Artist and His Moto Guzzis - Antonio Ligabue

Solace. The word is seldom associated with the allure of motorcycling, but all of us have felt it. The old cliché 'you never see a motorcycle parked outside a psychiatrist's office' has a core of truth: while riding a bike can be thrilling, there's a peaceful flip side to the experience. Most riders see-saw between both poles: the excitement of power at your wrist, and the calm of moving through a landscape, alone with your thoughts. Both these inner states are addictive, and are probably equally responsible for riders' devotion to their wheels. There's little written on the subject, perhaps because sex sells, and motorcycles' sexy side gets the headlines.

There were no special facilities for 'different' individuals from poor families in the early 1900s, and Antonio was repeatedly moved from various schools due to his disruptive outbursts. In 1913 he was handed off to a Swiss couple, Johannes Valentin Göbel and Elise Hanselmann, who were also childless and poor itinerant laborers. Antonio's health continued to deteriorate from malnourishment, and his mental health from an abusive adoptive father, and unhealthy relationship with his adoptive mother. His last school was led by evangelical priest in Marbach, but he was expelled in 1915 because he habitually blasphemed and was caught numerous times masturbating. He did learn to read, but found his greatest solace in drawing, at which he showed astonishing facility even as a child. In 1917 he experienced a violent nervous breakdown, and was hospitalized for three months.

The Magnolia Four - a 100 Year Motorcycle

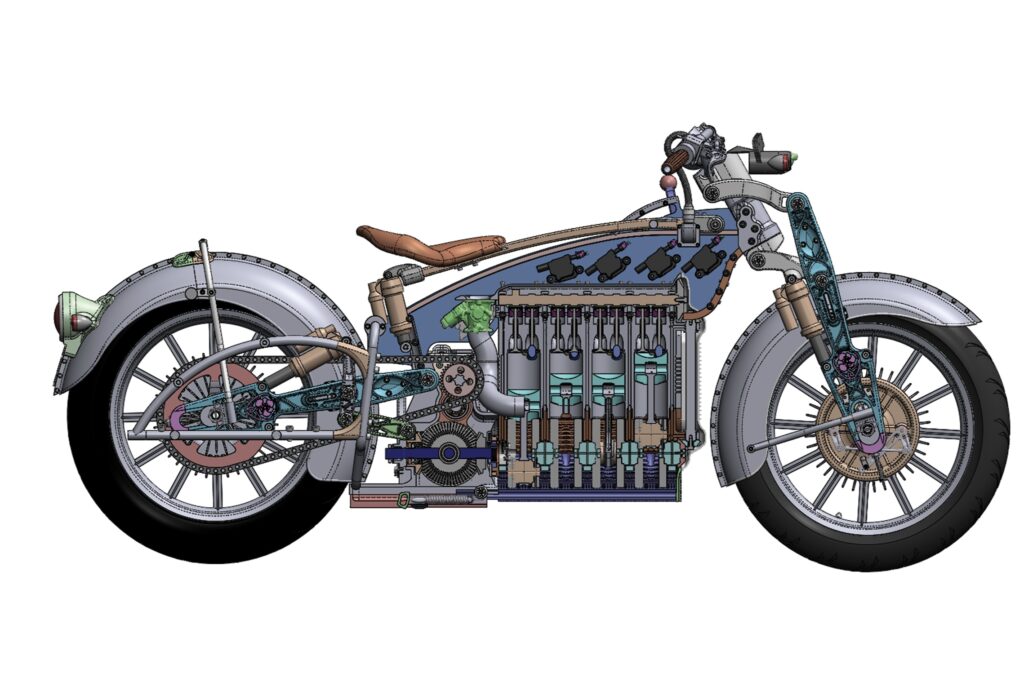

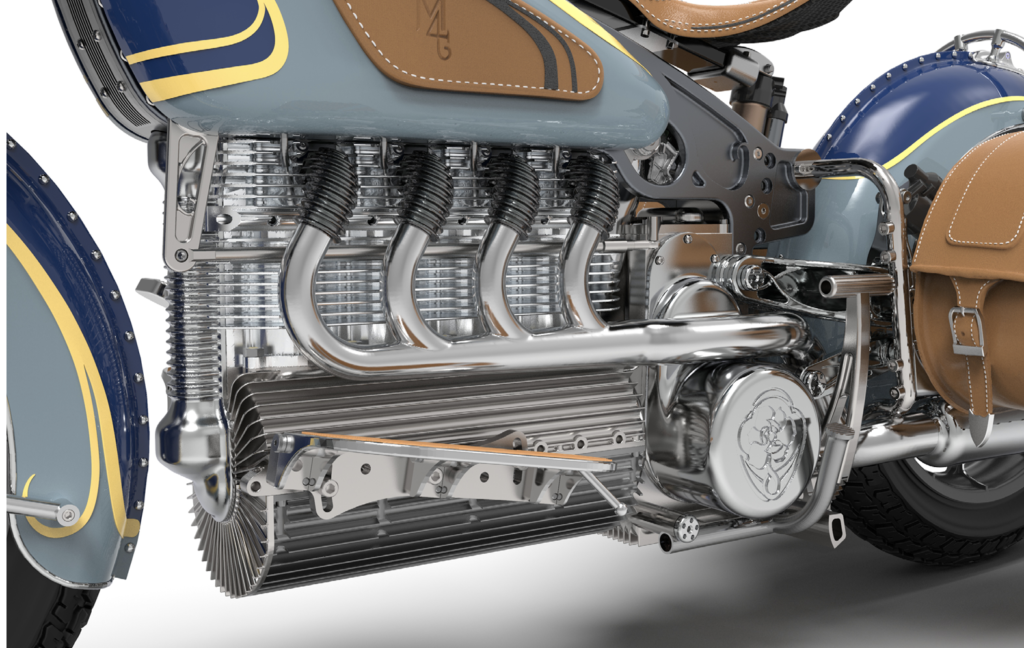

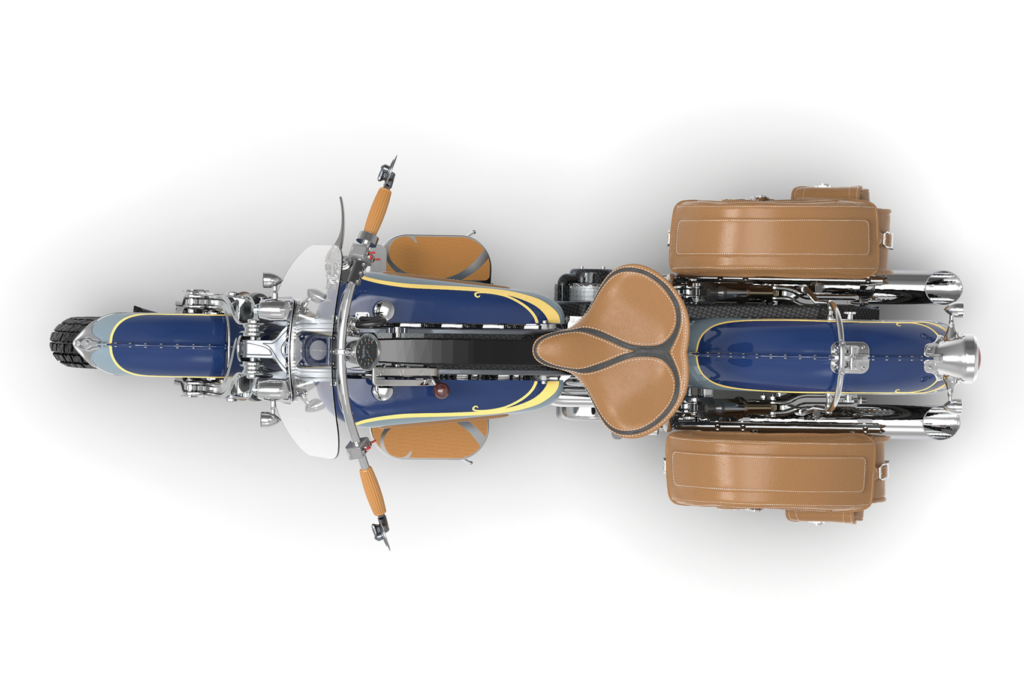

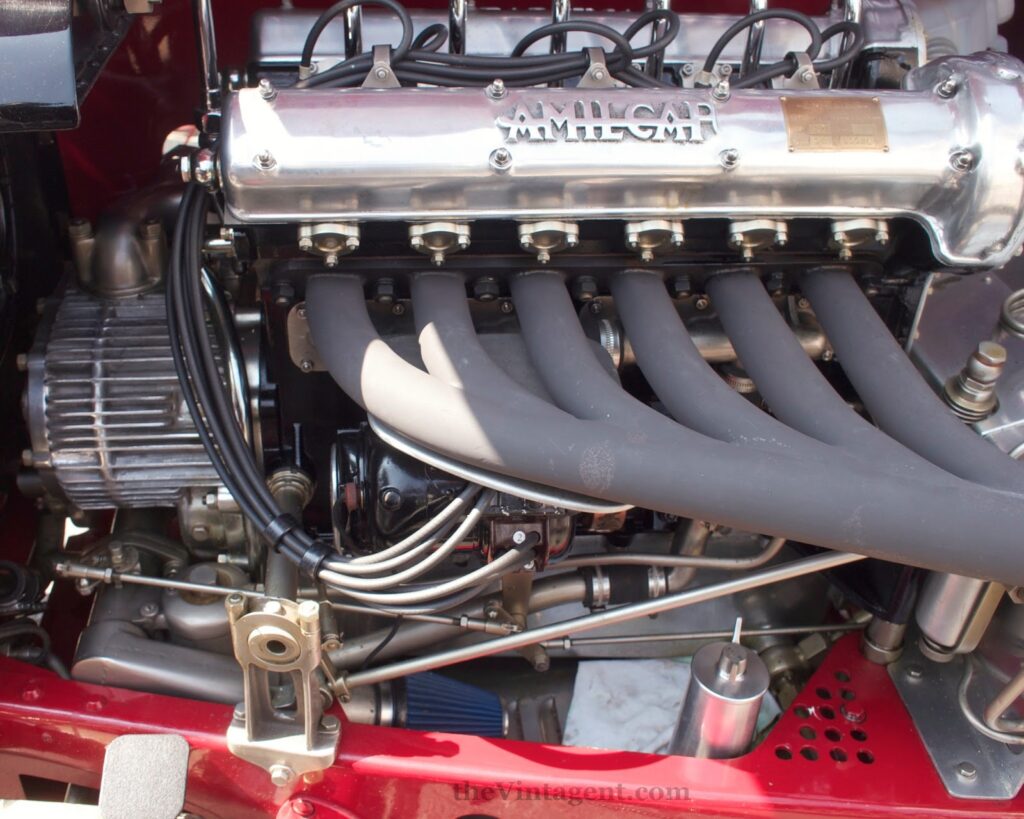

Motorcycle designer JT Nesbitt, lately of Curtiss Motorcycles, is branching out into new-old territory with his latest design. As a fan of the design of vintage motorcycles, and a vintage bike owner/rider, he's long pondered how one could make a successfully modern motorcycle that pushed the right emotional and aesthetic buttons for enthusiasts of vintage machines. He's been talking about this for years in fact, sharing sketches and ideas with his peers, honing in on what might work in practice, with intention of limited production. As an homage to his New Orleans roots, he dubbed the project the Magnolia 4.

[UPDATE: in the first hours after posting this article, JT pre-sold TWO Magnolia 4s. No I don't get a commission ;) But he wanted to stress that his intention was to produce a dozen Magnolia 4s, and as one is for him, that means there are 9 spots left. Given the interest already demonstrated among Vintagent readers, I'd say if you're interested, better give JT a shout. ]

First Handbuilt Invitational LA 2024

Just in time for the 10th anniversary of Revival Cycles' Handbuilt Show in Austin, the esteemed brand of Alan Stulberg is branching out to Los Angles for the first Handbuilt Invitational. The Handbuilt ethos is the same, to display "machines built by amateurs and professionals" with the aim of inspiring people "to work with their hands, and try and improve or repair every physical thing they own and interact with." That's a lofty ideal for a motorcycle show...but this new iteration of the Handbuilt vibe has grown to include cars, with invited builder/collectors including heavy hitters like Icon 4x4, the Philip Sarofim collection, Jay Leno's Garage, the Petersen Automotive Museum, ArtCenter College of Design, and Race Service. That's in addition to the usual two-wheel suspects like Shinya Kimura ('most Shinya builds in one room ever') Roland Sands Design, Christian Sosa Metalworks, and Bryan Fuller Moto. It's an experimental mix, and should prove popular, as the social media power of the included businesses is in the mega-millions.

The expanded focus for LA includes a 'female forward' area that includes Stellar Brand, RealDeal Workshoppe, and invited womyn builders. Mobile entertainment will be provided by Red Bull stunt rider Aaron Colton, the ever-popular Ives Brothers Wall of Death, and Saturday night live music by The Lion Heart. Our Cannonball buddy Craig Jackman (American Electric Tattoo Co.) will be laying ink on skin, if you're so inspired.

Where and When:

DTLA Auto Storage: 1219 S. Santa Fe Ave, LA 90021

Friday July 6: 6pm-12am (press opening 12-4pm)

Saturday July 7: 12pm-12am

Sunday July 8: 12pm-6pm

Two-Up on a Two-Stroke in 1951

The following story comes from reader (and Chef from Hell) Paul Hughes, who writes, "I know you like a story! My mother and father were both bikers, and also my grandfather on dad's side, with a 1917 Levis it is told. My mother Philippa Cooper (maiden name) was a member of Eastbourne MCC and preferred to be called 'Phil'. In the '50s she met my father, Ifor Hughes, who was very keen biker with an Ariel Square Four and a Douglas ex-racer converted for road. In 1951 Phil embarked on a journey to Wales on a 197cc Francis-Barnett with the addition of her mother as pillion. Here is a small story written by her in period, with a few photos."

