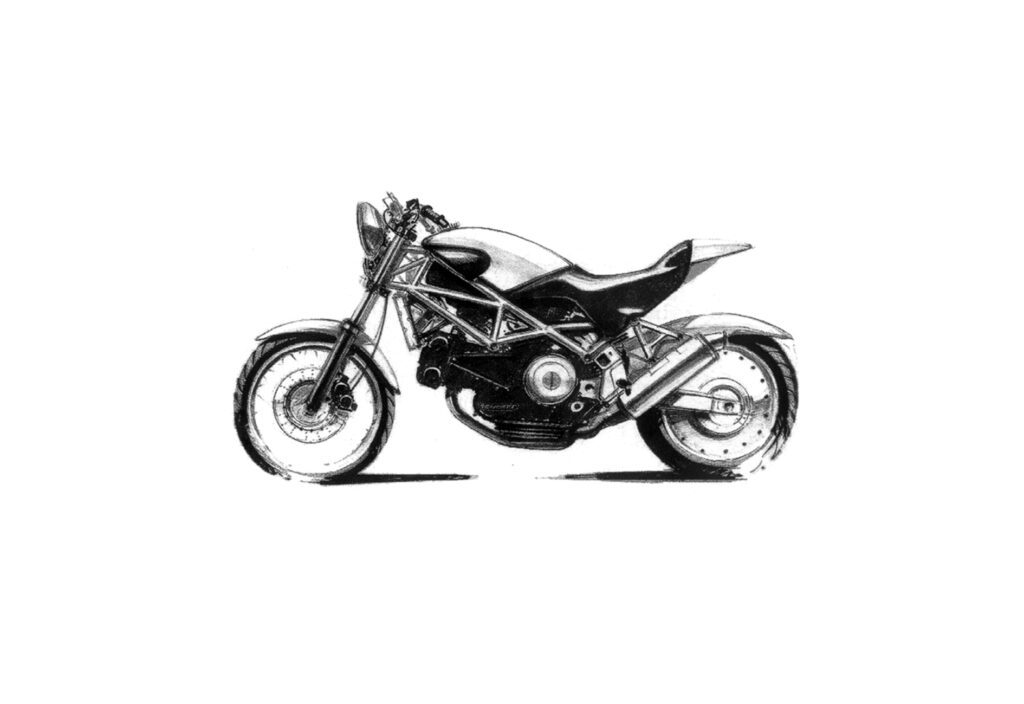

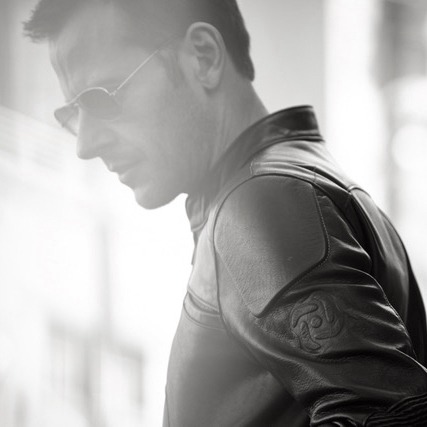

Legendary motorcycle designer Miguel Galluzzi is as refreshingly direct as his most famous creation, the Ducati M900 ‘Monster’. When it was released in 1993, the bare-bones Monster was considered revolutionary, which speaks more about 1990s sportbike design than its status as the ‘first naked bike’. Regardless that motorcycle history was, like Eden, pretty much all naked, the mantra of ‘90s sporting motorcycles was all-plastic-everything, and Galluzzi landed in the thick of it, after a stint designing cars at GM/Opel in Germany. “I was getting fed up with the car business; each project took 10 years to develop – just too long. My boss Hideo Kodama heard that Soichiro Honda wanted a Honda motorcycle design studio in Milan, to understand how things were done in Italy. They hired me to start the studio in 1987”.

Artists have been messing around with Xerox machines since they were invented, so it's only appropriate a legendary motorcycle design was developed on Xerox too. Enjoy 'Photocopy Cha Cha' (2001) by Chel White, a film made entirely from sheets of color Xerox paper. [Bent Image Lab]

The Monster’s birth was midwifed by an early ‘90s high tech device - a color copier. “We had the first color Xerox machine at our office, so I copied magazine photos of a bare chassis, and drew some simple lines with minimal bodywork, like bikes had been since the beginning of time. The form of what a bike should be; just enough to enjoy the ride.” In the summer of 1990 Galluzzi asked his boss if he could pick up some parts at Ducati. The 851 had just come out, and it was blowing people’s minds – the first twin-cylinder sportbike that could rev to 10,000 RPM. “I built a raw special using all factory parts, but the 4V engine was too expensive for my project. But we had plenty of 900ss motors lying around; it was affordable stuff, which meant a bike could be much cheaper. That was the beginning of the Monster”.

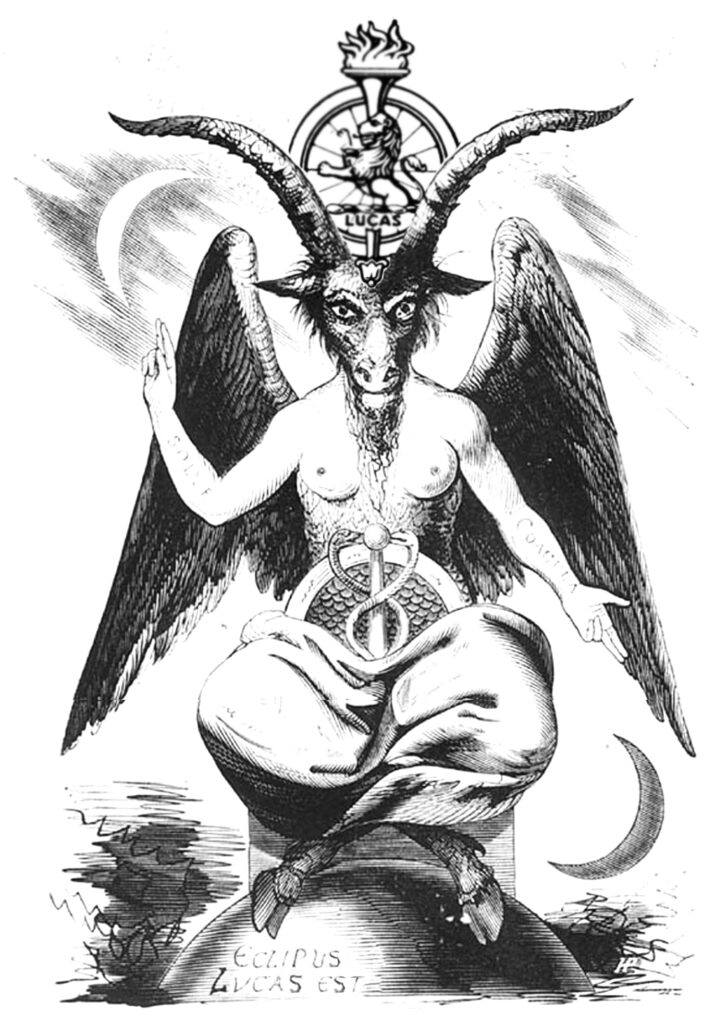

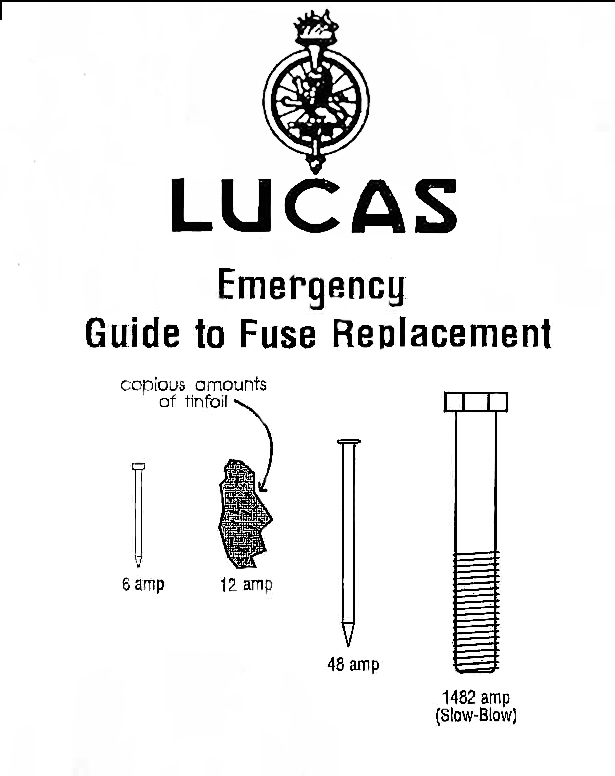

The Prince of Darkness, Exposed

‘We are born of Darkness, and to Darkness we return; our time in the Light is but an interlude” – Joseph Lucas.

