The Ride: Piyush and Nishanth - Avoid IT

Photos: Piyush Verma

Let's say you're a recently graduated mechanical engineer in India; the next step is a job in IT, right? But sometimes, motorcycles get in the way, and that's the case with Piyush Verma and Nishanth Patel of Bangalore, who decided they'd rather build motorcycles for a while, and see if there's a career in motorcycle design and/or photography for him. They'd got their feet wet building custom vehicles with 3 years running their own off-road racing team, entering the Baja SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) competition, run by SAE India. The 'Baja' is a worldwide inter-collegiate vehicle design competition, with over 140 entries annually for engineering students to build off-road racers, which are put through a variety of speed, agility, economy, and design tests.

"When college (KS Institute of Technology) ended, we had a placement period, and the only companies that came to recruit us were all IT-based. Even though we did get jobs, it wasn't something we wanted to do. So we decided, out of our love for handmade motorcycles to make a custom bike." Clearly, Verma and Patel are rebels, and better still, Patel had a Honda CBR 400 RR, which was in poor condition cosmetically, that he suggested they build as a project. "I was like, let's do it!"

"We wanted it to have a retro Endurance Racer look, in contrast the sharp-edgy bikes of today. We made a cardboard template and then made the entire fairing and seat from an aluminum sheet. The paint scheme is from a Rothmans Honda; we felt it best suited the character of the bike. The entire chassis was buffed for a mirror finish, including the swing arm. The bike has its original head lights, a freeflow exhaust and racing hoses and brake lines." Verma thinks this might be the first inline-4 Custom in India, since the Indian 'big-bike' market is dominated by Royal Enfields, which are the typical custom-fodder. "So that's our story for now, it's short since we just came into the field! Someday we'll hopefully make an epic build." As fans of vintage Endurance Racing, we'd say this is pretty epic already, and it's great to see young customizers branching out in India from their typical Bullet beginnings. We can't wait to see more from young builders like these!

The Ride: Revival Cycles Landspeeder

More ‘Henne’ than Hemi, but still the loudest bike in town

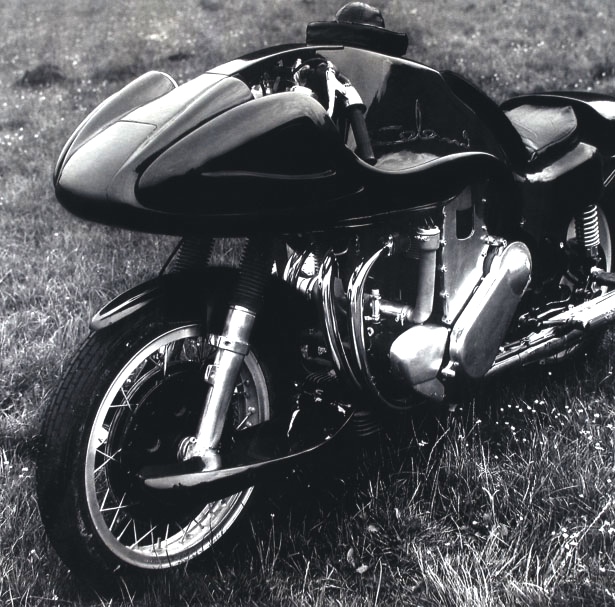

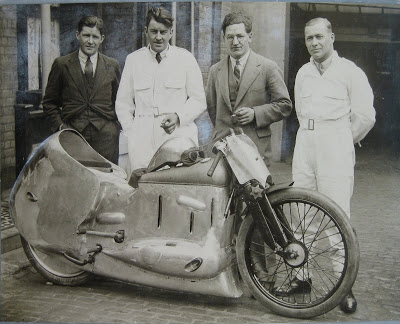

One benefit of trolling European bike shows is bumping into ex-factory race bikes hauled from the vaults. Munich’s BMW Museum was in a generous mood in 2013, and toured a pair of its crown jewels – Ernst Henne’s 1932 and 1937 Land Speed Record racers – to both the Concorso di Villa d’Este and its opposite, the Wheels+Waves festival in southern France. I’m a moto-judge at the Concorso, and crawled around that supercharged ’32 750cc LSR machine like a horny snail. In as-raced condition, it’s among the most beautiful wheeled vehicles ever built, with elegant shapes cladding brass-balls technical savvy. In Biarritz, it sat defiantly amidst a sea of Alt.Customs, which paled beside it. I bent the ear of any builder listening, wondering why nobody had taken inspiration from this, to escape the humdrum sameness of café racers and choppers. The next year, Japan’s Cherry+Co displayed a BMW RNineT homage to Henne’s bike in that very hall, with gorgeously updated sheetmetal and pinstriping; a work of inspired genius.

Alan Stulberg of Austin’s Revival Cycles also heard the siren call of that ’32 BMW at Wheels+Waves; the LSR bike paced in his imagination, and he grew obsessed. “Seeing that Henne bike was the seed, and I came home racking my brain - how could our team at Revival build something like this? But money is tight, we can’t afford to do it for ourselves. Then I was introduced to a Dallas collector who’s opening a gallery of motorcycles, who said ‘Let’s build what You want. Here’s my budget, what can you build for this?’” Such carte blanche saw Stulberg waffling between dreams - a Vincent custom or Henne throwback – and he ultimately tilted towards BMW for entirely practical reasons; “Our money’s better spent on labor than the starting material, and old BMWs are cheap.”

An internal issue nearly scuppered the plan, as Revival’s technical core – Stefan Hertel and Andy James, who’d nail down the technics and fabricate the thing - were opposed to building a bike for display only. Stulberg explains, “Our core ethic is functionality; that this wasn’t going to be ridden was a huge issue. I saw it as an opportunity for creative design, without the shackles of the street; not worrying legality meant we could spend more time on aesthetics. We argued about it for hours, but Stefan and Andy finally acquiesced… only because we decided to build two! One for racing and one for display. When we cut the sheet steel for the frame, we duplicated it for a second chassis.”

Revival’s flat steel chassis, while familiar to fans of pre-war BMWs, is a departure from the Henne bike, which actually uses a tube frame from a late ‘20s R63 under aerodynamic aluminum panels. The new bike is scaled up slightly, with the wheelbase a few inches longer, the frame a little taller, and while Henne’s forks were trailing links with leaf springing and a small friction damper, Stefan Hertel’s tech bent meant a modern upgrade for the front end. The original fork was stable enough for a 159.1mph record on the Frankfurt-Munich autobahn in 1936, but the ‘non-display’ Revival Landspeeder will handily top that (read to the end for why). Hertel designed a trailing-link fork with a longer pivot arm (and elegant ‘speed holes’), using a modern shock with a kinematic adjustable preload, plus a very steep fork angle combined with 6” of trail, as he feels steeper head angles handle better even at speed. Building that fork with contemporary performance expectations caused plenty of grief; “Stefan spent almost 6 weeks designing that front end; I walked in at 10pm one night and he was almost in tears. He was looking at the forks on a Max Hazan bike on his computer, and knew they couldn’t work at speed, but still said ‘look how elegant this thing is, but I have to make mine function at 150mph and last 50 years.’ I said it doesn’t have to be so elegant, but it does have to work. An hour later he was done. He was emotionally spent solving the technical problems, but he gets credit for how beautiful the bike turned out.”

The Landspeeder is indeed beautiful, and dramatic, and while conjuring the spirit of Henne’s racer, in construction it’s a completely different animal. The use of an inexpensive BMW 100/7 powerplant left plenty of space for Revival’s stamp, seen from the streamlined valve covers inward. Distinctive details include the quilt-padded knee indents, the faired-in handlebar, exhaust, and fork blades (all as per Henne), and that crazy trumpet air intake just behind the shifter knob, where the fuel tank normally sits. All the stainless hardware holding the front end and frame together is custom made – “no parts-bin cap nuts here”. The Landspeeder features ‘all black everything’ as the team omitted the distinctive pinstriping of the original; Henne’s body panels are hand-hammered and lumpy as a bag of lemons, but Andy James had the luxury of time for a perfect fit and finish, and those purposeful, Deco-streamline shapes need no accent.

It’s an onerous task for a designer to update a legend, made still harder today with internet trolls lurking under every comment box, pikes and torches at the ready. Stulberg was plenty nervous when Revival’s Landspeeder debuted on BikeExif, as it’s by far the most outrageous custom they’ve built. “I presented the bike as the truth, and the truth will save us. This bike wasn’t even meant to run, but it does; that was critical for us, and we shot a video blasting down the road. It’s so loud!” He needn’t have worried; the comments box was overwhelmingly positive, but more surprising was the interest from established collectors like Peter Nettesheim and the BMW factory itself. “That’s the best approval you can get - from the old school - it means more to me than all the dudes on the internet”.

In a few short years, Revival Cycles has moved smack into the middle of the moto-culture Renaissance. They build innovative Alt.Customs, travel the globe to ride their machines and support events, and host the increasingly important Handbuilt Show (April 20-22, 2018) in Austin. Much-shared photos of the Revival team wheelying their customs at drags and ice races tells the tale; their stuff works. And it had better; that second iteration of the Landspeeder will house a supercharged BMW HP2 motor, with near 200hp on tap, and should handily exceed Henne’s record on its Bonneville debut. Given Revival’s knack for gorgeous functionality, there’s little doubt we’ll be ogling a very fast black projectile in the near future, made even more appealing with a coat of high-speed salt spray.

[Words: Paul d'Orléans. Photos: Revival Cycles. This article originally appeared in Cycle World]

The Current: Eff You See Eye

The Outlaw Bicycle; a Streamlined Middle Finger to the Man

Motorcycles owe a huge debt to bicycles. The invention of the ‘Safety’ frame in the mid-1880s - the same basic chassis used on 99% of bicycles today – inspired builders to hang a motor inside, from their very first appearance. After experimenting with every possible engine location (even on the handlebars!), the issue was more or less settled by the ‘Noughts, with a motor down low in a safety frame. As the Century progressed, motorcycle frames got heavier and more specialized, eventually diverging from bicycle technology via pressed-steel monococques (from the late 1920s), beam-frames of wood, steel, or aluminum (all 1920s inventions), and double-loop frames like the Norton Featherbed (1950s).

Luigi Colani: The Future Is Now

A generation ago, we lost the Future. For over a century, a better, more functional, more equitable, and technologically cooler place was tantalizingly just out of reach, but certain to become today, soon. Snapshots of the Future arrived as drawings and models created by designers and artists in tune with the new, and beyond the new to the currently impossible. Anything we could dream was possible, and it was just a matter of time before it became everyday.

The recent Age of Irony took a scant view of the Future's unbridled optimism; forward-looking, visionary projects, from architecture and urban planning to product and technology design, had shown a fundamental flaw in the Future, a deep contradiction within its gleaming heart; the Future was not for everyone. Or, if it was planned for everyone, these envisioned socialist utopias smelled totalitarian, and had proved, when actually built, to be failures on a grand scale.

The tall housing projects with surrounding parkland, so geometrically beautiful in Le Corbusier's 'Plan Voisin for Paris', had been built on a smaller scale in New York and Paris, and by the 1970s had become dangerous slums. Critic Jane Jacobs rightly assailed such out-of-touch and un-human urban planning, and her influential analysis of what makes cities healthy was groin-kick to Future planning. Whether homespun like Frank Lloyd Wright, socialist like Corbusier, or outright fascist like Antonio Sant'Elia, rigorous urban planning looked bitterly dystopian by the 1980s - we had seen the Future; it wore jackboots, and didn't age well.

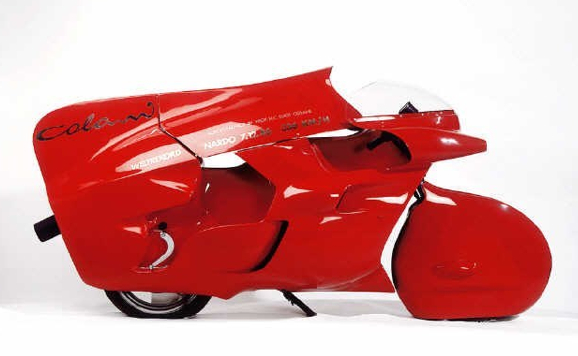

Luigi Colani is an old-school future-dreamer, the type of hyperconfident character whom skeptics disregarded during the ironic 1980s. His career as an industrial designer began in 1953, at the special projects division of McDonnell-Douglas aircraft, after studying aerodynamics at the Collége de Sorbonne. During the late 1950s and early 60s, he worked with several Italian auto makers (Fiat, Alfa Romeo, etc), creating special bodies and winning design awards.

By the 1970s he was famous for his increasingly outrageous organic shapes, which he calls 'biodynamic', in imitation of Nature's graceful forms, and designed products ranging from tea sets and cutlery to heavy articulated trucks and aircraft. “Soft shapes follow us through life. Nature does not make angles. Hips and bellies and breasts — all the best designers have to do with erotic shapes and fluidity of form.”

Feeling underappreciated in Europe, he relocated to Japan in 1982, and flourished, producing both 'improbable' designs for vehicles, and very up-to-date products, including the first 'ear buds' for Sony (1989...long before the iPod), and the first ergonomic body for a camera (the Canon T90 of '86), along with uniforms for SwissAir and the German police. Among his many transportation projects, Colani has long dabbled with motorcycle design, from sculptural shape-studies to creative bodywork over incredible machines, most notably the Münch Mammut and Egli-Kawasaki - an incredible turbocharged fire-breather with 320hp, which set the 10km flying-start speed record in 1986.

Colani doesn't consider himself a designer; “I am a three-dimensional philosopher of the future.” With the necessary combination of third-person egotism and unbridled imagination, Colani developed from an industrial design innovator to a full-blown psychedelic guru of flowing organic shapes for every application. While he sounds ripe for ironist derision, Colani's work is enjoying a resurgence after a long period of embarrassed silence from industrial designers.

After decades of developing, envisioning, and championing flowing organic shapes, the Future has finally caught up with Colani, and he is enjoying another day in the sun. The practical development of computer 3D modeling, and more recently the rise of rapid prototyping systems, has given 'Colani's children' - Zaha Hadid, Ross Lovegrove, and the new generation of organic-shape disciples - the kind of real-world relevance unthinkable in the 1960s and 70s, when Colani's work seemed utterly fanciful, even self-indulgent. Now superwealthy backers and attention-hungry governments actually build structures which seemed impossible a mere 20 years ago. Colani's future has arrived.

Project Desert Rat

Words and Photos: Paul d'Orléans

It sounds like the start of a good yarn; two friends haul their crappy old Triumphs to southern Utah for some canyon-hopping. While it turned out to be a very good boys-on-Triumphs story, it had an inauspicious beginning. I'd only ridden my 1973 Triumph TR5T ‘Adventurer’ on paved roads, and don't consider myself an off-road expert. But the canyonlands of Southern Utah are my favorite places to ride, being geologically unique and breath-takingly beautiful. I'd long yearned to explore the region's secrets away from the highways, poking into the canyons on the dirt roads tantalizing my curiosity on every map. My pal Conrad, a native of Canterbury, England, had a similarly limited off-road resumé, and had recently emigrated to the USA. To a newly arrived Brit, the lure of Southwest canyons was irresistible, so we hatched a plan to take the only dirt bikes we had - vintage Triumphs - to Utah.