While plenty of women rode motorcycles in the 1950s, it was still socially unusual. In her modest way, Paul's mother was a pioneer of motorcycle travel for women, and showed considerable spunk on her journey. As did her mother, for doing the miles on the back of a rigid-frame popgun! The following is Philippa 'Phil' Cooper's account of her 1000-mile journey two-up on a two-stroke:

I have just been to North Wales on my Francis-Barnett (197cc) with my mother, who is nearing 70 years of age, as a passenger. My journey started on a Saturday, not a very promising one at first, but the sun did eventually shine. We left Eastbourne at 8.30 a.m., having decided upon Reading for lunch and Cirencester for the night. I had a small twinge of envy along the road to Reading when we passed a girl on a "Golden Flash" [the new BSA 650cc twin – ed.], but this was forgotten at Wantage, where we came upon the local weekly market. A statue of King Alfred looked on here — not entirely approving of two females on a motor-bike! The whole journey so far (Cirencester 153 miles) was very pleasant, good roads and little traffic.

We awoke In the morning to the sound of Church bells ringing a hymn tune right under, or should I say above our window. On through the beautiful Cotswolds with the lovely old stone houses and the Fosse Way which is lined by low stone walls. We arrived at Stratford-on-Avon for an early lunch, after which we went over Shakespeare’s birth-place. The house, especially the room in which he was born, seems to be in very good preservation, with low beams and walls made of clay and straw. Later we saw Anne Hathaway's beautiful cottage. We spent the night in Kidderminster and, although only a further 89 miles had been covered, we were very tired, especially my mother. I expect this was the result of the previous day.

We continued on to Ffestiniog, our destination, over very desolate countryside flanked by mournful looking hills and mountains, and passed unheard of gates where old men are to be found waiting to earn sixpence by opening them. These old men live in extremely queer contraptions which they call their homes.

The journey ended here at Ffestiniog but the road from Bala is terrible — if you break down along here you are stuck for hours! The mileage so far is 348, and the cost 16/— (with a gallon of petrol in hand) — somewhat different from the Railway cost of £10. My mother travelled very well, a bit sore on the vital parts but she is definitely "broken in".

We then came upon a very quaint and rather eerie little place called Pontmarion where a very long lane led to the village and ended down at the seashore. At the beginning of the lane we found a notice advising visitors of a 2/— Toll further on "so turn back now". We went on, however, but found no Toll and I am still wondering if this was really true or just an excuse to deter visitors, as the village was deserted. The buildings were very tall and bore very queer figure paintings on the walls, which seemed to leer at you. I also noticed a nice, but again queer petrol pump. Adorning the top of this was a lady's head carved in wood and also painted. The village was so quiet and deserted that it seemed to be "out of this World". I could learn nothing about this place but am still very intrigued.

We came back through Bangor, viewing Ogwen Falls through the Nant Francon Pass. By this time, unfortunately, it was raining hard but we joined other enthusiasts getting wet inside and out at a tea-stall overlooking the Waterfalls.

Wales gave us one beautiful day so we made for Snowdon and took the little toy train to the top (making mother the excuse for not walking!). The train took an hour but this was due to several stops for a drink and to await downward traffic. There were many people walking who of course we passed, but I understand a man did beat the train this year. On the summit of Snowdon it was surprisingly warm and we could see for miles. Also we looked down on a wonderfully blue lake. There were many sheep grazing on the hillside of Snowdon and were very surprised to find them extremely nervous of the trains. Llanberis at the foot of Snowdon was looking its best and as the clouds were perfect for a photograph, out came the filter. We carried on to Caernarvon, viewing yet another Castle and the shores of Anglesey. Then on to the Menai Bridge and across it into Anglesey — just to say we had been. This really is a magnificent bridge and, I believe, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Back a bit, though, for a few words on Lake Vyrney, where the road was very narrow and twisting and not a soul to be seen for miles (let alone a petrol pump!) except numerous livestock darting backwards and forwards across the road. A baby rabbit, which I just missed, rather frightened me as he seemed to pop out from nowhere. Fortunately for me, however, he popped back again. We reached Worcester at last after passing through the fascinating black and white town of Ludlow, and, having done a record mileage of 160 (going 20 miles out of our way) weren’t we glad to find a bed. Before we left Worcester, however, I found some extra energy and climbed the 237 steps to the tower of the Cathedral. The view was magnificent and I took an aerial photograph.

My office pals, I might add, quite expected me to return home in an ambulance, due to the fact that I have only recently recovered from a nasty accident on my motor-bike. The mileage covered was 939, costing £1. 14.81/2d in petrol and oil, doing 104 m.p.g., and our expenses were £13.10.0. each [that's about $160 each in today's money - a very inexpensive week's holiday! - ed.]

The Ultimate Old Bike Test - 2012 Cannonball

Originally published in Cycle World Sept 13 2012

The 2012 Cannonball proved the toughest vintage motorcycle rally I've ever attended, as well as the most fun. How can that be? I entered the Motorcycle Cannonball Endurance Run - as it's officially called - a whim in January 2012. The urging of a stranger over dinner in Las Vegas convinced me, despite it being well after the entry cutoff date. Perhaps the odd circumstance of my own Cannonball ride was a warning, as most riders spent years preparing their machines for the ultimate vintage bike test, as the first Cannonball proved to be in 2010. After only a month's preparation, my ride was a brief and glorious 4 days through the Rockies - the most scenic roads on the trip, luckily (read it here in Cycle World).

Is The Cannonball Expensive?

And how much does the Cannonball really cost? Here's information you won't get anywhere else; an honest accounting of the expenses and sponsorship for a Cannonball run. Team Vintagent is in the USA, so I can only speak to domestic entries; I had 3 souls in the team; myself, van driver/Vintagent manager Debbie Macdonald (who drove to New York and back!), plus Susan McLaughlin, my photographic partner for the 'wet plate' images taken across the country. - check out our website MotoTintype. I spent ~$4500 completely rebuilding my ca.1928/33 Velocette Mk4 KTT, which included parts (mostly from England) and some machine work, although vintage stalwart Fred Mork built my crankshaft without charge, as a sponsor and friend. Thanks Fred!

Freedom Means Truckin' On His Trike

From The Phoenix Gazette, August 30 1973

by Sarah Auffret

Gary is used to the stares and double takes he gets when he goes trucking on the streets of Phoenix. The 24-year-old Vietnam veteran is a double amputee, and his big-wheeled trike is thought to be the only one in the world with complete hand controls, power brakes, and automatic transmission. “Roth said he considered it a challenge just to build a bike like this,” said Gary who contacted the California designer as soon as his 15 month stay in a VA hospital in El Paso ended last year. “I do a lot of short trucking around town in it just to get out and go riding. I take it up to the lake too, but no long excursions yet, because it's hard to carry my wheelchair and I'm still getting used to my legs. Riding a bike is a sense of freedom you can't put into words. With the wind blowing in your face you could ride all night. Maybe you'll meet another biker and just ride. You don't have to talk. You've got a common bond.”

During the long period of convalescence and therapy at the hospital, Gary learned to drive a car with hand controls and began returning to Phoenix once or twice a month to watch the big drag races he had once participated in. He thought his own biking days were over. Then a friend brought him a magazine about trikes. He realized his limitations weren't as great as he thought, and soon afterwards he contacted Roth.

Gary's eyes sparkled as he talked of working with friends on putting together cars, tinkering with motorcycles, racing. He's a photography buff who takes pictures at all the drags; he also lifts weights and participates in archery. Though he's sick of hospitals, he admitted hopes of being a doctor someday.

For more on the First International Motorcycle Art Show at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1973, stay tuned. The clipping was provided by the Phoenix Art Museum, from their archives. (Additional photos used here are courtesy Mike Vils and the Roth Family Archive)