Thus spake an incarnation of Beelzebub who lived in England at the turn of the 19th Century, a man of great industry and wealth who nonetheless by his insidious devilish nature perverted the course of the mighty river Commerce in the United Kingdom, diverting those once-powerful waters to be sullied and wasted over the sandy plains of Poor Reputation. By his trickery, an entire industry, once a world leader in technology, performance, and quality, was reduced to a worldwide butt of jokes and financial catastrophe, bringing the economy of an entire nation to its knees, and reducing that nation’s principal exports from the noble metals of Transport and Manufacture to the lowly pressing of musical discs, recording the harmonized mating calls of long-haired, drug addled dandies who wiggled their skinny asses to the gleeful delight of teenage girls, who wept at the sight.

(Note: any similarities to actual titans of British industry producing devilishly maddening, smoke-exhaling electrickery, is purely coincidental, and intended as satire)

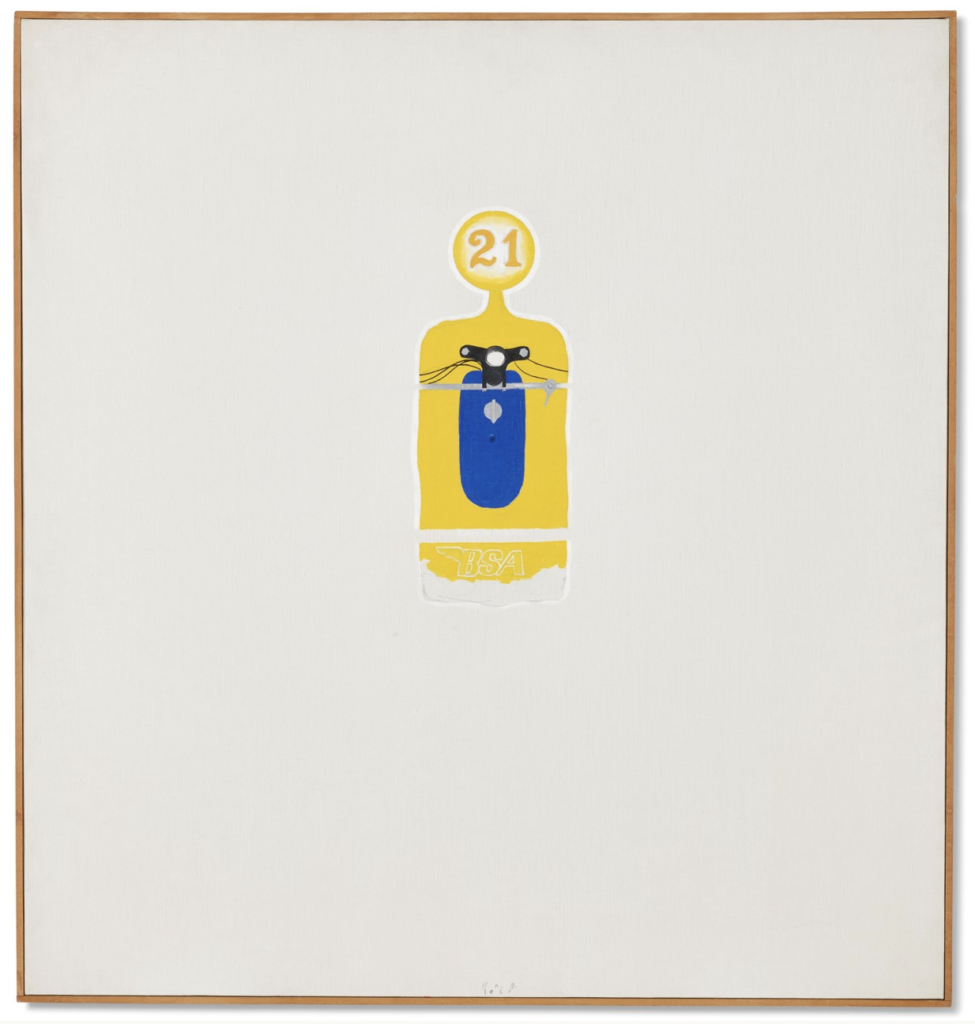

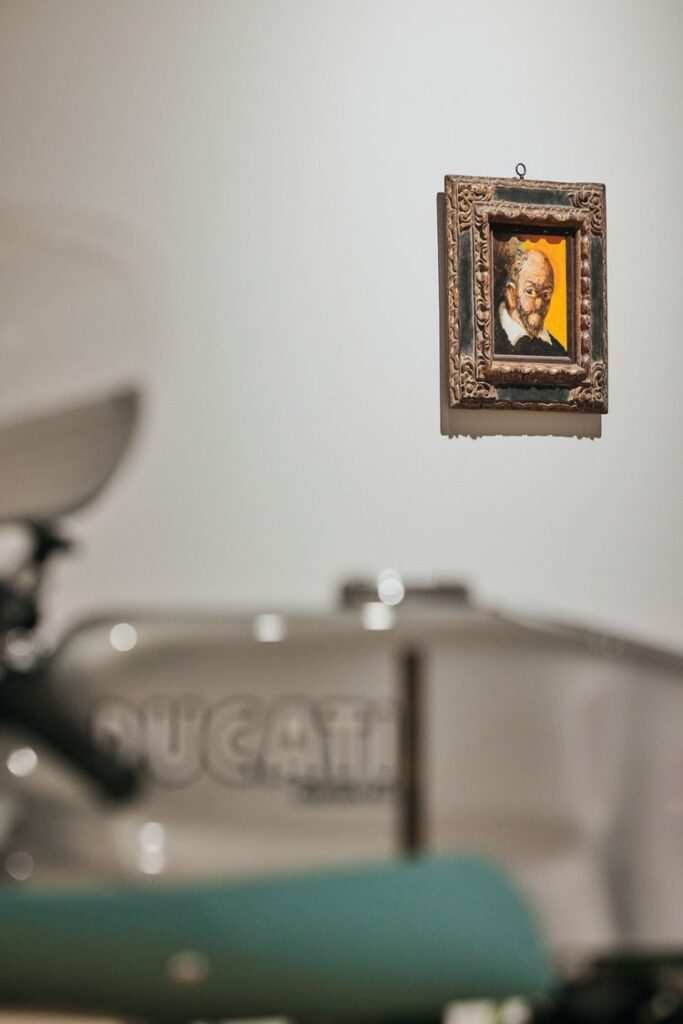

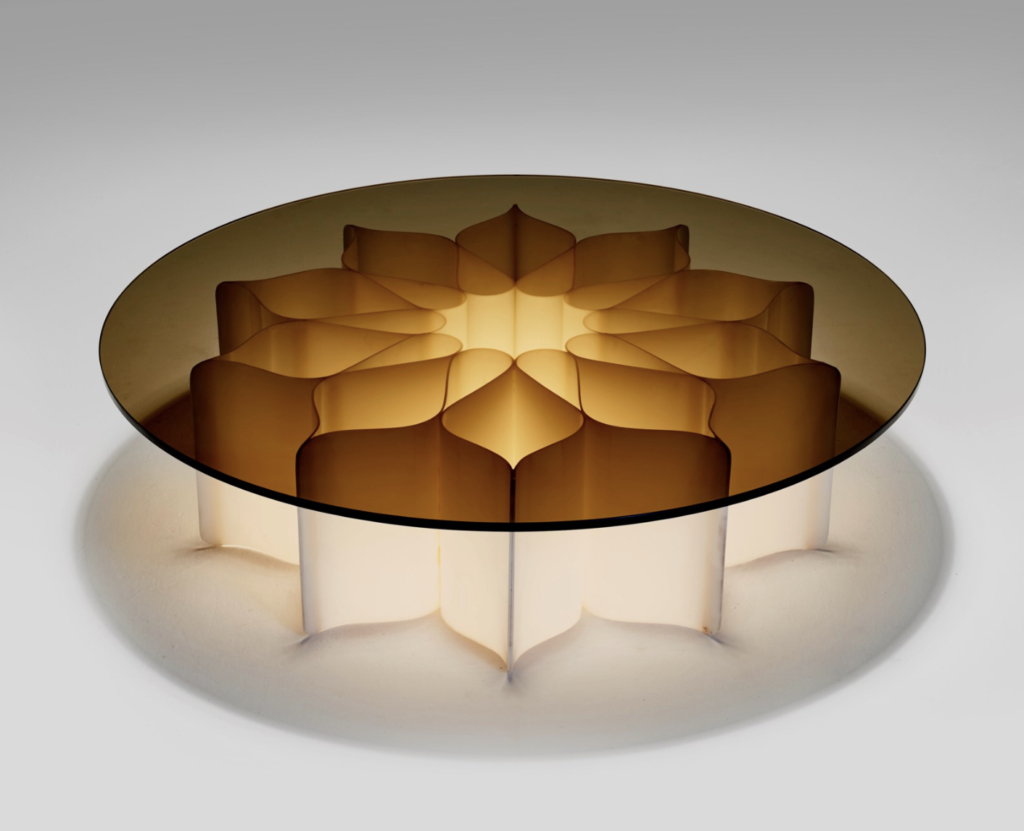

The ADAM sale: a First in the Art World

Art and motorcycles: can motorcycles be art? It's a question posed long before the 1998 Art of the Motorcycle Guggenheim exhibit flung its doors open amid Gehry-designed splendor, and became their most popular exhibit in their history. But the Art World - an amorphous culture absorbing penurious painters and billionaire corporate money launderers alike - deflects the question by leaning on a fine point of Beaux Arts distinction: it's art versus design, people, meaning if an object has a function other than elevating the spirit or stimulating the senses, it is thrown onto the elegant slagheap called design. But don't get your panties twisted: design objects are venerated too, and always have been. Before the standardized 19th C. Beaux Arts education laid down the laws on what is what in the arts (Fine vs. Applied), everything from suits of armor to tapestries to carriages to paintings were displayed side by side in the collections of the very wealthy, and the first museums - which were the same thing.