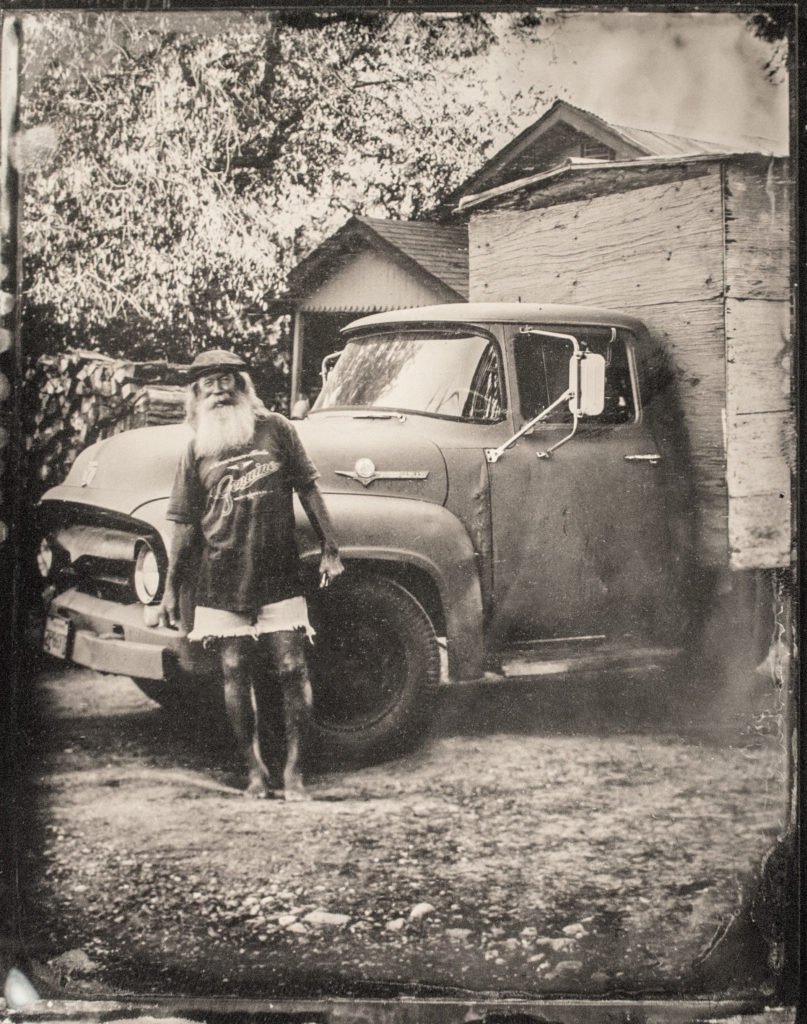

Well, Conrad didn't actually have a Triumph to hand. Earnest searching on Craigslist revealed a 1971 Triumph TR6R 3 hours away in Sonora, for only $1300, so the first part of our adventure was driving to the Foothills to meet Jeff Epps. Jeff turned out to be a true mountain man, living in a remote cabin he built himself, and in the manner of all owner-built domiciles, the shack was unfinished. The imposing 1953 Ford F150 truck with tiny cabin on its flatbed gave a clue to Jeff's relaxed building pace - he had a truly mobile home on site. The TR6 for sale stood next to a nice BSA B50, and looked good, although it was understood to need work, and was cheap, so we did the deal. Unfortunately, looking good and actually being good are very different; the Bonneville engine was knackered, and our Utah dreams faded. Fortunately, we found another motor in San Francisco, powering a fairly awful bob-job. Suddenly Conrad was 2 bikes deep, so we swapped their motors, and voila, a week later we were ready to roll with his '69/'71 desert sled.

Our next stop was the Bonneville Salt Flats, where nothing happens in mid-October; Speed Week is long over and the place is deserted, but if you like solitude, and to ride any speed in any direction for as long as you like, there's no place like it. We did all that, and explored the borders of the lake too, which takes a surprisingly long time to reach. There's no gauging distance with no features in the middle ground, and the lake ranges from 20-40 miles wide at spots. We were tempted to head up the dirt trails in the bordering mountains, as we'd heard there are caves with petroglyphs in the area, and evidence of human habitation 10,000 years ago, when Lake Bonneville was a hundred feet deep, and enormous.

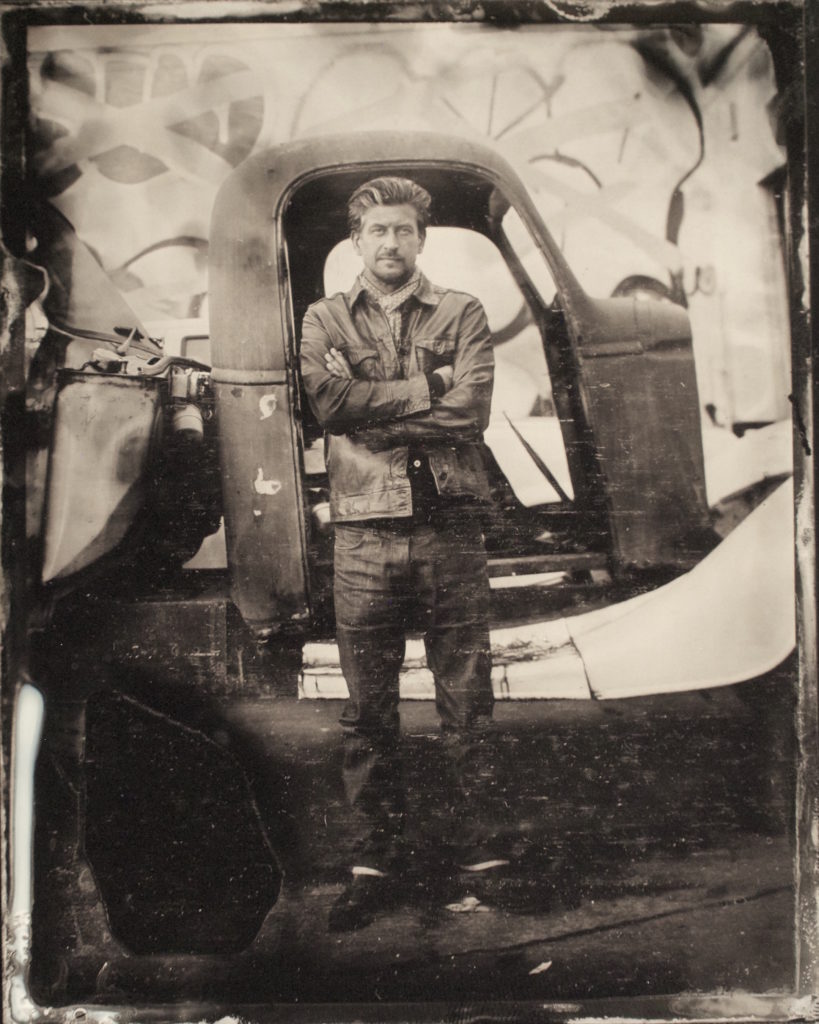

Springville, Utah, is 5 hours from Bonneville, and the site of Jeff Decker’s Hippodrome Studio, with his Crocker and Harley-Davidson racers, Miller track car, and collection of Biker memorabilia. Jeff was inspired to shoot Wet Plates in the old ghost town of Eureka, so we headed into the desert, where Google Maps instructed us to a dirt road shortcut to Eureka. We bumped over a deteriorating, shrinking, rutted cow trail with deep ravines and dry stream beds, until we got stuck. Then 3 city boys in our ‘workwear’ dug big rocks out of the dirt with our bare hands, jacked up the truck, and made a path out with sticks and stones…we survived to shoot photos at Eureka.

Always listen to the locals; South Draw Road is a challenging mix of stream crossings, soft red powder, deep rock-lined gulleys, and steep climbs up rock staircases. It also threads several red-rock canyons, follows a beautiful stream to its 9500' high source, and traverses grassy high-altitude meadows that beckon a traveler to stop and look. It took all of our motorcycling experience to navigate the treacherous path without coming to grief, or damaging our road-going 1970's Triumphs. We passed exactly one vehicle in 80 miles; a Jeep struggling up a steep Devil’s staircase of flat sandstone slabs, which was strewn with loose square boulders. We asked if we could help, but they demurred, and we carried on, arriving at a grassy mesa surrounded by spectacular cliffs.

If we had tents, we would have slept in this beautiful place, but we had 40 more miles to go, it was already mid-afternoon, and we didn’t like the idea of dirt-riding by 6 volt headlamps. We were sometimes blinded by the low sun, and rode with one hand shielding our eyes, the other twisting the throttle and guiding our wheels through dirt gulleys separated by grass hillocks. By the time we left the red rocks and entered an Aspen forest, we'd climbed to over 10,000’, and soon joined little Hwy 12 at its summit, which already had snow in its hollows.

It was cold at the 10,000' summit of Hwy 12, so we rode directly, dirty and bike-rough, to the best restaurant in town, drank several margaritas each, and had a terrific dinner. We rode home by full moon and our pilot lights, as the serious pounding had broken both our main headlamp bulbs. In the moonlight we saw the shadows of deer running beside us, and were beat but elated at a memorable day's ride.

The next day we found Goosenecks Overlook, just outside Capitol Reef Park, a dirt road leading to a loose red shale landscape, and the fierce 600’ drop into Sulphur River canyon. Needless to say, the photos were dramatic, although the cliff's edge gave Conrad the heebie-jeebies, which meant only my TR5T made it to the edge of the cliff! The cliff's-edge photos make a compelling argument for 45-year old motorcycles; they're still competent in rough terrain, they're cheap and fun and easy to keep working, and provide a high ratio of smiles/mile. Why oh why don’t more people take their old bikes on adventures?

After the Goosenecks. we headed further outside Torrey to the Great Western Trail, which spurs off Hwy 24 due East into the mountains, and seems to have no end at all. It seemed, looking at the maps, that one could ride for days or weeks exploring the area in a single thread, camping in the vast wilderness stretching clear into Mexico, and beyond the border even, if one had the gumption and an idea of supplies. There are hundreds of dirt roads winding through the mountains and canyons of the Southwest, on their way to God knows where, or whose property or reservation, which is exactly their allure. One day, we told ourselves, one day.

The next day we drove to Bryce Canyon National Park, just ahead of the snows that reached Capitol Reef that day. Bryce Canyon itself is a weird pink wonderland, and while there are no roads inside their colorful hoodoo wonderland, there are plenty of dirt roads just outside the Park. We chose a road through Coyote mesa, where Conrad discovered that old Dunlop TT100 tires are really slippery over sandy roads, by launching himself sideways over a banked dirt corner. Remarkably, he didn’t crash, and we carried on exploring the best Utah had to offer. In our 4 days of intense off-road riding, nothing broke - not us or the bikes, which wore a caked mix of salt, red dirt, and sand. We power-washed every crevice of our Triumphs just before leaving Utah on our 2-day drive back to California, tired and happy, ready to do it all over again.

The Silent Types

Motorcycles and movies; it's been a winning combination since the dawn of cinema. The Silent era of the early 1900s-1920s relied on pantomime, title cards, and onscreen antics before spoken dialogue arrived with recorded sound, and 'special effects' were edited into scenes. Before 'talkies' became the norm, motorcycles in the real world were racing at over 100mph on board tracks, had circumnavigated the globe under adventurous riders, and played a role in the first global war, yet the big screen had yet to exploit them for anything but their kinetic potential. The motorcycle as a character in itself would have to wait until after WW2, as would the 'Dark Rider' trope - the motorcycle as a vehicle of/for menace - which first appeared as metaphor in Jean Cocteau's 'Orphée' (1950), and as reality in 'The Wild One' (1953).

Before the advent of special effects teams using models or double-exposures to mimic dangerous action, a surprising number of silent film actors performed their own stunts 'in-camera' - meaning the events were totally real, although very carefully planned. The premier example of the actor/stuntman was Buster Keaton, who can be seen riding a motorcycle from the handlebars, riding through fences, and making dangerous jumps across moving trucks between gaps in a bridge. It's still great stuff!

Keaton is widely considered the best physical comedian of the silent era, thinking up and executing his own elaborate stunts, and directing himself in wildly popular films during the 1920s. His po-faced expression, which subtly morphs from maudlin to curious to shocked, was a key to his comedy, being a total contrast with the outrageous antics in his films. Keaton included elaborate stunt riding on a 1923 Harley-Davidson 'J' model in the 1924 film 'Sherlock Jr,' which can be seen above. Another scene in 'Sherlock', featuring a moving train and water tower, actually fractured his neck vertebrae - but Keaton didn't realize it until he was x-rayed years later. He had an exceedingly long movie career, successfully making the transition to 'talkies' and then into television. His last film appearance was 'A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum' (1966), when he was 70 years old.

Larry Semon was another talented actor/director/stunt man, who's nearly forgotten these days, but in the 1920s he was a very successful and wealthy film producer. He directed the first, silent version of the 'Wizard of Oz' in 1925 (in which he played the Scarecrow), and worked with both Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, before they created their immortal comedy team. Semon directed and acted in the short 'two reel' film 'Kid Speed', about two auto racers (Semon and Hardy) competing for the same girl ('Lou duPoise', a reference to the duPont family). Semon was known for his elaborate/expensive sets, sometimes building fully functional houses for a film, as well as huge gags - in the case of 'Kid Speed', an entire mountainside slumps onto a road for comic effect. If you want to skip the slapstick and see the cool old racers, jump to the 14-minute mark.

'Kid Speed' is a two-reel film, shortened to 18 minutes; this may be the result of deterioration of the original, highly volatile nitrocellulose film stock. Semon died in 1928 of tuberculosis, and many of his films languished in private collections before being rescued and transferred to more stable 'Safety Film' stock - cellulose acetate, which is much less flammable. Note the words 'Safety Film' on your old 35mm Kodak negatives; previously they would have had 'Nitrate' in dark letters printed. Nitrocellulose is explosive, derived from 'guncotton' and related to smokeless gun powder, and was the foundation of the DuPont chemical fortune.

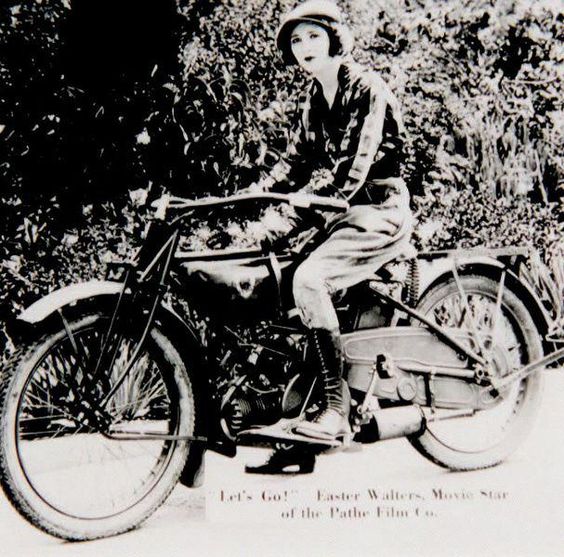

Some of the best motorcycle stunt riding in silent films was done by Easter Walters. She's the real star of this one-reel short 'Taken For a Ride', in which a Larry Seamon lookalike ('Bobby Emmett' - Robert Emmet Tansey) tries to impress a girl by stealing a 1922 Henderson DeLuxe with sidecar, with predictable results - his girlfriend knows more about the workings of a bike than her suitor. This short is a 'one reel' movie, ie the length of a spool of film; 12 minutes, and Walters is clearly capable of handling a motorcycle with verve. The publicity photos of her 'surfing' a 1919 Harley-Davidson Sport Twin are priceless!