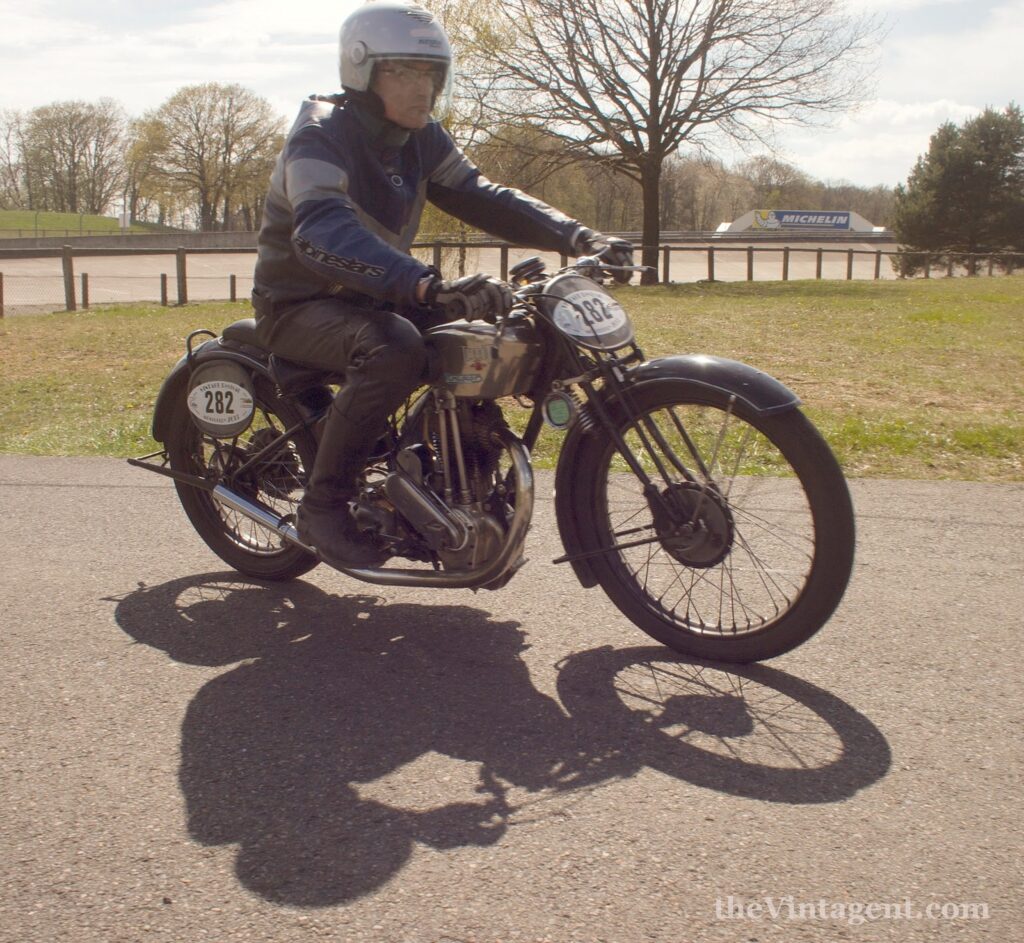

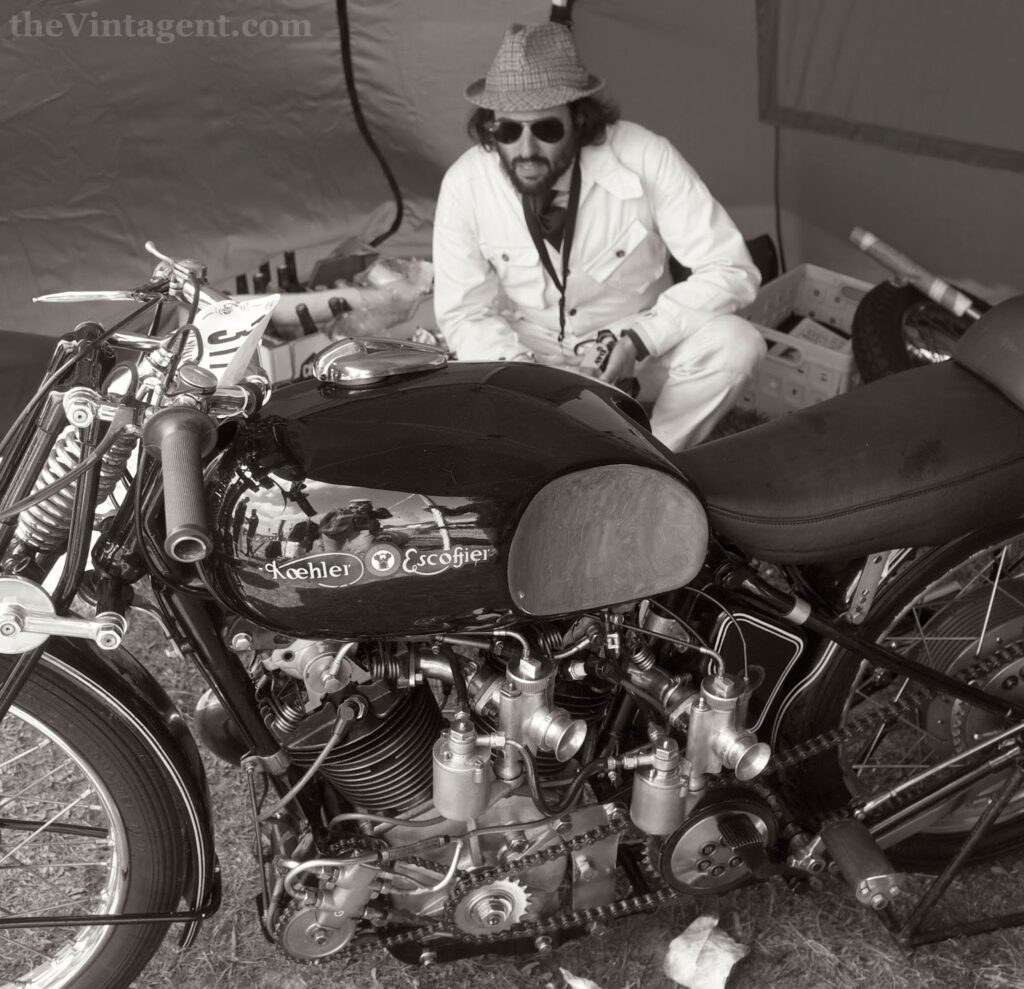

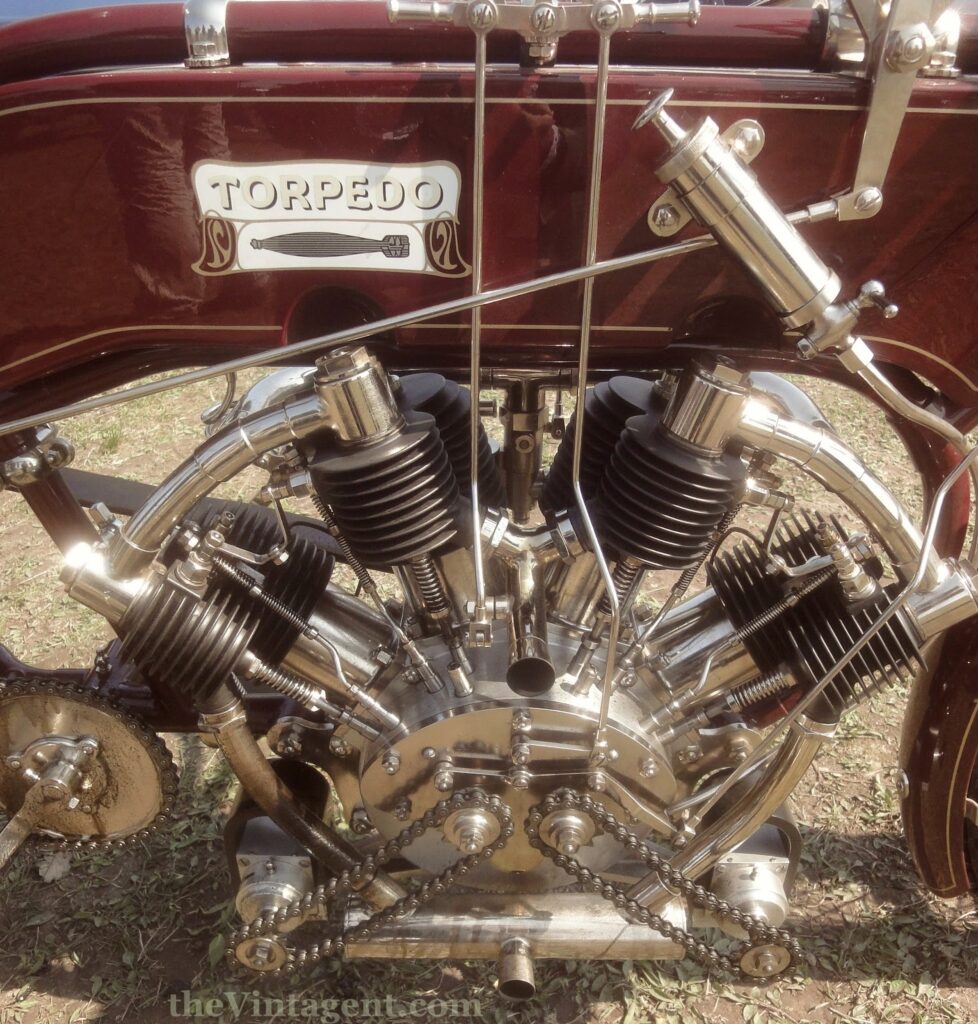

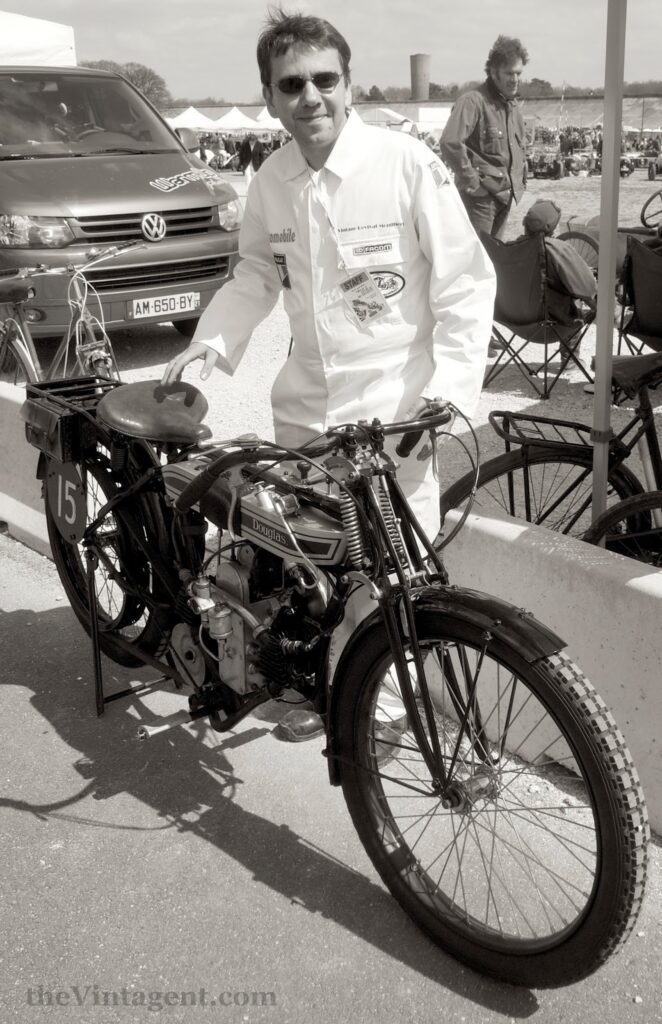

100 Years of Montlhéry: VRM 2024

Rumors have swirled for years that the Centenary of the Montlhéry autodrome, organized by Vincent Chamon and his team at Vintage Revival Montlhéry (VRM), would be the last. Those who know the magic of this august racing circuit, a bowl filled with the ghosts of racing past, quickly submitted eligible pre-1940 racing cars and motorcycles, with priority given to vehicles that had raced at the track in its heyday of racing and record-breaking. And so they came: a bumper crop of incredibly rare and storied vehicles, many only read about in magazines and books. Plenty of applicants were turned away to make space for the best of the best, whose owners had taken pains to bring over 500 of their machines not for show, but for go.

The Quail: A Watersports Gathering

We'd avoided it for 14 years, but finally the rain came, and made up for all those sunny Saturdays (and Fridays for the Quail Ride) by dumping an inch and a half of water in two hours onto the motorcycles at The Quail: a Motorcycle Gathering, to use its official name. Readers from anywhere but California will roll their eyes, as events get rained on in most of the world regardless of the season, but recent climatic changes mean we no longer get 'rain' here; we get 'atmospheric rivers' that dump with tropical fervor. As some wag once said, 'motorcycles don't melt in the rain', and well over a hundred enthusiasts parked their precious survivors on the lawn regardless the forecast, and stuck around for the duration.

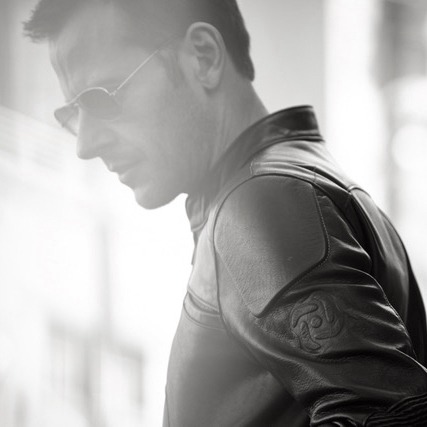

The Motorcycle Portraits: Gordon McCall

The Motorcycle Portraits is a project by photographer/filmmaker David Goldman, who travels the world making documentaries, and takes time out to interview interesting people in the motorcycle scene, wherever he might be. The result is a single exemplary photo, a geolocation of his subject, and a transcribed interview. The audio of his interviews can be found on The Motorcycle Portraits website.

The following is a portrait session with Gordon McCall, the founder of The Quail, a Motorcycle Gathering, the McCall Motorworks Revival, and the The Quail, a Motorsports Gathering. Gordon is brilliant at hosing a vehicle show that feels like a party. Gordon basically created Monterey Car Week, after decades of working with the Pebble Beach Concours, then branching out on his own to create something more fun. David Goldman caught up with Gordon in Carmel Valley on January 21, 2022, and asked him a few questions about motorcycling: the following are his responses:

My name is Gordon McCall, we're here in Monterey, California, where I'm a lifelong resident of the Monterey Peninsula. I'm CEO of McCall Events Incorporated, I'm the co-founder of the Quail, a Motorsports Gathering, as well as the Quail, a Motorcycle Gathering, which takes place annually at Quail Lodge and Golf Club. And I'm also responsible for McCall's Motorworks Revival at the Monterey Jet Center, held each August.

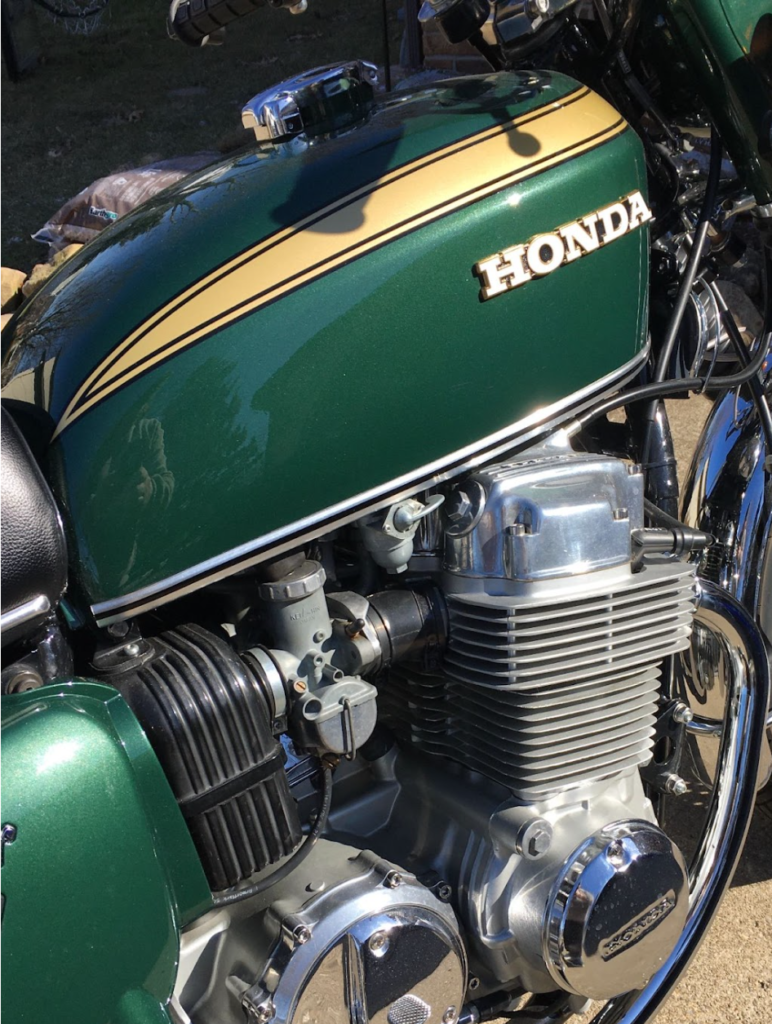

How I got started with motorcycles is really simple for me to describe. It happened at a really early age: Cycle World magazine was a big influence on me, and when I turned 14, I saw an ad for a Honda CL90 in the local newspaper, and I thought, you know, I need to sell my 10-speed and buy a motorcycle. Never ridden one, didn't know what they were like to ride, but I knew I had to have one.

That Honda CL90 that I bought when I was 14 lit the fuse for me with motorcycles. As far as I'm concerned, I mean, I think of that bike every day, I get to look at it every day, I still own it. I'm in my 60s now, so it's been a while, but that motorcycle taught me everything. It taught me how to work on motorcycles, how to ride motorcycles, how not to get in trouble, how to push the envelope and the rules a little bit.

My parents didn't know I had it. I couldn't get in trouble, or else the gig was over. So it turns out it's a pretty common problem, or story, I should say. That motorcycle has led to, gosh, I don't know how many motorcycles I've owned in my life, but I can't get enough of them, and I ride, not every day, but I ride today like I did when I was 14.

Motorcycling has led to so many adventures in my life, and has enabled me to meet people that I know for a fact I would have never have met without an interest in motorcycling. It's such a common denominator on so many different levels. It's such a personal thing, you know, you can't fake it on a motorcycle.

You either know how to ride, or you don't. There's no posing, for lack of a better description. It's authentic people with authentic passions that are into it for, basically, we're all into it for the same reason, the independence, the freedom. Again, it's something that I share with the people that I've met. I just feel grateful that I have such an interest in two wheels, and have had the opportunity to meet other people with the same. It's pretty remarkable.

Well, motorcycling means absolutely everything to me. By profession, I'm technically in the car world, but motorcycles have been a big part of my life, long before cars were, at a very early age, earlier than when I had a driver's license. What motorcycles have taught me is priceless in my book. Not only the people I've met, but also the skills I've acquired, and the determination I've required. There's nothing more frustrating than being on a motorcycle that has a mechanical issue, and you're out in the middle of nowhere. You better figure it out, or else you're not going to get to there. I credit all of that back to motorcycles.