"Art exists and has existed in every known human culture and consists of objects, performances, and experiences that are intentionally endowed by their makers with a high degree of aesthetic interest." - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Despite the acknowledgement that motorcycles (and other vehicles) can be brilliant examples of industrial design, and that art + design exhibits and auctions are fairly common, I can find only one instance when the combo includes top shelf motorcycles + art + design: the ADAM sale happening tonight at Christie's NYC. There was another auction that came close: a Design Masters auction at Phillips in 2010 that botched sale of the very first Brough Superior SS100 prototype, when it was rumored the late Alain de Cadenet phoned in serious questions about the provenance of said Brough (to settle a score with its owner Mike Fitzsimons), which was then pulled from the sale at the very last minute. So much for the experiment in rolling an exquisite and unique motorcycle into a fancy NYC auction house. Perhaps the ADAM auction will fare better.

Paul d'Orléans (PDO): Are you excited about the sale?

Adam Lindemann (ADAM): Honestly, it's more like anxiety. A friend suggested we go to a private room at Christie's and drink champagne, and I said are you fucking high?

I put things in for ambience and to tell a story. Theress someting to surprise and tickle everyone. That's what I like about art collecting - the story.

PDO: Will you actually be in the room?

ADAM: No, I'll be sitting by my computer with a pencil, keeping track of how much things are selling for versus what I paid for them. I've never been in the room when I sold my (auction catalog) cover lots: when I sold my Jeff Koons cover lot, my Basquiat cover lot, etc. I was never in the room but it was never the 'ADAM' sale, so I was wondering if Adam has to be there for the ADAM sale? But the auction people told me no. At the end of the day, when the auction comes, it's business.

ADAM: A lot of the things I put in the sale for decoration, I put them in for ambience and to tell a story. When you look at the auction, there's something to surprise and tickle everyone. That was the idea - everybody gets tickled in a different way. There are two reasons for my selection: I like that the narrative. I like to tell stories. That's what I like about collecting: art is a story, and I like to tell stories. That's one part. The second thing is this is a mid-season sale. This is dead time, the weakest moment in the New York auction cycle. So when I'm doing a single owner sale at a dead moment, it's up to me to row the boat. I have to bring the eyeballs. I have to bring the attention. It's not like the May auctions when there are 10 Picassos and a Jeff Koons bunny and everyone's focused. This is like dead week. So I needed to throw in a lot of spicy lots like for color, for decor, and to look cool. I put very low estimates on the work because otherwise it's a snoozer.

ADAM: Well, I must have paid $120,000 for that painting. I didn't need to put it in the sale, but I put it in because he just died, and because I had the car thing going with the Richard Prince El Camino. If I put my estimate at what I paid, no one would bid, whereas if I put it in at $40 grand or whatever, and he just died, well, maybe somebody will go for it. But I would say that that piece is not there for the money. This sale is a historic moment for me, and I've sprinkled a little of the Billy Al Bengston cool on it, if that makes any sense.

PDO: That absolutely makes sense.

PDO: So, let's talk about the motorcycle: a 1974 Ducati 750 Super Sport 'green frame', widely considered among the most beautiful motorcycles ever made.

PDO: But the Ducati 'green frame' is special.

PDO: I've already noted that, compared to just about all the other design/art in the sale, the motorcycle is cheap. I mean, it's pinnacle design, and I agree with you, I think that particular model is undervalued. Compared to something as crude as an Indian 8-Vavle or Cyclone or Crocker, all worth worth half a $Million. So, this gorgeously designed vehicle seems like a bargain to me. And by the way, I'm also a big Italian fan - I've owned a lot of bevel drives twins and singles, I love the design, especially the engine castings, superb.

ADAM: So, this is a little moment in the motorcycle world.

ADAM: Well, I mean, Christie's called it the ADAM sale, which is totally outrageous. The idea that anyone could be so pompous and ridiculous to call a sale by their name is like, wow. So that's all them. The sale otherwise is all me, but they had the veto, right? They threw stuff out. As far as design, they asked for this and that and, and I included a lot of women because I wanted to be some balance of women and men. I didn't want just a bunch of dudes. And then I decided to put in a motorcycle and not a race car or any kind of a car...although I do have a painted Richard Prince El Camino, which is amazing. So I have that and I put in the Billy Al Bengston and I have the '89 car hood and then the motorcycle. Because as I said, it's one of my first motorcycles and it's one of my, it's kind of my favorite: if I had to pick one, that's the one. So to me, I just told a story, and motorcycles are more closely related to design. They have functionality. I mean, a car is a chair with four wheels, and the motorcycle is a seat with two wheels. Its pared down to the essential design as much as possible. And I think that at the end of the day there's more sex appeal in the motorcycle. It's just more visceral. You sit on it, it's between your legs. And so it told the story that I wanted to tell.

PDO: That's fabulous - thank you!

ADAM: Oh, thank you. I'm so happy to be a small part of The Vintagent.