Easter Walters is barely remembered today, but was born in 1894 in Iowa, and moved to Hollywood around 1918. She made some headway as an actress in the silent films ‘Common Clay’ (1919), ‘Hands Up!’ (1918) and ‘The Tiger’s Trail’ (1919). She was known for performing her own stunts, and was a fixture of Hollywood gossip sheets in the 'Teens for riding around town on her motorcycles - perhaps the Indian Model O pictured, and/or the Harley-Davidson Model J in other photos. 'Moving Picture World' in April 1919 ran an article titled ‘Breaking the Speed Laws is Sport for Easter Walters’. Sometime after 1920 she left the film industry; her final film was 'The Devil's Riddle' (1920), and she was married that year to Harry Kinch. She remained in Southern California the rest of her life, and died in San Diego in 1987.

Harold Lloyd was an actor/director on par with Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, and more financially successful than either. He kept control over his image and his films, refusing in later years to allow distribution of his work unless for a very high fee...which meant that by the 1950s and 60s, his work was slowly forgotten, unlike his rivals. In common with other directors of the 1920s, Lloyd found that motorcycles added to the kinetic appeal of a chase sequence. The three-cop pursuit of Lloyd - riding two Harley 'J's and a Henderson 4 - in the 1920 film 'Get Out and Get Under', is a zany early car chase sequence.

Competition between directors for public attention meant increasingly treacherous stunts, and stuntmen were often injured or killed in the era - it was all part of the job description, just as Board Track racers could expect a short career, and considered themselves lucky if they escaped without serious injury. Buster Keaton demonstrated how far stuntmen would go for a laugh in the '20s, while others did spectacular work as well. The following British Pathe film features stuntman Fred Osborne attempting a 25' leap over a cliff on a Henderson 4-cylinder, using a parachute to soften his landing. The parachute essentially fails to open, but Osborne amazingly survived the fall. It was a ridiculously dangerous stunt, and undoubtedly done for self-promotion, in the manner of Evel Knievel decades later. The Silent Types were a strong bunch.