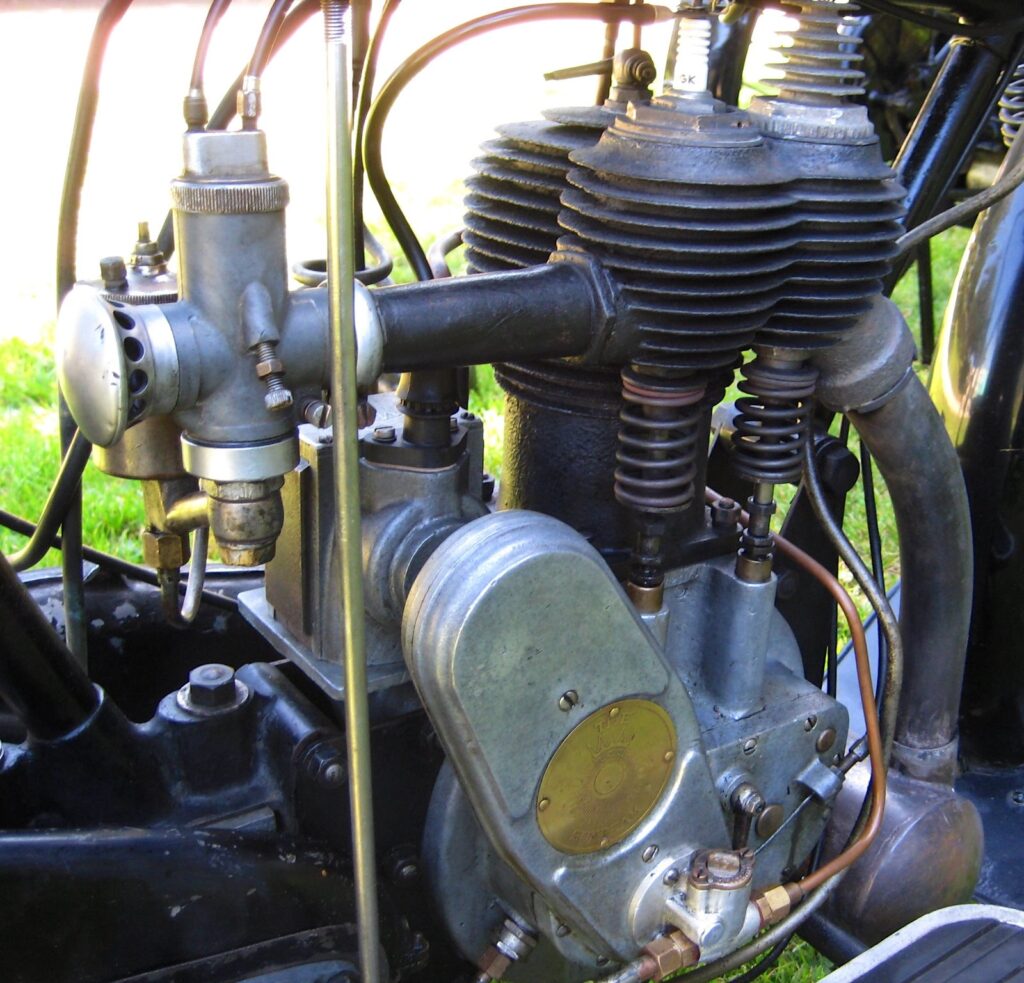

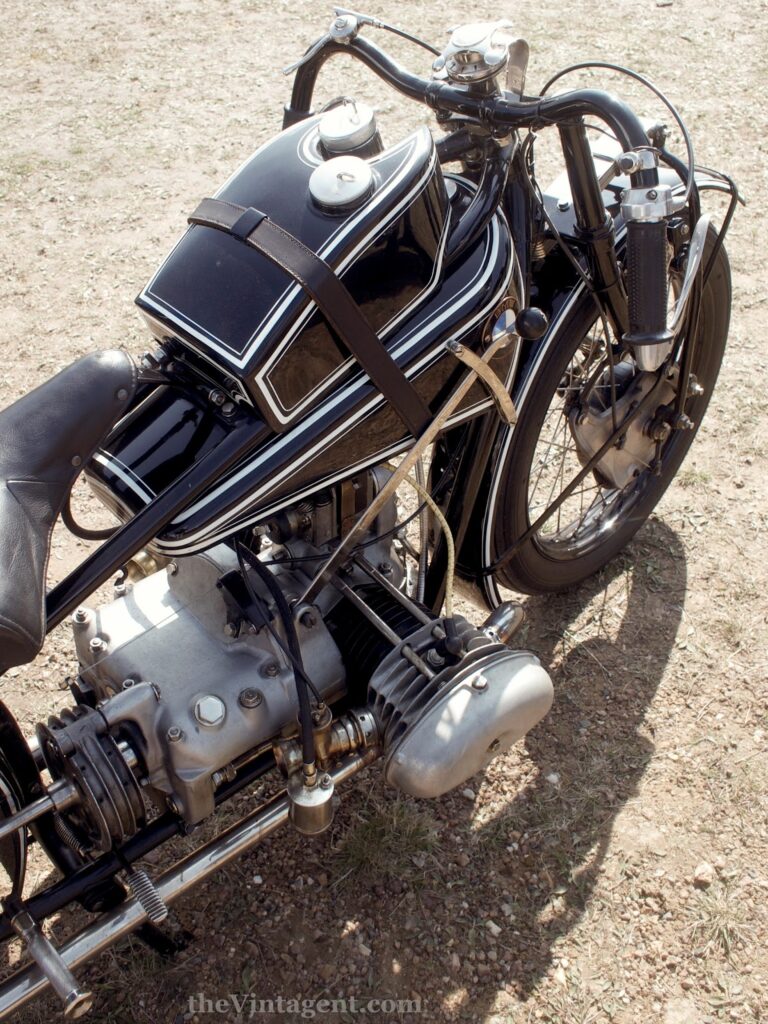

Road Test: Sunbeam Shoot-Out!

1924 Model 5 vs. 1925 Model 6 Longstroke Sports

[Mar 24, 2008]

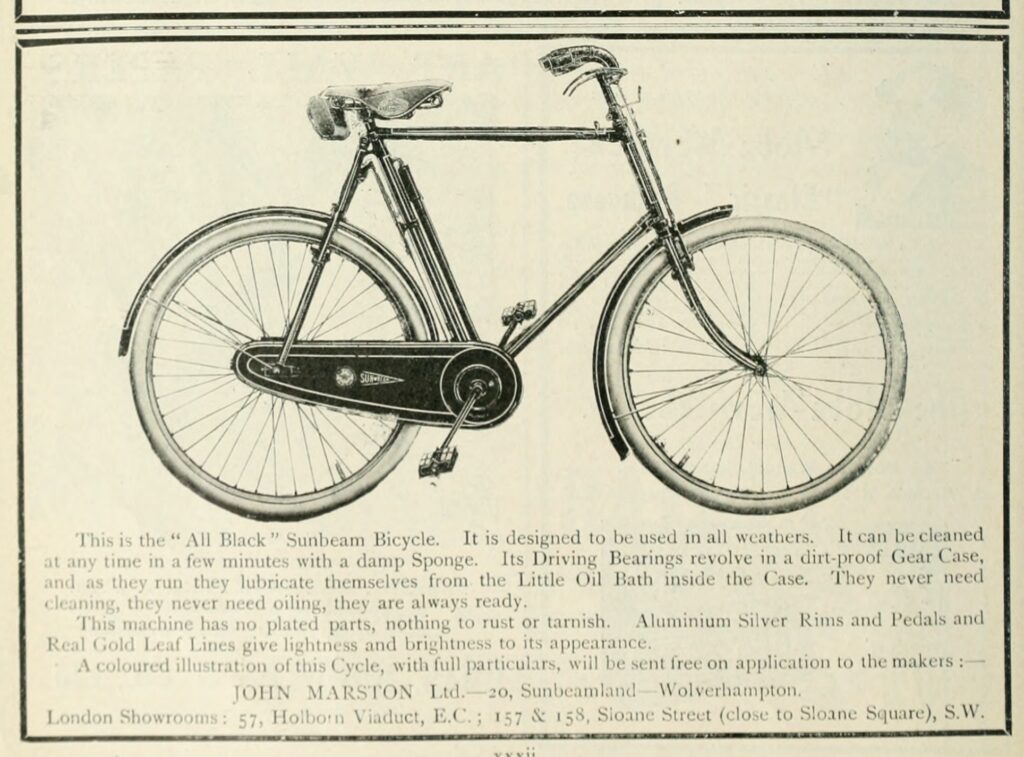

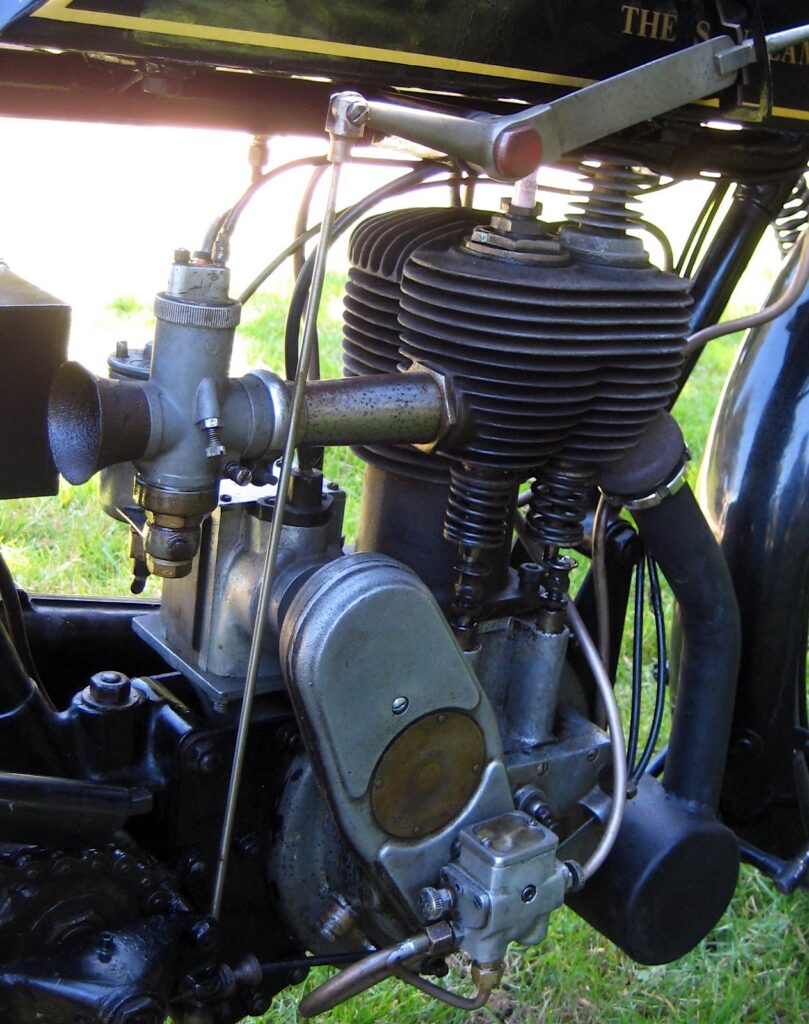

Sunbeam motorcycles were built by John Marston Ltd. starting in 1912 in Wolverhampton, England, as an outgrowth of Marston's highly successful Sunbeam bicycle business. Marston began his career in 1851, manufacturing 'japanware'; glossy enameled home accessories and furniture with a luxurious black or red finish and gold leaf accents, modeled after traditional Japanese lacquer ware. Japanware was all the rage in the late 1800s, and in 1887 Marston took the advice of his wife Helen and expanded his business into the booming bicycle trade. With over 30 years of experience in top quality paint and gold leaf, Marston's Sunbeam bicycles were renowned for the superb black and gold finish, and for the patented pressed-metal 'Little Oil Bath' chaincase that kept the rider's trousers clean. Sunbeam bicycles were expensive, but designed to last a lifetime, and many a centegenarian+ Sunbeam bicycle still retains its original finish in perfect condition.

What are they like to ride?

Since my 1925 Sunbeam Model 6 Longstroke arrived two weeks ago (March 2008), I've been curious to compare its character to that of James Johnson's 1924 Model 5 touring model. They're both sidevalvers from the mid-20's, with very similar running gear and mechanical configurations, from the same esteemed manufacturer; how different could they be?

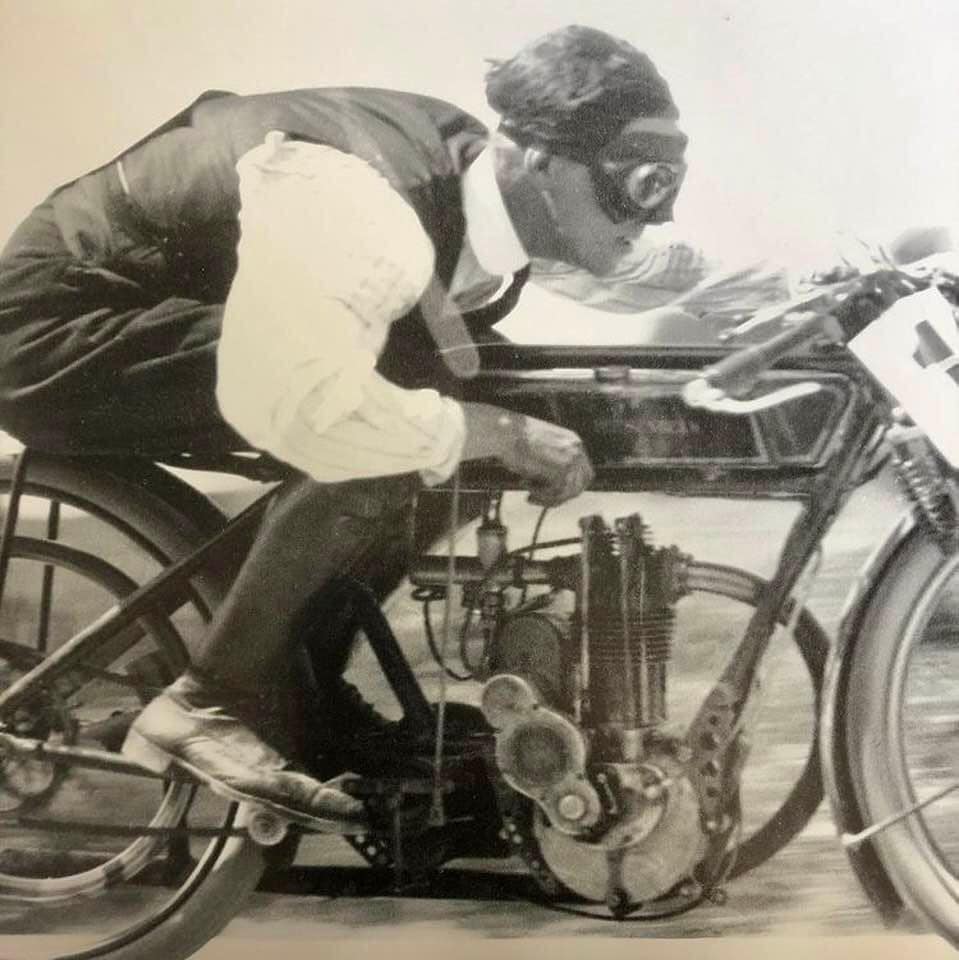

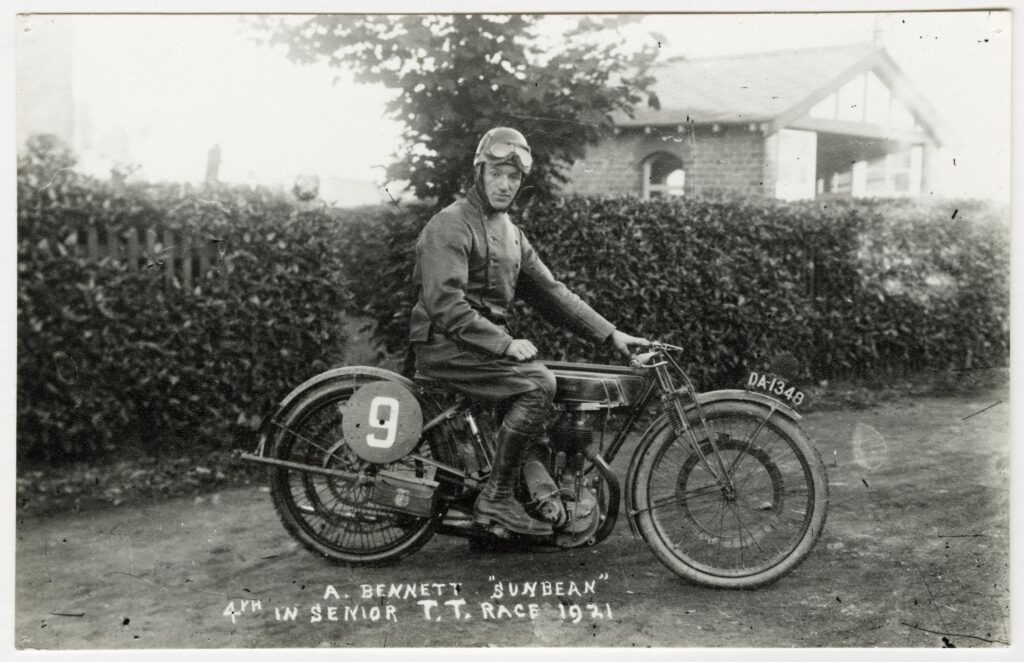

The Longstroke was developed from Alec Bennett's 1922 TT-winning (at 58.31mph) machine, and was initially known as the 'Model 6'. The 'Longstroke' name was added for 1925, to what would have been the 'Sports' model in that year, but was called the 'TT Replica' in 1923. How quickly things changed in those critical years between 1923-25, where the Longstroke dropped in esteem from TT Replica to a 'Sports' model in just 2 years. That's because Sunbeam added a new overhead-valve engine to its line in 1924, the Model 9 (and its variants), which sounded the death knell to the sidevalve as a racing machine.