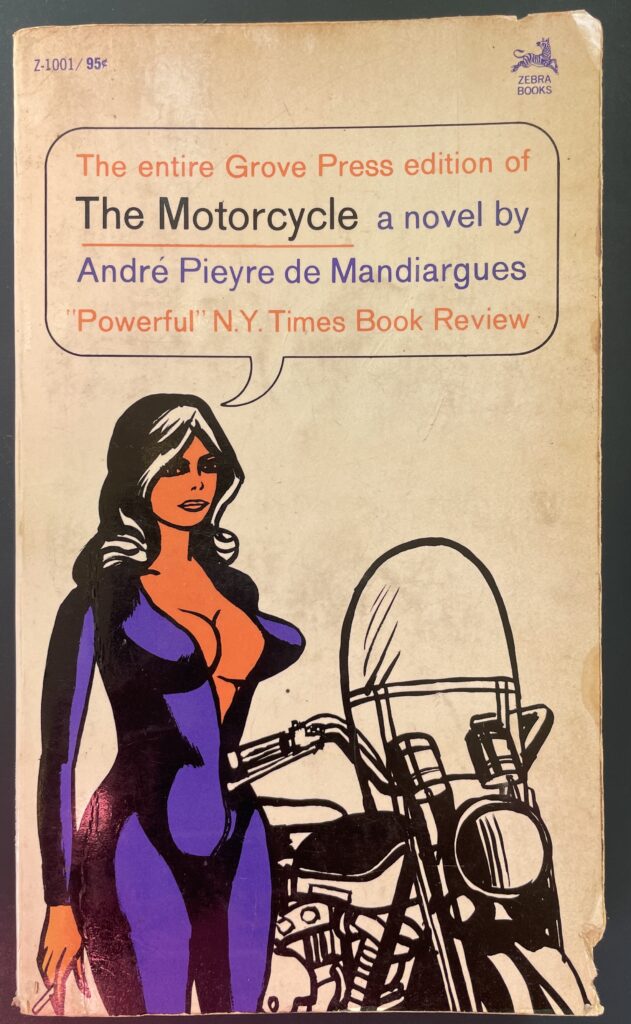

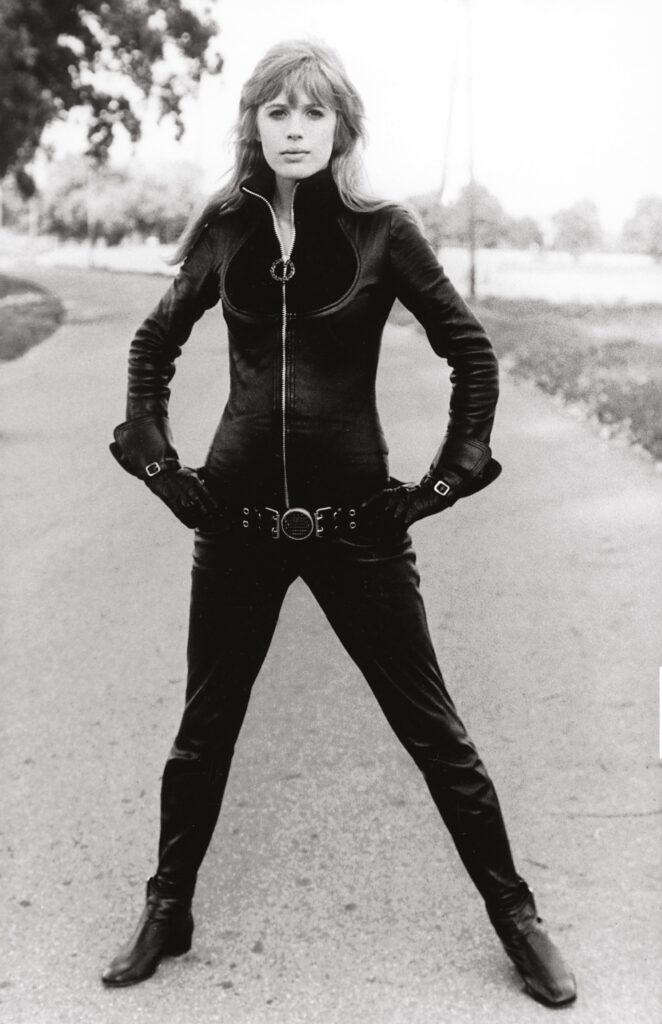

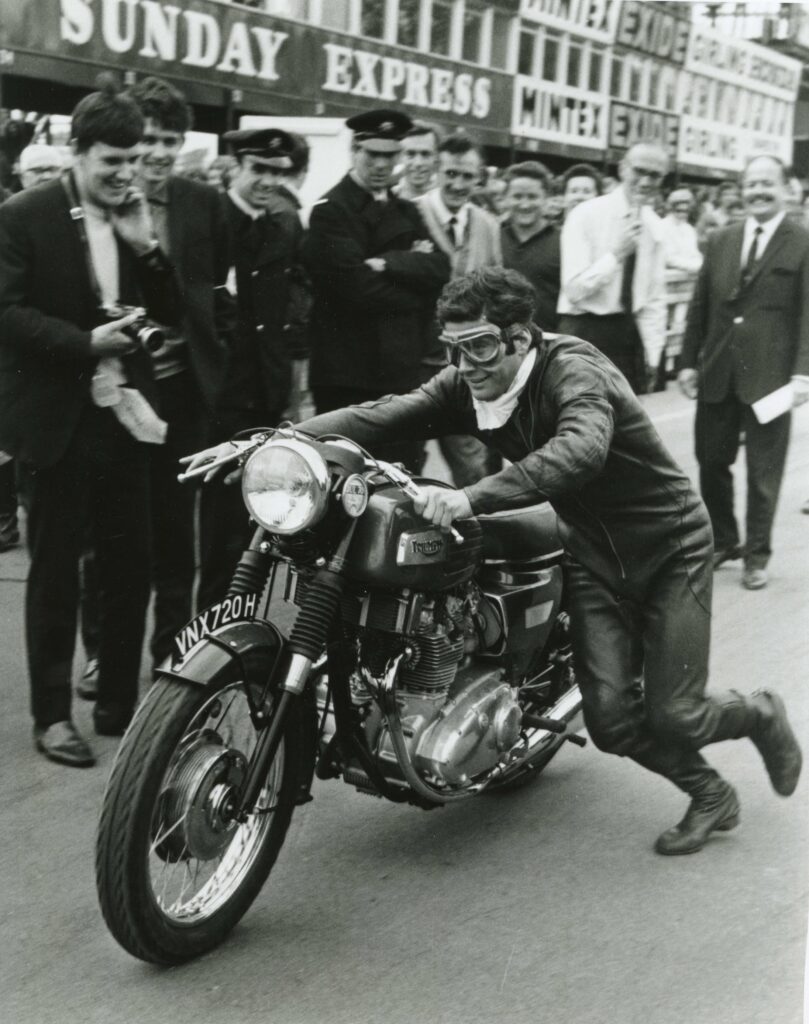

The Girl on a Motorcycle

The one-piece, zip-up leather racing suit has been the legal minimum standard for protective competition gear for over 60 years, but the question of who invented it has long been subject to debate. Movie-star handsome Geoff Duke made the outfit famous in 1951, racing and winning for Norton, after his local tailor, Frank Barker, sewed one up to Duke’s instruction. He’d already been wearing a one-piece fabric undergarment beneath his two-piece leathers, made up by a ballet specialist in London, which caused a few “ribald comments” from his team-mates. I’ll grant nobody else wore a ballet onesie while racing in 1949, but the Director of Veloce Ltd, Bertie Goodman, had been wearing his own one-piece leather suit a few years prior, while racing his family’s product – a Velocette KTT – at venues like the Ulster GP. Duke certainly knew who Bertie was, as a rare factory Director who actually raced motorcycles, so the idea was around, as they say.