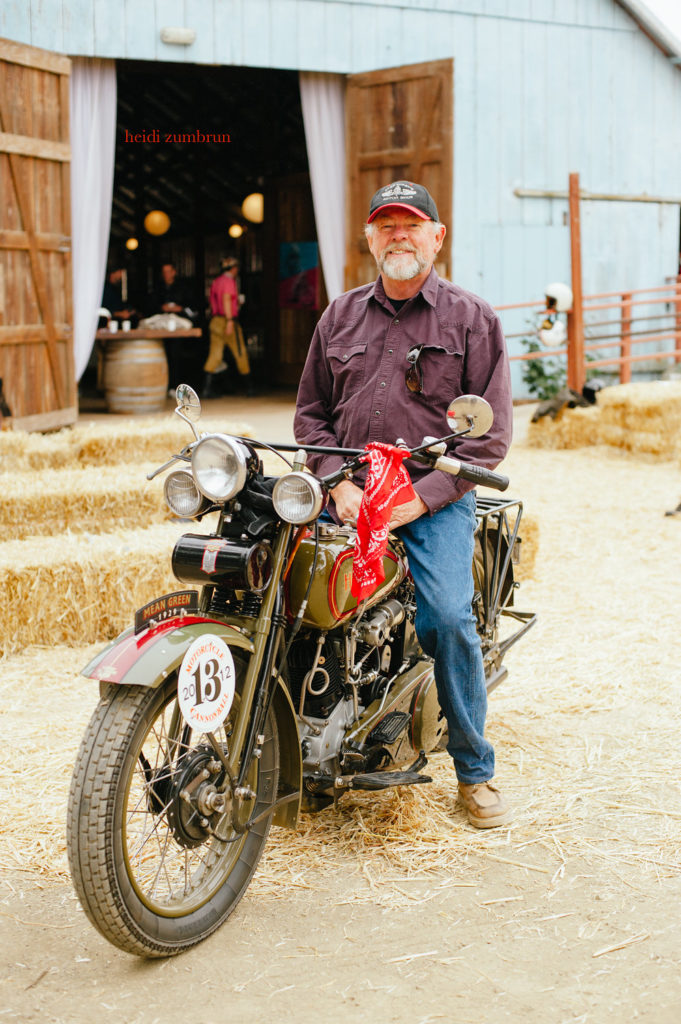

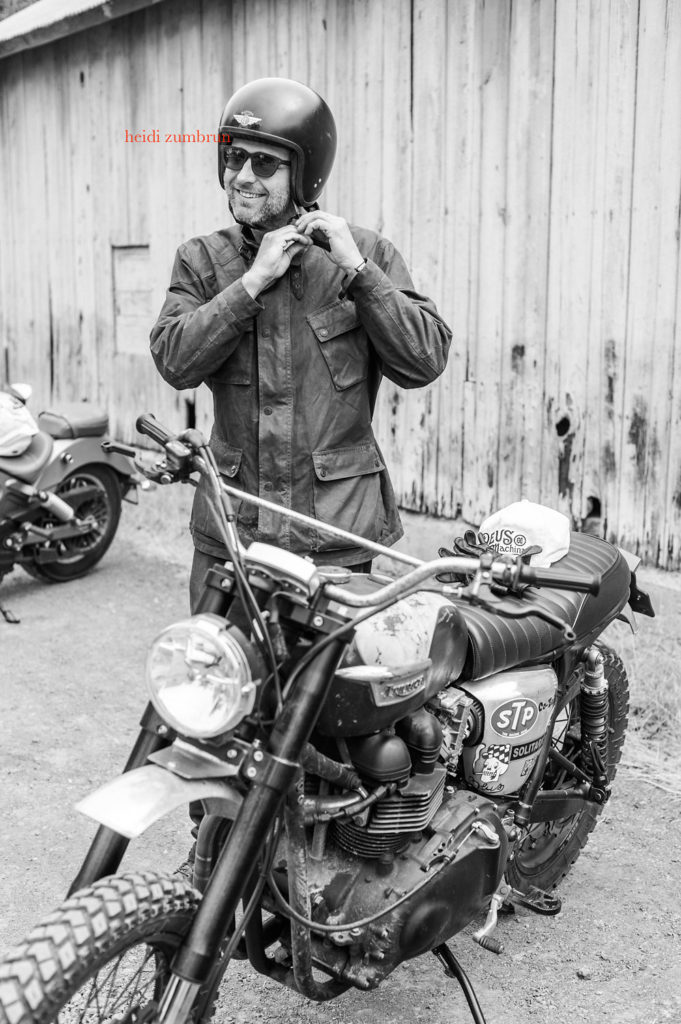

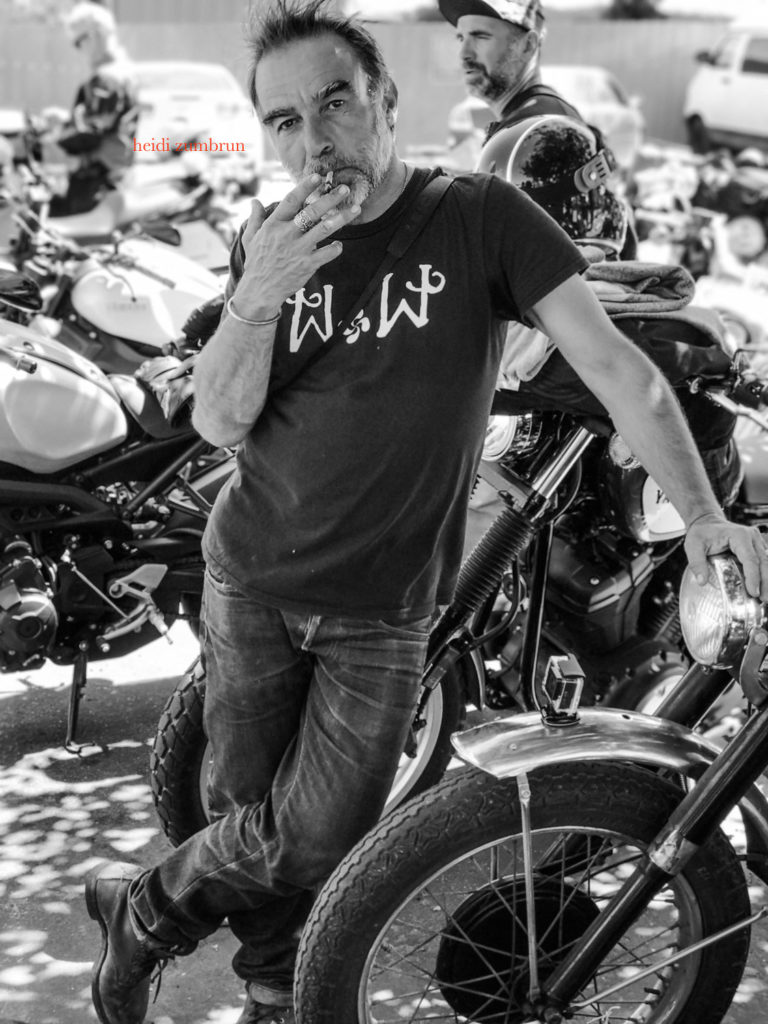

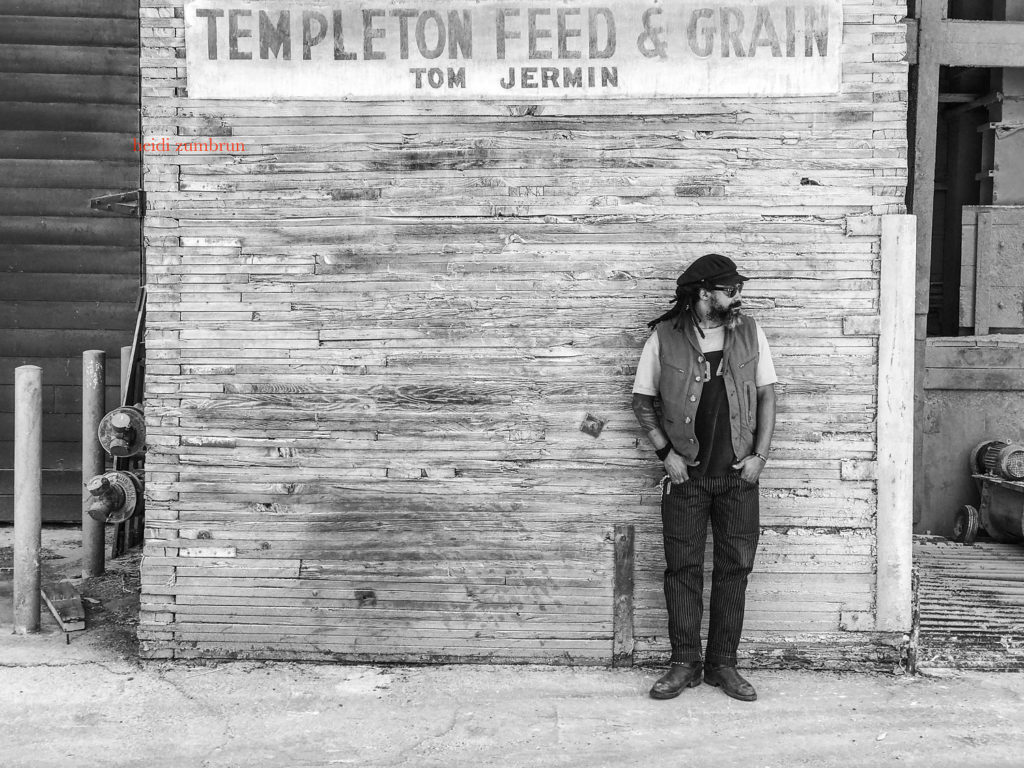

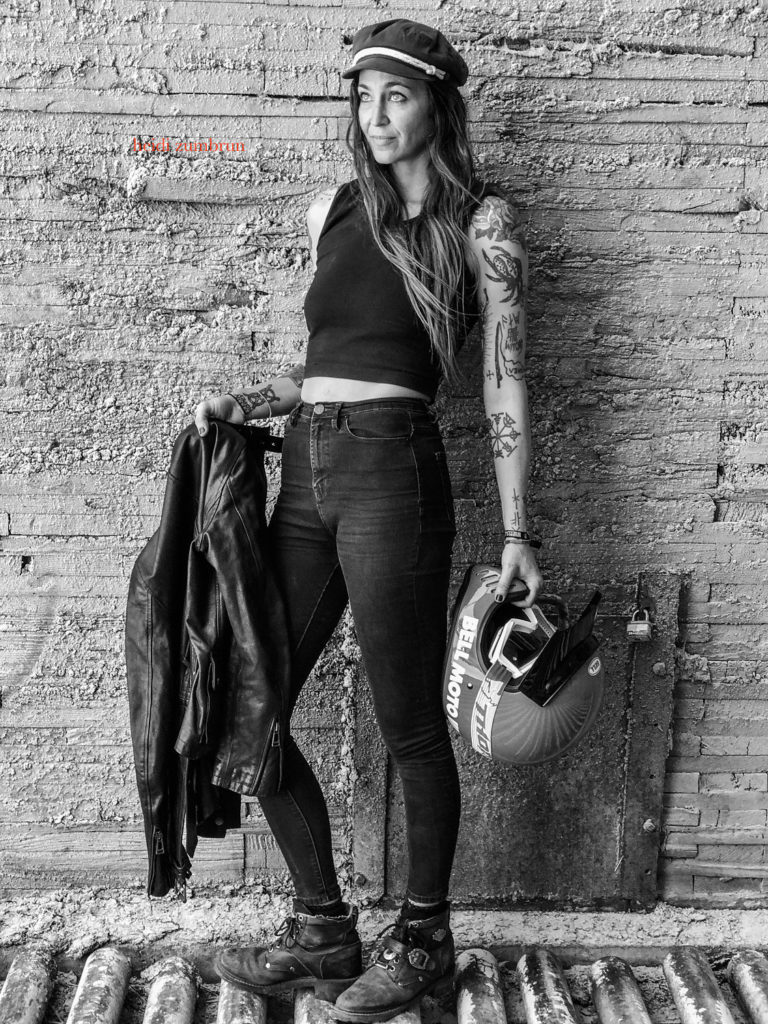

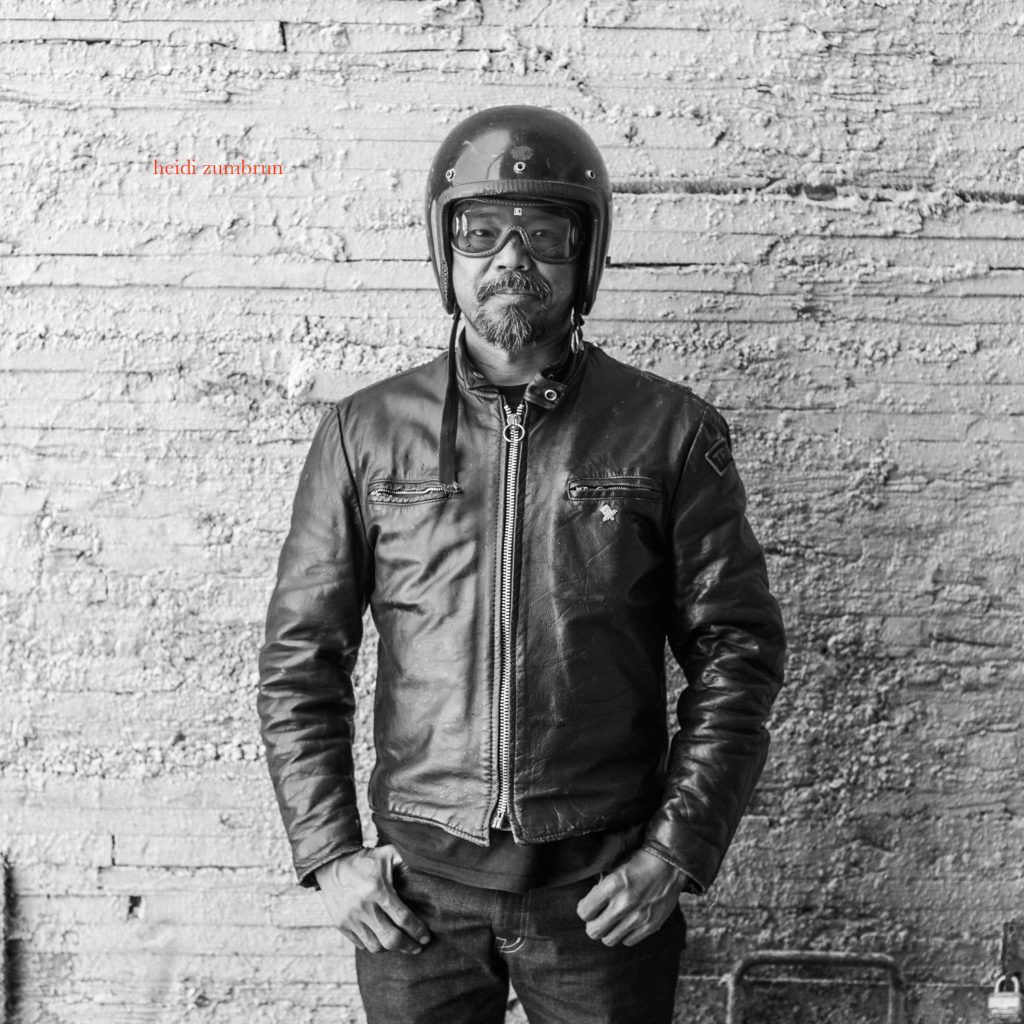

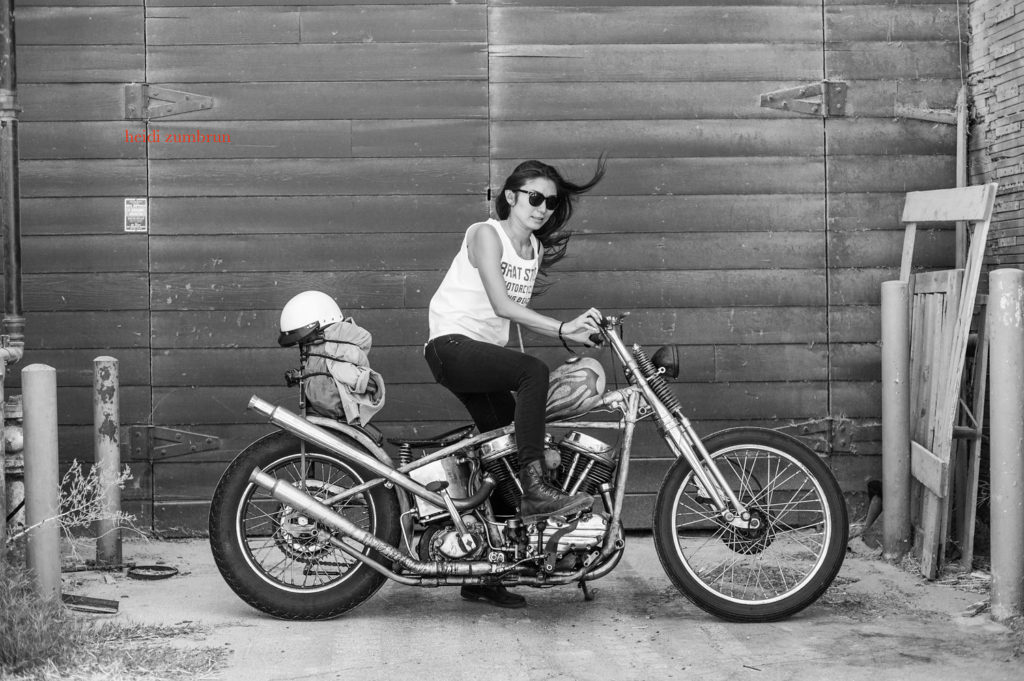

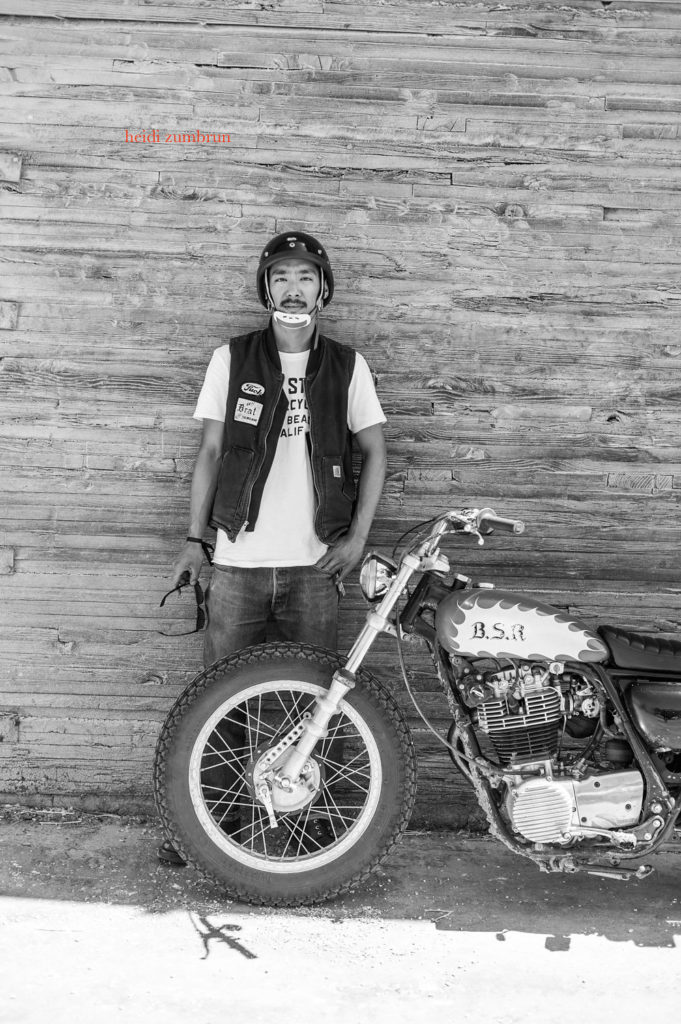

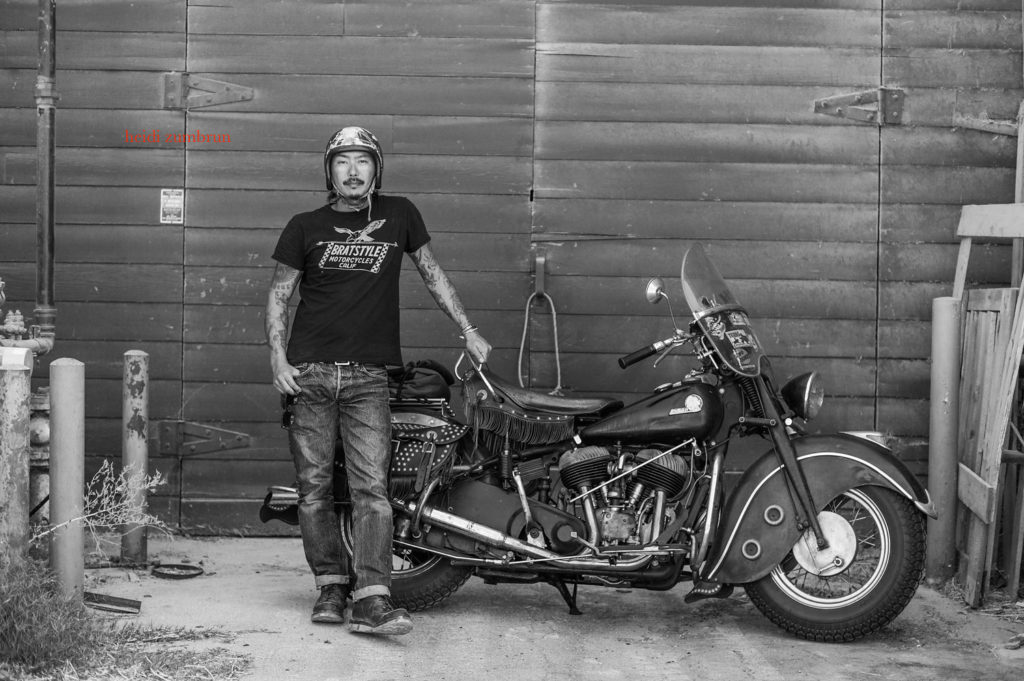

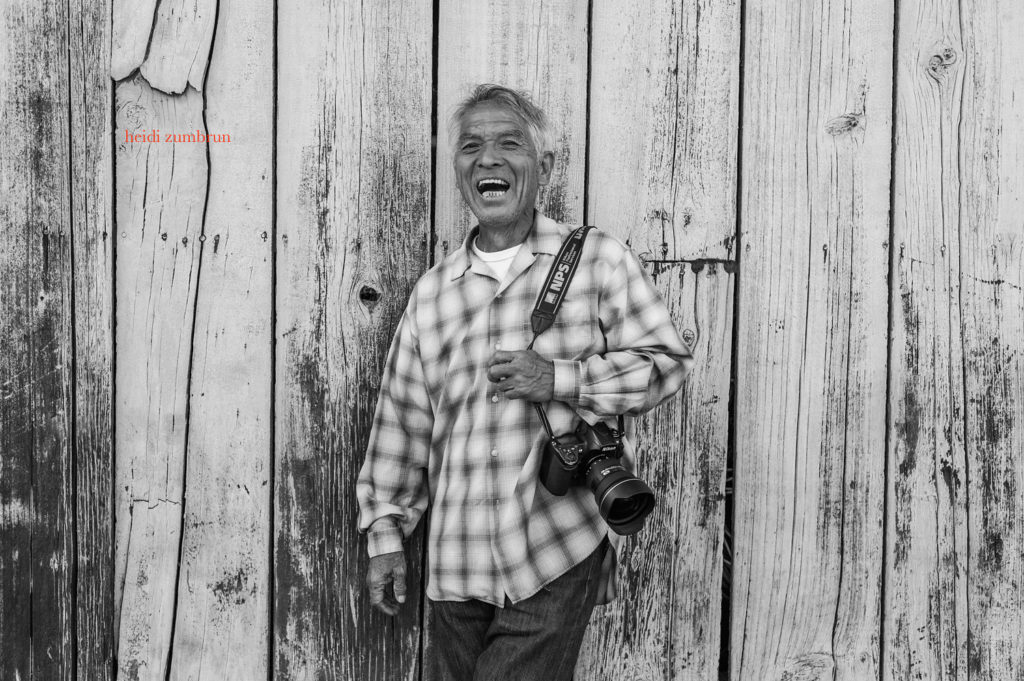

Gallery: Heidi Zumbrun

What does it look like when riders on every kind of motorcycle, with ages ranging from their 20s through their 70s, in a mix of genders and colors, get together for a few days of riding, racing, skating, and surfing? It looks a lot like Wheels+Waves. Heidi Zumbrun, a Los Angeles-based photographer (and motorcyclist/surfer) brought her particular vision to the Wheels+Waves California event in Aug 2017. We love her photos of the event, which was part-sponsored by TheVintagent, and organized by Paul d'Orléans with the Southsiders MC of France (who host the Wheels+Waves event in Biarritz, since 2012).

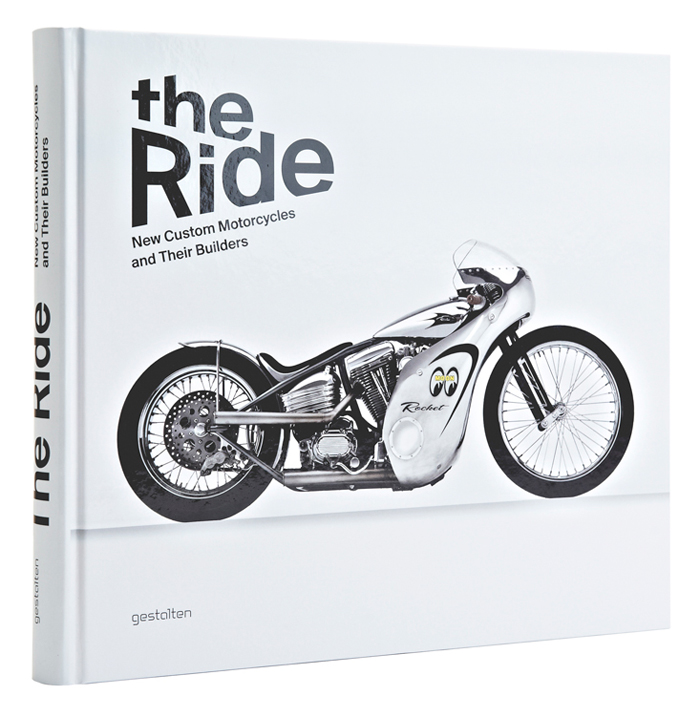

The Ride: Vintagent X Gestalten

Words: Gestalten Photos: David Ferrua, David Finato, Kristina Fender, David Hans Cooke, Brandon La Joie

We did the Ride thing. It was during the summer of 2012 that we decided to put pen to paper and document the thriving alt-custom motorcycle scene. With Chris Hunter from BikeEXIF at the editorial helm and contributors ranging from Gary Inman, David Edwards, and Kristina Fender to Maxwell Paternoster and Paul d’Orléans, we created our book The Ride: New Custom Motorcycles and Their Builders, which hit shelves in the autumn of 2013. The book’s 320 pages celebrated unique machines, the people behind them, and the lifestyle they inspired. Riding a motorcycle was at an all-time high and, more importantly, the soul of the pastime had been renewed—it was fun again. It’s no longer about soulless, technology-driven progress that leads to transformer-like fairings, dominating electrical assistant systems, and other complicated additions. Two wheels and an engine – that’s what it’s about: The simplicity of the motorcycle speaks to a younger generation, and there is no end in sight.

Haven’t checked out the books yet? Here is your chance.