James purchased his '24 Model 5 from British Only Austria about two years ago, and has spent considerable time in his workshop, making the 84-year old Sunbeam perfectly reliable. Now he feels confident in its mechanical soundness, and several long rides (including one 800 miler!) have borne out his conviction that his Sunbeam can be ridden as the maker intended.

The Motorcycle Portraits: Anne-France Dautheville

The Motorcycle Portraits is a project by photographer/filmmaker David Goldman, who travels the world making documentaries, and takes time out to interview interesting people in the motorcycle scene, wherever he might be. The result is a single exemplary photo, a geolocation of his subject, and a transcribed interview. The audio of his interviews can be found on The Motorcycle Portraits website.

The following portrait session is with Anne-France Dautheville, the first woman to ride a motorcycle solo around the world. David Goldman caught up with Anne-France on September 1 2023 in Paris. David asked Anne-France a few questions about motorcycling: here are her responses.

Please introduce yourself:

My name is Anne-France Dautheville. We are in Paris, in a little restaurant which is called Á la Ville d'Epinal, next to the Gare de l'Est, which is the railway east station, and it is the place where I give all my appointments, where I have my lunches, and it's my place in Paris. I'm an old lady now, going to be 80, and I have got an incredible life.

In fact, because I rode a motorcycle, and with this motorcycle I rode around the world, around Australia, around South America, and so many different places, traveling by myself, which is my happiness, considering I drive exactly like a shit, because I'm not a good driver, I'm not a sport woman, I just survive on a motorcycle. I started my life as a copywriter in advertisement agencies, and in 1968 we got huge strikes, even a revolution in Paris, and I had to walk. There were no metros, there were no buses anymore.

What was your first introduction to motorcycles?

So when the peace came back, I decided that I should be on my own, even if there was another revolution. I had no driving license of any sort, so I bought myself the only thing with an engine you could afford, which was a CB50. The first minute I sat on it, I said I made the biggest mistake in my life, and the second minute, anybody who would touch my 50cc would be dead.

And during my holidays, which I took always in September, I decided to go and see the Mediterranean Sea, which was something like 700 kilometers from Paris, and everybody in the agency said, “you're crazy, you go by yourself?”, yes, yes, yes, but it's dangerous, can't you go? And I made the best trip of my life, came back, and back through Alsace, which is the northeast of France, came back to Paris, and so during my years in advertisement, every weekend I used to jump on my motorcycle and ride to a place with a nice hotel, with good food, good wine, etc. And during this month of September, I used to drive around, and after a few years, I began to say that I'm very, very happy during 11 months of the year, and I'm so perfectly happy the 12th, so when I die, I will have only one twelfth of my life, which will be perfect, and I left everything, jumped on the motorcycle, and began traveling around the world, because I love traveling, I’m built for the travel, and writing, because travel without writing is only half of the problem.

Share a great story or experience that could have only happened thanks to motorcycles?

Which story for me, oh, it was a good one.

Let's go to 1975, the north of Australia, there is a gravel road which goes to Normanton, from Georgetown to Normanton in Queensland, I'm riding a 750cc BMW, it's my first gravel road, I didn't know how to drive this big motorcycle on the dirt road, so I start at the end of the afternoon, so there was a city in Georgetown, but no, there was no city, it was just a ring for car races twice) a year, but on the map it was like, okay, so I go to Normanton, something like 150 kilometers of gravel road, and the sun goes down, down, and when the light is not so hard, suddenly I see a huge brown frog jumping from my right, so I bump my horn, and the huge brown beast stops, and it was a kangaroo, and I stopped in front of the kangaroo, and I looked at him and said in French, you crazy man, and he looked at me and said, oh motorcycle that's talking, and in fact I learned that day, that when the kangaroo jumps in front of you, if you bump your horn, it stops to know where the noise comes from, so that was a very good lesson in my life.

What do motorcycles mean or represent to you?

What do motorcycle represents to me?, it's a machine, it's just an assembly of things that make it roll, it doesn't talk, it doesn't think, it's just a machine, but that machine allows me to go around the world, to go into places, and in fact it is the link between the nature and me, I mean when I am on a motorcycle, I have all the perfumes of the earth that grows from my nose, I didn't ride very noisy motorcycles, so I can hear sometimes hard crying birds, or things like this, if I go near the wood, I have that sort of freshness of the air, because of the trees, when I'm on a road, every little pebble on the ground makes a sort of a movement in the front wheel, and goes through my arms, so my whole body is alive, when I'm on a motorcycle, if I'm in a car, I'm just like a fish in a can, you know, motorcycle is a way to have a permanent discussion, exchange with the nature around you, and the fact, all my life I will remember the first shot of lavender I got when I was on my little 50cc in the south of France, I was on top of the mountain, and suddenly the wind brought me that huge perfect smell of lavender, it's still there, I wouldn't believe that, so perfectly, if I were on foot, because I go slow, with the motorcycle, I can pile lots, lots, lots of sensations, and this is happiness.

[Please read our previous story about Anne-France on The Vintagent: The Unstoppable Anne-France Dautheville]

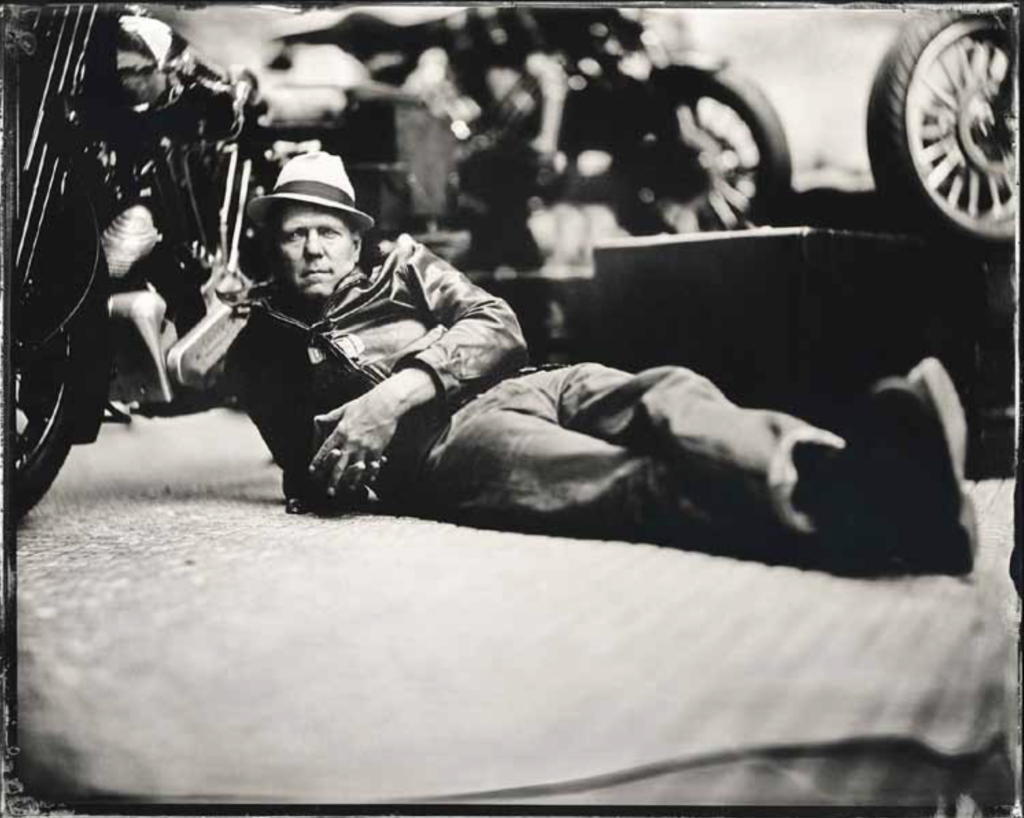

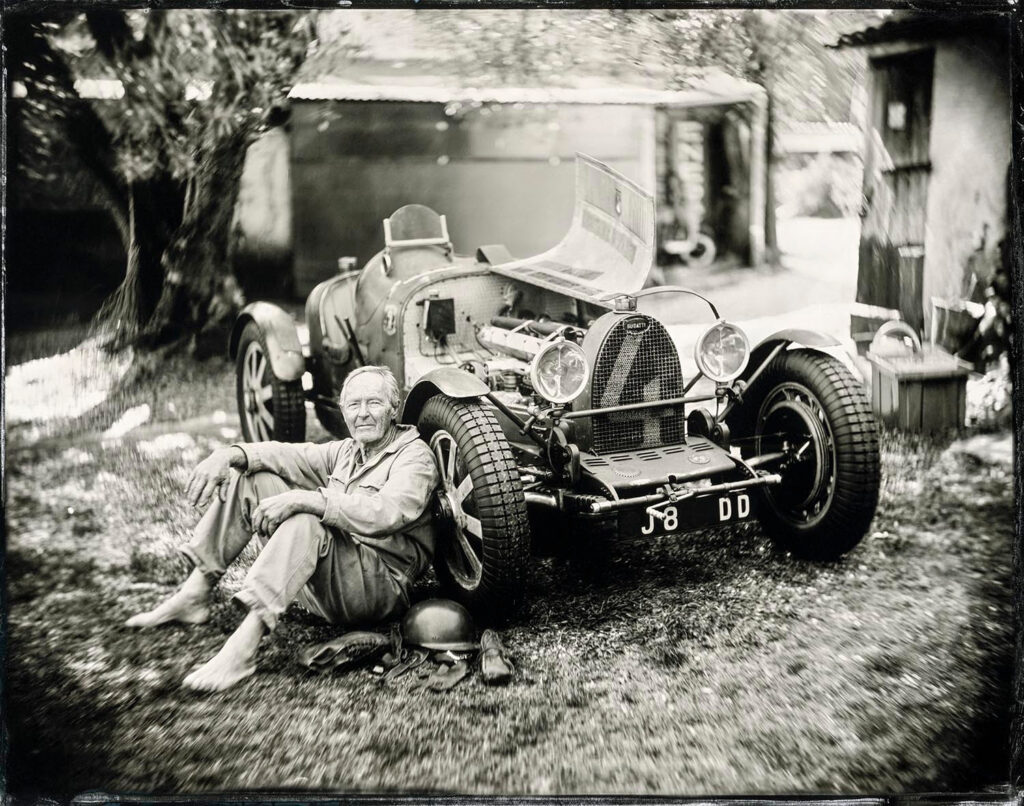

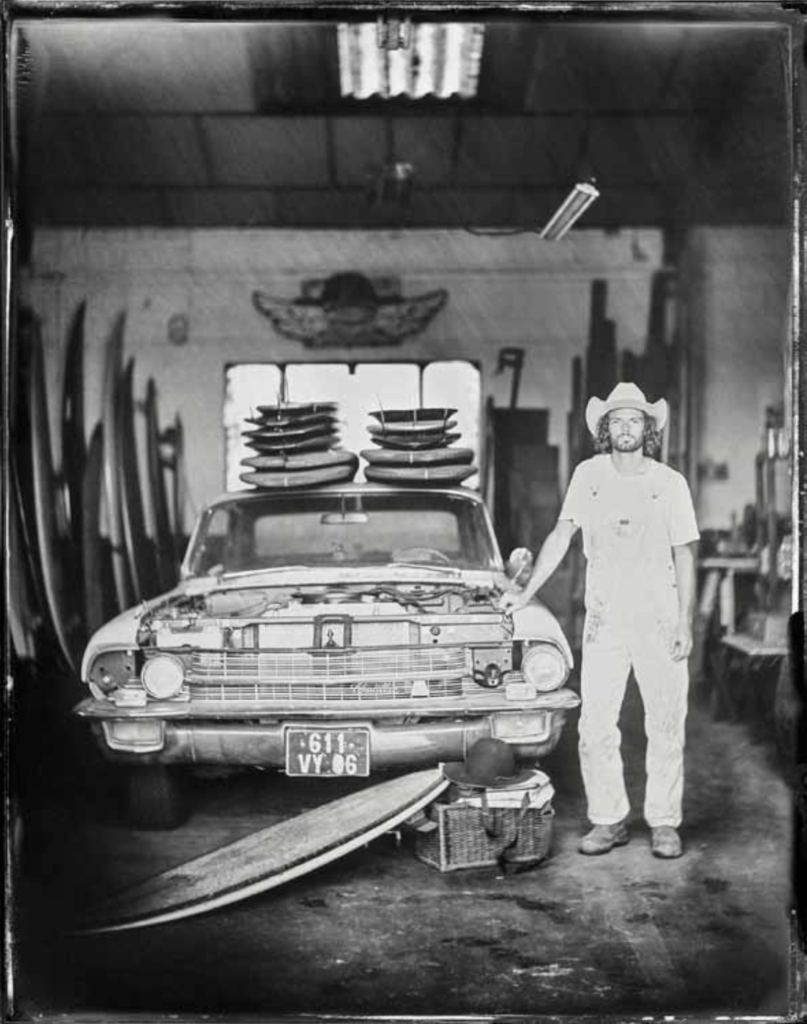

Art of Ride - Bernard Testemale

The wet plate/collodion photographic process was invented in 1850 by Frederick Scott Archer, only 11 years after the first fixed photographs were publicized using the Daguerreotype (Nicephore Niépce - who also invented the internal combustion engine) and Calotype (Henry Fox Talbot) methods. While these pioneering and technically difficult methods continue to be used by artists and enthusiasts today, the wet plate process proved far easier to master with more reliable results, and became the photographic standard for half a century. For astronomical photography, wet plate or 'dry plate' glass negatives continued to be used deep into the 20th Century, as the silver particles suspended in collodion or liquid gelatin are 1000x finer than is possible with 'film'. As a medium for artists, the wet plate technique was lost in the latter half of the 20th Century, until a few DIY die-hards dug into old books, ordered the basic chemistry (collodion, ether, grain alcohol, iodine and bromine salts, silver nitrate crystals, sodium hyposulfate, ferric nitrate, acetic acid, etc.), and re-learned what every photographer in the 19th Century knew by heart. Hats off to them.