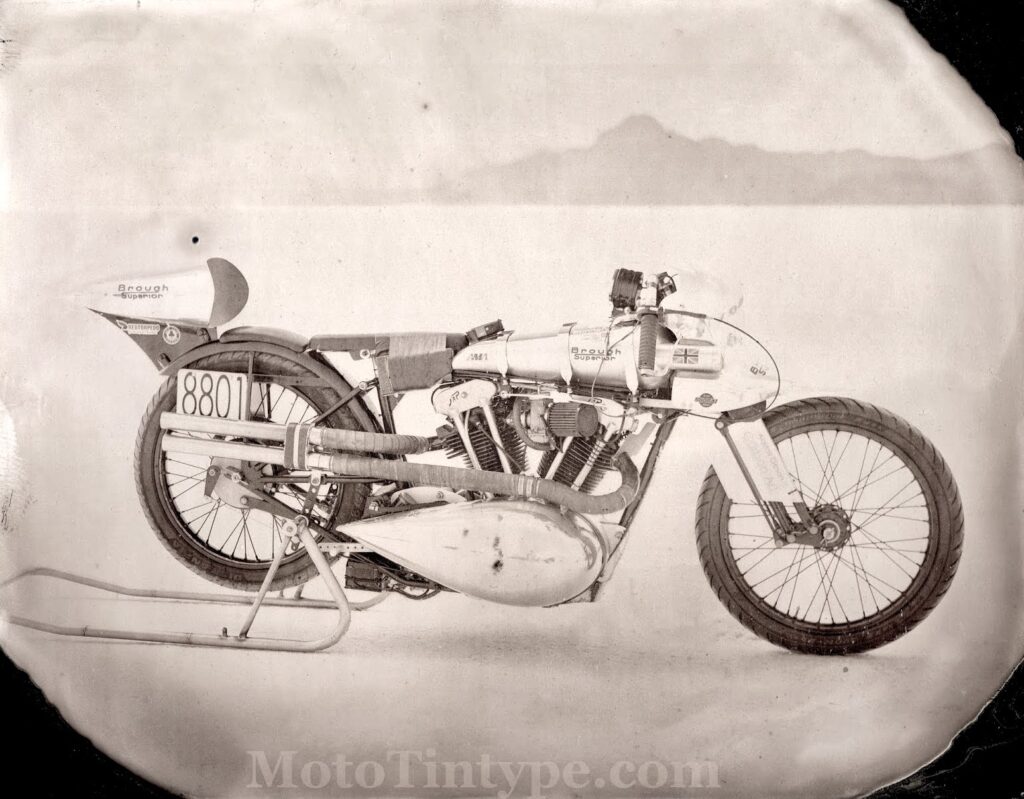

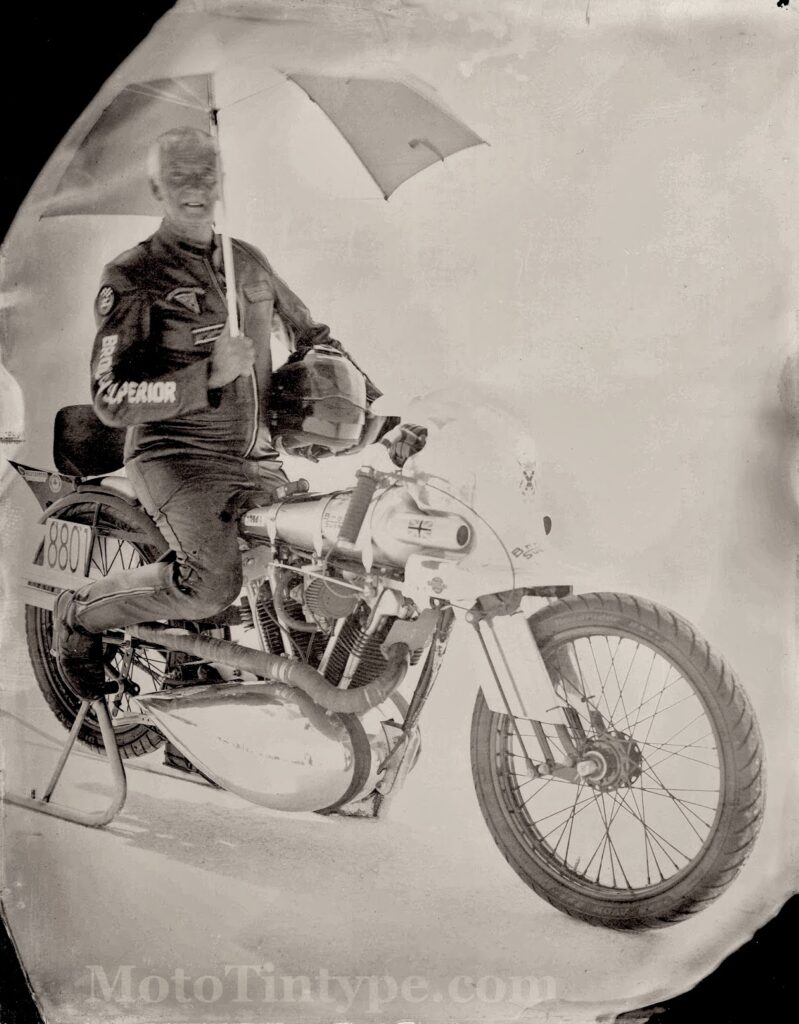

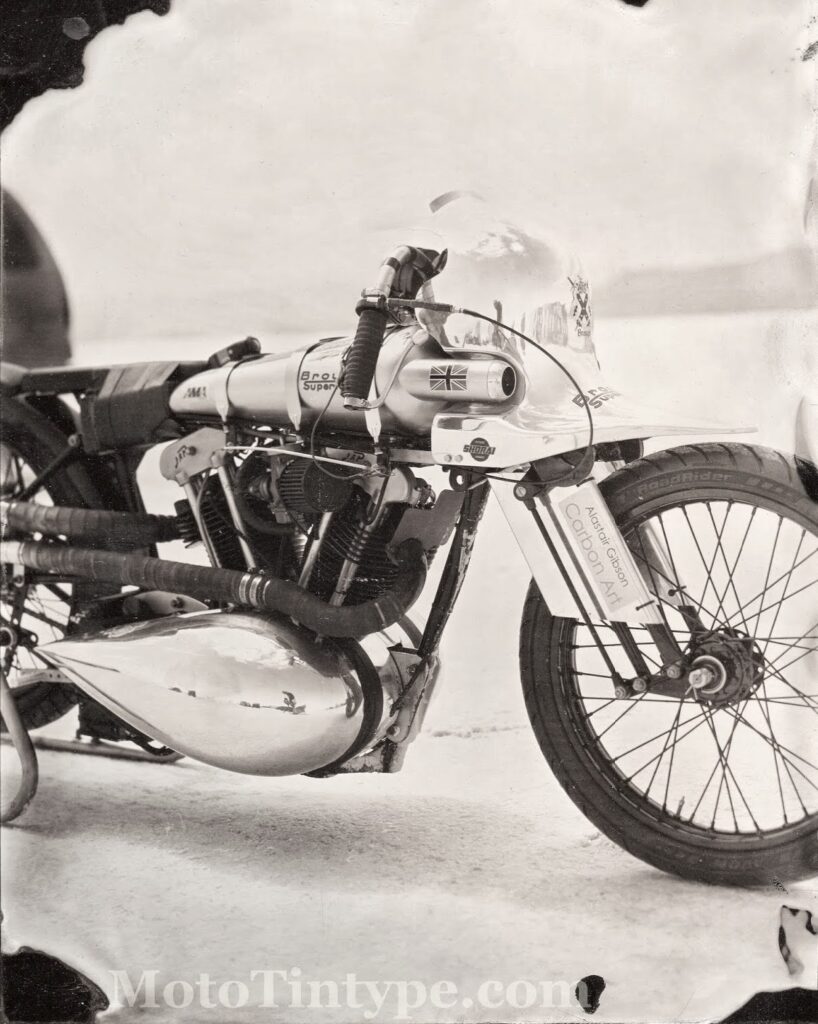

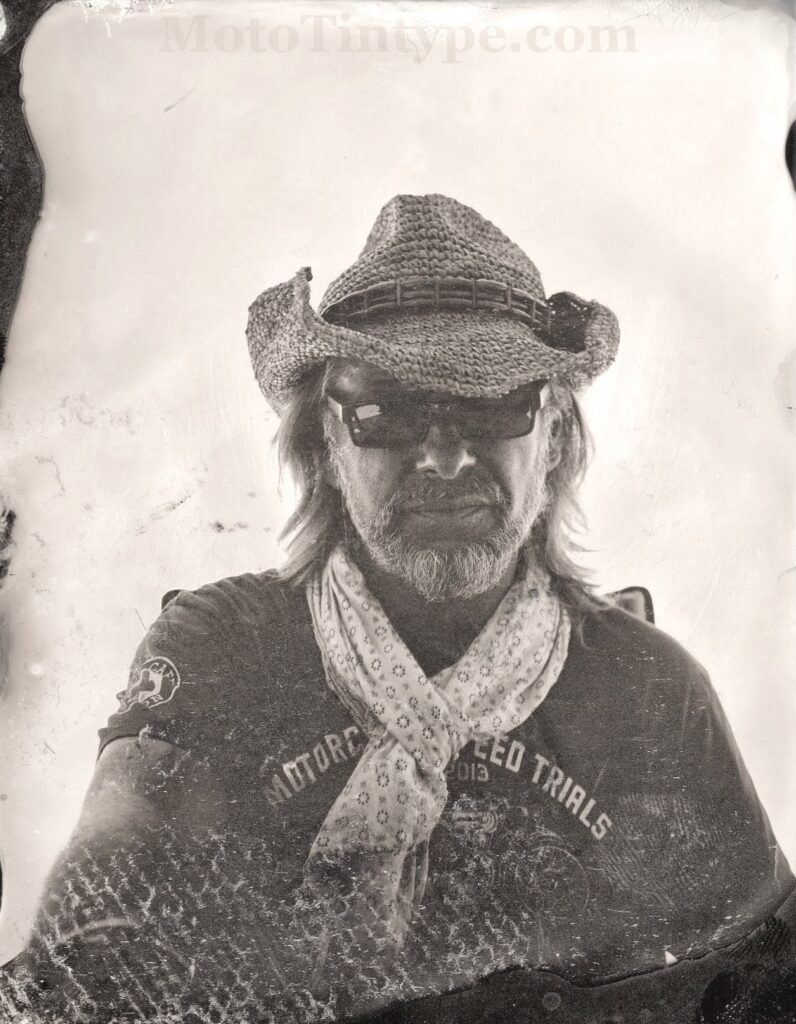

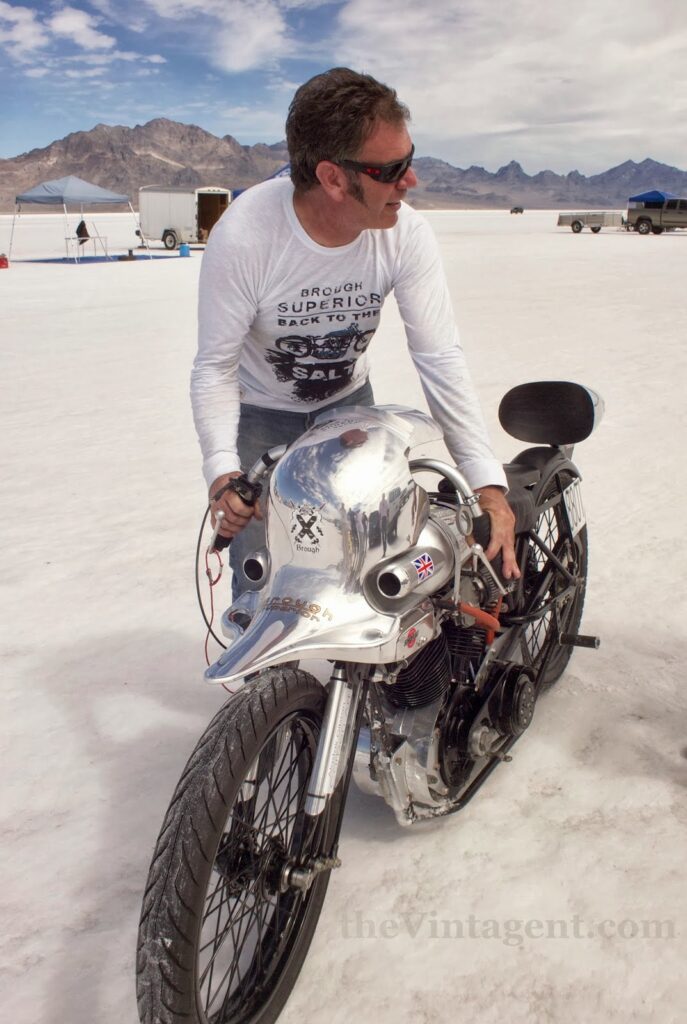

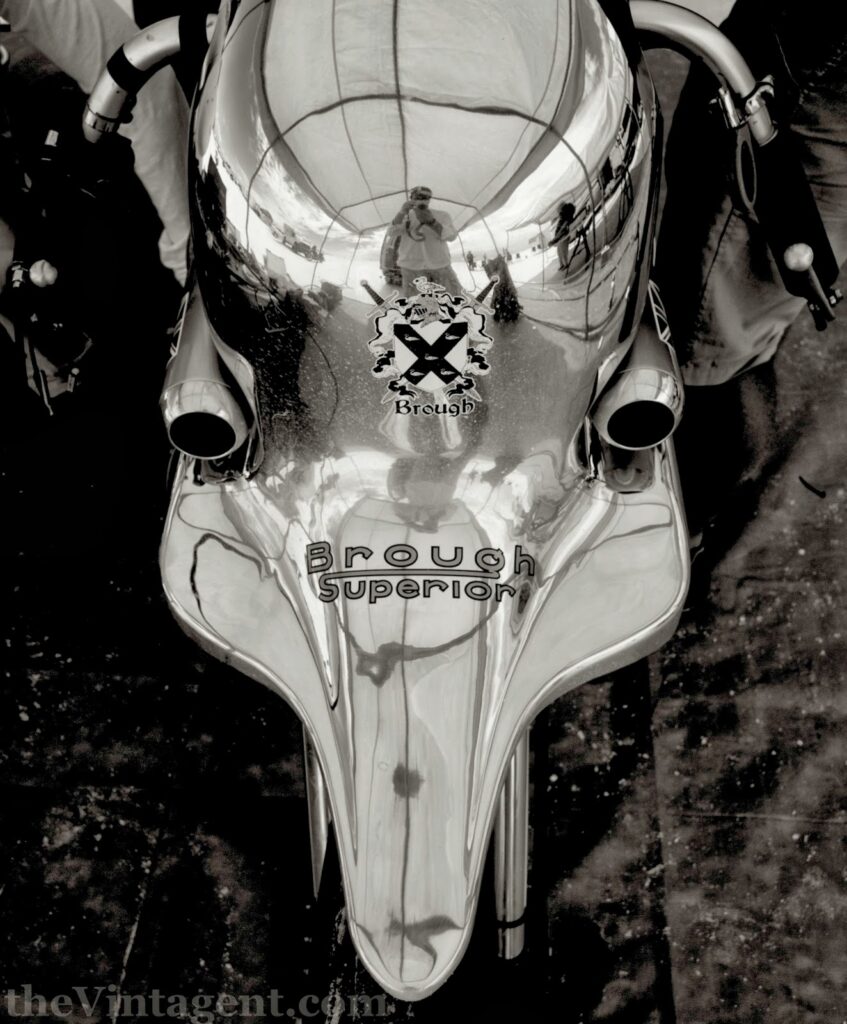

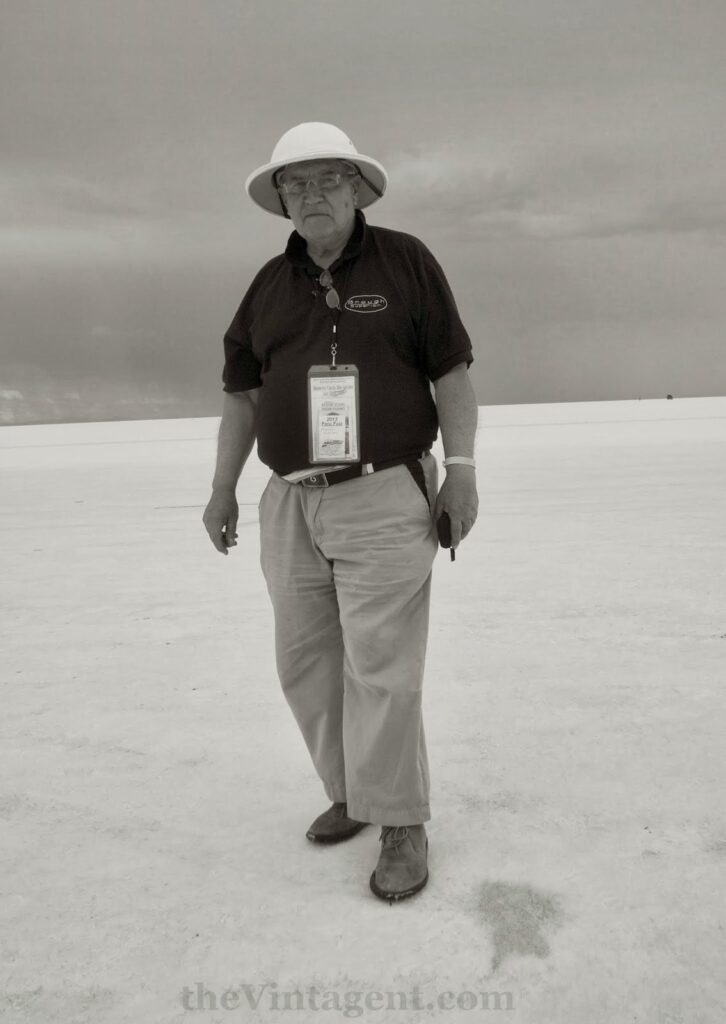

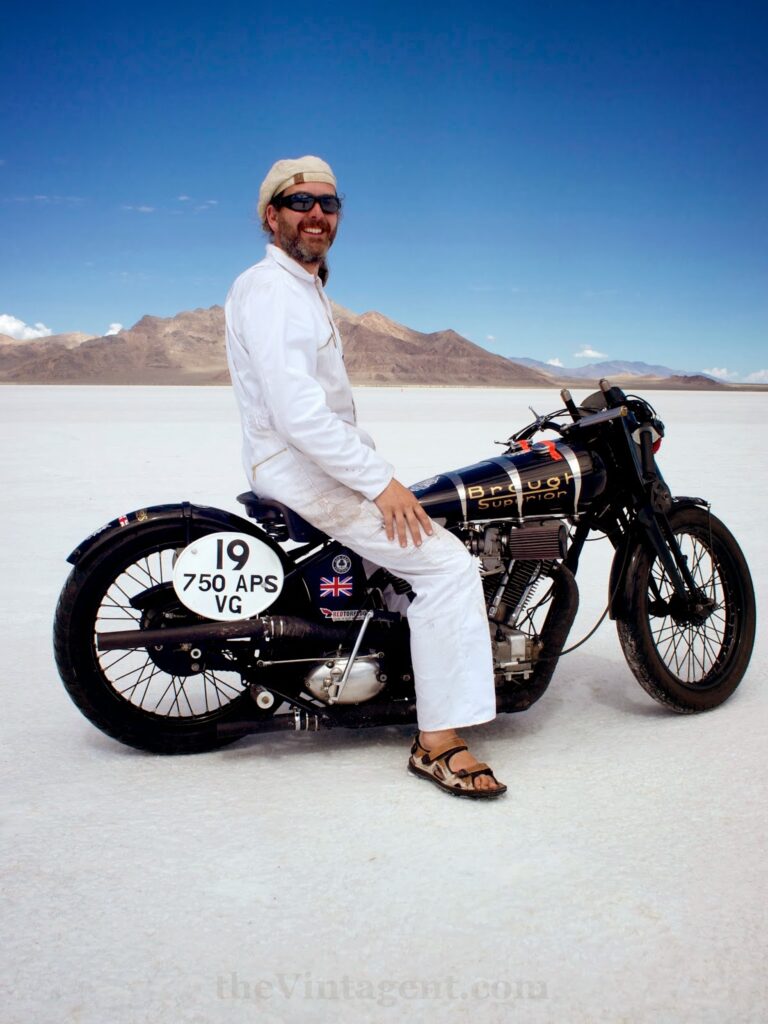

Brough Superior - Back to Bonneville (2013)

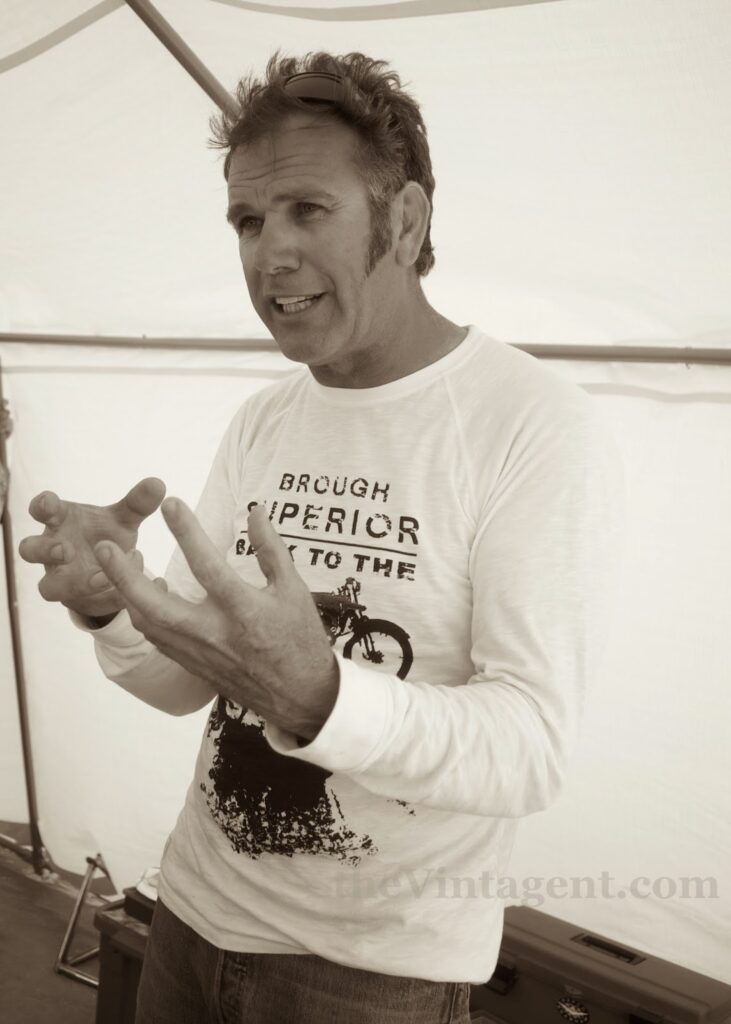

Mark Upham pocketed the deed to Brough Superior back in 2008, and for the first time in many decades, Things Are Happening with the magic old name. Upham has sufficient charisma - plus, apparently, the cash - to have gathered a talented crew about him in wide satellitic orbit, as near as the fortress-stone Austrian farmhouse he calls home, and as far as racetrack workshops in California. Whether you're a fan or not (and as he said to me last week, 'Not everyone loves me, Paul'), one must give credit to the man for raising the visibility of the Brough marque out of its comfy post-production wall-niche, where it lay dormant, velvet-cosseted and expensive. Brough Superior's deeply lacquered reputation - established by George Brough's ad-man bluster, and snowballing ever since - has become a blanket thick enough to protect the investments Broughs have become. Those of us who've owned the things know them to be actual motorcycles, with 'particular characteristics' one just might call (whisper it) flaws.