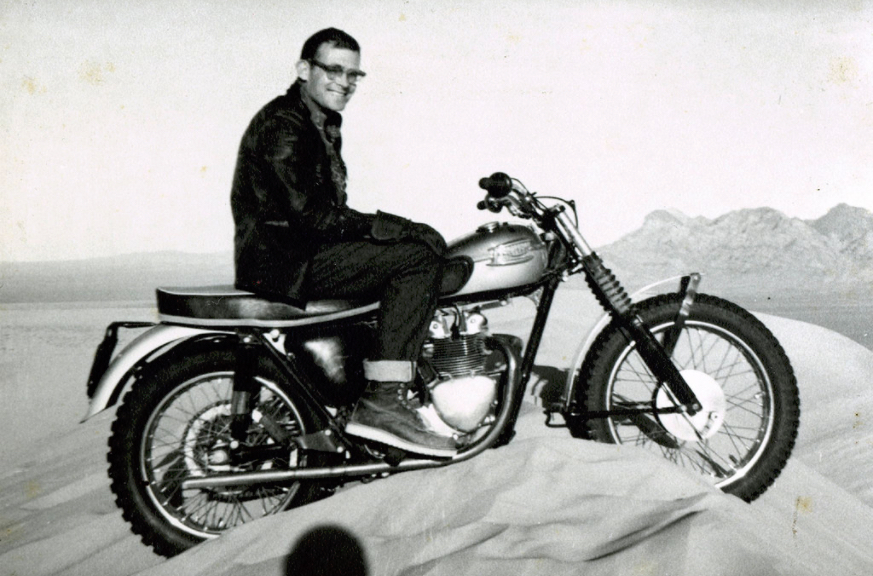

California Dunes Riding in the 1960s

[Photos: Bill Greene]

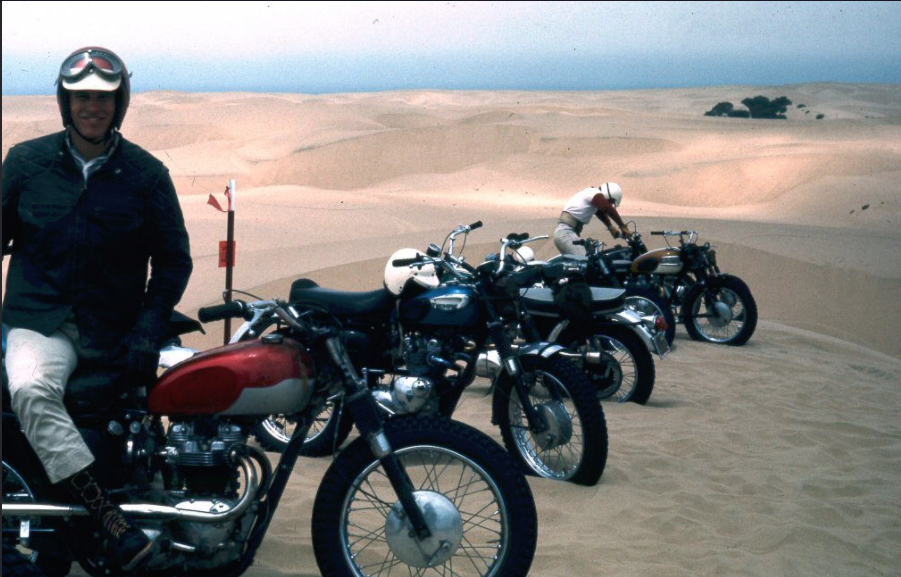

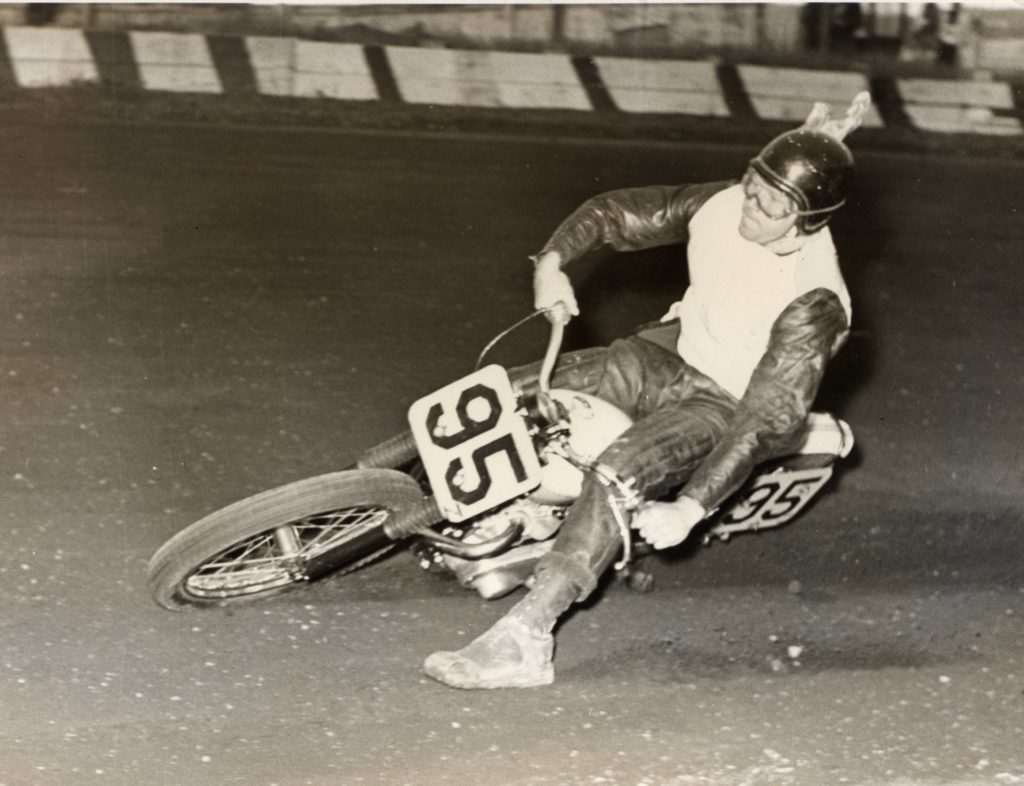

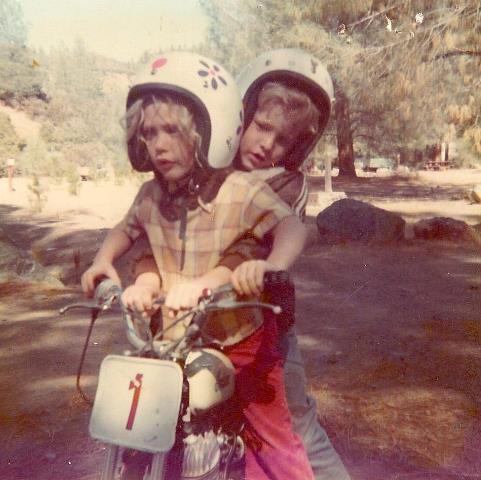

We're grateful to Bill Greene for allowing us to publish these amazing family photos. Bill's father and friends seemed to have a pretty grand time riding around desert and dunes in California during the 1960s and '70s, competing in races, spectating at races, or just having fun with the family in the outback. These photos were taken with a humble Kodak Instamatic camera.

The location of the black-and-white shots is Kelso Dunes, in December 1963, and the slanting midwinter light makes for particularly dramatic shots. Kelso dunes is one of three places in the US which has 'singing sands', or more appropriately, 'booming dunes'. When large masses of sand are shifted down a slope (as from a motorcycle wheel, or a kick from the peak), the movement produces a loud rumble which sounds like a turboprop plane or low-flying B29. This phenomenon has been described for over a thousand years in Arabian and Chinese literature.

The dunes in this area rise to over 200m (620'), with the tallest reaching 700', and are part of the Mojave National Preserve, a 1.5 million acre area straddling CA and Nevada; the dunes area was closed to motor vehicles in 1973, so these photos can never be repeated.

The color shots were taken with a Pentax SLR with slide film, mostly at Oceano Dunes (formerly Pismo Beach), and are still accessible to motor vehicles. Most were taken in the mid-1960s. The motorcycles are mostly Triumph unit-construction 500cc TR5 models, with little or no modifications from stock. Riding gear consists of light leather jackets, Levi's blue jeans, work boots, and work gloves (0r no gloves), and open face Bell or Buco helmets - classic stuff. Enjoy!

Al(ta) in the Family

Words: Paul d'Orléans. Photos: Derek Dorresteyn / Alta Motors

We're pretty sure Mario Andretti didn’t change Elon Musk’s diapers, but Dick Mann did chaperone Derek Dorresteyn’s mother on her dates. Even better, Derek's uncle Dick, an AMA Hall of Famer, was the cover boy on the very first issue of Cycle World in September 1962. With such a family legacy, a veritable baptism in gasoline, it’s no surprise Derek, the co-founder and Chief Technology Officer of Alta Motors, has entered the motorcycle industry. He learned to ride in the Richmond Ramblers MC back lot at age 4, and spent a few years chasing the family legacy on speedway tracks. Now he and his company are knocking loudly on the doors of the AMA, demanding to race head-on with gas bikes in sanctioned Pro events, and proving a brilliantly designed competition e-bike will shortly make their rivals obsolete.

Motorcycles are Derek’s family story, period. His maternal grandfather co-founded the Richmond Ramblers MC in 1946, mortgaging his home to help buy a clubhouse in Point Richmond, with enough adjacent open space to host club rides and competitions. Derek’s father was a very talented rider, but a stint in Korea with the Marines left his 12-year old brother Rich to take care of his Mustang minibike. Rich used the Mustang with the notorious Richmond ‘paperboy crew’ in company with Dick Mann, delivering newspapers on small motorcycles at a breakneck pace in those lightly-trafficked days. Paper routes cultivating AMA Hall of Famers – what have we lost today? “The paper route was to earn some money, but having the bike was what it was really all about. The paperboys would race around and do stunts.” Two years later, Mann encouraged Rich Dorresteyn to try flat track racing; Rich was 14, but lied about his age, and got his first ride on Dick McAfee’s Triumph Grand Prix flat-tracker.

Dorresteyn’s paternal and maternal family threads merge at the local Belmont ¼ mile dirt track. It was home base for Derek’s grandfather, and family friends like Mann and Joe Leonard. “My mom Ginny knew all the racers, helped collect tickets, and later she was the trophy girl. She met my uncle Rich, and his parents, and Dick Mann was the chaperone on her dates!” But it was Bill Dorresteyn who won the trophy girl (a motorcyclist herself of course), and they raised their two children on two wheels. “As a kid, our whole social scene was around motorcycles. My mom was employee #3 at Cycle Gear, and worked at various cycle shops as I grew up. My dad had talent but raced for fun; he won the National Jackhammer Enduro overall in ’68 on a 650 Triumph. My sister and I grew up riding on dirt; she was 3 and I was 4 when they put us on bikes, it was a fun family thing. My sister raced a little, and while we’ve always ridden off-road, we have street bikes too of course.”

With the Dorresteyn family name, it was expected Derek would take up the family business. “My entire life, our social world asked when I would start racing. Uncle Rich was a popular, well-known rider with a lot of fans - I grew up in awe of him and his accomplishments, with so many stories from my dad.” Rich led a hard life though, and struggled with heart disease even while racing. “At the 1958 Peoria TT, Dick Mann and Gary Nixon had to practically lift him onto his bike, he was so weak, but he won the national! These guys had no athletic rigor, they were working class toughs making a living by winning races. Rich died at 38, in 1976, from heart trouble after rheumatic fever.” While Derek’s family attended perhaps 20 races per year, “there was an understanding racing wasn’t what I should do; they’d seen so many people killed and injured, they didn’t see the point in it.”

Of course, that didn’t stop Derek from wanting to race, and he chose Speedway as his poison. “My mom worked at a Jawa speedway bike dealer, and one of their riders would become a multi-time national champion. I’d been riding since I was 4, was pretty good at it, and friends I’d grown up with at the Ramblers were racing.” When he told his parents he wanted to race, at 15, they said ‘get a job, finance it yourself, and we’ll see.’ He got a job at Cycle Gear, earned enough to buy a speedway bike, leathers, and a helmet, and “it was like a switch flipped; suddenly the whole family is going to speedway races 3 nights a week, all over California.” He was pretty good too, “I won a few races, and made a little money, but not nearly as much as I put into it.” Derek’s tuner-sponsor was Dale Lineaweaver, a legendary veteran builder of outrageously cool bikes, including a National Championship winning Husaberg, flat-track Ducati and BMW twins, and even dragsters. Lineaweaver garners ‘we are not worthy’ props at Sideburn magazine, but has since abandoned gasoline… to become the principal tech at Alta Motors.

Blame it on San Francisco, a former Bohemian stronghold transformed by the tech industry, for the inspiration to design an off-road competition motorcycle. Dorresteyn gave up racing while in college studying Industrial Design, and supplemented his post-college work in custom fabrication with his Moss Machine Co. and by teaching 3-d CAD design at the California College of the Arts. Keeping on the cutting edge of machining technology meant reading the blog of Tesla’s Martin Eberhard regarding new lithium-ion batteries which made possible a compelling electric car. “I was racing Supermoto for fun in the mid-‘00s, and developed a high powered but really peaky KTM motor with Lineaweaver. Reading Eberhard, I started thinking, ‘if this was an electric motor, I could change its characteristics with software’… I thought ‘if the tech is ready for a car, maybe it’s ready for a motorcycle’.” He tossed the idea to the brilliant industrial designer Jeff Sands, a riding buddy (and inventor of the step-in snowboard binding); the idea stuck and they began modeling an electric racer. They shortly discovered no available components matched their performance targets; they’d have to build it all from scratch.

“We hired an electro-magnetic engineer for a special motor design, which I then built into a mechanical design. At one point the spreadsheet simulation looked great, the CAD design looked great, we had propriety tech in the motor I’d designed, and we thought ‘this is a business’.” That was 2009, and with a rough business plan they sought a CEO to help orient the business and raise capital, and found the like-minded engineer-turned-tech consultant Marc Fenigstein. Still, it was an after-work gig for the 3 principals, and their first $30,000 to build a prototype came from family members. “We built that first prototype in 6 months, and hit our key design metrics within about 5%. But it was just a proof of concept; we built it to look good, and it worked well, but it was not mass producible.” By 2014, they’d secured real investment, and started on a production prototype, which meant a total redesign. “We also had to build a whole company, making key hires like battery expert Rob Sweney, and creating an automotive supply chain; it took 2 years to commercialize the process, to perfect the design, pass all our tests, and develop the machine on the track. Now we have a team of 55, with a wonderful product with great reviews, on a real trajectory to be successful.”

Dorresteyn reflects that “It’s been a hell of a ride, to bring the Redshift into the world.” He notes that world-class racing vehicles aren’t really built in the US; “We have nothing like the F1 or bike industry in Europe, or the depth of the industry in Japan. We’ve had to hire folks from the bicycle world, from Tesla, from tech; none of our designers are from traditional motorcycle building or racing. It’s an interesting commentary on American industry.” Another commentary is the resistance Alta is getting from the racing world, where the Alta Redshift is barred from national and world championship competition. But we’ve already seen a relatively inexpensive electric motorcycle win Pike’s Peak; can an MX GP or Supercross win be far away? “We try to be kind, but our bike and customers are in effect telling the industry, ‘your product is obsolete’.” Alta and other electric competition machines aren’t going away, and we’re entering an uncomfortable phase of co-habitation, not unlike the late 1800s, when steam, electric, and gasoline-powered vehicles all scared the horses. Things will change, and Alta may build the bikes to change them. If so, another Dorresteyn would be a candidate for the AMA Hall of Fame, if that body ever kicks its gas-huffing habit and sees the bright blue spark of the future…

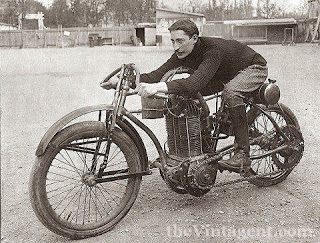

Glenn Curtiss: 136mph in 1906?

Words: Paul d'Orléans. Article and Photo: Scientific American

The life story of Glenn H. Curtiss, founder of the American aviation industry and a pioneer motorcycle manufacturer, is peppered with tales of bravery and mechanical inspiration. Curtiss was also no stranger to controversy, as his years-long legal battles with the Wright brothers over their airframe patents did more to impede the progress of the pioneering aviation industry than even technical hurdles! It was all sorted in the end when Curtiss-Wright Aviation was formed in 1929, although aircraft historians still argue 'who did what first' regarding the birth of flight. Another, lesser controversy concerns Curtiss' 1906 speed run on Ormond Beach, Florida, which contemporary accounts claimed reached a one-way speed of 136.3mph. Curtiss used a V-8 engine of his own design and manufacture, housed in the world's first double-loop chassis of his own construction, to tear across the wet sand at Ormond, although as the article below notes, this was not an officially timed speed run. So the question will forever hang, until someone drags the V-8 racer out of the Smithsonian Institution to see what she'll do!