Wet plate photography has been a peculiar fascination of mine since I saw an exhibit of 200 original 'Nadar' portraits in France, back in 2010. The Jeu de Paume photography museum had recently taken over the Château de Tours, and its walls were covered by 8x10" albumen prints of the most interesting characters in Bohemian France in the second half of the 1800s. These included writer Victor Hugo (Lés Miserables), actress Sarah Bernhardt, composer Franz Liszt, painter Gustave Courbet, writer Alexandre Dumas (Three Musketeers, Count of Monte Christo, etc), poet Charles Baudelaire, anarchists Mikhail Bakunin and Piotr Kropotkin, futurist Jules Verne (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, etc), sculptor Auguste Rodin, writer/feminist George Sand, explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza (whom I wrote about here)...basically anyone who was scandalous and brilliant in Paris from 1854-1910, when a Nadar studio portrait was simply necessary.

From Bernard Testemale:

"Art of Ride is the culmination of 10 years of photographic work: a voyage along the paths traced by pioneers of the artistic expression of wet plate photography, such as Gustave le Gray and Felix Tournachon, known as 'Nadar'.

In the world of photography, as in that of antique vehicles, some are vintage and others are modern. For years I have been fascinated by 19th-century photographic techniques, and I use the original wet collodion process: a technique that has enabled me to produce extremely fine images. These black-and-white shots, with their infinite nuances, provoke an immediate flashback to the past, releasing an emotional charge that is as unique as it is unpredictable.

Support Bernard Testemale's Art of Ride here.

Vintage Revival Montlhéry 2013

It is hands-down the best combined car/bike event I've ever attended, whether static or track, concours show or oily-rag festival, because it includes all of that, in the most compelling venue possible, the only original autodrome still in use from the early days of motorsport. The Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, to give its full name, is situated only 40 minutes south of Paris, yet feels of another world and another time. Currently owned and used by a consortium of car manufacturers (for testing), the 2.4km oval was originally designed to handle racing cars of 2200lbs, moving at 140mph; having traveled over 130mph (in a modern rally car) on the banking, I can assure you the track is in no danger from such abuse, only the car itself, and its madly bouncing passengers. While not as bumpy as Brooklands, Montlhéry is still a concrete track with expansion joints and decades of shifting movement, and the faster you travel, the harder the hammering.

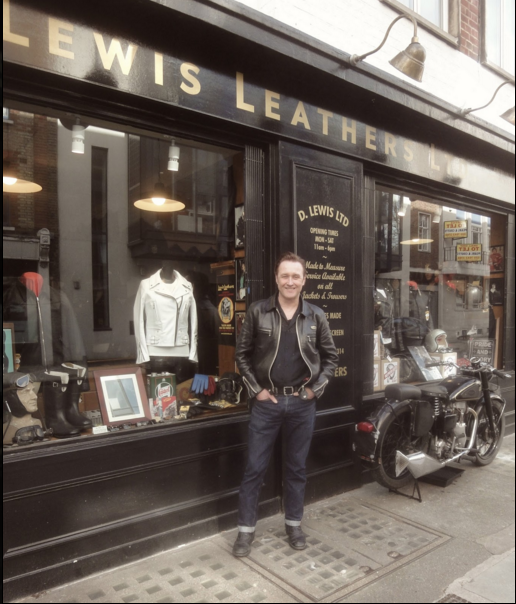

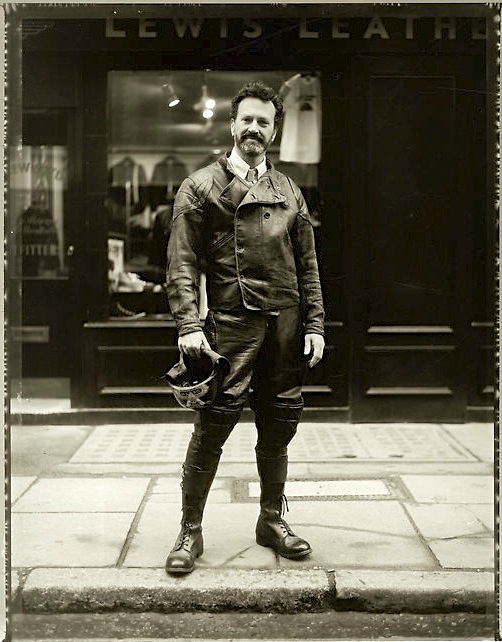

A Visit to Lewis Leathers (2013)

On a recent (Spring of 2013) whirlwind trip to London and Paris, I had a chance to catch up with Derek Harris, proprietor of Lewis Leathers, the oldest motorcycle-clothing business in the world - founded in 1892. Derek is a breath of fresh air as proprietor of an internationally recognized 'brand', and the very opposite of today's capitalist-opportunist-vultures who snag a dead name, creating Franken-brands stitched up from skins of the 'cool' dead, in the feverish pursuit of money money money. (Ask me how I really feel).

Top Ten Bikes at Mecum 2024

Motorcycles, how do we love thee? Well, thousands of us are willing to sit in an indoor rodeo arena in Las Vegas for days, listening to the drone of a professional cattle auctioneer's callout as hundreds of motorcycles pass under the hammer every day. 2024 is another banner year for Mecum's Las Vegas mega-auction, with over 1400 motorcycles ready to roll across the auction podium at the South Point Hotel and Casino, with the action commencing at 9am Wed Jan 24, and running till about 4pm on Saturday Jan 27. The amazing variety of motorcycles on offer come from individual sellers, professional restorers, and this year from a record 18 special collections, ranging from John Goldman's superb Museo Moto Italia collection to the Classic Motorcycles Austria collection to the Bud Ekins Family Trust.

The Vintagent team has selected their Mecum Top Ten for 2024 from the rabbit hole that is the entirety of Mecum's four-day list. We invite you to have a look for yourself, and if there's anything we missed that you think should be included, feel free to add it to the comments below, along with why it floats your boat. The following bikes float our boat, filling a variety of different neurotransmitter receptors, from funky and original, to awesomely historic, to groovy one-offs. Enjoy!

1957 F.B. Mondial 250 Bialbero

1938 Brough Superior SS100 with Sidecar

This ultra-rare, low-mileage 1953 Harley-Davidson Model KK is a one-year-only model and a factory Hot Rod. The odometer reads a believable 6,500 miles, and as a first-generation K model has a 45 CI (750cc) sidevalve V-twin motor that was revolutionary in the Harley-Davidson lineup. It was the first Harley-Davidson with both hydraulic telescopic forks and hydraulic shock rear suspension and was their first unit-construction V-twin.

The K model was Harley-Davidson’s answer to the British motorcycle invasion postwar, being significantly lighter and smaller than their Big Twin Panhead model, and intended to take over in Class C racing from the WR sidevalve model. The K model used the same bore/stroke as the old W series (2-3/4” x 3 13/16”), with a 6.5:1 compression ratio, with heavily finned aluminum cylinder heads to aid cooling. With a unit-construction crankcase, the K model saved space and weight and had a modern look, years before the British twins adopted the same idea. The standard K model Sports Twin produced 30 HP and weighed 400lbs, but the KK was a hotted-up model with a factory-installed ‘speed kit’ that included roller bearings and roller valve tappets, larger valves, ported and polished cylinders, and matching heads for better gas flow, including hot camshafts. By no coincidence, Harley-Davidson also introduced the KR model in 1953 as the factory Class C racer, and the expertise gained in tuning the new K model for racing was adapted in a slightly less fierce form to this roadster model KK: racing improves the breed, as they say.The KK Sport Twin produced 34 HP and was good for over 90 MPH, with very good handling and a modest weight making for a very sporting twin indeed.

Yamaha's Ascot Scrambler is a fascinating machine, a combination of the YDS-2 street bike and the TD1 production racer, with its own unique bits that make parts sourcing for this bike basically impossible. Yamahas were the 250cc engine of choice for Amateur class racers, as they were limited to that engine capacity for their first year of AMA racing, and Yamaha was the fastest engine available. Tuners and racers commonly put TD1 engines into special frames by Trackmaster, Redline, et al, which put Yamaha on the podium at tracks like Ascot Park, without the factory even trying.

Yamaha had sense enough to make their own dirt racer, and the Ascot Scrambler was result: a 250cc twin-cylinder two stroke with 35hp. The Ascot, introduced in 1962, used the aluminum cylinder barrels of the TD1 with slightly smaller intakes (24mm Mikuni carbs were used), combined with expansion chambers and wheels from the TD1, and its own frame. Production lasted from 1962 to 1967, and while it was a popular seller for racers, very few survive intact, and not many are in such good original condition like this bike.

Tiny cafe racers, like kittens and puppies, provoke the same response in all motorcyclists: they SO CUTE! And this Bianchi Falco is extra super cute, and seriously badass at the same time. With its elongated gas tank looking like Alien's motorchild, the clip-ons and humped seat, the blue metalflake paint job, and its rarity, make this Bianchi the micro etceterini cafe racer to have. It's got a single-cylinder 50cc two-stroke motor, and isn't a moped as it doesn't have pedals: it's a small motorcycle, and exquisitely designed.

I've seen this bike installed in the home of its owner, John Goldman, and immediately coveted it...and all the other crazy cool Italian Grand Prix racers and cafe racers in his collection. Much of that hoard is on sale in Vegas this January as the 'Museo Moto Italia Collection', which includes the largest private sale of F.B. Mondial motorcycles ever.

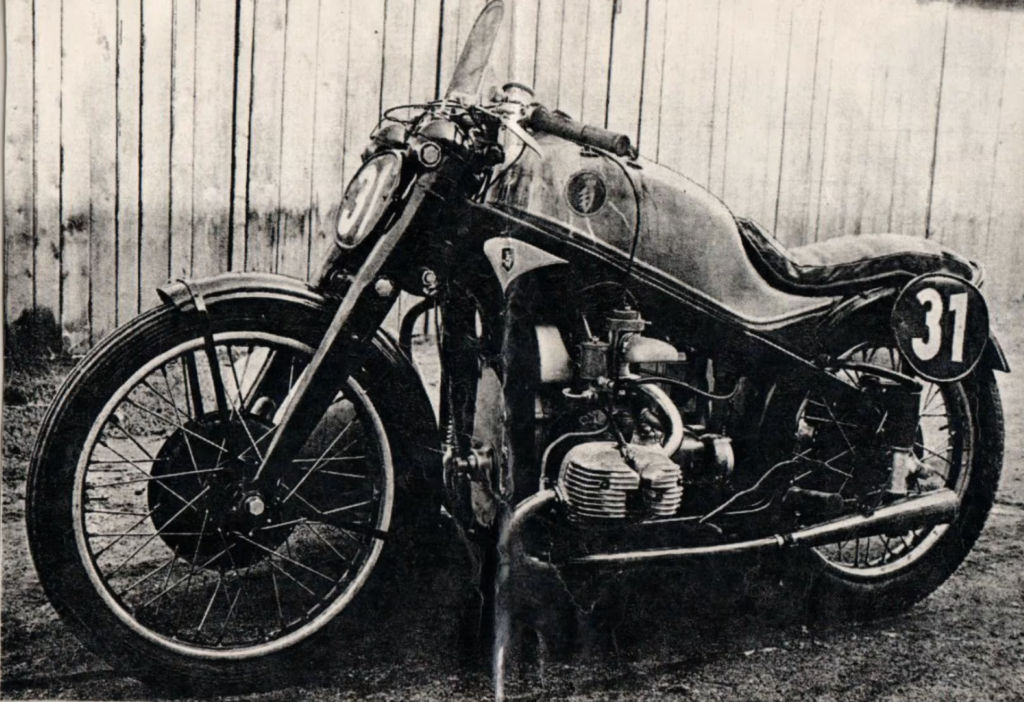

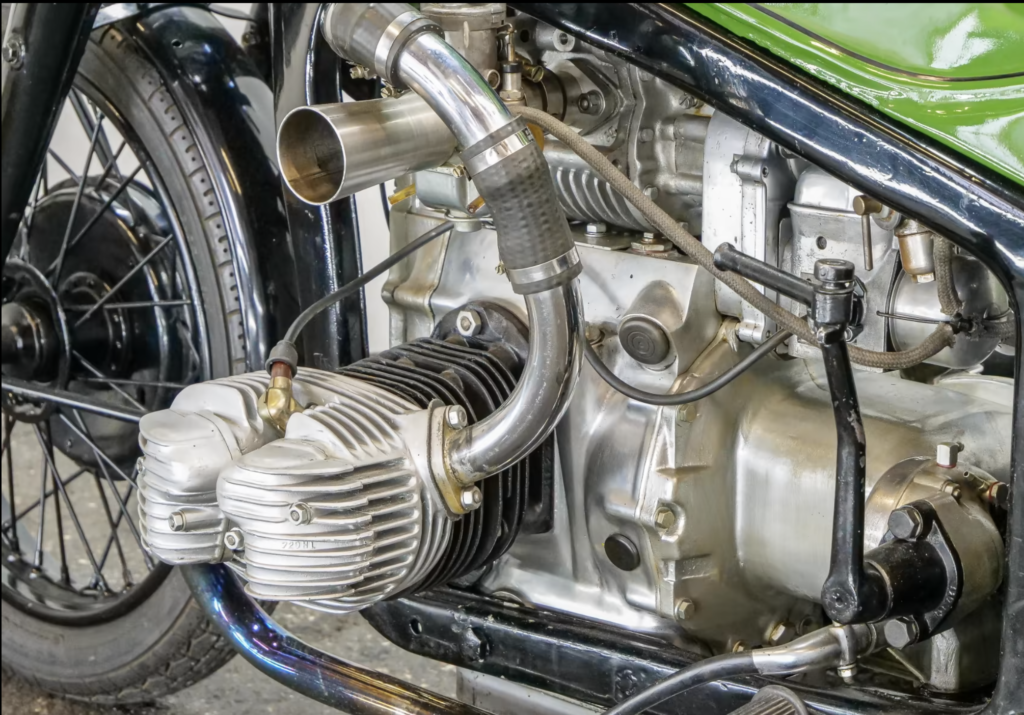

1947 Supercharged Zundapp KS600 Oskar Pillenstein racer

After WW2, Germany was banned from the Grand Prix circuit, but they still held motorcycle races, and their own German National Championship. Also, not being part of the FIM meant they could use superchargers, which were banned everywhere else. This remarkable blown Zundapp KS600 racer was originally built by Oskar Pillenstein with help from Zundapp's head of design, Richard Kuchen. Pillenstein promptly won the 1948 German Motorcycle Championship with it, setting a class record of 103kmh.