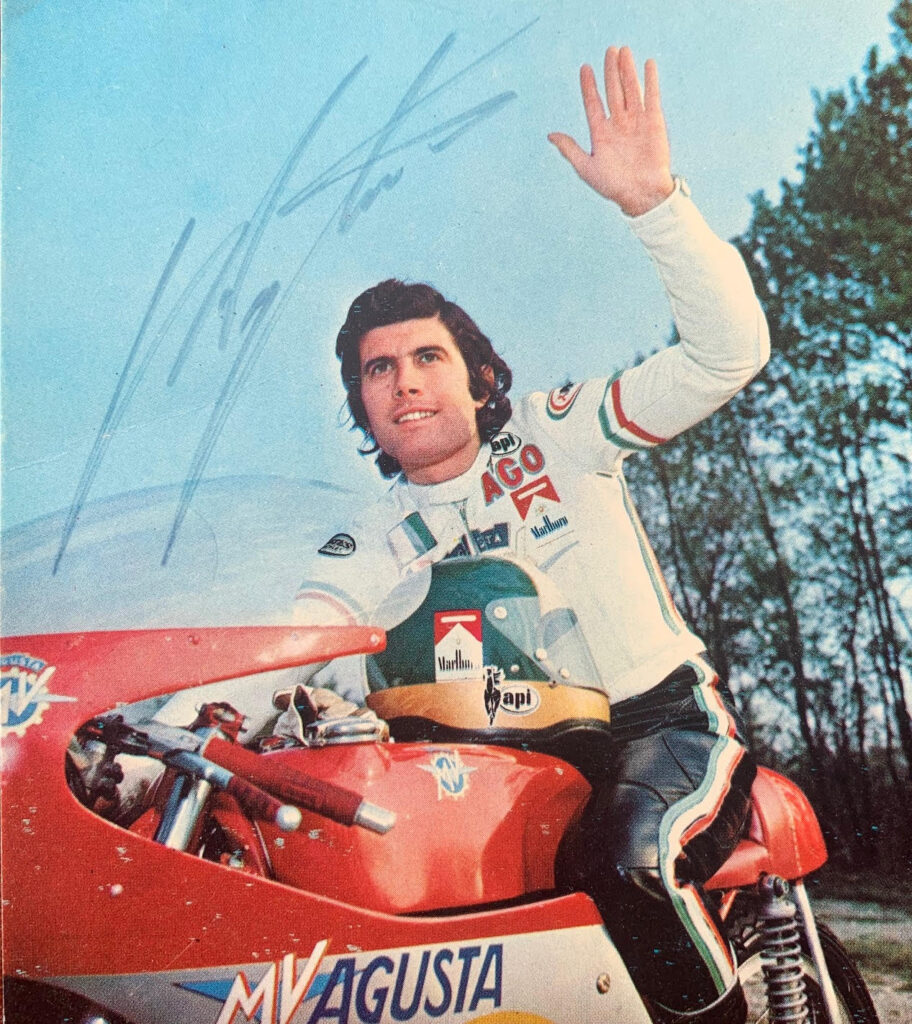

The Motorcycle Portraits: Giacomo Agostini

The Motorcycle Portraits is a project by photographer/filmmaker David Goldman, who travels the world making documentaries, and takes time out to interview interesting people in the motorcycle scene, wherever he might be. The result is a single exemplary photo, a geolocation of his subject, and a transcribed interview. The audio of his interviews can be found on The Motorcycle Portraits website.

The following Motorcycle Portraits session is with Giacomo Agostini, 15 times Grand Prix World Champion motorcycle racer and a legend of the sport, who is thankfully still with us, unlike many of his contemporaries in the dangerous years of GP racing - the 1960s and '70s - as motorcycles became incredibly fast but safety equipment and track safety design was stuck in the 1930s. Agostini was a guest of Team Obsolete in Brooklyn for their annual holiday celebration, and David Goldman took the opportunity to photograph and interview him.

Who are you?

I am Giacomo Agostini. I have won 15 World Championships with motorbikes, and I am in Brooklyn.

How did you get started with motorcycles?

When I was a bambino - a child - I thought about motorcycles. I don't know why! Also my family had nothing to do with motorcycles, but I loved motorcycles. Sometimes my father said 'danger', and 'you must go to school,' and he said 'no'. I said 'Papa I want to race, I want to race with the bike. Not with the car but with the bike.' So I started to love the motorcycle just when I am six or seven years old. For me it was a difficult subject to raise because my family didn't want me to ride, so I pushed a lot on my father. And my father said 'no, I won't sign the permission.' But later, a lawyer convinced my father to give me the permission to do the sport. Because the lawyer understood I just wanted to race motorcycles. And once I had the permission I started to race.

My first race was in 1962 and it was my first victory. I won with a Morini Sette Bello, it was a factory bike from Milan, and my main mechanic we called Boulangero because he was a baker - he didn't know how to change the spark plugs! And this is a very nice memory, because I went with my bike with no mechanics, and when I returned in the evening I was very happy because I beat a lot of riders with the factory bike. I cannot forget this because it was alive, my first love. Your first love you will never never forget, my memory will carry on.

Tell us a story that could only happen with motorcycles?

I don't think I have only one... no, I have three. One is when I went to my first race, as I said before, and I never forget because you know we never forget the first love. The second of course was when I won with MV Agusta my first World Championship in Monza. Monza is very close to my home town, and they had 150,000 people come to the track, but I didn't realize in that evening. Monday morning when I woke up and I read the the newspaper I understood I had won the World Championship. I cried a little because I was hoping for that from when I started to race, sure, but also from when I was a child.

The third one is when I when I changed from MV Agusta and decided to race for Yamaha. It was a very difficult decision, because my second family was MV Agusta. I went to Japan to try the two- stroke bike, after I was used to racing with a four-stroke. My first race was at Daytona: when I arrived in Daytona I was very surprised - the circuit is fantastic. And there were a lot of good American riders, and with the 700 I won the race. My first time in America, and this I will never forget because some people said 'now he's changed from four-stroke MV Agusta to Yamaha, and maybe he never wins'. But I did win that first race, and after that I also won the World Champion with Yamaha. The story is very nice. I cannot forget.

What do motorcycles mean to you?

The motorcycle for me is a love. I love motorcycles.