Scientific American, Volume 96, Number 06 (February 1906)

The Fastest and Most Powerful American Bicycle

"What is unquestionably the most powerful, as well as the fastest, motor bicycle ever built in this country made its appearance at the races at Ormond Beach recently; but, owing to the breaking of a universal joint and subsequent buckling of the frame, this machine made no official record. It was built by Mr. G.H. Curtiss, a well known motor-bicycle maker, with the idea of breaking all records. The machine was fitted with an 8-cylinder air-cooled V-motor of 36-40 horse-power. The motor was placed with the crankshaft running lengthwise of the bicycle and connected to the driving shaft through a double universal joint. A large bevel gar on this shaft meshed with a similar one on the rear wheel of the bicycle. The total weight of the complete machine was but 275 pounds, or 6.8 pounds per horse-power."

"In an unofficial mile test, timed by stop watches from the start by several persons who watched through field glasses a flag waved at the finish, Mr. Curtiss is said to have covered this distance in 26 2-5 seconds, which would be at the rate of 136.3 miles an hour – a faster speed than has ever been made before by a man on any type of vehicle. Unfortunately, before this new mile record could be corroborated by an official test, the universal joint broke while the machine was going 90 miles an hour. Fortunately, it was brought to a stop without injury to its daring rider from the rapidly-revolving driving shaft, which was thrashing about in a dangerous manner. Later on, the frame buckled, throwing the gears out of line, and the official test had to be abandoned. With his 2-cylinder machine Curtiss rode a mile in 46 2-5 seconds in a race with Wray on a 2-cylinder 14 horse-power Peugeot motor bicycle, only to be beaten 2 seconds by the latter in a subsequent race, wherein a speed of about 80 ½ miles an hour was obtained. With one of his single-cylinder machines Curtiss made a mile in 1 minute 5 3-5 seconds on January 21."

Bandit9 Steals Fashion Mojo

Words: Paul d'Orléans. Photos: Wing Chan. Originally published in Cycle World

Motorcycles and Fashion; they’re a perfect match, just ask any big fashion house forking out zillion-dollar ad campaigns to the big glossy mags every year. Motorcycles make ideal props for langorous models, as let’s admit it, two wheels push all sorts of romantic buttons in the non-riding public, whether it’s a longing for a nonexistent past (Ralph Lauren’s sepia-toned moto-safaris), or a projection of superpowers on a top model (Chanel’s flying Ducati ‘ridden’ by Keira Knightley).

A perfect mashup of designer gear + groovy bike is very rare, unless we’re going retro again with Rocker togs/Triumph or Depression workwear/Harley, which has Been Done Before. From the furthest geographic reaches of both clothing and custom bike design, we have the curiously ideal mix of Saigon’s Bandit9’s silver machine with Ukrainian designer Konstantin Kofta’s rigorously futuristic backpacks, shot with a Modernist/minimalist sensibility by Wing Chan. You may or may not like Bandit9’s ‘Eve’, based on a late ‘60s Honda SS, but you can’t deny the purity of Eve’s lines, and the remarkable transformation of a totally unremarkable and near-universal, super-ordinary commuter machine.

Daryl Villanueva, the Bandit chief, explains the mix: "Konstantin contacted me months ago to acquire an EVE for himself. Because of the conflict in Ukraine, we were unable to ship bikes to his part of the world. But we talked about doing a project together; I saw his work and there is nothing out there like it. I was all over the opportunity of working with him. Bandit9 is really interested in becoming more than custom motorcycle company. Fashion is just one of the many industries we're trying to break into. We're trying to create a different class of bikes that's not just for existing motorcycle lovers. I think there's a world full of people who would be interested in bikes if they understood what a bike can be. And that's why we look at different disciplines for inspiration."

The EVE was inspired by ‘Sci-fi; I'm trying to build bikes that belong in another dimension. I think that's what really excites people . Why not get inspiration from NASA, comics, biology, watches, music? EVE's sleek design is a mix of influences from brass musical instruments to space travel.’ Wing Chan’s photo shoot captures that mood perfectly as a retro-futurist fantasy, complemented by the Ruby helmet (RIP, sniff), and Kofta’s Sci-fi film prop accessories. Fashion and industrial design fans are eager adopters of new and edgy style; bikes like EVE just might open the door for a whole new cadre of motorcyclists.

Lena the Killer

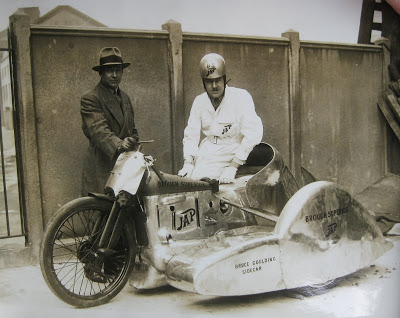

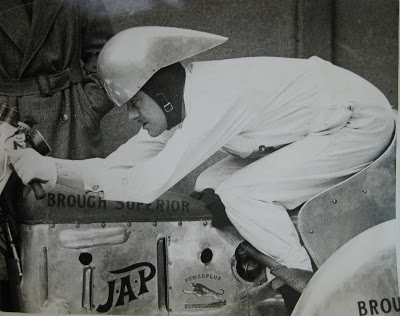

For a moment in the 1930s, sporting contests became a surrogate battleground for rising international tensions. While international-level sports (like the Olympics) have always carried the flag of national pride, in the 1930s the rise of ultra-nationalist politics - Fascism - saw motorsport used as a propaganda tool to bolster new regimes. Everything from foot races to the Grand Prix circuit carried the weight of 'proving' the superiority of an ideology and/or a people. By the mid-1930s Germany and Italy began to subsidize motorsports via cash and technology to particular companies (BMW, DKW, Gilera, etc), while their rival factories were roundly ignored by their home governments. In Britain, for example, racing was the purview of a few factories, and their racing teams backed by wealthy amateurs, using a pre-industrial model of patronage. The contest for World Speed Records were a glaring example, with independent teams in the UK cobbling up land speed racers in sheds, combating increasingly well-funded teams from Germany. It was a romantic story of technocratic teams versus old-boy amateurs, documented in our 'Absolute Speed, Absolute Power' series. Regarding the British teams; while AJS made an occasional attempt on the World Record, in the end only George Brough (Brough Superior) had the will, the connections, and available expertise to make a World Record happen. The Germans and Italians had the engineers, factory backing, wind tunnels, and cash from Adolf and Benito. The Brits had grit and plenty of track experience, and were the best engine tuners and chassis builders in the world. Thus, in 1932, one could witness a group of Australians riding British machinery on Austrian soil, snatching the World Land Speed Record from German hands.

Alan Bruce was well-known in Speedway circles, having set the sidecar lap record at Wembley Stadium in 1931. Australians have a dirty affinity for three-wheeled cinder sliding, then as now, and one commonly sees Vincent-powered crabs even today kicking up dirt Down Under. Bruce got the notion of a sidecar Land Speed Record while watching Paul Anderson take a national record with his Indian outfit, down Sellicks Beach, South Australia, in 1925. It took another 6 years of toil to modify an S.S.100 Brough Superior for a total speed attempt; a supercharger was added to the engine bay, and Alan Bruce hand-pounded a shapely set of aluminum alloy bodywork... which as you can see from the photos addresses the issue of drag by streamlining the rear of the outfit (including the rider's bum!). Which was the current thinking of the 1920s and early 30s, before extensive wind-tunnel testing of aircraft, cars, and lastly motorcycles, revealed that a very small frontal area was the real ticket for piercing the brick wall of wind which hits any vehicle at high speeds.

When finished, Bruce named his beast Leaping Lena, and sought a flat, straight road to set his record. In 1931, there were only a few suitable locations for a really fast run; Hungary (Gyon and Tat), Austria (Neukirchner), the U.S. (Daytona/Ormond beach), the U.K. (Pendine or Southport beaches), France (Arpajon), and Germany (Ingolstadt). As speeds increased for record attempts, beaches became increasingly undesirable due to Neptune's fickle road-laying efforts, and attendant delays (read:money) for a perfect surface. As all but the beach venues were public roads, the political machinations (read:money) required to arrange a few days' testing and eventual full speed runs could be daunting to a small and dedicated bunch of amateurs. And amateur is a fitting description for ALL speed-bitten enthusiasts, until National (Socialist) pride began investing in sporting contests, and little swastika roundels appeared on the tails of wingless two-wheeled aircraft. But I'm getting 5 years ahead of our story.

In 1931, Alan Bruce and Englishman Arthur Simcock took Leaping Lena to Tat in Hungary for a series of unsuccessful runs at the Motorcycle Land Speed Record, solo and sidecar. She can be seen at Simcock's side in the top photo, sans third wheel, taken on site at Tat, where various mechanical issues beset them like gremlins, and the pair headed back to England for a winter's work sorting out Issues like supercharged induction, etc. Note the copious oil leakage from the lower bodywork panels; one wonders if the lower 'tub' is in fact filled with oil! Late April 1932 saw our familiar pair of Bruce/Simcock joined by Phil Irving, who must have provided a measure of technical expertise to sort out the troublesome animal that was Lena. Chosen venue was Neukirchner, near Vienna, and local Brough Superior agents Eddy and Kent Meyer lent a hand in any way useful - Eddy being a real champion of the marque in Europe, having won over 80 'firsts' in competitions with his Broughs. Arthur Simcock's record run without sidecar ended abruptly when his goggles were blown off at speed, followed shortly by the supercharger safety valve blowing off. Local support for Lena ended there, as a local wag slipped a steel bolt into her induction tract and shortly ruined the supercharger, cutting their effort short while they frantically sought a new venue, and spares from England.

City officials of Tat were successfully cajoled (read:money) into allowing Lena's run on short notice, and our crew high tailed it towards Hungary in their truck, which blew up and delayed their arrival. Meanwhile, Arthur Simcock trained back to England for blower parts, returning to find lousy weather (why April?), but it was decided that April 30th would be The Day, and it dawned with strong winds. Clearly, the slab-sided aluminum body of Leaping Lena wasn't lethally beset by side wind handling anomalies, and a two-way average of 124mph was finally recorded, with a best one-way speed of 135mph... really going some for a rigid-frame bicycle on an iffy concrete surface. Bruce had the scare of his life while aviating the whole outfit at speed after hitting a bump with the chair wheel, the entire plot lurching nearly off the road. While distracted and momentarily shutting off, he didn't realize he had passed the timing strips and carried on at full bore, only to hit a railroad crossing at 135mph! Man, motorcycle, and sidecar shot into the air, split the streamlining on impact, and nearly sheared off the carburettor, but the hard Aussie Bruce kept the animal between the hedges, and their day was done. As he said, "Yes, it felt fast all right!"