The KS600 was the continuation of Zundapp’s prewar engine, and the basis for the legendary Green Elephant KS601 to come. Its 600cc OHV motor normally put out 28hp at 4,800rpm, but the addition of a supercharger definitely gave a power bump. There are tons of factory racing bits inside and out, as this is a unique motorcycle, and basically a factory racing Zundapp. It was restored in 1987, and was on display at a museum for almost 30 years, but is now available to you.

The first of the legendary Indian fours were basically rebadged Aces, as Indian acquired that brand in 1927, and sold them as the Indian Ace Series 401, with a 77ci (1265cc) inline 4-cylinder engine. Initially the Indian-ACE was a parts-bin special, using up remaining ACE stocks, but the Four was changed over time to become a fully Indian machine. In the first half of 1928, the engine got lighter alloy pistons, pressurized oiling, and a new cam, giving it more power and reliability, and by August of 1928, Indian had redesigned the 4-cylinder to harmonize with the rest of its model lineup. Only the first-year Indian-Ace Fours used the leading-link front fork and frame seen here, which are pure Ace items. These early Indian-Ace Fours are coveted for their rarity and unique style, and clear connection to the father of the American Four-cylinder, William Henderson.

I've known Ken Seavy for decades: he arranged the purchase of my Velocette Thruxton in 1989, after his boss at Good Olde Days got busted with 6 tons of amphetamines, and had to liquidate his amazing motorcycle collection. I've long known Ken was racing legend Art Bauman's nephew, and that he owned Art's old Kawasaki H2R 750, among other very rare bikes, but he never invited me to see his collection. In the 1980s and early 90s, the Kawasaki was at the nadir of its value, but Ken knew what he had. Finally, that mean green racing machine has come to light, and it's a beauty, with a presale estimate of $180-220k.

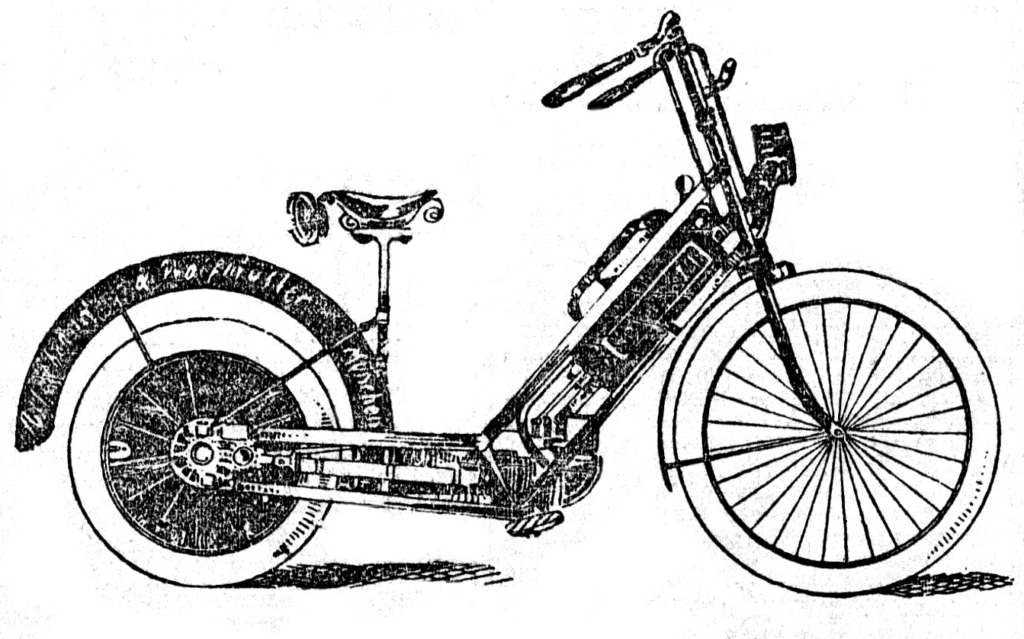

First Moto Cycle in Australia: 1896

The motorcycle is an old concept. The first recorded image of a two-wheeled vehicle with an engine dates back to 1818, and the first known functional motorcycle, Sylvester H. Roper's 'steam velocipede', dates back to 1869. Several other steam-powered motorcycles were built in France and the USA in the 1870s and 1880s, but the first motorcycle to be built on an industrial scale was the Motorrad built by Hildebrand and Wolfmüller from 1894-1897. Heinrich and Wilhelm Hildebrand were steam engineers, and the initial (1889) prototype of their Motorrad was steam-powered, but they teamed up with Alois Wolfmüller to produce a gasoline-powered version in 1894. One look at the construction of the Motorrad reveals its steam heritage, and makes it unlike any other motorcycle: the engine's cylinders have exposed connecting rods that act directly on the rear wheel hub, in the same manner as a steam train, making the rear wheel effectively the flywheel of the motor. A rubber strap helped rotate the rear wheel on the 'return' stroke, and can be seen laying on the ground in the illustration below. With no clutch possible in such a direct drive, the Motorrad is a push and go starter, with no bicycle pedals as with other early gasoline motorcycles, as the Hildebrand and Wolfmüller chassis had nothing whatever to do with traditional bicycle design.

The Moto Cycle: A Wonderful Invention

Sydney Daily Telegraph, March 26 1896

Yesterday afternoon the Cycle Austral Agency gave a public exhibition in George Street of the motocycle, which is causing such a great deal of public interest throughout the world. Since the advent of this machine in England, France, America, Germany, and other countries, it has caused an enormous amount of newspaper controversy. The machine has been attached to carriages and different kinds of vehicles, and many of the London and provincial papers have published illustrations purporting to show that in the course of a few years, carriages drawn by horses would be rarely seen. Already races have been held, for a few months ago a race took place from Paris to Bordeaux and back for motocycle, or horseless carriages, as some choose to call them, and it proved to be very successful. Fully 100,000 people witnessed it. A race has also been held in America. The Prince of Wales has had several rides in one of them, and the mail which arrived in Sydney on Tuesday brought word that His Royal Highness had ordered one, so that it is likely to become very popular.

The machine is to be exhibited at the Agricultural Show, and Mr. Henslow, on behalf of the league, last night concluded arrangements with Mr. Elliott, the manager of the Austral Cycle Agency, to give an exhibition of pace on the Agricultural Ground on April 25th, at the race meeting which is to be given to Mssrs. Lewis and Megson prior to their proceeding to England. The machine will pace probably Lewis or Megson a mile, and then will run 5 miles at its top speed, under the care of Mr. H Knight Eaton.

A few more photos with interesting details:

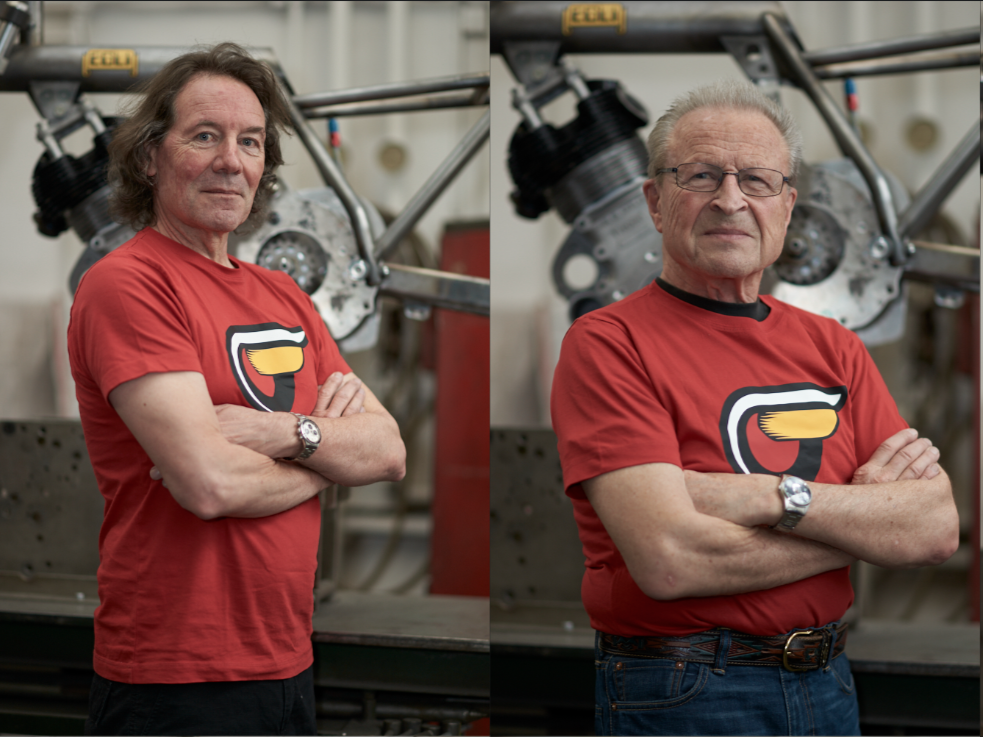

Egli Motorcycles Workshop To Close

The motorcycle business has never been easy, and even a famous name cannot ensure a future for a small factory. Alexander and Felicitas Frei purchased Egli Motorradtechnik AG from Fritz Egli in 2015, with high hopes to carry on with his legacy of building amazing high-performance cafe racers. This week, the Freis put out a press release stating they are shuttering the famous house of Egli:

There's a time for everything...

More than 9 years ago, Fritz W. Egli was looking for a successor for his Egli Motorradtechnik AG and finally found it in 2015. When we stepped in to continue the company at its location in Bettwil, our aim was not just to keep the workshop as it was at the time and to continue importing brands. We wanted to raise Egli to a higher level as a Swiss Motorcycle brand and also to build up a classic department which, in addition to the Egli range, would carefully restore vintage and classic motorcycles by hand.Our re-entry into the racing scene with our involvement in the IOM Classic TT was intended to be a further step towards revitalizing the brand. At the same time, we tried to bring the Egli-Vincent trademark back to its place of origin. Unfortunately in vain - the Vincent and Egli-Vincent brands were sold to a group in India [actually, the names were licensed by their owner many years ago - ed.].

After the presentation of the new Egli "Fritz W." in 2017, the idea of an Egli Motorcycle developed and manufactured entirely in Switzerland - including its own engine with road approval - became more and more concrete, until the starting signal for the new project was given in 2018 with a team of young engineers and qualified employees. The new Egli with a 1400 cc V2 engine is running, has already passed the first noise and exhaust measurements and has covered a considerable distance on closed roads. We have come a long way, but we are still too far away from road homologation and it will take a lot of time and additional financial commitment to overcome the final hurdles in the „forest“ of standards and regulations.

The world has changed rapidly in recent years - economically, politically and environmentally - and the requirements on motorized traffic are changing at the same pace. We too have now reached retirement age and have therefore decided to step back from daily business.

Over the past 9 years, we have had many great moments with customers, employees, business partners and friends. We were able to celebrate successes and also had to deal with setbacks - everything that is part of an exciting motorcycle life. We would like to thank you all very much for this. Without your support, many things would not have been possible. But everything has its time and so we will cease business operations at the Bettwil on November 30, 2023 and put the company into an orderly liquidation.

We are pleased and grateful that all employees have already found a new job or have decided to become self-employed.We wish you all the best for the future!

- Alexander & Felicitas Frei

For your additional interest: the following is an exclusive interview for The Vintagent with Alexander Frei, after his purchased the Egli name outright from Fritz W. Egli. Paul has long known Alexander's cousin, John Frei of San Francisco, via a long association with the Velocette Owners Club. John Frei’s grandfather was brother to Alexander's grandfather, and was watchmaker in Switzerland who emigrated to US.

Alexander Frei (AF): Motorcycles take over your life.

I started my professional career in the watchmaking industry; starting the traditional way with an apprenticeship as a micromechanic, then earned a microengineering diploma. When I met my wife Felicitas, her father owned a medical implant company, so I joined the business. When her father died his businesses were sold, with the last in 2000. Then I started a career in car racing, as more or less a hobby. At the beginning I raced Lamborghinis, then was a factory driver for Courage Competition, a French endurance racing team in the Le Mans series. I raced LeMans four times with the LMP1, and three times with and LMP2. Kevin Schwantz was racing the same LeMans team as mine, and Mario Andretti too, but a few years before me. Mario Andretti was old but still a good endurance driver – the cars were fast, but the materials were not always first class as they were short of money. You’d be going fast them boom, you waste time in the pits. I’m not as good a motorcyclist as car driver, but I’ve always had motorcycles, since I was 19 or 20. In 1982 my family went to Laguna Seca with my cousins, and saw Randy Mamola in Battle of the Twins racing, against Norton, Triumph etc. Kenny Roberts was still racing.