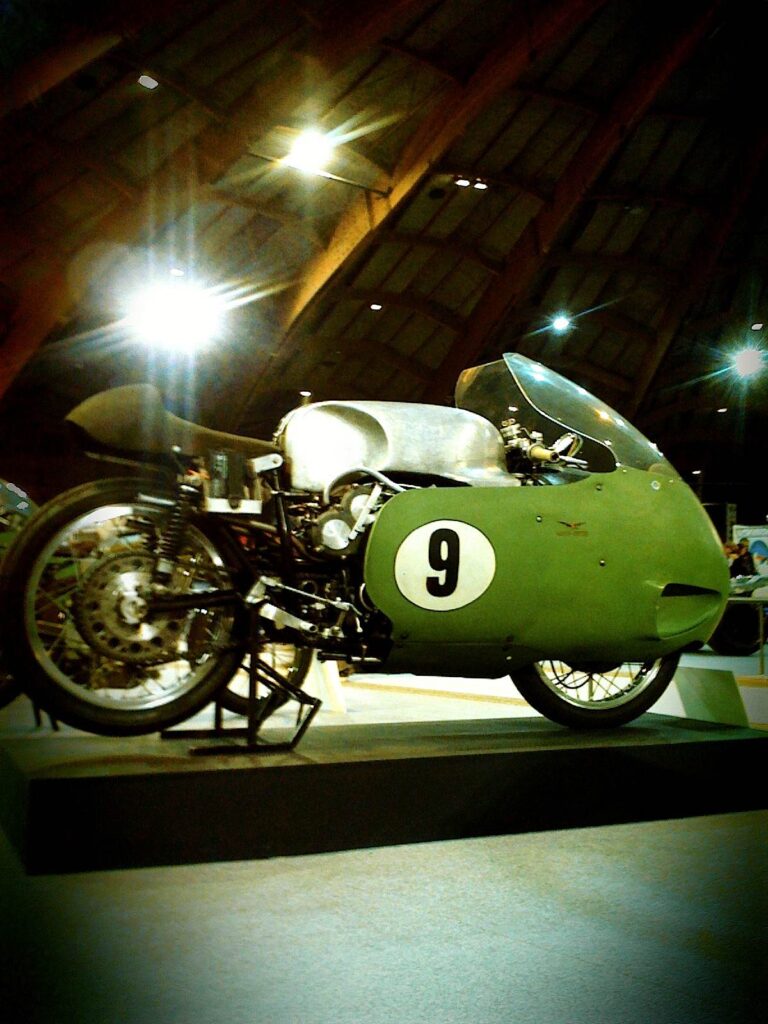

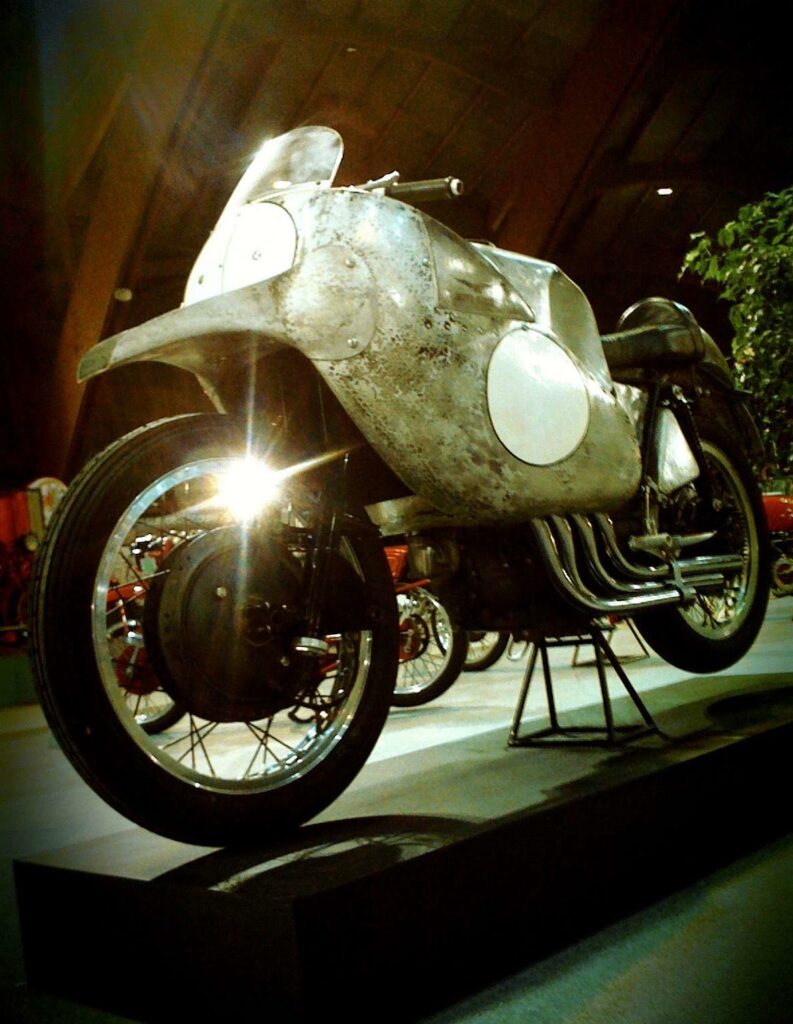

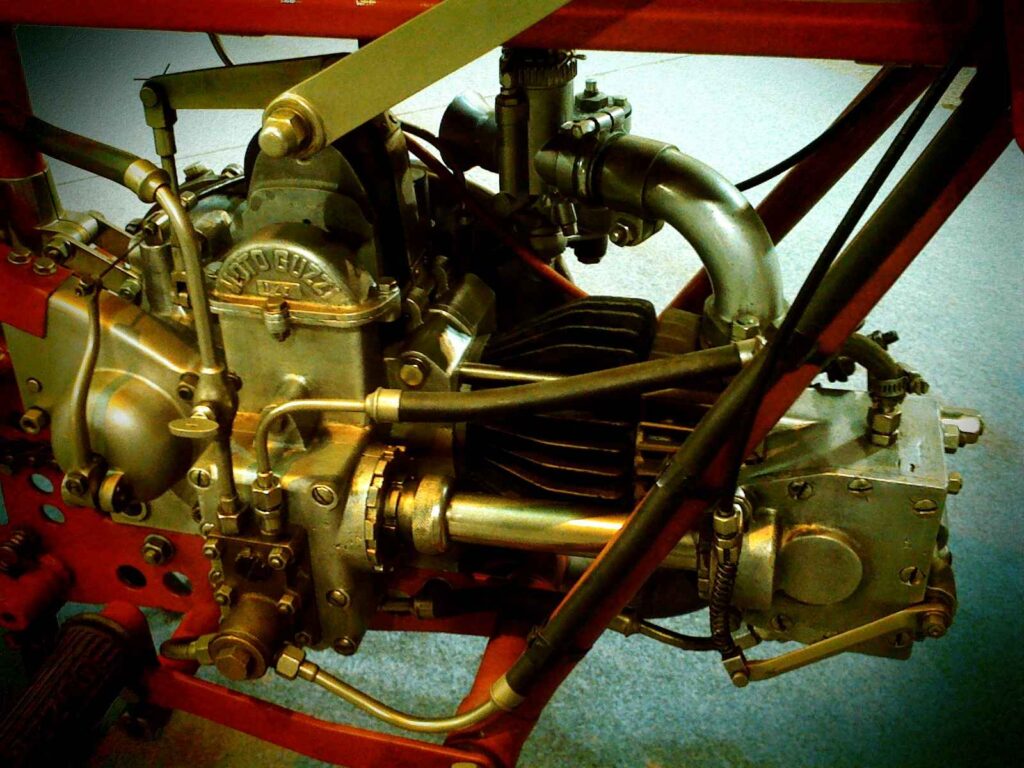

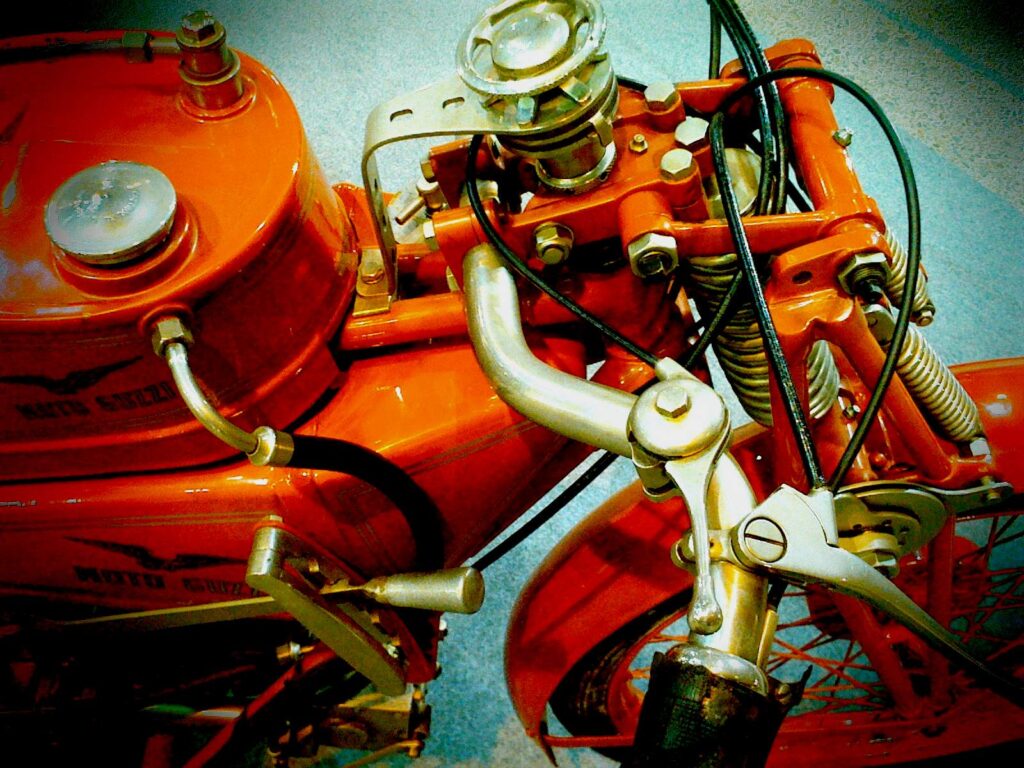

Adventures in Guzziland

The Avignon Motor Festival celebrates all powered vehicles, and is an understated, still-growing event, run over 3 days, with around 50,000 visitors. Tanks, cars, boats, planes, trucks, tractors, farm equipment, and motorcycles; this year (Ed- this was 2011) with a beyond-killer display of Moto Guzzis, including precious factory Grand Prix machines from the Moto Guzzi Museum. Also included were production bikes from all years: a mouth-watering display of exotica from the 1920s-1950s. Enjoy these 'vintage' iPhone2 photos!