The Age of Monsters

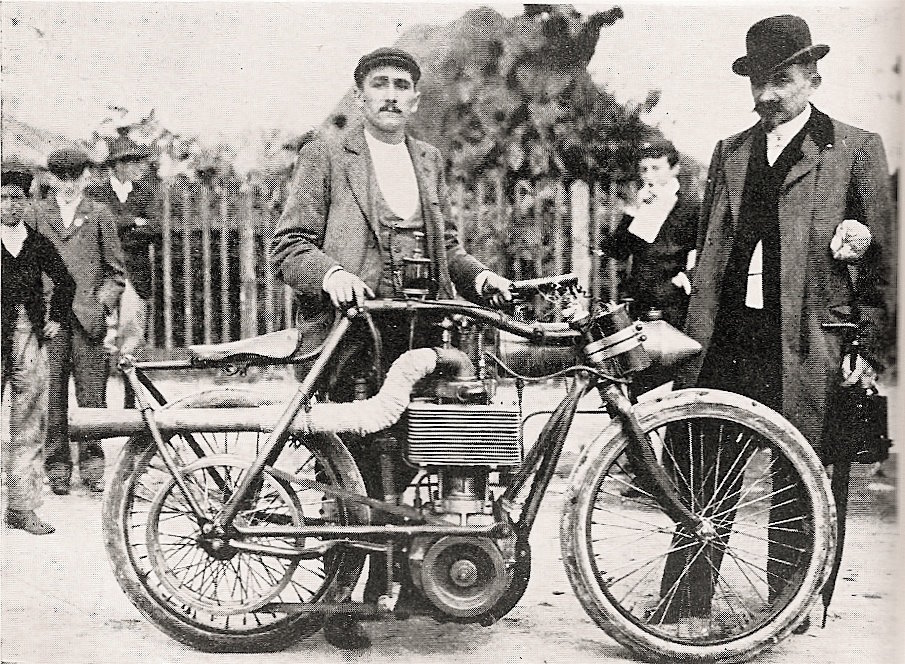

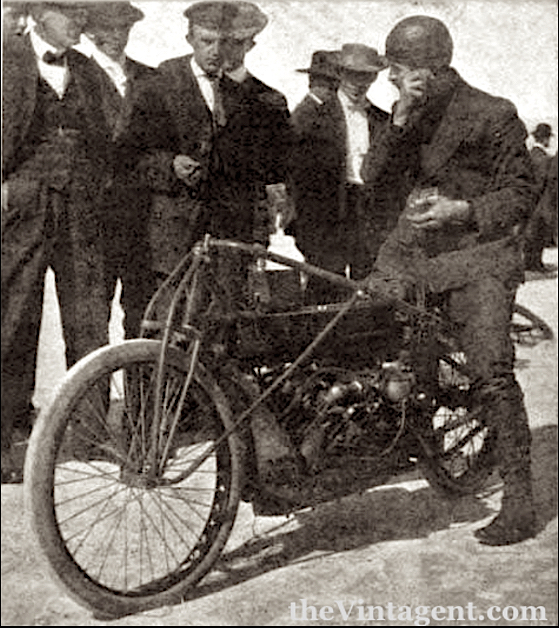

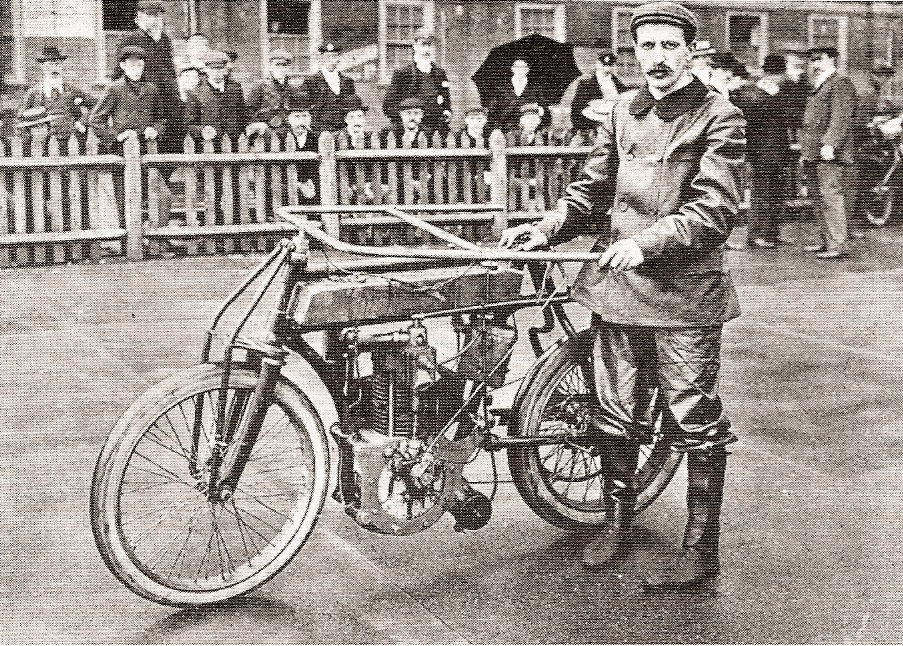

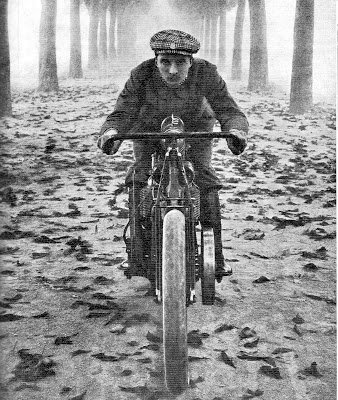

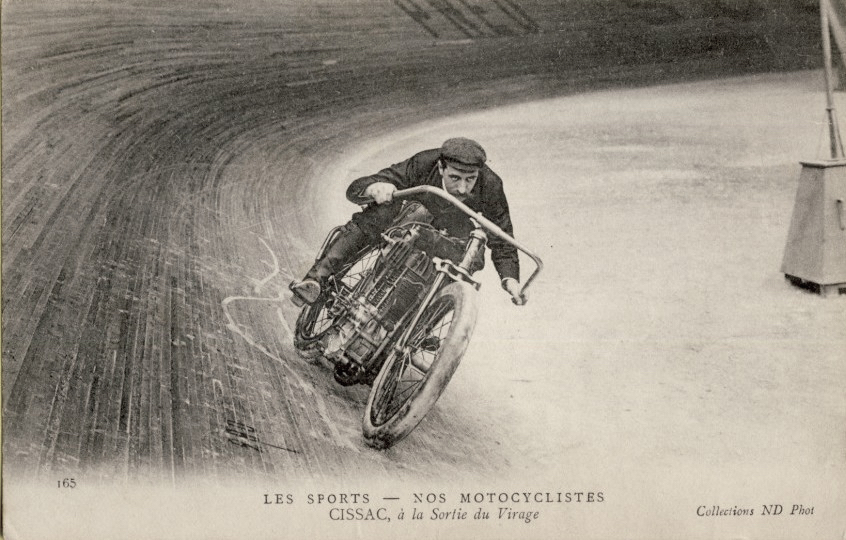

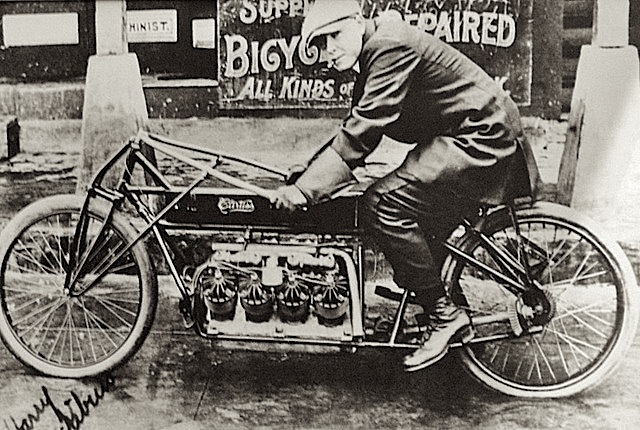

Dec. 6, 1903: MOTOR CYCLE MONSTROSITIES, By H. O. Duncan.

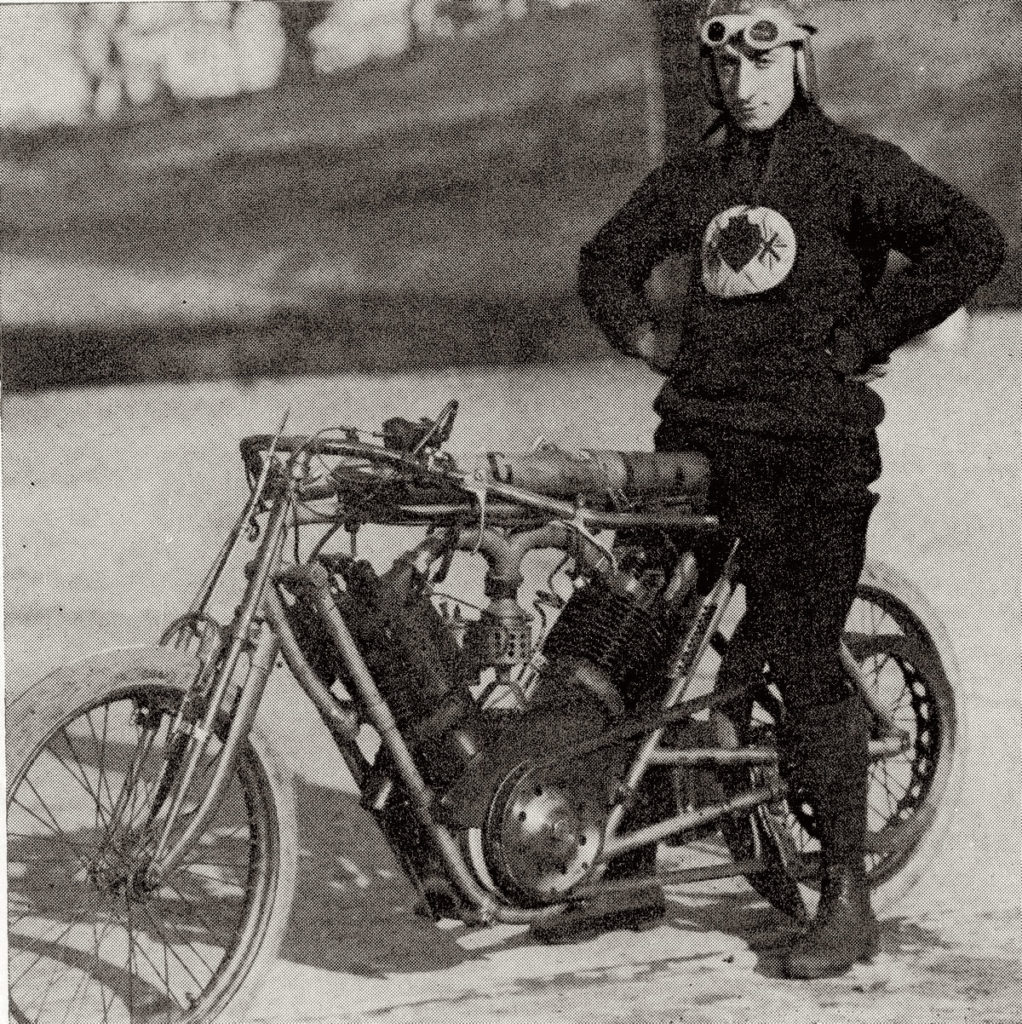

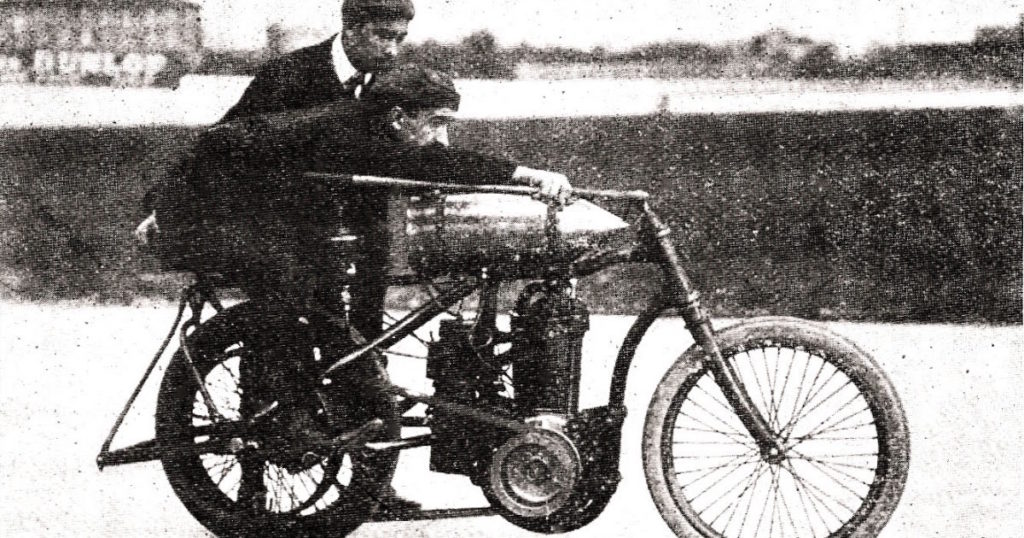

Racing rules in France and Austria (the only European countries which hosted races at that time) gave no restrictions on engine size; one cure for a weak little engine is to incorporate a much bigger (albeit equally inefficient) motor into a motorcycle. During a beautiful period in those pre-1906 days, a free-for-all developed with designers throwing the most unlikely engines between two wheels. Cylinder capacities of over 1 liter EACH were not unheard of - these were steam engine dimensions, which of course, was the common currency of the day, as trains and boats were the first truly 'motorized' vehicles, using steam for motive power since the heady days of James Watt and Robert Fulton.

H.O. Duncan decried them as 'Monstrosities', setting a poor example for the public, and arguments such as this have altered the course of motorcycle evolution in the past 100 years in significant ways. When, in the course of racing development, designers have reached for extreme measures in the quest for advantage (ie, enhancements which bore no relationship with 'utility'), the forces of Rationality and Production-Based competition have raised the alarm and banned them. Thus, initially, engine capacity was restricted in racing to standardized formulas. In some areas, 'Works' machines were restricted - racing had to be conducted with 'same as you can buy' motorcycles. Then, as supercharging came to the fore, it was banned as well. When the number of cylinders grew to six and more in GP racing, restrictions on engine complexity were enacted. When the number of gears on lightweight racers reached 12 or more, gearboxes were limited to 6 ratios. Most recently, when the world no longer drove two-strokes, GP racing moved to four-stroke engines.

Of course, it wasn't just the French who built Monsters; the American Glenn H. Curtiss installed an experimental 40hp (6,000cc) V-8 aircraft engine of his own make, into what may have been the earliest duplex-loop frame. In 1907, he took his shaft-drive machine to Ormond Beach in Florida, and clocked 136.8mph one-way, making him the fastest man in any vehicle at the time. The shaft broke on the return run, and Curtiss had a heck of a time wrestling the beast to a stop without crashing, but such was his luck (he never crashed his pioneer airplanes either!), he finished the course, and was satisfied. His record remained unbeaten for 23 years, and the machine now sits in the Smithsonian Institution.

Confessions of a Factory Trials Rider

[Words and Photos: Gwen White]

My interest in motorcycles began in 1946, when, as a teenaged Gwen Wickham, I cheered on my heroes every week at Wembley Speedway. A few years later, after my family moved from North London to Southampton, I met Jack White, a great character who taught me to ride a motorcycle, became my best friend, and eventually, in 1958, my husband, although he was 24 years my senior.

'Jackie' White was a well-known member of the Ariel works trials team just before the war (he'd made 3rd Place in the 1934 Scottish Six Days trial), and he encouraged me to ride in trials with him. My first trial was the Sunbeam MCC's Novice Trial in 1950 on Jack's 'Flying Flea' Royal Enfield. Another competitor that day was Mike Jackson's elder brother John, who at 17 was also competing for the first time! Jack then prepared a 125cc BSA Bantam for me, which I rode in open-to-centre trials most Sundays and a few Nationals when I could get a Saturday off from my job in a hospital.

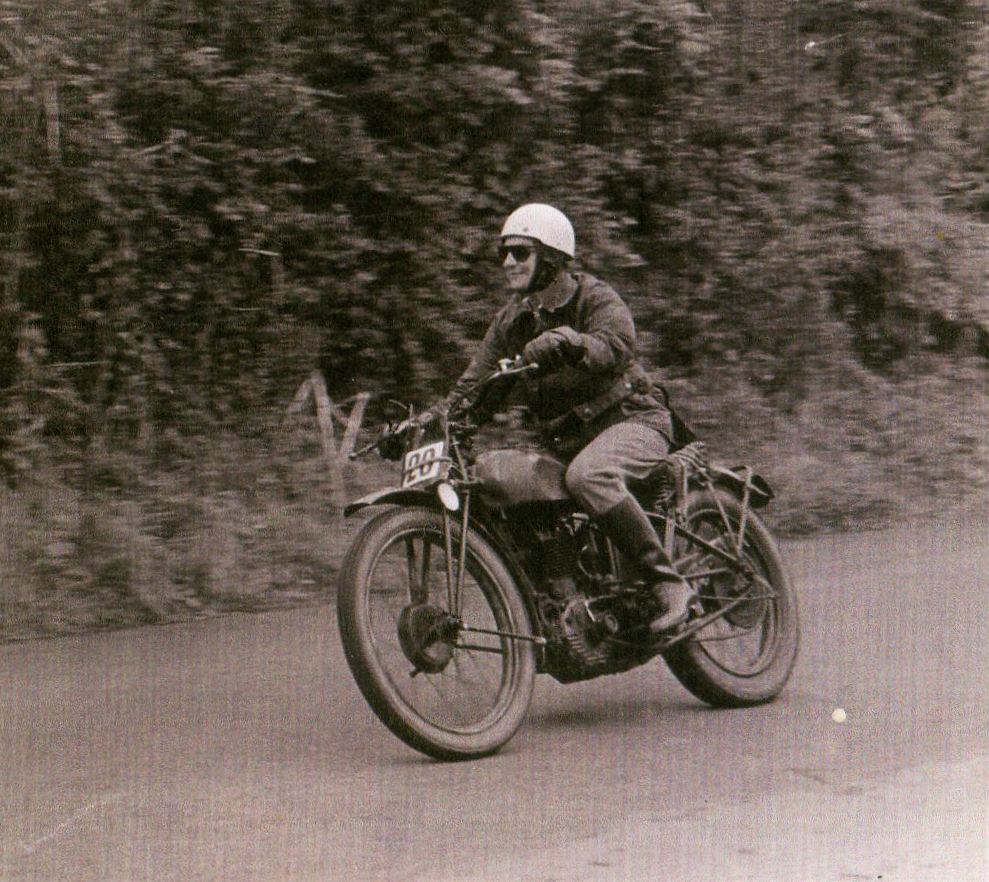

In 1952 I was 21 years old, and progressed to a 197cc Francis Barnett, and rode it in that year's Scottish Six Days Trial. In those days we started from Edinburgh and I remember lying awake in the George Hotel listening to a nearby clock chiming every hour throughout the night - I was too excited and apprehensive to sleep. One of the biggest adventures of my life was about to begin. On a damp, grey morning the Provost of Edinburgh was the starter for our long journey to Fort William. The scenery was breathtaking, with the morning sun turning the snow on the mountain tops a delicate pink. It reminded me of the time I had struggled up Kinlochourn, to arrive at a mirror image of the sunlit mountains and pine trees of Glenelg reflected in the still water between us. I was glad that I was not a leader in the trial, and could afford to squander a little time to drink in the beauty of the scene. Such was the comraderie amongst the riders that almost everyone who passed me asked if I was OK. In 1952, the generosity with which we girls were treated by the other riders was heartwarming. There were 5 of us; Mollie Briggs, Barbara Briggs (no relation), Joan Slack, Leslie Blackburn and me. Needless to say, a fellowship developed between us. Jack had a similar bike in 1952, and had modified both of them by fitting friction dampers to the forks, and had altered the steering head angle, which made them handle well. Unfortunately, Jack's bike developed ignition trouble and he had to retire on the Wednesday, but mine carried me to the finish 'without missing a beat'. The Scottish was an adventure and experience that I shall never forget; the combination of Highland scenery, motorcycles, and old friends is irresistible.

I was lucky enough to ride in it again in 1957, this time on a 197cc James Commando (incidentally, the previous owner was John Jackson - he and Mike were fellow Southampton Club members and were by then very successful trial and moto cross riders). I was privileged to meet people whom I have since realised were legends, including Alan Jeffries, a cheerful, kindly character, who offered to replace the frame of my James if it could not be repaired. It had twisted during a fall on the Wednesday and the chain had run off the sprocket at the slightest provocation for the rest of the trial. The experience of riding a motorcycle in this state over the forbidding Rannoch Moor, which seemed endless, certainly plays its part in preparing me for traveling anywhere on a tarmac road. I managed to finish the Trial, but with a large loss of marks!