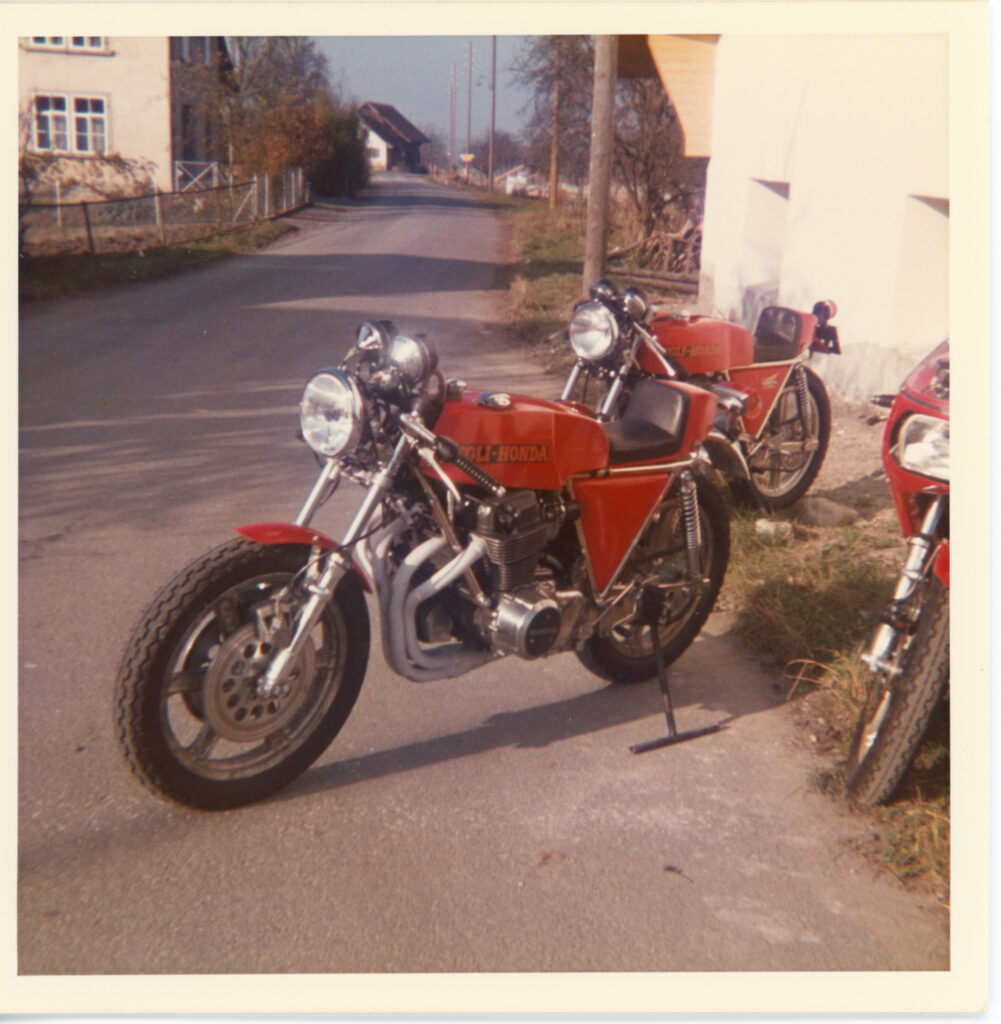

AF: One of my sons is 32 years old, he started as a car mechanic, then became a motorcycle mechanic. He worked for Harley-Davidson, and one said he’d like to open his own workshop. We discussed this, and he was looking for motorcycle brands to open his own dealership. One of the names was Norton, the other Royal Enfield, and the Swiss distributor was Fritz Egli, and they had a meeting. Of course I knew his name, I'd read about him, but didn’t go to this meeting. My son told me he’s selling his company, I said ok let’s have a look! I was fascinated about the whole thing. I realized of course for 25 or 30 years they hadn't built any motorcycles: they built frames and parts, and strange things like Yamaha Vmax tuning, but not real Eglis anymore. I started discussing with my son how he might start his dealership: I could buy Egli to restart some kind of motorcycle manufacturing, and also a restoration business. This was the initial idea, in the summer of 2014. I bought the Egli business on Jan 1 2015. I never thought I’d start a business again, certainly not in motorcycles. But when I saw the Egli company with such great history and bikes, I thought 'let’s try it, it can only break'. Otherwise the name is gone! I’ve seen this in the Swiss watchmaking industry many times, smaller shops breaking down, then a revival with external investors, but it's really difficult to do this.

AF: Euro3 vs Euro4 means much less noise, and pollution is much stricter, these are the two main factors, plus ABS and OBD now. The petrol tank must breathe through an active carbon filter, etc, which makes construction much more complicated. I’m a afraid instead of two wheels and an engine, there will be a lot more gimmicks to hide, which is no longer simple. In Switzerland we are still allowed to sell Euro3 bikes, but I think the rest of Europe cannot. For example in Germany, lots of bikes had a fire sale as they couldn’t pass Euro4. In Europe we can still sell Euro3 bikes now, all that were imported or built before 2016. So Egli is more or less in the last minutes… but we are so limited in production. They inspected the bikes before the end of the last year, and we were not allowed to build more than 6, but for me it’s ok. Everything we do in the future must pass Euro4, and in 2020 will be Euro5, and it’s not clear what will change – definitely more regulation; less noise, less pollution, and so on.

AF: I don’t know, maybe we have to look at electric bikes.

It's not possible to use older engines for manufacturing. For example, the Godet-Egli-Vincents have to match Euro3 too, so he can’t use a newly manufactured Vincent engine, it's only possible for an old bike restoration: you cannot start new production with an old engine. You’d have to design a new Vincent motor, and even Fritz tried - I saw the plans, he looked for financing, the approached bankers, but couldn’t raise the money. It must have been in the 1980s, a Vtwin. We will have to tackle the Euro4 regulations, from the structural side the bike is not a problem, but the ABS is not so easy to get. I was in discussion with motorcycle companies who were willing to sell us an engine, but the problem is with Bosch who has the patents for ABS, but they don't sell a full package with all the electronics. And that's very costly to develop; we would have to pay them to develop the software for our bikes, and with only 6 or 12 bikes its not workable. Thierry Henriette had the same experience with the new Brough Superior; ABS makes everything more complicated and expensive. Fritz Egli was in the workshop many times saying how difficult it is now, and how easy it was then!

AF: If one of our customers wants to race our 6 new bikes, we have tuning kits, exhausts etc, but of course that's not street legal. We’re a bit into classic racing, we race a Godet 500 Vincent at the Classic TT, with Horst Zeigel riding for us, and we’ll go back this year. I think we’ll do another bike like Egli did in the past, in Switzerland we have one or two classic races, and there are 500 Honda motors available. For now that’s enough to put in a foot, but not jump wholly into classic racing. Plus, we've decided to show a 750 Honda Egli at the 2018 Concorso Villa d’Este, so see you there!

[All of us at The Vintagent lament the closure of Egli Motorcycles, and wish all parties the very best in future projects. The Egli name will surely live as long as motorcycles are remembered.]

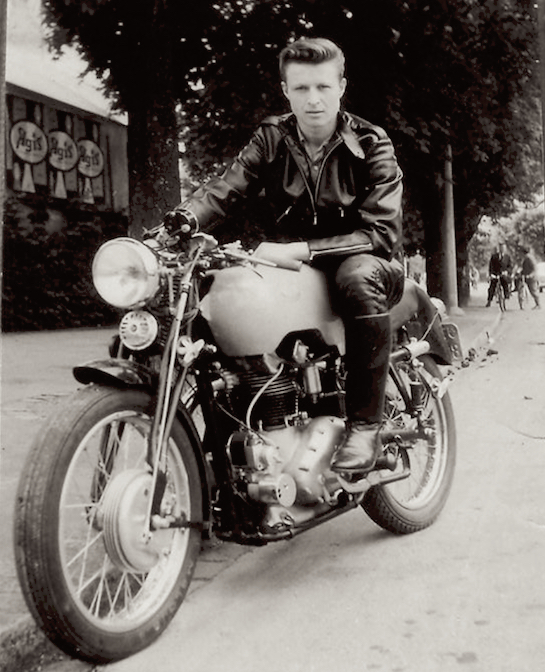

Do Cafe Racers Dream of Electric Starts?

By Scott Rook

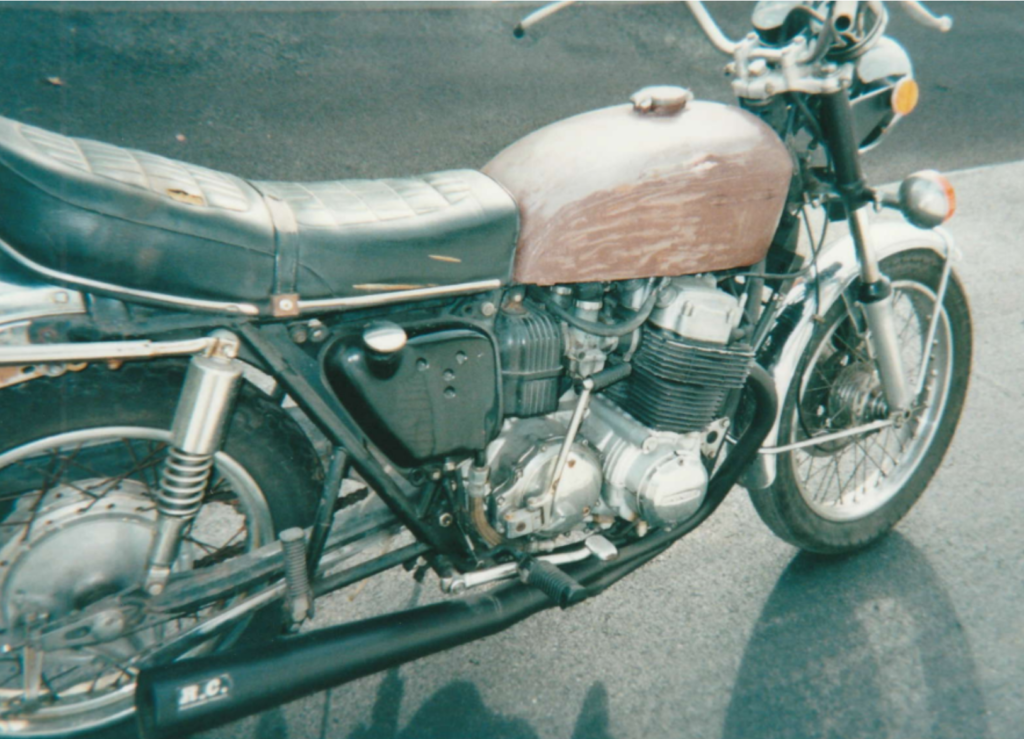

Being a child of the 1980s, I never knew a time when fast bikes on the showroom floor didn’t mimic the factory's race bikes. Kawasaki had the Ninja and Honda had the Hurricane. [Shameless plug: read our history of the cafe racer, 'Ton Up!'] The bikes appeared on magazine covers in the school library that all my friends drooled over in study hall. When I got interested in vintage bikes in the 1990s, the idea of an old street bike that was kitted out in race trim took hold: a cafe racer. The Honda CR750 was the bike that did it for me. Cycle World ran a story about Dick Mann and his Daytona-winning Honda CR750 from 1970: someone built a replica and was racing it at Daytona in the AHRMA series. The factory CR750 racer looked nothing like the old CB750 that I'd owned. The Honda had been replaced by a 1979 Triumph Bonneville, but when I saw the CR750 in the magazine I thought, I could build that and ride it on the street. After all it was just a CB750 underneath that root beer colored fairing, and CB750s could be found cheap in the early 1990s. This was my cafe racer dream. I started making spreadsheets of parts and searching the internet with my dial-up Internet connection. I perused the newspaper looking for any old cheap CB750. I found one; a non-running K1 for $250. My girlfriend (who would later become my wife) went with me to check it out. We stopped at U-Haul on the way and picked up a motorcycle trailer just in case. The bike was rough. The cases were cracked but most of it was there, and it had a title. The 1971 CB750 came home with me that day and has been with me ever since.

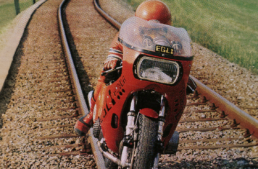

I had loved the process of building my Dunstall Honda: it was full of the anticipation of riding a bike that belonged in a different era. The Dunstall Honda was something different, like a lost treasure that the world had forgotten. And I brought my cafe racer dream to life in my garage. The realization was exhilarating, but the ride was terrible. I remembered my old CB750 and how it did literally everything: I rode it on grass while learning to ride a motorcycle, I rode it to school and took it on camping trips with my friend on the back. That old CB750 took me and my high school girlfriend everywhere. The Dunstall Honda did nothing well other than go fast and look great. I couldn’t take it anywhere without experiencing pain. Maybe that is how beautiful strange things from a different era are supposed to be. They have to extract a toll from their owners for their existence. Not just a financial cost, but actual pain when used as intended. I wanted to like riding the bike, and gave it my best, but never really enjoyed it. So I changed clip-ons and played with different hand grips, and tried to make it even more cafe racer by adding a boxed swingarm and rear Hurst Airheart disk brake conversion. I changed the wheels to the even more rare Henry Abe mags, all in an effort to love the bike I had built. None of it worked. I rode the bike once or twice a summer for many years. I polished the aluminum covers and waxed it. I kept it in tip top running condition hoping that someday I would love riding it. But that never happened. The cafe racer dream had become a painful nightmare.

I still have a cafe racer dream, but it doesn’t involve Dick Mann or clip-ons. I want to build a bike that has the cafe racer look but keeps the standard riding position. Paul Dunstall built Sprint versions of his Norton Atlases and Commandos. These were bikes with performance upgrades and the cafe tank and seat but with regular bars and pegs. A bright red Dunstall Domiracer Sprint sounds about perfect for me. I guess I have a new cafe racer dream. Stay tuned.