I rode Francis Barnett until 1955, and then the James, in some of the other Nationals including the West of England, The Welsh Two Days, Beggars Roost, Cotswold Cups Trial, the Hoad Trial, and the Perce Simon Trial, the latter being close to home for me and in those days, run on the New Forest. What I loved most about trials was the fun, comraderie, and challenge, all in beautiful surroundings to which one would never normally have access on a standard road vehicle, although most of us in those days rode the same bike to work each day!

Jack and I were married in 1958 and we set up home together. When our two daughters came along I gave up competition riding, but still rode a bike on the road. I also rode the odd vintage bike, including Jack's 1930 Ariel 250cc Colt in a few club runs. Sadly, Jack died in 1977, but I still have that battered up old Ariel on which he won so much, including third place in the 1934 Scottish Six Days [the photo below shows Gwen riding the Ariel at a Vintage club run in 1995 - Ed.]. Despite advice to the contrary, I refuse to have it restored. To remove all its battle scars and Jack's modifications would rob it of its considerable character! I have never lost my love of motorcycling which, these days, I enjoy as a spectator, along with the great friendships which have survived the years.

Road Test: 1933 Brough Superior 11.50

The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world's rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

As hypothetical scenarios go, being asked ‘would you like to ride a Brough Superior at Wheels+Waves this year?’ is a pleasant fantasy. I don’t think it was on anyone’s radar that a Brough would actually be ridden through the Pays Basque in June, winding between all the other groovy custom bikes in the mountains. 8 Broughs would be on display at the Art Ride exhibit, but seeing one on the road…that doesn’t happen enough, anywhere. I was asked the question for real in May, but I didn’t totally trust it would happen, because life is like that. People make promises they can’t keep, stuff comes up - you know. But Mark Upham, who owns Brough Superior, is a man of his word, and I unloaded his 1933 ’11-50’ myself in Biarritz, anxious to get to know the beast.

The Ghosts of the St. George Hotel

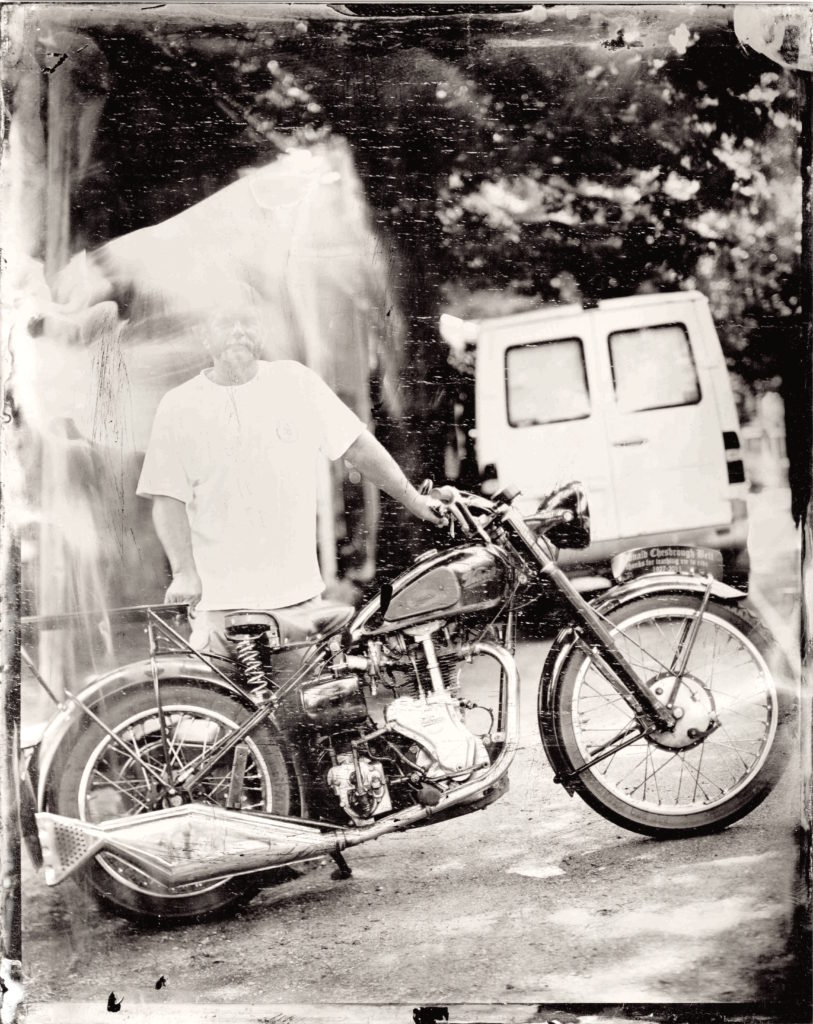

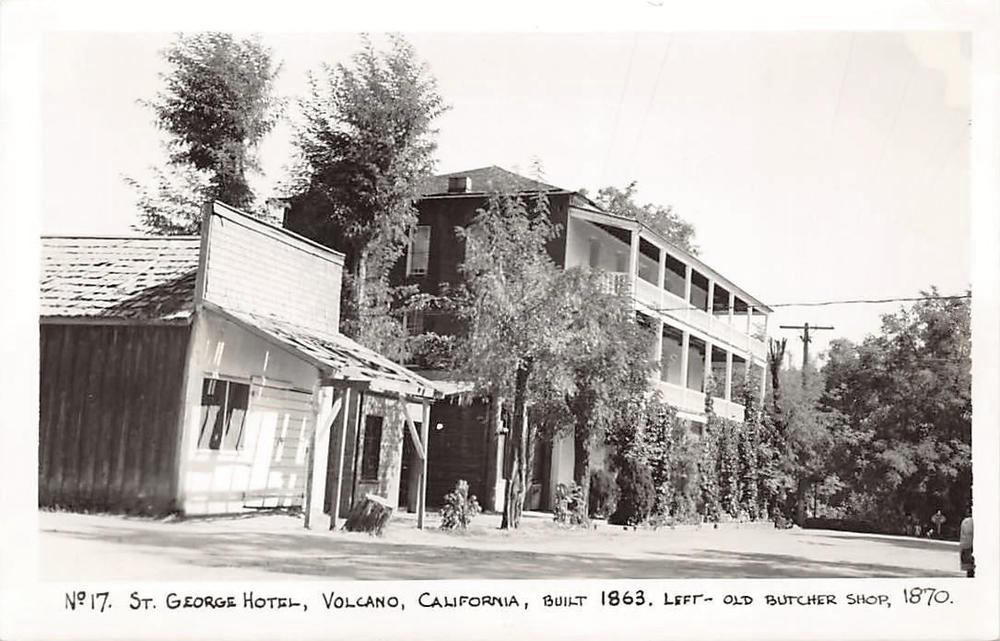

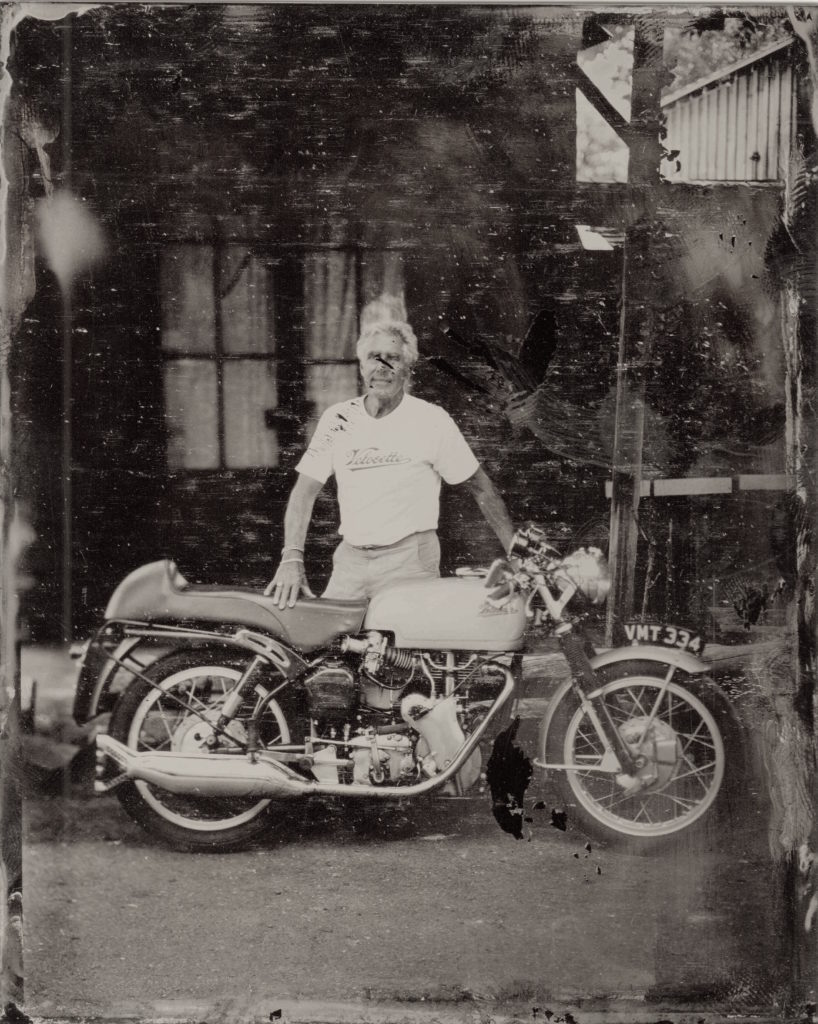

[Words: Paul d'Orléans. Photos: MotoTintype - Susan McLaughlin and Paul d'Orléans]

A dazzlingly hot July day in the California foothills is an atypical setting for a ghost story, but we weren't looking for ghosts. Nor did it occur to us we'd been haunted, until our work was finished, and our 'Wet Plate' photographs were sitting to dry on a rack. And when we finally sorted what had happened, we were chilled to the bone.

Auerberg Klassik

[Words: Hermann Köpf. Photos: Hermann Köpf, Sébastien Nunes, Fabian Kirchbauer, Peter Musch, Martin Ratkovic]

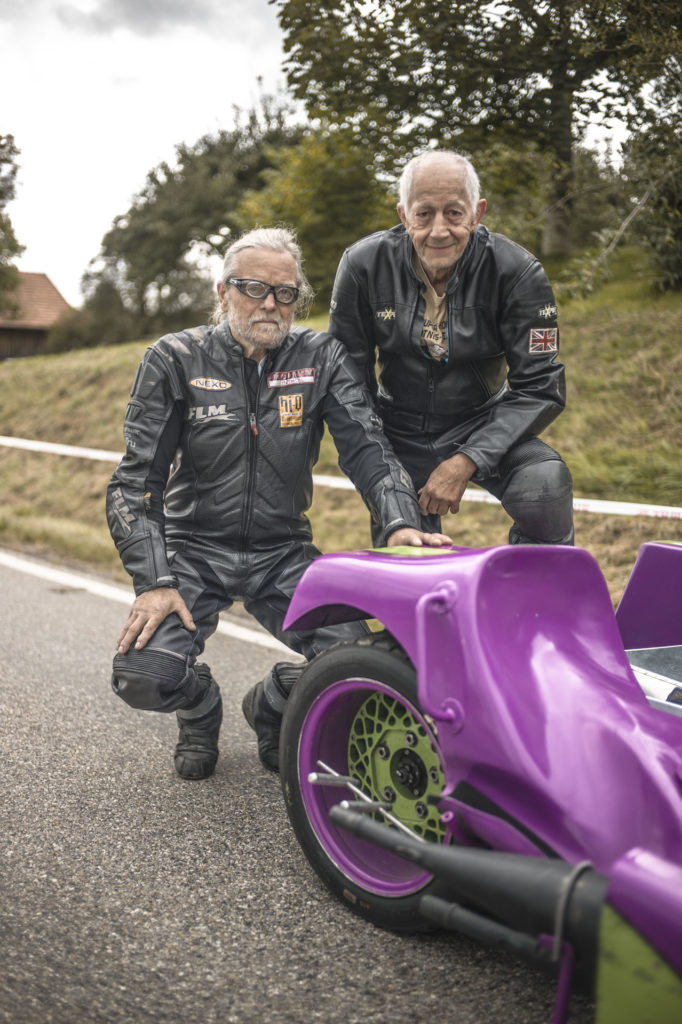

The 1,055m high 'Auerberg' is located an hour south of Munich and 20mins north of Austrian border, close to Neuschwanstein Castle - better known as 'Mad Ludwig's Castle', or the building on which Disneyland is based! At the top of the Auerberg was an old Roman settlement, where they produced coins and other metal parts. The road to the top - the racetrack of the Auerberg hillclimb - begins in small village of Bernbeuren, with about 2300 residents.

The idea of re-activating the Auerberg race has floated among car and motorcycle clubs for a while now. After break of 30 years now, it seemed a good time to revive the competition, with an updated concept - the Auerberg Klassik. I grew up in the village of Bernbeuren (although I left in 1992 for Munich), so I presented the concept to a few of my local friends, who agreed to form a club (Verein) to sponsor the event, after successfully presenting the idea to the local administration. The new concept was to include the village and all its various clubs/Vereine, with local people working together to create an event with and for the people of the village. Local Vereine/clubs supplied food and drinks to raise funds, and contributed the manpower to install the everything required for a race - banners, safety barriers, booths, pits, etc. We had 350 helpers that weekend, setting up 1.200 straw bales as safety barriers along the course.

The 'local' angle (an event by and for local clubs) was the key to our success in convincing the district administration, who held to power to authorize the race, and who had denied 17 previous attempts to revive it! Another selling point was turning the race into a 'regularity' event, where the winner has the smallest time difference in between two runs. This made an enormous difference regarding security, insurance and many other requirements, and lowered the expenses dramatically.

It took many months before we got the final approval, which left us with only 6 months to organize the event. Still, the 5 of us in the organizing committee were fully motivated and gave it our best. And it was a lot of work I can tell you. After going public with our plans, we had to close the entry list a month early, as riders filled our maximum of 170 participants, and we still weren't 100% sure we had enough space for everything - paddocks at the start, and reception on the top of mountain. News that 'the Auerberg is back' created quite an echo in the region - it seemed everyone knew about revival of the race, and local newspapers where happy with a fresh news story, and older people who remembered the original event were happy to see it return to the village they visited as youngsters.

As the weekend approached, the good weather went away, and it was 8 degrees (46F) with constant rain in the morning of first practice on Saturday. It stopped raining in the afternoon, and the mood improved...for both riders and organizers. In the end, everything went really really well, and we had crowded party that evening in the town hall with two bands, and 750 visitors. We'd asked guests in to come in the classic local costume, and encouraged them with a reduced entry fee, and event threw in a 'best-dressed contest'. A good percentage of our guests came in historical outfits, so even women who weren't riding and those with less motorcycle interest had fun.

Sunday was special; it was exactly the same day and date as 50 years before on the original race-day. The weather was still rainy in the morning but gradually got better, turning into full sunshine by afternoon. The participation was incredible, almost 7.000 visitors came in total to the track and also into center of village, where we'd organized an oldtimer rally for cars and motorcycles - about 180 vehicles showed up. We also had a few exquisite bikes on display from the BMW Museum and the Hockenheimring Motorsports Museum, even German TT-Legend and Nürburgring record holder Helmut Dähne came to ride on our historic hillclimb track.